Investigation on the Aeroelastic Characteristics of Ultra-Long Flexible Blades for an Offshore Wind Turbine in Extreme Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Model

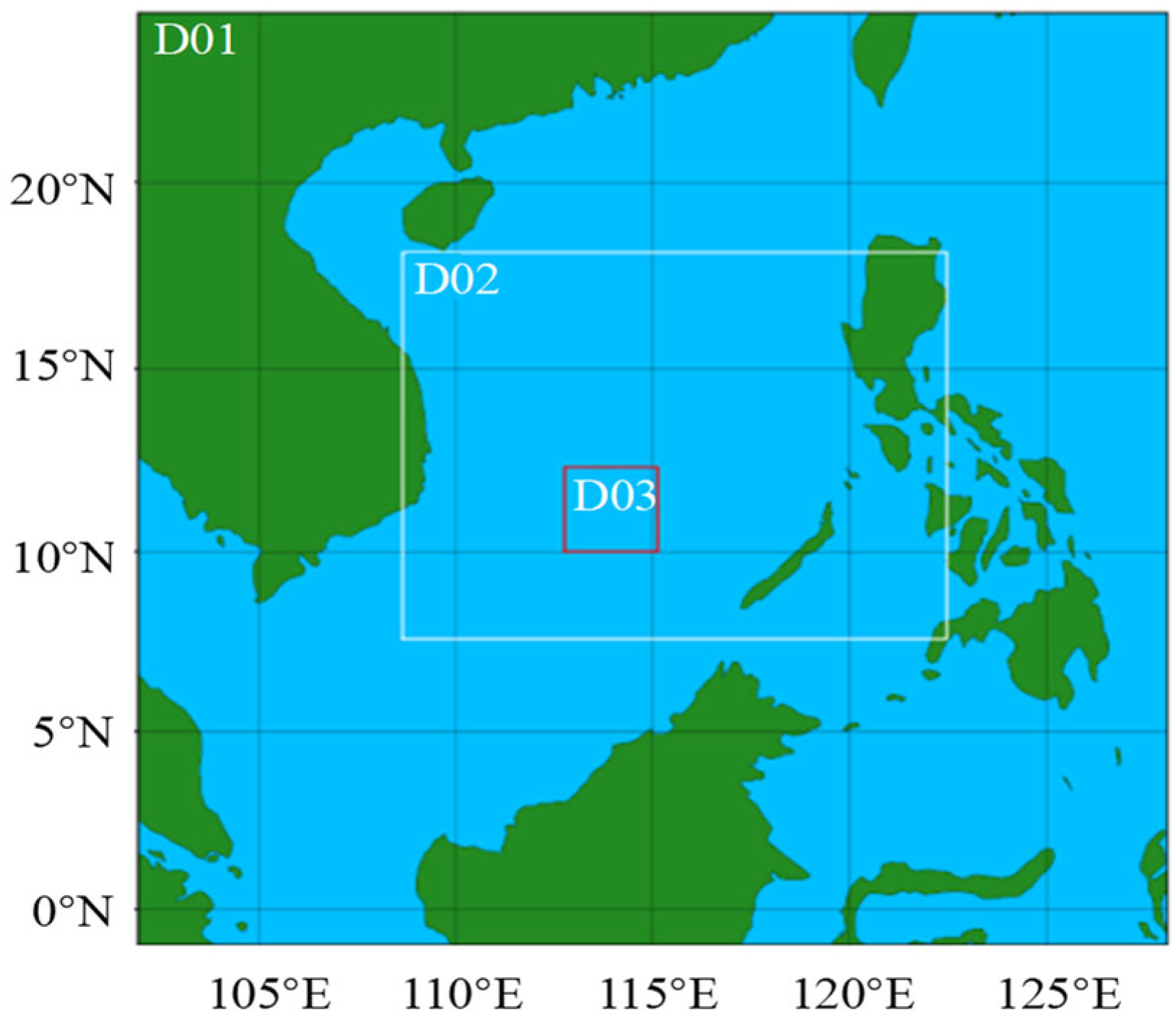

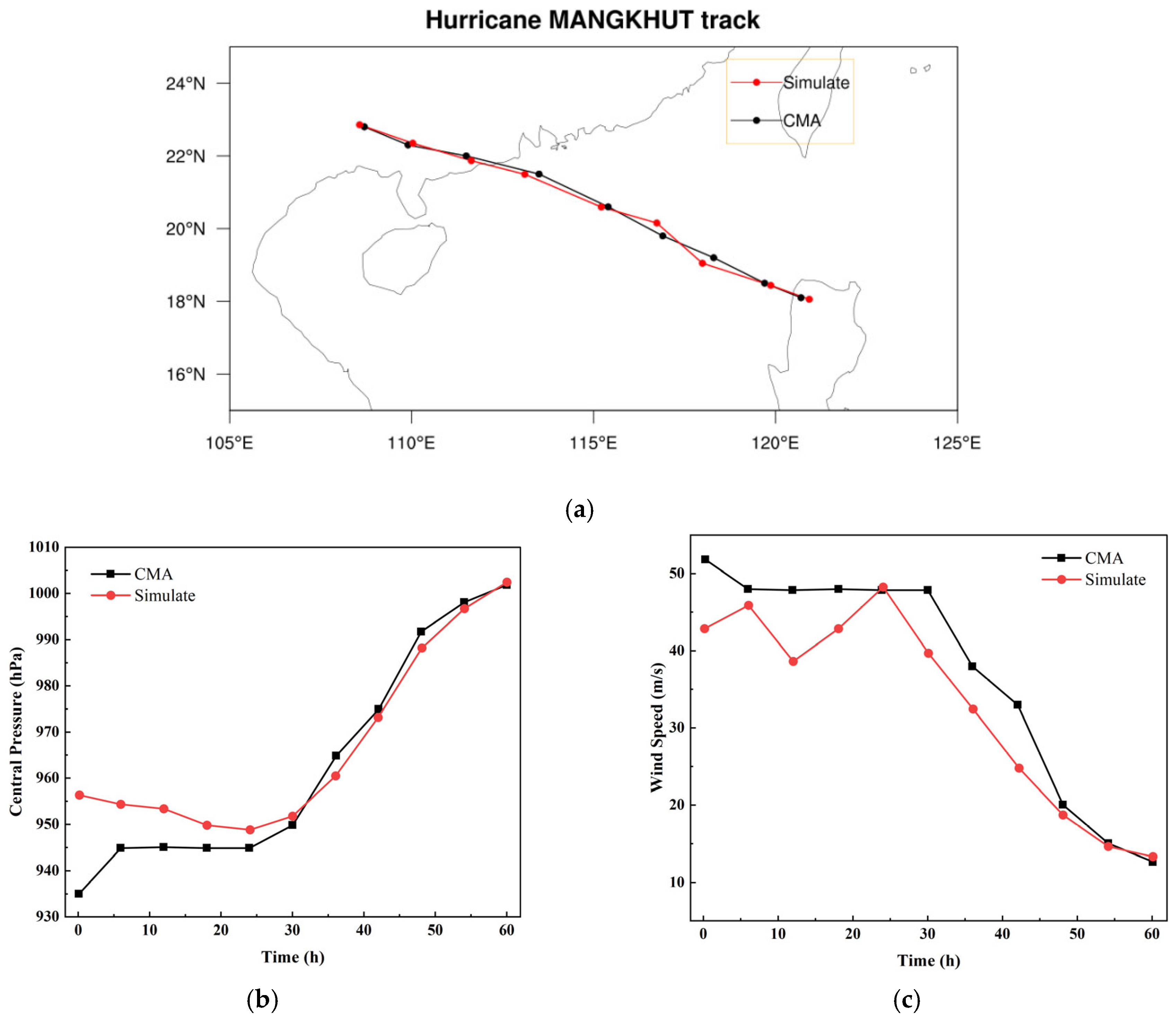

2.1. Typhoon Model

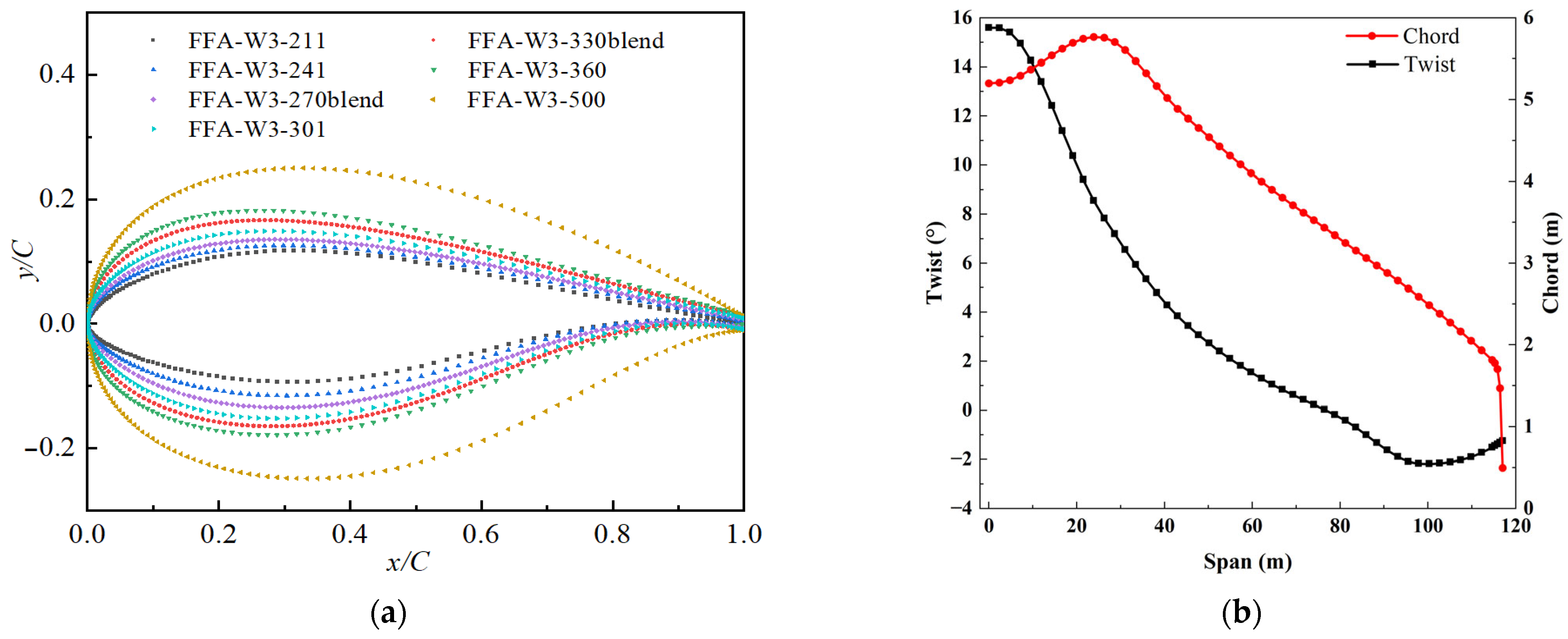

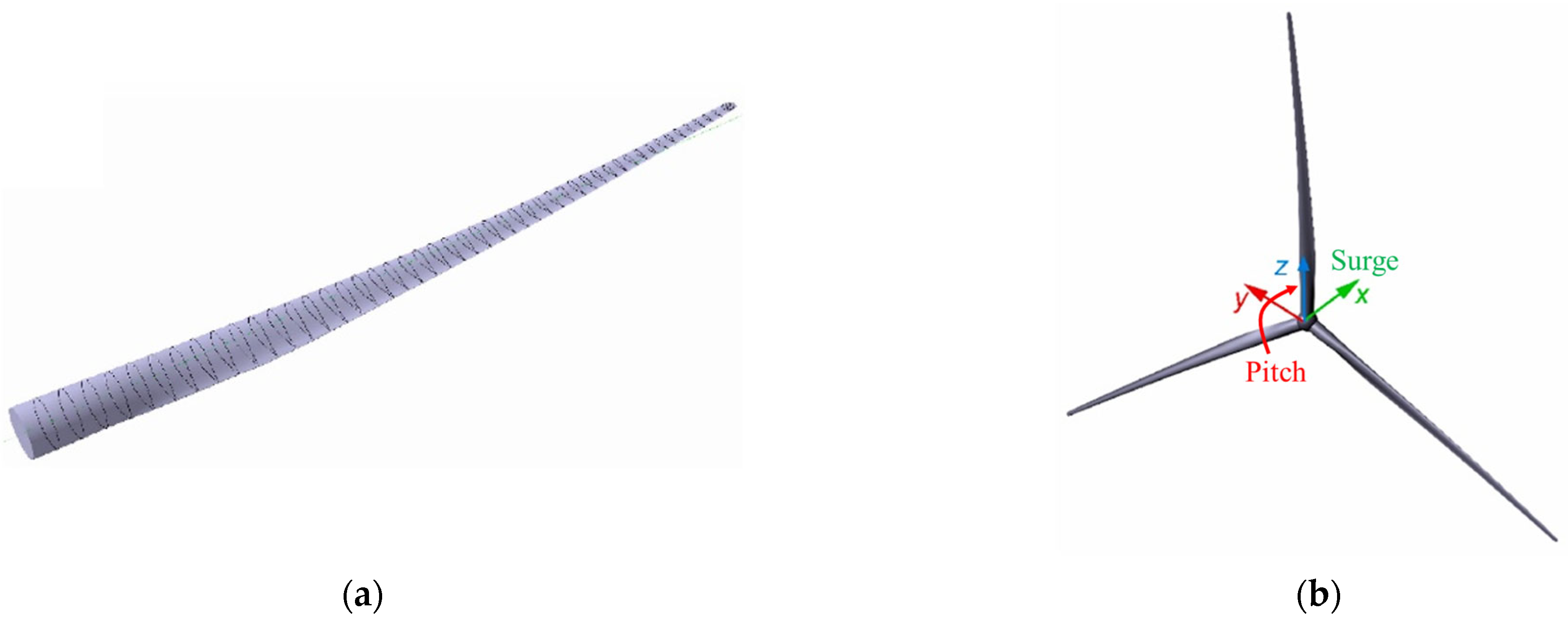

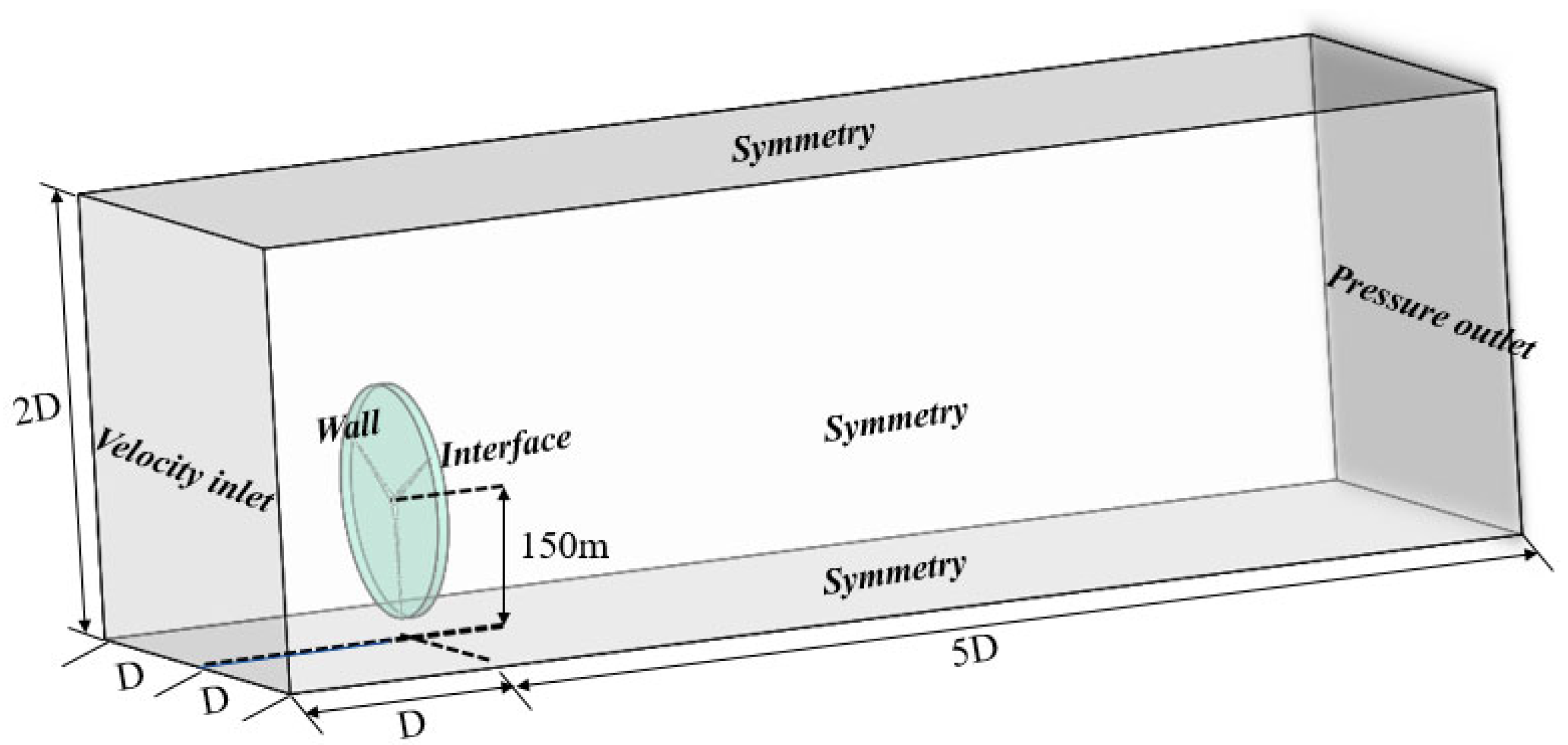

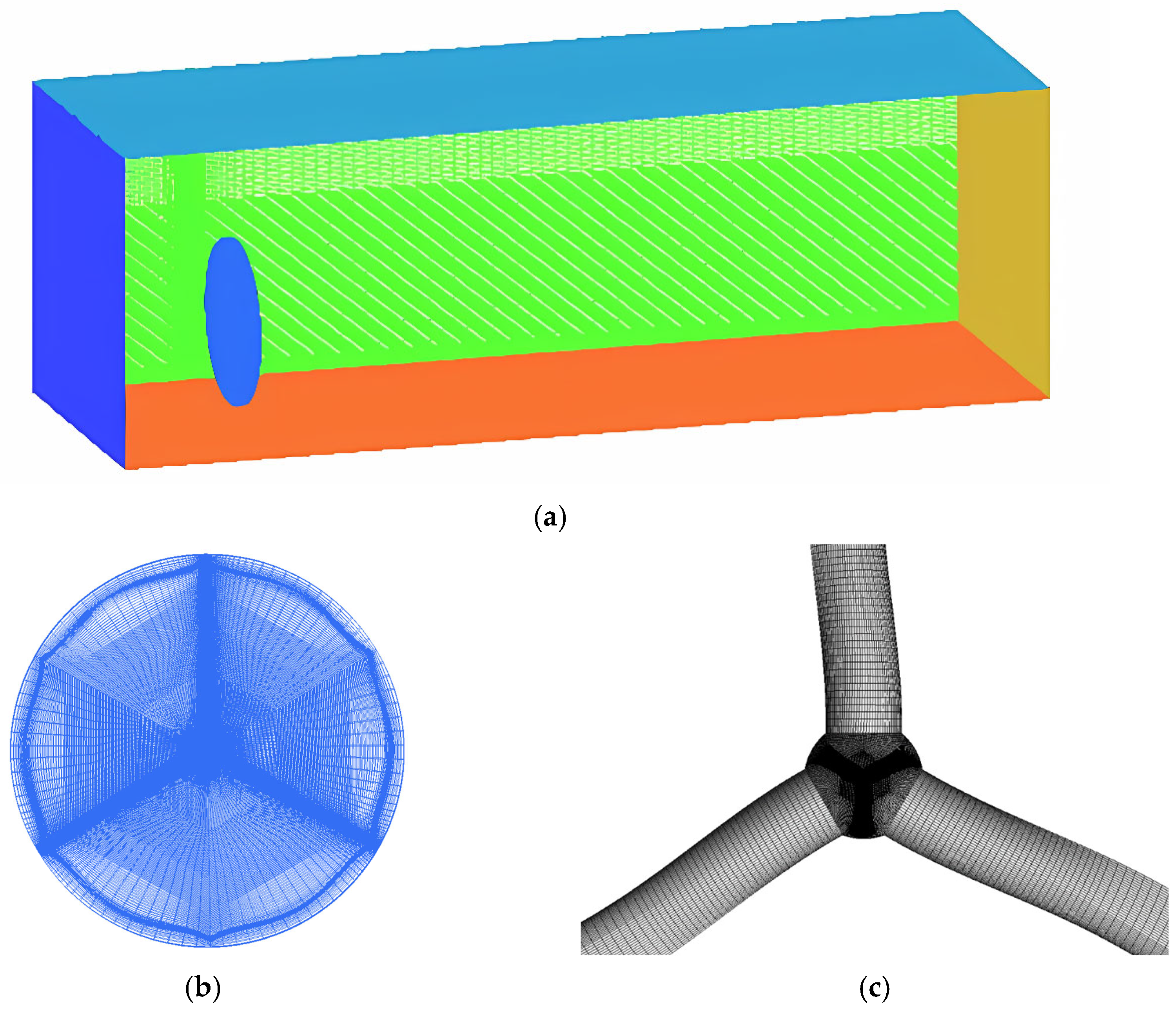

2.2. Blade Aerodynamic Model

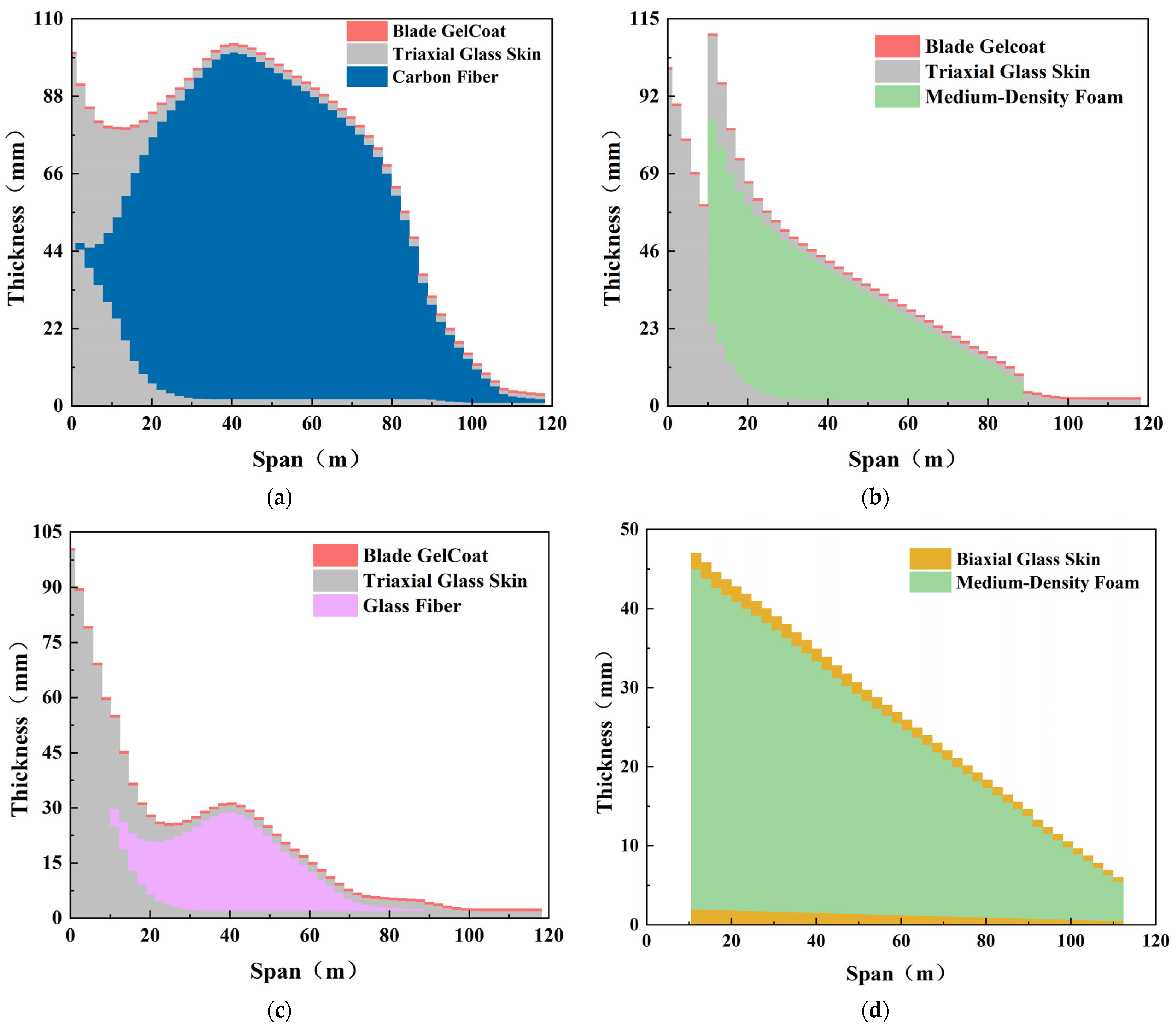

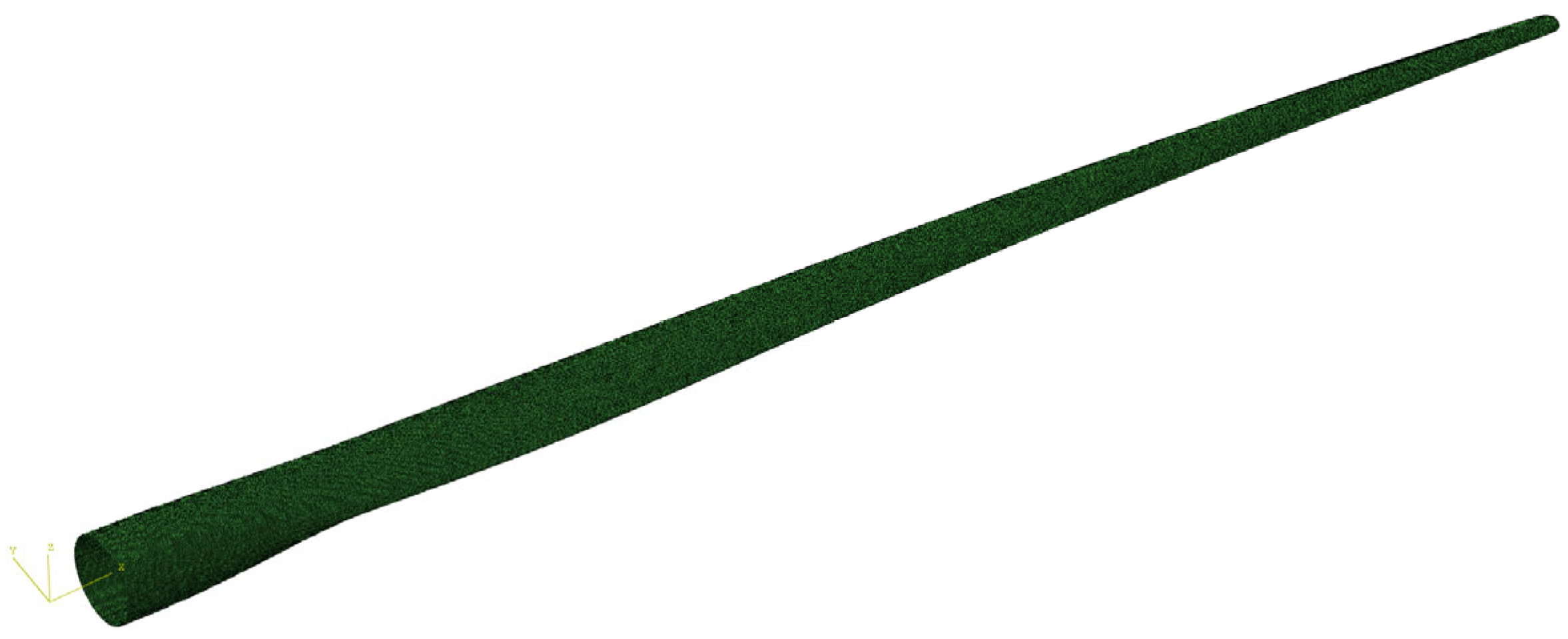

2.3. Blade Structural Model

3. Typhoon-Induced Blade Load and Responses

3.1. Model Validation

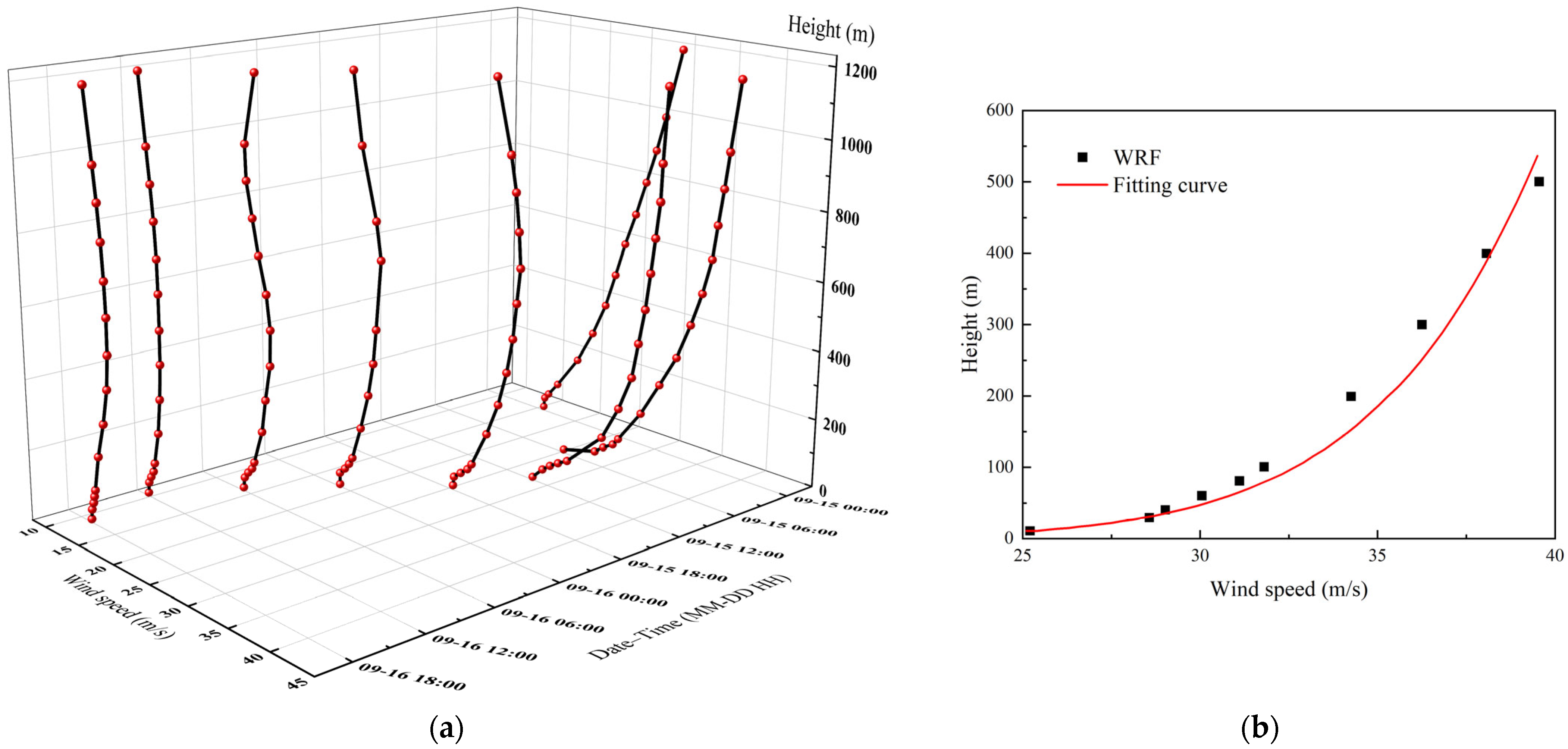

3.1.1. Typhoon Model Verification

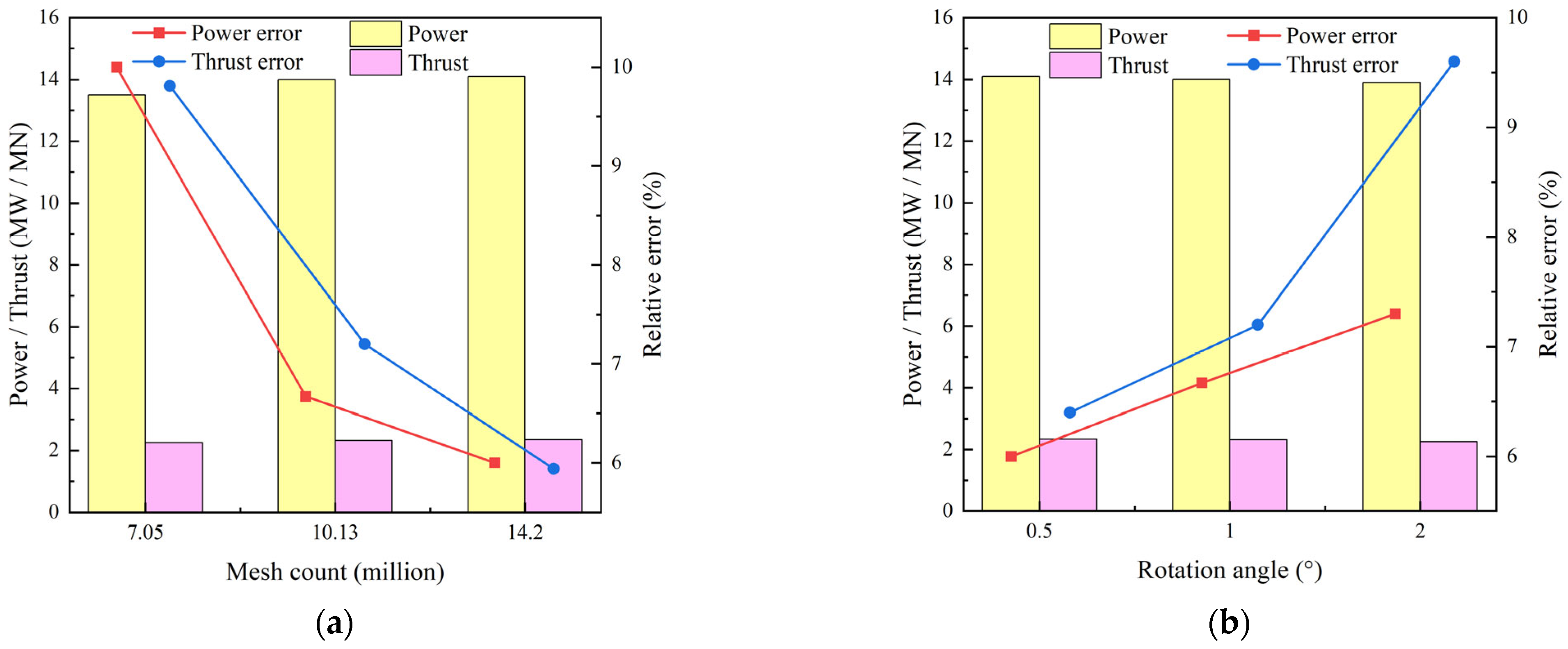

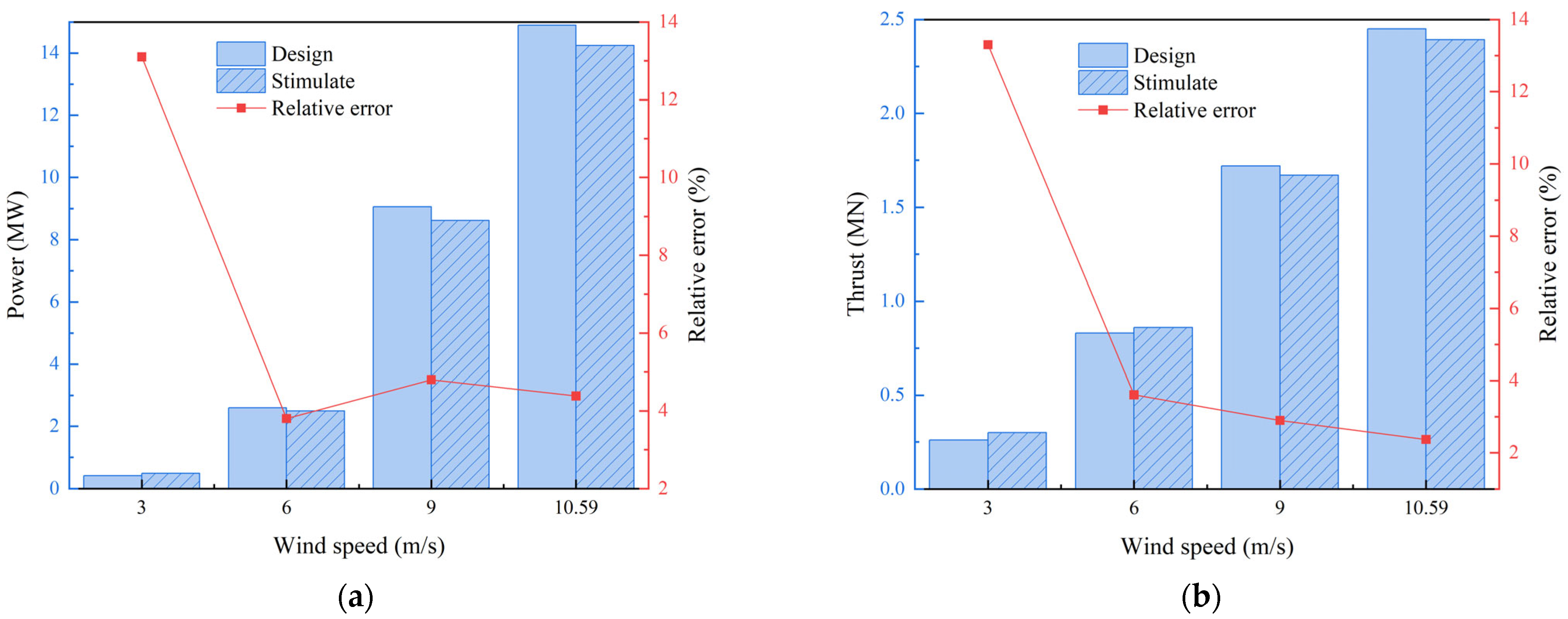

3.1.2. Blade Aerodynamic Model Verification

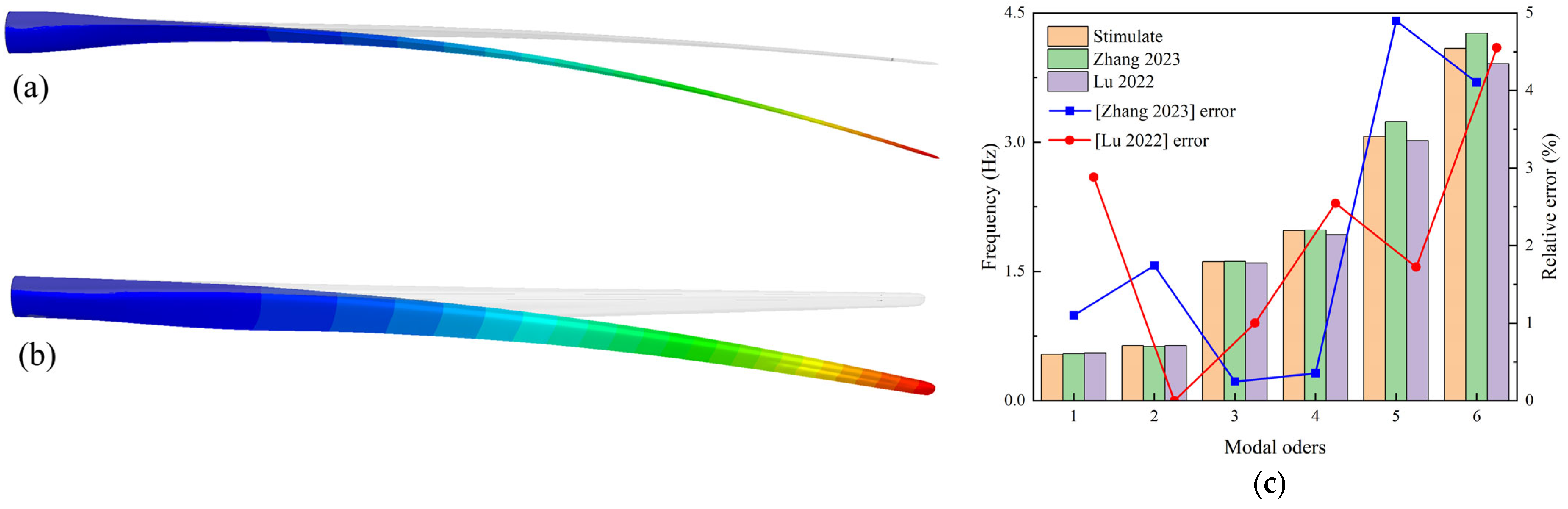

3.1.3. Blade Structural Model Verification

3.2. Typhoon Vertical Wind Profile Analysis

3.3. Blade Aerodynamic Load Analysis

3.3.1. Influence of Wind Turbine Yaw

3.3.2. Influence of Blade Pitch

3.3.3. Comprehensive Performance of Rotor

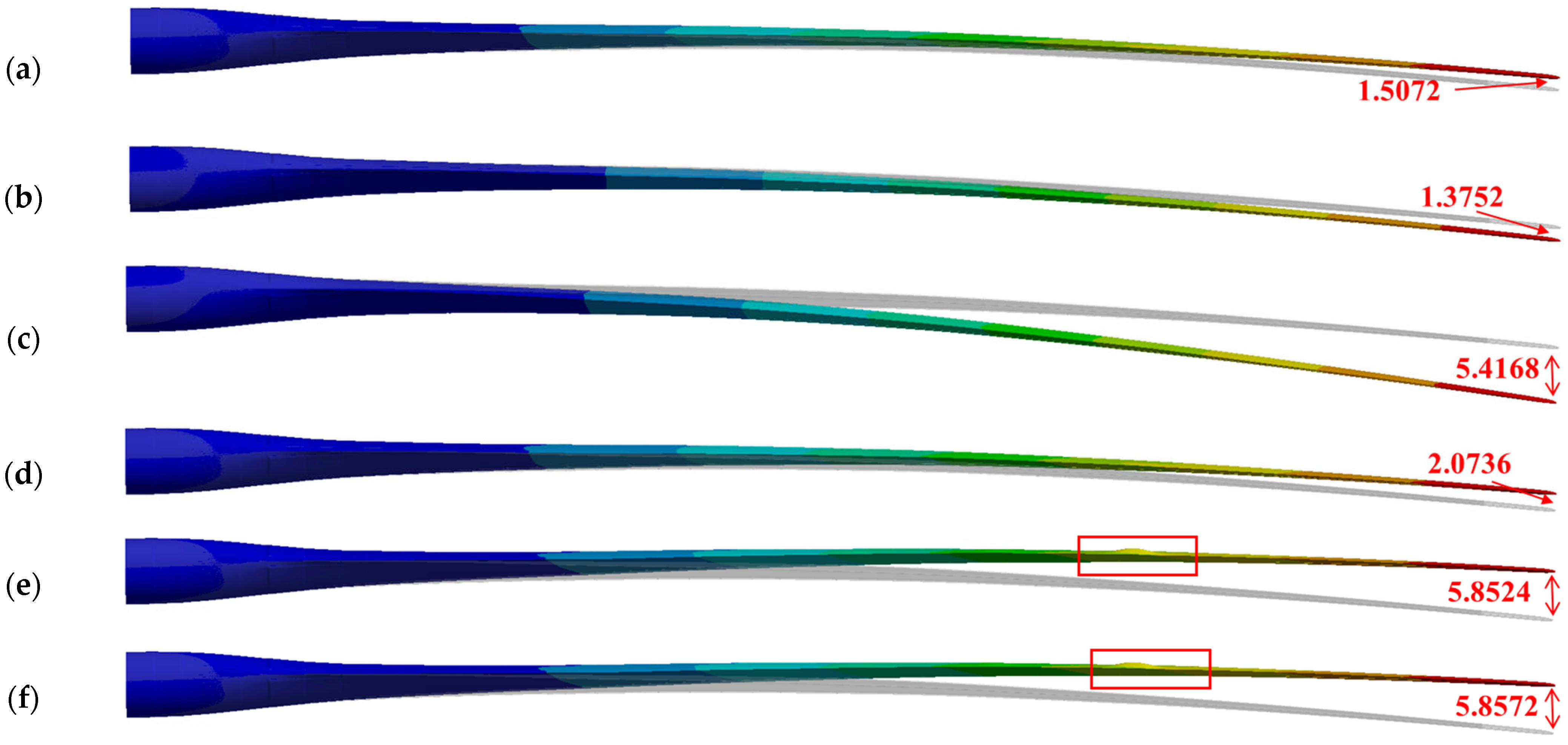

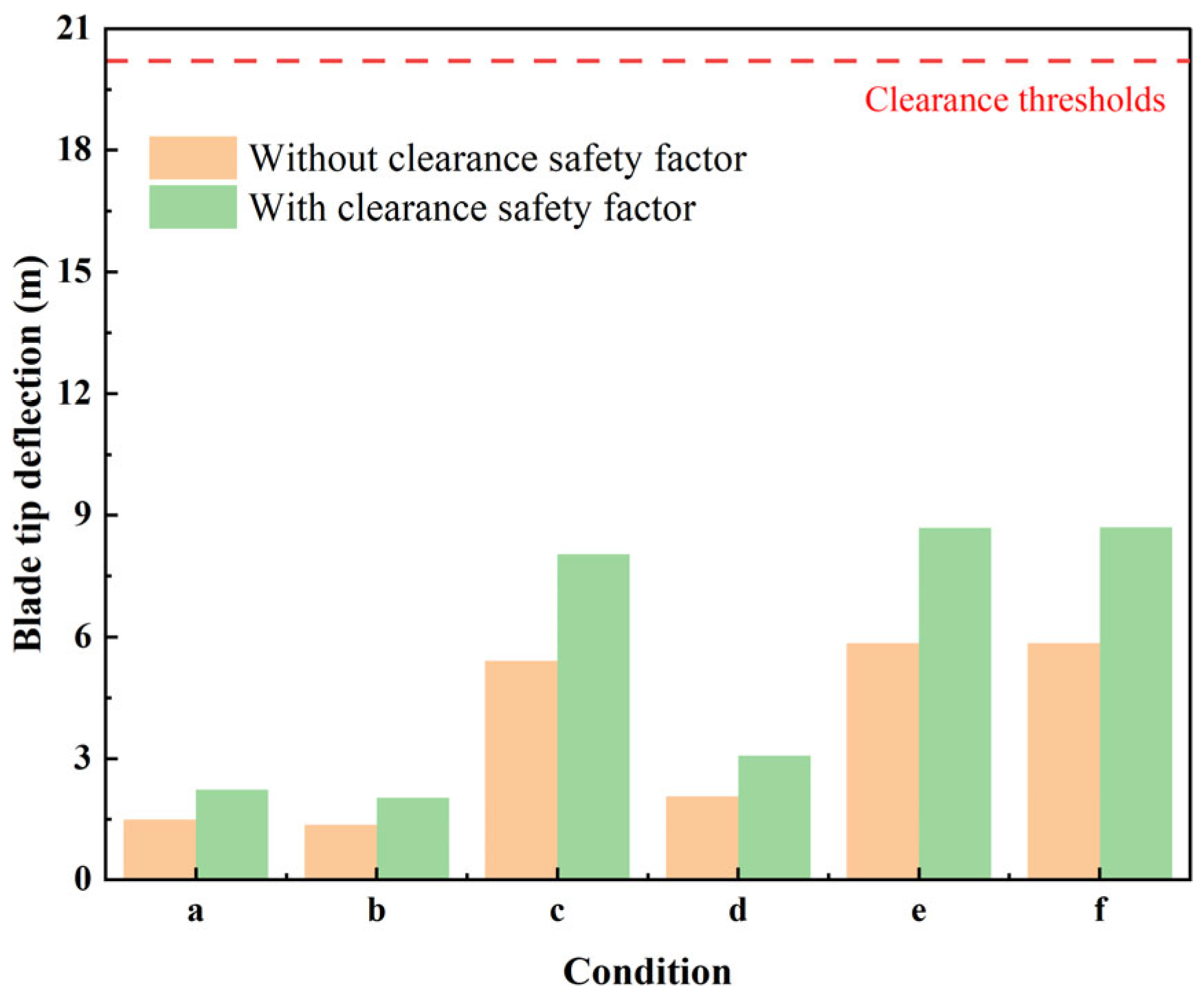

3.4. Blade Structural Response Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WRF | Weather Research and Forecasting |

| CMA | China Meteorological Administration |

| 3DVAR | Three-Dimensional Variational Assimilation |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

References

- Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chang, R.; He, G.; Tang, W.; Gao, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Optimizing wind/solar combinations at finer scales to mitigate renewable energy variability in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 132, 110151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjith, L.R.; Bavanish, B. A review on biomass and wind as renewable energy for sustainable environment. Chemosphere 2022, 293, 133579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, A.; Musial, W.; Hammond, R.; Mulas Hernando, D.; Duffy, P.; Beiter, P.; Perez, P.; Baranowski, R.; Reber, G.; Spitsen, P. Offshore Wind Market Report: 2024 Edition; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2024.

- Costoya, X.; DeCastro, M.; Carvalho, D.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. On the suitability of offshore wind energy resource in the United States of America for the 21st century. Appl. Energy 2020, 262, 114537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pan, S.; Chen, Y.; Yao, Y.; Xu, C. Assessment of combined wind and wave energy in the tropical cyclone affected region: An application in China seas. Energy 2022, 260, 125020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xu, E.; Zhang, H. An improved typhoon risk model coupled with mitigation capacity and its relationship to disaster losses. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.S.; Liou, Y.A. Typhoon strength rising in the past four decades. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2022, 36, 100446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.M.; Lei, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Typhoon track, intensity, and structure: From theory to prediction. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 39, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Kou, Y.; Wang, X. Research on the statistical characteristics of typhoon frequency. Ocean Eng. 2020, 209, 107489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Fan, Y.; Deng, Y. Blades Flutter Suppression in Large Wind Turbines: A Review. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2025, 46, 556–566. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, K.; Cui, X.; Jing, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, S.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Bionic inspired flutter suppression method for offshore ultra-long wind turbine blades. Renew. Energy 2025, 239, 122091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Fan, Y.; Du, T.; Deng, Y. A Bidirectional Tuned Mass Damper for Flutter Suppression in Ultra-Large Offshore Wind Turbine Flexible Blades. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y. Victims of Super Typhoon Yagi Include Hainan Wind Farm. Dialogue. Earth. (11 September 2024). Available online: https://dialogue.earth/en/digest/victims-of-super-typhoon-yagi-include-hainan-wind-farm/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Ishihara, T.; Yamaguchi, A.; Takahara, K.; Mekaru, T.; Matsuura, S. An analysis of damaged wind turbines by typhoon Maemi in 2003. In Proceedings of the Sixth Asia-Pacific Conference on Wind Engineering, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 12–14 September 2005; pp. 1413–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Xu, J.Z. Structural failure analysis of wind turbines impacted by super typhoon Usagi. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2016, 60, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Yang, W.; Han, J. Experimental study of non-stationary aerodynamic effects on the wind turbine nacelles under extreme wind events. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 116103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ke, S.T.; Wang, T.G.; Zhu, S.Y. Typhoon-induced vibration response and the working mechanism of large wind turbine considering multi-stage effects. Renew. Energy 2020, 153, 740–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Xu, M.; Mao, J.; Zhu, H. Unsteady performances of a parked large-scale wind turbine in the typhoon activity zones. Renew. Energy 2020, 149, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Li, G.; Duan, L. The impact of extreme wind conditions and yaw misalignment on the aeroelastic responses of a parked offshore wind turbine. Ocean Eng. 2024, 313, 119403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, K.; Zhao, M.; Liu, H. Study on the aeroelastic response of wind turbine blades with pitch system failure and strategies for typhoon resistance. Ocean Eng. 2025, 324, 120734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, T.; Hong, X. Feasibility of typhoon models and wind power spectra on response analysis of parked wind turbines. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2023, 242, 105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Yu, M.; Xie, J.; Xue, X. Super typhoon impact on the dynamic behavior of floating offshore wind turbine drivetrains: A comprehensive study. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Shi, W.; Chai, W.; Fu, X.; Li, L.; Li, X. Extreme structural response prediction and fatigue damage evaluation for large-scale monopile offshore wind turbines subject to typhoon conditions. Renew. Energy 2023, 208, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, E.; Rinker, J.; Sethuraman, L.; Zahle, F.; Anderson, B.; Barter, G.E.; Abbas, N.; Meng, F.; Bortolotti, P.; Skrzypinski, W.; et al. IEA Wind TCP Task 37: Definition of the IEA 15-Megawatt Offshore Reference Wind Turbine; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2020.

- Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Wind velocity prediction at wind turbine hub height based on CFD model. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Materials for Renewable Energy and Environment, Chengdu, China, 19–21 August 2013; Volume 1, pp. 411–414. [Google Scholar]

- Menter, F.R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, S.; Pei, C.; Xu, D.; Yuan, X. Impact of FY-3D MWRI and MWHS-2 Radiance Data Assimilation in WRFDA System on Forecasts of Typhoon Muifa. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammara, I.; Leclerc, C.; Masson, C. A viscous three-dimensional differential/actuator-disk method for the aerodynamic analysis of wind farms. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2002, 124, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Shen, C.; Chen, N.Z. Aerodynamic and structural analysis for blades of a 15MW floating offshore wind turbine. Ocean Eng. 2023, 287, 115785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.M.; Ke, S.T.; Wu, H.X.; Gao, M.E.; Tian, W.X.; Wang, H. A novel forecasting method of flutter critical wind speed for the 15 MW wind turbine blade based on aeroelastic wind tunnel test. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2022, 230, 105195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Tamura, Y.; Kikuchi, N.; Saito, M.; Nakayama, I.; Matsuzaki, Y. Wind characteristics of a strong typhoon. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2009, 97, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, C.; Yang, H.; Tan, M.; Xiang, D. Analysis of the vertical characteristics of horizontal wind near the surface of shenzhen during the visit of typhoon mangkhut. Guangdong Meteorol. 2021, 43, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, R.; Pol, S. Wind tunnel studies of wind turbine yaw and speed control effects on the wake trajectory and thrust stabilization. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, S. The effect of yaw speed and delay time on power generation and stress of a wind turbine. Int. J. Green Energy 2023, 20, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Stallard, T.; Stansby, P.K. Large-scale offshore wind energy installation in northwest India: Assessment of wind resource using Weather Research and Forecasting and levelized cost of energy. Wind. Energy 2021, 24, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Yang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, F.; Qian, Q.; Li, Q. Aerodynamic load evaluation of leading edge and trailing edge windward states of large-scale wind turbine blade under parked condition. Appl. Energy 2023, 350, 121744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61400-1; Wind Energy Generation Systems—Part 1: Design Requirements. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

| Description | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Blade length | 117 | m |

| Root diameter | 5.20 | m |

| Max chord | 5.77 | m |

| Max chord spanwise position | 27.2 | m |

| Blade mass | 65,250 | kg |

| First flapwise natural frequency | 0.555 | Hz |

| First edgewise natural frequency | 0.642 | Hz |

| Material | E (MPa) | G (MPa) | μ | ρ (kg/m3) | UTSL (MPa) | UCSL (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blade gelcoat | 3440 | 1323 | 0.3 | 1235 | 74 × 10−6 | 87 × 10−6 |

| Triaxial glass | 28,700 | 8400 | 0.5 | 1940 | 396 | 448.9 |

| Biaxial glass | 11,100 | 13,530 | 0.5 | 1940 | 42.9 | 70.7 |

| Glass fiber | 44,600 | 3270 | 0.262 | 1940 | 609.2 | 474.7 |

| Carbon fiber | 114,500 | 5990 | 0.27 | 1220 | 1546 | 1047 |

| Foam | 129.2 | 48.95 | 0.32 | 130 | 2.083 | 1.563 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, W.; Wang, Q.; Xu, F.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Fan, Y. Investigation on the Aeroelastic Characteristics of Ultra-Long Flexible Blades for an Offshore Wind Turbine in Extreme Environments. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2076. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112076

Liao W, Wang Q, Xu F, Zhang M, Yang J, Fan Y. Investigation on the Aeroelastic Characteristics of Ultra-Long Flexible Blades for an Offshore Wind Turbine in Extreme Environments. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(11):2076. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112076

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Weiliang, Qian Wang, Feng Xu, Mingming Zhang, Jianjun Yang, and Youhua Fan. 2025. "Investigation on the Aeroelastic Characteristics of Ultra-Long Flexible Blades for an Offshore Wind Turbine in Extreme Environments" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 11: 2076. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112076

APA StyleLiao, W., Wang, Q., Xu, F., Zhang, M., Yang, J., & Fan, Y. (2025). Investigation on the Aeroelastic Characteristics of Ultra-Long Flexible Blades for an Offshore Wind Turbine in Extreme Environments. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(11), 2076. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112076