Local Scour Around Tidal Stream Turbine Foundations: A State-of-the-Art Review and Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

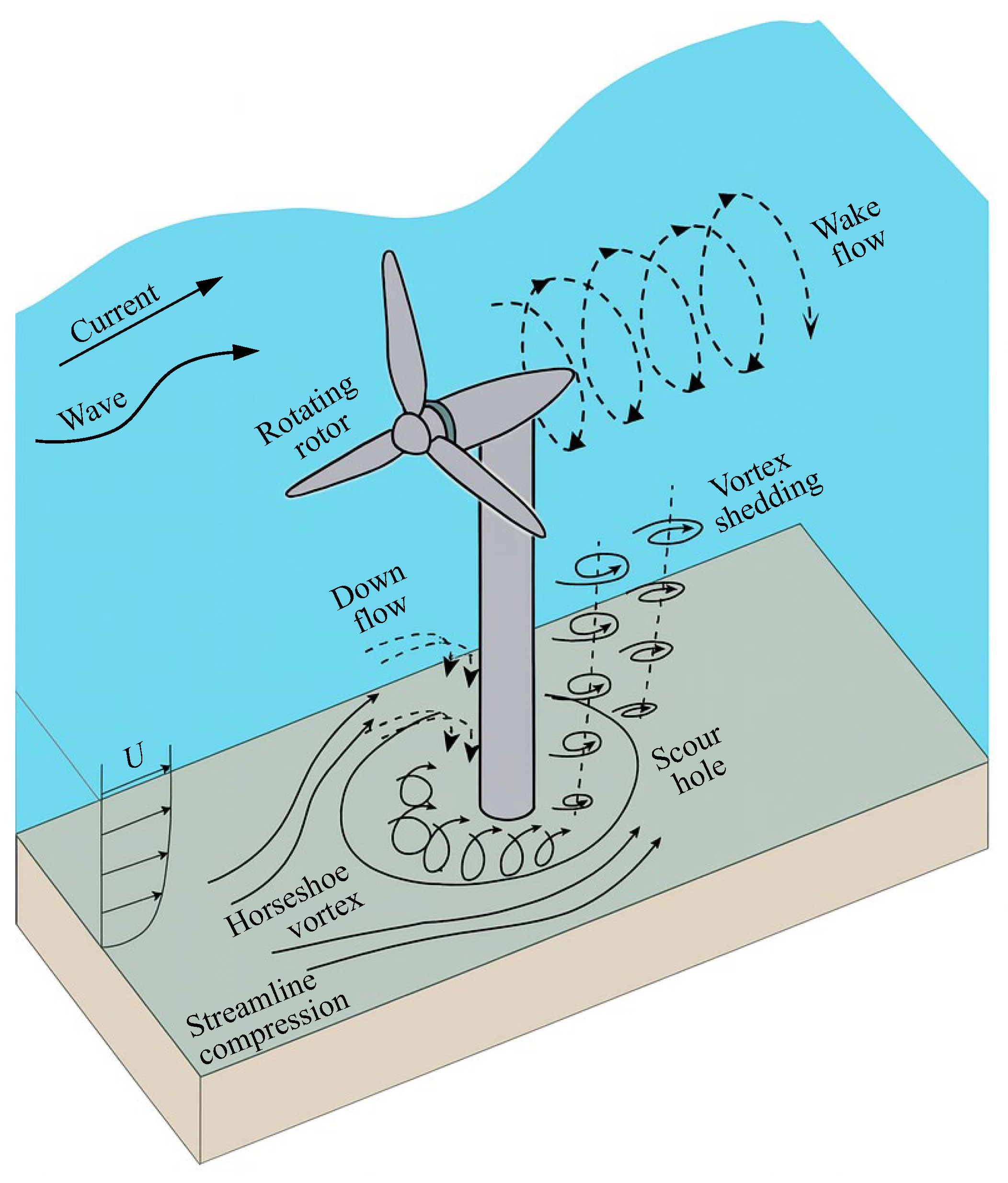

2. Scour Mechanisms Induced by Rotor Rotation

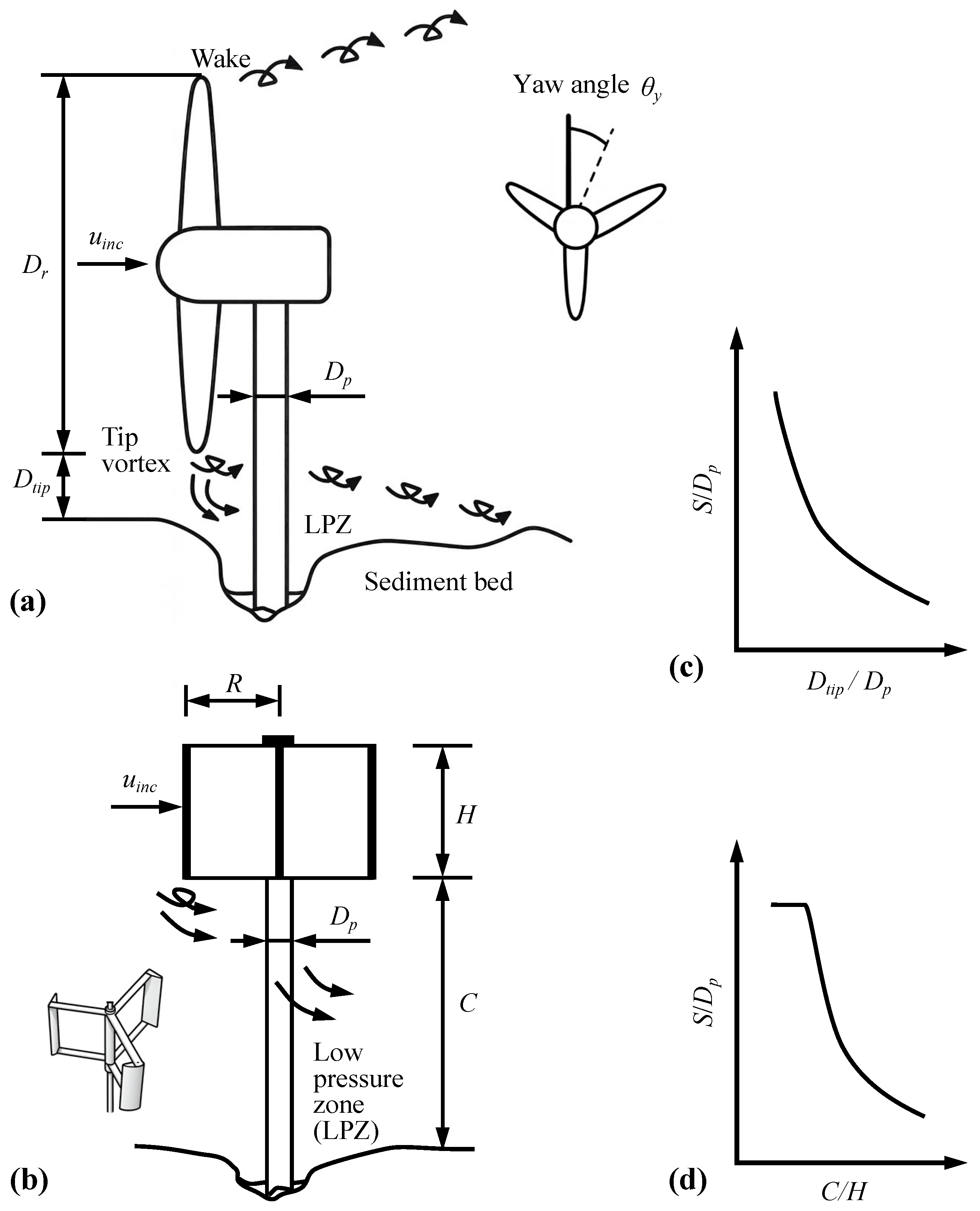

2.1. Hydrodynamic Acceleration Effect

2.2. The Decisive Role of Tip Clearance

2.3. Control of Scour by Helical Wake and Yaw Effects

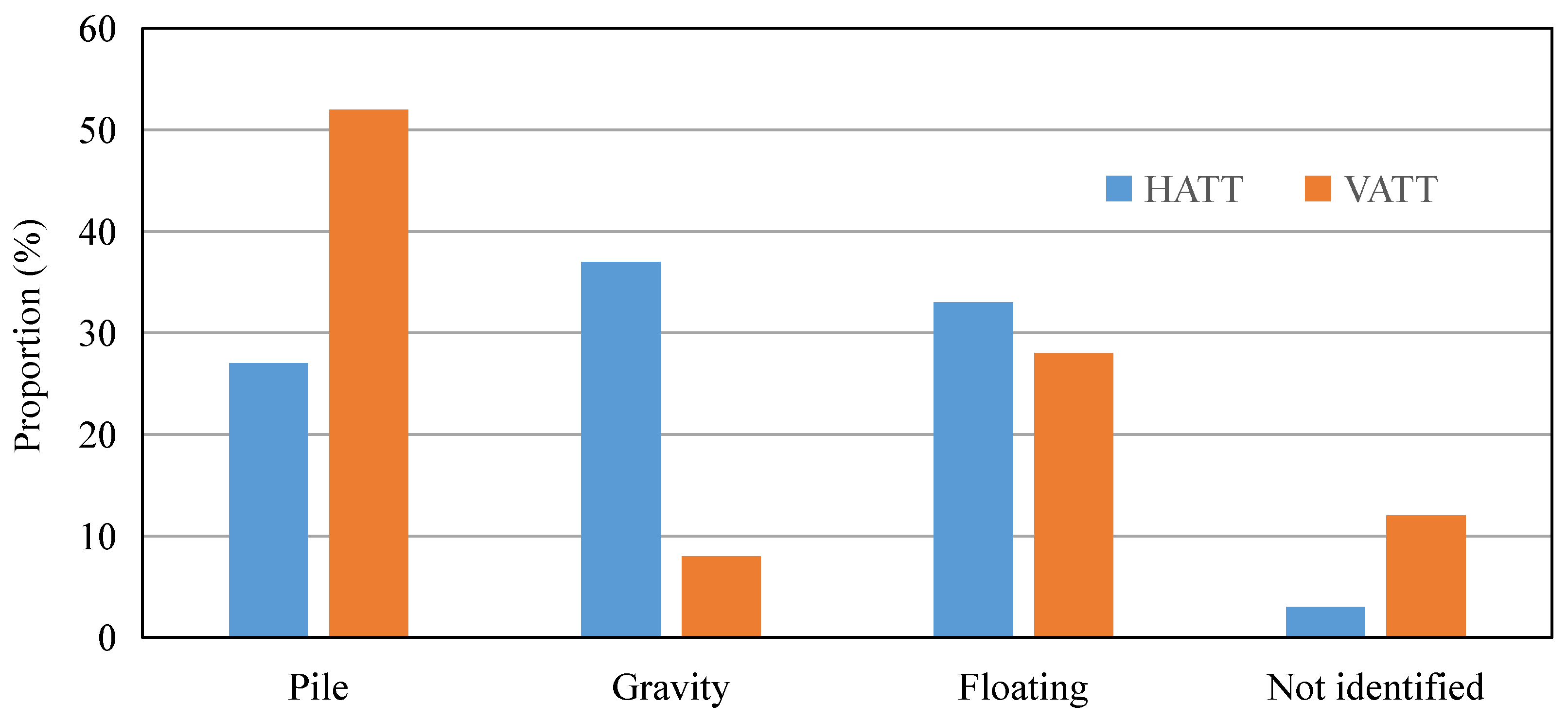

3. Scour Characteristics of Different Foundations

3.1. Monopile Foundation

3.2. Tripod and Jacket Foundations

3.3. Gravity-Based Foundations and Hybrid Structures

4. Seabed Response Under Wave–Current–Turbine Coupling

4.1. Multiphysics Coupling Framework

4.2. Dynamic Stress Amplification and Liquefaction Risk

4.3. Hydrodynamic Wake Modification Under Wave Action

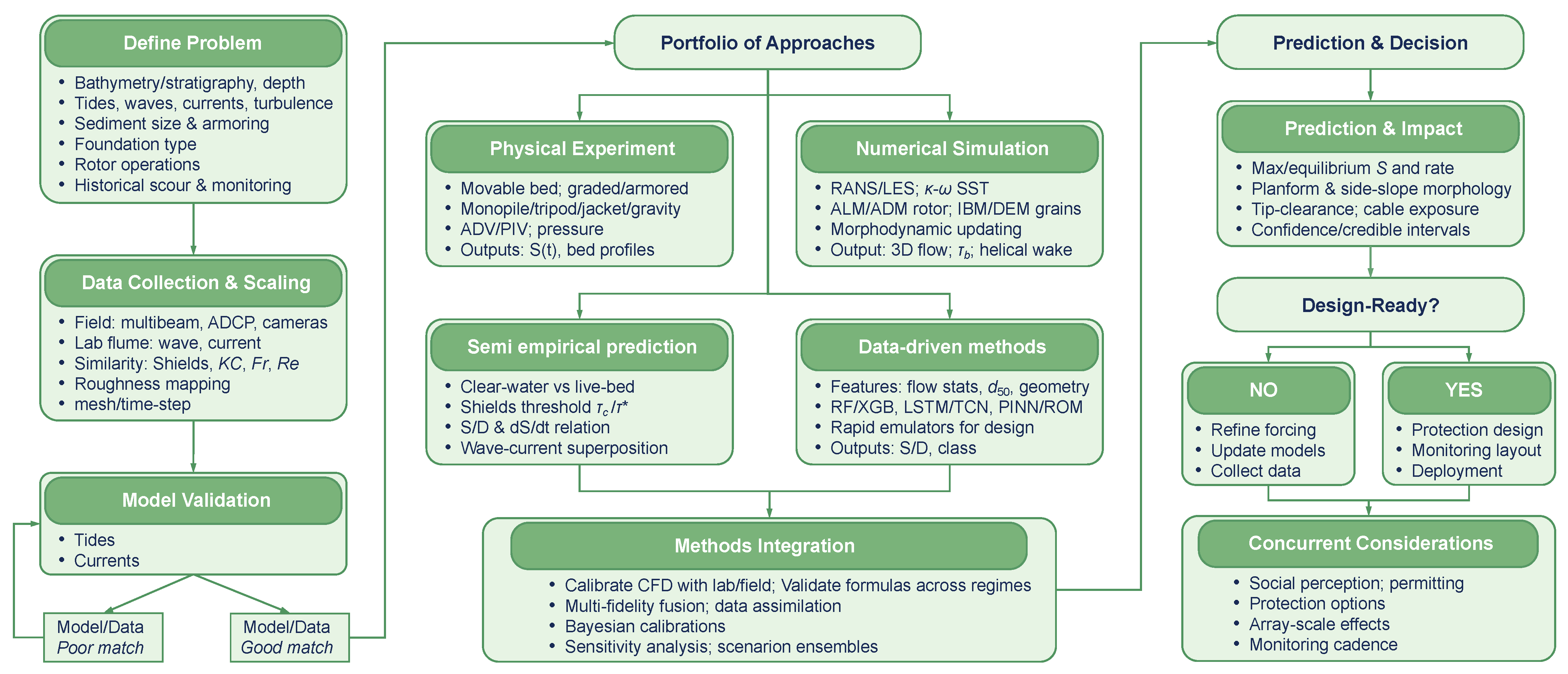

5. Scour Prediction and Modeling Methodologies

5.1. Physical Model Experiments

5.2. Numerical Simulation Techniques

5.3. Semi-Empirical Prediction Models

5.4. Data-Driven Methods

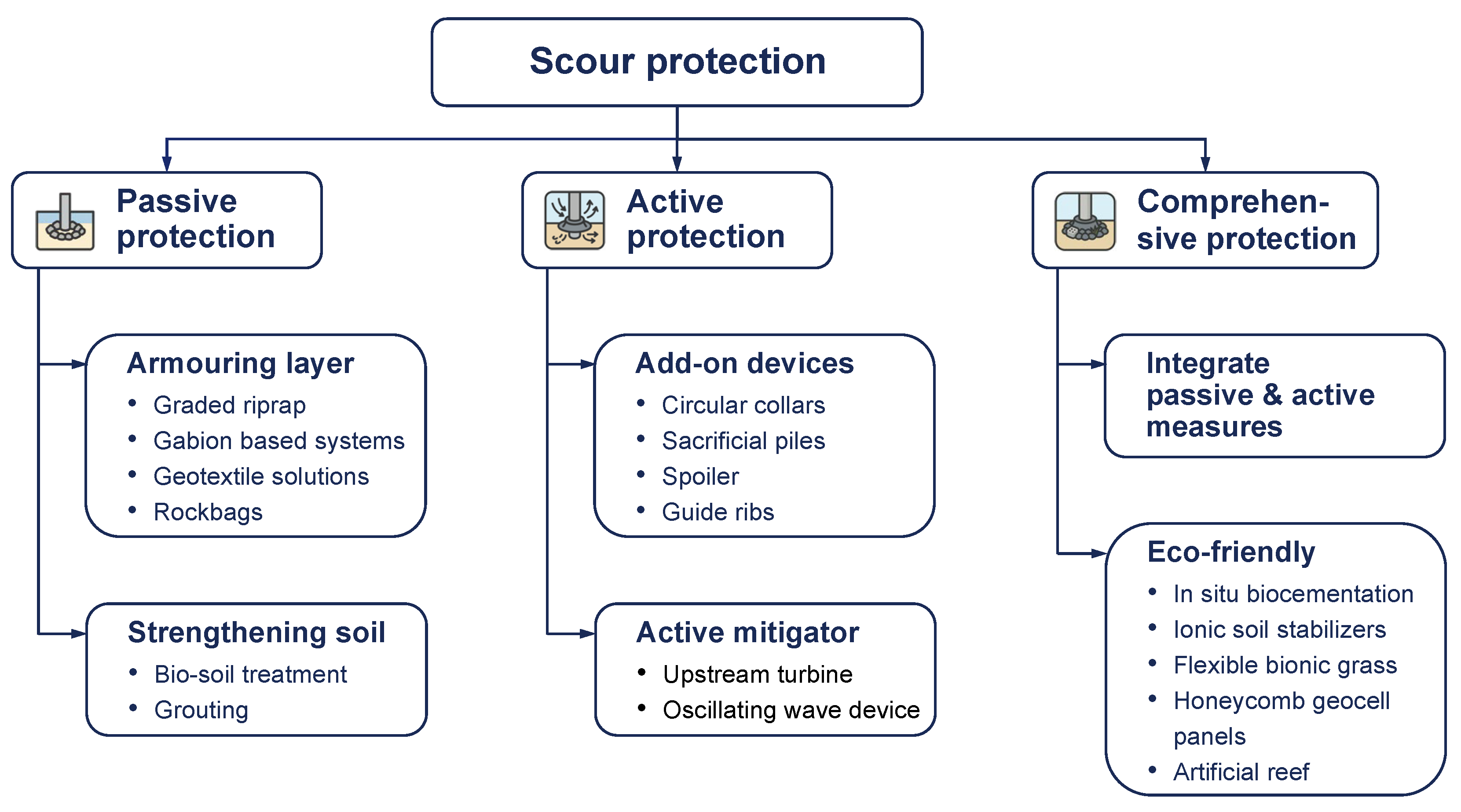

6. Scour Protection and Innovative Mitigation Strategies

6.1. Passive Protection

6.2. Active Protection

6.3. Eco-Integrated Comprehensive Protection

7. Engineering Context, Challenges, and Future Outlook

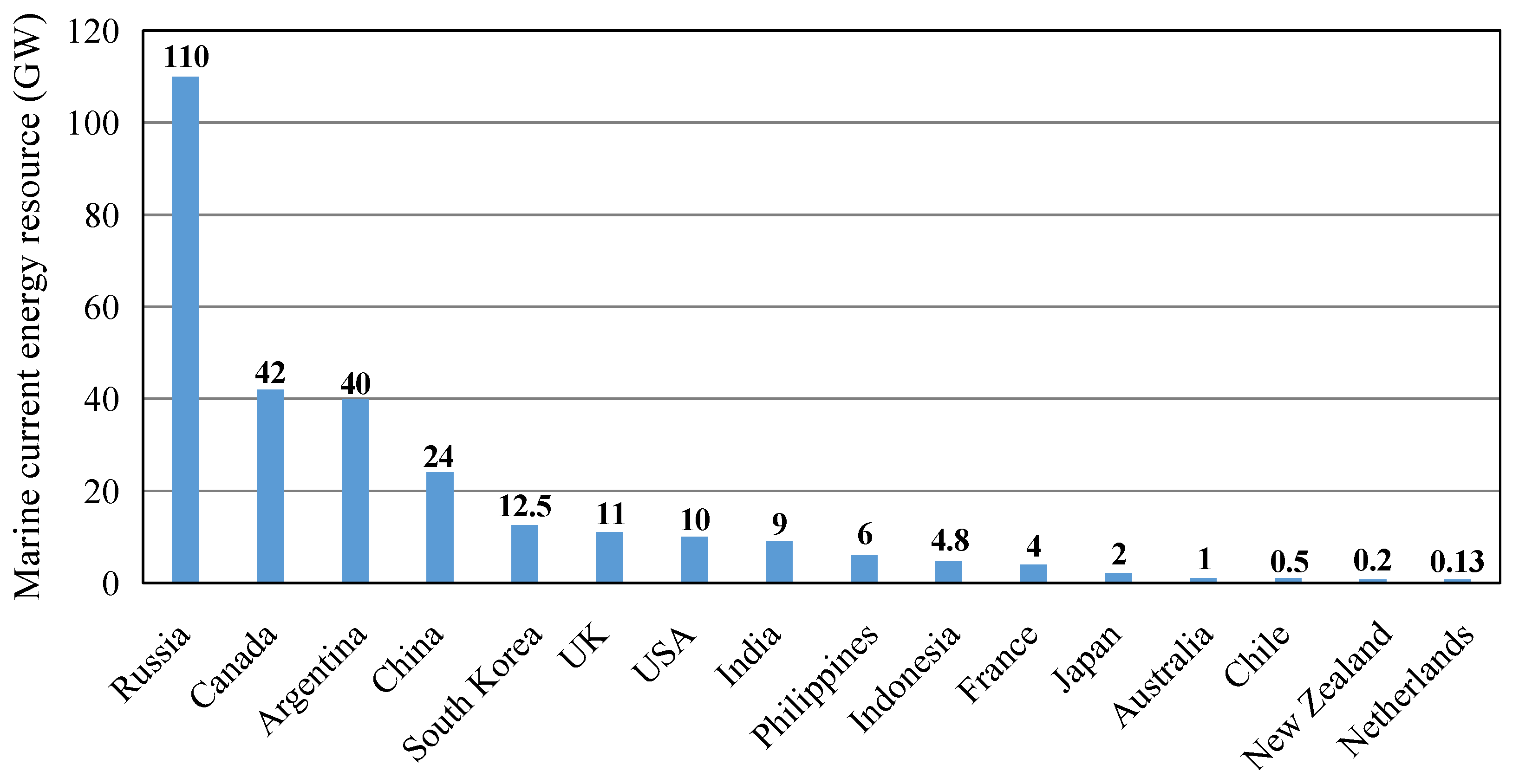

7.1. Global Development Status

7.2. Array-Scale Scour Effects as a Critical Research Gap

7.3. Future Directions

7.3.1. Multiphysics Coupling and Advances in Experimental Methodology

7.3.2. Uncertainty Analysis and Scale-Effect Assessment

7.3.3. Establishment of Relevant Technical Standards

7.3.4. Development of Intelligent Predictive Tools

7.3.5. Fully Coupled Assessment of Structural Safety and Ecological Effects

7.3.6. Novel Foundation Concepts and Strategies for Monitoring and Intervention

8. Conclusions

- Rotor rotation significantly intensifies scour. Compared with monopiles without turbines, periodic operation of the turbine rotor imposes strong perturbations on the near-bed flow, which increases the scour rate and elevates the equilibrium depth. The wake and tip vortices generated by rotating blades are primary drivers of this amplification, and the final depth decreases with increasing tip clearance.

- Reversing tidal currents produce distinct scour behavior. Under realistic flood and ebb conditions, depth exhibits cyclical fluctuations with cumulative growth, and the maximum depth under two-directional forcing is slightly smaller than that under an equivalent unidirectional current. Sites with intermittent strong currents require explicit consideration of tidal phase in scour evolution.

- Scour around multi-pile foundations is spatially nonuniform. For tripod and similar layouts, pit geometry depends on leg arrangement and installation heading, and different legs can experience markedly different depths. Appropriate layout and targeted local protection are important for such foundations.

- Coupled waves and currents amplify seabed response. When a rotor operates with waves present, dynamic stresses and pore pressure responses in the bed increase, and the risk of transient liquefaction grows. Assessment of coupled scour and liquefaction under extreme sea states is required, together with measures that improve resistance to liquefaction.

- Innovation in prediction and protection is advancing practice. Numerical modeling such as ALM with IBM coupling and revised empirical relations has improved predictive skill. New mitigation concepts that exploit turbine wake effects and ecologically integrated protection show promising performance and provide additional engineering options.

- Future directions emphasize stronger field evidence and standardization, attention to cumulative scour within arrays and to foundation–structure interaction, and integration of artificial intelligence into monitoring, early warning, and predictive tools so that research outcomes translate effectively into engineering application.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- von Jouanne, A.; Agamloh, E.; Yokochi, A. A review of offshore renewable energy for advancing the clean energy transition. Energies 2025, 18, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, V.; Bhuiyan, M.A. Tidal energy-path towards sustainable energy: A technical review. Clean Energy Syst. 2022, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zou, T.; Liu, H.; Lin, Y.; Ren, H.; Li, Q. Status and challenges of marine current turbines: A global review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Ocean Energy and Net Zero: An International Roadmap to Develop 300GW of Ocean Energy by 2050. Available online: https://www.ocean-energy-systems.org/publications/oes-documents/market-policy-/document/ocean-energy-and-net-zero-an-international-roadmap-to-develop-300gw-of-ocean-energy-by-2050/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Ji, R.; Sun, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yin, M.; Kong, M.; Reabroy, R. A review of ocean tidal current energy technology: Advances, trends, and challenges. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 071308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambel, J.; Fazeres-Ferradosa, T.; Miranda, F.; Bento, A.M.; Taveira-Pinto, F.; Lomonaco, P.A. comprehensive review on scour and scour protections for complex bottom-fixed offshore and marine renewable energy foundations. Ocean Eng. 2024, 304, 117829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. Scour around a mono-pile foundation of a horizontal axis tidal stream turbine under steady current. Ocean Eng. 2019, 192, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, M.; Wolf, J.; Williams, A.J.; Badoe, C.; Masters, I. Local and regional interactions between tidal stream turbines and coastal environment. Renew. Energy 2024, 229, 120665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Wang, D.; Qin, C.; Duan, L. Local scour around marine structures: A comprehensive review of influencing factors, prediction methods, and future directions. Buildings 2025, 15, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RIT Energy. Roosevelt Island Tidal Energy (RITE) Environmental Assessment Project: Final Report; Prepared for the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority by Verdant Power, Report 11-04; Verdant Power: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Polagye, B.; Copping, A.; Kirkendall, K.; Boehlert, G.; Walker, S.; Wainstein, M.; Van Cleve, B. Environmental Effects of Tidal Energy Development: A Scientific Workshop; NMFS F/SPO-116, NOAA; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sangiuliano, S.J. Planning for tidal current turbine technology: A case study of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Guan, D.; Zheng, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, B. Scour processes around a mono-pile foundation under bi-directional flow considering effects from a rotating turbine. Ocean Eng. 2023, 269, 113401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lam, W.-H. Slipstream between marine current turbine and seabed. Energy 2014, 68, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, K.; Chen, H. Seabed dynamic response of monopile foundation for tidal stream turbine. J. Changjiang River Sci. Res. Inst. 2023, 40, 88–95, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, P.; Zheng, J.; Wu, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, T. Current-induced seabed scour around a pile-supported horizontal- axis tidal stream turbine. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2015, 23, 929–936. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Guan, D.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, E.; Gao, L. Scour processes around a horizontal axial tidal stream turbine supported by the tripod foundation. Ocean Eng. 2024, 296, 116891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hashim, R.; Othman, F.; Motamedi, S. Experimental study on scour profile of pile-supported horizontal axis tidal current turbine. Renew. Energy 2017, 114, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Musa, M.; Chamorro, L.P.; Ellis, C.; Guala, M. Local scour around a model hydrokinetic turbine in an erodible channel. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2014, 140, 04014037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lam, W.H.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, J.; Guo, J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Tan, T.H.; Chuah, J.H.; et al. Empirical model for Darrieus type tidal current turbine induced seabed scour. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 171, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X. Proposal of actuator line immersed boundary coupling model for tidal stream turbine modeling with hydrodynamics upon scouring morphology. Energy 2024, 292, 130451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcock, T.A.A.; Draper, S.; Willden, R.H.J.; Vogel, C.R. The fluid mechanics of tidal stream energy conversion. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2021, 53, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lam, W.H.; Cui, Y.; Jiang, J.; Sun, C.; Guo, J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Lam, S.S.; Hamill, G. Tip bed velocity and scour depth of horizontal axis tidal turbine with consideration of tip clearance. Energies 2019, 12, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lam, W.H.; Lam, S.S.; Dai, M.; Hamill, G. Temporal evolution of seabed scour induced by Darrieus-type tidal current turbine. Water 2019, 11, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjadian, P.; Neill, S.P.; Barclay, V.M. Characterizing seabed sediments at contrasting offshore renewable energy sites. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1156486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mendoza, R.; Murdoch, L.; Jordan, L.B.; Amoudry, L.O.; McLelland, S.; Cooke, R.D.; Thorne, P.; Simmons, S.M.; Parsons, D.; Vezza, M. Asymmetric effects of a modelled tidal turbine on the flow and seabed. Renew. Energy 2020, 159, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, G.; Guo, Y.; Chen, H. Experimental investigation on wake and thrust characteristics of a twin-rotor horizontal axis tidal stream turbine. Renew. Energy 2022, 195, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, M.; Ravanelli, G.; Bertoldi, W.; Guala, M. Hydrokinetic turbines in yawed conditions toward synergistic fluvial installations. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 146, 04020019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S. Coupled experimental–numerical analysis of energy harvesting dynamics of tidal stream turbine: Synergistic effects of operational status and morphological evolution in wave–current environments. Appl. Energy 2025, 396, 126311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Bhuyan, G.; Iqbal, M.T.; Quaicoe, J.E. Hydrokinetic energy conversion systems and assessment of horizontal and vertical axis turbines for river and tidal applications: A technology status review. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, 1823–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schendel, A.; Hildebrandt, A.; Goseberg, N.; Schlurmann, T. Processes and evolution of scour around a monopile induced by tidal currents. Coastal Eng. 2018, 139, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Lin, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J. Experimental study on scour process around mono-pile foundation of a tidal stream turbine under bidirectional flow. J. Hohai Univ. 2022, 50, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, R.J.S.; Stroescu, E.I. Scour depth development at piles of different height under the action of cyclic tidal flow. Coastal Eng. 2023, 179, 104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, Y.; Ding, Z. Experimental analysis and proposal of semi-empirical prediction model on tidal stream turbine induced local scour subjected to wave–current loading. Ocean Eng. 2025, 327, 121020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asumadu, R.; Zhang, J.; Osei-Wusuansa, H. 3-D numerical study of offshore tripod wind turbine pile foundation on wave-induced seabed response. Ocean Eng. 2022, 255, 111421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lai, J.; Lin, X.; Deng, X. Local scour depth evolution characteristics of tripod pile foundation for a tidal current energy turbine. J. Hohai Univ. 2025, 53, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Hou, D.; Guo, Y. On the local scour around a jacket foundation under bidirectional flow loading. Ocean Eng. 2024, 310 Pt 2, 118772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.; Gavin, K.; Doyle, T. Design of shallow foundations for tidal-stream energy structures. In Proceedings Fourth International Symposium on Frontiers in Offshore Geotechnics; Westgate, Z., Ed.; University of Texas: Austin, USA, 2020; Volume 3587, pp. 1805–1815. [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty, T.; O’Doherty, D.M.; Mason-Jones, A. Tidal energy technology. In Wave and Tidal Energy; Greaves, D., Iglesias, G., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, O.; Cossu, R.; Heatherington, C.; Hunter, S.; Baldock, T.E. Field observations of scour behavior around an oscillating water column wave energy converter. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, T.; Tong, X.; Wang, Z.; Song, H.; Lun, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L. Design and analysis of the anti-scour offshore wind-wave energy converter: Scour characteristics and hydrodynamic mechanism. Ocean Eng. 2025, 339, 122210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Law, A.W.-K.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X. Two phase fluid-actuator line-immersed boundary coupling for tidal stream turbine modeling with scouring morphology under wave-current loading. Energy 2025, 329, 136757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Zhang, X.; Ji, R.; Wu, H.; Yin, M.; Liu, H.; Sun, K.; Reabroy, R. Effects of wave-current interaction on hydrodynamic performance and motion response of a floating tidal stream turbine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksen, M.M.; Seyedzadeh, H.; Anjiraki, M.G.; Craig, J.; Flora, K.; Santonia, C.; Sotiropoulos, F.; Khosronejad, A. Large eddy simulation of a utility-scale horizontal axis turbine with woody debris accumulation under live bed conditions. Renew. Energy 2025, 239, 122110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sotiropoulos, F.; Conde, S.M.J.; Khosronejad, A. Large-eddy simulation of a hydrokinetic turbine mounted on an erodible bed. Renew. Energy 2017, 113, 1419–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjiraki, M.G.; Aksen, M.M.; Shapourmiandouab, S.; Craig, J.; Khosronejad, A. Computational study of a utility-scale vertical-axis MHK turbine: A coupled approach for flow–sediment–actuator modeling. Fluids 2025, 10, 304. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, X. Coupled BEM and two-phase mixture model for surrounding flow of horizontal axial turbine over sediment seabed. Ocean Eng. 2022, 261, 112127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zang, W.; Zheng, J.; Cappietti, L.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, E. The influence of waves propagating with the current on the wake of a tidal stream turbine. Appl. Energy 2021, 290, 116729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, E.; Zang, W.; Ji, R. Power fluctuation and wake characteristics of tidal stream turbine subjected to wave and current interaction. Energy 2023, 264, 126185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Mei, Y.; Shi, M.; Wang, S.Q.; Sheng, Q.H. Development of experimental methods for horizontal-axis tidal turbines. J. Hydroelectr. Eng. 2023, 42, 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.S.; Yu, S.Q.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.R.; Wang, F.Y. Research progress on hydrodynamics and layout optimization of tidal stream turbine array. J. Hohai Univ. 2024, 52, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, P.; Liu, X.D.; Si, X.C.; Wang, S.J.; Tan, J.Z.; Zheng, Z.S. Research on influence of horizontal axial tidal turbine array on regional tidal regime. J. Ocean Univ. China 2019, 49, 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.H.; Deng, Q.; Li, J.; Shi, H.D. Progress of marine energy test sites and its inspiration. Coast. Eng. 2025, 44, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Lam, W.-H. Methods for predicting seabed scour around marine current turbine. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; Lin, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, H. Experimental investigation of wake and thrust characteristics of a small-scale tidal stream turbine array. Ocean Eng. 2023, 283, 115038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mendoza, R.; Amoudry, L.O.; Thorne, P.D.; Cooke, R.D.; McLelland, S.J.; Jordan, L.B.; Simmons, S.M.; Parsons, D.R.; Murdoch, L. Laboratory study on the effects of hydro kinetic turbines on hydrodynamics and sediment dynamics. Renew. Energy 2018, 129, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zang, W.; Lin, X.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, E. Experimental study of the wake homogeneity evolution behind a horizontal axis tidal stream turbine. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 111, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lam, W.H.; Dai, Y.; Hamill, G. Prediction of seabed scour induced by full-scale Darrieus-type tidal current turbine. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lin, X.; Wang, R.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y. Flow structures in wake of a pile-supported horizontal axis tidal stream turbine. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 2321–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Experimental investigation of the seabed topography effects on tidal stream turbine behavior and wake characteristics. Ocean Eng. 2023, 281, 114682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Lam, W.H.; Robinson, D.; Hamill, G. Temporal and spatial scour caused by external and internal counter-rotating twin-propellers using Acoustic Doppler Velocimetry. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 97, 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schendel, A.; Welzel, M.; Hildebrandt, A.; Schlurmann, T.; Hsu, T.-W. Role and impact of hydrograph shape on tidal current-induced scour in physical-modelling environments. Water 2019, 11, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, S.M.; McLelland, S.J.; Parsons, D.R.; Murphy, B.J.; Jordan, L.B.; Vybulkova, L. Flume measurements of the wake of two model horizontal-axis tidal stream turbines. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Hydraulic Structures, Coimbra, Portugal, 8–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zang, W.; Lin, X.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, E. Experimental investigation into effects of boundary proximity and blockage on horizontal-axis tidal turbine wake. Ocean Eng. 2021, 225, 108829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedoul, F.; Obregon, M.; Ortega-Casanova, J.; Fernandez-Feria, R. Experimental study of the erosion in a sand bed caused by wakes behind tidal energy extraction devices. In Proceedings of the European Seminar OWEMES 2012, Málaga, Spain, 5–7 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J. Experimental investigation into downstream field of a horizontal axis tidal stream turbine supported by a mono pile. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 101, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Apsley, D.; Afgan, I.; Stallard, T.; Stansby, P. Fluctuating loads on a tidal turbine due to velocity shear and turbulence: Comparison of CFD with field data. Renew. Energy 2017, 112, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojasteh, D.; Shamsipour, A.; Huang, L.; Tavakoli, S.; Haghani, M.; Flocard, F.; Farzadkhoo, M.; Iglesias, G.; Hemer, M.; Lewis, M.; et al. A large-scale review of wave and tidal energy research over the last 20 years. Ocean Eng. 2023, 282, 114995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, M.; Amoudry, L.O.; Ramirez-Mendoza, R.; Thorne, P.D.; Song, Q.; Zheng, P.; Simmons, S.M.; Jordan, L.-B.; McLelland, S.J. Three-dimensional modelling of suspended sediment transport in the far wake of tidal stream turbines. Renew. Energy 2020, 151, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, E.; Zheng, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gu, H.; Zang, W.; Lin, X. A review on numerical development of tidal stream turbine performance and wake prediction. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 79325–79337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Shi, W.; Xu, Y.; Song, Y. Actuator disk theory and blade element momentum theory for the force-driven turbine. Ocean Eng. 2023, 285, 115488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairley, I.; Masters, I.; Karunarathna, H. The cumulative impact of tidal stream turbine arrays on sediment transport in the Pentland Firth. Renew. Energy 2015, 80, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, C.; Zang, W.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, E. Experimental analysis and evaluation of the numerical prediction of wake characteristics of tidal stream turbine. Energies 2017, 10, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, J.; Ren, T.; Yu, F.; Cen, Y.; Li, C.; Yuan, S. Review of research on wake characteristics in horizontal-axis tidal turbines. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, C.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, E. Numerical investigation on the wake and energy dissipation of tidal stream turbine with modified actuator line method. Ocean Eng. 2024, 293, 116608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.A.; Venugopal, V. Wake field interaction in 3D tidal turbine arrays: Numerical analysis for the Pentland Firth. J. Waterw. Port Coastal Ocean Eng. 2024, 150, 04024013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, S.P.; Haas, K.A.; Thiébot, J.; Yang, Z. A review of tidal energy—Resource, feedbacks, and environmental interactions. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2021, 13, 062702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, F. Modelization of the Interactions Between Turbine and Sediment Transport, Using the Blade Element Momentum Theory. Doctoral Thesis, Normandie Université, Caen, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S. Comparison of actuator line method and full rotor geometry simulations of the wake field of a tidal stream turbine. Water 2019, 11, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apsley, D.D.; Stallard, T.; Stansby, P.K. Actuator-line CFD modelling of tidal-stream turbines in arrays. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy 2018, 4, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, S.T.; Broström, G.; Bergqvist, B.; Lennblad, J.; Nilsson, H. Modelling Deep Green tidal power plant using large eddy simulations and the actuator line method. Renew. Energy 2021, 179, 1140–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sotiropoulos, F. A new class of actuator surface models for wind turbines. Wind Energy 2018, 21, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycek, P.; Gaurier, B.; Germain, G.; Pinon, G.; Rivoalen, E. Experimental study of the turbulence intensity effects on marine current turbines behaviour. Part I: One single turbine. Renew. Energy 2014, 66, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; García, M.H. Three-dimensional numerical model with free water surface and mesh deformation for local sediment scour. J. Waterw. Port Coastal Ocean Eng. 2008, 134, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, J.; Guan, D.; Wang, R. Semi-theoretical prediction for equilibrium scour depth of a mono-pile supported tidal stream turbine. Ocean Eng. 2023, 275, 114093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, M.; Heisel, M.; Guala, M. Predictive model for local scour downstream of hydrokinetic turbines in erodible channels. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2018, 3, 024606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafati, A.; Tafarojnoruz, A.; Motta, D.; Yaseen, Z.M. Application of nature-inspired optimization algorithms to ANFIS model to predict wave-induced scour depth around pipelines. J. Hydroinform. 2020, 22, 1425–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafati, A.; Tafarojnoruz, A.; Yaseen, Z. New stochastic modeling strategy on the prediction enhancement of pier scour depth in cohesive bed materials. J. Hydroinform. 2020, 22, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ren, Z.; Li, H.; Pan, Z.; Xia, W. A review of tidal current power generation farm planning: Methodologies, characteristics and challenges. Renew. Energy 2024, 220, 119603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.-W.; Xie, Y.-X.; Yao, Z.-S.; Chiew, Y.-M.; Zhang, J.-S.; Zheng, J.-H. Local scour at offshore windfarm monopile foundations: A review. Water Sci. Eng. 2022, 15, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Malekjafarian, A.; Salauddin, M. Scour protection measures for offshore wind turbines: A systematic literature review on recent developments. Energies 2024, 17, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhou, P.; Du, F.; Wang, L. Experimental investigation on scour development and scour protection for offshore converter platform. Mar. Struct. 2023, 90, 103440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, X.; Yan, J.; Gao, X. Countermeasures for local scour around offshore wind turbine monopile foundations: A review. Appl. Ocean Res. 2023, 141, 103764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Lian, J.; Wang, H. Mechanisms, assessments, countermeasures, and prospects for offshore wind turbine foundation scour research. Ocean Eng. 2023, 281, 114893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, L.; De Rouck, J.; Troch, P.; Frigaard, P. Empirical design of scour protections around monopile foundations: Part 1: Static approach. Coast. Eng. 2011, 58, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, L.; De Rouck, J.; Troch, P.; Frigaard, P. Empirical design of scour protections around monopile foundations. Part 2: Dynamic approach. Coast. Eng. 2012, 60, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazeres-Ferradosa, T.; Taveira-Pinto, F.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Chambel, J. Probabilistic comparison of static and dynamic failure criteria of scour protections. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, T.U.; Sumer, B.M.; Fredsøe, J.; Raaijmakers, T.C.; Schouten, J.-J. Edge scour at scour protections around piles in the marine environment–Laboratory and field investigation. Coast. Eng. 2015, 106, 42–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafarojnoruz, A.; Gaudio, R.; Calomino, F. Evaluation of flow-altering countermeasures against bridge pier scour. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2012, 138, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahhosseini, M.; Yue, S.; Xu, J.; Zhang, M.; Yu, G. Scour depth at a pile with a collar at bed level in clear-water current. Ocean Eng. 2025, 320, 120319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Melville, B.; Shamseldin, A.; Guan, D.; Singhal, N.; Yao, Z. Experimental study of collar protection for local scour reduction around offshore wind turbine monopile foundations. Coast. Eng. 2023, 183, 104324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liang, F.; Yu, X. Experimental and numerical investigations on the performance of sacrificial piles in reducing local scour around pile groups. Nat. Hazards 2016, 85, 1417–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J. Preventing scour of monopile foundations using a vertical rotation device. Ocean Eng. 2024, 311, 118879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wei, K.; Yang, W.; Li, T.; Qin, B. A feasibility study of reducing scour around monopile foundation using a tidal current turbine. Ocean Eng. 2021, 220, 108396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.H.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.G.; Kashif, A.; Liu, H.W.; Wei, S.S. Study on wake characteristics and influence of anti-scour tidal current turbine under bed interference. J. Vib. Shock 2024, 43, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J. An innovative eco-friendly method for scour protection around monopile foundation. Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 123, 103177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Lu, Y.; Leng, H.; Liu, H.; Shi, W. A novel countermeasure for preventing scour around monopile foundations using Ionic Soil Stabilizer solidified slurry. Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 121, 103121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Xu, S. Numerical simulation of offshore wind power pile foundation scour with different arrangements of artificial reefs. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1178370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.; Sottolichio, A.; Huybrechts, N.; Brunet, P. Tidal turbines in the estuarine environment: From identifying optimal location to environmental impact. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 700–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.L.; Xu, D.H. Research on the development of tidal current energy power generation industry. Bull. Sci. Technol. 2024, 40, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J.C.; Jia, F.Y. Current status, new opportunities and challenges of marine tidal current energy generation technology and equipment in China. Acta Energ. Sol. Sin. 2024, 45, 668–674. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.M.; Ma, C.L.; Chen, F.Y.; Liu, L.; Ge, Y.Z.; Peng, J.P.; Wu, H.Y.; Wang, Q.B. Development, utilization and technological progress of marine renewable energy. Adv. Mar. Sci. 2018, 36, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, D.; Angeloudis, A.; Greaves, D.; Hastie, G.; Lewis, M.; Mackie, L.; McNaughton, J.; Miles, J.; Neill, S.; Piggott, M.; et al. A review of the UK and British Channel Islands practical tidal stream energy resource. Proc. R. Soc. A 2021, 477, 20210469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillou, N.; Charpentier, J.-F.; Benbouzid, M. The Tidal Stream Energy Resource of the Fromveur Strait—A Review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Yu, B.T.; Wu, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.P.; Zhu, L.N.; Wang, X.Y. Development frontiers and selection recommendations for tidal current energy generation devices. Acta Energ. Sol. Sin. 2025, 46, 690–695. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Shi, H.D.; Liu, Z.; Han, Z.; Cao, F.F.; Yu, T.S.; Wang, Y.Q.; Lun, Z.X.; Liu, H.W.; Sun, K. Research status and future development suggestions of marine energy in China. Sol. Energy 2024, 363, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Angeloudis, A.; Kramer, S.C.; He, R.; Piggott, M.D. Interactions between tidal stream turbine arrays and their hydrodynamic impact around Zhoushan Island, China. Ocean Eng. 2022, 246, 110431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apsley, D.D. CFD simulation of tidal-stream turbines in a compact array. Renew. Energy 2024, 224, 120133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badoe, C.E.; Li, X.; Williams, A.J.; Masters, I. Output of a tidal farm in yawed flow and varying turbulence using GAD-CFD. Ocean Eng. 2024, 294, 116736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Cheng, X.; Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, C.; Ren, Z. Investigating tidal stream turbine array performance considering effects of number of turbines, array layouts, and yaw angles. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.R.; Li, S.G.; Mei, Y.L. Influence analysis of wake structure in series horizontal-axis tidal current turbine units. Ship Sci. Technol. 2025, 47, 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, M.; Hill, C.; Sotiropoulos, F.; Guala, M. Performance and resilience of hydrokinetic turbine arrays under large migrating fluvial bedforms. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, M.; Hill, C.; Guala, M. Interaction between hydrokinetic turbine wakes and sediment dynamics: Array performance and geomorphic effects under different siting strategies and sediment transport conditions. Renew. Energy 2019, 138, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, P.E.; Neill, S.P.; Lewis, M.J. Impact of tidal-stream arrays in relation to the natural variability of sedimentary processes. Renew. Energy 2014, 72, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, S.P.; Jordan, J.R.; Couch, S.J. Impact of tidal energy converter (TEC) arrays on the dynamics of headland sand banks. Renew. Energy 2012, 37, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Lu, B.; Lin, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, S. Experimental investigation of motion response and mooring load of semi-submersible tidal stream energy turbine under wave-current interactions. Ocean Eng. 2024, 300, 117445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.N.; Wang, X.N.; Guo, Y.; Jia, N.; Chen, Q. Research on output power prediction method of tidal current energy generation device based on uncertainty analysis. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2025, 46, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Pan, D.; Cheng, W.; Pan, C. Tidal stream energy resource assessment in the Qiantang River Estuary, China. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2018, 37, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frid, C.; Andonegi, E.; Depestele, J.; Judd, A.; Rihan, D.; Rogers, S.I.; Kenchington, E. The environmental interactions of tidal and wave energy generation devices. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2012, 32, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Existing Formulas | Notation | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Lin et al. [7] | Predicts final scour depth (S) for monopile-supported horizontal axis tidal turbine under steady flow by using a linear function for flow intensity (KI) and a combined linear/quadratic function for tip clearance (Ktip). Dp: pile diameter. Umean: approach mean velocity; Ucr: critical velocity for sediment motion; Dtip: blade-tip clearance to the seabed | Limited Extrapolation Range: The prediction of the Ktip factor includes a threshold of 9.2 Dp where the turbine effect becomes negligible, but this value is extrapolated far beyond the tested range (1 Dp to 5 Dp). Caution is advised when tip clearance exceeds 5 Dp. The model currently ignores the impact of the nacelle |

| Lin et al. [13] | Predicts equilibrium scour depth (S) for a monopile-supported horizontal axis tidal turbine under bi-directional (tidal) flow. It defines S based on extrapolated flow intensity (Ku) and tip clearance (Ktip) factors. Smax: equilibrium scour depth when ku = 1 and ktip = 1; Dr: rotor diameters; Dtip: tip clearance; ucr: critical approach flow velocity; u: flow velocity | Extrapolated Equilibrium: The equilibrium scour depth must be extrapolated from time series data collected over a finite number of tidal cycles. Reduced Scour: This model inherently results in lower predicted scour depths (around 74%) compared to steady unidirectional flow, due to sediment backfilling from reversing currents. The Ktip quadratic relationship is validated only in the range of 0.1 ≤ Dtip/Dr ≤ 0.5 |

| Lin et al. [17] | Predicts the final scour depth (S) for tripod-supported horizontal axis tidal turbine under unsteady simulated tidal flow and steady current conditions. It uses the effective flow work (W∗) approach, correlating scour development with the work exerted by flow velocity exceeding the incipient scour velocity. De: foundation diameter; c1, c2 and c3: fitting coefficients; ρs: sediment density; ρ: water density; g: gravity acceleration; Dp: leg diameter of the tripod foundation; u: time-varying velocity; uinc: incipient flow velocity | Omission of Tip Clearance: The model is preliminary and based on experiments where the rotor clearance was fixed (0.5 D), thus the critical influence of tip clearance is omitted from the equation formulation. Scale Effects: Disproportionately scaled sediment used in the laboratory causes uncertainties when extrapolating results to prototype dimensions due to differences in ripple formation |

| Chen et al. [18] | Proposes an empirical logarithmic formula for estimating the time-dependent maximum scour depth (S) of pile-supported horizontal axis tidal turbine in clear water scour conditions, drawing parallels from ship-propeller-jet-induced scour models. V∞: free stream velocity; CT: thrust coefficient; ρ density of fluid; ρs: density of sand; Dt: diameter of the turbine disc; C: turbine tip clearance; d50: median sediment grain size; g: gravity acceleration; d50: median diameter | Strong Empirical Constraints: The derived formula is only validated and shows good agreement under specific, narrow experimental conditions: 0.25 ≤ C/Dt ≤ 0.75, 50 ≤ C/d50 ≤ 150, and a fixed densimetric Froude number (F0 = 1.8965). Under/Over Prediction: Conventional pile scour equations are shown to be inapplicable, severely under- or over-predicting the actual scour depth for tidal turbines. |

| Su et al. [20] | Proposes a correction factor (Kt = Kc Kr) to adjust existing pile scour formulas for Darrieus-type vertical-axis tidal turbine scour. Kc incorporates tip clearance and Kr incorporates rotor radius. S: maximum scour depth; Ks: pier shape factor; Kθ: flow angle factor; Kb: bed condition factor; Kd: bed material size factor; Fr: Froude number of incoming flow; Kw: pier width or pile diameter factor; Kyw: depth size factor; KI: flow intensity factor; KD: sediment size factor; KG: channel geometry factor; D: monopile diameter; C: rotor to seabed clearance; H: rotor height; R: rotor radius | Formula Depends on Flow State: The function for the tip clearance correction factor (Kc) must be chosen based on whether the scour is clear water scour (C/H > 0.5) or live bed scour (C/H ≤ 0.5). Complex Rotor Radius Influence: The rotor radius factor (Kr) exhibits a complex non-linear relationship (inverse correlation with the power coefficient CP), which requires fitting using a modified Gaussian probability distribution. |

| Zhang et al. [23] | Estimates maximum scour depth (S) using a turbine coefficient (Kt) derived theoretically by relating it to the accelerated tip-bed velocity (Vtb) Ks: pier shape factor; Kθ: flow angle factor; Kb: bed condition factor; Kd: bed material size factor; Fr: Froude number of incoming flow; Kw: pier width or pile diameter factor; Kv: wave action factor; Kh: correction factor accounting for piles that do not extend over the entire water column; D: monopile diameter; C: rotor to seabed clearance; H: rotor height; Vtb: tip-bed velocity; V∞: free flow velocity | Reliance on Cm Assumption: The core equation for Vtb relies on a complex mass flow coefficient (Cm) which is assumed to be 0.25. This coefficient depends on many factors (e.g., turbulence, flow velocity, turbine parameters) and requires further research. Scour Saturation: The model assumes the scour depth remains constant (Kt = 1.6) when tip clearance is below 0.50 Dt, suggesting scour saturation occurs at small clearances |

| Su et al. [24] | Predicts the temporal evolution of scour depth (S) for Darrieus-type vertical-axis tidal turbine. The coefficients (k1, k2, k3) are complex functions of tip clearance ratio (C/H) and rotor radius ratio (R/D). Uc: mean current velocity; D: monopile diameter; C/H: dimensionless tip clearance; R: rotor radius | Scour-Type Split: Similar to the equilibrium model, the formula is split into two distinct structures depending on whether the condition is clear water scour (C/H > 0.5) or live bed scour (C/H ≤ 0.5). Parameter Sensitivity: The model primarily focuses on turbine parameters (tip clearance, rotor radius); other influential parameters for scour (like sediment diameter and inlet velocity) are considered fixed, and using the model in extreme conditions may introduce errors. |

| Lin et al. [85] | A semi-theoretical framework derived from the phenomenological theory of turbulence. It predicts equilibrium scour depth (S) by calculating an equivalent mean velocity (Um) that captures the combined effects of the thrust coefficient (CT) and tip clearance. Applicable to both clear-water (Uc/Um ≤ 1) and live-bed (Uc/Um > 1) conditions. S: equilibrium scour depth; Dp: monopile diameter; d50: sediment diameter; ρs sediment particle density; ρ: fluid density; Frm: Froude number; Um: equivalent mean velocity; k0, k1 and kc: fitting coefficients; Uc: critical velocity for sediment motion; H: water depth | Assumed Flow Persistence: The framework assumes the accelerated flow beneath the rotor remains dominant and unchanged until it reaches the monopile foundation. This assumption would fail if the distance between the rotor and monopile is substantial. Limited Range Peak: The model only accounts for the first scour depth peak (Um = Uc) because of the limited range of flow intensity considered in the validation data. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Yu, Q.; Pan, D. Local Scour Around Tidal Stream Turbine Foundations: A State-of-the-Art Review and Perspective. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2376. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122376

Liu R, Li Y, Yu Q, Pan D. Local Scour Around Tidal Stream Turbine Foundations: A State-of-the-Art Review and Perspective. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2376. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122376

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ruihuan, Ying Li, Qiuyang Yu, and Dongzi Pan. 2025. "Local Scour Around Tidal Stream Turbine Foundations: A State-of-the-Art Review and Perspective" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2376. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122376

APA StyleLiu, R., Li, Y., Yu, Q., & Pan, D. (2025). Local Scour Around Tidal Stream Turbine Foundations: A State-of-the-Art Review and Perspective. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2376. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122376