An Improved ORB-KNN-Ratio Test Algorithm for Robust Underwater Image Stitching on Low-Cost Robotic Platforms

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- This paper presents a complete, lightweight, and robust underwater image stitching framework, specifically designed for underwater robotic platforms with stringent real-time constraints and limited computational resources.

- (2)

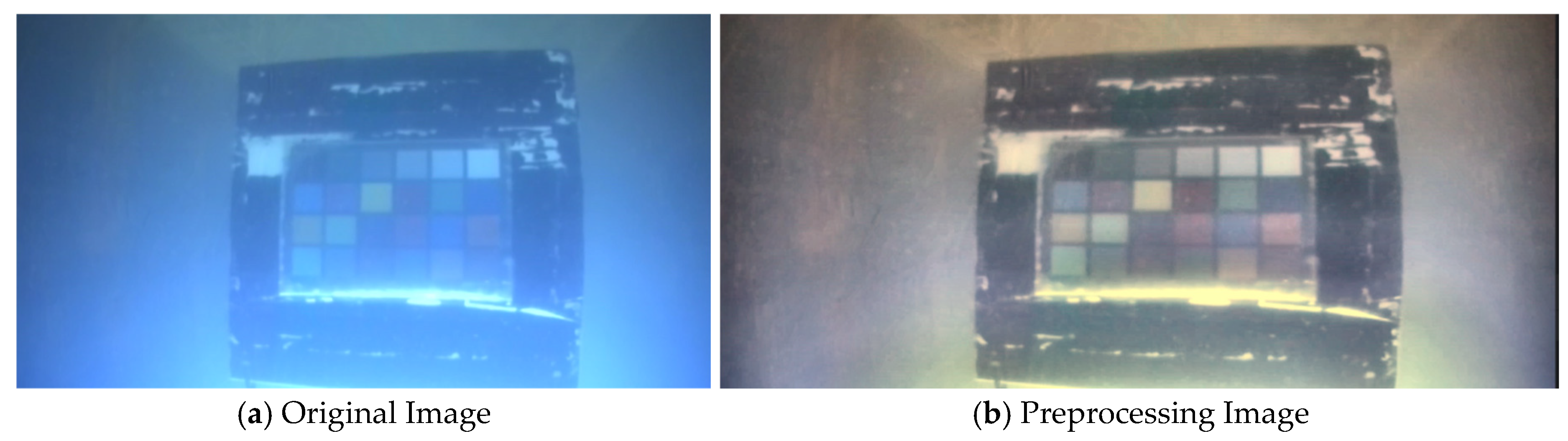

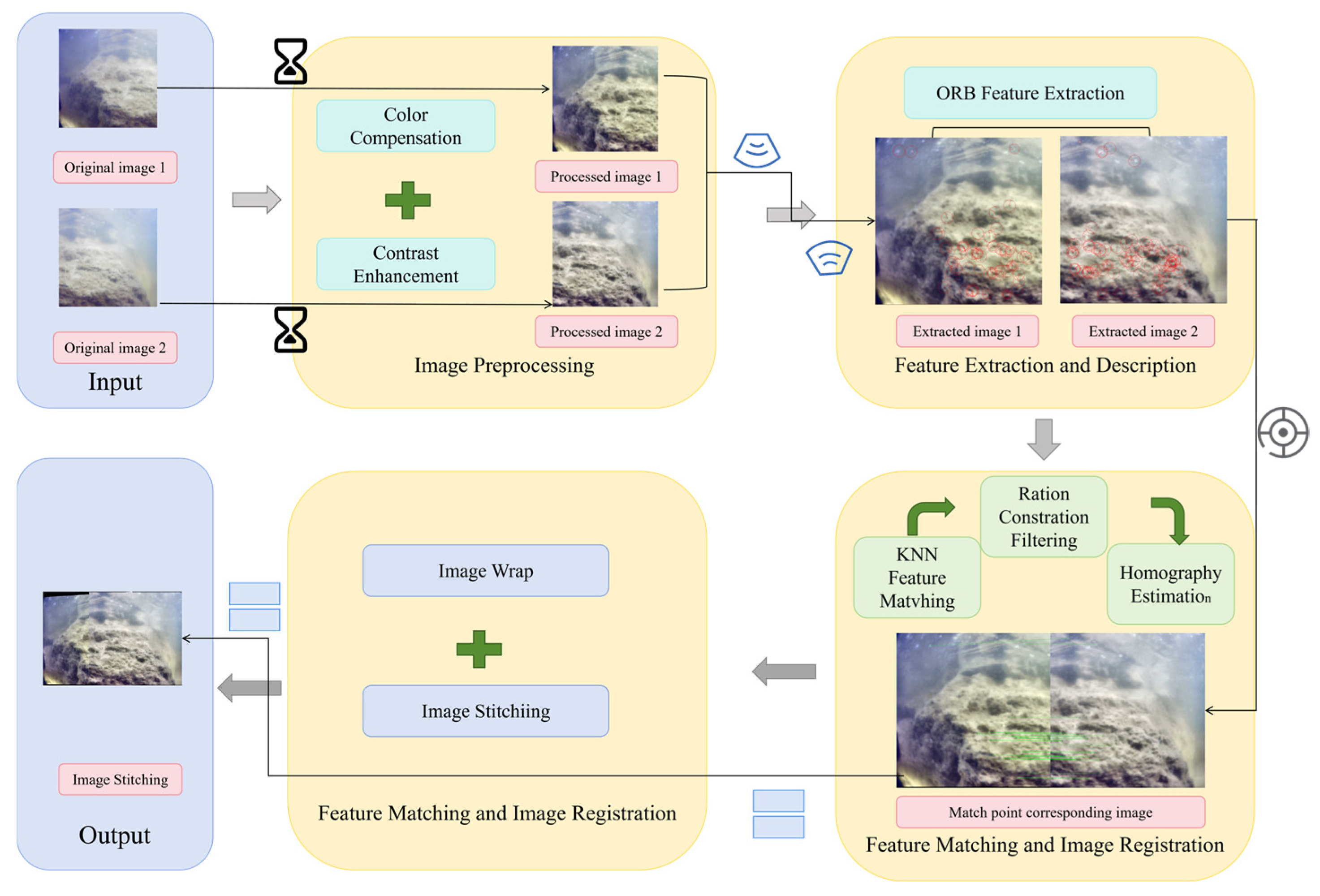

- An enhanced ORB-based feature matching strategy is proposed. A lightweight color and contrast enhancement scheme is first applied to improve feature detectability, followed by KNN-based matching with a ratio-test constraint to suppress false correspondences. Compared with the conventional ORB approach, the proposed strategy significantly increases the number of reliable feature points while improving robustness and matching accuracy.

- (3)

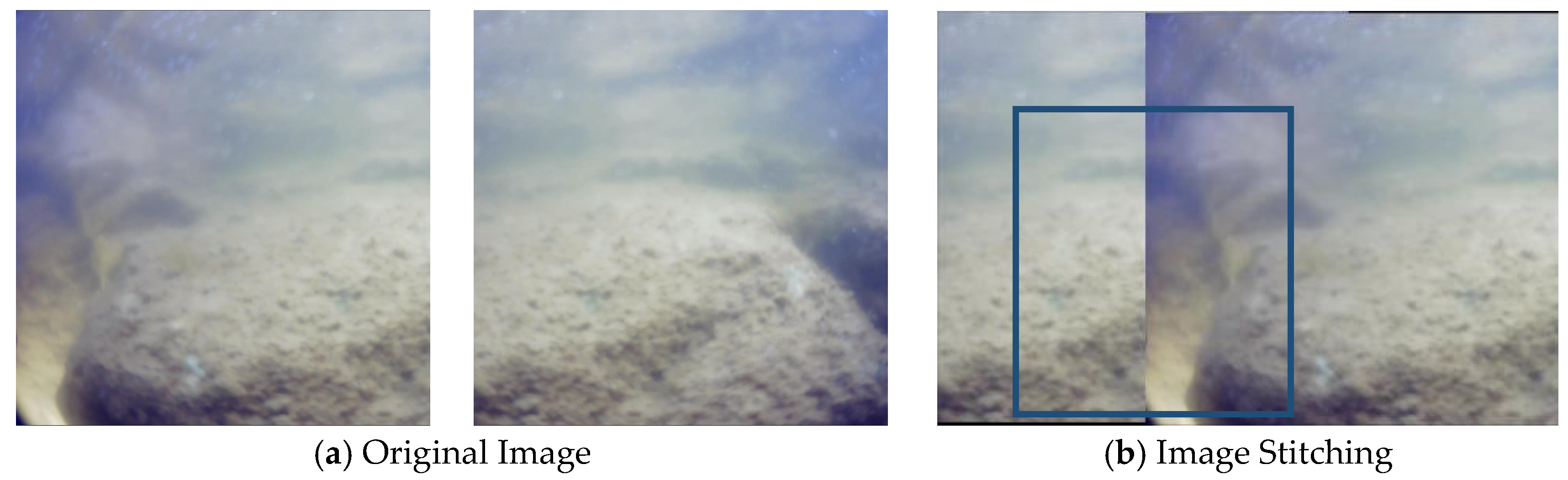

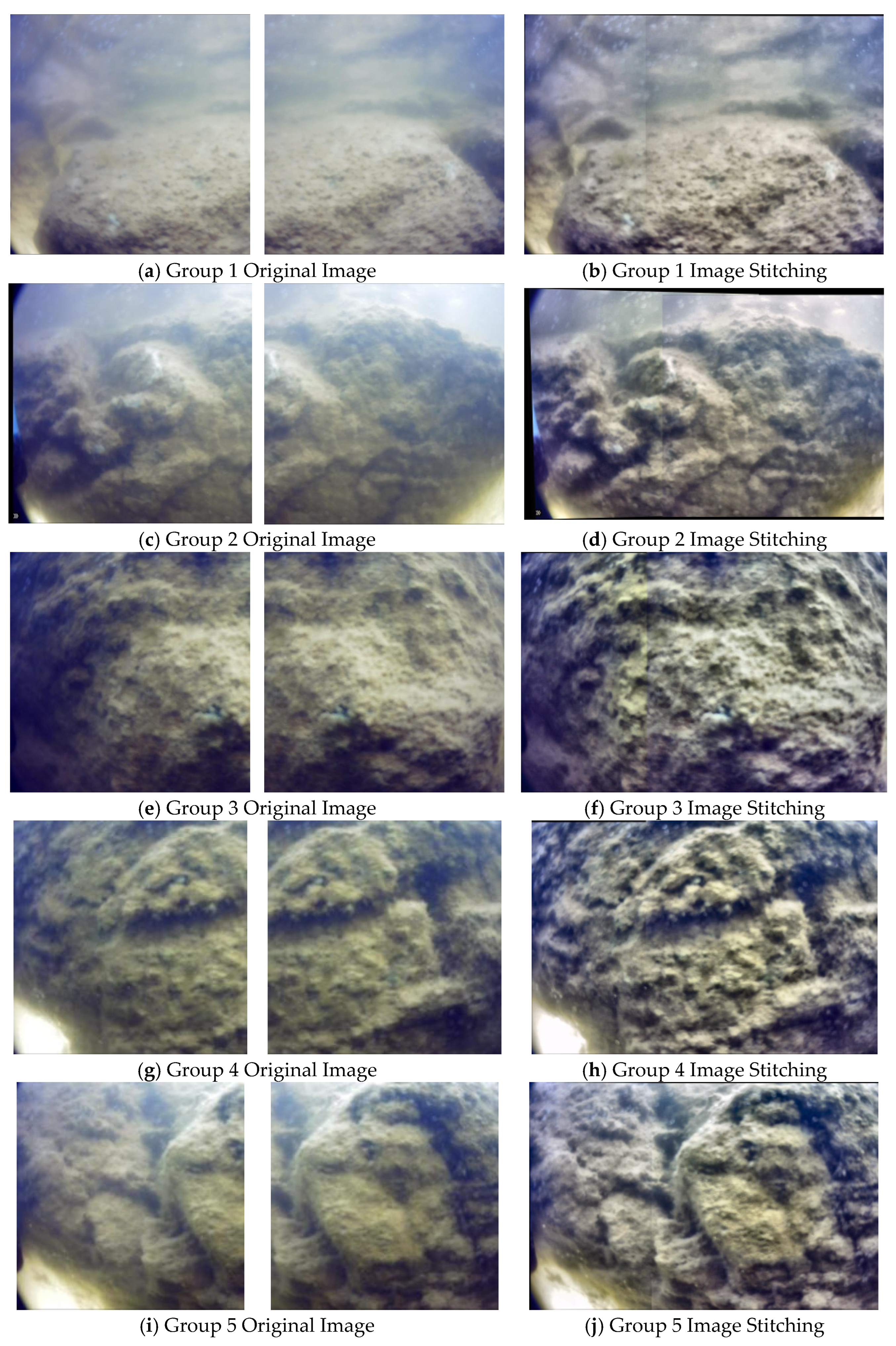

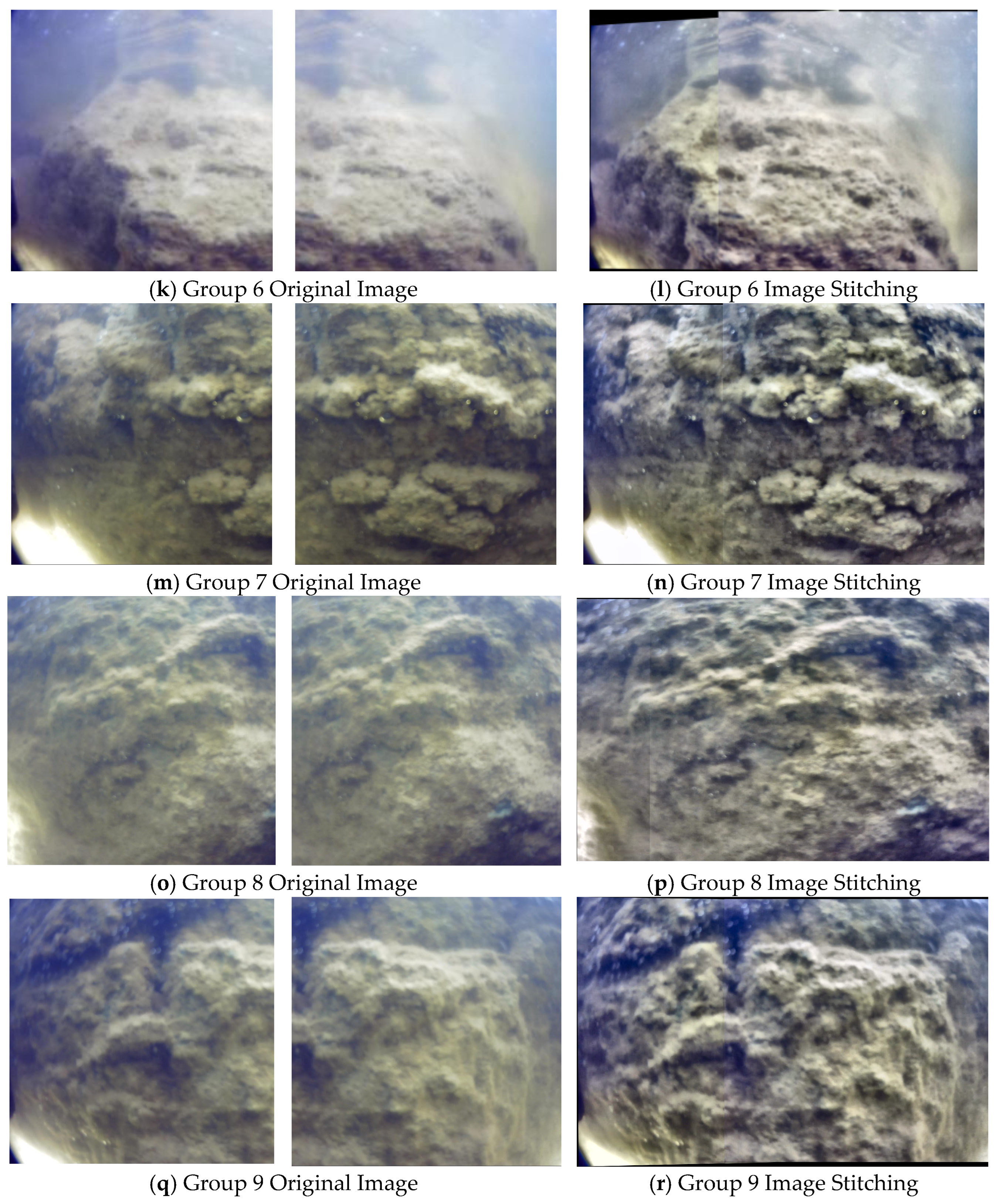

- A practical and reproducible underwater evaluation protocol is established and validated using real-world data collected from an underwater robotic platform. PSNR and SSIM are computed exclusively within overlapping regions, and a detailed runtime analysis is provided, demonstrating the effectiveness, real-time performance, and applicability of the proposed method in real underwater environments.

2. Related Works

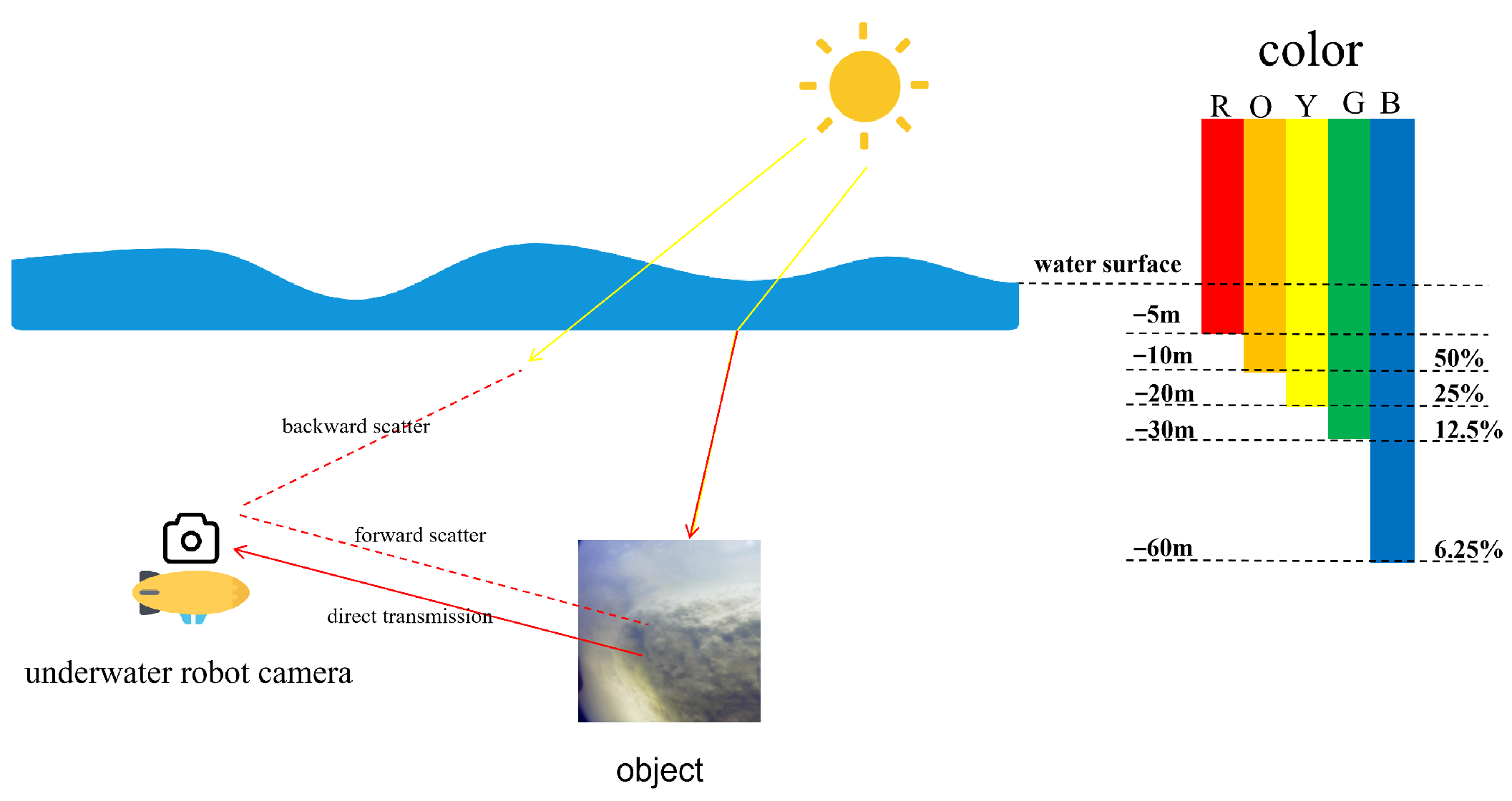

Problem Statement

3. Algorithm Introduction

3.1. Incremental Image Splicing Framework

3.2. ORB Algorithm Principle

3.2.1. o-FAST Corner Detection

3.2.2. r-BRIEF Feature Description

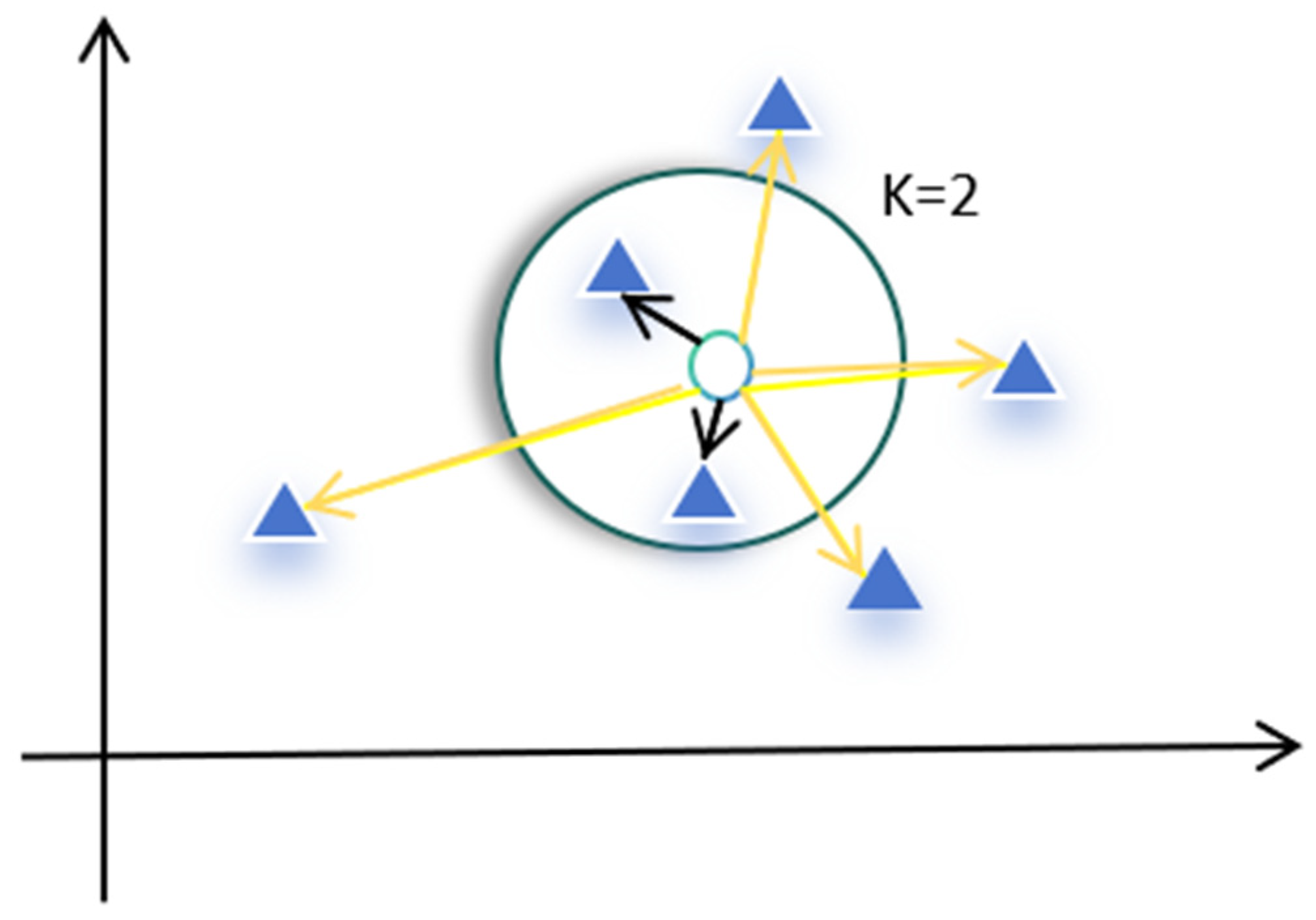

3.3. KNN Algorithm Principle

3.4. Ratio Test Principle

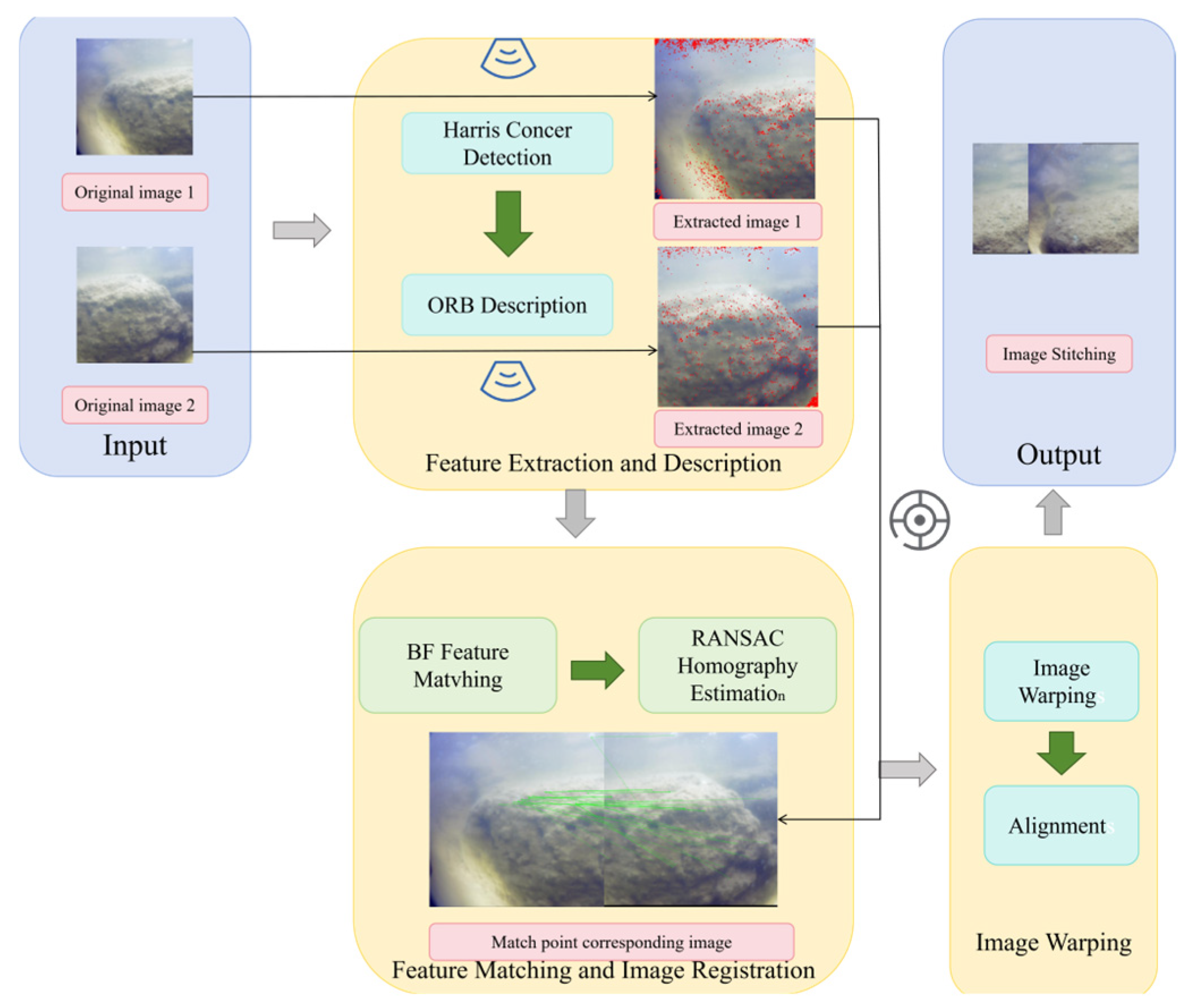

3.5. Algorithm Flow

3.5.1. Incremental Image Registration Algorithm Based on Feature Point Extraction

3.5.2. ORB-KNN-Ratio Test Image Splicing Algorithm

4. Experimental Results Analysis

5. Summary and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.; Guo, J.; Cong, R.; Pang, Y.; Wang, J. Underwater image enhancement by dehazing with minimum information loss and histogram distribution prior. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2016, 25, 5664–5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Guo, L.; Luo, C.; Zhou, X.; Yu, C. A survey of target detection and recognition methods in underwater turbid areas. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlamery, B.L. A computer model for underwater camera systems. Proc. SPIE 1980, 208, 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado, J.; Sekimori, Y.; Toriyama, A.; Ohashi, M.; Chun, S.; Maki, T. Photogrammetry-based photic seafloor surveying and analysis with low-cost autonomous underwater and surface vehicles. J. Robot. Mechatron. 2024, 36, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhou, D.; Yuan, L.; Guo, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Vision-based underwater target real-time detection for autonomous underwater vehicle subsea exploration. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1087345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheus, M.; Guilherme, C.; Paulo, J.; Paulo, L.; Silvia, S. Underwater robots localization using multi-domain images: A survey. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2025, 111, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, W.; Shao, J.; Miao, J. An improved SIFT underwater image stitching method. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, R.; Li, D.; Lin, M.; Xiao, S.; Lin, R. Image stitching and target perception for autonomous underwater vehicle-collected side-scan sonar images. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1418113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Chen, J.; He, J.; Zhou, Y. Shallow marine high-resolution optical mosaics based on underwater scooter-borne camera. Sensors 2023, 23, 8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Liu, X.; Hu, Z.; Wang, G.; Zheng, B.; Watson, J.; Zheng, H. Underwater computational imaging: A survey. Intell. Mar. Technol. 2023, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Jain, K.; Shukla, A.K. A comparative analysis of feature detectors and descriptors for image stitching. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. A comparison of feature extraction methods in image stitching. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2023, 15, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Mao, S.; Li, M.; Kang, J. LMFD: Lightweight multi-feature descriptors for image stitching. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N. Image stitching based on feature detection and extraction: An analysis. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Image, Algorithms and Artificial Intelligence (ICIAAI 2024), Singapore, 9–11 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, T.; Wang, C.; Li, L.; Liu, G.; Li, N. Parallax-tolerant image stitching via segmentation-guided multi-homography warping. Signal Process. 2025, 230, 109245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntas, C. Feature point-based dense image matching algorithm for 3-D capture in terrestrial applications. J. Appl. Sci. 2022, 22, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mei, X.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, X.; Peng, Z.; Huang, J. Hyperspectral panoramic image stitching using robust matching and adaptive bundle adjustment. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracias, N.; Santos-Victor, J.-V. Underwater mosaicing and trajectory reconstruction using global alignment. In Proceedings of the MTS/IEEE OCEANS 2001: An Ocean Odyssey, Honolulu, HI, USA, 5–8 November 2001; pp. 2557–2563. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, X. Fast Target Recognition Based on Improved ORB Feature. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. Research on multi-sensor data fusion technology for underwater robots for deep-sea exploration. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yang, X.; Li, N.; Wang, T.; Ji, G. Underwater image quality assessment method based on color space multi-feature fusion. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X. Comparison and Application of Implementing Image Feature Matching Using Ratio Test and RANSAC; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rublee, E.; Rabaud, V.; Konolige, K.; Bradski, G. ORB: An efficient alternative to SIFT or SURF. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference Computer Vision (ICCV), Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 2564–2571. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.; Stephens, M. A combined corner and edge detector. In Proceedings of the 4th Alvey Vision Conference, Manchester, UK, 31 August–2 September 1988; pp. 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Cover, T.; Hart, P. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random sample consensus: A paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Hu, X.; Xiang, D.; Xiao, J.; Cheng, H. Point set registration-based image stitching in unmanned aerial vehicle transmission line inspection. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process 2025, 2025, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Lai, Y.; Wang, T.; Zou, S.; Cai, H.; Xie, H. Single underwater image enhancement based on adaptive correction of channel differential and fusion. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 9, 1058019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajlah, M. Underwater image enhancement using customized CLAHE and adaptive color correction method. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 311. [Google Scholar]

- Murat, I. Comprehensive evaluation of feature extractors in challenging environments: The rationale behind the ratio test. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2415. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Hu, M. A novel lightweight model for underwater image enhancement—Rep-UWnet. Sensors 2024, 24, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Su, B.; Zhe, X.; Tang, J.; Yan, J.; Liang, W.; Chen, J. Single underwater image enhancement based on differential attenuation compensation. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1047053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, U.; Akter, M.; Uddin, M. Image quality assessment through FSIM, SSIM, MSE and PSNR—A comparative study. J. Comput. Commun. 2019, 7, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, R.; Chen, G.; Huang, Z.; Teng, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z. Underwater image enhancement using Divide-and-Conquer network (DC-Net). PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0294609. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Gao, F.; Yu, J.; Yu, X.; Yang, Z. Underwater Image Mosaic Algorithm Based on Improved Image Registration. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, J. Fast calibration and stitching algorithm for underwater camera systems. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 18629–18644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Li, M.; Gruen, A.; Gong, J.; Li, D.; Li, M.; Qin, J. Application of Photogrammetric Computer Vision and Deep Learning in High-Resolution Underwater Mapping: A Case Study of Shallow-Water Coral Reefs. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 10, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Effectiveness of Traditional Augmentation Methods for Rebar Counting Using UAV Imagery with Faster R-CNN and YOLOv10-Based Transformer Architectures. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Development of an Approach to an Automated Acquisition of Static Street View Images Using Transformer Architecture for Analysis of Building Characteristics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megha, V.; Rajkumar, K.K. Seamless panoramic image stitching based on invariant feature detector and image blending. Int. J. Image Graph. Signal Process 2024, 16, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Spadaro, A.; Chiabrando, F.; Lingua, A.; Maschio, P. Photogrammetry and Traditional Bathymetry for High-Resolution Underwater Mapping in Shallow Waters. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 48, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

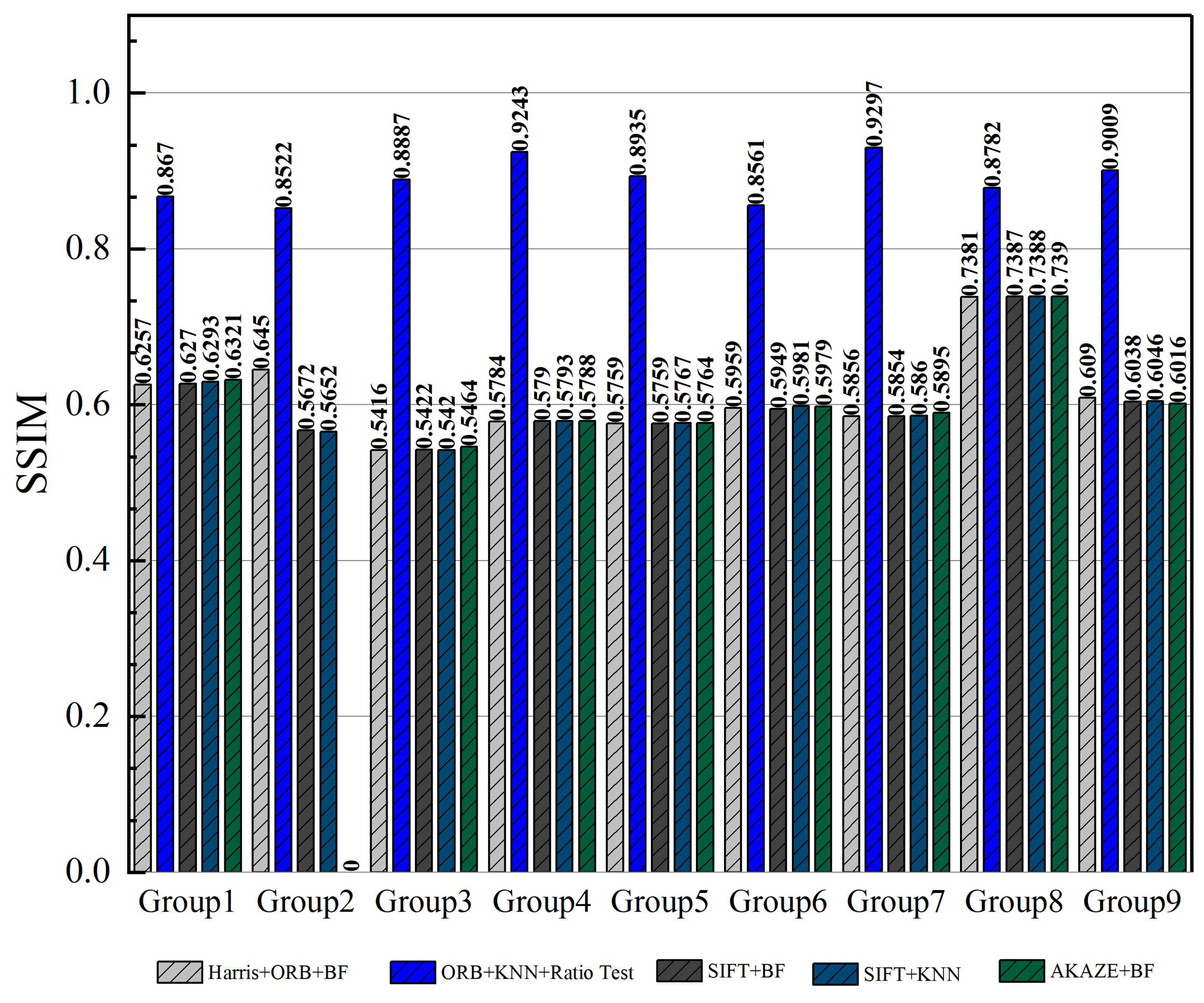

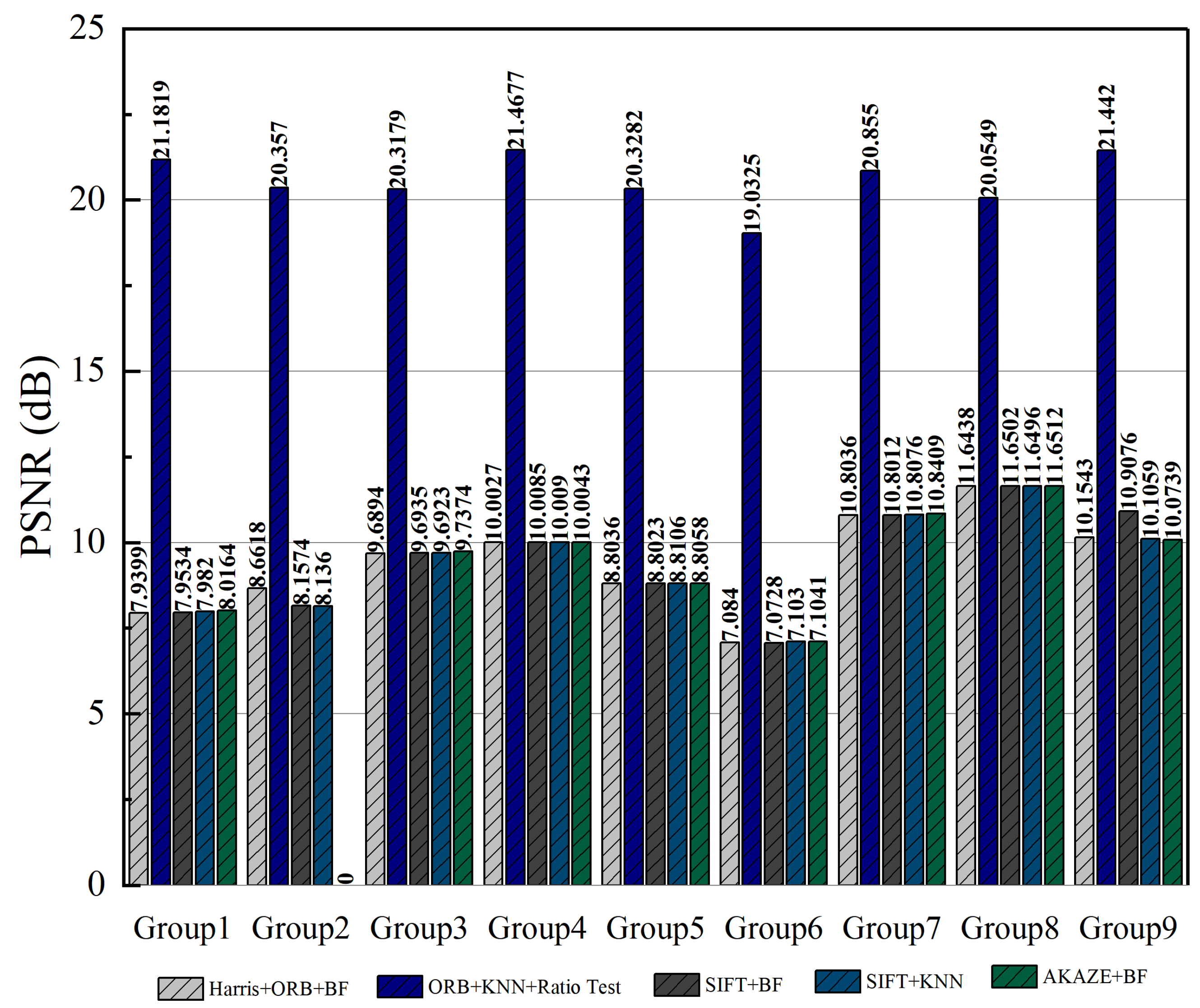

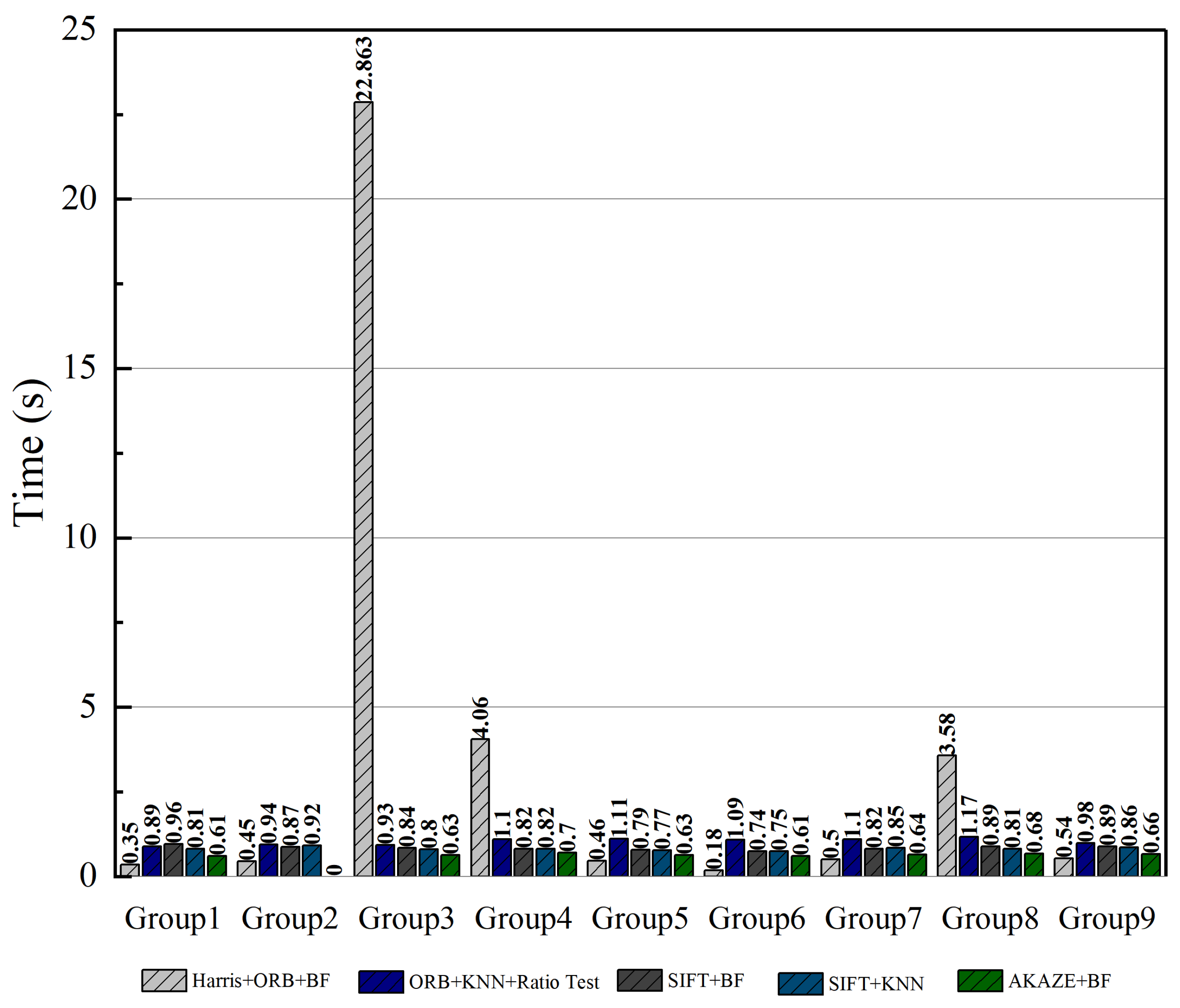

| Group Number | Algorithm | SSIM | PSNR | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Harris + ORB + BF | 0.6257 | 7.9399 | 0.35 |

| ORB-KNN-Ratio test | 0.8670 | 21.1819 | 0.89 | |

| SIFT + BF | 0.6270 | 7.9534 | 0.96 | |

| SIFT + KNN | 0.6293 | 7.9820 | 0.81 | |

| AKAZE + BF | 0.6321 | 8.0164 | 0.61 | |

| Group 2 | Harris + ORB + BF | 0.6450 | 8.6618 | 0.45 |

| ORB-KNN-Ratio test | 0.8522 | 20.3570 | 0.94 | |

| SIFT + BF | 0.5672 | 8.1574 | 0.87 | |

| SIFT + KNN | 0.5652 | 8.1360 | 0.92 | |

| AKAZE + BF | Insufficient feature points for matching | |||

| Group 3 | Harris + ORB + BF | 0.5416 | 9.6894 | 22.863 |

| ORB-KNN-Ratio test | 0.8887 | 20.3179 | 0.93 | |

| SIFT + BF | 0.5422 | 9.6935 | 0.84 | |

| SIFT + KNN | 0.5420 | 9.6923 | 0.80 | |

| AKAZE + BF | 0.5464 | 9.7374 | 0.63 | |

| Group 4 | Harris + ORB + BF | 0.5784 | 10.0027 | 4.06 |

| ORB-KNN-Ratio test | 0.9243 | 21.4677 | 1.10 | |

| SIFT + BF | 0.5790 | 10.0085 | 0.82 | |

| SIFT + KNN | 0.5793 | 10.0090 | 0.82 | |

| AKAZE + BF | 0.5788 | 10.0043 | 0.70 | |

| Group 5 | Harris + ORB + BF | 0.5759 | 8.8036 | 0.46 |

| ORB-KNN-Ratio test | 0.8935 | 20.3282 | 1.11 | |

| SIFT + BF | 0.5759 | 8.8023 | 0.79 | |

| SIFT + KNN | 0.5767 | 8.8106 | 0.77 | |

| AKAZE + BF | 0.5764 | 8.8058 | 0.63 | |

| Group 6 | Harris + ORB + BF | 0.5959 | 7.0840 | 0.18 |

| ORB-KNN-Ratio test | 0.8561 | 19.0325 | 1.09 | |

| SIFT + BF | 0.5949 | 7.0728 | 0.74 | |

| SIFT + KNN | 0.5981 | 7.1030 | 0.75 | |

| AKAZE + BF | 0.5979 | 7.1041 | 0.61 | |

| Group 7 | Harris + ORB + BF | 0.5856 | 10.8036 | 0.50 |

| ORB-KNN-Ratio test | 0.9297 | 20.8550 | 1.10 | |

| SIFT + BF | 0.5854 | 10.8012 | 0.82 | |

| SIFT + KNN | 0.5860 | 10.8076 | 0.85 | |

| AKAZE + BF | 0.5895 | 10.8409 | 0.64 | |

| Group 8 | Harris + ORB + BF | 0.7381 | 11.6438 | 3.58 |

| ORB-KNN-Ratio test | 0.8782 | 20.0549 | 1.17 | |

| SIFT + BF | 0.7387 | 11.6502 | 0.89 | |

| SIFT + KNN | 0.7388 | 11.6496 | 0.81 | |

| AKAZE + BF | 0.7390 | 11.6512 | 0.68 | |

| Group 9 | Harris + ORB + BF | 0.6090 | 10.1543 | 0.54 |

| ORB-KNN-Ratio test | 0.9009 | 21.4420 | 0.98 | |

| SIFT + BF | 0.6038 | 10.9076 | 0.89 | |

| SIFT + KNN | 0.6046 | 10.1059 | 0.86 | |

| AKAZE + BF | 0.6016 | 10.0739 | 0.66 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yi, G.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.; Yu, D. An Improved ORB-KNN-Ratio Test Algorithm for Robust Underwater Image Stitching on Low-Cost Robotic Platforms. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020218

Yi G, Zhang T, Chen Y, Yu D. An Improved ORB-KNN-Ratio Test Algorithm for Robust Underwater Image Stitching on Low-Cost Robotic Platforms. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(2):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020218

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, Guanhua, Tianxiang Zhang, Yunfei Chen, and Dapeng Yu. 2026. "An Improved ORB-KNN-Ratio Test Algorithm for Robust Underwater Image Stitching on Low-Cost Robotic Platforms" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 2: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020218

APA StyleYi, G., Zhang, T., Chen, Y., & Yu, D. (2026). An Improved ORB-KNN-Ratio Test Algorithm for Robust Underwater Image Stitching on Low-Cost Robotic Platforms. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(2), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020218