2.1. Ship Maneuvering Prediction

The development of transport machines over the centuries has been guided by two immutable goals: the necessity of motion through a fluid medium (air or water) and the requirement to transfer control of the route to a human operator. Even the domestication of animals as primitive transport was driven by the desire to manage direction, as the fundamental purpose of transport is the guided transit of people or goods to a specific location. This inherent quality, which defines how easily a transport machine can be directed, is known as maneuverability, and this requirement is pursued in the design of a simple boat or an autonomous vessel. According to the French vocabulary, the word maneuverability of a ship covers all possible steady motions it may assume [

4]. It is important to note that these words have two different spellings: maneuverability/maneuver or manoeuvrability/manoeuvre. The British and Canadian English prefer the latter, while the American English prefers the former. According to Google N-gram Viewer, a tool comprising over five hundred billion words from various books and monographs found in the Google Books database, the term maneuverability was found to be the most frequently used spelling in 2019, with a usage rate of

higher than the British version. Thus, maneuverability/maneuver will be adopted in this text. In the Cambridge English Dictionary, this term is defined as the quality of being easy to move and direct. In the naval context, ship maneuverability studies deal with the motion of a rigid body on the surface of a real fluid, considering the effect of the body’s control surfaces. The invention of the rudder during the Middle Ages was pivotal, moving beyond oars to provide centralized control over steering. This control surface introduced two primary roles: altering the heading as desired and correcting deviations caused by flow disturbances around the hull. Besides its relevance, formal theoretical study of ship control began with Euler’s discoveries in the eighteenth century, as noted by [

5]. However, it were [

6] who first successfully unified the practical and theoretical aspects of ship dynamics relating to turning and course-keeping. Their work is considered a milestone in the ship performance field [

7], establishing the foundation for evaluating steering, which they defined as the ship’s response when the rudder is maneuvered to achieve a specified position [

6].

Recognizing the growing importance of the subject, the International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC) established a dedicated Maneuvering Committee in 1960. Back then, most maneuvering characteristics were assessed through free-running trials conducted at model scale in dedicated facilities; however, these trials are susceptible to scale effects. This susceptibility stems from the disproportionately dominant viscosity contribution at model-scale Reynolds numbers, which leads to an overestimation of propeller loading and misleading rudder forces, thereby compromising stability analyses. To address this scaling challenge, novel approaches emerged in the mid-1960s. The captive model test methodology, as highlighted by [

8], provided a better scaling approach by breaking the problem into groups of hydrodynamic coefficients. Such an approach enabled independent extrapolation of each coefficient to full scale, thereby improving understanding of scale effects when combined with a mathematical model. This approach also leveraged theories such as the low-aspect-ratio wing theory, suggesting that the scale effect on the lateral force at small incidence angles would be minor [

9].

During the ITTC’66, ref. [

10] introduced two parameters to assess a ship’s steering quality. The paper referred to these parameters as the ratio of a steady turning angular rate (K) and a time parameter (T). The purpose of these indices was to provide a means of measuring a ship’s response to rudder actuation. The authors suggested that these steering quality indices could be derived from experimental free-running tests of prescribed trajectories, such as turning and zigzag tests. Concurrently, Winnifred R. Jacobs proposed an analytical method for ship stability analysis [

11]. Her work established a critical stability relation that a stable ship must obey:

Jacobs introduced the idea of stability derivatives based on potential theory and low-aspect-ratio wing theory, thereby incorporating viscosity effects. A subsequent journal publication [

12] provided a comprehensive comparison between her analytical method and experimental data, successfully confirming the effectiveness of the proposed method.

The increasing size of vessels, particularly tankers, and consequent accidents in restricted areas, as highlighted by [

13] at the 11th ITTC, underscored the urgent need to understand transient and low-speed conditions. Motora detailed the critical loss of rudder efficiency and controllability during berthing maneuvers when the propeller is stopped or reversed, noting that maneuverability was often neglected in ship design despite its relevance to safety [

14]. This safety imperative drove the development of comprehensive mathematical models. The foundational work by Abkowitz [

9] utilized a Taylor series expansion for the integrated hull–propeller–rudder system. While initially focused on small angles at cruising speeds, ref. [

15,

16] adapted the model for low-speed, high-angle scenarios by introducing quadratic (nonlinear) approximations to account for viscous effects, which in turn required facilities like PMM to measure these new nonlinear terms [

17]. Usually, these tests are performed in a towing tank, ref. [

18] proposed an alternative approach, using a Circulating Water Channel (CWC) to obtain the maneuvering hydrodynamic derivatives. While the method proved reliable, with a statistical convergence error of less than

, this test is inherently limited by the facility dimension, consequently requiring a small-scale model. The authors extensively discussed the experimental uncertainty and its assessment on both approaches. Concurrently, the Japanese MMG (Manoeuvring Modeling Group) proposed a more flexible 3-DOF approach in the 1970s, separating the force contributions [

19], which was later extended by [

20] to include roll. Despite differing derivations, both models rely fundamentally on hydrodynamic derivatives.

Therefore, obtaining the hydrodynamic derivatives is a key factor, a task recognized by the International Towing Tank Conference (ITTC) as challenging [

21]. Historically, the hydrodynamic coefficients required by these models were obtained through experimental tests. Ref. [

22] noted the growth in experimental facilities, particularly in post-war Japan. Ref. [

14] pointed out that as late as the 1990s, most simulator coefficients were still sourced from expensive and complex fully appended captive model tests (e.g., PMM, SDT), which demand large facilities to mitigate blockage issues. Several alternative methods emerged to overcome these challenges. In the late 1970s, system identification [

23] was developed to estimate all coefficients simultaneously from free-running maneuver trajectories, thereby capturing interaction effects. From the 2000s onward, CFD has been widely used to compute the hydrodynamic forces and moments acting on ships, including the complex case of static drift tests at high angles, where flow separation may occur. Toxopeus [

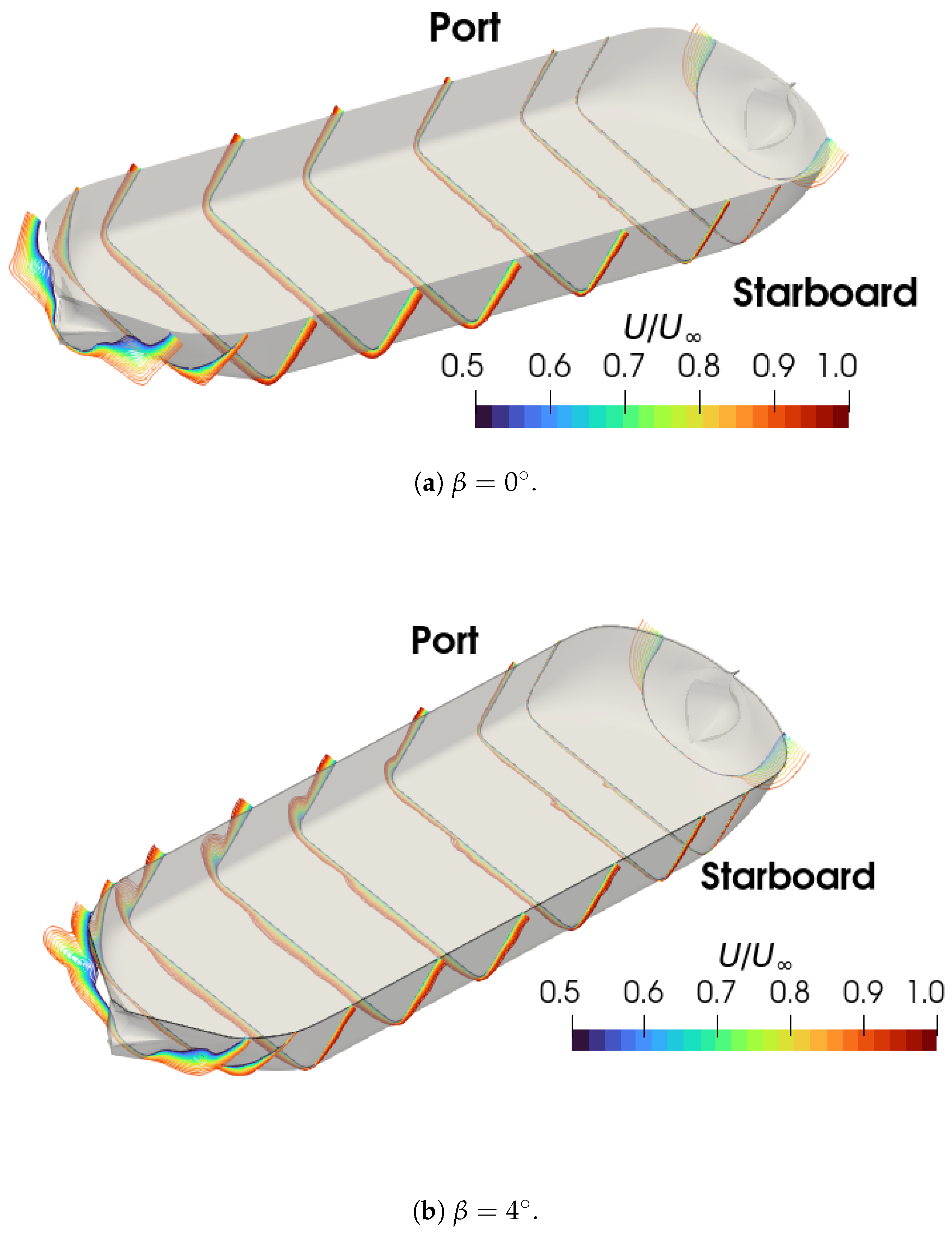

24] conducted an extensive study on verification and validation of the viscous flow computations at different drift angles and hull shapes. The author found promising results in both lateral force, yaw moment, and maneuvering prediction employing hydrodynamic coefficients obtained numerically, which brought some exciting aspects of using CFD to deal with maneuvering ship problems, focusing on the virtual captive model test.

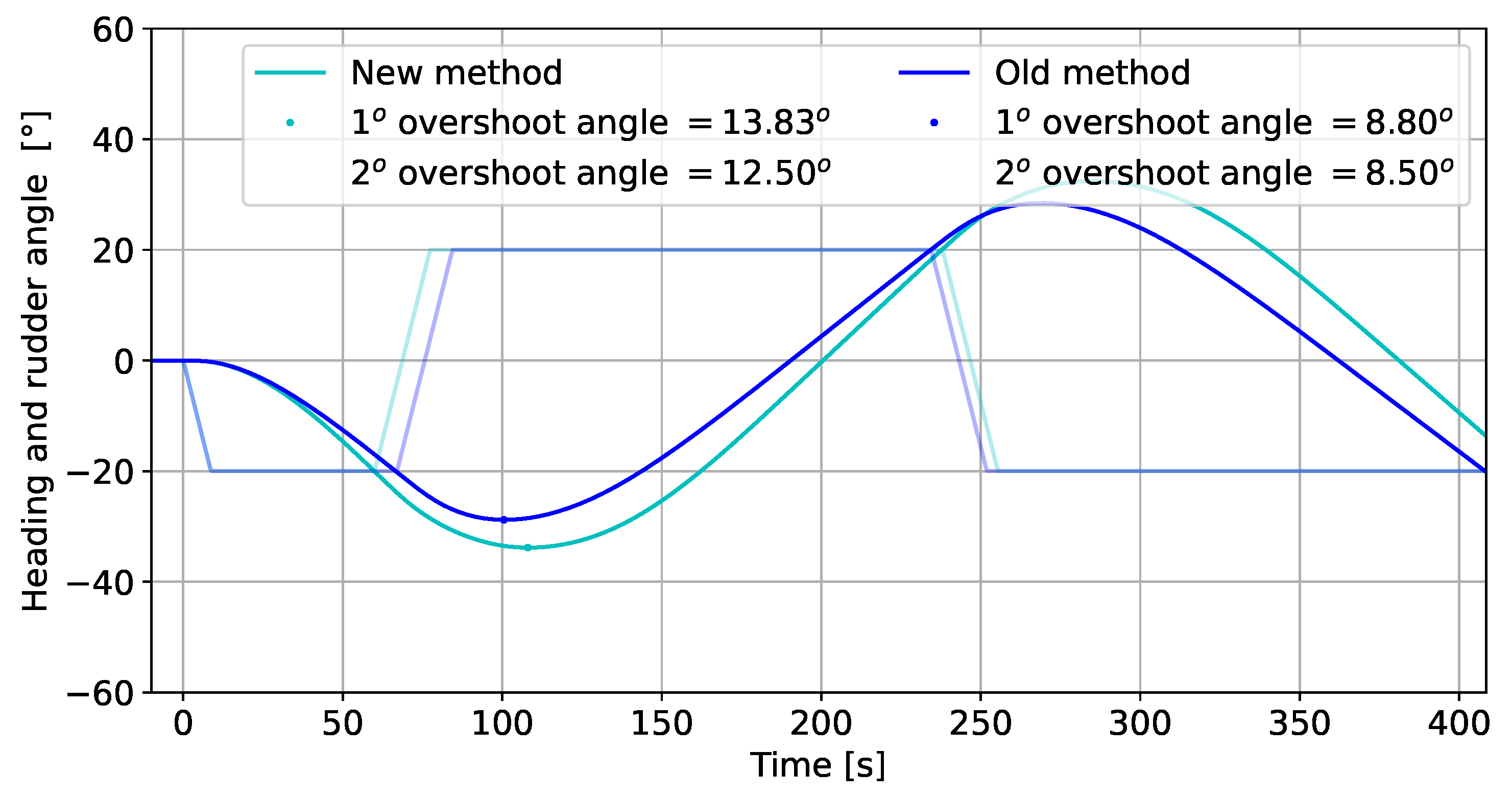

Considering future solutions on ship maneuvers subject and emphasizing that the automation of berthing can significantly enhance safety, it is highly relevant to explore maneuvering models that can serve as a reference foundation for these more complex automated systems. Ref. [

25] provide a state-of-the-art review and future perspectives on automatic berthing modeling, addressing the similarities and differences between the conventional MMG model and the automatic berthing maneuver model. The authors highlight the advantages of employing virtual captive model tests for both model types, which underscores the need for robust numerical solutions capable of performing virtual static drift tests across a wide range of drift angles. Since berthing models require hydrodynamic forces at high drift angles, it is essential to assess the validity of the numerical setup, particularly given the expected flow separation at higher drift angles.

As highlighted by Eda et al. [

26], the aerospace program accelerated the development of realistic computer-based simulators, and marine simulators began operating in the late 1960s. Among them, three were highlighted: Swedish State Shipbuilding Testing Facility (SSPA), Nederlandsche Organisatie voor Toegepast Natuurwetenschappelijk Onderzoek (in Dutch) (TNO), and Netherlands Ship Model Basin (NSMB). According to Norrbin [

16], the establishment of the SSPA in 1967 was a response to the shipbuilding industry’s requirement for real-time simulators, especially for large tankers. Manen and Hooft [

27] emphasized the role of these facilities in the evaluation of human influence in the maneuvers, and NSMB was built to meet this demand.

In the 1970s, ship-handling simulators were developed as engineering tools to help understand vessel navigation in restricted areas. In the 1980s, a worldwide boom in facilities for this purpose occurred, as seen in [

28]. These computer-based maneuvering methods require a mathematical model on a suitable time scale, meaning the equation of motion must be solved faster than the chosen time increment.

In real-time simulations, the temporal scale must be adjusted to reflect human response times. Consequently, empirical or semi-empirical methods are frequently employed. In this context, hydrodynamic coefficients play a crucial role. As mentioned at the opening of MARSIM’96 [

29], besides maneuvering mathematical models being vital, they are invisible in terms of their core and what is being modeled or not. Nevertheless, simulators are essential for supporting the training of maritime pilots and for anticipating navigation in new operating scenarios.

In the context of the maritime fleet’s decarbonization, where new devices are being rapidly proposed and implemented on both new and existing vessels (via retrofit), there is a growing concern regarding how these devices will affect ship maneuverability. Addressing this subject, publications already utilize mathematical models (MM) for maneuvering prediction in vessels equipped with such systems. An example is the work by [

30], who numerically investigated the aerodynamic forces and fed them into the simulation to execute standard maneuvers with a ship equipped with Flettner rotors using fast-time simulations. Similar research was developed by [

31], who applied the MMG method to predict the steady sailing condition and propulsive performance of a rotor ship.

2.2. Maneuvering Linear Derivatives

Nowadays, the most straightforward approach, however, utilizes empirical formulas derived from curve-fitting experimental data based on principal dimensions to determine the linear sway velocity derivative (

) and linear yaw velocity derivative (

). The low-aspect-ratio wing theory grounded the first approximation of these derivatives, and the equations were a function of the ship’s length and draft. The Jones formula is given by

wherein

CL denotes the lift coefficient and

is the aspect ratio. The application of the low-aspect-ratio wing theory to a ship is established by comparing the wing span with double the vessel’s draft. This assumption remains valid specifically for moderate forward speeds where wave-making effects can be appropriately neglected. Further, ref. Jacobs [

12] proposed utilizing potential theory and the low-aspect-ratio wing theory to incorporate viscosity effects into stability derivatives. Her work provided multiple equations that accounted for variations in stern layout, where the sway velocity derivative was explicitly made dependent on the drag coefficient. Following this analytical work, the 1970s saw the emergence of numerous regression formulas aimed at predicting linear derivatives, primarily relying on data gathered from Planar Motion Mechanism (PMM) and Rotating Arm tests. Smitt [

32] derived an empirical model using experimental data from 35 diverse vessel models, ranging from trawlers to supertankers. Although Smitt detailed the complex PMM techniques, his regression was compromised by its reliance on confidential experimental data collected for external clients, which restricted the sharing of crucial ship characteristics. A comparison of Smitt’s formulation with the low-aspect-ratio wing theory revealed that the empirical coefficients were consistently larger, suggesting that the purely theoretical approach underpredicted the derivative values relative to those found experimentally.

Norrbin [

16] pursued empirical relations specifically for the linearized hydrodynamics of a moving hull. Norrbin critically analyzed the limitations of the low-aspect-ratio wing analogy, emphasizing its failure to adequately incorporate the influence of the ship’s geometry, particularly the bow shape, on the distribution of lift forces along the forebody. While the wing analogy assumes that the transverse force is concentrated near the leading edge, the continuous bow geometry of a ship causes the lift force to be distributed. To address these geometric shortcomings, Norrbin developed a regression using stability derivative data from conventional ships, explicitly incorporating new geometric parameters, such as the block coefficient (

) and the beam, to better account for shape effects. The pursuit of more statistically robust empirical formulations continued through the 1980s. Inoue et al. [

19] expanded the database by conducting experiments across a wide range of ships at a very low Froude number (

) and incorporated loading conditions into the dataset. Shortly thereafter, ref. Clarke et al. [

33] published an update to the prediction formulas for linear derivatives, which was intended for use in the early stages of ship design. Clarke noted that his regression achieved a statistical improvement over Inoue’s prior work; however, he expressed persistent caution about the results due to substantial discrepancies between the predicted and measured derivatives across various vessels.

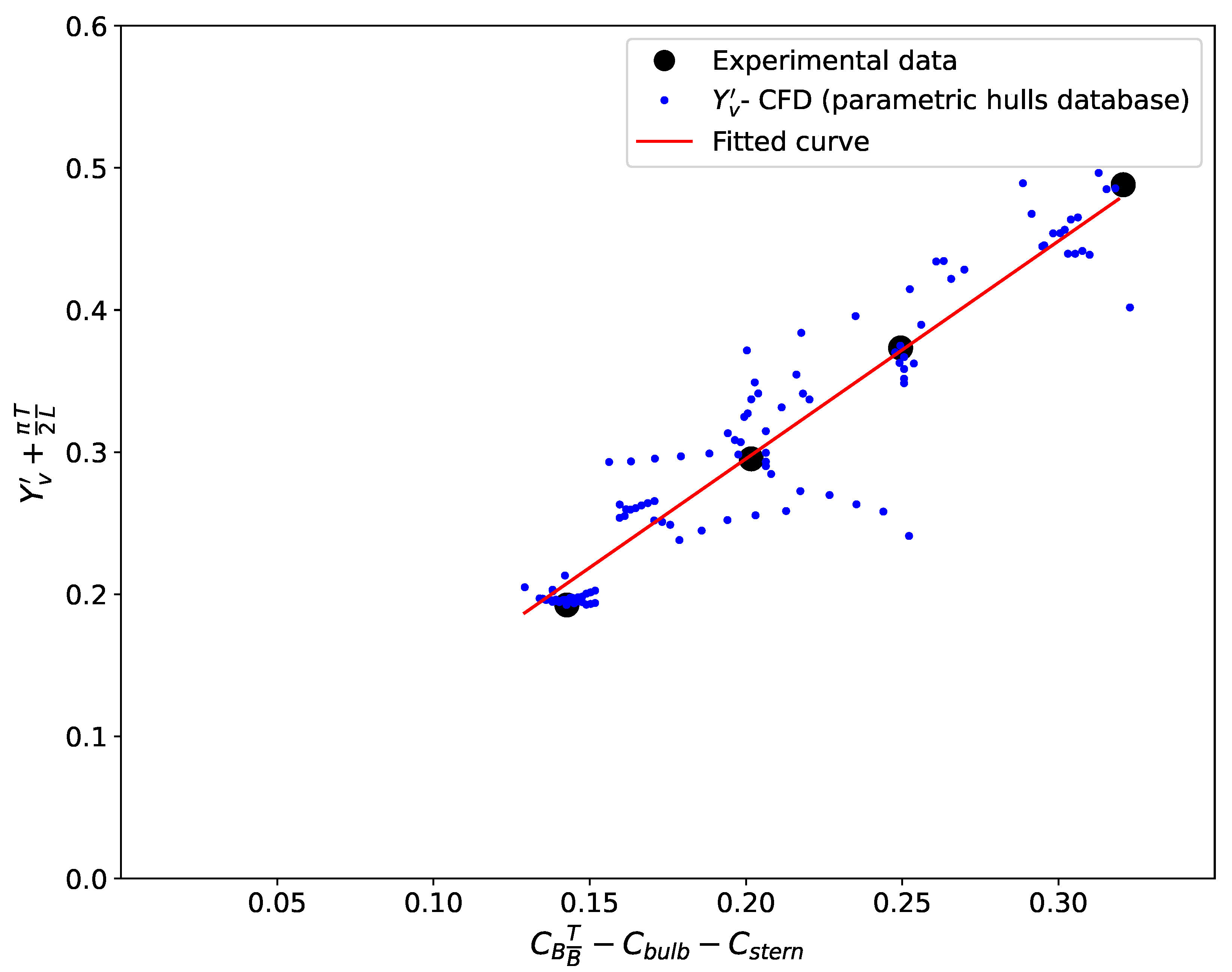

More recently, empirical efforts have shifted toward incorporating specific ship type or finer geometric details related to the stern design. Ref. [

34] considered only PMM data of a few tankers. Tae Lee et al. [

35] proposed regression equations based on the parameters related to the stern (

).

These empirical formulations are shown in

Table 1. While four out of six classical regression methods defined the sway velocity derivative (

) as a function of the theoretical term

and used the geometric parameter

as a primary predictor, later works, such as the regression proposed by Lee et al. [

35], introduced new parameters like

, which quantifies the stern layout. For the range of applicability of these formulations, refer to Chame [

36].

2.3. Evaluation of Empirical Methods Against Modern Hulls

A comparative study was conducted to evaluate the shortcomings of these empirical methods using a set of seven reference hulls. This group comprised five well-known benchmarks (Esso Osaka, S-175, KCS, KVLCC2, and DTC) alongside two operational vessels representing current designs: a Post-Panamax container ship (RVC) and a modern tanker (RVT). Four of these, which were used for validation, have validation data compiled from the existing literature.

Table 2 shows the main dimensions of these ships, called reference hulls. The last column indicates if there are validated benchmark data for the maneuvering resistance coefficient (

), linear sway velocity derivative (

), and linear yaw velocity derivative (

).

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the performance of traditional empirical formulations (as listed in

Table 1) against available experimental data for both conventional hull designs (such as Esso Osaka and S-175) and modern forms that incorporate bulbous bows and U/V-shaped sterns (such as KCS and KVLCC2). Although the three ships without validation data (DTC, RVC, and RVT) were included as representative examples of modern vessels, this was done to address the challenges posed by the limitations of empirical methods in accurately characterizing these modern designs.

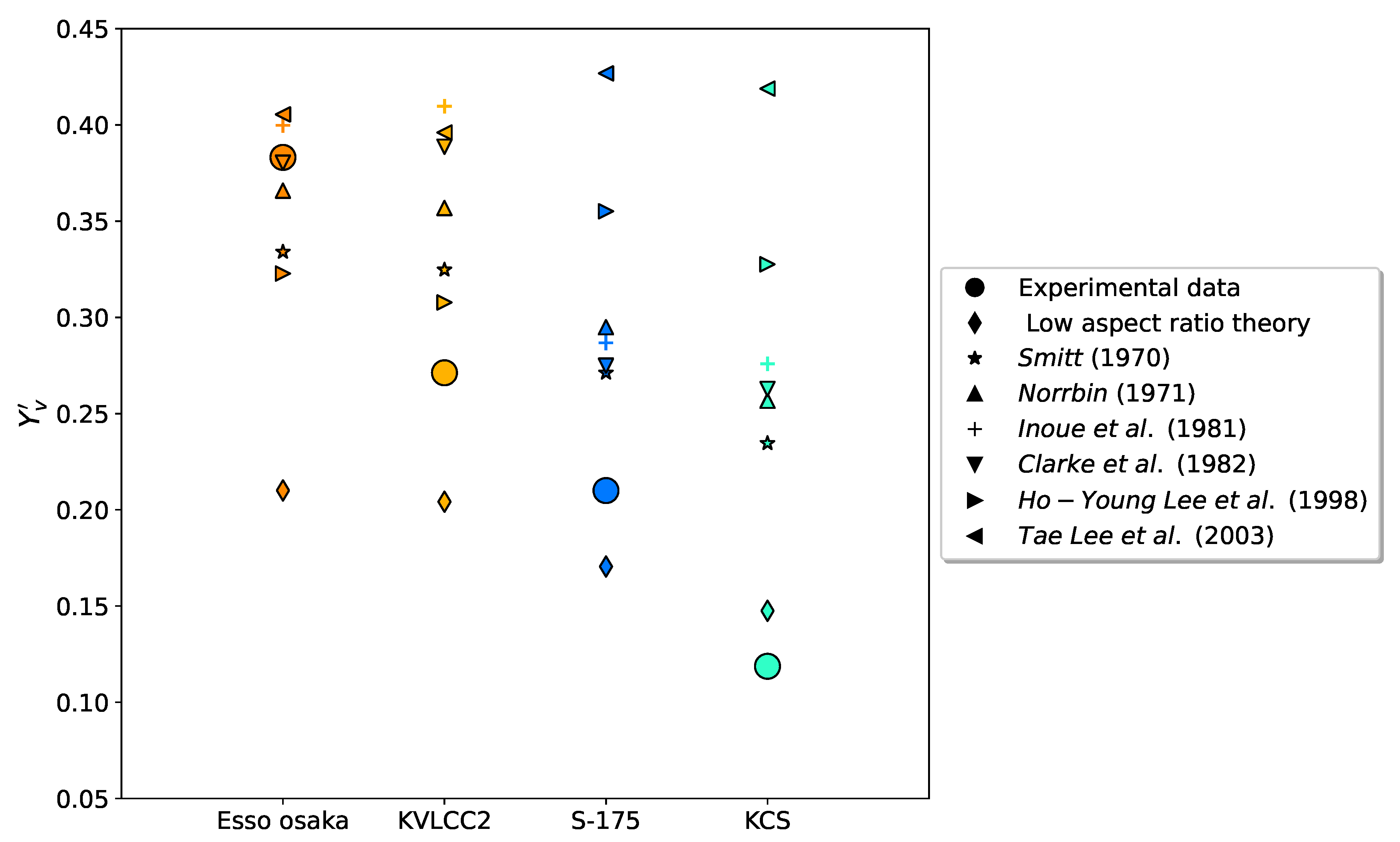

Figure 1 depicts the linear velocity derivatives derived from the formulations presented in

Table 1. Ho-Young Lee’s regression provided a better estimation of the lateral force for the modern box-shaped hull (KVLCC2), while Clarke’s method proved more effective for the Esso Osaka tanker. In contrast, the results for hulls with streamlined curves, such as the S-175 and KCS, were found to be overestimated. It is important to note that the analytical approach produced results that were closest to the experimental measurements. As for ship hulls characterized by a high block coefficient, the results were overestimated by as much as

. However, the model’s worst adherence was for the slim-shaped hull featuring a bulbous bow, where the predictions were more than

overestimated for the KCS. A comparable analysis was conducted for the linear yaw derivative. For a comprehensive examination of this subject, please refer to the detailed analysis presented by Chame [

36].

This discrepancy suggests that the databases underpinning these classical regressions are outdated and no longer representative of current hull geometries. An analysis of the range of applicability for each formulation confirmed this limitation. For instance, the method by Ho-Young Lee et al. [

34], which performed relatively well for the KVLCC2, possesses a very narrow applicability range that essentially covers only modern tankers, excluding slender forms. Conversely, formulations with wider databases, such as Inoue’s, cover all the evaluated reference vessels but produce unsatisfactory and inaccurate estimations.

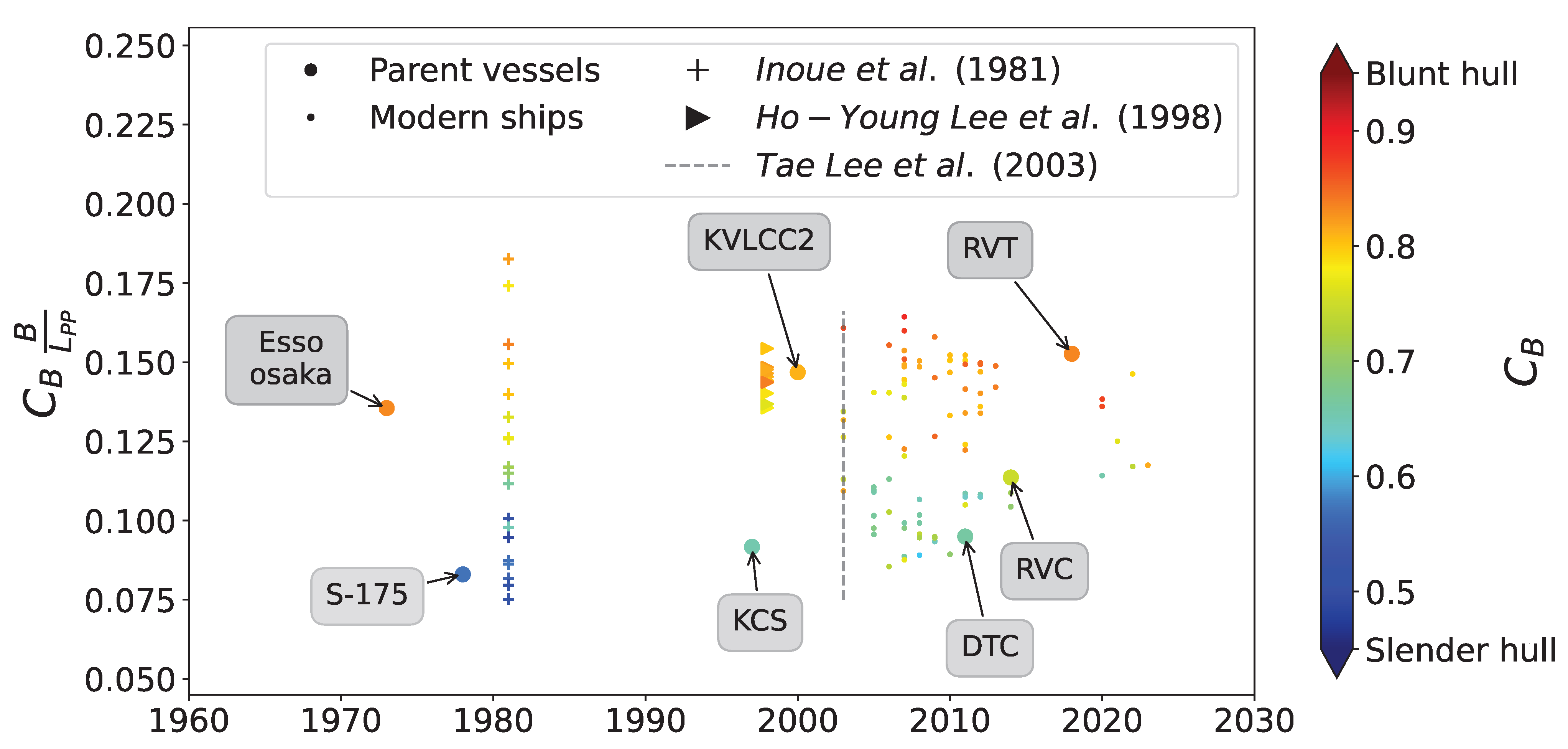

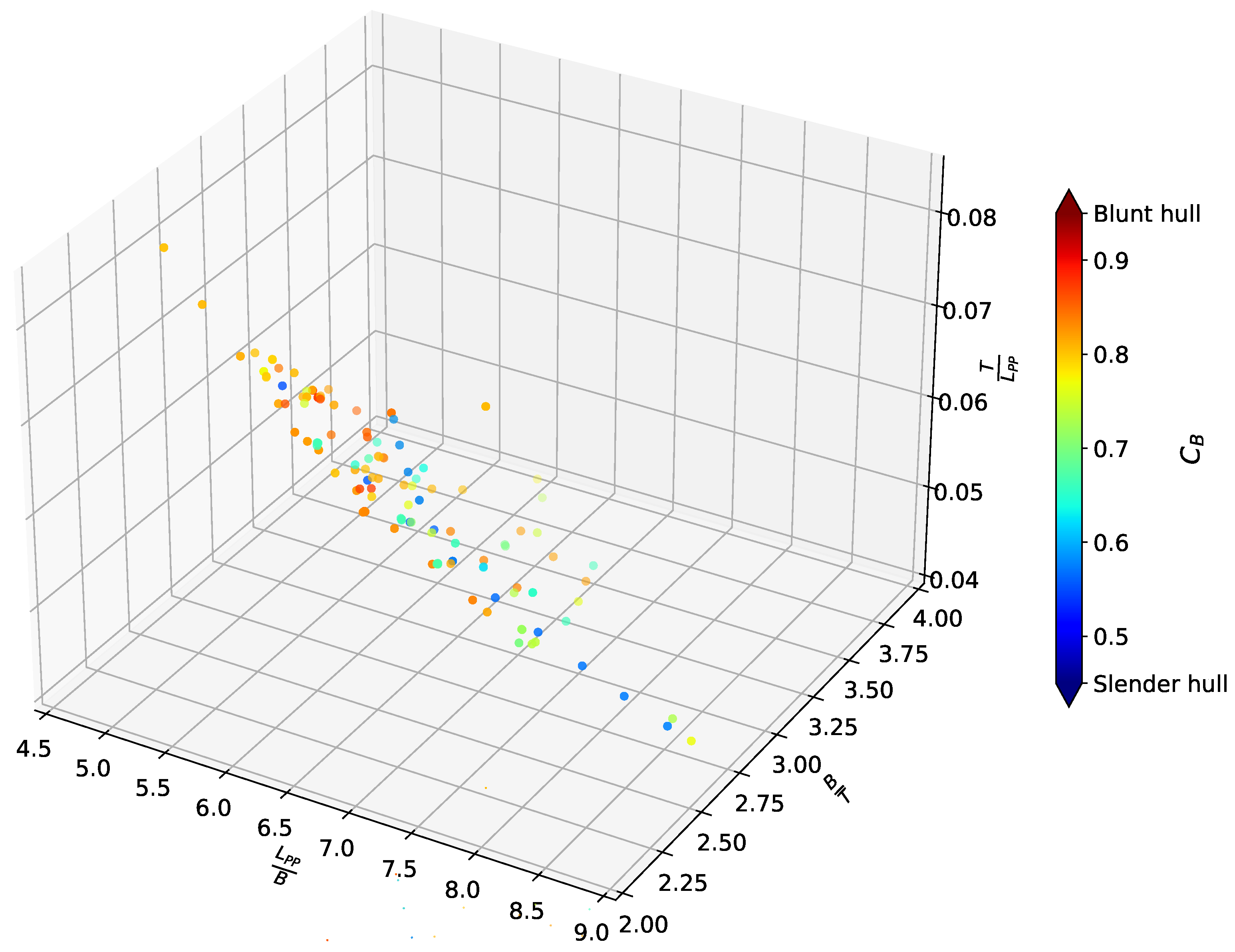

A secondary database comprising 90 contemporary vessels (cargo ships, tankers, and bulk carriers) launched from 2013 onward was compiled using principal dimensions sourced from industry publications like Significant Ships. This resource was used to identify geometric trends by comparing the scatter plot of the non-dimensional parameters between the modern fleet and the databases employed for regression methods.

Figure 2 brings an analysis of the

parameter, a common predictor among the empirical methods. It is easy to distinguish between slender (

) and blunt (

) hull groups, confirming that the reference vessels adequately represented the modern fleet. While the Lee’s database matched typical modern tankers, a comparison with the database from Inoue et al. [

19] shows an increase in the block coefficient in modern vessels; as a consequence, a lack of representation of slender hull forms is expected, consistent with the finding previously discussed.

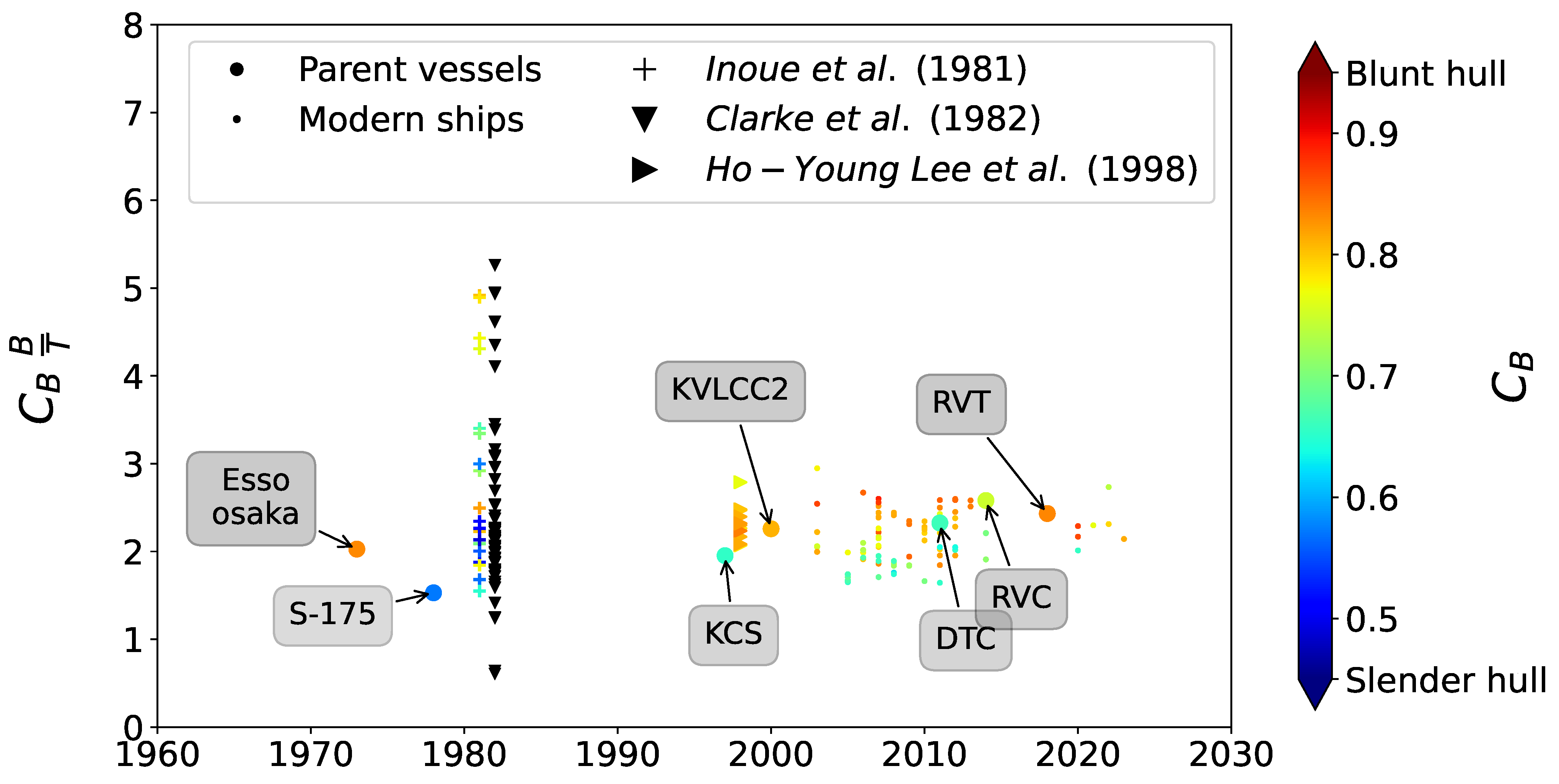

As shown in

Figure 3, the databases underlying the empirical formulations exhibited a significantly broader, more scattered distribution of geometric coefficients. At the same time, a narrower and more clustered range of

values was found for modern hulls. This divergence is highly relevant because, while many classical regression models showed reasonable agreement with modern data when using the coefficient

, the pronounced decrease in the

ratio is a distinguishing feature of modern designs. This inability of regressions to accurately encompass the shrinking range of

over time directly accounts for the poor performance observed in the KVLCC2 and KCS benchmark cases. Consequently, incorporating these specific geometric trends is recommended when developing empirical models to predict the linear sway derivative. Neglecting these trends may lead to inaccurate estimates of sway force and, consequently, unreliable predictions of maneuverability.

As noted by [

24], using empirical formulas outside the range of their regression databases can yield unreliable predictions of maneuverability. Consequently, further research is necessary to understand how the new design affects maneuvering characteristics, and predictions should be adjusted accordingly.

2.4. Advancements in CFD for Prediction of the Maneuvering Coefficients

Pioneering work by [

39] demonstrated the capability of the Finite Volume Method (FVM) to predict hydrodynamic forces in oblique flows, even for complex hull forms, reproducing standard captive model tests such as oblique towing, circular motion, and planar motion mechanism tests. Initial numerical predictions, however, showed a

underprediction compared to experimental data. Subsequent extensive verification and validation studies by researchers such as [

24,

40] confirmed the promising role of viscous flow computations in predicting maneuvering characteristics based on numerically derived hydrodynamic coefficients.

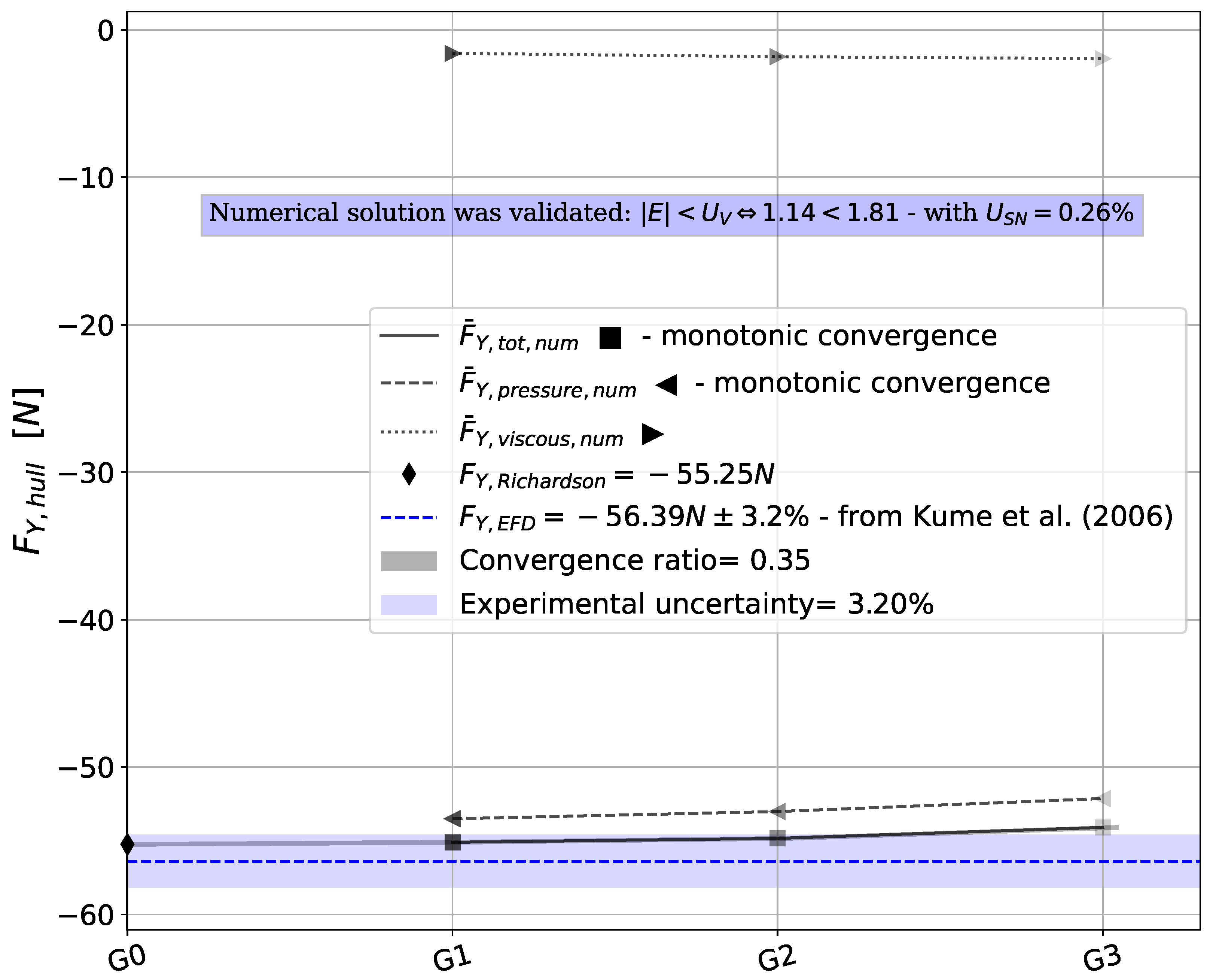

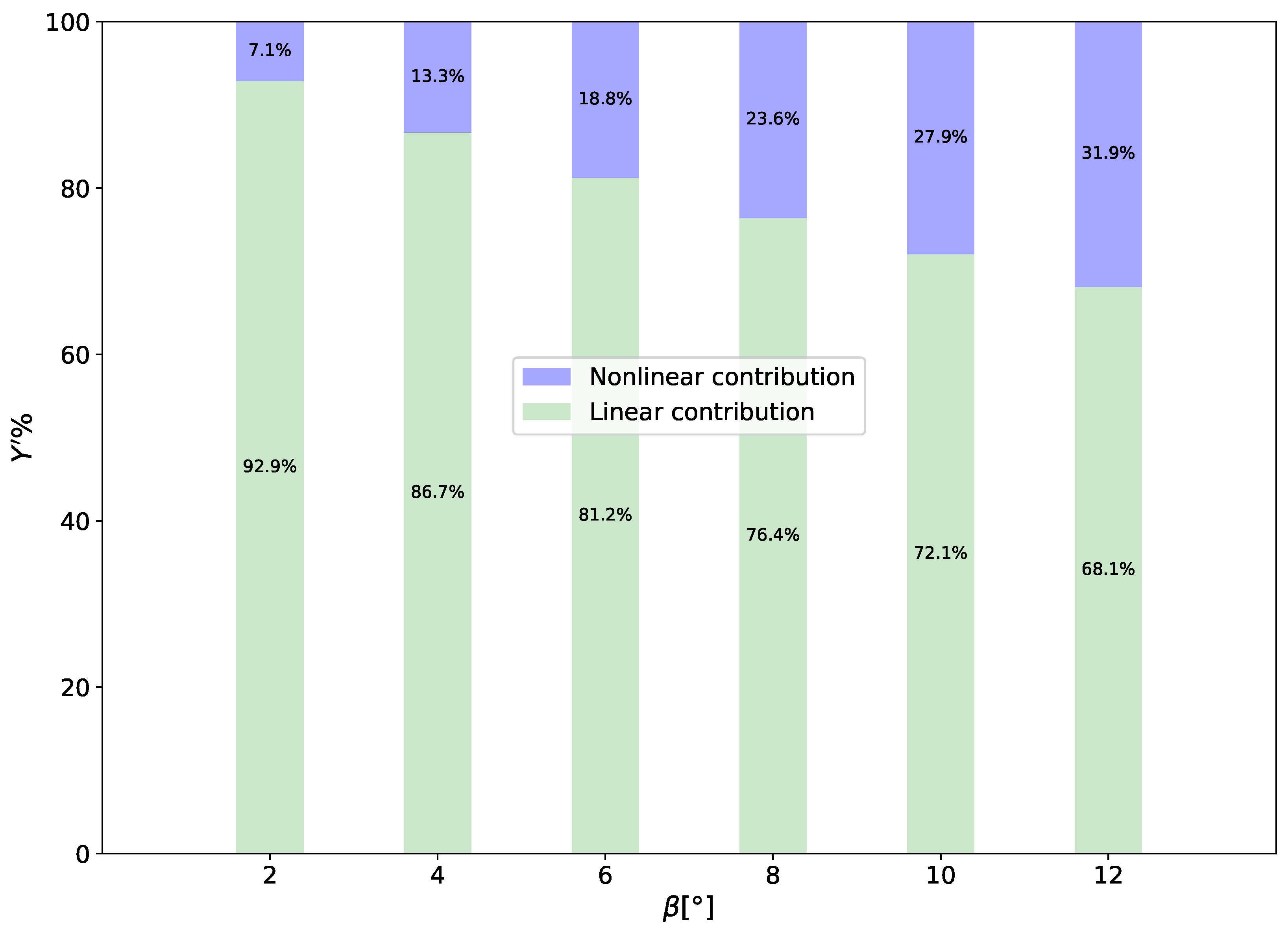

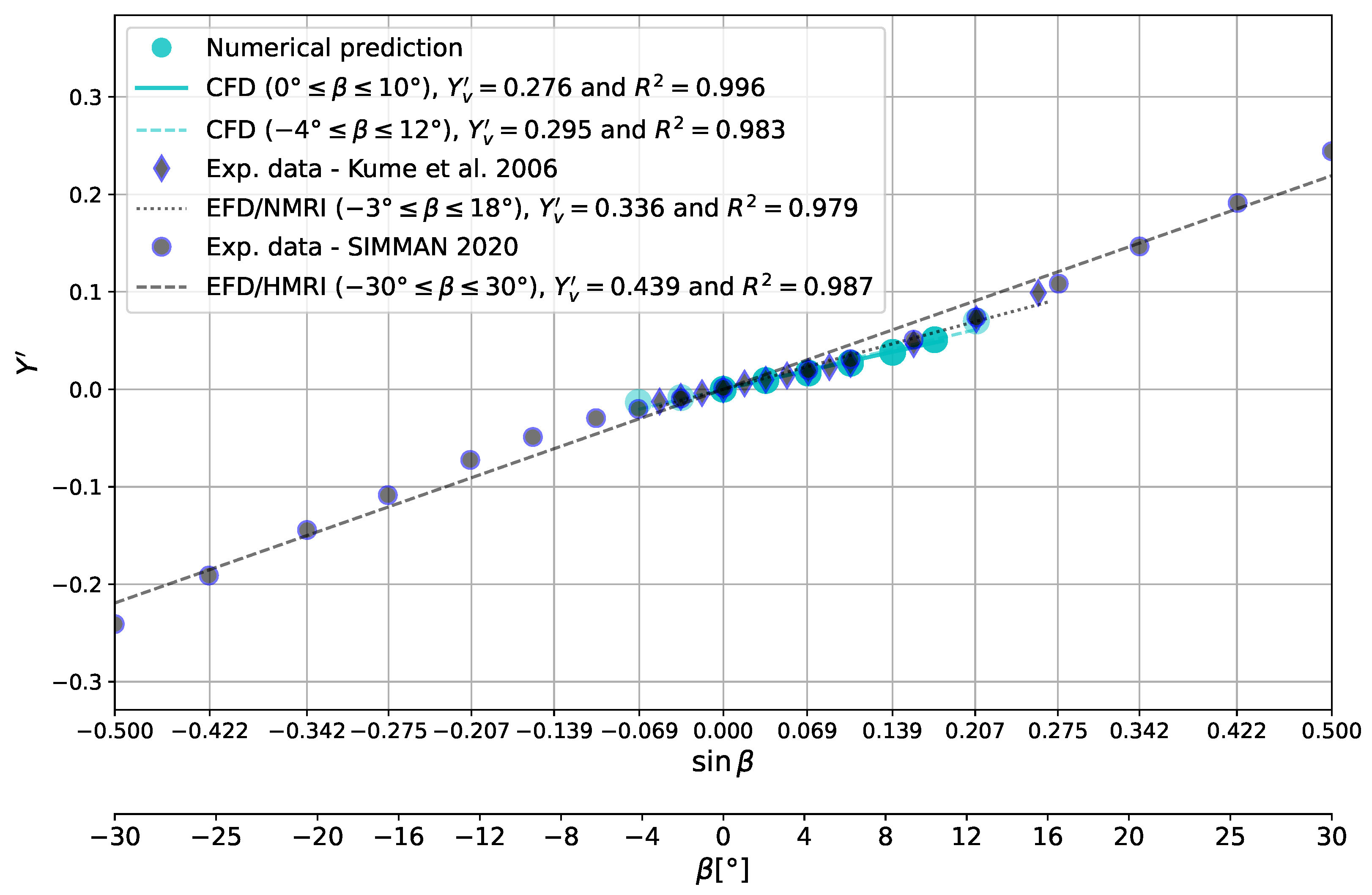

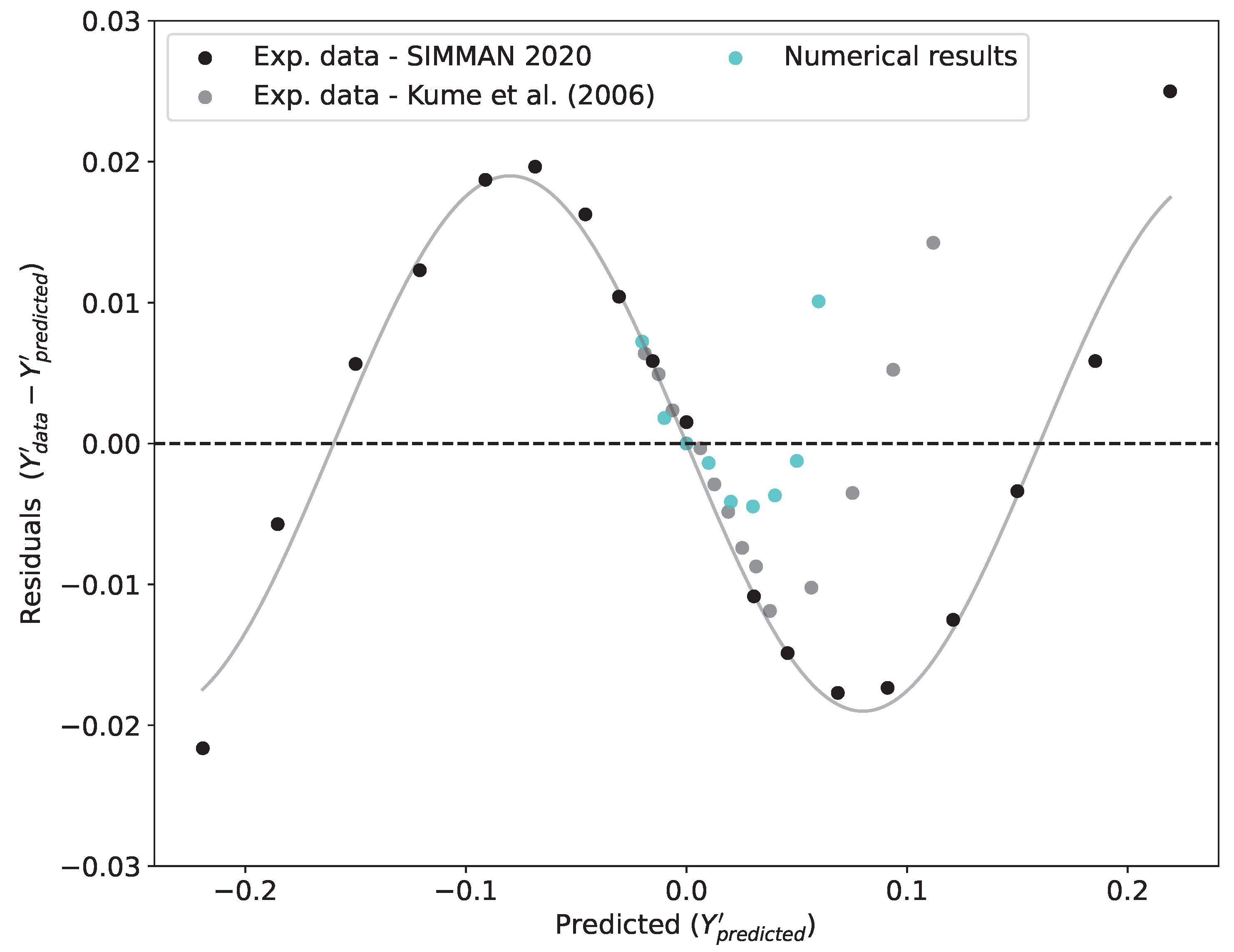

A key metric for evaluating numerical progress is the reduction in prediction error for the lateral force derived from Virtual static drift tests (VSDT).

Table 3 summarizes key comparisons between numerical studies employing captive model tests. The data reveal a significant improvement in lateral force (

) prediction accuracy over time, which correlates strongly with a substantial increase in computational mesh density. The absolute error dropped from

in the late 1990s to

by the mid-2010s, reflecting major developments in numerical methods and computational power.

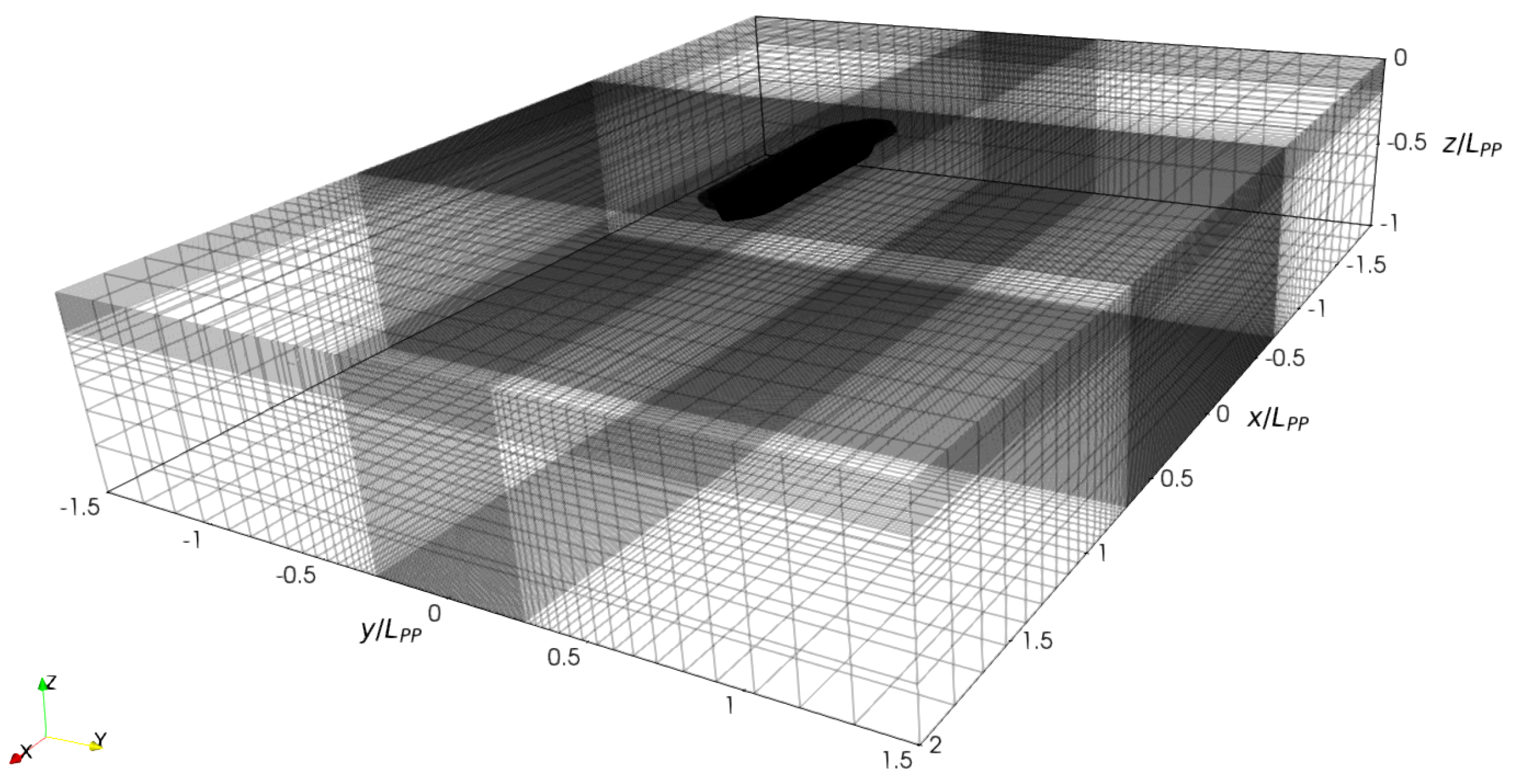

Advancements in CFD for hydrodynamic applications have been well benchmarked in blind workshops to validate numerical methods. While historical conferences, such as the Gothenburg Workshop in 2000 or the Lloyd’s Register workshop, focused primarily on ship resistance and scale effects, Workshop on Verification and Validation of Ship Manoeuvring Simulation Methods (SIMMAN) aims to assess up-to-date methods for ship maneuvering prediction. This dedicated workshop serves as a critical metric for evaluating viscous-flow calculations used for static and dynamic maneuvers. Several organizations were invited to submit blind responses to well-specified test cases. The first edition was held in 2008, and participants sent computations performed on meshes of up to 7M cells for the virtual captive model tests. In SIMMAN’20 [

38], the largest grid was up to 30M. Over the twelve-year interval, numerical methods for maneuvering proliferated, increasing the number of submissions and resulting in fair prediction accuracy; for example, SIMMAN’20 reported an average error of

for oblique force predictions. This growing reliance on computational methods enhances the efficacy of maneuvering prediction, and the data collected on numerical settings (such as the widespread use of the double-body model for the air–water interface and the

k-

SST turbulence model) provide essential guidance for future research. Ref. [

41] numerically examines the effects of bulbous bows on the hydrodynamic forces acting on a tanker-shaped hull by conducting virtual static drift tests and compares the maneuverability of three bow-variant ships. Among the hulls tested, the one with a protruding bow experiences the lowest linear sway velocity derivative, whereas those with a shrink bow experience larger lateral forces. Most previously introduced empirical formulations were derived from experimental results based on a database of hulls with shrink bulbous bows, and there is a need for a deeper understanding of how this apparatus will affect maneuvering performance. Ref. [

42] employed virtual captive model tests to propose new maneuvering coefficients of an Abkowitz-type maneuvering model, incorporating water depth-dependent correction on each component. The authors conducted RANS simulations at five different depth-to-draft ratios to build the new approach. Their model was validated against reference cases, demonstrating that CFD can be applied to complex problems such as shallow-water flows.