Research on Risk Assessment and Prevention–Control Measures for Immersed Tunnel Construction in 100 m-Deep Water Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

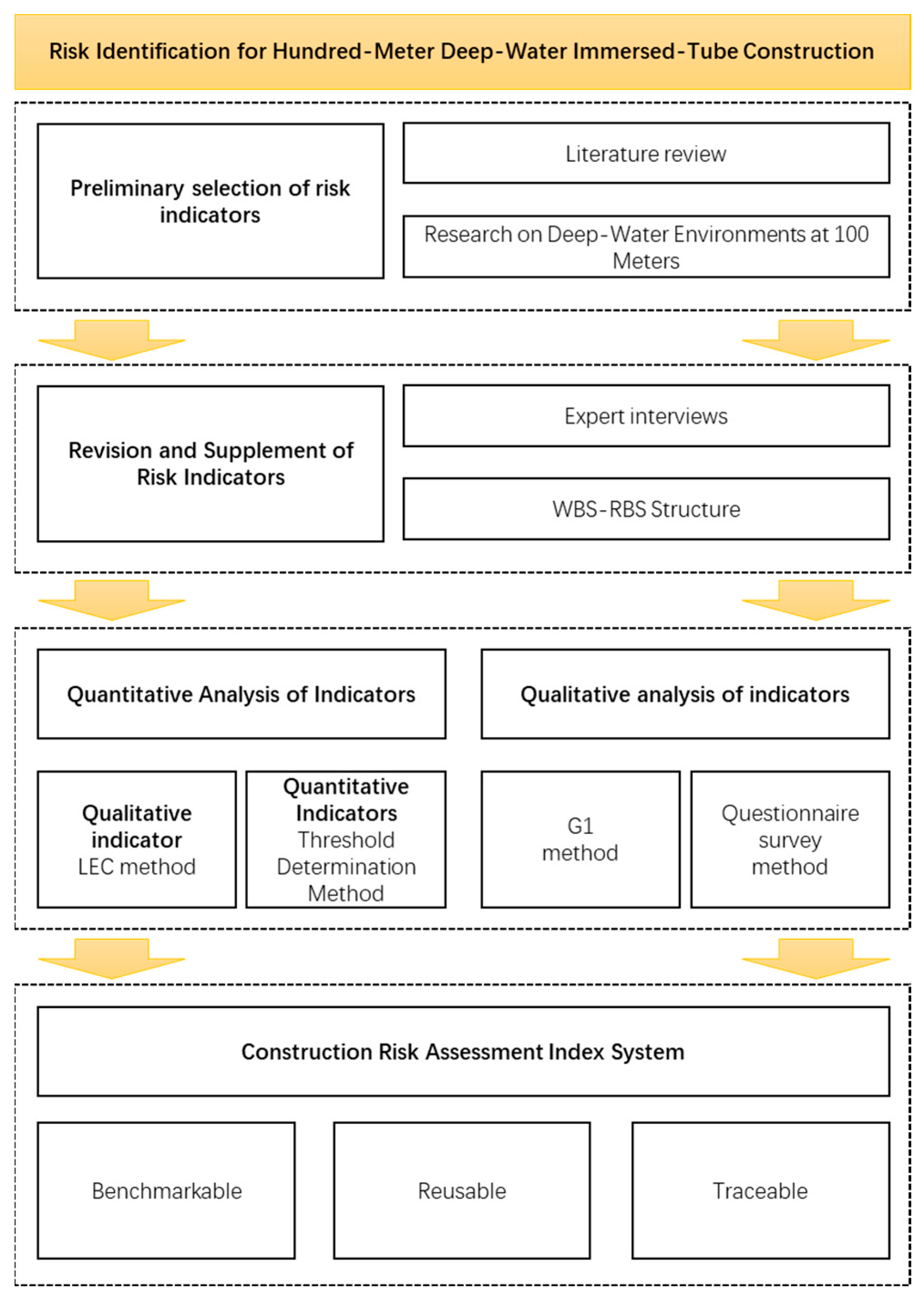

2. Literature Review

3. Method

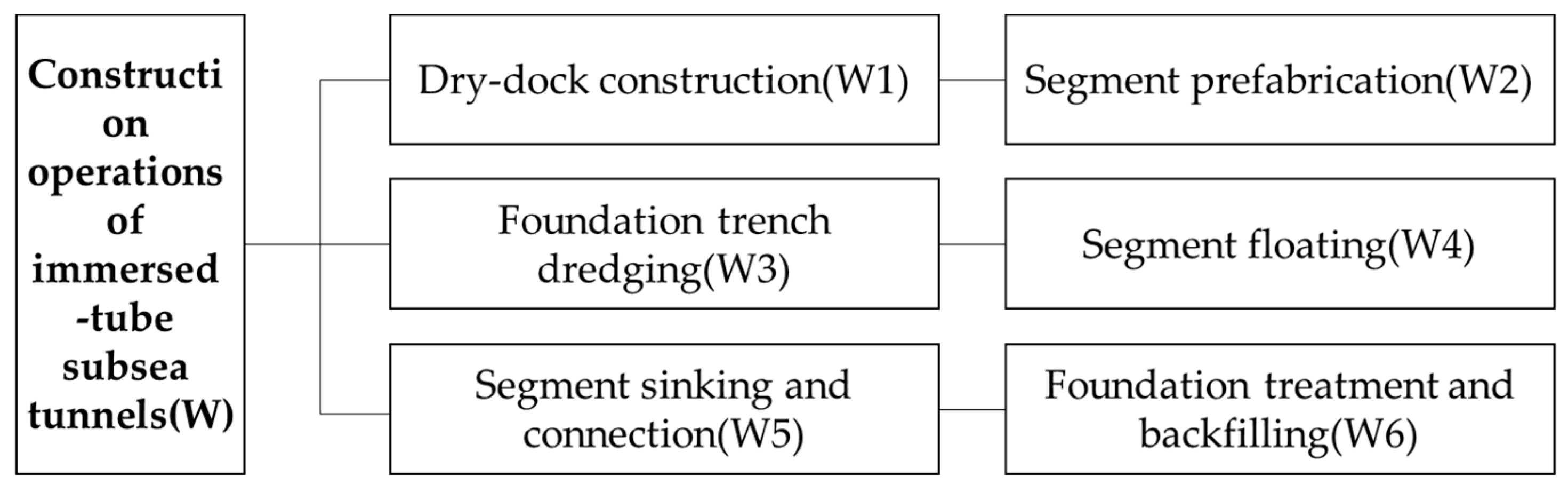

3.1. Work Breakdown Structure

- Dry-dock construction: Construction is carried out within an enclosed dry dock, where cofferdams and drainage systems are used to create a water-free environment for segment prefabrication and auxiliary facility installation. This stage requires high construction precision and is significantly affected by tidal variations and water-level fluctuations.

- Segment prefabrication: Immersed tube segments are prefabricated in the dry dock or a specialized pre-casting yard according to design specifications. The process involves reinforcement assembly, concrete casting, and prestressing operations. Strict quality control is required to ensure the structural strength and watertightness of the segments.

- Foundation trench dredging: The seabed trench for the immersed tunnel is excavated at the designated alignment. This process demands precise control of depth, width, and slope, while coping with complex underwater geological conditions to prevent collapses and silt backfilling.

- Segment floating: The prefabricated segments are transported from the production site to the immersion location by floating them along a controlled route. Accurate control of the floating path, speed, and attitude is essential to avoid segment collision or tilting, while simultaneously responding to complex natural conditions such as currents, waves, and wind.

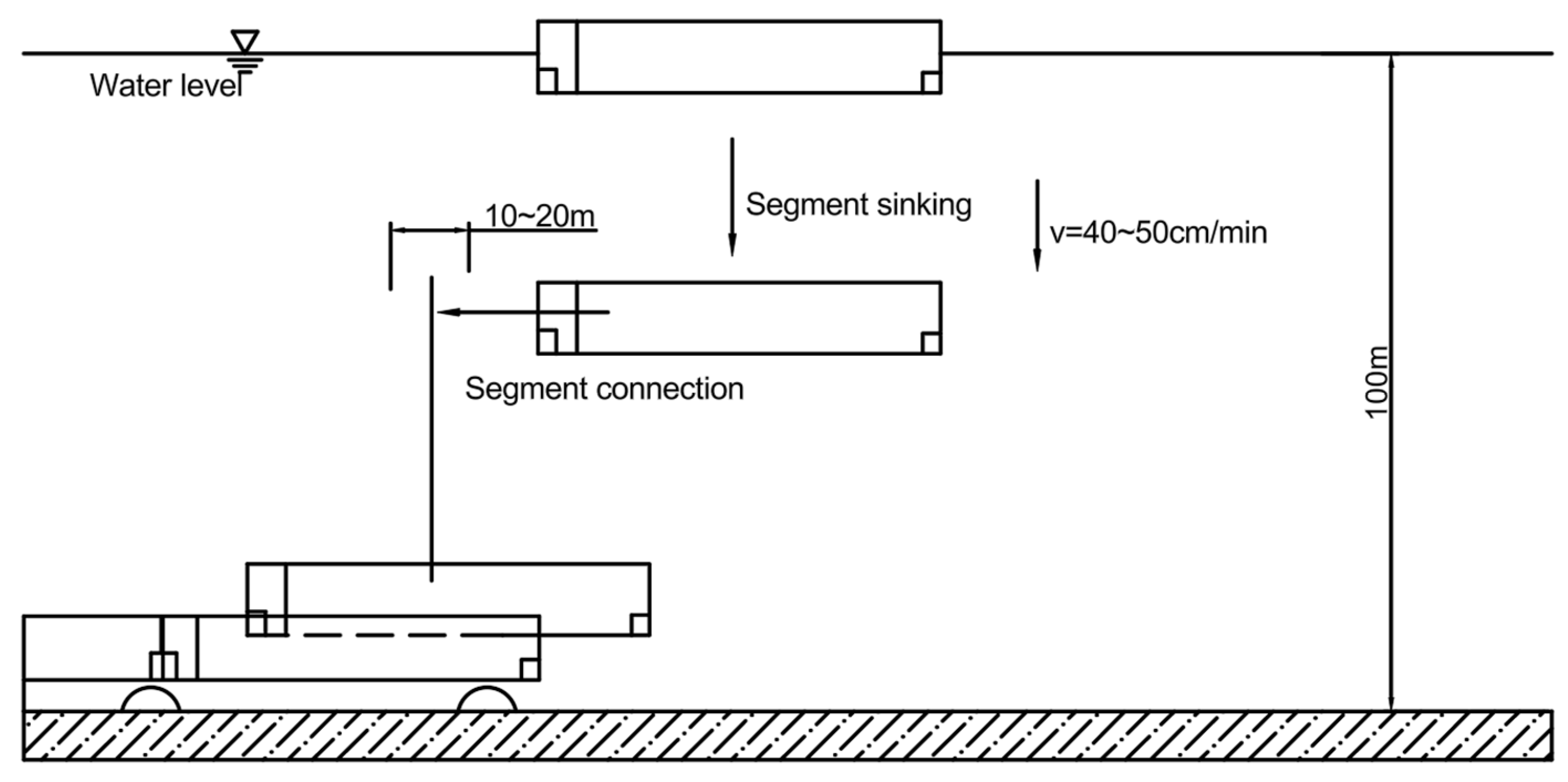

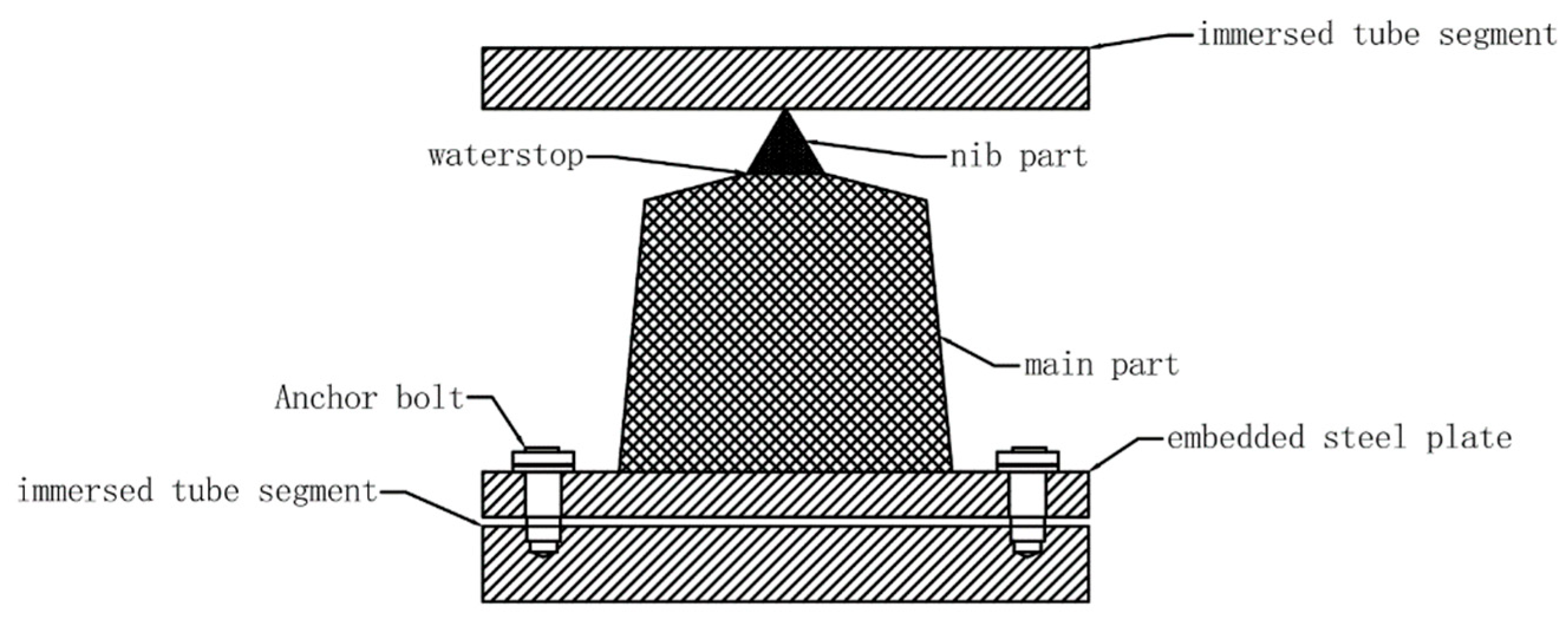

- Segment sinking and connection: Each segment is carefully lowered into the predetermined position within the foundation trench and connected to the previously installed segment. This stage requires precise control of the sinking posture, connection alignment, and watertight sealing. The process is highly sensitive to underwater environmental conditions and the precision of construction equipment. The specific process is shown in Figure 2.

- Foundation treatment and backfilling: The underwater foundation is stabilized through operations such as stone dumping, gravel bedding, and grouting reinforcement. Afterward, the sides and top of the immersed tube are backfilled. The objective is to ensure uniform bearing capacity and structural stability, preventing uneven settlement or localized stress concentration.

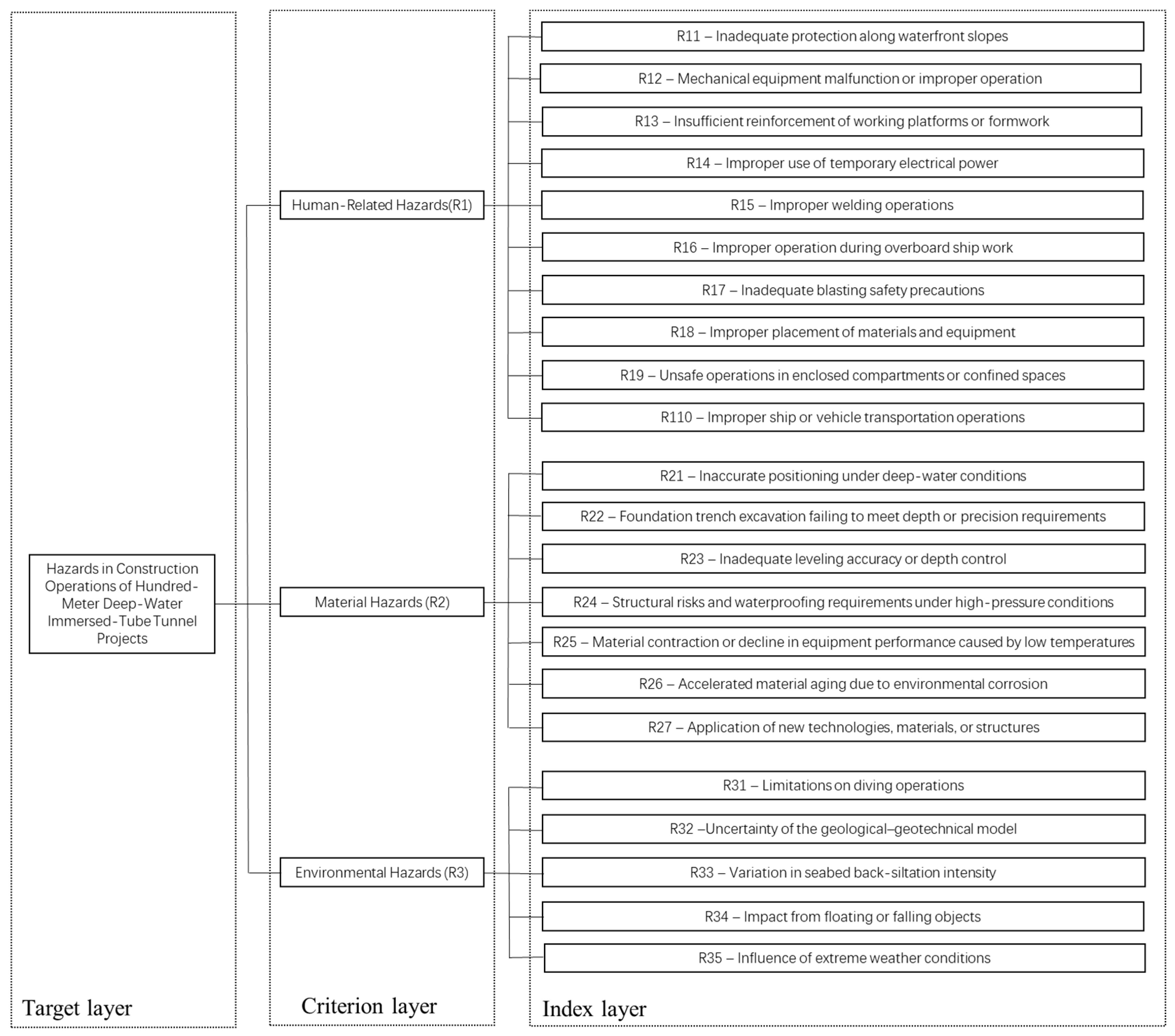

3.2. Risk Breakdown Structure

3.3. WBS-RBS Coupling Matrix

4. Quantification of Risk Indicators and Determination of Weights

4.1. Risk Quantification

4.1.1. Qualitative Indicators

4.1.2. Quantitative Indicators

- Δ ≤ 1 cm (Optimal);

- Δ: 1–2 cm (Acceptable);

- Δ: 2–5 cm (Warning);

- Δ > 5 cm (Out of tolerance).

- Hydrostatic pressure formula:

- 2.

- Dynamic water pressure formula:

- (a)

- Water pressure: 0.8–0.9 MPa is near the limit and requires verification;

- (b)

- Water pressure: 0.9–1.0 MPa is a high-risk zone;

- (c)

- Water pressure ≥ 1.0 MPa is over the limit, requiring the use of new waterstop structures and materials.

- (a)

- A water depth ≤ 40 m is no significant limitation;

- (b)

- A water depth: 40–60 m is a noticeable limitation;

- (c)

- A water depth > 60 m is a severe limitation.

4.2. Weight Assignment

- (1)

- Determine the three indicator levels and establish the order of importance among the indicators. The order of importance is determined by an expert group, expressed as follows:

- (2)

- Determine the relative importance between adjacent indicators, as expressed by the following equation:

- (3)

- Calculate the weights of the three indicator levels and their corresponding indicators. After the expert group provides all the values of rₖ (k = 2, 3, …, n), the weight of indicator k and the remaining indicators are calculated using the following equation.

- (4)

- Calculate the comprehensive weight within each indicator level. The comprehensive weight can be determined using the following equation.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Results Reduction

5.2. Discussion

6. Prevention and Control Measures

- Structural and Material Prevention Measures: Structures in deep water endure long-term high hydrostatic pressure, making them prone to cracking and leakage. The adoption of steel shell–concrete composite structures should be promoted, leveraging the steel shell’s restraining effect to enhance the concrete’s crack and seepage resistance. Concurrently, high-performance concrete, seawater corrosion-resistant steel, and new waterstop materials should be utilized to improve durability. A multiple waterstop system comprising GINA, OMEGA, and end concrete is recommended for joints, ensuring safety redundancy even under 1 MPa high water pressure.

- Foundation Construction and Leveling Prevention Measures: Trench accuracy directly impacts sinking quality. To address the insufficient precision of grab dredgers and trailing suction hopper dredgers, spiral cutter-type underwater leveling machines can be developed to achieve refined leveling with an unevenness ≤ 4 cm. For bearing capacity, the composite foundation system of “pile foundation + pile cap + rubber bearing” should be promoted to enhance stability and reduce differential settlement. Simultaneously, flexible backfilling and multi-layer anti-scour protection measures should be employed to prevent back-siltation and ocean current scour.

- Element Installation and Joining Prevention Measures: Element alignment accuracy and waterstop performance are key focuses of construction control. Automatic docking guidance devices should be developed, integrating ball support and electromagnetic adsorption technology to achieve automatic joint positioning and reduce underwater manual operations. For joint design, a rigid–flexible combined system should be adopted: setting rigid or semi-rigid joints in key sections to enhance integrity, and arranging flexible joints in ordinary sections to release stress. Furthermore, developing highly elastic, low-creep, seawater-resistant rubber materials is essential for improving the long-term sealing performance of waterstop belts.

- Floating Transport and Sinking Prevention Measures: In deep-water environments, changes in wind, waves, and current fields significantly increase the risks during floating transport. Establishing a multi-mode floating transport support system, combining semi-submersible ships and transport-installation integrated vessels, and selecting flexibly based on working conditions is recommended. During the sinking process, multi-source technology integration—using BeiDou/GNSS, acoustic positioning, and laser alignment—should be applied to improve deep-water sinking accuracy. Furthermore, fluid–structure interaction numerical simulation should be utilized to predict forces and displacements during sinking, enabling the pre-formulation of contingency plans.

- Intelligent Monitoring and Risk Management: Traditional measurement towers are difficult to use under 100-m water depth conditions; thus, measurement-tower-free positioning systems based on hydroacoustic arrays and laser ranging should be developed. Simultaneously, a multi-parameter real-time monitoring platform should be established to collect and visualize data on attitude, forces, and environmental parameters during floating, sinking, and docking, supporting dynamic risk early warning. At the management level, a comprehensive HSE risk management system should be built, forming a closed-loop control mechanism covering the entire process from risk identification and dynamic assessment to early warning linkage.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, S.; Li, S.; Yu, F.; Wang, K. Risk Assessment of Immersed Tube Tunnel Construction. Processes 2023, 11, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Wang, J. Challenges and strategies involved in designing and constructing a 6 km immersed tunnel: A case study of the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macao Bridge. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 50, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fu, S.; Zhu, J.; Wang, J. Risk factors analyses and preventive measures of immersed tunnel engineering. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 236, 02025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, D.; Fabio, B.; Simone, F.; Alessio, F. Tram: A New Quantitative Methodology for Tunnel Risk Analysis. Chem. Eng. Trans. (CET J.) 2018, 67, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, F.; Ngai, C.; McLeod, J.; Hansen, J.; Morris, M.; Ozgur, O. Shatin to Central Link cross-harbour railway tunnel in Hong Kong. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 126, 104281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Putten, E.; van Os, P. The A24 Blankenburg connection: An innovative design concept for an immersed tunnel project in a busy port. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 124, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, T.; Kasper, T.; de Wit, J. Immersed tunnels in soft soil conditions experience from the last 20 years. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 121, 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozakgul, K.; Caglayan, O.; Tezer, O.; Uzgider, E. Remediation of settlements in a steel structure due to adjacent excavations. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2012, 20, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Gong, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Gong, C. Experimental investigation on mechanical behavior of segmental joint under combined loading of compression-bending-shear. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. Inc. Trenchless Technol. Res. 2020, 98, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, K.; Li, M.; Sun, Y.; He, C.; Xiao, M. Analytical method regarding compression-bending capacity of segmental joints: Theoretical model and verification. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. Inc. Trenchless Technol. Res. 2019, 93, 103083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Hu, X.; Walton, G.; He, C.; He, C.; Ju, J.W. Full scale tests and a progressive failure model to simulate full mechanical behavior of concrete tunnel segmental lining joints. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. Inc. Trenchless Technol. Res. 2021, 110, 103834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauduin, C.; Kirstein, A.A. Design, construction and monitoring of an underwater retaining wall close to an existing immersed tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 120, 104311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland, H.; Aven, T. Treatment of uncertainty in risk assessments in the Rogfast road tunnel project. Saf. Sci. 2013, 55, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, S. Risk Assessment of Operation Period Structural Stability for Long and Large Immersed Tube Tunnel. Procedia Eng. 2016, 166, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazaras, K.; Kirytopoulos, K. Challenges for current quantitative risk assessment (QRA) models to describe explicitly the road tunnel safety level. J. Risk Res. 2014, 17, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazaras, K.; Kirytopoulos, K.; Rentizelas, A. Introducing the STAMP method in road tunnel safety assessment. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 1806–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J. Application and Demonstration of Health-Safety-Environment Risk Management to Underwater Tunnel of Hong Kong-Zhuihai-Macao. Tunn. Constr. 2019, 39, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matasova, I.Y.; Yaitskaya, N.A.; Modina, M.A.; Brigida, V.S. Three-dimensional geoecological models in forecasting sea level on Black Sea coast of Caucasus. Geol. Geophys. Russ. S. 2024, 14, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polydoropoulou, A.; Velegrakis, A.; Papaioannou, G.; Karakikes, I.; Bouhouras, E.; Thanopoulou, H.; Chatzistratis, D.; Monioudi, I.; Moschopoulos, K.; Chatzipavlis, A. A composite port resilience index focused on climate-related hazards: Results from Greek ports’ living-labs. Marit. Transp. Res. 2025, 9, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Xu, M. Risk identification of subway tunnel shield construction based on WBS-RBS method. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. 2023, 19, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Niu, D.; Shen, J.; Wang, H. A Cost Risk Assessment Framework for UHV AC Projects Based on WBS-RBS-FAHP-COWA-Matter-Element Extension. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2025, 20, 2075–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Jeong, B.; Jang, H.; Kim, D.; Jee, J. An integrated qualitative–quantitative risk assessment for defining toxic and hazardous zones on hydrogen-fuelled ships with ammonia cracking systems. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 341, 122475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Yang, C. A systematic intelligent prediction model for residential construction cost based on fuzzy AHP and GA-BP neural network. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2026, 69, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. A Novel Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Model for Building Material Supplier Selection Based on Entropy-AHP Weighted TOPSIS. Entropy 2020, 22, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, Q.; Yang, L.; Cai, H. Risk assessment and management via multi-source information fusion for undersea tunnel construction. Autom. Constr. 2020, 111, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, W.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, R.; Bian, W. Research on environmental comfort and cognitive performance based on EEG+VR+LEC evaluation method in underground space. Build. Environ. 2021, 198, 107886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Gao, J.; Xu, S.; Tang, S.; Guo, M. Establishing an evaluation index system of Coastal Port shoreline resources utilization by objective indicators. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 217, 106003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RBS Decomposition System | WBS Decomposition System | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | W5 | W6 | |||

| Hazards in Construction Operations of Hundred-Meter-Deep Water-Immersed Tube Tunnel Projects | R1 | R11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| R12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| R13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| R14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| R15 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| R16 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| R17 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| R18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| R19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| R110 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| R2 | R21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| R22 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| R23 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| R24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| R25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| R26 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| R27 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| R3 | R31 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| R32 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| R33 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| R34 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| R35 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| L Value | Description |

|---|---|

| 0.1 | Practically impossible to occur in reality |

| 0.2 | Extremely unlikely to occur |

| 0.5 | Conceivable but highly improbable |

| 1.0 | Completely accidental, very rarely possible |

| 3.0 | Possible but infrequent |

| 6.0 | Fairly likely to occur |

| 10.0 | Almost certain or fully predictable in advance |

| E Value | Description |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | Extremely rare occurrence |

| 1.0 | Occurs several times per year |

| 2.0 | Exposure about once per month |

| 3.0 | Exposure once per week or occasional exposure |

| 6.0 | Daily exposure during working hours t |

| 10.0 | Continuous exposure to potential hazards |

| C Value | Description |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | Minor injury |

| 3.0 | Slight injury |

| 7.0 | Major injury |

| 15.0 | Severe injury, one fatality |

| 40.0 | Moderate disaster, multiple fatalities |

| 100.0 | Catastrophic disaster, many fatalities |

| Result Description | D Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Slight danger, acceptable | <20 | Negligible risk |

| General danger, attention required | 20–69 | Acceptable risk |

| Moderate risk, improvement needed | 70–160 | Moderate risk |

| High danger, immediate rectification required | 160–320 | Major risk |

| Extremely high danger, construction must be stopped | >320 | Critical risk |

| No. | Inspection Item | Allowable Deviation or Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Single-side width of foundation trench slope | −20 to +250 cm (negative values indicate inward deviation) |

| 2 | Foundation trench axis alignment | Average allowable deviation: −50 to +50 cm |

| 3 | Foundation trench bottom elevation | Normal allowable deviation for finished excavation bottom elevation: −50 to 0 cm |

| 4 | Foundation trench slope gradient | Shall not be steeper than the design slope |

| No. | Inspection Item | Specified Value or Allowable Error |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elevation of rubble top surface or maximum allowable error of all measurement points after compaction | ±30 cm |

| 2 | Alignment of top edge lines on both sides of rubble layer relative to design position | ±50 cm |

| Corrosion Grade | Corrosion Loss in the First Year |

|---|---|

| C3 | 25–50 μm/y |

| C4 | 50–80 μm/y |

| C5 | 80–200 μm/y |

| CX | >200 μm/y |

| Risk Level | Undrained Shear Strength (Su) |

|---|---|

| High risk | Su < 12 kpa |

| Medium risk | Su: 12–25 kpa |

| Low risk | Su ≥ 25 kpa |

| Construction Stage and Activity | Current Velocity (m/s) | Wave Height (m) | Wind Speed (Beaufort Scale) | Visibility (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segment launching from dry dock | ≤0.3 | ≤0.8 | ≤6 | ≥1000 |

| Rail-guided floating transportation | ≤0.8 | ≤0.8 | ≤6 | ≥1000 |

| Submerging of semi-submersible barge or floating dock | ≤0.3 | ≤0.8 | ≤6 | ≥1000 |

| Longitudinal towing of segment within foundation trench | ≤0.5 | ≤0.8 | ≤6 | ≥1000 |

| Waiting period before segment immersion | ≤1.1 | ≤0.8 | ≤6 | ≥1000 |

| Segment immersion and connection | ≤0.5 | ≤0.6 | ≤6 | ≥1000 |

| Scale | Importance Level | Meaning of the Scale |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | Equally important | The two factors are of equal importance |

| 1.2 | Slightly more important | One factor is slightly more important than the other |

| 1.4 | Clearly more important | One factor is clearly more important than the other |

| 1.6 | Much more important | One factor is much more important than the other |

| 1.8 | Extremely important | One factor is extremely more important than the other |

| Risk Factor Indicator | Weight |

|---|---|

| Inadequate blasting safety precautions | 11.57% |

| Mechanical equipment malfunction or improper operation | 10.00% |

| Improper protection along waterfront slopes | 9.08% |

| Unsafe operations in enclosed compartments or confined spaces | 9.03% |

| Insufficient reinforcement of working platforms or formwork | 7.78% |

| Improper operation during overboard ship work | 6.61% |

| Improper use of temporary electrical power | 5.99% |

| Inaccurate positioning under deep-water conditions | 3.89% |

| Improper welding operations | 3.53% |

| Impact from floating or falling objects | 3.44% |

| Influence of extreme weather conditions | 3.17% |

| Inadequate leveling accuracy or depth control | 3.00% |

| Limitations on diving operations | 2.88% |

| Accelerated material aging due to environment corrosion | 2.65% |

| Improper ship or vehicle transportation operations | 2.60% |

| Foundation trench excavation failing to meet depth or precision requirements | 2.59% |

| Structural risks and waterproofing requirements under high-pressure conditions | 2.23% |

| Uncertainty of the geological–geotechnical model | 2.20% |

| Material contraction or decline in equipment performance caused by low temperature | 2.20% |

| Variation in seabed back-siltation intensity | 2.16% |

| Application of new technologies, materials, or structures | 1.81% |

| Improper placement of materials and equipment | 1.59% |

| Risk Factor Indicators | Classification | Basic Score | Weight Score | Evaluation Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score Range | Score | ||||

| Inadequate protection along waterfront slopes | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r11 | w11 | Q11 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Mechanical equipment malfunction or improper operation | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r12 | w12 | Q12 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Insufficient reinforcement of working platforms or formwork | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r13 | w13 | Q13 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Improper use of temporary electrical power | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r14 | w14 | Q14 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Improper welding operations | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r15 | w15 | Q15 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Improper operation during overboard ship work | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r16 | w16 | Q16 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Inadequate blasting safety precautions | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r17 | w17 | Q17 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Improper placement of materials and equipment | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r18 | w18 | Q18 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Unsafe operations in enclosed compartments or confined spaces | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r19 | w19 | Q19 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Improper ship or vehicle transportation operations | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r110 | w110 | Q110 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Risk Factor Indicators | Classification | Basic Score | Weight Score | Evaluation Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score Range | Score | ||||

| Inaccurate positioning under deep-water conditions | Error ≤ 1 cm | 0–25 | r21 | w21 | Q21 |

| Error: 1–2 cm | 25–50 | ||||

| Error: 2–5 cm | 50–75 | ||||

| Error > 5 cm | 75–100 | ||||

| Foundation trench excavation failing to meet depth or precision requirements | Compliance with standard requirements | 0 | r22 | w22 | Q22 |

| Non-compliance with standard requirements | 100 | ||||

| Inadequate leveling accuracy or depth control | Compliance with standard requirements | 0 | r23 | w23 | Q23 |

| Non-compliance with standard requirements | 100 | ||||

| Structural risks and waterproofing requirements under high-pressure conditions | Water pressure less than 0.8 Mpa | 0–25 | r24 | w24 | Q24 |

| Water pressure: 0.8–0.9 Mpa | 25–50 | ||||

| Water pressure: 0.9–1.0 Mpa | 50–75 | ||||

| Water pressure greater than or equal to 1.0 Mpa | 75–100 | ||||

| Material contraction or decline in equipment performance caused by low temperatures | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r25 | w25 | Q25 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Accelerated material aging due to seawater corrosion | Corrosivity category C3 | 0–25 | r26 | w26 | Q26 |

| Corrosivity category C4 | 25–50 | ||||

| Corrosivity category C5 | 50–75 | ||||

| Corrosivity category CX | 75–100 | ||||

| Application of new technologies, materials, or structures | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r27 | w27 | Q27 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Risk Factor Indicators | Classification | Basic Score | Weight Score | Evaluation Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score Range | Score | ||||

| Limitations on diving operations | Water depth ≤ 40 m | 0–20 | r31 | w31 | Q31 |

| Water depth: 40–60 m | 20–60 | ||||

| Water depth > 60 m | 60–100 | ||||

| Uncertainty of the geological–geotechnical model | Su ≥ 25 kpa | 0–20 | r32 | w32 | Q32 |

| Su: 12–25 kpa | 20–60 | ||||

| Su < 12 kpa | 60–100 | ||||

| Variation in seabed back-siltation intensity | Compliance with back-siltation requirements | 0 | r33 | w33 | Q33 |

| Non-compliance with back-siltation requirements | 100 | ||||

| Impact from floating or falling objects | Negligible risk | 0–20 | r34 | w34 | Q34 |

| Acceptable risk | 20–40 | ||||

| Moderate risk | 40–60 | ||||

| Major risk | 60–80 | ||||

| Severe risk | 80–100 | ||||

| Influence of extreme weather conditions | Compliance with standard requirements | 0 | r35 | w35 | Q35 |

| Non-compliance with standard requirements | 100 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, H.; Qiu, Z.; Xu, S.; Mao, L.; Cui, Z. Research on Risk Assessment and Prevention–Control Measures for Immersed Tunnel Construction in 100 m-Deep Water Environments. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010053

Xu H, Qiu Z, Xu S, Mao L, Cui Z. Research on Risk Assessment and Prevention–Control Measures for Immersed Tunnel Construction in 100 m-Deep Water Environments. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Haiyang, Zhengzhong Qiu, Sudong Xu, Liuyan Mao, and Zebang Cui. 2026. "Research on Risk Assessment and Prevention–Control Measures for Immersed Tunnel Construction in 100 m-Deep Water Environments" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010053

APA StyleXu, H., Qiu, Z., Xu, S., Mao, L., & Cui, Z. (2026). Research on Risk Assessment and Prevention–Control Measures for Immersed Tunnel Construction in 100 m-Deep Water Environments. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010053