Data Augmentation and Time–Frequency Joint Attention for Underwater Acoustic Communication Modulation Classification

Abstract

1. Introduction

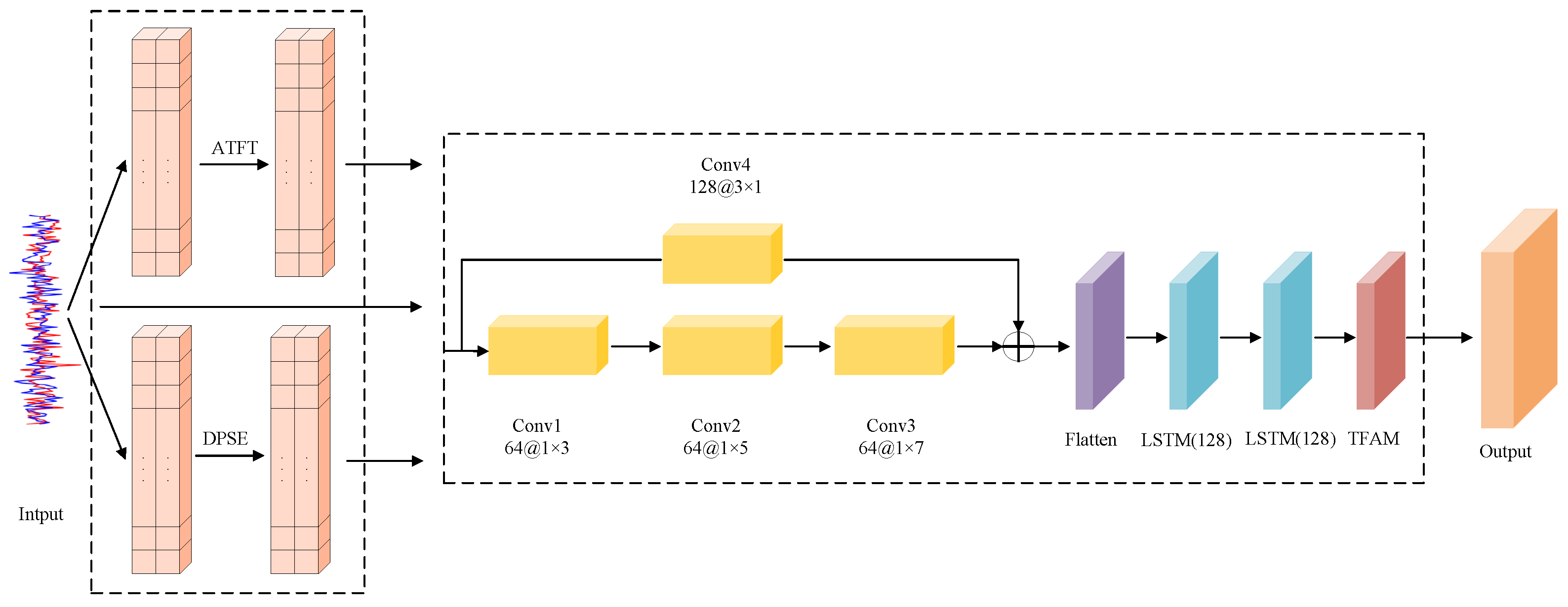

2. DA-TFJA

2.1. Algorithm Framework

2.2. Data Augmentation Algorithm

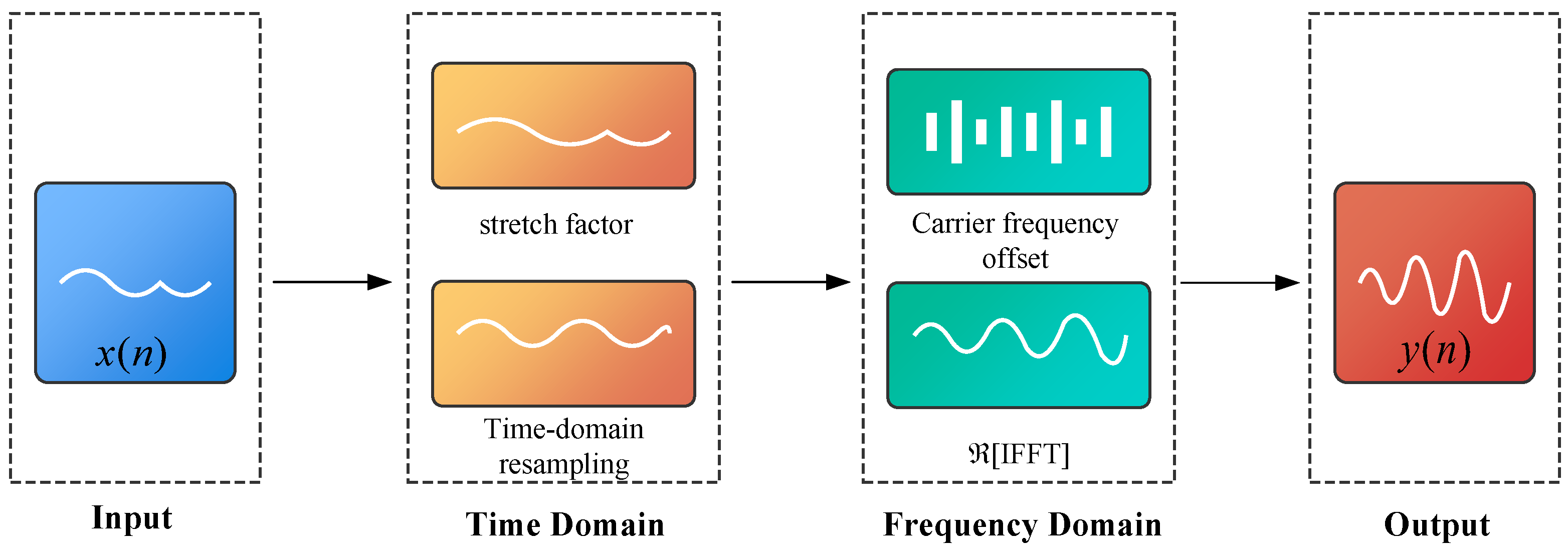

2.2.1. ATFT

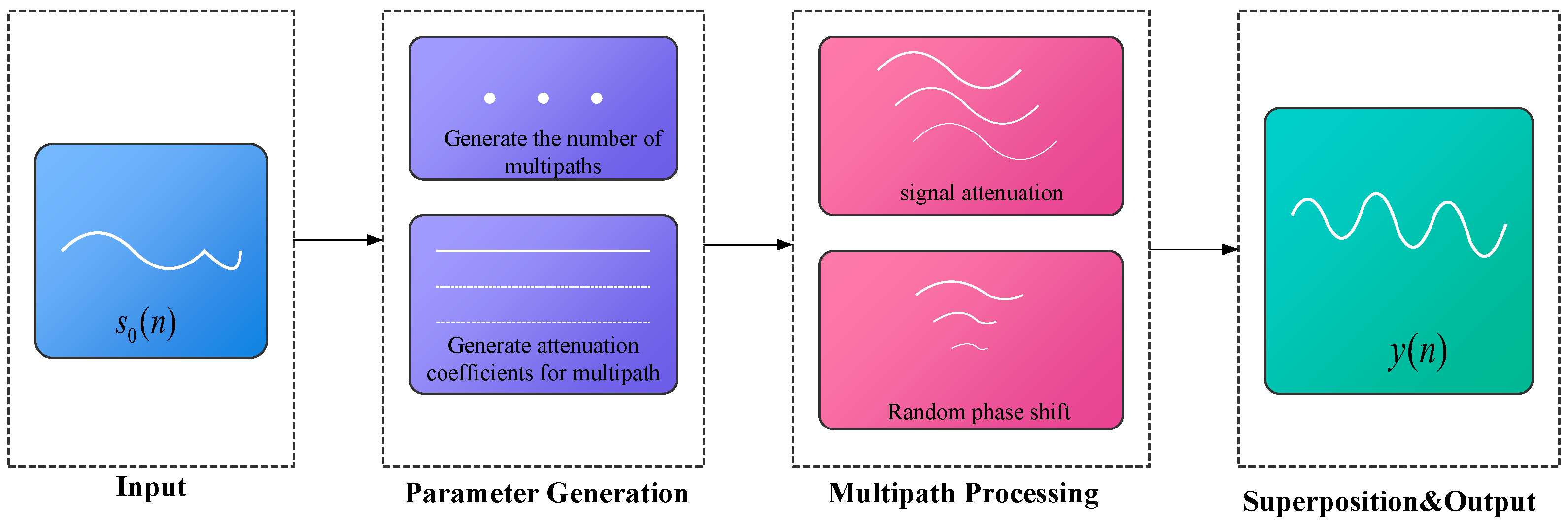

2.2.2. DPSE

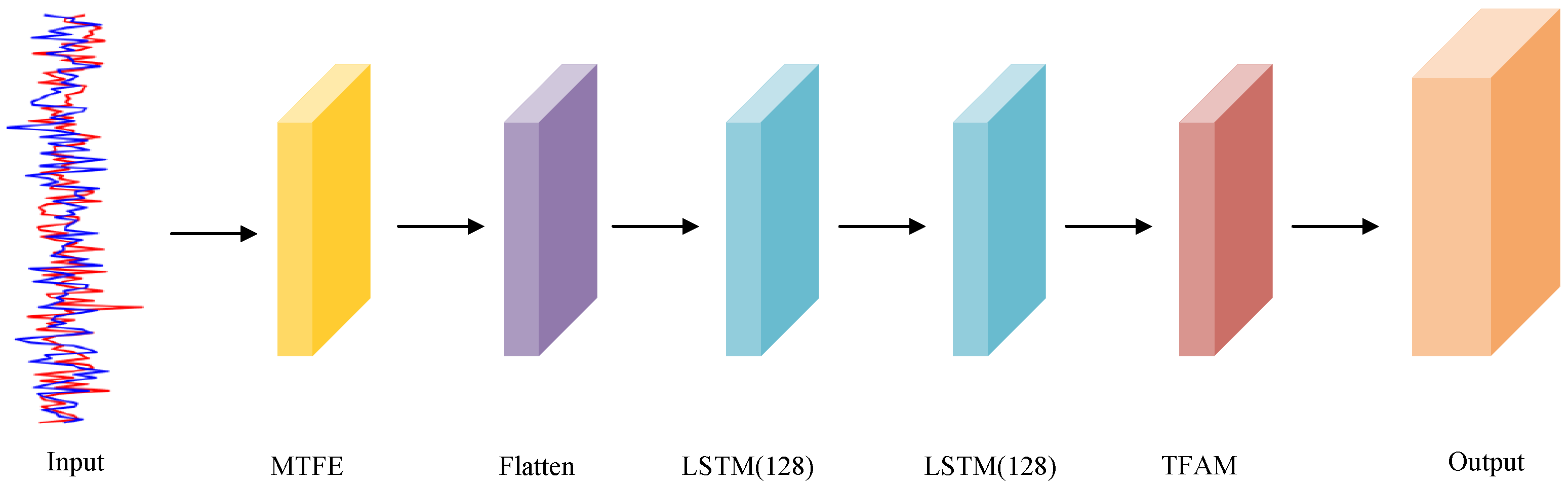

2.3. Feature Extraction Network

2.3.1. Overall Feature Extraction Network Framework

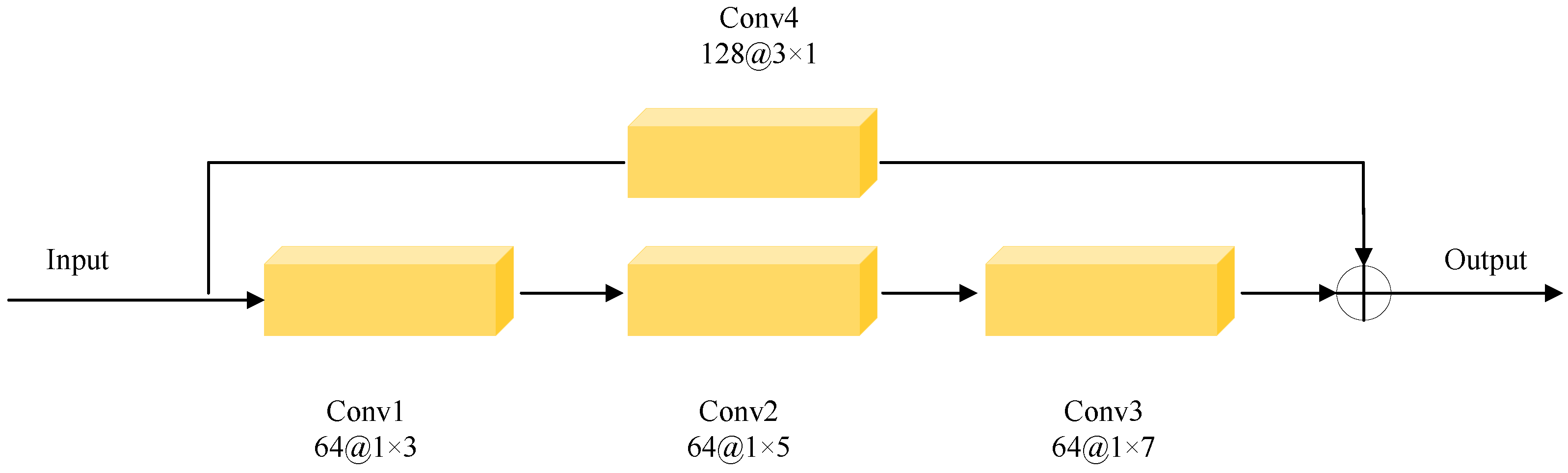

2.3.2. MTFE

2.3.3. TFAM

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Experimental Setup and Dataset Introduction

3.1.1. Introduction to the Dataset

3.1.2. Experimental Setup

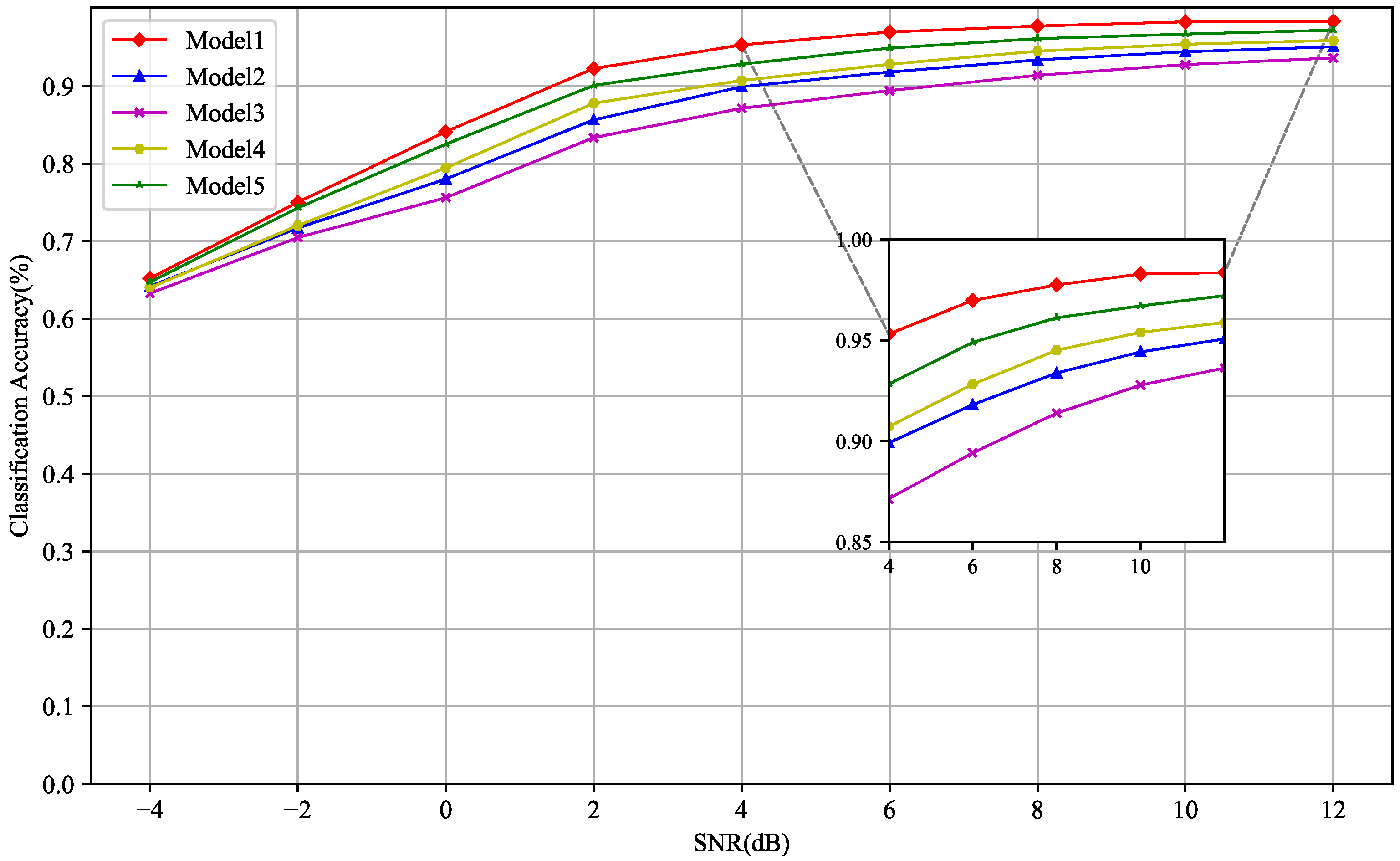

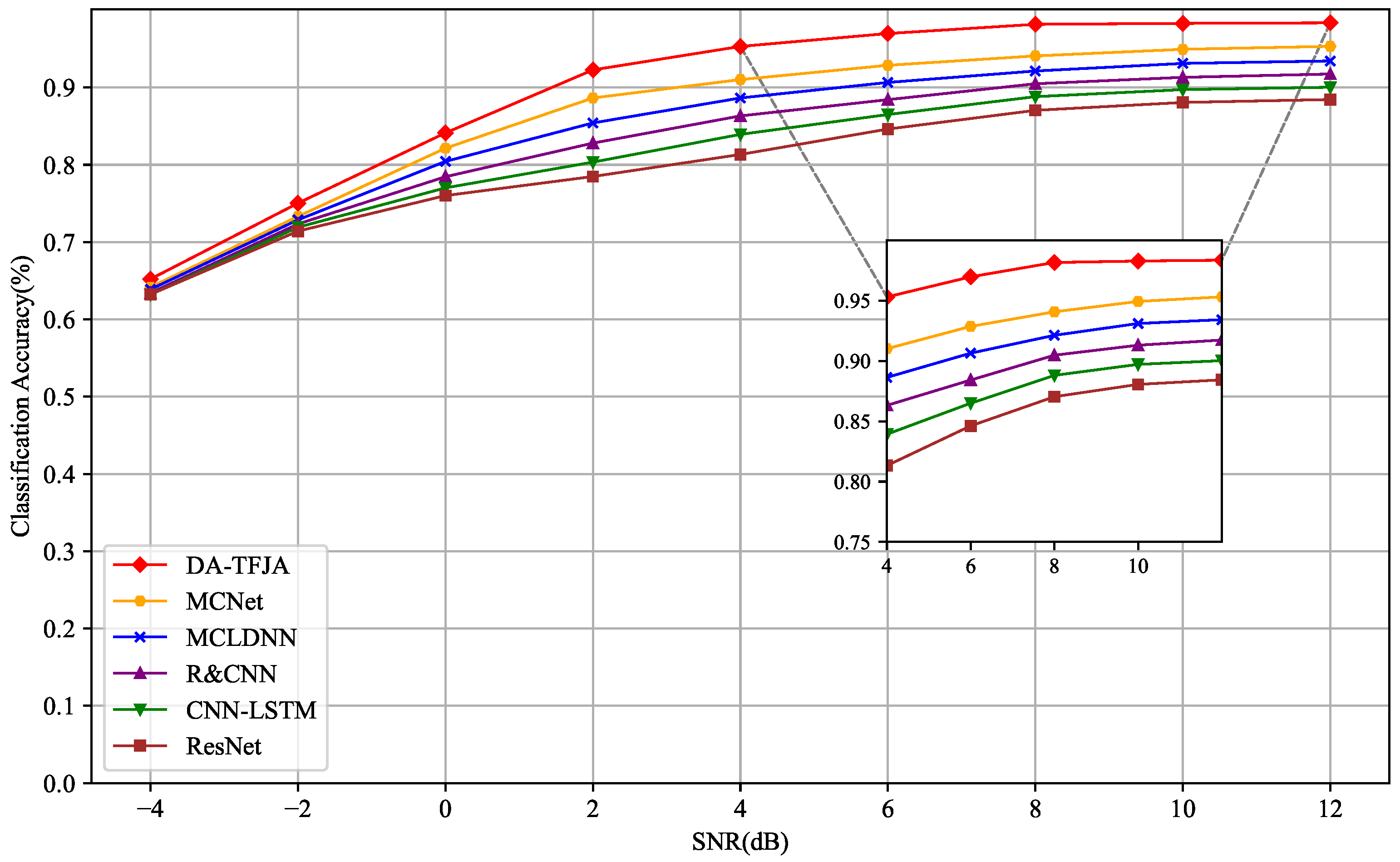

3.1.3. Accuracy Comparison Across Network Models

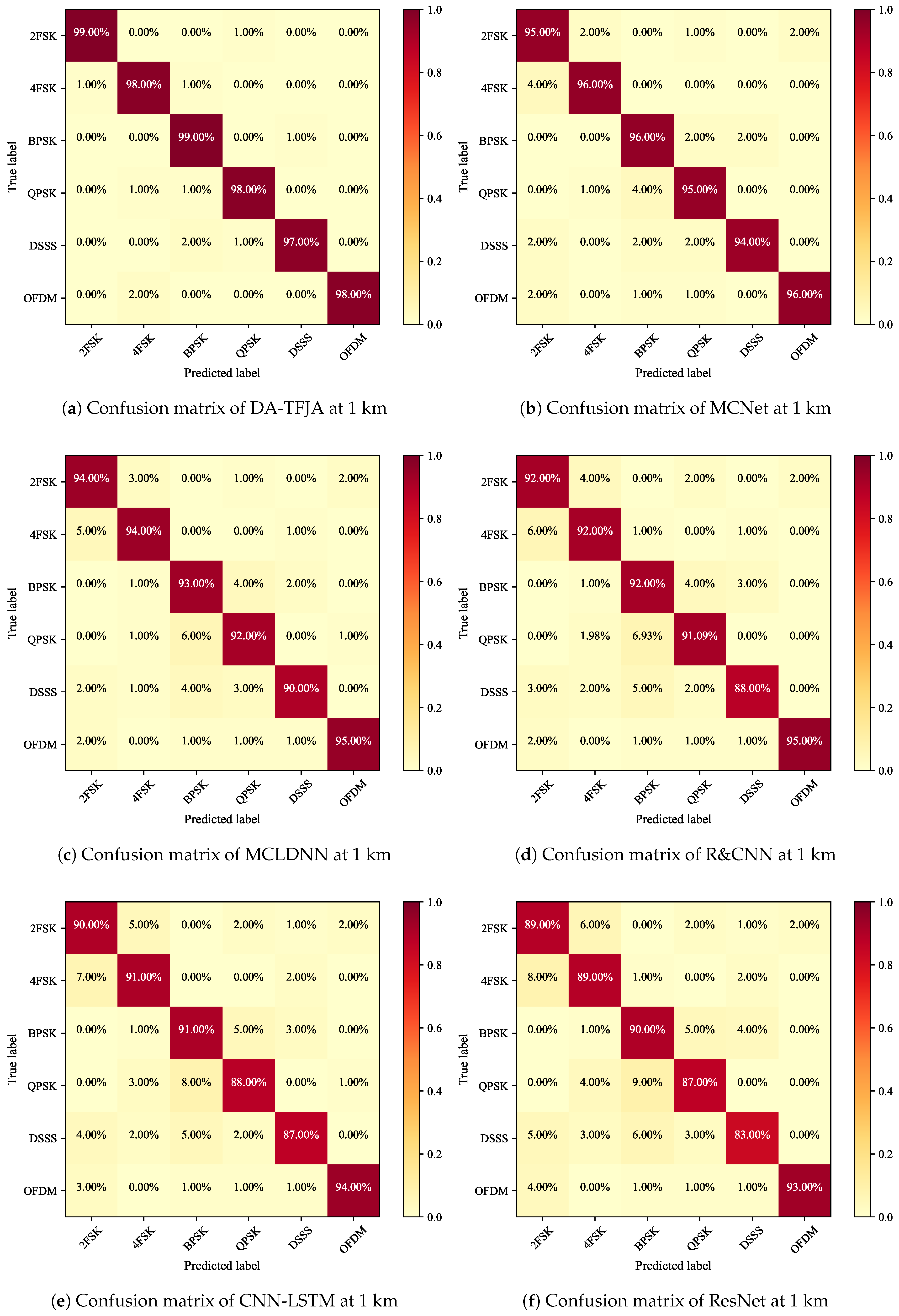

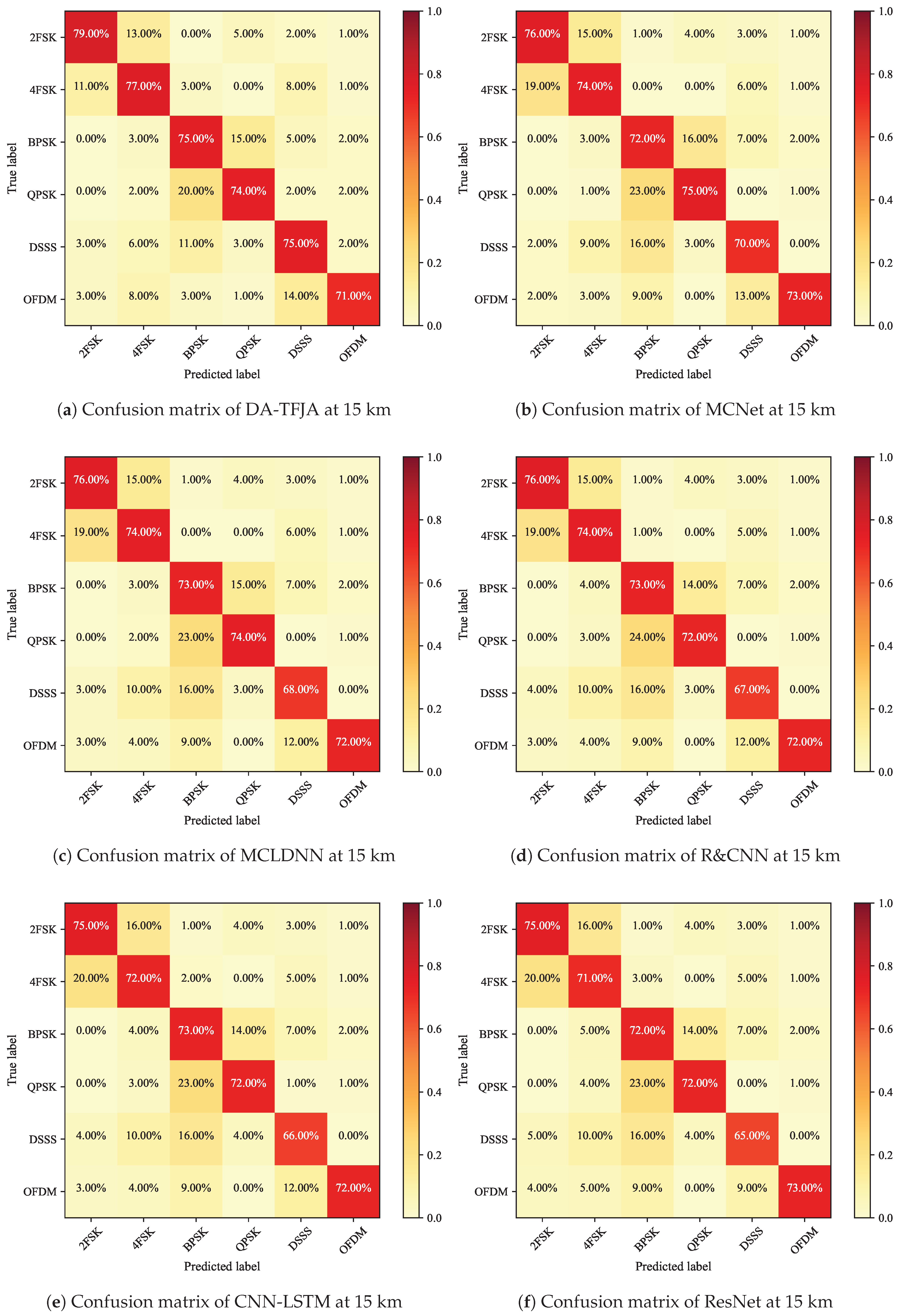

3.1.4. Confusion Matrix Analysis at Different Distances

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UWA | Underwater acoustic |

| DA-TFJA | Data augmentation and time–frequency joint attention |

| ATFE | Adaptive time–frequency transform enhancement algorithm |

| DPSE | Dynamic path superposition enhancement algorithm |

| MTFE | Multiscale time–frequency feature extractor |

| TFAM | Time–frequency joint attention mechanism |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| GAN | Generative adversarial network |

| AMC | Automatic modulation classification |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratios |

| CFO | Carrier frequency offset |

| R&CNN | Recurrent and convolutional neural network |

| MCLDNN | Multi-channel convolutional and LSTM deep neural network |

| SENet | Squeeze-and-excitation network |

| ResNet | Residual network |

| DFT | Discrete fourier transform |

References

- Wang, Y.; Shen, T.; Wang, T.; Qiao, G.; Zhou, F. Modulation recognition for underwater acoustic communication based on hybrid neural network and feature fusion. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 225, 110185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Cheng, X.; Wei, Q.; Tang, N. Underwater acoustic signal classification based on a spatial–temporal fusion neural network. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1331717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Underwater Acoustic Target Recognition Based on Data Augmentation and Residual CNN. Electronics 2023, 12, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wu, H.; Yue, Z.; Li, H. An Underwater Acoustic Communication Signal Modulation-Style Recognition Algorithm Based on Dual-Feature Fusion and ResNet–Transformer Dual-Model Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, H.; Fang, T. Modulation recognition of underwater acoustic communication signals based on deep learning. Eurasip J. Adv. Signal Process. 2024, 2024, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yoon, S.; Fuentes, A.; Park, D.S. A Comprehensive Survey of Image Augmentation Techniques for Deep Learning. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 137, 109347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.; Gu, Z. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition: A Survey. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D.; Mu, N.; Cubuk, E.D.; Zoph, B.; Gilmer, J.; Lakshminarayanan, B. AugMix: A Simple Data Processing Method to Improve Robustness and Uncertainty. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1912.02781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubuk, E.D.; Zoph, B.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. RandAugment: Practical Automated Data Augmentation with a Reduced Search Space. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33, NEURIPS 2020, Proceedings of the 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Electr Network, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2020; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

- DeVries, T.; Taylor, G.W. Improved Regularization of Convolutional Neural Networks with Cutout. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.04552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Zheng, L.; Kang, G.; Li, S.; Yang, Y. Random Erasing Data Augmentation. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Proceedings of the 34th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence/32nd Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference/10th AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2020; Volume 34, pp. 13001–13008. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Metz, L.; Chintala, S. Unsupervised Representation Learning with Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, T.; Laine, S.; Aila, T. A Style-Based Generator Architecture for Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Hou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Gui, G.; Gacanin, H.; Mao, S.; Adachi, F. Supervised Contrastive Learning for RFF Identification With Limited Samples. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 17293–17306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Xiang, X.; Liang, Y.; Liu, K. Modulation classification with data augmentation based on a semi-supervised generative model. Wirel. Netw. 2024, 30, 5683–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H. Automatic Modulation Classification Based on CNN and Multiple Kernel Maximum Mean Discrepancy. Electronics 2023, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, A.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M. Hybrid Data Augmentation and Dual-Stream Spatiotemporal Fusion Neural Network for Automatic Modulation Classification in Drone Communications. Drones 2023, 7, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Xu, D.; Xu, X.; Chen, Z.; Xuan, Q.; Wang, W.; Lin, Y.; Yang, X. A simple data augmentation method for automatic modulation recognition via mixing signals. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Robotics, Intelligent Control and Artificial Intelligence (RICAI), Nanjing, China, 6–8 December 2024; pp. 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, P.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Z. Diffusion Model Empowered Data Augmentation for Automatic Modulation Recognition. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2025, 14, 1224–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, F.; Shen, T.; Chen, L.; Zhao, D. Data augmentation method for underwater acoustic target recognition based on underwater acoustic channel modeling and transfer learning. Appl. Acoust. 2023, 208, 109344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, S.; Hema, L.K.; Jenitha, J.; Regilan, S. Deep Learning-Driven Autoencoder Models for Robust Underwater Acoustic Communication: A Survey on DCAEs, VAEs, Adaptive Modulation. In Proceedings of the 2025 11th International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), Melmaruvathur, India, 5–7 June 2025; pp. 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Z.; He, J.; Li, J.; Ding, H.; Guo, T.; Chen, K. LW-MS-LFTFNet: A Lightweight Multi-Scale Network Integrating Low-Frequency Temporal Features for Ship-Radiated Noise Recognition. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Leng, C.; Wang, J.; Mao, S. Modulation Recognition of Underwater Acoustic Signals Using Deep Hybrid Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 5977–5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Luo, C.; Parr, G.; Luo, Y. A Spatiotemporal Multi-Channel Learning Framework for Automatic Modulation Recognition. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2020, 9, 1629–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-The, T.; Hua, C.H.; Pham, Q.V.; Kim, D.S. MCNet: An Efficient CNN Architecture for Robust Automatic Modulation Classification. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2020, 24, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Luo, H.; Wang, C.; Gan, C.; Xiang, Y. Automatic Modulation Classification Using CNN-LSTM Based Dual-Stream Structure. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 13521–13531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, T.J.; Roy, T.; Clancy, T.C. Over-the-Air Deep Learning Based Radio Signal Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2018, 12, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peng, Y. et al. [14] | Constellation diagram rotation | Enhances robustness to phase changes | Insufficient constellation diagram data remains |

| Yin, L. et al. [15] | GAN-based constellation generation | Effectively improves model generalization ability | Generated samples may lack authenticity; high computational complexity |

| Wang, N. et al. [16] | Signal rotation with RandMix strategy | Provides powerful solution to domain shift problem in AMC | Computational complexity too high for practical applications |

| Gong, A. et al. [17] | I/Q and A/P fusion with rotation and self-perturbation | Improves adaptability to complex environments | Limited recognition rate improvement for specific modulation types |

| Shen, W. et al. [18] | Mixed-signal augmentation framework | Effectively improves modulation classification accuracy | Destroys temporal dependency; introduces noise or incorrect learning patterns |

| Li, M. et al. [19] | Conditional diffusion model | Generates high-fidelity and diverse signal samples; solves training data insufficiency | High computational requirements; not optimized for UWA characteristics |

| Signal Type | Carrier Frequency (kHz) | Signal Bandwidth (kHz) | Duration (/s) | Signal Count | PN Code Order | Number of Subcarriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2FSK | 7.5 | 2 | 1 | 100 | – | – |

| 4FSK | 7.5 | 2 | 1 | 100 | – | – |

| BPSK | 7.5 | 2 | 1 | 100 | – | – |

| QPSK | 7.5 | 2 | 1 | 100 | – | – |

| DSSS | 7.5 | 2 | 1 | 100 | 5 | – |

| OFDM | 7.5 | 2 | 1 | 100 | – | 512 |

| Parameter Settings | Value |

|---|---|

| Epochs | 120 |

| Batch Size | 512 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning Rate | 0.001 |

| Patience | 15 |

| Dropout | 0.5 |

| Model | ATFT | DPSE | MTFE | TFAM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Model 2 | √ | √ | √ | |

| Model 3 | √ | √ | ||

| Model 4 | √ | √ | √ | |

| Model 5 | √ | √ | √ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cao, M.; Chen, Q.; Tang, J.; Wu, H. Data Augmentation and Time–Frequency Joint Attention for Underwater Acoustic Communication Modulation Classification. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020172

Cao M, Chen Q, Tang J, Wu H. Data Augmentation and Time–Frequency Joint Attention for Underwater Acoustic Communication Modulation Classification. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(2):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020172

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Mingyu, Qi Chen, Jinsong Tang, and Haoran Wu. 2026. "Data Augmentation and Time–Frequency Joint Attention for Underwater Acoustic Communication Modulation Classification" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 2: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020172

APA StyleCao, M., Chen, Q., Tang, J., & Wu, H. (2026). Data Augmentation and Time–Frequency Joint Attention for Underwater Acoustic Communication Modulation Classification. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(2), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020172