Digital Twin Framework for Predictive Simulation and Decision Support in Ship Damage Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

2.1. Digital Twin and Related Concepts: A Clarification

2.2. Recent Advances in Digital-Twin Applications for Shipboard Damage Control

2.3. Challenges and Limitations of Current Research

- (1)

- Insufficient access and fusion of multi-source heterogeneous data. Multi-modal data from sensors, subsystems, and historical cases lack unified specifications in terms of sampling frequency, quality control, semantic consistency, and spatiotemporal registration. Uncertainty characterization, data incompleteness, and low reliability weaken the effectiveness of online calibration and decision update of the DT model, increasing the cost of cross-scenario adaptation.

- (2)

- Lack of multiphysics field coupling mechanisms. Most current achievements are “point-like” breakthroughs, focusing either on water ingress processes or fire and smoke monitoring. There is still a lack of a high-fidelity unified model that can simultaneously characterize the coupled evolution of multi-fields such as breach water ingress, in-cabin fires, and smoke diffusion. The isolation and fragmentation among models limit the ability to characterize and map complex DC scenarios.

- (3)

- Weak closed-loop decision-making and control, as well as human–machine collaboration. Many studies stop at “monitoring–alarming” or “deduction–display”, and no mechanism has been formed to safely and controllably close the loop from virtual-space decisions to onboard actuators such as pumps and valves. Meanwhile, there is a lack of quantitative evidence and strategy design for “human-in-the-loop” collaborative decision-making (e.g., trust calibration, authority switching, intervention triggering) and an evaluation framework supported by standardized indicators and near-real-ship tests. Specifically, the evaluation should report standardized indicators such as operator intervention time, decision accuracy, and subjective trust ratings; where appropriate, these can be complemented by established human-automation interaction (HAI) measures—situational awareness (Situation Awareness Global Assessment Technique, SAGAT; Situation Awareness Rating Technique, SART), workload (NASA Task Load Index, NASA-TLX)—and Levels of Automation (LOA)–based interaction parameters (authority allocation, handoff latency, override rate).

- (4)

- Imperfect verification and calibration system. Insufficient standardized benchmark scenarios and evaluation protocols, limited access to real-ship/near-real-ship data, and an incomplete C-V-V process for parameters and boundary conditions make it difficult to form comparable and reproducible empirical results, affecting the credibility and transferability of engineering applications.

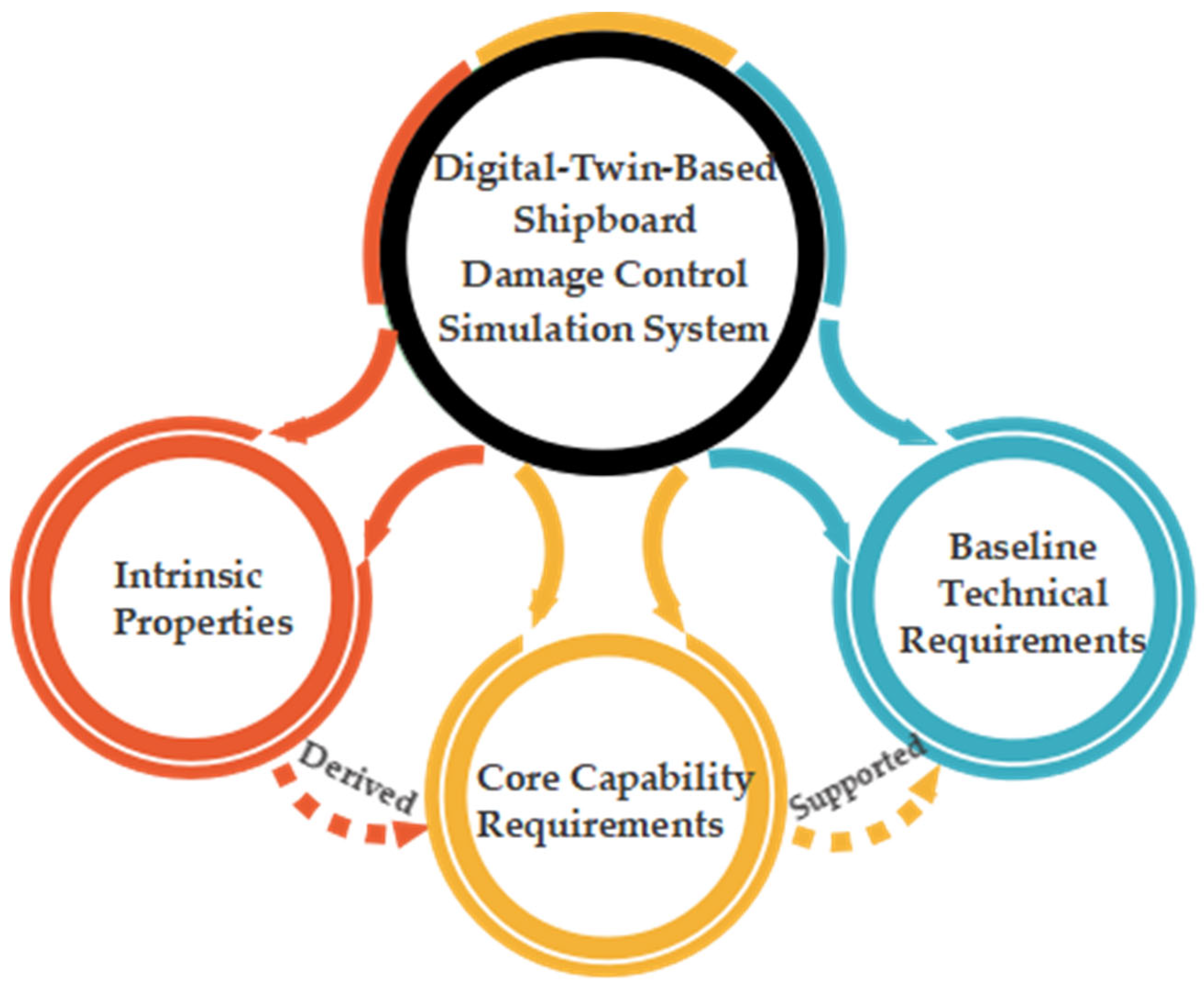

3. Properties and Core Requirements

3.1. Intrinsic Properties

- (1)

- Strongly coupled multiphysics: Represents hull-breach flooding, compartment fires, and smoke dispersion with their interactions (e.g., trim/heel effects on spread pathways), employing numerical acceleration and model-reduction techniques (e.g., reduced-order and surrogate models) to preserve physical consistency and achieve timeliness. Timeliness is quantified by the real-time factor (RTF = simulated duration/wall-clock time; target RTF > 1), and computational cost is evaluated by per-step runtime and peak memory usage. Evaluation is conducted via RTF (>1 target) and error relative to high-fidelity Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD).

- (2)

- Human-in-the-loop decision primacy: DC operates in a human-in-the-loop regime. The HMI provides one-click override/abort, a mode switch (manual/assist/autonomy), and bounded parameter sliders with reset. The operating doctrine is “assist by default”: the AI suggests, and the human approves/executes; in autonomy, the human may preempt at any time. Evaluation is based on operator-intervention frequency, decision-correction rate, and task-completion time across manual/autonomy/assist on the same tasks.

- (3)

- Cross-subsystem interdependence: DC effectiveness is constrained by propulsion, power, ventilation, and piping states; the system should interoperate with key shipboard subsystems for data exchange and coordinated control. Evaluation by comparing outcomes (e.g., time to control fires, heel angle) to verify interoperability.

3.2. Core Capability Requirements

- (1)

- Fast multi-hazard evolution simulation. Provide near-real-time predictions for three core hazard states—flooding rate, fire extent, and smoke concentration—with a user-facing latency budget ≤ 3 s. For situational awareness, aim to refresh mapped fire-spread boundaries at an interval ≤ 2 s, and accompany smoke concentration with rolling 5 min trend forecasts to support planning.

- (2)

- Scheme generation and collaborative optimization. Under declared resource constraints, generate and rank 2–3 executable DC action sequences within the response-time budget; revise plans when trigger conditions are met (e.g., flooding rate > 0.5 m3/s). The HMI provides auditable rationale (key-parameter impact) and editable constraints. The end-to-end decision pathway (from fused frame to final command set) has a budget ≤ 5 s (solver ≤ 2 s; plan generation/ranking ≤ 3 s).

- (3)

- Cyber-physical closed loop and feedback. Dispatch device/actuator commands (pumps, valves, ventilation, compartmentalization) with dispatch-to-acknowledgment latency ≤ 2 s. Adopt a 5-min online calibration policy that updates model parameters/boundaries using feedback; the performance objective is a ≥ 10% median reduction per calibration cycle in the relevant prediction error under comparable conditions (this value is an engineering acceptance target, not a measured result in this study).

3.3. Baseline Technical Requirements

- (1)

- Multi-source sensing and data fusion: Deploy pressure, temperature, smoke concentration, and attitude sensors to achieve 5–10 Hz sampling; perform time alignment, semantic harmonization, denoising, quality control, and uncertainty characterization; and fuse at the state layer with propulsion and navigation to form stable, coherent observations.

- (2)

- Unified multiphysics modeling and C-V-V: Build a unified model that simultaneously captures breach flooding, compartment fire dynamics, and smoke dispersion, with explicit error budgets and applicability; provide parameterized interfaces supporting the C-V-V process and model versioning.

- (3)

- Human–machine collaboration and explainable decisions: Design task-oriented interactions and information presentation with explicit constraints and assumptions; support human intervention, trace-back, and audit; and evaluate collaboration via efficiency, accuracy, and workload to ensure safe, controllable human-in-the-loop operation.

- (4)

- Standardized data/control interfaces and protocols: Provide hierarchical standardized interfaces and protocols for functional adaptation—Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture (OPC UA) for data interaction (supporting bidirectional mapping of multi-source heterogeneous data to ensure the integrity of simulation-model and equipment-status data), Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) for real-time control-command delivery (configured with Quality of Service (QoS) level 1/2 to prevent command loss for equipment such as pumps and valves, with end-to-end latency from command dispatch to execution acknowledgment ≤ 2 s), and the National Marine Electronics Association 2000 (NMEA 2000) maritime standard for shipboard hardware access (e.g., attitude sensors, pump controllers; based on the Controller Area Network (CAN) bus). Through these interfaces and protocols, end-to-end traceability is achieved, covering command dispatch, execution acknowledgment, and telemetry readback; meanwhile, hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing and multi-scenario validation are supported to ensure digital-physical state consistency and operational-safety bounds.

4. System Architecture, Maturity Model, and Core Technologies

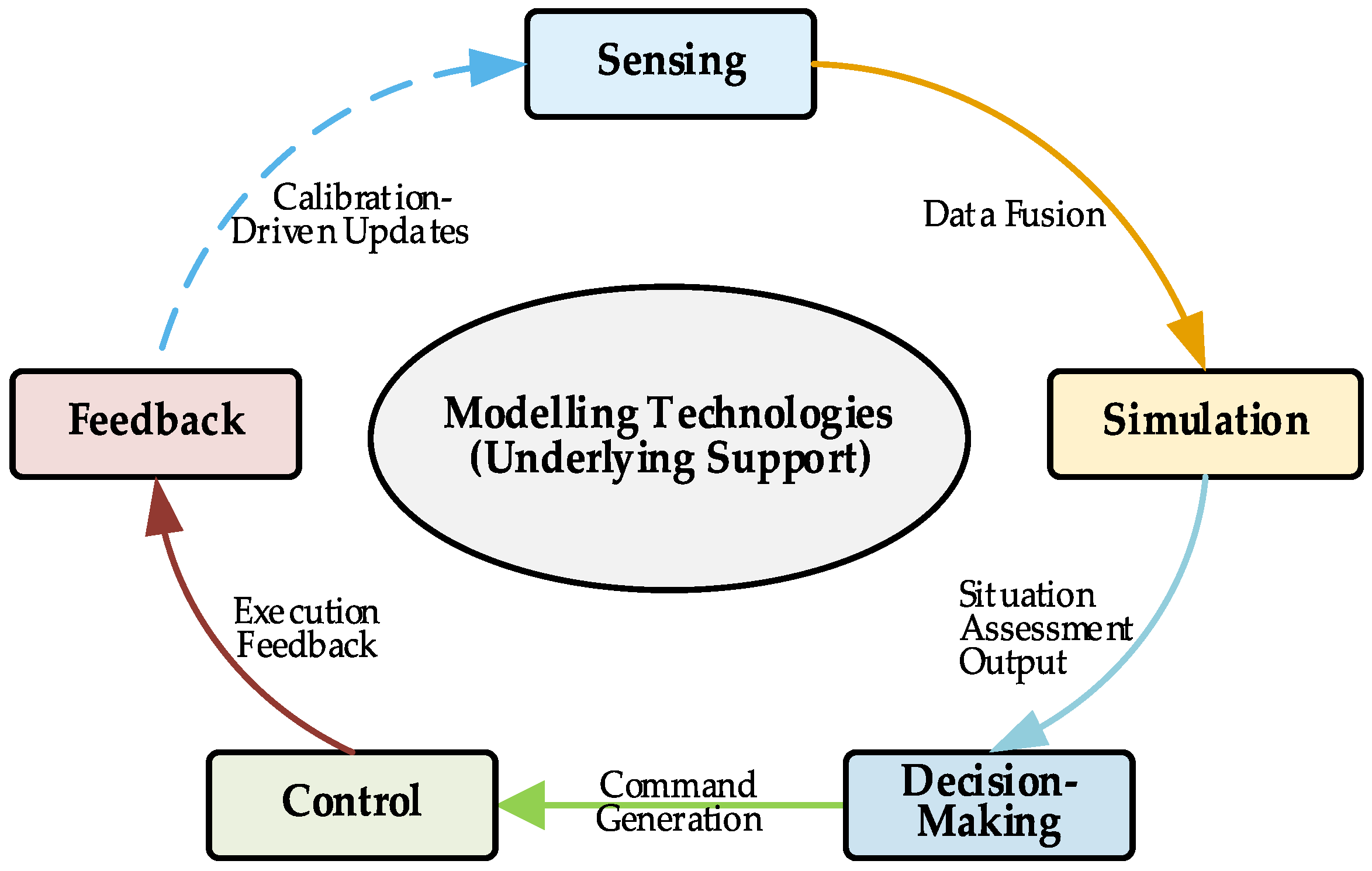

4.1. System Architecture

4.2. Three-Stage/Four-Level Maturity Model

4.2.1. Three Stages

4.2.2. Four Levels and Mapping

4.3. Core Technologies and Implementation Path

4.3.1. Multi-Domain, Multi-Scale Twin Modeling

4.3.2. Multi-Source Sensing and Data Fusion

4.3.3. Real-Time Coupled Multiphysics Simulation

4.3.4. Human-in-the-Loop Damage Control Decision-Making

4.3.5. Cyber-Physical Closed-Loop Control and Evaluation

5. Experiments and Results

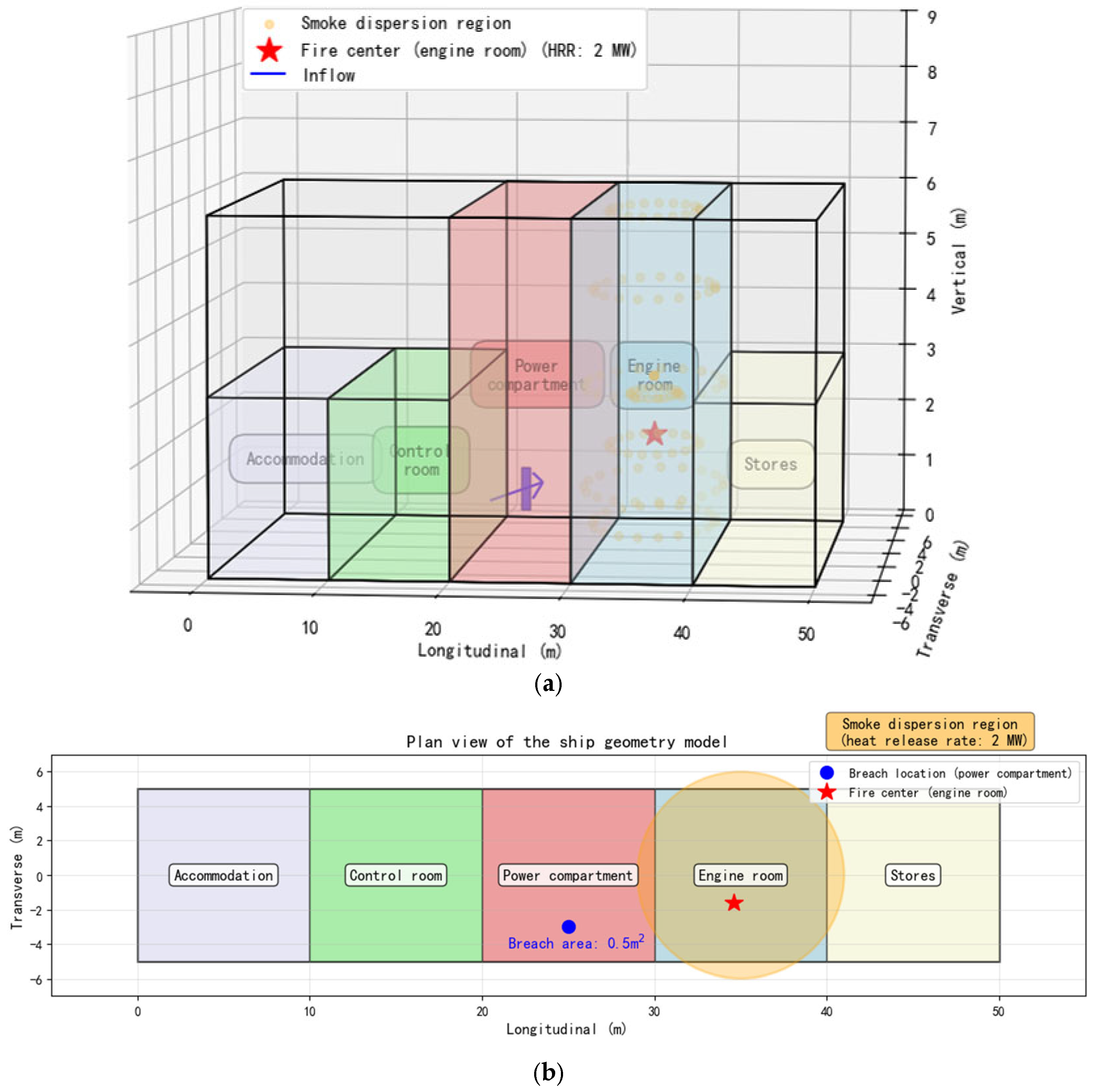

5.1. Numerical-Simulation Experiments: Platform and Setup

5.1.1. Scenario and Sensor Configuration

5.1.2. Algorithmic Implementation

5.1.3. Evaluation Metrics and Measurement Protocol

5.1.4. Experimental Platform and Environment

5.1.5. Model Coupling, Runtime Workflow, and Baseline Model

- (1)

- Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS) runs with the current actuation setpoints to simulate fire combustion processes (e.g., fuel combustion, heat release), outputting the heat source term and qualitative fire intensity indicators (sampled at the end of the step).

- (2)

- The MATLAB hydrodynamics module takes and fire-intensity indicators from FDS as inputs, updates breach-induced progressive flooding and global hull attitude (heel/trim) using the FVM solver via mass- and momentum-conservation relations, and advances temperature T and smoke concentration using the LBM solver for low-Mach fire/smoke transport in complex compartments.

- (3)

- Based on MATLAB’s solved states (breach inflow indicator, temperature/smoke levels, hull attitude) and the previous step’s action states (pump/valve/vent/suppressant status), per-step summaries are concatenated to form the observation vector for the TensorFlow DQN. The policy outputs joint discrete actions across pumps (off/half/full), valves (open/close), ventilation (on/off), and suppressant dosing (e.g., 0/5/10). A safety mask filters infeasible or unsafe combinations, and the valid actions are latched as the actuation setpoints for the next time step.

5.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

- (i)

- Heel angle. With real-time pump scheduling, the proposed framework maintains the heel angle at 4.8° (target ≤ 5°), outperforming the conventional method (6.2°). The improved attitude stability results from the multiphysics model that couples floodwater ingress with the vessel’s center-of-gravity dynamics (Figure 8a).

- (ii)

- Prediction error. Using an FVM-LBM coupled solver for multiphysics co-modeling, the predicted inflow rate (mean 0.42 m3/s) differs from the measured value (0.46 m3/s) by 8.7%, better than the conventional 12.2% (Figure 8b).Figure 8. Comparison between the proposed (digital-twin-based) control and the conventional method. (a) Hull heel angle. (b) Breach inflow rate. Shaded regions denote error bands. Vertical dashed lines mark key events: breach initiation, detection/alarm, control engaged, proposed/traditional peak inflow, steady-state onset, closed-loop stabilization, and recovery complete.Figure 8. Comparison between the proposed (digital-twin-based) control and the conventional method. (a) Hull heel angle. (b) Breach inflow rate. Shaded regions denote error bands. Vertical dashed lines mark key events: breach initiation, detection/alarm, control engaged, proposed/traditional peak inflow, steady-state onset, closed-loop stabilization, and recovery complete.

- (iii)

- Fire suppression time. With a DQN-optimized suppression policy, the average control time is 9.2 min, satisfying the ≤10 min target. The conventional baseline is longer (12.5 min) due to the lack of dynamic adaptation (Figure 9).

- (iv)

- Decision response time. The DQN model with CUDA acceleration achieves a mean response time of 2.6 s, outperforming the conventional 4.8 s and meeting the ≤3 s target. The reduction is attributable to efficient feature extraction and parallel computation (Figure 10).

- (v)

- Resource consumption. With optimized pump scheduling and agent dosing, the mean pumping energy consumption is 18.4 kWh and the mean extinguishing-agent usage is 125 kg, corresponding to reductions of 17.9% and 16.7%, respectively (Figure 11).

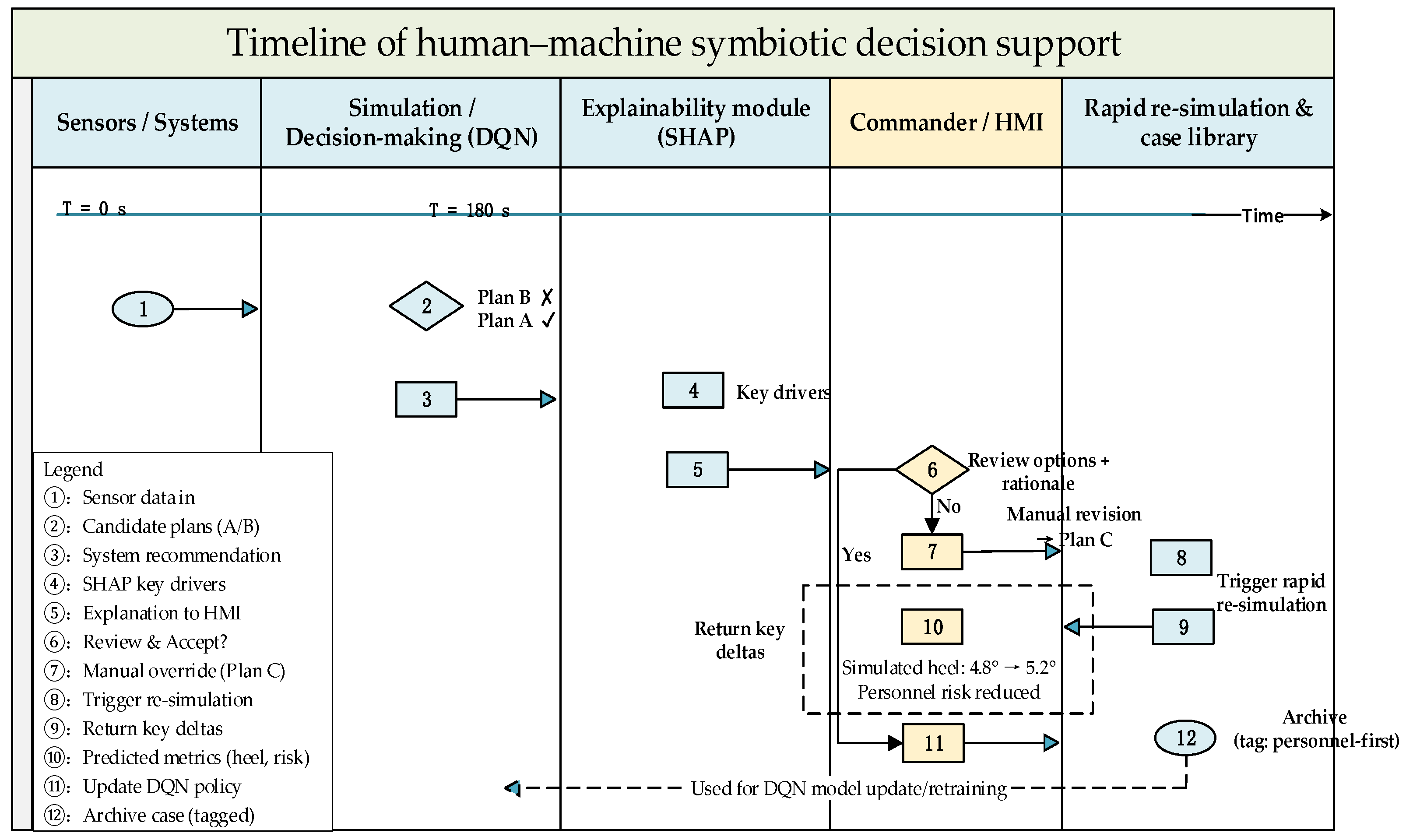

5.3. Decision-Support Case Walk-Through

5.4. Discussion

- (i)

- Physical consistency and calibration: use full-scale measurements to calibrate key parameters/boundaries; conduct scaled-platform or pier-side shadow runs to quantify and close the sim-to-real gap.

- (ii)

- Complex multi-hazard coupling: extend the framework to extreme and concurrent hazards, such as typhoons, explosions, multi-point fires, multi-breach flooding/immersion, smoke spread, and coupled power–structural effects; incorporate co-simulation and coordinated control strategies, together with safety-constrained optimization under common-cause failure conditions.

- (iii)

- Scenario generalization and robustness: improve generalization across vessel classes, compartment layouts, and operating/sea-state conditions; develop uncertainty-aware sim-to-real transfer with out-of-distribution (OOD) detection; apply parameter perturbation, domain randomization, and fault injection for rigorous uncertainty propagation and robustness assessment.

- (iv)

- Credible human–machine teaming evaluation and mechanism optimization: introduce objective metrics—time-to-decision, recommendation adoption/coverage, override frequency, and Cohen’s κ—and run controlled experiments in near-ship environments to quantify effectiveness and refine interaction/governance strategies.

- (v)

- Real-time optimization and deployment: employ model distillation and pruning, upgraded POD-CNN with mixed-precision, and more efficient decision optimizers (e.g., Proximal Policy Optimization, PPO); architect heterogeneous GPU + edge compute with dynamic scheduling, fault tolerance, and graceful degradation; and assess multi-GPU benefits for full-scale inference and multi-source fusion.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vassalos, D.; Mujeeb-Ahmed, M. Conception and evolution of the probabilistic methods for ship damage stability and flooding risk assessment. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madusanka, N.S.; Fan, Y.; Yang, S.; Xiang, X. Digital Twin in the Maritime Domain: A Review and Emerging Trends. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, F.; Kana, A. Digital twin for ship life-cycle: A critical systematic review. Ocean Eng. 2023, 269, 113479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Nam, Y.-S.; Kim, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lee, J.; Yang, H. Real-time digital twin for ship operation in waves. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 112867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Zhou, Z.; Han, F.; Peng, X.; Zhao, W.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Q. Real-time digital twin of autonomous ships based on virtual-physical mapping model. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 087109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Li, C.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, D. Real-time digital twin of ship structure deformation field based on the inverse finite element method. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, J.W.; Hariri-Ardebili, M.A. Verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification (VVUQ) in structural analysis of concrete dams. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 1452415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Ma, C.; Li, Q. An integrated method for assessing passenger evacuation performance in ship fires. Ocean Eng. 2022, 262, 112256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Ren, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, D.; Sun, J. Smoke simulation with detail enhancement in ship fires. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Knutsen, K.E.; Vanem, E.; Æsøy, V.; Zhang, H. A review of maritime equipment prognostics health management from a classification society perspective. Ocean Eng. 2024, 301, 117619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Gallego, C.; Lazakis, I. Mar-RUL: A remaining useful life prediction approach for fault prognostics of marine machinery. Appl. Ocean Res. 2023, 140, 103735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems; Kahlen, F.-J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lu, L.; Ye, L.; Zheng, S.; Wang, F.; Gao, X. Digital twin for command and control systems in naval applications. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 54, 890–901. [Google Scholar]

- Avazov, K.; Jamil, M.K.; Muminov, B.; Abdusalomov, A.B.; Cho, Y.-I. Fire Detection and Notification Method in Ship Areas Using Deep Learning and Computer Vision Approaches. Sensors 2023, 23, 7078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Sun, P.; Lin, B.; Li, W. Evolution of shipboard motor failure monitoring technology: Multi-physics field mechanism modeling and intelligent operation and maintenance system integration. Energies 2025, 18, 4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.W.; Wu, W.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Q.Y. Digital twin technical system for marine power systems. Chin. J. Ship Res. 2021, 16, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Zhou, S.W.; Wu, W. Digital twin-driven intelligent operation and maintenance technology for marine power systems. Chin. J. Ship Res. 2022, 17, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, M. Progress and prospects of digital twin-driven intelligent operation and maintenance for equipment full life cycle. Syst. Eng.-Theory Pract. 2025, 45, 1828–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kim, S.; Lee, K.; Shin, S.-C.; Choi, J.; Park, B.J.; Kang, H.J. Performance-based on-board damage control system for ships. Ocean Eng. 2021, 223, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidotti, L.; Prpić-Oršić, J.; Bertagna, S.; Bucci, V. A consolidated linearised progressive flooding simulation method for onboard decision support. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louvros, P.; Stefanidis, F.; Boulougouris, E.; Komianos, A.; Vassalos, D. Machine learning and case-based reasoning for real-time onboard prediction of the survivability of ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçel, A.L.; Bal Beşikçi, E.; Akyuz, E.; Arslan, O. Safety analysis of fire and explosion (F&E) accidents risk in bulk carrier ships under fuzzy fault tree approach. Saf. Sci. 2023, 158, 105972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, B.; Sun, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X. Research on the application of digital twin technology in simulation training system. Tact. Missile Technol. 2024, 4, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, T.; Kusumaatmaja, H.; Kuzmin, A.; Shardt, O.; Silva, G.; Viggen, E.M. The Lattice Boltzmann Method: Principles and Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirovich, L. Turbulence and the Dynamics of Coherent Structures. I. Coherent Structures. Q. Appl. Math. 1987, 45, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A. An Introduction to the Proper Orthogonal Decomposition. Curr. Sci. 2000, 78, 808–817. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, A.; Asfihani, T.; Osen, O.; Bye, R.T. Leveraging Digital Twins for Fault Diagnosis in Autonomous Ships. Ocean Eng. 2024, 292, 116546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engquist, B.; Li, X.; Ren, W.; Vanden-Eijnden, E. Heterogeneous Multiscale Methods: A Review. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2007, 2, 367–450. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, A.; Mauro, F.; Vassalos, D. The Role of Zone Models in the Numerical Prediction of Fire Scenario Outcomes Onboard Passenger Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xie, L. Study on the Active Wave Absorption Methods in Lattice Boltzmann Numerical Wave Tank. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Santasmasas, M.C.; De Rosis, A.; Hinder, I.; Moulinec, C.; Revell, A. A Coupled Finite Volume–Lattice Boltzmann Method for Incompressible Internal Flows. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2025, 314, 109686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xiao, X.; Li, W.; Desbrun, M.; Liu, X. Hybrid LBM–FVM Solver for Two-Phase Flow Simulation. J. Comput. Phys. 2024, 506, 112920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adadi, A.; Berrada, M. Peeking inside the black-box: A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52138–52160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, T.L.; Lavine, A.S.; Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, D.R., Jr. Self-Diffusion and Binary-Diffusion Coefficients in Gases; NIST Technical Note 2279; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MathWorks. MATLAB R2023a Updates Release Notes; MathWorks: Natick, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/content/dam/mathworks/mathworks-dot-com/support/updates/r2023a/r2023a-updates-release-notes.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Firemodels Developers. Fire Dynamics Simulator—Release v6.7.9; GitHub Repository, Release Page. Available online: https://github.com/firemodels/fds/releases/tag/FDS6.7.9 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- TensorFlow Developers. API Documentation (TensorFlow v2.10.1); Google LLC: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/versions/r2.10/api_docs (accessed on 3 December 2025).

| Dimension | Digital Twins (DTs) | Modeling and Simulation (M&S) | Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) | Parallel Systems (PS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core idea | Bidirectional mapping; online data assimilation; closed-loop optimization/control | Model abstraction; behavioral simulation; plan verification (mostly offline) | Integrated sensing-computing-control; process-level monitoring/control | Artificial systems + computational experiments + parallel execution (ACP); policy co-evolution |

| Data Integration Fidelity | High (continuous multi-source alignment; full cyber-physical fidelity) | Low (discrete model-centric input; limited physical fidelity) | Medium (device/process-level fusion; partial subsystem fidelity) | Medium (artificial-computational interaction; policy-validation focused fidelity) |

| Real-time capability | High (continuous data streams) | Low-medium (mostly offline) | High (device/process level) | Medium (parallel interaction; not hard real-time) |

| Suitability for ship DC | High (state mapping, evolution, closed-loop decisions) | Medium (plan selection, validation) | Medium (subsystem control/alarms) | Medium (policy-level parallel experimentation/optimization) |

| Core Capability | Enabling Baselines |

|---|---|

| CR-1 fast multi-hazard simulation (≤3 s; fire ≤ 2 s; smoke 5 min trend) | BR-01 5–10 Hz and time-aligned fusion; BR-02 unified model and error budgets; BR-04 OPC UA/MQTT/NMEA 2000, HIL traceability |

| CR-2 scheme generation and collaborative optimization (3 plans; trigger-based revision; auditable HMI) | BR-02 param. interfaces for optimization; BR-03 HMI explainability and audit; BR-04 command/telemetry QoS (≤2 s ack); BR-01 stable state inputs |

| CR-3 cyber-physical closed loop and feedback (dispatch ≤ 2 s; 5 min calibration; ≥10% error reduction) | BR-04 dispatch → ack ≤ 2 s, end-to-end traceability; BR-01 feedback signals; BR-02 calibration hooks/versioning; BR-03 human-in-the-loop safeguards |

| Level | Stage | Definition (Human Role) |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | Digital Shadow | Monitoring only; no control; human-in-the-loop for interpretation. |

| L2 | Digital Twin | What-if simulation; human approves actions. |

| L3 | Digital Twin | Assisted plan generation; human-in-the-loop with override. |

| L4 | Digital Intelligence | Closed-loop control; safety-critical actions require confirmation. |

| Process Stage | Core Technology | Technical Role |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling Foundation | Multi-domain, multi-scale DC twin modeling | Provide high-fidelity models for sensing, simulation, and decision-making |

| Sensing | Multi-source sensing and data fusion | Accurate state acquisition and data preprocessing |

| Simulation | Real-time coupled multiphysics simulation | Reconstruct the multi-hazard evolution and produce state predictions |

| Decision | Human-in-the-loop DC decision-making | Generate interpretable action plans |

| Control and Feedback | Cyber-physical closed-loop control and evaluation | Execute plans, assess performance, and calibrate the DT |

| Sensor Type | Sampling Rate (Hz) | Measured Parameters (Range, Accuracy) | Primary Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure sensor | 10 | flooding rate 0–0.5 m3/s (±0.01 m3/s) | drives flooding simulation |

| Temperature sensor | 5 | compartment temperature 20–800 °C (±1 °C) | drives fire simulation |

| Smoke concentration (CO) sensor | 5 | 0–1000 ppm (±5 ppm) | drives smoke-dispersion simulation |

| Inclinometer | 10 | hull attitude 0–15° (±0.1°) | survivability assessment |

| Process Stage | Proposed | Traditional | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hull heel angle (°) | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 6.2 ± 0.4 | 22.6% |

| Simulation error (breach inflow rate, %) | 8.7 ± 0.8 | 12.2 ± 1.3 | 28.7% |

| Fire control time (min) | 9.2 ± 0.6 | 12.5 ± 0.9 | 26.4% |

| Decision response time (s) | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 45.8% |

| Pump energy consumption (kWh) | 18.4 ± 0.9 | 22.4 ± 1.1 | 17.9% |

| Extinguishing agent consumption (kg) | 125 ± 6 | 150 ± 8 | 16.7% |

| Scenario Type | Equivalent Number of Compartments | Number of Computational Cells | Coupled Simulation Latency (s) | Flooding-Rate MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current case | 30 | 150,000 | 1.8 | 8.7 |

| Extended case 1 | 50 | 250,000 | 2.5 | 9.1 |

| Extended case 2 | 100 | 500,000 | 3.8 | 9.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Huang, J. Digital Twin Framework for Predictive Simulation and Decision Support in Ship Damage Control. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122348

Wang B, Hou Y, Zhang Y, Wang K, Huang J. Digital Twin Framework for Predictive Simulation and Decision Support in Ship Damage Control. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122348

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Bo, Yue Hou, Yongsheng Zhang, Kangbo Wang, and Jianwei Huang. 2025. "Digital Twin Framework for Predictive Simulation and Decision Support in Ship Damage Control" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122348

APA StyleWang, B., Hou, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, K., & Huang, J. (2025). Digital Twin Framework for Predictive Simulation and Decision Support in Ship Damage Control. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122348