Seaweeds, Intact and Processed, as a Valuable Component of Poultry Feeds

Abstract

1. Introduction

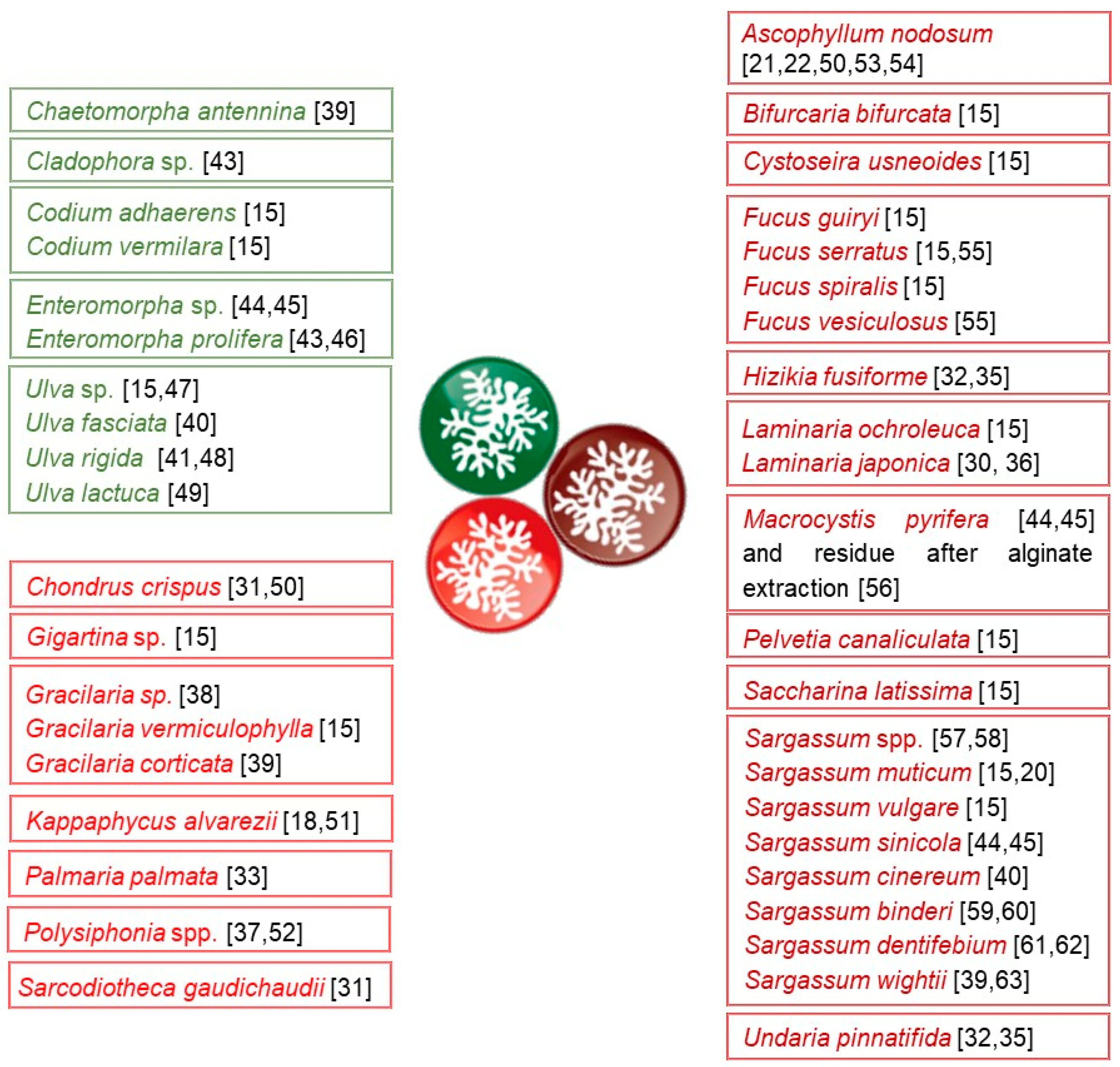

2. Seaweeds Biologically Active Compounds Important in Poultry Nutrition

3. Forms of Seaweeds in Poultry Feed

4. Enrichment of Poultry Products with Algal Biologically Active Compounds

5. Quality of Food Derived from Poultry Feed with Seaweeds

5.1. Egg Quality

5.2. Carcass Characteristics and Meat Quality

6. Effect of Seaweeds on Poultry Growth and Productive Performance

6.1. Growth Performance

6.2. Egg Production Performance and Hatchability

7. Effect of Seaweeds on Poultry Health

8. Effect of Seaweeds on Blood Profile

9. Advantages and Disadvantages of Seaweeds in Poultry Nutrition and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahaotu, E.O.; De los Ríos, P.; Ibe, L.C.; Singh, R.R. Climate change in poultry production system—A review. Acta Sci. Agric. 2019, 3, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Livestock and Poultry: World Markets and Trade. Foreign Agricultural Service, USA. 2020. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/livestock_poultry.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- El-Hack, M.E.A.; Mahrose, K.M.; Askar, A.A.; Alagawany, M.; Arif, M.; Saeed, M.; Abbasi, F.; Soomro, R.N.; Siyal, F.A.; Chaudhry, M.T. Single and combined impacts of vitamin A and selenium in diet on productive performance, egg quality, and some blood parameters of laying hens during hot season. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2016, 177, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, M.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; Arif, M.; El-Hindawy, M.M.; Attia, A.I.; Mahrose, K.M.; Bashir, I.; Siyal, F.A.; Arain, M.A.; Fazlani, S.A.; et al. Impacts of distiller’s dried grains with solubles as replacement of soybean meal plus vitamin E supplementation on production, egg quality and blood chemistry of laying hens. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2017, 17, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhagen, S.; Klemm, R. Implementing small-scale poultry-for-nutrition projects: Successes and lessons learned. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daghir, N.J. Poultry Production in Hot Climates, 6th ed.; Cromwell Press: Trowbridge, UK, 1995; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alagawany, M.; Mahrose, K.M. Influence of different levels of certain essential amino acids on the performance, egg quality criteria and economics of Lohmann Brown laying hens. Asian J. Poult. Sci. 2014, 8, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Farghly, M.F.A.; Mahrose, K.M.; Galal, A.E.; Ali, R.M.; Ahmad, E.A.M.; Rehman, Z.U.; Ullah, Z.; Ding, C. Implementation of different feed withdrawal times and water temperatures in managing turkeys during heat stress. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 3076–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghly, M.F.A.; Mahrose, K.M.; Cooper, R.; Ullah, Z.; Rehman, Z.U.; Ding, C. Sustainable floor type for managing turkey production in a hot climate. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 3884–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hack, M.E.A.; Mahrose, K.M.; Attia, F.A.M.; Swelum, A.A.; Taha, A.E.; Shewita, R.; Hussein, E.-S.O.S.; Alowaimer, A.N. Laying performance, physical, and internal egg quality criteria of hens fed distillers dried grains with solubles and exogenous enzyme mixture. Animals 2019, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Kassem, D.E.; Ashour, E.A.; Alagawany, M.; Mahrose, K.M.; Rehman, Z.U.; Ding, C. Effect of feed form and dietary protein level on growth performance and carcass characteristics of growing geese. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrose, K.M.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; Mahgoub, S.A.; Attia, F.A.M. Influences of stocking density and dietary probiotic supplementation on growing Japanese quail performance. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2019, 91, e20180616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrose, K.M.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; Amer, S.A. Influences of dietary crude protein and stocking density on growth performance and body measurements of ostrich chicks. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2019, 91, e20180479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, Y.S.; Fahim, H.N.; Beshara, M.M.; Mahrose, K.M.; Awad, A.L. Response of duck breeders to dietary L-Carnitine supplementation during summer season. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2019, 91, e20180907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrita, A.R.J.; Maia, M.; Oliveira, H.M.; Pinto, I.S.; Almeida, A.; Pinto, E.; Fonseca, A.J.M. Tracing seaweeds as mineral sources for farm-animals. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 3135–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdt, S.L.; Kraan, S. Bioactive compounds in seaweed: Functional food applications and legislation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 543–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, I.; Chojnacka, K. Algae as production systems of bioactive compounds. Eng. Life Sci. 2015, 15, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, S.S.N.; Biswas, A.; Mandal, A.B.; Kumawat, M.; Saxena, R.; Nasir, A.M. Production performance, immune response and carcass traits of broiler chickens fed diet incorporated with Kappaphycus Alvarezii. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 31, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øverland, M.; Mydland, L.T.; Skrede, A. Marine macroalgae as sources of protein and bioactive compounds in feed for monogastric animals. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 99, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erum, T.; Frias, G.G.; Cocal, C.J. Sargassum muticum as feed substitute for broiler. Asia Pacific. J. Educ. Arts Sci. 2017, 4, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, F.; Critchley, A.T. Seaweeds for animal production use. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.; Tran, G.; Heuzé, V.; Giger-Reverdin, S.; Lessire, M.; LeBas, F.; Ankers, P. Seaweeds for livestock diets: A review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 212, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corino, C.; Modina, S.; Di Giancamillo, A.; Chiapparini, S.; Rossi, R. Seaweeds in pig nutrition. Animals 2019, 9, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalak, I.; Marycz, K. Algae as a promising feed additive for horses. In Seaweeds as Plant Fertilizer, Agricultural Biostimulants and Animal Fodder; Pereira, L., Bahcevandziev, K., Joshi, N.H., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; Volume 7, pp. 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, T.; Inácio, A.; Coutinho, T.; Ministro, M.; Cotas, J.; Pereira, L.; Bahcevandziev, K. Seaweed potential in the animal feed: A review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberecht, S.; Wilkinson, S.; Roberts, J.; Wu, S.-B.; Swick, R. Unlocking the potential health and growth benefits of macroscopic algae for poultry. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2018, 74, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshreshtha, G.; Hincke, M.T.; Prithiviraj, B.; Critchley, A.T. A Review of the varied uses of macroalgae as dietary supplements in selected poultry with special reference to laying hen and broiler chickens. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.L.; Guo, Y.M.; Yuan, J.M.; Liu, D.; Zhang, B.K. Sodium alginate oligosaccharides from brown algae inhibit Salmonella Enteritidis colonization in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiseman, M. Evaluation of Tasco® as a Candidate Prebiotic in Broiler Chickens; Dalhousie University: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2012; Available online: https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/14443/Wiseman_Melissa_MSc.__Animal_Science_February_2012.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 April 2020).

- Islam, M.M.; Ahmed, S.T.; Mun, H.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Yang, C.J. Effect of Sea Tangle (Laminaria japonica) and charcoal supplementation as alternatives to antibiotics on growth performance and meat quality of ducks. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 27, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshreshtha, G.; Rathgeber, B.; Stratton, G.; Thomas, N.; Evans, F.; Critchley, A.T.; Hafting, J.; Prithiviraj, B. Feed supplementation with red seaweeds, Chondrus crispus and Sarcodiotheca gaudichaudii, affects performance, egg quality, and gut microbiota of layer hens. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 2991–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Lee, S.R.; Oh, J.-W. Effects of dietary fermented seaweed and seaweed fusiforme on growth performance, carcass parameters and immunoglobulin concentration in broiler chicks. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 27, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.H. Effects of Red Seaweed (Palmaria Palmata) Supplemented Diets Fed to Broiler Chickens Raised under Normal or Stressed Conditions; Dalhousie University: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2015; Available online: https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/64662/Karimi–Seyed_Hossein–MSc–September_21.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Kulshreshtha, G.; Rathgeber, B.; MacIsaac, J.; Boulianne, M.; Brigitte, L.; Stratton, G.; Thomas, N.A.; Critchley, A.T.; Hafting, J.; Prithiviraj, B. Feed supplementation with red seaweeds, Chondrus crispus and Sarcodiotheca gaudichaudii, reduce Salmonella Enteritidis in laying hens. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, E.; Na, Y.; Lee, S. Effects of dietary supplementation with fermented and non-fermented brown algae by-products on laying performance, egg quality, and blood profile in laying hens. Asian-Australasian J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1654–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Wang, R.; Yan, L.; Feng, J. Co-Supplementation of dietary seaweed powder and antibacterial peptides improves broiler growth performance and immune function. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2019, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Deekx, A.; Bri, A.M.; Brikaa, A.M. Effect of different levels of seaweed in starter and finisher diets in pellet and mash form on performance and carcass quality of ducks. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2009, 8, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasiska, N.; Suprijatna, E.; Susanti, S. Effect of diet containing Gracilaria sp. waste and multi-enzyme additives on blood lipid profile of local duck. Anim. Prod. 2016, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Karu, P.; Selvan, S.; Gopi, H.; Manobhavan, M. Effect of macroalgae supplementation on growth performance of Japanese quails. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 1039–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeweil, S.H.; Abu Hafsa, S.H.; Zahran, S.M.; Ahmed, M.S.; Abdel–Rahman, N. Effects of dietary supplementation with green and brown seaweeds on laying performance, egg quality, and blood lipid profile and antioxidant capacity in laying Japanese quail. Egypt. Poult. Sci. J. 2019, 39, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ventura, M.; Castañon, J.; McNab, J. Nutritional value of seaweed (Ulva rigida) for poultry. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 1994, 49, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, I.; Chojnacka, K. Multielemental analysis of macroalgae from the Baltic Sea by ICP-OES to monitor environmental pollution and assess their potential uses. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2009, 89, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, I.; Chojnacka, K.; Dobrzański, Z.; Górecki, H.; Zielińska, A.; Korczyński, M.; Opaliński, S. Effect of macroalgae enriched with microelements on egg quality parameters and mineral content of eggs, eggshell, blood, feathers and droppings. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2010, 95, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Dominguez, S.; López, E.; Casas, M.M.; Avila, E.; Castillo, R.M.; Carranco, M.E.; Calvo, C.; Pérez-Gil, F. Potential use of seaweeds in the laying hen ration to improve the quality of n-3 fatty acid enriched eggs. J. Appl. Phycol. 2008, 20, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Dominguez, S.; Ríos, V.H.; Calvo, C.; Carranco, M.E.; Casas, M.; Pérez-Gil, F. n-3 fatty acid content in eggs laid by hens fed with marine algae and sardine oil and stored at different times and temperatures. J. Appl. Phycol. 2012, 24, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hui, J.Y.; Hua, W.L.; Hua, Z.F.; Ting, L.Y. Enteromorpha prolifera supplemental level: Effects on laying performance, egg quality, immune function and microflora in feces of laying hens. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2013, 25, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Luo, J.; Wang, C.; Tai, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, K.; Jia, Y.; Lyv, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Ulvan extracted from green seaweeds as new natural additives in diets for laying hens. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 2017–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañedo-Castro, B.; Piñón-Gimate, A.; Carrillo, S.; Ramos, D.; Casas-Valdez, M. Prebiotic effect of Ulva rigida meal on the intestinal integrity and serum cholesterol and triglyceride content in broilers. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 3265–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudabos, A.M.; Okab, A.B.; Aljumaah, R.; Samara, E.; Abdoun, K.A.; Al-Haidary, A.A. Nutritional value of green seaweed (Ulva lactuca) for broiler chickens. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupart, C.M. Supplementation of Red Seaweed (Chondrus crispus) and Tasco® (Ascophyllum nodosum) in Laying Hen Diets; Dalhousie University: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://dalspace.library.dal.ca/bitstream/handle/10222/76824/Stupart–Cassandra–MSc–AGRI–December–2019.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 April 2020).

- Mandal, A.B.; Biswas, A.; Mir, N.A.; Tyagi, P.K.; Kapil, D.; Biswas, A.K. Effects of dietary supplementation of Kappaphycus alvarezii on productive performance and egg quality traits of laying hens. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 2065–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Deek, A.; Brikaa, M.A. Nutritional and biological evaluation of marine seaweed as a feedstuff and as a pellet binder in poultry diet. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2009, 8, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naga, M.A.; Megahed, M. Impact of brown algae supplementation in drinking water on growth performance and intestine histological changes of broiler chicks. Egypt. J. Nutr. Feed. 2018, 21, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bonos, E.; Kargopoulos, A.; Nikolakakis, I.; Florou-Paneri, P.; Christaki, E. The seaweed Ascophyllum nodosum as a potential functional ingredient in chicken nutrition. J. Oceanogr. Mar. Res. 2017, 4, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, A.; Herstad, O.; Liaaen-Jensen, S. Fucoxanthin metabolites in egg yolks of laying hens. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 1998, 119, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón, U.; Carrillo, S.; Arellano, L.G.; Casas, M.M.; Pérez, F.; Avila, E. Chemical composition of the residue of alginates (Macrocystis pyrifera) extraction. Its utilization in laying hens feeding. Cuban J. Agricult. Sci. 2003, 37, 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, S.; Bahena, A.; Casas, M.; Carranco, M.E.; Calvo, C.C.; Ávila, E.; Pérez–Gi, F. The alga Sargassum spp. as alternative to reduce egg cholesterol content. Cuban J. Agricult. Sci. 2012, 46, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- El–Deek, A.A.; Al–Harthi, M.A. Nutritive value of treated brown marine algae in pullet and laying diets. World Poultry Science Association. In Proceedings of the 19th European Symposium on Quality of Poultry Meat, 13th European Symposium on the Quality of Eggs and Egg Products, Turku, Finland, 21–25 June 2009; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, Y.L.; Yuniza, A.; Nuraini; Sayuti, K.; Mahata, M.E. Immersion of Sargassum binderi seaweed in river water flow to lower salt content before use as feed for laying hens. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2017, 17, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, Y.L.; Yuniza, A.; Sayuti, K.; Mahata, M.E.; Nuraini, N. Fermentation of Sargassum binderi seaweed for lowering alginate content of feed in laying hens. J. World’s Poult. Res. 2019, 9, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al–Harthi, M.A.; El–Deek, A.A. Nutrient profiles of brown marine algae (Sargassum dentifebium) as affected by different processing methods for chickens. J. Food Agricult. Environ. 2012, 10, 475–480. [Google Scholar]

- El–Deek, A.A.; Al–Harthi, M.A.; Abdalla, A.A.; Elbanoby, M.M. The use of brown algae meal in finisher broiler diets. Egypt. Poult. Sci. 2011, 31, 767–781. [Google Scholar]

- Athis Kumar, K. Effect of Sargassum wightii on growth, carcass and serum qualities of broiler chickens. Vet. Sci. Res. 2018, 3, 000156. [Google Scholar]

- Fleurence, J. Seaweed proteins: Biochemical, nutritional aspects and potential uses. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1999, 10, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herber-McNeill, S.M.; Van Elswyk, M.E. Dietary marine algae maintains egg consumer acceptability while enhancing yolk color. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Esquerra, R.; Leeson, S. Alternatives for enrichment of eggs and chicken meat with omega-3 fatty acids. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 81, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stengel, D.B.; Connan, S.; Popper, Z.A. Algal chemodiversity and bioactivity: Sources of natural variability and implications for commercial application. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajauria, G. Seaweeds: A sustainable feed source for livestock and aquaculture. Seaweed Sustain. 2015, 389–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahaye, M.; Vigouroux, J. Liquefaction of dulse (Palmaria palmata (L.) Kuntze) by a commercial enzyme preparation and purified endo–β–1,4–d–xylanase. J. Appl. Phycol. 1992, 4, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harthi, M.A.; El-Deek, A.A. Effect of different dietary concentrations of brown marine algae (Sargassum dentifebium) prepared by different methods on plasma and yolk lipid profiles, yolk total carotene and lutein plus zeaxanthin of laying hens. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 11, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.V. Marine Algal Constituents; Barrow, C., Shahidi, F., Eds.; Marine Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 259–296. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid, P.B.; Aisha, K.; Ali, A. Green seaweed as component of poultry feed. Bangladesh J. Bot. 1995, 24, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Charoensiddhi, S.; Abraham, R.E.; Su, P.; Zhang, W. Seaweed and seaweed-derived metabolites as prebiotics. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 91, 97–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Beatty, E.R.; Wang, X.; Cummings, J.H. Selective stimulation of bifidobacteria in the human colon by oligofructose and inulin. Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Song, H.L.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, Y.; Qi, R.; Lin, Y.T. Effects of different dietary levels of Enteromorpha prolifera on nutrient availability and digestive enzyme activities of broiler chickens. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2010, 22, 1658–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Herber, S.M.; Van Elswyk, M.E. Dietary marine algae promotes efficient deposition of n-3 fatty acids for the production of enriched shell eggs. Poult. Sci. 1996, 75, 1501–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. Human requirement for n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Poult. Sci. 2000, 79, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fats and Fatty Acids in Human Nutrition. Report of an Expert Consultation; FAO Food and Nutrition: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, H.; Sheng, J. The antihyperlipidemic mechanism of high sulfate content ulvan in rats. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 3407–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, Y.S.; Ismail, I.I.; Abu Hafsa, S.H.; Eshera, A.A.; Tawfeek, F.A. Effect of dietary green tea and dried seaweed on productive and physiological performance of laying hens during late phase of production. Egypt. Poult. Sci. 2017, 37, 685–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harthi, M.A.; El-Deek, A.A. The effects of preparing methods and enzyme supplementation on the utilization of brown marine algae (Sargassum dentifebium) meal in the diet of laying hens. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, E.J.; Wilkinson, S.J.; Cronin, G.M.; Walk, C.L.; Cowieson, A.J. The effect of marine calcium source on broiler leg integrity. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Australian Poultry Science Symposium, Sydney, Australia, 19–22 February 2012; pp. 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zahid, P.B.; Ali, A.; Zahid, M.J. Brown seaweeds as supplement for broiler feed. Hamdard Med. 2001, 44, 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, T.S.; Im, J.T.; Park, I.K.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, D.Y.; Choi, C.J.; Lee, H.G.; Choi, Y.J. Effect of dietary brown seaweed levels on the protein and energy metabolism in broiler chicks activated acute phase response. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. (Kor.) 2005, 47, 379–390. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Memon, M.S. Incorporation of Enteromorpha procera Ahlner as nutrition supplement in chick’s feed. Int. J. Biol. Biotechnol. 2008, 5, 211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Aisha, K.; Zahid, P.B. Brown seaweeds as supplementary feed for poultry. Int. J. Phycol. Phycochem. 2009, 5, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Shi, X.; Zhou, C.; Lin, Y. Entermorpha prolifera: Effects on performance, carcass quality and small intestinal digestive enzyme activities of broilers. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2013, 25, 1332–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Y.; Ayala, L.; Hurtado, C.; Más, D.; Rodríguez, R. Effects of dietary supplementation with red algae powder (Chondrus crispus) on growth performance, carcass traits, lymphoid organ weights and intestinal pH in broilers. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2019, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bratova, K.; Ganovski, K. Effect of Black Sea algae on chicken egg production and on chick embryo development. Vet. Med. Nauki. 1982, 19, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Vidanarachchi, J.; Mikkelsen, L.L.; Sims, I.; Iji, P.A.; Choct, M. Phytobiotics: Alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters in monogastric animal feeds. Rec. Adv. Anim. Nutr. Aust. 2005, 15, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, A.; Moghadamtousi, S.Z.; Abubakar, S.; Zandi, K. Antiviral potential of algae polysaccharides isolated from marine sources: A review. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizondo-Gonzalez, R.; Cruz-Suárez, L.E.; Marie, D.R.; Mendoza-Gamboa, E.; Rodriguez-Padilla, C.; Trejo-Ávila, L.M. In vitro characterization of the antiviral activity of fucoidan from Cladosiphon okamuranus against Newcastle Disease Virus. Virol. J. 2012, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siahaan, E.A.; Pendleton, P.; Woo, H.-C.; Chun, B.-S. Brown seaweed (Saccharina japonica) as an edible natural delivery matrix for allyl isothiocyanate inhibiting food-borne bacteria. Food Chem. 2014, 152, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulovich, R.; Umanzor, S.; Cabrera, R.; Mata, R. Tropical seaweeds for human food, their cultivation and its effect on biodiversity enrichment. Aquaculture 2015, 436, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.G.; Sweeney, T.; Bahar, B.; Lynch, B.P.; O’Doherty, J.V. Effect of maternal fish oil and seaweed extract supplementation on colostrum and milk composition, humoral immune response, and performance of suckled piglets. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 2988–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wahab, A.A.; Visscher, C.; Kamphues, J. Impact of different dietary protein sources on performance, litter quality and foot pad dermatitis in broilers. J. Anim. Feed. Sci. 2018, 27, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, N.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, Z. The structure of a sulfated galactan from Porphyra haitanensis and its in vivo antioxidant activity. Carbohydr. Res. 2004, 339, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.; Makkar, H.P.; Becker, K. Antinutritional factors present in plant-derived alternate fish feed ingredients and their effects in fish. Aquaculture 2001, 199, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert, G.; Ducatelle, R.; Van Immerseel, F. An update on alternatives to antimicrobial growth promoters for broilers. Veter. J. 2011, 187, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschmann, A.H.; Camus, C.; Infante, J.; Neori, A.; Israel, A.; Hernández-González, M.C.; Pereda, S.V.; Pinchetti, J.L.G.; Golberg, A.; Tadmor-Shalev, N.; et al. Seaweed production: Overview of the global state of exploitation, farming and emerging research activity. Eur. J. Phycol. 2017, 52, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Burg, S.; Stuiver, M.; Veenstra, F.; Bikker, P.; López Contreras, A.; Palstra, A.; Broeze, J.; Jansen, H.; Jak, R.; Gerritsen, A.; et al. A Triple P Review of the Feasibility of Sustainable Offshore Seaweed Production in the North. Sea; Wageningen UR (University & Research Centre): Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| (a) Brown Seaweeds | ||||||||||

| Form/Inclusion Level | Poultry/Age/ Duration of Experiment | Egg Weight | Yolk Color | Albumen Height | Haugh Unit | Shell Thickness | Shell Weight | Shell Strength | Egg-Shape Index | Ref. |

| Macrocystis pyrifera, sun-dried and ground; 10% of algae + 2% of sardine oil | Leghorn hens, 35 weeks old, 8-week study | ↓ 3.4% | ↑ 6.9% | ↑ 14% | ↑ 8.4% | ↓ 7.4% | ↓ 9.1% | n.a. | n.a. | [44] |

| Post-extraction residue from Macrocystis pyrifera (after alginate extraction); 5% | Leghorn hens, 23 weeks old, 3-week study | ↑ 1.1% | ↑ 44% | ↑ 5.1% | ↑ 0.4% | ↑ 3.4% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [56] |

| Sargassum sinicola, sun-dried and ground; 10% of algae + 2% of sardine oil | Leghorn hens, 35 weeks old, 8-week study | ↓ 0.5% | ↓ 6.9% | ↑ 1.5% | ↑ 0.5% | ↓ 0.5% | ↓ 2.8% | n.a. | n.a. | [44] |

| Sargassum dentifebium, sun-dried (S); boiled (B) and autoclaved (A) (dried before feeding); 3% and 6% | Hy-Line laying hens, 23 weeks old, 19-week study | n.a. | ↑ S: 3%–11%, 6%–4.8%; B: 3%–4.8%, 6%–9.7%; A: 3%–0.9%, 6%–16% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [70] |

| Sargassum dentifebium, sun-dried (S); boiled (B) and autoclaved (A) (dried before feeding); 3% and 6% | Hy-Line laying hens, 23 weeks old, 19-week study | ↑S: 3%–0.2%, 6%–1.0%; ↓B: 3%–1.5%, 6%–3.3%; ↑A: 3%–1.1%, 6%–0.8% | S: 3%↓–2.4%, 6%↑–6.1%; ↑B: 3%–5.5%, 6%–12%; ↑A: 3%–4.3%, 6%–12% | n.a. | ↑S: 3%–0.2%, 6%–2.6%; ↑B: 3%–1.8%, 6%–0.7%; ↑A: 3%–0.7%, 6%–1.3% | S: 3%↑–3.3%, 6%↓–2.6%; ↑B: 3%–9.2%, 6%–1.2%; ↑A: 3%–0.5%, 6%–3.3% | n.a. | n.a. | S: 3%↑–0.1%, 6%↓–1.7%; ↓B: 3%–0.9%, 6%–1.7%; A: 3%↓–1.4%, 6%↑–2.0% | [81] |

| Sargassum cinereum, sun-dried and ground; 1.5% and 3% | Laying Japanese quail hens, 10 weeks old, 14-week study | ↑ 1.5%–3.9%; 3%–3.0% | ↑ 1.5%–23.1%; 3%–23.1% | n.a. | ↓ 1.5%–2.5%; 3%–3.1% | ↑ 1.5%–4.6%; 3%–5.1% | ↓ 1.5%–2.8%; 3%–2.9% | n.a. | ↑ 1.5%–3.2%; 3%–1.6% | [40] |

| Sargassum spp., dried and ground; 2%, 4%, 6% and 8% | Leghorn hens, 19 weeks old, 5-week study | ↓ 2%–1.4%; 4%–2.1%; 6%–0.5%; 8%–2.4% | ↑ 2%–3.8%; 4%–4.9%; 6%–9.5%; 8%–12% | ↓2%–0.8%; 4%–1.7%; 6%–3.2%; 8%–1.8% | ↓ 2%–0.2%; 4%–0.1%; 6%–1.2%; 8%–0.2% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [57] |

| Sargassum spp. sun–dried (S); boiled (B) and autoclaved (A) (dried before feeding); 0%, 3%, 6%, 9% and 12% | Lohman laying hens, 23 weeks old, 19-week study | n.a. | ↑ * | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [58] |

| Fucus serratus and F. vesiculosus, dried at 40 °C and ground; 15% | White Leghorn laying hens, 24 weeks old, 4-week study | n.a. | ↑ 12–15 times more carotenoids | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [55] |

| Undaria pinnatifida, 0.5% of seaweed (S) and fermented seaweed (FS) | Hy–Line Brown laying hens, 70 weeks old, 4-week study | S: ↑2%; FS: ↓0.8% | ↓ S: 1.4%; FS: 1.4% | n.a. | ↓ S: 0.5%; FS: 0.5% | S: ↓25%; FS:–n.c. | n.a. | ↓ S: 4.5%; FS: 4.5% | n.a. | [35] |

| Hizikia fusiforme, 0.5% of seaweed (S) and fermented seaweed (FS) | Hy–Line Brown laying hens, 70 weeks old, 4-week study | S: ↑1.4%; FS: ↓0.3% | ↓ S: 1.4%; FS: 1.4% | n.a. | ↓ S: 1.8%; FS: 5.4% | S:–n.c.; FS: ↓25% | n.a. | ↓ S: 4.5%; FS: 4.5% | n.a. | [35] |

| Ascophyllum nodosum (Tasco®), sun–dried and ground; 0.25% and 0.5% | Lohmann LSL Brown, 34 weeks old, 3-week study | ↑0.25%–1.1%; ↓0.5%– 1.7% | n.a. | ↑ 0.25%–2.6%; 0.5%–4.6% | n.a. | ↓ 0.25%–0.9%; 0.5%–1.4% | ↑0.25%–0.5%; ↓0.5%–2.8% | n.a. | n.a. | [50] |

| Brown seaweeds (species not defined), dried, 0.1% and 0.2% | Sinai hens, 52 weeks old, 12-week study | ↓ 0.1%–4.1%; 0.2%–4.0% | ↓0.1%–5.1%; 0.2%–n.c. | n.a. | ↓ 0.1%–1.4%; 0.2%–5.4% | ↓ 0.1%–16%; 0.2%–7.8% | n.a. | n.a. | 0.1%–n.c; ↓0.2%–1.7% | [80] |

| (b) Green seaweeds | ||||||||||

| Form/Inclusion Level | Poultry/Age/ Duration of Experiment | Egg Weight | Yolk Color | Albumen Height | Haugh Unit | Shell Thickness | Shell Weight | Shell Strength | Egg–Shape Index | Ref. |

| Enteromorpha spp., sun–dried and ground, 10% of algae + 2% of sardine oil | Leghorn hens, 35 weeks old, 8-week study | ↓ 1.4% | ↓ 19% | ↓ 12% | ↓ 9.3% | ↓ 1.6% | ↓ 3.6% | n.a. | n.a. | [44] |

| Enteromorpha prolifera, 1%, 2% and 3% | Highland brown laying hens, 42 weeks old, 4-week study | ↑ 1%–8.7%; 2%–6.0%; 3%–8.1% | ↑ 1%–19%; 2%–18%; 3%–25% | n.a. | n.a. | ↑ 1%–2.9%; 2%–2.9%; 3%–5.7% | n.a. | n.a. | ↑ 1%–0.8%; 2%–n.c.; 3%–n.c. | [46] |

| Ulvan from Ulva sp., 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.5%, 0.8% and 1% | Hy–Line Brown hens, 61 weeks old, 8-week study | ↓0.05%–0.9%; ↑0.1%–0.7%; ↓0.5%–0.1%; ↓0.8%–0.2%; ↓1%–1.2% | ↑ * | ↓ * | ↓ * | n.a. | n.a. | ↑ * | ↓ * | [47] |

| Ulva fasciata, sun–dried and ground; 1.5% and 3% | Laying Japanese quail hens 10 weeks old, 14-week study | ↑ 1.5%–3.9%; 3%–2.6% | ↑ 1.5%–35%; 3%–46% | n.a. | ↓ 1.5%–2.3%; 3%–2.3% | ↑ 1.5%–3.5%; 3%–4.1% | ↓ 1.5%–2.8%; 3%–1.2% | n.a. | ↑ 1.5%–2.5%; 3%–0.9% | [40] |

| Green seaweeds (species not defined), dried, 0.1% and 0.2% | Sinai hens, 52 weeks old, 12-week study | ↑ 0.1%–4.4%; 0.2%–0.9% | ↓0.1%–5.1%; 0.2%–n.c. | n.a. | ↓ 0.1%–2.7%; 0.2%–5.4% | ↓ 0.1%–9.9%; 0.2%–16% | n.a. | n.a. | ↑ 0.1%–1.8%; 0.2%–0.9% | [80] |

| Enteromorpha prolifera and Cladophora sp. enriched with microelements (S)– Cu, Mn, Zn, Co, Cr | Lohmann brown laying hens, 30–45 weeks old, 5-week study | ↑ S–Cu–3.1%; S–Mn–5.7%; S–Zn–2.0%; S–Co–8.7%; S–Cr–1.6% | ↑ * | n.a. | n.a. | ↑ S–Cu–10%; S–Mn–14%; S–Zn–6.9%; S–Co–7.4%; S–Cr–5.4% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [43] |

| (c) Red Seaweeds | ||||||||||

| Form/Inclusion Level | Poultry/Age/ Duration of Experiment | Egg Weight | Yolk Color | Albumen Height | Haugh Unit | Shell Thickness | Shell Weight | Shell Strength | Egg–Shape Index | Ref. |

| Red seaweeds (species not defined); dried, 0.1% and 0.2% | Sinai hens, 52 weeks old, 12-week study | ↑0.1%–1.2%; ↓0.2%–7.7% | ↓ 0.1%–5.1%; 0.2%–5.1% | n.a. | ↓0.1%–6.4%; 0.2%–n.c. | ↓ 0.1%–9.0%; 0.2%–7.8% | n.a. | n.a. | ↑ 0.1%–0.5%; 0.2%–0.5% | [80] |

| Chondrus crispus, raw ground (G: 4%) and extruded, dried and reground (E: 1%, 2%, 3% and 4%) | Lohmann Brown Lite laying hens, 70 weeks old, 3-week study | G: ↑4%–0.4%; E: ↓1%–1.6%; E: ↓2%–2.0%; E: ↑3%–1.1%; E: ↑4%–0.3% | n.a. | G: ↑4%–4.2%; E: ↑1%–6.9%; E: ↑2%–2.8%; E: ↑3%–8.3%; E: ↓4%–2.8% | n.a. | G: ↓4%–2.0%; E: 1%–; E: ↑2%–2.0%; E: 3%–; E: ↑4%–4.0% | G: ↓4%–0.2%; E: ↓1%–0.5%; E: ↓2%–0.8%; E: ↑3%–0.5%; E: ↑4%–2.9% | n.a. | n.a. | [50] |

| Kappaphycus alvarezii, powder; 1.25%, 1.50% and 1.75% | Laying hens, day–old, 40-week study | ↑ 1.25%–0.7%; 1.50%–3.8%; 1.75%–5.3% | ↓ 1.25%–10%; 1.50%–6.6%; 1.75%–12% | n.a. | ↑ 1.25%–0.6%; 1.50%–4.9%; 1.75%–5.3% | ↑ 1.25%–12%; 1.50%–9.1%; 1.75%–12% | n.a. | n.a. | ↑ 1.25%–0.3%; 1.50%–4.7%; 1.75%–5.2% | [51] |

| Marine macroalgae (not defined); 2.4% and 4.8% | Single Comb White Leghorn, 56 weeks old, 4-week study | n.a. | ↑ * | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [65] |

| Seaweeds | Poultry Species | Growth Performance Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final Body Weight | Body Weight Gain | Feed Intake | Mortality Rate | Ref. | ||

| Brown Seaweeds | ||||||

| Undaria pinnatifida, 0.5% of seaweed (S) and fermented seaweed (FS) | Broilers, one day old Ross male, 35-day study | ↑ (35 day) S–4.3%; FS–2.5% | ↑ (35 day) S–7.6%; FS–6.4% | (35 day) ↑S–2.4%; ↓FS–2.7% | ↓ S– ~4.5 times FS– ~9 times | [32] |

| Hizikia fusiformis, 0.5% of seaweed (S) and fermented seaweed (FS) | Broilers, one day old Ross male, 35-day study | ↑ (35 day) S–2.2%; FS–0.7% | ↑ (35 day) S–4.1%; FS–3.2% | ↓ (35 day) S–1.3%; FS–1.5% | ↓ S–3 times FS– ~9 times | [32] |

| Sargassum muticum, air dried under the shade and ground; 5%, 10%, 15% | Broilers, one day old, 39-day study | ↑ (39 day) 5%–23%; 10%– 25%; 15%–26% | ↑ (39 day) 5%–25%; 10%–27%; 15%–28% | ↑ (39 day) 5%–20%; 10%–14%; 15%–17% | n.a. | [20] |

| Sargassum wightii, dried under shade, then sun–dried and ground, powder; 1%, 2%, 3%, 4% | Broilers, one day old, 121-day study | ↑ 1%–88%; 2%–93%; 3%–93%; 4%–93% | ↑ 1%–99%; 2%–104%; 3%–104%; 4%–104% | ↑ 1%–53%; 2%–58%; 3%–58%; 4%–58% | n.a. | [63] |

| Sargassum wightii, dried; 3% | Japanese quail, one day old, 42-day study | ↓ (42 day) 3%–0.3% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [39] |

| Sargassum dentifebium, sun–dried; 2%, 4%, 6% | Broilers, 18 days old, 39-day study | ↓ (39 day) 2%–1.3%; 4%–2.7%; 6%–3.3% | ↓ (18–39 day) 2%–1.5%; 4%–3.7%; 6%–5.0% | ↑ (18–39 day) 2%–1.2%; 4%–2.5%; 6%–5.9% | n.a. | [62] |

| Laminaria japonica, commercial powder and charcoal; 0.1%, 0.5%, 1% | Duck, 22 days old, 21-day study | n.a. | (0–21 days) 0.1%–n.c.; 0.5%–n.c.; ↑1%–4.8% | ↓ (0–21 days) 0.1%–0.8%; 0.5%–2.7%; 1%–1.6% | n.a. | [30] |

| Laminaria japonica, commercial powder; 1% | Arbor Acres broilers, one day old, 42-day study | n.a. | ↑ 1%–2.7% | ↓ 1%–0.02% | n.a. | [36] |

| Red Seaweeds | ||||||

| Polysiphonia spp., dried; 1.5%, 3% | Hubbard duck, 14 days old, 56-day study | ↓ (56 day) 1.5%–1.3%; 3%–3.6% | ↓ 1.5%–1.3%; 3%–3.8% | ↓ 1.5%–1.7%; 3%–3.0% | n.a. | [52] |

| Gracilaria corticata, dried; 3% | Japanese quail, one day old, 42-day study | ↑ (42 day) 3%–0.05% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [39] |

| Kappaphycus alvarezii, 0.25%, 0.5%, 0.75%, 1%, 1.25%, 1.5% | Broilers, one day old, 42-day study | n.a. | ↑ (0–42 days) 0.25%–1.8%; 0.5%–2.4%; 0.75%–3.0%; 1%–2.9%; 1.25%–11%; 1.5%–9% | (0–42 days) ↑0.25%–1.3%; ↓0.5%–2.6%; ↓0.75%–1.4%; ↓1%–0.3%; ↑1.25%–4.8%; ↑1.5%–2.5% | n.a. | [18] |

| Palmaria palmata, dried, ground, commercial; 0.6%, 1.2%, 1.8%, 2.4%, 3% | Ross 308 broilers, one day old, 35-day study | (25–35 day) ↑0.6%–2.0%; ↑1.2%–1.0%; ↑1.8%–5.3%; ↓2.4%–1.7%; ↓3%–2.7% | (25–35 day) ↓0.6%–12%; ↓1.2%–9.5%; ↓1.8%–9.8%; ↓2.4%–3.6%; ↓3%–14% | (25–35 day) ↓0.6%–4.5%; ↓1.2%–0.1%; ↓1.8%–7.0%; ↓2.4%–8.1%; ↓3%–5.4% | (0–35 day) 0.6%–lack mortality; ↓1.2%–33%; 1.8%–lack mortality; ↓2.4%–67%; ↓3%–67% | [33] |

| Green Seaweeds | ||||||

| Ulva rigida, dried under shade, ground; 2%, 4%, 6% | Arbor Acres Broilers, one day old, 42-day study | (42 day) ↑2%–0.8%; ↓4%–5.5%; ↑6%–0.6% | n.a. | ↑ (42 day) 2%–1.9%; 4%–2.6%; 6%–4.6% | ↓ 2%–4 times; 4%–4 times; 6%–17% | [48] |

| Chetomorpha antennina, dried; 3% | Japanese quail, one day old, 42-day study | ↑ (42 day) 3%–0.1% | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | [39] |

| Ulva lactuca, sun–dried and then oven–dried, ground; 3%, 6% | Ross broilers, one day old, 33-day study | n.a. | (19–33 days) ↓3%–0.4%; ↑6%–2.3% | (19–33 days) ↓3%–0.9%; ↑6%–2.7% | n.a. | [49] |

| ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|

|

■ Effect on egg composition: − Increase in the n–3 fatty acids content in eggs [44] − Increase in the n–9 fatty acids content in eggs [70] − Improvement of the content of protein in egg [56] − Decrease in egg cholesterol and triglycerides [40,46,47,44,57,70,80] ■ Improvement of meat quality: − Lower fat content [20,49,53,83,87,88] − Higher content of protein [83] ■ Egg-laying rate and egg quality parameters: − Increase in laying rate [31,35,40,43,80] − Increase in the egg weight [40,43,46,51,56,81] − Increase in the yolk color [40,43,44,46,47,55,56,57,58,65,70,81] − Increase in the albumen height [44,56,50] − Increase in the Haugh unit [44,51,56,81] − Increase in the shell thickness [40,43,46,51,56,81] − Increase in egg–shape index [40,51,80] − Increase in eggshell strength [47] ■ Effect on blood profile: − Decrease in plasma cholesterol, LDL, VLDL and triglycerides [38,40,48,70,80] − Increase in enzymatic antioxidant activity [40,80] − Increase in lymphocyte number [36] − Decrease in sodium concentration [31] − Improvement of heterophils to lymphocytes ratio [80] ■ Improvement of growth performance: − Increase in body weight [20,30,32,43,62,63] − Increase in body weight gain [18,36] − Increase in feed intake [20,48,62] − Improving feed conversion ratio [20,30,32,48,63] − Decrease in mortality rate [32,48] ■ Improvement in fertility and hatchability: − Increase in fertility [40,89,90] − Increase in hatchability [40,89] ■ Can act as prebiotics [28,31,34,40,48] ■ Enhancement of immune functions and intestinal villi [18,32,34,35,37,48,80] ■ Boosting useful bacteria [31,34,36,93,94] |

■ Seaweeds polysaccharides can bind nutrients and inhibit their absorption in the gastrointestinal tract [60] ■ Seaweeds antinutrients can interfere with digestion and feed utilization processes [67,68,98] ■ Seaweeds can contain toxic metals [42,60,67,68] ■ High salt content in seaweeds can cause diarrhea and poultry death [59,72] ■ Seasonal and geographical variations in chemical composition of seaweeds [20,19,42,64,67] ■ Cultivation and processing methods and costs may impact the nutritional value of seaweeds [99,100,101] ■ The high foot pad dermatitis score was found in broilers fed algae meal [96] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Michalak, I.; Mahrose, K. Seaweeds, Intact and Processed, as a Valuable Component of Poultry Feeds. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse8080620

Michalak I, Mahrose K. Seaweeds, Intact and Processed, as a Valuable Component of Poultry Feeds. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2020; 8(8):620. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse8080620

Chicago/Turabian StyleMichalak, Izabela, and Khalid Mahrose. 2020. "Seaweeds, Intact and Processed, as a Valuable Component of Poultry Feeds" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 8, no. 8: 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse8080620

APA StyleMichalak, I., & Mahrose, K. (2020). Seaweeds, Intact and Processed, as a Valuable Component of Poultry Feeds. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 8(8), 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse8080620