Rhodoliths as Global Contributors to a Carbonate Ecosystem Dominated by Coralline Red Algae with an Established Fossil Record

Abstract

1. Introduction

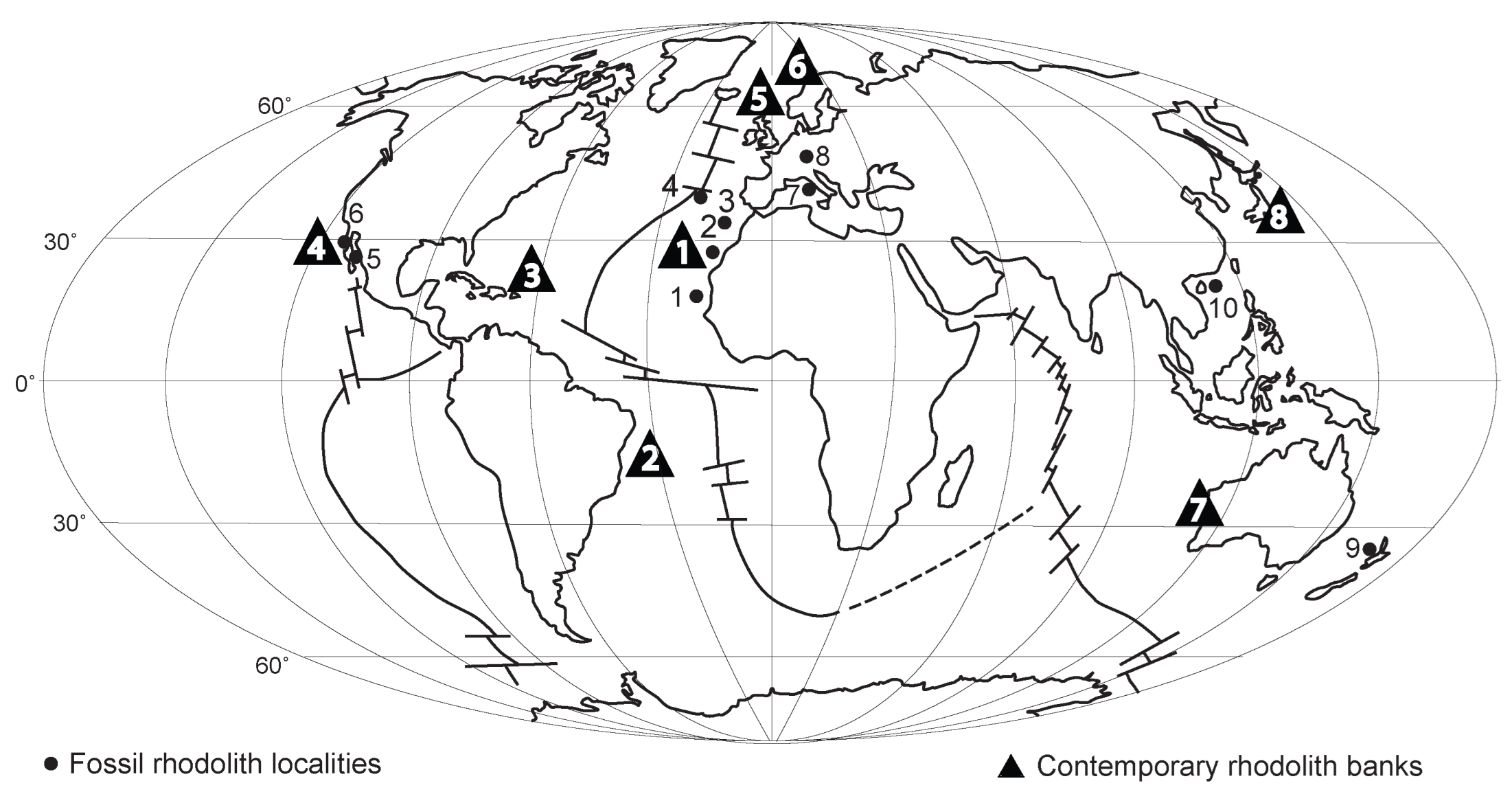

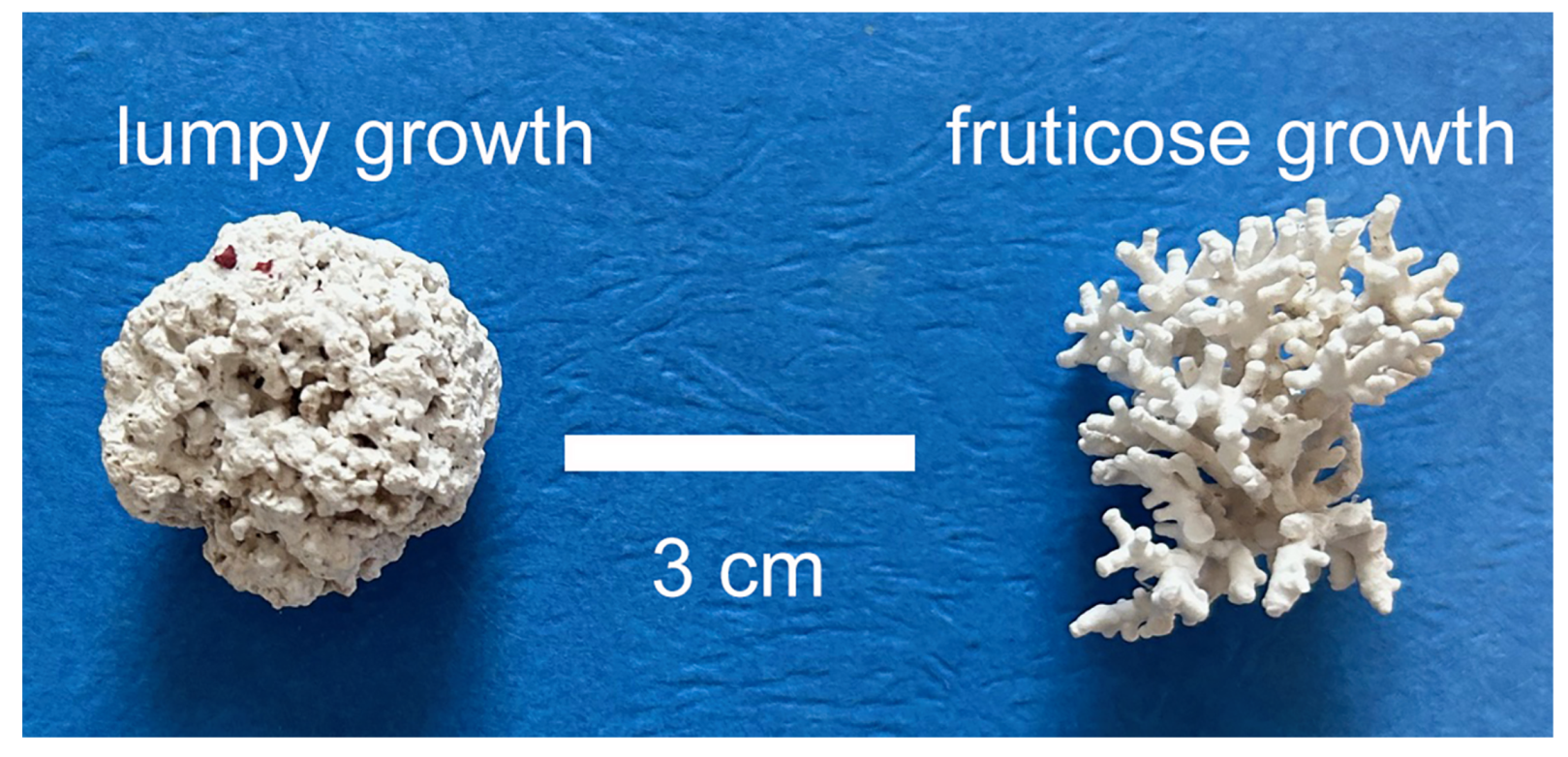

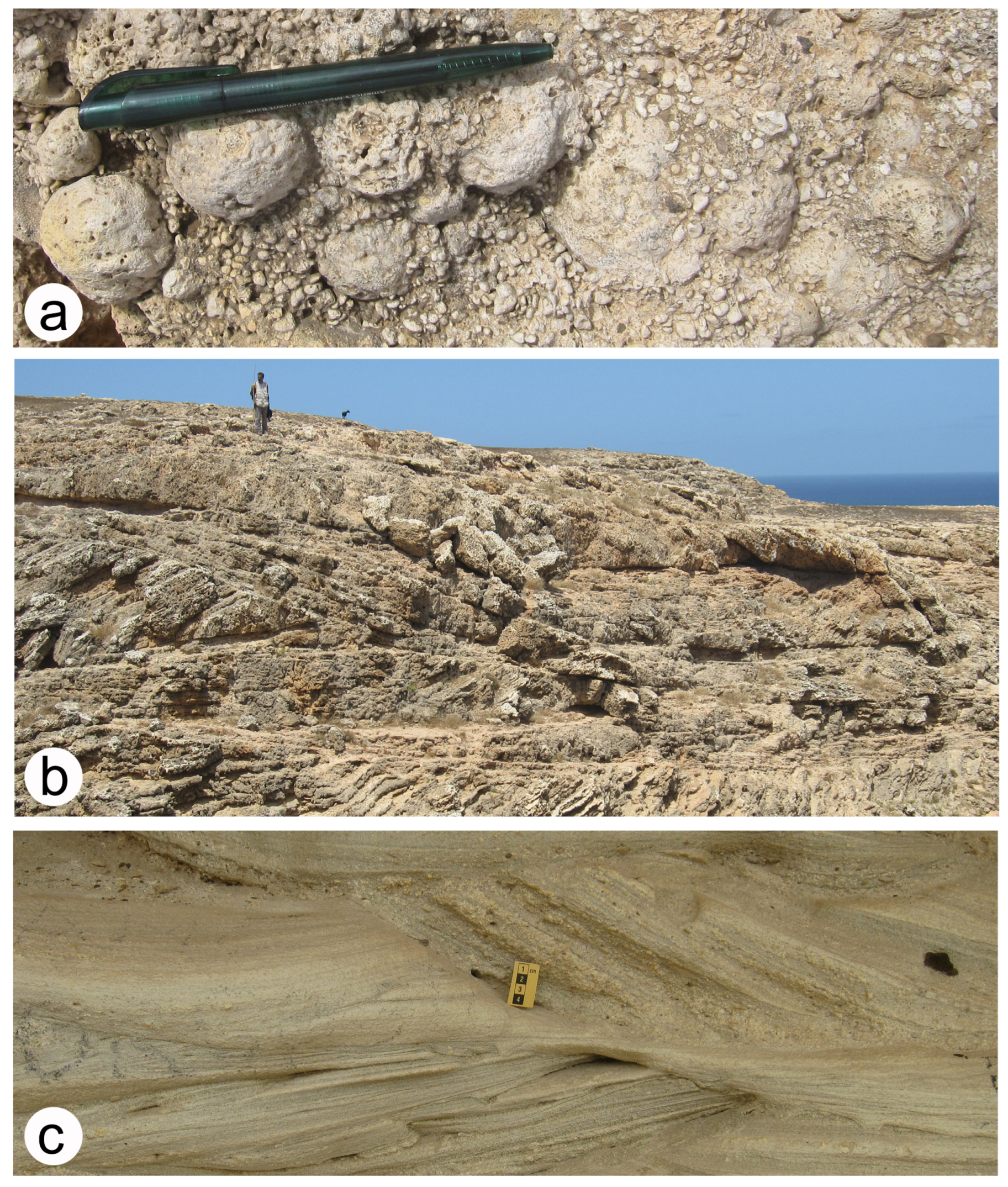

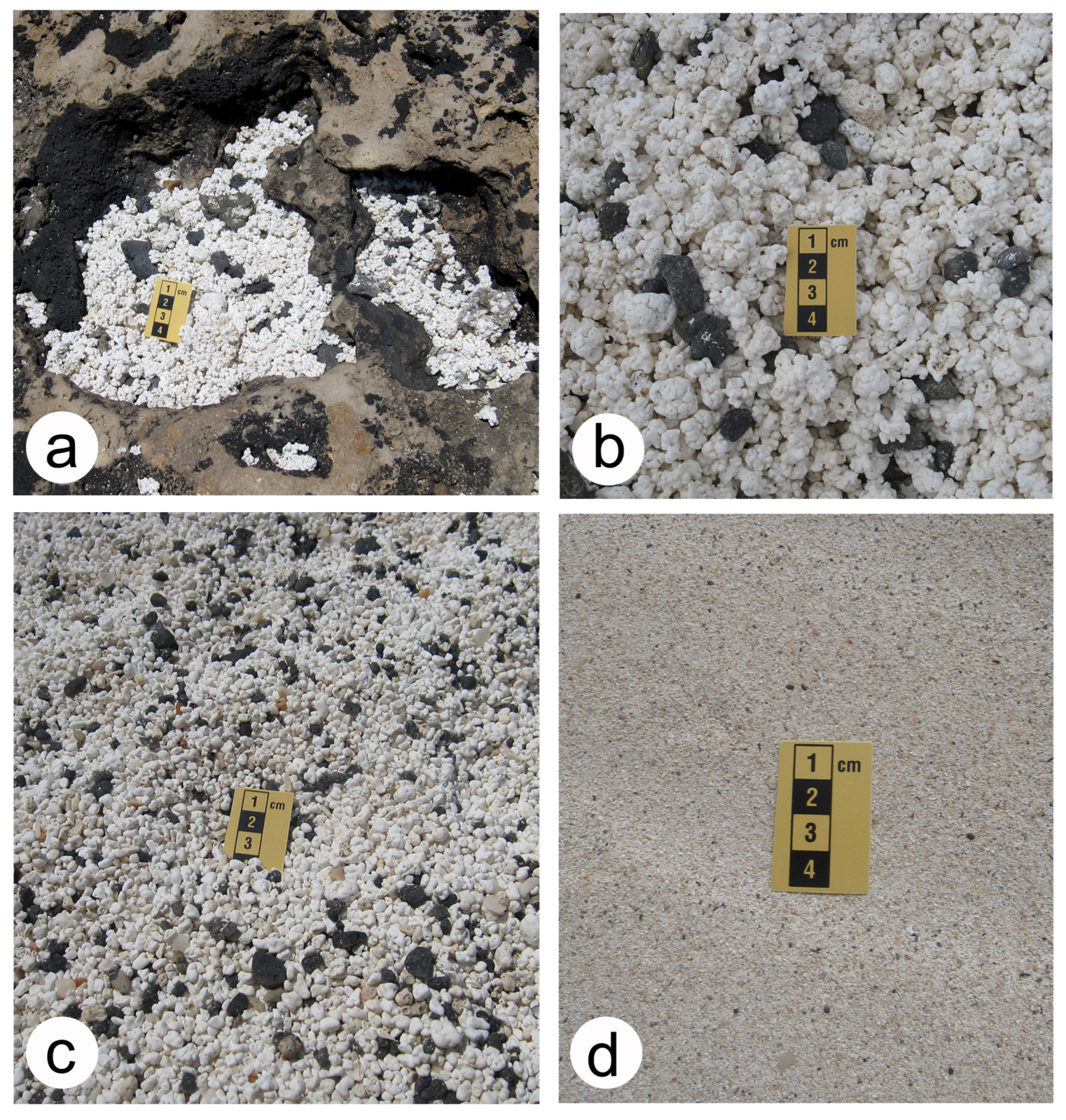

2. Background Ecology, Taphonomy, and Geological History

3. Review of Contemporary Rhodolith Distributions

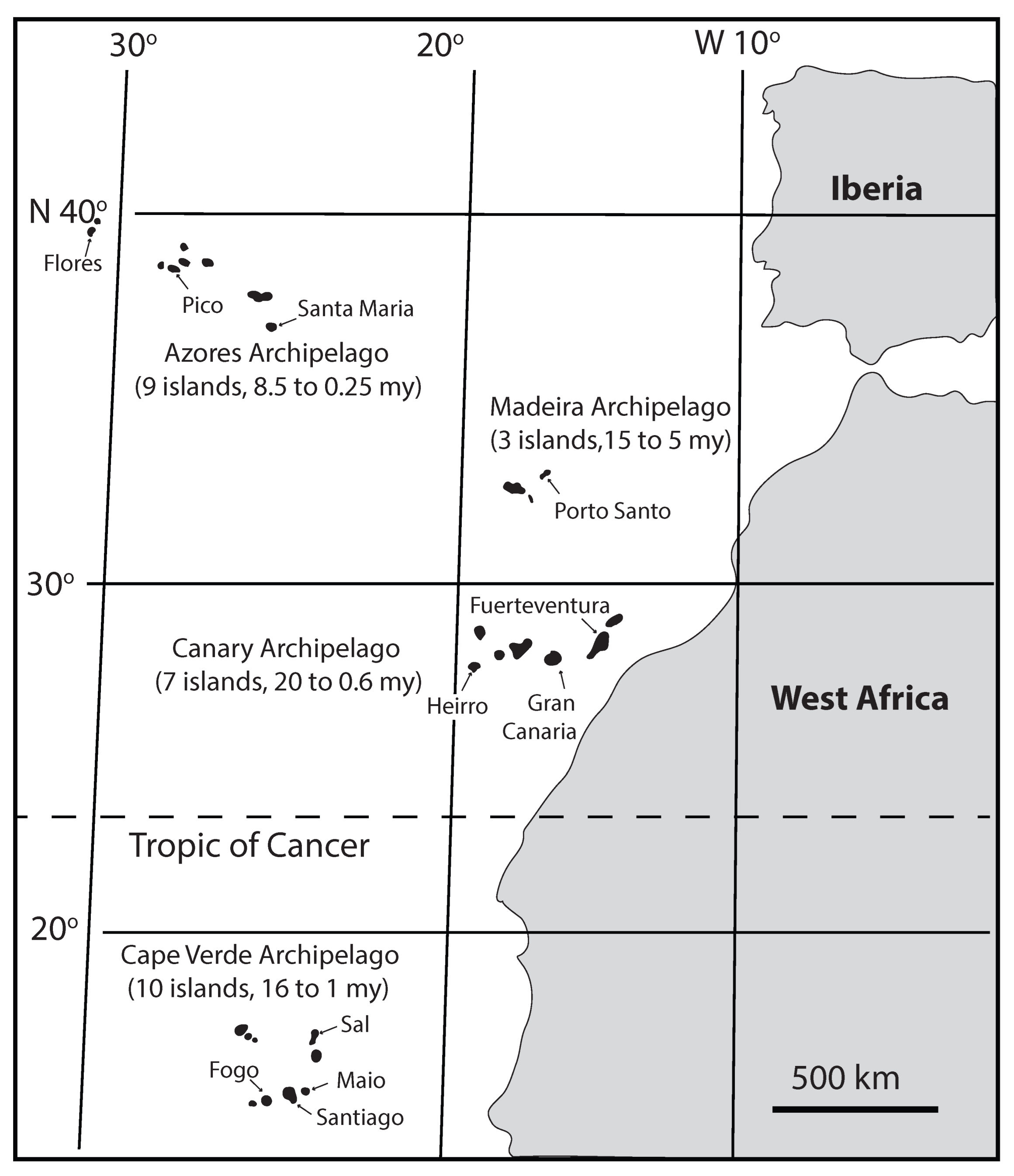

3.1. Contemporary Rhodoliths of the Macaronesian Realm

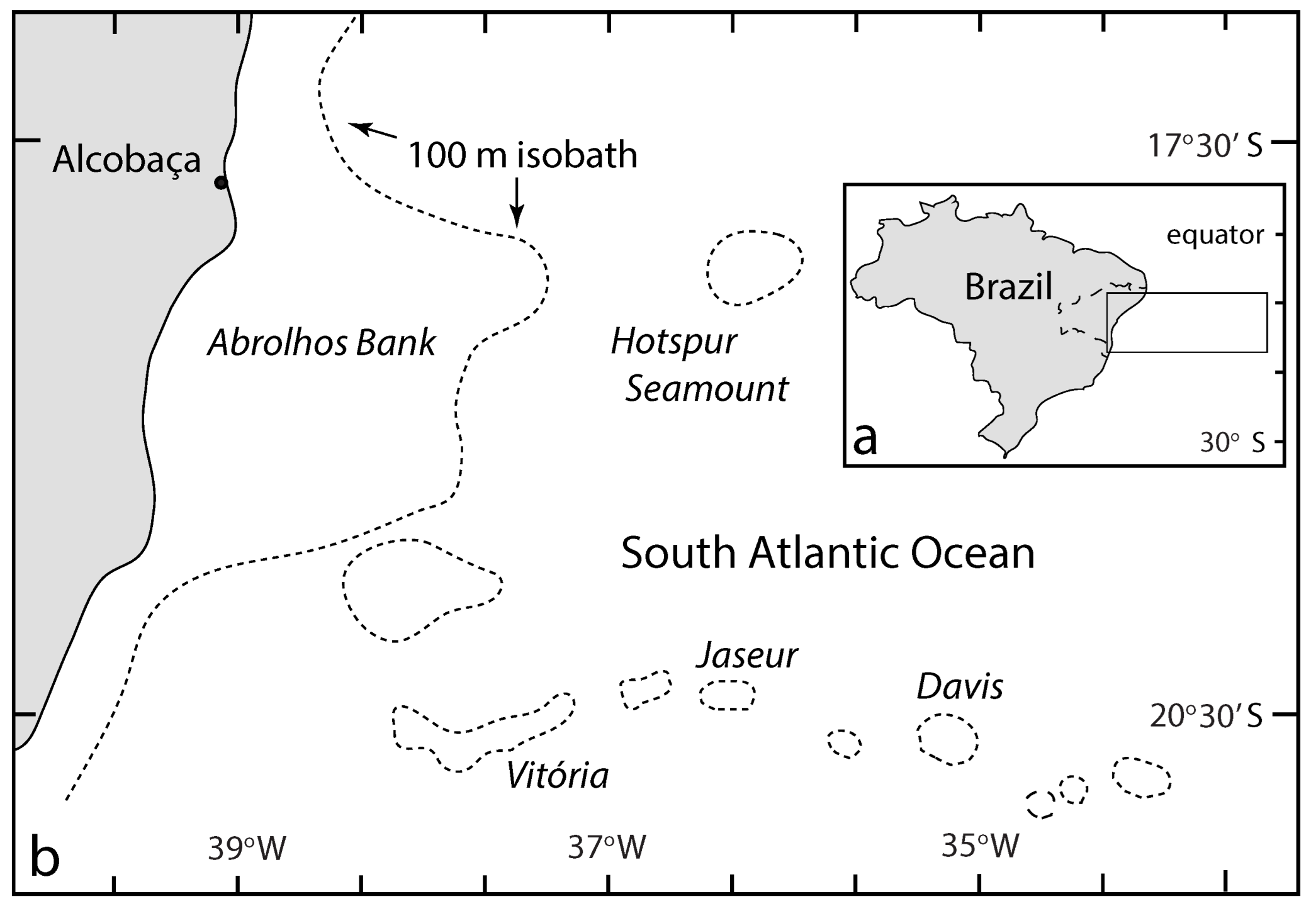

3.2. Contemporary Rhodoliths off Brazil in the South Atlantic

3.3. Contemporary Rhodoliths in the Caribbean Realm

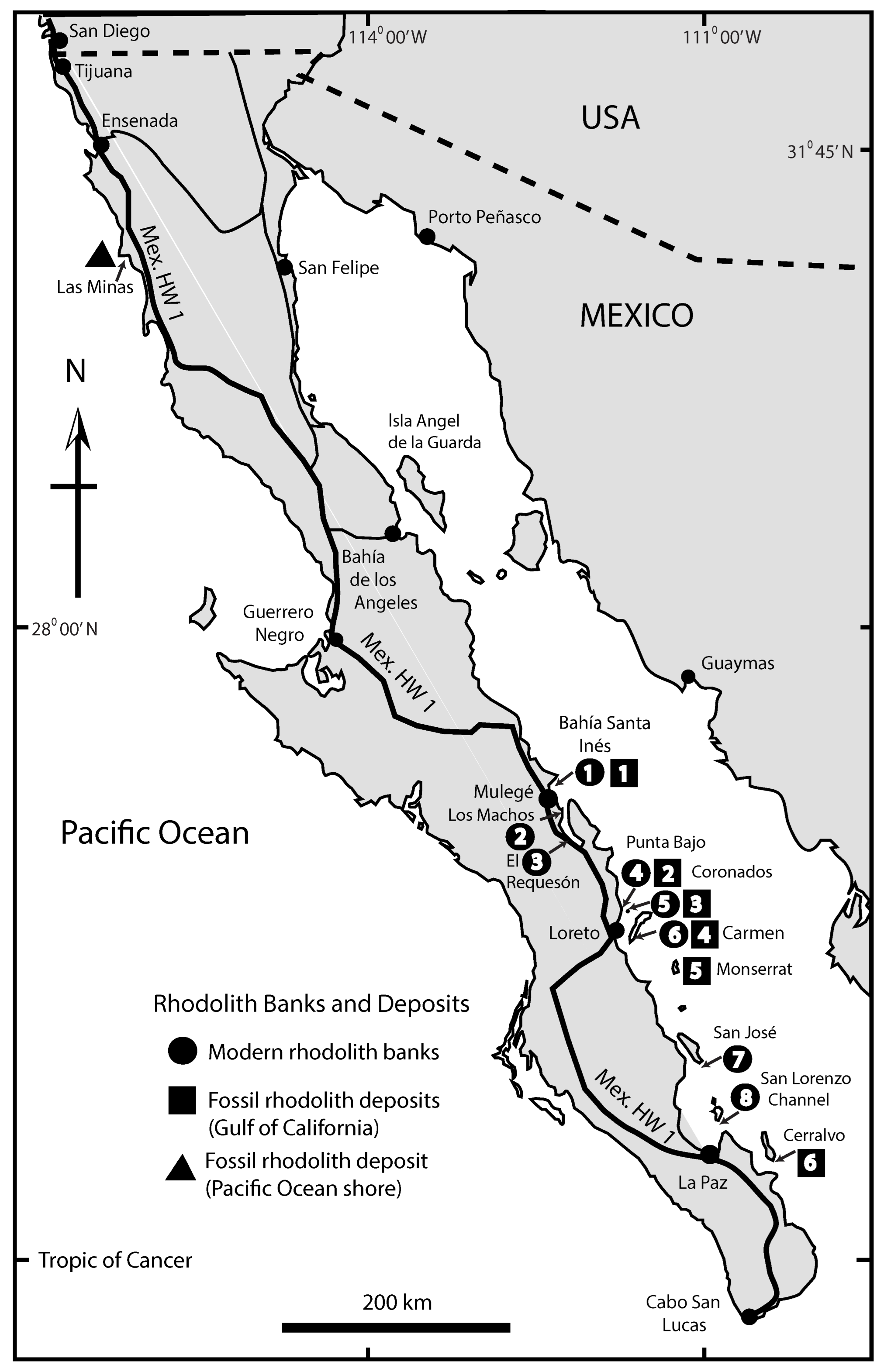

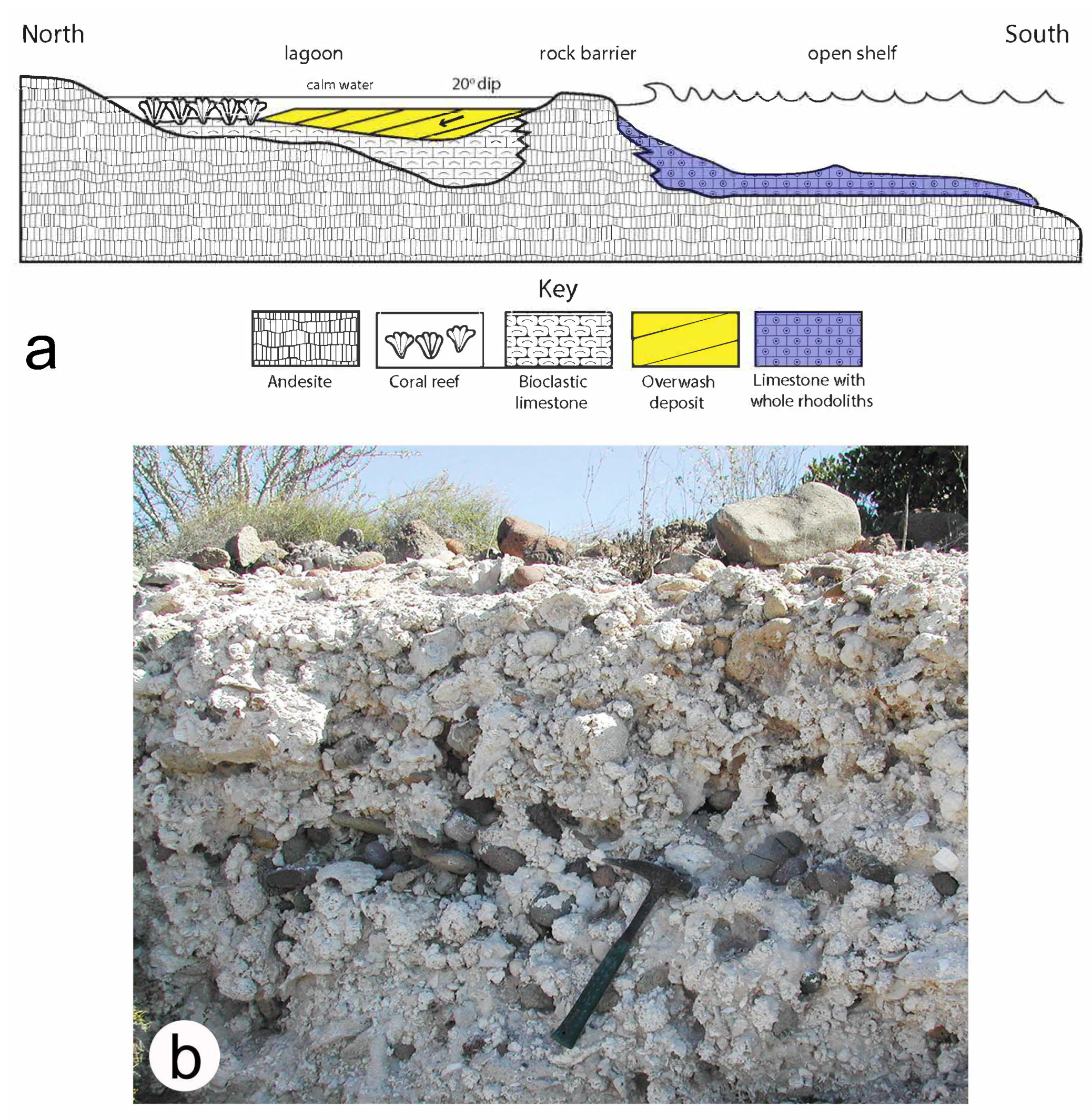

3.4. Contemporary Rhodoliths in Mexico’s Baja California Peninsula

3.5. Contemporary Rhodoliths off the Scottish Western Isles

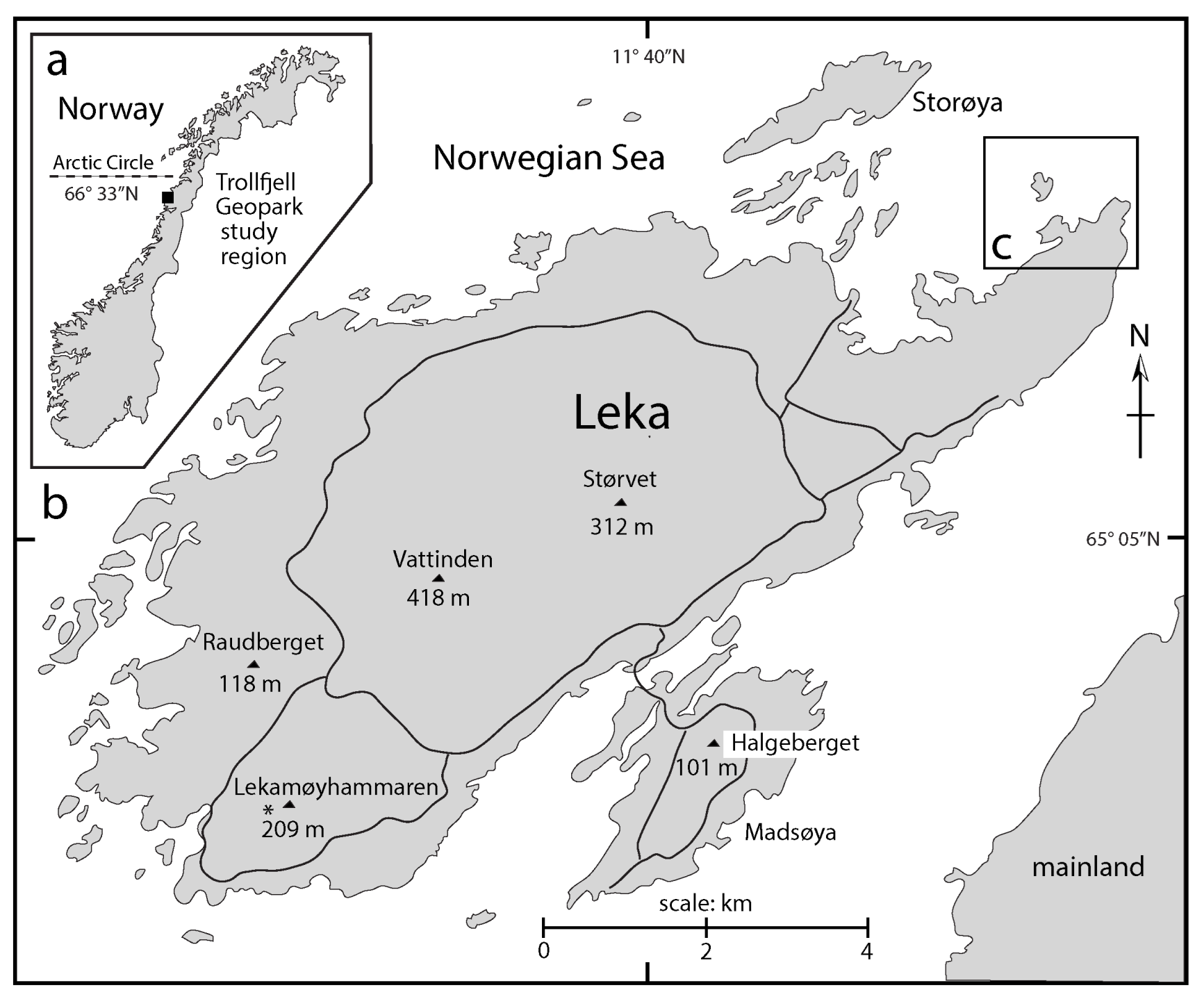

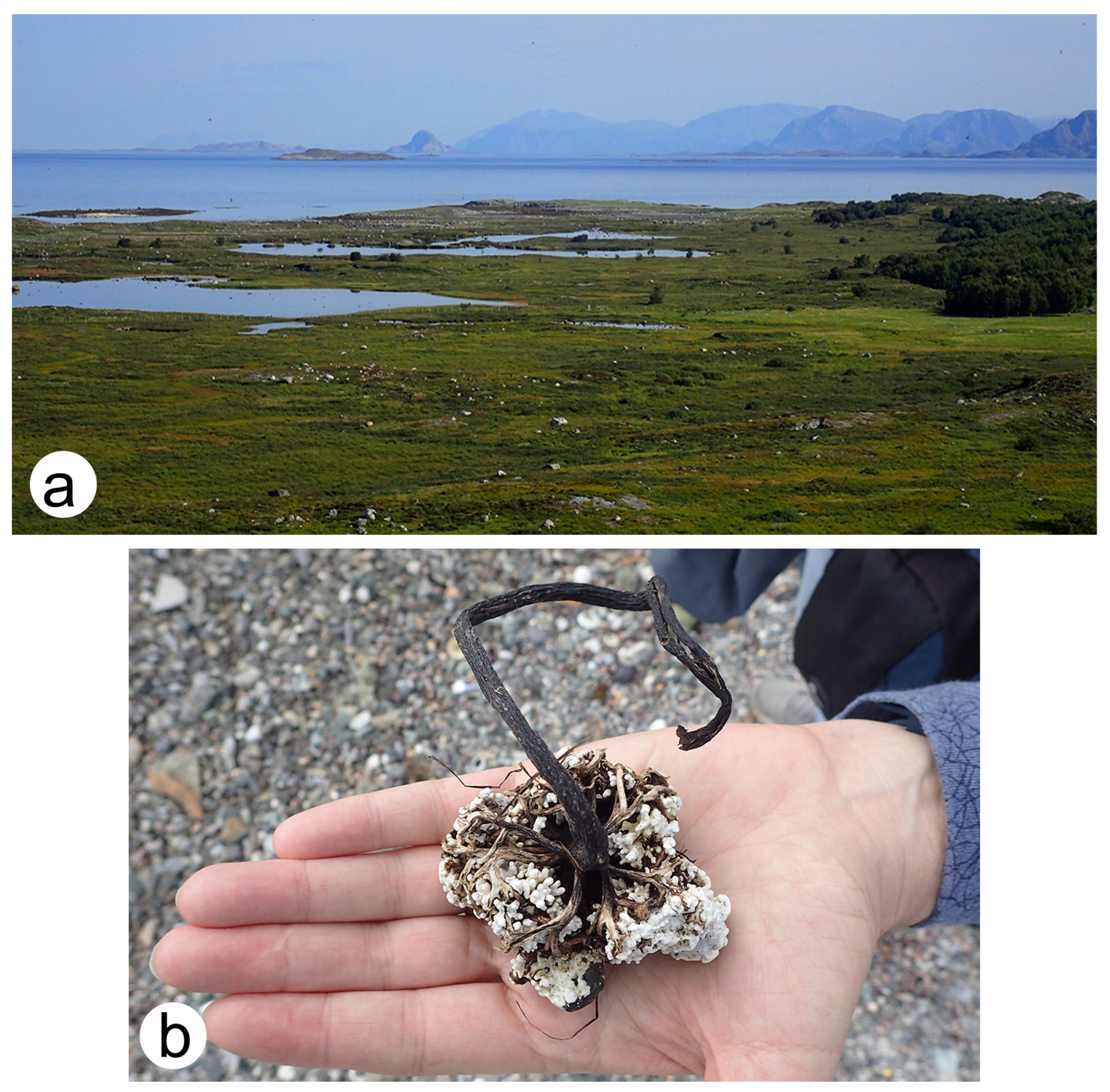

3.6. Contemporarhy Rhodoliths off the Coast of Arctic Norway and Greenland

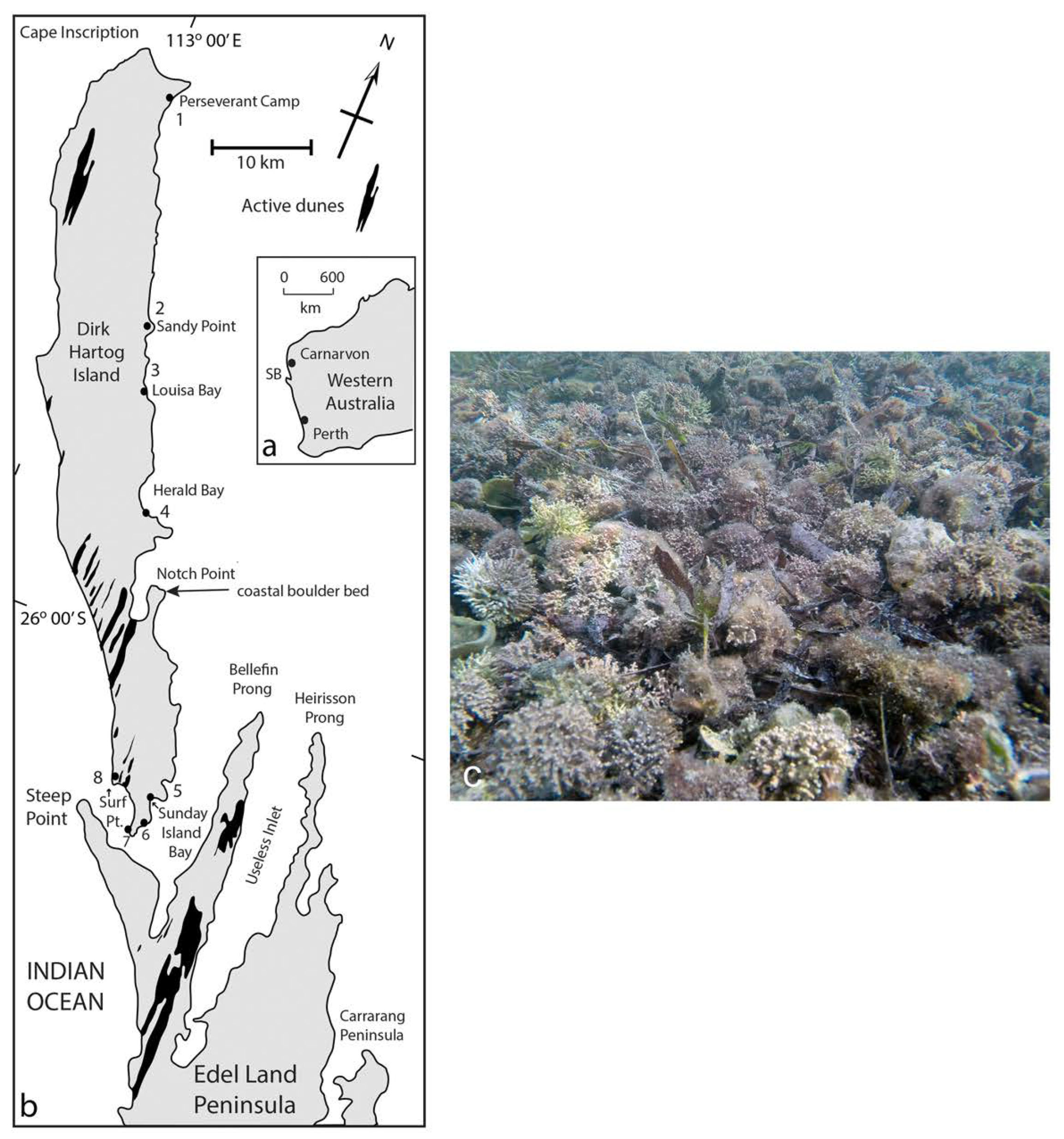

3.7. Contemporary Rhodoliths off the Coast of Western Australia

3.8. Contemporary Rhodoliths from the Ryukyu Islands of Japan

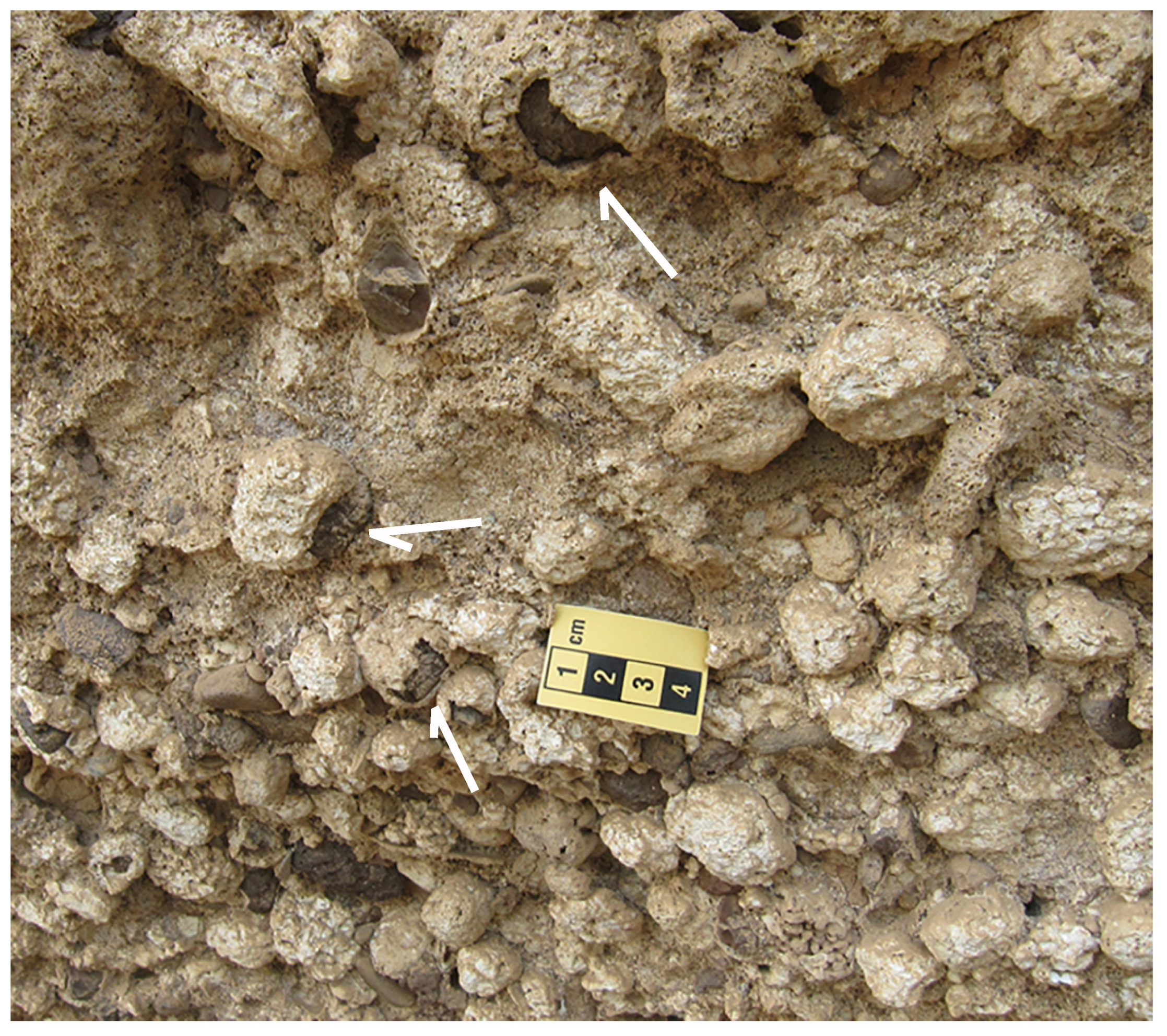

4. Major Fossil Rhodolith Deposits

4.1. Fossil Deposits from the Macaronnesian Realm in the Northeast Atlantic

4.2. Fossil Deposits from Mexico’s Baja California Peninsula

4.3. Fossil Deposits from the Western Mediterranean and Southern Europe

4.4. Fossil Deposits from New Zealand

5. Discussion

5.1. Role of Contemporary Rhodolith Flats as Biodiversity Multipliers

5.2. Role of Rhodolith Deposits to the World Economy

6. Conclusions

- Rhodoliths occur today in high concentrations on seabeds that cover parts of all continental shelves around the world, as well as the marine shelves of many oceanic islands. The latitudinal range of living rhodoliths extends from tropical settings in equatorial zones to polar zones as extreme as the Svalbard Archipelago at latitudes between N 76° and N 80°, as well as the shores of Greenland. In the Southern Hemisphere, contemporary rhodoliths are reported at a latitude of S 33.5° off the coast of South Africa.

- Rhodoliths possess an excellent fossil record that began in geological time during the Cretaceous, at least 113 million years ago. Maximum rhodolith development appears to have coincided with the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum, approximately 15 million years ago, when extensive deposits accumulated in southern Europe and around islands in today’s Western Mediterranean Sea.

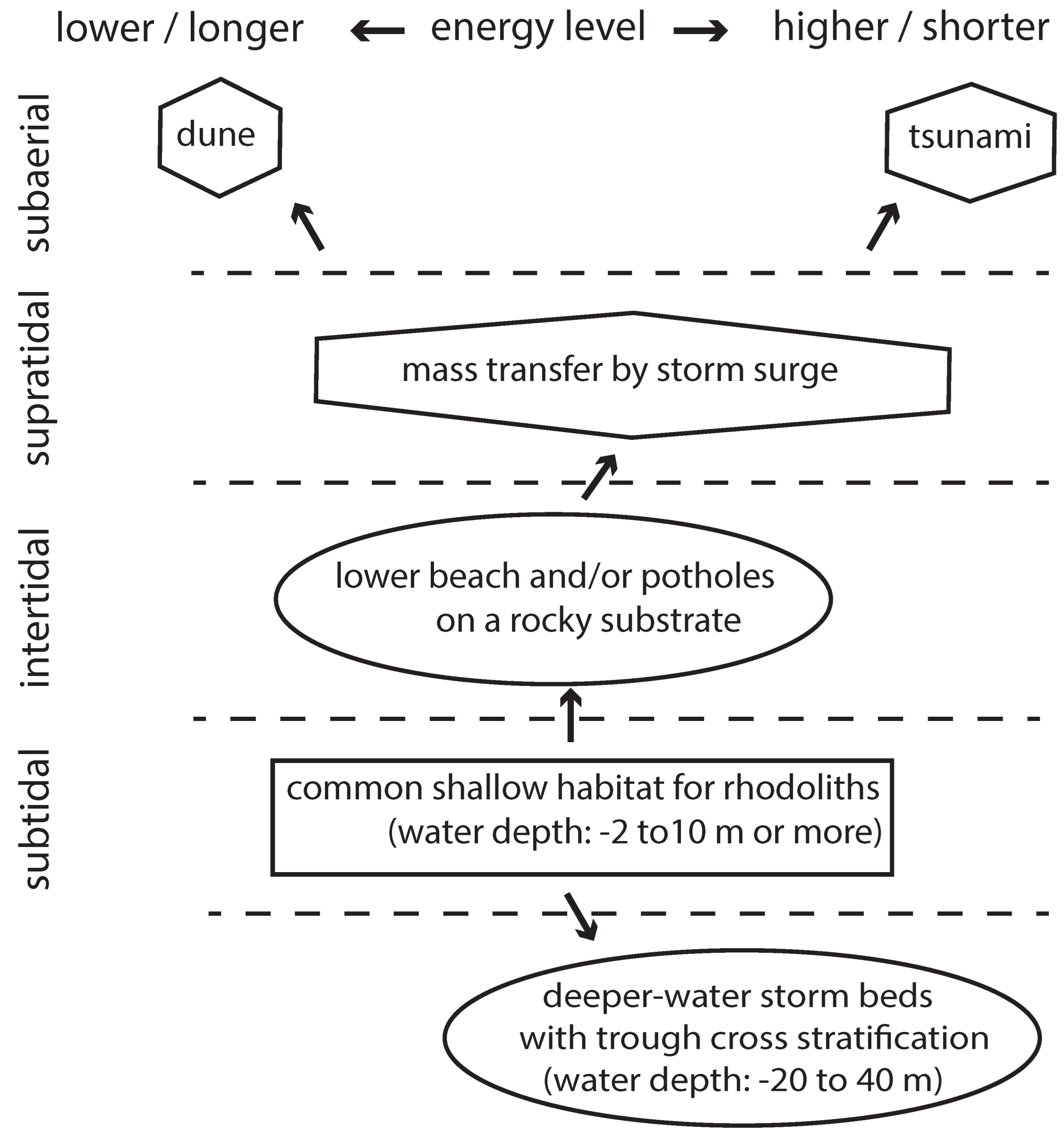

- Today and during the geologic past, rhodoliths are and were vulnerable to major sea storms capable of disturbing the seabed at a considerable depth, whereby great numbers might be pushed onto land in supratidal settings or farther offshore into deeper-water settings. Agitation of rhodoliths against one another during violent storms leads to fragmentation and the development of massive deposits of rhodolith debris. These are useful indicators of storm events. Moreover, rhodoliths in an extreme state of pulverization may contribute to beach and coastal dune deposits.

- Contemporary rhodolith beds are recognized by marine ecologists as biodiversity multipliers capable of hosting a vast number of associated invertebrates dwelling both among and embedded within individual spheroids. The role is similar to that of reef-forming corals that function as umbrella species to support a more diverse marine community. The concern among marine ecologists is that commercial exploitation for use in agriculture as lime fertilizer will lead to the destruction of an important marine ecosystem, especially in Brazil.

- The number of phycologists engaged in studies on crustose coralline algae that accrete as rhodoliths is small compared to the community of marine biologists who work on coral reefs. The same is true for paleobotanists studying fossil rhodolith deposits. Much remains to be learned, particularly in continental shelf regions of the Western Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean, as well as related oceanic islands.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elias, M.K. Fossil symbiotic algae in comparison with other fossil and living algae. Am. Midl. Nat. 1946, 36, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, S.; Goedert, J.L.; Huynh, T.L.; Krings, M.; Parkinson, D.; Romero, R.; Looy, C.V. Early Oligocene kelp holdfasts and stepwise evolution of the kelp ecosystem in the North Pacific. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e22317054121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray, J.L. Calcareous algae; Developments in Palaeontology and Stratigraphy; Elsevier Scientific Publication Co.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; 185p. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, M.S.; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.; Steller, D.L.; Woelkerling, W. Living rhodolith beds in the Gulf of California and their implications for paleoenvironmenmtal interpretations. In Pliocene Carbonates and Related Facies Flanking the Gulf of California, Baja California; Johnson, M.E., Ledesma-Vázquez, J., Eds.; Geological Society of America Special Paper; Geological Society of America: Washington, DA, USA, 1997; Volume 318, pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Amado-Filho, G.M.; Moura, R.L.; Bastos, A.C.; Francini-Filho, R.B.; Pereira-Filho, G.I.H.; Bahia, R.G.; Moraes, F.C.; Motta, F.S. Mesophotic ecosystems of the unique South Atlantic atoll are composed by rhodolith beds and scattered consolidated reefs. Mar. Biodivers. 2016, 46, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. Geological Observations on the Volcanic Islands Visited During the Voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle. Together with Some Brief Notices on the Geology of Australia and the Cape of Good Hope. Being the Second Part of the Geology of the Voyage of the Beagle, Under the Command of Capt. FitzRoy, R.N.N. During the Years 1832 to 1836; Smith, Elder & Co.: London, UK, 1844; 175p. [Google Scholar]

- Bosellini, A.; Ginsburg, R.N. Form and internal structure of recent algal nodules (rhodolites) from Bermuda. J. Geol. 1971, 79, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosence, D.W.I. Description and classification of rhodoliths (Rhodoids, Rhodolites). In Classification of Coated Grains; Peryt, T.M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1983; pp. 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, S. Charles Darwin Geologist; Cornell University Press: Ithica, NY, USA, 2005; 485p. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.E.; Baarli, B.G.; Cachão, M.; da Silva, C.M.; Ledesma-Vásquez, J.; Ramalho, R.S.; Mayoral, E.; Santos, A. Rhodoliths, uniformitarianism, and Darwin: Pleistocene and Recent carbonate deposits in the Cape Verde and Canary archipelagos. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2012, 329–330, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelkerling, W.J. The Coralline Red Algae: An Analysis of the Genera and Subfamilies of Nongeniculate Corallinacea; British Museum of Natural History Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1988; 268p. [Google Scholar]

- Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.; Nelson, W.; Aguirre, J. (Eds.) Rhodolith/Maërl Beds: A Global Perspective; Coastal Research Library 15; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; 368p. [Google Scholar]

- Adey, P.I.; Macintyre, I.G. Crustose coralline algae: A re-evaluation in the geological sciences. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1973, 84, 883–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E. Baja California’s Coastal Landscapes Revealed; University Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2021; 239p. [Google Scholar]

- Sewell, A.A.; Johnson, M.E.; Backus, D.H.; Ledesma-Vázquez, J. Rhodolith detritus impounded by a coastal dune on Isla Coronados, Gulf California. Cienc. Mar. 2007, 33, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, D.; Iryu, Y.; Nebelsick, J.H. To be or not to be a fossil rhodolith? Analytical methods for studying fossil rhodolith deposits. J. Coast. Resh. 2012, 28, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, D.; Nebelsick, J.H.; Checconi, A.; Hohenegger, J.; Iryu, Y. Present-day and fossil rhodolith pavements compared: Their potential for analyzing shallow-water carbonate deposits. Sediment. Geol. 2009, 214, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E.; Ledesma-Vázquez, J.; Ramalho, R.S.; da Silva, C.M.; Rebelo, A.C.; Santos, A.; Baarli, B.G.; Mayoral, E.; Cachão, M. Taphonomic range and sedimentary dynamics of modern and fossil rholdolith beds (North Atlantic Ocean). In Rhodolith/Maërl “Beds: A Global Perspective; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R., Nelson, W., Aguirre, J., Eds.; Coastal Research Library; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 15, pp. 221–261. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, R.; Ramalho, R.S.; Madeira, J.; Ávila, S.P.; May, S.M.; Rixhon, G.; Engel, M.; Brückner, H.; Herzog, M.; Schukraft, G.; et al. Megatsunami conglomerates and flank collapses of ocean island volcanoes. Mar. Geol. 2018, 395, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E.; Baarli, B.G.; da Silva, C.M.; Cachão, M.; Ramalho, R.S.; Santos, A.; Mayoral, E.J. Recent rhodolith deposits stranded on the windward shores of Maio (Cape Verde Islands): Historical Resource for the Local Economy. J. Coast. Res. 2016, 32, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E.; Baarli, B.G.; da Silva, C.M.; Cachão, M.; Ramalho, R.S.; Ledesma-Vázques, J.; Mayoral, E.J.; Santos, A. Coastal dunes with high content of rhodolith (coralline red algae) bioclasts: Pleistocene formations on Maio and São Nicolau in the Cape Verde archipelago. Aeolian Res. 2013, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoral, E.; Ledesma-Vázquez, J.; Baarli, B.G.; Santos, A.; Ramalho, R.; Cachão, M.; da Silva, C.M.; Johnson, M.E. Ichnology in oceanic islands: Case studies from the Cape Verde Archipelago. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2013, 381–382, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquirre, J.; Braga, J.C. Rhodolith beds in a shifting world: A palaeontological perspective. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2024, 34, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riding, R.; Braga, J.C. Halysis Hø, 1932—An Ordovician corralline red alga? J. Paleontol. 2005, 79, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichert, S. Attached and free-living crustose coralline algae and their functional traits in the geological record and today. Facies 2024, 70, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.C.; Johnson, M.E.; Rasser, M.W.; Silva, L.; Melo, C.S.; Ávila, S.P. Global biodiversity and biogeography of rhodolith-forming species. Front. Biogeogr. 2021, 13, e50646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.D.; Fox, H.E.; Allen, G.R.; Davidson, N.; Ferdaña, Z.A.; Finlayson, M.; Halpern, B.S.; Jorge, M.A.; Lombana, A.; Lourie, S.A.; et al. Marine ecoregions of the world: A bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. BioScience 2007, 57, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, L.A.; Maneveldt, G.W.; Green, A.; Karenyi, N.; Parker, D.; Samaai, T.; Kerwath, S. Rhodolith bed discovered off the South African Coast. Diversity 2020, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, A.G.; Stallard, R.F. How old is the Isthmus of Panama? Bull. Mar. Sci. 2013, 89, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarli, B.G.; Cachão, M.; Da Silva, C.M.; Johnson, M.E.; Mayoral, E.J.; Santos, A. A Middle Miocene carbonate embankment on an active volcanic slope: Ilhéu de Baixo, Madeira Archipelago, Eastern Atlantic. Geol. J. 2014, 49, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E.; Uchman, A.; Ramalho, R.S.; Martín-González, E.; Martins, G.M.; Hipólito, A.; Marques, S.; Ávila, G.C.; Madeira, P.; Doukani, M.A.; et al. Basalt sea stack and related facies from the Middle Pleistocene on Sal Island (Cabo Verde Archipelago, NE Atlantic Ocean). Facies 2025, 71, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.C.; Martín-González, E.; Melo, C.S.; Johnson, M.E.; González-Rodríguez, A.; Galindo, I.; Quartau, R.; Baptista, L.; Ávila, S.P.; Rasser, M.W. Rhodolith beds and their onshore transport in Fuerteventura Island (Canary Archipelago Spain). Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 917883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.C.; Johnson, M.E.; Quartau, R.; Rasser, M.W.; Melo, C.S.; Neto, A.L.; Temera, R.; Madeira, P.; Ávila, S.P. Modern coralline algal nodules from the insular shelf of Pico in the Azores (northeast Atlantic Ocean). Estuauraine Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 210, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amando-Filho, G.M.; Moura, R.L.; Bastos, A.C.; Salgado, L.T.; Sumida, P.Y.; Guth, A.Z.; Francini-Filho, R.B.; Pereira-Filho, G.H.; Abrantes, D.P.; Brasileiro, P.S.; et al. Rhodolith beds are major CaCO3 bio-factories in the tropical South West Atlantic. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomar, L.; Morsilli, M.; Hallock, P.; Bádenas, B. Internal waves, an under-explored source of turbulence events in the sedimentary record. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2012, 111, 56–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, M.C.; Villas-Boas, A.; Rodriguez, R.R.; Figueiredo, M.A.O. New records of rhodolith-forming species (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) from deep water in Espírito Santo State, Brazil. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2012, 66, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahia, R.G.; Abranttes, D.P.; Brasileiro, P.S.; Pereora-Filho, G.H.; Amado-Filho, G.M. Rhodolith bed structure along a depth gradient on the northern coast of Bahia State, Brazil. Braz. J. Oceanog. 2010, 58, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Filho, G.H.; Amado-Filho, G.M.; de Moura, R.L.; Bastos, A.C.; Guimaraes, S.M.P.B.; Salgado, L.T.; Fracinia-Filho, R.B.; Bahia, R.G.; Abrantes, D.P.; Guth, A.Z.; et al. Extensive rhodolith beds over the summits of southwestern Atlantic Ocean seamounts. J. Coast. Res. 2012, 28, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Filho, G.M.; Pereira-Filho, G.H.; Bahia, R.G.; Abrantes, D.P.; Veras, P.C.; Matheus, Z. Occurrence and distribution of rhodolith beds on the Fernando de Noronha Archipelago of Brazil. Aquat. Bot. 2022, 101, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.H.; Wilson, P.A.; Lugo-Fernández, A. Biologic and geologic responses to physical processes: Examples from modern reef systems of the Caribbean-Atlantic region. Cont. Shelf Res. 1992, 12, 809–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantine, D.L.; Bowden-Kerby, A.; Aponte, N.E. Cruoriella rhodoliths from shallow-water back reef environments in La Parguera Puerto Rico (Caribbean Sea). Coral Reefs 2000, 19, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma-Vázquez, J.; Johnson, M.E.; Gonzalez-Yajimovich, O.; Santamaria-del-Angel, E. Gulf of California geography, geological origins, oceanography and sedimentation patterns. In Atlas of Coastal Ecosystems in the Western Gulf of California; Johnson, M.E., Ledesma-Vázquez, J., Eds.; University Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Steller, D.L.; Foster, M.S. Environmental factors influencing distribution and morphology of rhodoliths in Bahía Concepción, BCS, México. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1995, 194, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrack, E.C. The relationship between water motion and living rhodolith beds in the southwestern Gulf of California, Mexico. Palaios 1999, 14, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnico, L.A.; Foster, M.S.; Steller, D.L.; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R. Population biology of a long-lived rhodolith: The consequences of becoming old and large. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2014, 504, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steller, D.L.; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.; Foster, M.S. Living rhodolith bed ecosytems in the Gulf of California. In Atlas of Coastal Ecosystems in the Western Gulf of California; Johnson, M.E., Ledesma-Vázquez, J., Eds.; University Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2009; pp. 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Halfar, J.; Eisele, M.; Riegl, B.; Hetzinger, S.; Godinez-Orta, L. Modern rhodolith-dominated carbonates at Punta Chivato, Mexico. Geodiversitas 2012, 34, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.; López-Calderón, J.M.; Mariano-Meléndez, E.; Sánchez-Rodrígues, A.; Fernández-Garcia, C. Size and distribution of rhodolith beds in the Loreto Marine Park: Their role in coastal processes. J. Coast. Res. 2012, 28, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetzinger, S.; Halfar, J.; Riegl, B.; Godinez-Orta, L. Sedimentology and acoustic mapping of modern rhodolith facies on a non-tropical carbonate shelf (Gulf of California, Mexico). J. Sediment. Res. 2006, 76, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkett, D.A.; Maggs, C.A.; Dring, M.J. Maerl: An overview of dynamic and sensitivity characteristics for conservation management of marine SCAs. Scott. Assoc. Mar. Sci. 1998, 5, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Kamenos, N.A.; Law, A. Temperature controls on coralline algal skeletal growth. J. Phycol. 2009, 46, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenos, N.A.; Moore, P.G.; Hall-Spencer, J.M. Nursery-area function of maerl grounds for juvenile queen scallops Aequipecten opercularis and other invertebrates. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004, 274, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backus, D.H. Contemporary issues and advancements in coastal eolianite research. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiwwald, A. Sedimentological and biological aspects in the formation of branched rhodoliths in northern Norway. Beir. Paläont. 1995, 20, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Teichert, S.; Woelkerling, W.; Rüggeberg, A.; Wisshak, M.; Piepenburg, D.; Meyerhöfer, M.; Form, A.; Freiwald, A. Arctic rhodolith beds and their environmental controls (Spitsbergen, Norway). Facies 2014, 60, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensbye, H.I.; Halfar, J. Overview of coralline red algal crusts and rhodolith beds (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) and their possible ecological importance in Greenland. Polar Biol. 2017, 40, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.S.; Harvey, R.M.; Merton, E. The distribution significance and vulnerability of Australian rhodolith bds: A review. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2017, 68, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landing, E.; Johnson, M.E. Stromatolites and their “kin”as living microbialites in contemporary settings linked to a long fossil record. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.; Johnson, M.E.; Harvey, R. Heterozoan carbonate enriched beach sand and coastal dunes: Dirk Hartog Island, Shark Bay, Western Australia. Facies 2018, 64, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iryu, Y.; Nakamori, T.; Matsuda, S.; Abe, O. Distribution of marine organisms and its geological significance in the modern reef complex of the Ryukyu Islands. Sediment. Geol. 1995, 99, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuda, S.; Iryu, Y. Rhodloliths from deep fore-reef to shelf areas around Okinawa-jima, Ryukyu Islands, Japan. Mar. Geol. 2011, 282, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.C.; Uchman, A.; Johnson, M.E.; Melo, C.S.; Vegas, J.; Galindo, I.; Mayoral, E.J.; Santos, A.; González-Rodríguez, A.; Afonso-Carrillo, J.; et al. Rhodoliths and trace fossils record stabilization of a fan-delta system: An example from the Mio-Pliocene deposits of Gran Canaria (Canary Islands, Spain). J. Paleogeog. 2025, 14, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E.; da Silva, C.M.; Santos, A.; Baarli, B.G.; Cachão, M.; Mayoral, E.J.; Rebelo, A.C.; Ledesma-Vázquez, J. Rhodolith transport and immobilization on a volcanically active rocky shore: Middle Miocene at Cabeço das Laranjas on Ilhéu de Cima (Madeira Archipelago Portugal. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2011, 300, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.C.; Rasser, M.W.; Kroh, A.; Johnson, M.E.; Ramalho, R.S.; Melo, C.; Uchman, A.; Berning, B.; Silva, L.; Zanon, V.; et al. Rocking around a volcanic island shelf: Pliocene rhodolith beds from Malbusca, Santa Maria Island (Azores, NE Atlantic). Facies 2016, 62, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E.; Backus, D.H.; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R. Contribution of rhodoliths to the generation of Pliocene-Pleistocene limestone in the Gulf of California. In Atlas of Coastal Ecosystems in the Western Gulf of California; Johnson, M.E., Ledesma-Vázquez, J., Eds.; University Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2009; pp. 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma-Vázquez, J.; Johnson, M.E.; Backus, D.H.; Mirabal-Davila, C. Coastal evolution from transgressive barrier deposit to marine terrace on Isla Coronados, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Cienc. Mar. 2007, 33, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eros, J.M.; Johnson, M.E.; Backus, D.H. Rocky shores and development of the Pliocene-Pleistocene Arroyo Blanco Basin on Isla Carmen in the gulf of California Mexico. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2006, 43, 1149–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emhoff, K.F.; Johnson, M.E.; Backus, D.H.; Ledesma-Vázquez, J. Pliocene stratigraphy at Paredones Blancos: Significance of a massive crushed-rhodolith deposit on Isla Cerralvo Baja California Sur (Mexico). J. Coast. Res. 2012, 28, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.E.; Hayes, M.L. Dichotomous facies on a Late Cretaceous rocky island as related to wind and wave patterns (Baja California, Mexico. Palaios 1993, 8, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, J.C.; Bassi, D. Neogene history of Sporolithon Heydrich (Corallnales Rhodphyta) in the Mediterranean region. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2007, 243, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomar, L. Ecological control of sedimentary accommodation: Evolution from a carbonate ramp to rimmed shelf Upper Miocene Balearic Islands. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2001, 175, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandano, M.; Vannucci, G.; Pomar, L.; Obrador, A. Rhodolith assemblages from the lower Tortonian carbonate ramp of Menorca (Spain): Environmental and paleoclimatic implications. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2005, 226, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, J.; Braga, J.; Martín, J. Algal nodules in the Upper Pliocene deposits at the coast of Cadiz (S Spain). In Studies on Fossil Benthic Algae; Barattolo, F., De Castro, P., Parente, M., Eds.; Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana: Modena, Italy, 1993; Volume 1, pp. 1–7. ISBN 9788870002171. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre, J.; Braga, J.C.; Martín, J.M.; Betzler, C. Palaeoenvironmental and stratigraphic significance of Pliocene rhodolith beds and coralline algal bioconstructions from the Caroneras Basin (SE Spain). Geodiversitas 2012, 34, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checconi, A.; Bassi, D.; Passeri, L.; Rettori, R. Corallline red algal assemblage from the Middle Pliocene shallow-water temperate carbonates of the Monte Cetona (Northrn Apennines Italy). Facies 2007, 53, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checconi, A.; Bassi, D.; Monaco, P.; Carannante, G. Re-deposited rhodoliths in the Middle Miocene hemipelagic deposits of Vitulano (Southern Apennines, Italy): Coralline assemblage characterization and related trace fossils. Sediment. Geol. 2020, 225, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletti, G.; Basso, D.; Frixa, A.; Corselli, C. Transported rhodoliths witness the lost carbonate factory: A case history from the Miocene Pietra da Cantoni limestone (NW Italy). Riv. Ital. Paleontol. Stratigr. 2015, 121, 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Bassi, D. Larger foraminiferal and coralline algal facies in an Upper Eocene storm-influenced, shallow-water carbonate platform (Colli Berici, north-eastern Italy). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2005, 226, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzhauser, M.; Landau, B.; Mandic, O.; Neubauer, T.A. The Central Paratethys Sea–Part of the tropical eastern Atlantic rather than gate into the Indian Ocean. Glob. Planet. Change 2024, 243, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshammer, B.; Uhlir, C.; Rohatsch, A.; Unterwurzacher, M. Adnet ‘Marble’, Untersberg ‘Marble’ and Leitha Limestone—Best examples expressing Austria’s physical cultural heritage. In Engineering Geology for Society and Territory; Lollino, G., Manconi, A., Guzzetti, F., Culshaw, M., Bobrowsky, P., Luino, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 5, pp. 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Coletti, G.; Basso, D.; Frixa, A. Economic importance of coralline carbonates. In Rhodolith/Maërl Beds: A Global Perspective; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R., Nelson, W., Aguirre, J., Eds.; Coastal Research Library; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Nalin, R.; Nelson, C.S.; Basso, D.; Massari, F. Rhodolith-bearing limestones as transgressive marker beds; fossil and modern examples from North Island New Zealand. Sedimentology 2008, 55, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, N.; Magris, R.A.; Berchez, F.; Bernardino, A.F.; Ferreira, C.E.; Francini-Filho, R.B.; Gaspar, T.L.; Pereira-Filho, G.H.; Rossi, S.; Silva, J.; et al. Rhodolith beds in Brazil—A Natural Heritage in need of Conservation. Divers. Distrib. 2025, 31, e13960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintra-Buenrostro, C.E.; Foster, M.S.; Meldahl, K.H. Response of nearshore marine assemblages to global change: A comparison of molluscan assemblages in Pleistocene and modern rhodolith beds in the southwestern Gulf of California, México. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2002, 183, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steller, D.L.; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.; Foster, M.S.; Roberts, C.A. Rhodolith bed diversity in the Gulf of California: The importance of rhodolith structure and consequences of disturbance. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2003, 13, S5–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Los Ángles Carvajal, M.; Robles, A.; Ezcurra, E. Ecological conservation in the Gulf of California. In The Gulf of California Biodiversity and Conservation; Brusca, R.C., Ed.; University Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2010; pp. 219–250. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, C.; Bordehore, C.; Borg, J.A.; Glémarec, M.; Grall, J.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; De La Huz, C.H.; Lanfranco, E.; Lastra, M.; Moore, P.G.; et al. Conservation and management of northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean maerl beds. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2003, 13, S65–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S. Ecology of coralline red algae and their fossil evidences from India. Thalassas 2016, 33, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabone, L.; Knittweis, L.; Aguilar, R.; Alvarez, H.; Borg, J.A.; Garcia, S. Habitat characterization, anthropogenic impacts and conservation of rhodolith beds off southeastern Malta. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2024, 34, e4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Johnson, M.E. Rhodoliths as Global Contributors to a Carbonate Ecosystem Dominated by Coralline Red Algae with an Established Fossil Record. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020169

Johnson ME. Rhodoliths as Global Contributors to a Carbonate Ecosystem Dominated by Coralline Red Algae with an Established Fossil Record. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(2):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020169

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnson, Markes E. 2026. "Rhodoliths as Global Contributors to a Carbonate Ecosystem Dominated by Coralline Red Algae with an Established Fossil Record" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 2: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020169

APA StyleJohnson, M. E. (2026). Rhodoliths as Global Contributors to a Carbonate Ecosystem Dominated by Coralline Red Algae with an Established Fossil Record. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(2), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020169