A U-Net-Based Prediction of Surface Pressure and Wall Shear Stress Distributions for Suboff Hull Form Family

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Target Submarine Types

2.1. Reference Hull and Numerical Setup

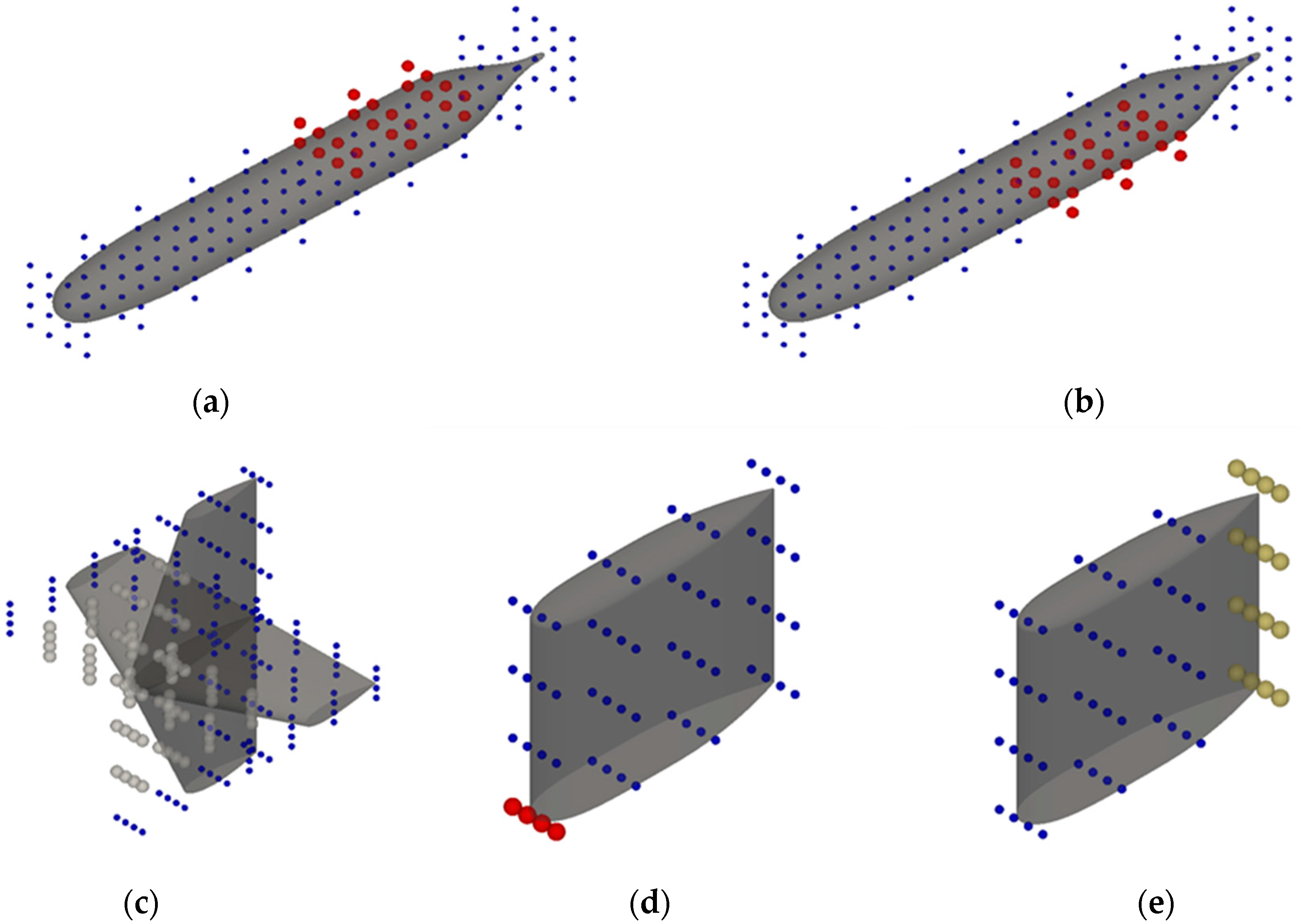

2.2. FFD-Based Variants of the Target Geometry

2.2.1. Master Point

2.2.2. Method for Determining Variation Magnitudes

2.3. Governing Equations and Mesh System

2.4. Preprocessing of Hull Form Data for Training

3. Machine Learning

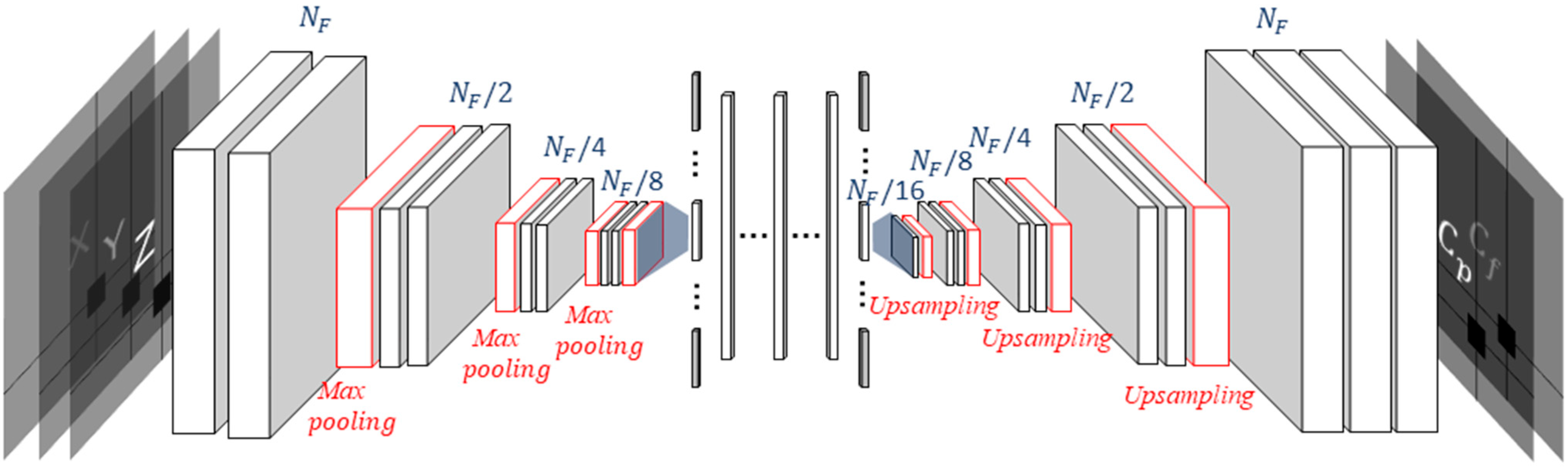

3.1. U-Net

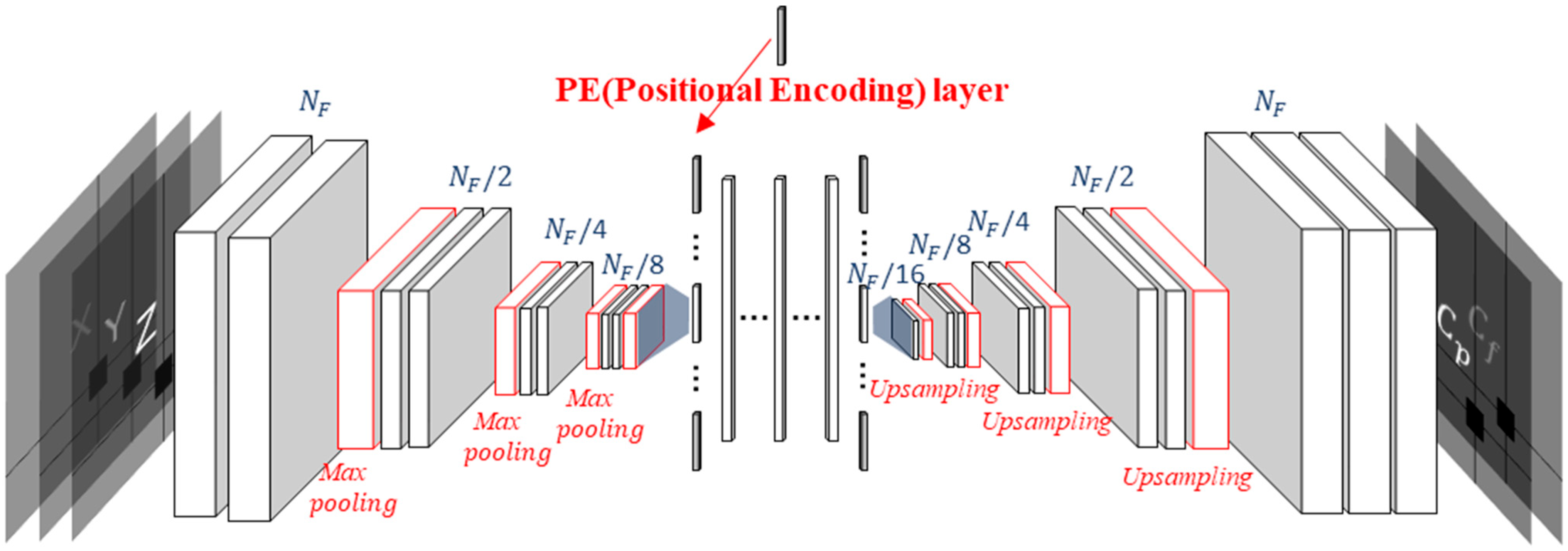

3.2. Positional Encoding (PE)

3.2.1. Features and Structure of Positional Encoding

3.2.2. Formal Definition of Positional Encoding

3.3. Relocation of the Seam

3.3.1. Motivation

3.3.2. Relocation Method

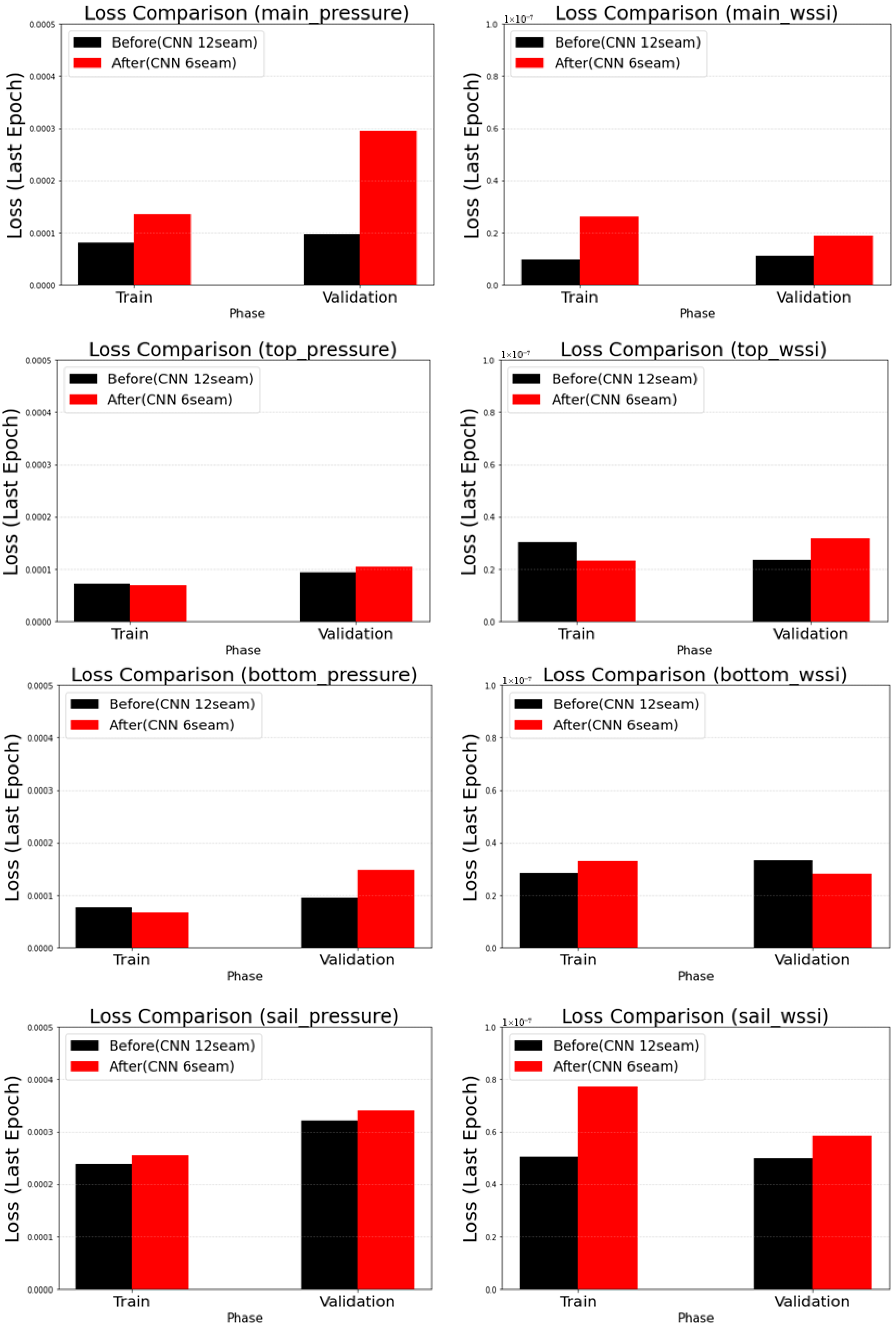

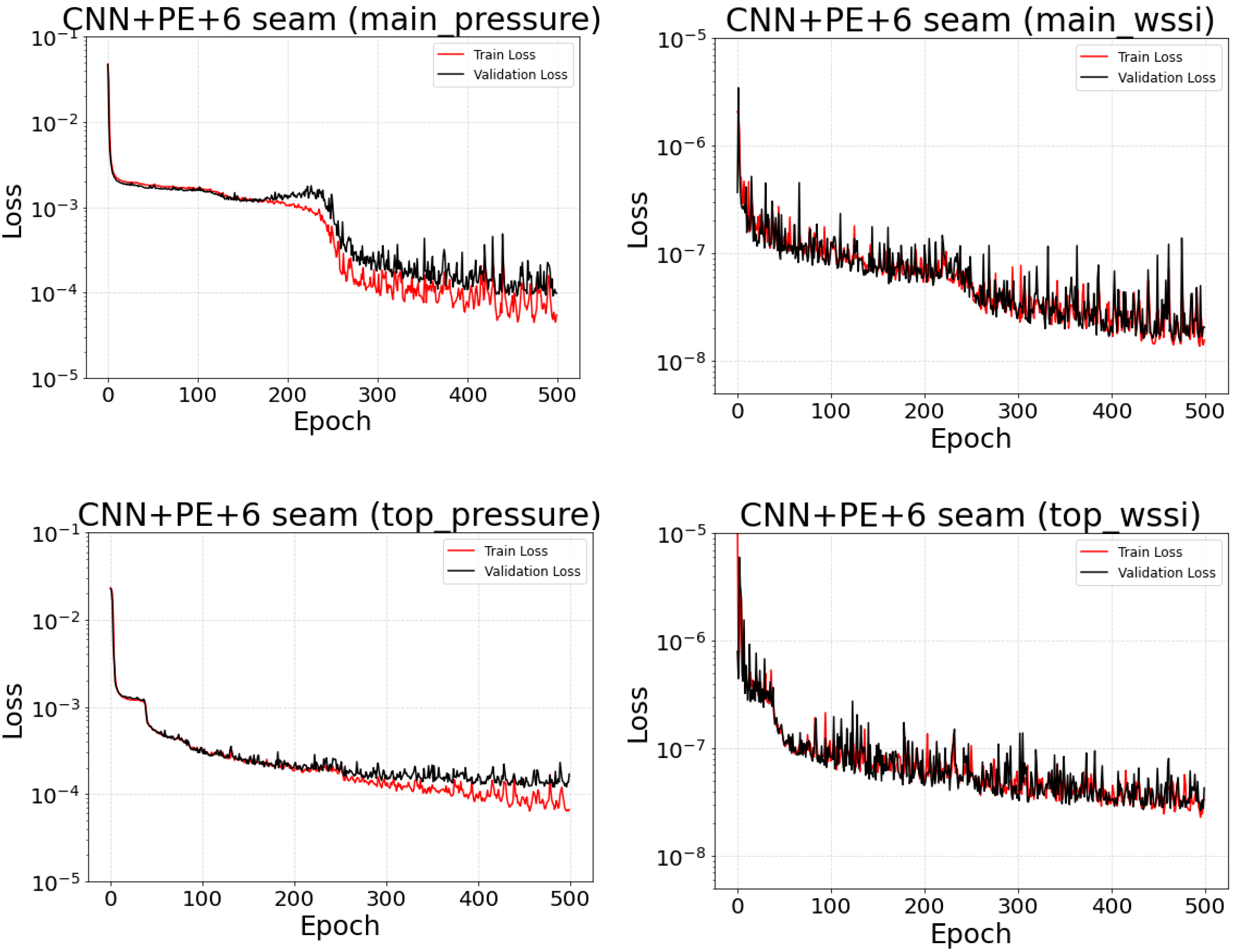

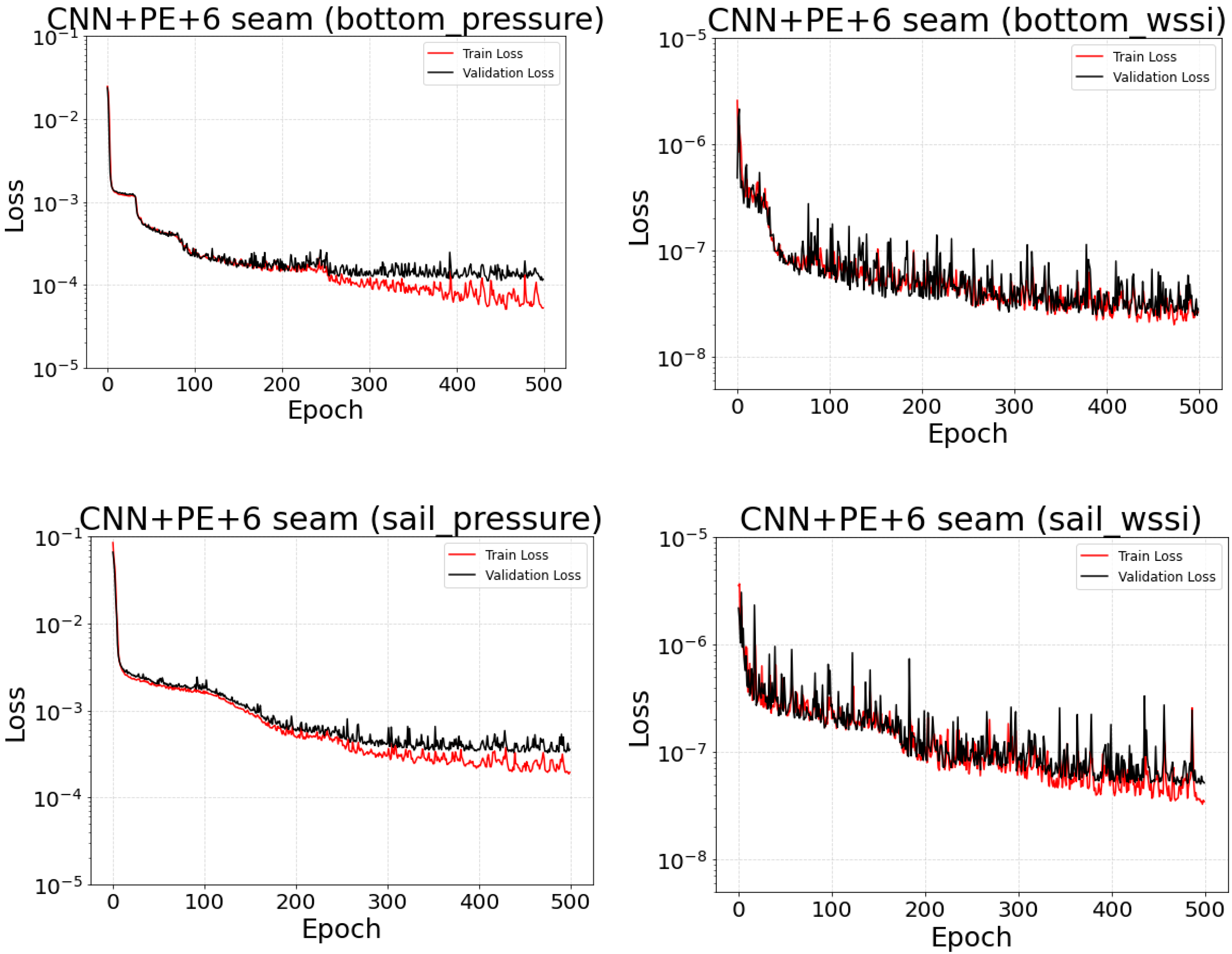

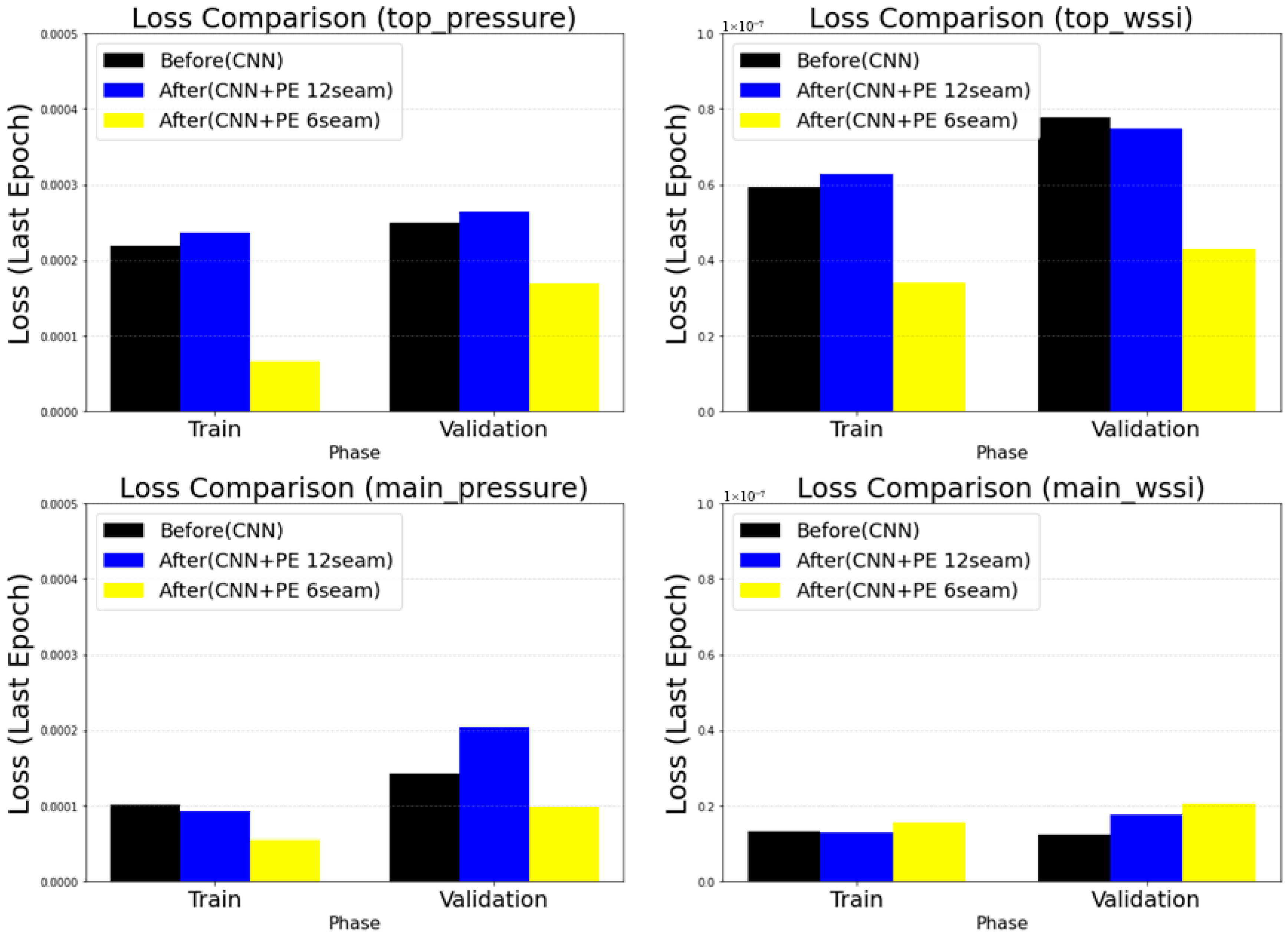

3.3.3. Quantitative Evaluation of the Seam

3.4. Machine Learning Training

3.4.1. Inputs and Normalization

3.4.2. Fully Connected Network and Part-Wise Decoders

3.4.3. Outputs and Loss

3.5. Experimental Design

3.5.1. Data Composition

3.5.2. Baselines for Comparison

3.5.3. Training Setup and Model Selection

3.5.4. Evaluation of Prediction Metrics

3.5.5. Visualization and Diagnostic Analysis

3.5.6. Spatial Error Map

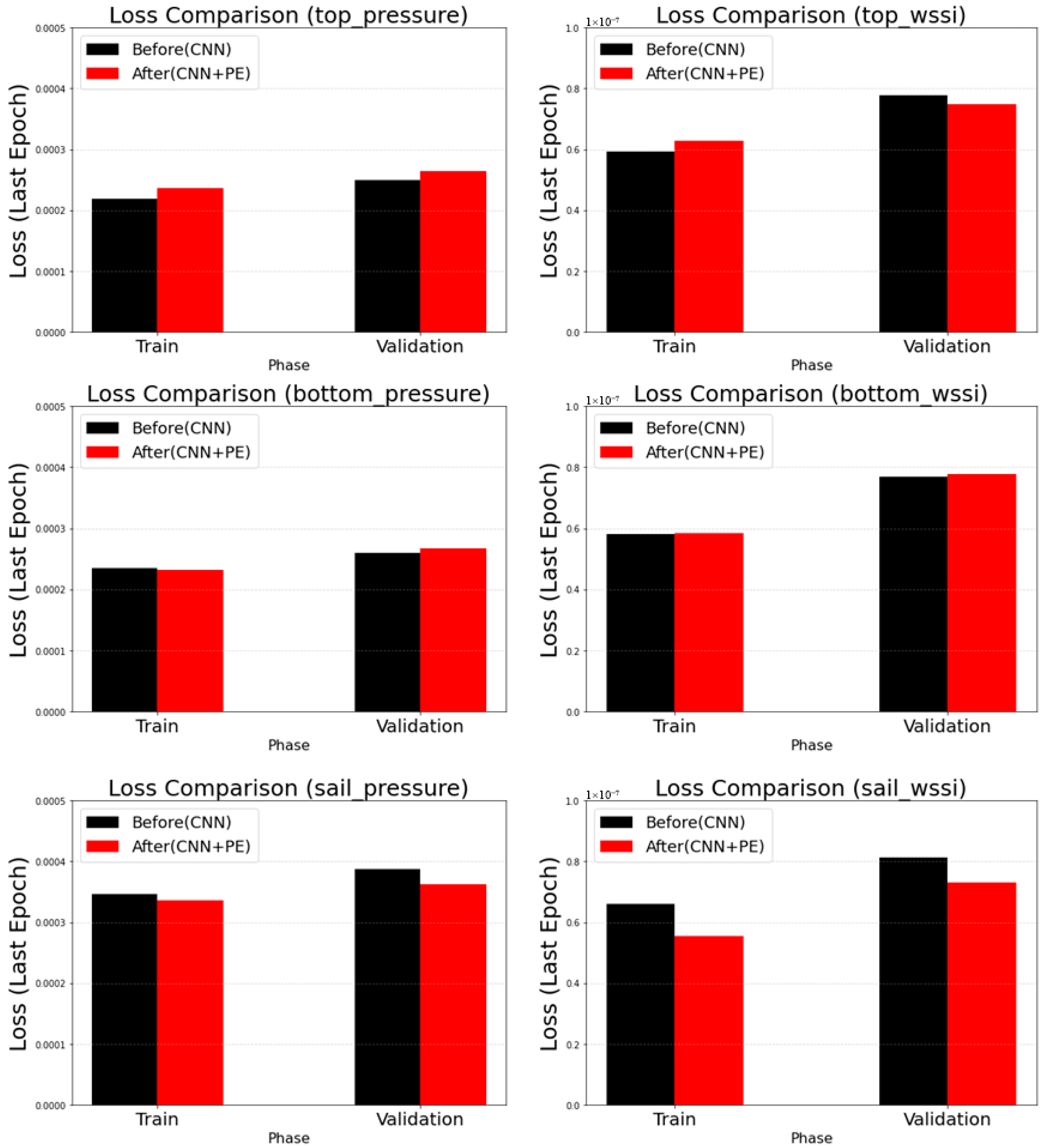

3.5.7. Analysis of the Influence of Positional Encoding

4. Summary and Key Findings

4.1. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Models

4.2. Limitations of Prediction

4.3. Correlation Between and Errors and Their Impact on Total Resistance

5. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saghi, H.; Parunov, J.; Mikulić, A. Resistance coefficient estimation for a submarine’s bare hull moving in forward and transverse directions. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear PDEs. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Machine learning in sustainable ship design and operation: A review. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 266, 112907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Han, F.; Peng, X.; Gao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. Research on a Fast Resistance Performance Prediction Method for SUBOFF Model Based on Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs). In Proceedings of the OMAE 2024, Singapore, 9–14 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, X.; Guo, W.; Wu, T. Flow reconstruction over a SUBOFF model based on LBM-generated data and physics-informed neural networks. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 308, 118250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, J. A Spatio-Temporal Graph Neural Network for Predicting the Spatio-Temporal Evolution of the DARPA SUBOFF AFF-8 Flow Field. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Seo, J.; Lee, I. A U-net based reconstruction of high-fidelity simulation results for flow around a ship hull based on low-fidelity inviscid flow simulation. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 17, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Ding, J.; Bian, C.; Zhao, P. Deep graph learning for the fast prediction of the wake field of DARPA SUBOFF. Ocean Eng. 2024, 309, 118353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, N.C.; Huang, T.T.; Chang, M. Geometric Characteristics of DARPA SUBOFF Models (DTRC/SHD-1298-01); David Taylor Research Center, Ship Hydromechanics Department: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J.; Kim, D.; Lee, I. A study on ship hull form transformation using convolutional autoencoder. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2024, 11, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manceau, R.; Hanjalić, K. Elliptic blending model: A new near-wall Reynolds-stress turbulence closure. Phys. Fluids 2002, 14, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichinose, Y.; Taniguchi, T. A curved surface representation method for convolutional neural network of wake field prediction. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2022, 27, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukami, K.; Fukagata, K.; Taira, K. Super-resolution reconstruction of turbulent flows with machine learning. J. Fluid Mech. 2019, 870, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuerey, N.; Weißenow, K.; Prantl, L.; Hu, X. Deep learning methods for Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes simulations of airfoil flows. AIAA J. 2020, 58, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2017); Neural Information Processing Systems Foundation, Inc. (NeurIPS): San Diego, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Lu, Y.; Pan, S.; Murtadha, A.; Wen, B.; Liu, Y. RoFormer: Enhanced Transformer with Rotary Position Embedding. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.09864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Commun. ACM 2021, 65, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kovachki, N.; Azizzadenesheli, K.; Liu, B.; Bhattacharya, K.; Stuart, A.; Anandkumar, A. Fourier Neural Operator for Parametric Partial Differential Equations. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.08895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ship | Model | |

|---|---|---|

| LOA | 104.544 m | 4.356 m |

| Max diameter | 12.192 m | 0.508 m |

| L/D | 8.58 | |

| Scale | 24 | |

| Master Point | Purpose |

|---|---|

| M1 | Modify the forebody (bow) region |

| M2 | Modify the lower afterbody (lower stern) region |

| M3 | Modify the upper afterbody (upper stern) region |

| M4 | Add filets to the rudders |

| M5 | Add a filet at the sail–forebody junction |

| M6, M7 | Apply an inclination (rake) modification to the sail’s afterbody |

| M8 | Vary the sail position |

| M9 | Adjust the forebody fullness (Nf) |

| Domain Size | −3.0 L < X < 3.0 L, −1.5 L < Y < 0, −1.5 L < Z < 1.5 L |

|---|---|

| Top | Symmetry plane |

| Bottom | Symmetry plane |

| Inlet | Velocity inlet |

| Outlet | Pressure outlet |

| Side | Symmetry plane |

| Model ID | Description |

|---|---|

| MO0 | Pure CNN predicting and |

| MO1 | Positional encoding (PE) concatenated to the feature maps after the encoder |

| MO2 | Same as MO1, but with the seam relocated to 6 o’clock during preprocessing |

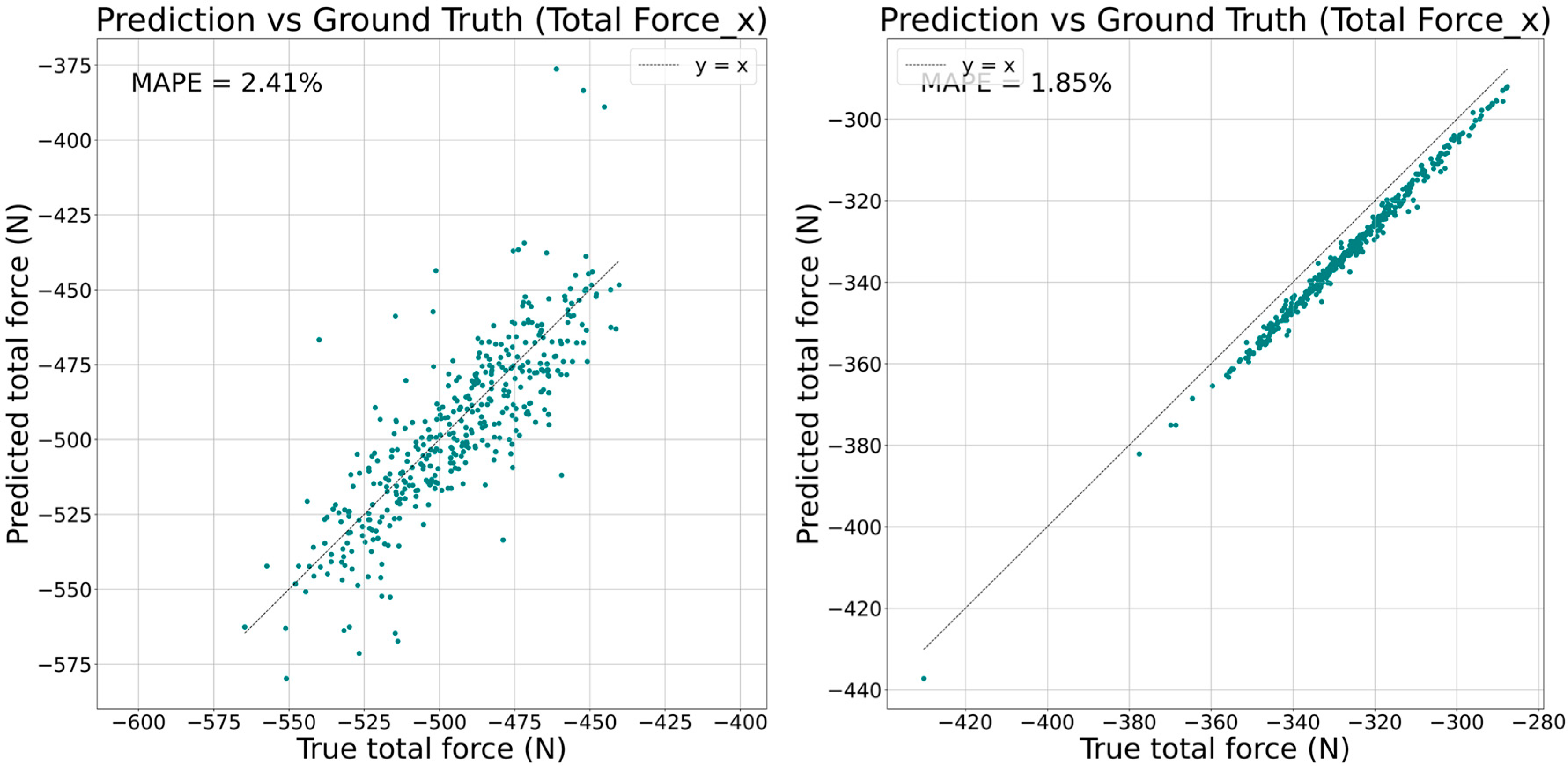

| CNN | CNN + PE (Seam at 12 O’clock) | CNN + PE (Seam at 6 O’clock) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAPE (%) | 2.41 | 3.61 | 1.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Seok, Y.; Seo, J.; Lee, I. A U-Net-Based Prediction of Surface Pressure and Wall Shear Stress Distributions for Suboff Hull Form Family. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010003

Seok Y, Seo J, Lee I. A U-Net-Based Prediction of Surface Pressure and Wall Shear Stress Distributions for Suboff Hull Form Family. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeok, Yongmin, Jeongbeom Seo, and Inwon Lee. 2026. "A U-Net-Based Prediction of Surface Pressure and Wall Shear Stress Distributions for Suboff Hull Form Family" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010003

APA StyleSeok, Y., Seo, J., & Lee, I. (2026). A U-Net-Based Prediction of Surface Pressure and Wall Shear Stress Distributions for Suboff Hull Form Family. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010003