Dissimilar Welded Joints and Sustainable Materials for Ship Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

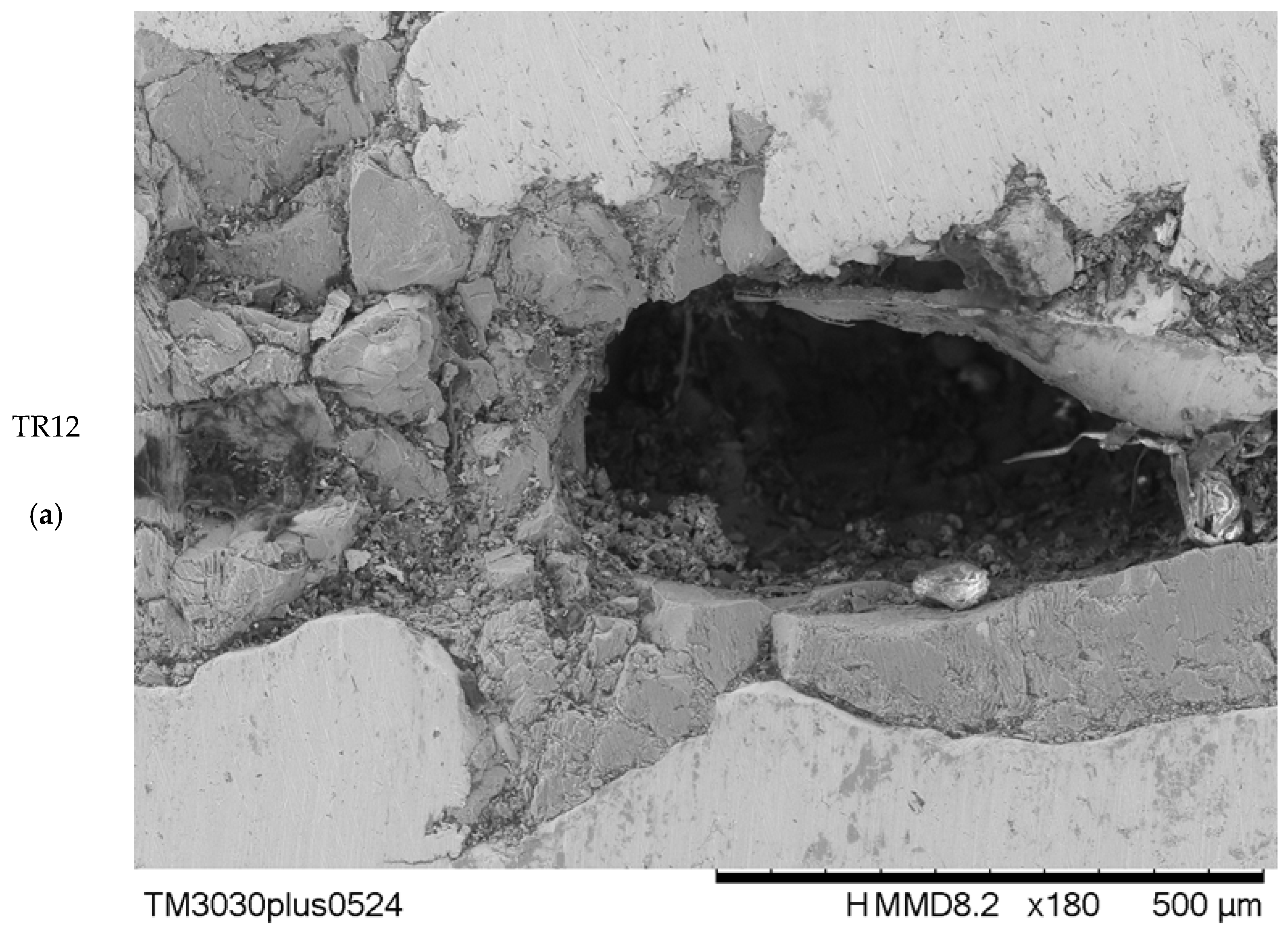

- The bond, formed by high-velocity impact and pressure, is mechanical–metallurgical;

- There is no melting and no heat-affected zone;

- A pure aluminium interlayer is often incorporated, acting as a galvanic barrier in saline conditions;

- The characteristic wavy interface increases bonded area and enhances mechanical interlocking, thereby impeding the ingress of moisture and aggressive species;

- A porosity-free bond resists seawater penetration.

- EXW produces high material efficiency, but elevated CO2 emissions and excessive noise levels raise environmental and occupational safety concerns.

- The FSW process involves low emissions, minimal scrap, and moderate energy use, confirming FSW as a clean and efficient method.

- MIG welding offers balanced material efficiency and moderate emissions, with a practical compromise between performance and environmental impact.

2. Materials and Methods

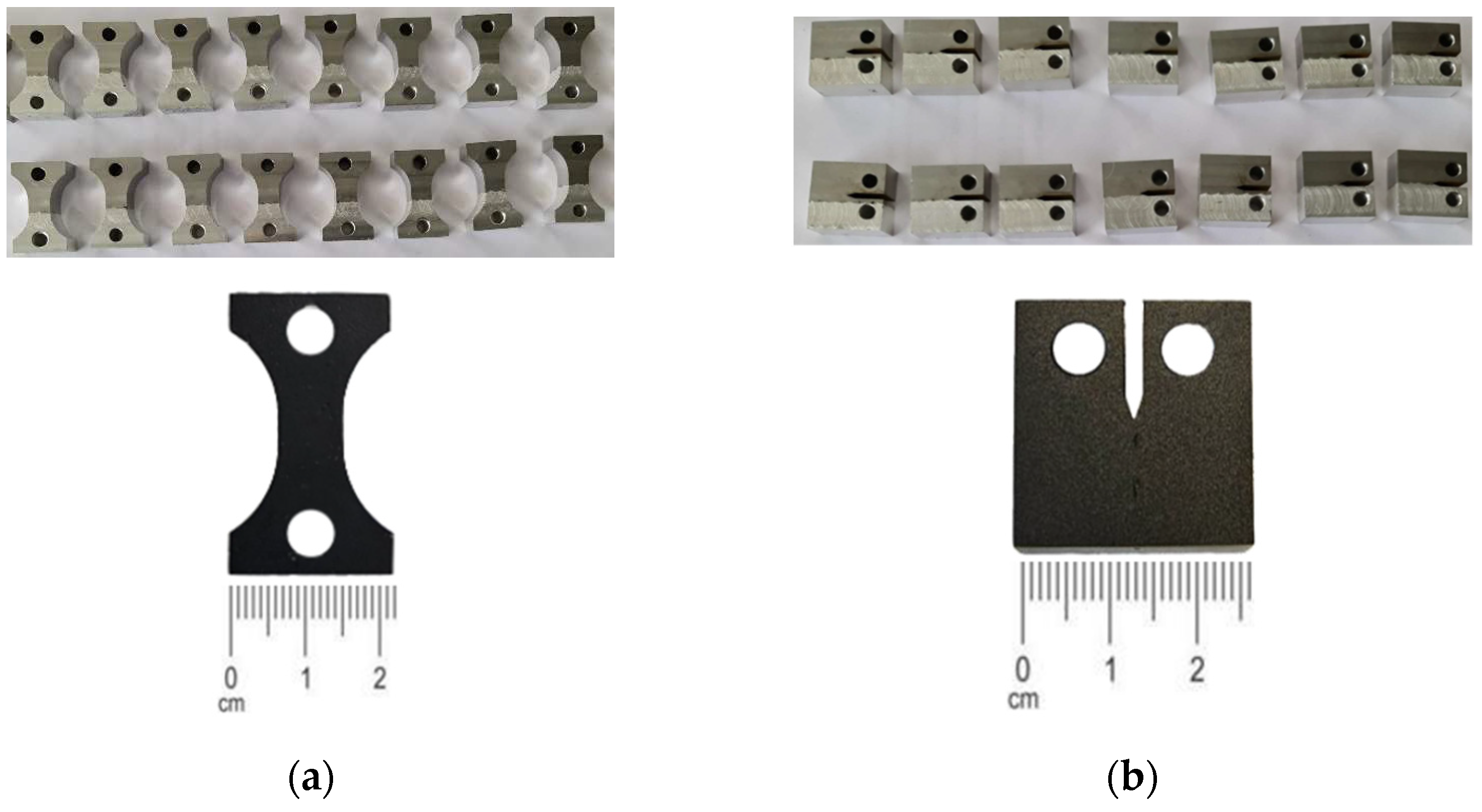

2.1. Design and Manufacturing of EXW Sample

2.2. Experimental Set-Up

3. Results

3.1. Tensile Tests

3.2. Digital Image Correlation

3.3. Infrared Thermography

3.4. Preliminary Thermoelastic Stress Analysis: Feasibility for Multi-Material Region Identification

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eyres, D.J.; Bruce, G.J. Ship Construction; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Frangopol, D.M. Risk-Informed Life-Cycle Optimum Inspection and Maintenance of Ship Structures Considering Corrosion and Fatigue. Ocean. Eng. 2015, 101, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolnikov, V.M. Hybrid Ship Hulls: Engineering Design Rtionales; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, A.N.; Braga, D.F.O.; Moreira, P.M.G.P.; Infante, V. Review on Dissimilar Structures Joints Failure. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 129, 105652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, K.; Qiao, K.; Wu, B.; Liu, Q.; Han, P.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Hao, Z.; Zheng, P. Evolution Mechanism of Intermetallic Compounds and the Mechanical Properties of Dissimilar Friction Stir Welded QP980 Steel and 6061 Aluminum Alloy. Mater. Charact. 2023, 202, 113033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, S.; Ozturk, F.; Demirdogen, M.F. A Comprehensive Literature Review on Friction Stir Welding: Process Parameters, Joint Integrity, and Mechanical Properties. J. Eng. Res. 2025, 13, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, T.; Arbo, S.M.; Hagen, A.B.; Blindheim, J.; Friis, J.; Khalid, M.Z.; Ringdalen, I.G.; Holmestad, R.; Westermann, I.; Vullum, P.E. On Intermetallic Phases Formed during Interdiffusion between Aluminium Alloys and Stainless Steel. Intermetallics 2022, 142, 107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Shi, C.; Xin, Z.; Zeng, Z. Laser-CMT Hybrid Welding-Brazing of Al/Steel Butt Joint: Weld Formation, Intermetallic Compounds, and Mechanical Properties. Materials 2019, 12, 3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miclosina, C.-O.; Belu-Nica, R.; Ciubotariu, C.R.; Marginean, G. Processing and Evaluation of an Aluminum Matrix Composite Material. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kota, P.K.; Myilsamy, G.; Ramalingam, V.V. Metallurgical Characterization and Mechanical Properties of Solid–Liquid Compound Casting of Aluminum Alloy: Steel Bimetallic Materials. Met. Mater. Int. 2022, 28, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

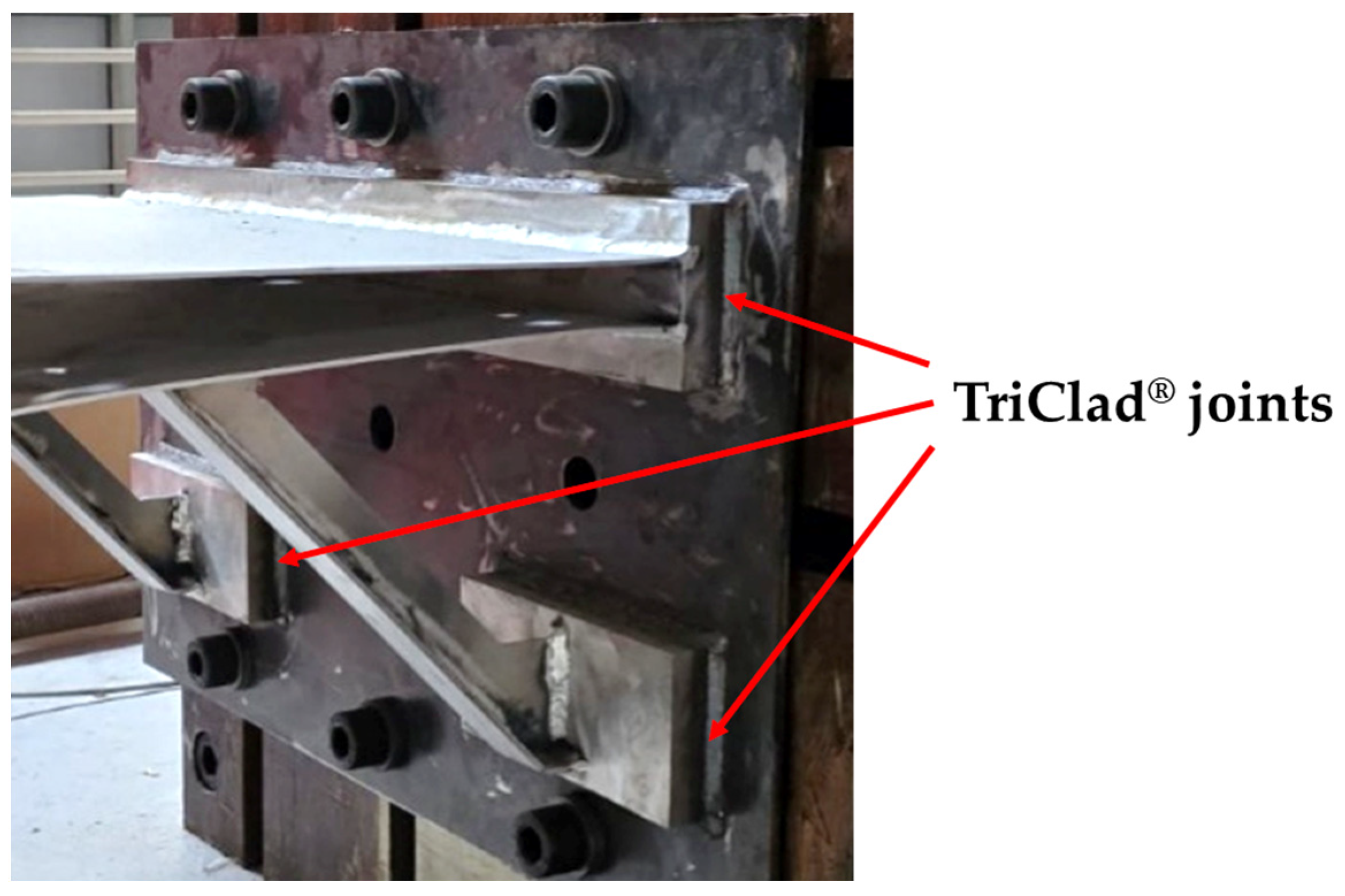

- TriClad® Detacouple Joints Merren & La Porte. Available online: https://triclad.com/welding-parameters-general-guidelines/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Palaci, Y.; Olgun, M. Influences of Heat Treatment on Mechanical Behavior and Microstructure of the Explosively Welded D Grade Steel/EN AW 5083 Aluminium Joint. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2020, 66, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroński, D.; Skibicki, A.; Maćkowiak, P.; Płaczek, D. Modeling and Analysis of Thin-Walled Al/Steel Explosion Welded Transition Joints for Shipbuilding Applications. Mar. Struct. 2020, 74, 102843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Y. Microstructural, Mechanical and Corrosion Investigations of Ship Steel-Aluminum Bimetal Composites Produced by Explosive Welding. Metals 2018, 8, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, V.; Chiofalo, G.; Guglielmino, E. Infrared Investigations for the Analysis of Low Cycle Fatigue Processes in Carbon Steels. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2011, 225, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corigliano, P.; Crupi, V.; Pei, X.; Dong, P. DIC-Based Structural Strain Approach for Low-Cycle Fatigue Assessment of AA 5083 Welded Joints. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2021, 116, 103090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, M.; Kowalski, M. Fatigue Life Estimation of Explosive Cladded Transition Joints with the Use of the Spectral Method for the Case of a Random Sea State. Mar. Struct. 2020, 71, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiäinen, K.; Afkhami, S.; Havia, J.; Ahola, A.; Moshtaghi, M.; Björk, T. Fatigue Performance of Explosion-Cladded Steel-to-Aluminum Transition Joints for Marine Applications. Weld. World 2025, 69, 2323–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

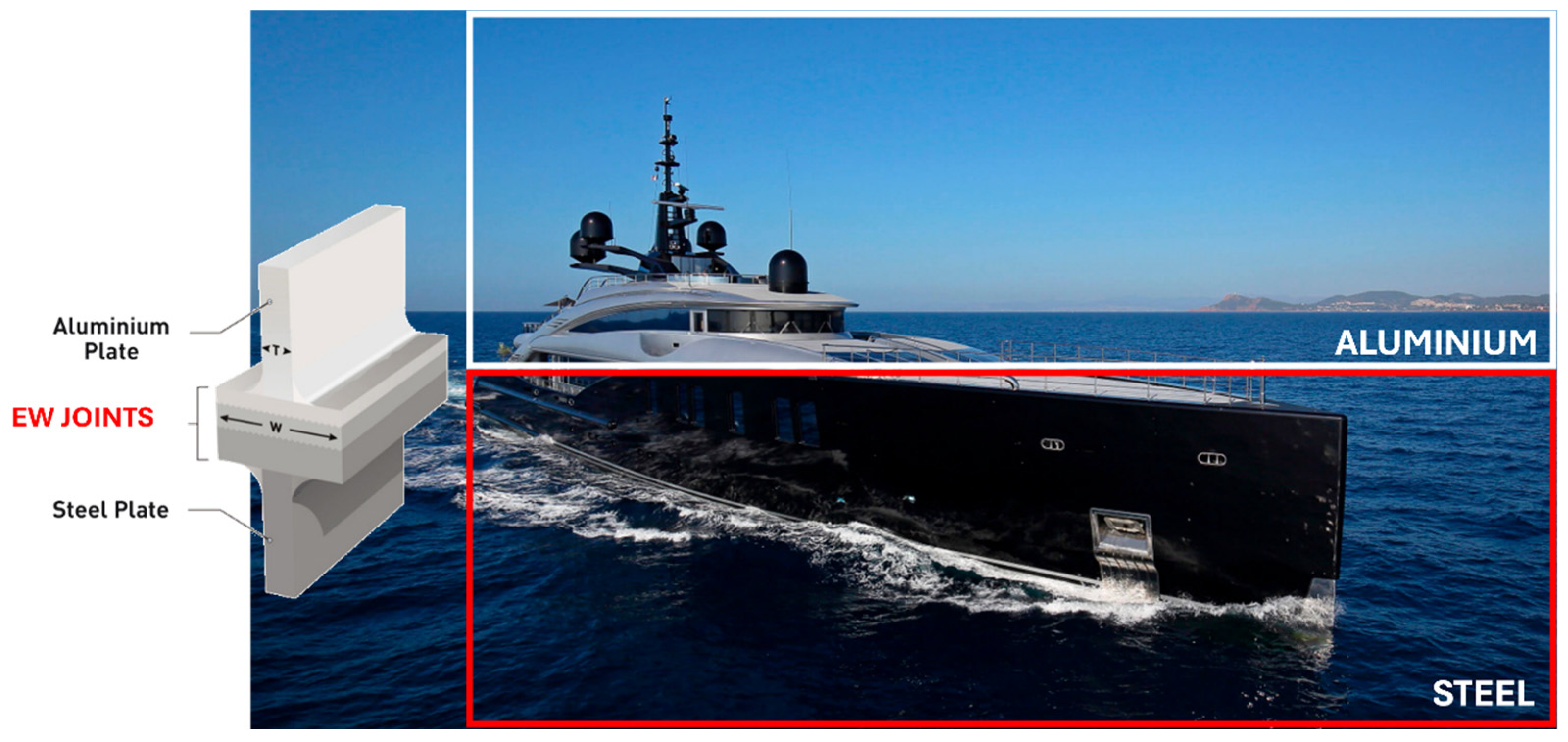

- Available online: https://www.isayachts.com/it/fleet/m-y-okto/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Corigliano, P.; Calabrese, L.; Crupi, V. Salt Spray Fog Ageing of Al/Steel Structural Transition Joints for Shipbuilding. In Sustainable Development and Innovations in Marine Technologies; CRC Press: London, UK, 2022; pp. 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Di Carolo, F.; John, P.K.; De Finis, R.; Palumbo, D.; D’Accardi, E.; Crupi, V.; Briguglio, G.; Galietti, U. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Structural Solutions Using Dissimilar Materials and Hybrid Joints. In Technology and Science for the Ships of the Future; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- International Aluminium Institute. Aluminium Sector Greenhouse Gas Pathways to 2050; International Aluminium Institute: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 7500-1; Metallic Materials—Verification of Static Uniaxial Testing Machines—Part 1: Tension/Compression Testing Machines—Verification and Calibration of the Force-Measuring System. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- MIL-J-24445A; Joint, Bimetallic Bonded, Aluminum to Steel. United States Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 1977.

| Shear Strength [MPa] | Tensile Strength [MPa] | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum value | 60 | 76 |

| Typical value | 94 | 126 |

| Load [kN] | Displacement [mm] | Stiffness [N/mm] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TR specimens | 8.93 ± 1.23 | 2.10 ± 0.98 | 10,905 ± 5219 |

| CT specimens | 4.16 ± 1.69 | 1.41 ± 1.17 | 6927 ± 3577 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brando, G.; Distefano, F.; Di Carolo, F.; Crupi, V.; Epasto, G.; Galietti, U. Dissimilar Welded Joints and Sustainable Materials for Ship Structures. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2296. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122296

Brando G, Distefano F, Di Carolo F, Crupi V, Epasto G, Galietti U. Dissimilar Welded Joints and Sustainable Materials for Ship Structures. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2296. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122296

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrando, Giuseppe, Fabio Distefano, Francesca Di Carolo, Vincenzo Crupi, Gabriella Epasto, and Umberto Galietti. 2025. "Dissimilar Welded Joints and Sustainable Materials for Ship Structures" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2296. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122296

APA StyleBrando, G., Distefano, F., Di Carolo, F., Crupi, V., Epasto, G., & Galietti, U. (2025). Dissimilar Welded Joints and Sustainable Materials for Ship Structures. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2296. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122296