Abstract

According to Islamic religious teachings, some Jews confirmed the authenticity of Muhammad’s prophethood and joined him. Most Jews, however, are condemned for both rejecting the Prophet and failing to live up to their own religious imperatives. Medieval polemics tended to be harsh and belligerent, but while Muslims and Christians produced polemics under the protection and encouragement of their own religious and political authorities, Jews lived everywhere as minority communities and therefore lacked such protection. In order to maintain their own sense of dignity Jews polemicized as well, but they had to be subtle in argument. One form of polemic produced by Jews and other subalterns is “counter-history,” which retells well-known narratives in a manner that questions or undermines their message. One such counter-history is an ancient Jewish re-telling of the traditional Muslim narrative of divine revelation.

Keywords:

Qur’an; Islam; Judaism; revelation; counter-history; Muhammad; polemics; Judeo-Arabic; metanarrative; Medina 1. Introduction

This article treats a Jewish polemical retelling of the foundational Muslim narrative of divine revelation and reception of God’s word via the prophet Muhammad. It functions as a “counter-history,” probably originating as an oral story but eventually recorded in a number of variants. The purpose of the retelling seems to have been to counter Muslim claims that the Qur’an and Islam have abrogated or superseded the authority of Jewish scripture and practice.

Islamic sources teach that Prophet Muhammad began receiving divine revelations when he was about forty years old. One day, while meditating quietly in a cave at Jabal al-Nūr (“Mountain of Light”) just outside of Mecca, he received his first revelation.1 The angel Gabriel unexpectedly appeared and commanded that he recite to the people in the name of God:

| iqra’ bismirabbikalladhi khalaq | Recite! [or call out!] in the name of your Lord who created |

| khalaqal-insān min `alaq | created humankind from a clinging mass |

| iqra’ warabbukal-akram | Recite! your Lord is most generous |

| alladhi `allama bil-qalam | who taught by the pen |

| `allamal-insān malam ya`lam2 | taught what humankind does not know |

According to Islamic tradition, this awesome moment marked the beginning of a prophetic life for Muhammad that would last from that day until the day of his death some twenty-three years later. The tradition likens him to the classic biblical prophets before him and portrays him as initially an unwilling messenger of God, but in due course he shouldered his responsibility to serve God and humanity by being a conduit for the divine message of what in modern Jewish terms could be likened to “ethical monotheism.”3 The Qur’an and Islamic tradition convey repeatedly that Muhammad had nothing to do with the composition of the Qur’an. He was simply a messenger who conveyed God’s message—not his own.4

Together, these sources convey a basic and collective Islamic narrative (or metanarrative) of its own beginnings, a sacred or “salvation history” (Heilsgeschichte) that serves as a core doctrine and foundation upon which is constructed the authority and significance of Islamic scripture, law and theology.5 The actual history of Muhammad’s life and the emergence of the Qur’an, however, remain controversial and uncertain. As with the early history of Israel and the early history of Christianity, the only written sources were composed by religious followers of the founders, which no trained historian would take at face value.6 And certainly in the case of early Islam, archaeological and paleographical research remain in their infancy.7 Any reasonable historical reconstruction of the emergence of Islam can therefore only be conjectured. The critical scholarship cited in the previous footnotes has demonstrated how difficult (or perhaps impossible) it is to reconstruct actual historical events from the canonical sources.8 It is not my purpose here to try to reconstruct the actual history or to argue in favor of either a positivist or revisionist position over the historicity of the sources. It is enough for my purpose of examining polemical literature to establish the basic Muslim narrative and observe how Jews have responded to it with their own counter-narrative.

Just as Muhammad was depicted in the sources as having fit the classical model of a reluctant prophet, so did the general opposition to his prophetic message seem to fit a historical pattern of resistance to God’s prophetic voice. The “official” biography of Muhammad mentions on the one hand that people began to accept Islam in large numbers when he began preaching in Mecca (dakhala al-nās fī al-Islām … ḥattā fashā dhikr al-Islām bimakka),9 yet the same work notes how he was challenged as soon as he began preaching against the native polytheism in Mecca, and that his actual followers were quite few.10 According to the Islamic narrative, his first opponents were the native inhabitants of his Meccan hometown who practiced indigenous, polytheistic Arabian religion. These adversaries, who derived mostly from his own tribe of Quraysh, are referred to as mushrikūn in the Qur’an—“idolaters.”11 He was also soon challenged by some who joined his community but then began to undermine him—the qur’anic munāfiqūn, usually translated as “hypocrites,” but also “doubters” or “waverers.”12 And Jews and Christians, known as ahlu-lkitāb in the Qur’an (“people of the Book”), challenged him because his status as a new prophet bringing a new divine dispensation threatened their practice and belief.13 Eventually, however, Muhammad was to prevail with the help of God, so that by the time of his death at the age of sixty-two, most of Arabia had accepted him.

Prophets challenge the religious status quo because, as spokespersons of God, they always represent a higher power than that of any human religious establishment. The prophetic role includes challenging assumptions and testing the viability of the existing state of affairs.14 History has shown how Judaism, Christianity and Islam have all revolutionized the status quo ante when they emerged into history with a new prophetic figure and divine dispensation. And history has also shown how all three scriptural monotheisms found themselves threatened by new prophets who emerged after they had become established religion. All three failed to convince the others that their understanding of God’s expectations is true. Each religious community established a series of narratives to support its own exclusive view of divine and human history, and each of those narratives undermines the claims of the others. This relationship of contention produced what is commonly referred to as polemics—perspectives, attitudes and positions that attempt to support a position by undermining and delegitimizing the position of the other.15 Polemics reflect metanarratives—patterns and structures of thinking that reflect worldviews and provide collective meaning. The story that will be examined below represents a Jewish polemical “counter-narrative” to the Islamic narrative that includes within it polemics directed against Jews. In order to make sense of the Jewish response, however, we must first consider the general thrust of the Islamic narrative regarding the role of Jews in the prophetic experience of Muhammad.

2. Islamic Narrative on the Jews of Muhammad’s Time

According to the basic Islamic narrative, some Jews living in Arabia before the birth of Muhammad were expecting the arrival of a redemptive figure. One such Jew, who came to Arabia from Syria, was Ibn al-Hayyabān. According to Ibn Qaṭāda, who narrated the tradition in the name of an elder of the Jewish tribe of Banū Qurayẓa in Medina, Ibn al-Hayyabān was such a righteous man that when he prayed for rain during intense drought, it would inevitably fall. Despite his righteousness and courageous optimism, however, he was not to see the arrival of the one he was waiting for. In Ibn Qaṭāda’s narrative, “When he knew that he was about to die he said, ‘O Jews, what do you think made me leave a land of bread and wine to come to a land of hardship and hunger? When [they] said [they] could not think of why, he said that he had come to this country expecting to see the emergence of a prophet whose time was at hand …. ‘His time has come.’”16

According to Salama ibn Salāma as recorded by Ibn Ishaq, a pious Jew from the Banū ‘Abdul-Ashhal clan once “pointed with his hand toward Mecca and Yemen and said, ‘A prophet will be sent from the direction of this land.’”17 In some stories, a Jew knows the night that Muhammad will be born, tells his Arab neighbors that the baby will be a prophet and even describes the sign of prophecy on Muhammad’s back. In one version, the Jew who predicted his birth comes to see the new baby. “He observed the mole on his back and thereupon fell into a swoon. When he later regained consciousness, they said ‘Woe to you! What is wrong?’ He answered, ‘Prophethood has gone from the Israelites and scripture has left their possession.”18

When Muhammad moved from Mecca to Medina, the first person to see him and announce his arrival was a Jew. The Medinan community had invited Muhammad to move to their town and were expecting him. Some went out to the edge of town every day to wait for his arrival, but according to the story, “The Messenger of God arrived after we had gone home, and the first person to see him was one of the Jews, who had observed what we were doing and knew that we were expecting the arrival of the Messenger of God. He shouted at the top of his voice, ‘Banū Qaylah (a collective term for the people of Medina—the Aws and Khazraj clans), your luck has come!’”19

The Muslim sources teach that these pious Jews anticipated the arrival of a prophet like Muhammad, and that some Jews recognized him as the awaited one. According to Muslim tradition, some Jews in Medina accepted Muhammad’s prophethood and immediately joined his community of followers. One was Mukhayriq, described as a learned Jew who recognized Muhammad from his knowledge of Jewish tradition. Mukhayriq was so convinced of Muhammad’s prophethood that he went out to fight for him at the Battle of Uḥud which happened to have occurred on the Sabbath when fighting is normally forbidden according to Jewish law. Mukhayriq’s last words to his fellow Jews was “If I am killed today my property is to go to Muhammad to use as God shows him.” He was killed in the battle, and his property was then distributed by Muhammad in Medina in the form of alms.20

The most famous example of a Medinan Jew joining Muhammad is that of Abdullah ibn Salām, depicted as a wise rabbi who is praised extensively in the literature and became the hero of many children’s books published in the Muslim world to this day.21 Abdullah ibn Salām not only recognizes Muhammad for his real status as prophet and joins him, he informs Muhammad that the rest of the Jews also recognize his true prophethood but refuse to admit it because they are a nation of liars.22

The Qur’an is understood in normative Muslim exegesis to confirm that the People of the Book naturally recognized Muhammad’s prophethood. Q.2:146 “Those whom We have given the book recognize it (or him) as they recognize their own children, but a group of them certainly conceal the truth, and they know it!” This is paraphrased by the popular commentary known Jalalayn as follows: “Those whom We have given the book recognize him, Muhammad, as they recognize their own children because of the description of him in their Scripture.23 [Abdullah] Ibn Salām said, ‘I recognized him the moment I saw him, as I would my own son. But my recognition of Muhammad was more intense’ but a group of them certainly conceal the truth, —that is, his description—and they know this that you [i.e., Muhammad] follow.”24

Despite these stories, however, it appears even from Muslim tradition that most Medinan Jews did not join the new community. According to some traditions, Jews are depicted as saying that Muhammad was not the person they were waiting for: “This is not the man.”25 Most Jews who witnessed Muhammad simply did not consider him a prophet of God, despite the stories about Abdullah ibn Salām and the few other Jews who did believe in his prophetic status. The observation that most Jews during the lifetime of Muhammad did not accept his prophethood seems to reflect historical reality. It is supported by the oft-repeated ḥadīth in which Muḥammad reportedly said, “Had [only] ten Jews (or ten rabbis) followed me, every single Jew on earth would have followed me,26 and the fact according to all the Muslim historical reconstructions of the Prophet’s period in Medina that the three major Jewish tribes of Medina all actively opposed him. The general Jewish refusal to believe in Muhammad’s prophetic status would also explain why Jews are depicted so frequently in both the Qur’an and the Ḥadith as being stubborn, and they are condemned not only for rejecting the prophet but also for failing to live up to their own religious imperatives.27 The latter accusation helps to explain away the Jews’ failure to recognize what was supposed to have been obvious.

These attributes and images directed against the Jews of Muhammad’s time are contained within a much larger landscape of Muslim polemics which are also directed against Christians, polytheists, Hindus and various Muslim movements within the Muslim world itself. And Muslim polemics fit into a larger world of polemical literatures that was particularly productive between contending Muslims and Christians. Muslim and Christian polemic was produced under the protection and encouragement of their own religious and political authorities. Jewish polemic was not.

Jews lived as minority communities under Muslim and Christian rule, which of course did not afford them such protection.28 As a result of this unusual situation, Muslims and Christians could and did write often extreme public condemnations of Jews and Judaism (as well as other groups), while Jews were restrained from writing public responses. Jews naturally responded to the arguments leveled against them and also offered their own critique of the opposing religions, but Jewish polemical material tends to be subtle, often articulated through coded language for their own protection, and rarely in compositions written as polemics per se. We will observe how this was accomplished through narrative below.

Jews, like Christians and the believers of other religions, were faced with the problem of the extraordinary historical success of Islam and the civilization that it produced. The success of Islam was observed by all parties through a shared historical lens that considered history to be driven by the divine will. All agreed, therefore, that the historical success of Islam had to be the will of God. But Jews, Christians and Muslims interpreted that success differently. For Muslims, history proved theology. Their tremendous success as a world religion and powerful empire was a result of the truth of their religion and the verity of God’s reward and support. Jews and Christians of course saw things otherwise. For many Christians, Muslim success was a sign of divine displeasure with Christian sin.29 Some Jews would agree with Christians who held that position, but they saw the sins of Christianity quite differently than did Christians. Many Jews considered the success of Islam to be divine punishment leveled against Christianity for its theological and political–military excesses, and particularly its oppression of Jews.30 Many Jews placed Islam (along with Christianity) into an apocalyptic–messianic progression of rising and falling empires that would eventually result in the coming of a Jewish messiah based on the biblical Book of Daniel.31 Some even understood Islam’s success as a fulfillment of the divine promises made to Hagar (Gen.16:11–12) and to Abraham (Gen.17:20) in relation to the birth of Ishmael, whom both Jews and Muslims agreed was the progenitor of the Arabian community that produced Muhammad. Ishmael is associated in Arab genealogies with the northern “Arabized Arabs” (al-`arab al-musta`riba or al-muta`arriba), also known as the `Adnānī or Mudarī Arabs.32 But according to Jewish interpretations of those verses, the promises were about political and military success among Ishmael’s descendants. They had nothing to do with the coming of a future prophet and the formation of a new religion.33

3. Point and Counterpoint

The most common and repeated vehicle for Muslim polemics against Jews and Judaism was via critique of Jewish scripture. Jews in the Muslim world suffered from the persistent claim that Jewish scripture had been distorted by their own ancestors,34 that it had once contained divine prophecies of the coming of Muhammad which been cynically removed by Jews but whose vestiges can still be found therein,35 and that it had been abrogated by the arrival of God’s last and greatest scripture through the prophethood of Muhammad.36 Jews responded directly to each of these claims using a variety of approaches,37 but they also made an “end run” around all Muslim critique by arguing that Muhammad and the Qur’an he brought, the most sacred and foundational sources for Muslim religious and institutional authority, are not truly what the tradition claims them to be but rather only an invented story based on falsehood and fiction. However, the status of both Muhammad and the Qur’an were topics that Jews were forbidden by law as well as custom to critique.38 The penalties for doing so could be extremely harsh, and even accusations of disrespect toward Muhammad and the Qur’an could result in severe punishment, not only for the individual accused but also for the entire community.

As a result, Jewish polemics in the Muslim world tended to be limited to oral discourse, and when written they were often expressed indirectly or written in code.39 Muhammad’s name, for example, is rarely found in Jewish writings about Islam, nor the word, “Qur’an.” And while Jews living in the Muslim world wrote mostly in Arabic, the alphabet used was usually Hebrew, which was rarely learned by Muslims. Perhaps the most popular strategy for defending Jewish integrity while attacking opponents was through the production of oral “counter-histories,”40 and one such counter-history is a series of stories dating from the early Middle Ages about how it was not God but actually Jews who wrote the Qur’an and gave it to Muhammad. In the course of their writing the Qur’an, those Jews embedded within it certain hints in order to prove that it did not come from God.

This story seems to have originated as an oral counter-narrative that retells the traditional Muslim story of Muhammad, Gabriel and the revelation of the Qur’an to an entirely different end.41 It is difficult to prove the existence let alone the pervasiveness of oral literature, but a series of stories can be found in a wide range of Jewish sources in a variety of languages and representing a broad geographic and chronological spread that tell the same basic counter-history to the standard Islamic history of the emergence of Islam. Examples of the basic narrative derive from parts of the Arabic-speaking Muslim world and from southern European areas that were in close commercial relationship with the Muslim world (Spain, Italy, Greece). The earliest to date are 10th century Hebrew and Arabic manuscripts from the Cairo Geniza, which served as a repository for thousands of Jewish writings from throughout the Mediterranean basin.42 Some versions of the story are still living oral tales conveyed in Farsi.43 The ten written versions contain aspects that reveal an oral provenance through repeated oral-style discourses and types of variation that suggest orality.

The earliest versions are embedded in larger works, and the fragments located thus far do not tell a complete story, but we know the thrust of the narrative from later, fuller renderings to which they can be compared.44 An early Hebrew fragment from the Cairo Geniza recounts that ten Jewish elders (zekēnīm) befriend Muhammad “and made for him the Qur’an.”45 Four of the elders’ names are given, and they include Abdullah ibn Salām. Recall that in the traditional Islamic narrative, Abdullah ibn Salām was the Jewish scholar who immediately joined with Muhammad and denounced his fellow Jews as liars for knowing but denying the truth of his prophethood. In this counter-history, however, Abdullah ibn Salām was not a loyal follower but rather an undercover agent who would prove that Muhammad was not a true prophet. The core of the story consists of two sentences: “They wrote and inserted their names, every single individual, and thus it is written in ḥf-gṣ of the cow: ‘Thus do the sages of Israel46 counsel the mute, wicked one’ (le’illem harasha`). All this was to save the people of God so that he would not harm them through his wanton deeds.”47

The reference to “the cow” is not merely a reference to a cow, but rather to the longest chapter of the Qur’an and typically identified by Muslims by its name, “The Cow” (sūrat al-baqara)48 This chapter is the first after a brief introduction called al-fātiḥa, which is identified as a chapter but serves as a brief introductory prayer of reverence to God that prefaces the Qur’an as a whole. The section known as “The Cow” thus serves as the first chapter of the Qur’an to provide substantial content. The second key word is ‘illēm, a Hebrew word meaning “mute” –spelled with the three Hebrew letters ‘.l.m. (א.ל.מ.) Jacob Mann noted the likely association with the word in its plural form (illmīm) in Isaiah 56:10 His watchmen are blind; they are all ignorant, they are all dumb dogs that cannot bark; watching, lying down, loving to slumber (צֹפָיו עִוְרִים כֻּלָּם לֹא יָדָעוּ כֻּלָּם כְּלָבִים אִלְּמִים לֹא יוּכְלוּ לִנְבֹּחַ הֹזִים שֹׁכְבִים אֹהֲבֵי לָנוּם).49 There is more to this citation than might be obvious. It is referring to blind watchmen (ṣofav `ivrīm) and dogs watching (kelavīm hozīm). Both the roots for watchmen (ṣ.f.h.) and watching (h.z.h.) are used metaphorically to refer to prophets in the biblical verse.50 Associating a word with a scriptural passage is a common technique of interpretation in Jewish tradition,51 and the association of Muhammad with ignorant and blind prophets in Isaiah 56:10 suggests that he could not be a real prophet. This might appear to be a random association, but the Hebrew word ‘illem (אלם) is made up of the same three Hebrew letters that in Arabic script preface the second chapter of the Qur’an named “The Cow.” These are alif lām mīm (ا ل م), which make up one of a series of enigmatic letter combinations prefacing twenty-nine chapters of the Qur’an. The prefatory letters of certain qur’anic chapters spell no real words and their function remains unknown.52 They are often called in Islamic parlance “disjointed letters” (ḥurūf muqaṭṭa`āt) because they appear in their detached (unconnected) orthographic form, and no consensus has been reached by either traditional Muslim or secular academic scholars regarding their meaning or purpose. It could easily be tempting for Jewish polemicists to maintain that these Arabic letters actually have a hidden purpose by spelling the Hebrew word illēm, thus indicating that everything that follows—virtually the entire Qur’an—is simply the product of a mute, ignorant pseudo-prophet as in the Isaiah verse above (56:10). The story, however, does not say this directly. It only refers to “the cow,” transcribes a meaningless combination of Hebrew letters (ḥf-gṣ), and then a sentence that has no obvious resonance with the Bible or the Qur’an, “Thus do the sages of Israel counsel the mute, wicked man.”

For the text to explain the code within it would of course defeat its purpose. But the manuscript does give a tantalizing hint by citing the strange set of letters ḥf-gṣ (חף גץ). These letters are written in the ancient manuscripts with bars over them, indicating that their purpose is other than to spell out words, and in fact they do not spell any known Hebrew words.53 No one has yet satisfactorily explained ḥf-gṣ, and it is possible that the code itself is a literary product that has no actual solution but appears simply as a hint (Heb: remez) that the Qur’an should be read in a way that indicates its profane status. In the ancient Hebrew fragment, the brief segment ends with an actual explanation for the entire subterfuge: “All this was to save the people of God so that he would not harm them through his wanton deeds.” “He” in this sentence refers to Muhammad, who as noted above is rarely mentioned by name.

The manuscript itself acknowledges the morally condemnable acts engaged by the ten Jewish elders of disguising their identity and pretending they are loyal followers of Muhammad while actually undermining and misleading him into believing he was receiving revelation when they were actually writing the Qur’an themselves—and disparaging it by encoding offensive remarks within it. But it also explains that their actions were carried out only in order to protect a people endangered by the reckless behavior of a man new to power. This is the message that is articulated one way or another in all the various versions of the story. It is quite interesting to note how they all acknowledge that normally inexcusable behavior according to Jewish law and ethics was necessary in order to ensure community survival under what the sages knew from their esoteric knowledge would be the harsh rule of Islam.

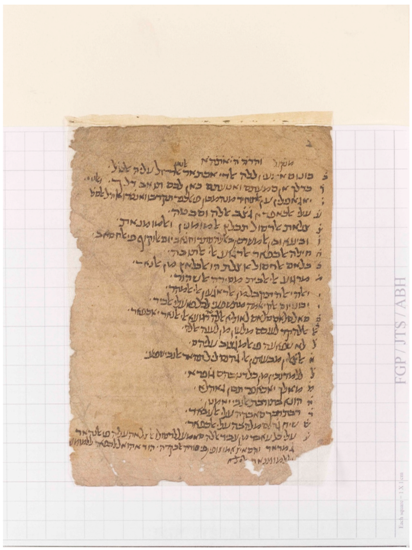

An Arabic version of the same story can also be found among the fragments of the Cairo Geniza. Jacob Leveen, who first published it in 1925–1926,54 dates the manuscript to the twelfth century. Moshe Gil, on the other hand, considered the Arabic version to predate the Hebrew version just examined and dates it to the early tenth century based on the appearance of the name of the Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir (908–932) in a second copy he identified some eighty years after the publication of the first manuscript of the Arabic story.55 Leveen’s Arabic version is composed of two parts, the second of which is missing from both Gil’s manuscript and the Hebrew rendering. The first part is clearly a version of the Hebrew fragment just considered, but written in Judeo–Arabic.56 But Leveen’s identical Arabic version includes a second part on the verso side of the page which purports to provide the actual verses that the Jewish companions wrote into the Qur’an in the form of an acrostic constructed out of the letters forming the Hebrew sentence, “Thus do the sages of Israel counsel the mute, wicked one.”57 This same sentence is found in the Hebrew version purportedly written into the qur’anic chapter called “The Cow,” but in the Hebrew version it does not make up an acrostic message.

Like the Hebrew version, the Arabic story is embedded in a larger work, but it has a title: “The Story of the Companions of Muhammad: Appendix to the Book of History” (qiṣṣat aṣḥāb Muḥammad ilḥāq ila kitāb al-ta’rīkh). “… the Jewish sages came and appeared before him and told him what had occurred to him and concocted a book for him. They devised and wrote their names in the first sūra of his Qur’an. They devised and wrote: ‘Thus do the sages of Israel counsel the mute, wicked one’ secretly and obscurely so that it would not be understood. And cursed by the mouth of God—as those sages said—is anyone who makes this known to any non-Jew.”

In this version of the story, the names of all ten Jews who joined Muhammad are listed, followed by “These are the ten who came to him and Islamized at his hand so that nothing would harm Israel. They made for him a Qur’an and wrote and inserted their names, each one in a chapter without cause for suspicion. They wrote in the middle chapter ‘Thus do the sages of Israel counsel the mute, wicked one.’58 In the name of God, the Exalted, the Powerful, the Mighty, the Great, the Victorious, the Forgiving, the Master, the Creator, to whom everything belongs.”

Similar to the Hebrew version, the Arabic notes that the Jews who tricked Muhammad did it “so that nothing would harm Israel.” A curse appears in the Arabic version as well, upon anyone who would reveal the secret of the Jews’ act of composing the Qur’an. This curse had the effect of making the claim of Jewish authorship of the Qur’an much more credible. That is, it raises the stakes by announcing that the truth is so important and dangerous that it merits a divine curse upon anyone who would dare to let the truth be known to the outside world. The curse has a second purpose as well, that being to keep the critique of the Qur’an and the prophet who brought it away from the eyes of Muslims who would obviously be outraged at the claim and would likely respond harshly.

The Arabic version also explains the enigmatic line in the Hebrew version, “Thus do the sages of Israel counsel the mute, wicked man.” According to the Arabic version, this sentence is a secret message that is revealed when the acrostic message is deciphered in the series of Qur’an verses presumably found in the Qur’an chapter called “The Cow.” When the first letters of each of the Arabic verses are joined together in the order of the verses, they spell כך יעצו חכמי יסראל לאלם הרשע (“Thus do the sages of Israel counsel the mute, wicked man”). Two simple problems with the acrostic are immediately noticeable. The first is that yisra’el (Israel) is spelled with a different sibilant “s” sound than in the biblical spelling. The second is that there is no verse attached to the letter ר (“r”).

To make it clear exactly how the acrostic message was intended to be read I reproduce the Arabic verses here with the letters of the acrostic marked in red.59

| And these are the forms of the verses transcribed | והדֹה הˈיˈאˈתˈהˈא |

| מנקול | |

| ˈכ Be obedient to God who has chosen the prophet, the apostle, upon whom be peace. | ·כֹ כונו סא[מ]עין ללה אלדי אכתאר אלנבי61 אלר[ס]ול עליה אלסלˈ |

| ˈך Such, if you listen and obey, will be your reward. | ךֹ כדלך אן סמעתם ואטעתם כאן לכם תואב דלך· ואלעי |

| ˈי O you who flee from the unity of God, engrossed with heresy, draw near and observe the people of peace. | ·יֹ יא גאפלין ען אלתוחיד מנהמכון פי אלכפר תקרבו ואנטֹרו אהל אלסלˈ |

| ˈע Upon the unbelievers is the wrath of God and His displeasure. | .עֹ עלי אלכאפרין נֹצֹב אללה וסכטא |

| ˈצ Prayer of the apostle purifies the believing men and women. | ·צֹ צלאת אלרסול תכלץ אלמומנין ואלמומנאת |

| ˈו And between us and those who join other [deities] with God is a veil and a curtain on the day of standing up for reckoning. | ·וֹ וביננא ובין אלמשרכין באללה סתר וחגאב יום אל וקוף פי אלחסאב |

| ˈח Turning from false worship by the unbelievers is return to repentance. | ·חֹ חילה אלכפאר אלרגֹוע אלי אלתובה |

| ˈכ Speech of the Apostle or prayer is deliverance from the Fire. | ·כֹ כלאם אלרסול או צלת הו אלכלאץ מן אלנאר |

| ˈמ Return to the House is the journey to the manifest. | ·מֹ מרגע אלי אלבית מסירה אלשהוד |

| ˈי O God! O God! Receive those returning to beginnings. | ·י יאלה יאלה תקבל מן אלראגֹעין אלי אלמהד |

| ˈי The Day of Resurrection will be intercessor for all who do good. | ·י יכונו יום אלקיאמה מתשפעי לכל פאעלי אלכיר |

| ˈס Pray for peace for those close to God; return to the Fire O unbelievers! | ·סֹ62 סאל סלאם סלאם לאוליא אללהשר’63 רגועא אלי אלנאר יא כפאר |

| ר’64 | ר’64 |

| ˈאל God has already cursed you. Cursed is he who curses God! | ·אלֹ אללה קד לענכם מלעון מן לענה אללה |

| ˈל There is no intercession for those with whom [God] is angry.60 | ·לֹ לא שפאעה פי אלמגֹדוב עליהם |

| ˈא The errant are sent to Hell; but for purification, the Prophet is intercessor. | ·אֹ אלצֹאלין מבעותין אלי גהנם לילתהאר אלנבי שפיע |

| ˈל To the guilty is forgiveness for all their sins. | ·לֹ ללמדנבין מן כל דנובהם גֹופרא |

| ˈם What is with you, O unbeliever, [that] you are [so] ignorant! | ·םֹ מא לק יא כאפר תכון גאהלא |

| ˈה They easily believe in the dust of the Prophet. | ·הֹ הונא בתורבת אלנבי יאמנון |

| ˈר Those allied with God surpass slaves! | ·רֹ רבת רבך סאבקה עלי אלעבאד |

| ˈש Wormwood of Hell flames over the unbelievers. | ·שֹ שיח גֹהנם מלהבה עלי אלכפאר |

| ˈע It is the duty for all worshippers among the worshippers of God to hearken to the Apostle and pray for him three times a day; | עֹ עלי כל עאבד מן עביד אללה סאמע ללרסולו אלצלאה עליה פי אלנהאר ג’ מראר |

| They are depicted in the sūra The Cow Forbearance of teaching for the unbelievers, the believing men and women… | והם איצֹא מוצופין פי סורה אלבקרה· הוד אקואל ללכפאר ללמומנין ולמומנאת []65 |

This facsimile of the verso of the original Arabic document was graciously provided by the Jewish Theological Seminary and catalogued as ENA 2541.1 Verso. JTS. Friedberg Jewish Ms. Society.

The message of the secret acrostic embedded in the Arabic verses seems clear: this Qur’an is not truly the word of God. The Muslims who believe in the divine origin of the Qur’an are following a religion that does not reflect God’s true will. Jews should therefore feel confident that, notwithstanding their suffering as an inferior minority under Muslim domination, they are doing right by remaining loyal to their tradition and scripture despite the scorn and derision they experience under Muslim rule.66 The Muslim attacks against the Jews, against the sanctity of Jewish scripture, and against their religious integrity are meaningless before God.

There is, however, one major problem with the story: not a single line of the twenty-one Arabic verses reproduced here is actually found in the Qur’an.

Why would such a document be created?

It is of course impossible to provide a definitive answer to the question. The acrostic page is a thousand years old, and because we do not have the full text out of which it forms a part we know little to nothing of its context in the larger work. And of course, we do not know the author. The story represents one version of a narrative that seems to have evolved orally for centuries, and we have a number of other versions that do not include the acrostic.67 All the versions are based on the identical theme of Jews infiltrating the entourage of Muhammad early on in his career and writing all or part of the Qur’an, thereby “proving” that the Qur’an is not a divinely authored scripture. One could surmise that such a story would discourage Jewish listeners/readers from considering the possibility of leaving the Jewish community and discarding their scorned second-class minority status by becoming Muslim.

The story sheds light on the situation that Jews, Muslims and Christians found themselves in when confronted with clashing “zero-sum” claims regarding the meaning of God, revelation and truth. One of the most powerful lessons people have tended to assume from the nature of monotheism is that because one single God is the creator of all heavens and earths, there must be one absolute truth that derives from the deity.68 If God is the creator of all, then God must be all-powerful and all-knowing. Monotheists also generally assume that God created the world in goodness, so that God must be all-good. If God is all these things, then it would seem only reasonable that God would not reveal new messages to humankind unless those who had received previous messages had somehow failed to live up to the previous divine imperative. The heavens do not open up to reveal a new divine dispensation unless there is a great and pressing need to do so.

While a number of these assumptions about monotheism can be challenged, the perspective presently articulated represents the general view of the three traditional scriptural monotheisms toward competing truth claims, and it reflects a pattern of religious relationship that can be observed even today with the emergence of new monotheist religious movements. From the perspective of these new religions, the old religions are failing to live up to the divine will and need to be discarded for the new. But from the perspective of established religions, the founders of new religions are false prophets who undermine the truth of God established in the sacred scriptures and traditions already existing.

The conflict between established religions and new religions is not a new phenomenon, and the polemical nature and patterns of relationship are easily observable, particularly when one is sensitized to them. What often is not taken into consideration in the dance of dispute, however, is the power aspect of the relationship. When Christianity emerged into history it was powerless. The powerful monotheist religious institution at the time of Christian emergence was the Jewish establishment in Jerusalem that opposed what it considered to be the false claims of Jesus and his followers. But by the time Christianity took over the reins of the Roman Empire in the fourth century, the power relationship had become reversed. Something similar occurred in the emergence of Islam, but it was Christianity that was the major establishment religion at that time. Jews by the time of Islamic emergence had long ago lost their political power, but as observed above, in Arabia which was outside the control and religious persecution of the Byzantine Empire, they seem to have retained a formidable aura as an ancient, well-established monotheist community with a scripture and tradition that supported their prestige. Soon after the birth of Islam, however, the Jews of the Middle East were overwhelmed by the success of the Muslim community; and similar to their experience under Christianity, Jews suffered the indignities of a derided minority depicted in the contemporary media as wrong-headed, stiff-necked, and replaced by a new community beloved of God.

Jews were unable to argue their version of truth freely and openly because of the social and religious restrictions imposed upon them. But as can be imagined, they felt the need to maintain their own sense of dignity even as a minority community under duress from the majority culture. A characteristic response of subaltern communities is to counter the dominant narrative indirectly.69 Unsurprisingly, Jews polemicized subtly through a variety of indirect methods, some of which resulted in non-Jews identifying Jews as “sneaky” or dishonest and devious, but which have since been recognized as typical of powerless communities attempting to preserve their dignity under duress. One such example is this ancient and rarely considered Jewish counter-history of Islamic origins.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adang, Camilla. 1996. Muslim Writers on Judaism and the Hebrew Bible from Ibn Rabban to Ibn Hazm. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Adang, Camilla, and Sabine Schmidtke. 2010. Polemics (Muslim-Jewish). In Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Edited by Norman Stillman. Leiden: Brill, vol. 4, pp. 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- al-Saqā, Musṭafā. n.d. Al-Sīra al-Nabawiyya libn Hishām. 2 vols. Edited by Ibrāhīm al-Ibyārī and ‘Abd al-Ḥafīẓ Shalabī. Beirut: Dār al-Thiqāfa al-‘Arabiyya.

- al-Ṭabarī, Muḥammad b. Jarīr. 1405/1984. Al-Jāmi` al-Bayān `an Ta’wīl Āy al-Qur’ān. Beirut: Dār al-Fikr. [Google Scholar]

- Assman, Jan. 2010. The Price of Monotheism. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Astren, Fred. 2010. Dhimma. In Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Edited by Norman Stillman. Leiden: Brill, vol. 2, pp. 70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Avishur, Yitzhak. 1997. Pejoratives for Gentiles and Jews in Judeo-Arabic in the Middle Ages and Their Later Usage (Hebrew). In Shai le-Hadasah: Mehkarim ba-lashon ha-‘Ivrit uvi-leshonot ha-Yehudim (Hadassah Shy Jubilee Book: Research Papers on Hebrew Linguistics and Jewish Languages). Edited by Yaakov Bentolila. Be’er-Sheva: Bialik Publishing, pp. 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Baneth, David Z. 1932. Replies and Remarks on ‘Muhammad’s Ten Jewish Companions’ (Hebrew). Tarbiz 3: 112–16. [Google Scholar]

- Beinhauer-Köhler, Bärbel, Jörg Jeremias, Rebecca Gray, Maurice-Ruben Hayoun, David Aune, Frieder Ludwig, and Uri Rubin. 2011. Prophets and Prophecy. In Religion Past & Present: Encyclopedia of Theology and Religion. Edited by Hans Dieter Betz. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shammai, Haggai. 1984. The Attitude of Some Early Kara’ites Toward Islam. In Studies in Medieval Jewish History and Literature (vol. 2). Edited by Isadore Twersky. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Biale, David. 1999. Counter-History and Jewish Polemic Against Christianity: The Sefer toldot yeshu and the Sefer zerubavel. Jewish Social Studies 6: 130–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowersock, Glen W. 2013. The Throne of Adulis. Oxford: Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Brocket, Adrian. 1993. Munāfikūn. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Edited by Peri Bearman, Thierry Bianquis, Clifford Edmund Bosworth, Emeri van Donzel and Wolfhart Heinrichs. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, Alan. 2002. The Jews of Khazaria, 2nd ed. New York: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Cahen, Claude. 1983. Dhimma. In Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Edited by B. Lewis, Ch. Pellat and J. Schacht. Leiden: Brill, vol. 2, pp. 227–31. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, David. 1991. Time, Narrative, and History. Bloomington: Indiana University. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Boaz. 1929. Une légende juive de Mahomet. Revue des études juives 88: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Mark. 1994. Under Crescent and Cross. Princeton: Princeton University. [Google Scholar]

- Crone, Patricia, and Michael Cook. 1977. Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, Stephanie. 2008. Subalterns and Social Protest: History from Below in the Middle East and North Africa. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, Norman. 2000. Islam and the West. Oxford: One World Publications. First published 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Eph’al, Yisrael. 1976. ‘Ishmael’ and ‘Arab(s)’: A Transformation of Ethnological Terms. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 35: 225–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, Reuven. 2005. A Problem with Monotheism: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam in Dialogue and Dissent. In Heirs of Abraham: The Future of Muslim, Jewish, and Christian Relations. Edited by Bradford Hinze. New York: Orbis books, pp. 20–54. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone, Reuven. 2014. The Prophet Muhammad in Pre-Modern Jewish Literatures. In The Image of the Prophet between Ideal and Ideology. Edited by Christiane Gruber and Avinoam Shalem. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone, Reuven. 2018. The ‘Other’ Ishmael in Islamic Scripture and Tradition. In The Politics of the Ancestors: Exegetical and Historical Perspectives on Genesis 12–36. Edited by Mark G. Brett and Jakob Wöhrle. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Funkenstein, Amos. 1993. Perceptions of Jewish History. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudeul, Jean-Marie, and Robert Caspar. 1980. Textes de la tradition musulmane concernant le tahrîf (falsification) des écritures. Islamochristiana 6: 61–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, Moshe. 1993. The Story of Baḥīrā and its Jewish Versions. In Hebrew and Arabic Studies in Honour of Joshua Blau. Edited by Haggai Ben-Shammai. Jerusalem: Hebrew University Press, pp. 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, Moshe. 2004. Related Worlds: Studies in Jewish and Arab Ancient and Early Medieval History. Franham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Goitein, Shelomo Dov. [1967–1973] 1993. A Mediterranean Society. 6 vols. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume, Alfred. 1955. The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Ibn Ishaq’s Sirat Rasul Allah. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, Moinul. n.d. Ibn Sa’d’s Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabir. New Delhi: Kitab Bhavan.

- Hawting, Gerald. 2002. Idolatry and Idolaters. In The Encyclopedia of the Qur’an. Edited by Jane Dammen McAuliffe. Leiden: Brill, vol. 2, pp. 475–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, Adina, and Cole Peter. 2011. Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza. New York: Schocken. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyland, Robert G. 1997. Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn `Abbās. 1992. Tanwīr al-Miqbās min Tafsīr Ibn `Abbās. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Sa’d. [1418] 1997. Al-Ṭabaqāt al-Kubrā. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Martin. 2005. Interreligious Polemics in Medieval Spain: Biblical Interpretation between Ibn Ḥazm, Shlomoh ibn Adret, and Shim’on ben Ṣemaḥ Duran. Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Thought 20: 2–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Martin. 2007. An Ex-Sabbatean’s Remorse? Sambari’s Polemics Against Islam. Jewish Quarterly Review 97: 347–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffee, Martin. 2001. One God, One Revelation, One People: On the Symbolic Structure of Elective Monotheism. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 69: 753–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juynboll, G. H. A. 1983. Muslim Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Muhammad Muhsin. 1983. The Translation of the Meanings of Sahih Al-Bukhari. Lahore: Kazi Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Landsberger, Bruno. 1936. Die babylonische Theodizee (akrostichisches Zweigespräch: sog. ‘Kohelet’). Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und verwandte Gebiete 43: 33–76. Available online: http://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/dmg/periodical/pageview/115942 (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Lassner, Jacob. 1999. S. D. Goitein: A Mediterranean Society. An Abridgement in One Vaolume. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus-Yafeh, Havah. 1992. Intertwined Worlds: Medieval Islam and Bible Criticism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lecker, Michael. 1995. Muslims, Jews and Pagans. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lecker, Michael. 2010. Glimpses of Muḥammad’s Medinan decade. In Muḥammad. Edited by Jonathan E. Brockopp. Cambridge: Cambridge University. [Google Scholar]

- Lecker, Michael. 2012. The Jewish Reaction to the Islamic Conquests. In Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe. Edited by Volkhard Kresh and Marian Steinicke. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Leveen, Jacob. 1925/1926. Mohammed and his Jewish Companions. The Jewish Quaterly Review 16: 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Bernard. 1950. An Apocalyptic Vision of Islamic History. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 13: 308–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, Jacob. 1921/1922. A Polemical Work against Karaite and Other Sectaries. The Jewish Quaterly Review 12: 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, Jacob. 1937/1938. An Early Theologico-Polemical Work. Hebrew Union College Annual 12–13: 411–59. [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein, Arthur. 1922. Die Einleitung zu David ben Marwans Religions-philosophie wiedergefunden. Monatsschrift für die Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judenthums (MGWJ) 66: 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Keith. 1996. A New investigation into the mystery letters of the Qur’an. Arabica 43: 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Keith. 2003. Mysterious Letters. Encyclopedia of the Qur’an 3: 471–76. [Google Scholar]

- Motzki, Harald. 2002. The Origins of Islamic Jurisprudence. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Motzki, Harald. 2003. The Question of the Authenticity of Muslim Traditions Reconsidered: A Review Article. In Method and Theory in the Study of Islamic Origins. Edited by Herbert Berg. Leiden: Brill, pp. 211–58. [Google Scholar]

- Newby, Gordon Darnell. 1989. The Making of the Last Prophet. Columbia: University of South Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, Gordon. 2011. Narratives of Tampering in the Earliest Commentaries on the Qur’ān. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, Adam. 1971. The Making of Homeric Verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, David S. 2007. Muḥammad is not the Father of Any of Your Men. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, Barbara. 2009. The Legend of Sergius Bahira: Eastern Christian Apologetics and Apocalyptic in Response to Islam. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, Barbara. 2014. Ibn Kammūna’s and Ibn al-‘Ibrī’s Responses to Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī’s Proofs of Muḥammad’s Prophethood. Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 2: 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Paul. 2001. Muhammad, the Jews and the Constitution of Medina: Retrieving the historical Kernel. Der Islam 86: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacht, Joseph. 1964. An Introduction to Islamic Law. Oxford: Oxford University. [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer, Peter, Yaacov Deutsch, and Michael Meerson. 2011. Toledoth Yeshu (“The Life Story of Jesus”) Revisited. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Schlossberg, Eliezer. 1990a. The Attitude of R. Saadia Gaon Toward Islam (Hebrew). Daat: A Journal of Jewish Philosophy and Kabbala 25: 21–51. [Google Scholar]

- Schlossberg, Eliezer. 1990b. The Attitude of Maimonides toward Islam (Hebrew). Pe’amim 42: 38–60. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtke, Sabine. 2011. The Muslim Reception of Biblical Materials: Ibn Qutayba and his A’lām al-Nubuwwa. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 22: 249–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeler, Gregor. 2003. Foundations for a New Biography of Muḥammad: The Production and Evaluation of the Corpus of Traditions according to ‘Urwah b. al-Zubayr. In Method and Theory in the Study of Islamic Origins. Edited by Herbert Berg. Leiden: Brill, pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker, Stephen. 2012. Muḥammad and the Qur’ān. In The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. Edited by Scott Fitzgerald Johnson. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schöller, Marco. 2002. Opposition to Muḥammad. In Encyclopedia of the Qur’an. Edited by Jane Dammen McAuliffe. Leiden: Brill, vol. 3, pp. 576–80. [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe, Moshe. 1931. Mohammed’s Ten Jewish Companions (Hebrew). Tarbiz 2: 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Shtober, Shimon. 2011. Present at the Dawn of Islam: Polemic and Reality in the Medieval Story of Muhammad’s Jewish Companions. In The Convergence of Judaism and Islam. Edited by Michael Laskier and Yaacov Lev. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, pp. 64–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sklare, David. 1999. Responses to Islamic Polemics by Jewish Mutakallimun in the Tenth Century. In The Majlis: Interreligious Encounters in Medieval Islam. Edited by Hava Lazarus-Yafeh, Mark R. Cohen, Sidney H. Griffith and Sasson Somekh. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 137–61. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman, Norman. 1979. The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman, Norman, ed. 2010. Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. 5 vols. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Leo. 1952. Persecution and the Art of Writing. Glencoe: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stroumsa, Sarah. 1985. The Signs of Prophecy: The Emergence and Early Development of a Theological Theme in Arabic Theological Literature. Harvard Theological Review 78: 101–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroumsa, Sarah. 1997. Jewish Polemics Against Islam and Christianity in the Light of the Judeo- Arabic Texts. In Judaeo-Arabic Studies: Proceedings of the Founding Conference of the Society for Judaeo-Arabic Studies. Edited by Norman Golb. Chicago: Oriental Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan, John. 2002. Saracens. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tottoli, Roberto. 2014. Hadith. In Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God. Edited by Coeli Fitzpatrick and Adam Walker. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, pp. 231–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, Manfred. 2007. Monotheism. In Encyclopaedia Judaica. Edited by Fred Skolnik. New York and Jerusalem: Macmillan/Keter. [Google Scholar]

- Wansbrough, John. 1977. Qur’anic Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wansbrough, John. 1978. The Sectarian Milieu. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, W. Montgomery. 1953. Muhammad at Mecca. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, W. Montgomery. 1956. Muhammad at Medina. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, Montgomery, and M. V. McDonald. 1988. The History of al-Ṭabarī Vol. VI. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Alfred. 1986. The Mysterious Letters. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill, vol. 5, pp. 412–14. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Alfred. 1997. Sura. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill, vol. 9, pp. 885–89. [Google Scholar]

- Zawanowska, Marzena. 2012. The Arabic Translation and Commentary of Yefet Ben ‘Eli The Karaite on the Abraham Narratives (Genesis 11:10–25:18). Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | al-Saqā (n.d.), Al-Sīra al-Nabawiyya, vol. 2, pp. 236–37; ibn Sa’d ([1418] 1997), vol. 1, pp. 224–26; al-Ṭabarī 1405/1984, sct. 30, vol. 15, pp. 251–53. |

| 2 | Q96:1–4. The Arabic here is rendered in transliteration meant to convey something of the sound as it might have been heard (i.e., it does not separate the words as found in printed Qur’ans, but rather as it would be heard in recitation). |

| 3 | On Muhammad’s position within the genealogy of biblical prophets, see (Newby 1989, pp. 21–25; Powers 2007, pp. 3–10, esp. p. 8). On Muḥammad’s purported reluctance, see continuation of Al-Sīra al-Nabawiyya (op cit), and also continuation of Ibn Sa’d (op cit); On ethical monotheism, see (Vogel 2007, vol. 14, p. 449). |

| 4 | Q.17:105–6; 25:5–6; 33:39–46; Khan, (ed.) n.d., Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhāri Revelation 2 (vol. 1, p. 2), Knowledge 127 (1:94); Merits of the Anṣār 190 (5:120), etc. For a recent overview regarding the Islamic tradition literature known as Ḥadith, see (Roberto Tottoli 2014) Hadith, Muhammad in History, Thought and Culture, 231–36. On the nature and historical reliability of Ḥadith, see (Joseph Schacht 1964), An Introduction to Islamic Law; (G. H. A. Juynboll 1983), Muslim Tradition; (Harald Motzki 2002), The Origins of Islamic Jurisprudence. |

| 5 | John Wansbrough (1977) applied the term Heilsgeschichte to the Qur’an and its interpretation. On the notion of history and metanarrative (or sometimes, master narrative), see (Carr 1991). |

| 6 | Ibn Hisham himself admits to censoring the most authoritative source (Ibn Isḥāq) for the history of Muhammad in Islamic sources (Lecker 2010, p. 62). Earlier attempts to decipher the sources by scholars such as Montgomery Watt (1953, 1956) have been highly criticized in recent decades for lack of an adequately critical methodology. Revisionist scholars such as Patricia Crone argue that the classic sources cannot be trusted for reconstructing the actual events, while more positive historians recently, such as Schoeler (2003) and Motzki (2003) take a more optimistic view. |

| 7 | The early project of Patricia Crone and Michael Cook to reconstruct the early history of Islam through extra-Islamic sources is well-known (Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World [Cambridge: Cambridge University, (Crone and Cook 1977)]). This, too, has been highly criticized while simultaneously praised it for its innovative approach. See also (Hoyland 1997). |

| 8 | For recent and comprehensive representations of the state of the question, see (Rose 2001, pp. 1–7; Schoemaker 2012). |

| 9 | Al-Saqā (ed. Sīra) 1:242. |

| 10 | Saqā (ed. Sīra) 1:264: ḥattā dhakara ālihatihim wa`ābahum … (“until he mentioned their gods disparagingly. When he did that, most of the rejected him and came together to brand him as an enemy, except those God protected from that through Islam, but they were few and concealed themselves.”). |

| 11 | Sometimes translated as “associaters” who associate other powers with God. Further, see (Hawting 2002; Schöller 2002). |

| 12 | (Brocket 1993). |

| 13 | Jews are generally thought of as challenging Muhammad after his arrival in Medina, but they are portrayed in the Sīra as coming to Mecca to test him when his fame first reached them in their settlement of Yathrib/Medina (Al-Saqā (Sīra) 1: pp. 191–92). |

| 14 | On the various roles and commonalities of prophetic representations, see Beinhauer-Köhler, Bärbel, Jörg Jeremias, Rebecca Gray, Maurice-Ruben Hayoun, David Aune, Frieder Ludwig, and Uri Rubin, “Prophets and Prophecy.” (Beinhauer-Köhler et al. 2011, vol. 10, pp. 441–50). |

| 15 | On medieval polemics between Judaism and Islam, see (Stroumsa 1997; Jacobs 2005). |

| 16 | English translations of the Sīra are derived from Guillaume (1955) (Sīra), p. 94; Cf. Haq (n.d.) (Ibn Sa’d), vol. 1, p. 183. |

| 17 | (Guillaume 1955 (Sīra), pp. 93–94). |

| 18 | (Haq n.d. (Ibn Sa’d), vol. 1, p. 186). |

| 19 | (Guillaume 1955 (Sīra), p. 227; Watt and McDonald 1988 (Ṭabari), vol. 6, p. 151; Khan 1983 (Bukhārī), p. 929). |

| 20 | (Guillaume 1955 (Sīra), p. 241). |

| 21 | Abdullah is identified as a ḥabr in the Arabic, which equals the position of the Talmudic ḥavēr (Baba Batra 75a). |

| 22 | (Guillaume 1955 (Sīra), pp. 240–41). |

| 23 | All scriptural material is rendered in italics to distinguish it from the interpretative material included in the commentaries’ paraphrases. |

| 24 | Maḥallī (Jalalayn) s.v. Q.2:146. See also Ibn `Abbās (1992) (Tafsīr) sv. Q.2:146, etc. Similar readings are made of 46:10, … washahida shāhidun min banī isrā’īl `alā mithlihi (“someone from the Children of Israel witnessed to its like”), referring to the previous verse in which God says presumably to Muhammad, “Say: I am not a novelty among Messengers. I know not what is to be done to me or you. I merely follow what is inspired to me. I am nothing but a manifest warner.” “Ibn Salām and his followers” are often mentioned in the commentaries as those Jews who do right, while most Jews do wrong. |

| 25 | (Guillaume 1955 (Sīra), p. 94; Haq n.d. (Ibn Sa’d), 1, p. 183). |

| 26 | See (Lecker 2012, p. 178) & notes 4 and 5 for the various versions of the tradition: lawi ttaba`anī `ashara mina l-yahūd lam yabqa fī l-arḍ yahūdi illā ttaba`anī. In another version, it is 10 learned Jews: law āmana bī `ashara min aḥbāri l-yahūd la-āmana bī kull yahūdī `alā wajḥi l-arḍ. |

| 27 | See, for example, Q. 2:63–66, 89; 3:70, 98; 4:154–55, etc. Cf. (Rose 2001). Some verses note that a few Jews remained loyal to God, such as 2:83, 159–60; 4:46, but the language can be quite telling even with its exception, as in the last reference: walākin la`anahum Allahu bikufrihim falā yu’minūn illa qalīlan (“But God has cursed them for their disbelief, and so they do not believe, except for a few.” |

| 28 | There were a few occasions in which Jews lived outside the reach of Christian and Muslim power, and in such situations they sometimes became politically dominant. One example is the relatively well-known medieval Khazar state, though we still remain uncertain about the extent of its Jewish nature (Brook 2002). Another was the pre-Islamic Jewish Ḥimyar kingdom in South Arabia (Bowersock 2013), about which we similarly know very little. And if we are to draw historical conclusions from Islamic sources, the Jews of Yathrib/Medina held power before and to a certain extent during the beginning of Muhammad’s residence there (Lecker 1995; Rose 2001, pp. 10–29). There exists no Jewish record from any of these three communities, and the norm was that Jews lived as weak minorities under foreign domination. This situation profoundly influenced the manner and substance of Jewish polemics. |

| 29 | (Daniel [1960] 2000, pp. 150–57, esp. p. 152; Tolan 2002, pp. 40–44). |

| 30 | (Lewis 1950, pp. 308–38) (in the various versions of the apocalyptic tale, Edom or Rome represents Christianity and Ishmael represents Islam). |

| 31 | (Ben-Shammai 1984, p. 39; Jacobs 2007, pp. 356–57; Schlossberg 1990a, pp. 28–29). |

| 32 | (Firestone 2018, pp. 1–2 and sources there; Eph’al 1976, esp. p. 234). |

| 33 | For references to Jewish assessments of Muhammad’s success as political leader but not as prophet, see (Schlossberg 1990a, p. 50; Zawanowska 2012, pp. 106–7). |

| 34 | The claim of scriptural distortion is usually referred to as taḥrīf (“distortion”) in Islamic tradition. See (Gaudeul and Caspar 1980; Adang 1996, pp. 223–47; Lazarus-Yafeh 1992, pp. 19–48; Nickel 2011). |

| 35 | These are known as a`lām (signs) or dalā’il (proofs) of prophecy. Further, see (Stroumsa 1985; Lazarus-Yafeh 1992, pp. 75–109; Schmidtke 2011; Roggema 2014). |

| 36 | The claim of abrogation is referred to as naskh. Further, see (Lazarus-Yafeh 1992, pp. 35–41; Adang 1996, pp. 192–222; Wansbrough 1977, pp. 192–202; Wansbrough 1978, pp. 109–13). |

| 37 | See, for example, (Ben-Shammai 1984; Schlossberg 1990b; Sklare 1999). |

| 38 | (Cahen 1983; Astren 2010); Adang and Schmidtke (2010), especially pp. 85–86. Adang and Schmidtke point out correctly that Jews did indeed write negative polemics against Islam in the Muslim world, but the output was meagre, and the paucity of Jewish polemical writings was influenced by the danger that negative rhetoric against Muhammad and the Qur’an naturally precipitated. |

| 39 | The oral nature of any discourse is difficult to prove, but the work of Milman Parry and Albert Lord have shown the oral underpinning of important classic literatures (Parry 1971). My work on the story of the ten Jewish sages who infiltrate the early entourage of Muhammad has led me to (unwritten) oral versions of this thousand-year-old story that continue to circulate among Jewish communities in the Muslim world to this day. |

| 40 | On history and counter-history, see (Funkenstein 1993, especially chp. 2; Biale 1999). See also (Strauss 1952). |

| 41 | A similar Jewish story retells the Gospel in a manner that refutes the Christian perspective. See further, (Schäfer et al. 2011). Christian thinkers also developed their own counter-narratives of the early history of Muhammad. Further, see (Roggema 2009). |

| 42 | One example will be examined below. On the Cairo Geniza, see (Goitein [1967–1973] 1993) and an abridgment in one volume by Lassner (1999). For a compelling story of its discovery, value, and the scholarship that continues to be produced, see (Hoffman and Peter 2011). |

| 43 | (Mann 1921/1922; Leveen 1925/1926; Gil 1993; Shtober 2011; Firestone 2014). I am currently preparing a monograph that will include a full study of the theme from its earliest attestation to the present and which will include all extant versions of the story, including versions continuing to circulate in oral form among Jews in the Muslim world. It is beyond the scope of this article to provide details here. |

| 44 | (Mann 1937/1938, pp. 426, 430, 432; Marmorstein 1922, pp. 55–57; B. Cohen 1929). |

| 45 | Literally “sign of disgrace.” Just as Jews rarely referred to Muhammad by name, they rarely referred to the Qur’an by name. It was common to use pejoratives as a kind of code. See further, (Avishur 1997). |

| 46 | The word “Israel” in traditional Jewish literature does not refer to a nation-state but to a people that believes it derives from twelve ancient tribes representing the twelve sons of the biblical Jacob. Jacob’s name was changed to Israel when he received a blessing at the Jabok River after struggling with an unidentified being (Gen.32:28), after which it became common for Jews to refer to the entire community as the “Children of Israel” or simply “Israel” |

| 47 | The original ms. is located in the Taylor-Schechter Collection in Cambridge: T-S 8 K202, embedded in what Mann (1921–1922) called “a polemical treatise by a Rabbanite Jew directed against Karaite and other sectaries [and which accuses them] of eclecticism, borrowing alike from Samaritans, Christians, Muhammedans, and Brahmans.” (p. 125). For the early history of scholarship on the episode, see Schwabe (1931, p. 77). Hoyland (1997) comments on it, pp. 505–8, as did Gil (1993, 2004) and Shtober (2011). |

| 48 | On chapter titles of the Qur’an, see (Welch 1997). |

| 49 | Mann (1937–1938), p. 421 and n. 24. Mann also offered other vocalizations: “לְאַלָּם, the violent (person), or לאַלַּם, to silence (the wicked one),” but the association with Is. 56:10 seems correct. |

| 50 | Cf. Isaiah 56:10; Jer.6:17; Ezekiel 3:17; Hosea 9:8. |

| 51 | Generally termed gezerah shavah, by which a common word found in to passages links them and offers an analogy between them. |

| 52 | (Welch 1986; Massey 1996, 2003). |

| 53 | Hebrew letters are commonly used in pre-modern texts to indicate numbers, dates and acronyms. They are usually indicated as such through a variety of notations, including the writing of bars over the letters in manuscripts. |

| 54 | (Leveen 1925/1926, pp. 399–406). Like the Hebrew version, the manuscript derives from Elkan Adler’s personal collection and is listed in CHM under historical works as #2554 קצה¨ אצחב מחמד, with the following explanation: “An account of the alleged Suras in the Koran with a list of Jewish followers of Mahomet.” |

| 55 | (Gil 2004, pp. 7–8). |

| 56 | Judeo-Arabic can refer to a variety of Jewish dialects of Arabic, usually written in Hebrew letters as in this case. |

| 57 | The purpose of an acrostic is to insert a message within a series of phrases or sentences by coding it into the first, last or other letters within a line. When the letters are read independently of the words in which they are found, they reveal a new message, an aesthetic pattern, or provide mystical meaning. The technique is quite old and is found repeatedly in the Hebrew Bible, often as alphabetical constructions (Proverbs 31, Psalms 9, 10, 25, 34, 111, 112, 119 and 145). Acrostics or acrostic-like techniques also occur in other ancient Near Eastern literatures, but they are much more common in post-biblical literature, especially in Jewish liturgical poetry. See further, (Landsberger 1936). |

| 58 | This might seem to relate directly to the use of the negative reading of an acronym for the mysterious letters prefixing sura 19: כה יעצו = כ.ה.י.ע.צ. = ك ه ي ع ص = “thus they advised” [Muhammad]. See (Baneth 1932, p. 114; Hoyland 1997, p. 508, n. 193), but all of our texts have כך יעצו, not כה יעצו. |

| 59 | Readers with Hebrew or Arabic language background will recognize that while the right column is written in Hebrew letters, the language is not Hebrew but Arabic. The dots over the letters replicate the way they appear in both the Hebrew and Arabic manuscripts. The purpose of dots, as noted above, is to mark particular letters as having meaning that transcends the usual purpose of alphabetic symbols in articulating sound. |

| 60 | Cf. Qur’an 1:7. |

| 61 | אלנבי occurs above the line, added or corrected after the line was complete. |

| 62 | Note the use of ס rather than ש. |

| 63 | שרי occurs above the line. |

| 64 | The ר appears to have been added later between line ס and line אל to complete the acrostic, but without a verse associated with it. |

| 65 | Another unintelligible word or marking appears here to signify the end of the set of verses. |

| 66 | On the whole, Jews lived better under Muslim rule than under Christian rule, but Jewish writings note the scorn and derision that they often experienced. On the complex issue of the status of Jews under Muslim rule, see (M. Cohen 1994; Stillman 1979). For specific locales and periods, see (Stillman 2010). |

| 67 | See (Firestone 2014). |

| 68 | See (Assman 2010; Jaffee 2001; Firestone 2005). |

| 69 | Further, see (Cronin 2008). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).