1. Introduction

In this paper, I examine the concepts of art and shamanism, their emergence as terms in European thought, and the way in which they have been perceived to interface in various ways, over time. I show how the terms art and shamanism emerge at the same time and quickly become entangled in European thought, from the late Renaissance. Drawing on Gloria

Flaherty’s work (

1988,

1989,

1992), which sets out how the shaman was co-opted as the performing artist of higher civilization in the eighteenth century, I propose that the discovery of Upper Palaeolithic cave art in Europe in the nineteenth century, and its authentification in the early twentieth century, enabled the co-option of shamanism into the visual arts. By the mid-twentieth century, some scholars, Mircea Eliade among them, posited an immutable relationship between art and shamanism, from prehistory to the present. While this outmoded metanarrative is not supported by most specialists today, it endures in other arenas, including in the self-identification of artists who universalize their endeavours by linking themselves to shamans.

I draw upon Goethe’s concept of ‘elective affinities’ (

Die Wahlverwandtschaften, 1809), the tendency of certain substances to combine in preference to others, and Max Weber’s later reformulation of the concept as a ‘Goethean chemical metaphor’ (

McKinnon 2010), to engage critically with how such ideas and things as art and shamanism have become entangled due to a variety of social, cultural and historical elements. I apply Foucault’s understanding of ‘discourse’ in

The Order of Things (

Foucault [1966] 1970)—as ‘ways of constituting knowledge, together with the social practices, forms of subjectivity and power relations which inhere in such knowledges and relations between them’ (

Weedon 1997, p. 108)—in order to demonstrate that art and shamanism are terms which have been imagined and entangled over an extensive period, from the Renaissance to the present. I argue that the elective affinity between art and shamanism is a problematic modern concept based on misleading stereotypes of shamanism, such as hypersensitivity, neurosis, individual genius, divine inspiration and transcendental artistic creativity, operating outside of social norms, that are counter to anthropological knowledge of shamans. Ongoing attempts to single out shamanism as the origin of religion (e.g.,

Kim 1995), cave art as the origin of art (e.g.,

Sandars [1968] 1995, pp. 66–67), and cave art as both the origins of both art and religion (e.g.,

Gombrich [1950] 2007;

Lommel 1951;

Bataille 1955;

Makkay 1999;

Caruana 2001, p. 7;

Spivey 2005;

Benycheck 2014), arguably tell us more about Eurocentric thinking than about shamans and the cave artists themselves. And while contemporary artists have been labelled as inspired visionaries and the inheritors of an enduring tradition of shamanic art (e.g.,

Tucker 1992;

Levy 1993,

2011;

Laganà 2010;

Benycheck 2014;

Thackara 2017), this metanarrative relies on outdated literature and lacks critical engagement with how art and shamanism have been contrived academically, and are situated in specific historical and social contexts.

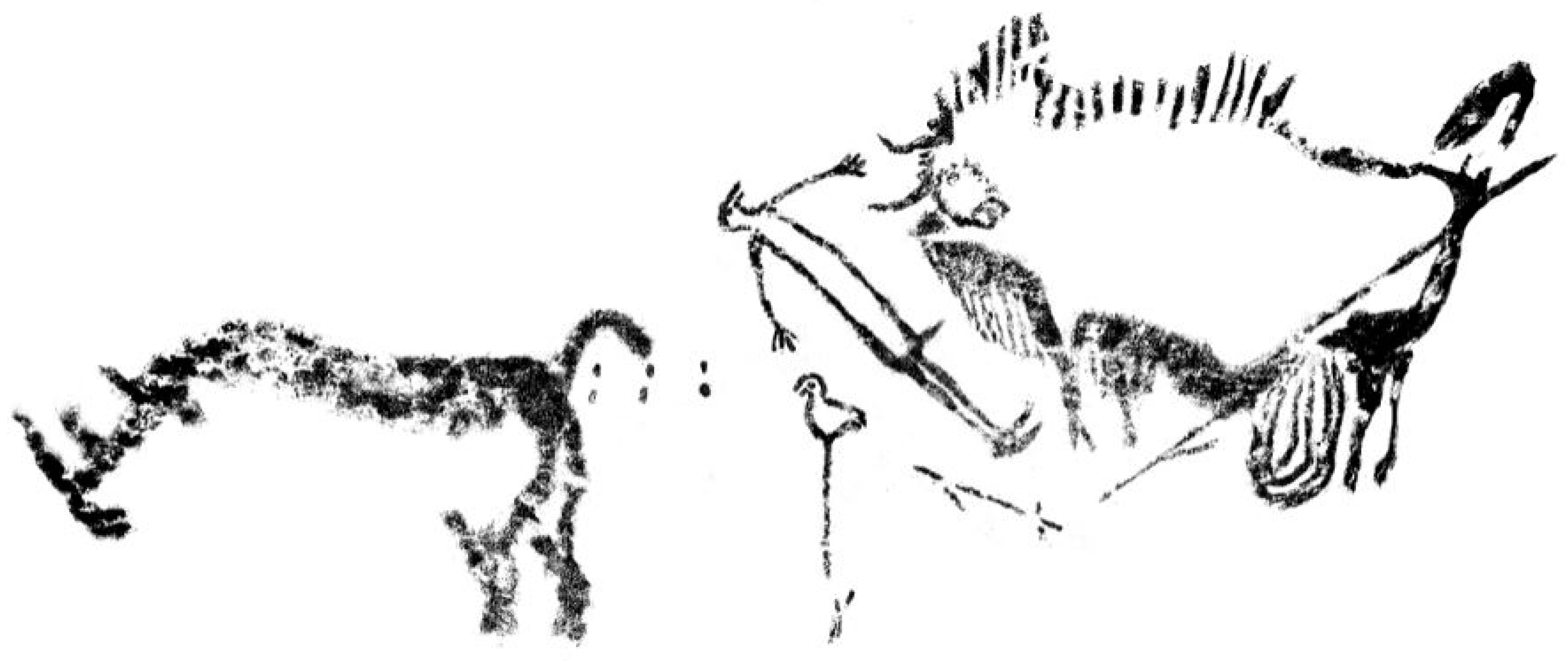

I begin by setting out the broad terms of my argument with three contrasting artworks from across cultures and through deep time, from prehistoric cave painting to contemporary art, which despite their obvious differences are related by virtue of the concept of shamanism which has been applied to them. The first is the so-called ‘scene in the shaft’ of the cave of Lascaux in the Dordogne, France (

Figure 1), dating to between 15,000 to 20,000 years BCE. The scene in the shaft is typically interpreted as a hunting scene showing an eviscerated bison beside the hunter he has wounded (e.g.,

Gombrich [1950] 2007), as a form of sympathetic magic, the imagery painted in order to affect the hunt (e.g.,

Reinach 1903), or as a shamanistic visionary or trancing scene, one aspect of which might be the partial transformation of the shaman into a bird spirit (

Davenport and Jochim 1988;

Lewis-Williams 2002).

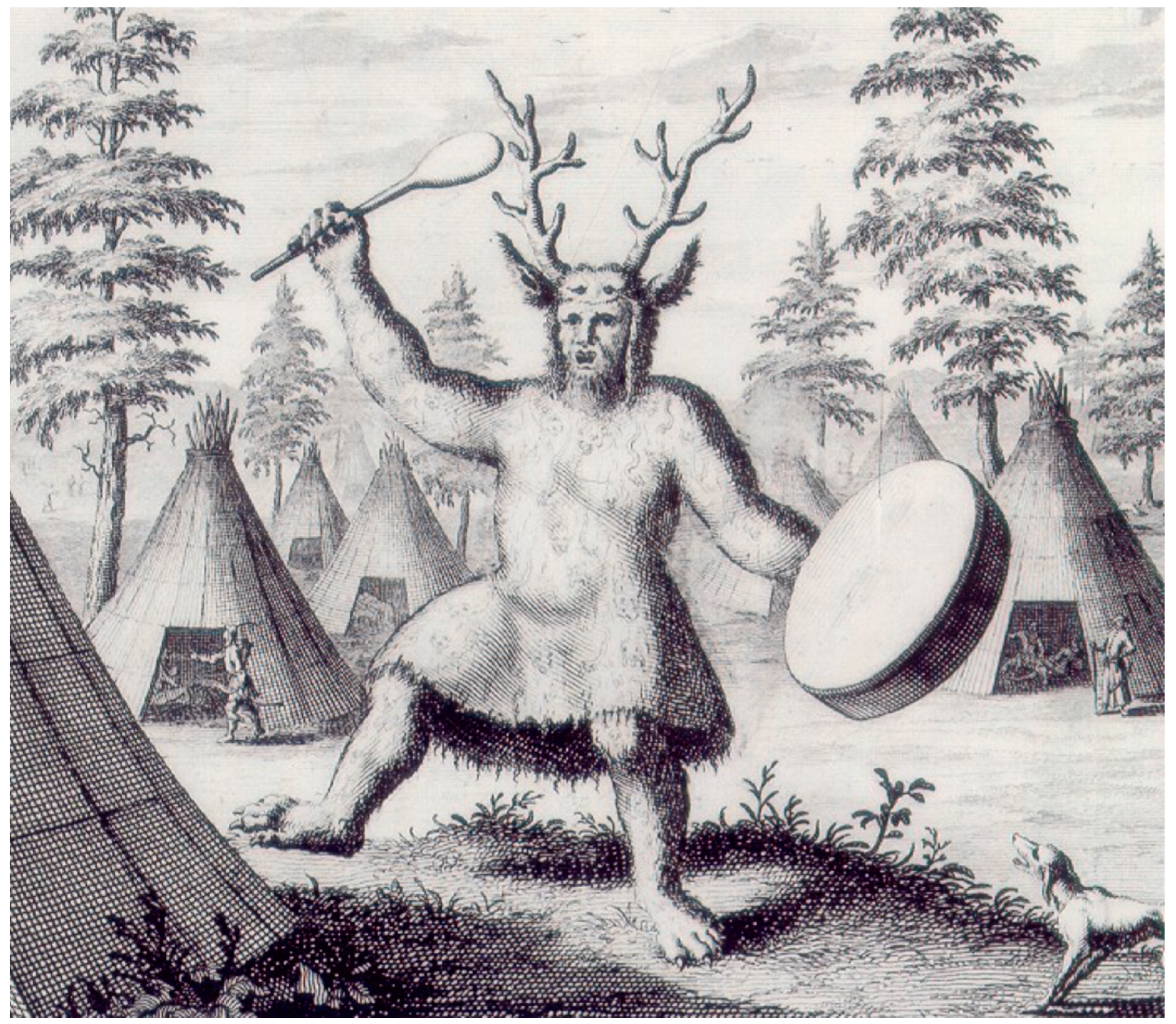

The second image shows the first visual record of an indigenous Siberian shaman by a European, in an engraving by the Dutch statesman Nicolaes Witsen who travelled in Russia, published in 1692 (

Figure 2). The image features ethnographic aspects, such as the shaman’s drum, but also fantastical elements such as the clawed feet; Hutton argues that ‘Witsen’s shaman is himself a demon’ (

Hutton 2001, p. 32), reflecting Witsen’s Christian bias. The engraving became very popular and was influential in disseminating the idea of the ‘shaman’ across Europe (

Hutton 2001, p. 32).

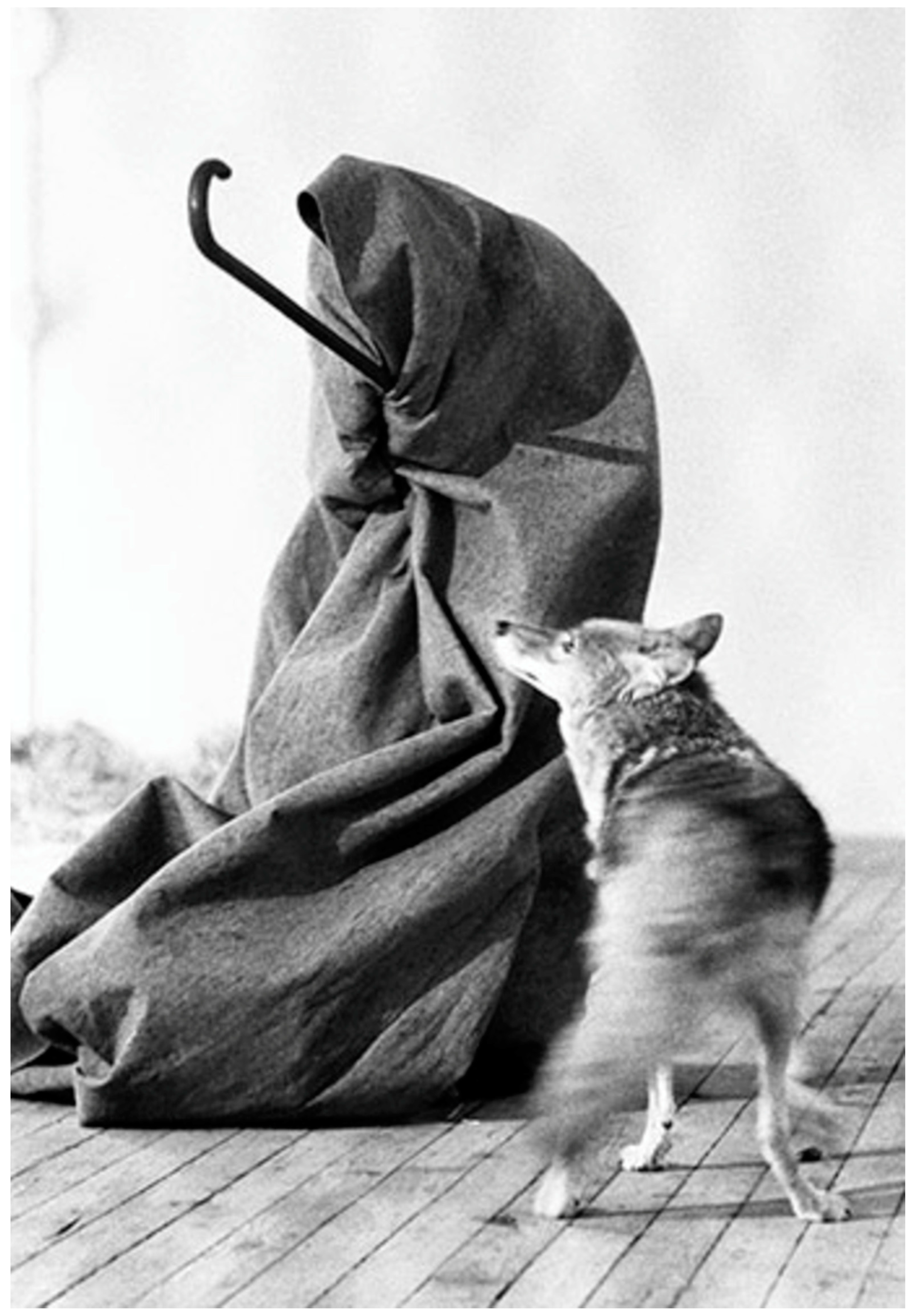

By contrast,

Figure 3 shows the German artist Joseph Beuys sat in a warehouse in New York City, wrapped in felt, the insulating material he thought had ‘alchemical’ properties, holding the walking stick he used as a ‘conductor’ to the spirit realm, while an apparently wild Coyote tugs at his blanket. Beuys self-identified as a ‘shaman’, insisting on the role of the artist as a healer of profound social ills (e.g.,

Antliff 2014; and for full discussion

Walters 2010). Other modern and contemporary artists of the twentieth century, from Van Gogh and Wassily Kandinsky to Damien Hurst, and performing artists too such as the musicians Jim Morrison, Lou Read and David Bowie, have been labelled or labelled themselves ‘shamans’.

Treating these three works separately rather than as linked by the general terms art and shamanism, it is clear that they are unrelated in fundamental ways, such as in terms of medium, date, and social and cultural context. Despite these radical differences, for some thinkers the connective thread of shamanism makes perfect, if problematic, sense, raising the concern of why and how such a wide range of art and almost any artist, has been termed a ‘shaman’—from Palaeolithic cave artists to artists of the ‘white cube’ contemporary gallery space. The idea that shamanism links all artists through time is raised in Joseph Campbell’s (1904–1987),

The Power of Myth (1991), a highly successful PBS series broadcast in 1988 with a best-selling companion book, which proposed that contemporary artists are the shamans of the occident.

Moyers: Who interprets the divinity inherent in nature for us today?

Who are our shamans?

Campbell: It is the function of the artist to do this. The artist is the one who communicates myth for today’.

This idea is treated in detail by Michael Tucker in his book

Dreaming with Open Eyes: The Shamanic Spirit in Twentieth Century Art & Culture. He proposes, ‘The prehistoric shaman remains the archetype of all artists’ (

Tucker 1992, p. xxii), ‘Van Gogh is the key initiatory figure in the modern version of the romantic…artist as suffering visionary’ (

Tucker 1992, p. 1) and ‘The struggle to exalt existence, to invoke the mysterious totality of life … links the … worlds of Modern art and shamanism’ (

Tucker 1992, p. 2). Published a year later, Mark Levy’s

Shamanism and the Modern Artist: Technicians of Ecstasy, reinforces this view and focusses similarly on the apparent psychosis of artist and shaman, proposing that ‘some artists have resumed the ancient role of the shaman’, ‘the shaman gets relief from his neurotic condition…in artistic expression’, and ‘the “call” in shamanism is related to the artistic process’ (

Levy 1993, pp. xv–xvi). More recently, Benycheck has proposed that ‘the earliest known indications of shamanic art’ (

Benycheck 2014, p. 211) emerge in the Paleolithic and that women were ‘the earliest shamans and artists’ (

Benycheck 2014, p. 215).

The equation of art and shamanism in this way generalises and universalises them as etic categories which can be applied in any context across all cultures, neglecting social, historical and ecological specificity, diversity and nuance. It also singles out art and shamanism as intrinsically related features of human experience, achieved by appeal to the universality of human consciousness or ‘psychic unity of mankind’, originally set out by Adolf Bastian (1826–1905) (see

Koepping 1983;

Ingold 2018, p. 64) which relates all religions on a continuum (e.g.,

Huxley 1945;

Campbell 1949; see discussion by

Dubois 2009, pp. 266–67). Vast time periods are collapsed in these accounts, the tens of thousands of years separating modern artists from the earliest prehistoric artists eroded in one fell swoop. The application of the terms becomes so broad that they cease to fulfil a meaningful function, decontextualizing artworks, artists and shamans from their specific social contexts. And, this thinking romanticises artists and shamans as individuals who are somehow, perhaps via such vague terms as ‘genius’ or ‘neurosis’, uniquely connected to a special or dangerous realm of inspiration. In order to critically examine how this entanglement of art and shamanism has come about historically and persists in the non-specialist scholarship, insisting on artist-shamans from prehistory to the present and across cultures, I next trace the construction of the terms and the history of their relationship in Western intellectual history.

2. Defining ‘Art’

The origin of both the terms art and shamanism can be traced to the Renaissance. There was no direct equivalent to the term ‘art’ before Giorgi Vasari (1511–1574), the ‘father of art history’, or outside Europe. But it is worth highlighting certain thinking prior to this which has relevance to how the modern term was conceived. The Greek term

demiourgos, ‘one who works for the people’, refers equally to a baker or painter, without privileging the artist over other makers. Plato (c.428–348 BCE) focussed on poetry rather than the visual arts as being derived from the muses, used the term

mimesis, ‘imitation’, to talk about painting and sculpture, and his notion of universal ideal forms engages with aesthetics but similarly does not single out art objects (from other forms of materiality or visuality) for special treatment (

Preziosi 1998, p. 109). Pliny the Elder’s (23–79 CE)

Natural History (which ‘set forth in detail all the contents of the entire world’) comments on contemporary Roman art and the history of the arts, attributing the origin of art to the tracing of one’s shadow, and setting out a broad scheme of artistic developments in terms of a ‘birth-development-decline’, setting a range of artists in historical context and judging their aesthetic value (

Fernie [1995] 2001, p. 10). The Christian theologian Saint Augustine (354–430 CE) was guided by Plato’s aesthetics in assessing religious images, asserting that ‘beauty’ is intrinsic, not in the eye of the beholder, and derived from God—a notion that would be re-deployed in the Renaissance and early modern concept of art (

Preziosi 1998, p. 171).

Giorgio Vasari, a painter and student of Michelangelo as well as an architect and collector, known today as the ‘Father of Art History’, stands out as initiating the broad, ‘generalist’ (

Svašek 2007, p. 14) understanding of art as we know it today (e.g.,

Preziosi 1998). In

The Lives of the Artists published in 1550, revised in 1568 (

Vasari 2008), he identified and advocated certain core artistic values and celebrated artists and patrons as those who advance civilisation. He singled out Michelangelo as the greatest of all artists (a trope persisting into the present) and emphasised the artist as an inspired

genius in contrast to the lowly artisan. Vasari ascribed specific values to art, iterated the gifted individual artist, and articulated divinely inspired genius as being at the root of creative inspiration and artistic quality. He also made a clear delineation between high ‘art’ and low ‘craft’ (that is, elite drawing, painting and sculpting practices from the manual labour of craft production), and separated art and artists from society, as special categories. All of this was formative in the construction of the institutional concept of ‘Art’, an awkward concept we continue to wrestle with—the ‘Tyranny of the Renaissance’, as

Renfrew (

1961,

2003) calls it (see also e.g.,

Wolff 1981;

Staniszewski 1995).

The eighteenth century reproduced and reified these themes within a more academic frame than the province of artists and connoisseurs (e.g.,

Pasztory 2005, p. 7). Johann Joachim Winkelmann (1717–1768), in

Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (

Winkelmann [1755] 1987), defines the essence of Greek sculpture (and the Greeks themselves) as ‘noble simplicity and quiet grandeur’ and addresses how and why people have been drawn to it, arriving at a model in which all art must have a birth, development and decline. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) departed from this model and defined art in discrete terms as separate from society, produced by an individual genius who is divinely inspired. In his

Critique of Judgement (

Kant [1790] 2009), Kant considers how we make judgements or distinctions between things in terms of beauty, arguing that an aesthetic response occurs when imagination and understanding are activated. In an influential move away from Vasari and Winkelmann, he thought that this aesthetic response concerns form and design alone as opposed to history or context, contributing to the development of formalist art history and the examination of art without attention to historical or social context. Johann Wolfgang Goethe (1749–1832) also departed from the ‘birth-development-decline’ model in his analysis of Gothic architecture (previously defined by the influential Vasari as degenerate) as beautiful and harmonious (

Fernie [1995] 2001, p. 12). It is also in the eighteenth century that a dealer-critic system emerges, sanctioning what is and what is not good art based on aesthetic quality and the originality of the work of art.

In the nineteenth century, Hegel (1770–1831) approached art as a form of symbolism, a vehicle for ideas (e.g.,

Pasztory 2005, p. 8). Aligning with Kant (and Vasari before him), Hegel saw art as essentially representing and articulating the Holy Spirit in material form, and he recognised a long historical trajectory of realising the divine idea, with different artistic styles merely evidencing the confused ways in which human beings attempt to grasp unchanging deific perfection (

Preziosi 1998, p. 451). Alois Riegl (1858–1905) further perpetuated these established enlightenment ideas, seeing art as governed by universal laws, ‘the will to form’ or

Kunstwollen (

Preziosi 1998, p. 169). But Riegl did disrupt the art/craft divide, arguing that any object could reveal the character of a particular age or culture (addressing Maori art, for instance) and was worthy of study and distinctive in its own right rather than as part of a monolithic ‘birth-development-decline model. Heinrich Wölfflin (1864–1945), none the less, sought universal principles governing art and history, ascribing a grand historical cycle of ‘early’, ‘classic’ and ‘baroque’ styles (

Preziosi 1998, pp. 115–26).

So, from the Renaissance to the first half of the nineteenth century, ‘art with a capital A’ became defined and ingrained as a concept encompassing creativity, genius and divine inspiration, practiced within an elite sphere separate from mainstream society. This episteme has been challenged successfully by various schools of thought including those which are Marxist, feminist, post-colonialist and queer, because of the way in which it devalues, marginalises and/or excludes visual culture outside of a Eurocentric frame. Yet this canonical concept of art lingers with persuasive influence not only in popular understanding but also within art history and other areas of the academy, no doubt partly because of its historical pedigree and power (e.g.,

Wolff 1981;

Staniszewski 1995;

Dowson 1998).

3. Defining ‘Shamanism’

Aligned closely with this historical trajectory for our modern term ‘art’ is the Western understanding of ‘shamanism’. The earliest written account of a phenomenon which would later be termed ‘shamanism’ precedes Vasari’s first edition of

The Lives of the Artists by only fifteen years. The historian and writer Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo, whose work was published in 1535, describes Caribbean elders using tobacco to communicate with ‘the Devil’. Viewing the practice through a prejudiced colonial, Christian lens, he sets the tone for records on shamanism until eighteenth century humanism and rationalism intercede. The earliest recorded eye-witness account of a shaman in Siberia, the ‘locus classicus’, is on New Year’s Day in 1557, when the Englishman Richard Johnson witnessed on the north-west coast of Siberia what he described, similarly, as ‘devilish rites’ (

Hutton 2001: 30). I think it no coincidence that these emerging reports on shamanism were during Vasari’s lifetime: art and shamanism not only emerge simultaneously in Western imagination, but they soon become entangled. The first use of the term shaman in print was in the memoirs of the exiled Russian churchman, Avvakum Petrovich, in 1672 (

Hutton 2001, p. vi;

Petrovich 2001). Almost 150 years after Johnson’s account, the first visual record of a Siberian shaman was Witsen’s 1692 engraving (

Figure 2), via which the term ‘shaman’ probably reached Europe (

Hutton 2001, p. vi). The earliest recorded eye-witness account of a shaman in Siberia, then, was during Vasari’s lifetime; and the first visual representation of a Siberian shaman was published on the cusp of the European Enlightenment. As such, the concepts of art and shamanism emerge at the same time in Western imagination, and they soon become entangled.

As with the term art, ‘shamanism’ becomes crystallised in the eighteenth century, as examined by Gloria Flaherty in her book,

Shamanism and the Eighteenth Century (

Flaherty 1992; also

Flaherty 1988,

1989; see also

Znamenski 2004). Explorers and missionaries, mainly German, following Johnson and Witsen among others, encountered and reported back on shamanistic practices among Tungus-speakers and other Siberian communities. The generic German term ‘schamanen’, derived from the Tungus ‘sharmarn’, became ‘shamanism’ in English, used as ‘a convenient metaphor’ (

Znamenski 2004, p. xix) to refer to a wide range of ritual practices involving healing, divination and magic, and the term was increasingly applied to practices outside of Siberia. In France, the publication of the

Encyclopédie (1751–1756), edited by Denis Diderot, rapidly disseminated and popularised Enlightenment thinking across Europe. Shamans are defined here for the first time: ‘“SHAMANS”, noun, masc. plural, is the name that the inhabitants of Siberia give to impostors who perform the functions of priests, sorcerers, and doctors’ (

Narby and Huxley 2001, p. 32). Diderot was educated by Jesuits but self-identified as an atheist and took an ambivalent approach to the occult, describing Siberian ‘shamans’ as ‘imposters who claim they consult with the Devil’ (

Narby and Huxley 2001, p. 32), and ‘jugglers’ as ‘magicians or enchanters much renowned among the savage nations of America’, but whose practices also ‘make one think that the supernatural occasionally enters into their operations’ (

Narby and Huxley 2001, p. 34) and that their pronouncements are ‘sometimes…quite close to the mark’ (

Narby and Huxley 2001, p. 35). There are numerous other references to shamans in the encyclopaedia in addition to this. Labelling in this way is a form of appropriation and control, and shamans were a hot topic during the enlightenment. Indeed, as Gloria

Flaherty (

1992) sets out, Diderot’s fascination with shamanism was not only key to the establishment of the term, but also represents a defining moment in the production and reproduction of an explicit and inseparable link between shamanism and performing art.

4. The Entanglement of ‘Art’ and ‘Shamanism’

Diderot’s novel

Le neveu de Rameau (Rameau’s Nephew) was conceived in the 1760s, revised in the 1770s after his trip to Russia and first published (in translation) by Goethe, in 1805. The book treats the role of irrationality in creative performance, identifying the character ‘Moi’ as the rational and enlightened European, while ‘Lui’ stands for ‘things shamanic: acting or illusion, flights of fancy or genius, irrationality, heated enthusiasm, emotional agitation, frivolity, and androgynous childhood’ (

Flaherty 1992, p. 127). Flaherty goes on to argue that ‘Diderot’s dialogue demonstrates the incipient convergence in the enlightened Western European mind of the characteristics of the shaman with those of what was evolving into the genius’ and specifically ‘the highly sensitive, creative performing artist’ (

Flaherty 1992, p. 131). She concludes, ‘Diderot’s

Le neveu de Rameau clearly shows that the performing artist was beginning to be considered the shaman of higher civilization—that is, eighteenth-century Western European civilization’ (

Flaherty 1992, p. 131). By the turn of the nineteenth century, then, intellectual understanding had fused art and shamanism into a single concept concerned with genius, inspiration, creativity and performance.

Continuing the construal of art and shamanism, Georg Forster (1754–1794) accompanied his father on an expedition into Russia commissioned by Catherine the Great, and was also enrolled on Captain James Cook’s (1728–1779) second voyage around the world. His published works, in the second half of the eighteenth century, made a number of references to art and shamanism, and their interface. According to Flaherty,

As with many explorers of the eighteenth century, Georg Forster’s experiences among other peoples and cultures made him think that the arts as known in eighteenth-century Europe had their origins in rather simple folk beliefs and rituals. He mentioned the shamanic séance and the concomitant ecstasy that was interpreted as a spiritual journey to strange and wondrous otherworldly places.

The German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) was one of the first to use the Germanicized ‘schamanen’ in print, in his

Alte Volkslieder (‘Old Folksongs’) of 1774. Herder proposed that Orpheus was ‘the noblest shaman’ and the mythical epitome of tribal shamans (

Flaherty 1992, p. 138), persisting from prehistory to the present:

Do you believe that Orpheus, the great Orpheus, eternally worthy of mankind, the poet in whose inferior remnants the entire soul of nature lives, that he was originally something other than the noblest shaman that Thrace, at the time also northern Tatary, could have seen. And so on. If you want to get to know the Greek Tyrtaeus, you should look where there is a war celebration with martial song and the singing leader of the North Alericans! Do you want to see ancient Greek comedy at its inception? It is still completely as Horace describes with the dregs and dance in the satyr plays and mummeries of those same primitives there!

Herder also thought that ‘cave dwellers’ had been so sensually oriented that images and actions composed their main means of communication. When they wanted to record their communication, they therefore produced pictographs and hieroglyphs. The discovery of prehistoric cave art was, I will argue, crucial in the crystallisation of the art-shamanism confluence, but it is worth highlighting that even before its discovery, Herder’s thinking on shamanism and art, and his prescient link between shamanism and rock art, laid the foundations for making a link between the origins of art and the earliest shamans. Other thinkers also thought of shamanism as the ‘most ancient faith’ and, as

Znamenski (

2004, p. xxiii) argues, ‘came to generalize about shamanism as the early form of universal religion’. The folklore scholar Grigorii N. Pontanin (1835–1920) went so far as to propose a Siberian origin for Judeo-Christian religions, stating that ‘central Asian shamanic legend…lies at the foundation of the legend about Christ’ (

Znamenski 2004, p. xxxi).

The blurring of shamanism and art by intellectuals continued from the late eighteenth into the nineteenth century. Flaherty discusses how many of these thinkers found particular value in discussing art and shamanism in terms of the interrelated concepts of artistic creativity, divine inspiration and ecstatic genius. By way of example, Mathieu de Lesseps (1771–1832), a French diplomat who had spent part of his childhood in St. Petersburg, writing in 1790 referred to the practitioner of séances as ‘a sorcerer, a gypsy, an artist, a magician, a prophet, and, most often, a

Chaman’ (

Flaherty 1992, p. 91). The physician Franz Anton May (1742–1814), furthermore, described shamans as ‘highly strung’ (

Flaherty 1992, p. 152), while Ferdinand von Wrangel (1796–1870), a German naval officer and explorer, argued in 1841 that ‘a genuine shaman at the peak of his ecstasy’ is subject to his ‘involuntary and uncontrolled intensely stimulated imagination’ (

Znamenski 2007, p. 4).

Znamenski (

2003, p. xxiv) sets out how such thinkers as Wrangell and the Russian explorer Frants Beliavskii portrayed shamans as ‘creative personalities with penetrating minds, strong wills, and ardent imaginations…Yet these “native geniuses”, as Beliavskii calls them, were people of tragic fate because their artistic and creative talents were wasted in the barren northern lands in daily routine ‘.

Taking account of this history of thinking on art and shamanism from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century, I agree with Flaherty that the early modern period not only defined the generic concepts art and shamanism in terms of inspiration and genius but also crystallised them into entangled master tropes. The stage was set, then, for the full extension of the art/shamanism interface from ethnographic examples and performing art in Europe, into prehistory. Two things were needed to make this leap: first, recognition of the origins of humanity in deep time beyond that of established biblical accounts, and second, discoveries of prehistoric cave art. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the first of these scientific discoveries would happen in England, the second in France. But it was only at the turn of the twentieth century that thinking on the two strands of evidence was brought together in order to make a clear case for prehistoric cave art as the origins of religion, specifically shamanism, and the origins of creative inspiration, or ‘art’.

5. Evolution and Human Origins

There were three key developments in the nineteenth century which can be brought to bear on the presumed affinity between art and shamanism, the origins of art and the origins of religion. First, in the early 1800s, finds of stone tools made by early humans in the same layers of sedimentary rocks also containing the fossils of extinct animals, began to challenge the biblical model of the universe and origins of humanity. Treating this evidence, Sir Charles Lyell (1797–1875), Professor of Geology at King’s College, London, set out in the three volumes

Principles of Geology, Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth’s Surface by Reference to Causes Now in Action (1830–1833), the idea of ‘uniformitarianism’, that ‘the present is the key to the past’. Lyell argued that certain rocks comprised of layers of sediment, laid down over millions of years and containing the fossils of extinct creatures, showed the deep chronology of the earth, beyond Christian imagination (

Lewis-Williams 2002, p. 20). Arguing against Christian thinking which saw these remains as the relatively recent petrified remains resulting from the Biblical flood of Noah, Lyell proposed that today’s gradual geomorphological processes such as sedimentary deposition and subsequent erosion, had resulted in the formation of fossil-rich rocks.

The second development was the work of Sir Charles Darwin (1809–1892), a close friend of Lyell. The idea that humans had evolved from apes was not new, but it was far from accepted. Darwin’s

On The Origin of Species: The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, published in 1859, proposed that natural selection was the mechanism for the process of one species evolving into another. The book was in instant bestseller and despite Christian dissent, it was increasingly clear to science that humanity had a very deep antiquity, far exceeding Biblical time. Darwin’s second volume,

The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) applied evolutionary theory to human evolution, specifically ‘the progress of the mind’ (

Ingold 2018, p. 62) and added to the debate over human origins. As

Lewis-Williams (

2002, p. 19) states: ‘The Western world had learned that it had a deep past, its concept of humanity had undergone profound changes, and its yearning to know the truth about its origins had risen to a level of unprecedented intensity: finding evidence for “Human Origins”, be it stone artefacts, fossils or genes, had become an absorbing passion’.

Added to these two developments, is the work of the ‘Armchair anthropologists’, Sir Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917), appointed as the first Reader in Anthropology at Oxford in 1884, and Sir James Frazer (1854–1941). While these two thinkers did not perform participant-observation fieldwork with indigenous communities, they did examine the beliefs and practices of these people as recorded by missionaries and explorers. In Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art and Custom (1871), Tylor proposed that by a process of cultural evolution, human societies had developed from simple to complex, from ‘savagery’ through ‘barbarism’ to ‘civilisation’, with the most ‘primitive’ form of religiosity expressed as animism, the ‘mistaken’ belief that objects are imbued with spirits. Frazer’s infamous The Golden Bough (two volumes 1890, three volumes 1900, twelve volumes 1915, abridged edition 1922, a thirteenth volume published 1936), explored the similarities between rituals, myths and beliefs across human societies worldwide and proposed an evolutionary development of religious thought beginning with ‘primitive magic’ which, he believed, would be replaced by religion, which in turn would be superseded by science.

Frazer also characterised two ‘principles of magic’, a ‘Law of Similarity’ and a ‘Law of Contact’. With sympathetic (‘imitative’ or ‘homeopathic’) magic, ‘the magician infers that he can produce any effect he desires merely by imitating it’. Contact or ‘contagious’ magic, on the other hand, supposes ‘that whatever [the magician] does to a material object will affect equally the person with whom the object was once in contact, whether it formed part of his body or not’. In the case of hunting magic, then, a hunter may represent his quarry (sympathetic magic) or carry a part of the animal he desires to kill (contagious magic), in order to affect the success of the hunt. Frazer proposed, like Tylor, that such beliefs are mistaken, and moreover that ‘magic is a spurious system of natural law as well as a fallacious guide of conduct; it is a false science as well as an abortive art’.

The application of cultural evolution in these accounts was challenged by succeeding generations of anthropologists because human societies do not ‘evolve’ as species do, living indigenous societies are not unchanged since antiquity and shamanism remains a practical, vibrant means of mediating between human and other-than-human persons today. None the less, the basic argument that the ‘savage’ tribes of the present were ‘fossils’ surviving from prehistory, and that their animistic, totemistic and shamanistic beliefs reflected the earliest forms of knowledge, albeit ‘incorrect’ knowledge in the form of false religions, has had immense and lasting power into the twenty-first century.

This thinking regarding the ancient origins of humanity and, in turn, primitive religion, laid the foundations for a crucial moment in the history of the convergence of art and shamanism—the discovery, authentification and interpretation of Upper Palaeolithic parietal art. The way in which cave art was interpreted as shamanistic during the first half of the twentieth century reinforced the historically intertwined discursive constructs of art and shamanism, co-opting shamanism into the visual arts, highlighting cave art as the origin of art and shamanism the origin of religion. Alongside a belief in the psychic unity of mankind, this conveniently eroded the cultural and chronological specificity of art and shamanism and enabled the identification of avant-garde artists as the inheritors of a singular shamanistic art tradition.

7. Cave Art and Shamanism

Following the confirmation of Upper Palaeolithic date for the art, a possible connection between shamanism and cave art began to be set out in the first years of the twentieth century. Girod and Massénat, for instance, suggested in 1900 that certain Palaeolithic-age ‘batons’ were used to beat shaman’s drums like those used by the contemporary Saami in Fennoscandia (

Girod and Massénat 1900). Three years later and one year after the find at La Mouthe, Salomon Reinach, then wrote his seminal article

L’art et le magic (1903), in which he states: ‘I believe it is quite legitimate, contrary to de Mortillet, to attribute to cavemen a developed religiosity’, and furthermore that ‘art in the Reindeer Age … was an expression of a religion, very coarse, but very intense, made of magic practices whose single purpose was the conquest of daily food’—and so, as Tomášková argues, ‘[t]he idea of “hunting magic” was thus born’ (

Tomášková 2013, p. 183; see also

Palcio-Pérez 2013).

There is ‘little correlation between the depicted species and excavated food remains from camp sites’ (

Whitley 2009, p. 30), so the interpretation of cave art in terms of hunting and magic is unconvincing (e.g.,

Bahn 1991;

Bahn 2010, p. 48;

Bahn and Vertut 1997, pp. 177–80; contra e.g.,

Hayden 2003;

Willerslev 2011). The interpretation has persisted none the less, perhaps partly because the expectation endures that early humans were primitive and superstitious, so that hunting magic seems to answer straightforwardly the question of why they made images of animals. It also persists, I think, because (the few) images of humans in cave art, and human-animal hybrids in particular—on which there has been an exaggerated emphasis in interpretation—are identified as supporting evidence in the key role of the sorcerer or shaman, the officiator of hunting magic.

Building on Girod and Massénat discussion of Palaeolithic shamanic drums in 1900, and on Reinach’s interpretation of cave art in terms of hunting magic, the Abbé Henri Breuil (1877–1961), the ‘Pope of Prehistory’, suggested in 1906 that therianthropic imagery might be interpreted as representing sorcerers or shamans (

Cartailhac and Breuil 1906). As Tomášková sets out in her book

Wayward Shamans: The Prehistory of an Idea (2013): ‘[w]hile Salomon Reinach provided the vocabulary and framed the discussion of art and magic, it was Breuil who offered the visual proof with an incontrovertible image of the being who would personify their union’ (

Tomášková 2013, p. 184), an image he identified in the cave of Les Trois Frères (Montesquieu-Avantès). The ‘three brothers’ of the cave’s name were the sons of Henri Bégouën who became lecturer in prehistory and director of the Museum of Natural History in Toulouse, and ‘tirelessly worked for the recognition of prehistoric art as a spiritual expression, a connection between a view of the world, artistic effort, and magic once performed by powerful shamans, sorcerers, and priests in the depths of the caves’ (

Tomášková 2013, p. 185). Images with spears and other projectiles wounding an animal, Breuil thought, following Reinach, were believed by the ancient painters to effect by magic the death of the real animal, the success of the hunt. Breuil’s documentation of these images provided striking archaeological and visual evidence for the agent of Upper Palaeolithic hunting magic, ‘scientific proof of a prehistoric shaman’s existence’ (

Tomášková 2013, p. 184): a master of animals, an antlered shaman-artist, recalling indeed, Witsen’s engraving, of 250 years earlier. But while Breuil identified the antlered figure in Les Trois Frères as ‘a shaman in ceremonial dress, or in the moment of shapeshifting’ (according to

Willerslev 2011, p. 521), his reproductions (

Breuil 1952) are not entirely reliable: the antlered sorcerer in particular certainly embellished upon the original, making the hybrid human-animal elements more pronounced (

Ucko and Rosenfeld 1967, p. 206), more shamanistic.

As an ordained Catholic priest, feted as ‘the Pope of prehistory’, Breuil looked like the antithesis to the materialists but, as

Tomášková (

2013, p. 166) argues, he ‘[g]ot around … speaking about the question of spirituality indirectly [by] focussing on art, creativity and magic … side-stepping the question of religion altogether [and] redefining spirituality as a domain of human creativity and imagination’. But far from an innovation, I think Breuil’s concept of spirituality entangled with creativity actually builds on earlier thinking on shamanism and art. Breuil was just the latest in a long line of distinguished thinkers—Vasari, Kant, Hegel, Herder, Reinach—to reify the metanarrative of spirituality as a domain of human creativity and imagination, with shamanism as its origin, and cave art—or at least that of ‘primitive’ people, Herder’s ‘cave dwellers’—as the earliest form of its visual expression. This is not to say that all these thinkers thought in the same way—of course they, and the terms art and shamanism which they used, were historically and socially situated. While the performing artist had been identified hitherto as the shaman of European civilisation, cave art offered visual, material evidence for the great antiquity of the relationship between shamanism and the visual arts.

The authentication of cave art at the turn of the twentieth century, then, provided archaeological evidence which lent empirical, chronological weight to the idea that shamanism and art have ancient, universal origins. The presumed affinity between shamanism and art was applied to Upper Palaeolithic cave art during the first half of this century, reifying the metanarrative of spirituality as the domain of human creativity and imagination, with shamanism as its origin, and cave art as the earliest form of its visual expression. This metanarrative is challenged by the fact that there is no singular cave art tradition (

Ucko and Rosenfeld 1967). None the less, cave art stands as the primary visual example of how art and shamanism have become entangled, and the iteration of their relationship as axiomatic, setting the precedent for the shamanistic interpretation of art across cultures over the following decades.

Breuil’s image of the antlered sorcerer has since been reproduced so often that, despite controversy over the accuracy of the recording, and being severed from its original context of the cave itself, this sorcerer has become the iconic prehistoric shaman-artist. The 1960 edition of Margaret Murray’s influential yet discredited book, The God of the Witches (first published in 1931), for instance, has a striking reproduction of the antlered sorcerer on the cover. Prior to this, Breuil’s ‘flute-playing’ sorcerer from Les Trois Frères graced the cover of the 1952 edition, in bold red on black. Murray used these images and other evidence to argue for a witch cult existing unbroken but at times hidden from the authorities (during the Late Medieval witch trials, for instance) from prehistory to the present. This sort of thinking and the way it is packaged suggests that cave art evidences the earliest religion, whether it is labelled ‘witchcraft’, ‘hunting magic’ or ‘shamanism’, and by implication that the earliest artists were shamans—and indeed that this legacy persisted over thousands of years.

Championed for thirty years from the start of the twentieth century by Reinach, Breuil and Bégouën, the shaman-artist interface gained new fervour after the discovery of Lascaux in 1940. The art itself is in stunning polychrome and includes both paintings and engravings; though not unique in this respect (e.g., Font-de-Gaume) the spectacular scale of the work, particularly the ‘Hall of the Bulls’, astonished visitors. The images in the shaft, known as the Lascaux ‘shaft scene’, while less technically accomplished are particularly famous because of the unique depiction in black pigment (painted and sprayed manganese dioxide) of a human stick-figure next to a bison apparently wounded by a projectile. Breuil visited Lascaux a week after its discovery to see this graphic and explicit representation of ‘hunting magic’ incorporating a bird-headed shaman beside an eviscerated large game animal. Writing in the 1950s, Bataille (1897–1962) states that no other cave art imagery could ‘provoke the same extreme awe as the discovery of Lascaux … [T]hese paintings have the force to dazzle, even to the point of disturbing us’ (

Bataille 2005, p. 59).

Kendall (

2005, p. 14) says that for Bataille, Lascaux must ‘stand in for the whole of prehistory’, this iconic site epitomising cave art as its metonym.

Smith (

2004) argues persuasively that the cave became a post-war ‘symbol of the twin births of art and homo sapiens’. There is older cave art and the idea that art is peculiar to humans is much-debated, but none the less, Lascaux swiftly became synonymous with the origin of art and the origin of religion (e.g.,

Bataille 1955).

8. Lascaux and the Origins of Art and Religion

This idea of cave art being shamanistic, and Lascaux specifically as the origins of art, explodes in the 1950s in a series of publications treating (the origins of) shamanism and (the origins of) art (see

Hoppál 1998). The decade’s fascination with art and shamanism was initiated by Gombrich’s

The Story of Art (1950), ‘one of the most famous and popular books on art ever written [and] a world bestseller for over four decades’ (uk.phaidon.com), having sold over six million copies. Revised and updated for its sixteenth edition (2007), this highly readable book is none the less problematic for its metanarrative of a singular and Eurocentric ‘story of art’ (

Dowson 1998). The opening chapter of Gombrich’s

Story is entitled ‘Strange Beginnings’, drawing attention to the apparent mysterious quality of the material and situating cave art as the origins of art: ‘We do not know how art began any more than we know how language started…The further we go back into history, the more definite but also the more strange are the aims which art was supposed to serve’ (

Gombrich [1950] 2007, p. 39). He goes on to briefly set out an interpretation of this material in terms of hunting magic:

The most likely explanation of these finds is that they are the oldest relics of that universal belief in the power of picture-making: in other words, that these primitive hunters thought that if they only made a picture of their prey—and perhaps belaboured it with their spears or stone axes—the real animals would also succumb to their power.

In The Story of Art, Gombrich reproduced the earlier thinking of Reinach, Breuil and Bégouën but, significantly, brought this thinking to a much wider readership.

A year after Gombrich’s volume, Andreas Lommel’s book

Shamanism: The Beginnings of Art (1951) was published. It is worth pausing to highlight the title of Lommel’s book which rammed home the idea of shamanism as the origin of art. Lommel offers a shamanistic interpretation of the Lascaux shaft-scene, positing a psychotic episode as necessary for the shaman’s creativity as an artist. Here, Lommel introduced a new trope of the shaman into the interpretation of cave art and the artist-shaman more broadly, that of the psychotic, mentally ill shaman or suffering visionary artist. The origin of this thinking in the twentieth century (without looking earlier to Diderot’s eighteenth century shamans as irrational and hypersensitive) stretches back to Mari Czaplicka’s

Aboriginal Siberia (1914) where the English-Polish scholar interprets Siberian shamans’ harrowing initiatory experiences (based on a synthesis of ethnographic works from the Russian-American Jesup North Pacific Anthropological Expedition, 1897–1902) as a form of ‘arctic hysteria’ or mental illness. Then in the 1930s, John

Layard (

1930) interpreted the experiences of ritual specialists known as ‘flying tricksters’ in Malakula (Melanesia) as that of epileptic shamans. And while in his

Psychomental Complex of the Tungus of (

Shirokogoroff 1935), Sergei Shirokogoroff revised the by then prevalent notion that shamans are psychotic, but rather accomplish mastery of their initiatory sickness and control the altered consciousness they engage with, the anthropological notion of shamans as mentally ill individuals on the fringes of society endured. A key example is Alfred Kroeber’s dismissive account, ‘Psychotic Factors in Shamanism’, published in the journal

Character and Personality in 1940, and George Devereux’s ‘Shamans as Neurotics’ (1961) and Julian Silverman’s, ‘Shamans and Acute Schizophrenia’ (1967) were both published in the influential journal

American Anthropologist (for full discussion of the scholarship on shamanism as a form of mental illness, see

Noll 1983;

Mitrani 1992).

There is a long history of reading shamans as either psychotics (

Czaplicka 1914;

Layard 1930;

Kroeber 1940;

Devereux 1961;

Silverman 1967) or psychotherapists (e.g.,

Murphy 1964;

Jilek 1971;

Calestro 1972;

Peters 1982;

Downton 1989;

Groesbeck 1989) in medical anthropology, and these too have been absorbed into thinking on artists as shamans, for example Michael Levy’s proposal in

Shamanism and the Modern Artist: Technicians of Ecstasy that ‘the shaman gets relief from his neurotic condition … in artistic expression’ and that ‘the “call” in shamanism is related to the artistic process’ (

Levy 1993, pp. xv–xvi). Of course, there is nothing new in this characterisation of artists and shamans—as I have discussed, Diderot had already defined the artist as irrational in the character Lui, antonym to Mois, the rational individual. But to generalise shamanism and art as Levy does, specifically to integrate the vague notion of ‘artistic expression’ with that of the ‘shaman’s call’ and an apparent ‘neurosis’, without evidence and as self-evident, is problematic.

A year after Lommel’s

Shamanism: The Beginnings of Art, Hörst Kirchner’s article ‘Ein archäologischer Beitrag zur Urgeschischte des Schamanismus’ (An archaeological contribution to the early history of shamanism), published in

Anthropos (

Kirchner 1952), takes a slightly different tack from Lommel, moving away from the idea of the shaman as mentally ill. He identifies the ‘stricken shaman’ of Lascaux, the ‘horned shaman’ of Les Trois Frères, and the Lascaux shaft-scene as a fight between two shamans, or between a shaman and a malevolent spirit (especially pp. 254, 260).

Drawing on Kirchner’s thinking in his book

The Rock Pictures of Europe (1956), Herbert Kühn proposes:

It is not impossible that we may have here represented some sort of shamanistic incantation…the wizard sinking into a trance and, then, experiences in his dream the killing of a beast. The bird upon the pole might be symbolic of the ghostly change in the wizard’s state. Horst Kirchner has remarked, in this connection, that certain Siberian tribes, to this day, expect their shaman to fall into a trance before the hunt begins and a bird may be the symbol of shamanistic power.

In this way of thinking, shamans are not mentally ill but, rather, accomplished in using trance to facilitate visionary experiences. As such, for Kühn, cave art is an expression of religious thinking:

When, in the Ice Age, Man painted beasts, when he represented a sorcerer, when he sought out caverns and remote and dark recesses, he was moved by what we must call religious urges…Only prehistory and prehistoric art can show us what was the real course of the development of religion’.

This thinking culminates in the work of Mircea Eliade, most notably his book

Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. While first published in French in 1951, the book had worldwide impact when translated into English and published by heavyweight Princeton University Press in 1964. Eliade defined shamanism as an archaic technique of ecstasy, which despite its vagueness he took to be the ‘least hazardous’ definition. In the 1964 book he also writes about shamanism as the origin of religion, points to Kirchner’s interpretation of the Lascaux shaft-scene as shamanistic, and identifies Lascaux as the origin of art, in a series of robust statements.

[The] role of the cave in paleolithic religions appears to have been decidedly important … [a symbol] of passage into another world, of a descent to the underworld’.

The bird perched on a stick is a frequent symbol in shamanic circles… already found in the celebrated relief at Lascaux (bird-headed man) in which Horst Kirchner has seen a representation of a shamanic trance.

Recent researches have clearly brought out the “shamanic” elements in the religion of the paleolithic hunters. Horst Kirchner has interpreted the celebrated relief at Lascaux as a representation of a shamanic trance.

Eliade’s view has been echoed by many influential thinkers on shamanism since, coalescing around what Feng Qu identifies as the ‘Palaeolithic substratum theory’ (

Qu 2017, p. 499). For Åke Hultkrantz (e.g.,

Hultkrantz 1973), for instance, ‘shamanism was once represented among Paleolithic hunters’ (

Hultkrantz 1989, p. 52), an idea extended into the Americas in the work of Peter Furst (e.g.,

Furst 1973) who proposed that Mesoamerican and Siberian societies share a common archaic religious system (

Qu 2017, pp. 518–19). Furst was by no means the first to suggest that Old World shamanism diffused into the Americas at an early date, however. The American folklorist Charles Godfrey Leland proposed in in the 1870s and 1880s that shamanism was the ‘world’s first religion’ (

Znamenski 2004, p. xxviii). This long-established view that shamanism is universal is repeated by Lucy Lippard in her book sub-titled ‘contemporary art and the art of prehistory’, in which she proposes that there is ‘a universal shamanic tradition going back to Paleolithic times’ (

Lippard 1983, p. 68).

This thinking was also adopted by K. C. Chang in his discussion of shamanism in China. In an important recent article, Feng Qu explores how Chang applied Eliade’s idea of a ‘Palaeolithic substratum’ for shamanism as well as a ‘Maya-Chinese continuum’ which ‘can be traced back into the Upper Paleolithic of the Old World’ (

Qu 2017, p. 526). Chang points specifically to the example of the bird in the Lascaux shaft scene as a common symbol ‘in both Chinese and Maya art more than 10,000 years later’ (

Chang 1992, p. 219), citing Joseph Campbell as an authority on the matter, who thought that the bird-man in the shaft ‘is certainly a shaman’:

Down there [in The Shaft] a large bison bull, eviscerated by a spear that has transfixed its anus and emerged through its sexual organ, stands before a prostrate man. The latter (the only crudely drawn figure, and the only human figure in the cave) is rapt in a shamanistic trance. He wears a bird mask; his phallus, erect, is pointing at the pierced bull; a throwing stick lies on the ground at his feet; and beside him stands a wand or staff, bearing on its tip the image of a bird. And then, behind this prostrate shaman, is a large rhinoceros, apparently defecating as it walks away

Drawing on Campbell’s work, Chang writes:

The earliest evidence of [shamanism] is found, according to him, not in Mesoamerica, Northeast Asia or China, but on the walls of the caves at Lascaux, perhaps 15,000 years ago, where we find, “supine with out-flung arms, a man—with an erect phallus and what would appear to be a bird’s head—or perhaps he is wearing a mask. His hands are also bird-like, and there is the figure of a bird perched upon a vertical staff at his right. As birds are ‘the normal vehicles of wizard-flights in ecstasy’, and ‘bird-decorated costumes and staves, as well as bird transformations, are the rule in shamanistic contexts’, Campbell believed that ‘the prostrate figure [is] a shaman, rapt in trance’.

Chang sums up how Campbell, like Eliade and others, ‘traced crucial elements of shamanistic mythology throughout the world [and] back to the Paleolithic hunters’ (

Chang 1992, p. 219). In these accounts, then, from Leland to Lommel and Eliade, and from Campbell and Furst to Chang, shamanism is perceived as a universal phenomenon across time, culture and media, from prehistoric Europe to the ethnographic present, from Siberia to the Americas. And cave art, specifically Lascaux, is presented as the origin of both religion and art.

As a historian of religion and philosopher interested in consistencies in religious practice over the long durée, Eliade might be forgiven for over-generalising a Siberian term and making it global, for ignoring the polyvalency of cave art, its specific archaeological contexts and localised variety, and for fetishising Lascaux as the ‘origin’ of art and ‘origin’ of shamanism. But as

Znamenski reminds us (

2003, p. n.6), Eliade did, after all, bring shamanism to serious scholarly attention, on a par with the ‘world religions’. None the less, Eliade’s construction of shamanism tells us as much if not more about mid-twentieth century thinking on the subject than about prehistoric art and indigenous shamans themselves. His book remains highly influential, the classic go-to book on shamanism which has remained in print since the first English edition. Reprinted with a new foreword in 2007, the book is top in the Amazon rankings under the search ‘shamanism’. Despite critical engagement with his ideas (summarised in

Znamenski 2007, pp. 187–188), Eliade is, ultimately, the main source upon which subsequent writers on the subject have gained their understanding of ‘shamanism’, particularly in non-anthropological literature engaging with shamanism and art (e.g.,

Tucker 1992;

Levy 1993). In popular, neo-shamanic literature (for full discussion see

Wallis 2003), for instance, Felicitas

Goodman (

1990) claims via a ‘psychological archaeology’ to have unlocked codes to shamanic trance postures, recorded in various images in prehistoric and indigenous art. By adopting the posture of ‘the Lascaux shaman’, for example, practitioners are able to ‘step from the physical change of the trance to the experience of ecstasy’ (

Goodman 1990, p. 23; see also

Goodman 1986).

‘Shamanism’ has been used as a dumping bag for a wide variety of ritualistic, religious and artistic practices, and used so loosely that it can refer to almost any ritual specialist and almost any form of artistic inspiration. And the Lascaux shaft scene has been singled out as representing the archetypal prehistoric shaman. The visual elements in the ‘scene’ are frequently simplified in photographic and other reproductions, the rhino cropped-out (the horse on the wall opposite ignored altogether), in order to promote a shamanistic reading. Such reproductions also flatten out the cave wall, neglect the context of the shaft itself, ignore the archaeological context (such as the sandstone lamp at the bottom of the shaft). In short, a monolithic concept of shamanism and art instantiates cave art as handmaiden to cognitive evolution (

Dowson 1998).

9. Conclusions

In this paper, I have examined how art and shamanism have been conceived and then entangled in various ways from the Renaissance to the present. ‘Art’ was iterated as a special category discrete from craft by Vasari, the ‘father’ of art history, and the first Siberian shaman was recorded by a European, Englishman Richard Johnson, during Vasari’s lifetime. The terms ‘art’ and ‘shamanism’ were crystallised during the eighteenth century, and the two converged, particularly in the work of Diderot who conceived of the performing artist as the shaman of European civilisation. Recognition of the deep antiquity of humankind and discoveries of Upper Palaeolithic cave art in the nineteenth century offered the visual and material evidence for the prehistory of an art-shamanism interface, and enabled the co-opting of shamanism into the visual arts. The authentification of cave art and identification of ‘sorcerers’ in some of the caves by Breuil and others then led such thinkers as Lommel and Eliade to single out Lascaux as the origins of art and shamans as the first artists.

Cave art has been cited consistently and problematically as the origins of art and shamanism, from Breuil’s sorcerers in Les Trois Frères and Lascaux, to Whitley’s recent proposal that mental illness, the ‘shaman’s disease’ links shamanism, creativity and the painted caves (

Whitley 2009, p. 220); reproducing the stereotype set out by

Czaplicka (

1914),

Devereux (

1961) and others that shamans experience mental illness (challenged by

Noll 1983;

Mitrani 1992). And while cave art is much-peddled as the origins of art and shamanism, this preoccupation with ‘origins’ arguably tells us more about modern thinking than it does about the cave artists themselves. One prevalent hypothesis has been to see cave art as part of a ‘creative explosion’ (

Spivey 2005, pp. 20–24) during an ‘Upper Paleolithic Revolution’ (

Whitley 2009, p. 26; see also e.g.,

McClennon 2001;

Hayden 2003, p. 131). According to Whitley, ‘only anatomically modern humans, not Neanderthals, made cave art’ (

Whitley 2009, p. 26), and ‘religion’ itself is ‘developed first (in so far as we currently can tell) in western Europe, at least thirty-five thousand years ago’ (

Whitley 2009, p. 207), formalised at the time that cave art was made. But this can be challenged as a cognicentric and Eurocentric narrative which neglects earlier artistic production outside of Europe (e.g.,

Aubert et al. 2014;

Henshilwood et al. 2018), and the possibility that ‘art’ was made by Neanderthals (e.g.,

Rodríguez-Vidal et al. 2014;

Hoffmann et al. 2018; but see

Aubert et al. 2018). As

Ingold (

2018, pp. 40–41) argues:

[I]t is claimed that paintings preserved on the walls of caves, dating to around 30,000 years ago, reveal a capacity for art that culminated in the European Renaissance, that stone tools of the same period and provenance reveal a capacity for technology that has reached its peak with the microchip, that the people who made the paintings and the tools had the capacity to be a Newton or an Einstein. But this decidedly Eurocentric vision, popularly rendered as the ‘ascent of man’, casts aside the accomplishments of those whose histories happen not to fall in with the modern myth of progress …. Human nature, then, serves as little more than a prop to support the belief in our own superiority.

Shamanism can be understood as part of ‘a conceptual field’, along with such notions as magic and witchcraft, ‘made to define an antithesis of modernity: a production of illusion and delusion that was thought to recede and disappear as rationalization and secularization spread throughout society’ (

Pels 2003, p. 4). It is, as Ronald Hutton points out, something against which the West defined itself (

Hutton 2001, p. viii). But at the same time shamanism has been co-opted into western imagination. Just as the West has sought to distance itself from shamanism, so it has also aimed to accommodate it, consume it even, and make it its own—shamanism, along with magic and witchcraft, ‘is in modernity’ (

Pels 2003, p. 3). The archaeologist Jaquetta Hawkes famously proposed that ‘every age has the Stonehenge it deserves—or desires’ (

Hawkes 1967, p. 174). Similarly, each new generation reinvents the shaman-artist for themselves—from Diderot’s hypersensitive Lui, and Breuil’s sorcerers in Les Trois Frères and Lascaux, to Wassily Kandinsky (

Weiss 1995), Joseph Beuys (e.g.,

Antliff 2014), Nam June Paik (

Cheon 2009), Marcus Coates (

Walters 2010) and many other contemporary artists (see

Wallis 2004,

2012,

forthcoming). We get the shaman-artist ‘we deserve’, for each new decade.

The 1980s–1990s brought shamanism to bear on cave art in a new way, applying ethnographic analogy and neuropsychology to propose that some cave art imagery is derived from shamanistic visions—the key work is David Lewis-Williams and Thomas Dowson’s ‘The Signs of All Times: Entoptic Phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic Art’ published in

Current Anthropology (

Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988) in the same year as Campbell’s

The Power of Myth television series. And in the 2000s, the ‘new animism’ and ontological turn in archaeology and anthropology have situated shaman-artists as mediators between human and other-than-human communities (e.g.,

Dowson 2007,

2009). In the 2010s, recent work re-evaluating contemporary artists as shamans and proposing a ‘theoretical model’ with a list of ‘necessary properties must all be fulfilled for an individual to qualify as a shaman’ (

Benycheck 2014, p. 225), Benycheck none the less reifies the ‘Palaeolithic substratum’ myth, proposing that ‘the earliest known indications of shamanic art’ Benycheck 2014, p. 211) emerge in the Paleolithic with the gender-skewed assertion, based on a selective reading of archaeological evidence, that women were ‘the earliest shamans and artists’ (

Benycheck 2014, p. 215).

While I do not have space to treat each of these more recent interpretations of shamanistic cave artists, and contemporary shaman-artists in detail, nor to argue whether cave art is shamanistic or not, to state that art and shamanism are discursive terms is not to say that certain indigenous and prehistoric arts cannot be argued to have been made by shamans, or that certain contemporary artists have not drawn upon shamanism in their work in creative ways of interest to anthropologists and archaeologists. In previous work, I have approached the Lascaux shaft scene as depicting a human-hybrid ‘shaman’ among a number of other-than-human persons, situated within a wider-than-human animic world (

Wallis 2013a,

2013b). And the work of certain contemporary artists who have been labelled shamans may contribute creatively to how we understand shamanism anthropologically and archaeologically (e.g.,

Wallis 2004,

forthcoming;

Harvey and Wallis 2016). I aim to engage critically with these manifestations of the art-shaman interface from the 1980s to the present in a future article.

In the current essay, in conclusion, I have demonstrated that while art and shamanism have been presented as immutable and bound together, from prehistory, as the origins of religion and art, to the present, with modern artists as the inheritors of this enduring tradition of shamanic art, they are constructed, discursive terms based variously around problematic concepts of hypersensitivity, neurosis, individual genius, divine inspiration and transcendental artistic creativity, operating outside of social norms. Whether proposed or presumed, the convergence of art and shamanism, from cave painting to the white cube of the contemporary gallery, is a modern myth which requires critical re-visioning in order to move beyond simplistic metanarratives, paying close attention to the complexities of anthropological and archaeological data and specific social and historic contexts in order to recognise diversity and difference. Art and shamanism do not have an elective affinity, but a critical discourse analysis of the way in which they have become entangled in Western thought indicates that they are, to paraphrase

Levi-Strauss (

[1962] 1966) ‘good to think with’.