Study on Hydrodynamics and Water Exchange Capacity in the Changhai Sea Area Based on the FVCOM Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

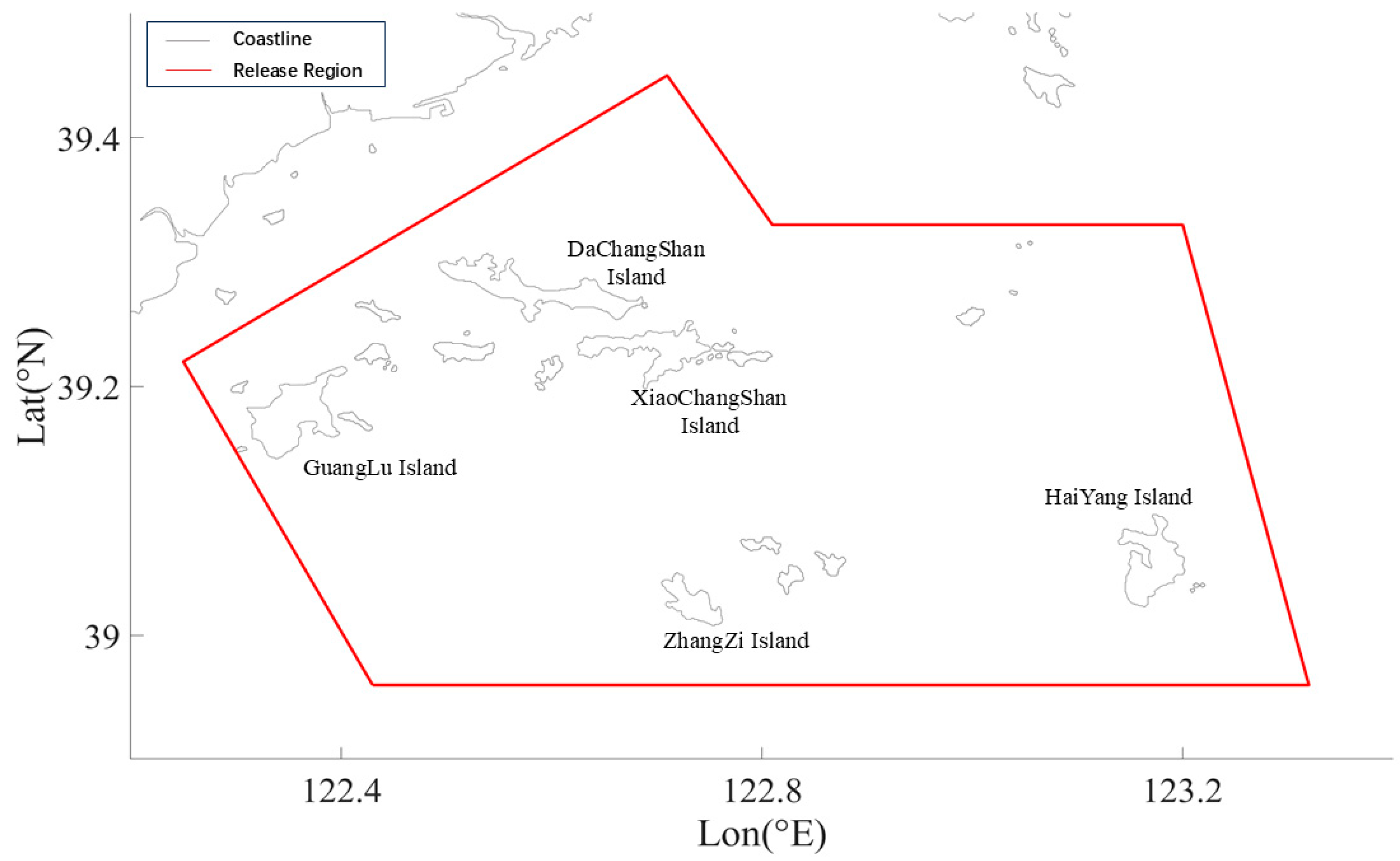

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Overview

2.2. Model Configuration

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Validation

3.1.1. Tide Level Validation

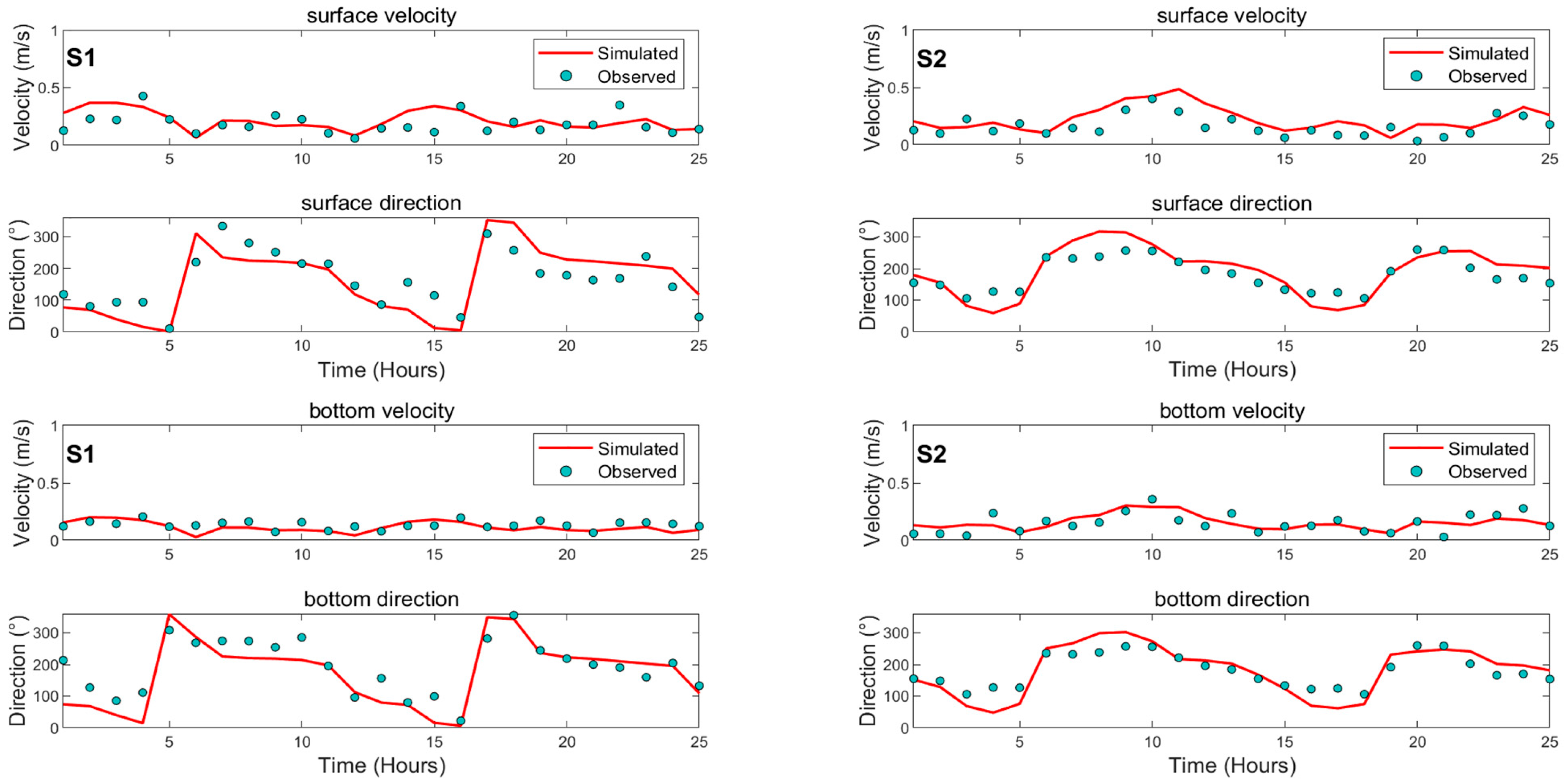

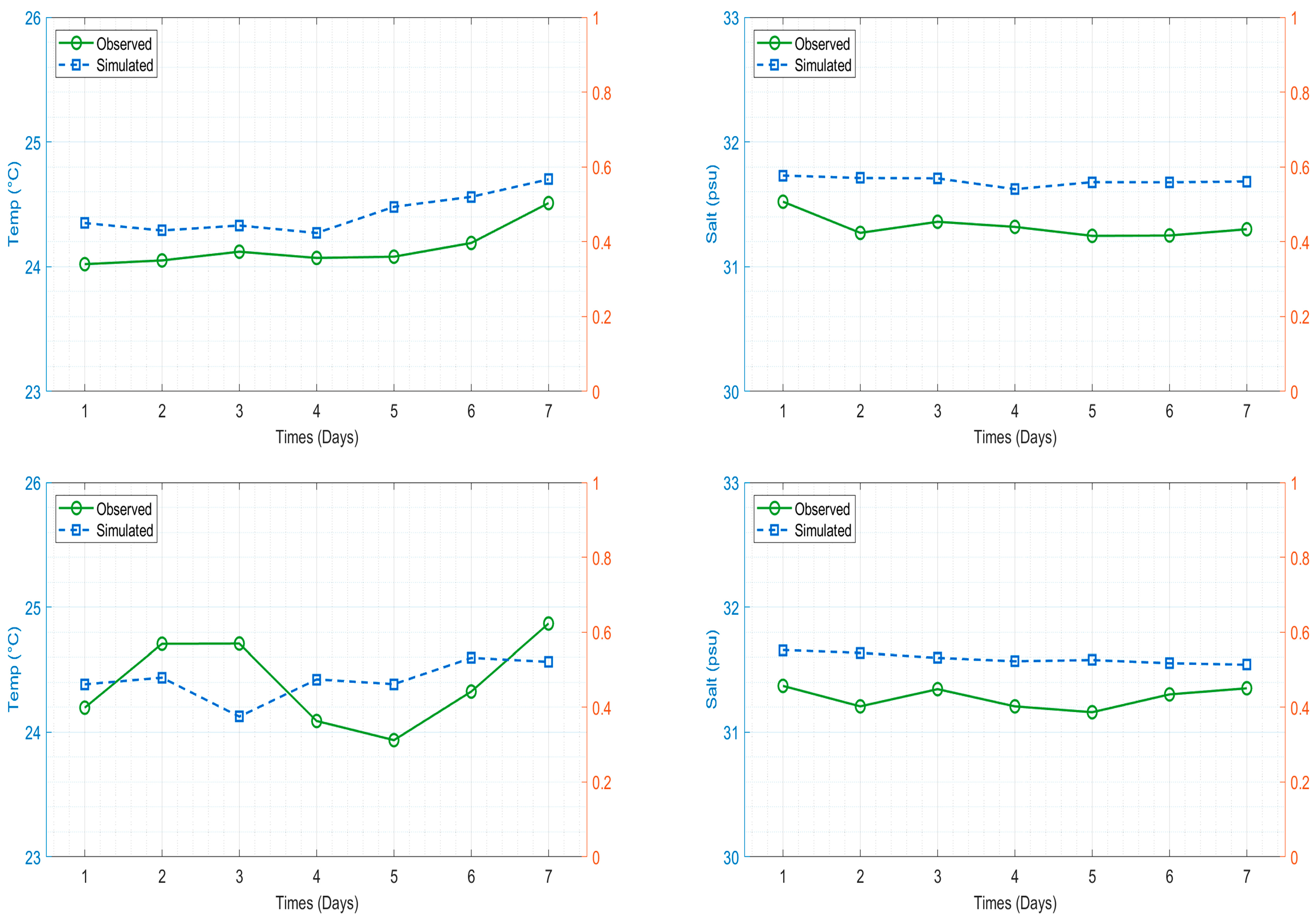

3.1.2. Verification of Tidal Currents and Temperature–Salinity

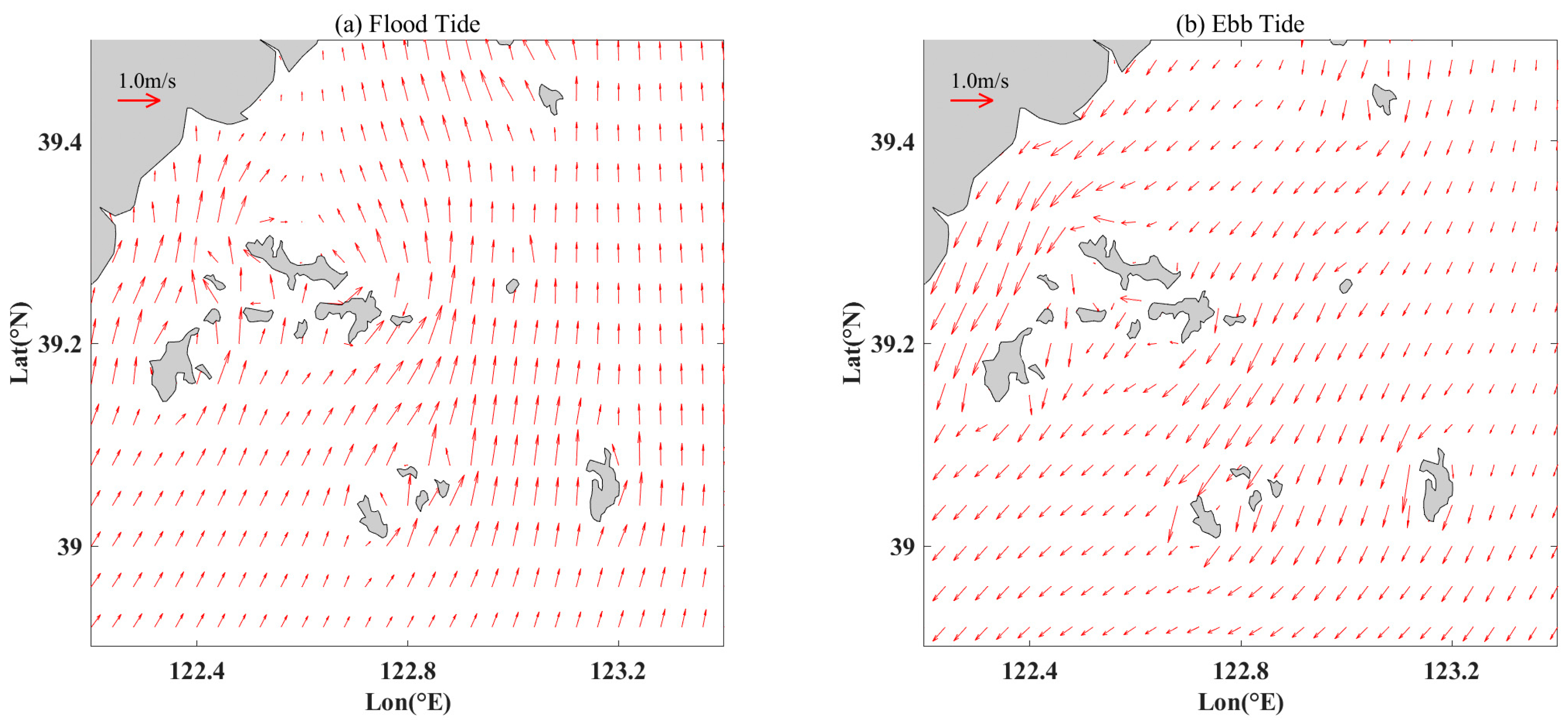

3.1.3. Analysis of Tidal Field Results

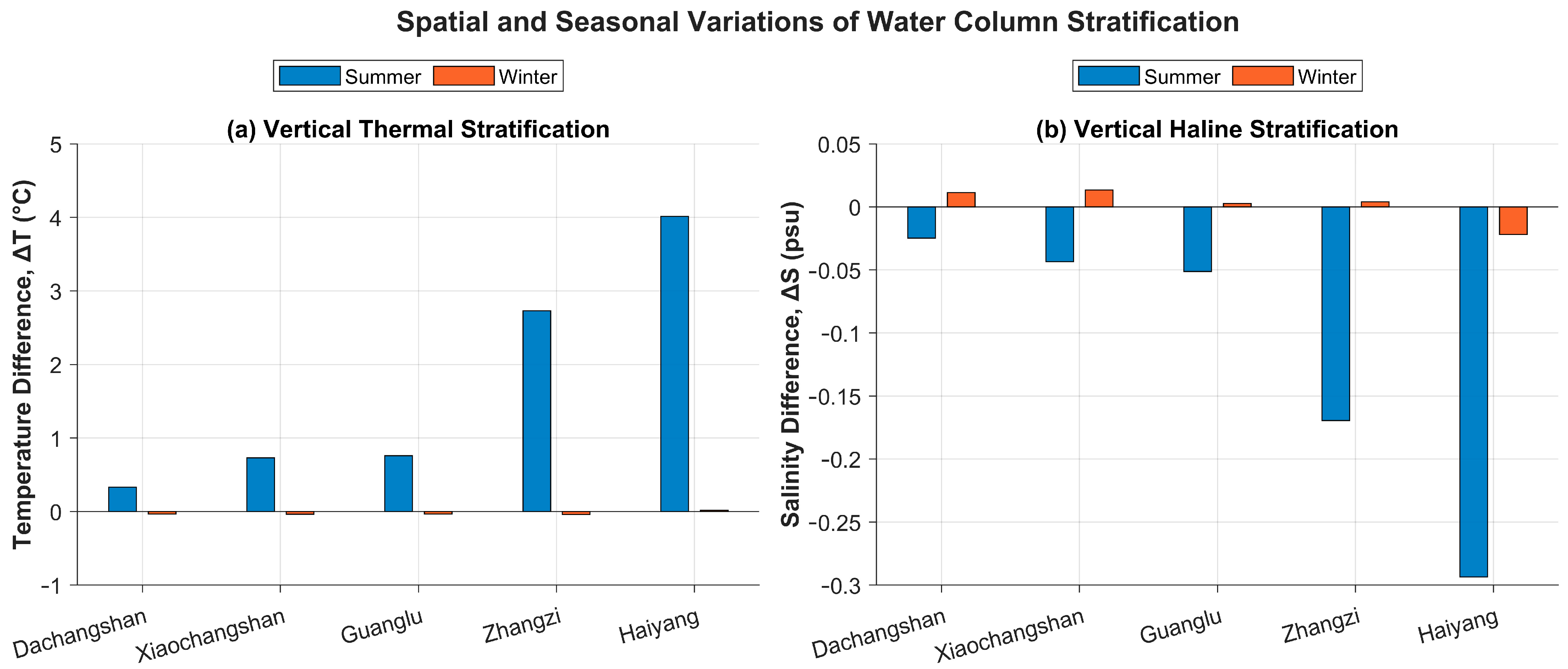

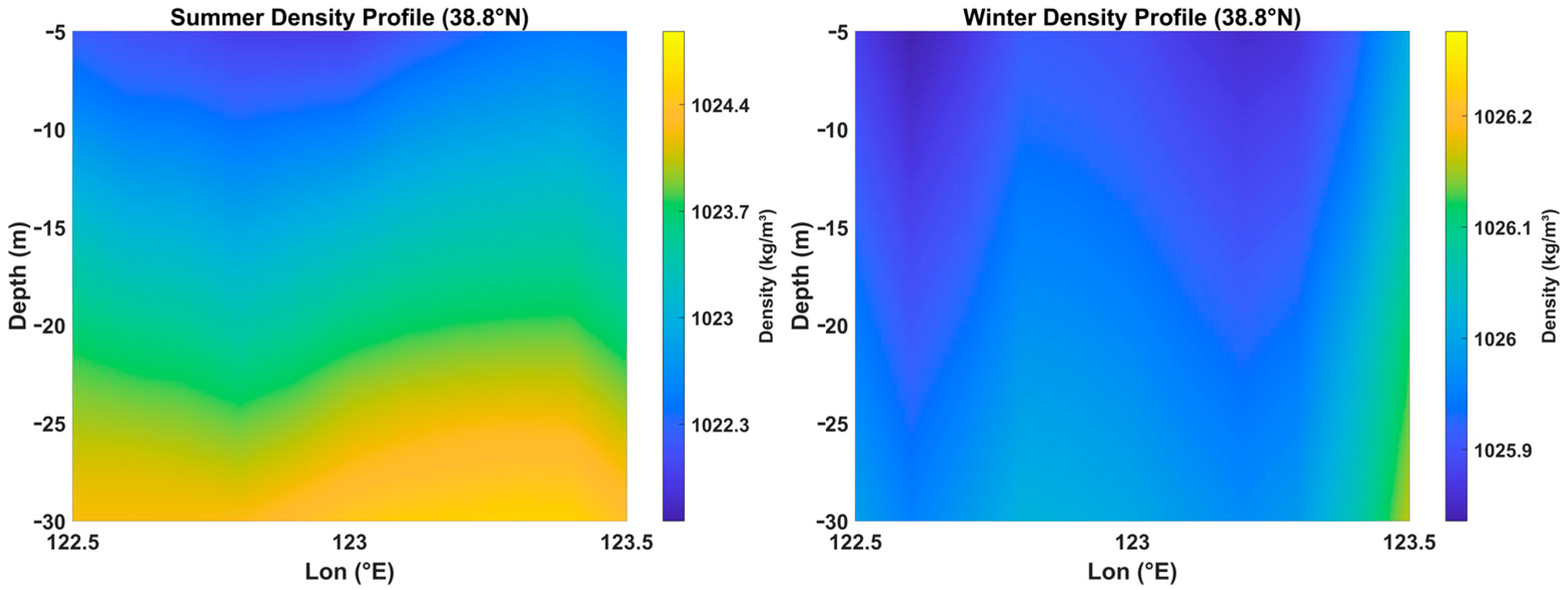

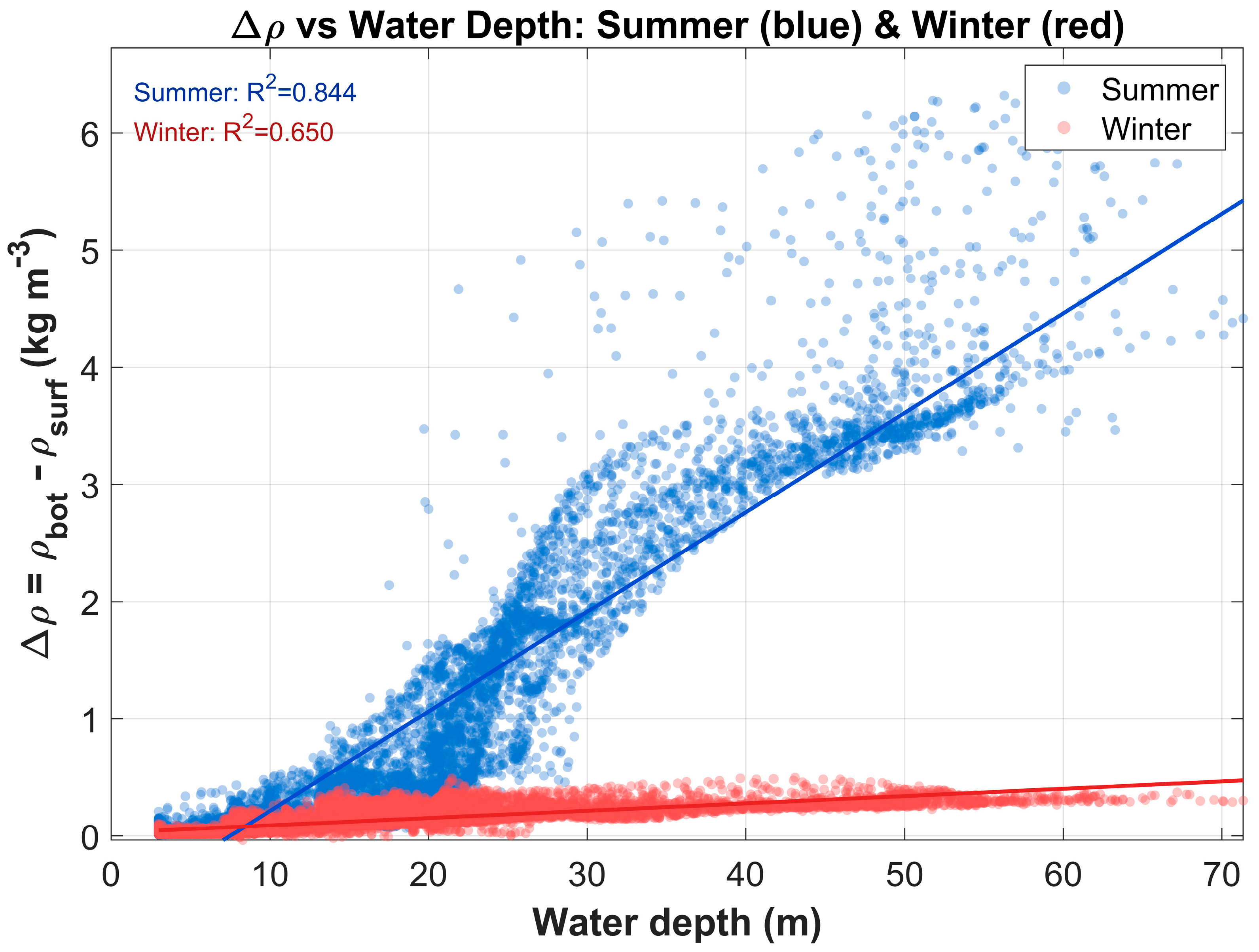

3.2. Seasonal and Spatial Patterns of Vertical Stratification

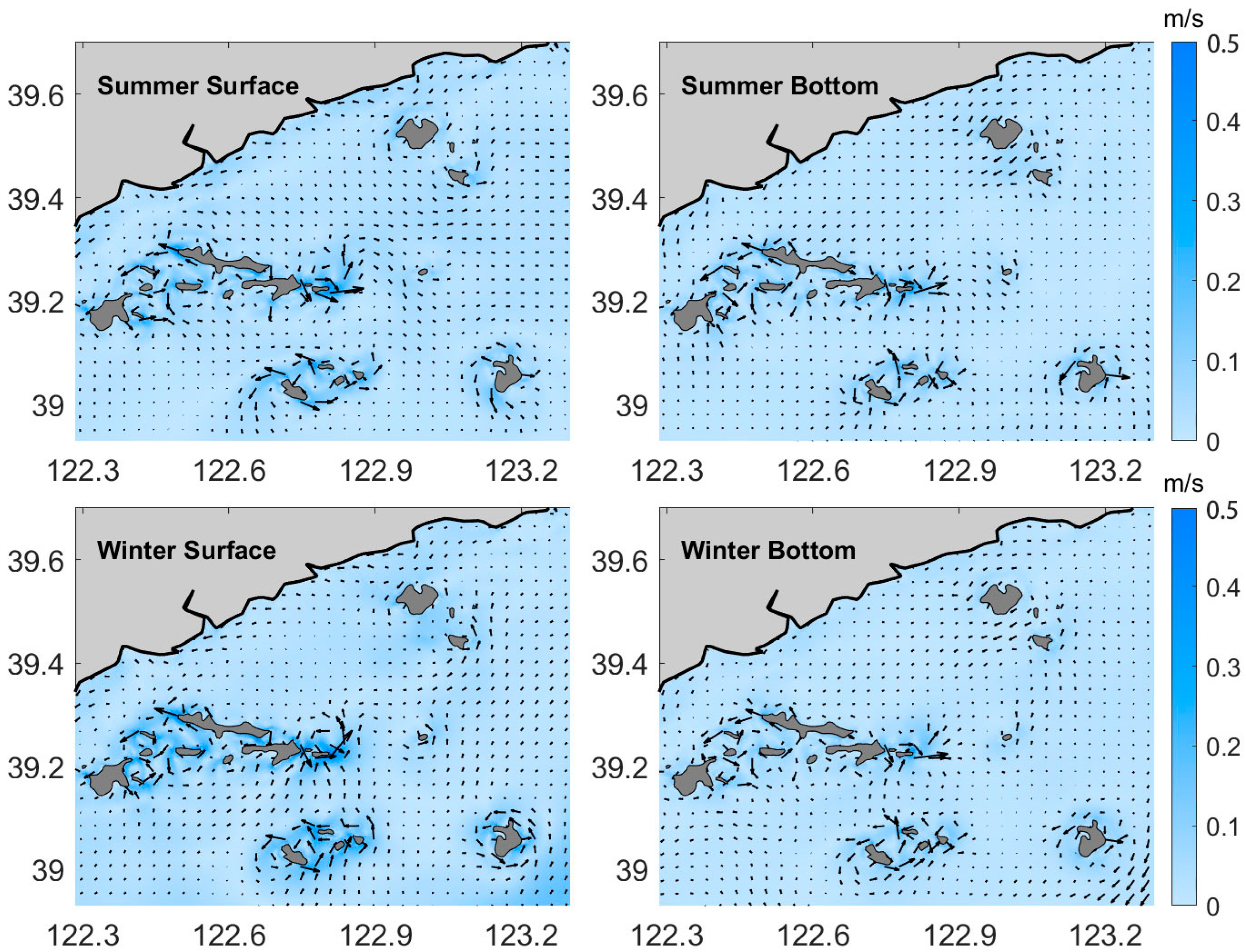

3.3. Eulerian Residual Currents

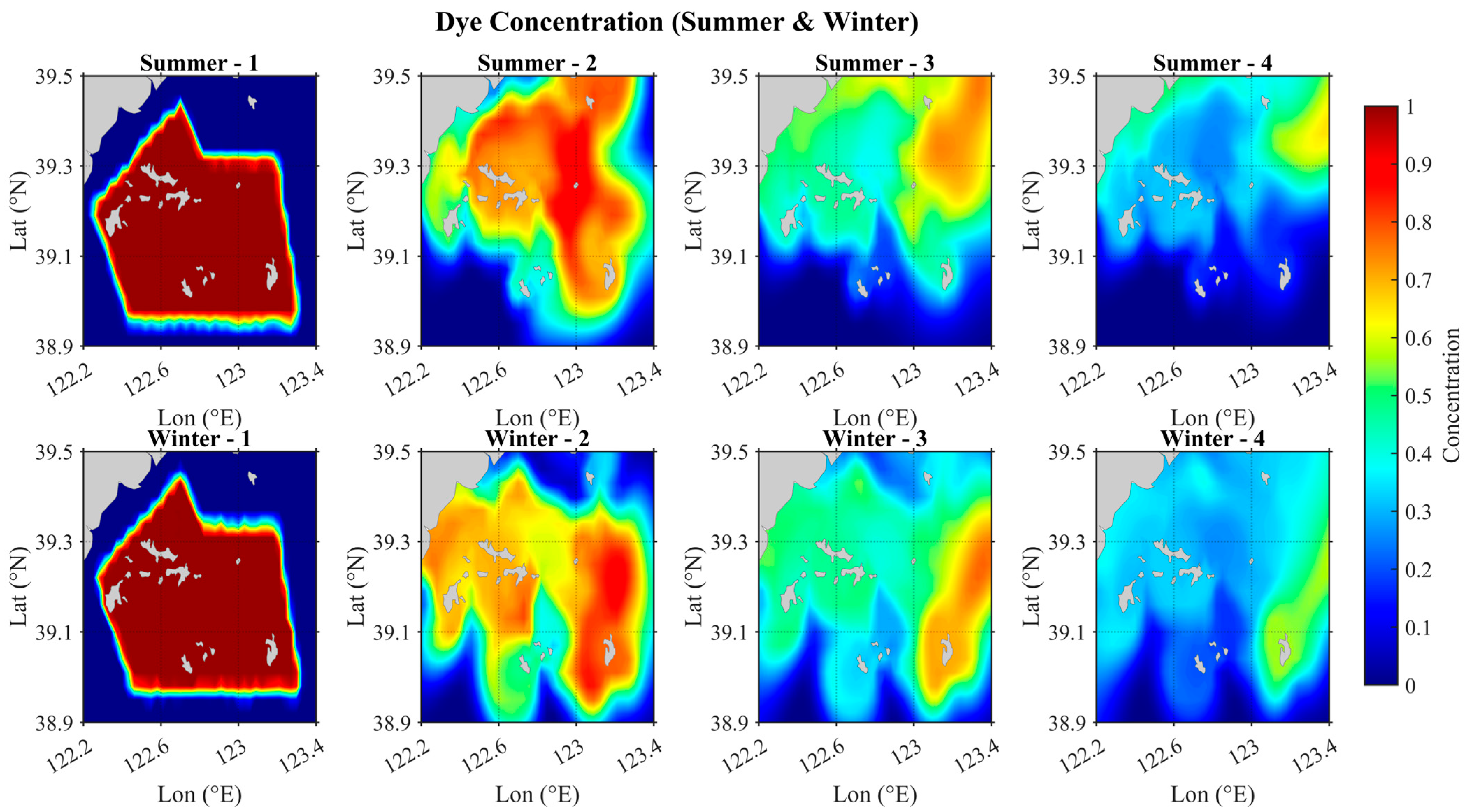

3.4. Concentration Diffusion Distribution

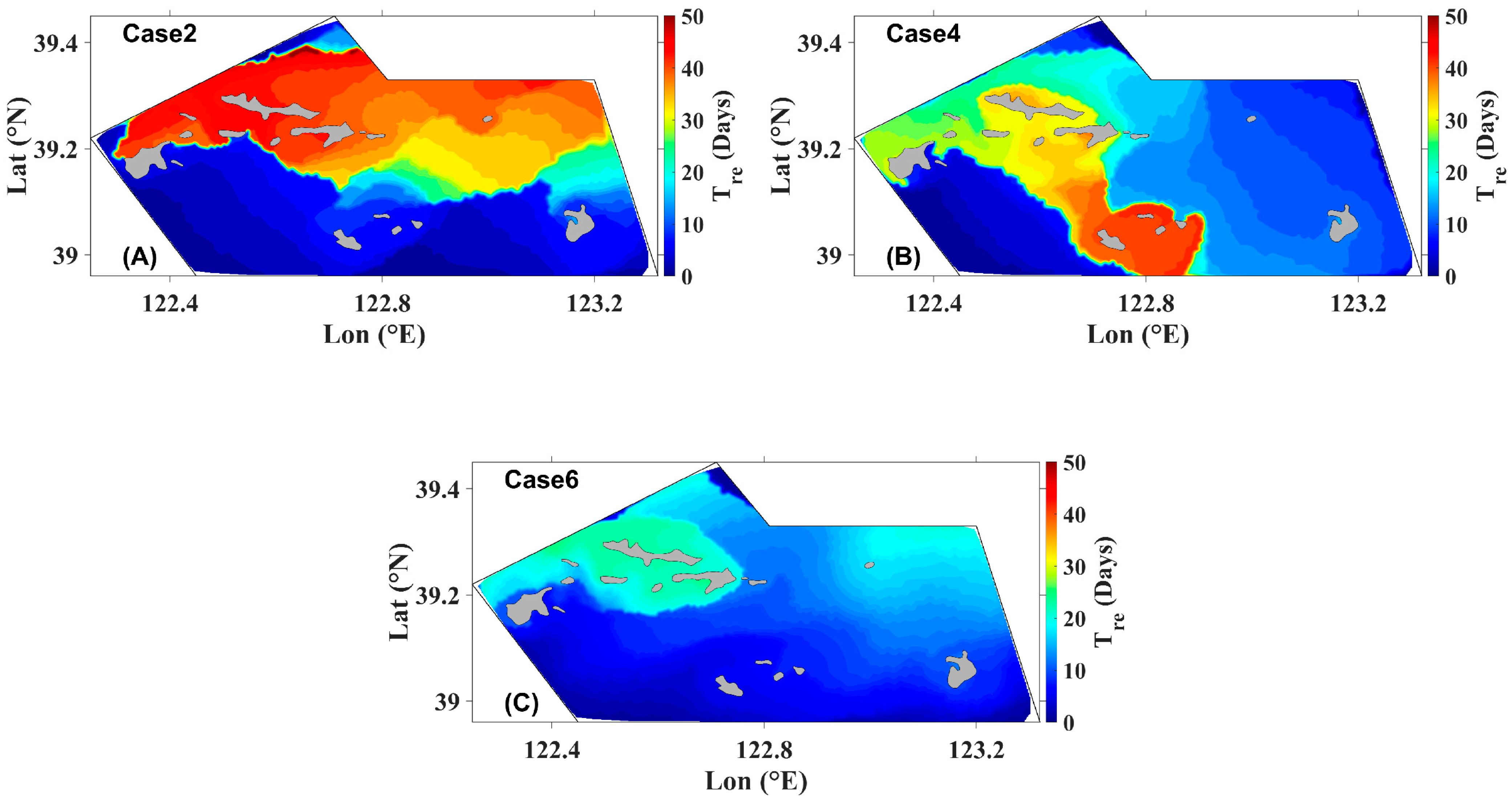

3.5. Residence Time Distribution and Mechanisms

3.5.1. Summer Residence Time Analysis

3.5.2. Winter Residence Time Analysis

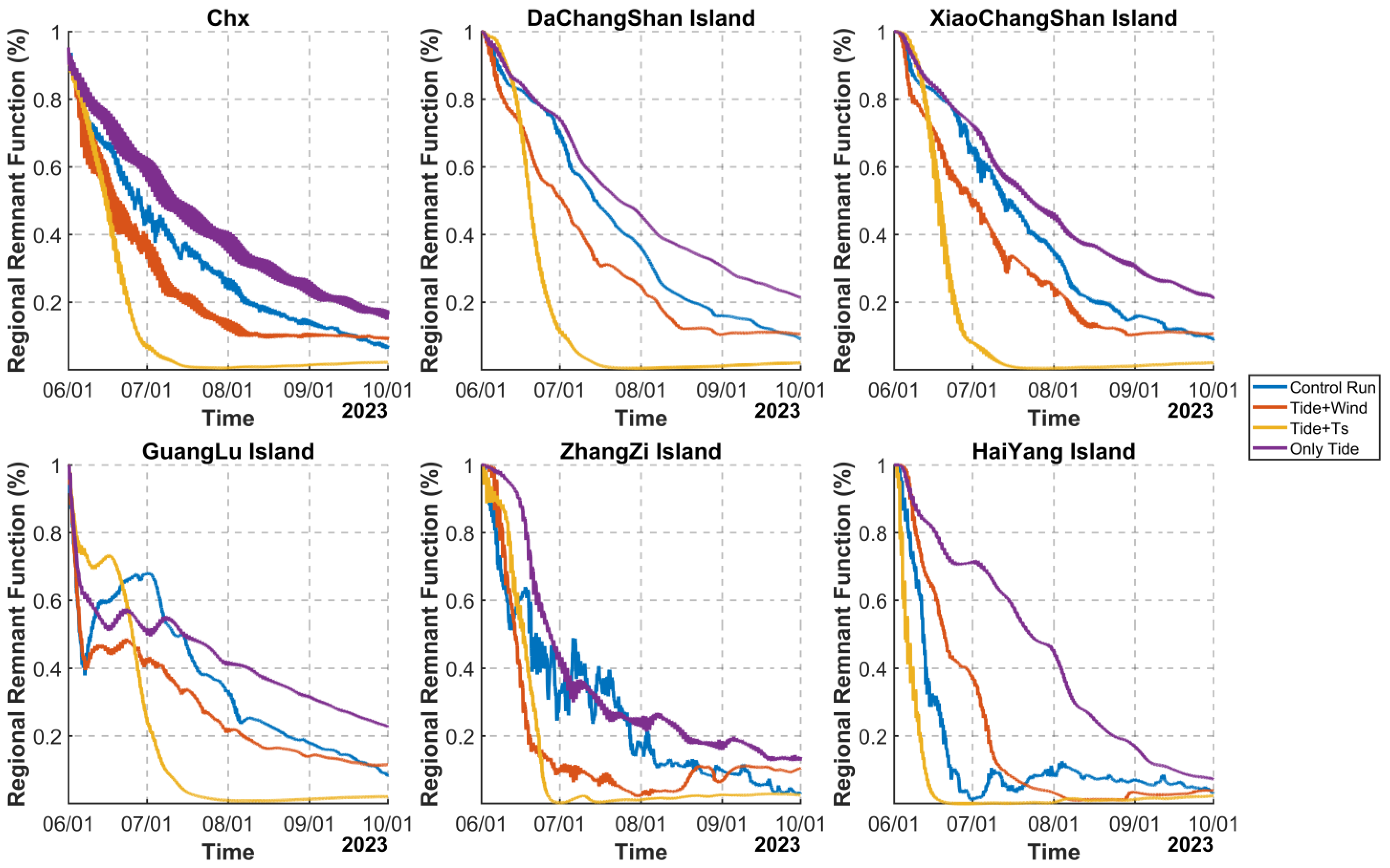

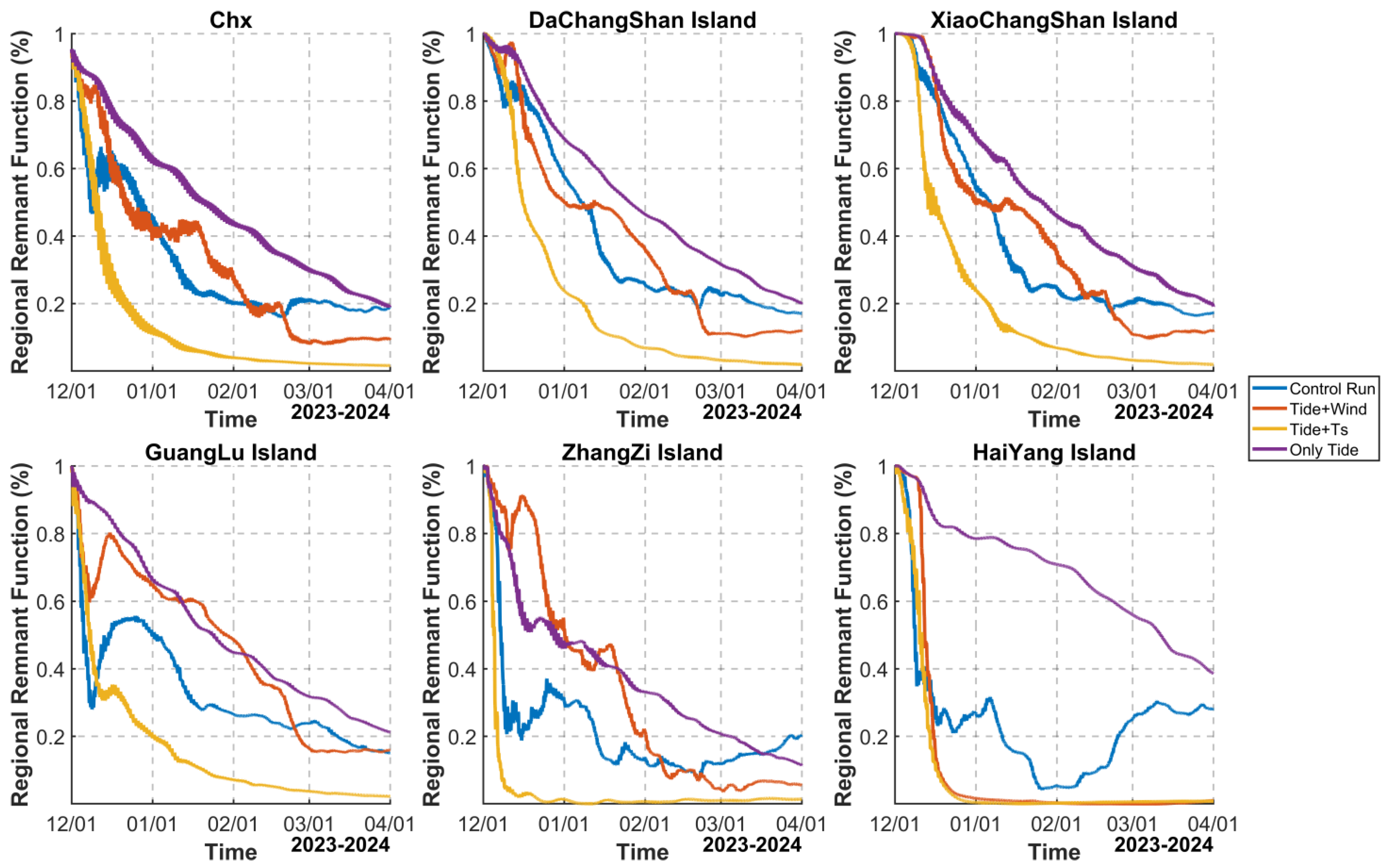

3.6. Regional Concentration Variations

3.6.1. Summer

3.6.2. Winter

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Takeoka, H. Fundamental Concepts of Exchange and Transport Time Scales in a Coastal Sea. Cont. Shelf Res. 1984, 3, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Xing, C.; Yu, J.; Ma, Y.; Shi, W.; Lv, X. Wave Effects on Water Exchange Capacity in the Dalian Bay: A Numerical Study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, C. Impact of Large-Scale Reclamation on Hydrodynamics and Flushing in Victoria Harhour, Hong Kong. J. Coast. Res. 2013, 29, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsen, N.E.; Cloern, J.E.; Lucas, L.V.; Monismith, S.G. A Comment on the Use of Flushing Time, Residence Time, and Age as Transport Time Scales. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2002, 47, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucco, A.; Umgiesser, G. Modeling the Venice Lagoon Residence Time. Ecol. Model. 2006, 193, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeoka, H. Exchange and Transport Time Scales in the Seto Inland Sea. Cont. Shelf Res. 1984, 3, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Han, S.; Zhang, D.; Shan, B.; Wei, D. Variations in Dissolved Oxygen and Aquatic Biological Responses in China’s Coastal Seas. Environ. Res. 2023, 223, 115418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X. Impacts of High-Density Suspended Aquaculture on Water Currents: Observation and Modeling. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Guo, J.; Li, J.; Mu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Li, H. Definition of Water Exchange Zone between the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea and the Effect of Winter Gale on It. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2017, 36, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhai, F.; Gu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. Drastic Fluctuation in Water Exchange Between the Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea Caused by Typhoon Lekima in August 2019: A Numerical Study. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2023, 128, e2022JC019260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, A.G.; Pipko, I.I. Influence of Wind and Yukon River Runoff on Water Exchange between the Bering and Chukchi Seas. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2023, 59, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Sun, J.; Tao, L.; Li, Y.; Nie, Z.; Liu, H.; Chen, R.; Yuan, D. Combined Effect of Tides and Wind on Water Exchange in a Semi-Enclosed Shallow Sea. Water 2019, 11, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, L.; Niu, Q.; Xia, M. The Roles of Wind and Baroclinic Processes in Cross-Isobath Water Exchange within the Bohai Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2022, 274, 107944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.C.; Geyer, W.R.; Lerczak, J.A. Numerical Modeling of an Estuary: A Comprehensive Skill Assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2005, 110, 2004JC002691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J. On the Validation of Models. Phys. Geogr. 1981, 2, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdyke, D. Hydrodynamics and Water Quality: Modeling Rivers, Lakes, and Estuaries. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2008, 89, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, Z.; Hu, J.; Cucco, A.; Zhu, J.; Sun, Z.; Huang, L. Numerical Simulation of the Hydrodynamics and Water Exchange in Sansha Bay. Ocean Eng. 2017, 139, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrawan, I.G.; Asai, K. Numerical Study on Tidal Currents and Seawater Exchange in the Benoa Bay, Bali, Indonesia. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2014, 33, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, G.; Xu, J.; Dong, P.; Qiao, L.; Liu, S.; Sun, P.; Fan, Z. Seasonal Evolution of the Yellow Sea Cold Water Mass and Its Interactions with Ambient Hydrodynamic System. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2016, 121, 6779–6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honfo, K.J.; Chaigneau, A.; Morel, Y.; Duhaut, T.; Marsaleix, P.; Okpeitcha, O.V.; Stieglitz, T.; Ouillon, S.; Baloitcha, E.; Rétif, F. Water Mass Circulation and Residence Time Using Eulerian Approach in a Large Coastal Lagoon (Nokoué Lagoon, Benin, West Africa). Ocean Model. 2024, 190, 102388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Shen, J.; Qin, Q.; Du, J. Water exchange and its relationships with external forcings and residence time in Chesapeake Bay. J. Mar. Syst. 2021, 215, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, X.; Qiao, F.; Xia, C.; Wang, G.; Yuan, Y. Upwelling and Surface Cold Patches in the Yellow Sea in Summer: Effects of Tidal Mixing on the Vertical Circulation. Cont. Shelf Res. 2010, 30, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Jia, F.; Shi, R.; Zhang, S.; Lian, Q.; Zong, X.; Chen, Z. Influence of Stratification and Wind Forcing on the Dynamics of Lagrangian Residual Velocity in a Periodically Stratified Estuary. Ocean Sci. 2024, 20, 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, L.M.; Xue, H.; Morello, S.L.; Yund, P.O. Nearshore Flow Patterns in a Complex, Tidally Driven System in Summer: Part I. Model Validation and Circulation. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2018, 123, 2401–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Spall, M.A. Topographic Influences on the Wind-Driven Exchange between Marginal Seas and the Open Ocean. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2021, 51, 3663–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dunne, J.P.; Stock, C.A.; Harrison, M.J.; Adcroft, A.; Resplandy, L. Simulating Water Residence Time in the Coastal Ocean: A Global Perspective. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 13910–13919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Euse, A.; Morales-Márquez, V.; Molcard, A. On the Observed Wind-Driven Circulation Response in Small Semienclosed Bays. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2023, 53, 2245–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.R.; Song, J.; Xia, Y.Y.; Bao, X.W.; Liu, Y.L.; Chen, X.P.; Yao, Z.G.; Yuan, Z.Y. Numerical Simulation of Exchange of POC and DOC in the Sea Waters Adjacent to Changhai County, Liaoning Province, China. Part I: Model Development and Verification. Period. Ocean Univ. China 2015, 45, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Duan, H.-F.; Keramat, A. Water Exchange Capability Induced by Seasonal and Regional Variability: Assessment of Hong Kong Waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 206, 116732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Liu, D.; Fu, Q.; Guo, X.; Liu, G.; Liu, H.; Wang, S. Seasonal Variability of Water Residence Time in the Subei Coastal Water, Yellow Sea: The Joint Role of Tide and Wind. Ocean Model. 2022, 180, 102137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Peng, L.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Shi, H.; Zhan, C.; You, Z. The Effects of Changes in the Coastline and Water Depth on Tidal Prism and Water Exchange of the Laizhou Bay, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1459482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupiola, J.; Bárcena, J.F.; García-Alba, J.; García, A. Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Mixing and Stratification in Suances Estuary Using the Potential Energy Anomaly Budget Equation. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1531684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Xia, M. Seasonal Dynamics of Water Circulation and Exchange Flows in a Shallow Lagoon-Inlet-Coastal Ocean System. Ocean Model. 2023, 186, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, S.; Kwon, S.; Kang, D.; Kim, E. Variability in Water Temperature Vertical Distribution and Advective Influences: Observations from Early Summer 2021 in the Central Yellow Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchard, H. Combined Effects of Wind, Tide, and Horizontal Density Gradients on Stratification in Estuaries and Coastal Seas. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2009, 39, 2117–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yu, F.; Si, G.; Sun, F.; Liu, X.; Diao, X.; Chen, Z.; Nan, F.; Ren, Q. The Seasonal Evolution of the Yellow Sea Cold Water Mass Circulation: Roles of Fronts, Thermoclines, and Tidal Rectification. Ocean Model. 2024, 190, 102375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Su, M.; Yao, P.; Chen, Y.; Stive, M.J.F.; Wang, Z.B. Dynamics of a Tidal Current System in a Marginal Sea: A Case Study of the Yellow Sea, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 596388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Li, M.; Zu, T.; Cai, Z. Seasonality of Water Exchange in the Northern South China Sea from Hydrodynamic Perspective. Water 2023, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Park, K.; Wright, K.; Hu, X.; Kiaghadi, A.; Schoenbaechler, C.; Hua, J. Quantifying the Flushing Time of Major Coastal Bays in the Northern Gulf of Mexico from 20-Year Simulations. Estuaries Coasts 2026, 49, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Lin, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, Z.; Cai, Z.; Guo, X.; Gao, H. Seasonal Variations in the Water Residence Time in the Bohai Sea Using 3D Hydrodynamic Model Study and the Adjoint Method. Ocean Dyn. 2021, 71, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Starting Time | Dye Release Time | End Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | 1 May 2023 | 1 June 2023 | 1 October 2023 |

| Winter | 1 November 2023 | 1 December 2023 | 1 April 2024 |

| SKILL Value | Model Evaluation |

|---|---|

| >0.65 | Excellent |

| 0.50–0.65 | Very Good |

| 0.20–0.50 | Good |

| <0.20 | Poor |

| Stations | Sur.Vel | Sur.Dir | Bot.Vel | Bot.Dir |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.6566 | 0.8965 | 0.6102 | 0.9110 |

| S2 | 0.7415 | 0.8997 | 0.7549 | 0.9181 |

| Season | Deep-Level | Dcsd | Xcsd | Zzd | Gld | Hyd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | Surface | 0.0335 | 0.0275 | 0.0255 | 0.0354 | 0.0373 |

| Bottom | 0.0243 | 0.0197 | 0.0163 | 0.0165 | 0.0222 | |

| Winter | Surface | 0.0439 | 0.0417 | 0.0376 | 0.0492 | 0.0690 |

| Bottom | 0.0368 | 0.0219 | 0.0131 | 0.0199 | 0.0248 |

| Case | Season | Tides | Wind | Temperature & Salinity | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case1 | Summer | Yes | Yes | Yes | Summer control run including tides, wind, and thermohaline forcing |

| Case2 | Winter | Yes | Yes | Yes | Winter control run including tides, wind, and thermohaline forcing |

| Case3 | Summer | Yes | Yes | No | Sensitivity experiment excluding thermohaline effects in summer |

| Case4 | Winter | Yes | Yes | No | Sensitivity experiment excluding thermohaline effects in winter |

| Case5 | Summer | Yes | No | Yes | Sensitivity experiment excluding wind forcing in summer |

| Case6 | Summer | Yes | No | Yes | Sensitivity experiment excluding wind forcing in winter |

| Summer Cases | Chx | Dcsd | Xcsd | Zzd | Gld | Hyd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case1 | 41.27 | 61.00 | 59.50 | 26.21 | 56.08 | 13.04 |

| Case3 | 25.21 | 41.92 | 39.86 | 15.88 | 39.79 | 30.92 |

| Case5 | 18.17 | 21.96 | 19.25 | 19.50 | 28.25 | 7.29 |

| Winter Cases | ||||||

| Case2 | 35.71 | 45.21 | 42.67 | 8.54 | 7.63 | 9.38 |

| Case4 | 20.96 | 35.17 | 34.83 | 42.42 | 9.42 | 12.21 |

| Case6 | 11.46 | 24.38 | 23.00 | 5.42 | 10.5 | 12.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, M.; Song, J.; Bi, C.; Jiang, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Tian, J.; Sun, Q. Study on Hydrodynamics and Water Exchange Capacity in the Changhai Sea Area Based on the FVCOM Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020162

Yang M, Song J, Bi C, Jiang D, Li M, Zhang Y, Guo J, Tian J, Sun Q. Study on Hydrodynamics and Water Exchange Capacity in the Changhai Sea Area Based on the FVCOM Model. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(2):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020162

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Minghao, Jun Song, Congcong Bi, Dawei Jiang, Ming Li, Yuan Zhang, Junru Guo, Jie Tian, and Qian Sun. 2026. "Study on Hydrodynamics and Water Exchange Capacity in the Changhai Sea Area Based on the FVCOM Model" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 2: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020162

APA StyleYang, M., Song, J., Bi, C., Jiang, D., Li, M., Zhang, Y., Guo, J., Tian, J., & Sun, Q. (2026). Study on Hydrodynamics and Water Exchange Capacity in the Changhai Sea Area Based on the FVCOM Model. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(2), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14020162