Sacred Watersheds and the Fate of the Village Body Politic in Tibetan and Han Communities Under China’s Ecological Civilization

Abstract

:Power corresponds to the human ability not just to act but to act in concert. Power is never the property of an individual; it belongs to a group and remains in existence only so long as the group keeps together. When we say of somebody that he is “in power” we actually refer to his being empowered by a certain number of people to act in their name. The moment the group, from which the power originated to begin with... disappears, ‘his power’ also vanishes.Hannah Arendt, On Violence

1. Introduction

“Yu divided the land [and] following the course of the hills, he cut down the trees. He determined the highest hills and largest rivers (in the several regions) … [to mark off boundaries]. The Min and Bo hills were cultivated, the Tuo and Qian streams routed through their proper channels, and sacrifices offered to the Cai and Meng hills for the regulation of the surrounding country. Lands of the wild tribes around the He (Yellow River) were successfully subdued. The soil of this province was greenish and light. Its fields were the highest of the lowest class; and its contribution of revenue was the average of the lowest class, with proportions of the rates immediately above and below. Its articles of tribute were the best gold, iron, silver, steel, flint stones to make arrowheads, and sounding stones; with the skins of bears, foxes, and jackals, and nets woven of their hair. From the hills of Xiqing they came by the course of the Huan River; floated along the Qian, and then crossed the lands to the Mian; passed to the Wei, and (finally) ferried across the He.”

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Animate Landscapes and Environmental Activism in Tibetan Communities of NW Yunnan

“…the mountain cult…belongs to what I call the ‘unwritten tradition of the laity.’ This is because neither Buddhist nor Bonpo clergy have any significant role in the cult, although it represents a supremely important element underlying Tibet’s national identity. By the mountain cult I mean particularly the secular worship of the mountain divinity (yul-lha, gzhi-bdag), who is usually depicted in the style of a traditional warrior and is worshipped as an ancestor or an ancestral divinity for protection.”

“The mountain can hide/conceal (cang藏) people who enter its domain. The zhidak can cause you to be lost in the mountains for 6–7 days or more and you never get hungry. You are under a kind of enchantment. The deity/spirit (shen 神) captivates you. Horse, cattle, and yak droppings turn into momo (steamed buns) that you can eat. You come out 6–7 days later convinced that you were in a kind of paradise. Two American doctors had this happen in 2003 when they were trekking here in Hamugu. They were lost for 3–4 days with a guide from Weixi County, and they said they never felt hungry. They even came back the next year! Two people from the village next to ours, a woman and her grandson, were “hidden” in the 1980s. Everyone thought they died, but no. They were lost for about a week or two.”

“These old men started hunting before Liberation because their families were poor—their living conditions were difficult, so they took up hunting. They hunted mostly musk deer and bears because of their high value, and this allowed them to make a go of it. At the age of sixty they stopped hunting. Now they regret having done it. Over the years their families and their livestock have suffered misfortunes of various kinds. Divinations at the monastery show that they’ve been punished for not respecting the zhidak. [In similar fashion] government-organized timber-felling destroyed thousands of ancient trees—a serious misfortune. We now protect the forests and I am very happy; not destroying the sacred mountains and lakes is excellent. We Tibetans believe that wild animals living in the realm of the deity-mountain have relationships with the zhidak, the ecology, the local people, and nature that is like the relationship between you and me. All are living beings. Conflicts between animals are like conflicts between people; if you violate someone they will take action against you ….”

“The cable car system that is being built on Shika mountain is already having severe environmental impacts, and when droves of tourists ride up to the summit there will be destruction that takes forms not immediately visible to the eye. Already there are mudslides occurring in several nearby villages and the destruction is about to increase. Only by protecting the ecology, the zhidak, and the sacred lakes can there be peace, and only after there is peace can there be prosperity.”

“Two or three years ago, a family with a nine- or ten- year-old boy was pulling trees down the mountain; the mother was down below collecting firewood, and a tree slid down the mountain, killing her. Later, through ritual [involving a medium], we inquired about the situation, asking, “Do you think the zhidak has been offended?” and the voice of the mother coming off the mountain said that it was so … So now we say, the zhidak will always demand its debt from those who offend it.”.

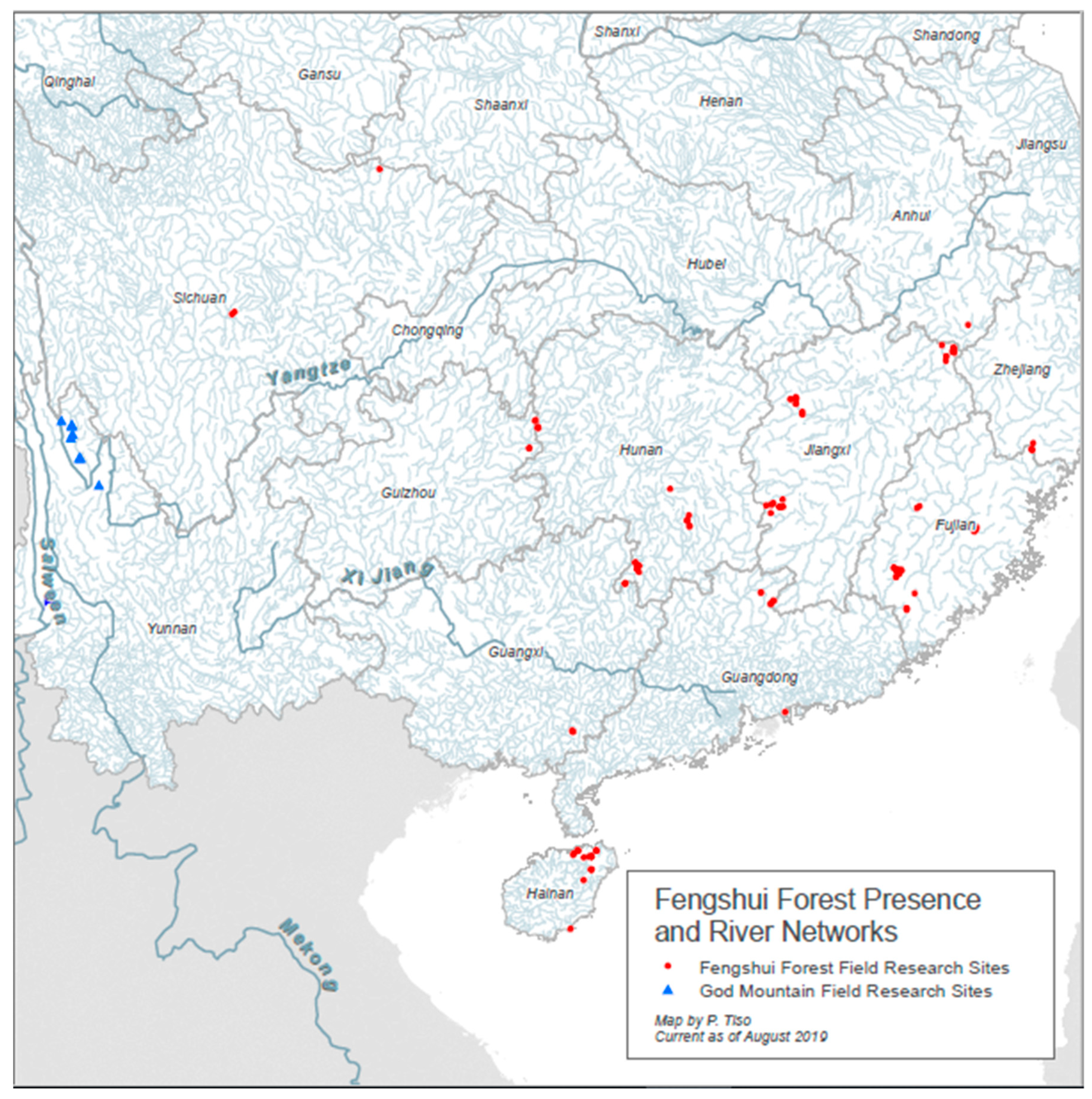

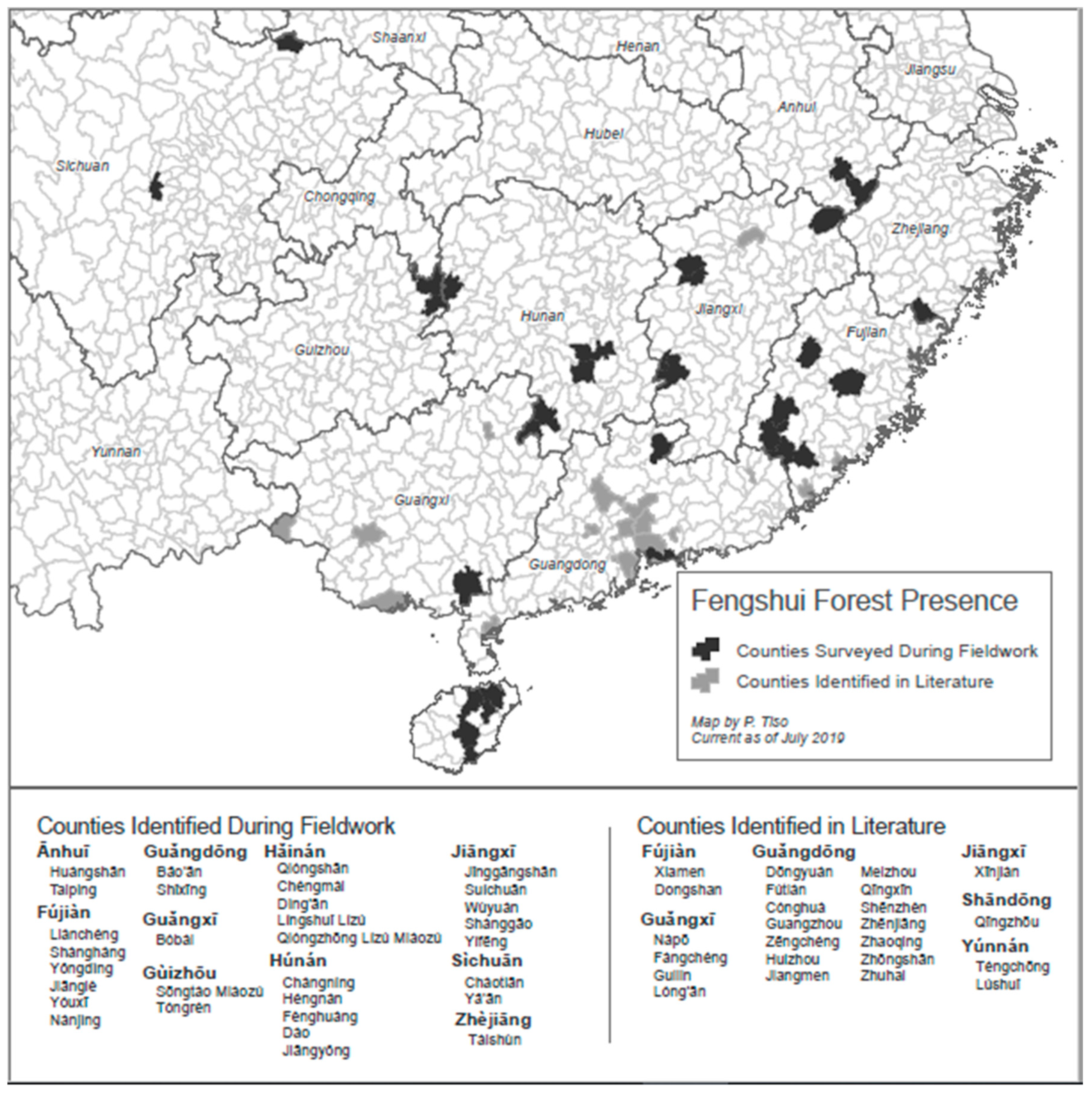

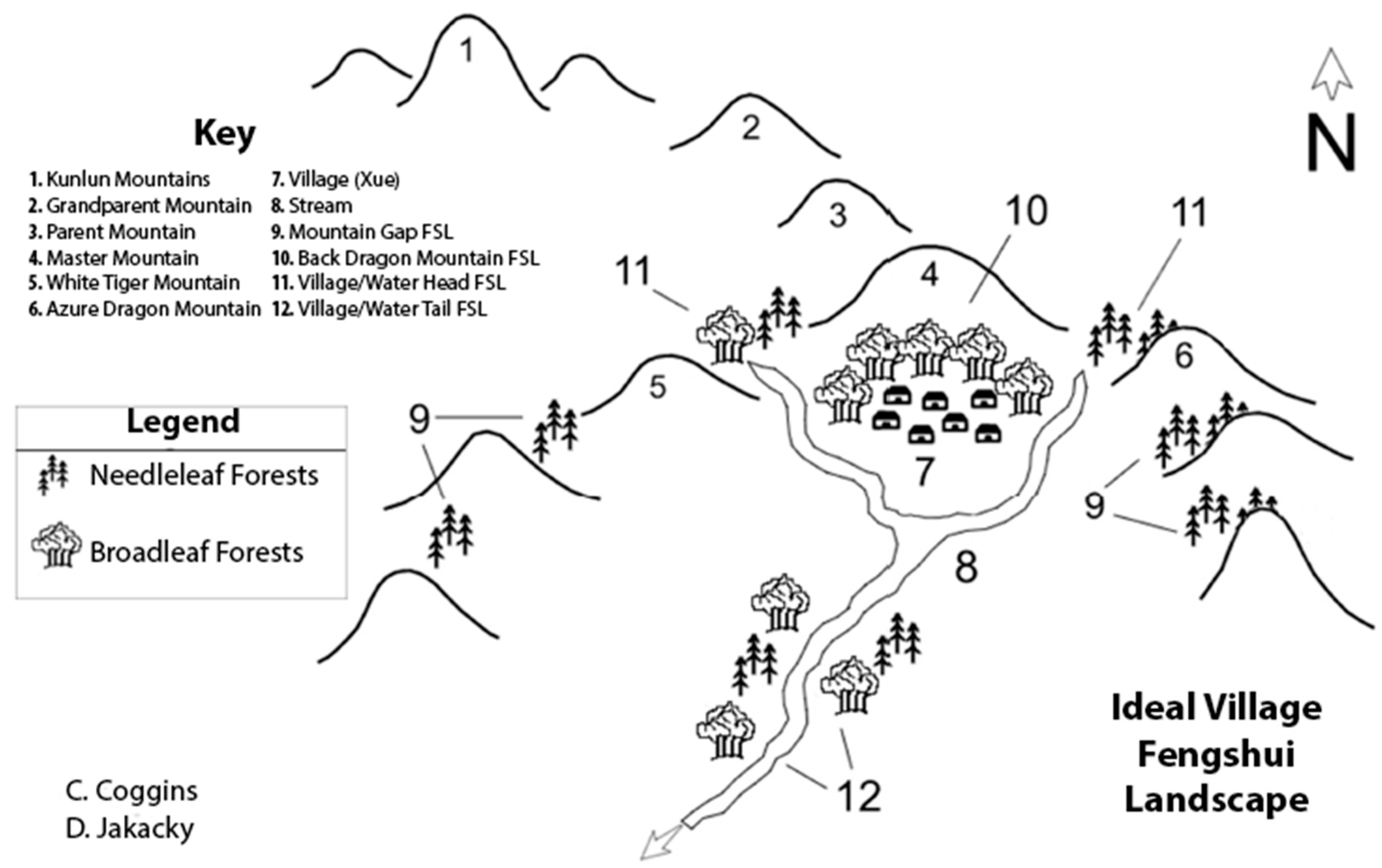

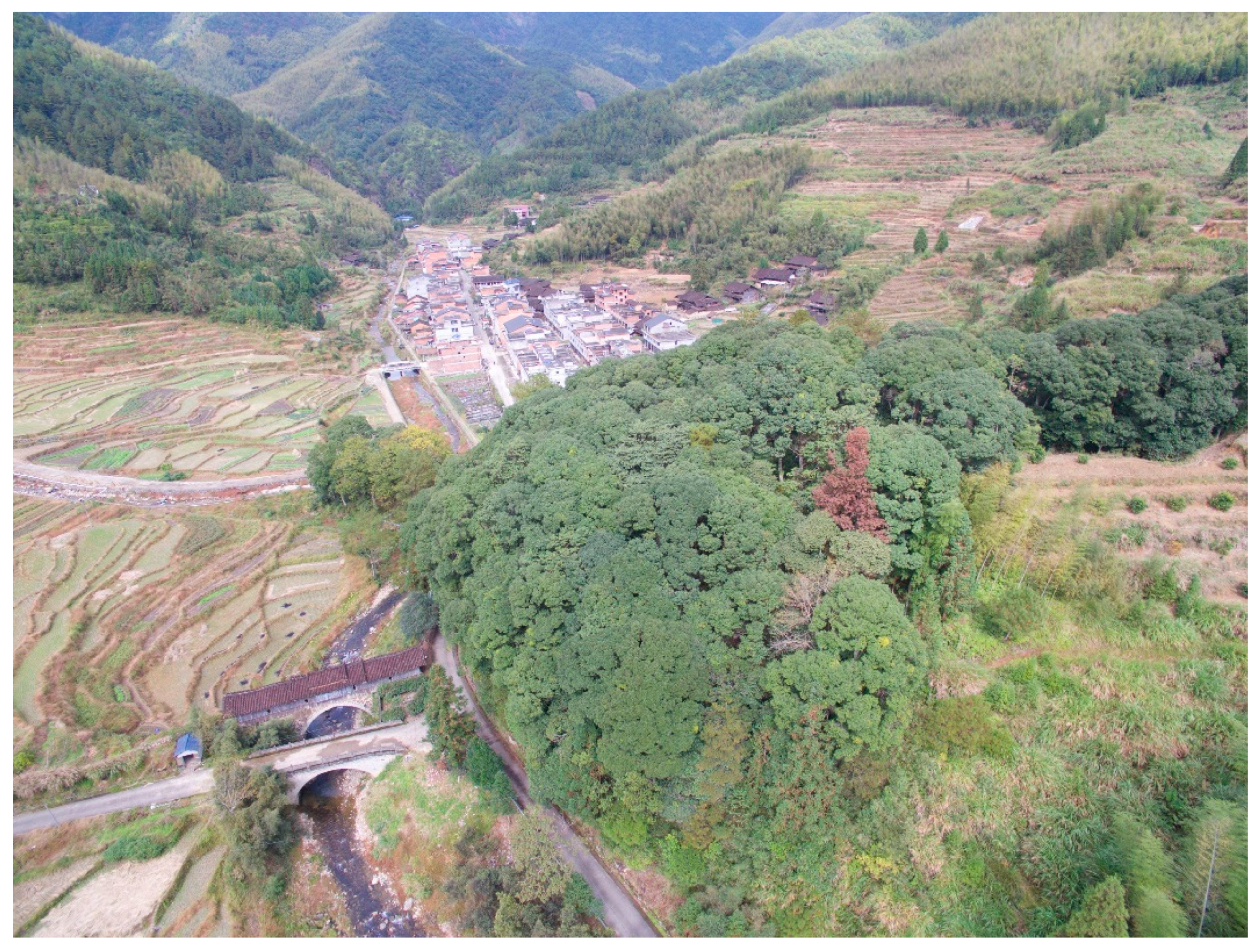

3.2. Vital Landscapes and Environmental Activism in Han Communities in Southern China

“The Classic says, qi rides the wind and scatters, but is retained when encountering water. The ancients collected it to prevent its dissipation, and guided it to assure its retention. Thus it was called fengshui (wind-water). According to the laws of fengshui, the site that attracts water is optimal, followed by the site that catches wind… Terrain resembling a palatial mansion with luxuriant vegetation and towering trees will engender the founder of a state or prefecture.”(Guo Pu, The Book of Burial; Zhang 2004)

4. Discussion

“New progress has been made in the construction of ecological civilization, the main functional area system has been gradually improved, the discharge of major pollutants has continued to decrease, and the level of energy conservation and environmental protection has improved significantly.”(CTB 2016)

“Strengthen the construction of an ecological civilization system, establish and improve an ecological risk prevention and control system, enhance the ability to respond to sudden ecological environmental incidents, and ensure national ecological security … Implement ecological space use control, delineate and strictly observe the ecological protection red line, ensure that ecological functions are not reduced, the area is not reduced, and that natural conditions are not altered. Establish a total forest, grassland and wetland management system. Accelerate the establishment of a diversified ecological compensation mechanism and improve the linkage mechanism between financial support and ecological protection effectiveness. Establish a green taxation system covering the exploitation, consumption, pollution discharge and import and export of resource products. Study and establish an ecological value assessment system, explore the preparation of natural resource balance sheets, and establish physical volume accounting. Implement the audit of the loss of natural resources assets of leading cadres. Establish and improve the ecological environment damage assessment and compensation system, and implement the lifelong investigation system for damage liability.”(CTB 2016)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abe, Ken-ichi. 1997. Forest History in Yunnan, China (I): Tibetan God Mountain and Its Protected Forest in Jungden [Zhongdian]. Japanese. Southeast Asian Studies (SEAS) 35: 422–44. [Google Scholar]

- Allerton, Catherine. 2009. Introduction: Spiritual Landscapes of Southeast Asia. Anthropological Forum 19: 235–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1970. On Violence. New York: Houghton-Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Stephen. 1978. The Cult of Tārā: Magic and Ritual in Tibet (Hermeneutics: Studies in the History of Religions). Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bird-David, Nurit. 1999. ‘Animism’ Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology.” Special issue, “Culture: A Second Chance? Current Anthropology 40: 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Bruce. 2006. Towards a New Earth and a New Humanity: Nature, Ontology, Politics. In David Harvey: A Critical Reader. Edited by Castree Noel and Derek Gregory. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 191–222. [Google Scholar]

- Bruun, Ole. 2008. An Introduction to Feng Shui. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castree, Noel. 2012. Making Sense of Nature. London: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Nancy. 2003. Breathing Spaces: Qigong, Psychiatry, and Healing in China. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Bixia, Chris Coggins, Jesse Minor, and Yaoqi Zhang. 2018. Fengshui forests and village landscapes in China: Geographic extent, socioecological significance, and conservation prospects. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 31: 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coggins, Chris. 2003. The Tiger and the Pangolin: Nature, Culture, and Conservation in China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coggins, Chris. 2014. When the Land is Excellent: Village Feng Shui Forests and the Nature of Lineage, Polity and Vitality in Southern China. In Religion and Ecological Sustainability in China. Edited by Jay Miller, Dan Smyer Yu and Peter van der Veer. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Coggins, Chris. 2017. Conserving China’s Biological Diversity: National Plans, Transnational Projects, Local and Regional Challenges. In Routledge Handbook of Environmental Policy in China. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Coggins, Chris, and Tessa Hutchinson. 2006. The Political Ecology of Geopiety: Nature Conservation in Tibetan Communities of Northwest Yunnan. Asian Geographer 25: 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coggins, Chris, and Gesang Zeren. 2014. Animate Landscapes: Nature Conservation and the Production of Agropastoral Sacred Space in Shangrila. In Mapping Shangrila: Contested Landscapes of the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands. Edited by Emily T. Yeh and Chris Coggins. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coggins, Chris, Jesse Minor, Bixia Chen, Yaoqi Zhang, Peter Tiso, and Cem Gultekin. 2019. China’s Community Fengshui Forests—Spiritual Ecology and Nature Conservation. In Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature in Protected Areas. Edited by Bas Verschuuren and Steve Brown. New York: Routledge, pp. 227–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, Denis. 2000. Geopiety. In The Dictionary of Human Geography, 4th ed. Edited by R. J. Johnston, Derek Gregory, Geraldine Pratt and Michael Watts. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell, pp. 308–9. [Google Scholar]

- CTB (Compilation and Translation Bureau, Central Committee of the Communist Party of China). 2016. The 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China—2016–2020. Beijing: Central Compilation and Translation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Da Col, Giovanni. 2007. The View from Somewhen: Events, Bodies and the Perspective of Fortune around Khawa Karpo, a Tibetan Sacred Mountain in Yunnan Province. Inner Asia 9: 215–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beauvoir, Simone. 1971. The Second Sex. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Ba, and Chezong Village, Shangrila County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China. 2005. Personal communication.

- Descola, Philippe. 2013. Beyond Nature and Culture. Chicago and London: University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Dorje, Sinang, and Adong Village, Deqin County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China. 2006. Personal communication.

- Duara, Prasenjit. 2015. The Crisis of Global Modernity: Asian Traditions and a Sustainable Future. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea, and Laurence E. Sullivan. 1987. Hierophany. In The Encyclopedia of Religion. New York: Macmillan, vol. 6, pp. 313–17. [Google Scholar]

- Elvin, Mark. 2004. The Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Wei. 1992. Village Fengshui Principles. In Chinese Landscapes: The Village as Place. Edited by Ronald G. Knapp. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Feuchtwang, Stephan. 2002. An Anthropological Analysis of Chinese Geomancy. Bangkok: White Lotus Company. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, Amy E., Brett A. Bryan, Alexander Buyantuev, Liding Chen, Cristian Echeverria, Peng Jia, Lumeng Liu, Qin Li, Zhiyun Ouyang, Jianguo Wu, and et al. 2019. Ecological Civilization: Perspectives from Landscape Ecology and Landscape Sustainability Science. Landscape Ecology 34: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geall, Sam, and Adrian Ely. 2018. Narratives and Pathways Towards an Ecological Civilisation in Contemporary China. China Quarterly 236: 1175–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Amitav. 2016. The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goron, Coraline. 2018. Ecological Civilisation and the Political Limits of a Chinese Concept of Sustainability. China Perspectives 4: 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Chuanyou. 2012. Fengshui Landscapes: The Culture of Fengshui Forests. Nanjing: Southeastern University Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna J. 2008. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hase, Patrick H., and Man-Yip Lee. 1992. Sheung Wo Hang: A Village Shaped by Fengshui. In Chinese Landscapes: The Village as Place. Edited by Ronald G. Knapp. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 2019. Being and Time. New Eastford: Martino Fine Books, First publish 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, John B. 2010. Cosmology and Concepts of Nature in Traditional China. In Concepts of Nature. Leiden: Brill Publications, pp. 181–97. [Google Scholar]

- Holbraad, Martin, and Morten Axel Pedersen. 2017. The Ontological Turn: An Anthropological Exposition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huan, Qingzhi. 2016. Socialist Eco-civilization and Social-Ecological Transformation. Capitalism Nature Socialism 27: 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Toni. 1999. The Cult of Pure Crystal Mountain: Popular Pilgrimage and Visionary Landscape in Southeast Tibet. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Toni, and Poul Pedersen. 1997. Meteorological Knowledge and Environmental Ideas in Traditional and Modern Societies: The Case of Tibet. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 3: 577–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmay, Samten. 1994. Mountain Cults and National Identity in Tibet. In Resistance and Reform in Tibet. Edited by Robert Barnett and Shirin Akiner. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, Eduardo. 2013. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kolas, Ashild. 2008. Tourism and Tibetan Culture in Transition: A Place Called Shangrila. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2004. Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1987. Time and the Other. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhen, and Sun Yat-sen Univeristy, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China. 2011. Personal communication.

- Litzinger, Ralph. 2004. The Mobilization of ‘Nature’: Perspectives from North-west Yunnan. China Quarterly 178: 488–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorimer, Jamie. 2012. Multinatural Geographies for the Anthropocene. Progress in Human Geography 36: 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Jianzhong, and Jie Chen, eds. 2005. Zangzu wenhua yu shengwu duoyangxing baohu [Tibetan Culture and Biodiversity Conservation]. Kunming: Yunnan Science and Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Makley, Charlene. 2014. The Amoral Other: State-led Development and Mountain Deity Cults Among Tibetans in Amdo Rebgong. In Mapping Shangrila: Contested Landscapes of the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands. Edited by Emily T. Yeh and Chris Coggins. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, Robert B. 2012. China: Its Environment and History. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, James, Dan Smyer Yu, and Peter van der Veer, eds. 2014. Religion and Ecological Sustainability in China. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Jason W., ed. 2016. Anthropocene or Capitalocene: Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism. Oakland: PM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, Robert K., Sina Norbu, Ma Jianzhong, and Guo Jing. 2003. Kawagebo Snow Mountains Sacred Natural Sites Case Study. Paper presented at the Fifth World Parks Congress, Durban, South Africa, September 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Obeyesekere, Gananath. 2002. Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist, and Greek Rebirth. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paba, Aun, and Nedu Village, Shangrila County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China. 2006. Personal communication.

- Quijada, Christine, and Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT, USA. 2018. Personal communication.

- Robbins, Paul. 2011. Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiba, Lazong, and Hamugu Vililage, Shangrila County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China. 2005. Personal communication.

- Ruiba, Lazong, and Hamugu Vililage, Shangrila County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China. 2006. Personal communication.

- Ruiba, Lazong, and Songzanlin Monastery, Shangrila County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China. 2008. Personal communication.

- Scott, James C. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, James C. 2017. Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smyer Yü, Dan. 2015. Mindscaping the Landscape of Tibet: Place, Memorability, Ecoasthetics. Boston and Berlin: Walter de Guyter. [Google Scholar]

- Sponsel, Leslie E. 2012. Spiritual Ecology: A Quiet Revolution. Santa Barbara, Denver and Oxford: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Studley, John, and Horsley. 2019. Spiritual Governance as an Indigenous Behavioural Practice: Implications for Protected and Conserved Areas. In Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature in Protected Areas: Governance, Management and Policy. Edited by Bas Verschuuren and Steve Brown. London and New York: Earthscan Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Sian. 2010. Ecosystem Service Commodities’ a new Imperial Ecology? Implications for Animist Immanent Ecologies, with Deleuze and Guattari. New Formations 69: 111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Bron. 2010. Dark Green Religion: Nature Spirituality and the Planetary Future. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Yi-Fu. 1976. Geopiety: A Theme in Man’s Attachment to Nature and to Place. In Geographies of the Mind. Edited by David Lowenthal and Martyn Bowden. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuuren, Bas, and Steve Brown, eds. 2019. Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature in Protected Areas: Governance, Management and Policy. London and New York: Earthscan Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuuren, Bas, and Naoya Furuta. 2016. Asian Sacred Natural Sites: Philosophy and Practice in Protected Areas and Conservation. London and New York: Earthscan Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuuren, Bas, Robert Wild, Jeffrey A. McNeely, and Gonzalo Oviedo. 2010. Sacred Natural Sites: Conserving Nature and Culture. London and Washington: Earthscan Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 1998. Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4: 469–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaosong, and Zhongdian, Shangrila County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China. 2006. Personal communication.

- Wangu, Pasang, and Hildegard Diemberger. 2000. dBa’ bzhed: The Royal Narrative Concerning the Bringing of the Buddha’s Doctrine to Tibet. Vienna: Verlag Der Osterreichischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, Robert, and Keping Wu. 2017. Overnight Urbanization and Religious Change: Non-equilibrium Ecosystems in Southern Jiangsu. Paper presented at Conference on Environmental Justice and Sustainable Citizenship, Duke-Kunshan University, Suzhou, China, May 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, John Kirtland. 1966. Human Nature in Geography: Fourteen Papers, 1925–1965. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Gangjun. 2014. Fengjinglin (Scenic Forests) and the Beauty of the Jiangxi Countryside. Forests and Humankind 294: 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Yangzong, and Jisha Village, Shangrila County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China. 2006. Personal communication.

- Yeh, Emily. 2014a. Reverse Environmentalism: Contemporary Articulations of Tibetan Culture, Buddhism, and Environmental Protection. In Religion and Ecological Sustainability in China. Edited by Jay Miller, Dan Smyer Yu and Peter Van der Veer. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Emily. 2014b. The Rise and Fall of the Green Tibetan: Contingent Collaborations and the Vicissitudes of Harmony. In Mapping Shangrila: Contested Landscapes of the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands. Edited by Emily T. Yeh and Chris Coggins. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, Emily, and Chris Coggins, eds. 2014. Mapping Shangrila: Contested Landscapes of the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Youatt, Raffi. 2017. Personhood and the Rights of Nature: The New Subjects of Contemporary Earth Politics. International Political Sociology 11: 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeren, Gesang, Lazong Ruiba, and Hamugu Village, Shangrila County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China. 2004. Personal communication.

- Zeren, Gesang, and Hamugu Village, Shangrila County, Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan, China. 2005. Personal communication.

- Zhang, Juwen. 2004. A Translation of the Ancient Chinese: The Book of Burial (Zang Shu) by Guo Pu (276–324). Lewiston: Edwin Mellon Press, pp. 58–74. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | In a special edition of Anthropological Forum focusing on contemporary indigenous spiritual phenomena in western China, Da Col (2007, p. 308) states that the contributors refuse “…to engage with the concept of animism or subscrib[e] to totalising ‘cosmologies’…prefer[ring] to extract the eventfulness of haphazard and uncertain interaction with spirits. The articles suggest that rather than relying on an ideal typification of ontologies of nature in Philippe Descola’s sense, or developing an alternative mode of identification encompassing China’s cosmologies…through the notion of ‘homologism’—one should ethnographically accept that borderland societies discussed in this issue do not appear to present a unitary conception or ‘cosmology’ of what nature is.” Similarly, Quijada, a scholar-researcher of current Mongolian shamanic practice, views animism as a flexible “strategy or tactic” rather than a cosmology. |

| 2 | Literature on the Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene, and other related terms designed to capture the massive anthropogenic transformation of global biogeochemical processes exceeds the scope of this paper. I cite several relatively recent works that take rather eclectic and expansive perspectives on this subject. |

| 3 | Geopiety, a term once popular in the field of cultural geography, denotes reverence toward, and worship of, terrestrial features (Wright 1966; Tuan 1976; Cosgrove 2000). In my work, geopiety and geopolity are interchangeable. Although the term may be dated, I use it as a placeholder for both “animate landscapes” and “vital landscapes” in order to mark a distinction between the two. |

| 4 | In concise terms: 1. Define clear group boundaries. 2. Match rules governing use of common goods to local needs and conditions. 3. Ensure that those affected by the rules can participate in modifying the rules. 4. Make sure the rule-making rights of community members are respected by outside authorities. 5. Develop a system, carried out by community members, for monitoring members’ behavior. 6. Use graduated sanctions for rule violators. 7. Provide accessible, low-cost means for dispute resolution. 8. Build responsibility for governing the common resource in nested tiers from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system (Ostrom 1990). |

| 5 | The classic, dBa’ bzhed (an account of the advent of Buddhism to Tibet) describes how Padmasambhava attempted to create what appears to be a series of water control projects within the kingdom. These were rejected by King Muné Tsenpo (late 8th century), who feared that the tantric warrior’s power would become too great if he was allowed to orchestrate the rerouting of rivers and other waterways. In the dBa’ bzhed, his exhortation to Padmasambhava expresses significant anxiety: “The bTsan po [Muné Tsenpo] presented the mKhan po [Padmasambhava] with many offerings and said: “[Reverend] mKhan po! You let the holy doctrine come to the country of Tibet. You have already achieved what was in my mind: you are bound by oath the gods and nāga and so on. That is enough. It is not necessary that the sand of Ngam should be covered with meadows and that springs appear. It is enough that there is the river called Yar khyi in my own land. [Acharya] please, please return to [your] homelands!” After this admonition, some twenty of the king’s minions attempted to assassinate Padmasambhava as the latter was returning to India, but they “…were frozen like paintings, unable to speak and move, and he passed straight through them…” (Wangu and Diemberger 2000, pp. 58–59). |

| 6 | Huber (1999, p. 23) makes note of “two types of cult mountains in Tibet: “In addition to néri mountains …there exists a widespread cult mountain type identified more exclusively with the yüllha (“god of the locale”) and shidak (“owner of the base”) deities. These genii are generally understood as local and regional territorial gods and goddesses, whose worship apparently predates the intensive introduction of Indian religious systems into Tibet.” See Huber (1999, pp. 23–25) for a thorough delineation of how the former are “mandalized” (Buddhicized) syncretic cults that include many features of the latter. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coggins, C. Sacred Watersheds and the Fate of the Village Body Politic in Tibetan and Han Communities Under China’s Ecological Civilization. Religions 2019, 10, 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10110600

Coggins C. Sacred Watersheds and the Fate of the Village Body Politic in Tibetan and Han Communities Under China’s Ecological Civilization. Religions. 2019; 10(11):600. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10110600

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoggins, Chris. 2019. "Sacred Watersheds and the Fate of the Village Body Politic in Tibetan and Han Communities Under China’s Ecological Civilization" Religions 10, no. 11: 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10110600

APA StyleCoggins, C. (2019). Sacred Watersheds and the Fate of the Village Body Politic in Tibetan and Han Communities Under China’s Ecological Civilization. Religions, 10(11), 600. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10110600