Experimental Comparisons of the Wave Attenuation Characteristics Among Different Flexible-Membrane Breakwaters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup

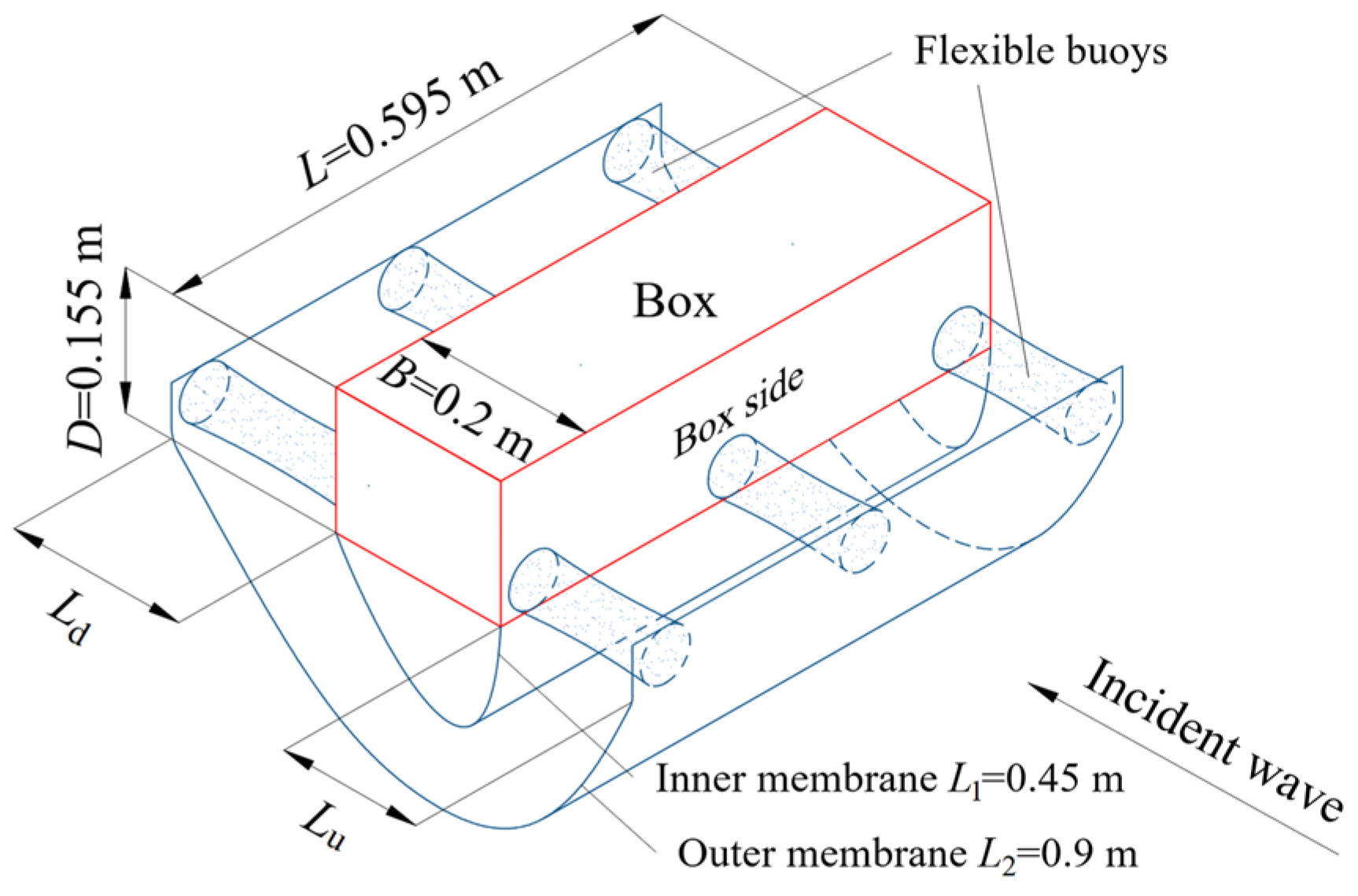

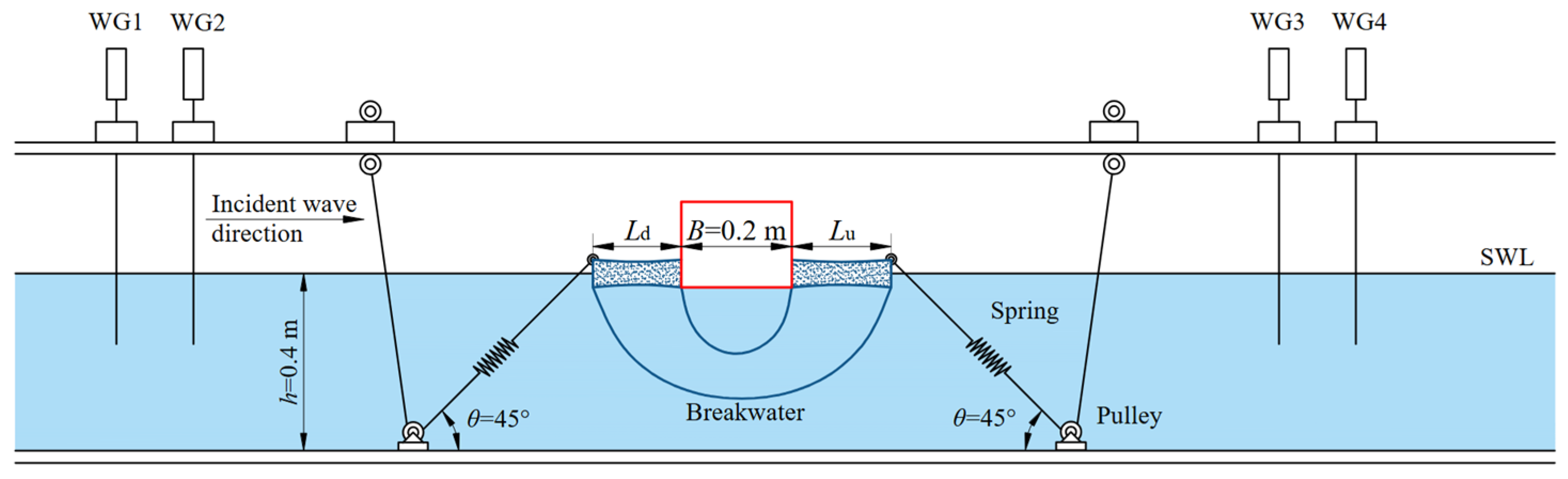

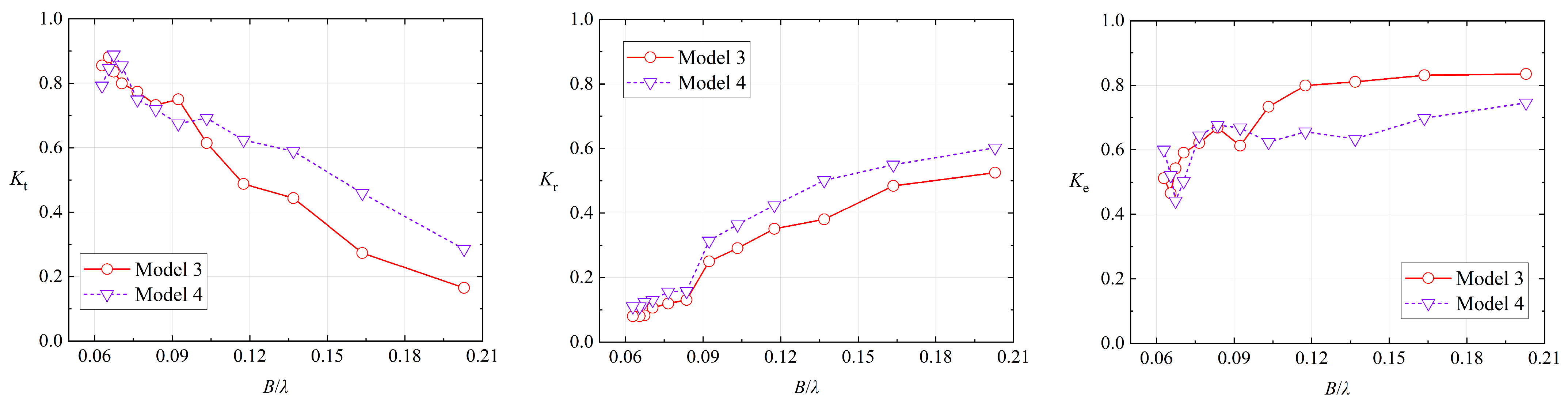

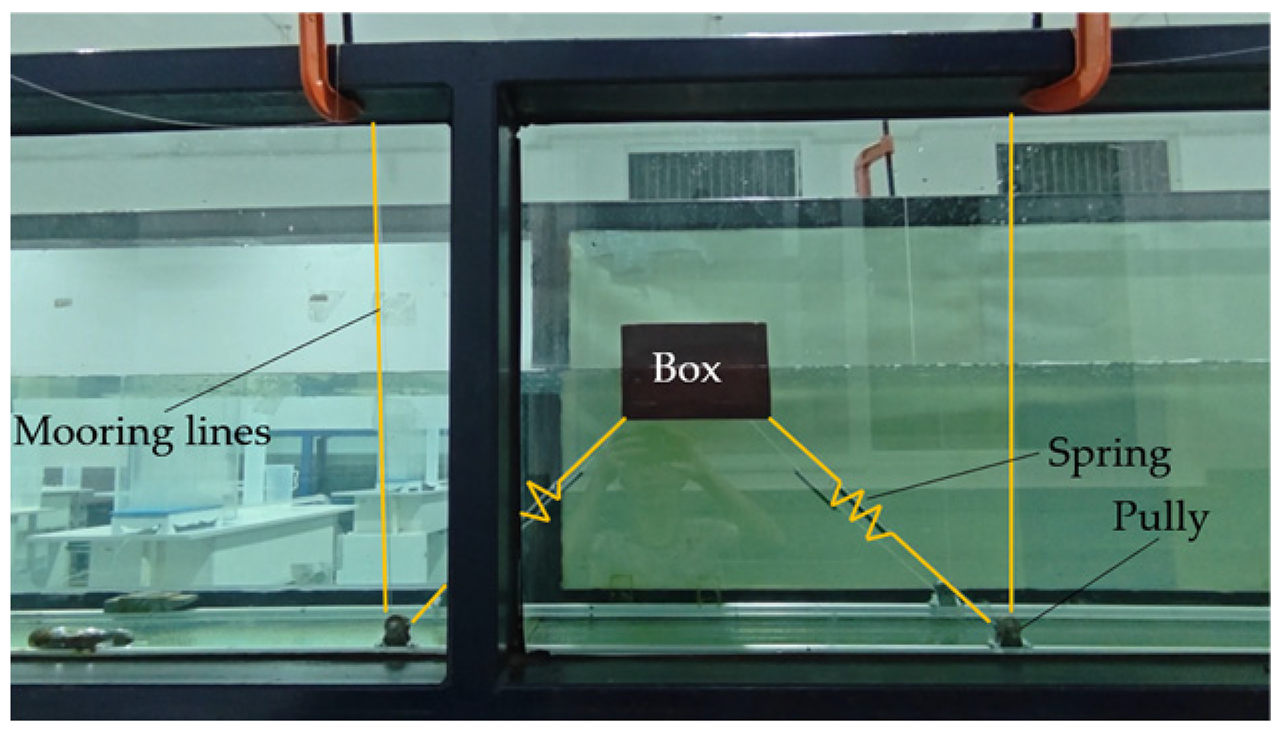

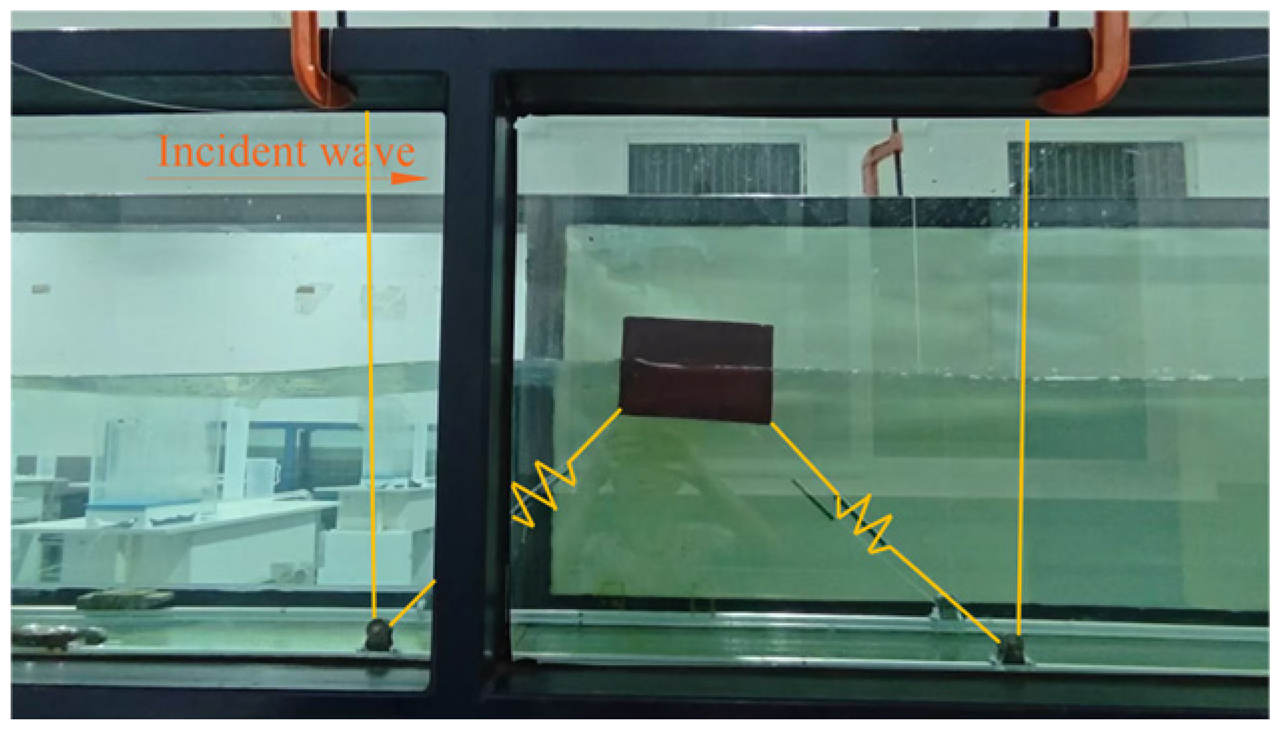

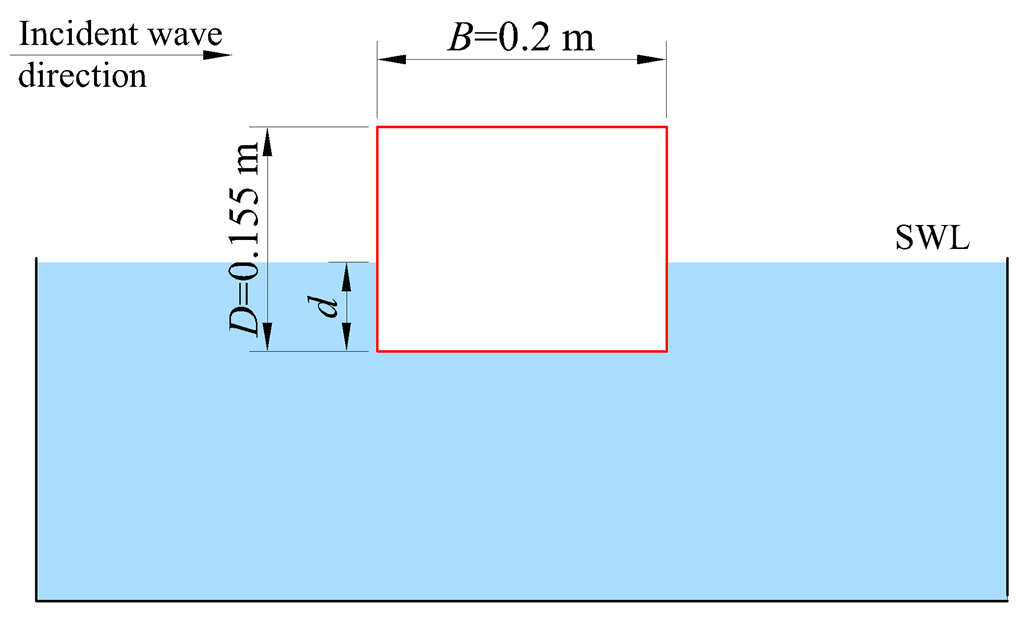

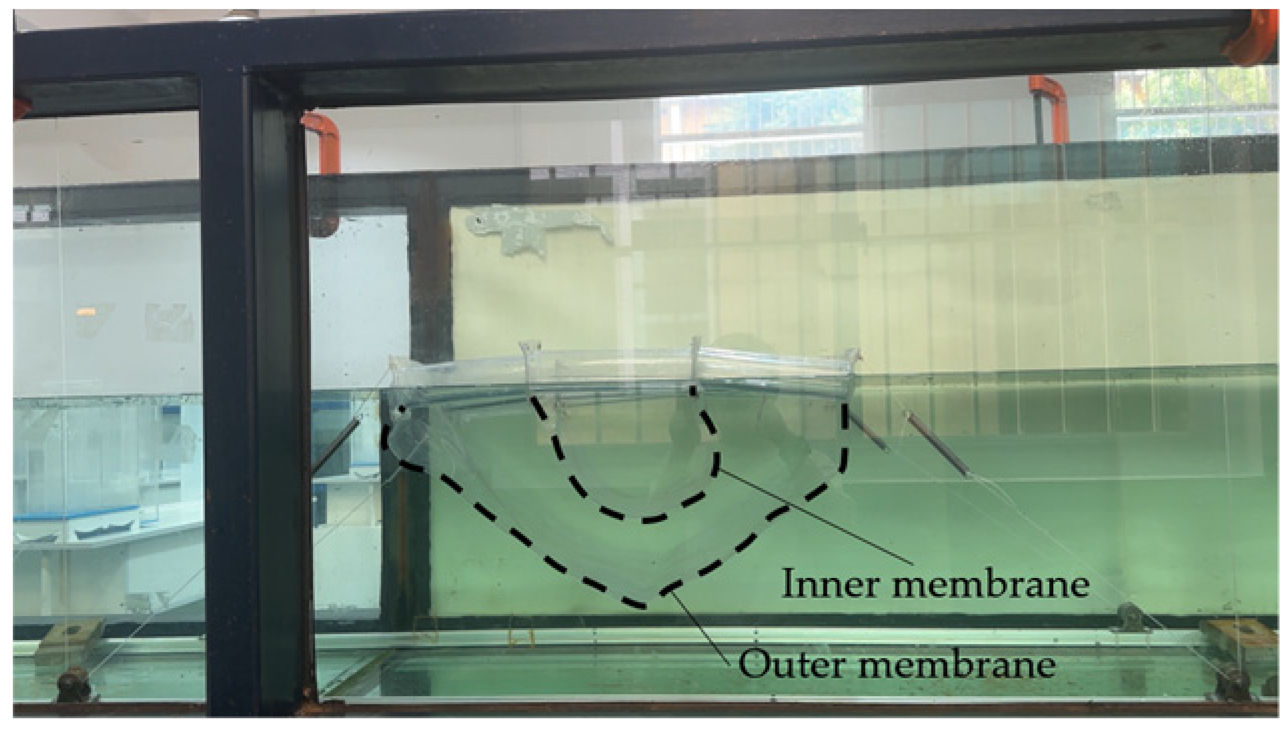

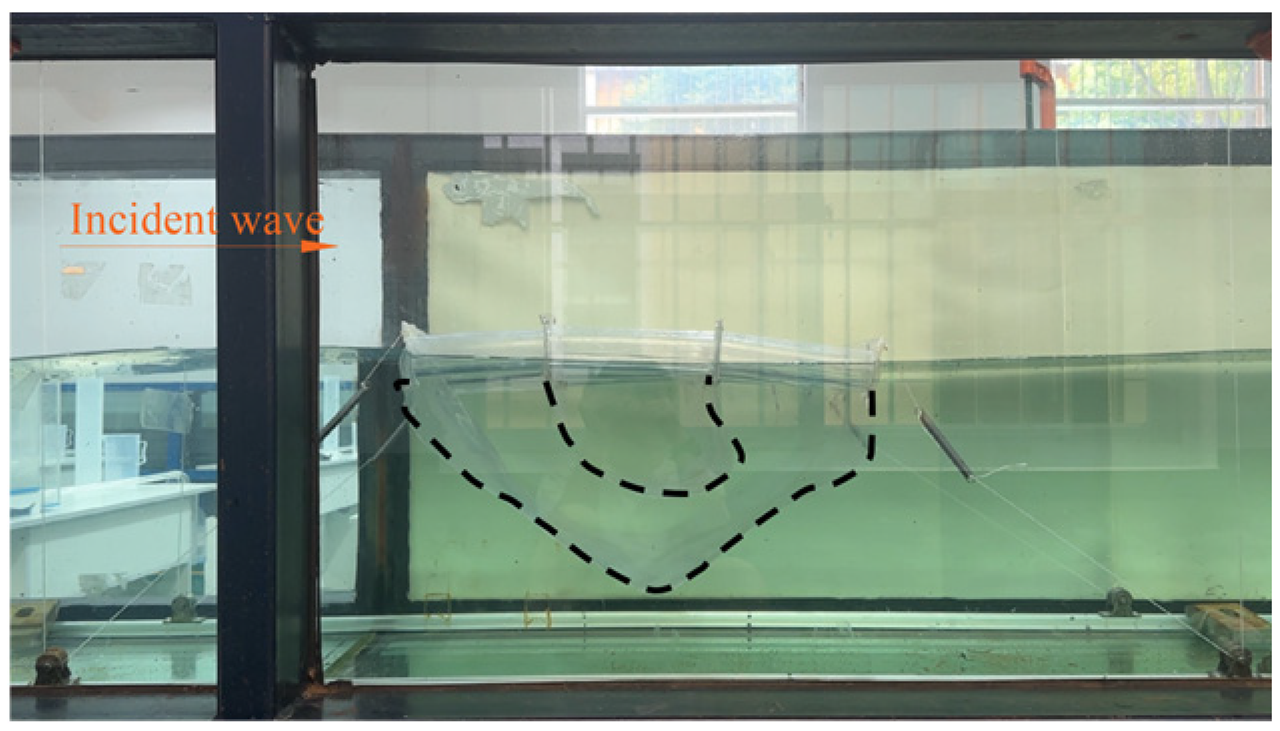

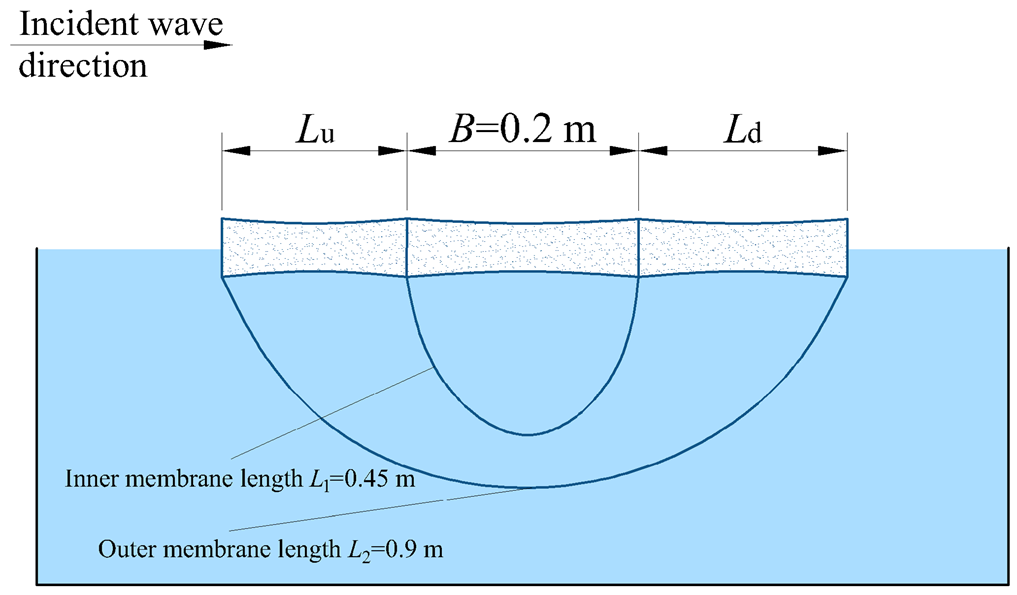

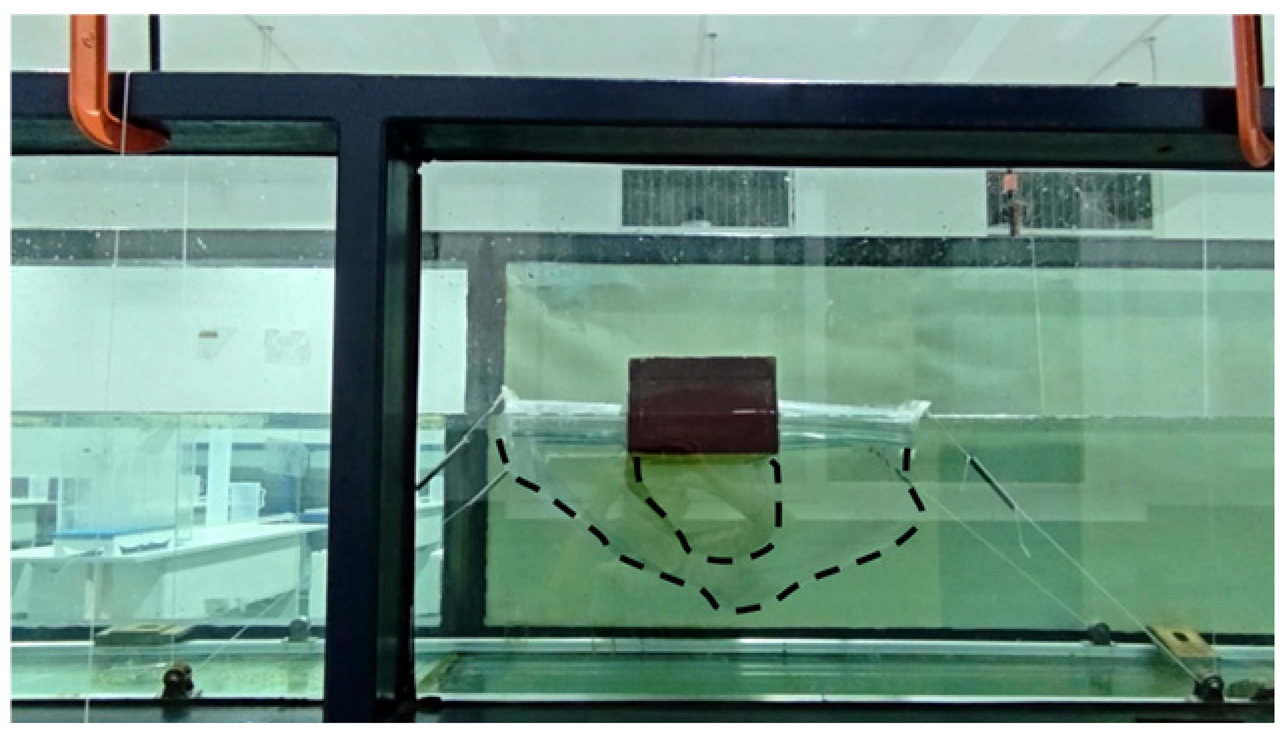

2.1. The Proposed Breakwater

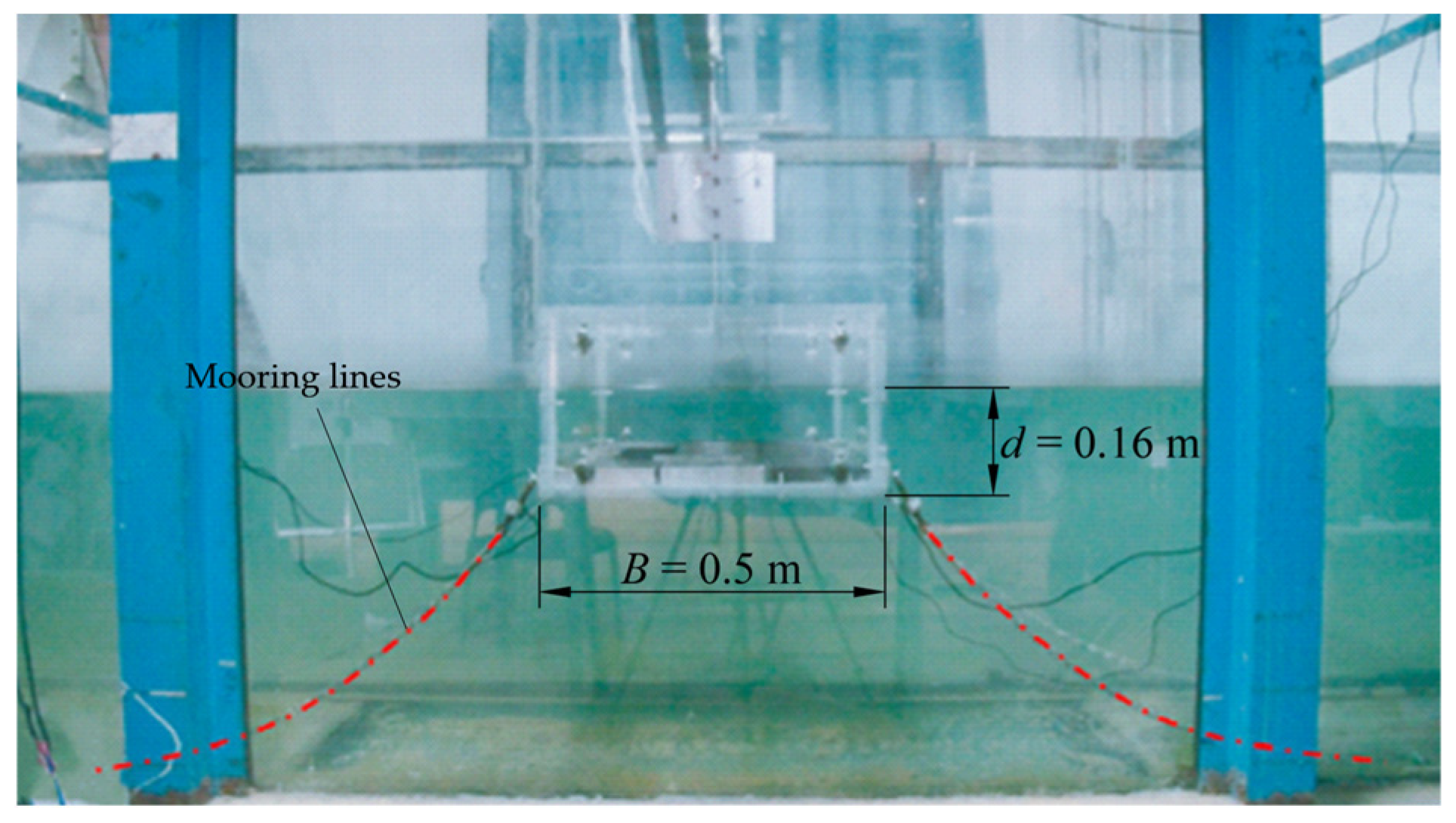

2.2. The Tested Breakwaters

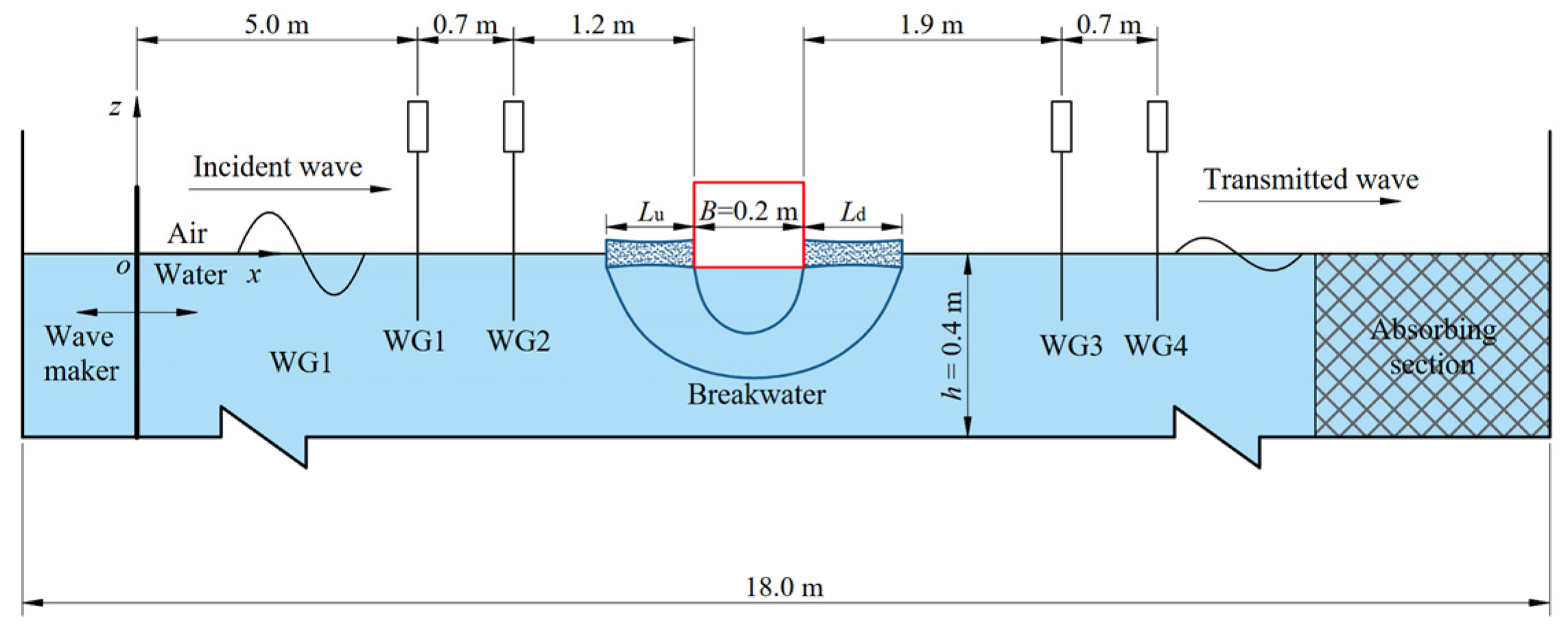

2.3. Experimental Facilities

2.4. Wave Conditions

3. The Hydrodynamic Coefficients

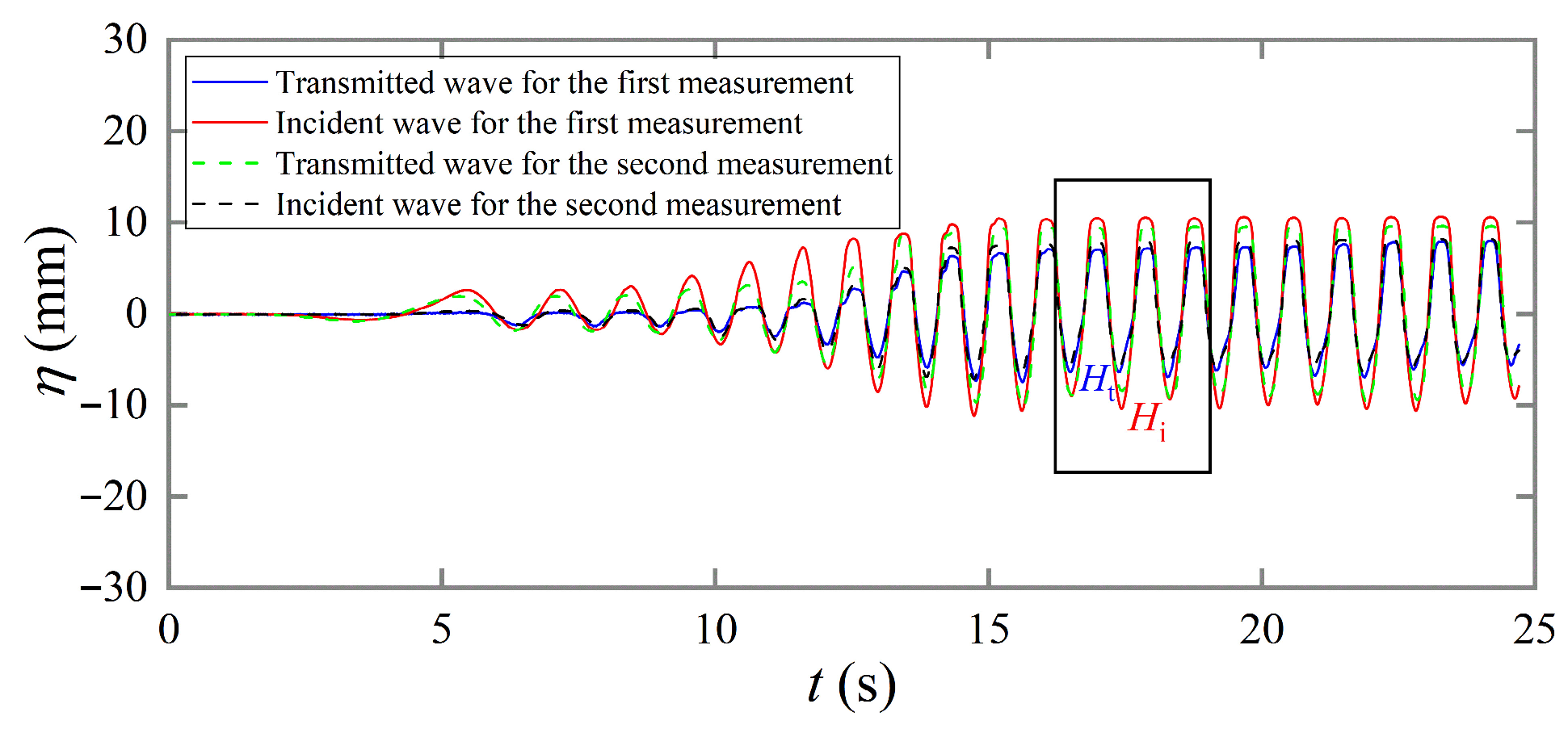

3.1. Transmission Coefficient

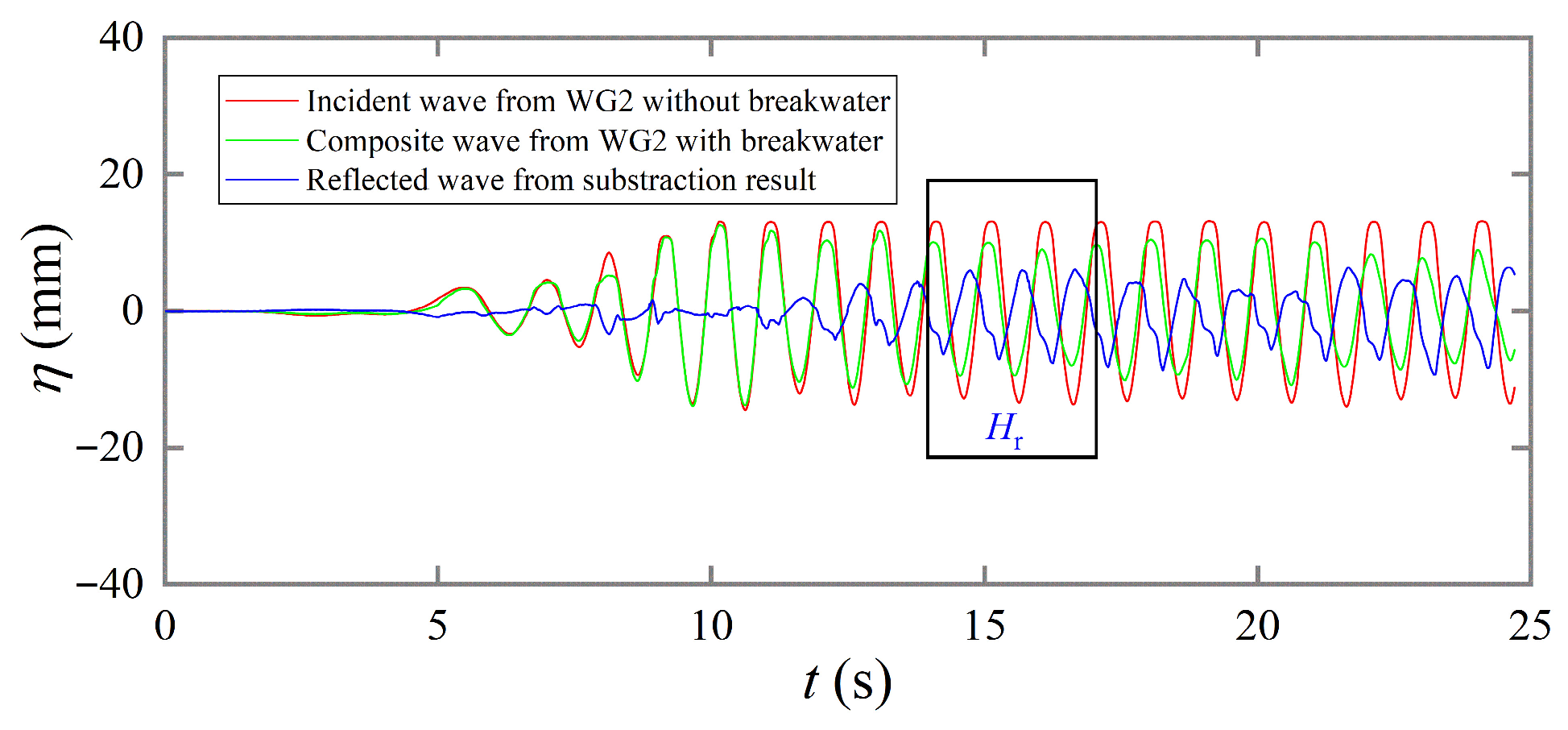

3.2. Reflection Coefficient

3.3. Energy Dissipation Coefficient

4. Discussion

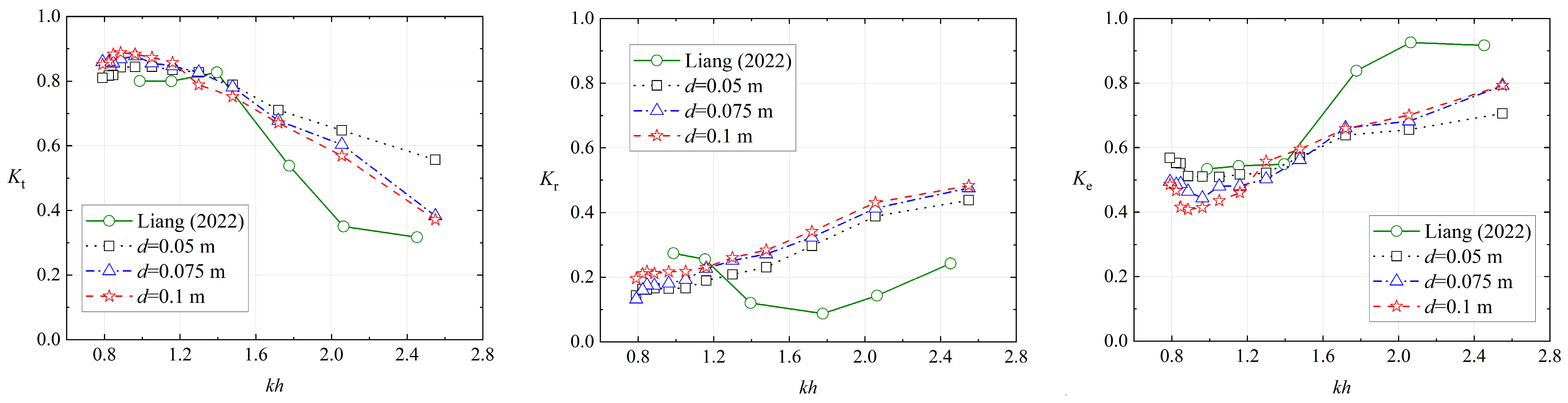

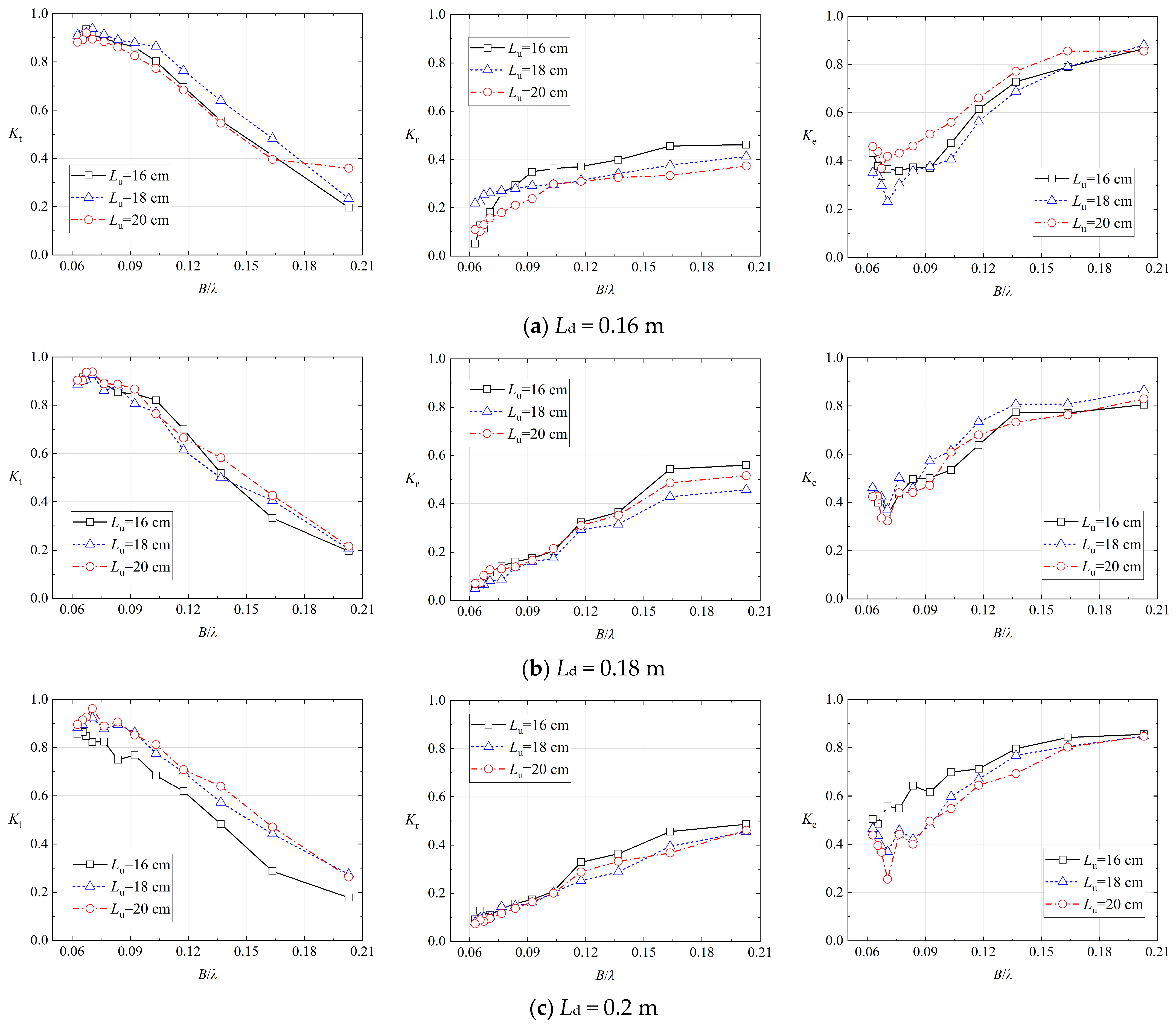

4.1. The Influence of Draft d on the Breakwater of Model 1

4.2. The Influence of Upstream-Side Spacing Lu on the Breakwater of Model 2

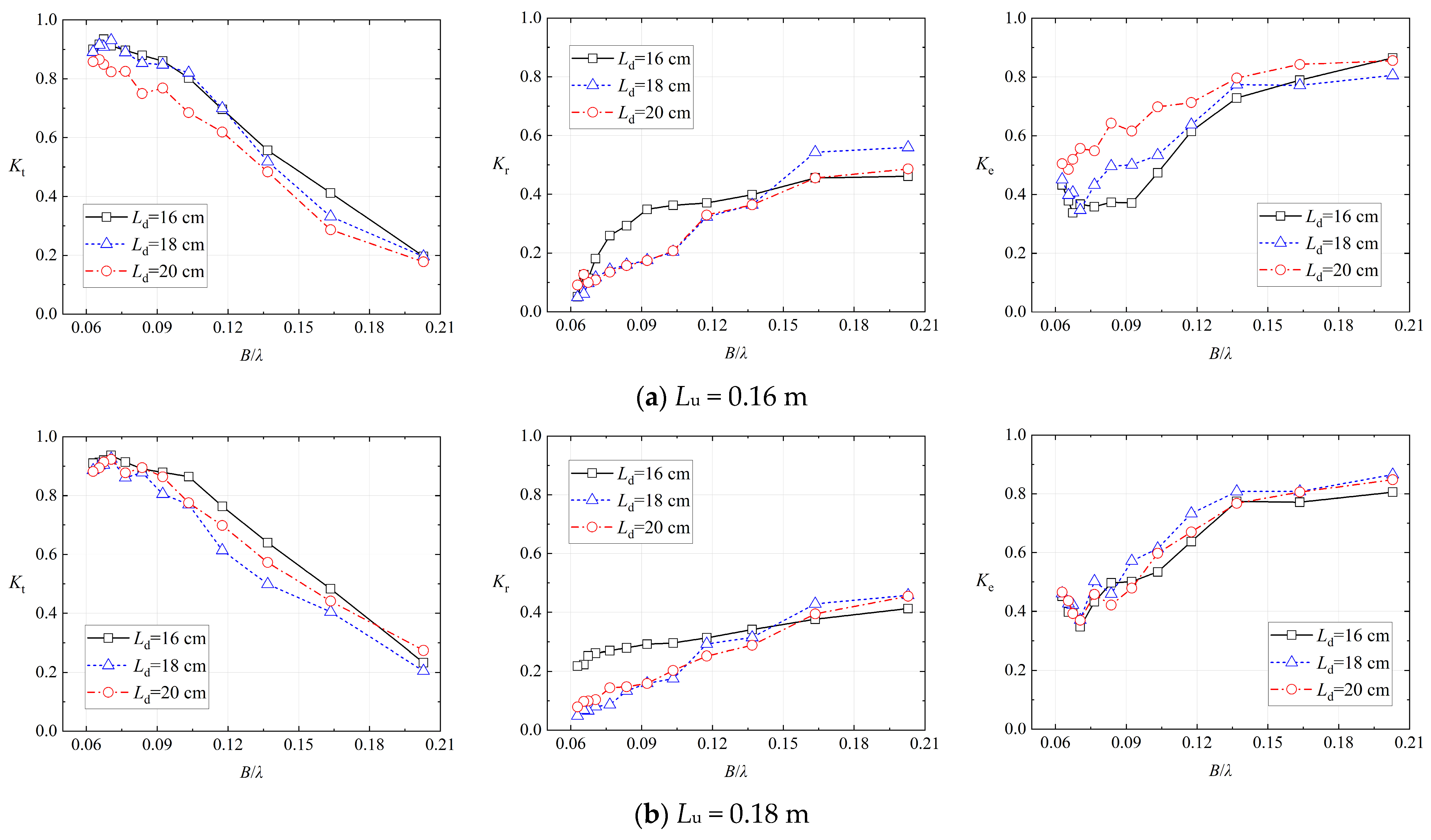

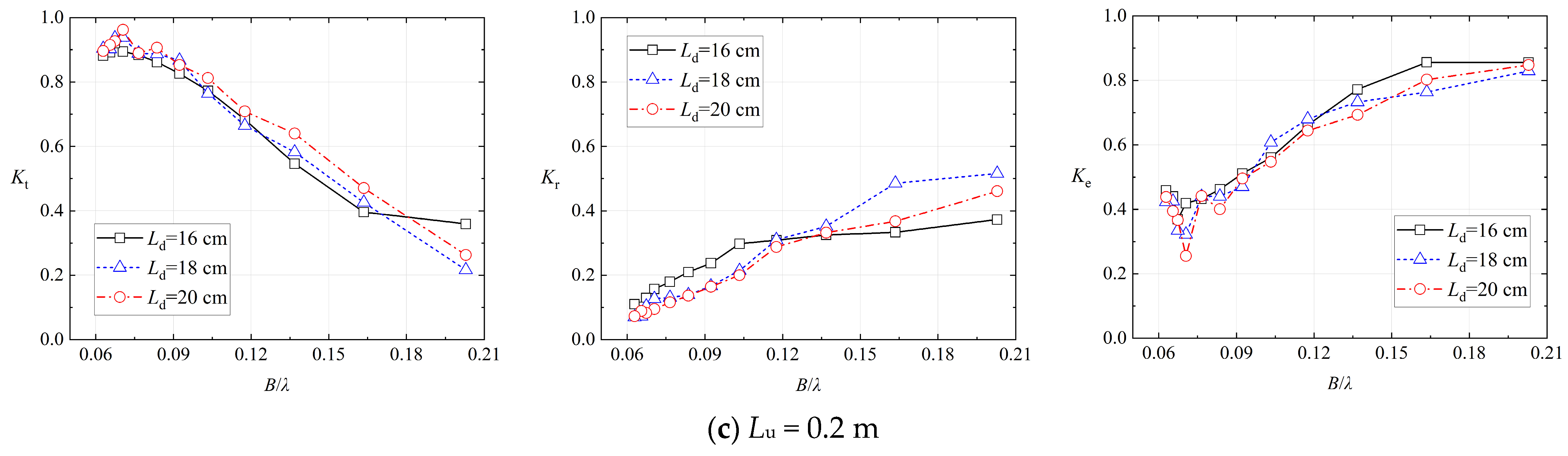

4.3. The Influence of Downstream-Side Spacing Ld on the Breakwater of Model 2

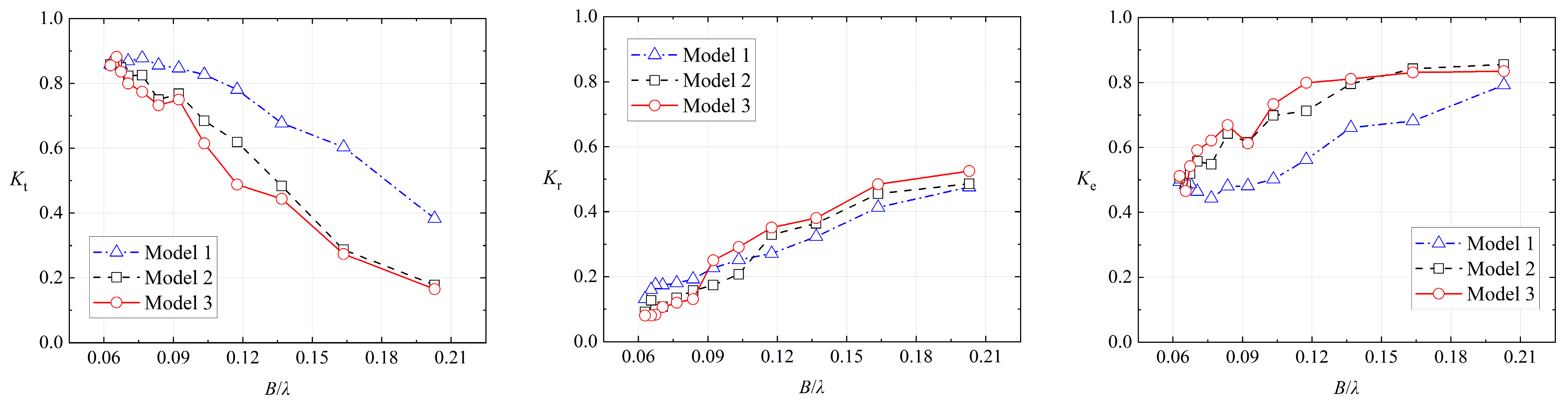

4.4. The Comparisons of Model 3 to Model 1 and Model 2

4.5. The Comparisons of Model 3 and Model 4 for the Influence of the Spacings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dai, J.; Wang, C.M.; Utsunomiya, T.; Duan, W. Review of recent research and developments on floating breakwaters. Ocean Eng. 2018, 158, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.Y. Study on Hydrodynamic Characteristics of Pontoon-Plate Type Floating Breakwaters. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar, D.; Bhattacharjee, J.; Guedes Soares, C. Scattering of gravity waves by multiple surface-piercing floating membrane. Appl. Ocean Res. 2013, 39, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. Experimental Investigation on Influence Factor of Twin-Pontoon-Plate Floating Breakwater. Master’s Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantoulaki, I.; Angelides, D.C. Analysis of performance of hinged floating breakwaters. Eng. Struct. 2010, 32, 2407–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.Y.; Bian, X.Q.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, K. Experimental study of hydrodynamic performance for double-row rectangular floating breakwaters with porous plates. Ships Offshore Struct. 2019, 14, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Z.; Wu, J.P. Study on Wave attenuation characteristics of two box structures. In Proceedings of the 30th International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, Shanghai, China, 11–16 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Meringolo, D.D.; Hu, J. Study on the hydrodynamics of a twin floating breakwater by using SPH method. Coast. Eng. 2023, 179, 104230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Huang, Z.; Wing-Keung Law, A. Hydrodynamic performance of a rectangular floating breakwater with and without pneumatic chambers: An experimental study. Ocean Eng. 2012, 51, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.J.; Kolahdoozan, M.; Tahershamsi, A.; Abdolali, A. Experimental study of the performance of floating breakwaters with heave motion. Civ. Eng. Infrastruct. J.-CEIJ 2014, 47, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Deng, X.; Cheng, Y. An Experimental study of double-row floating breakwaters. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2019, 24, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Li, J.; Pan, J.; Yuan, Z. An experimental study of a rectangular floating breakwater with vertical plates as wave-dissipating components. Appl. Ocean Res. 2023, 133, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.Z.; Xu, T.J.; Wang, S. Hydrodynamic investigation of a new type of floating breakwaters integrated with porous baffles. Appl. Ocean Res. 2025, 154, 104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, S.T.; Kim, M.H. Flexible membrane wave barrier. II: Floating/submerged buoy-membrane system. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 1997, 123, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Edge, B.L.; Kee, S.T.; Zhang, L. Performance evaluation of buoy-membrane wave barriers. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Coastal Engineering, Orlando, FL, USA, 2–6 September 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, I.H.; Kee, S.T.; Kim, M.H. Performance of dual flexible membrane wave barriers in oblique waves. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 1998, 124, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, M.; Ye, W.; Demirbilek, Z.; Zhang, J. Field and numerical comparisons of the RIBS floating breakwater. J. Hydraul. Res. 2002, 40, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanson, M.W. Physical Modeling of a Floating Breakwater with a Membrane. Master’s Thesis, University of Florida, Monterey, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kee, S.T. Floating pontoon-membrane breakwater. J. Ocean Sci. Technol. 2004, 1, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.P.; Mei, T.L.; Zou, Z.J. Experimental study on wave attenuation performance of a new type of free surface breakwater. Ocean Eng. 2022, 244, 110447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.P.; Li, C.R.; Qi, J.J.; Xu, X.Y.; Li, J.N.; Zhang, X.X.; Qin, Q.; Zhou, Z.R. Experimental study on the hydrodynamic performance of a side-by-side box-membrane breakwater. Ocean Eng. 2024, 302, 117658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.P.; Yi, X.; Zou, Z.J.; Zhan, P.; Chen, C.C. Experimental study on the hydrodynamic performance of a U-shaped flexible membrane breakwater. In Proceedings of the 42nd International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Melbourne, Australia, 11 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman, J.M. Dynamics of offshore floating wind turbines-model development and verification. Wind Energy 2009, 12, 459–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Yan, C.; Shi, W.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, X.; Han, X.; Michailides, C. Experimental Study on the Hydrodynamic Analysis of a Floating Offshore Wind Turbine Under Focused Wave Conditions. Energies 2025, 18, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wu, J.P.; Jiang, M.S.; Zheng, X.W.; Zhao, X.S. Performance test and analysis on small piston-type wave flume. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. (Transp. Sci. Eng.) 2017, 41, 995–998. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.P.; Luo, H.Y.; Zou, Z.J.; Chen, C.Z.; Yi, X.; Zhan, P. Estimation of reflected and incident waves for breakwater tests in a 2D wave flume in regular waves. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.W.; Yue, W.Z.; Sheng, S.W.; Wu, J.P.; Zou, Z.J. Numerical and experimental study on the Bragg reflection of water waves by multiple vertical thin plates. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, A. Experimental study on hydrodynamic characteristics of the box-type floating breakwater with different mooring configurations. Ocean Eng. 2022, 254, 111296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruol, P.; Martinelli, L.; Pezzutto, P. Formula to predict transmission for π-type floating breakwaters. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2013, 139, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

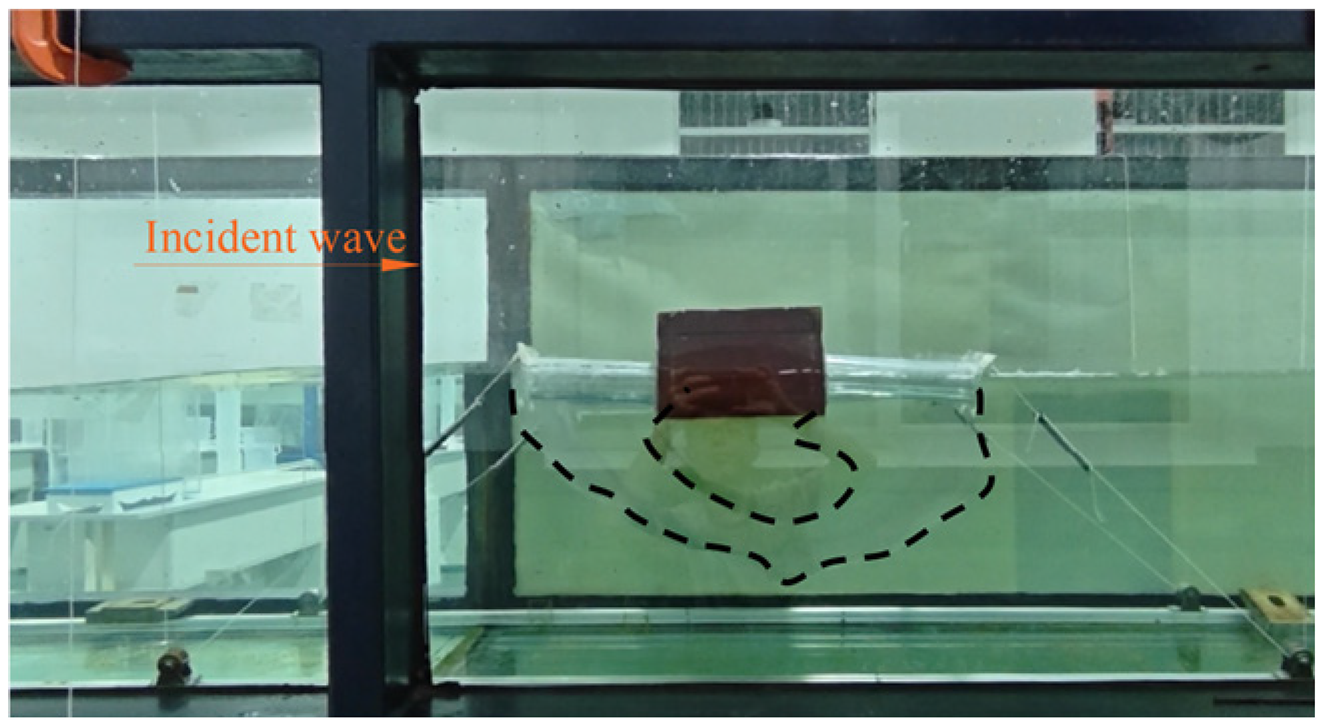

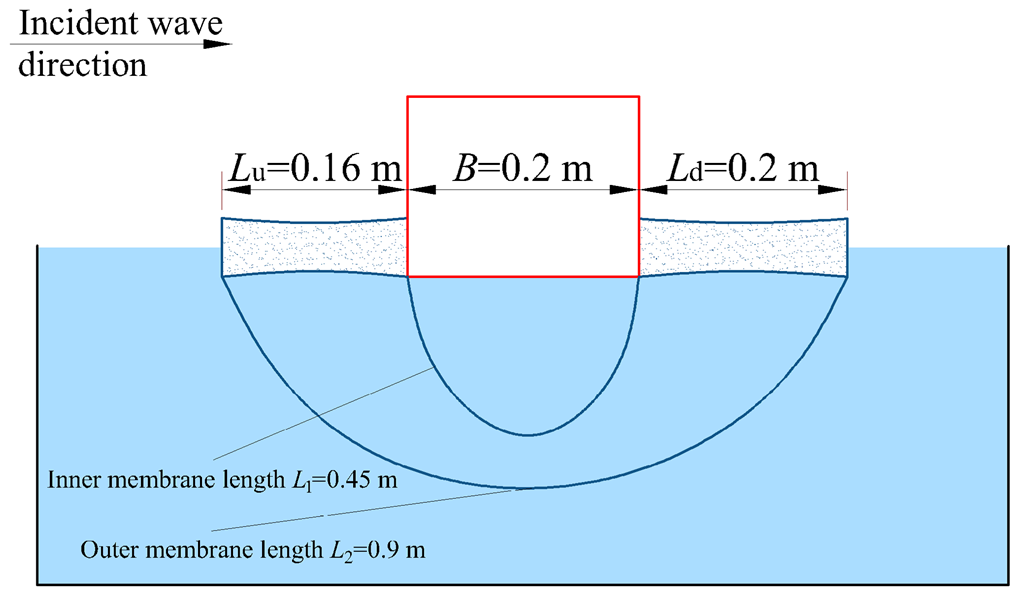

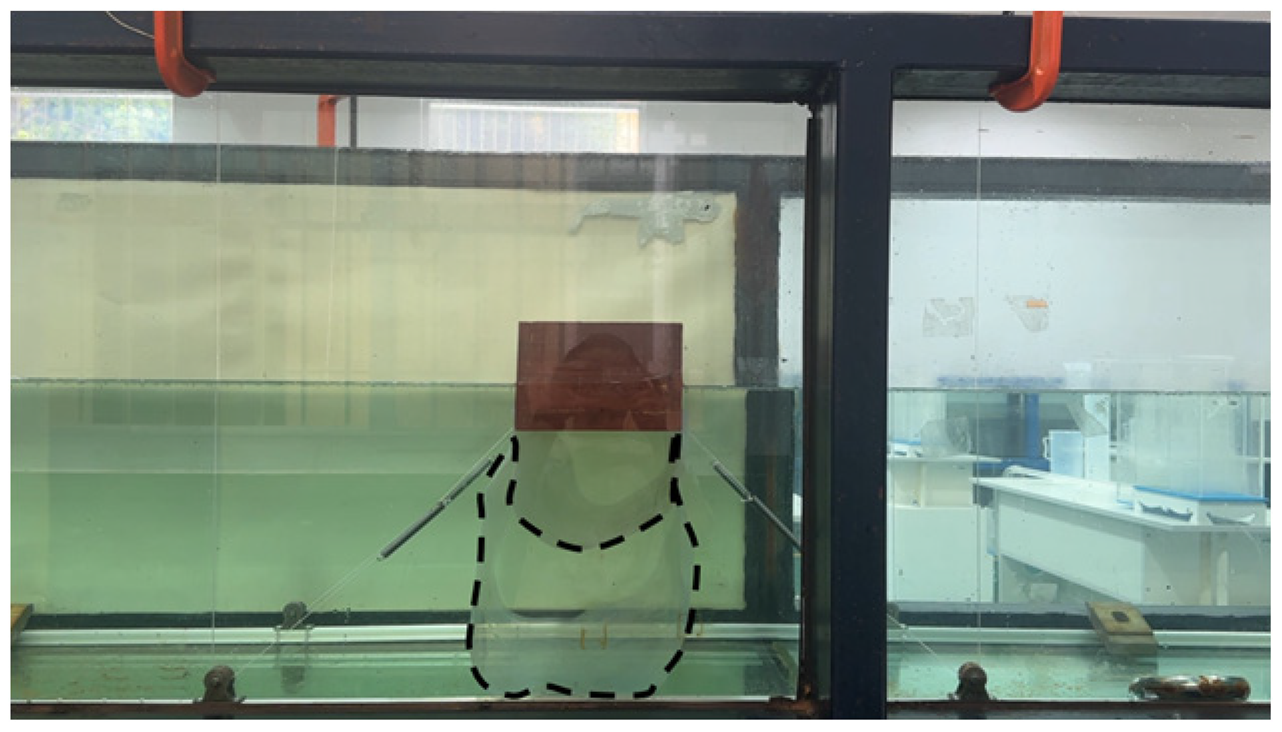

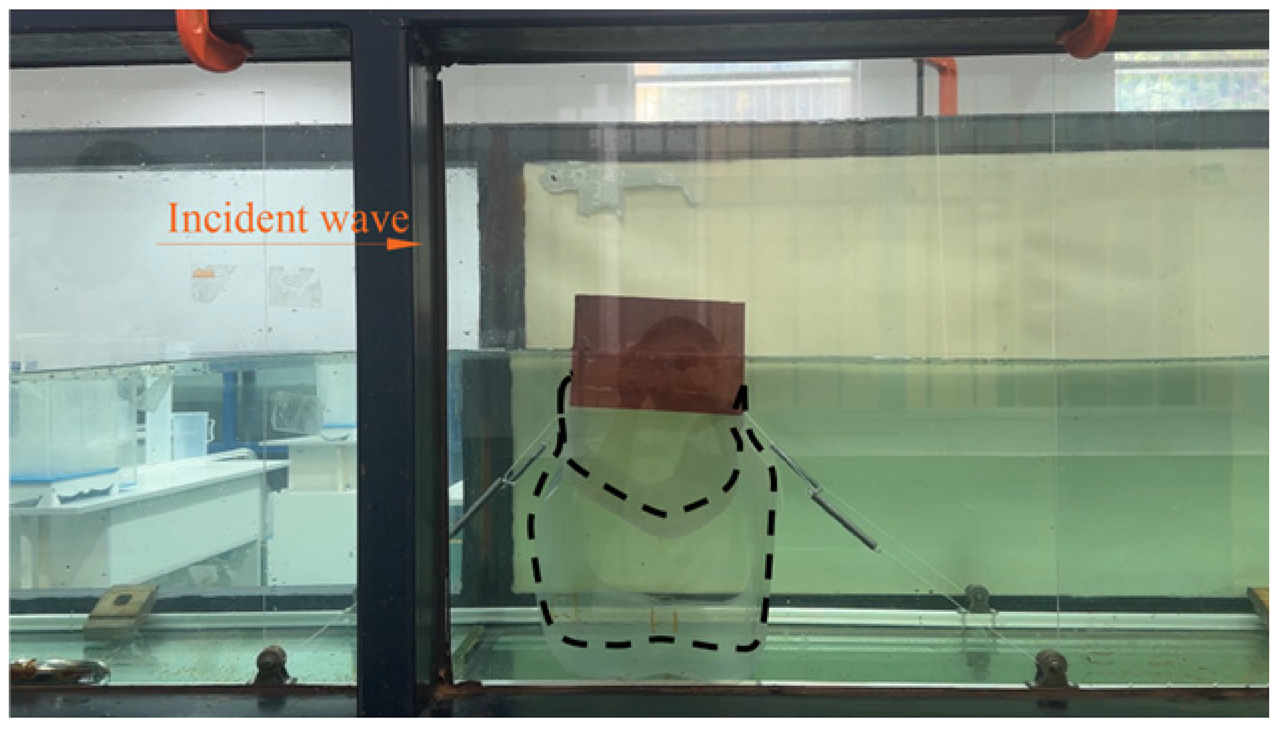

| Photographs in Calm Water | Photographs in Waves | Sketches |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

| Model 1 | ||

|  |  |

| Model 2 | ||

|  |  |

| Model 3 | ||

|  |  |

| Model 4 | ||

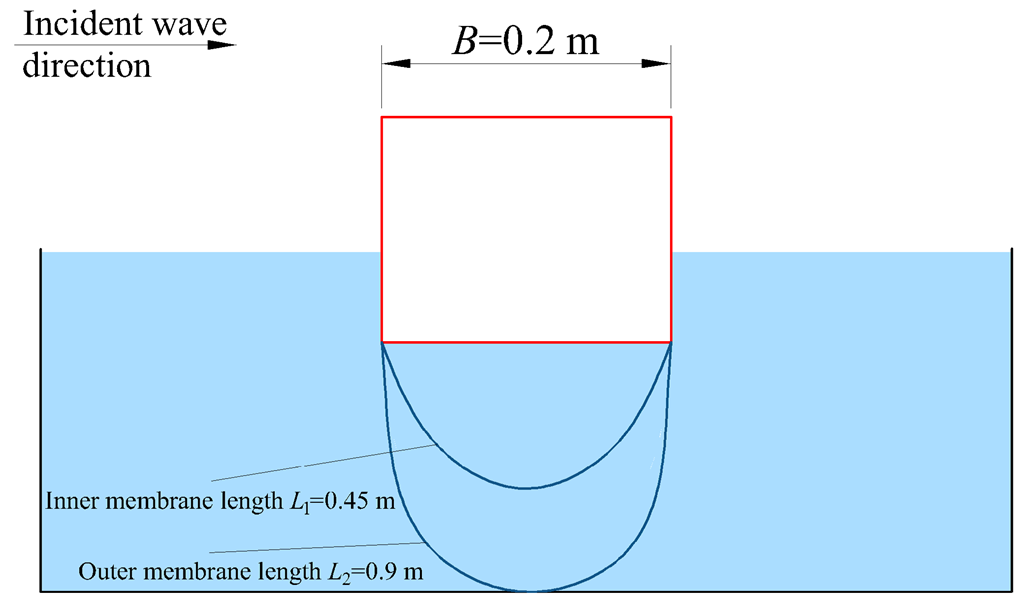

| Model | Rectangular Box Size (m) | Membrane Length (m) | Lu (m) | Ld (m) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | B | D | d | Inner | Outer | |||

| Model 1 | 0.595 | 0.2 | 0.155 | 0.05, 0.075, 0.01 | - | - | - | - |

| Model 2 | 0.595 | 0.2 | - | - | 0.45 | 0.9 | 0.16, 0.18, 0.2 | 0.16, 0.18, 0.2 |

| Model 3 | 0.595 | 0.2 | 0.155 | 0.075 | 0.45 | 0.9 | 0.16 | 0.2 |

| Model 4 | 0.595 | 0.2 | 0.155 | 0.075 | 0.45 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 |

| T (s) | λ (m) | H/λ | H (mm) | h (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8–1.76 | 0.986–3.182 | 0.02 | 19.74–63.66 | 0.4 |

| Breakwater | Box Size (m) | Mooring System | h (m) | T (m) | H (m) | H/λ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | d | Stiffness (kN/m) | Pretension Force (N) | |||||

| Liang (2022) [28] | 0.5 | 0.16 | 2.36 | 0 | 0.6 | 1.0–1.8 | 0.1 | 0.026–0.065 |

| Model 1 | 0.2 | 0.05 0.075 0.1 | 3.13 | 250 | 0.4 | 0.80–1.76 | 0.020–0.064 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cai, M.-L.; Wu, J.-P.; Wang, S.-M.; Yi, X. Experimental Comparisons of the Wave Attenuation Characteristics Among Different Flexible-Membrane Breakwaters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010078

Cai M-L, Wu J-P, Wang S-M, Yi X. Experimental Comparisons of the Wave Attenuation Characteristics Among Different Flexible-Membrane Breakwaters. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010078

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Ming-Liang, Jing-Ping Wu, Shao-Min Wang, and Xi Yi. 2026. "Experimental Comparisons of the Wave Attenuation Characteristics Among Different Flexible-Membrane Breakwaters" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010078

APA StyleCai, M.-L., Wu, J.-P., Wang, S.-M., & Yi, X. (2026). Experimental Comparisons of the Wave Attenuation Characteristics Among Different Flexible-Membrane Breakwaters. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010078