Constructing the Problem of Religious Freedom: An Analysis of Australian Government Inquiries into Religious Freedom

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Context and Methodology

WPR understands policy as ‘discourse’ constructed in the social, historical and political contexts that give it meaning: ‘policy must be recognised as a cultural product: it is context-specific. More than this, policy is involved in constituting culture by making meaning: as well as making problems and solutions, policy discourses make “facts” and make “truths”’ (Goodwin 2012, emphasis added).policies and policy proposals give shape and meaning to the ‘problems’ they purport to ‘address’. That is, policy ‘problems’ do not exist ‘out there’ in society, waiting to be ‘solved’ through timely and perspicacious policy interventions. Rather, specific policy proposals ‘imagine’ ‘problems’ in particular ways that have real and meaningful effects.

Rather than accepting the designation of some issue as a ‘problem’ or a ‘social problem’, we need to interrogate the kinds of ‘problems’ that are presumed to exist and how these are thought about. In this way we gain important insights into the thought (the ‘thinking’) that informs governing practices.

- WPR1

- ‘What’s the problem… represented to be in a specific policy or policies?’

- WPR2

- ‘What deep-seated presuppositions or assumptions… underlie this representation of the “problem” (problem representation)?’

- WPR3

- ‘How has this representation of the “problem” come about?’

- WPR4

- ‘What is left unproblematic in this problem representation? Where are the silences? Can the “problem” be conceptualized differently?’

- WPR5

- ‘What effects (discursive, subjectification, lived) are produced by this representation of the “problem”?’

- WPR6

- ‘How and where has this representation of the “problem” been produced, disseminated and defended? How has it been and/or how can it be disrupted and replaced?’ (Bacchi 2018, p. 5).

3. The Reports

4. Analysis

4.1. Religious Diversity

The report recommended the development of a federal Religious Freedom Act to protect the freedom of those from minority religious groups, a proposal that HREOC/AHRC has not repeated but which, more recently, has been advocated by conservative religious groups and politicians but rejected by the Ruddock Review as unnecessary.Australians face the continuing challenge of creating a society in which everyone is truly free to hold a religion or belief of his or her choice and in which cultural and religious diversity is a source of advantage, benefit and good rather than a cause of disharmony and conflict.

The representation of the religious diversity problem assumes (WPR2) that prejudice arises not only in the context of a pluralistic society but as a direct result of religious diversity, contributed to by a lack of religious literacy in the community. One of the most common recommendations in the review reports is for more and/or improved education.Minority religious groups within a nation can find themselves in a very difficult position, even in a society as nominally ‘tolerant’ as Australia. This is especially so for those with beliefs and practices that can be seen as ‘strange’. The consequences for the exercise of freedom of religion and belief can be serious.

The role of Australian governments in managing diversity was often expressed in submissions and consultations in terms of ‘the majority’, ‘the minorities’, and their respective rights. Minority faiths called for accommodations for practices that were within common law, and for equality in all matters; the majority expressed concerns about the rights of minorities competing with the rights of the majority.

The majority is generally a Christian majority… Managing and/or balancing minority and majority rights was frequently raised in submissions and consultations, and it was suggested that governments need to be wary of accommodating the rights of minorities at the risk of encroaching on the rights of the majority.(Bouma et al. 2011, p. 53, emphasis added)

DRC is also unique among the reports in drawing attention to how majority or mainstream religious groups are spared the discrimination suffered by minority religious groups for not dissimilar beliefs and practices:In the beginning, there were the people, the law and the land, and so it remained for 40,000 years. Then Australia was colonised by an aggressive, white, Protestant civilisation, which had a devastating impact on the intricate web of relationships between Aboriginal men and women and their land.

This is a matter that is left unproblematised in future reports, as is the privileging in the language of law of a Christian understanding of religion, and the law itself which ‘allows too much leeway in supporting institutional power under current interpretations of the establishment clause’ (New South Wales Anti-Discrimination Board 1984, p. 5).Even though mainstream religious groups are regularly accused of “getting away with murder”, an expression of resentment about their power, it is the minority religious groups on whom these attitudes principally rebound. They are often castigated for beliefs and practices for which parallels can be easily found in major religious organisations.

4.2. Balancing Rights

The Board supported exceptions to anti-discrimination law that allowed religious schools to discriminate in student admissions (on religious grounds) but was concerned about teachers being fired ‘because their personal lives and opinions did not reflect orthodox Church practices in such matters as marriage, divorce, abortion and homosexuality’ (New South Wales Anti-Discrimination Board 1984, p. 425).the thorniest problems… for it is in education that we find the most contention about such apparent paradoxes in determining which rights take priority over others: parents’ rights to have their children educated in the beliefs of their choice or no belief at all, religious groups’ rights to perpetuate traditions and beliefs by passing their culture on to the next generation, and the right children have to receive an education that adequately prepares them for the world.(New South Wales Anti-Discrimination Board 1984, p. 290, emphasis added)

Both DRC and Article 18 stressed the need to limit religious exemptions in order to protect people from discrimination, especially on the basis of sexual orientation.This inquiry illustrates the importance of limiting the scope of exemptions for religious organisations under anti-discrimination law and in particular of not allowing absolute exemptions which have the potential to encourage prejudice and unfair treatment not related to any relevant belief.

Across all research data, calls to maintain current exemptions were strongly iterated by faith groups, particularly by Christian churches and organisations. Many participants in consultations identified feeling ‘under siege’ from those with a secular agenda, and expressed concern about anti-discrimination legislation, proposed changes to current exemptions, and the right to proselytise.

The balancing rights problematisation assumes that the granting of equality rights will always be a threat to religious freedom (WPR2). In the earlier reports, these rights included rights for women and people who are divorced. In the later reports it was LGBTIQ rights which are assumed to be incompatible with the right to religious freedom.Like other human rights it [religious freedom] must be exercised with a mindfulness of the rights of others, and has the potential to intersect and at times compete with other human rights such as equality before the law and government, and the freedoms of those without faith. The role of law should be to seek accommodation of competing rights and enlarge the freedom for all. Care must be taken to balance rights so that neither religious freedom nor any right with which it may intersect is granted an imbalanced privileging so as to permanently impair the enjoyment of the other.

the threats to religious freedom in the 21st century are arising not from the dominance of one religion over others, or from the State sanctioning an official religion, or from other ways in which religious freedom has often been restricted throughout history. Rather, the threats are more subtle and often arise in the context of protecting other, conflicting rights. An imbalance between competing rights and the lack of an appropriate way to resolve the ensuing conflicts is the greatest challenge to the right to freedom of religion.

Balancing rights the wrong way is identified, not merely as an Australian problem, but as the most significant universal threat to religious freedom.This is most apparent with the advent of non-discrimination laws which do not allow for lawful differentiation of treatment by religious individuals and organisations. It is also manifested in a decreasing threshold for when religious freedom may be limited… While religious exemptions within non-discrimination laws provide some protection, these place religious freedom in a vulnerable position with respect to the right to non-discrimination, and do not acknowledge the fundamental position that freedom of religion has in international human rights law.

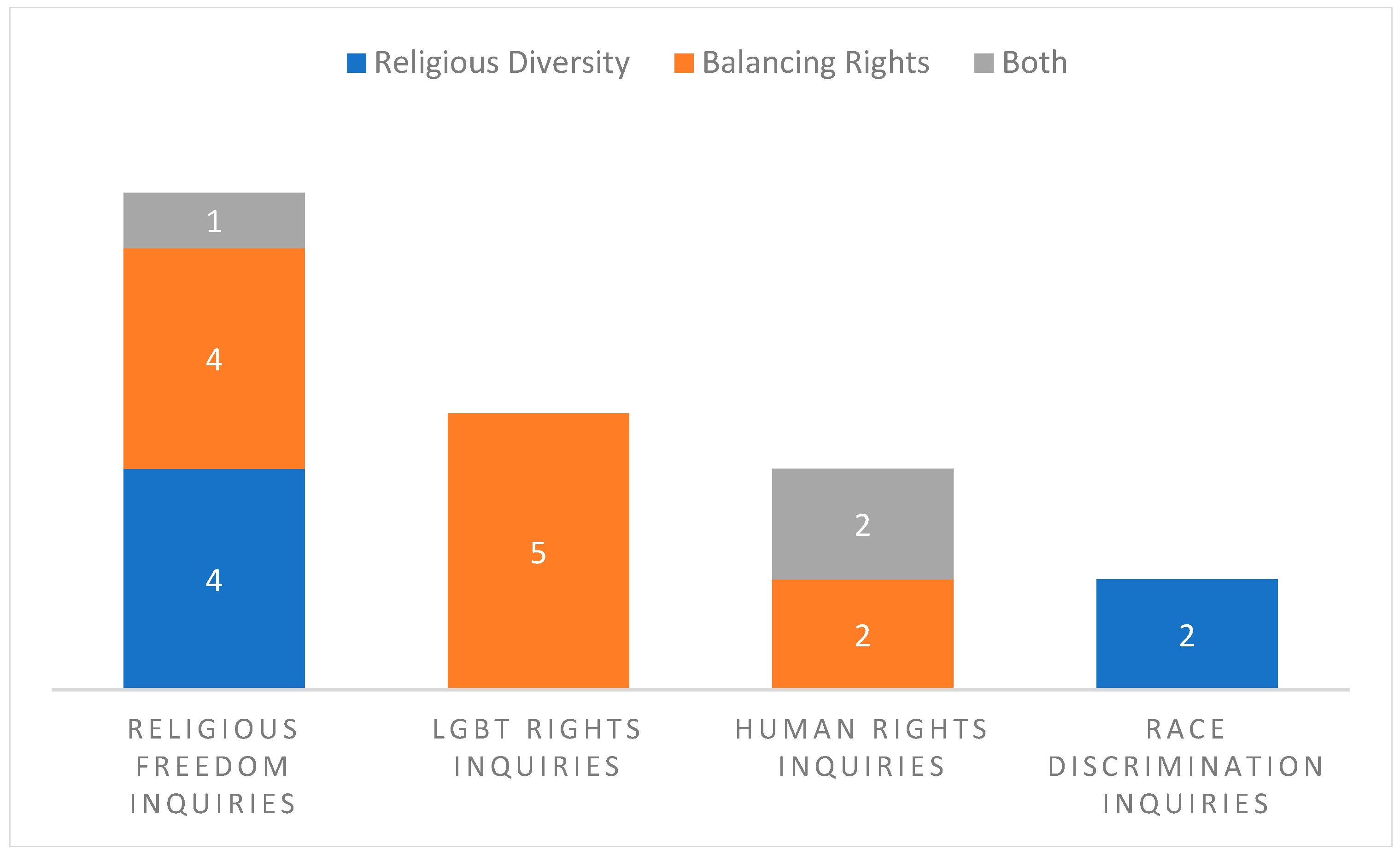

4.3. The Other Eleven Inquiries

5. Discussion

The majority of reports examined for this study entrench a way of thinking and talking about religious freedom, and even the nature of religion itself, in policy and public discourse. Applying the WPR methodology to the texts exposes an understanding of religion (individualised, privatised, institutionalised, a set of (otherworldly) beliefs expressed in rituals and codes of behaviour) that is assumed rather than articulated.is a product of how we think far more than it is a product of something enduring in the nature of poverty… It is this insight… that the “WPR” approach, with its wider poststructuralist premises, is concerned with. It creates a space from which it becomes possible to ask, quite simply, how have taken-for-granted “problems”—whether they are policy problems or conceptual problems such as the structure/agency debate itself—come to be taken for granted?(Bletsas 2012, p. 43, emphasis in original)

Sherwood writes that ‘belief’ became where the holy resides, separate to science, philosophy and reason—the ‘instruments of public reason’ (Sherwood 2015, p. 33). Then, framed in western democratic law and human rights discourse, paired with ‘religion’ and set alongside gender, race, ethnicity, disability, age etc., even as it retained its unique sense of intangibility and vulnerability, it became something more solid, more nonnegotiable, with ’a privileged relationship to essence’ (Sherwood 2015, p. 35):mutually defining terms that come into existence together—what we might just as well call a binary pair—the use of which makes a historically specific social world possible to imagine and move within, a world in which we can judge some actions as safe or dangerous, some items as pure or polluted, some knowledge as private or public, and some people as friend or foe.

It is in light of these circumstances that the law, Sherwood argues, allows religious believers ‘to be in conflict with the rights of others’ (Sherwood 2015, p. 41) and in particular, because the movement for LGBTIQ rights is the youngest liberation movement, theAs a term of nonnegotiation (unlike an “opinion”), the obvious correlate for age, pregnancy, or sexuality in the realm of ideas is belief. Exceptionally and anomalously, religious belief is defined as a mode of thinking that is not, in a sense, chosen. It insists that it must be understood as defining or exceeding the individual… Believing is understood as a form of agency that, paradoxically, takes us beyond decision to the point where it becomes that from which I cannot dissociate myself, that which cannot be wrenched apart from me except by violence—and hence a given, like sexuality or race ….

conflict between religion and sexuality (and particularly homosexuality) has become an incendiary cultural flashpoint and a stage for the trial of competing freedoms because religious belief and (homo)sexuality are more insecure and vulnerable than age, maternity, disability, or race.(Sherwood 2015, p. 41, emphasis in original)

Although the campaign for LGBT rights is ongoing… its achievements to date have affected the relationship between the government and those who adhere to certain traditional theologies on questions of sexuality. Expansion of equality law has contributed to a sense among some religious traditionalists that there has been an inversion. They feel they are now the minorities who require protection from an overwhelming liberal orthodoxy.

6. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anglican Church of Australia Diocese of Sydney. 1984. Response of the Standing Committee of the Synod of the Anglican Church of Australia, Diocese of Sydney to “Discrimination and Religious Conviction” A Report by the New South Wales Anti-Discrimination Board, 1984. Sydney: Anglican Church of Australia Diocese of Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Arnal, William E., and Russell T. McCutcheon. 2013. They Licked the Platter Clean: On the Codependency of the Religious and the Secular. In The Sacred Is Profane: The Political Nature of ‘Religion. Edited by William E. Arnal and Russell T. McCutcheon. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 114–33. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Human Rights Commission. 2015a. Religious Freedom Roundtable—Issues Paper; Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

- Australian Human Rights Commission. 2015b. Religious Freedom Roundtable—Statement of Purpose and Guiding Principles; Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

- Australian Human Rights Commission. 2015c. Religious Freedom Roundtable Summary; Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

- Australian Law Reform Commission. 2015. Traditional Rights and Freedoms—Encroachments by Commonwealth Laws; Sydney: Australian Law Reform Commission.

- Babie, Paul, Joshua Neoh, James Krumrey-Quinn, and Chong Tsang. 2015. Religion and Law in Australia. Alphen: Kluwer Law International. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, Carol. 2009. Analysing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to Be? Frenchs Forest: Pearson Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, Carol. 2012a. Introducing the ‘What’s the Problem Represented to be?’ approach. In Engaging with Carol Bacchi: Strategic Interventions and Exchanges. Edited by Angelique Bletsas and Chris Beasley. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide Press, pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, Carol. 2012b. Why Study Problematizations? Making Politics Visible. Open Journal of Political Science 2: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchi, Carol. 2018. Drug Problematizations: Deploying a Poststructual Analytic Strategy. Contemporary Drug Problems 45: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchi, Carol, and Joan Eveline. 2010. Approaches to Gender Mainstreaming: What’s the Problem Represented To Be? In Mainstreaming Politics: Gendering Practices and Feminist Theory. Edited by Carol Bacchi and Joan Eveline. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide Press, pp. 111–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, Carol, and Susan Goodwin. 2016. Poststructural Policy Analysis: A Guide to Practice. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, Charlotte. 2015. A Delicate Balance: Religious Autonomy Rights and Rights in Australia. Religion & Human Rights 10: 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Rachel. 2013. Human rights and religion in Australia: False battle lines and missed opportunities. Australian Journal of Human Rights 19: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Gary. 2014. Making Public Policy in the Public Interest—The Role of Public Inquiries. In Royal Commissions and Public Inquiries: Practice and Potential. Edited by Scott Prasser and Helen Tracey. Ballarat and Victoria: Connor Court Publishing, pp. 112–32. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, Renae. 2019. State and Religion: The Australian Story. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Luke. 2018. Religious Freedom and the Australian Constitution. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bletsas, Angelique. 2012. Spaces Between: Elaborating the Theoretical Underpinnings of the ‘WPR’ Approach and its Significance for Contemporary Scholarship. In Engaging with Carol Bacchi: Strategic Interventions and Exchanges. Edited by Angelique Bletsas and Chris Beasley. Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press, pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma, Gary D. 2012. Beyond Reasonable Accommodation: The Case of Australia. In Reasonable Accommodation: Managing Religious Diversity. Edited by Lori G. Beaman. Vancouver and Toronto: UBC Press, pp. 139–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma, Gary, Desmond Cahill, Hass Dellal, and Athalia Zwartz. 2011. Freedom of Religion and Belief in 21st Century Australia; Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

- Brennan, Frank, Mary Kostakidis, Mick Palmer, and Tammy Williams. 2009. National Human Rights Consultation Report; Canberra: Attorney-General’s Department.

- Dunn, Kevin, and Jacqueline Nelson. 2011. Freedom of Religion and Belief in the 21st Century: Meta-Analysis of Submissions; Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

- Evans, Carolyn. 2012. Legal Protection of Religious Freedom in Australia. Annandale: Federation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, Timothy. 2011. Religion and Politics in International Relations: The Modern Myth. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, Susan. 2012. Women, Policy and Politics: Recasting Policy Studies. In Engaging with Carol Bacchi: Strategic Interventions and Exchanges. Edited by Angelique Bletsas and Chris Beasley. Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press, pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Grattan, Michelle. 2017. Protecting Religious Freedoms is a Matter of Balance, Says Head of Turnbull’s Inquiry. The Conversation. November 22. Available online: https://theconversation.com/protecting-religious-freedoms-is-a-matter-of-balance-says-head-of-turnbulls-inquiry-87933 (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Hosen, Nadirsyah, and Richard Mohr, eds. 2011. Law and Religion in Public Life: The Contemporary Debate. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. 1998. Article 18: Freedom of Religion and Belief; Sydney: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

- Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. 2008. Combating the Defamation of Religions: A Report of the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights; Sydney: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

- Hutchins, Gareth. 2017. Philip Ruddock to Examine if Australian Law Protects Religious Freedom. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/nov/22/philip-ruddock-to-examine-if-australian-law-protects-religious-freedom (accessed on 19 June 2019).

- Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs Defence and Trade. 2000. Conviction with Compassion: A Report on Freedom of Religion and Belief; Canberra: Parliament of Australia.

- Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs Defence and Trade. 2017. Interim Report: Legal Foundations of Religious Freedom in Australia; Canberra: Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia.

- Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs Defence and Trade. 2019. Second Interim Report: Freedom of Religion and Belief, the Australian Experience; Canberra: Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia.

- Koziol, Michael. 2018. Ruddock Review Rejects Religious Groups’ Fears about Same-Sex Marriage. The Sydney Morning Herald. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/ruddock-review-rejects-religious-groups-fears-about-same-sex-marriage-20181010-p508re.html (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Maddox, Marion. 2014. Right-wing Christian Intervention in a Naive Polity: The Australian Christian Lobby. Political Theology 15: 132–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marier, Patrik. 2017. Public inquiries. In Routledge Handbook of Comparative Policy Analysis. Abington: Routledge, pp. 169–80. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, Ian, and Darren Halpin. 2015. Parliamentary Committees and Inquiries. In Policy Analysis in Australia. Edited by Brian Head and Kate Crowley. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Jaqueline K., Alphia Possamai-Inesedy, and Kevin M. Dunn. 2012. Reinforcing substantive religious inequality: A critical analysis of submissions to the review of freedom of religion and belief in Australia inquiry. Australian Journal of Social Issues (Australian Council of Social Service) 47: 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New South Wales Anti-Discrimination Board. 1984. Discrimination and Religious Conviction; Sydney: New South Wales Anti-Discrimination Board.

- Parkinson, Patrick. 2007. Religious Vilification, Anti-discrimination Laws and Religious Minorities in Australia: The freedom to be different. Australian Law Journal 81: 954–66. [Google Scholar]

- Poulos, Elenie. 2018. Protecting Freedom/Protecting Privilege: Church Responses to Anti-Discrimination Law Reform in Australia. Australian Journal of Human Rights 24: 117–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddock, Philip, Nicholas Aroney, Annabelle Bennett, Frank Brennan, and Rosalind Croucher. 2018. Religious Freedom Review: Report of the Expert Panel; Canberra: Australian Government—Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee. 2013. Report of the Inquiry into the Exposure Draft of the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Bill 2012; Canberra: The Senate, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee. 2018. Legislative Exemptions That Allow Faith-Based Educational Institutions to Discriminate against Students, Teachers and Staff; Canberra: The Senate, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs. 2008. Effectiveness of the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 in Eliminating Discrimination and Promoting Gender Equality; Canberra: The Senate, Commonwealth of Australia.

- Sherwood, Yvonne. 2015. On the Freedom of the Concepts of Religion and Belief. In The Politics of Religious Freedom. Edited by Winnifred Fallers Sullivan, Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, Saba Mahmood and Peter G. Danchin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 1998. Religion, Religions, Religious. In Critical Terms for Religious Studies. Edited by Mark C. Taylor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tebbe, Nelson. 2017. Religious Freedom in an Egalitarian Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | At the time of writing, the Australian Government was drafting a religious discrimination bill. |

| 2 | SDA s 37 and s 38 and ADA s 35. |

| 3 | NSW prohibits discrimination on the basis of ‘ethno-religious origin’ and SA prohibits discrimination on the basis of religious dress or appearance. |

| 4 | See for example this commentary by Prof. Andrew Jakubowicz, http://www.multiculturalaustralia.edu.au/library/media/Timeline-Commentary/id/115.The-Blainey-debate-on-immigration-. |

| 5 | The proportion of Australians identifying as Christian dropped from 88 percent in 1966 to 52 percent in 2016; ‘no religion’ increased from 19 percent in 2006 to 30 percent in 2016; other religions grew from 0.7 to 8.2 percent between 1966 and 2016 (https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Religion%20Data%20Summary~70, accessed 16 August 2019). |

| 6 | Statutory bodies such as the Australian Human Rights Commission and the Australian Law Reform Commission receive referrals from government and also have the authority to undertake public inquiries on matters relevant to their mandates without government referral. |

| 7 | HREOC/AHRC is a Commonwealth statutory body established in 1986 as Australia’s national human rights institution. |

| 8 | The Committee released two interim reports (2017 and 2019, counted as one for this study) but did not complete its work before a general election was called for May 2019, and recommended that the inquiry be continued by the next parliament (Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs Defence and Trade 2019). |

| 9 | |

| 10 | The 2018 School Exemptions report acknowledged the lack of positive protection for religious freedom but did not frame its report around this problem. |

| 11 | In the case of the 2017–2019 JSCFADT inquiry, this forms the entire First Interim Report (Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs Defence and Trade 2017). |

| 12 | The other reason for the review was the government declaring in 1993 that the UN Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief ‘a “relevant international instrument” for the purposes of the HREOC Act’ (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission 1998, p. 3). |

| 13 | CDR contains a single reference to balancing the rights of free speech and freedom from racial vilification in its description of the Race Discrimination Act: ‘The RDA, nevertheless, recognises that there is a need to balance rights and values, between the right to communicate freely (‘freedom of speech’) and the right to live free from racial vilification’ (Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission 2008, p. 13). |

| 14 | Maddox notes that by 2012, ACL Managing Director, Jim Wallace, had been ranked by The Power Index website ‘as Australia’s third-most influential religious voice on public policy, after Catholic Cardinal George Pell and Sydney’s Anglican Archbishop Peter Jensen’ (Maddox 2014, p. 133). |

| 15 | |

| 16 | The inquiry conducted 24 consultations (focus groups) with religious leaders and representatives from various atheist, secularist and rational humanist groups. The ACL organised some of the these consultations (Bouma et al. 2011, p. 9). |

| Date | Author | Report |

|---|---|---|

| 1984 | NSW Anti-Discrimination Board | Discrimination and Religious Conviction (DRC) |

| 1998 | Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) | Article 18: Freedom of Religion and Belief (Article 18) |

| 2000 | Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade (JSCFADT) | Conviction with Compassion: A report on freedom of religion and belief (CWC) |

| 2008 | HREOC | Combating the Defamations of Religions (CDR) |

| 2011 | Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC, formerly HREOC) | Freedom of Religion and Belief in 21st Century Australia (FRB21) |

| 2015 | AHRC | ‘Religious Freedom Roundtable’ (RFR) |

| 2017–2019 | JSCFADT | Status of the Freedom of Religion or Belief (1st & 2nd Interim reports) (SFRB) |

| 2018 | Expert Panel (Philip Ruddock, Chair) | Religious Freedom Review (Ruddock Review) |

| 2018 | Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee (SLCARC) | ‘Legislative exemptions that allow faith-based educational institutions to discriminate against students, teachers and staff’ (School Exemptions) |

| Other inquiries that included consideration of freedom of religion or belief | ||

| 2003 | HREOC | Isma—Listen: National Consultations on Eliminating Prejudice against Arabs and Muslim Australians |

| 2008 | Senate Standing Committee on Legal & Constitutional Affairs (SSCLCA) | ‘Effectiveness of the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 in eliminating discrimination and promoting gender equality’ |

| 2009 | National Human Rights Consultation Committee (Frank Brennan, Chair) | National Human Rights Consultation Report |

| 2011 | AHRC | Addressing Sexual Orientation & Sex and/or Gender Identity Discrimination |

| 2013 | Senate Legal & Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee (SLCALC) | ‘Report of the inquiry into the exposure draft of the Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Bill 2012′ |

| 2013 | SLCALC | ‘Report on the inquiry into the Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Bill 2013′ |

| 2015 | AHRC | Rights and Responsibilities Consultation Report |

| 2015 | AHRC | Resilient Individuals: Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Rights |

| 2015 | AHRC | Freedom from Discrimination: Report on the 40th Anniversary of the Racial Discrimination Act (2016). |

| 2015 | Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) | Traditional Rights and Freedoms—Encroachment by Commonwealth Laws |

| 2017 | Senate Select Committee on the Exposure Draft of the Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill | ‘Report on the Commonwealth Government’s Exposure Draft of the Marriage Amendment (Same-Sex Marriage) Bill’ |

| Religious Freedom Reviews | Religious Diversity | Balancing Rights | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | Discrimination and Religious Conviction | ✓ | |

| 1988 | Article 18: Freedom of Religion and Belief | ✓ | |

| 2000 | Conviction with Compassion | ✓ | |

| 2008 | Combating the Defamation of Religions | ✓ | |

| 2011 | Freedom of Religion & Belief in 21st Century Australia | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2015 | ‘Religious Freedom Roundtable’ | ✓ | |

| 2017–2019 | Status of the Freedom of Religion or Belief | ✓ | |

| 2018 | Religious Freedom Review | ✓ | |

| 2018 | School Exemptions | ✓ | |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poulos, E. Constructing the Problem of Religious Freedom: An Analysis of Australian Government Inquiries into Religious Freedom. Religions 2019, 10, 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100583

Poulos E. Constructing the Problem of Religious Freedom: An Analysis of Australian Government Inquiries into Religious Freedom. Religions. 2019; 10(10):583. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100583

Chicago/Turabian StylePoulos, Elenie. 2019. "Constructing the Problem of Religious Freedom: An Analysis of Australian Government Inquiries into Religious Freedom" Religions 10, no. 10: 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100583

APA StylePoulos, E. (2019). Constructing the Problem of Religious Freedom: An Analysis of Australian Government Inquiries into Religious Freedom. Religions, 10(10), 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10100583