Study of Ice Load on Hull Structure Based on Full-Scale Measurements in Bohai Sea

Abstract

1. Introduction

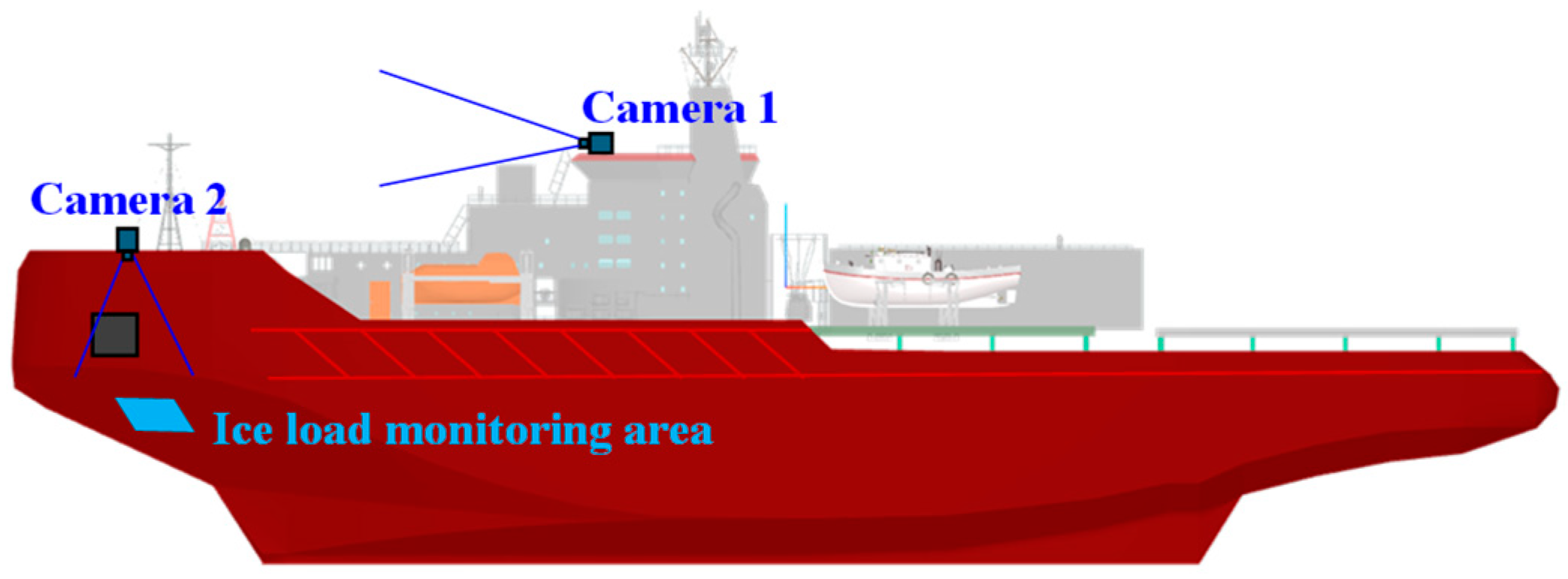

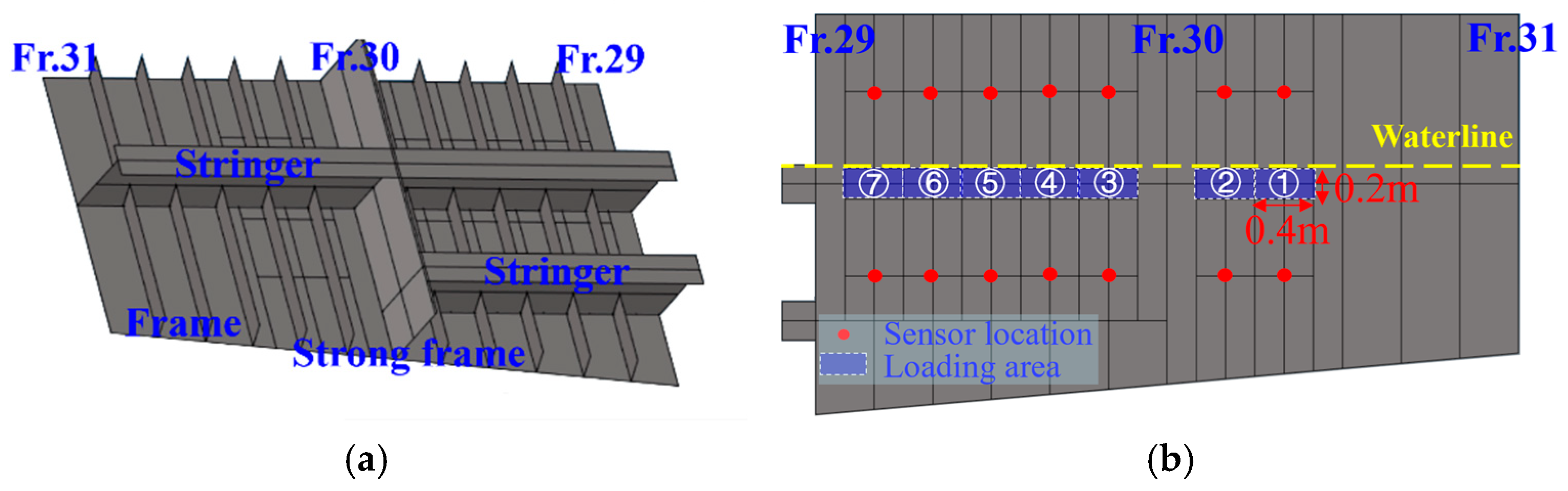

2. Instrumentation of Full-Scale Measurement

2.1. Ice Load Measurement System

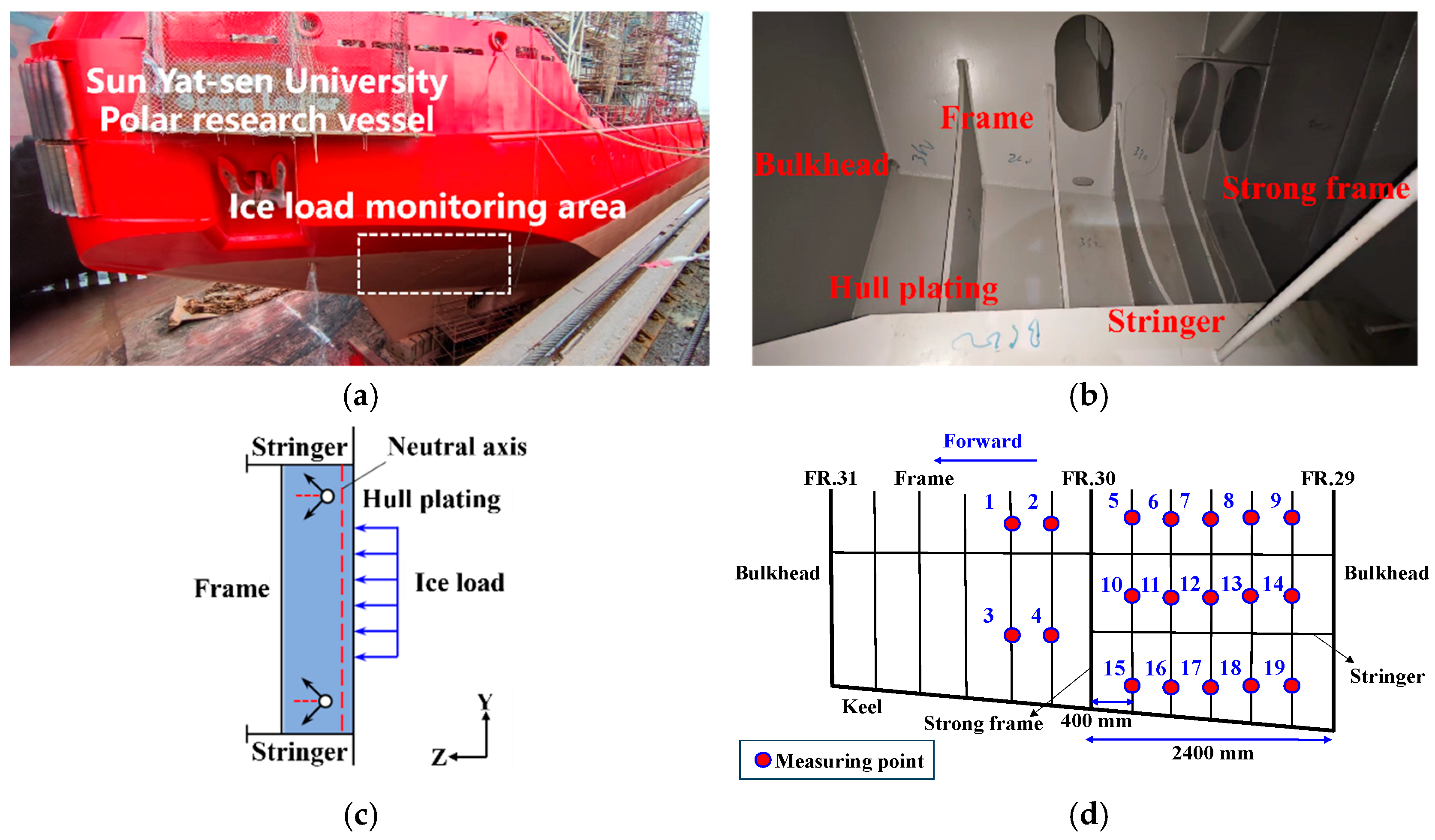

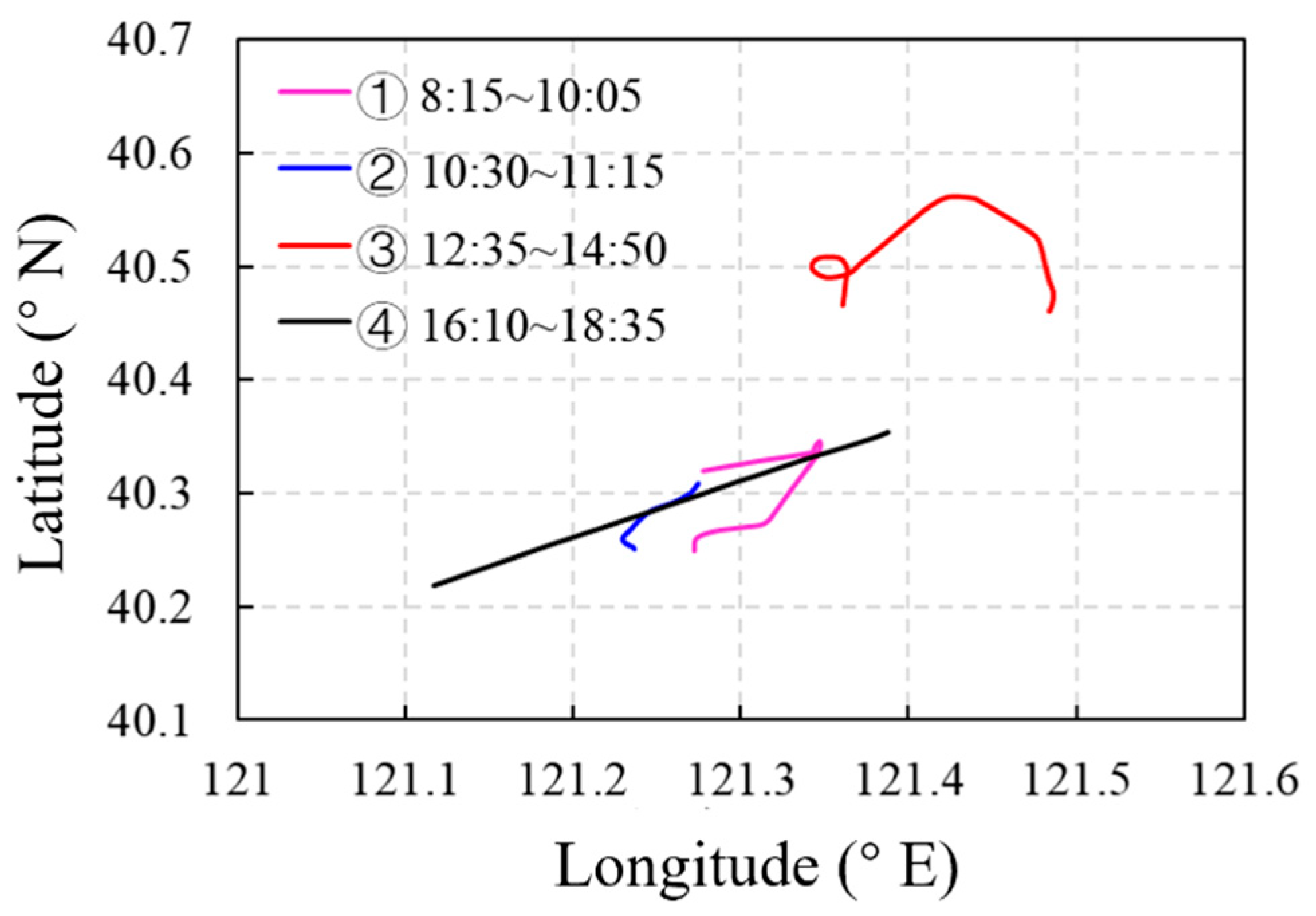

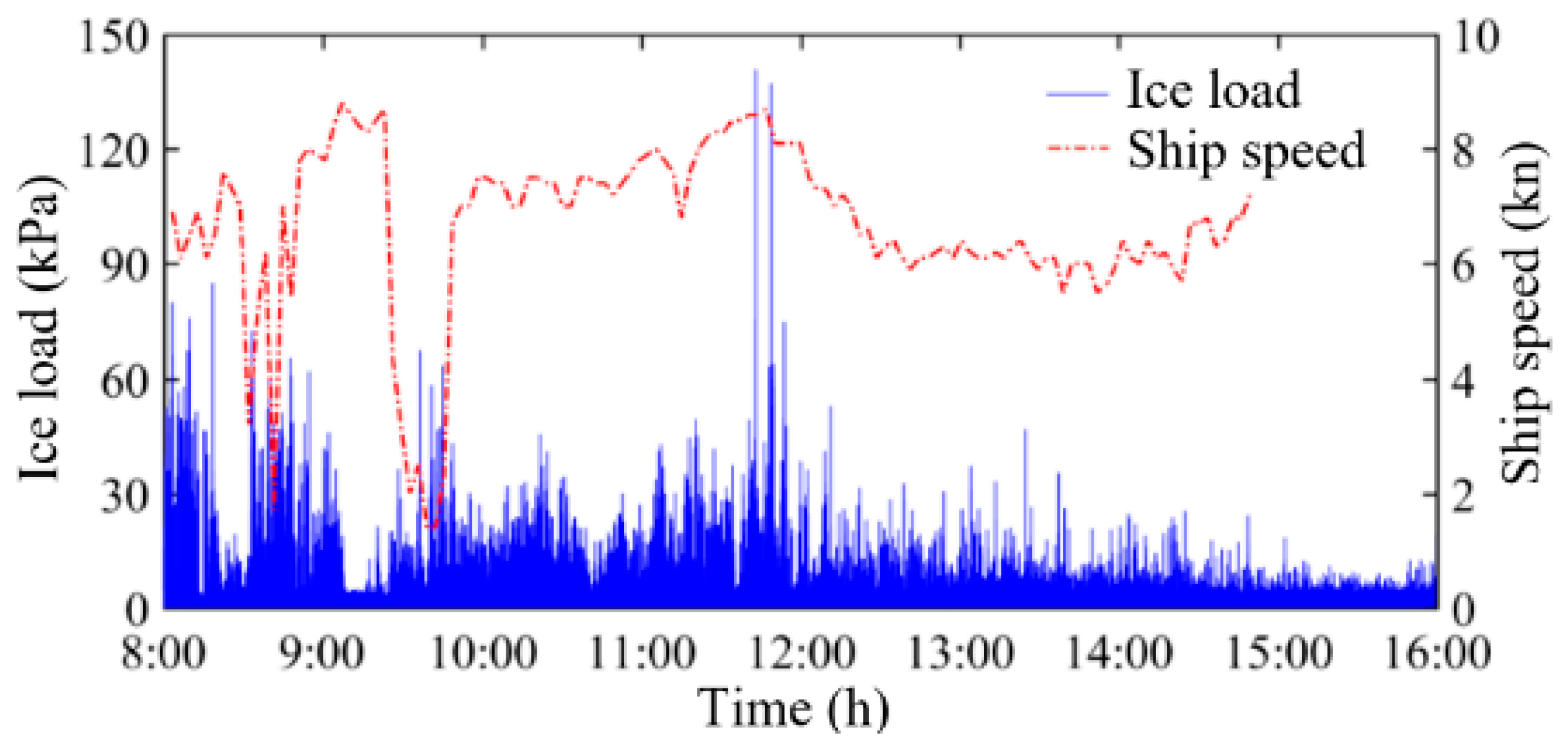

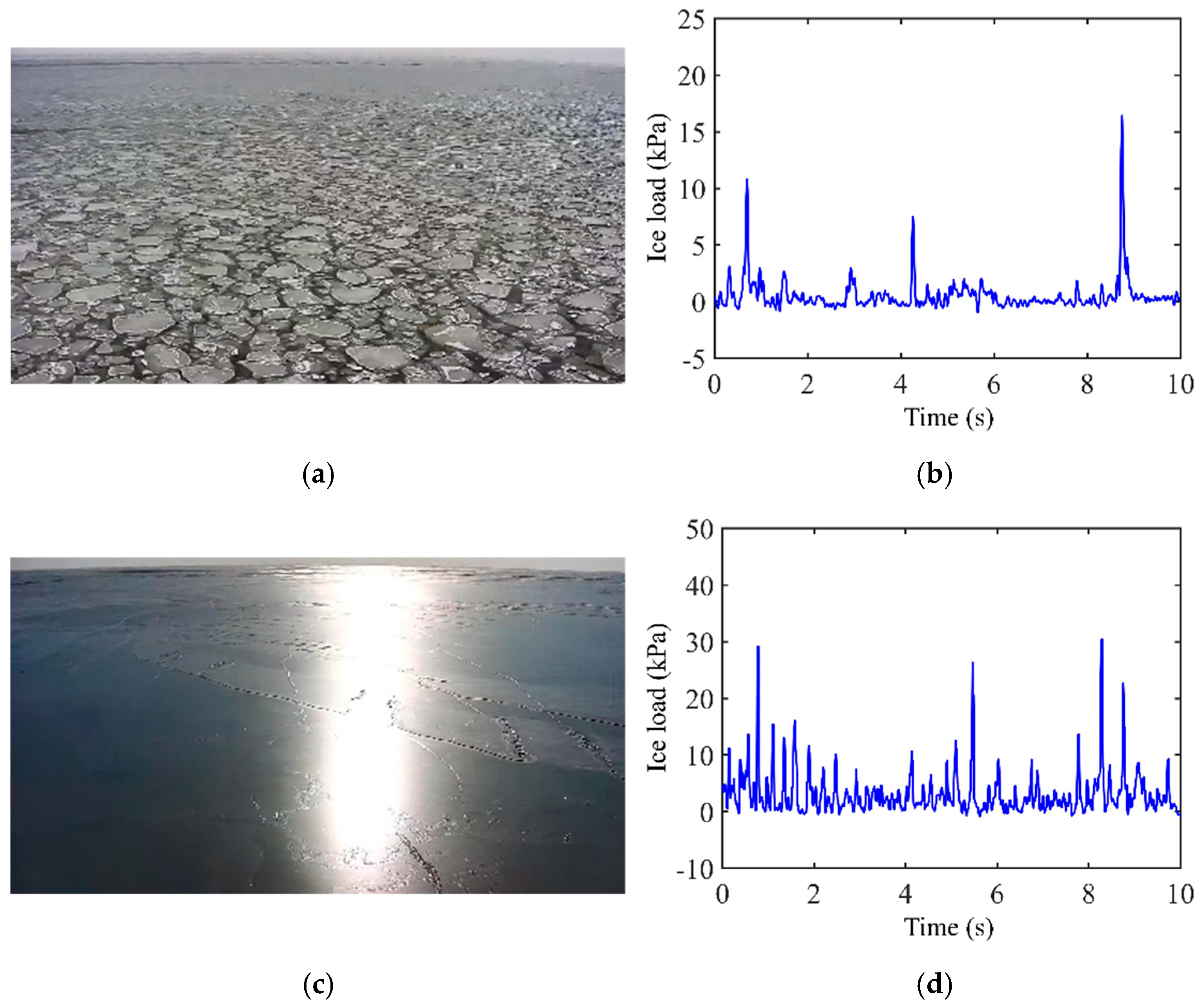

2.2. Route and Ice Condition

3. Ice Load Identification Method

3.1. Principle of the ICM Method

3.2. Construction of the Ice Load Identification Model

3.2.1. Ice-Induced Strain Signal Preprocessing

3.2.2. Construction of the Influence Coefficient Matrix

3.3. Identification Results of Ice Loads

4. Characteristics of Ice Load

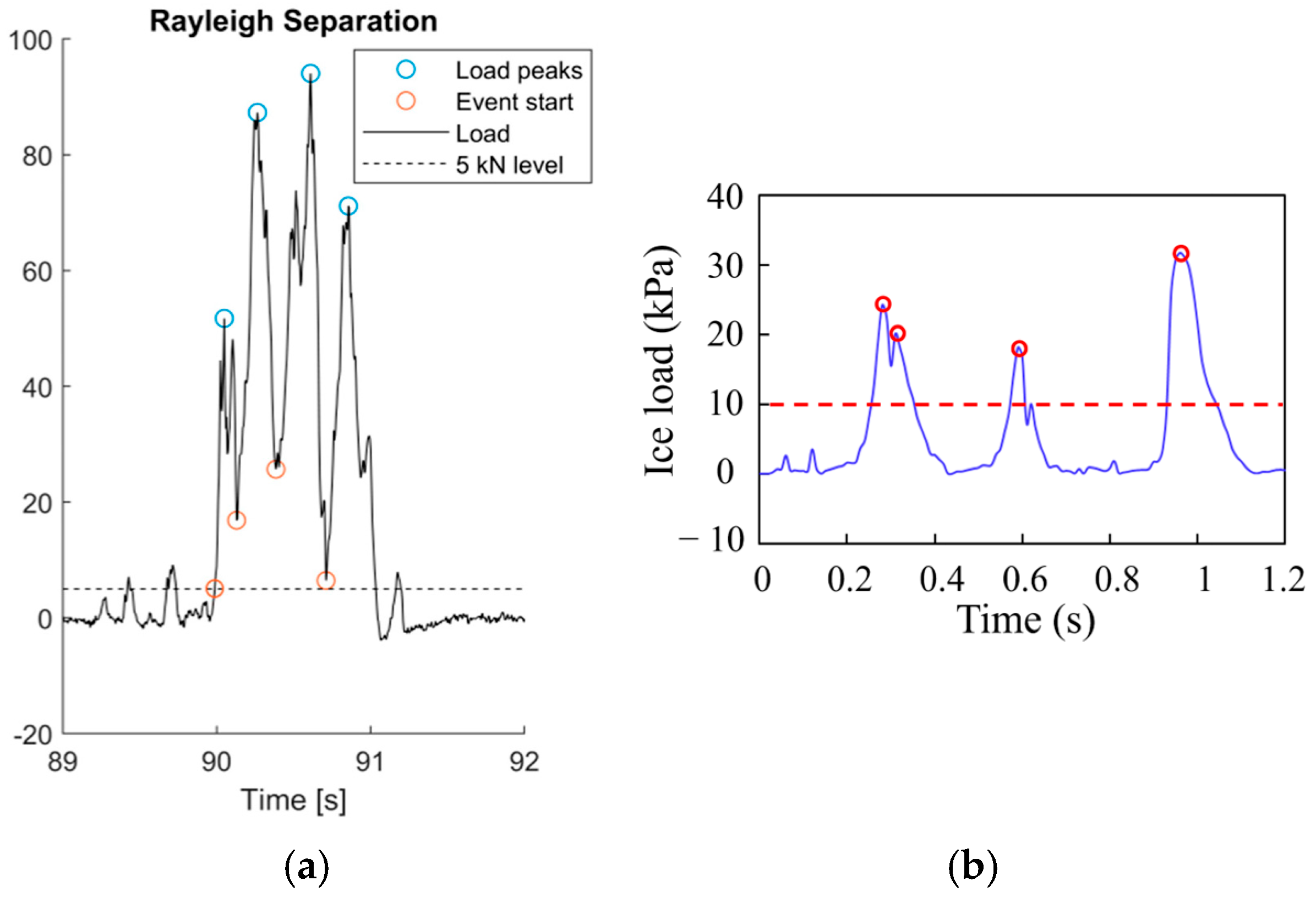

4.1. Determination of Ice Load Event

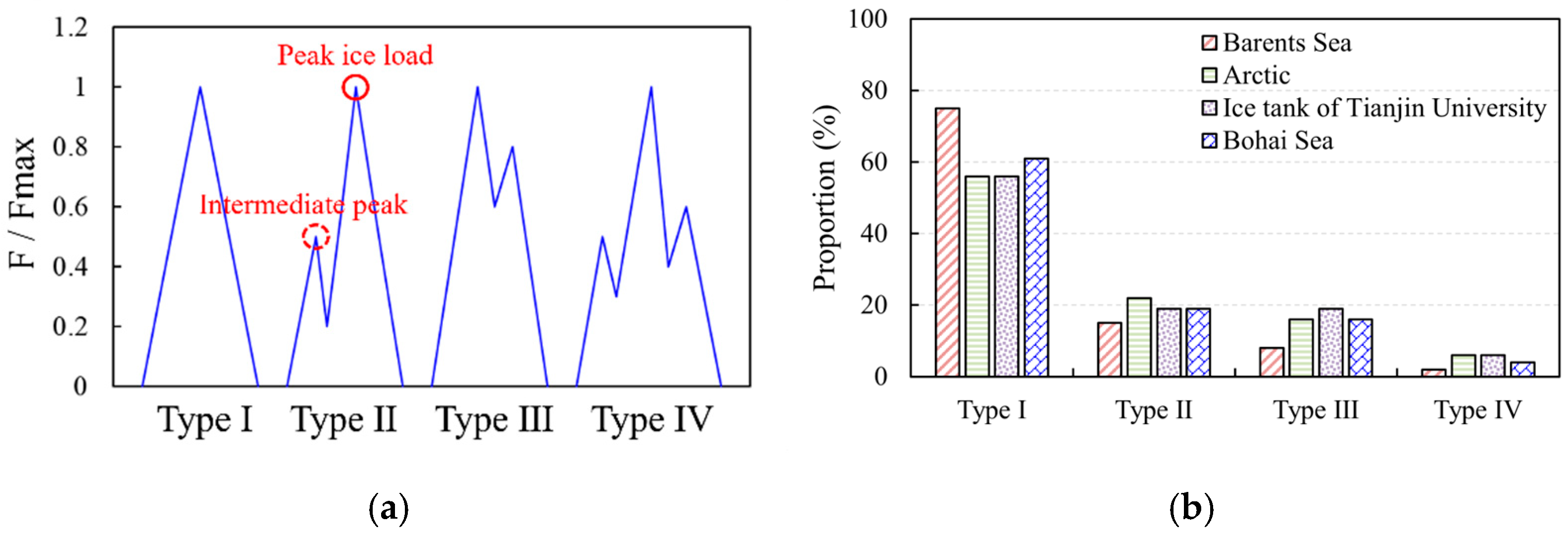

4.2. Characteristics of Ice Load Time-History Curves

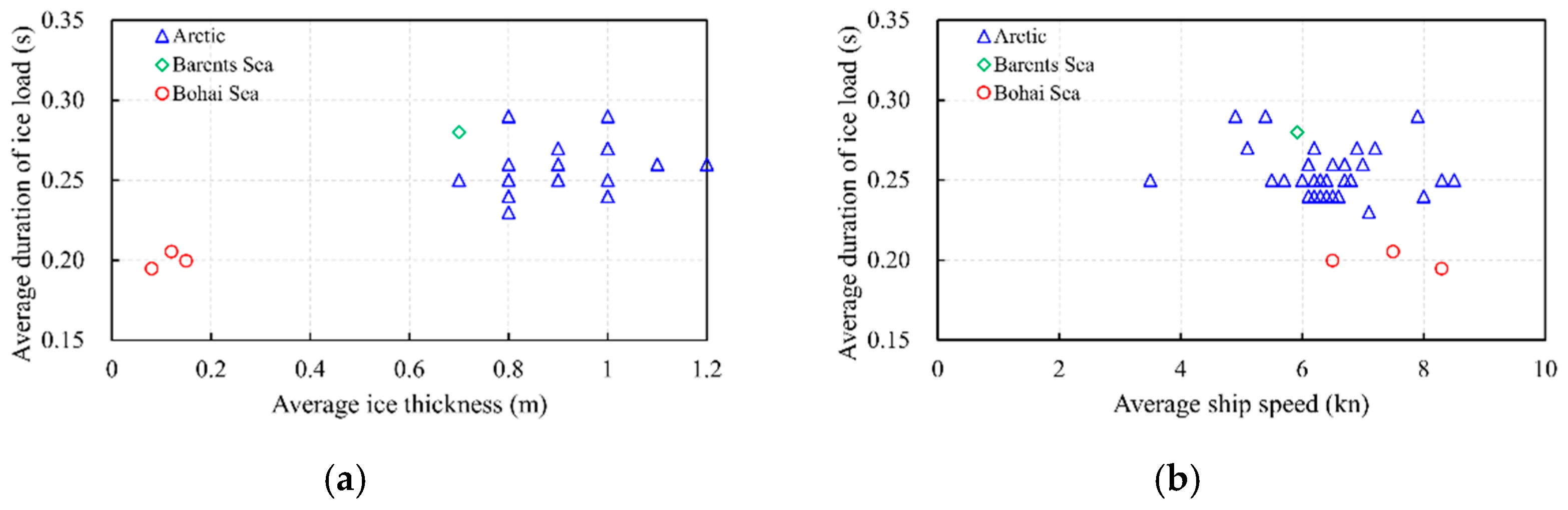

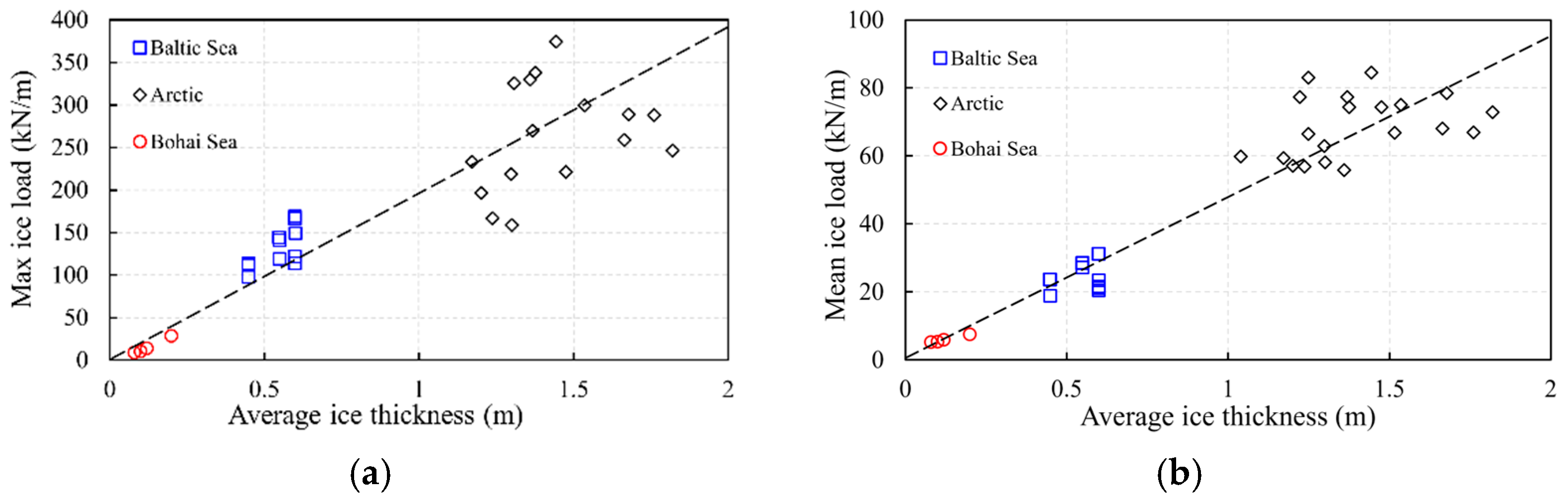

4.3. Characteristics of Ice Loads Periods and Peak Values

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The time-domain characteristics of the measured ice load time histories in the Bohai Sea ice area were similar to those in icy areas of the polar sea, the load periods and peaks are consistent with the measurements from the Arctic cruise.

- (2)

- The action period of ice loads in the Bohai Sea followed the same relationship as that obtained from full-scale ship tests in polar regions, i.e., the action period of ice loads is positively correlated with ice thickness but is not significantly affected by ship speed;

- (3)

- Both the maximum and average values of ice load peaks in the Bohai Sea conformed to the same relationship between ice load peaks and average ice thickness established in other sea areas.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ebinger, C.K.; Zambetakis, E. The geopolitics of Arctic melt. Int. Aff. 2009, 85, 1215–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, G. A straightforward method for calculation of ice resistance of ships. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference Port and Ocean Engineering Under Arctic Conditions (POAC 1989), Luleå, Sweden, 12–16 June 1989; pp. 722–735. [Google Scholar]

- Riska, K.; Wilhelmson, M.; Englund, K.; Leiviskä, T. Performance of Merchant Vessels in Ice in the Baltic, Winter Navigation Research Board; Finnish Maritime Administration: Helsinki, Finland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lilja, V.P.; Polojärvi, A.; Tuhkuri, J.; Paavilainen, P. A free, square, point-loaded ice sheet: A finite element-discrete element approach. Mar. Struct. 2019, 68, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Riska, K.; Moan, T. A numerical method for the prediction of ship performance in level ice. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2010, 60, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksnes, V. A simplified interaction model for moored ships in level ice. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2010, 63, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Riska, K.; Polach, R.B.; Moan, T.; Su, B. Experiments on level ice loading on an icebreaking tanker with different ice drift angles. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2013, 85, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polach, R.B.; Ehlers, S. Heave and pitch motions of a ship in model ice: An experimental study on ship resistance and ice breaking pattern. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2011, 68, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotovirta, V.; Karvonen, J.; Polach, R.B.; Berglund, R.; Kujala, P. Ships as a sensor network to observe ice field properties. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2011, 65, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, F.; McKenna, R.; Gagnon, R. Iceberg characterization for the bergy bit impact study. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2008, 52, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyuthi, A.; Leira, B.; Riska, K. Short term extreme statistics of local ice loads on ship hulls. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2012, 82, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksen, Ø. Ice-Induced Loading on Ship Hull During Ramming. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Goerlandt, F.; Kujala, P.; Lehtiranta, J.; Lensu, M. Evaluation of selected state-of-the-art methods for ship transit simulation in various ice conditions based on full-scale measurement. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 151, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leira, B.; Børsheim, L.; Espeland, Ø.; Amdahl, J. Ice-load estimation for a ship hull based on continuous response monitoring. J. Eng. Marit. Environ. 2009, 223, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyuthi, A.; Leira, B.; Riska, K. A generalized probabilistic model of ice load peaks on ship hulls in broken-ice fields. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2014, 97, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suominen, M.; Kujala, P.; Romanoff, J.; Remes, H. Influence of load length on short-term ice load statistics in full-scale. Mar. Struct. 2017, 52, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotilainen, M.; Vanhatalo, J.; Suominen, M.; Kujala, P. Predicting ice-induced load amplitudes on ship bow conditional on ice thickness and ship speed in the Baltic Sea. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2017, 135, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritch, R.; Frederking, R.; Johnston, M.; Browne, R.; Ralph, F. Local ice pressures measured on a strain gauge panel during the CCGS Terry Fox bergy bit impact study. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2008, 52, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takimoto, T.; Uto, S.; Oka, S.; Murakami, C.; Izumiyama, K. Mearsurement of ice load exerted on the hull of icebreaker SOYA in the southern sea of Okhotsk. In Proceedings of the 18th IAHR International Symposium on Ice, Sapporo, Japan, 28 August–1 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, Y.; Mizuno, S.; Tsukuda, H. The Icebreaking Performance of SHIRASE in the Maiden Antarctic Voyage. In Proceedings of the Twenty-First International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference, Maui, HI, USA, 19–24 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Kwon, Y.H.; Rim, C.W.; Lee, T.K. Characteristics analysis of local ice load signals in ice-covered water. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2016, 8, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.H.; Lee, T.K.; Choi, K. A study on measurements of local ice pressure for ice breaking research vessel “Araon” at the Amundsen Sea. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2015, 7, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Min, J.K.; Choi, K.; Ha, J.S. Estimation of local ice load by analyzing shear strain data for the IBRV Araon. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Port and Ocean Engineering Under Arctic Conditions, Busan, Republic of Korea, 11–16 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, K.; Ji, S. Far-field identification of ice loads on ship structures by radial basis function neural network. Ocean Eng. 2023, 282, 115072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chen, X.; Kong, S. Measurement and identification of ice loads on hull structures in far field based on dynamic effects. Chin. J. Ship Res. 2021, 16, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Sun, L.; Pang, F.; Li, H.; Gao, C. Experimental research of hull vibration of a full-scale river icebreaker. J. Mar. Sci. App. 2020, 19, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, A.; Ji, S. Comparative study of the brittle-ductile transition between level ice and rafted ice based on uniaxial compression experiments. Int. J. Mater. Struct. Integr. 2021, 14, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Liu, H.; Li, P.; Su, J. Experimental Studies on the Bohai Sea Ice Shear Strength. J. Cold Reg. 2013, 27, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q.; Bi, X. Ice-Induced Jacket Structure Vibrations in Bohai Sea. J. Cold Reg. 2000, 14, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenz, D.; Younan, A.; Piercey, G.; Barrett, J.; Ralph, F.; Jordaan, I. Field measurement of the reduction in local pressure from ice management. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 156, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Choi, J.; Park, S.; Han, S. Sensor arrangement for ice load monitoring to estimate local ice load in Arctic vessel. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Port and Ocean Engineering Under Arctic Conditions, Busan, Republic of Korea, 11–16 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Shi, Q.; Song, A.; Fan, Y.; Li, T. Sea Ice Engineering in China. J. Coast. Res. 1991, 7, 759–770. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, M.A.; Tuhkuri, J.; Lensu, M. Rafting and ridging of thin ice sheets. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 1999, 104, 13605–13613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suominen, M.; Li, F.; Lu, L.; Kujala, P.; Bekker, A.; Lehtiranta, J. Effect of maneuvering on ice-induced loading on ship hull: Dedicated full-scale tests in the Baltic Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yuan, K.; Ji, S. Method of monitoring and identifying ice load on ship structures and analysis of its spatial-temporal characteristics. Shipbuild. Chin. 2023, 64, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suominen, M.; Kujala, P. Variation in short-term ice-induced load amplitudes on a ship’s hull and related probability distributions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2014, 106, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component Name | Parameter | Value/mm |

|---|---|---|

| Hull plating | Thickness | 40 |

| Stringer | Web height × Flange width × Web thickness × Flange thickness | 700 × 50 × 20 × 26 |

| Strong frame | Web thickness | 20 |

| Ordinary frame | Web height × Web thickness | 340 × 21 |

| Ordinary frame spacing | 400 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, G.; Zhao, C.; Xia, X.; Lin, R.; He, S.; Chen, X.; Ji, S. Study of Ice Load on Hull Structure Based on Full-Scale Measurements in Bohai Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122297

Zhao G, Zhao C, Xia X, Lin R, He S, Chen X, Ji S. Study of Ice Load on Hull Structure Based on Full-Scale Measurements in Bohai Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122297

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Guanhui, Cuina Zhao, Xiang Xia, Rui Lin, Shuaikang He, Xiaodong Chen, and Shunying Ji. 2025. "Study of Ice Load on Hull Structure Based on Full-Scale Measurements in Bohai Sea" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122297

APA StyleZhao, G., Zhao, C., Xia, X., Lin, R., He, S., Chen, X., & Ji, S. (2025). Study of Ice Load on Hull Structure Based on Full-Scale Measurements in Bohai Sea. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122297