1. Introduction

On the fourth day of the annual Hindu festival Divali, women of the land- and cattle owning castes in the rural villages near Udaipur city in southern Rajasthan knead two-dimensional sacred sculptures out of large quantities of fresh cow dung (

gobar) (

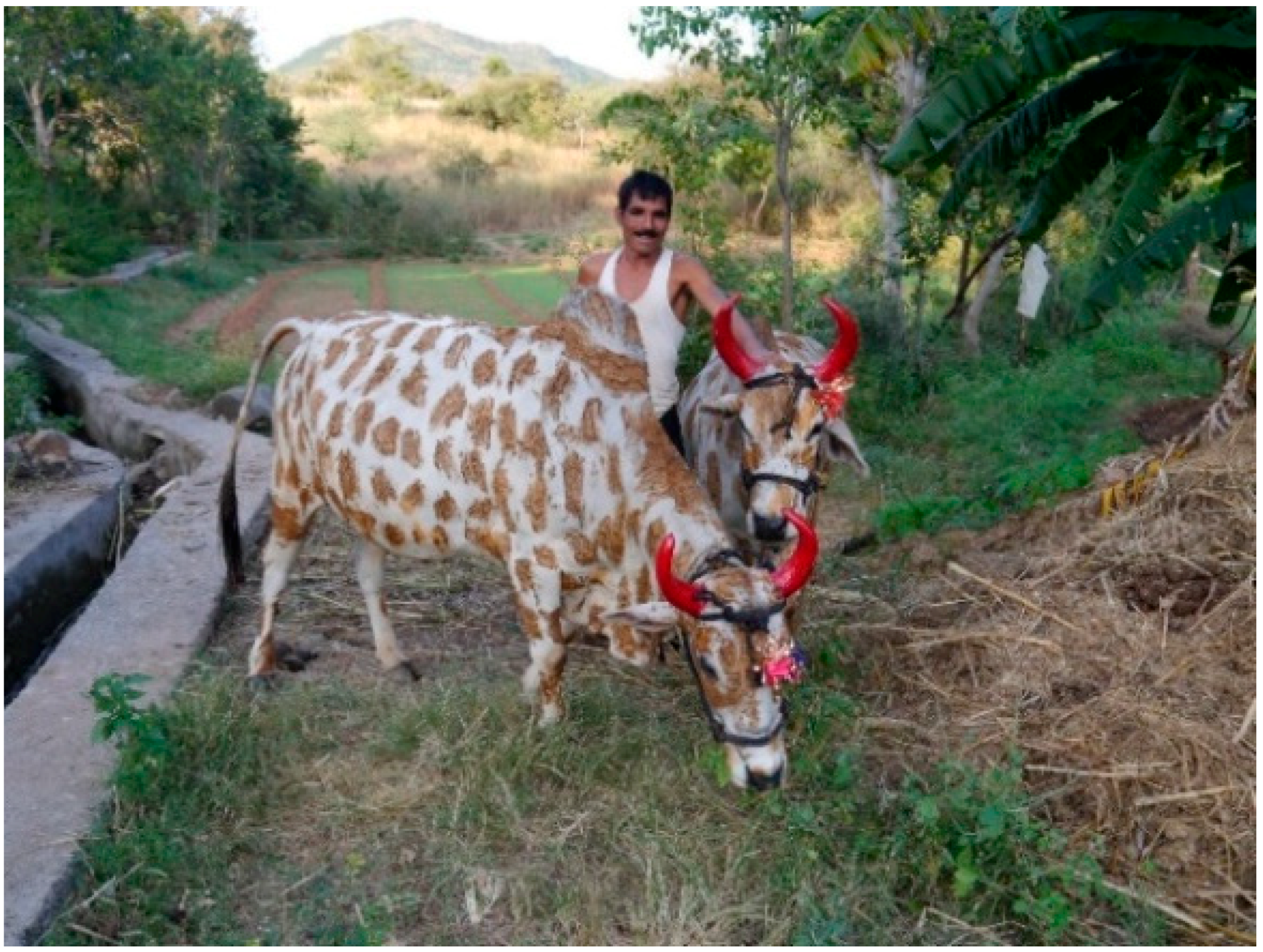

Figure 1). The women’s ritual of making and blessing the sculptures starts in the morning after sunrise and finishes about three hours later. The sculptures, which the women call Govardhan, only exist in the creative and ritual process of making them. Immediately after completion, women pray over the sculptures, take their cows from the cow shed to crush and bless them, and then abandon the material to give it time to perish. Two weeks later, they scatter it at their fields as manure and bringer of good luck. The crafting of the cow dung is a joyful event in the villages. The women occupy the village streets and do the ritual without help from temple priests. Male relatives also respect the women as ritual experts and wait for the evening when it is their turn to honour their bulls and beautify them with red paint and henna decorations (

Figure 2).

This yearly ritual of kneading and praying with cow dung is known as the

Govardhan puja (worship of Mount Govardhan).

1 It is generally said to be the worship of the popular cowherd god Krishna and the natural environment he inhabits (

Entwistle 1987;

Lodrick 1987;

Toomey 1990;

Vaudeville 1980;

Wadley 2000b, pp. 12–13). Mount Govardhan is a sacred hill in Braj, a region in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Braj, and particularly, Mount Govardhan, are the setting for many legends relating to Krishna’s life: it is where he was born and raised, grazed his cattle, and played with his girlfriends. The stony and oval shaped flat mountain is perceived as the natural form of Krishna himself and thus as a living being (

Haberman 1994, p. 126).

2 Even beyond this sacred landscape, Hindus recognize in every oval-shaped stone the aniconic form of Krishna’s body (

Haberman 2017, p. 487). Krishna

is Govardhan and in this manifestation the protector of cattle and cowherd populations. The oval and convex appearance of Krishna Govardhan is also the basic shape of the cow dung sculptures made by the women in rural Udaipur, at 650 km from Braj.

When doing ethnographic fieldwork during the Divali festival in 2017, I observed women creating the sculptures at the doorstep of their residences in two different villages. These women share with Krishna a deep love for cows. They raise an average of two cows and two buffalos and spend most of their (leisure and working) time in close proximity with them by sheltering them in or nearby the house and taking them back and forth to the fields for grazing. The cattle are part of the family and receive women’s unremitting care and attention. When observing the Govardhan worship, I noticed that the women intensely enjoyed the kneading of cow dung. When questioning them about the form and content of the sculptures afterwards, I realised even more the ritual was not restricted to the worship of Krishna. Although it is generally said that the cow dung figure represents the Govardhan hill and thus Krishna’s body (e.g.,

Vaudeville 1980), women’s own iconography revealed many more figurative layers. The sculptures also reflect the local environment women share with families, animals and (other) gods.

In line with the special issue’s focus on material religion and ritualistic objects, this article seeks to answer the questions: how are women’s cow dung sculptures built up as ritual objects, what different images are expressed in them, and what do these images reveal about women’s intimate connections with their human and non-human environment? Concentrating on the iconography of women’s sculptures I aim to understand how the ritual—with its mythical origin in the sacred landscape of Braj—finds its local expression in rural Udaipur that is meaningful to women’s daily religious and economic lives.

Women’s sensory engagement with cow dung took me right into the core business of the women in the villages. Working with cow dung turned out to be daily routine rather than exceptional religious practice. What in a series of Divali rituals is festively set apart from everyday life in fact reflects women’s daily operations with this material: they collect it in the cow shed, carry it on their heads to the fields to be used as manure, and process it into various products vital to their daily lives. The cow dung is not ‘dirty shit’ nor animal ‘waste’ but the most precious gift women receive from their cows. For me as a researcher it was core material too because it offered me an entrance into the realm of human–nature relationships which appeared to be crucial to women’s daily lives. The focus on cow dung made me realise that women, cows and cow dung are intimately connected and constitute the vital link in the ecological equilibrium of land, humans, animals, plants and water; a link that guarantees the villager’s well-being.

The cosmology women express in their cow dung sculptures challenges any nature–culture and nature–supernature divide that is recently discussed in anthropology (e.g.,

Descola 2014;

Hastrup 2014;

Ingold 2000,

2011); as well as the stereotypical domestic-public, female-male divide that is often said to characterize people’s segregated social lives in North India.

Wadley (

1989, p. 73) for example, stated in her work on women’s ritual in a North Indian rural community:

Whereas men’s rituals are aimed primarily at general prosperity or good crops and at the world outside the house itself, women’s rituals focus more specifically on family welfare and prosperity within the walls of their homes. (…) Essentially, men and women in Karimpur occupy separate worlds. For the most part, women live and work in their homes and have little mobility outside of them. (…) The courtyard and the rooms around it form the women’s world. (…) In many aspects of life, even in the content of songs and the way they are sung, men and women express their separate worlds. It is not surprising, then, that women’s desires, as expressed in their rituals, are those of their world—the household—while men’s concerns are focused primarily on the outer world.

Such a gender divide resonates in the literature on Govardhan puja in Braj. Although this may be the outcome of local research on gendered divisions of tasks and responsibilities in private and public spaces in the 1980s and 1990s, it also may reflect dominant (traditional) western and (priestly) male assumptions about Hindu women’s confinement to the home. To this perspective I would like to add a gender perspective that connects with (feminist) anthropologists’ scholarship challenging the stereotype image of the subordinated and secluded North Indian woman (e.g.,

Gold 1988;

Harlan 1991;

Jeffery 1979;

Jeffery and Jeffery [1996] 2018;

Pintchman 2005,

2007;

Raheja and Gold 1994) and is based on my research in Rajasthan (e.g.,

Notermans and Pfister 2016). In my opinion, women’s Govardhan puja in rural Udaipur today, in both its public location and its outward orientation towards the natural environment, allows a gender perspective that goes beyond women’s domestic domain and values the vital contributions women make to the rural economy and the sustenance of the environment that humans and non-humans share. It also reveals a gendered view of the human–nature relationships that is part of women’s cosmology.

I will first describe the fieldwork location and the research methodology employed. Then I will explain how the research connects to the existing literature on the Govardhan puja in particular, to the women–cows–cow dung connection in North India, and to women’s ritual art more generally. Then I turn to the context of the Divali festival before focusing on the material form and ritual sequence of women’s Govardhan worship in rural Udaipur. The description of Govardhan as a ritualistic object will follow the analytical distinction between the various meaningful layers I found to be present in women’s cow dung sculptures. In addition to the iconographic layers and before turning to the conclusion I will add to the analysis two more dimensions by describing the performance and the ritual space.

2. Fieldwork in Rural Udaipur

My qualitative study of Govardhan puja took place against the background of 10 years of recurrent research in the same region. My long-term involvement in women’s religious lives in Udaipur and nearby villages started in 2008 and continued with yearly revisits ever since. Studying the meaning of women’s rituals and symbolic activities requires longitudinal commitment because women express their religious knowledge in a year-round cycle of festivals. During a total of 17 months of fieldwork, I studied a variety of these calendrical festivals (like Holi, Sheetala Mata, Dasha Mata, Gangaur, Raksha Bandhan, Navratri, Karva Chauth, and Divali) and often seized an additional meaning of a recurring symbol in another ritual than that under study at an earlier moment. Moreover, religion in everyday practice is often about

doing not

saying and, therefore, difficult to access through interviews alone, especially when the ritual (or festival) is still taking place (

Pink 2009). Revisits make it possible to look back, get detailed explanations, and take multiple perspectives into account.

As the Govardhan puja occurs in a short time on one particular festival day, I focused my attention on women’s ritual activity in two neighbouring Hindu villages, Havala and Badi.

3 In both villages, a vast majority of the population belongs to the land- and cattle owning castes: the Brahmin (priestly) and Sutar (carpenter) castes in Badi, and the Rajput (warrior) and Teli (oil presser) castes in Havala. In Badi, the dominant caste is Sutar (40 percent of the population). Together with the Brahmin who are almost equal in size they make up 75 percent of the village population; leaving 20 percent for scheduled tribes and 5 percent scheduled castes.

4 In Havala, the dominant caste is Rajput (75 percent of the population). Together with the Teli caste they make up 85 percent of the village population; leaving 15 percent scheduled castes. Nearly all houses in Havala have a cowshed inside their compound, right opposite or next to it. With an average of 5 people and 4 cattle per household Havala village is populated by almost an equal number of human and animal inhabitants.

5Cows occupy a vital position in women’s daily lives: they are simultaneously perceived as children of the family, demanding constant care, and as mothers because they give milk and nourish the human family. In this position they are venerated as

Gaumata (Mother Goddess Cow). The cow helps the human mother to sustain the family: by providing milk (which women process in various nutritious products like curd, butter, cheese, buttermilk, and sweets), urine (used as medicine and insecticide, and as a purifier in rituals because it is considered as pure as sacred water from the Ganges), and cow dung. Cow dung has several uses: as an organic and ecologically sound manure for the fields, or processed into cow dung cakes as fuel (for cooking or heating when temperatures get cold, and because of its pureness for sacred sacrificial fire ceremonies (

havan)), as a disinfectant in homes, and for coating walls and floors because of its capacity to absorb malignant energies, to purify the space, and to cool the house in summer times.

6 The intimacy and good feeling people have with cow dung is also experienced when eating the most favourite local bread which is baked directly in cow dung cakes and consumed with lentils (a dish called

dahl bati). Because of all these nourishing and life-giving capacities the cow is a symbol of prosperity and fertility, which applies,

par excellence, to the cow dung as well.

The traditional caste occupations in the villages are largely replaced by agriculture and animal husbandry; by work in dairies oriented at the urban market, and by wage labour in Udaipur (government or tourism-related jobs). When asked about the gendered division of labour, people say both men and women engage in agriculture and cattle breeding. In practice, however, the women do most of the work: they feed, milk and care for the animals, decide about crossing their female cattle and care for the baby animals; clean the stable and collect the dung; carry water; cultivate the fields (for subsistence and marketing); and collect fodder and firewood. Men assist in the fields when necessary, help with transportation and marketing in town, and take over women’s animal care mainly when running a commercial dairy (with 4–8 buffalos). Men doing wage labour commute between the village and the city, leaving the bulk of agriculture to their wives but boosting the household economy with cash money, often used for house construction and luxury goods. The women studied state that they love their work and appreciate the husband’s financial contribution. Only a few women received no support from their husband; some were widowed, others complained about their husband’s drinking habits. These women helped themselves out with sharecropping.

7Altogether, the village women appear to live a prosperous and independent life, enjoying the daily freedom to move around in the village and between their house and their field, often in cheerful company of neighbouring female friends and relatives. The villagers in general seem to be well off. They have land and cattle that secure their lives; their land is fertile and extremely valuable; there is sufficient groundwater for irrigation; and at a stone’s throw from Udaipur (with half a million inhabitants and a flourishing tourist industry), a surplus of milk and vegetables is easily sold at the urban market, enhancing the household income as well.

To study Govardhan puja, I initially stayed for one month during festival time in 2017. I focused on the women of the land- and cattle-owning population (Brahmin, Sutar, Bhil in Badi; Rajput and Teli in Havala) as they have cows and fields to honour and ample cow dung for doing the puja. I made observation tours through the villages at the specific festival day of Govardhan puja. I had small talks with the women doing the ritual and recorded their activity on photos and videos. When I returned to the field in 2018 (two visits of one month each) I used this visual material for small talks about the event and during in-depth photo-elicitation interviews with 15 women I observed doing the ritual before. Walking through the rural environment as ‘participant sensing’ (

Pink 2009) allowed me to observe people’s engagement with nature from a different perspective. From the height of the mountains I saw how the connections between the different landscape elements (mountains, fields, and lakes) reflected the composition of women’s cow dung sculptures. I also made grand tour observations in the villages to observe women during daily activities and to learn about the gendered division of tasks as this could deviate from the spoken information in interviews. Two male and two female local residents helped me translating between English, Hindi and the local language Mewari. As the Census of India from 2011 lacks quantitative information on land- and cattle ownership and caste composition, I conducted a survey with a sample of 10 percent of the households in Havala and interviewed the block development officer at the Panchayat in Badi. I also asked men about the meaning and stories behind women’s cow dung figure but they said they could not help me because ‘it was a ladies’ concern’. While cattle raising and agriculture was said to be (in principle) gender neutral, praying with cow dung was unanimously defined as women’s work.

3. Govardhan Puja in the Literature

Considering the fact that the Govardhan puja is said to be an ‘all-Indian (although predominantly northern Indian) cult’ (

Vaudeville 1980, p. 1), recurring every year, and involving large numbers of female cattle farmers in North India, remarkably little scholarly attention has been paid to it. Braj scholars clearly dominate the literature on Govardhan puja (e.g.,

Entwistle 1987;

Vaudeville 1980). They explain the ritual from the Govardhan myth, known as “govardhana-dharana” (the lifting of the Govardhan hill) (

Vaudeville 1980, p. 1). This story goes that Krishna saved the cowherd people in Braj from heavy rains by lifting the Govardhan mountain with his left hand and sheltering the people together with their cows under the mountain. Putting much emphasis on the mythical and scriptural context, little attention is paid to the women doing the ritual and the social-economic context in which the ritual takes place. Braj scholars also tend to equate the Govardhan puja with the ritual of

Annakut (mountain of food), happening at the same day of the Divali festival. During this temple ritual people offer huge amounts of cooked food to Krishna, usually under priestly supervision (

Entwistle 1987, p. 283;

Toomey 1990, p. 165;

Vaudeville 1980, p. 1). Emphasising temple religion rather than women’s lived religion, women’s sacred sculptures produced in or nearby the home remain neglected. Moreover, Braj scholars found the Govardhan puja to be a private and domestic ritual, done by the women of the household in the inner courtyard of their residence (

Vaudeville 1980;

Toomey 1990). In rural Udaipur, however, I found today’s ritual taking place in the public domain of the village streets. This made me wonder whether the Braj literature pictured a regional rather than a general North-Indian image and how a contemporary and deviant local expression in rural Udaipur relates to the classical North Indian myth.

In the Rajasthani villages, I found the ritual to be different in many aspects. Besides the Govardhan myth local stories about Krishna appeared to be meaningful. The women neither spoke about Annakut nor cooked huge amounts of food. Although Vaudeville’s article ‘The Govardhan myth in Northern India’ (

Vaudeville 1980) offers detailed information on both legend and ritual, only one of the three essential features of the ritual she raises corresponds to my observations, namely that it entails ‘a cow dung anthropomorphic representation of the Govardhan hill’ (1980, pp. 3–4). Although

Vaudeville (

1980) mentions the ritual to be an exclusively women’s activity, I believe the gender perspective would deserve more attention in the literature on the Govardhan puja. In this study, I would like to focus on such a gender perspective by offering a study of lived religion. In my approach gender matters because women are the sole practitioners, the cow dung figure itself is gendered, and also the cattle and the natural environment are locally perceived in gendered terms.

I intend to show that Govardhan worship in rural Udaipur responds to the age-old myth and simultaneously integrates local realities and women’s present-day matters. It is likely that the Govardhan puja varies across North India and takes its peculiar form in each specific context of oral and ritual traditions, gender relations and human–nature relationships.

Lodrick (

1987, pp. 109–11) confirms the variation across the country and states that the Govardhan puja varies from being strongly related to Krishna in Braj to being less associated with Krishna elsewhere, or lacking such a link altogether. According to Lodrick, when the connection with Krishna is weak and the focus more on the dung, “an alternative etymology of Govardhan sees the word being derived from

gobar and

dhan, meaning “dung-made,” which in village usage becomes “cow-dung wealth”” (1987, p. 109). This interpretation comes close to the popular etymologies I found in rural Udaipur: “go-vur-dhan” is “cow-increase-wealth”—thus remaining true to the Sanskrit noun vardhana (increasing; bringing prosperity)—but also: “gobar-dhan” is “cow dung-wealth”—a delightful spin in which the vernacular pronunciation of v as b produces a direct association with gobar, cow dung. The local ritual involves the worship of cow dung

and Krishna, and simultaneously honours women and cows who increase wealth in mutual cooperation.

4. The Women–Cows–Cow Dung Connection in the Literature

In contrast to the Braj literature paying explicit and extensive attention to the Govardhan puja, the (feminist) ethnographic literature on women and religion in rural North India hardly mentions women’s ritual handling of cow dung.

Wadley (

1989, p. 75) briefly r efers to the Govardhan ritual in her study of a calendrical cycle of 20 rituals practiced by high-caste Hindu women in a rural village in Uttar Pradesh. For detailed description, however, she selects five rituals in which, she states, women’s male kin (brothers, husbands and sons) are the focus of worship. In her contribution to the longitudinal study of

Wiser and Wiser (

2000);

Wadley (

2000a, p. 319) briefly mentions the Govardhan puja as one of the rituals occurring during the fall festival season but again does not pay analytical attention to it. Notable is the picture at the first page of this book’s appendix showing two women kneading a cow dung sculpture for Govardhan puja (which appears to be a variation to the ones in Braj and Udaipur). Its caption provides the sole information on Govardhan puja in this extensive ethnography on the lives of rural women in North India.

In her work on women’s religious rituals in Benares (Uttar Pradesh),

Pintchman (

2005, pp. 63–66) instead dedicates a complete section on Govardhan worship and Annakut, complemented with a picture showing two women worshipping a cow dung figure (ibid., p. 65). Although her description largely follows the Braj literature by emphasizing the importance of the Govardhan myth and Krishna, she also found that “celebrants place the image at their front gate so that Govardhannath will safeguard the home for the upcoming year” (ibid.). This is confirmed in the picture showing two women sitting on the sidewalk in front of their residence. Pintchman, however, does not analyse the positioning and iconographic content of women’s cow dung figures, but focuses on the textual interpretation of women’s songs and narratives accompanying the ritual.

8I found the most detailed elaboration of women’s cow dung sculpturing in

Raheja’s (

1988) work on rituals of gift-giving and intercaste relationships in a rural village in north-western Uttar Pradesh. She describes a ritual called

godhan takkarpurat (ibid., pp. 166–68, picture on p. 190) which she analyses in the context of Divali, the sugar cane harvest, and people’s crucial relationship with cattle. She notes a link with the Govardhan myth and observes women doing the ritual in the cattle pen and placing small figurines of cow dung into the

takkarpurat (a square frame made of cow dung) (ibid., p. 167). Both aspects of the

takkarpurat come close to women’s practice in rural Rajasthan. Even more interesting is that the

takkarpurat would absorb the inauspiciousness of the cattle, the family and the harvest and bring auspiciousness and wealth for the upcoming year. This corresponds with the meaning of women’s doorstep designs in rural Udaipur that are also meant to attract fortune and protect the home against misfortune. In line with Raheja’s emphasis on the functioning of the ritual, I will focus on cow dung as the central material that makes women’s sculptures work as purifiers and bringers of good luck.

The aforementioned studies which (more or less) refer to women’s cow dung ritual pay little or no attention to the cow dung material as well as its unique properties. Some descriptions of women’s rituals indirectly (mainly through the pictures included; e.g., (

Pintchman 2005, p. 105)) reveal that sculpturing with cow dung, and also with (river) clay, regularly occurs in women’s worship (

Pintchman 2005, pp. 103–4;

Wadley 1989, p. 76). Pintchman says about clay that women declared the Ganges mud to be “not only readily available, but also pure, and hence an appropriate substance to use to make divine images. The Ganges is a goddess, and the mud along the river’s bottom is continuously cleansed by her sanctifying presence” (2005, pp. 103–4). This aspect of being plentiful, pure and sacred applies to cow dung as well, which makes it a proper substance for ritual sculpturing. Because of its cleaning property of absorbing evil and inauspiciousness, women also use cow dung for plastering houses, floors and doorsteps (e.g.,

Elgood 2000, p. 223).

Taking into account the capacity of cow dung to make things clean and auspicious, I follow Ingold’s plea “to take materials seriously” (

Ingold 2007, p. 14). I will explore the cow dung and study its properties, “not as fixed, essential attributes of things (…) but as processual and relational” (ibid.) and study how women, in processing the material, shape and establish their relationships with their human and non-human environment. I will show that via the processual and relational properties of cow dung, women play a vital role in village economics and environmental care.

In addition to the scarce descriptions of women’s Govardhan puja in the ethnographic literature on women’s rituals in North India, I found relevant comparative information in the ethnography of women’s ritual art in India. This art includes terracotta figurines, wall and floor paintings which are, like the cow dung figures, “largely ephemeral, made to endure the time of the ceremony and only efficacious if combined with ritual performance” (

Elgood 2000, p. 188) and closely linked to people’s residences. In women’s artistic activities, ethics and aesthetics are closely related (ibid.;

Nagarajan 2019). What looks good and is beautified (places, humans, animals, gods) entices good luck and abundant life. During Divali in particular, women purify and beautify places to attract divine attention and to invite Lakshmi and her auspicious energies into their house.

Nagarajan’s (

2019) recently published ethnography on women’s art in

kolam rituals in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu comes closest to my observations of Govardhan rituals in rural Rajasthan. In Tamil Nadu, women paint a kolam (ritual design made with ground white rice flour) on the front threshold of the house: the place where the private domestic world encounters the outside world. Women make this sacred drawing “to do something beautiful, to banish misery and bad luck, and to encourage the auspicious entry of Lakshmi who brings wealth and good luck” (2019, p. 4). The design also acts, Nagarajan states, “as a bridge between inner and outer world, between what can be controlled and what cannot be controlled, and between domestic and public space” (2019, p. 10). Women’s doorstep rituals during Divali in rural Udaipur resemble women’s daily kolam rituals in Tamil Nadu. The Govardhan, like the kolam, serves as a bridge and ‘as a marker of gender’ (2019, p. 33). By making the doorstep pure and beautiful with Govardhan, women celebrate their identity as auspicious wives and mark it as a crossing—not a divide—between domestic and public space; a crossing where women together with their cows play an important role as protectors of the house and providers of wealth and prosperity.

By saying that women’s socio-religious and economic participation goes beyond domesticity and stretches out into the wider environment, I do not deny that the domestic domain highly matters for the women studied. Their daily orientation and activities certainly

contain the domestic but are not

confined to it.

9 5. Divali, a Celebration of Wealth

The Govardhan puja is one in a sequence of various rituals, each connected to a specific day of India’s nationwide and biggest religious event Divali (see

Burkhalter Flueckiger 2015, pp. 127–29). At new moon, on the third and main festival day, Hindus celebrate the material world, with Lakshmi, the goddess of abundance, money, and material wealth, at the centre of their devotion. Popular images of Lakshmi depict her as the provider of money and gold and as such people want her to cross their threshold on Divali evening. In the build-up to the festival, people thoroughly clean their residences (to brush away old and negative energies), renew the paintwork (and other decorations), and then shop for gold and silver coins and all kinds of consumer goods (devices, vehicles, home appliances) to beautify the house and home shrine. Women in particular shop for new furniture, kitchen utensils, clothes and golden jewellery. They also clean and paint the doorstep of their residences before decorating it with colourful geometrical designs (

alpana or

rangoli) to attract Lakshmi’s attention (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

10 On the main festival day they dress up nicely to welcome Lakshmi into their purified houses with

Lakshmi puja and numerous small candle lights (

diya).

In Udaipur and surroundings, the clay lamps lit for Lakshmi contain a grain of corn, a wild red stone fruit called

bor, and cotton for fuse.

11 Together with the red earth colour of the lamps, they refer to the fact that Divali is originally a rural harvest festival, honouring the land and the wealth of food that people gain from it. The festival still demarcates the transition from harvest to sowing season. It combines people’s monetary wealth—the ‘harvest’ of consumer goods in shops—and people’s natural wealth –the harvest of crops in the fields. While Lakshmi reigns over the third day, Krishna reigns over the fourth day, the day of Govardhan puja. Together they cover people’s economic life that stretches between rural and urban activities. The two festival days also publicly celebrate women’s vital contributions to society: they are honoured as married women and providers of domestic happiness in their identification with Lakshmi, and as farmers and cattle raisers in their identification with Krishna.

12Lakshmi and Krishna are closely related to each other in their symbolic relationship with cows and cow dung, the earth and fertility.

13 While in the popular urban image, Lakshmi’s gold is depicted as money, in the rural areas, the precious cow dung and sugar cane are considered to be her ‘gold’ (which will be explained later on). Lakshmi’s reference to riches, abundance, fertility and the potency of the earth finds expression in women worshipping her in the form of cow dung (

Elgood 2000, p. 76). The Divali festival thus provides, next to the age-old Govardhan myth, an important symbolic context for understanding women’s cow dung rituals in their lived religious lives.

6. The Govardhan Puja

On an early morning in 2017, I observed the women of the land- and cattle owning castes doing Govardhan puja in the streets of the two selected villages. The women’s main activity is kneading the sculpture. Govardhan is jointly made by the married women of a patrilineal family who together enjoy the artistic process of beautifying the cow dung. When asking both women and men why only women make Govardhan, everyone answered it was because of the beautification work: “Only ladies know how to make Govardhan beautiful. Gents don’t know, they don’t have the techniques to make things beautiful.” Only the married women do the kneading because they enjoy the auspicious position to bring fertility and prosperity to the family.

14 The women make the Govardhan at the entrance of the house or the cattle yard, depending on whether there is only one entrance for people and animals or two separate ones. This entrance demarcates for both humans and animals the transition between inner and outer space; a transition that needs to be protected against bad energies and to be beautified to let positive energies enter.

It is the same transit space that was beautified to welcome Lakshmi in the house the day before. The beautification of Govardhan is in fact the third layer of auspiciousness that women apply to the doorstep. After cleaning the doorstep on the third festival day, women paint the floor with a mixture of cow dung, red earth and water. Cow dung thus is “the primary ritual ingredient in the creation of an auspicious and unpolluted basis, a sacred space that acts as a ‘canvas’ for the ritual designs that follow” (

Nagarajan 2019, pp. 44–45). The second layer is the alpana or rangoli design made on the purified and sacred canvas to attract Lakshmi’s attention in the evening. The next morning, the Govardhan is added as a third layer on top of the cow dung-painted and colourfully decorated doorstep (

Figure 5).

When modelling the sculpture, women sit on the doorstep of the houses in the village streets. Tens of kilos of freshly collected cow dung are processed in the Govardhan that vary in size between a 0.5 and 2 square metres. The more cows and cow dung women have, the bigger the size of their sculpture. I often heard the expression that ‘cow dung is like pure gold’ which explains women’s pleasure of working with big amounts of this material. The gift of ‘gold’ women get from their cows, is subsequently offered to the gods to beautify and please them and pray for prosperity and good luck. “Cow dung is so pure, it doesn’t smell,” a 35-year-old Teli woman in Havala explained to me, “that’s because our cows get good and organic food, no chemicals or artificially processed food. We collect the fodder in the mountains and in our fields.” When beautifying and protecting the doorstep as a transition place with Govardhan, the pureness and cleanliness of the cow dung matters because it absorbs inauspiciousness and appeals good luck.

The figure women carve in the precious and fertile cow dung material roughly shows two oval human bodies with head, nose, arms and legs. A proportionally big hole in the belly demarcates the navel and two smaller holes the eyes. On top of the body parts, there are flat round balls. The two human bodies are joint with a half circular strip of cow dung. The figures may vary in size, details, decorations, and finishing, but the two connected human figures recur in all village streets observed (

Figure 6).

15 After finishing this basic figure, different natural materials, like the freshly harvested cotton, corn, sugar cane, wheat, hay, and flowers, are added to beautify the figure (

Figure 7). Corn and wheat seeds are used to mark off the mouth, fingers, toes and the midriff. Tufts of raw white cotton do for dress-up, and fresh flowers and red coloured strings of spun cotton serve as jewellery. To make the design complete, two other major attributes are added to the figure: a freshly harvested sugar cane stick and an old door string made of hay. The sugar cane symbolises wealth and money. It is the main attribute of Lakshmi during Divali and refers to the natural ‘gold’ recently harvested in the field. An 80-year-old woman told me that in former times, before money entered the village economy, women used the sugar cane as a currency. The door string is part of the doorstep as a crossing place. Placed above the doorway, it saves the inner space from destructive forces coming from outside. The old door string is replaced by a fresh one at Divali. When throughout the year a member of the household dies, the string is taken off and burnt with the corps on the stake. Offering the old string as an ornament to the cow dung figure, is a gesture of thanksgiving and a sign of prosperity as it shows that no one died in the household that year.

The kneading and the decorating work take most of the time of the ritual. In a calm and joyful atmosphere, women work quietly though with a non-stop energy towards the end result. Only in Badi did I observe the women of the Brahmin caste singing songs while kneading (I will return to this later on). When satisfied with the result, the women worship the figure with puja. This only takes a few minutes. Some of the women then want to have their picture taken together with the beautified and blessed sculpture. The result of several hours of meticulous work is not meant to stay for exhibition. Immediately after the finishing, a cow is taken from the shed to cross the doorstep and bless the Govardhan by trampling it. This brings the event to an hilarious end as the cow often refuses to step through her own shit. She prefers to jump over it but the women insist till she crushes the figure with her hoofs, even if it is just a little part. The women then leave the sculptures behind and go inside their houses to resume their daily activities. Eleven days later, on the auspicious lunar day of

ekadeshi, women sweep the dried cow dung aside and decorate the spot with a

swastika (

Figure 8) or rangoli.

16 Herewith, they renew the doorstep as a symbolic place where good luck enters the home. Two days later, at full moon, women bring the dried-up cow dung to the fields to scatter it as blessed manure.

Although the ritual sequence and the visual form of women’s Govardhan puja is very similar across the villages, I noticed differences in performance and narrative as well. While the women in Havala brought up a shared local story behind their Govardhan, there was not such a strong narrative consensus among the women in Badi. The women in Badi, however, had a repertoire of songs for Govardhan which I did not find in Havala. While the women in Badi wore red wedding saris and excessive jewellery, and did not always involve the cows in their ritual; the women in Havala were less exuberantly dressed, did not observe a common dress code, and took their cows from the shed without exception. Even within the villages variation seemed to occur when newly married-in women from other locations brought their own habits and interpretations along.

7. Reading the Cow Dung

Women’s sculptures represent many things at the same time: various images conflate to capture a complex reality. In order ‘to read the cow dung’ and to understand women’s prayer, I will look at it from different perspectives. I disentangle five symbolic layers, each offering a different image. In explaining the five images moulded together in each sculpture, the emphasis will not be on the differences between or within the two villages nor on women’s multiple voices and diverse interpretations.

17 My aim is to represent the story that these farmer women

share about their intimate relationship with cows and land, their crucial role in the rural economy, and their cosmology. In the following description, I will mainly rely on the narrative information of the women in Havala. Women’s songs from Badi will be used to interpret women’s narrative performance in the next section.

7.1. Father and Son

With loving devotion and meticulous care the women knead two connected human figures. When asking them who these figures are and what they represent, the women in Havala unanimously answered: a father and his son. The story behind this is a story related to the cowherd-god Krishna and located in Braj. A 65-year-old woman told me that the story goes as follows:

One day [about 5000 years ago], a married woman of the Gujjar caste [cattle breeders] left the house to sell curd. She was very good-looking: pretty and strong. Krishna bhagwan (god) noticed her, he immediately felt attracted by her and tried to snatch her. When he seized her sari, she responded: “Leave me”, but he didn’t let her go because he wanted to marry her. She then told him to come on Divali night. Then he could take her and marry her. This beautiful woman was married and had a little son.

On Divali night, Krishna bhagwan came with his crown, to take her. The woman was sleeping in the cow shed while her husband and son were resting under a tree at the foot of the mountain. When Krishna bhagwan appeared at the top of the [Govardhan] mountain to go down and take the woman in the village, his cows were frightened that someone came out so abundantly dressed in the night. He’d put on many decorations and a huge headdress, because he wanted to enchant the beautiful woman who was waiting for him. The cows didn’t expect to see him like that and, scared by his outfit, they ran down the hill in panic and trampled the two men resting there and killed them.

The woman told to Krishna bhagwan: “You may take me but I want my husband’s and my son’s name to be honoured. You have to do something.” Then, in the morning after Divali, Krishna bhagwan came to the village and told the women in the village to make the father and son in cow-dung and to worship them and remember them with puja.

With only some minor variations, the same story was told by all women I spoke to in this village. They said that in remembrance of the two men killed by Krishna’s cows, and observing Krishna’s instructions, they repeat the kneading and trampling every year.

7.2. Krishna Govardhan

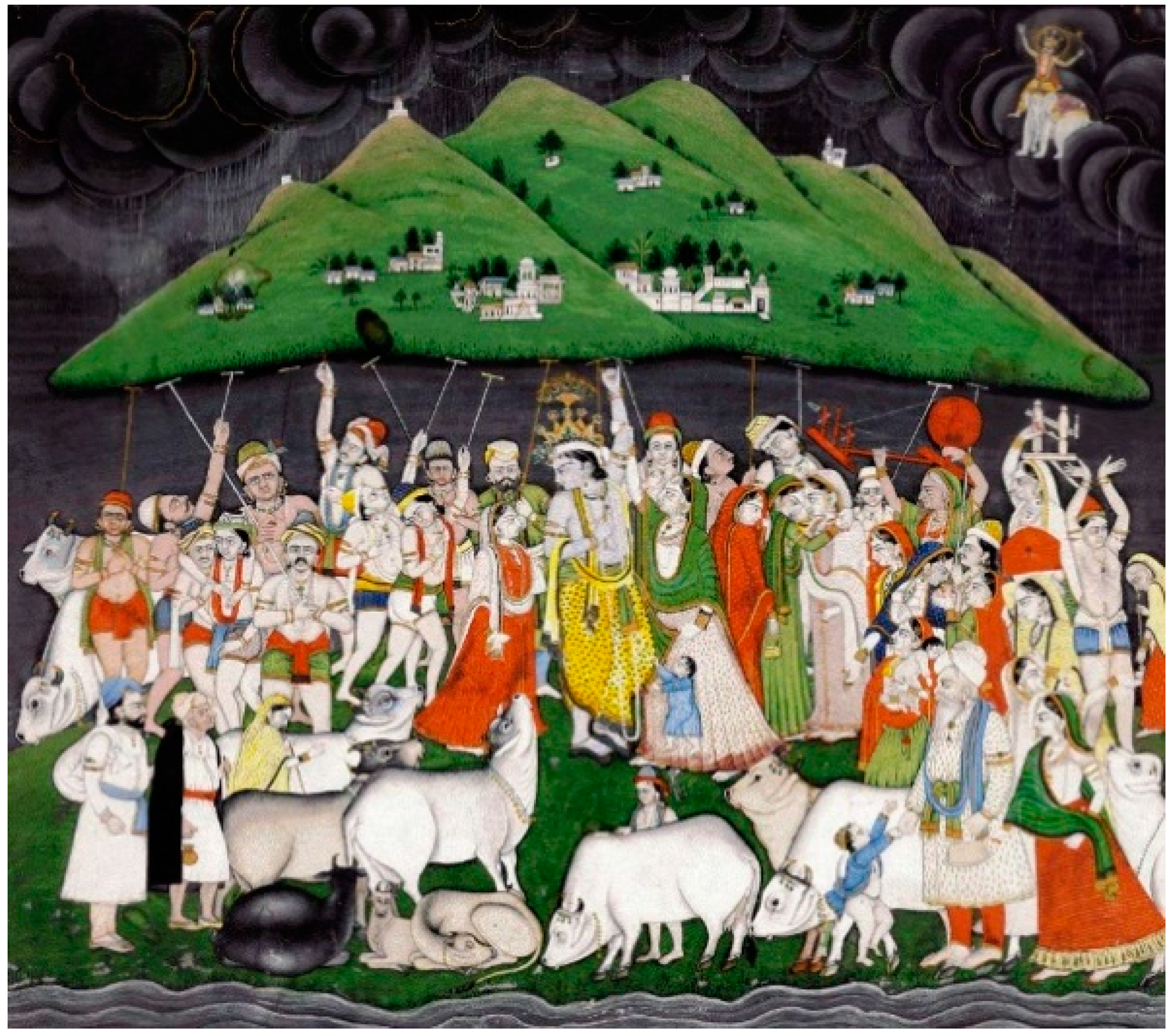

Besides local stories, the village women recall the “govardhana-dharana” (the lifting of the Govardhan hill) myth when explaining the figure. This myth remembers the day that Krishna defeated Indra, the god of thunder and rain. Still a child, Krishna protected the people in the Govardhan area from heavy rains and floods supposedly caused by god Indra who was angry with the people for not venerating him (see also

Haberman 1994, p. 111;

Eck 2012, p. 359). Krishna sheltered some in a cave inside the mountain and others by lifting the entire mountain with his left hand, and holding it up like an umbrella. All inhabitants, along with their cows, took refuge under the mountain. This image of child Krishna lifting the mountain with one finger and the people and cows hiding underneath, is very popular through North India (

Figure 9).

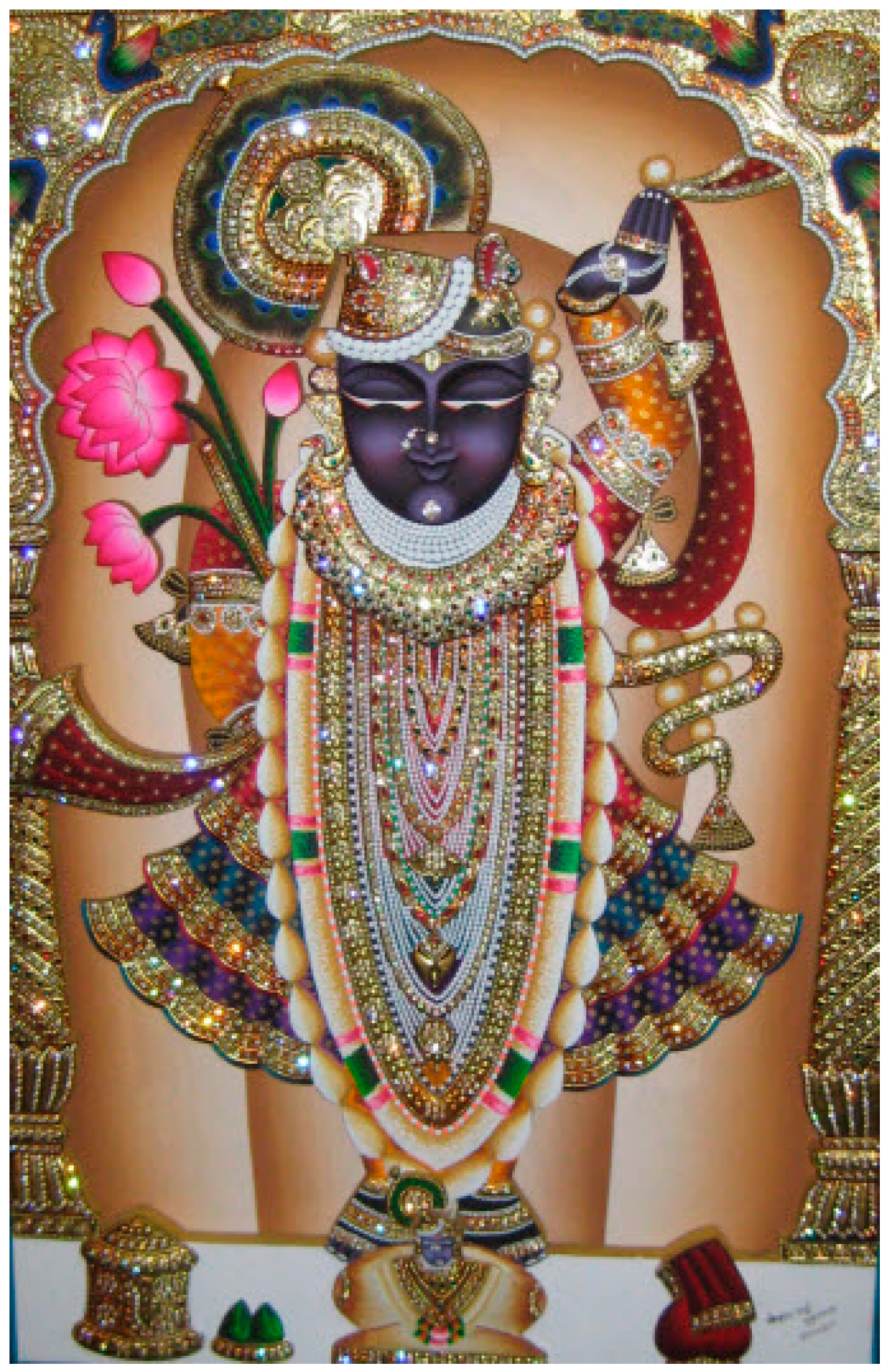

A particular manifestation of Krishna lifting the Govardhan mountain is Shri Nathji. He is very much loved and worshiped as the god of wealth in Rajasthan. According to the legend, Sri Nathji manifested himself in stone when he emerged from the Govardhan hill, first showing his arm and then his mouth (

Vaudeville 1980, p. 36). Thereupon, the local inhabitants started to worship Shri Nathji and placed the stone image in a temple on the hill in 1501 (ibid., p. 37). More than a century later, this image was brought to Rajasthan to protect it from the hands of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb who in 1665 was vandalizing Braj by destroying Hindu temples. Sri Nathji fled and went on a journey to Mewar which took several years before he reached Nathdwara near Udaipur. A temple was built in which the god took refuge in 1671 (

Vaudeville 1976;

Eck 2012, p. 377). When in the late 18th and early 19th century, the temple of Shrinathji was attacked, the stone image body was shifted again and protected at Udaipur. As Udaipur and its adjacent area was home to Sri Nathji for centuries, people’s devotion to this manifestation of Krishna is immense. Typical iconographic characteristics of Sri Nathji are his rich headdress, his exuberant jewellery, expensive clothes, and his raised left hand (

Figure 10).

Related to the Govardhan myth are thus two images of Krishna: Krishna as the convex and oval shaped natural form of Mount Govardhan and Krishna as the god child Shri Nathji lifting the mountain. Both images are visible in women’s cow dung sculptures. Each of the two male cow dung figures represents the rocky hill in Braj and the abundantly dressed and decorated Sri Nathji lifting that hill. Concerning the first image, the flat round balls of cow dung put on top of Krishna’s body are said to represent the stones located at the rocky hill (which again are natural forms of Krishna). The twigs of hay that women upwardly fix into the cow dung mountain give the mountain its trees and greenery. Concerning the second image, Shri Nathji emerges from the cow dung figure through its excessive jewellery (cotton strings and flower necklaces), his pronounced headdress, his raised finger, and the balls of cow dung now representing the hill he lifts up.

7.3. A Fertile Natural Environment

A striking and meaningful element of the cow dung figures is the semicircle connecting the two human/divine figures at the bottom (

Figure 6). The inner arms of the two figures also often touch, creating in this way a closed space which is said to be a water basin. Some women explain this part of the figure to be ‘a river’ (the sacred river Yamuna) others say it is ‘a lake’. Inside this river/lake basin women put small cow dung figures that represent the buffalos bathing in the water. When women, during the puja, pour water and other precious liquids like milk and curd in the basin, the image of cattle bathing in the river fully emerges.

From this perspective, the image changes from being a father and a son, and being Krishna Govardhan and Sri Nathji into the image of a fertile sacred environment: an environment of a sacred mountain and a sacred river, of earth and water. The image’s orientation also turns into another direction: Mount Govardhan is on top of the figure and the river Yamuna at the foot of it. The geographical connection between the hill and the river goes back to ancient times, when the sacred Yamuna used to flow nearby the Govardhan hill. Nowadays, the sacred river Yamuna still winds her way through Braj (

Entwistle 1987;

Haberman 2006). Also in the imagery of Sri Nathji the Yamuna often flows at the foot of the sacred hill (

Vaudeville 1980, pp. 9–10).

Besides the geo-physical connection between mountain and river, there is also an aesthetic and gender connection: mountain and river together form a good-looking, and well-balanced landscape (see

Eck 2012, pp. 125–26). In view of beauty, harmony, fertility and prosperity male and female natural elements need to be joined. In India, sacred rivers are generally considered female and sacred mountains male. In addition, the Yamuna river is said to be the natural female form of Krishna (

Haberman 1994, p. 14); but also Krishna’s lover or bride, particularly in his form as Sri Nathji (

Haberman 2006, p. 102). This means the river and the mountain are worshipped as a divine couple, with the female river being seen as a liquid form of love, and the male mountain as a condensed form of love (ibid.). The divine world includes male and female elements as fertility and prosperity are said to arise from the union of both genders. Rivers need mountains to flow and to reach the earth without damaging it; mountains need rivers to live and have green overgrowth. It is only in the complementary of male and female landscape elements that life exists.

Approaching the top of the Aravalli Hills during the observation tours, I recognized these two landscape elements carved in women’s cow dung sculptures: the lakes situated in between the mountains. It is not the mountain-river couple of Braj that counts here, but the pairing of mountain and lake. Lakes are the hallmark of Udaipur’s natural landscape and from the height of the mountains, I realised how vital the mountain–lake union is for the villagers. In this desert area people largely depend on ground- and rainwater for drinking, cooking and irrigating. Only once a year, during the monsoon season, the lakes are filled with rainwater. The precious water runs down the mountains by intervals, regulated by the government. Although bigger in size, the shape of the Aravalli Hills appeared to come close to the mythic form of Mount Govardhan. In fact, the sacred mountain in Braj and Aravalli mountains in rural Udaipur belong to the same mountain range (

Haberman 2017, p. 486). The sacred landscape of Braj thus resonates in the villagers’ natural environment: the mountain and the lake, and the cattle in the enclosure. Even the cow dung stones and the twigs of hay that women add to the cow dung mountain reflect their own environment of dry stony soils and rocky hills, covered with the hay that women collect as fodder ‘in the wild’ (in the mountains) right at the time of the Govardhan puja.

In the image of the sacred and fertile environment, the gender of the cow dung also matters. With the earth being female, the cow dung is said to be male; male, because of the two men and god Krishna emerging from the cow dung and because it is scattered as male seed at the female earth to make it productive (see for symbolism of seeds and earth also (

Dube 1986)). Fertility results from impregnating the fields with cow dung. Both genders again need each other to produce life and food.

7.4. The Fertile Family

Looking more closely at the cattle in the water basin and listening to what the women tell about this image, I learnt there was another meaningful layer in the Govardhan that concerned prosperity and fertility in the family. When pointing at the small cow dung figures in the river/lake, some women said these were the bathing buffalos, others said they were the children in a mother’s womb. When asked, they confirmed they could be both. Through this material visualisation of the family in the cow dung figure, we come to see different aspects that are vital to women’s lives: (1) women’s families include both humans and animals; (2) women consider their cows and buffalos to be their children, sharing with them the same intimate space and giving them the same amount of care; (3) women’s fertility and the family’s prosperity is expressed in having cattle in the yard and children in the womb; and (4) women not only work on the reproduction of the human family; as breeders of cattle, they also work on the reproduction of their livestock. Crossing cows and elevating calves are main occupations in women’s daily life.

At first sight, the figures of father and son represent patrilineality. Both men and women desire having sons because male offspring carries on the family line. Sons used to stay with their wives and children after marriage while daughters will move out to their in-laws’ place. The importance of male sexuality for family fertility is made visible through an often well-articulated penis (and testicles) of cow dung in between the legs of the male figures. Simultaneously, women’s sexuality and reproductive power are expressed in the water basin. The babies in the womb and the cattle in the water refer to women’s reproductive capacities as mothers and cattle breeders. The Govardhan, on second thoughts, thus shows that besides men’s sexual power in patrilineal descent, women actively contribute to the patrilineal family by bearing children and breeding cattle, and nurturing humans, animals and land.

20Similar to the image of Krishna being male and female, mountain and river, the Govardhan blends male

and female sexuality that together produce offspring. This mixing is also evident in women’s ritual action when they worship the completed Govardhan. By putting (or ‘sowing’) seeds of grain in the basin, pouring water, milk and curd into it, and adding red sindoor powder and fire—as a ritual way of feeding, washing, and blessing the figure—the warm reproductive womb manifests herself in the blood-red and sperm-white liquid that together with the seeds fill the round space of the water basin: an image of sexuality and family fecundity that goes without saying (

Figure 11).

7.5. Penis, Vagina and Navel

When elaborating on the visual image of fertility that women carve in the cow dung, we cannot ignore three Hindu key symbols present in the sculpture: the penis (

linga), the vagina (

yoni) and the navel (

nabhi). Unmistakably visible in the Govardhan is the stick. When all kneading and decoration work is done, the woman go inside their house to get a tall and solid sugar cane (Lakshmi’s main attribute that is offered to her at the home shrine the day before) and subsequently put it in the navel of one of the male figures (

Figure 12). From a aesthetic viewpoint, the cane is disproportionally big in relation to the flat and much smaller size of the body that holds it. It fits, however, from the perspective of fertility. The sugar cane shows himself as the phallus symbol linga. The interpretation of the cane as linga is confirmed in some of the sculptures in which smaller sugar canes are put right on top of the penises of the two male figures.

21 With Lakshmi being the earth herself, her main attribute is the male sugar cane which penetrates the cow dung sculptures during Govardhan puja (see also

Elgood 2000, p. 76). The red and white coloured water basin represents the vagina, yoni, another Hindu key symbol. Linga and yoni, stick and womb, associated with the colours white and red respectively, are inextricably linked to one another and together abundantly recur in the material culture of temples and home shrines, as well as in the design of allegedly profane constructions such as water pumps (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

What is more, women do not put the tall sugar cane at a random spot in the cow dung figure but right in the middle of an equally disproportionally big navel (

nabhi). Rising up from the navel, the cane looks like an umbilical cord, feeding and sustaining new life. Although the women did not explicitly mention this, and some even said they put the cane there for no other reason than that it was the most solid part of the cow dung figure, the navel is a recurring key symbol in Hinduism as well; it generally refers to the birth of the universe and the divine world. The navel is also one of the seven

chakra’s, energy centres in human bodies which are considered in Hindu health and yoga practices. It is significant that this particular navel chakra is linked to the goddess Lakshmi who reigns over Divali, refers to riches and abundance, and is associated with fertility and the potency of the earth (

Elgood 2000, pp. 75–76). Putting the sugar cane into the navel is thus an act of visualising Lakshmi, making her strong and beautiful, and activating her as a bringer of good luck and fertility.

The reference to fertility and family building is

explicitly visible in the variations some women made on the figure of two male figures. Instead of two male figures, there sometimes was a male figure (with a penis) and a female figure (with breasts) with the sugar cane put in the woman’s navel. One woman deviated from the two-figure composition by modelling three human figures representing a complete family: a father, mother and male child in between (

Figure 15). These deviations show how women translate the mythical images of gods and landscapes into familiar images of family prosperity and fertility.

7.6. Five Images Conflating in One Cow Dung Figure

By focusing, not only on mythical or verbatim explanations of the Govardhan, but also on material forms, ritual gestures, and key symbols in the ritual, I disentangled five meaningful images. The changing faces of the figure vary in the same way as

Lodrick (

1987, pp. 109–11) found that the ritual varies across North India: from being explicitly associated to Krishna (the first two images described, with the first being connected to a local myth and the second to the pan-Indian myth), to being less directly associated to Krishna (the third image described), and to not at all being associated to Krishna (the last two images described). Women’s Govardhan puja in Rajasthan thus entails more than ‘a cow dung anthropomorphic representation of the Govardhan hill’, as is argued by

Vaudeville (

1980, pp. 3–4). The multiple imagery also transcends the dominant explanation of the ritual being uniquely based on the myth of “govardhana-dharana.” Women’s lived religion does

not exclude Sanskritic classical and authoritative texts (see also

Pintchman 2005, p. 12) but it entails much more.

Taken all five images together, the constant factor is what the figure is: cow dung; and what the cow dung generates: fertility and abundant life. Women’s material prayer thus is a prayer for fecundity. All that women knead in the dung are signs of prosperity: access to natural resources (cattle, land, water, mountains and forests), a healthy and beautiful family, and plenty of food. This prosperity is based on a moral economy in which the women are central actors but not the only ones. During Govardhan puja they express their dependence on cows, fields, lakes and mountains, their husbands, and their beloved gods, in attaining this prosperity. The ritual puts women’s work with cow dung central and celebrates it as the vital link in the village economy. Cow dung is not just a useful crafting material, the very substance itself is divine and god-like and an object of loving care and devotion.

8. Women Performing Beauty and Solidarity at the Doorstep

After the iconographic interpretation of the visual layers of Govardhan, I want to focus on two more dimensions of the ritual to complement my analysis of women’s Govardhan puja: (1) the performative dimension of women singing songs, and (2) the doorstep as the location where both kneading and singing take place. Women’s prayer is not restricted to the puja at the end of the ritual (merely being a standardized ending of the ritual); it is articulated in the cow dung as well as the songs accompanying the kneading of cow dung. The songs women sing add to the kneaded prayers of ‘fertile natural environment’ and the ‘fertile family’ (described above).

8.1. Singing Beauty and Solidarity

In the process of tenderly kneading and beautifying the figures of father and son, some women sing about family beauty and prosperity and thereby confirm bonds of solidarity. In Badi, I found Brahmin women expressing unity by beautifying themselves as brides (wearing red coloured saris and plentiful jewellery) and collectively singing songs for Govardhan (

Figure 16). Sitting in a (half) circle in front of the gate, each woman works on a different part of the cow dung figure and follows the (often older) woman who broke into a song. These songs are articulated over Govardhan and alternately directed to all women of the patrilineal household (those present and absent). The singing is an intimate women’s affair. When women knead the two male figures with penises and testicles complete, and praise the fruits of male and female sexuality, men discretely withdraw. While creating solidarity between the women of the household, the ritual draws a spatial boundary between men and women though simultaneously celebrates their complementarity.

In the repertoire of songs I recorded during the event, four thematic songs recur across the different families. Together they illustrate women’s view of a beautiful and fertile family. A first song directs a prayer for the fertility of fields, families, and cows and briefly runs as follows: ‘may the field be full of crops, may the bullock cart leave the field full of good grain, may we have sons and daughters, may no one remain unmarried, may we have daughters-in-law and sons-in-law, and may we have good cows producing lots of milk, so we can do the churning every day.’ A second song is sung for the in-married women of the family: ‘Give me good fields, good cows, good wealth, my mother-in-law is doing all the work and I become the owner of the house.’ A third song remembers and praises the out-married daughters of the family: ‘you are far away, all alone, who cares for you, who will bring you home for festival?’ This is answered by women responding: ‘my younger brother will come and bring me beautiful sari and beautiful blouse, bring me colourful jewellery, and bring me back home for festival.’ A fourth songs is sung for the unmarried daughters: ‘Please marry me in a wealthy family so I can wear a half kilo gold and I live in a big house, all my jewellery is gold, marry me to a rich family with many cows and I become the head of that family.’ Rather than deploring a subdominant position in the household, women express in their songs their ambitions and the high demands they make on their conjugal home. Although daily practice may of course deviate from these ideals, the songs express that women do not expect receiving little gold, being cut from the natal house or staying subordinate to the mother-in-law.

These songs also reveal that an auspicious house accommodates a good (=beautiful) family which means complete with humans and animals, sustained by animals and fields, and balanced by heterosexual marriage and offspring of both sexes. The absence of married-out daughters has to be balanced by the presence of married-in daughters-in-law, caring brothers travelling between the houses of parents and sisters, and sons-in-law complementing the family at a distance. While daughters-in-law aim for being the head of the family, the out-married daughters aim to return to the natal family as special guests at festive occasions. This female-centred view on the fertile and well-balanced family adds an important perspective to the visual image of father and son sculptured in cow dung and representing patrilineality. It underlines women’s important position in building a patrilineal family, women’s multiple belongings in houses of birth and houses of marriage, and that gender complementarity—in and outside the household—looks beautiful and entices good luck and abundant life. Women’s perception of a good family thus points at the continual links of inside/domestic and outside/public domains and the need to keep them connected.

8.2. The Doorstep as Crucial Crossing

All ritual activities during the Govardhan puja occur at the doorstep which manifests itself as a crossing between the intimate interior of the household and the public space of the street and community. Like the threshold design of kolam in South India, the Govardhan “exists where the house meets the outside world, where the private and familial realm encounters the community and the shared public common” (

Nagarajan 2019, p. 8). By celebrating with Govardhan the doorstep as a crucial place, women show they have multiple outward orientations—as wives, daughters, cattle raisers and farmers—and do not confine their lives to the domain inside.

During the ritual women sing about women’s auspicious mobility over that crossing, leaving as out-married brides or entering as in-married brides. Also, a family’s nostalgia for the out-married daughters and the daughters’ wish for return visits is expressed in the songs at the doorstep. The doorstep is also a crossing of gods, cows and wealth, made possible by the women of the household. In their daily outdoor activities as farmers and cattle breeders, women cross the doorstep to procure economic security. Women and cows share the crossing as they together produce the wealth that goes out to the field in order to bring the wealth of the fields back home. During Divali women invite Lakshmi to cross the threshold on the third day and take the cows out of the shed on the fourth day. Lakshmi ritually enters the house to bring money and wealth. Cows enter the house to give birth and to give milk; their dung leaves the house to bring fertility to the fields and subsequently prosperity to the household.

Married women also share with Lakshmi their positioning at the crossing. The doorstep as transition place is dangerous and precarious and needs constant care and protection as not only positive but also bad energies may enter. As ‘Lakshmi’s of the house’, married women master the inward flow of auspiciousness and the outward flow of inauspiciousness. Together with Lakshmi, they play a central role as gatekeepers. By doing Govardhan puja women celebrate and sanctify their roles as protectors and caretakers of the household as well as their efforts to master the erratic natural environment on which they depend.

9. Conclusions

In this article, I have analysed women’s cow dung sculptures as multi-sensory prayers and showed that women craft in the sacred cow dung an affectionate intimacy with their human, natural and divine environment. By taking a material approach and looking at the figures from shifting perspectives, I found women’s Govardhan to be multiform and polysemic. Depending on the perspective one takes, the Govardhan changes his face while symbols of fertility recur. The central meaning of the Govardhan puja is situated right in the cow dung and its purifying and nourishing properties, bringing fertility to land, people and animals. The figure women knead in the cow dung reveals what makes people’s environment fertile: women’s careful attention, their bodily and devotional work, the gods and their blessings, human sexuality, and the material gifts of the natural world. The cow dung links the human, the natural and the divine world, as well as the male and female elements of those worlds, in a continuously repeated lifecycle. Cow dung travels as a gift between the human, the non-human and the divine world and connects them to each other in order to produce wealth: from cows to women to fields to food for family and cows. It also travels in a cycle of life: the fresh cow dung has to perish and resolve in order to grow and produce life again, which is visible in the ritual sequence of the Govardhan puja.

By studying the ritual from the perspective of gender and lived religion I disclosed women’s cosmology and their profound ritual and ecological knowledge that is captured in the cow dung sculpture. To date the ritual of cow dung kneading has been overlooked, either because of women mastering it, the waste material central to it, or perhaps its brief duration. My analysis points to the ritual as a gendered mode of communication. Women speak through their cow dung sculptures, not only to Govardhan and god Krishna, but also to each other and the wider society. They express their ideas about gender and human–nature relationships, and highlight the importance of their daily economic work. By embellishing the divine cow dung sculpture, women articulate how their family and natural environment should look like to be beautiful and balanced and consequently entice luck and prosperity. By jointly performing the ritual in public space, they confirm that women—together with cows—are key actors in achieving and maintaining the society’s wellbeing.

Rather than a divide between private–public, female–male, or subdominant–dominant, it is the distinction between inner and outer space that matters in the Govardhan puja. This distinction is symbolically and materially captured in the doorstep. Inner and outer space are distinguished but not divided. By doing the ritual right at the crossing women stress their position as gatekeepers, caring for and connecting the spaces. Both spaces are occupied by women and men, animals and gods. What matters is not that in one of these spaces certain genders are excluded or subjugated, but that in both inner and outer spaces negative forces and bad luck need to be expelled and positive energies and good luck introduced. To achieve this, men and women, animals and gods need to unite, not divide, in the balanced and ethical ways that are expressed in women’s cow dung sculptures.