TriEncoderNet: Multi-Stage Fusion of CNN, Transformer, and HOG Features for Forward-Looking Sonar Image Segmentation

Abstract

1. Introduction

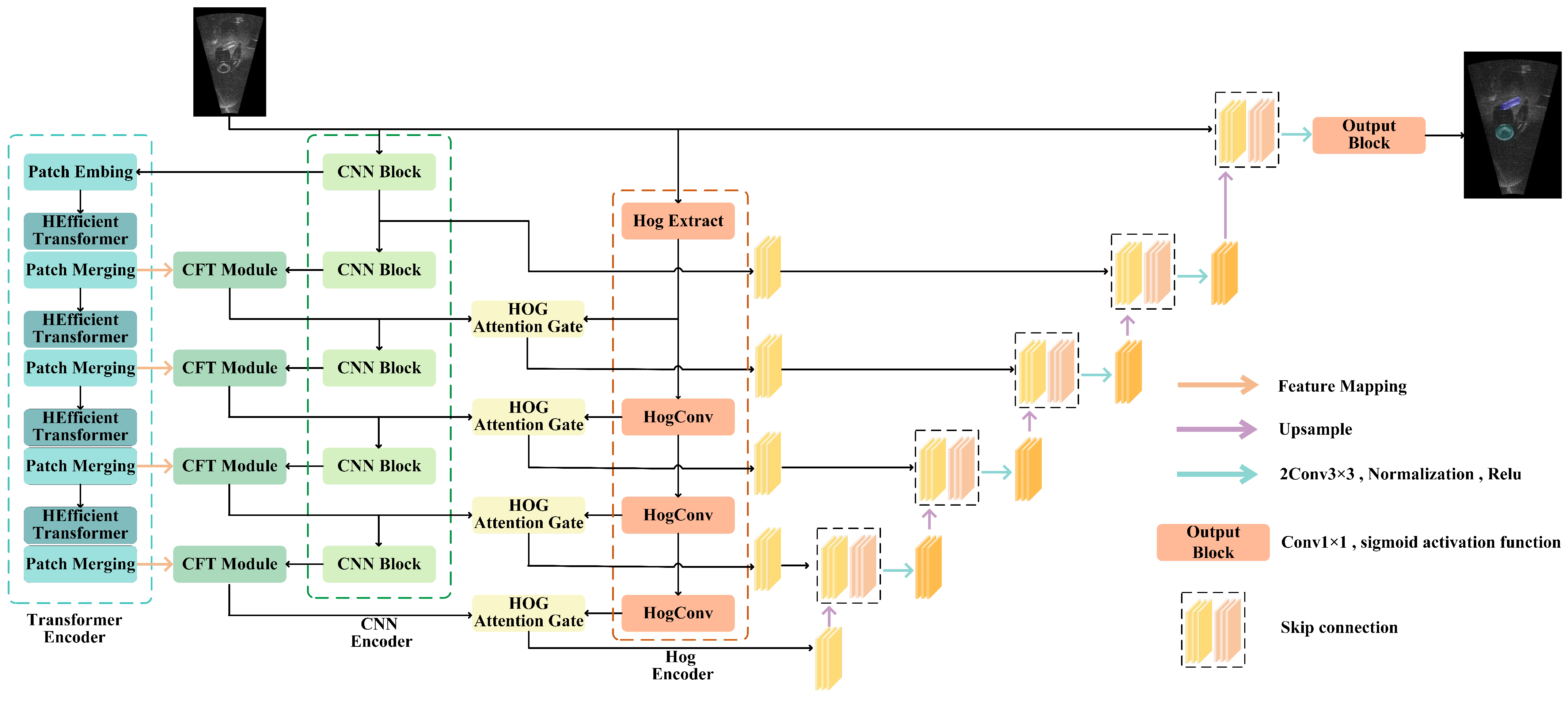

- A novel model TriEncoderNet is proposed in this work, which utilizes three parallel branches to extract different types of features simultaneously. CNNs are used to extract local high-resolution features. Transformers are employed to capture global contextual information. A HOG encoder is used to extract gradient features. The segmentation performance is significantly improved by effectively fusing the advantages of these three features.

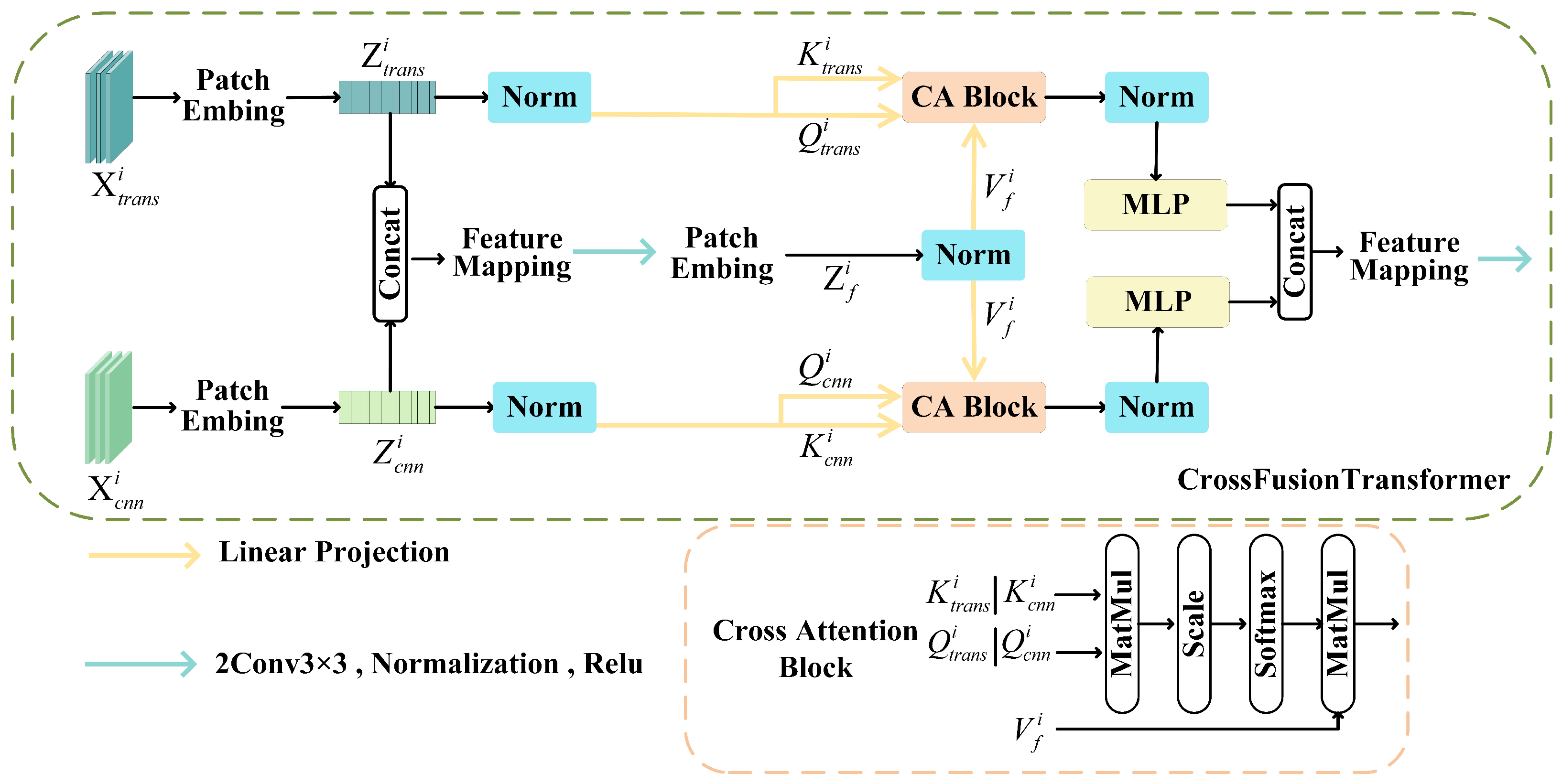

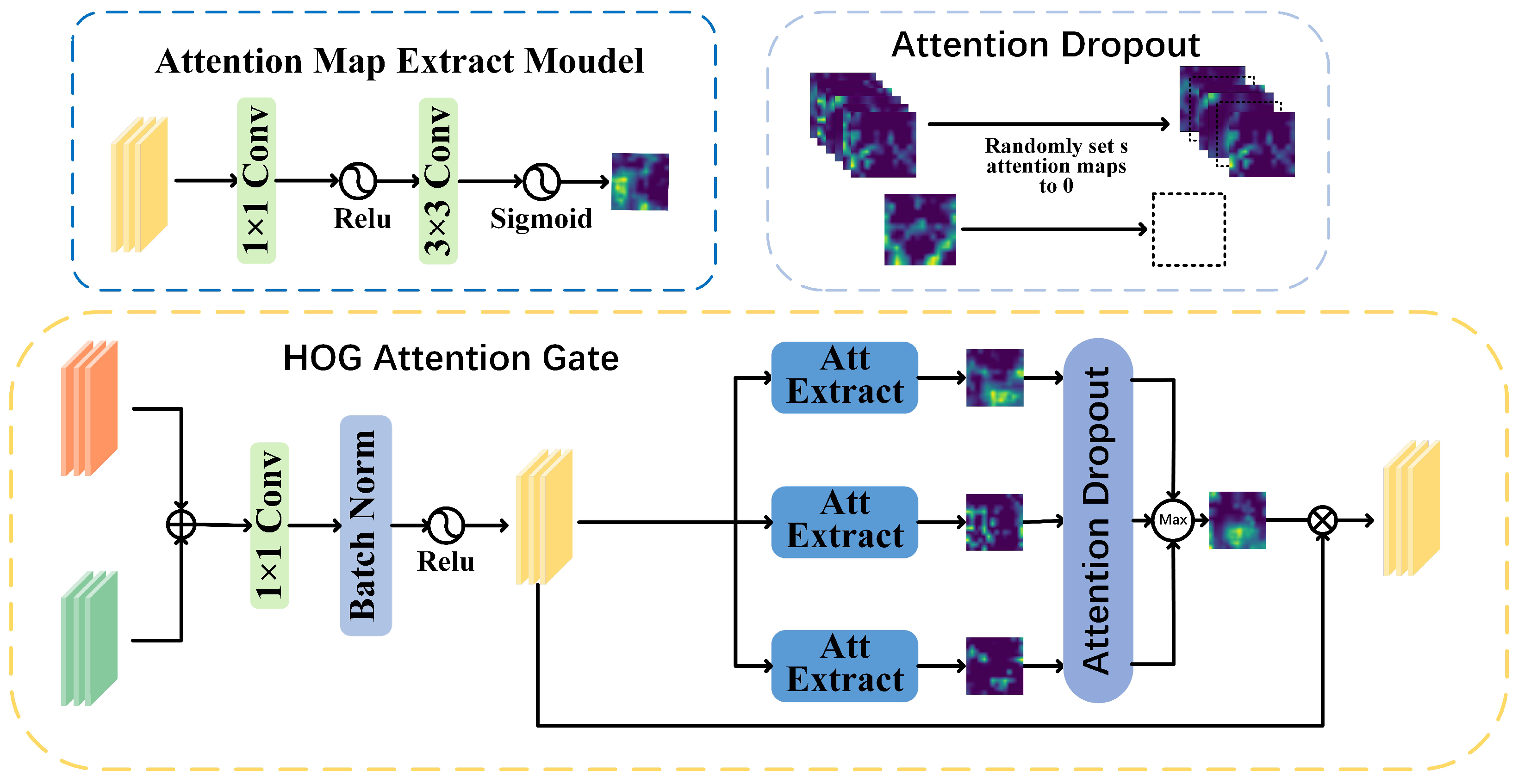

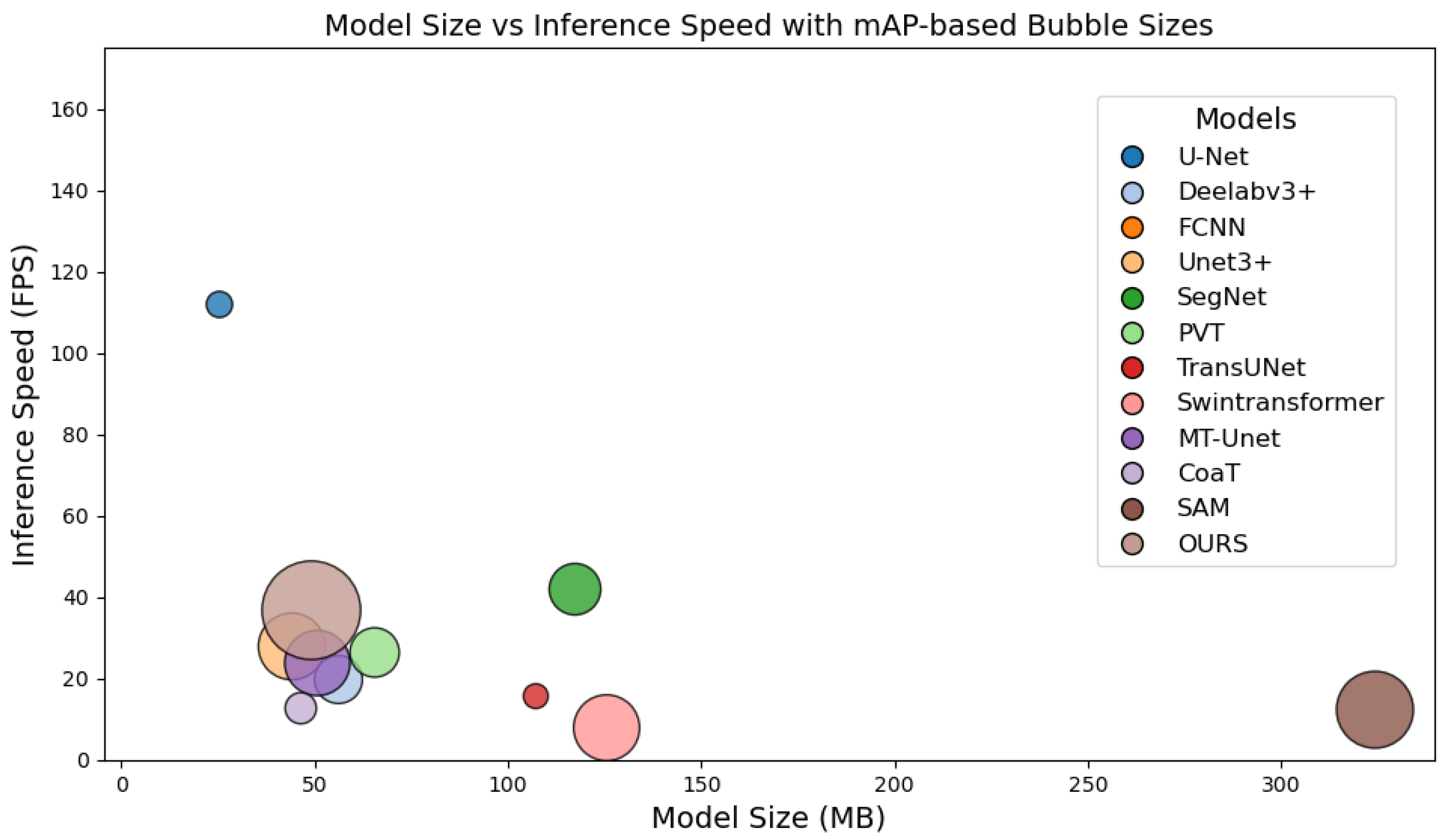

- TriEncoderNet introduces the CFT module and the HAG module. These two modules enable the deep fusion of features with different semantic meanings at multiple scales. The CFT module enhances information representation by effectively integrating the complementarity of local and global features, while the HAG improves the model’s ability to perceive edge information, significantly boosting segmentation accuracy.

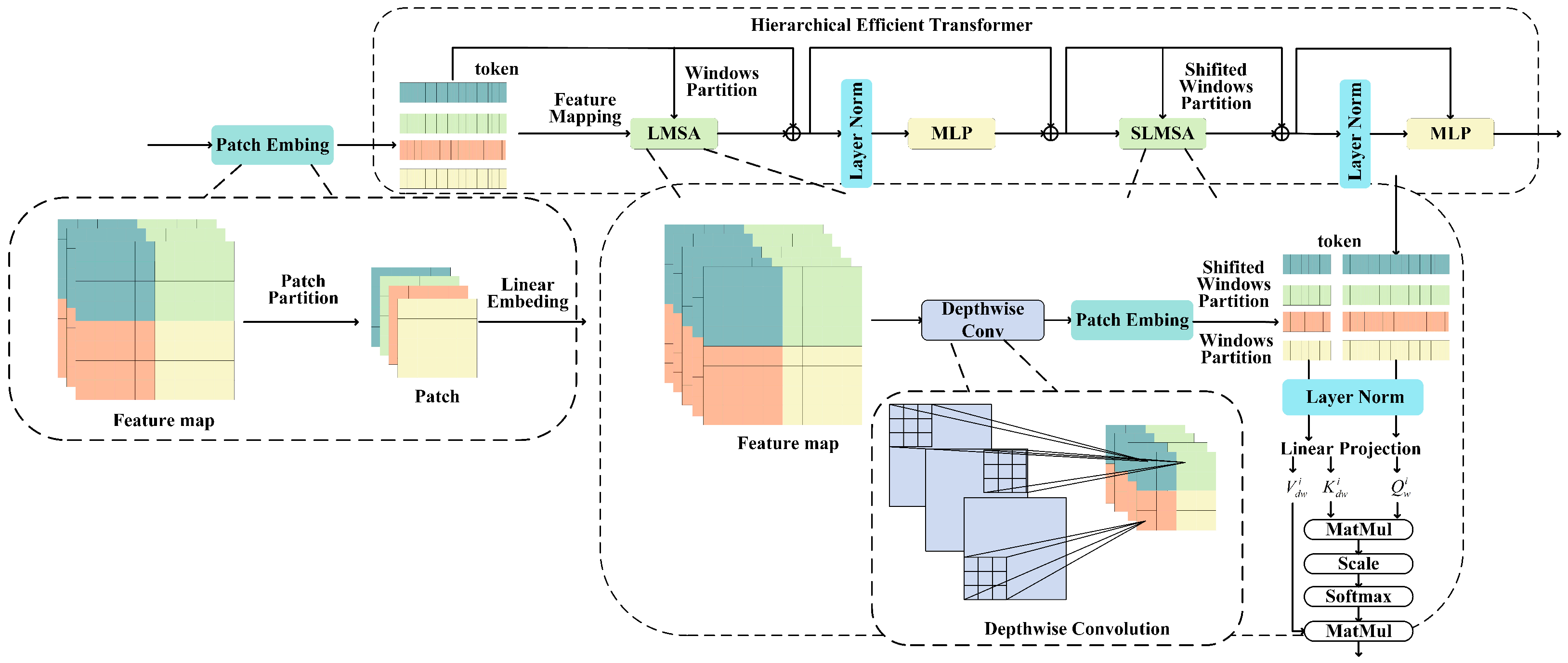

- A HETransformer is desired in TriEncoderNet, incorporating a lightweight multi-head self-attention (LMSA) mechanism. The LMSA mechanism facilitates cross-window interactions within local regions, captures global context, and effectively reduces computational complexity.

- Through comparative experiments on two publicly available datasets, TriEncoderNet outperforms state-of-the-art sonar segmentation algorithms, achieving the best results in terms of performance.

2. Related Work

2.1. CNN-Based Sonar Image Segmentation Methods

2.2. Transformer-Based Image Segmentation Methods

2.3. Hybrid Transformer–CNN Models

3. Method

3.1. Overall Architecture

3.2. Hierarchical Efficient Transformer (HETransformer)

3.3. CrossFusionTransformer (CFT)

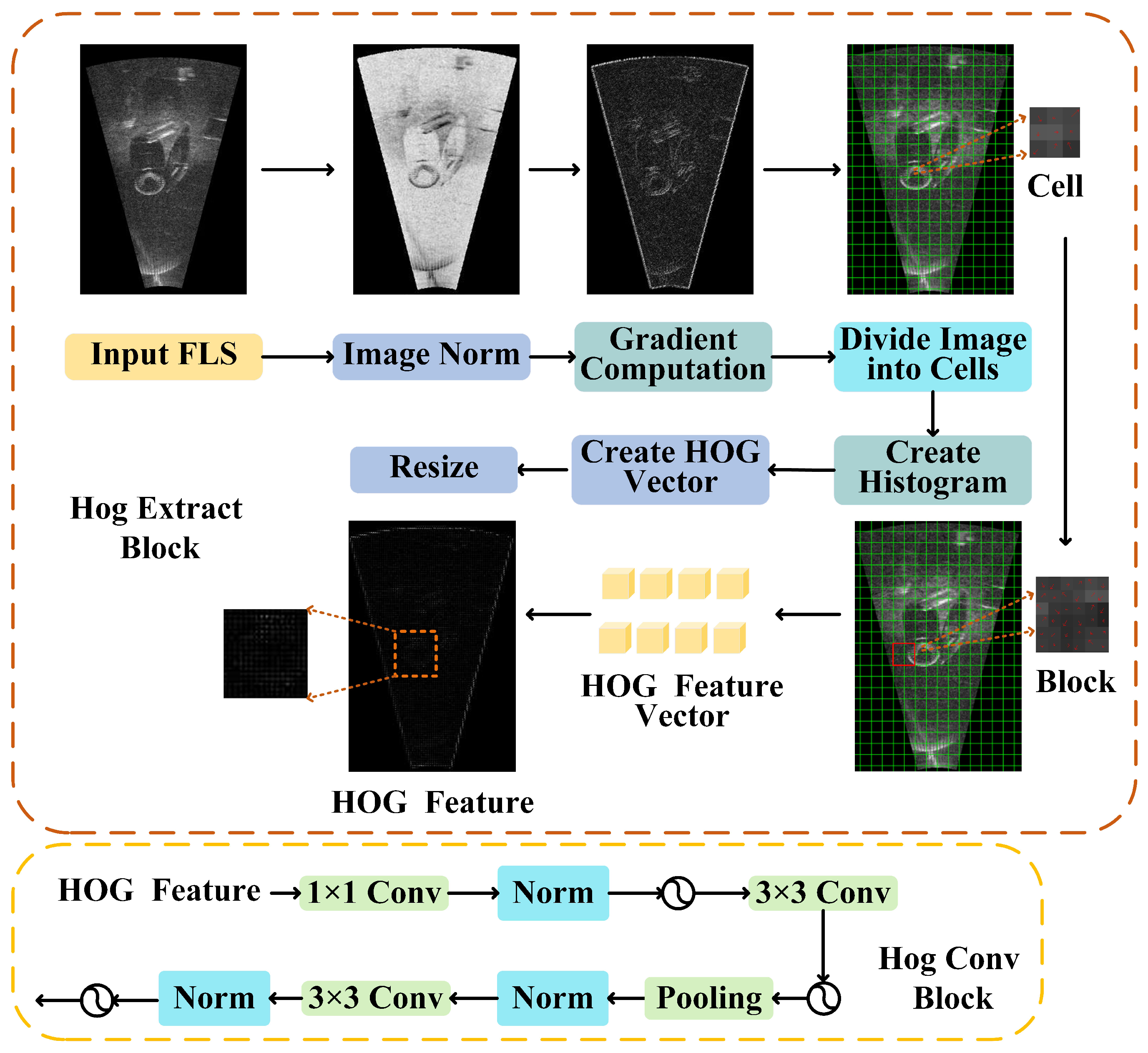

3.4. Hog Extract Block, HogConv Block and HOG Attention Gate

4. Experiment

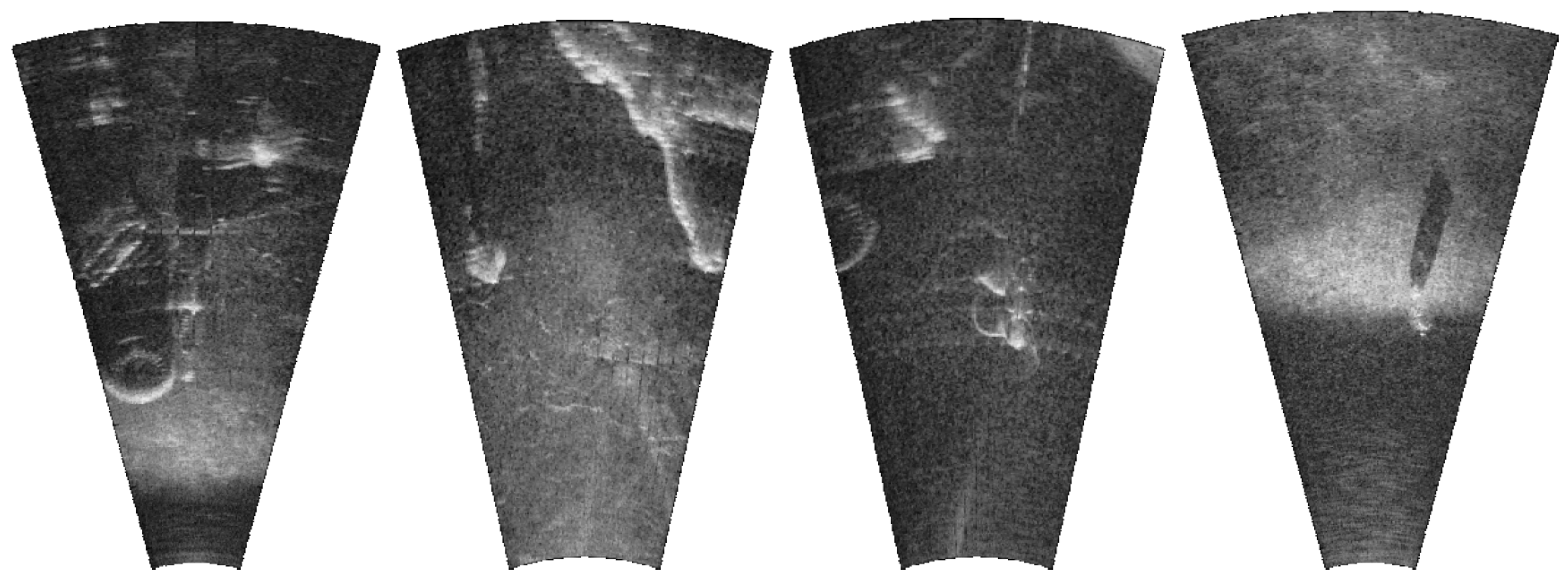

4.1. FLS Image Dataset

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Implementation Details

4.4. Comparison with the SOTA Methods

4.5. Computational Efficiency Analysis

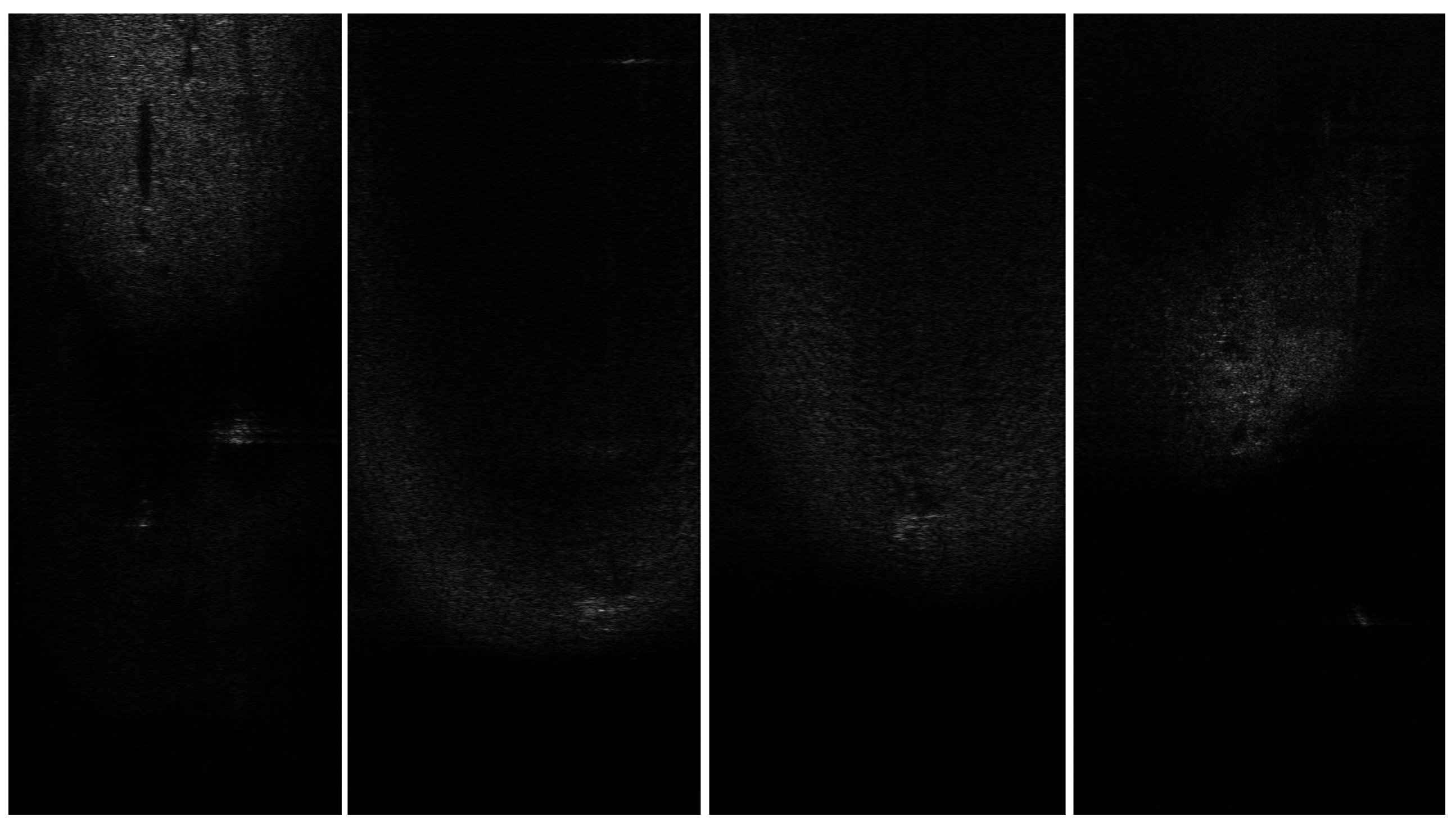

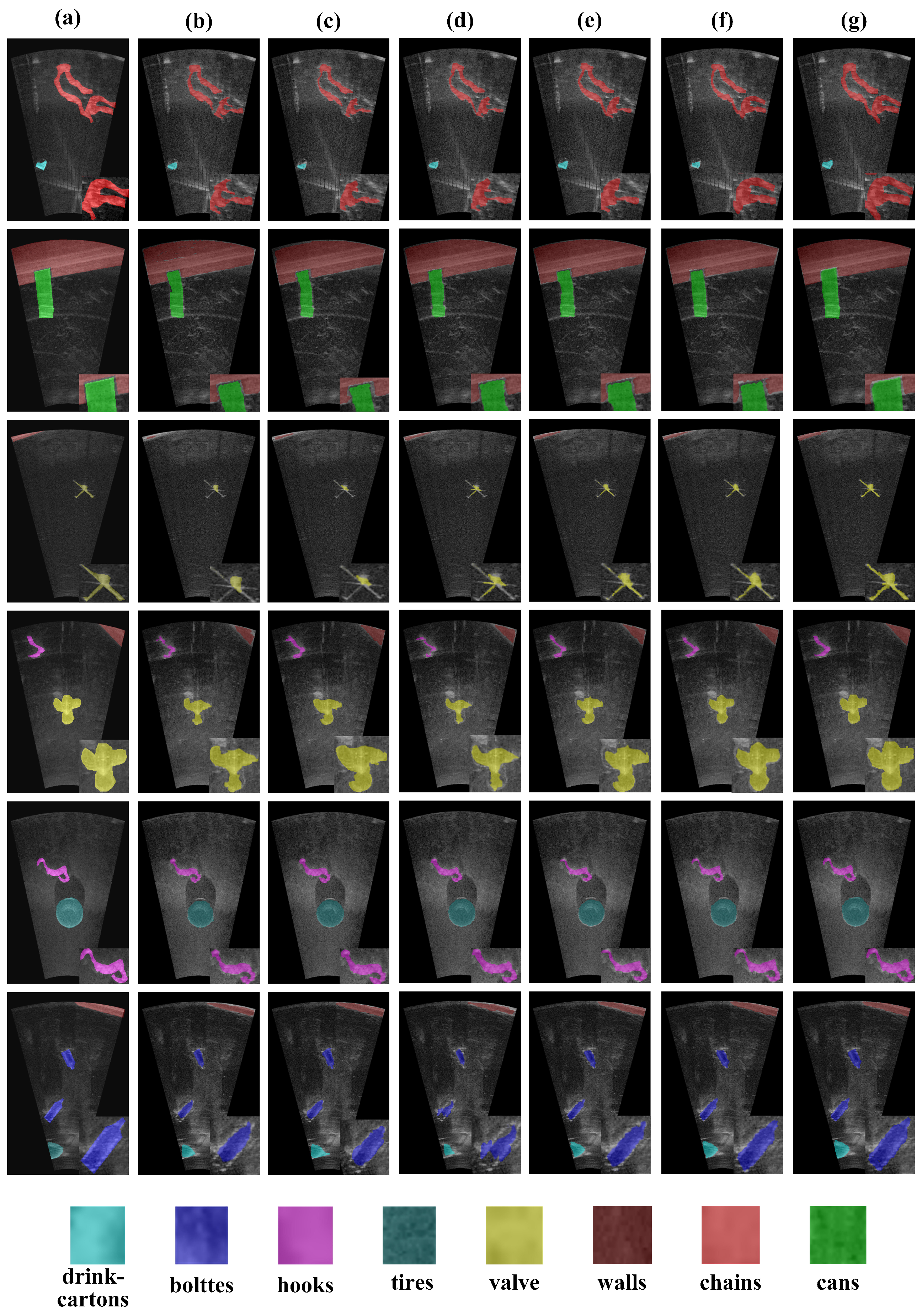

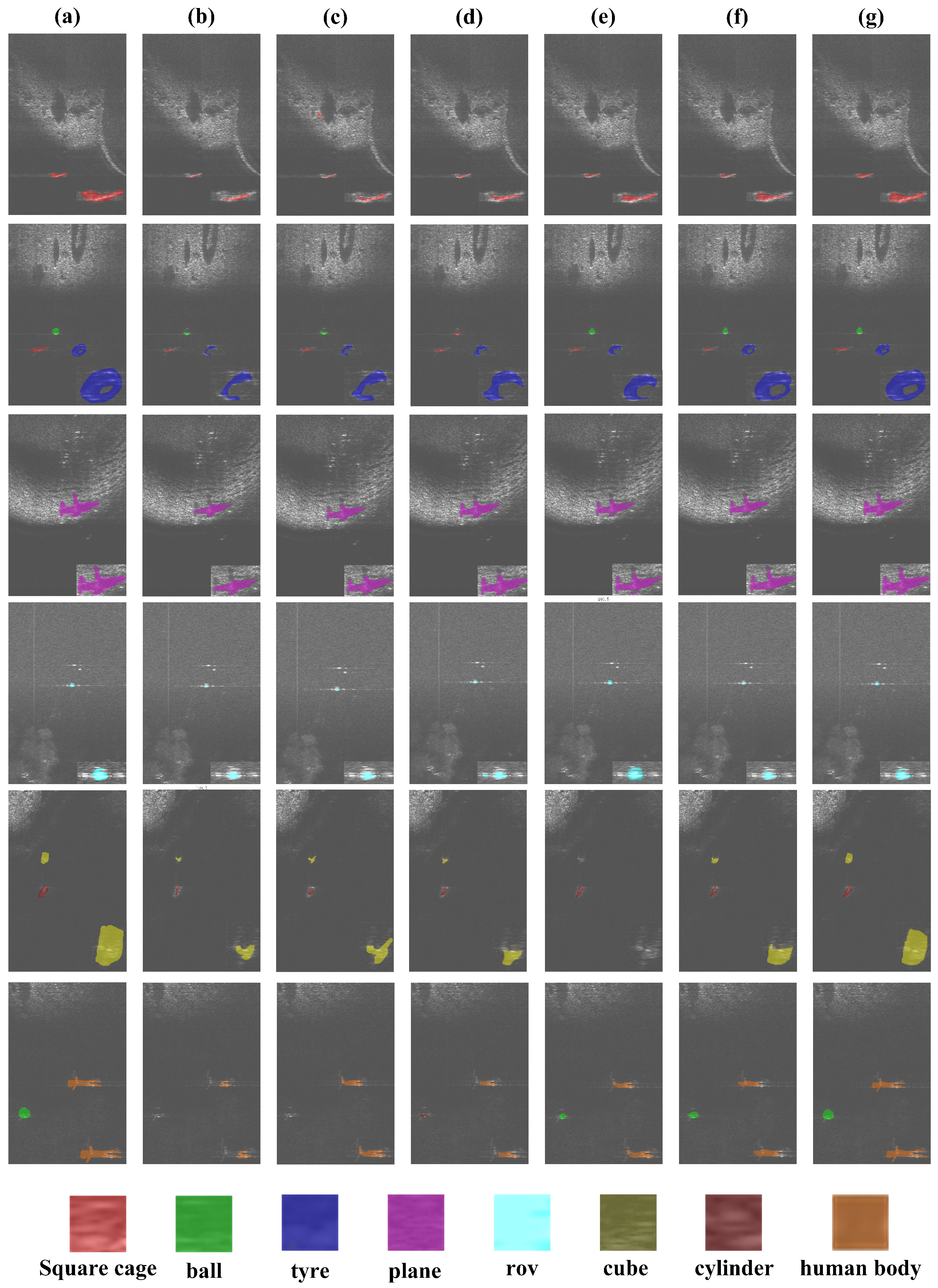

4.6. Visualization Analysis

5. Ablation Study

5.1. Ablation Study of Hand-Crafted Feature Fusions

Ablation Study of Proposed Blocks

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FLS | Forward-Looking Sonar |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CFT | CrossFusionTransformer |

| MRF | Markov random field |

| HETransformer | Hierarchical Efficient Transformer |

| HOG | Histogram of Oriented Gradients |

| CT | CNN–Transformer |

| CTH | CNN–Transformer–Hog |

| LMSA | lightweight multi-head self-attention |

References

- Long, H.; Shen, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J. Underwater forward-looking sonar images target detection via speckle reduction and scene prior. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5604413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Hu, T.; Zhu, J. Underwater sonar target detection based on improved ScEMA YOLOv8. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1503505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Xu, H.; Li, S.; Yu, Y. Efficient SonarNet: Lightweight CNN grafted Vision Transformer embedding network for forward-looking sonar image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4210317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Ge, W.; Chen, P.; Hu, Y.; Dang, Y.; Liang, R.; Guo, X. Feature Pyramid U-Net with attention for semantic segmentation of forward-looking sonar images. Sensors 2022, 22, 8468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Sun, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Han, Y.; Cui, S.; Li, Z. MLMFFNet: Multilevel Mixed Feature Fusion Network for Real-Time Forward-Looking Sonar Image Segmentation. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 50, 1356–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Z. Three-Stage Distortion-Driven Enhancement Network for Forward-Looking Sonar Image Segmentation. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 3867–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, B.; Yu, X. Underwater multitarget tracking method based on threshold segmentation. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 48, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lan, L.; Sun, L. A review of sonar image segmentation for underwater small targets. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Intelligent Systems, Athens, Greece, 30 July–2 August 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Jiang, P.; Zhu, H. A local region-based level set method with Markov random field for side-scan sonar image multi-level segmentation. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 21, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cai, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J. A level set method with heterogeneity filter for side-scan sonar image segmentation. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Tian, W.; Chen, Z.; Yang, D. Underwater sonar image segmentation by a novel joint level set model. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2173, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, G.; Lu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H. Hybrid Modeling Based Semantic Segmentation of Forward-Looking Sonar Images. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 50, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 18, pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. SegNet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, J. Maanu-Net: Multi-level attention and atrous pyramid nested U-Net for wrecked objects segmentation in forward-looking sonar images. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Bordeaux, France, 16–19 October 2022; pp. 736–740. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Zhou, H.; Chen, P.; Hu, Y.; Ge, W.; Dang, Y.; Liang, R. Design of forward-looking sonar system for real-time image segmentation with light multiscale attention net. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 4501217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual Event, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-F.; Panda, R.; Fan, Q. RegionViT: Regional-to-local attention for vision transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.02689. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.-P.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual Event, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 568–578. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Yu, Y.; Xu, H. Reverberation Suppression and Multilayer Context Aware for Underwater Forward-Looking Sonar Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 5014517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, C.; Yu, W.; Zhou, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Yan, S. Inception transformer. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 23495–23509. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. TransUNet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, J.; Xu, H.; Yu, Y. SonarNet: Hybrid CNN-Transformer-HOG framework and multifeature fusion mechanism for forward-looking sonar image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4203217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carisi, L.; Chiereghin, F.; Fantozzi, C.; Nanni, L. SAM-Based Input Augmentations and Ensemble Strategies for Image Segmentation. Information 2025, 16, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiyanesh, B.; Vijayalakshmi, M.; Saranya, P.; Viji, D. EnsembleEdgeFusion: Advancing semantic segmentation in microvascular decompression imaging with innovative ensemble techniques. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Das Choudhury, S.; Das, A.K.; Samal, A.; Awada, T. EmergeNet: A novel deep-learning based ensemble segmentation model for emergence timing detection of coleoptile. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1084778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.; Nguyen, T.T.; McCall, J.; Elyan, E.; Moreno-García, C.F. Two-layer Ensemble of Deep Learning Models for Medical Image Segmentation. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 1141–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Xia, W.; Liu, X.; Li, H. Detection and segmentation of underwater objects from forward-looking sonar based on a modified Mask RCNN. Signal Image Video Process. 2021, 15, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Cheng, C.; Wang, C.; Pan, G.; Zhang, F. Side-scan sonar image segmentation based on multi-channel CNN for AUV navigation. Front. Neurorobot. 2022, 16, 928206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Y. Seg2Sonar: A full-class sample synthesis method applied to underwater sonar image target detection, recognition, and segmentation tasks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5909319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Gross, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, B. Fused adaptive receptive field mechanism and dynamic multiscale dilated convolution for side-scan sonar image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5116817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zuo, Z.; Sun, B.; Wu, P.; Zhang, J. DSA-SOLO: Double split attention SOLO for side-scan sonar target segmentation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xu, Y.; Chang, T.; Tu, Z. Co-scale conv-attentional image transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual Event, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 9981–9990. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Dai, X.; Xiao, B.; Yuan, L.; Gao, J. Focal self-attention for local-global interactions in vision transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.00641. [Google Scholar]

- Rajani, H.; Gracias, N.; Garcia, R. A convolutional vision transformer for semantic segmentation of side-scan sonar data. Ocean Eng. 2023, 286, 115647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Wang, K.; Li, T.; Du, C.; Xia, S.; Fu, H. H2Former: An efficient hierarchical hybrid transformer for medical image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med Imaging 2023, 42, 2763–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamizadeh, A.; Tang, Y.; Nath, V.; Yang, D.; Myronenko, A.; Landman, B.; Roth, H.R.; Xu, D. UNETR: Transformers for 3D medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 574–584. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, D.; Yao, R.; Xue, Y. Swin Transformer Embedding UNet for Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4408715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, Z.; Luo, G.; Chen, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Yu, G.; Shen, C. TopFormer: Token pyramid transformer for mobile semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 12083–12093. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, C.; Fang, S.; Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Atkinson, P.M. UNetFormer: A UNet-like transformer for efficient semantic segmentation of remote sensing urban scene imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Ke, X.; Liu, C.; Xu, X.; Zhan, X.; Wang, C.; Ahmad, I.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, D. HOG-ShipCLSNet: A novel deep learning network with HOG feature fusion for SAR ship classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5210322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Hou, J.; Huang, L.; Shi, H.; Hu, J. Partial occlusion face recognition based on CNN and HOG feature fusion. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 4th International Conference on Electronics and Communication Engineering (ICECE), Xi’an, China, 17–19 December 2021; pp. 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.; Valdenegro-Toro, M. The marine debris dataset for forward-looking sonar semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual Event, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 3741–3749. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, K.; Yang, J.; Qiu, K. A dataset with multibeam forward-looking sonar for underwater object detection. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.-Y. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Lin, L.; Tong, R.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Iwamoto, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, Y.-W.; Wu, J. UNet 3+: A full-scale connected UNet for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Virtual Event, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 1055–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Xie, S.; Lin, L.; Iwamoto, Y.; Han, X.-H.; Chen, Y.-W.; Tong, R. Mixed transformer U-Net for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022—2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 2390–2394. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, D.; Song, K. Remote sensing image classification based on Canny operator enhanced edge features. Sensors 2024, 24, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koike, H.; Ashizawa, K.; Tsutsui, S.; Kurohama, H.; Okano, S.; Nagayasu, T.; Kido, S.; Uetani, M.; Toya, R. Differentiation between heterogeneous GGN and part-solid nodule using 2D grayscale histogram analysis of thin-section CT image. Clin. Lung Cancer 2023, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayyat, M.M.; Zamzami, N.; Zhang, L.; Nappi, M.; Umer, M. Fuzzy-CNN: Improving personal human identification based on IRIS recognition using LBP features. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2024, 83, 103761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional methods | Thresholding-based methods [7] | Minimal training requirement, Low computational complexity. | Limited robustness and generalizability. |

| Clustering-based methods [8] | |||

| Markov random field (MRF)-based methods [9] | |||

| Level set-based methods [10,11] | |||

| Deep learning methods | Typical CNN-based algorithms include U-Net [13], DeepLabv3+ [14], FCNN [15], SegNet [16], MAANU-Net [17] and LMA-Net [18]. | Dealing with local features and multi-scale information well. | Considering global feature extraction insufficiently. |

| Transformer-based methods including Swin Transformer [20], RegionViT [21] | Capturing global contextual relationships remarkably | Insufficient performance in representing local features. | |

| Hybrid approaches: iFormer [24], TransUNet [25], SonarNet [26] | Balanced performance between modeling local details and global context. | Limited comprehensive utilization of the interdependencies between local and global features. |

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| Height, width, and channel number of the input image | |

| P | Patch size used in Patch Embedding |

| d | Dimension of the feature vectors (tokens) |

| n | Number of tokens |

| M | Window size in Window Partition |

| k | Downsampling factor in LMSA |

| Feature vectors from the Transformer encoder | |

| Feature vectors from the CNN encoder | |

| Feature vectors from the HOG encoder | |

| Attention maps generated in HAG |

| Category | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Training Settings | Optimizer | Adam |

| Initial Learning Rate | ||

| Batch Size | 8 | |

| Epochs | 160 | |

| Weight Decay | ||

| Learning Rate Scheduler | Cosine Annealing | |

| Model Architecture | Input Size | |

| Patch Size (P) | 4 | |

| Window Size (M) | 7 | |

| Data Augmentation | Random Flip | Probability 0.5 |

| Random Rotation | [−10°, 10°] | |

| Random Scaling | [0.5, 2.0] | |

| Color Jittering | Brightness, Contrast |

| Model | IoU ↑ | Evaluation Index ↑ | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | Bottle | Can | Chain | Drink Carton | Hook | Propeller | Shampoo Bottle | Standing Bottle | Tire | Valve | Wall | M_IoU | MPA | |

| U-Net | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.54 | 0.73 | 0.49 | 0.86 | 0.59 | 0.80 | 0.699 | 0.816 |

| Deeplabv3+ | 0.99 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 0.53 | 0.89 | 0.57 | 0.87 | 0.739 | 0.846 |

| FCNN | 0.98 | 0.76 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.41 | 0.86 | 0.50 | 0.83 | 0.685 | 0.801 |

| Unet3+ | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.83 | 0.46 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 0.85 | 0.750 | 0.872 |

| SegNet | 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.49 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.89 | 0.741 | 0.851 |

| PVT | 0.99 | 0.83 | 0.56 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.46 | 0.87 | 0.60 | 0.82 | 0.718 | 0.848 |

| TransUNet | 0.99 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.31 | 0.90 | 0.42 | 0.86 | 0.696 | 0.814 |

| Swintransformer | 0.99 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.87 | 0.63 | 0.88 | 0.749 | 0.871 |

| MT-Unet | 0.99 | 0.84 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.44 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.88 | 0.746 | 0.870 |

| COAT | 0.99 | 0.80 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 0.88 | 0.61 | 0.82 | 0.708 | 0.823 |

| SAM | 0.99 | 0.78 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.46 | 0.90 | 0.64 | 0.88 | 0.749 | 0.886 |

| Our | 0.99 | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.54 | 0.91 | 0.66 | 0.90 | 0.793 | 0.916 |

| Model | IoU ↑ | Evaluation Index ↑ | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | Cube | Ball | Cylinder | Human Body | Tire | Cage | Metal Bucket | Plane | Rov | M_IoU | MPA | |

| U-Net | 0.99 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.461 | 0.523 |

| Deeplabv3+ | 0.99 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.442 | 0.491 |

| FCNN | 0.99 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.371 | 0.421 |

| Unet3+ | 0.99 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.469 | 0.558 |

| SegNet | 0.99 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.470 | 0.550 |

| PVT | 0.99 | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.467 | 0.516 |

| TransUNet | 0.99 | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.26 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.495 | 0.588 |

| Swintransformer | 0.99 | 0.40 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.550 | 0.632 |

| MT-Unet | 0.99 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.450 | 0.515 |

| COAT | 0.99 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.26 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.463 | 0.521 |

| SAM | 0.99 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.46 | 0.554 | 0.641 |

| Our | 0.99 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.582 | 0.687 |

| Model | Noise Type | Intensity () | Metrics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mIoU | Performance Drop | |||

| U-Net | None | 0 | 0.699 | - |

| Gaussian | 0.01 | 0.642 | −8.2% | |

| Gaussian | 0.05 | 0.515 | −26.3% | |

| Speckle | 0.05 | 0.588 | −15.9% | |

| Speckle | 0.10 | 0.473 | −32.3% | |

| Swin Transformer | None | 0 | 0.749 | - |

| Gaussian | 0.01 | 0.695 | −7.2% | |

| Gaussian | 0.05 | 0.580 | −22.6% | |

| Speckle | 0.05 | 0.645 | −13.9% | |

| Speckle | 0.10 | 0.535 | −28.6% | |

| TriEncoderNet (Ours) | None | 0 | 0.793 | - |

| Gaussian | 0.01 | 0.771 | −2.8% | |

| Gaussian | 0.05 | 0.705 | −11.1% | |

| Speckle | 0.05 | 0.748 | −5.7% | |

| Speckle | 0.10 | 0.682 | −14.0% | |

| Method | GFLOPs (G) |

|---|---|

| U-Net | 126.4 |

| DeepLabv3+ | 30 |

| FCNN | 152.3 |

| UNet3+ | 195.4 |

| SegNet | 160.2 |

| PVT | 46.5 |

| TransUNet | 128 |

| SwinTransformer | 80.5 |

| MT-UNet | 75.1 |

| CoaT | 94.8 |

| SAM | 325.7 |

| TriEncoderNet (Ours) | 54 |

| Hand-Crafted Feature | Marine Debris Dataset | UATD Datasets | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mIoU | mAP | mIoU | mAP | |

| None | 0.780 | 0.902 | 0.570 | 0.671 |

| Canny | 0.785 | 0.908 | 0.575 | 0.677 |

| Grayscale histogram | 0.776 | 0.890 | 0.557 | 0.657 |

| LBP | 0.778 | 0.895 | 0.564 | 0.668 |

| Sobel | 0.782 | 0.909 | 0.572 | 0.673 |

| Unnormalized HOG | 0.785 | 0.906 | 0.562 | 0.667 |

| Learned Gradients | 0.786 | 0.901 | 0.576 | 0.670 |

| HOG (Ours) | 0.793 | 0.916 | 0.582 | 0.687 |

| Model | Ours Modules | Marine Debris Dataset | UATD Dataset | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HET | CFT | HAG | HOG | mIoU | mAP | mIoU | mAP | |

| CNN-baseline | 0.699 | 0.816 | 0.461 | 0.523 | ||||

| Transformer-baseline | 0.752 | 0.880 | 0.523 | 0.636 | ||||

| CT | 0.764 | 0.886 | 0.555 | 0.650 | ||||

| CT + HET | ✓ | 0.769 | 0.889 | 0.561 | 0.661 | |||

| CT + CFT | ✓ | 0.773 | 0.895 | 0.563 | 0.663 | |||

| CT + CFT + HET | ✓ | ✓ | 0.780 | 0.902 | 0.570 | 0.671 | ||

| CTH | ✓ | 0.775 | 0.891 | 0.559 | 0.657 | |||

| CTH + HAG | ✓ | ✓ | 0.783 | 0.896 | 0.566 | 0.669 | ||

| CTH + CFT + HET | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.787 | 0.910 | 0.575 | 0.676 | |

| CTH + CFT + HET + SE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.785 | 0.908 | 0.576 | 0.673 | |

| CTH + CFT + HET + CBAM | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.788 | 0.904 | 0.576 | 0.669 | |

| CTH + CFT + HET + HAG (Ours) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.793 | 0.916 | 0.582 | 0.687 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Dong, Y.; Chen, G.; Chen, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhang, F. TriEncoderNet: Multi-Stage Fusion of CNN, Transformer, and HOG Features for Forward-Looking Sonar Image Segmentation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122295

Liu J, Dong Y, Chen G, Chen Y, Gao J, Zhang F. TriEncoderNet: Multi-Stage Fusion of CNN, Transformer, and HOG Features for Forward-Looking Sonar Image Segmentation. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122295

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jie, Yan Dong, Guofang Chen, Yimin Chen, Jian Gao, and Fubin Zhang. 2025. "TriEncoderNet: Multi-Stage Fusion of CNN, Transformer, and HOG Features for Forward-Looking Sonar Image Segmentation" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122295

APA StyleLiu, J., Dong, Y., Chen, G., Chen, Y., Gao, J., & Zhang, F. (2025). TriEncoderNet: Multi-Stage Fusion of CNN, Transformer, and HOG Features for Forward-Looking Sonar Image Segmentation. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122295