Waves as Energy Source for Desalination Plants in Islands

Abstract

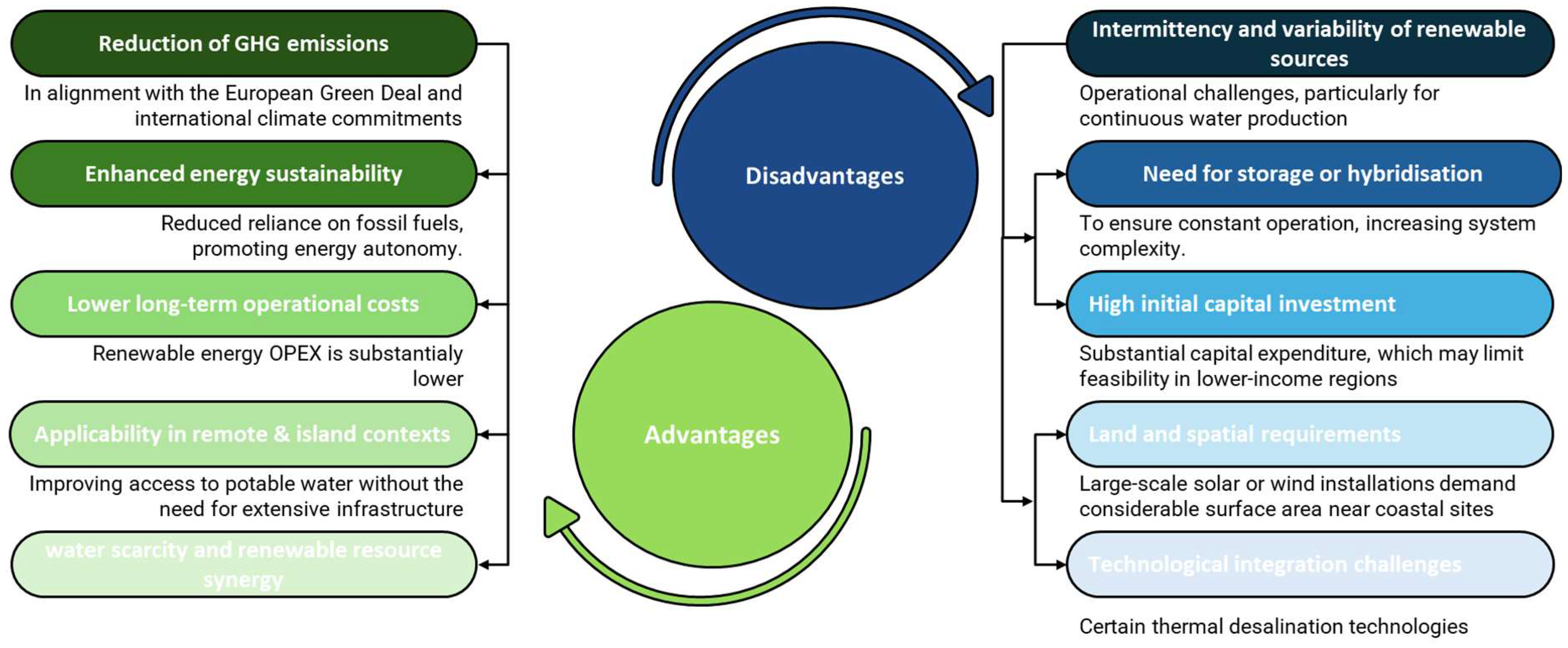

1. Introduction

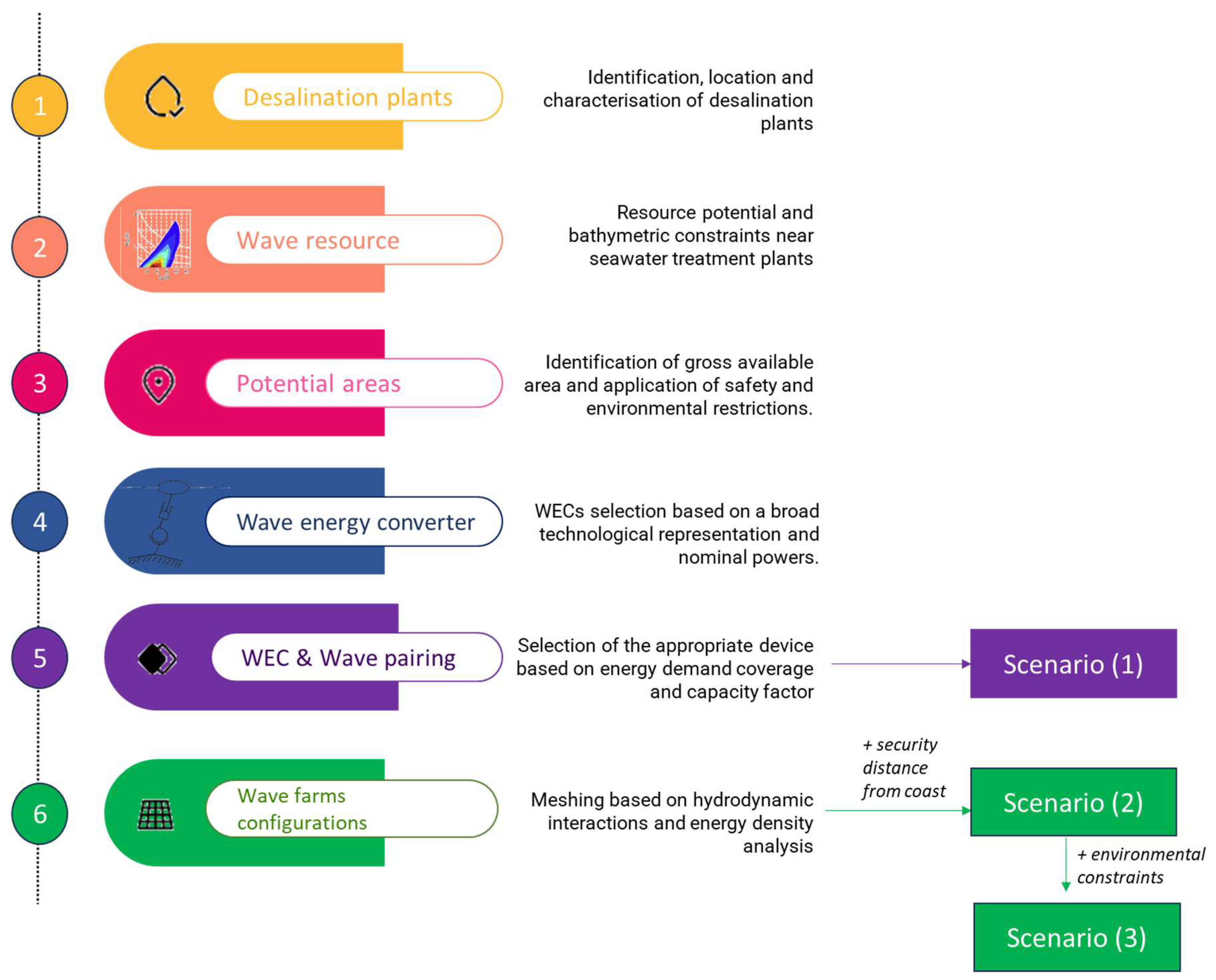

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Step 1: Identification of Desalinated Water Production Centers

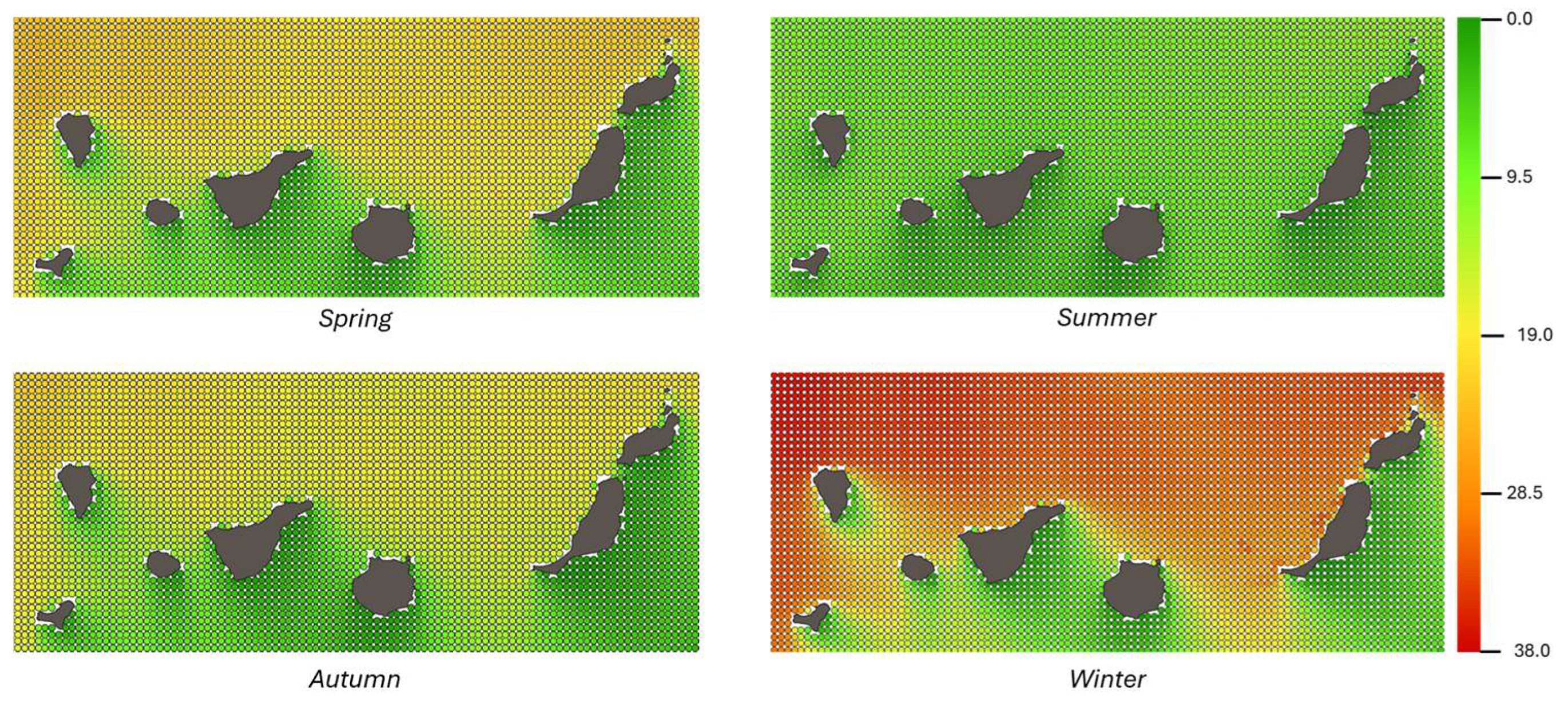

2.2. Step 2: Wave Resource Data Acquisition and Processing

2.3. Step 3: Potential Areas for Wave Energy Deployment and Environmental Constraints

2.4. Step 4: Wave Energy Converter Selection

2.5. Step 5: Individual Wave Energy Converter Selection by Wave Resource Pairing

2.6. Step 6: Wave Farm Configurations

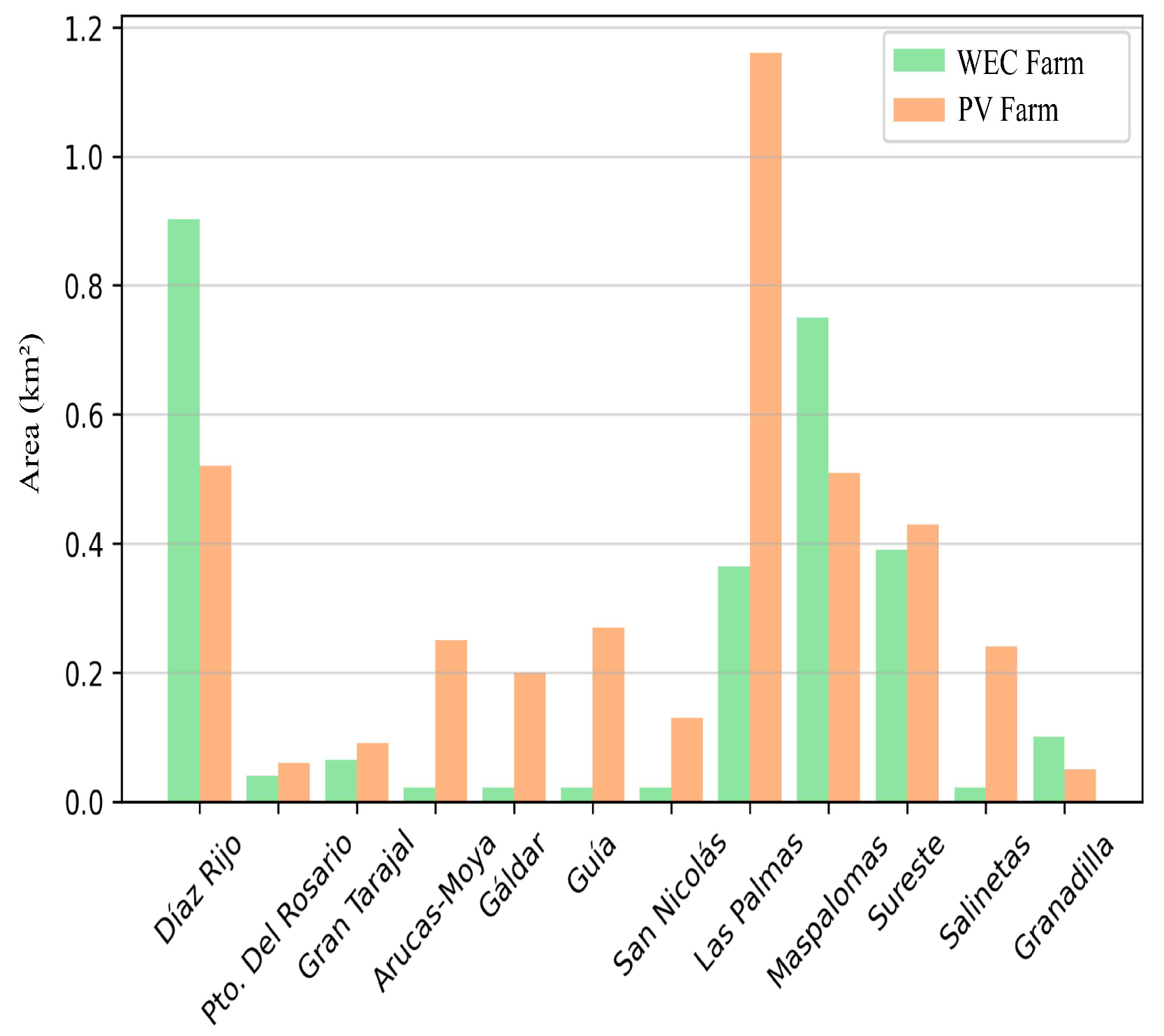

2.7. Step 7: Wave Farms vs. PV Farms Surface Covered

3. Results and Discussion

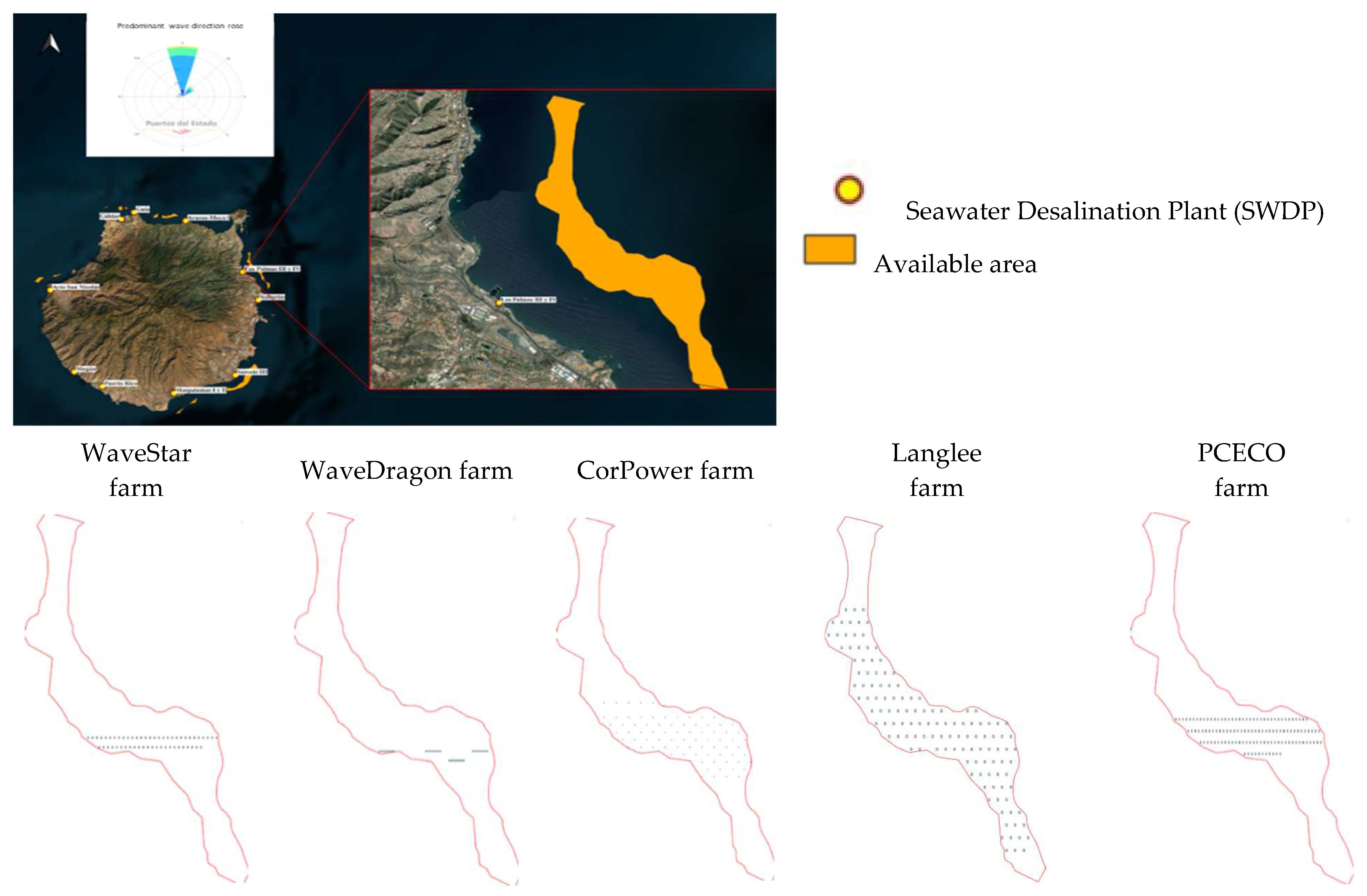

3.1. Wave Resource and Potential Area Assessment

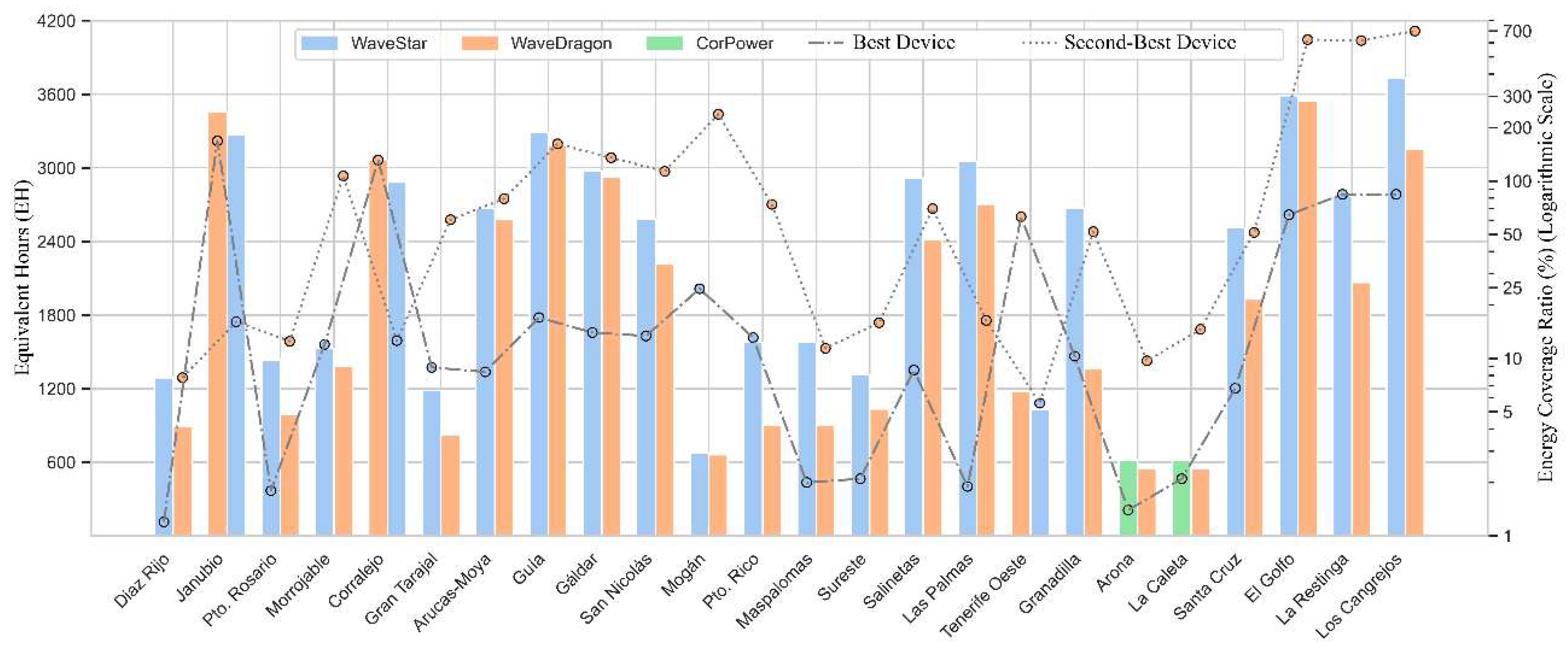

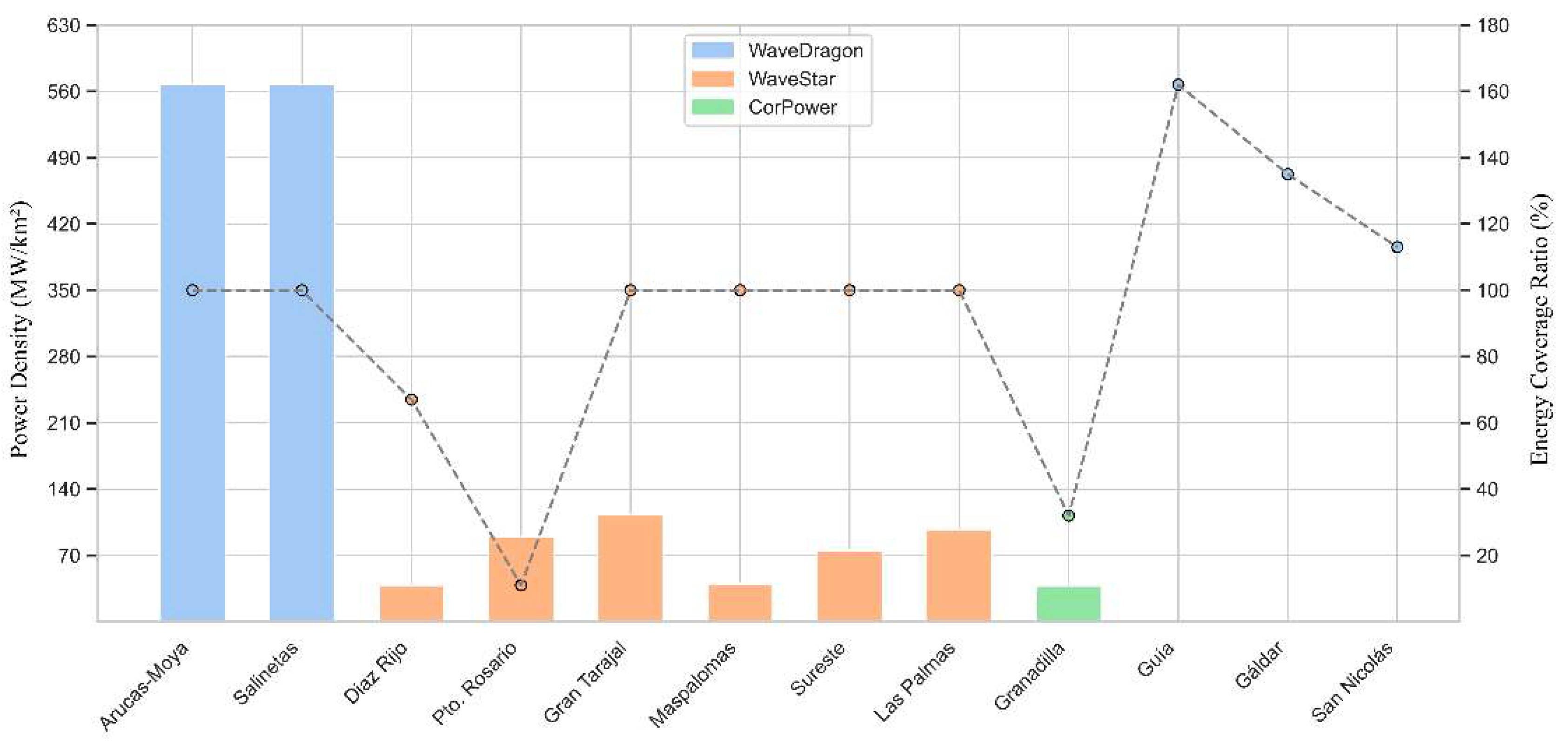

3.2. Single Device Design: Scenario 1

3.3. Scenario 2: Wave Farm Configuration Results

3.4. Scenario 3: Wave Farm Configuration with Environmental Restrictions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RO | Reverse Osmosis |

| SD | Scatter diagram |

| RE | Renewable energy |

| PV | Solar photovoltaic |

| SWDP | Seawater Desalination Plant |

| SPA | Special Protection Area for birds |

| SAC | Special Areas of conservation |

| SCI | Sites of community Importance |

| PNA | Protected Natural Area |

| WEC | Wave Energy Converter |

| EH | Equivalent Hour |

| CF | Capacity Factor |

| AEP | Annual Energy Production |

| PR | Performance Ratio |

| GCR | Ground Coverage Ratio |

| GTI | Global Tilted Irradiance |

References

- Shahzad, M.W.; Burhan, M.; Ang, L.; Ng, K.C. Energy-water-environment nexus underpinning future desalination sustainability. Desalination 2017, 413, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.; Qadir, M.; van Vliet, M.T.; Smakhtin, V.; Kang, S.-M. The state of desalination and brine production: A global outlook. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 657, 1343–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Siddiqi, A.; Anadon, L.D.; Narayanamurti, V. Towards sustainability in water-energy nexus: Ocean energy for seawater desalination. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3833–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, M.; Jones, E.R.; Bierkens, M.F.; van Vliet, M.T. Global energy consumption of water treatment technologies. Water Res. 2025, 277, 123245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Badrelzaman, M.; Darwish, N.N.; Darwish, N.A.; Hilal, N. Reverse osmosis desalination: A state-of-the-art review. Desalination 2019, 459, 59–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Electricity Generation mix for Selected Regions, 2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/electricity-generation-mix-for-selected-regions-2024 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Abdelkareem, M.A.; Assad, M.E.H.; Sayed, E.T.; Soudan, B. Recent progress in the use of renewable energy sources to power water desalination plants. Desalination 2018, 435, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okampo, E.J.; Nwulu, N. Optimisation of renewable energy powered reverse osmosis desalination systems: A state-of-the-art review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopus Research Database. Analysis of topics/areas of research published in the desalination sector between 2020 and 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/results/results.uri?st1=Desalination+sector&st2=&s=TITLE-ABS-KEY%28Desalination+sector%29&limit=10&origin=resultslist&sort=plf-f&src=s&sot=b&sdt=cl&sessionSearchId=bbad0762bf1e7341da85efde4ea20d07&cluster=scosubtype%2C%22ar%22%2Ct%2C%22re%22%2Ct (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Ayaz, M.; Namazi, M.; Din, M.A.U.; Ershath, M.M.; Mansour, A.; Aggoune, E.-H.M. Sustainable seawater desalination: Current status, environmental implications and future expectations. Desalination 2022, 540, 116022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, D.; Franzitta, V.; Guercio, A. A Review of the Water Desalination Technologies. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, E.T.; Olabi, A.; Elsaid, K.; Al Radi, M.; Alqadi, R.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Recent progress in renewable energy based-desalination in the Middle East and North Africa MENA region. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 48, 125–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IRENA. Water Desalination Using Renewable Energy ENERGY TECHNOLOGY SYSTEMS ANALYSIS PROGRAMME. Int. Renew. Energy Agency 2012, 1–28. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2012/IRENA-ETSAP-Tech-Brief-I12-Water-Desalination.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Azevedo, F.D.A.S.M. Renewable Energy Powered Desalination Systems: Technologies and Market Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Department of Geographical, Geophysical and Energy Engineering, Faculty of Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Walch, A.; Rüdisüli, M. Strategic PV expansion and its impact on regional electricity self-sufficiency: Case study of Switzerland. Appl. Energy 2023, 346, 121262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, E.; McLellan, B.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Tezuka, T. The Role of Renewable Energy Resources in Sustainability of Water Desalination as a Potential Fresh-Water Source: An Updated Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiblawey, Y.; Alassi, A.; Abideen, M.Z.U.; Bañales, S. Techno-economic assessment of increasing the renewable energy supply in the Canary Islands: The case of Tenerife and Gran Canaria. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, A.; Badruzzaman, M.; Oppenheimer, J.; Jacangelo, J.G. Energy minimization strategies and renewable energy utilization for desalination: A review. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1907–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karaghouli, A.; Kazmerski, L.L. Energy consumption and water production cost of conventional and renewable-energy-powered desalination processes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 24, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiner, D.; Salcedo-Puerto, O.; Immonen, E.; van Sark, W.G.; Nizam, Y.; Shadiya, F.; Duval, J.; Delahaye, T.; Gulagi, A.; Breyer, C. Powering an island energy system by offshore floating technologies towards 100% renewables: A case for the Maldives. Appl. Energy 2022, 308, 118360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamaileh, D.; Quran, O.; Almajali, M.R. Study the effect of solar power on the efficiency of desalinating saline water: Case studies Al-Khafji and Gulf of Aqaba areas. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallenberg-Rodríguez, J.; Del Rio-Gamero, B.; Melian-Martel, N.; Alecio, T.L.; Herrera, J.G. Energy supply of a large size desalination plant using wave energy. Practical case: North of Gran Canaria. Appl. Energy 2020, 278, 115681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M.; Karimpour, F.; Goudey, C.A.; Jacobson, P.T.; Alam, M.-R. Ocean wave energy in the United States: Current status and future perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 74, 1300–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río-Gamero, B.; Alecio, T.L.; Schallenberg-Rodríguez, J. Performance indicators for coupling desalination plants with wave energy. Desalination 2022, 525, 115479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzitta, V.; Curto, D.; Milone, D.; Viola, A. The Desalination Process Driven by Wave Energy: A Challenge for the Future. Energies 2016, 9, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, J.A. The Canary Islands experience: Current non-conventional water resources and future perspectives. In Proceedings of the Regional Conference Advancing Non-Conventional Water Resources Management in Mediterranean Islands and Coastal Areas: Local Solutions, Employment Opportunities and People Engagement, Birgu, Malta, 10–11 May 2018; p. 26. Available online: https://www.gwp.org/contentassets/aa500f6c8cb749d7ac324a4065395386/203.the-canary-islands-experience.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Leon, F.; Ramos-Martin, A.; Perez-Baez, S.O. Study of the Ecological Footprint and Carbon Footprint in a Reverse Osmosis Sea Water Desalination Plant. Membranes 2021, 11, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, P.; Lund, H.; Carta, J.A. Smart renewable energy penetration strategies on islands: The case of Gran Canaria. Energy 2018, 162, 421–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benahmed, A.; Bessedik, M.; Abdelbaki, C.; Mokhdar, S.A.; Goosen, M.F.; Höllerman, B.; Zouhiri, A.; Badr, N. Investigating the long-term economic sustainability and water production costs of desalination plants: A case study from Chatt Hilal in Algeria. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2025, 51, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, G.; Carballo, R. Wave resource in El Hierro—An island towards energy self-sufficiency. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, G.; Carballo, R. Wave power for La Isla Bonita. Energy 2010, 35, 5013–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.; González-Marco, D.; Sospedra, J.; Gironella, X.; Mösso, C.; Sánchez-Arcilla, A. Wave energy resource assessment in Lanzarote (Spain). Renew. Energy 2013, 55, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veigas, M.; Iglesias, G. Wave and offshore wind potential for the island of Tenerife. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 76, 738–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choupin, O.; Del Río-Gamero, B.; Schallenberg-Rodríguez, J.; Yánez-Rosales, P. Integration of assessment-methods for wave renewable energy: Resource and installation feasibility. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 455–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río-Gamero, B.; Choupin, O.; Melián-Martel, N.; Schallenberg-Rodriguez, J. Application of a revised integration of methods for wave energy converter and farm location pair mapping. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 303, 118170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharram, N.A.; Konsowa, A.H.; Shehata, A.I.; El-Maghlany, W.M. Sustainable seascapes: An in-depth analysis of multigeneration plants utilizing supercritical zero liquid discharge desalination and a combined cycle power plant. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 118, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, F.; Ramos, A.; Perez-Baez, S.O. Optimization of Energy Efficiency, Operation Costs, Carbon Footprint and Ecological Footprint with Reverse Osmosis Membranes in Seawater Desalination Plants. Membranes 2021, 11, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canal Gestión Lanzarote. Desalación y Producción. Available online: https://www.canalgestionlanzarote.es/inicio/nuestro-ciclo-integral-del-agua/produccion-desalacion/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- ELMASA. Mejora en la EDAM de Puerto Rico. 2020. Available online: https://elmasa.es/proyectos/proyecto-4/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Consejo Insular de aguas de Gran Canaria. Plan hidrológico de la isla de Gran Canaria. 2024. Available online: https://www.aguasgrancanaria.com/plan_hidro.php (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Consejo insular de aguas de El Hierro. Plan hidrológico de la isla de El Hierro. 2018. Available online: https://www.aguaselhierro.org/planificacion/plan-hidrologico/vigente/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Consejo Insular de Aguas de Tenerife. Plan hidrológico de la isla de Tenerife. 2018. Available online: https://aguastenerife.org/images/pdf/PHT1erCiclo/2_ciclo/ES124_PHD.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Consorcio de Abastecimiento de Aguas a Fuerteventura, “EDAM Gran Tarajal”. 2021. Available online: https://caaf.es/el-caaf/dto-de-produccion/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Chirivella Guerra, J. Oral communication with the head of the water resources department of the Gran Canaria Island Water Council. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cartográfica de Canarias—GRAFCAN. Ortofoto Territorial. 2022. Available online: https://visor.grafcan.es/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Veigas, M.; Carballo, R.; Iglesias, G. Wave and offshore wind energy on an island. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertos del Estado. SIMAR Hindcast Database. Available online: https://www.puertos.es/servicios/oceanografia (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Losada, A.I.J.; Pascual, C.V.; Incera, F.J.M.; Solana, R.M.; Landeira, S.R.; Braña, P.C.; Sampedro, N.K.B.T. Evaluación Del Potencial de La Energía de Las Olas Estudio Técnico Plan Energias Renovables (PER) 2011–2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.idae.es/uploads/documentos/documentos_11227_e13_olas_b31fcafb.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Mérigaud, A.; Ringwood, J.V. Power production assessment for wave energy converters: Overcoming the perils of the power matrix. Proc IMechE 2018, 232, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folley, M. Numerical Modelling of Wave Energy Converters: State-of-the-Art Techniques for Single Devices and Arrays; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, G.; Jones, C.A.; Roberts, J.D.; Neary, V.S. A comprehensive evaluation of factors affecting the levelized cost of wave energy conversion projects. Renew. Energy 2018, 127, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arean, N.; Carballo, R.; Iglesias, G. An integrated approach for the installation of a wave farm. Energy 2017, 138, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choupin, O.; Têtu, A.; Del Río-Gamero, B.; Ferri, F.; Kofoed, J. Premises for an annual energy production and capacity factor improvement towards a few optimised wave energy converters configurations and resources pairs. Appl. Energy 2022, 312, 118716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, R.; Molina, A.T.; González, A. Going further than the scatter diagram: Tools for analysing the wave resource and classifying sites. In Proceedings of the 11th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Nantes, France, 6–11 September 2015; pp. 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission. EMODnet Portal. Available online: https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/en/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Gobierno de España. Red Natura 2000: Cartografía. 2020. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/biodiversidad/servicios/banco-datos-naturaleza/informacion-disponible/rednatura_2000_desc.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Gobierno de Canarias. Reservas Marinas de Canarias. 2019. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/pesca/temas/reservas_marinas/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Gobierno de Canarias. Espacios Naturales Protegidos (ENP). 2020. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/cartografia-y-sig/ide/descargas/biodiversidad/enp.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Gobierno de España. La Red de Parques Nacionales. 2020. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/parques-nacionales-oapn/red-parques-nacionales.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Gobierno de España. Reservas Marinas de España. 2020. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/pesca/temas/proteccion-recursos-pesqueros/reservas-marinas-de-espana/default.aspx (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Gobierno de España. Ordenación del Espacio Marítimo. 2023. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/cartografia-y-sig/ide/descargas/costas-medio-marino/poem.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Yanez-Rosales, P.; Del Río-Gamero, B.; Schallenberg-Rodríguez, J. Rationale for selecting the most suitable areas for offshore wind energy farms in isolated island systems. Case study: Canary Islands. Energy 2024, 307, 132589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Medina, S.; Santana-Sarmiento, F. Evaluation method of marine spaces for the planning and exploitation of offshore wind farms in isolated territories. A two-island case study. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 239, 106603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Santos, L. Decision variables for floating offshore wind farms based on life-cycle cost: The case study of Galicia (North-West of Spain). Ocean Eng. 2016, 127, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.; Iglesias, G. Mapping of the levelised cost of energy from floating solar PV in coastal waters of the European Atlantic, North Sea and Baltic Sea. Sol. Energy 2024, 279, 112809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yao, L.; Zhou, C. Assessment of offshore wind-solar energy potentials and spatial layout optimization in mainland China. Ocean Eng. 2023, 287, 115914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouz, D.; Carballo, R.; López, I.; Álvarez, B.; Iglesias, G. Floating solar photovoltaic energy for coastal areas: A siting methodology. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 528, 146733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, J.; Jin, X.; Shi, J.; Chan, N.W.; Tan, M.L.; Lin, X.; Ma, X.; Lin, X.; Zheng, K.; et al. The Impact of Offshore Photovoltaic Utilization on Resources and Environment Using Spatial Information Technology. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlee Company. Langlee Wave Power. Available online: http://www.langleewp.com/e-brochure/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Sorensen, H.; Friis-Madsen, E.; Christensen, L.; Kofoed, J.P.; Frigaard, P.B.; Knapp, W. The results of two years testing in real sea of Wave Dragon. In Proceedings of the 6th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Glasgow, UK, 29 August–2 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Majidi, A.G.; Ramos, V.; Rosa-Santos, P.; das Neves, L.; Taveira-Pinto, F. Power production assessment of wave energy converters in mainland Portugal. Renew. Energy 2025, 243, 122540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CorPowerocean. CorPower Ocean’s Wave Energy Converter Deployed in Portugal. Available online: https://corpowerocean.com/corpower-oceans-wave-energy-converter-deployed/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- European Marine Energy Center. CorPower HiWave-3 at EMEC. Available online: https://tethys.pnnl.gov/project-sites/corpower-hiwave-3-emec (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Venugopal, V.; Tan, T. Hydrodynamic Assessment of the CorPower C4 Point Absorber Wave Energy Converter in Extreme Wave Conditions. In Proceedings of the ASME 2024 43rd International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Singapore, 9–14 June 2024; ISBN 978-0-7918-8785-1. [Google Scholar]

- Al Shami, E.; Zhang, R.; Wang, X. Point Absorber Wave Energy Harvesters: A Review of Recent Developments. Energies 2019, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, M.; Estejab, B.; Henry, F. Implementation of machine learning techniques for the analysis of wave energy conversion systems: A comprehensive review. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy 2024, 10, 641–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friss-Madsen, E. Personal communication with Managing Director of wave Dragon. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Holthuijsen, L.H. Waves in Oceanic and Coastal Waters; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- García-Medina, G.; Özkan-Haller, H.T.; Ruggiero, P. Wave resource assessment in Oregon and southwest Washington, USA. Renew. Energy 2014, 64, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguero, B.G.; Losada, I.J.; Mendez, F.J. A global wave power resource and its seasonal, interannual and long-term variability. Appl. Energy 2015, 148, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC TS 62600-101; Marine Energy—Wave, Tidal and Other Water Current Converters—Part 101: Wave Energy Resource Assessment and Char-Acterization. International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 9782832700365.

- Fernandez, G.V.; Balitsky, P.; Stratigaki, V.; Troch, P. Coupling Methodology for Studying the Far Field Effects of Wave Energy Converter Arrays over a Varying Bathymetry. Energies 2018, 11, 2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigaki, V.; Troch, P.; Forehand, D. A fundamental coupling methodology for modeling near-field and far-field wave effects of floating structures and wave energy devices. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 1608–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troch, P.; Beels, C.; De Rouck, J.; De Backer, G. Wake effects behind a farm of wave energy converters for irregular long-crested and short-crested waves. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Coastal Engineering, Shanghai, China, 30 June–5 July 2010; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Beels, C.; Troch, P.; De Visch, K.; De Backer, G.; De Rouck, J.; Kofoed, J. Numerical simulation of wake effects in the lee of a farm of Wave Dragon wave energy converters. In Proceedings of the 8th European Wave and Tidal Conference: EWTEC 2009, Uppsala, Sweden, 7–11 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Atan, R.; Finnegan, W.; Nash, S.; Goggins, J. The effect of arrays of wave energy converters on the nearshore wave climate. Ocean Eng. 2019, 172, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babarit, A. On the park effect in arrays of oscillating wave energy converters. Renew. Energy 2013, 58, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, B.; Venugopal, V. Optimal configurations of wave energy device arrays. Ocean Eng. 2010, 37, 1402–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrés, A.; Guanche, R.; Meneses, L.; Vidal, C.; Losada, I. Factors that influence array layout on wave energy farms. Ocean Eng. 2014, 82, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzi, S.; Giassi, M.; Miquel, A.M.; Antonini, A.; Bizzozero, F.; Gruosso, G.; Archetti, R.; Passoni, G. Wave energy farm design in real wave climates: The Italian offshore. Energy 2017, 122, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristodemo, F.; Ferraro, D.A. Feasibility of WEC installations for domestic and public electrical supplies: A case study off the Calabrian coast. Renew. Energy 2018, 121, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Chozas, J. Una aproximación a la energía de las olas para la generación de electricidad. Final Degree Project. Department of Electrical Engineering. Higher Technical School of Industrial Engineering. Polytechnic University of Madrid. 2008. Available online: https://oa.upm.es/1203/1/PFC_JULIA_FERNANDEZ_CHOZAS.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Bastos, P.; Devoy-McAuliffe, F.; Arredondo-Galeana, A.; Chozas, J.F.; Lamont-Kane, P.; Vinagre, P.A. Life Cycle Assessment of a wave energy device—LiftWEC. In Proceedings of the European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Bilbao, Spain, 3–7 September 2023; Volume 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcome to Python.org. Available online: https://www.python.org/ (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- Chiri, H.; Pacheco, M.; Rodríguez, G. Spatial variability of wave energy resources around the Canary Islands. In WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2013; pp. 15–26. ISSN 1743-3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JA SOLAR. Harvest the Sunshine: 650 W (JAM72D42 LB). Available online: https://www.jasolar.com/statics/gaiban/pdfh5/pdf.html?file=https://www.jasolar.com/uploadfile/fujian/2024/1120/b1d39cfaeb1d0f5.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Dupont, E.; Koppelaar, R.; Jeanmart, H. Global available solar energy under physical and energy return on investment constraints. Appl. Energy 2020, 257, 113968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Seawater Desalination Plant | Municipality | Nominal Capacity (m3/d) | Specific Energy Consumption (kWh/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lanzarote island | |||

| Diaz Rijo | Arrecife | 58,000 | 3.16 |

| Janubio | Yaiza | 9500 | 3.5 |

| Fuerteventura island | |||

| Puerto del Rosario | Pto. Rosario | 36,500 | 3.5 |

| Morrojable | Morrojable | 4400 | 3.5 |

| Corralejo | La oliva | 12,400 | 3.04 |

| Gran Tarajal | Gran Tarajal | 5000 | 4.4 |

| El Hierro island | |||

| El Golfo | Frontera | 1350 | 3.05 |

| La Restinga | El Pinar | 1700 | 3.18 |

| Los Cangrejos | Valverde | 2400 | 3.04 |

| Gran Canaria island | |||

| Arucas-Moya I | Arucas | 15,000 | 3.5 |

| Guía | Roque Prieto | 10,000 | 3.18 |

| Gáldar | Bocabarranco | 10,000 | 3.5 |

| Ayto. San Nicolás | La Aldea | 10,400 | 3.04 |

| Mogán | Mogán | 1800 | 2.5 |

| Puerto Rico | Puerto Rico | 8000 | 3.04 |

| Las Palmas III & IV | Jinámar | 80,000 | 3.33 |

| Maspalomas I & II | San Agustín | 39,700 | 3.21 |

| Sureste III | Pozo Izquierdo | 30,000 | 3.5 |

| Salinetas | Salinetas | 16,000 | 3.5 |

| Tenerife island | |||

| UTE Tenerife Oeste | Fonsalía | 14,000 | 2.16 |

| UTE Desalinizadora de Granadilla | Granadilla de Abona | 14,000 | 3.04 |

| Adeje Arona | Arona | 30,000 | 3.04 |

| Santa Cruz I | Santa Cruz | 20,000 | 3.04 |

| La Caleta | Adeje | 20,000 | 3.04 |

| Constraint | Shape Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental restrictions | ||

| NATURA 2000 | 2020 | [56] |

| Special Protection Areas for birds (SPAs) | ||

| Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) | ||

| Sites of Community Importance (SCI) | ||

| Marine Reserves | 2019 | [57] |

| Protected Natural Areas (PNAs) | 2020 | [58] |

| National Parks | 2020 | [59] |

| Infrastructure restrictions | ||

| Fishing activities areas | 2020 | [60] |

| Navigation corridors | 2023 | [61] |

| Industrial parks and port access routes | 2021 | [62] |

| Buoys | 2020 | [62] |

| Marine cables | 2020 | [62] |

| WEC | Device Area (m2) | Relevant Dimension (m) | Nominal Power (kW) | Classification | Operating Depth (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WaveDragon | 13,000 | 260 | 5900 | Terminator | 30–50 |

| WaveStar | 555 | 12 | 600 | Point absorber | 30–50 |

| CorPower | 79 | 9 | 750 | Point absorber | >30 |

| Langlee | 1500 | 9.5 | 1665 | OWSC | >30 |

| PCECO | 530 | 9 | 480 | OWSC | 10–50 |

| Parameter | Variant 1. Terminator (WaveDragon) | Variant 2. Oscillating Wave Surge Converter (OWSC: Langlee/PCECO) | Variant 3. Point Absorber (Wavestar/CorPower) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology type | Overtopping terminator | Hinged-flap surge device | Heaving point absorber |

| Operation principle | Overtopping of incoming waves into a reservoir driving low-head turbines | Horizontal back-and-forth rotation of a flap driven by surge motion | Vertical heave motion converted to power via PTO |

| Best suited environment | High-energy wave climates | Nearshore areas with strong surge motion | Deep to intermediate waters |

| Bathymetry sensitivity | Moderate (requires uniform depth for stable overtopping) | High (performance strongly depends on local seabed slope) | Low-to-moderate |

| Spatial footprint | Large spacing due to footprint and wake effects (300–500 m) | Medium spacing (150–250 m) | Small-to-medium spacing (100–200 m) |

| Anchoring/foundation | Floating structure with mooring lines | Seabed-hinged foundation | Mooring lines to seabed |

| Outline |  |  |  |

| Island | Potential Area. Scenario 1 (km2) | Available Area with 1.5 km Safety Restriction. Scenario 2 (km2) | Available Area After Applying Environmental Restrictions. Scenario 3 (km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lanzarote | 10.32 | 1.02 | 0.90 |

| Fuerteventura | 26.80 | 18.89 | 0.35 |

| Gran Canaria | 98.64 | 67.32 | 28.98 |

| Tenerife | 19.76 | 1.41 | 0.10 |

| El Hierro | 2.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SWDP | WEC | SWDP Energy Demand (GWh/Year) | Energy Coverage (%) | Area Available After Restrictions (km2) | Farm Area (km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lanzarote Island | |||||

| Diaz Rijo | WaveStar | 66.9 | 67 | 0.900 | 0.900 |

| Fuerteventura Island | |||||

| Pto. Del Rosario | WaveStar | 46.63 | 11 | 0.060 | 0.040 |

| Gran Tarajal | WaveStar | 8.03 | 100 | 0.290 | 0.064 |

| Gran Canaria Island | |||||

| Arucas-Moya | Wave Dragon | 19.16 | 100 | 2.190 | 0.021 |

| Gáldar | Wave Dragon | 11.61 | 270 | 2.270 | 0.021 |

| Guía I y II | Wave Dragon | 12.78 | 324 | 1.380 | 0.021 |

| Ayto. San Nicolás | Wave Dragon | 11.54 | 100 | 6.170 | 0.021 |

| Las Palmas III y IV | WaveStar | 97.24 | 100 | 6.040 | 0.365 |

| Maspalomas I y II | WaveStar | 46.51 | 100 | 1.810 | 0.750 |

| Sureste III | WaveStar | 38.33 | 100 | 11.730 | 0.390 |

| Salinetas | Wave Dragon | 20.44 | 100 | 1.400 | 0.021 |

| Tenerife Island | |||||

| UTE Granadilla | CorPower | 15.53 | 32 | 0.100 | 0.100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Río-Gamero, B.D.; Yánez-Rivero, A.J.; Yánez Rosales, P.; Schallenberg-Rodríguez, J. Waves as Energy Source for Desalination Plants in Islands. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122320

Río-Gamero BD, Yánez-Rivero AJ, Yánez Rosales P, Schallenberg-Rodríguez J. Waves as Energy Source for Desalination Plants in Islands. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122320

Chicago/Turabian StyleRío-Gamero, B. Del, Ancor José Yánez-Rivero, P. Yánez Rosales, and Julieta Schallenberg-Rodríguez. 2025. "Waves as Energy Source for Desalination Plants in Islands" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122320

APA StyleRío-Gamero, B. D., Yánez-Rivero, A. J., Yánez Rosales, P., & Schallenberg-Rodríguez, J. (2025). Waves as Energy Source for Desalination Plants in Islands. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122320