1. Introduction

USVs play a vital role in ocean monitoring, hydrographic surveys, and maritime security. Path tracking control, as the core technology of USV autonomous navigation, directly impacts the precision and reliability of task execution [

1]. In existing research, the combination of PID controllers and line-of-sight (LOS) guidance has been widely adopted due to its simple structure and ease of implementation. The core of path tracking control comprises two components: guidance and control, with the guidance aspect having been the focus of extensive research by numerous scholars on the optimization of LOS guidance algorithms in recent years. In 2020, Wang et al. [

2] proposed an improved integral line-of-sight (ILOS) guidance algorithm, adjusting look-ahead distance based on speed and tracking error. In 2024, Zhou et al. [

3] addressed the issue of low path tracking accuracy in complex waters by proposing an adaptive LOS (ALOS) guidance controller. In 2024, Qi et al. [

4] reduced overshoot in curved paths using a vector field-based adaptive LOS (VFALOS) guidance algorithm. In 2025, Sun et al. [

5] addressed wind disturbances with a time-varying sideslip compensation adaptive LOS (TSC-ALOS) guidance algorithm. In 2025, Li et al. [

6] addressed the path tracking problem of USVs under the influence of ocean currents by proposing an adaptive LOS (ALOS) guidance law with bias angle compensation. Although the aforementioned research on the improvement and optimization of LOS algorithms has achieved certain results, it predominantly focuses on the optimization of single objectives, without addressing the coordinated optimization of multiple objectives.

In the realm of control algorithms, adaptive PID controllers are increasingly receiving attention from scholars. In 2016, Majid et al. [

7], aiming to enhance the response speed of PID controllers, proposed a fuzzy adaptive PID controller, with simulation results demonstrating that it exhibited superior stability compared to standard PID controllers. In 2023, Zhang et al. [

8], aiming to improve the control accuracy of USV under the influence of disturbances such as wind, waves, and currents, proposed a dynamic positioning method based on adaptive fuzzy PID control, effectively compensating for these environmental disturbances. In 2023, Lai et al. [

9], aiming to achieve advanced automation of USVs, proposed an intelligent adaptive PID controller based on proximal policy optimization (PPO). In 2024, Q. Xiang et al. [

10], addressed nonlinearity and uncertainty in USV heading control with a particle swarm optimization (PSO) and radial basis function (RBF) neural network strategy. In 2025, Zhan et al. [

11], boosted tracking accuracy under disturbances and delays with a hybrid heuristic-optimized adaptive PID controller.

Although the aforementioned research in the field of adaptive control has achieved significant results, the challenge of balancing multiple objectives—namely, tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and system energy consumption—under external disturbances persists, thereby constraining overall control performance. The aforementioned guidance and control methods have improved the path tracking accuracy of USV to varying degrees; however, under conditions of external environmental disturbances, existing methods struggle to achieve an effective balance among multiple objectives, including tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and system energy consumption.

It is noteworthy that, in order to address the issue of multi-objective optimization, game theory and quantum-inspired optimization are emerging as effective approaches to solving this problem [

12,

13,

14]. Game theory, analyzing decision-making interactions, suits multi-objective optimization [

15,

16,

17]. Quantum-inspired optimization demonstrates significant advantages in maintaining population diversity, improving optimization speed, and avoiding premature convergence [

18,

19,

20].

Addressing the aforementioned problems, this paper proposes an anti-disturbance path tracking control method integrating quantum-inspired optimization and dynamic game theory. This method comprises a two-layer optimization architecture: the upper layer, based on dynamic game theory, optimizes the guidance process by modeling the optimization problem of the look-ahead distance () and switching radius () in the LOS guidance algorithm as a non-cooperative game, achieving adaptive adjustment to path changes and environmental disturbances through the solution of its Nash equilibrium. The lower layer, based on a quantum-inspired optimization algorithm, enhances the control process by employing quantum bit probability amplitude encoding for the PID parameter space and utilizing a quantum rotation gate mechanism for efficient global search, achieving online self-tuning of PID parameters under environmental disturbances.

The primary novelty of the proposed scheme lies in the integrated two-layer hierarchical architecture that simultaneously achieves multi-objective coordinated optimization in both guidance and control layers under external disturbances. Unlike prior adaptive LOS methods, which primarily optimize single parameters (e.g., error or sideslip) for improved accuracy in specific scenarios, the upper-layer GTLOS models the joint optimization of look-ahead distance () and switching radius () as a non-cooperative game, solving for the Nash equilibrium to balance tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and energy efficiency. This game-theoretic approach enables adaptive response to path curvature variations and disturbances without relying on heuristic rules.

In the control layer, while optimization-based PID tuning methods (e.g., fuzzy, PPO, PSO, or hybrid heuristic) demonstrate adaptive disturbance rejection, they often focus on single-objective improvements or suffer from local optima/premature convergence. The lower-layer QIO leverages quantum bit probability amplitude encoding and rotation gate updates for efficient global search and population diversity, enabling real-time (1.5 s interval) online self-tuning with superior multi-objective balance.

The integrated framework is the first to combine dynamic game theory for LOS parameter coordination with quantum-inspired optimization for PID tuning in USV path tracking, yielding demonstrated superior comprehensive performance across accuracy, smoothness, and energy metrics.

The main contributions of this paper include the following:

- (1)

Apply non-cooperative game models to optimize the look-ahead distance () and switching radius () in LOS guidance algorithms and achieve adaptive adjustment to path changes and environmental interference by solving their Nash equilibrium;

- (2)

Using a quantum-inspired optimization algorithm to achieve real-time optimization of PID parameters, thereby enhancing resistance to external disturbances;

- (3)

Through simulation verification, this method has superior performance in tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and system energy consumption.

2. USV Model and Game Theory-Based LOS Algorithm

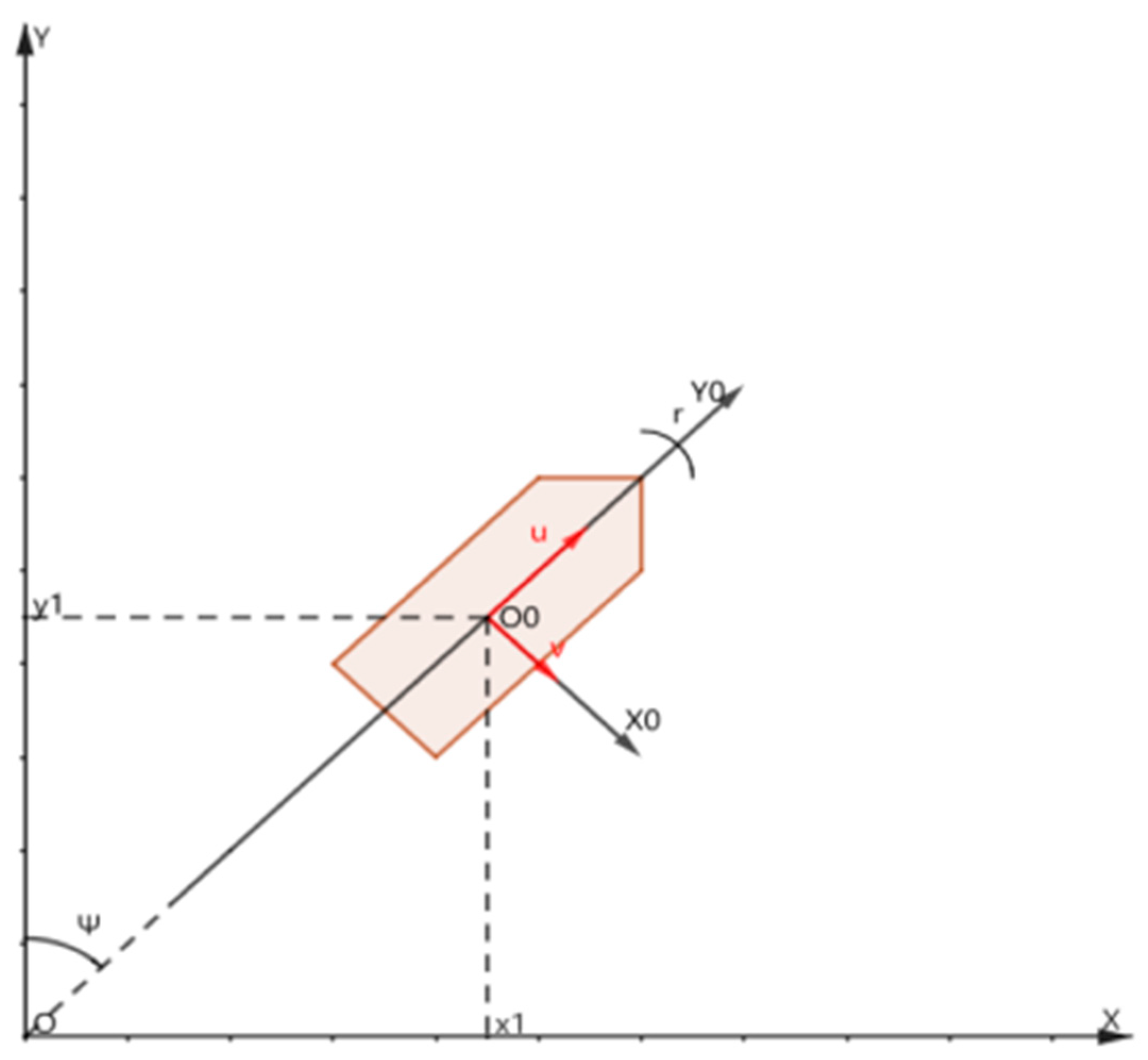

To focus on the path tracking control problem and reduce design complexity, this study simplifies the USV’s six-degree-of-freedom motion to a three-degree-of-freedom (3-DOF) motion in the horizontal plane, encompassing surge, sway, and yaw. To characterize the motion posture and dynamic relationship of the USV, this study defines two coordinate systems: the earth-fixed reference coordinate system (O-X-Y) and the body-fixed coordinate system (O0-X0-Y0). The 3-DOF dynamics and kinematics model of the USV is expressed as Equation (1), with the coordinate diagram depicted in

Figure 1.

Here is defined as the inertia parameter including added mass, represents the hydrodynamic damping coefficient. The total external disturbance torque is denoted as , which includes wind, wave, and current effects.

The core principle of the traditional LOS guidance law is based on calculating a desired heading angle

to enable the USV to converge to the desired path. Its expression is given by Equation (2):

where

is defined as the tangent angle of the current path point,

represents the lateral tracking error, and

is defined as the look-ahead distance (

).

The LOS guidance process, in broad terms, involves calculating the desired heading angle and directing the USV to proceed in that direction; when the distance between the USV and the current target path point is less than the preset switching radius (), the guidance system automatically switches the tracking target to the next path point, thereby achieving continuous tracking of the entire path.

In traditional LOS guidance algorithms, the parameters and are typically configured as fixed values, posing challenges for adaptation to complex external environments. The value of directly impacts system performance: a smaller can enhance tracking precision but may cause oscillations and increase control energy consumption, whereas a larger helps improve motion smoothness but may lead to tracking lag, potentially affecting accuracy. The switching radius () determines the timing of path point switching and significantly affects tracking accuracy and control smoothness.

The fixed and fail to achieve an ideal balance among tracking accuracy, motion smoothness, and control energy consumption. To address this, this paper proposes an adaptive LOS algorithm based on game theory, designated as the GTLOS (Game-Theoretic Line-of-Sight Algorithm, GTLOS) algorithm. The GTLOS algorithm builds upon the LOS algorithm by incorporating the strategy optimization concept from game theory, thereby enhancing the USV’s capability for coordinated optimization of multiple objectives under complex conditions.

The specific implementation of the GTLOS algorithm is as follows: it is implemented by selecting the look-ahead distance () and switching radius () as parameters to participate in a game, modeling them as a two-player non-cooperative game model. The advantage of this modeling approach lies in its ability to simultaneously consider the balance of multiple performance indicators, including tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and system energy consumption, and to obtain the system’s optimal solution through the solution of the Nash equilibrium.

Within this game-theoretic framework, two players are required: Player 1 is responsible for selecting the look-ahead distance (), and Player 2 is responsible for selecting the switching radius ().

The strategy space is defined as the range of parameter values that the two players can select. Based on the dynamic characteristics of path curvature, the strategy space is divided into two regions (S1 and S2) to enable adaptability in path tracking. The curvature threshold is set to , determined through simulation, and this threshold divides the strategy into the S1 region with curvature greater than 0.05 and the S2 region with curvature less than or equal to 0.05; this division contributes to balancing accuracy and stability.

For the 1.5 m long USV used in this study, the curvature threshold of corresponds to a radius of curvature of , or 13.3 times the vehicle length. This value effectively separates gentle curves (where larger look-ahead distances are preferred for smoothness and energy efficiency) from moderate-to-sharp turns (where reduced and are required to ensure tracking accuracy and prevent corner-cutting).

Parameter ranges for both strategies, determined via simulations, ensure efficient searches within a feasible solution space, as shown in Equation (3):

The payoff function serves as the cornerstone of this game, playing a pivotal role in evaluating the merits of various strategy combinations. This assessment hinges on the USV’s current state, utilizing its dynamic model to simulate future motion trajectories and control inputs. The resulting predictions are then used to compute the payoff function’s magnitude, providing a clear basis for judging the performance of different parameter sets. The design of the payoff function is outlined as follows:

Here represents the weighting parameter.

represents the integrated path error over the next steps, serving as a measure of tracking accuracy.

denotes the integrated control energy consumption, reflecting the efficiency of the control process.

represents the smoothness cost, penalizing abrupt changes in control inputs.

Payoff function: “The payoff function (Equation (4)) is evaluated by simulating the USV’s future motion over a prediction horizon of 100 steps using the 3-DOF model. For each candidate (, ) pair, the model integrates forward from the current state, applying a temporary fixed-gain PID controller to compute predicted trajectories, tracking errors, control inputs”.

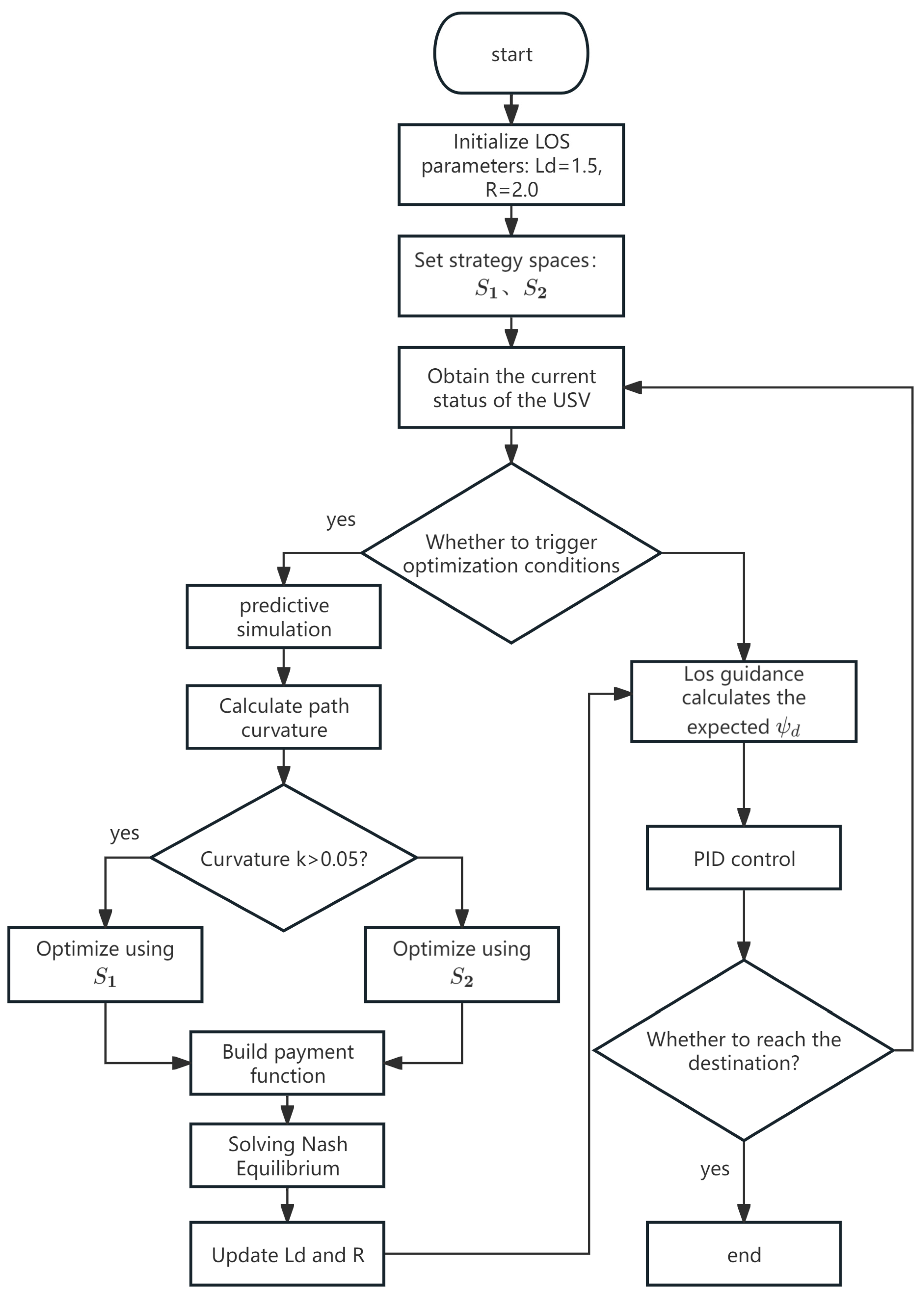

The flowchart of the GTLOS algorithm is presented in

Figure 2.

The solution to this game is to find the Nash equilibrium point

. The so-called Nash equilibrium refers to a strategy combination where no player can improve their payoff by unilaterally changing their own strategy. Its mathematical expression must satisfy the following conditions:

During the search for the Nash equilibrium point within the strategy space, the update step sizes for the and are set to 0.2 and 0.1, respectively.

The grid step sizes are set to 0.2 m for the look-ahead distance and 0.1 m for the switching radius . These values were determined through extensive simulation experiments as a compromise between optimization precision and computational efficiency:

Finer steps (e.g., 0.1 m for and 0.05 m for ) yield marginally better performance (<3% improvement in path deviation) but double the number of grid points and evaluations, increasing computation time proportionally.

Coarser steps (e.g., >0.4 m) lead to noticeable degradation in tracking smoothness during curved paths (increased overshoot or corner-cutting by 20%). The chosen steps ensure sufficient resolution for effective multi-objective balance (accuracy vs. smoothness vs. energy) while keeping the typical search space at 20~30 points per dimension (<900 total evaluations).

Optimization is triggered every 15 s (basic trigger) or immediately upon unexpected large deviations (>2.5 times historical average path deviation). This interval was selected based on simulation trials considering USV dynamics and environmental variation rates:

Shorter intervals (<10 s) provide negligible additional benefits but unnecessarily increase computational load. Longer intervals (>20 s) result in delayed adaptation to path curvature changes or gradual disturbance shifts, slightly degrading tracking accuracy (5~10% higher mean error in sine/circular paths).

The 15 s aligns well with the typical time scale of moderate sea state variations and USV maneuver responses (e.g., settling time 10~20 s for heading changes), ensuring timely parameter updates without overburdening onboard resources.

3. Design of USV Path-Tracking Control Algorithm

Traditional PID controllers with fixed parameters often exhibit significant performance degradation when subjected to external environmental disturbances. They struggle to maintain a balance between control accuracy, smoothness, and energy efficiency in dynamically changing environments. To effectively address this issue, this study introduces a Quantum-Inspired Optimization (Quantum-Inspired Optimization, QIO) method. The core idea of QIO is to map the probability amplitudes of quantum bits onto the PID parameter space and to guide the search direction through a quantum rotation gate mechanism, thereby obtaining an optimal parameter combination that can effectively suppress environmental disturbances while achieving multi-objective performance balance.

The QIO algorithm is applied for the online tuning of PID parameter controller parameters. The design process is as follows:

Each PID parameter is encoded as a quantum bit using a quantum angle encoding scheme. The conversion relationship between the quantum angle and the parameter value is defined as follows:

Here , , and . The initial angle is set to , ensuring that corresponds to the midpoint of each parameter’s search range. This encoding approach guarantees both the comprehensiveness and diversity of the search process. The determination of the PID parameter range is obtained by simulating and testing the control efficiency of traditional PID under different sea conditions.

The quantum observation process is employed to convert the quantum state into a classical solution. For each quantum bit, a random number

is generated, and the observation rule is defined as follows:

This process generates a population

consisting of 12 candidate solutions, where each individual represents a set of PID parameter combinations. The mutation probability for each individual is set to 3%, resulting in an overall mutation probability of approximately 36% per optimization iteration. In other words, a mutation typically occurs once every three optimization cycles. During the mutation process, one of the three PID parameters

is randomly selected to mutate. Its value is then increased or decreased by a certain proportion, with the probability of each outcome as shown in

Figure 3, which is determined according to the following formula:

Based on this, the historically best-performing parameter combination is added, resulting in a total of 13 individuals in the population. The performance of these 13 individuals is then evaluated. To comprehensively assess the performance of a given parameter set, the following fitness function is designed:

where

represents the weighting coefficient.

penalizes persistent errors, encouraging the system to stabilize quickly.

penalizes control energy consumption, ensuring smooth control and preventing actuator saturation.

ensures system stability, avoiding severe oscillations.

enhances system smoothness, reducing output fluctuations.

To ensure real-time and rapid evaluation, historical operational data within a recent time window are used to assess the parameters, rather than performing a full simulation. The length of the recent data is determined based on simulation experiments, but at least 600 pieces are required. When evaluating a set of PID parameters , a temporary PID controller is created, and the error sequence from the historical data is used as its input. The output of this temporary controller is then used to compute the performance metrics for the parameter set. This approach significantly reduces computational overhead and meets the real-time requirements of online optimization.

The quantum rotation gate mechanism represents the learning and evolution phase of the QIO algorithm. Based on the fitness evaluation results described above, the quantum angles are strategically updated using the quantum rotation gate, guiding the probability amplitudes toward regions corresponding to high-performing solutions. The update formula is given by

where

If the current optimal solution indicates that a parameter needs to be increased, is adjusted to increase the value of , thereby raising the probability of observing a larger parameter value in the next iteration.

Optimization Procedure: The process begins with initialization, where the PID parameter ranges, the number of quantum bits (3), and the quantum population size (13) are set. The algorithm then enters the iterative optimization phase, executing the observation, evaluation, and update steps sequentially:

Observation: Classical PID candidate solutions are generated from the quantum states via quantum observation.

Evaluation: The fitness of each candidate is calculated using historical operational data, with emphasis on assessing multi-objective performance.

Update: Based on the fitness results, the quantum angles are adjusted using the quantum rotation gate, guiding the search toward regions with high-performing solutions that better balance the multi-objective criteria.

Finally, the best solution from all generations, or the current optimal solution, is selected. After smoothing through a first-order low-pass filter, the updated parameters are applied to the PID controller, as follows:

Here, is a smoothing factor used to prevent abrupt parameter changes that could induce system oscillations, thereby further ensuring control smoothness. Based on multiple simulation trials, is set to 0.9.

The QIO algorithm optimizes the PID parameters at a frequency of once every 1.5 s. This frequency is determined by fully considering the fast characteristics of the QIO algorithm and has been validated through extensive simulation experiments. At this update rate, real-time self-tuning of PID parameters is achieved while minimizing computational resource consumption.

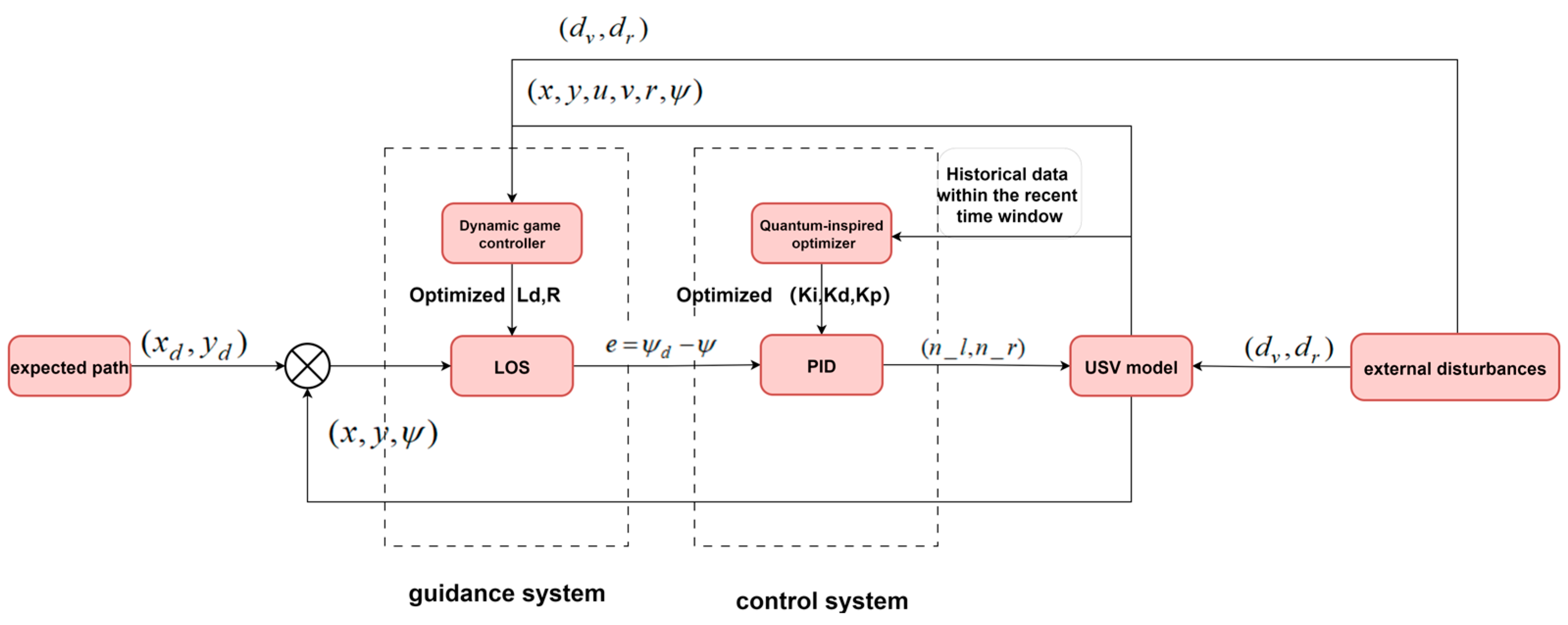

By integrating the GTLOS guidance algorithm with the QIO-PID control algorithm, a path-tracking control architecture for the unmanned surface vehicle is established, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

As shown in

Figure 4, the controller operates in two layers:

Guidance system layer: Desired waypoints and current states are fed into the GTLOS module, which solves a non-cooperative game to obtain adaptive look-ahead distance and switching radius . These parameters are used by the LOS law to generate desired heading ψd.

Control system layer: The QIO algorithm continuously self-tunes PID gains using historical data within the recent time window. Heading error enters the QIO-PID controller, to produce .

is the thrust of the left and right propellers, are applied (lateral) and (yaw) to represent significant wind, wave, and current effects. The are obtained by dividing the estimated external forces and moments acting on the USV by the corresponding inertial parameters and , respectively.

4. Simulation Results and Analysis

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, simulation experiments were conducted in a Python3.8 environment and compared with the conventional fixed-parameter PID-LOS approach. In the body-fixed frame, environmental disturbances were set as (lateral) and (yaw).

The constant disturbances applied in the simulations for the 1.5 m long USV are equivalent to a lateral (sway) force of approximately 16.8 N and a yaw moment of 10.3 N.m. These values correspond to moderate sea states (Beaufort scale 4~5, with wind speeds of 8~13 m/s and significant wave heights of 1~2 m), which are typical for small USV in coastal or sheltered waters during routine operations. Such disturbance magnitudes align well with reported values in the literature on simulations and experiments for comparable small USVs (1~2 m class). Wind, wave, and current effects often induce persistent lateral forces in the range of 5~20 N and yaw moments of 2~15 N.m under similar moderate conditions, as observed in studies involving dynamic positioning, path tracking, and station-keeping tests.

Although the use of constant disturbances simplifies the steady-state analysis and clearly demonstrates the proposed method’s adaptive compensation capabilities, real-world ocean environments involve more complex time-varying and stochastic components (e.g., wave-induced oscillations, gusty winds, and irregular currents). Future work could extend the framework by modeling these as process noise (for dynamic environmental variations) and measurement noise (for sensor uncertainties), potentially incorporating spectral models like JONSWAP for waves to further validate robustness in fully dynamic rough seas.

The weighting parameters for the payoff and fitness functions were set as follows: for the payoff function (Equation (4)), the weights were 0.7, 0.2, and 0.1, reflecting a design philosophy that prioritizes tracking accuracy while considering system energy consumption. For the fitness function (Equation (14)), the weights were 0.6, 0.2, 0.1, and 0.1, reflecting a design principle that emphasizes tracking accuracy while also accounting for control efficiency. These weighting parameters were determined through extensive simulation experiments, based on the design philosophy mentioned above.

4.1. Straight-Line Path Control

The expression of the straight-line path to be tracked is given by

The USV’s initial position is

, initial heading angle

, and initial velocity

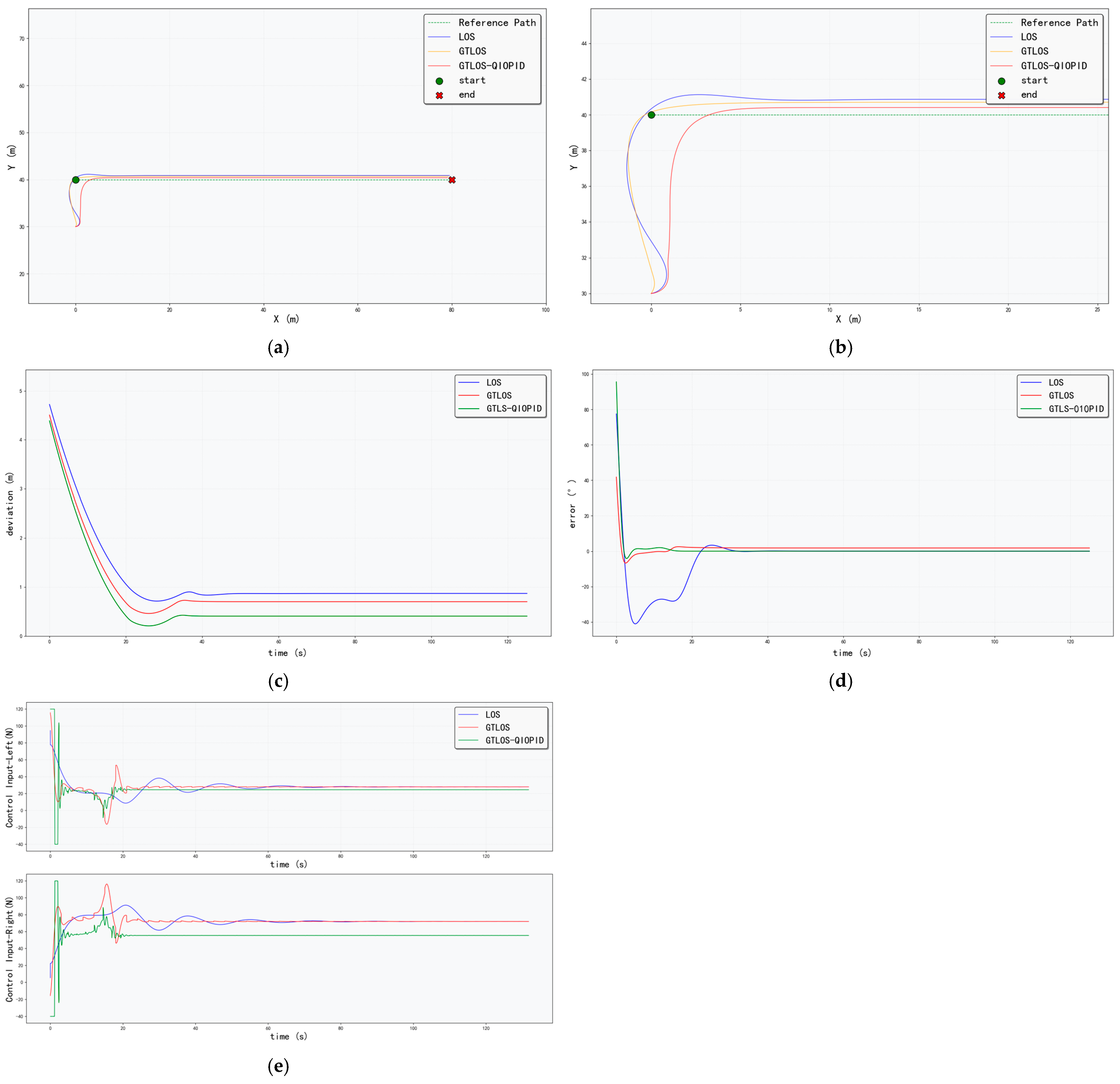

. The simulation results for different methods are shown in

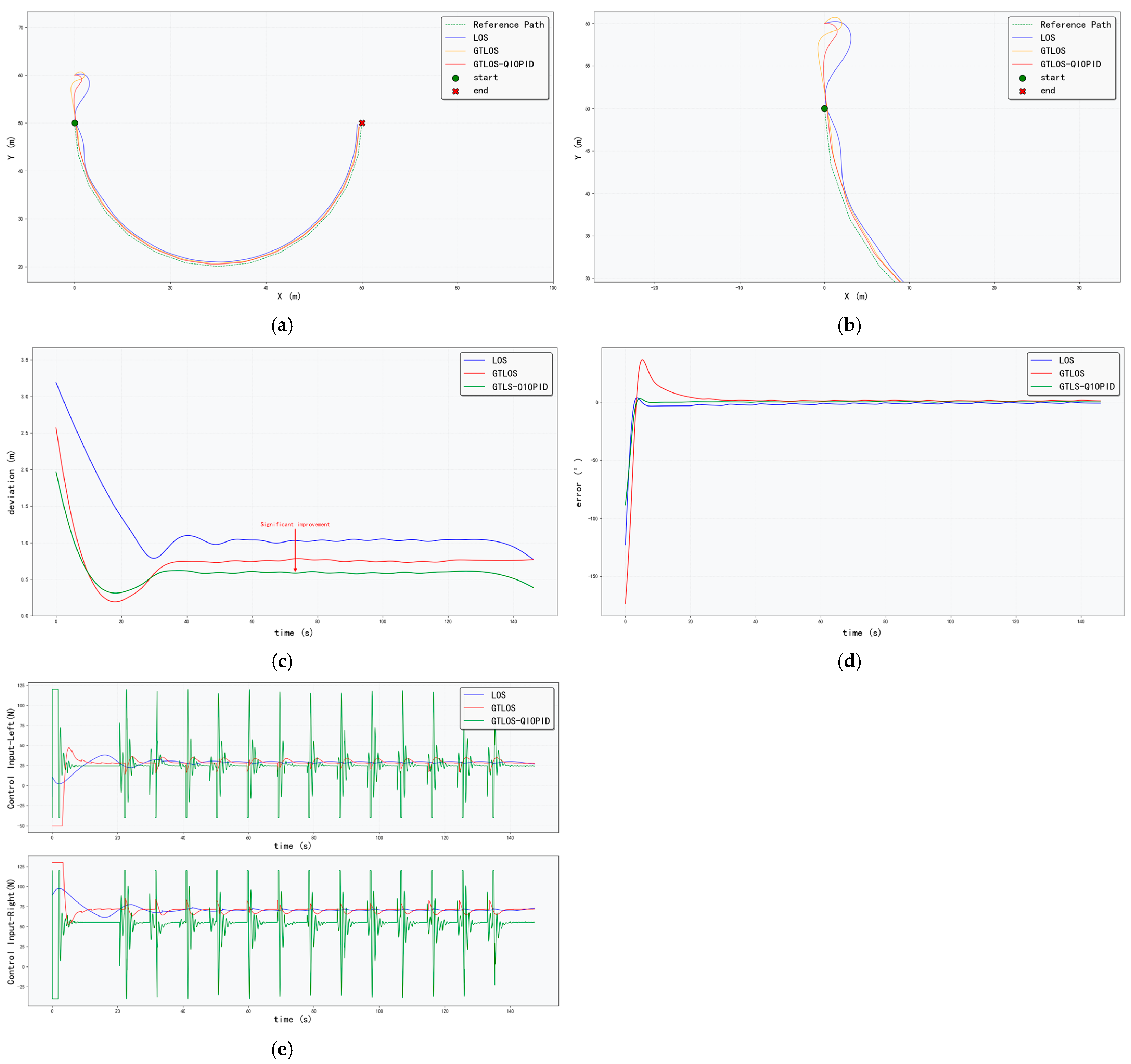

Figure 5, with statistical data on path deviation and heading error summarized in

Table 1, and control data presented in

Table 2.

As shown in

Table 1, the GTLOS-QIO-PID method demonstrates the best performance in terms of tracking accuracy. Its mean path deviation of 0.8727 is 40.1% lower than that of the conventional LOS-PID method (1.4563). Moreover, the GTLOS-QIO-PID method exhibits superior stability in error performance, with a path deviation variance of 1.6780, the smallest among all compared methods.

In terms of heading control performance, the GTLOS-QIO-PID method also achieves the best results. Its mean heading error of 0.0140 is the lowest, representing an 83.8% reduction compared with the conventional method, while the variance (0.1003) remains relatively small, further confirming its stability advantage.

Further analysis of the control input data in

Table 2 shows that for the GTLOS-QIO-PID algorithm, the left propeller has a total thrust of 329,308 and an average thrust of 24.99, both significantly lower than those of the conventional LOS-PID method (total thrust 364,816, average thrust 27.69). Similarly, the right propeller achieves a total thrust of 741,674 and an average thrust of 56.29, also notably lower than the LOS-PID method (total thrust 952,783, average thrust 72.31).

Path deviation is defined as the perpendicular distance from the USV’s current position to the current segment of the straight path being tracked (from to ).

Considering the data from

Table 1 and

Table 2, the GTLOS-QIO-PID method effectively balances tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and system energy consumption, demonstrating strong overall performance.

4.2. Circular Path Control

The expression of the Circular path to be tracked is given by

The USV’s initial position is

, initial heading angle

, and initial velocity

. The simulation results for different methods are shown in

Figure 6, with statistical data on path deviation and heading error summarized in

Table 3, and control data presented in

Table 4.

As shown in

Table 3, the GTLOS-QIO-PID method demonstrates the highest path-tracking accuracy, with a mean path deviation of 0.604, representing a 48.7% reduction compared with the conventional LOS-PID method (1.177). In terms of error stability, the GTLOS-QIO-PID method also performs best, with a path deviation variance of only 0.309, the smallest among all methods.

For heading control, the GTLOS-QIO-PID method again achieves superior performance, with a mean heading error of 0.027, the lowest value, corresponding to a 79.9% reduction compared with the conventional method, and a variance of 0.165, also the smallest. A combined analysis of path deviation and heading error indicates that the GTLOS-QIO-PID method offers a clear advantage in path-tracking accuracy. Further inspection of the tracking trajectories and zoomed-in views shows that the path under this method is smoother.

Analysis of the control input data in

Table 4 shows that for the GTLOS-QIO-PID algorithm, the left propeller has a total thrust of 439,613 and an average thrust of 29.81, slightly higher than the conventional LOS-PID method (total thrust 417,709, average thrust 28.33). The right propeller, however, achieves a total thrust of 818,776 and an average thrust of 55.52, significantly lower than the LOS-PID method (total thrust 1,057,018, average thrust 71.68). Overall, the GTLOS-QIO-PID method distributes thrust more effectively, notably reducing the demand on the right propeller, which contributes to lower overall system energy consumption.

Taken together, these results indicate that the method successfully balances tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and energy efficiency, demonstrating excellent overall performance.

4.3. Sine Path Tracking Control

The expression of the sine path to be tracked is given by

The USV’s initial position is

, initial heading angle

, and initial velocity

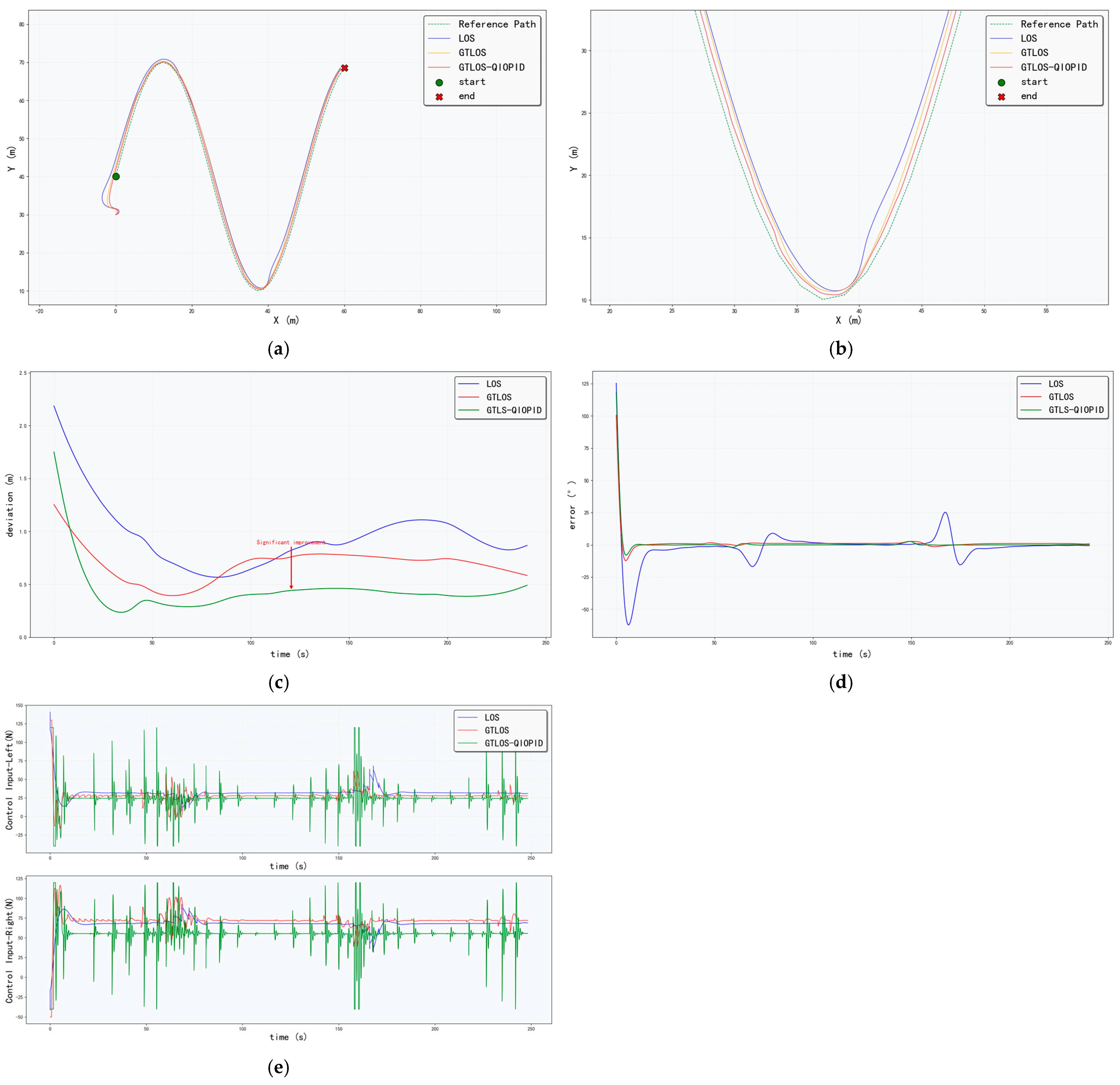

. The simulation results for different methods are shown in

Figure 7, with statistical data on path deviation and heading error summarized in

Table 5, and control data presented in

Table 6.

In terms of path-tracking accuracy, the GTLOS-QIO-PID method outperforms all other approaches, with a mean path deviation of 0.437, representing a 54.2% reduction compared with the conventional LOS-PID method (0.954). Additionally, it demonstrates superior error stability, with a path deviation variance of only 0.202, the smallest among all methods.

For heading control, the GTLOS-QIO-PID method also excels, achieving a mean heading error of 0.021 and a maximum error of 1.571, both the lowest values. Compared with the conventional method, the mean error decreases by 78.8%, and the variance is also minimized. A combined analysis of path deviation and heading error confirms that the GTLOS-QIO-PID method has a clear advantage in path-tracking precision. Detailed examination of the tracking trajectories and their zoomed-in views further reveals that the path under this method is smoother.

Analysis of the control input data in

Table 6 shows that for the GTLOS-QIO-PID method, the left propeller has a total thrust of 652,765 and an average thrust of 26.29, while the right propeller achieves a total thrust of 1,398,031 and an average thrust of 56.31. Both are significantly lower than those of the conventional LOS-PID method, indicating that this method achieves high-precision tracking while substantially reducing overall system energy consumption.

Overall, the GTLOS-QIO-PID algorithm effectively balances tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and energy efficiency under external disturbances, demonstrating stronger multi-objective optimization capabilities.

From the results of the three path simulation experiments, it is evident that the GTLOS-QIO-PID method consistently outperforms the traditional fixed-parameter LOS-PID approach in terms of tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and system energy consumption. For the design of certain key parameters, this paper primarily relies on two methods: numerical computation and observations from simulation experiments.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

To address the challenge of achieving an effective balance among tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and system energy consumption under external disturbances, this study proposes an anti-disturbance path-tracking control method that integrates Quantum-Inspired Optimization (QIO) with Dynamic Game Theory (GT). The paper details the implementation of a game-theory-based LOS guidance algorithm and a quantum-inspired adaptive PID controller.

Simulation results demonstrate that the GTLOS-QIO-PID method significantly outperforms the conventional fixed-parameter PID-LOS approach in terms of path-tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and overall system energy efficiency. Although the proposed method achieves an excellent balance among tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and energy efficiency, the inherent multi-objective trade-off implies that performance dimensions not explicitly included in the payoff/fitness functions may be indirectly compromised. Specifically, excessively aggressive optimization of energy-related weights can lead to marginally increased actuator wear and higher peak thrust demands during sharp maneuvers, while over-emphasis on smoothness may slightly prolong convergence time under sudden large disturbances. Future work will address these limitations by (i) incorporating actuator constraints directly into the game-theoretic payoff and QIO fitness functions using penalty terms or barrier functions, (ii) introducing additional objectives or hierarchical weighting strategies that dynamically prioritize objectives according to mission phase, and (iii) extending the framework to explicit multi-objective Pareto optimization techniques to provide a set of non-dominated solutions for different operational requirements.

Looking ahead, the proposed control method could be extended to formation control, enabling multi-objective balance in formation path tracking. Additionally, real-world trials are planned to validate the method’s effectiveness in practical environments.