Response of Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton to Environmental Variables in Gwangyang Bay Focusing on the Role of Small Phytoplankton

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

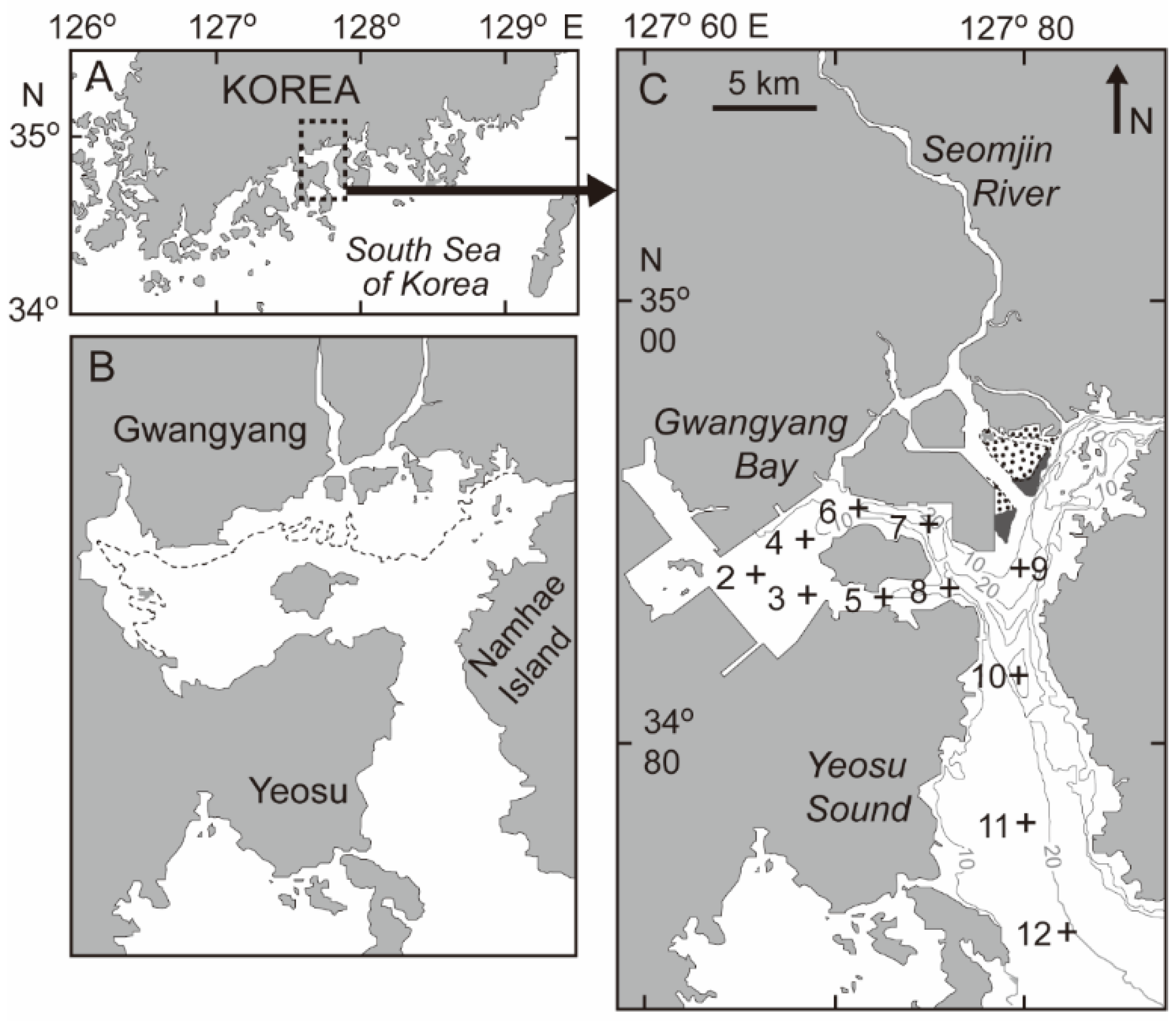

2.1. Field Surveys

2.2. Analysis of the Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton Community and Water Quality Data

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

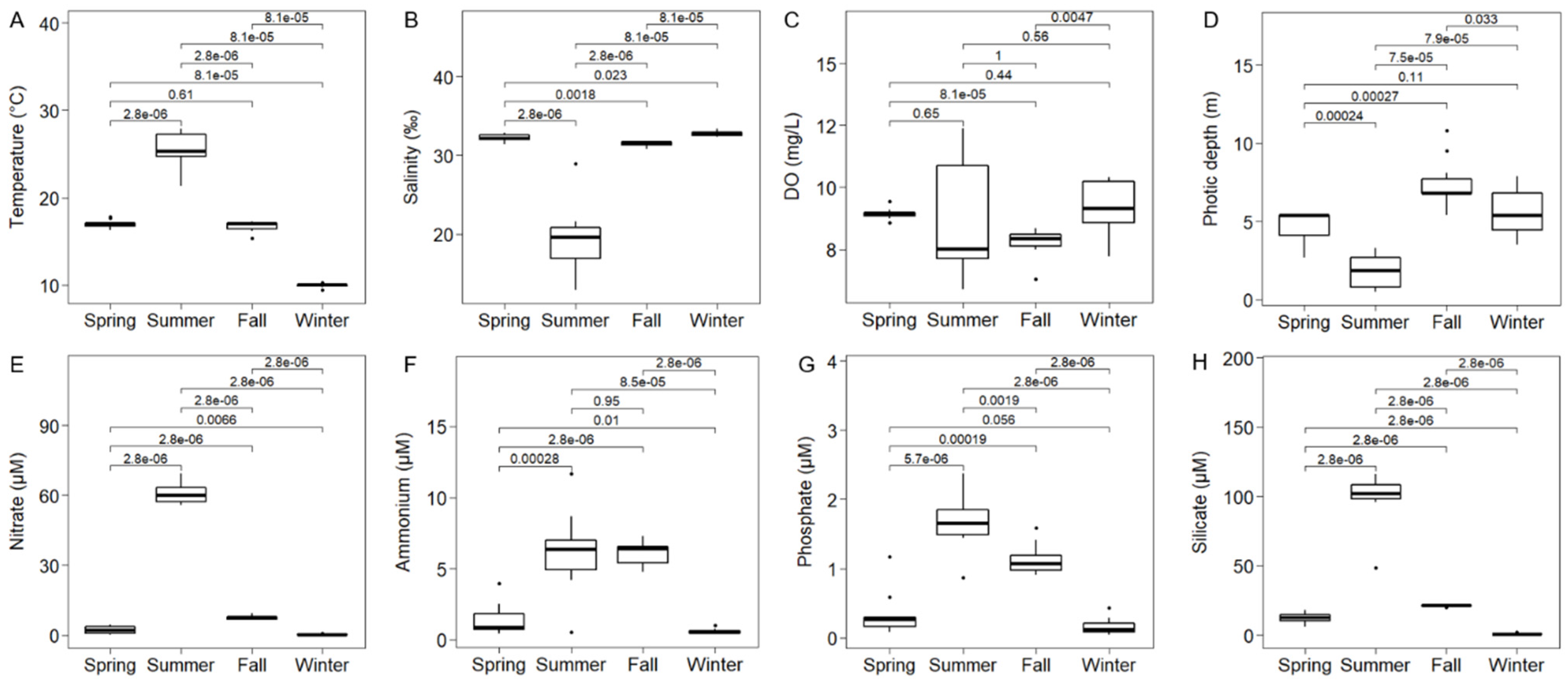

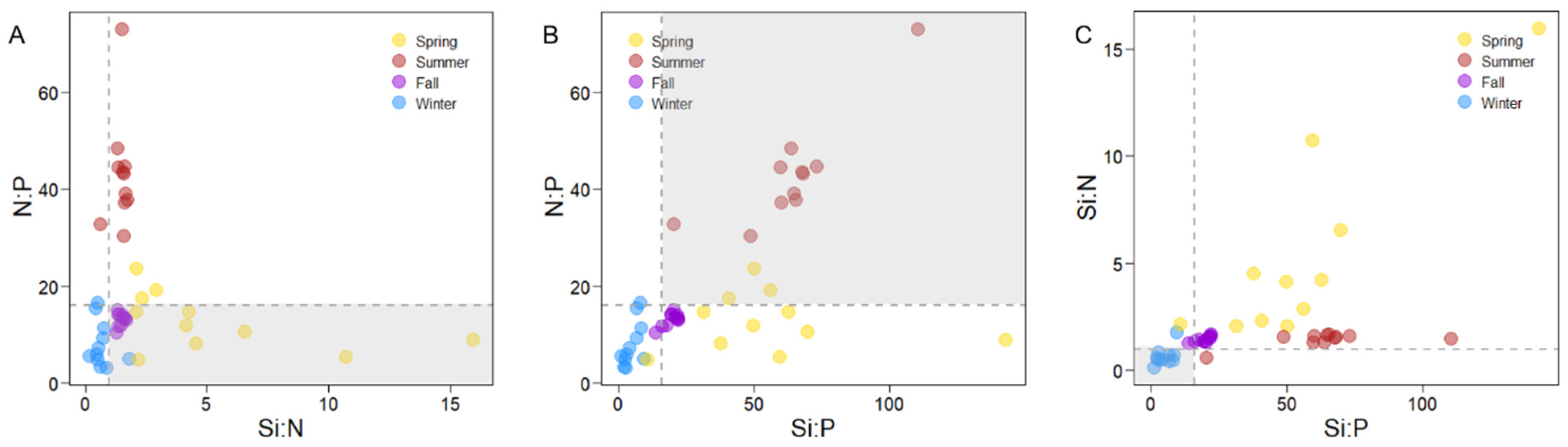

3.1. Environmental Conditions in the Water Column

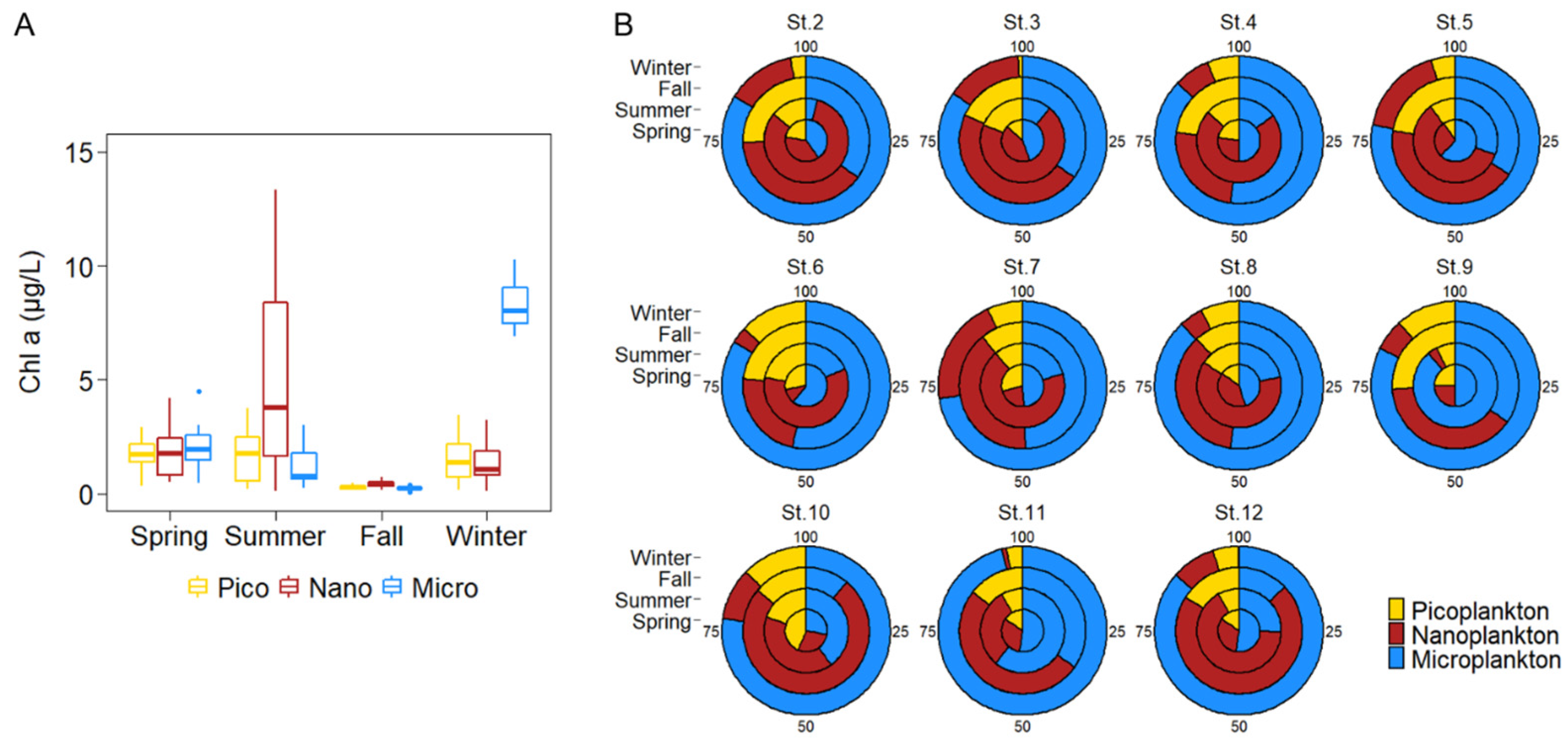

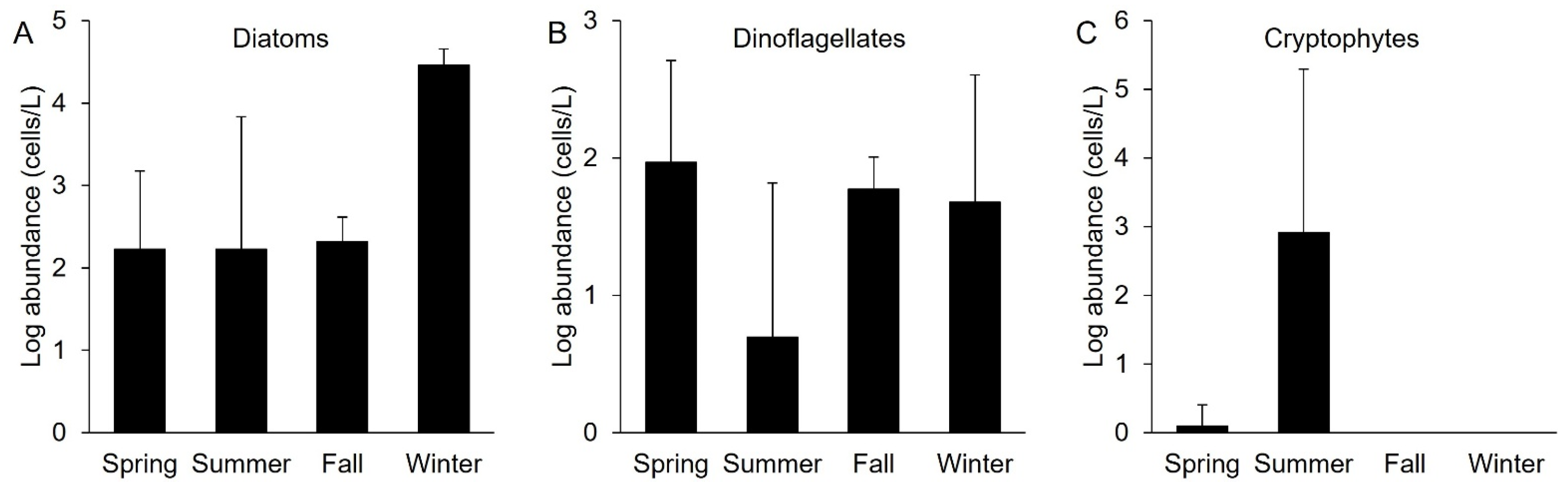

3.2. Seasonal Variation in Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton

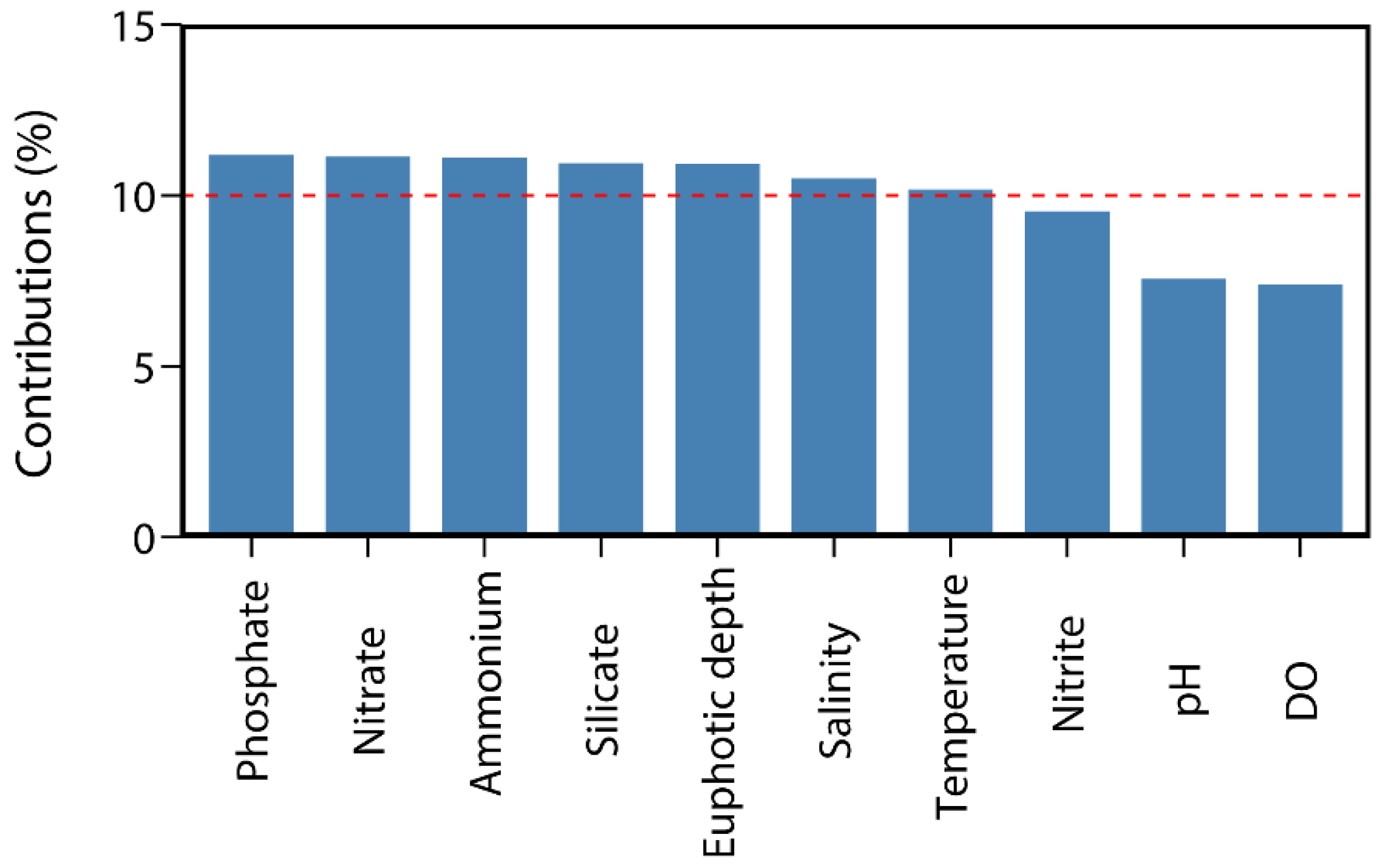

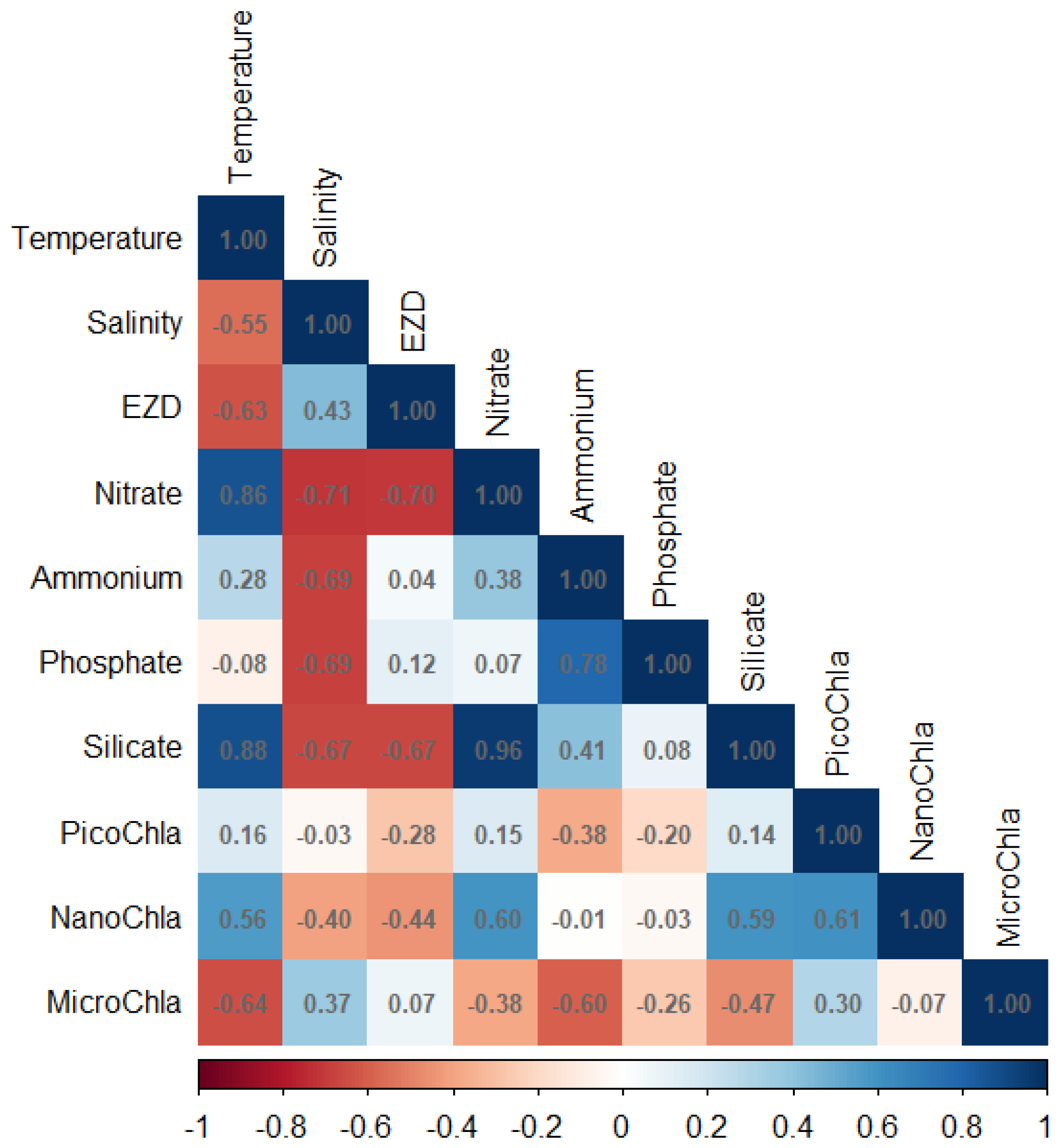

3.3. Correlation Between Environmental Variables and Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton

4. Discussion

4.1. Seasonal Variations in Environmental Variables

4.2. Characteristics of the Nanoplankton Bloom Dominated by Cryptophytes

4.3. Characteristics of the Microplankton Bloom Dominated by Diatoms

4.4. Predictable Change in the Dominant Phytoplankton Group in Gwangyang Bay

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Da, J.W., Jr.; Kemp, W.M.; Yáñez-Arancibia, A.; Crump, B.C. Estuarine Ecology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cloern, J.E.; Foster, S.; Kleckner, A. Phytoplankton primary production in the world’s estuarine-coastal ecosystems. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smayda, T.J. What is a bloom? A commentary. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1997, 42, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smayda, T.J. Adaptive ecology, growth strategies and the global bloom expansion of dinoflagellates. J. Oceanogr. 2002, 58, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smayda, T.J. Complexity in the eutrophication-harmful algal bloom relationship, with comment on the importance of grazing. Harmful Algae 2008, 8, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloern, J.E. Why large cells dominate estuarine phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2018, 63, S392–S409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaulke, A.K.; Wetz, M.S.; Paerl, H.W. Picophytoplankton: A major contributor to planktonic biomass and primary production in a eutrophic, river-dominated estuary. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2010, 90, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, A.Z.; Nolan, J.K.; Palenik, B. Assessing the dynamics and ecology of marine picophytoplankton: The importance of the eukaryotic component. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2004, 49, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Huang, B.; Zhong, C. Photosynthetic picoeukaryote assemblages in the South China Sea from the Pearl River estuary to the SEATS station. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2014, 71, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.; Taylor, W.R.; Loftus, M. Significance of nanoplankton in the Chesapeake Bay estuary and problems associated with the measurement of nanoplankton productivity. Mar. Biol. 1974, 24, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L. Picophytoplankton, nanophytoplankton, heterotrohpic bacteria and viruses in the Changjiang Estuary and adjacent coastal waters. J. Plankton Res. 2007, 29, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, J.J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, H.W.; Kang, C.K.; Lee, S.H. River discharge effects on the contribution of small-sized phytoplankton to the total biochemical composition of POM in the Gwangyang Bay, Korea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 226, 106293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Park, B.S.; Baek, S.H. Tidal influences on biotic and abiotic factors in the Seomjin River Estuary and Gwangyang Bay, Korea. Estuaries Coasts 2018, 41, 1977–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.W.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.O.; Moon, C.H.; Baek, S.H. The influences of additional nutrients on phytoplankton growth and horizontal phytoplankton community distribution during the autumn season in Gwangyang Bay, Korea. Korean J. Environ. Biol. 2014, 32, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-H.; Kim, D.; Son, M.; Yun, S.-M.; Kim, Y.-O. Seasonal distribution of phytoplankton assemblages and nutrient-enriched bioassays as indicators of nutrient limitation of phytoplankton growth in Gwangyang Bay, Korea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 163, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Oh, Y. Different roles of top-down and bottom-up processes in the distribution of size-fractionated phytoplankton in Gwangyang Bay. Water 2021, 13, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Kang, Y.-H.; Kim, J.-K.; Kang, H.Y.; Kang, C.-K. Year-to-year variation in phytoplankton biomass in an anthropogenically polluted and complex estuary: A novel paradigm for river discharge influence. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 161, 111756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.J.; Durkin, C.A.; Berthiaume, C.T.; Morales, R.L.; Armbrust, E.V. Transcriptional responses of three model diatoms to nitrate limitation of growth. Front. Mar. Sci. 2014, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolber, Z.; Zehr, J.; Falkowski, P. Effects of growth irradiance and nitrogen limitation on photosynthetic energy conversion in photosystem II. Plant Physiol. 1988, 88, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, P.M.; Glibert, P.M.; Gaeta, S.A.; Ludlam, J.M. New and regenerated production in the South Atlantic off Brazil. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1997, 44, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, W.G.; Wood, L.J.E. Inorganic nitrogen uptake by marine picoplankton: Evidence for size partitioning. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1988, 33, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chai, F.; Wells, M.L.; Liao, Y.; Li, P.; Cai, T.; Zhao, T.; Fu, F.; Hutchins, D.A. The combined effects of increased pCO2 and warming on a coastal phytoplankton assemblage: From species composition to sinking rate. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.-S.; Kim, C.-H. Interannual variability and long-term trend of coastal sea surface temperature in Korea. Ocean Polar Res. 2006, 28, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-W.; Lee, K.; Park, K.-T.; Kim, M. Sulfur hexafluoride as a complementary method for measuring the extent of point-source thermal effluents. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2008, 56, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-K.; Kwak, K.-I.; Kim, M.-W. Diffusion characteristic of surface thermal effluents in Gwangyang Bay. J. Korean Soc. Mar. Environ. Energy 2006, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, I.-C.; Kong, H.-H.; Ok, K. Seasonal Variation of Inflowing Pollutant Loads and Water Quality in Gwangyang Bay. In Conference Proceedings of The Korean Society for Marine Environment & Energy. pp. 82–87. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/pdf/pdfView.do?nodeId=NODE01012090&width=1920 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Kim, H.-J.; Yeong Park, J.; Ho Son, M.; Moon, C.-H. Long-Term Variations of Phytoplankton Community in Coastal Waters of Kyoungju city Area. Korea Soc. Fish. Mar. Sci. Educ. 2016, 28, 1417–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welschmeyer, N.A. Fluorometric analysis of chlorophyll-a in the presence of chlorophyll-b and pheopigments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1994, 39, 1985–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnes, D.J.S.; Berges, J.A.; Harrison, P.J.; Taylor, F.J.R. Estimating carbon, nitrogen, protein, and chlorophyll a from volum in marine phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1994, 39, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobler, C.J.; Koch, F.; Kang, Y.; Berry, D.L.; Tang, Y.Z.; Lasi, M.; Walters, L.; Hall, L.; Miller, J.D. Expansion of harmful brown tides caused by the pelagophyte, Aureoumbra lagunensis DeYoe et Stockwell, to the US East Coast. Harmful Algae 2013, 27, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.N. Nitrate reduction by shaking with cadmium—Alternative to cadmium columns. Water Res. 1984, 18, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T.R.; Maita, Y.; Lalli, C.M. A Manual of Chemical and Biological Methods for Seawater Analysis; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, N.; Harrison, P. Comparison of methods for the analysis of dissolved urea in seawater. Mar. Biol. 1987, 94, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloern, J.E. Turbidity as a control on phytoplankton biomass and productivity in estuaries. Cont. Shelf Res. 1987, 7, 1367–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, H.; Atkins, W. Photo-electric measurements of submarine illumination throughout the year. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 1929, 16, 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezinski, M.A. The Si:C:N ratio of marine diatoms: Interspecific variability and the effect of some environmental variables. J. Phycol. 1985, 21, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.-Y.; Moon, C.-H.; Kang, C.-K.; Kim, Y.-N. Distribution of particulate organic matters along the salinity gradients in the Seomjin River estuary. J. Korean Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2002, 35, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.I.; Park, C.K.; Cho, H.S. Ecological modeling for water quality management of Kwangyang Bay, Korea. J. Environ. Manag. 2005, 74, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.I.; Cho, H.S.; Cho, C.R.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, J.H.; Choi, M.H.; Kim, D.H.; Yoon, J.S. Pollution Sources and Temporal Variations of Pollutant Loads in Kwangyang Bay Watershed. In Conference Proceedings of The Korean Society for Marine Environment & Energy. pp. 201–208. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/pdf/pdfView.do?nodeId=NODE00856534&width=1920 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Clay, B.L.; Kugrens, P.; Lee, R.E. A revised classification of Cryptophyta. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1999, 131, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaveness, D. Biology and ecology of the Cryptophyceae: Status and challenges. Biol. Oceanogr. 1989, 6, 257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.D.; Beaudoin, D.J.; Frada, M.J.; Brownlee, E.F.; Stoecker, D.K. High grazing rates on cryptophyte algae in Chesapeake Bay. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.D.; Seong, K.A.; Jeong, H.J.; Yih, W.; Rho, J.-R.; Nam, S.W.; Kim, H.S. Mixotrophy in the marine red-tide cryptophyte Teleaulax amphioxeia and ingestion and grazing impact of cryptophytes on natural populations of bacteria in Korean coastal waters. Harmful Algae 2017, 68, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujcic, V.; Nuy, J.K.; Salcher, M.M.; Shabarova, T.; Kasalicky, V.; Boenigk, J.; Jensen, M.; Simek, K. Cryptophyta as major bacterivores in freshwater summer plankton. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1668–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.H.; Shin, Y.K.; Lee, W.H. On the phyroplankton distribution in the Kwangyang Bay. J. Korean Soc. Oceanogr. 1984, 19, 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Shiah, F.-K.; Ducklow, H.W. Temperature and substrate regulation of bacterial abundance, production and specific growth rate in Chesapeake Bay, USA. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1994, 103, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, R.; Naselli-Flores, L. Distribution and seasonal dynamics of Cryptomonads in Sicilian water bodies. Hydrobiologia 2003, 502, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugdale, R.; Wilkerson, F.; Parker, A.E.; Marchi, A.; Taberski, K. River flow and ammonium discharge determine spring phytoplankton blooms in an urbanized estuary. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2012, 115, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šupraha, L.; Bosak, S.; Ljubešić, Z.; Mihanović, H.; Olujić, G.; Mikac, I.; Viličić, D. Cryptophyte bloom in a Mediterranean estuary: High abundance of Plagioselmis cf. prolonga in the Krka River estuary (eastern Adriatic Sea). Sci. Mar. 2014, 78, 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bazin, P.; Jouenne, F.; Deton-Cabanillas, A.-F.; Pérez-Ruzafa, Á.; Véron, B. Complex patterns in phytoplankton and microeukaryote diversity along the estuarine continuum. Hydrobiologia 2014, 726, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, K.; Jokinen, S. Flagellate grazing on bacteria in a small dystrophic lake. In Flagellates in Freshwater Ecosystems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; pp. 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Kang, H.-Y.; Kim, D.; Lee, Y.-J.; Kim, T.-I.; Kang, C.-K. Temperature-dependent bifurcated seasonal shift of phytoplankton community composition in the coastal water off southwestern Korea. Ocean Sci. J. 2019, 54, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.H.; Lee, M.; Park, B.S.; Lim, Y.K. Variation in phytoplankton community due to an autumn typhoon and winter water turbulence in southern Korean coastal waters. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T.; Hori, Y.; Nagai, S.; Miyahara, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Harada, K.; Tada, K.; Imai, I. Long time-series observations in population dynamics of the harmful diatom Eucampia zodiacus and environmental factors in Harima-Nada, eastern Seto Inland Sea, Japan during 1974–2008. Plankton Benthos Res. 2011, 6, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, T.; Yamaguchi, M. Effect of temperature on light-limited growth of the harmful diatom Eucampia zodiacus Ehrenberg, a causative organism in the discoloration of Porphyra thalli. Harmful Algae 2006, 5, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Katano, T.; Fujii, N.; Koriyama, M.; Yoshino, K.; Hayami, Y. Decreases in turbidity during neap tides initiate late winter blooms of Eucampia zodiacus in a macrotidal embayment. J. Oceanogr. 2013, 69, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dortch, Q.; Whitledge, T.E. Does nitrogen or silicon limit phytoplankton production in the Mississippi River plume and nearby regions? Cont. Shelf Res. 1992, 12, 1293–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloern, J.E. Tidal stirring and phytoplankton bloom dynamics in an estuary. J. Mar. Res. 1991, 49, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, Y.M.; Chant, R.J.; Reinfelder, J.R. Factors Controlling Seasonal Phytoplankton Dynamics in the Delaware River Estuary: An Idealized Model Study. Estuaries Coasts 2019, 42, 1839–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glibert, P.M.; Wilkerson, F.P.; Dugdale, R.C.; Raven, J.A.; Dupont, C.L.; Leavitt, P.R.; Parker, A.E.; Burkholder, J.M.; Kana, T.M. Pluses and minuses of ammonium and nitrate uptake and assimilation by phytoplankton and implications for productivity and community composition, with emphasis on nitrogen-enriched conditions. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2016, 61, 165–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.E.; Dugdale, R.C.; Wilkerson, F.P. Elevated ammonium concentrations from wastewater discharge depress primary productivity in the Sacramento River and the Northern San Francisco Estuary. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spetter, C.V.; Popovich, C.A.; Arias, A.; Asteasuain, R.O.; Freije, R.H.; Marcovecchio, J.E. Role of nutrients in phytoplankton development during a winter diatom bloom in a eutrophic South American estuary (Bahía Blanca, Argentina). J. Coast. Res. 2015, 31, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Kang, C.-K.; Choi, Y.-K.; Lee, S.-Y. Origin and spatial distribution of organic matter at Gwangyang Bay in the Fall. J. Korean Soc. Oceanogr. 2007, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-J.; Lee, H.-I.; Kim, D.-C.; Shin, I.-C. Changes in sedimentary process by POSCO’s dredging and reclaming in the Kwangyang Bay. In Conference Proceedings of Journal of the Korean Society for Marine Environmental Engineering 2000. pp. 61–65. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/pdf/pdfView.do?nodeId=NODE00850729&width=1920 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Hyun, J.-H.; Choi, K.-S.; Lee, K.-S.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Kang, C.-K. Climate Change and Anthropogenic Impact Around the Korean Coastal Ecosystems: Korean Long-term Marine Ecological Research (K-LTMER). Estuaries Coasts 2020, 43, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, C.D.G.; Randall Hughes, A.; Hultgren, K.M.; Miner, B.G.; Sorte, C.J.B.; Thornber, C.S.; Rodriguez, L.F.; Tomanek, L.; Williams, S.L. The impacts of climate change in coastal marine systems. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jeon, J.; Kwak, M.S.; Kim, G.H.; Koh, I.; Rho, M. Photosynthetic functions of Synechococcus in the ocean microbiomes of diverse salinity and seasons. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Lee, P.; Cheung, S.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H. Discovery of Euryhaline Phycoerythrobilin-Containing Synechococcus and Its Mechanisms for Adaptation to Estuarine Environments. mSystems 2020, 5, e00842-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, E.; Kwon, C.-W.; Kang, C.-K.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, J.; Kang, Y. Response of Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton to Environmental Variables in Gwangyang Bay Focusing on the Role of Small Phytoplankton. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122298

Lee E, Kwon C-W, Kang C-K, Kim CS, Lee J, Kang Y. Response of Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton to Environmental Variables in Gwangyang Bay Focusing on the Role of Small Phytoplankton. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122298

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Eunbi, Chan-Woo Kwon, Chang-Keun Kang, Chan Song Kim, Jiyoung Lee, and Yoonja Kang. 2025. "Response of Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton to Environmental Variables in Gwangyang Bay Focusing on the Role of Small Phytoplankton" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122298

APA StyleLee, E., Kwon, C.-W., Kang, C.-K., Kim, C. S., Lee, J., & Kang, Y. (2025). Response of Size-Fractionated Phytoplankton to Environmental Variables in Gwangyang Bay Focusing on the Role of Small Phytoplankton. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2298. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122298