1. Introduction

The shipping industry, serving as the lifeblood of the global economic system, undertakes over 90% of global trade volume, with vessels constituting the core carriers within this vast transportation network [

1]. The burgeoning development of artificial intelligence has propelled deep learning-based intelligent ship surveillance technology to achieve qualitative breakthroughs in maritime monitoring, owing to its exceptional data-fitting capabilities. Consequently, it has been widely adopted in vessel surveillance [

2], significantly enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of ship management tasks. However, distinct from conventional surveillance tasks, maritime surveillance serves critical functions in civilian contexts [

3]—such as ocean resource regulation, illegal fishing identification, and maritime search and rescue coordination—while at the military application level [

4], it provides vital support for territorial waters patrol, maritime rights protection, and strategic port facility monitoring. The stable operation of maritime surveillance systems forms a crucial line of defense for safeguarding shipping safety and maintaining the orderly functioning of global supply chains. Its reliability directly impacts trillions of dollars in maritime trade, the safety of millions of crew members, and the sustainability of marine ecosystems.

Therefore, ship surveillance based on deep learning technology is an indispensable component of next-generation maritime strategic planning, with its core requirement being to ensure high-level safety and stability across diverse environments. For instance, incidents of vessel signal spoofing and jamming in the Red Sea region increased significantly in 2025 [

5]. Such adversarial interference not only substantially escalates navigational complexity but also directly undermines vessels’ ability to transmit emergency distress signals. In today’s increasingly adversarial maritime environment, the robustness of automated ship surveillance models faces severe challenges.

Although existing deep learning ship surveillance models excel in vessel detection across numerous scenarios, the inherent black-box nature of deep learning models renders their intermediate features non-interpretable. This results in weak adversarial attack and defense capabilities, leaving subtle vulnerabilities that can be readily exploited. Such vulnerabilities provide opportunities for malicious actors to evade surveillance through opportunistic means. For example, in the field of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) ship detection, studies reveal that adversaries can exploit gradient information of deep learning models to generate visually imperceptible adversarial perturbations, which are superimposed on original SAR images [

6]. These meticulously crafted disturbances can successfully “deceive” advanced detection models. Furthermore, in optical surveillance tasks under visible-light scenarios, malicious actors can distort vessels’ imaging characteristics in sensors through camouflage [

7], causing deep learning models to misidentify them as floating debris or background noise. Such flaws lead to critical failures, including missed detections of illegal vessels disguised as merchant ships or false alarms in harmless areas. This not only creates covert channels for smuggling, illegal fishing, and unauthorized approaches to sensitive waters but may also trigger collision risks in critical zones like busy shipping lanes or coastal areas. Moreover, it can disrupt the normal operation of maritime management and safety systems, directly threatening lives, property, and regional maritime order. Despite significant progress in precision enhancement, the stability and reliability of existing models remain inadequately validated in mission-critical scenarios—such as maritime law enforcement encounters involving electronic jamming or signal spoofing—where robustness is most essential. This gap in robustness research may propagate maritime safety risk chains in practical operations.

In summary, singular improvements in accuracy do not equate to a secure and reliable surveillance model; instead, they highlight substantial room for robustness enhancement. In environments plagued by adversarial attacks, decision boundary rectification and defense capability fortification emerge as pivotal challenges, further underscoring the imperative to enhance the safety and stability of ship surveillance models in complex marine environments.

The critical flaw in current automated vessel surveillance models lies in their extreme vulnerability to adversarial perturbations, directly causing reliability collapse under malicious attacks. Specifically, on one hand, attacks involving occlusion or tampering of sample data severely corrupt the foundational information models rely on for learning, triggering instability issues such as prediction inaccuracies and behavioral logic confusion, ultimately leading to surveillance failure, one the other hand carefully crafted adversarial inputs can effectively deceive models, causing severe detection evasion problems—manifested as failures to correctly identify or track target vessels—resulting in sharp declines in prediction accuracy, drastic trajectory deviations, and significantly escalated control risks. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop an innovative training strategy-based vessel type detection model to fundamentally counteract these two types of adversarial interference. By revolutionizing the training paradigm, the model’s robustness can be substantially elevated, ensuring high-precision and highly reliable surveillance capabilities across diverse complex scenarios, including data corruption and adversarial inputs.

To address the aforementioned challenges regarding the unreliable deployment of current maritime surveillance models, this study proposes a novel vessel surveillance framework based on adversarial training strategies. Its core innovation lies in proactively introducing and learning to counteract simulated adversarial interference data—namely adversarial examples—during model training, thereby significantly enhancing model stability (robustness) in complex jamming environments. Specifically, we simulate various subtle, imperceptible data perturbations that attackers might generate and incorporate these disruptive data alongside normal data for model training. This compels the model not only to recognize standard vessel features but also to learn to ignore or resist such interference. Analogous to stress testing, this approach forces the model to adapt to harsher conditions, ensuring stable recognition performance when encountering similar disruptions in real-world scenarios, thereby reducing misjudgments. Such enhanced stability is paramount for guaranteeing the reliability of maritime regulatory tasks.

Experimental validation on standard vessel image datasets and adversarial interference datasets demonstrates that the RAFS-Net framework achieves high efficiency through its dual-module synergistic mechanism. Its adversarial generation module successfully synthesizes multimodal perturbation samples that disrupt benchmark models, significantly increasing their false detection rates. Concurrently, the adversarial training module designed in this study effectively maintains surveillance stability against heavily perturbed samples. Additionally, a series of supplementary experiments were conducted to evaluate the efficacy of the strategies employed in RAFS-Net.

In summary, the primary contributions of this study are as follows:

This study introduces an innovative robust adversarial fusion training framework, whose core lies in systematically integrating adversarial training strategies. By iteratively generating and injecting gradient-based adversarial perturbation samples during training, these perturbed samples synergistically optimize model parameters with original training data. This forces the model to learn more discriminative and robust feature representations under optimization objectives, effectively enhancing its generalization capability and stability in marine monitoring environments plagued by complex adversarial interference such as digital perturbations and physical camouflage. Compared to baseline models, the framework achieves significant improvements in key metrics: the mean Average Precision (mAP) increases by an average of 9.103%, while the Area Under the Curve (AUC) also exhibit synchronous enhancements. This substantially strengthens the system’s overall performance and reliability in adversarial scenarios.

This study constructes and provides a novel adversarial benchmark dataset specifically designed for evaluating the robustness of ship surveillance models. The dataset encompasses images from five typical vessel categories. Its core innovation involves applying multiple adversarial attack algorithms with controllable intensity levels to generate corresponding adversarial samples for off-target ship images within the dataset. Compared to existing general ship detection datasets, this offers a standardized adversarial evaluation environment capable of precisely quantifying models’ robustness degradation under attack. It thereby establishes a rigorous benchmark for assessing model generalization performance in adversarial interference environments.

This study proposes and elaborates on an adversarial sample generation and training integration method tailored for the Robust Adversarial Fusion Surveillance Network (RAFS-Net). This method not only defines the complete adversarial sample generation workflow within the RAFS-Net framework (including critical hyperparameters such as attack algorithm selection) but, more importantly, seamlessly integrates it into the model’s end-to-end training loop. Through extensive experiments on ship datasets of varying scales and characteristics, the method provides key empirical insights into hyperparameter configurations for generating effective adversarial samples to enhance model robustness. It addresses core parameter setting challenges in adversarial training, such as perturbation magnitude control and balancing attack strength with computational efficiency, ensuring the method’s reproducibility and generalizability.

The remaining content will be presented in the following sections: First,

Section 2 elucidates the research status of traditional vessel monitoring methods and deep learning-based visible-light ship monitoring models. Second,

Section 3 provides a detailed description of the proposed framework, RAFS-Net, encompassing the problem formulation, adversarial attack generation phase, and adversarial training phase. Subsequently,

Section 4 meticulously discusses the experimental setup and analysis of results. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the principal contributions of this study and introduces supplementary research on maritime management to be pursued subsequently.

3. Robust Adversarial Fusion Framework for Maritime Surveillance

The adversarial training fusion network framework proposed in this study, termed RAFS-Net (as illustrated in

Figure 1), comprises two critical phases: the Adversarial Attack Generation Phase and the Adversarial Training Phase. During the first phase (Adversarial Attack Generation), the target dataset is fed into the framework. Adversarial attack algorithms—such as the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) [

34] and Projected Gradient Descent (PGD)—are employed to apply meticulously crafted [

35], visually imperceptible perturbations to original images. These perturbations, though subtle, effectively disrupt the model’s decision-making process by aligning with the gradient direction of the model’s loss function.

Subsequently, the second phase (Adversarial Training) commences. Initially, the network model is trained on unperturbed original images to learn fundamental feature representations of the task data. At this stage, different backbone networks can be substituted within the framework based on task requirements. Next, adversarially perturbed samples generated in Phase 1 (

Section 3.2) are incorporated into the training dataset and mixed with original images for model training. The network updates its parameters by minimizing a composite loss function that includes both classification loss for original images and classification loss for adversarial samples. This approach continuously exposes the model to adversarial examples during training, thereby compelling it to learn more generalized and robust feature representations while rectifying its classification decision boundaries.

Through this training strategy, models developed under the RAFS-Net framework maintain high classification performance not only on benign samples but also when confronting maliciously crafted adversarial samples, significantly enhancing practical stability and reliability. The subsequent sections comprehensively elaborate on the RAFS-Net framework, including problem formulation, adversarial attack generation, and adversarial training phases.

3.1. Problem Statement

In this study, we formulate the task as a classification problem under supervised learning, aiming to identify vessel types within images. The network framework is designed to classify ship outboard images captured via optical surveillance cameras in nearshore environments, predicting the vessel category contained in an input image. For the input dataset , represents the profile images of the k-th vessel from varying viewing angles, with label denoting the vessel category. Here, N indicates the total number of ship outboard images in the dataset. The objective is to enable the model to output predicted vessel categories, formalized as the mapping function: .

3.2. Adversarial Attack Generation Stage

This phase commences by applying adversarial perturbation generation preprocessing algorithms to perform essential data augmentation on the Deep Learning Ship Dataset . The process initiates with resizing each image to 224 × 224 pixels via a resize function, converting it into tensor format, and normalizing pixel values using a data normalization function that sets the mean and standard deviation of red, green, and blue channels to 0.5. Subsequently, for each sample in the dataset, its adversarial counterpart is initialized as a copy of the original image .

Over T iterations, the algorithm iteratively generates perturbations for each adversarial sample through a perturbation calculation function. This function computes the gradient of the loss function with respect to the input and adjusts sample generation accordingly. After each perturbation step, the adversarial sample undergoes perturbation range trimming via a clipping function, constraining introduced perturbations within specified -bounds. This prevents excessive deviation from original images and ensures visual imperceptibility of perturbations.

Upon completing iterations, the final outputs are aggregated into an Adversarial Attack Training Dataset , containing adversarial samples paired with corresponding originals . This dataset is subsequently utilized in the next phase for neural network training, significantly enhancing robustness against potential adversarial interference—a critical requirement for maintaining model reliability in computer vision tasks such as ship detection. The detailed implementation of this phase is presented in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Adversarial Perturbation Generation for Training Dataset. |

| Require: |

Deep learning vessel dataset Learning rate Perturbation range Number of iterations T Number of perturbation steps K Neural network parameters

|

| Require: |

▷ Adversarial perturbation calculator ▷ Image resizing function (224 × 224) ▷ Data tensor conversion ▷ Per-channel normalization () ▷ Perturbation clipping

|

| Ensure: |

All images standardized to 224 × 224 resolution Tensor format conversion completed RGB channels normalized per specification Perturbations constrained within -ball Valid adversarial training pairs generated

|

- 1:

▷ Resize to - 2:

▷ Convert to tensor - 3:

▷ Apply per channel - 4:

▷ Initialize adversarial dataset - 5:

for iter to T do ▷ Outer training iterations - 6:

for each do ▷ Process each sample - 7:

▷ Initialize adversarial sample - 8:

for to K do ▷ Perturbation steps - 9:

- 10:

▷ Apply perturbation - 11:

- 12:

end for - 13:

▷ Store clean-adversarial pair - 14:

end for - 15:

end for - 16:

return ▷ Adversarial training dataset

|

3.3. Adversarial Training Stage

To ensure effective monitoring of nearshore vessels in adversarial environments, we feed the Adversarial Attack Training Dataset obtained in the first stage into our network architecture for feature extraction and representation learning. We employ ResNet-34 as the backbone network in our implementation while maintaining flexibility to substitute other network models for ship image feature extraction. The information contained in ship images is processed through convolutional layers to obtain higher-dimensional representations. As the core component of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), convolutional layers extract features from both original and adversarially perturbed images by kernel scanning. The operation of convolutional layers is formalized in Equation (

1):

where

s denotes extracted features,

x represents input images to the convolutional layer,

w signifies kernel weights,

denotes index feature dimensions, and

denotes index kernel dimensions. Within maritime surveillance systems, adversarial attacks simulate malicious interference such as electronic spoofing and signal camouflage to evaluate model robustness. First, the FGSM (Fast Gradient Sign Method) [

34] employs single-step bounded perturbations with high computational efficiency but limited attack strength, suitable for simulating transient signal interference. Second, FGM (Fast Gradient Method) [

36] introduces L2-norm constraints to generate directionally precise perturbations, effectively simulating radar scattering interference, though vulnerable to gradient saturation. The core distinction lies in their norm constraints and gradient utilization strategies, both belonging to single-step attacks.

Third, the advanced PGD (Projected Gradient Descent) [

35] method utilizes multi-step iterations with random initialization, generating the strongest adaptive attacks for maritime monitoring that accurately simulate persistent vessel trajectory spoofing. While computationally costlier than FGSM/FGM, it achieves higher attack success rates. Finally, the complementary FreeLB (Free Large-Batch Training) [

37] adopts a stochastic perturbation ensemble strategy by accumulating gradients multiple times within a single batch to maximize perturbation loss, functioning inherently as a defensive training strategy. We implement these four perturbation methods as formalized in Equations (

2)–(

5):

where

x denotes the original ship image,

represents the perturbed input image,

controls perturbation intensity, and

L is the cross-entropy loss. FGM applies L2-norm constrained perturbations along the gradient direction, while FGSM utilizes the gradient sign function

to impose L

-bounded perturbations ensuring imperceptibility. In PGD,

defines the

-radius perturbation ball and

denotes the projection operator, implementing multi-step iterative attacks projected to feasible regions. FreeLB generates uniformly distributed random perturbation vectors

within

.

The adversarial training mechanics are formalized as Equations (

6)–(

8):

Equation (

6) computes the adversarial loss

by measuring the discrepancy between predicted labels

and ground truth

y. Equation (

7) calculates the gradient

of this loss with respect to network parameters. Finally, Equation (

8) updates network parameters by subtracting the product of learning rate

and gradient

from current parameters

. The framework outputs trained parameters

and predicted vessel detection labels

. Detailed procedures for feature extraction, gradient computation, and adversarial loss calculation during the adversarial training phase are specified in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Adversarial Training with Fixed Attack Methocfor Ship Detection. |

| Require: |

Clean training dataset: Chosen attack method:

Attack hyperparameters: , , T Learning rate Initial network parameters

|

| Ensure: |

|

- 1:

function ShipResNetClassifier() - 2:

▷ Initial convolution - 3:

▷ Down-sampling - 4:

▷ Residual blocks per stage - 5:

for to 4 do - 6:

for to do - 7:

▷ Basic residual block - 8:

end for - 9:

end for - 10:

▷ Feature vector - 11:

▷ Ship detection logits - 12:

return - 13:

end function - 14:

for epoch to E do ▷ Training loop over epochs - 15:

for in do ▷ Mini-batch loop - 16:

Generate adversarial examples: - 17:

if attack = FGM then ▷ Fast Gradient Method - 18:

- 19:

▷ L2-norm perturbation - 20:

else if attack = FGSM then ▷ Fast Gradient Sign Method - 21:

- 22:

▷ perturbation - 23:

else if attack = PGD then ▷ Projected Gradient Descent - 24:

▷ Random initialization - 25:

for to do - 26:

- 27:

- 28:

end for - 29:

- 30:

else ▷ Free Large-Batch Training (FreeLB) - 31:

for to T do - 32:

▷ Random perturbation - 33:

- 34:

- 35:

end for - 36:

- 37:

▷ Compute gradient - 38:

end if - 39:

if attack ≠ FreeLB then - 40:

Forward pass: ▷ Network forward propagation - 41:

- 42:

▷ Compute gradient - 43:

end if - 44:

Update parameters: - 45:

end for - 46:

end for - 47:

return , ▷ Trained network parameters , and ship detection labels

|

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Datasets

In this study, three primary datasets were utilized for training and evaluating deep learning models to address ship image classification tasks. Firstly, the Deep Learning Ship Dataset was employed (

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/arpitjain007/game-of-deep-learning-ship-datasets,

Figure 2) (accessed on 15 February 2025), providing extensive ship imagery covering five major vessel types: Cargo, Carriers, Cruise ships, Military, and Tankers. As illustrated, these images exhibit diverse visual characteristics across various environments and viewing angles. Statistical analysis reveals balanced category distribution with approximately equal image counts: 1334 for Cargo, 1327 for Carrier, 1331 for Cruise, 1328 for Military, and 1329 for Tankers, shown on

Table 1. Such diversity establishes a solid foundation for training robust classification models.

Subsequently, the Original Validation Dataset was used for model evaluation, as shown in

Figure 3. This dataset similarly contains images of all five ship categories but with smaller sample sizes—147 to 148 images per category, shown on

Table 2. This configuration makes it ideal for assessing model generalization capabilities on limited data. Though smaller in scale than the training dataset, its high image quality and balanced category distribution render it invaluable for performance benchmarking.

Finally, the Ship Outboard Adversarial Attack Dataset was introduced to test model robustness against adversarial attacks, as shown in

Figure 4. This dataset incorporates adversarially perturbed ship images, maintaining coverage of all five vessel types with 147 images per category, shown on

Table 3. These images demonstrate how adversarial manipulations alter visual characteristics, challenging model recognition capabilities. Testing on this dataset enables rigorous assessment of model stability and reliability when confronting potential adversarial attacks in real-world scenarios, ensuring effective operation under complex conditions.

4.2. Evaluation Indicators

The maritime vessel recognition capability of RAFS-Net was quantitatively assessed employing four principal metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Within the confusion matrix framework, the following equation was used:

Positive samples that are correctly predicted to be positive are represented by TP, while negative samples that are correctly predicted to be negative are represented by TN. FP and FN, respectively, represent the negative and positive samples of incorrect predictions.

4.3. Experiment Environment and Parameters Setting

In this study, a non-pretrained ResNet-34 [

38] model was employed as the backbone of the RAFS-Net surveillance framework. The entire model was optimized using the cross-entropy loss function. Based on experimental findings, we configured the batch size to 32 and set the learning rate at 0.001, utilizing Adam as the optimization algorithm. All experiments were conducted on a workstation featuring a 64-bit Windows 11 operating system, 12th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-12700 processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), 32 GB RAM, and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The PyTorch 1.7 deep learning framework was implemented with PyCharm (PyCharm 2025.1, JetBrains s.r.o., Prague, Czech Republic) as the primary integrated development environment and Python 3.9 as the programming language.

4.4. Results of Experiments

On the pristine validation dataset (without adversarial attacks), models without adversarial training generally exhibited high performance across metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, according to reference Formula (

9). This indicates that while adversarial training enhances robustness against adversarial attacks, it may incur performance degradation in benign scenarios. However, when evaluated on the adversarial test set, non-adversarially-trained models suffered significant performance deterioration, whereas adversarially-trained models maintained superior performance levels. This validates the substantial efficacy of adversarial training in fortifying model resilience against attacks.

As detailed in

Table 4, comprehensive performance metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score) of multiple neural network models are presented for both pristine and adversarial datasets. Overall, ResNet [

38] and DenseNet series demonstrated exceptional performance on pristine data—ResNet-50 [

38] achieved 94.158% accuracy and 94.099 F1-score. Under adversarial attacks, all models experienced performance declines with varying severity: VGG-series models (e.g., VGG-11, VGG-13) performed poorly on both datasets, with significantly lower accuracy and F1-scores than counterparts, suggesting inherent limitations even before attacks. The fundamental reason for VGG’s failure in adversarial training lies in its architectural design, which is ill-suited for tasks requiring stable gradient flow and high model robustness. Specifically, VGG is a “plain” network stacked with consecutive convolutional layers, lacking modern designs like residual connections. This defect causes two critical issues: first, during backpropagation essential for adversarial training, gradient signals in VGG’s deep layers become unstable or vanish, preventing effective weight updates based on adversarial loss and hindering both the generation of high-quality adversarial samples and learning from them; second, the impeded gradient flow obstructs the propagation of high-level semantic objectives (e.g., “resisting perturbations”) to underlying feature extractors, leading to a failure in learning robust features that remain stable under perturbations and instead promoting overfitting to non-robust superficial features of the training data. In contrast, modern architectures like ResNet and DenseNet, which performed excellently in our experiments, address these gradient issues through residual or dense connections, ensuring stable and efficient training. This enables them to successfully refine decision boundaries and learn more generalizable robust feature representations, thereby maintaining superior performance in adversarial environments.

Although ResNet [

38] and DenseNet [

39] models showed reduced performance under attacks, they retained relatively high levels—ResNet-50 [

38] declined to a 73.505% accuracy and a 72.602 F1-score. Notably, DenseNet-169 [

39] and DenseNet-121 [

39] exhibited superior robustness with F1-scores of 71.051 and 81.796 respectively, indicating smaller performance drops compared to pristine conditions. MobileNetV3-Large [

40] and MobileNetV3-Small [

40] also demonstrated competitive robustness under attacks (73.958 and 64.205 F1-scores). These results confirm that the adversarial training framework is broadly applicable to most deep learning models, effectively enhancing adversarial robustness while maintaining high versatility.

In summary, while adversarial training may incur performance degradation in benign environments—necessitating careful consideration for practical maritime surveillance applications—it nevertheless demonstrates efficacy in enhancing model robustness. Crucially, it sustains high-level monitoring performance when confronted with malicious adversarial attacks, such as scenarios where adversaries deliberately camouflage vessels using adversarial perturbations.

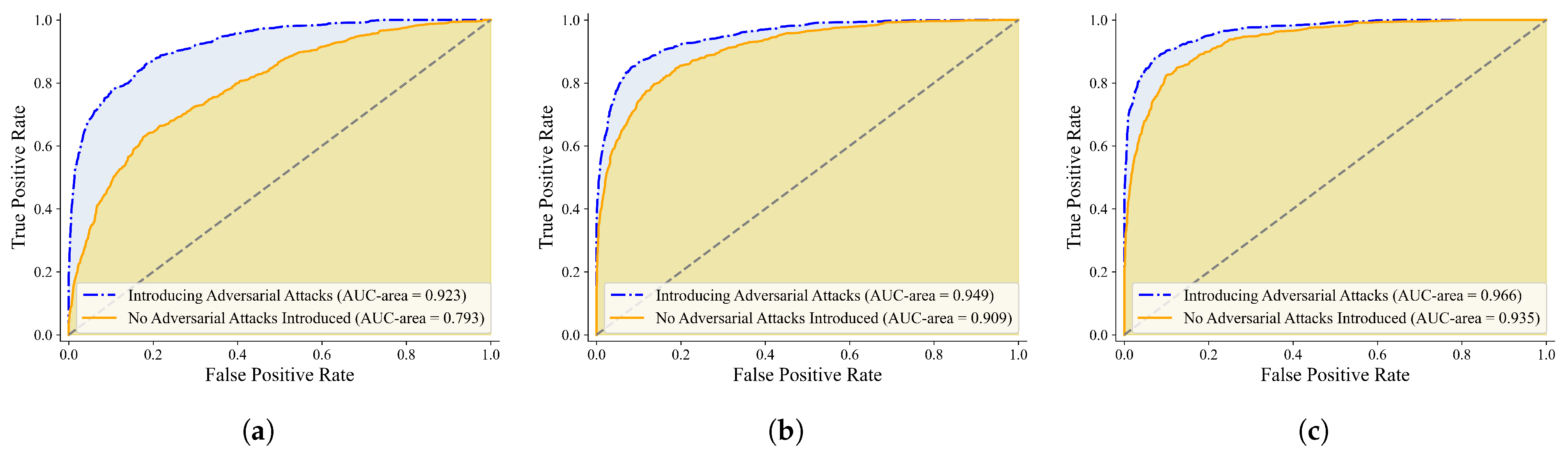

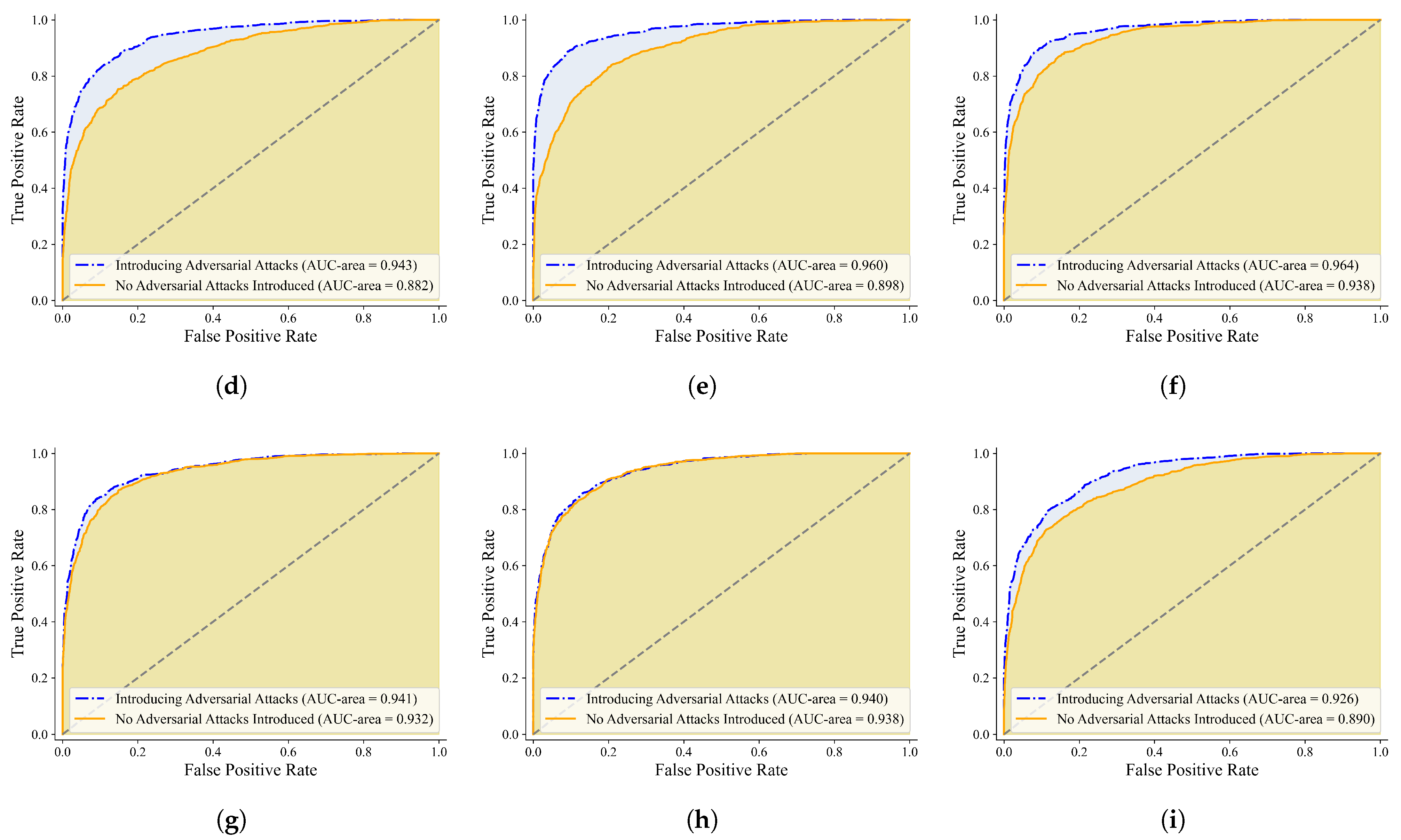

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the mean Average Precision (mAP) and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves of various neural network models, including AlexNet [

41], ResNet [

38], DenseNet [

39], and MobileNetV3, under both adversarial attack and attack-free conditions. Comparative analysis of these curves reveals that introducing adversarial attacks typically reduces mAP and Area Under the Curve (AUC) values, indicating performance degradation. However, significant disparities exist among models: certain architectures (e.g., ResNet-34 [

38] and DenseNet-121 [

39]) maintain relatively high curve coverage areas post-attack, demonstrating superior robustness. Conversely, others (e.g., VGG-series [

42] models) exhibit sharp performance deterioration under attacks.

Table 4.

A horizontal performance comparison of each model on the Original Validation Dataset and the Ship Outboard Adversary Attack Dataset.

Table 4.

A horizontal performance comparison of each model on the Original Validation Dataset and the Ship Outboard Adversary Attack Dataset.

| Dataset | Original Validation Dataset | Adversarial-Test Dataset |

|---|

|

Models

|

Accuracy

|

Precision

|

Recall

|

F1-Score

|

Accuracy

|

Precision

|

Recall

|

F1-Score

|

|---|

| AlexNet [41] | 63.043 | 63.358 | 63.069 | 62.397 | 50.679 | 53.705 | 50.724 | 47.948 |

| 87.092 | 87.013 | 87.113 | 87.029 | 71.739 | 73.541 | 71.767 | 70.915 |

| VGG-11 [42] | 21.541 | 4.290 | 20.000 | 7.065 | 21.541 | 4.290 | 20.000 | 7.065 |

| 21.541 | 4.290 | 20.000 | 7.065 | 21.541 | 4.290 | 20.000 | 7.065 |

| VGG-13 [42] | 21.541 | 4.290 | 20.000 | 7.065 | 21.541 | 4.290 | 20.000 | 7.065 |

| 21.541 | 4.290 | 20.000 | 7.065 | 21.541 | 4.290 | 20.000 | 7.065 |

| ResNet-18 [38] | 92.120 | 92.716 | 92.120 | 92.183 | 69.973 | 70.522 | 69.992 | 69.576 |

| 92.120 | 92.100 | 92.138 | 92.042 | 77.853 | 78.468 | 77.869 | 77.885 |

| ResNet-34 [38] | 90.353 | 90.458 | 90.369 | 90.364 | 71.603 | 73.758 | 71.621 | 71.075 |

| 94.565 | 94.671 | 94.573 | 94.609 | 82.201 | 82.836 | 82.204 | 82.004 |

| ResNet-50 [38] | 86.141 | 87.061 | 86.173 | 86.012 | 65.082 | 68.996 | 65.088 | 63.975 |

| 94.158 | 94.093 | 94.168 | 94.099 | 73.505 | 75.939 | 73.549 | 72.602 |

| ResNet-101 [38] | 85.598 | 88.406 | 85.638 | 85.448 | 62.908 | 64.454 | 62.960 | 61.581 |

| 92.527 | 93.090 | 92.540 | 92.643 | 80.571 | 81.983 | 80.603 | 80.354 |

| DenseNet-121 [39] | 92.120 | 92.108 | 92.136 | 92.076 | 72.690 | 74.464 | 72.747 | 70.798 |

| 93.071 | 93.585 | 93.071 | 93.210 | 81.658 | 82.348 | 81.660 | 81.796 |

| DenseNet-169 [39] | 91.984 | 92.229 | 91.999 | 91.986 | 71.332 | 72.936 | 71.355 | 71.051 |

| 93.886 | 93.943 | 93.893 | 93.912 | 72.826 | 77.142 | 72.849 | 73.097 |

| MobileNetV3-Large [40] | 92.255 | 92.509 | 92.259 | 92.327 | 74.049 | 74.459 | 74.075 | 73.958 |

| 86.413 | 87.926 | 86.408 | 86.425 | 74.864 | 75.501 | 74.869 | 74.629 |

| MobileNetV3-Small [40] | 88.859 | 88.937 | 88.865 | 88.770 | 64.266 | 66.208 | 64.289 | 64.205 |

| 87.636 | 88.708 | 87.635 | 87.800 | 69.293 | 70.695 | 69.348 | 67.336 |

Additionally, these visualizations show minimal performance variation among models in attack-free scenarios, highlighting the substantial impact of adversarial attacks on model behavior. Collectively, the figures emphasize performance shifts under adversarial conditions, providing critical references for selecting and optimizing deep learning models in surveillance applications.

4.5. Analysis of the Impact of Different Counter-Attack Methods Experiment

On the test set with applied adversarial perturbations, models lacking adversarial training exhibited suboptimal performance across metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, demonstrating significantly heightened vulnerability to such attacks, as illustrated in

Figure 9. The impact of various attack methods (LinfPGD, FGM, FGSM, FreeLB, and no attack) on multiple neural network models (including AlexNet, ResNet, VGG, DenseNet, MobileNetV3, etc.) was summarized. Overall, VGG-series models displayed inferior performance under attacks, with significant declines in accuracy and precision metrics. Conversely, deeper architectures like ResNet and DenseNet exhibited higher robustness, maintaining relatively strong performance even under FreeLB attacks. Notably, AlexNet—an earlier model—showed adaptability in specific attack scenarios: its accuracy rose from 63.966% under no attack to 83.696% under LinfPGD attacks. These results indicate that model architectural complexity critically influences adversarial resistance, with substantial performance variations across attack scenarios. This underscores the necessity of selecting appropriate model architectures based on application-specific requirements and implementing targeted defense measures to enhance robustness.

In contrast, models trained with adversarial techniques demonstrated stronger adaptability to adversarial perturbations, exhibiting smaller performance degradation. Crucially, different adversarial training methods varied in their effectiveness. Notably, robust adversarial training strategies—exemplified by FreeLB-Attack—proved more effective in enhancing model robustness, thereby ensuring stability against adversarial assaults. When selecting adversarial training methods, performance in both non-adversarial and adversarial environments must be jointly considered. Thus, the chosen method should not only improve performance on pristine data but also effectively fortify the model’s resistance to adversarial intrusions.

4.6. Analysis of the Impact of Different Counter-Attack Parameters Experiment

This comprehensive study delineates the critical role of adversarial hyperparameters in ship surveillance systems through three targeted experiments. We systematically evaluated perturbation magnitude (), attack iterations (k), and gradient step size () within FreeLB and PGD attack paradigms, revealing fundamental trade-offs among attack efficiency, visual stealth, and model robustness. Key findings demonstrate a non-monotonic relationship where optimal parameterization balances maximal model vulnerability with minimal perceptual distortion—a crucial equilibrium for practical deployment in marine environments prone to electronic warfare (EW). Sensitivity analysis establishes quantitative design principles for adversarial training in surveillance applications.

The curve result graphs in this section (

Figure 10), the vertical axis represents the accuracy rate of the model at this training moment, and the horizontal axis represents the total number of training rounds (epochs) used. Epochs are closely related to batch size and iterations. The relationship among the three is epoch = batch size × iterations.

4.6.1. Epsilon-Adversarial Perturbation Values

Further analysis of the impact of preprocessing parameters on effectiveness reveals that the

parameter controls the magnitude of adversarial perturbations (

Figure 11). In the FreeLB attack method, parameters

= 0.0025 and

k (denoting the gradient step size for updating input samples at each step) = 5 were fixed while varying

. Experimental results demonstrate that as

increases (0.05, 0.075), perturbations gradually approach the original attack state of test images, potentially improving prediction accuracy. This improvement occurs because moderate perturbations effectively challenge the model to learn more robust feature representations without significantly distorting the underlying semantic content. Peak accuracy occurs at

= 0.1, representing an optimal balance where perturbations are sufficiently strong to enhance model robustness while remaining subtle enough to preserve image recognizability. At this sweet spot, the adversarial samples are potent enough to expose and rectify vulnerable decision boundaries, yet they maintain fidelity to the original data distribution, preventing the model from learning distorted features. But beyond this threshold (

= 0.25, 0.5), excessive perturbations become perceptible, causing significant semantic distortion that deviates from realistic vessel appearances and causing classifiers to misidentify images and consequently reducing accuracy despite higher attack success rates. This degradation occurs because overly aggressive perturbations force the model to overfit to unrealistic, artifact-laden samples, compromising its ability to generalize to both clean data and subtly perturbed inputs. For practical marine vessel surveillance, selecting an appropriate

value is critical, requiring careful trade-offs between prediction accuracy and acceptable perturbation levels to ensure adversarial samples effectively attack target models without human-perceptible artifacts. Parameter selection must therefore balance attack success rates against image fidelity and task performance, with

= 0.1 emerging as the optimal value that maximizes robustness gains while minimizing semantic distortion in maritime surveillance contexts.

4.6.2. K-Attack Iteration Number Value

The hyperparameter

k controls the number of attack iterations. Since only the PGD method among the four selected attack methods requires determination of iteration count, experiments were conducted with

k as the variable while holding other parameters constant. The results demonstrate on

Figure 12: When

k is set to 1, prediction accuracy on the test image set reaches its peak. As

k sequentially increases to 3, 5, 7, and 9, prediction accuracy progressively declines. Notably, while these accumulated perturbations remain largely imperceptible to human vision across all tested k-values (k ≤ 9). This indicates that increasing the step count or iterations of PGD attacks amplifies perturbations in adversarial samples, thereby reducing prediction accuracy for adversarial inputs when other parameters remain unchanged.

This phenomenon likely occurs because higher iteration counts drive adversarial samples closer to decision boundaries, making models more susceptible to misdirection and consequently degrading prediction accuracy. This highlights a critical different in adversarial attacks: perturbations that are visually negligible to humans can be strategically optimized through iterative refinement to become highly deceptive for machine learning models. While increasing PGD attack iterations enhances the divergence between adversarial and original samples—potentially improving adversarial sample quality—it simultaneously compromises the model’s prediction accuracy.

4.6.3. Alpha-Gradient Update Step Value

In experiments employing the FreeLB attack method with fixed

and variable

, the impact of

on images is illustrated in

Figure 13. This parameter governs both the gradient update step size during adversarial sample generation and the perturbation magnitude per step applied to original samples—higher

values intensify perturbations, enhancing adversarial sample aggressiveness while reducing naturalness. This creates a crucial different where perturbations remain largely imperceptible to human vision yet become increasingly potent against machine learning models. As shown in

Figure 14: At low

values (e.g., 0.00025), prediction accuracy on the test image set remains relatively high due to minimal gradient steps producing insignificant perturbations, making models harder to mislead. Optimal accuracy (82%) occurs at moderate

(0.0025), where attackers successfully deceive models without excessive distortion. At high

(0.025 and 0.25), accuracy progressively declines as oversized gradient steps cause image overcorruption, hindering correct recognition.

Attack success rates can be modulated through adjustment. Excessively small values weaken attack effectiveness, while excessively large values induce destructive over-perturbation—both scenarios impair attack success. Therefore, must be contextually tuned in practical applications to achieve optimal attack performance.

5. Conclusions and Future Prospects

This study proposes a novel vessel type detection network framework employing an innovative training strategy, designed to enhance the model’s resilience against adversarial perturbations and thereby improve the security of automated ship surveillance systems. Specifically, the method consists of two key phases: the adversarial attack generation phase and the adversarial training phase. During the adversarial attack generation phase, gradient information of the model is computed to identify directions that induce misclassification. Perturbations are then added based on the loss function’s gradients to generate adversarial examples. These adversarial examples are subsequently incorporated into the training dataset. In the adversarial training phase, the model learns by training on both original and adversarial samples, continuously refining the classification decision boundary to ensure correct classification when confronted with perturbed samples. This process effectively enhances the model’s defense capability against concealed adversarial attacks and reduces misclassifications caused by minor perturbations.

Experimental results demonstrate that RAFS-Net, owing to its distinct training methodology compared to traditional ship surveillance models, excels across multiple vessel detection tasks with varying perturbation intensities. It not only maintains high recognition efficiency in disturbed environments but also effectively performs detection tasks in pristine conditions. Furthermore, ablation experiments conducted on the Ship Outboard Adversary Attack Image Dataset enabled RAFS-Net to achieve optimal parameter configurations. This verifies that the model reaches peak performance under these settings, yielding significant enhancements for vessel safety management.

To improve nearshore maritime management efficiency within the shipping safety context, future research will prioritize two directions. First, enhancing the model’s capability to recognize local vessel features will enable accurate identification without relying on excessive features, thereby minimizing the impact of disturbed information and further boosting the robustness and safety of ship surveillance models. Additionally, in real-world marine environments, visible-light image data acquisition is often compromised by non-adversarial perturbations such as rain/fog, varying illumination conditions, or lens distortions. These factors adversely affect model performance. Consequently, subsequent research will comprehensively analyze model behavior under diverse perturbation scenarios, providing valuable references for maritime management studies.

In summary, benefiting from the training strategy of the RAFS-Net framework, it proficiently handles ship monitoring and identification tasks in both perturbed and non-perturbed environments while maintaining highly efficient and precise recognition performance. This not only effectively addresses the current research gap but also tangibly enhances the management security of vessel traffic activity information in complex marine environments characterized by multiple interference sources.