Abstract

Leading-edge erosion (LEE) of wind-turbine blades, driven primarily by rain erosion, particulate erosion, and environmental ageing, remains one of the most pervasive causes of performance loss and maintenance cost in offshore and onshore wind farms. Self-healing coatings, which autonomously or semi-autonomously restore barriers and mechanical function after damage, promise a paradigm shift in blade protection by combining immediate impact resistance with in-service reparability. This review surveys the state of the art in self-healing coating technologies (intrinsic chemistries such as non-covalent interactions or dynamic covalent bonds; extrinsic systems including micro/nanocapsules and microvascular networks) and evaluates their suitability for anti-erosion, mechanical robustness, and multifunctional protection of leading edges. The outcomes of theoretical, experimental, modelling and field-oriented studies on the leading-edge protection and coating characterisation identify which self-healing concepts best meet the simultaneous requirements of toughness, adhesion, surface finish, and long-term durability of wind blade applications. Key gaps are highlighted, notably trade-offs between healing efficiency and mechanical toughness, challenges in large-area and sprayable application methods, and the need for standardised characterisation and testing of self-healing coating protocols. We propose a roadmap for targeted materials research, accelerated testing, and field trials. This review discusses recent studies to guide materials scientists and renewable-energy engineers toward promising routes to deployable, multifunctional, self-healing anti-erosion coatings, especially for wind-energy infrastructure.

1. Introduction

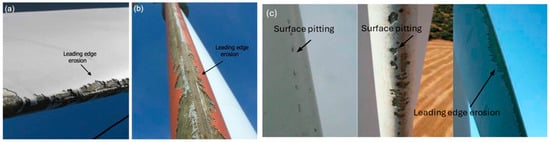

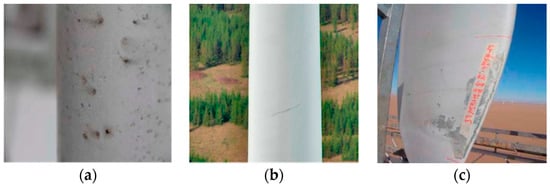

Wind energy is an integral pillar of the global transition to low-carbon energy, but the operational reliability and lifetime performance of wind turbines remain constrained by coating-level degradation mechanisms, LEE, and surface pitting of rotor blades, as well as the high costs associated with these issues (Figure 1). Minor failures, mainly surface erosion, occur twelve times more frequently than structural failures and are the leading cause of unplanned repairs [1]. LEE arises when working under harsh environmental conditions, such as water droplets, sand, dust, hail, and ice impinging on the blade leading edge at relative velocities that cause progressive material removal, surface roughening, and eventually structural exposure of the blade shell and underlying composite laminate. The aerodynamic consequences of LEE include increased surface roughness, reduced lift and increased drag, and measurable annual energy production (AEP) losses; in some sites, LEE requires routine repairs and localised replacements within a few years of service [2,3,4,5].

Figure 1.

Examples of LEE (a,b) [6] and surface pitting (c) [7] may evolve into crack propagation within the leading-edge protection (LEP) layer or the underlying composite, thereby reducing the structural integrity and aerodynamic efficiency of the wind turbine blades.

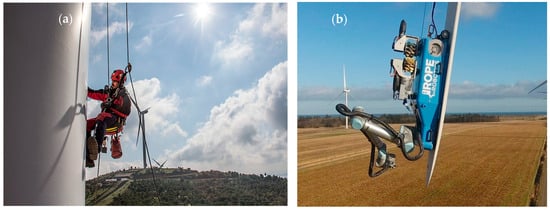

Conventional mitigation strategies rely on sacrificial polyurethane overlays, hard elastomeric coatings, or protective tapes and leading-edge shields [8,9]. These approaches provide short-term protection but have limits: sacrificial layers must be replaced frequently, hard coatings can suffer rapid crack initiation under cyclic impact, and many coatings trade off surface finish or adhesion for hardness, which reduces aerodynamic performance or promotes delamination under cyclic loading [10,11]. Moreover, blade-scale repair logistics (Access by rope-access teams, robotics and drones, nacelle-based repairs, or blade removal; Figure 2) are costly and can require significant downtime. Consequently, materials that combine impact/erosion resistance with the ability to autonomously heal small cracks and restore surface integrity in situ would substantially reduce operating expenditure and increase blade service life [12,13].

Figure 2.

Blade-scale repair: (a) Rope-access teams [14], (b) Rope robotics’ wind turbine blade repairs [15] and (c) Robotic platform with a rich family of repair services [16] (d) Wind turbine blade inspection with drone camera-autonomous flying [17], and (e) Different types of drones [18].

Self-healing coatings have matured considerably since early demonstrations of microcapsule-based healing systems and autonomous polymer repair [19]. Contemporary self-healing strategies fall into two broad classes. Extrinsic systems embed healing reservoirs (microcapsules, nanocapsules, or vascular networks) that release reactive agents on mechanical damage and polymerise to fill cracks; these solutions are attractive because they can deliver rapid, high-locality repair with chemistry tuned to the host matrix [20,21]. The second type is intrinsic self-healing, which relies on reversible or dynamic bonds within the polymer network, e.g., hydrogen bonding [22], supramolecular interactions [23], reversible Diels–Alder linkages [24], or associative exchange chemistries (vitrimers), lowering repeated [25], autonomous restoration of mechanical continuity often under mild thermal or environmental stimuli [26]. Additionally, room-temperature intrinsic self-healing materials offer sustainable and practical solutions. Recent advances in dynamic covalent and non-covalent bonding mechanisms have expanded their applications across coatings, electronics, energy devices, and biomaterials. Continued research is expected to further optimise these materials for versatile, real-world applications [27]. Each approach yields distinct benefits and limitations for LEE mitigation: extrinsic approaches can provide a strong initial repair agent but are single-use per damage site unless coupled with vascular replenishment, while intrinsic systems enable multiple healing cycles but historically suffer from lower virgin mechanical toughness or slower healing kinetics under ambient conditions [28]. These strategies can provide significant solutions to the coating market with anti-erosion and anti-corrosion coatings.

Advances in extrinsic and intrinsic self-healing coatings, such as micro/nanocapsule engineering (Including shell design, core chemistry, and stimuli-triggered release), multifunctional nanocomposite toughening (using silica, graphene derivatives, and ceramic fillers), and dynamic polymer networks (vitrimers, reversible covalent chemistries), have enhanced healing efficiency and mechanical performance in several studies [20,29,30]. Furthermore, applied research specific to wind blades, including rain erosion testing protocols, curvature-aware erosion studies, and lifecycle assessments, has begun mapping laboratory metrics to field outcomes [31,32]. Despite this, few studies have explicitly combined validated erosion resistance, full-scale applicability, and rigorous healing metrics under representative environmental conditions. Standardised testbeds that integrate erosion, mechanical fatigue, and healing are still rare but urgently needed.

This review organises and evaluates the growing literature on self-healing coatings for various applications, especially through the lens of wind-blade LEE mitigation. A summary of the erosion mechanisms includes blade-relevant testing methods. A brief survey of conventional anti-erosion coatings and their failure modes. Self-healing approaches are categorised as extrinsic, intrinsic, and hybrid types, focusing on materials and performance metrics significant to blade leading edges (healing efficiency, adhesion, surface roughness, and environmental stability). This review also discusses practical deployment challenges, scalable applications, cost, standards, and field validation. Research priorities are outlined, along with a suggested roadmap towards deployable self-healing anti-erosion coatings. Throughout, we highlight promising chemistries, representative experimental results, and gaps where targeted research could produce rapid field benefits. The structure of this review outlines that sources were selected based on their publication year, relevance to major coating categories (including polyurethane systems, hybrid coatings, nanocomposites, and intrinsic or extrinsic self-healing technologies), and their technological maturity or industrial applicability. Priority was also given to studies that investigate key performance mechanisms such as erosion resistance, fatigue behaviour, healing efficiency, environmental durability, and field-level validation.

2. Wind Turbine Design and Blade Components

2.1. Wind Turbine Design

Wind turbines are classified into two primary design types: horizontal-axis wind turbines (HAWTs) and vertical-axis wind turbines (VAWTs). In addition, some wind turbines operate using lift forces, while others use drag forces [33], as shown in Figure 3. The VAWT design is often seen as more suitable for urban and built-up areas because it operates more quietly than the HAWT, thanks to fewer moving parts and a lower tip-speed ratio. Unlike HAWTs, which need to continuously yaw (rotate around the vertical axis) to stay aligned with changing wind directions, VAWTs are naturally less affected by wind direction and turbulence, giving them an advantage for use in complex urban wind conditions [6]. However, it should be noted that VAWTs typically have smaller size and lower aerodynamic efficiency than HAWTs. Additionally, in built-up areas, various small-scale wind turbines can be employed, as displayed in Figure 3 [34,35,36].

Figure 3.

Various types of wind turbines [33].

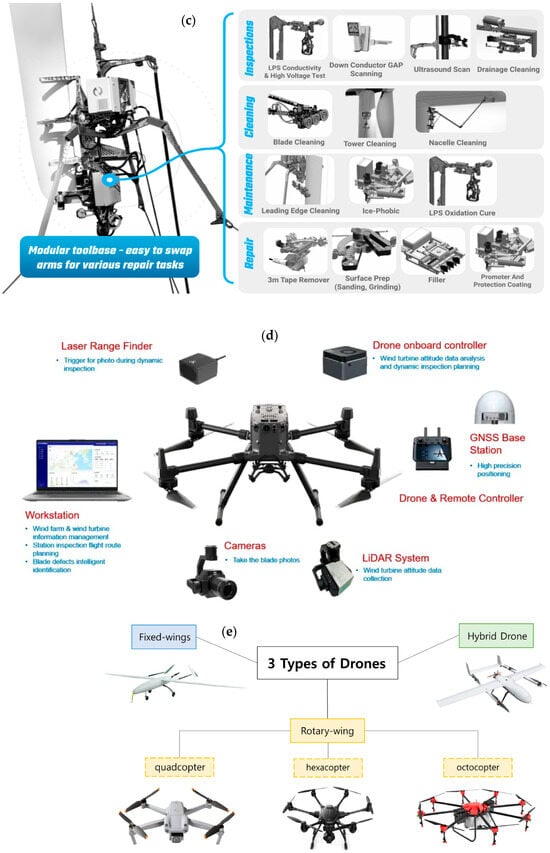

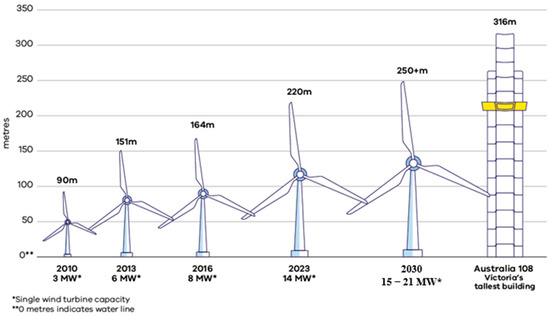

Blade size HAWTs can reach lengths of around 115 m for a 15 MW turbine (Figure 4), weighing roughly 35–45 tonnes. One 15 MW turbine can produce enough electricity in a year to power approximately 20,000 households and save around 38,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions. Therefore, an offshore wind farm equipped with 15 MW turbines and a total generation capacity of 2 GW may require just over 130 turbines. This setup could produce enough electricity to power 1.5 million homes annually [37].

Figure 4.

Offshore wind turbine sizes and power capacity [37].

2.2. Blade Composite Materials and Protective Coating Systems

The main components of a WTB structure include the root, the suction-side skin (also known as the shell), the pressure-side skin, the suction-side spar cap, the pressure-side spar cap, the trailing edge (TE) web, and the leading edge (LE) web (beam is the web with spar cap and is sometimes called spar-cap box), as shown in Figure 5a,b. The TE and LE webs connect the suction-side skin, the pressure-side skin, and the spar caps (Figure 5b). Additionally, foam is incorporated into the trailing edge to enhance structural stability and prevent buckling [38]. The internal beam, comprising webs and flanges, is typically constructed from biaxial laminate skins and a PVC foam core [39]. This beam primarily resists torsional, axial, and bending loads. The sandwich core materials commonly include balsa wood or polyethylene terephthalate (PET) foams, providing an optimal balance between stiffness and weight. The protective surface coating is generally made of polyethylene (PE) or polyurethane (PU), while lightning protection systems employ copper wiring and steel bolts to ensure electrical conductivity and structural safety [40,41].

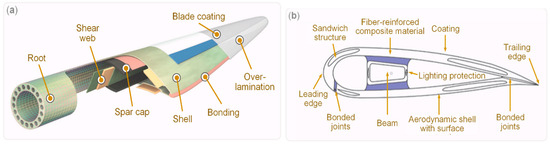

Figure 5.

The main elements of a wind turbine blade: (a) 3D structure and (b) cross-section (Reprinted from Ref. [41] with kind permission from Elsevier).

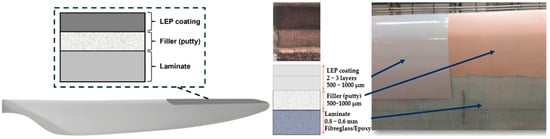

The recent development of composite materials for wind turbine blades (WTBs), composed of laminated composites such as glass-, carbon-, or basalt-fibre-reinforced thermosets, or a thermoplastic matrix such as epoxy, polyester, or Elium, offers high strength-to-weight ratios along with the recent growth in blade sizes [42,43,44]. The substrate acts as the structural core, providing rigidity and load-bearing capacity. Coating systems for WTBs are typically composed of multiple layers, most commonly a three-part structure consisting of a filler, primer, and protective coating (also called a topcoat) [45]. In some cases, the putty filler, usually applied to fill surface pinholes, may be ignored to enhance adhesion between the primer layer, the underlying substrate, and the protective topcoat above. In general, the putty filler and LEP coating (Figure 6) are applied to achieve smooth aerodynamics and protect the blade surface from erosion, UV radiation, and environmental degradation. Blade leading edges are especially vulnerable [46,47]. Various coating application techniques can be used for WTBs, including spray, roller, and trowel [48]. The laminate, filler, and coating blade layers endure harsh environmental and operating conditions, particularly at the blade tip. As the blade tip rotates, it encounters rain or airborne particles; the relative velocity is high, and impact from droplets or particles acts like sandblasting, leading to material removal, surface roughening, and aerodynamic efficiency losses. Conventional protective coating systems usually consist of a filler or putty layer to smooth the surface bonded to the blade composite, and a topcoat that offers abrasion resistance, UV protection, and an attractive finish. For example, PU coatings are commonly selected for their flexibility and abrasion resistance [49,50].

Figure 6.

LEP multilayer configuration on the surface of the rotor blade, on the left [51], and on the right [52].

3. Environmental Degradation Mechanisms of Blade Coating

3.1. Processes and Mechanisms of WTBs Erosion

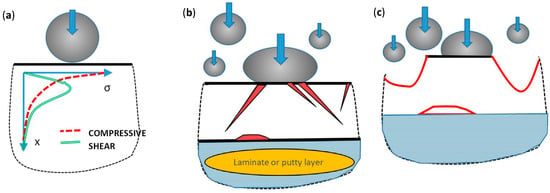

Wind turbines are exposed to various types of LEE, including rain erosion [53] and sand erosion [54]. In general, LEE is caused by the high-velocity impact of raindrops, hail, or insects, which strike at tip speeds exceeding 90 m/s, creating stress waves that degrade the blade surface over time. Additionally, the repeated impacts of liquid droplets, primarily raindrops, along with various environmental stressors, including hail, fluctuations in wind pressure, moisture, insects, sand, dust, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and thermal cycling. When a raindrop hits the blade surface, it creates high contact pressures that propagate stress waves through the protective coating layers [2,55]. These dynamic stresses gradually lead to damage initiation, material deterioration, and fatigue buildup, causing pitting, coating microcracks, interfacial debonding, composite substrate cracking, and surface roughening with repeated impacts, resulting in cumulative damage and blade material loss [7,56]. Figure 7 illustrates the various damage mechanisms involved. The stress field generated by liquid impact on the coating leads to the formation of various types of cracks, including Hertzian, cone, radial, and debonding cracks [2,57].

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the rain erosion mechanism in protective coatings: (a) distribution of stress and propagation of waves; (b) initiation of conical (Hertzian) cracks and interfacial debonding; (c) progressive removal of material and roughening of the surface (Reprinted from Ref. [57] with kind permission from Wiley-VCH).

The sand LEE occurs when sand particles carried by the wind abrade the blade surface, which acts as a micro-abrasive, gradually wearing away the coating, resulting in damage such as sand holes, cracks, and coating spalling, as presented in Figure 8 [58]. This leads to material removal, which leads to a rougher surface, reduced aerodynamic efficiency, and costly repairs [53,54].

Figure 8.

Sand erosion of blade coating: (a) Sand holes; (b) Cracks; (c) Coating peeling [58].

3.2. Icing and UV Degradation of WTBs

In colder climates, ice accretion and impact can form ice on the WTB surface, which can subsequently shed, causing brittle fractures and spallation of coatings. Additionally, frozen precipitation can act as a heavy erosive agent. Furthermore, wet ice growth usually poses a greater challenge to wind turbine operations than dry rime ice growth (Figure 9). This is mainly due to greater degradation of aerodynamic characteristics under glaze-icing conditions [59]. Wet ice growth typically poses a greater threat to wind turbine operations than dry rime ice growth. This is primarily due to the more pronounced degradation of aerodynamic characteristics under glaze-icing conditions [60,61]. While hailstones and raindrops are relatively large particles that contribute significantly to erosion, other forms of precipitation, such as snow and drizzle, composed of soft, very fine particles, respectively, exert much milder effects and are not considered primary causes of leading-edge erosion (LEE).

Figure 9.

WTBs under icing conditions [62].

UV degradation is another concern, as UV radiation weakens polymeric bonds in coatings, initiating chain scission, embrittlement, and discolouration, thereby further increasing the mechanical wear of the WTBs [63]. Additionally, cyclic fatigue from repeated loading due to rotational dynamics, gust variations, and droplet impacts can cause fatigue cracking, even in elastomeric coatings designed for flexibility [7,64]. These processes often work together, accelerating the progression from micro-damage to larger erosion zones.

3.3. Micromechanism of the LEE

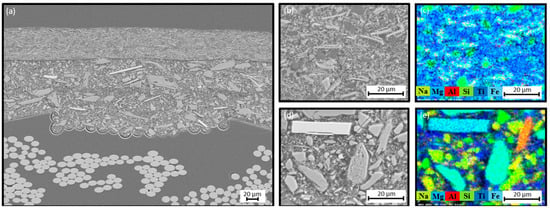

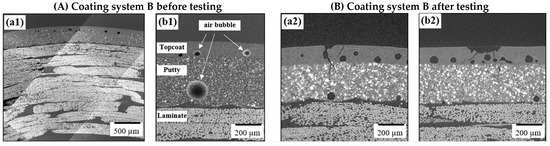

Understanding the microscale erosion mechanisms is essential for developing effective blade protection against erosion. Mishnaevsky et al. [2] investigated the microscale of two industrially applied leading-edge coating systems (A and B) (Figure 10 and Figure 11) using SEM and X-ray computed tomography (CT) scan, since rain-erosion testing revealed distinct damage mechanisms between both coating systems. Coating A contained elongated particles (Al, Si and K) aligned parallel to the surface, where cracks initiated along particle/matrix interfaces due to stiffness mismatch. Coating B exhibited numerous bubbles and voids, where cracks propagated from surface bubbles into deeper layers.

Figure 10.

(a) SEM image showing a cross-section of coating system A. (b) SEM close-up of the top coating layer. (c) Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) image corresponding to the same area as (b). (d) SEM close-up of the putty layer. (e) EDS image corresponding to the same area as (d) (Reprinted from Ref. [2] with kind permission from Elsevier).

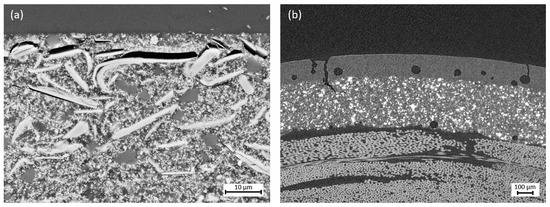

Figure 11.

(a) SEM image showing a cross-section of coating system B. (b) SEM close-up of the top coating layer. (c) Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) image corresponding to the same area as (b). (d) SEM close-up of the putty layer. (e) EDS image corresponding to the same area as (d) (Reprinted from Ref. [2] with kind permission from Elsevier).

Different forms of damage were observed on the specimens’ surfaces. Coating system A contains numerous elongated particles, primarily aligned parallel to the surface. Following the rain erosion test, cracks were observed to develop along these elongated particles near the surface (Figure 12a). This cracking is likely due to differences in stiffness between the elongated particles and the surrounding matrix. In contrast, this type of cracking was not observed in coating system B (Figure 12b). Instead, coating system B exhibited numerous bubbles within both the topcoat and the putty layers (Figure 12b and Figure 13A,B). After testing (Figure 13B), cracks were observed propagating from the surface to the bubbles in the topcoat and subsequently extending further into the putty layer. Another study by Nash et al. [65] also concluded that the presence of voids and air bubbles within the coating system is related to the application method or the mixing technique used during coating preparation. Such imperfections can act as initiation points for erosion damage to the WTBs once exposed to rain impact. As noted, the air bubbles observed under microscopic analysis originated in the coating process and later developed into pits and gouges during erosion testing. This finding highlights the importance of optimising both coating application and preparation methods to minimise bubble formation and enhance erosion resistance. Additionally, the heterogeneities, voids, and weak interfacial bonding among the top coating, the putty, and the laminate strongly influence the initiation and progression of erosion, leading to various types of damage, including cracks from voids, particle separation, and layer debonding. Consequently, improving coating manufacturing quality and uniformity is critical to enhancing rain erosion resistance of the WTBs [2,53].

Figure 12.

The cross-section of coating systems: (a) SEM image shows the black lines next to the white elongated particles represent cracks. (b) A CT scan illustrates cracks extending from the surface to the bubbles within the topcoat (Reprinted from Ref. [2] with kind permission from Elsevier).

Figure 13.

The cross-sections of the coating system B: (A) Before testing (a1) overview SEM image, and (b1) CT scan of the topcoat and putty after testing, showing dark cracks near elongated white filler particles. (B) After testing: (a2,b2) CT scan illustrates cracks extending from the surface to the bubbles within the topcoat and putty [53].

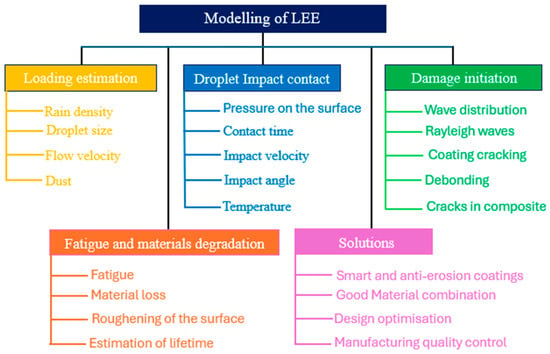

4. Modelling LEE

Several factors can affect erosion rates, such as site-specific and operational parameters. Wind speed and rotational velocity determine the kinetic energy of impacting particles and droplets, directly affecting damage depth [7]. Particle velocity and trajectory (governed by tip speed and blade pitch) control impact angle and stress distribution. Temperature and humidity influence coating stiffness and viscoelastic response; lower temperatures generally make materials more brittle, while high humidity speeds up hydrolysis and moisture-induced degradation [2]. Environmental exposure factors such as UV intensity, precipitation frequency, and salinity also influence degradation rates and coating longevity. Understanding these factors enables predictive modelling of erosion behaviour and aids in the optimisation of materials tailored to site-specific conditions [66,67,68]. Modelling LEE involves four main stages: estimating loading conditions, such as rainfall intensity and velocity; simulating droplet impact to determine pressure and time; modelling deformation and damage initiation, such as wave propagation and crack formation; and predicting long-term fatigue and material degradation, such as material loss and roughening [69,70]. The final step uses the insights from the modelling to inform the design and selection of new smart and protective coatings [28]. The goal is to develop more durable, resilient, and long-lasting solutions. Figure 14 presents the steps of LEE modelling to assess material performance and to design effective solutions, such as new coatings.

Figure 14.

Steps of LEE modelling.

To complement experimental development, a wide range of computational approaches have been employed to understand and optimise self-healing processes. Atomistic simulations, such as density functional theory and molecular dynamics [71,72], have provided molecular-level insights into reversible bond dynamics and interfacial interactions within polymer matrices. Mesoscale modelling approaches, including coarse-grained molecular dynamics [73] and Monte Carlo simulations [74], enable investigation of diffusion and phase behaviour over longer timescales. At the continuum level, finite element methods (FEMs) [75] are extensively used to simulate mechanical damage, stress evolution, and healing kinetics under operational loading. Each computational method, however, presents trade-offs: while atomistic simulations offer high-resolution chemical detail, they are computationally intensive for large systems; mesoscale models improve scalability but may oversimplify reaction mechanisms [76]. FEM stands out for its ability to integrate thermo-mechanical and moisture-dependent effects within a unified multiphysics framework. This capability makes FEM particularly valuable for simulating real-world conditions, such as erosion, impact, or fatigue, thereby enabling accurate prediction and optimisation of self-healing performance in advanced coating systems, such as polyurethane–urea and epoxy-based materials [51].

5. LEE and Microplastic Pollution

Wind energy requires rapid scaling, especially for offshore wind, where turbines will face harsher environmental loading. Blades can reach lengths of around 115 m for a 15 MW turbine, weighing roughly 35–45 tonnes, and operate in harsh environments where rain, dust, and debris impact surfaces at velocities exceeding 110 m/s near the blade tips [77]. These conditions lead to progressive erosion and surface degradation, reducing aerodynamic efficiency by up to 20% and shortening the operational lifespan of turbine components, especially for offshore wind blades [28]. While composites have enabled lightweight, efficient blades, their environmental durability remains a critical bottleneck. LEE and saltwater corrosion (For offshore blades) accelerate performance losses and drive costly maintenance. In parallel, sustainability concerns are intensifying, as eroded polymers contribute to microplastic pollution, while large-scale ORE installations interact with sensitive marine ecosystems [78]. Addressing these challenges requires an integrated approach that couples advanced materials with environmental stewardship to mitigate losses in generating efficiency for offshore WTBs [79].

Despite recent progress in polyurethane (PU)-based coatings, existing blade protection systems still exhibit limited durability under combined stresses such as rain erosion, particles, and contamination. While more durable coatings offer promise, they need to be validated in harsh environments. It is also necessary to employ recyclable composites, such as acrylic-based thermoplastic liquid resin and vitrimer epoxy-based resin, in manufacturing the polymer fibre-reinforced composite (laminate) of the WTBs. These composites significantly contribute to the decarbonisation of wind energy, decrease greenhouse gas emissions, and improve sustainability. LCA studies suggest that self-healing composites, such as vitrimer-based ones, could cut the carbon footprint of blades by approximately 20%; however, industrial use remains limited. Microplastic emissions from WTB erosion are a growing concern. A recent study on offshore WTBs in the Dutch North Sea estimated that a 15 MW offshore turbine with PU-based LEP releases about 240 g of microplastic emissions annually from a polyurethane-based LEP system, or around 6 kg over 25 years. Another study estimated that mass loss due to blade surface erosion for Danish wind farms ranges from 30 to 540 g per year per blade; for offshore turbines, the higher end of the range is 80–1000 g/year per blade, while onshore turbines show much lower loss (8–50 g/year per blade). When scaled across wind farms, this represents an increasing environmental footprint. Ireland currently lacks site-specific estimates, and the ecological risks associated with current and future WTB microplastics in the Irish Sea and Atlantic benthic ecosystems remain unquantified. At the same time, it is crucial to incorporate both recyclable composites and anti-erosion, self-healing coatings into offshore structures. These innovations could help reduce erosion and biofouling, aligning with EU circularity goals.

The leading edge of WTBs is constantly exposed to complex environmental and mechanical stresses during operation. These stresses arise from high-velocity impacts, cyclic aerodynamic loads, and long-term exposure to the elements. The combination of these factors causes progressive surface degradation, commonly known as LEE, which remains a primary cause of reduced aerodynamic efficiency and structural damage in wind energy systems [80,81]. Erosion damage typically initiates at the microscopic scale and gradually develops into pits, grooves, and significant material loss [82]. Several factors affect the erosion rate, as illustrated in Figure 15. These surface degradations alter the blade’s geometry, thereby diminishing its aerodynamic and hydrodynamic performance.

Figure 15.

Factors affecting the erosion rate.

6. Conventional Protective Coatings

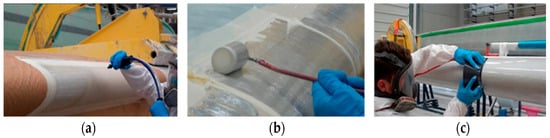

Protective coatings play a critical role in the durability and performance of WTBs, which are exposed to harsh environmental conditions, including rain erosion, sand and particle erosion, UV radiation, humidity, and thermal cycling. Studies in the literature related to erosion-protective coatings find that polymer-based systems, such as polyurethane (PU), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and epoxy-based films, are widely used as coatings on blade surfaces [83,84,85]. Despite recent advancements in polyurethane (PU)-based coatings, existing blade protection systems still exhibit limited durability when subjected to combined stresses, such as rain erosion, particles and contamination [86]. While more durable coatings hold promise, they need to be validated under harsh offshore conditions. There are several coating application methods for WTBs, including spray, roller, and trowel (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Coating application methods of LEP, i.e., (a) spray; (b) roller; (c) trowel [52].

For wind-blade LEP, the challenge of coating materials is inherently multifunctional. The challenge is in selecting the optimum LEP system to mitigate losses in generating efficiency. Therefore, an effective protective coating required to (i) resist high-velocity droplet and particle impact (hardness and toughness), (ii) maintain low surface roughness and aerodynamic fidelity, (iii) exhibit strong adhesion to composite substrates and compatibility with common blade surface preparations, (iv) provide long-term UV, moisture and temperature stability, and (v) demonstrate healing performance that restores barrier function and surface geometry rapidly enough to prevent progressive erosion or substrate exposure [87,88]. Meeting all these criteria in a sprayable, scalable coating system with acceptable cost adds further constraints. The wind-energy context also emphasises operational metrics that laboratory work often omits, such as multi-year cyclic exposure, large-area application variability, and repair strategies suitable for blade-scale logistics [89,90].

Despite their widespread adoption, conventional coatings face several limitations. Over time, repeated exposure of WTBs to rain or particles can cause microcracks, voids, adhesion loss, and delamination between layers or at the substrate interface. These defects act as pathways for erosion escalation, leading to premature coating failure or blade surface damage [83,91]. Further, the increasing size of WTBs and higher tip speeds exacerbate erosion rates, making anti-erosion coatings more challenging to LEE. Application and environmental factors also affect performance: inadequate surface preparation, sub-optimal mixing or application of coating materials, or exposure to harsh conditions (offshore salt spray, extreme temperatures) reduce service life and increase maintenance burdens [87,92].

From a lifecycle and cost perspective, while conventional coatings are cost-effective relative to no protection, recurring inspections, repairs, and recoating represent significant operational expenditure for wind farms. The blade protection coating market continues to grow in response to demand for longer blade life and lower maintenance costs [93]. In summary, conventional protective coatings remain the backbone of wind blade surface protection strategies, but as operational conditions become more severe and blades grow larger, their limitations become more apparent, underscoring the need for improved solutions [94,95].

Conventional coatings alone may not reliably arrest damage initiation and propagation at the blade leading edge under high-velocity rain or particle impact, especially over extended service lives. The integration of self-healing functionalities into LEP systems offers the potential to autonomously repair micro-damage, restore protective film integrity, reduce maintenance interventions and extend blade lifespan in this critical zone [96,97].

7. Smart Nano Protective Coatings

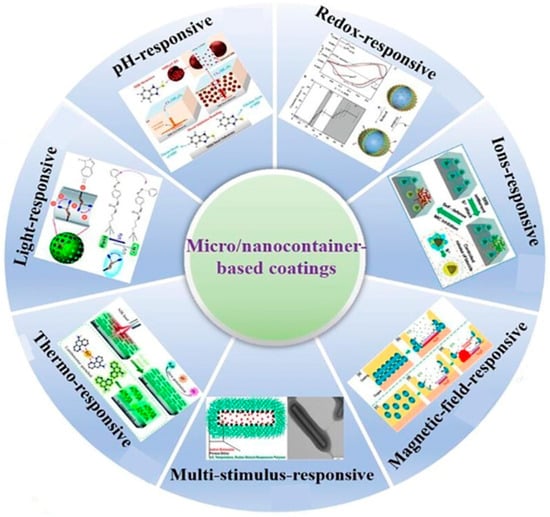

Smart coatings are advanced films and surface layers that can detect and respond to external stimuli, such as temperature, chemicals, light, or mechanical damage, through functions including self-healing, antimicrobial activity, corrosion protection, and colour-changing behaviour [98]. They are increasingly used across renewable energy, automotive, aerospace, construction, marine, healthcare, electronics, and smart infrastructure sectors. Developments in nanotechnology, stimuli-responsive polymers, and nanoengineering drive their expansion [99,100]. Figure 17 illustrates the application of micro- and nanocarriers across various fields to enhance the longevity and effectiveness of protective coatings in challenging environments [101]. Recent studies highlight promising directions for LEE mitigation. Incorporating inorganic, organic, and composite materials into the development of smart coatings is vital to advancing these coatings. Inorganic materials generally offer greater durability and resistance to environmental conditions, while organic materials provide flexibility and ease of processing [102].

Figure 17.

Different stimulus-responsive micro- and nanocontainer coatings that adapt to changes in temperature or pH, with applications in medicine, materials science, and environmental protection [101].

Moreover, polymeric materials and their composites have significantly improved the functionality and versatility of smart coatings across a wide range of industrial applications [103,104]. Researchers can advance sustainability efforts by investigating the use of natural raw materials to improve coating degradability and by incorporating non-toxic or low-toxicity additives to reduce environmental impact. With these factors in mind, smart coating materials are set to play a transformative role in the industry, offering significant growth opportunities and expanding the market potential for innovative, eco-friendly coatings. The smart coatings market is experiencing significant growth with a projected Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR), generally cited between 15% and 18% (some sources indicate as high as 23.5%), and widely diverging market size estimations for 2033, typically ranging from approximately USD 13 billion to over USD 40 billion [105,106]. Overall, the strong growth indicates a robust, expanding market driven by demand for advanced materials with multifunctional properties, enhanced durability, and reduced maintenance costs across various industries.

The advent of nanotechnology has significantly advanced the coating industry by enabling the development of innovative coating formulations and multifunctional coating systems [107]. Examples of nanomaterials used in these applications include carbon nanotubes (CNTs), which enhance physical strength and conductivity; nanoclays, which improve barrier performance and offer cost-effectiveness; and titanium, cerium, and zinc oxide nanoparticles, which provide excellent UV absorption due to their high efficiency and stability within the coating film [45,108].

8. Self-Healing Protective Coatings

Self-healing coatings are a kind of smart material that can automatically repair minor damage, such as micro-cracks, restoring the coating’s integrity [109]. Therefore, these coating systems can, to varying degrees, achieve a combination of self-healing, anti-erosion, anti-icing, omniphobic, self-cleaning, anti-staining, anti-biofouling, anti-particle/sediment erosion, and anti-friction, which can improve long-term durability and prolong the operational life of both wind and tidal turbine blades across various operating sites and environmental conditions [82,110]. For instance, exposure to low temperatures can cause PU coatings to transition from a ductile to a brittle state, significantly increasing their susceptibility to impact-induced damage [111]. Self-healing coatings should play a vital role in determining their resistance to rain erosion. An effective protective coating must strike a balance between hardness and elasticity. Enhanced durability relies on lower stiffness and hardness, combined with the ability to efficiently dissipate impact energy and rapidly recover its original shape. Elastic coatings, in particular, are designed to absorb impact loads and prevent the initiation of cracks during the early stages of LEE [112,113].

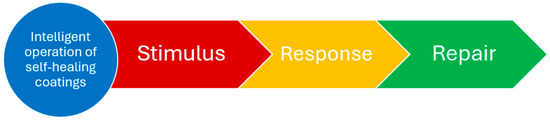

Self-healing coatings are vital for the LEP of WTBs because the high tip speeds of modern turbines cause significant erosion from rain, dust, and other particles. These coatings are designed to repair damage autonomously by initiating chemical reactions that fill cracks and restore worn surfaces. The concept is inspired by biological systems capable of self-repair, such as the natural healing of skin [114,115]. The smart features of self-healing protective coating systems designed for LEP can be described by three interconnected actions: sensing damage as a stimulus, activating a response by releasing healing agents, and repairing the damaged surface (Figure 18). In practical terms, these coatings work conditionally; when erosion or micro-damage occurs, the healing process is triggered. This makes them responsive and adaptable materials that preserve structural integrity over time [116]. Self-healing coatings for leading-edge erosion combine preventive and corrective functions by embedding healing agents, erosion-resistant additives, and surface-protective features such as hydrophobic, anti-icing, or self-cleaning components within a durable coating matrix. This multifunctional design provides a sustainable and long-lasting solution for reducing erosion damage, extending service life, and lowering maintenance costs [117]. By automatically repairing damage, self-healing coatings extend the blade’s lifespan and prevent performance loss, thereby reducing maintenance costs and downtime.

Figure 18.

Intelligent process of self-healing coatings.

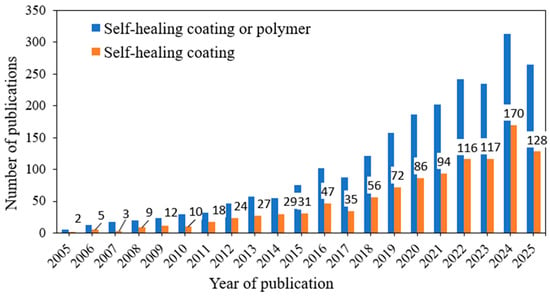

As shown in Figure 19, research on self-healing coatings has grown considerably over the past two decades, surpassing studies on both self-healing and polymer-based systems.

Figure 19.

The number of publications indexed by Scopus from 2005 to 2025 whose titles, abstracts, or keywords include the following terms (“self-healing polymer”) or (“self-healing coating”) Blue columns, and (“self-healing coating”) Orange columns, (data from Web of Science, 2025).

Self-healing coatings have evolved considerably since the first demonstrations of microcapsule-based repair and autonomous polymer restoration [118]. Contemporary self-healing strategies are broadly classified into two main categories: extrinsic and intrinsic coating systems [19,119]. Extrinsic and intrinsic refer to the use of extra healing agents to facilitate self-healing [120]. Intrinsic self-healing systems, by contrast, may rely on internal chemical interaction, such as non-covalent interaction or dynamic covalent bonds within the polymer network itself. Another intrinsic self-healing system is physical supramolecular interactions (Molecular interdiffusion) [23]. Figure 20 presents a flow chart of the main self-healing coating mechanisms.

Figure 20.

Self-healing coating mechanisms.

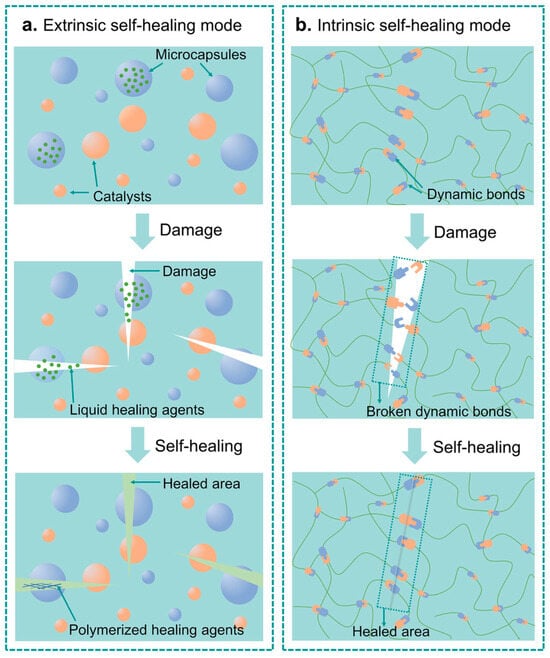

Additionally, the terms “autonomous” and “non-autonomous” refer to whether the healing process occurs independently or requires external intervention. Autonomous systems can self-heal without external stimuli, whereas non-autonomous systems depend on external triggers, such as heat, light, or other environmental inputs, to initiate or support the healing process [121,122]. Extrinsic self-healing systems incorporate embedded reservoirs, such as microcapsules, nanocapsules, or vascular networks that store reactive healing agents [123]. When mechanical damage occurs, these reservoirs rupture and release the agents, which subsequently polymerise to seal cracks and restore integrity, either autonomously or non-autonomously. These approaches enable rapid, localised repair and can be chemically tailored to complement the host matrix [20,118]. Figure 21 presents the mechanisms of extrinsic self-healing and intrinsic self-healing coating.

Figure 21.

Mechanisms of (a) extrinsic self-healing and (b) intrinsic self-healing [124]. (Reproduced with permission, Copyright, Wiley-VCH).

8.1. Intrinsic Self-Healing

Intrinsic self-healing approaches repair damage by enhancing the movement of polymer chains at the damaged site, allowing the material to flow and restore its continuity. This process depends on reversible physical or chemical interactions that enable autonomous healing. The connection between polymer architecture, mechanical performance, and healing efficiency is likely to attract more attention due to its industrial potential. Typically, these systems are activated by external stimuli such as mechanical stress, heat, light, temperature fluctuations, or pH changes. A key advantage of intrinsic self-healing coatings is their ability to undergo multiple healing cycles without requiring additional healing agents [125,126]. Intrinsic self-healing enables materials to recover repeatedly, often restoring their properties nearly to their original condition by reforming fractured polymer bonds. These healing mechanisms are mainly classified into molecular chain interdiffusion, segregation, and reversible bonding, whether covalent or non-covalent [118]. Healing occurs through the movement and reconnection of polymer chains across damaged interfaces. Molecular interdiffusion and segregation facilitate entanglement and adhesion at the fracture surface. The driving forces behind these processes include concentration gradients and variations in surface tension. This molecular mobility allows effective damage recovery across various scales [127].

Furthermore, advances in dynamic covalent and non-covalent chemistries have significantly expanded the potential of intrinsic self-healing materials for applications in coatings, various types of polymers, composites, metal and ceramic. Continued research is focused on optimising these systems for faster healing, enhanced toughness, and long-term durability under operational conditions [123,128]. Furthermore, intrinsic self-healing coatings rely on their chemical bonds to reform when exposed to external stimuli [129]. Intrinsic self-healing materials possess inherent repair capabilities that operate without external healing agents, enabling multiple healing cycles [10]. Reversible non-covalent bonds can be incorporated onto the filler surface, enabling the fillers to act as part of the healing agent while simultaneously reinforcing the coating polymer matrix. Dynamic covalent bonds, such as imine, disulfide, and Diels–Alder (DA) crosslinks, offer an alternative approach to creating self-healing coatings [130,131]. These types of bonds can undergo chain-exchange reactions or molecular rearrangements when exposed to external stimuli such as light, temperature changes, or pH variations. In polyurethane urea (PUU) polymers, this behaviour can be achieved through the incorporation of dynamic covalent bonds, such as disulfide linkages or Diels–Alder linkages [24], or through reversible non-covalent interactions, including metal–ligand coordination, ionic interactions, and hydrogen bonding [22]. These dynamic linkages allow multiple autonomous healing cycles, typically activated by mild thermal or environmental stimuli [132]. These mechanisms are especially promising for polymer coatings that require maintaining specific functional surface chemistries [133].

A notable advancement in intrinsic self-healing coatings is the development of a bio-inspired MXene/polyurethane (f-MXene@PU) coating. This coating exhibits exceptional active and passive anti-corrosion performance specifically for magnesium alloys. The polyurethane matrix utilises the synergistic effects of disulfide and hydrogen bonds, allowing for autonomous self-repair at room temperature. Electrochemical analyses reveal outstanding corrosion resistance, with a remarkably low current density of 5.1 × 10−11 A cm−2 and a self-healing efficiency of 140%. These impressive features arise from the dynamic reversibility of the polymer’s internal bonding network [134]. In a similar vein, Hu et al. designed an innovative polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) coating cross-linked via coordination bonds between 2-(2-benzimidazolyl)ethanethiol (BET) and zinc ions. The reversible coordination interactions between zinc ions and BET ligands enable the coating to autonomously self-repair in both air and simulated seawater environments. This coating, engineered for marine applications, demonstrates excellent antifouling and self-healing capabilities in both air and simulated seawater, thanks to the reversible nature of its metal-ligand coordination bonds [135].

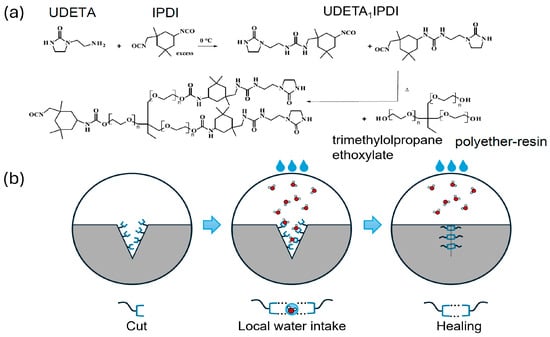

Experimental and modelling studies were conducted by [26,51] to establish a validated framework for designing moisture-responsive, intrinsic self-healing polyurethane-urea (PUU) coatings that can extend the operational lifespan of WTBs. The 1-(2-aminoethyl)imidazolidinone (UDETA)-modified PUU coating demonstrated autonomous self-healing of surface cracks via dynamic hydrogen bonding activated by environmental humidity (Figure 22). Stress-assisted moisture diffusion accelerated healing at crack tips, achieving over 80% crack closure within 24 h at 50% relative humidity. The computational modelling in this study and the experiments conducted by Wittmer et al. [26] confirmed that the coating maintains structural recovery without significant thermal gradients or external stimuli. The integration of Gaussian process regression and finite element modelling provided quantitative design insights for optimising UDETA content, coating thickness, and curing conditions. In general, intrinsic self-healing offers a sustainable approach to creating durable, reusable polymer-based coatings.

Figure 22.

(a) Mechanism of the self-healing and (b) synthesis of UDETA-based PUU coatings [51].

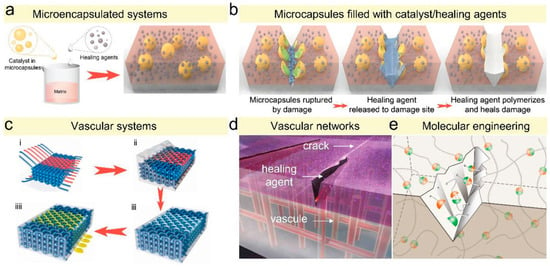

8.2. Extrinsic Self-Healing

While intrinsic systems are more suitable for small-scale repairs, extrinsic systems can repair larger damage up to 35 mm [136]. Extrinsic self-healing systems utilise embedded reservoirs, such as microcapsules, nanocapsules, or vascular networks that hold reactive healing agents [116,137]. When mechanical damage occurs, these reservoirs rupture, releasing the healing agents that flow into the damaged area and crosslink/polymerise to seal cracks and cure, restoring structural integrity. This method was first systematically introduced by White et al. in 2001, who pioneered the development of self-healing materials using an extrinsic microencapsulation approach that incorporated dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) microcapsules and a Grubbs catalyst [138]. This healing process can occur autonomously or be activated by external stimuli, depending on the system’s design [118,139]. The most common extrinsic self-healing materials utilise encapsulated liquid healing agents or solid organic and inorganic inhibitor functional compounds. Numerous studies have investigated strategies that employ encapsulated liquid healing agents to achieve autonomous repair functionality, especially for epoxy- and PU-based coatings [118].

Figure 23 presents conceptual models of two extrinsic self-healing coatings developed over the past few years. The first approach involves microcapsules filled with healing agents (Figure 23a,b). The healing agents, such as liquid monomers that can quickly polymerise and crosslink to form a solid, are sealed inside microcapsules synthesised by either interfacial polymerisation or the sol–gel method [140]. Although effective in producing self-healing coatings, this method has limitations: the microcapsules can be used only once, as their contents are exhausted after activation, and damage repair occurs only when cracks intersect the capsules directly [141]. The second approach mimics biological vascular systems, where healing agents are delivered through a network of microchannels or hollow fibres embedded within the coating (Figure 23c) [142]. Channel diameters range from hundreds of nanometres, as achieved with electrospun hollow fibres, to hundreds of micrometres with glass micropipettes, glass fibres, or polymer tubes [142,143]. In this system, when a crack reaches the channel network, healing agents are transported from other regions to the damaged area, allowing the repair of larger macrocracks (Figure 23d) and enabling repeated healing at the same site. However, the vascular method also presents challenges. Proper interfacial compatibility between the tubular vessels and the polymer matrix is essential; otherwise, stress concentrations may occur, leading to cracks propagating along the interface rather than breaking the channels. This issue is particularly significant in systems with relatively large channels. Conversely, in microscopic channels, the release of healing agents can be restricted by capillary forces, thereby limiting overall healing efficiency [143,144,145].

Figure 23.

Illustration of some designs for self-healing coatings: (a,b) Schematic diagrams show the formation of microcapsules containing a catalyst and a healing agent, which are embedded into microcapsule-based self-healing coatings. When cracks occur, the capsules rupture and release the healing agent, which polymerises to repair the damaged area. (c) A schematic of a vascular-based healing system illustrates an interconnected network that transports healing agents. (d) When the coating is damaged, the vascular channels break and release the healing agent, restoring protection. (e) A schematic of a polymer-based intrinsic coating with reversible chemical bonds shows how the material can recover from molecular-level damage [145]. (Reproduced with permission, Copyright, Wiley-VCH).

Furthermore, although current microcapsule-based self-healing coatings perform well under favourable and standard laboratory conditions, they often fail to sustain effective repair functions in harsh environments, especially at very low temperatures, which are common in real-world applications such as WTBs and aerospace structures [146]. Dong-Min et al. [147] developed a dual-microcapsule self-healing coating tailored for low-temperature conditions. In their study, the coatings were intentionally damaged at −20 °C, with silanol-terminated polydimethylsiloxane (STP) acting as the healing agent, while dibutyltin dilaurate (DD) was released from ruptured microcapsules to catalyse the repair. The healing process was successfully visualised using fluorescent dye, confirming efficient restoration at subzero temperatures.

The healing agents are sensitive to oxygen and moisture and have been effectively protected using durable shell materials such as polyurea (PU), which prevent premature degradation. Furthermore, modifying the microcapsule surface by introducing hydroxyl or amino functional groups significantly enhances their adhesion to the PU matrix, thereby addressing interfacial compatibility issues. As a result, the microcapsule approach has become a widely adopted and extensively researched method for developing extrinsic self-healing PU materials. For example, the study by Keller et al. [148] demonstrated that the effectiveness of extrinsic self-healing in erosion-resistant coatings depends strongly on the chemistry and viscosity of the healing agent. The epoxy-based coating with a single-component, isocyanate-based healing agent achieved successful self-healing, reducing mass loss by nearly 300% compared to a non-healing control. In contrast, the elastomeric poly(dimethyl siloxane) (PDMS)-based system failed to heal effectively due to its high viscosity and slow reaction kinetics. The study further showed that solvent-based healing was ineffective under erosive conditions. Overall, low-viscosity, reactive agents enable more efficient recovery from erosion damage in microcapsule-based coatings. A recent study in the literature has pursued both chemical modifications and structural innovations to achieve significant performance improvements. For example, Liu et al. [149] developed a PU-fluorinated silicone–microcapsule–silica (PFPMS) as a superhydrophobic antifouling coating with excellent mechanical and self-healing properties. In this coating, isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI) and modified graphene oxide (PGMAm/GO) were encapsulated within PU microcapsules through in situ polymerisation and then uniformly dispersed in an amino-terminated fluorinated polydimethylsiloxane (AHT-FPDMS) matrix. When the material is damaged, the released IPDI reacts quickly with the amino groups in the matrix, enabling efficient self-healing. This process restores up to 92.21% of the original tensile strength and 94.35% of the elongation at break within just 30 min.

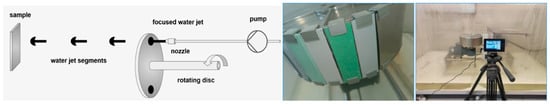

8.3. Characterisation and Testing of Self-Healing

To assess healing efficiency and long-term durability, various characterisation and testing techniques for self-healing coating involve a combination of mechanical, chemical, electrochemical, microscopic and environmental analyses. Mechanical tests, including pull-off adhesion and scratch resistance, quantify the coating’s restored mechanical integrity and hardness. Electrochemical techniques, including electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and potentiodynamic polarisation, provide insights into the corrosion resistance and barrier properties of healed coatings over time. Microscopic characterisation methods, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), optical microscopy, CT-scanning, and fluorescence imaging, are employed to observe crack closure, surface morphology, and distribution of healing agents and to assess coating homogeneity. Surface characterisation techniques such as contact angle goniometry determine surface energy and wettability, which influence healing agent diffusion and adhesion recovery. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) provides insights into viscoelastic behaviour, including storage modulus and energy dissipation during healing [76]. Environmental and ageing tests, such as salt spray exposure, UV radiation, and thermal cycling, are performed to simulate real operating conditions and assess the durability of the self-healing mechanism under long-term or harsh environments [150]. In addition, several rain erosion resistance test methods, such as the pulsating jet erosion test (PJET) (Figure 24), droplet impact erosion mill (DIEM) test (Figure 24), or the whirling arm rain erosion (WRRE) (Figure 25) test, and simulate real operational conditions to evaluate the coating’s self-healing response under repeated waterdrop impact loading [151,152,153,154]. These complementary techniques offer a comprehensive understanding of the coating’s self-healing performance and reliability.

Figure 24.

Pulsating jet erosion test (PJET) (Left) [155], test specimen under DIEM test [156] (Right).

Figure 25.

WRRE tester at Offshore Renewable Energy (ORE) Catapult [152].

9. Challenges and Outlook

9.1. Multifunctional Coatings and Advancing TRLs: Benefits and Current Limitations

The integration of multifunctional features, such as self-healing and anti-erosion properties, significantly enhances resistance to environmental and operational conditions. This is achieved by enabling real-time monitoring of coating integrity and enhancing the manufacturing and application processes [82,157]. However, extrinsic self-healing coatings face several challenges. The complexity and high cost associated with fabricating and encapsulated micro- or nanocontainers limit large-scale production and commercialisation. Another major limitation of active erosion and corrosion protection is the finite lifespan of the self-healing mechanism. Once the active agents are depleted, the coating loses its self-repair ability.

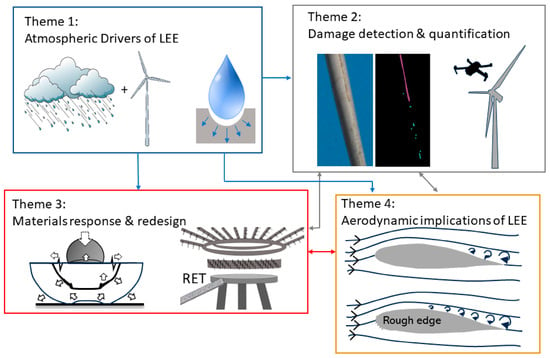

Advancing the technology readiness levels (TRLs) of solutions to mitigate or reduce LEE requires multidisciplinary research spanning four interconnected themes (Figure 26). Theme 1 addresses the atmospheric drivers of LEE, requiring focused research in atmospheric science to characterise the environmental conditions that contribute to erosion. Theme 2 concentrates on the detection and quantification of blade damage, utilising advances in imaging, image processing, and acoustic monitoring. Theme 3 examines blade response, redesign, repair, and protective strategies, involving materials science expertise and various rain erosion testers (RETs) to develop and validate durable solutions. Theme 4 investigates aerodynamic performance deterioration caused by LEE, encompassing aerodynamic studies to evaluate flow alterations and estimate related power losses. Across all four themes, ongoing progress depends on improvements in computational modelling, data analytics, and advanced measurement technologies. A brief overview of each theme is provided in Figure 26 below [31,158].

Figure 26.

Schematic representation of the four LEE themes. Arrows indicate the primary information links between the themes [31].

Another significant challenge in the field is the standardisation and certification of self-healing coatings. Currently, there is no unified framework to evaluate functionality, durability, biocompatibility, or recyclability. The absence of consistent testing protocols makes it difficult to compare results across studies and products. This lack of standardisation ultimately hinders large-scale commercialisation and market acceptance of self-healing coatings [159].

Future research should focus on developing novel healing mechanisms and optimising strategies to maximise self-healing efficiency without compromising material properties. Concentrate on overcoming these challenges to improve efficiency and promote industrial adoption [118]. Moreover, simplifying synthesis procedures and adopting environmentally friendly, green processes are essential to accelerate the practical implementation of self-healing materials [74]. Exploring various self-healing strategies, especially those based on detection, actuation, and healing principles, such as improving system durability, simplifying fabrication methods, and hybrid approaches integrating multiple self-healing mechanisms, could be highly beneficial. For instance, incorporating visual damage-detection features, such as colourimetric changes in self-healing coatings, may provide practical solutions [160].

9.2. Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) Assessment of Anti-Erosion and Self-Healing Coating

The following TRL assessment is based on this literature survey, which outlines technologies that are commercially established or in field testing, coating solutions that are approaching industrial applicability, and those that remain in early-stage laboratory development.

- (a)

- Technologies nearing industrial implementation (High TRL: 6–9)

These anti-erosion coating systems have demonstrated robust performance in extended laboratory testing and have either undergone field trials or are already used in pilot-scale turbine operations:

- Polyurethane (PU) elastomer-based LEP coatings: Widely used in the wind industry, PU coatings remain the benchmark system [161], with TRLs of 7–8. Several commercial products have been validated on full-scale blades under offshore conditions [162].

- Elastomer-reinforced hybrid coatings (e.g., PU–siloxane blends): These coatings exhibit improved erosion resistance and flexibility and have been tested on operating turbine blades [149]. Their TRL is typically 6–7, reflecting readiness for broader industrial adoption.

- Structural tapes and overlays (erosion protection tapes): Already commercially available and used in field repairs, these systems hold TRLs of 8–9, representing full industrial maturity [8,9].

- Nanocomposite-enhanced protective coatings (e.g., silica-, nanoclay-, or graphene-modified PU): Several formulations have reached TRL 6 due to successful field-level water-erosion and UV-exposure trials. These materials show improved durability but require further long-term validation [29,30].

- (b)

- Technologies in Intermediate Development (Medium TRL: 4–6)

These technologies show strong laboratory performance and limited prototype demonstrations but require further scale-up:

- Extrinsic self-healing microcapsule-based coatings: Efficient for crack healing but limited by finite healing capacity. The current TRL is 4–5, supported by promising lab-scale validation and emerging field-simulation studies [149,163].

- Vascular (microchannel) self-healing systems: Demonstrated high healing efficiency under controlled mechanical fatigue conditions; however, integration onto wind turbine surfaces remains challenging [144]. Current TRL: 4.

- Advanced hydrophobic/ice-phobic hybrid nanocoatings: These materials show potential for multi-functional protection and have undergone accelerated erosion tests [164,165]. TRL is typically 4–6, depending on the formulation.

- (c)

- Technologies at Early Laboratory or Proof-of-Concept Stages (Low TRL: 1–3)

These emerging solutions show strong scientific interest but require substantial material development and scale-up:

- Intrinsic self-healing polymers based on dynamic covalent chemistries: Systems relying on reversible Diels–Alder, imine exchange, or disulfide metathesis reactions have TRLs of 2–3. Their healing efficiency is promising, but environmental sensitivity (temperature, humidity, UV) limits field applicability [129].

- Self-healing supramolecular coatings (e.g., hydrogen-bond networks, host–guest complexes) [23]: These systems exhibit autonomous healing but reduced initial toughness, keeping them at TRL 2.

- MXene- or graphene-reinforced multifunctional self-healing composites: Still in experimental stages with limited large-sample testing [134]. TRLs remain at 1–2 until sprayed-coating feasibility and long-term environmental resistance are demonstrated.

- Bio-inspired and enzyme-activated self-healing coatings: Conceptual systems with very limited mechanical and erosion testing [166]; TRLs 1–2.

10. Conclusions

Erosion and corrosion are among the most widespread and costly challenges across various industries, leading to significant economic and environmental impacts. Self-healing coatings, through both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms, can autonomously repair surface damage, thereby improving material resilience and sustainability. Despite existing challenges, these coatings have considerable potential to extend equipment lifespan and lower maintenance costs, making them especially valuable in high-risk environments such as the petroleum industry.

This review has explored recent developments in smart self-healing coating technologies aimed at reducing LEE in WTBs. Both extrinsic and intrinsic healing systems offer promising methods to extend blade lifespan, improve operational reliability, and lower maintenance costs. Extrinsic approaches, based on encapsulated healing agents or vascular networks, provide quick localised repairs but are often limited to single-use functions. In contrast, intrinsic systems enable repeated healing through dynamic covalent or non-covalent bonds but generally show slower recovery times and lower initial mechanical strength. Hybrid strategies that combine both mechanisms could, therefore, offer an ideal balance between responsiveness and durability.

The development of next-generation self-healing polyurethane (PU) and composite coatings has demonstrated significant improvements in LEE resistance, adhesion, and hydrophobicity. Adding nanomaterials, such as graphene derivatives or silica, further enhances toughness and healing efficiency. However, major challenges persist in scaling these technologies for large-area, curved-blade surfaces and in ensuring cost-effective, environmentally sustainable manufacturing. Notably, standardised test protocols that combine assessments of erosion, fatigue, and healing under realistic operational conditions are urgently required to promote industrial adoption.

Future research should focus on developing multifunctional coatings that combine self-healing, anti-erosion, and anti-biofouling properties while minimising environmental impact. Integrating recyclable or bio-based polymers into coating systems aligns with global circular-economy goals and can help reduce microplastic emissions from eroded blades. Moreover, incorporating real-time damage detection features, such as colourimetric indicators or embedded sensors, could transform maintenance from reactive to predictive. To highlight and strengthen future research directions, a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis of self-healing coatings for Wind Turbine Blade Leading-Edge Protection is concluded as follows:

- Strengths

- Autonomous damage repair reduces maintenance frequency and extends blade service life, especially under high-velocity rain, sand, and icing conditions.

- Both intrinsic and extrinsic systems show significant advances, including dynamic covalent bonding, hydrogen bonding, microcapsules, and vascular networks, enabling effective crack closure and barrier restoration.

- Integration of nanomaterials (e.g., silica, graphene derivatives, MXenes) enhances mechanical toughness, hydrophobicity, and healing efficiency.

- Improved environmental sustainability, particularly when combined with recyclable composite substrates or bio-based polymers.

- Growing market demand for multifunctional coatings supports rapid technological development and commercial motivation.

- Weaknesses

- Lack of standardised testing protocols combining rain erosion, fatigue, and healing behaviours limits comparability across studies and slows industrial adoption.

- Extrinsic systems have finite healing capacity, as microcapsules or channels become depleted after repeated damage.

- Intrinsic systems may have slower healing rates or reduced initial toughness, especially under low temperatures or variable humidity.

- Large-scale blade application remains challenging, especially for curved, long-span surfaces that require uniform coating thickness and compatibility with field repair workflows.

- Higher manufacturing complexity and cost can hinder commercial implementation compared with conventional PU coatings.

- Opportunities

- Hybrid intrinsic–extrinsic systems offer a promising pathway to combine repeated healing with rapid responsiveness.

- Integration with digital monitoring tools, such as colourimetric damage indicators or embedded sensors, can enable predictive maintenance.

- Development of recyclable, green, or bio-based coating chemistries aligns with global circular-economy and EU sustainability goals.

- Standardised rain erosion protocols and multi-stimuli testing frameworks would accelerate certification and commercial adoption.

- Offshore wind expansion provides a growing market where self-healing coatings can significantly reduce microplastic emissions and maintenance costs.

- Threats

- Harsh offshore conditions (extreme humidity, salt, UV exposure, low temperatures) may reduce healing efficiency or accelerate degradation of some polymer systems.

- Scaling limitations may restrict transition from laboratory feasibility to full-blade application and long-term field reliability.

- Microplastic regulations may challenge polymer-based systems unless degradability or recyclability improves.

- High cost of advanced materials could slow adoption if not offset by clear maintenance savings in commercial wind farms.

- Competition from alternative technologies, such as ultrahard overlays, erosion-resistant tapes, or aerodynamic redesigns, may reduce the relative advantage of self-healing systems.

In summary, self-healing coatings represent a transformative pathway toward more durable, sustainable, and intelligent protection systems for WTBs. Advancing these materials from laboratory demonstrations to field-deployable technologies will require interdisciplinary collaboration across materials science, aerodynamics, and manufacturing engineering. Achieving this transition will be pivotal to ensuring the long-term sustainability and efficiency of the global wind energy sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.A.; methodology, M.A. and L.M.J.; validation, M.A., L.M.J., E.F.T. and D.M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A., L.M.J., E.F.T. and D.M.D.; visualisation, M.A. and L.M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by the GreenCompos research project supported by the Research Ireland Industry RD&I Fellowship Programme grant Number 23/IRDIFB/12098.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author would like to express gratitude to the co-authors, Leon Mishnaevsky Jr., E.F. Tobin, and Declan M. Devine, for their valuable discussions and collaborative contributions throughout this work. The corresponding author would like to acknowledge Technological University of the Shannon (TUS), Applied Polymer Technology Gateway, and PRISM (Polymers, Recycling, Industrial, Sustainability and Manufacturing) Research Institute for their support. The authors used ChatGPT-4o for language refinement in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Mohamad Alsaadi was employed by the company ÉireComposites Teo. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Mishnaevsky, L.; Thomsen, K. Costs of Repair of Wind Turbine Blades: Influence of Technology Aspects. Wind Energy 2020, 23, 2247–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishnaevsky, L.; Hasager, C.B.; Bak, C.; Tilg, A.-M.; Bech, J.I.; Doagou Rad, S.; Fæster, S. Leading Edge Erosion of Wind Turbine Blades: Understanding, Prevention and Protection. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, G.; O’Donoghue, A.; O’Connor, F.; Monaghan, C. A Novel Solution for Preventing Leading Edge Erosion in Wind Turbine Blades. In Which Is Termed LEP. SWORD–South West Open Research Deposit; Munster Technological University: Cork, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan, M.H.; Nash, D.H.; Stack, M.M. On Erosion Issues Associated with the Leading Edge of Wind Turbine Blades. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 383001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.M.; Rehfeld, N.; Schreiner, C.; Dyer, K. The Development of a Novel Thin Film Test Method to Evaluate the Rain Erosion Resistance of Polyaspartate-Based Leading Edge Protection Coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.S.; Castro, S.G.P.; Jiang, Z.; Teuwen, J.J.E. Numerical Investigation of Rain Droplet Impact on Offshore Wind Turbine Blades under Different Rainfall Conditions: A Parametric Study. Compos. Struct. 2020, 241, 112096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, Q.L.; Ansari, Q.M.; Sánchez, F.; Mishnaevsky, L.; Young, T.M. Stress Development in Droplet Impact Analysis of Rain Erosion Damage on Wind Turbine Blades: A Review of Liquid-to-Solid Contact Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakseresht, A.; Amirtharaj Mosas, K.K. (Eds.) Coatings for High-Temperature Environments: Anti-Corrosion and Anti-Wear Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alarifi, I.M. A Comprehensive Review on Advancements of Elastomers for Engineering Applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2023, 6, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Guo, E.; Chen, X.-B.; Kang, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, T. Recent Progress in Protective Coatings against Corrosion upon Magnesium–Lithium Alloys: A Critical Review. J. Magnes. Alloy 2024, 12, 3967–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, A.; Firoozi, A.; Oyejobi, D.O.; Avudaiappan, S.; Flores, E. Enhanced Durability and Environmental Sustainability in Marine Infrastructure: Innovations in Anti-Corrosive Coating Technologies. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA Wind Task 46. Leading Edge Erosion Classification System; Technical Report; International Energy Agency (IEA) Wind Technology Collaboration Programme: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Herring, R.; Dyer, K.; Martin, F.; Ward, C. The Increasing Importance of Leading Edge Erosion and a Review of Existing Protection Solutions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 115, 109382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MİRA. WTG Operations—İzmir. Mira Rope Access. Available online: https://www.mira-ra.com/wtg-operations_17_en.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- JEC Group. Rope Robotics’ Wind Turbine Blade Repairs Pay Off in Six Months. JEC Composites. Available online: https://www.jeccomposites.com/news/spotted-by-jec/rope-robotics-wind-turbine-blade-repairs-pay-off-in-six-months/ (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Aerones. Leading Edge Repair. Available online: https://aerones.com/Services/Leading-Edge-Repair/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- LiDAR Solutions. Wind Turbine Blade Inspection with Drone; LiDAR Solutions: Croydon, VIC, Australia. Available online: https://www.Lidarsolutions.com.Au/Drone-Inspection-Services-for-Wind-Solar-Oil-and-Gas-Assets/Wind-Turbine-Blade-Inspection-with-Drone/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Heo, S.-J.; Na, W.S. Review of Drone-Based Technologies for Wind Turbine Blade Inspection. Electronics 2025, 14, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Deng, J.; Higazy, S.A.; Selim, M.S.; Jin, H.; Kessler, M.R. Self-Healing Anti-Corrosion Coatings: Challenges and Opportunities from Laboratory Breakthroughs to Industrial Realization. Coatings 2025, 15, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartsonakis, I.A.; Kontiza, A.; Kanellopoulou, I.A. Advanced Micro/Nanocapsules for Self-Healing Coatings. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterova, T.; Dam-Johansen, K.; Pedersen, L.T.; Kiil, S. Microcapsule-Based Self-Healing Anticorrosive Coatings: Capsule Size, Coating Formulation, and Exposure Testing. Prog. Org. Coat. 2012, 75, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zeng, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Y.; Xiong, R.; Huang, C. Self-Healing Polymers through Hydrogen-Bond Cross-Linking: Synthesis and Electronic Applications. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 4000–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; Shi, L.; Yu, W.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Mao, H.; Zhang, D.; Lu, T.; et al. Phase-Locked Constructing Dynamic Supramolecular Ionic Conductive Elastomers with Superior Toughness, Autonomous Self-Healing and Recyclability. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Zhu, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, B.; Jia, D. Recyclable and Self-Healing Rubber Composites Based on Thermorevesible Dynamic Covalent Bonding. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 129, 105709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Urban, M.W. Self-Healing Polymeric Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmer, A.; Brinkmann, A.; Stenzel, V.; Hartwig, A.; Koschek, K. Moisture-mediated Intrinsic Self-healing of Modified Polyurethane Urea Polymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2018, 56, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Shen, T.; Yang, J.; Cao, W.; Wei, J.; Li, W. Room-Temperature Intrinsic Self-Healing Materials: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishnaevsky, L.; Tempelis, A.; Kuthe, N.; Mahajan, P. Recent Developments in the Protection of Wind Turbine Blades against Leading Edge Erosion: Materials Solutions and Predictive Modelling. Renew. Energy 2023, 215, 118966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjana, V.S.; Ponnan, S.; Mukundan, A.; Prabu, A.A.; Wang, H.-C. Emerging Trends in Silane-Modified Nanomaterial–Polymer Nanocomposites for Energy Harvesting Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Choufi, N.; Mustapha, S.; Tehrani, B.A.; Grady, B.P. An Overview of Self-Healable Polymers and Recent Advances in the Field. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43, e2200164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryor, S.C.; Barthelmie, R.J.; Coburn, J.J.; Zhou, X.; Rodgers, M.; Norton, H.; Campobasso, M.S.; López, B.M.; Hasager, C.B.; Mishnaevsky, L. Prioritizing Research for Enhancing the Technology Readiness Level of Wind Turbine Blade Leading-Edge Erosion Solutions. Energies 2024, 17, 6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, G.; Middleton, A.C.; Stack, M.M. Mapping Raindrop Erosion of GFRP Composite Wind Turbine Blade Materials: Perspectives on Degradation Effects in Offshore and Acid Rain Environmental Conditions. J. Tribol. 2020, 142, 061701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerffer, P.; Doerffer, K.; Ochrymiuk, T.; Telega, J. Variable Size Twin-Rotor Wind Turbine. Energies 2019, 12, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Jin, Y. Turbines in Built-Up Areas: Prospects and Challenges. Wind 2023, 3, 418–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, B.; Kelly, G.; Cashman, A. Aerodynamic Design and Performance Parameters of a Lift-Type Vertical Axis Wind Turbine: A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 110699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, B.; Chowdhury, H.; Mustary, I.; Rana, M.M.; Alam, F. Design of a Micro Wind Turbine and Its Economic Feasibility Study for Residential Power Generation in Built-up Areas. Energy Procedia 2019, 160, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action Victoria. What Is Offshore Wind Energy? 24 March 2025. Available online: https://www.energy.vic.gov.au/renewable-energy/offshore-wind-energy/what-is-offshore-wind-energy/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Lachenal, X.; Daynes, S.; Weaver, P.M. Review of Morphing Concepts and Materials for Wind Turbine Blade Applications. Wind Energy 2013, 16, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morini, A.A.; Ribeiro, M.J.; Hotza, D. Carbon Footprint and Embodied Energy of a Wind Turbine Blade—A Case Study. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1177–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.P.; Skelton, K. Wind Turbine Blade Recycling: Experiences, Challenges and Possibilities in a Circular Economy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 97, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]