1. Introduction

Deep-sea life sciences is one of the core frontier directions in current marine research [

1,

2]. Acquiring high-quality deep-sea biological samples is a prerequisite for morphological analysis, physiological and biochemical assays, genomics [

3], transcriptomics [

4], proteomics sequencing [

5], and other advanced analyses. With the rapid development of deep-sea sampling tools and techniques [

6], most deep-sea benthic animal samples are currently collected using various samplers or traps. However, current sampling systems exhibit certain limitations. Firstly, the abrupt temperature and pressure changes caused by pressure gradient attenuation and exposure to surface seawater significantly reduce the reliability and validity of multiple biological indicators in the samples [

7]. Second, during the 3–5 h recovery process from the seafloor to the ship, samples without any biological stabilization measures are prone to rapid mRNA degradation [

8]. The absence of these key sample preservation techniques has become a limiting factor for the in-depth development of deep-sea life sciences.

In situ fixation technology has been applied to deep-sea samplers [

9], effectively mitigating the problem of mRNA degradation during the interval between sample collection and laboratory analysis. Histological studies using mussel samples as a representative case suggest that mussels should be preserved in situ underwater with a volume fixative 5–10 times that of the sample volume to stabilize and protect cellular RNA [

10]. For highly mobile deep-sea organisms, the typical method involves displacing the seawater in the sample chamber with a fixative solution (e.g., absolute ethanol or RNA-later). However, when a fluid-driven pump is used to inject the fixative into the chamber, the fixative tends to follow the path of least hydrodynamic resistance, often flowing directly toward the outlet. This results in very low mixing and displacement efficiency. To reach the effective concentration required for proper sample preservation, a large volume of fixative is usually needed, which is unfavorable for deep-sea sampling operations.

Mixing between different fluids primarily relies on molecular diffusion [

11]. To enhance mixing efficiency, various mixer structures have been proposed. Mixers are generally categorized as active or passive based on external energy requirements. Although active mixers offer more precise control over fluids, their complex structures and potential interference from introduced energy fields pose challenges. In contrast, passive mixers utilize special channel geometries to achieve fluid mixing [

12] and have attracted widespread research interest due to their low cost, ease of integration [

13], and absence of external energy requirements.

The Tesla valve is a passive fluid rectification structure. When fluid flows in the reverse direction, part of the flow entering the main channel is diverted into the curved branched pipe. As the fluid turns sharply into the branched channel, it collides with the continuous inflow in the main channel, generating spatial counterflows, which induce turbulence and the formation of local vortices [

14]. Through momentum exchange of the flow streams in the confluence region, a highly turbulent flow field with multi-scale vortex structures is formed, effectively enhancing mixing between different fluids. Large-scale vortices continuously break into smaller ones, significantly increasing the contact area and mixing efficiency, extending residence time within the channel, and resulting in localized pressure loss. These effects collectively promote the uniform distribution of the fixative.

Numerous researchers have utilized Tesla valves to achieve efficient fluid mixing. For instance, Le et al. [

15] demonstrated a 3D microfluidic Tesla mixer with high mixing performance, attributed to additional vortex generation, as confirmed by Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations. Liu et al. [

16] proposed an Asymmetric Tesla Vortex Micro-mixer (ATVM) with baffles and systematically investigated its mixing mechanism and performance through a multi-physics coupled numerical model, focusing on the effects of baffle structure, height, and number on mixing efficiency, pressure drop, and energy consumption. Li et al. [

17] designed a novel Tesla micro-mixer (TSM) and used COMSOL simulation software to systematically study the influence of obstacle arrangement, geometry, and size on mixing performance. These studies demonstrate how the counterflow characteristics of the Tesla valve can disrupt typical laminar flow profiles at the microfluidic scale, enabling rapid, uniform mixing without external power-addressing a key engineering requirement for deep-sea in situ preservation technology.

In the present study, we propose a novel nucleic acid preservation device based on the counterflow mixing effect of the Tesla valve for effective in situ injection of nucleic acid stabilizers. We confirmed the fluid dynamics and designed the preservation structure using simulation modeling. Numerical simulations were employed to compare the fluid mixing process, residence time distribution, and reagent displacement efficiency between preservation chambers with and without the Tesla valve structure, supplemented by experimental validation of its actual mixing performance. Additionally, based on simulation results, the internal three-dimensional geometry was optimized, resulting in a set of design parameters for a deep-sea nucleic acid preservation device characterized by low sensitivity to inlet velocity, minimal fixative consumption, and high mixing efficiency.

2. Numerical Modeling and Mesh Independence Verification

2.1. Geometric Configuration

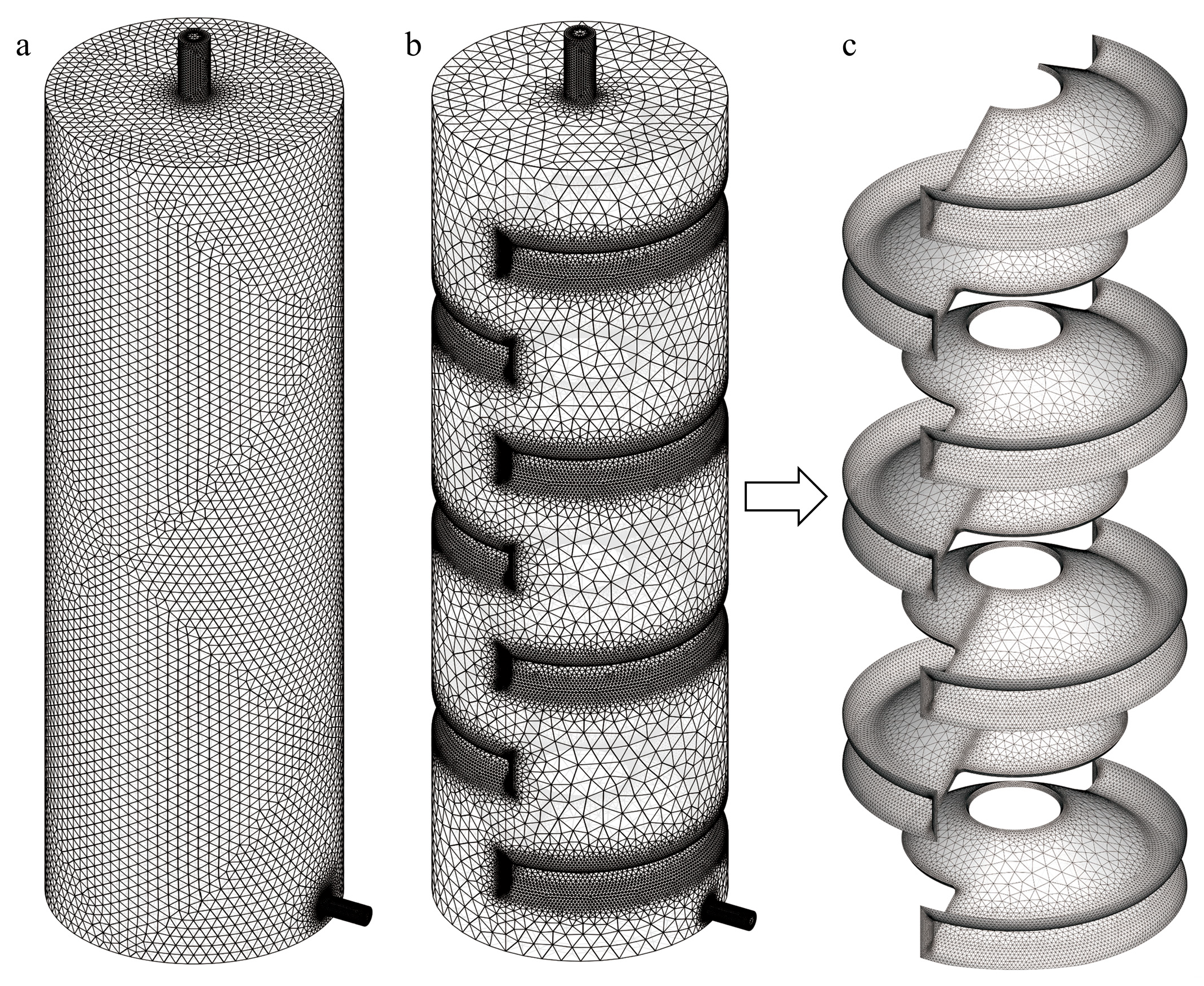

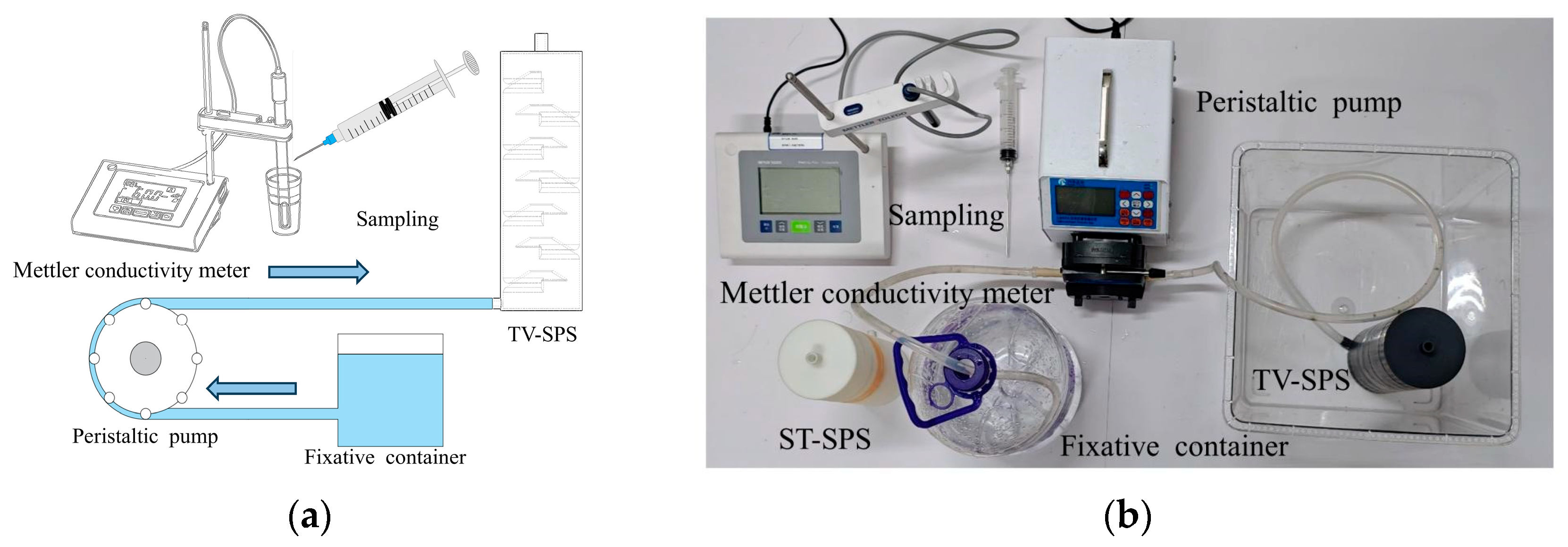

A novel deep-sea nucleic acid preservation structure was designed. Comparative analyses were conducted between this new design and a conventional straight-tube nucleic acid sample preservation structure (ST-SPS,

Figure 1a). The new structure features an annular baffle that induces passive fluid mixing through a Tesla-valve-inspired geometry, and is accordingly designated as the Tesla-valve-based sample preservation structure (TV-SPS,

Figure 1d).

The fluid domains of both the ST-SPS and TV-SPS chambers were extracted for subsequent simulation and analysis. Central cross-sectional views were defined to clearly illustrate the geometric features of each model (

Figure 1b,e).

In the central cross-sectional view, the conventional ST-SPS adopts a cylindrical configuration with an overall height of 230 mm and a primary body diameter of 75 mm. The bottom inlet has a length of 13 mm, a diameter of 5 mm, and is located 4 mm above the base wall. The top outlet, coaxially aligned with the structure axis, has a length of 16 mm and a diameter of 8 mm (

Figure 1c). This rotationally symmetric design yields a chamber volume of 1.01 L.

The novel TV-SPS preserves the inlet/outlet dimensions and overall chamber geometry of the conventional ST-SPS while integrating seven annular baffles within its main body. Each baffle is oriented at 60° relative to the vertical wall plane and incorporates 5 mm chamfers at the chamber–wall interfaces, thereby emulating the energy dissipation characteristics of Tesla valve counterflow channels (

Figure 1f). The first baffle is positioned 34 mm above the bottom wall, with subsequent baffles spaced 30 mm axially and having a thickness of 1.2 mm (

Figure 1f). Each baffle contains a coaxial aperture with a diameter of 21 mm, and the radial distances from the aperture edge to the outer contour of the annular baffle are 14 mm and 27 mm (

Figure 1f). This geometric configuration minimizes the spatial footprint of the baffles, resulting in a chamber volume of 0.98 L for the TV-SPS-only 0.03 L less than that of the conventional design (1.01 L). Given the marginal volumetric difference (<3%), the reduction was deemed negligible in subsequent comparative analyses of fixative consumption.

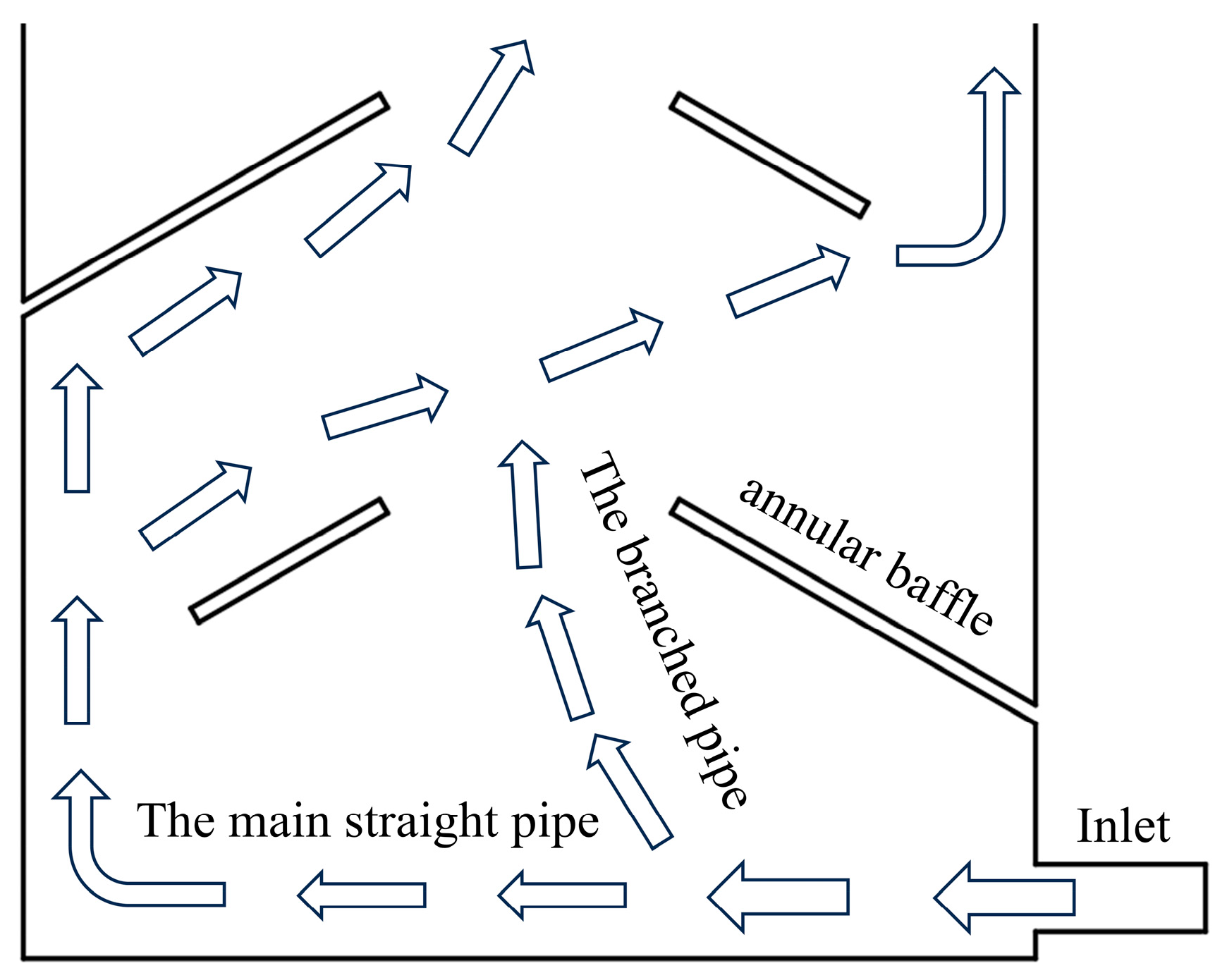

As the fixative flows through the precisely arranged baffles within the structure, its path is effectively directed, forcing a portion of the fluid to form a reverse flow opposite to the main flow direction, as shown in

Figure 2. This design successfully reproduces the reverse-flow operating principle of the Tesla valve. When the two fluid streams converge in the mixing zone, their interaction triggers the formation of multi-scale vortex structures. These vortices not only enhance momentum exchange between the fluid streams but also, by intensifying the mixing effect, establish a solid hydrodynamic foundation for highly efficient mixing. The overall design inherits the core working mechanism of the Tesla valve-guiding the fluid to generate reverse flow and vortices for enhanced mixing-while ensuring that the inherent hydrodynamic advantages are preserved when applied in structurally compact integrated devices.

2.2. Governing Equations

During the initial operational phase of the deep-sea biological in situ preservation structure, deep-sea nucleic acid samples are retained within a chamber pre-filled with in situ seawater. Fixative agents are pumped into the preservation cavity through the bottom inlet, thoroughly mixed with the seawater within the chamber, and then discharged through the coaxial top outlet.

Numerical simulations were performed on two deep-sea nucleic acid preservation structures using ANSYS Fluent 16.0. The mixing and transport behavior between fixatives and seawater under varying inflow velocities were systematically investigated. To analyze the dynamic consumption process of the fixative while avoiding the high cost of RNA-later, a seawater–water two-phase flow model was first established, using water as a substitute fluid. The reliability of the simulation model was experimentally validated through comparison between empirical measurements and computational results. After verification, numerical simulations employing actual RNA-later fixative were carried out to determine optimal geometric parameters and critical flow velocity thresholds of the preservation structure.

Both seawater and fixative are incompressible fluids. The continuity equation is:

where

ρ is the fluid density (kg/m

3), and

ui denotes the fluid velocity component in the

i-th direction (m/s).

The momentum conservation equation is:

where

where

p denotes pressure (Pa);

μ represents dynamic viscosity (Pa·s);

μt is the turbulent viscosity (Pa·s);

δij is the Kronecker delta function (equal to 1 when

i =

j, and 0 otherwise);

gi is the gravitational acceleration, which is set to 9.81 m/s

2.

We use the Realizable

k-ε turbulence model [

18], whose turbulence kinetic energy equation is:

Turbulent dissipation rate equation is:

where

k is the turbulent kinetic energy (m

2/s

2);

μt denotes the turbulent viscosity (Pa·s);

σk represents the Prandtl number for turbulent kinetic energy;

Gk is the turbulent kinetic energy generation term;

ε indicates the turbulent dissipation rate (m

2/s

3);

σε stands for the Prandtl number of turbulent kinetic energy, set to 1.2 in this article;

C1 governs the “production term” of turbulent dissipation rate;

C2 is the turbulence model constant with a value of 1.92;

v refers to the kinematic viscosity (m

2/s).

Species transport equation:

where

ci is the mass fraction of fixative component

i;

Dim denotes the molecular diffusivity of fixative

i (taken as 1 × 10

−9 m

2/s in this study);

Sct represents the turbulent Schmidt number (set to the default value of 0.7);

S is the source term accounting for component generation or consumption, which is assigned a value of 0 in this article.

2.3. Boundary Conditions and Solver Settings

This study focuses on the internal fluid structure design and hydrodynamic validation of nucleic acid sample preservation structures, with an emphasis on comparing the relative performance of different configurations in guiding flow fields, generating vortices, and enhancing mixing efficiency. As a comparative investigation, its objective is to provide a basis for scheme selection rather than to predict the absolute performance of the structures under extreme environmental conditions. The study does not incorporate fluid–structure interaction analysis and is based on a key assumption that all fluid-solid interfaces are rigid and will not deform under deep-sea high-pressure conditions. From an engineering perspective, the mixer operates as an open flow system with both its inlet and outlet exposed to the ambient environment. This configuration ensures that the external hydrostatic pressure is balanced across both ends, establishing a uniform pressure environment within the chamber. As a result, the internal flow dynamics are governed exclusively by the inlet flow rate and remain independent of the external deep-sea pressure.

A velocity inlet boundary condition was set at the inlet, with three distinct flow regimes—low velocity (0.2 m/s), medium velocity (0.4 m/s), and high velocity (0.6 m/s), which were introduced through the bottom inlet into the preservation chamber. The outlet was configured as an outflow boundary, and all walls within the fluid domain were assigned no-slip boundary conditions.

Three fluid materials were involved in the simulations: seawater, purified water for model validation, and the target preservative RNA-later fixative. The key physical properties of these media adopted in the simulations are summarized in

Table 1. Furthermore, for simulation cases involving mixed components, the mixture model was employed, and the volume-weighted mixing law and mass-weighted mixing law were selected based on computational requirements to determine the equivalent physical parameters of the mixtures.

Based on the specified inlet conditions, the Reynolds numbers (

Re) for different fluid media at various inlet velocities were calculated, with the specific results summarized in

Table 2. The analysis reveals that at lower flow velocities, the Reynolds numbers for both fluid media generally fall within a low range. However, since the structure in this study is not a conventional straight circular pipe but features a complex internal geometry with significant flow path curvature and cross-sectional variations, the flow regime should not be simply classified as laminar based solely on Reynolds number.

Given the time-varying flow field in the fluid domain, a transient solver was selected for the simulation. The computations were performed with a time step of 0.1 s, and the residual convergence criteria for all equations were set to 10

−4. The time step was determined to ensure a CFL number below 1, thereby guaranteeing both convergence and accuracy of the solution. This study employs the Realizable

k-ε turbulence model [

18] with the standard wall Functions approach for near-wall treatment. Based on the law of conservation of components, a non-reactive species transport model was employed to solve for the variations in each component during the convective–diffusive process. Numerical configurations included: SIMPLE algorithm [

19,

20] is used for pressure velocity coupling; Flux correction using Rhie-Chow momentum interpolation; The gradient term in spatial discretization is calculated using the least squares method, and the pressure term is calculated using PRESTO [

20]. High-order interpolation; Momentum, turbulence parameters, and component equations are all presented in a second-order upwind format; Transient integration uses a second-order implicit scheme to ensure numerical stability.

The initial conditions consisted of seawater intended for displacement (mass fraction = 1 in the chamber) and fixative (mass fraction = 1 at the inlet). During the simulation, the mass fraction of the fixative within the chamber was monitored using a volume-averaging method and written to a file. A custom Scheme script was employed to track the recorded fixative mass fraction.

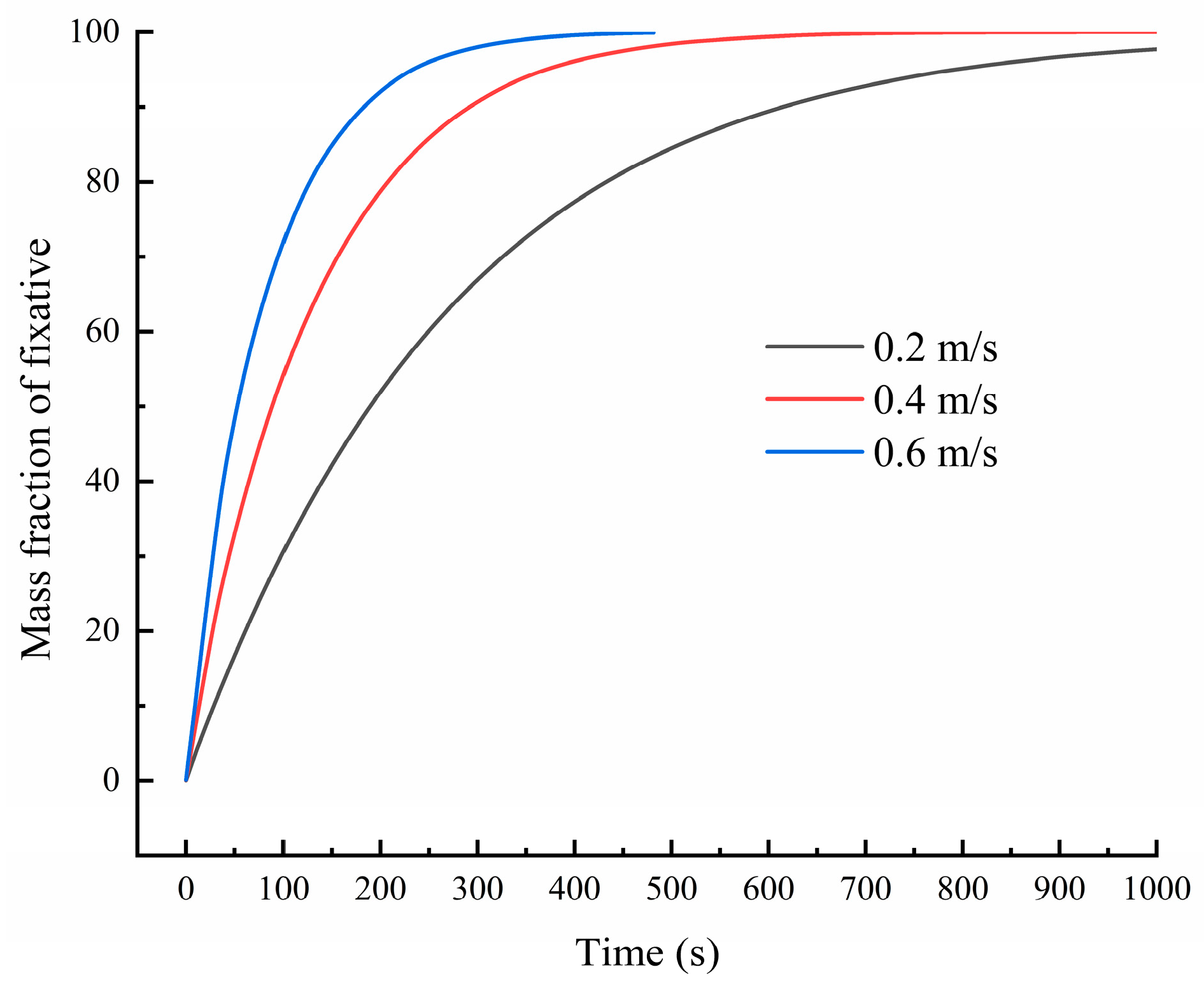

Figure 3 presents fixative mass fraction in the chamber varied with time at different inlet velocites.

The fixative consumption is determined by the inlet velocity, flow duration, and cross-sectional area, as expressed by Equation (7).

where

V is the consumed fixative volume (L);

D denotes the inlet diameter (set to 5 mm in this study);

v represents the inlet velocity; and

t denotes the computation time at which the fixative mass traction reaches the set value.

2.4. Mesh Generation and Grid Independence Verification

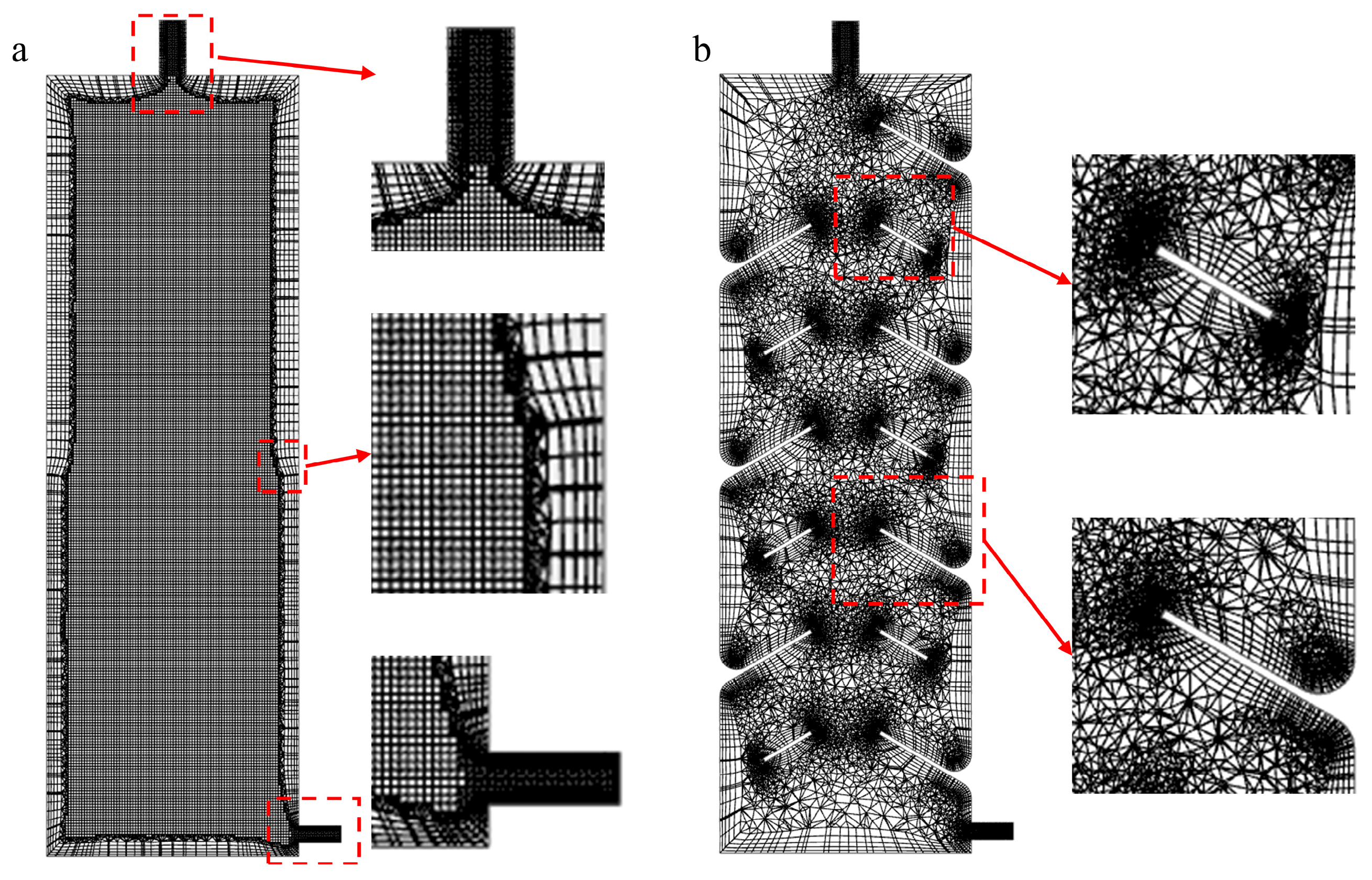

Due to the complex internal geometry of the TV-SPS, tetrahedral meshes were employed to effectively cover intricate regions while minimizing mesh distortion, achieving superior mesh quality. In contrast, the geometrically simple and regular ST-SPS enabled uniform hexahedral meshing, as shown in

Figure 4, resulting in higher computational accuracy and efficiency.

To meet the requirements of the standard wall functions (30 <

y+ < 300) for the

k-ε turbulence model, adequately thick boundary layer meshes were applied to both models. The specific meshing strategy was as follows: first, the flow field velocity was estimated based on the definition of

y+ (Equation (8)), and the computational domain was divided into multiple sub-regions with distinct characteristic velocities; then, the size of the first layer of mesh at the wall was specified, with growth across five layers to ensure a smooth transition. Boundary layer meshes of varying thickness were applied to the walls in each sub-region, as shown in

Figure 5.

where

y: The physical distance from the center of the first grid cell to the wall (m).

uτ: Friction velocity (m/s), an inherent characteristic velocity of the flow field.

ν: Kinematic viscosity (m2/s).

To ensure wall

y+ values predominantly remained within the valid range, mesh element sizing, growth rates, and total grid counts were rigorously controlled, as shown in

Table 3. Mesh independence verification was conducted at

v = 0.2 m/s, with solver settings, fluid properties, and boundary conditions consistent with prior descriptions.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the chamber volume mesh and boundary layer: (a) ST-SPS; (b) TV-SPS.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the chamber volume mesh and boundary layer: (a) ST-SPS; (b) TV-SPS.

The reliability of the numerical simulation results was systematically evaluated through grid independence verification. During this process, the fixative consumption-measured when the mass fraction of the fixative in the chamber reached 87.2% (corresponding to a seawater-to-fixative volume ratio of 1:7) was used as the key metric. The relative errors of the simulation results across different grid scales were compared and analyzed, with the finer grid solution taken as the reference value. To further quantify numerical uncertainty, a rigorous grid sensitivity assessment was carried out using the Grid Convergence Index (GCI) method, thereby ensuring that the grid resolution employed in subsequent analyses fully meets computational accuracy requirements, as shown in

Table 3.

Through an in-depth analysis of the GCI, a more systematic evaluation of grid sensitivity in numerical simulations can be conducted. In the analysis of the ST-SPS structure, although the relative error between Case 2 and Case 3 decreased to 1.95%, the corresponding GCI was as high as 58.04%, indicating that the solution under this grid configuration still exhibited considerable uncertainty and had not yet reached a stable convergence state. However, when the grid was further refined to Case 4, the relative error between Case 3 and Case 4 was only 0.05%, and the GCI significantly dropped to 0.20%, demonstrating that the numerical solution had stabilized at this point. Therefore, after a balanced consideration of convergence and computational cost, Case 3 was selected as the final grid scheme for the ST-SPS structure.

In the TV-SPS structure, the grid convergence trend was more consistent. From Case 5 to Case 8, the GCI value progressively decreased from 21.13% to 3.00%, indicating that the numerical solution gradually approached the theoretical value as the grid was refined. Although the relative error between Case 6 and Case 7 was only 3.94%, the GCI remained at 9.56%, suggesting that the results at this stage still contained some uncertainty. However, when comparing Case 7 and Case 8, the relative error was only 0.52%, and the GCI further decreased to 3.00%, indicating that the grid solution had essentially converged based on Case 7. Thus, Case 7 was chosen as the representative configuration for the TV-SPS structure, ensuring a certain level of accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency.

4. RNA-Later Fixative-Based Numerical Simulations

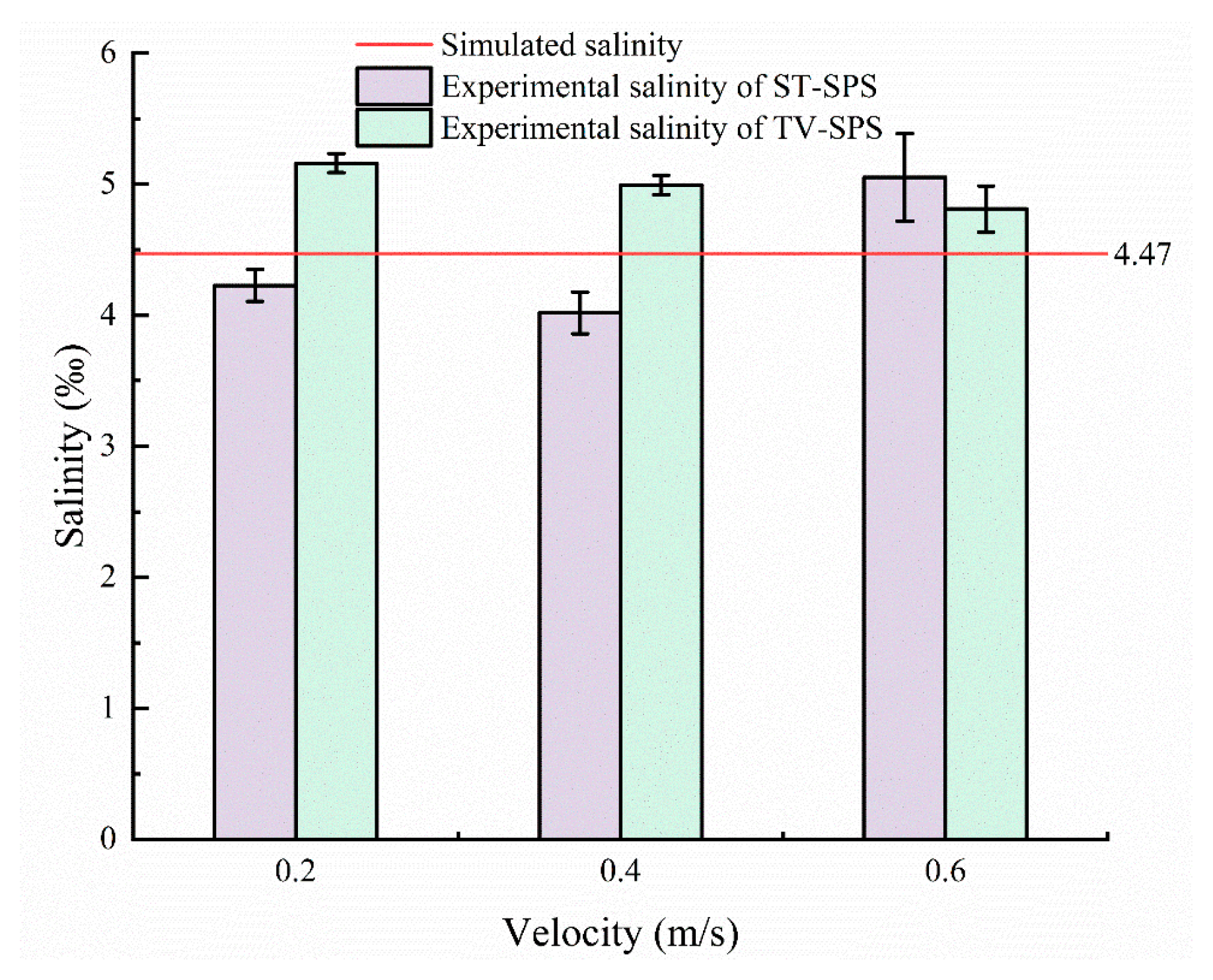

Based on the simulation model validated through the seawater–pure water exchange process, further simulations were conducted to compare the ST-SPS and the TV-SPS. Using RNA-later as the fixative, the simulations assessed the volume of fixative required to achieve the same volumetric concentration (87.2%) under varying inlet velocities.

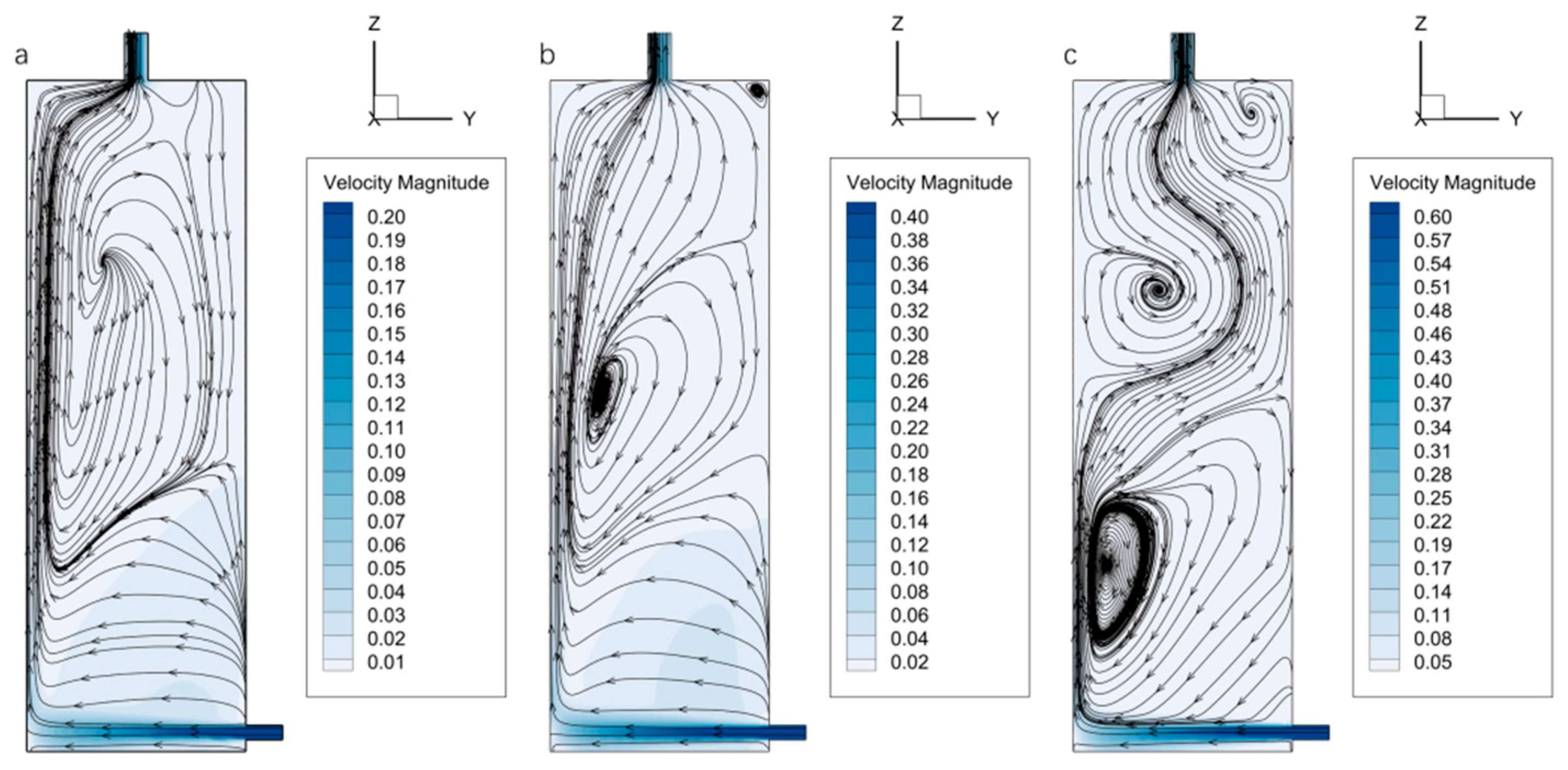

The velocity distribution within the ST-SPS chamber exhibits similar patterns across different inlet velocities. The central region of the chamber maintains a relatively low velocity, while a localized high-velocity jet forms near the inlet due to the diameter constraint. Upon entering the chamber expansion, a small portion of the RNA-later fixative moves along the positive

z-axis, whereas the majority impinges on the left inner wall of the ST-SPS preservation chamber and splits into two streams, one moving upward and the other downward, as illustrated in

Figure 8. Since the inlet is located near the bottom, most of the fixative flows upward along the left wall and is eventually discharged through the top outlet.

The streamlines exhibit a regular pattern without the formation of complete vortices at

v = 0.2 m/s. As shown in

Figure 8a, the streamlines are densely distributed along the left wall. While on the right wall, fluid renewal is delayed due to viscous effects, thereby reducing the overall efficiency of mass exchange. Although the flow remains stable under this condition, transverse convection of the fixative is weak, requiring 574 s to reach a mass fraction of 87.2%. This indicates relatively poor mixing and mass transfer performance. When the inlet velocity increases to 0.4 m/s, enhanced shear forces and steeper velocity gradients trigger Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities, leading to flow separation and the formation of large-scale vortices (

Figure 8b). These vortices extend the residence time of the fixative and promote mixing with seawater, significantly improving convective mass transfer efficiency. The time required to reach the same mass fraction is reduced to 202 s. The vortex structures become more complex and numerous at

v = 0.6 m/s. Increased turbulent kinetic energy further amplifies the velocity gradients, substantially enhancing the mass exchange rate, with the corresponding time reduced to 159 s. Streamlines in the upper region of the preservation chamber shift from the left to the right side, thereby improving the overall flow uniformity within the structure, as illustrated in

Figure 8c.

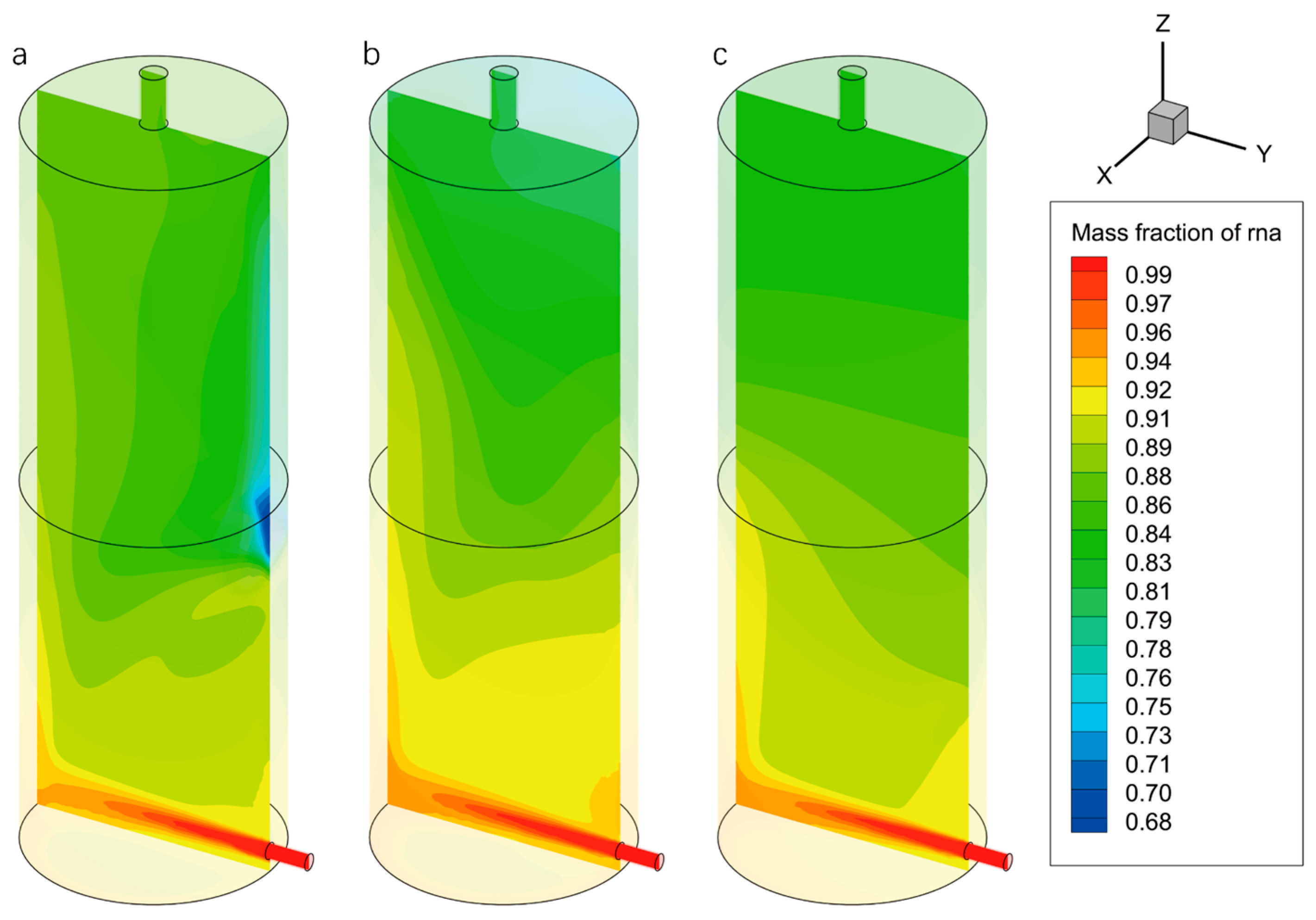

Figure 9 illustrates the mass fraction contours of the fixative within the chamber of the nucleic acid sample preservation structure at the automatic termination time. A higher concentration region appears at the bottom of the chamber with a pronounced concentration gradient at

v = 0.2 m/s. Additionally, the fixative concentration on the left side is noticeably higher than that on the right in the upper and middle regions of the chamber. At the same time, a distinct low-concentration zone appears at the mid-right wall on the same side as the inlet (

Figure 9a). This distribution aligns with the previously analyzed velocity and streamlines fields, indicating weak transverse convective diffusion at

v = 0.2 m/s, which results in localized nonuniformity in fixative concentration. When the inlet velocity increases to 0.4 m/s, the uniformity of the fixative mass fraction distribution improves significantly, especially in the lower part of the chamber, where the concentration gradient becomes more gradual (

Figure 9b). The previously observed low-concentration zone disappears entirely. Flow field analysis reveals that the formation of large-scale vortex structures significantly enhances convective mass transfer, thereby promoting more effective exchange between the fixative and seawater. Although minor local concentration differences persist, the increased shear force at the higher inlet velocity substantially reduces the time required to reach a steady state. Notably, when the inlet velocity is further increased to 0.6 m/s, the uniformity of the fixative distribution at the chamber bottom declines compared to the 0.4 m/s case, with steep concentration gradients reemerging in the lower region, while the upper region remains uniformly distributed (

Figure 9c). This is attributed to the increased number of vortex structures and higher turbulent kinetic energy caused by excessive inlet velocity. Although these factors intensify convection and accelerate mass exchange rates, they also introduce a certain degree of negative impact on the overall uniformity of fixative distribution.

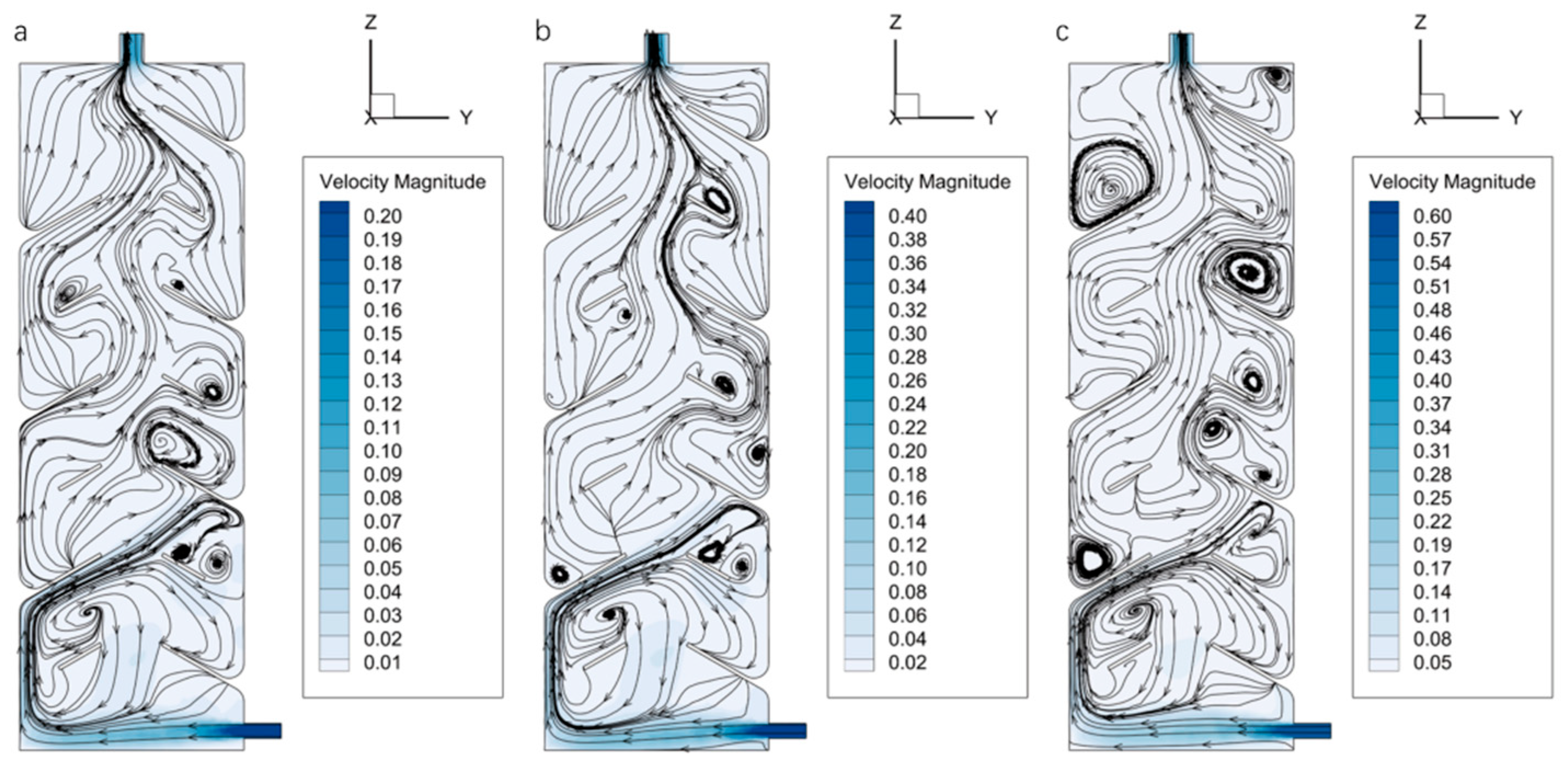

Further investigation was conducted on the internal flow field, mass fraction distribution, and fixative consumption of the TV-SPS using RNA-later as the fixative under different inlet velocities. As shown in the velocity contours of

Figure 10, most of the fixative flows along the baffles rather than along the left wall toward the outlet in the ST-SPS, undergoing a more complex mass exchange process. The streamline distribution in

Figure 10a clearly illustrates that multiple localized vortices are formed within the chamber even at

v = 0.2 m/s. The recirculation zones behind the annular baffles contribute to increasing the residence time of the fixative in the chamber. However, due to the overall low flow velocity, it takes 293 s for the RNA-Later fixative to reach a mass fraction of 87.2%. At

v = 0.4 m/s, the fluid shear effect is significantly enhanced, and Kelvin-Helmholtz instability leads to flow separation and the formation of a greater number of small-scale vortices behind the annular baffles, as shown in

Figure 10b. This enhances mixing and reduces the time required to reach the target mass fraction to 138 s. When the velocity increases to 0.6 m/s, even more and larger vortices appear around the annular baffles. These vortices further promote the exchange of momentum, mass, and energy between fluid elements, thereby accelerating the mixing process and reducing the required time to 95 s.

At all three inlet velocities, the TV-SPS exhibits a significantly different fixative mass fraction distribution characteristic compared to the ST-SPS: high-concentration regions are primarily located in the lower chamber of the TV-SPS, as shown in

Figure 11. Despite the differences in inlet velocity, the concentration distributions in the TV-SPS remain relatively consistent across the three cases. This is primarily attributed to the presence of annular baffles, which induce vortex formation at all tested velocities. These small-scale vortices effectively enhance mixing, leading to a more uniform axial distribution of the fixative mass fraction.

The variation in inlet velocity mainly influences the spatial extent of the medium- to high-concentration regions within the chamber. Due to the configuration of the annular baffles, the fixative is difficult to exchange with the seawater located near the upper two baffles. As a result, seawater tends to accumulate in the upper portion of the chamber, forming a low-concentration fixative zone. Notably, even at the highest inlet velocity of 0.6 m/s, the fixative mass fraction in the upper low-concentration region remains around 30%, as illustrated in

Figure 11c.

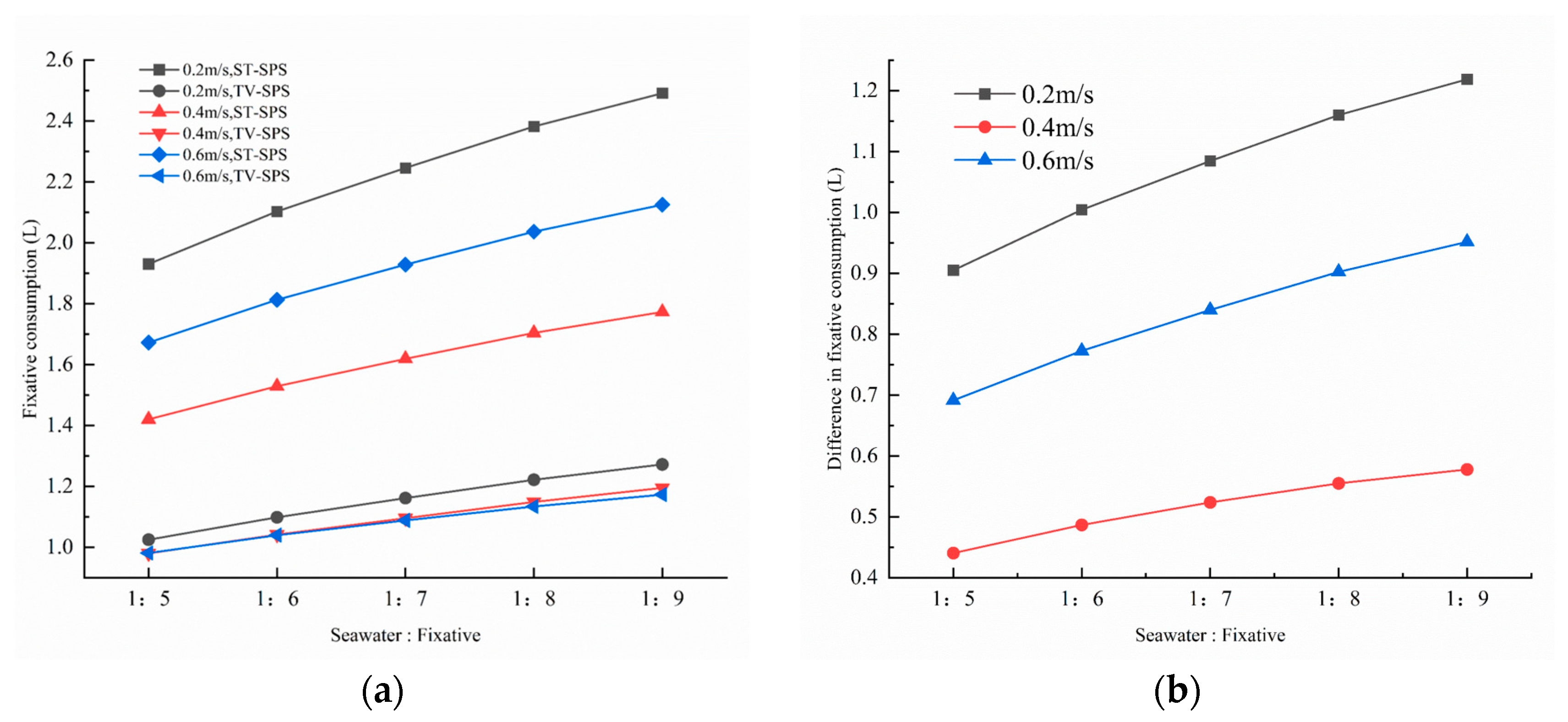

Further analysis was conducted to compare the fixative consumption under different volume ratios of seawater to fixative, as shown in

Figure 12. The higher the ratio of the fixative mass fraction, the more consumption of the fixative. The results indicate that the TV-SPS exhibits a pronounced advantage in fixative utilization efficiency; its fixative consumption is much smaller than that of the ST-SPS, with its consumption remaining relatively stable across varying inlet velocities. In contrast, the ST-SPS shows notable fluctuations in fixative consumption with changing inlet velocities, with the minimum consumption consistently observed at 0.4 m/s across all volume ratios.

Under the volume ratio of seawater to fixative equals 1:5, which corresponds to the minimum fixative consumption for all inlet velocities, the TV-SPS achieves a 44.95% reduction in fixative consumption compared to the ST-SPS (TV-SPS: 1.42 L vs. ST-SPS: 0.98 L), as illustrated in

Figure 12a. This improvement can be attributed to the incorporation of annular baffles, which effectively prolong the residence time of the fixative within the chamber and enhance mass transfer efficiency.

Under the 1:7 condition, the TV-SPS maintains significantly lower and more stable consumption across all velocities compared to the ST-SPS. Specifically, the TV-SPS reduces fixative consumption by 48.9% at

v = 0.2 m/s (from 2.25 L to 1.15 L), by 32.5% at

v = 0.4 m/s (TV-SPS: 1.08 L vs. ST-SPS: 1.61 L), and by 39.9% at

v = 0.6 m/s (1.12 L vs. 1.87 L), as shown in

Figure 12b. Under the 1:9 condition, the TV-SPS reduces fixative usage by 48.9% at

v = 0.2 m/s (from 2.49 L to 1.27 L), by 35.6% at

v = 0.4 m/s (1.77 L vs. 1.20 L), and by 44.8% at

v = 0.6 m/s (2.13 L vs. 1.17 L). The absolute saving reaches up to 1.22 L at

v = 0.2 m/s, highlighting the efficiency of the TV-SPS in reducing fixative demand even under higher dilution ratios.

Across the three volume ratios, a consistent trend is observed: the TV-SPS achieves pronounced savings over the ST-SPS, with the magnitude of reduction varying with both dilution ratio and inlet velocity. The highest relative savings are achieved at the lowest velocity (0.2 m/s), whereas the lowest absolute consumption occurs at 0.4 m/s. The gradual decrease in relative savings with increasing velocity can be attributed to enhanced convective diffusion, which promotes more uniform fixative distribution in both systems. Nonetheless, the TV-SPS maintains a substantial reduction in consumption across all flow conditions, underscoring its reliability and efficiency for optimizing fixative utilization in mass transfer processes.

5. Preservation Structure Design Optimization

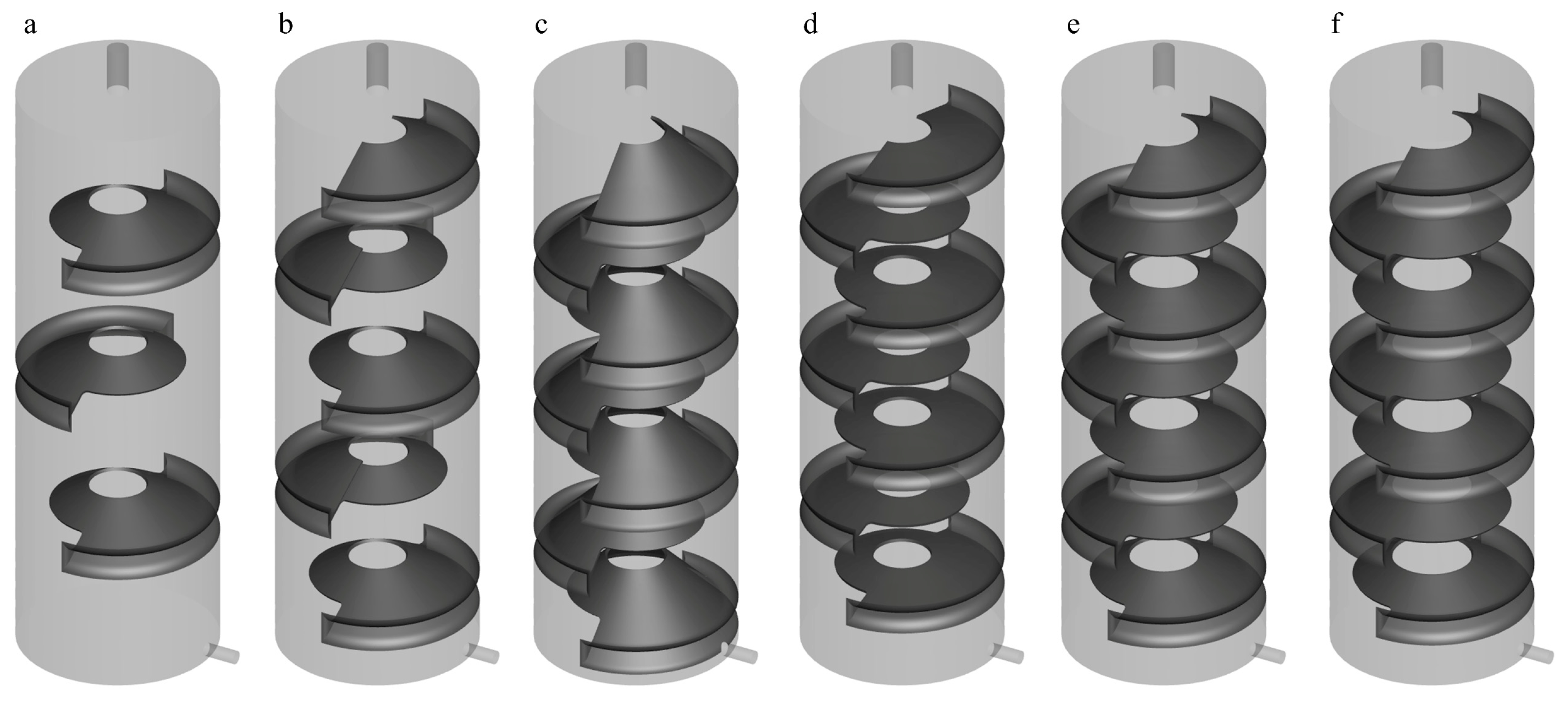

Studies have shown that the performance of the Tesla valve, as a passive, no-moving-part unidirectional valve, mainly relies on the optimization of its geometric design parameters. Based on the advantages of the current TV-SPS in significantly reducing fixative consumption, a systematic investigation was conducted focusing on the effects of annular baffle quantity, baffle inclination angle, and central aperture diameter.

For baffle quantity optimization, configurations with 3 and 5 baffles were examined (

Figure 13a,b), as the original 7-baffle design would encounter geometric interference if increased to 9 baffles. For inclination angle optimization, the baffle angles were adjusted to 45° and 75° (

Figure 13c,d), whereas the angle in

Figure 1 is 60°. Regarding the central aperture diameter, a critical parameter influencing the flow cross-section of the fixative, two sizes, 25 mm and 29 mm, were tested (

Figure 13e,f). Numerical simulations were conducted to comprehensively assess the impact of these geometric variations on the flow field structure and mass transfer efficiency.

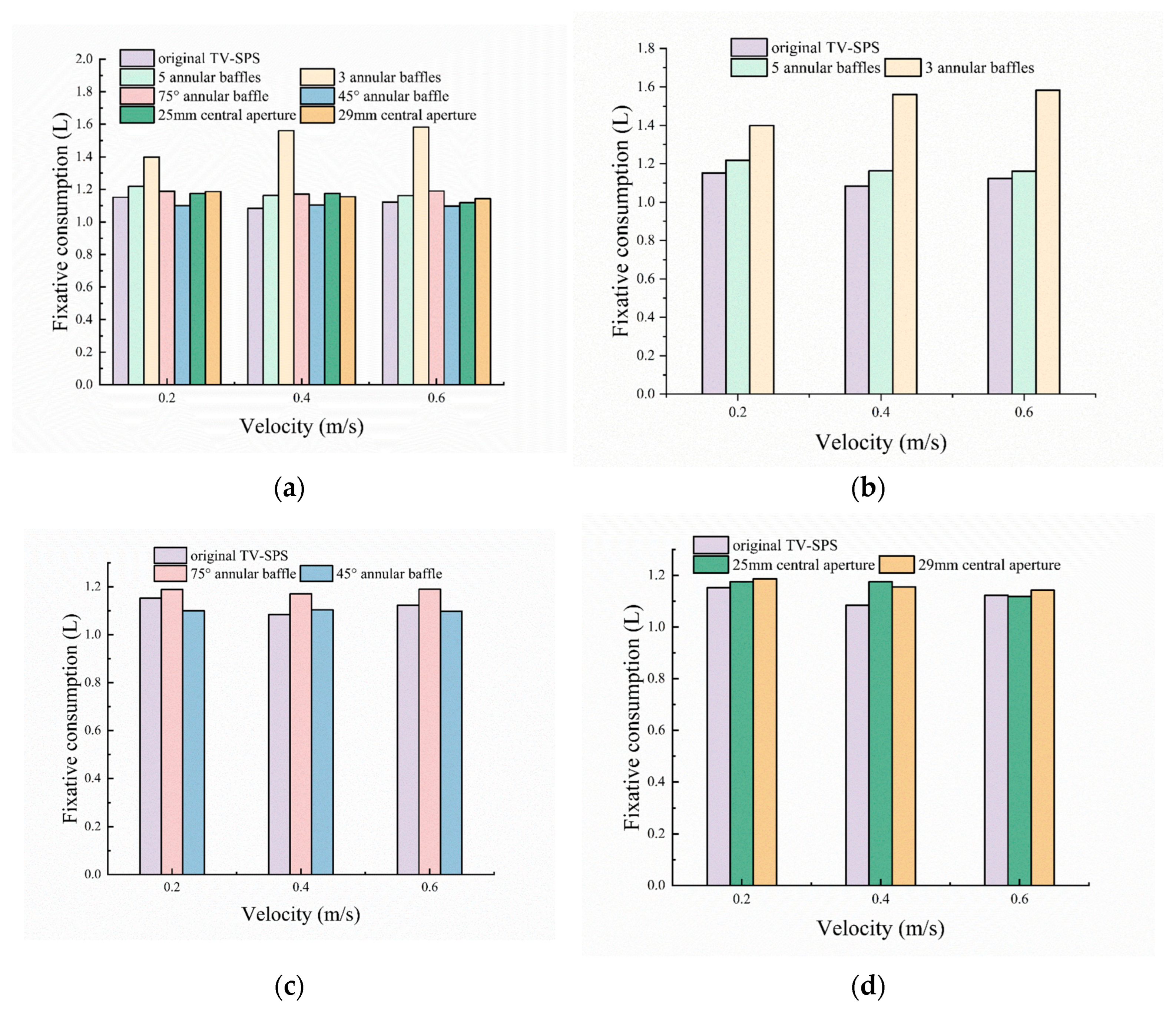

The numerical results show that, except for a significant increase in fixative consumption when the number of annular baffles is reduced to 3, other structural modifications have only minor effects on fixative usage, suggesting that the current design is close to optimal (

Figure 14a). When the number of baffles is reduced to 3 or 5, the consumption of fixative increases slightly at all inlet velocities. For instance, the three-baffle configuration results in a fixative consumption of 1.58 L at

v = 0.6 m/s, which is still 15.24% lower than that of the ST-SPS (

Figure 14b).

Adjusting the baffle inclination angle to 45° and 75° yields fixative consumption of 1.10 L and 1.17 L at

v = 0.6 m/s, respectively. Overall, baffle inclination angle has a limited effect on fixative consumption, with reductions of 41.20% and 36.28% compared to the ST-SPS, and only slight deviations from the 1.15 L used by the original TV-SPS. Notably, the 45° baffle structure exhibits low sensitivity to inlet velocity variations, maintaining stable fixative consumption across the 0.2–0.6 m/s range (

Figure 14c).

The central aperture diameter (25 mm and 29 mm) also shows a limited influence. The fixative consumption for these configurations is 1.12 L and 1.14 L at

v = 0.6 m/s, respectively, with minimal fluctuation across inlet velocities (

Figure 14d). Nevertheless, they still achieve reductions of 40.13% and 38.80% compared to the ST-SPS, indicating that aperture size has a relatively small effect on enhancing mass transfer.

In summary, the 45° baffle is the most effective structure for reducing fixative consumption in the flow velocity range of 0.2–0.6 m/s, while the original TV-SPS performs best at 0.4 m/s.

6. Conclusions

This study develops a nucleic acid fixation and preservation structure for deep-sea benthic organisms based on the Tesla valve principle, aiming to reduce fixative consumption and enhance its utilization efficiency.

Through a comparative analysis of experimental results and numerical simulations, the Tesla-valve-based nucleic acid sample preservation structure demonstrates a significant reduction in fixative consumption compared to the traditional straight-tube design, while achieving the same fixative concentration. Specifically, the novel structure reduces fixative usage by 48.9% under the 1:7 condition at an inlet velocity of 0.2 m/s. The minimum fixative consumption is achieved under the 1:5 condition at 0.4 m/s (0.98 L). In addition, the fixative consumption of the TV-SPS shows relative insensitivity to variations in inlet velocity, as the consumption curves at 0.4 m/s and 0.6 m/s nearly overlap, underscoring its stability across different flow conditions.

Further investigations were conducted on the effects of annular baffle quantity, inclination angle, and central aperture diameter. Numerical simulation results showed that reducing the number of annular baffles from seven to three led to a significant increase in fixative consumption across all inlet velocities. When reduced to five baffles, the consumption of fixatives also increased slightly. With the baffle number maintained at seven, variations in inclination angle and aperture diameter had no significant impact on the consumption of fixative. Notably, an inclination angle of 45° consistently resulted in relatively low and stable fixative consumption under different inlet velocities. These findings suggest that the current design of the deep-sea nucleic acid sample preservation structure is already well-optimized.

The novel deep-sea nucleic acid sample preservation structure based on the Tesla valve principle enables effective in situ fixation of biological nucleic acid samples while significantly reducing fixative consumption. Its design offers improved compatibility with pump flow rate settings and fixative preparation, providing essential technical support for deep-sea biological research.