Monitoring Harmful Algal Blooms in the Southern California Current Using Satellite Ocean Color and In Situ Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

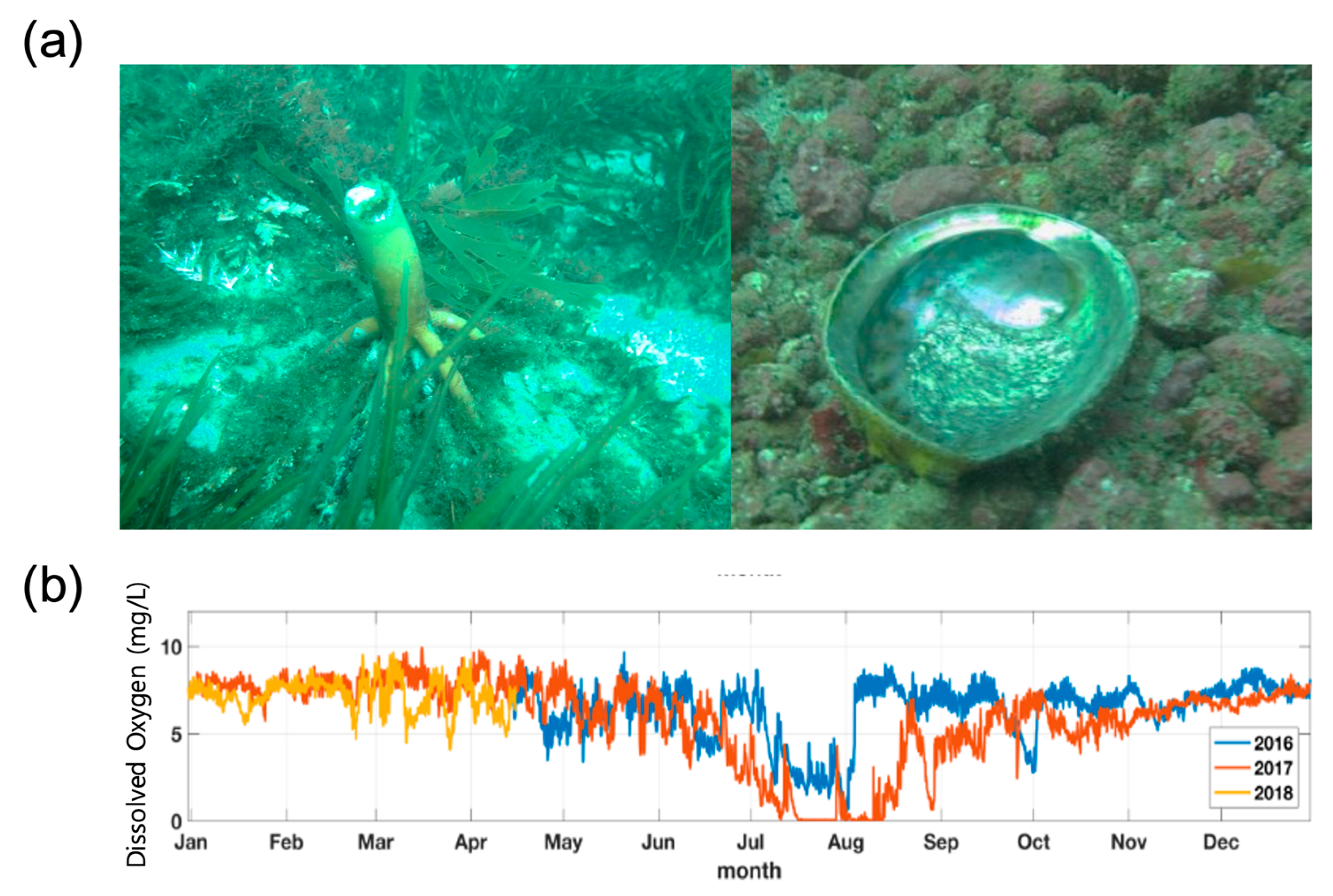

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. In Situ Data Collection

2.3. Satellite Data Acquisition and Analysis

2.4. Application of Normalized Red Tide Index

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Uncertainty Estimation

3. Result

3.1. HAB Species Composition and Spatial Distribution

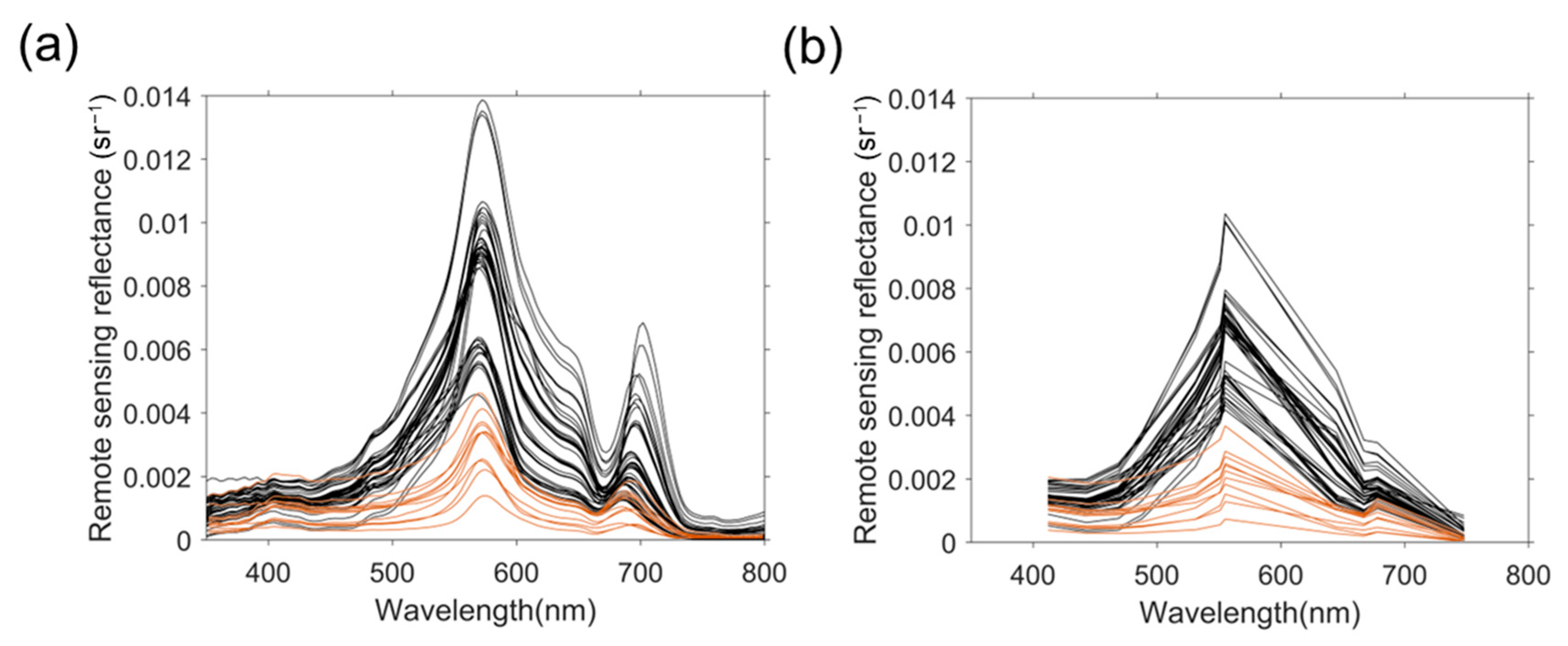

3.2. Spectral Reflectance and NRTI Distribution

3.3. Relationship Between Red Tide Density and NRTI

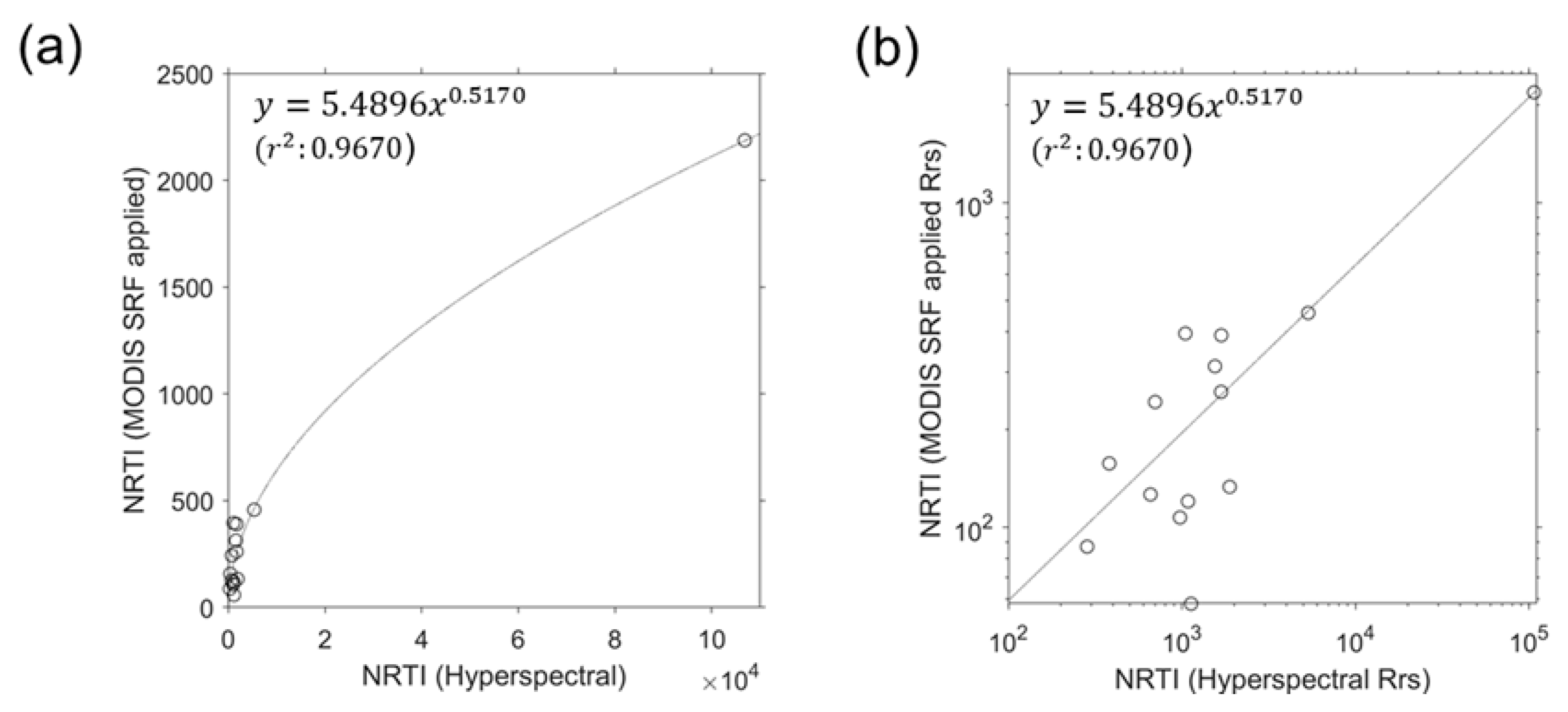

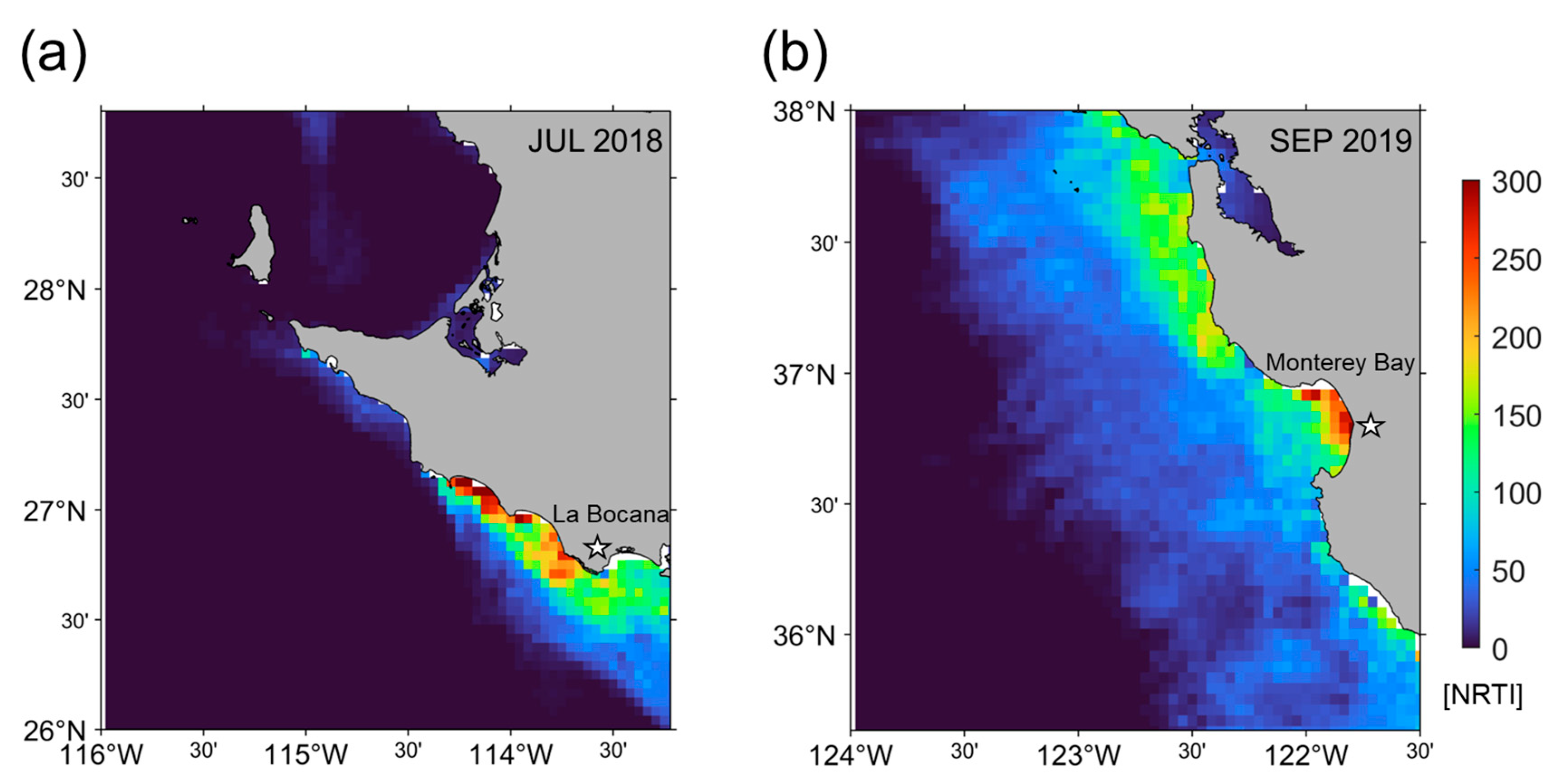

3.4. NRTI Application to MODIS Data

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jackson, J.B.; Kirby, M.X.; Berger, W.H.; Bjorndal, K.A.; Botsford, L.W.; Bourque, B.J.; Bradbury, R.H.; Cooke, R.; Erlandson, J.; Estes, J.A. Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal ecosystems. Science 2001, 293, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, A.H.; Gedan, K.B. Climate change and dead zones. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 1395–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagelkerken, I.; Connell, S.D. Global alteration of ocean ecosystem functioning due to increasing human CO2 emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 13272–13277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Hughes, B.B.; Kroeker, K.J.; Owens, A.; Wong, C.; Micheli, F. Who wins or loses matters: Strongly interacting consumers drive seagrass resistance under ocean acidification. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 808, 151594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Gambi, M.C.; Kroeker, K.J.; Munari, M.; Peay, K.; Micheli, F. Resilient consumers accelerate the plant decomposition in a naturally acidified seagrass ecosystem. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 4558–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, B.S.; Frazier, M.; O’Hara, C.C.; Vargas-Fonseca, O.A.; Lombard, A.T. Cumulative impacts to global marine ecosystems projected to more than double by mid-century. Science 2025, 389, 1216–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Kim, T.; Lee, J. Seasonally Intensified Mud Shrimp Bioturbation Hinders Seagrass Restoration. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, K.M.; Velthuis, M.; Van de Waal, D.B. Meta-analysis reveals enhanced growth of marine harmful algae from temperate regions with warming and elevated CO2 levels. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2607–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhao, D.; Hu, C.; Xu, W.; Anderson, D.M.; Li, Y.; Song, X.-P.; Boyce, D.G.; Gibson, L. Coastal phytoplankton blooms expand and intensify in the 21st century. Nature 2023, 615, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdalet, E.; Fleming, L.E.; Gowen, R.; Davidson, K.; Hess, P.; Backer, L.C.; Moore, S.K.; Hoagland, P.; Enevoldsen, H. Marine harmful algal blooms, human health and wellbeing: Challenges and opportunities in the 21st century. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2016, 96, 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Fensin, E.; Gobler, C.J.; Hoeglund, A.E.; Hubbard, K.A.; Kulis, D.M.; Landsberg, J.H.; Lefebvre, K.A.; Provoost, P.; Richlen, M.L. Marine harmful algal blooms (HABs) in the United States: History, current status and future trends. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallegraeff, G.M.; Anderson, D.M.; Belin, C.; Bottein, M.-Y.D.; Bresnan, E.; Chinain, M.; Enevoldsen, H.; Iwataki, M.; Karlson, B.; McKenzie, C.H. Perceived global increase in algal blooms is attributable to intensified monitoring and emerging bloom impacts. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberg, J.H. The effects of harmful algal blooms on aquatic organisms. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2002, 10, 113–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dolah, F.M. Marine algal toxins: Origins, health effects, and their increased occurrence. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000, 108, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegraeff, G.M. Harmful algal blooms: A global overview. Man. Harmful Mar. Microalgae 2003, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Laffoley, D.; Baxter, J. Ocean deoxygenation: Everyone’s problem-causes, impacts. In Consequences and Solutions; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.R.; Lilley, M.; Shutler, J.; Lowe, C.; Artioli, Y.; Torres, R.; Berdalet, E.; Tyler, C.R. Assessing risks and mitigating impacts of harmful algal blooms on mariculture and marine fisheries. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 1663–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M.C.; Stumpf, R.P.; Ransibrahmanakul, V.; Truby, E.W.; Kirkpatrick, G.J.; Pederson, B.A.; Vargo, G.A.; Heil, C.A. Evaluation of the use of SeaWiFS imagery for detecting Karenia brevis harmful algal blooms in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 91, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, J.; Kitaura, Y.; Touke, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Tanaka, A.; Murakami, H.; Suzuki, T.; Matsuoka, K.; Nakata, H. Satellite detection of red tide in Ariake Sound, 1998–2001. J. Oceanogr. 2006, 62, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.R.; Kudela, R.M.; Kahru, M.; Chao, Y.; Rosenfeld, L.K.; Bahr, F.L.; Anderson, D.M.; Norris, T.A. Initial skill assessment of the California harmful algae risk mapping (C-HARM) system. Harmful Algae 2016, 59, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.-S.; Park, K.-A.; Chae, J.; Park, J.-E.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, J.-H. Red tide detection using deep learning and high-spatial resolution optical satellite imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 5838–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aláez, F.M.B.; Palenzuela, J.M.T.; Spyrakos, E.; Vilas, L.G. Machine learning methods applied to the prediction of pseudo-nitzschia spp. blooms in the Galician rias baixas (NW Spain). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierssen, H.; Gierach, M.; Guild, L.; Mannino, A.; Salisbury, J.; Schollaert Uz, S.; Scott, J.; Townsend, P.; Turpie, K.; Tzortziou, M. Synergies between NASA’s hyperspectral aquatic missions PACE, GLIMR, and SBG: Opportunities for new science and applications. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2023, 128, e2023JG007574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinić, I.; Rousseaux, C.S.; Carroll, I.T.; Chase, A.P.; Kramer, S.J.; Werdell, P.J.; Siegel, D.A.; Dierssen, H.M.; Catlett, D.; Neeley, A. Phytoplankton composition from sPACE: Requirements, opportunities, and challenges. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 302, 113964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binding, C.; Greenberg, T.; Bukata, R. The MERIS Maximum Chlorophyll Index; its merits and limitations for inland water algal bloom monitoring. J. Great Lakes Res. 2013, 39, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.P.; Davis, C.O.; Tufillaro, N.B.; Kudela, R.M.; Gao, B.-C. Application of the hyperspectral imager for the coastal ocean to phytoplankton ecology studies in Monterey Bay, CA, USA. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 1007–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-K.; Min, J.-E.; Noh, J.H.; Han, T.-H.; Yoon, S.; Park, Y.J.; Moon, J.-E.; Ahn, J.-H.; Ahn, S.M.; Park, J.-H. Harmful algal bloom (HAB) in the East Sea identified by the Geostationary Ocean Color Imager (GOCI). Harmful Algae 2014, 39, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-S.; Park, K.-A.; Micheli, F. Derivation of red tide index and density using geostationary ocean color imager (GOCI) data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-S.; Park, K.-A.; Kim, G. Incidence of harmful algal blooms in pristine subtropical ocean: A satellite remote sensing approach (Jeju Island). Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1149657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, E.; Roemmich, D.; Stammer, D. Interannual variability in northeast Pacific circulation. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2006, 111, C04001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, B.M. The California current system—Hypotheses and facts. Prog. Oceanogr. 1979, 8, 191–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cury, P.; Bakun, A.; Crawford, R.J.; Jarre, A.; Quinones, R.A.; Shannon, L.J.; Verheye, H.M. Small pelagics in upwelling systems: Patterns of interaction and structural changes in “wasp-waist” ecosystems. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2000, 57, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpf, J.; Chapman, P. Upwelling Systems of the World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Breitburg, D.; Levin, L.A.; Oschlies, A.; Grégoire, M.; Chavez, F.P.; Conley, D.J.; Garçon, V.; Gilbert, D.; Gutiérrez, D.; Isensee, K. Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 2018, 359, eaam7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boch, C.; Micheli, F.; AlNajjar, M.; Monismith, S.; Beers, J.; Bonilla, J.; Espinoza, A.; Vazquez-Vera, L.; Woodson, C. Local oceanographic variability influences the performance of juvenile abalone under climate change. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, N.H.; Micheli, F.; Aguilar, J.D.; Arce, D.R.; Boch, C.A.; Bonilla, J.C.; Bracamontes, M.Á.; De Leo, G.; Diaz, E.; Enríquez, E. Variable coastal hypoxia exposure and drivers across the southern California Current. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, B.M. Coastal oceanography of western North American from the tip of Baja California to Vancouver Island, coastal segment (8, E). Sea 1998, 11, 345–393. [Google Scholar]

- Checkley Jr, D.M.; Barth, J.A. Patterns and processes in the California Current System. Prog. Oceanogr. 2009, 83, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Kudela, R.; Birch, J.; Blum, M.; Bowers, H.; Chavez, F.; Doucette, G.; Hayashi, K.; Marin III, R.; Mikulski, C. Causality of an extreme harmful algal bloom in Monterey Bay, California, during the 2014–2016 northeast Pacific warm anomaly. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 5571–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaker, L.C.; Broenkow, W.W. The circulation of Monterey Bay and related processes. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 1994, 32, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Durazo, R. Seasonality of the transitional region of the California Current System off Baja California. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2015, 120, 1173–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gárate-Lizárraga, I. Harmful algae blooms along the coast of the Baja California Peninsula. Harmful Algae News 2011, 44, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kudela, R.M.; Pitcher, G.; Probyn, T.; Figueiras, F.; Moita, M.T.; Trainer, V. Harmful algal blooms in coastal upwelling systems. Oceanogr. Soc. 2005, 18, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakun, A.; Nelson, C.S. The seasonal cycle of wind-stress curl in subtropical eastern boundary current regions. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1991, 21, 1815–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazo, R.; Baumgartner, T. Evolution of oceanographic conditions off Baja California: 1997–1999. Prog. Oceanogr. 2002, 54, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaytsev, O.; Cervantes-Duarte, R.; Montante, O.; Gallegos-Garcia, A. Coastal upwelling activity on the Pacific shelf of the Baja California Peninsula. J. Oceanogr. 2003, 59, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahru, M.; Mitchell, B.G. Spectral reflectance and absorption of a massive red tide off southern California. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1998, 103, 21601–21609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannizzaro, J.P.; Carder, K.L.; Chen, F.R.; Heil, C.A.; Vargo, G.A. A novel technique for detection of the toxic dinoflagellate, Karenia brevis, in the Gulf of Mexico from remotely sensed ocean color data. Cont. Shelf Res. 2008, 28, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Moon, J.-E.; Park, Y.-J.; Ishizaka, J. Evaluation of chlorophyll retrievals from Geostationary Ocean color imager (GOCI) for the north-east Asian region. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 184, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyer, A. Coastal upwelling in the California current system. Prog. Oceanogr. 1983, 12, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Fang, T.; Xie, S.; Xu, N.; Zhong, P. Isolation and Characterization of Photosensitive Hemolytic Toxins from the Mixotrophic Dinoflagellate Akashiwo sanguinea. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernet, M.; Neori, A.; Haxo, F. Spectral properties and photosynthetic action in red-tide populations of Prorocentrum micans and Gonyaulax polyedra. Mar. Biol. 1989, 103, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxaran, D.; Lamquin, N.; Park, Y.-J.; Mazeran, C.; Ryu, J.-H.; Wang, M.; Poteau, A. Retrieval of the seawater reflectance for suspended solids monitoring in the East China Sea using MODIS, MERIS and GOCI satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 146, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-S.; Lee, S.; Ahn, J.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; Choi, J.-K.; Ryu, J.-H. Decadal measurements of the first Geostationary Ocean Color Satellite (GOCI) compared with MODIS and VIIRS data. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-H.; Lie, H.-J.; Moon, J.-E. Variations of water turbidity in Korean waters. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Progress in Coastal Engineering and Oceanography, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 9–11 September 1999; Korean Society of Coastal and Ocean Engineers: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1999; pp. 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.-S.; Park, K.-A.; Moon, J.-E.; Kim, W.; Park, Y.-J. Spatial and temporal characteristics and removal methodology of suspended particulate matter speckles from Geostationary Ocean Color Imager data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 3808–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.-H.; Shanmugam, P. Detecting the red tide algal blooms from satellite ocean color observations in optically complex Northeast-Asia Coastal waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 103, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Muller-Karger, F.E.; Taylor, C.J.; Carder, K.L.; Kelble, C.; Johns, E.; Heil, C.A. Red tide detection and tracing using MODIS fluorescence data: A regional example in SW Florida coastal waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 97, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Ishizaka, J.; Wang, S. A simple method for algal species discrimination in East China Sea, using multiple satellite imagery. Geosci. Lett. 2022, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Lee, Z.; Lin, G.; Hu, C.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Yan, J. Sensing an intense phytoplankton bloom in the western Taiwan Strait from radiometric measurements on a UAV. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 198, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Binding, C.E. Consistent multi-mission measures of inland water algal bloom spatial extent using MERIS, MODIS and OLCI. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Cannizzaro, J.; Carder, K.L.; Muller-Karger, F.E.; Hardy, R. Remote detection of Trichodesmium blooms in optically complex coastal waters: Examples with MODIS full-spectral data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2048–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahru, M.; Michell, B.G.; Diaz, A.; Miura, M. MODIS detects a devastating algal bloom in Paracas Bay, Peru. EoS Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2004, 85, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siswanto, E.; Ishizaka, J.; Tripathy, S.C.; Miyamura, K. Detection of harmful algal blooms of Karenia mikimotoi using MODIS measurements: A case study of Seto-Inland Sea, Japan. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 129, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, E.; Mutanga, O.; Rugege, D. Multispectral and hyperspectral remote sensing for identification and mapping of wetland vegetation: A review. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 18, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoya, N.; Grohnfeldt, C.; Chanussot, J. Hyperspectral and multispectral data fusion: A comparative review of the recent literature. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2017, 5, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumby, P.; Green, E.; Edwards, A.; Clark, C. The cost-effectiveness of remote sensing for tropical coastal resources assessment and management. J. Environ. Manag. 1999, 55, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.P.; Fischer, A.M.; Kudela, R.M.; Gower, J.F.; King, S.A.; Marin III, R.; Chavez, F.P. Influences of upwelling and downwelling winds on red tide bloom dynamics in Monterey Bay, California. Cont. Shelf Res. 2009, 29, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudela, R.; Seeyave, S.; Cochlan, W. The role of nutrients in regulation and promotion of harmful algal blooms in upwelling systems. Prog. Oceanogr. 2010, 85, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciotti, A.M.; Lewis, M.R.; Cullen, J.J. Assessment of the relationships between dominant cell size in natural phytoplankton communities and the spectral shape of the absorption coefficient. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2002, 47, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, A.; Bricaud, A. Theoretical results concerning light absorption in a discrete medium, and application to specific absorption of phytoplankton. Deep Sea Res. A Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1981, 28, 1375–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, H.W.; Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Lee, K.; Kim, C.; Kang, E.J.; Kim, Y.R.; Yoon, Y.J.; Lee, S.B. Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) potential in temperate macroalgal forests: A comparative study of chemical and biological net ecosystem production (NEP). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 210, 117327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zu Ermgassen, P.S.; McCormick, H.; Debney, A.; Fariñas-Franco, J.M.; Gamble, C.; Gillies, C.; Hancock, B.; Laugen, A.T.; Pouvreau, S.; Preston, J. European native oyster reef ecosystems are universally collapsed. Conserv. Lett. 2025, 18, e13068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, M.-S.; Arrigo, K.; Smith, A.; Woodson, C.B.; Lee, J.; Micheli, F. Monitoring Harmful Algal Blooms in the Southern California Current Using Satellite Ocean Color and In Situ Data. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2044. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112044

Lee M-S, Arrigo K, Smith A, Woodson CB, Lee J, Micheli F. Monitoring Harmful Algal Blooms in the Southern California Current Using Satellite Ocean Color and In Situ Data. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(11):2044. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112044

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Min-Sun, Kevin Arrigo, Alexandra Smith, C. Brock Woodson, Juhyung Lee, and Fiorenza Micheli. 2025. "Monitoring Harmful Algal Blooms in the Southern California Current Using Satellite Ocean Color and In Situ Data" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 11: 2044. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112044

APA StyleLee, M.-S., Arrigo, K., Smith, A., Woodson, C. B., Lee, J., & Micheli, F. (2025). Monitoring Harmful Algal Blooms in the Southern California Current Using Satellite Ocean Color and In Situ Data. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(11), 2044. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112044