A Boundary-Implicit Constraint Reconstruction Method for Solving the Shallow Water Equations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Governing Equations and Numerical Methods

2.1. Modified Shallow Water Equations

2.2. Time and Space Discretization for SWEs on Triangular Grids

2.3. MUSCL Reconstruction

2.4. BIVWLSQ Boundary Variable Reconstruction

- (1)

- Initialize the inner boundary variable value based on boundary conditions;

- (2)

- Compute the cell gradient at the current time step using Equations (18)–(21);

- (3)

- Calculate the updated inner boundary value and evaluate the convergence criterion.where and are the maximum allowable error and maximum number of iterations for the inner iteration termination criteria, respectively.

- (4)

- If either condition is met, the iteration terminates; otherwise, Steps (2) and (3) are repeated until the criteria are satisfied.

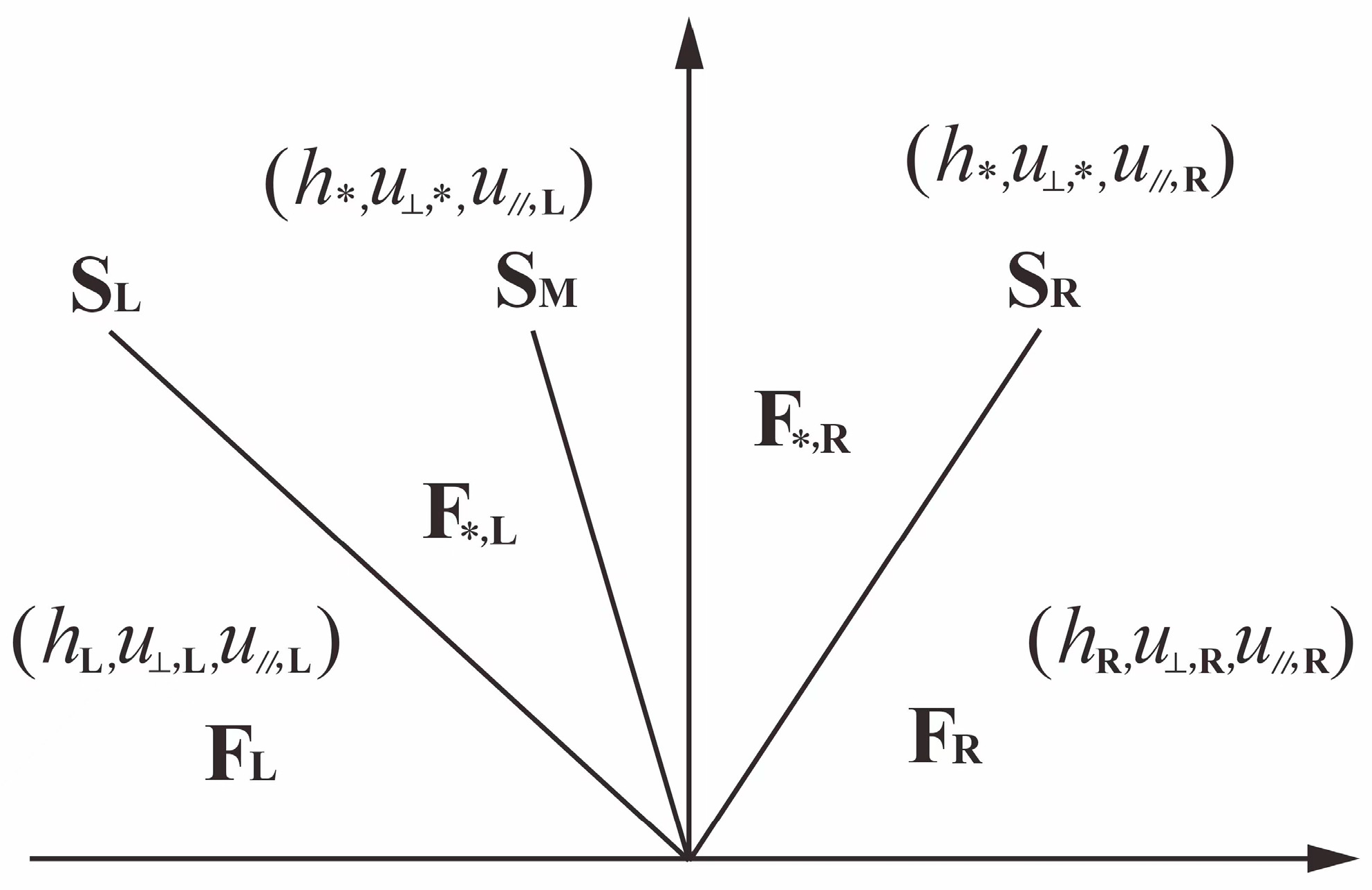

2.5. HLLC Flux Calculation

2.6. Source Term Treatment

2.6.1. Slope Source Term Treatment

2.6.2. Friction Source Term Treatment

2.7. Boundary Conditions

2.7.1. Solid Wall Boundary Condition

2.7.2. Free Outflow Boundary Condition

2.7.3. Water Level Boundary Condition

2.7.4. Flow Velocity Boundary Condition

2.7.5. Unit-Width Discharge Boundary Condition

2.7.6. Flow Boundary Condition

2.8. Stability Criterion

3. Test Cases

3.1. Preservation of Still Water over a Two-Dimensional Bump

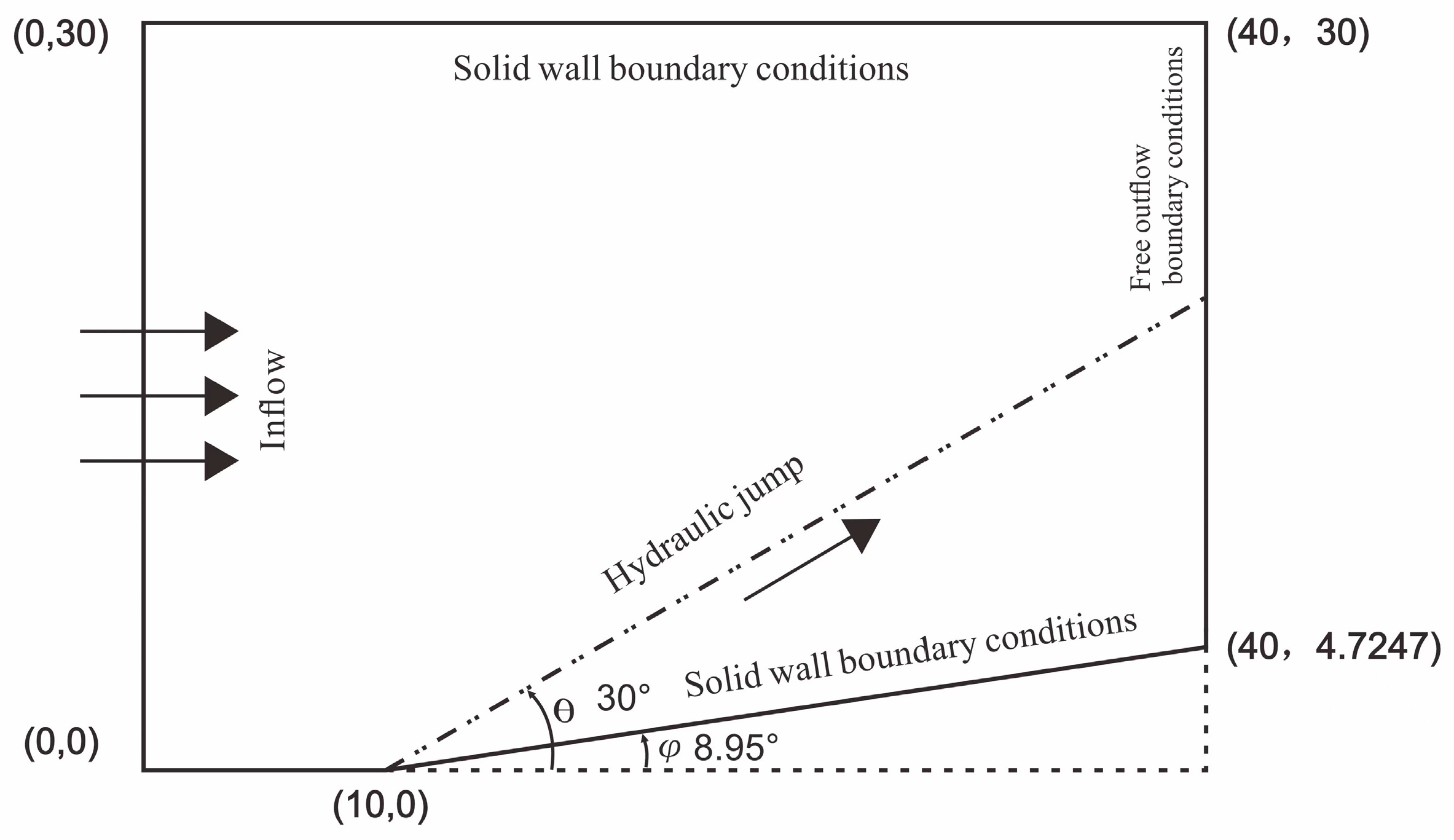

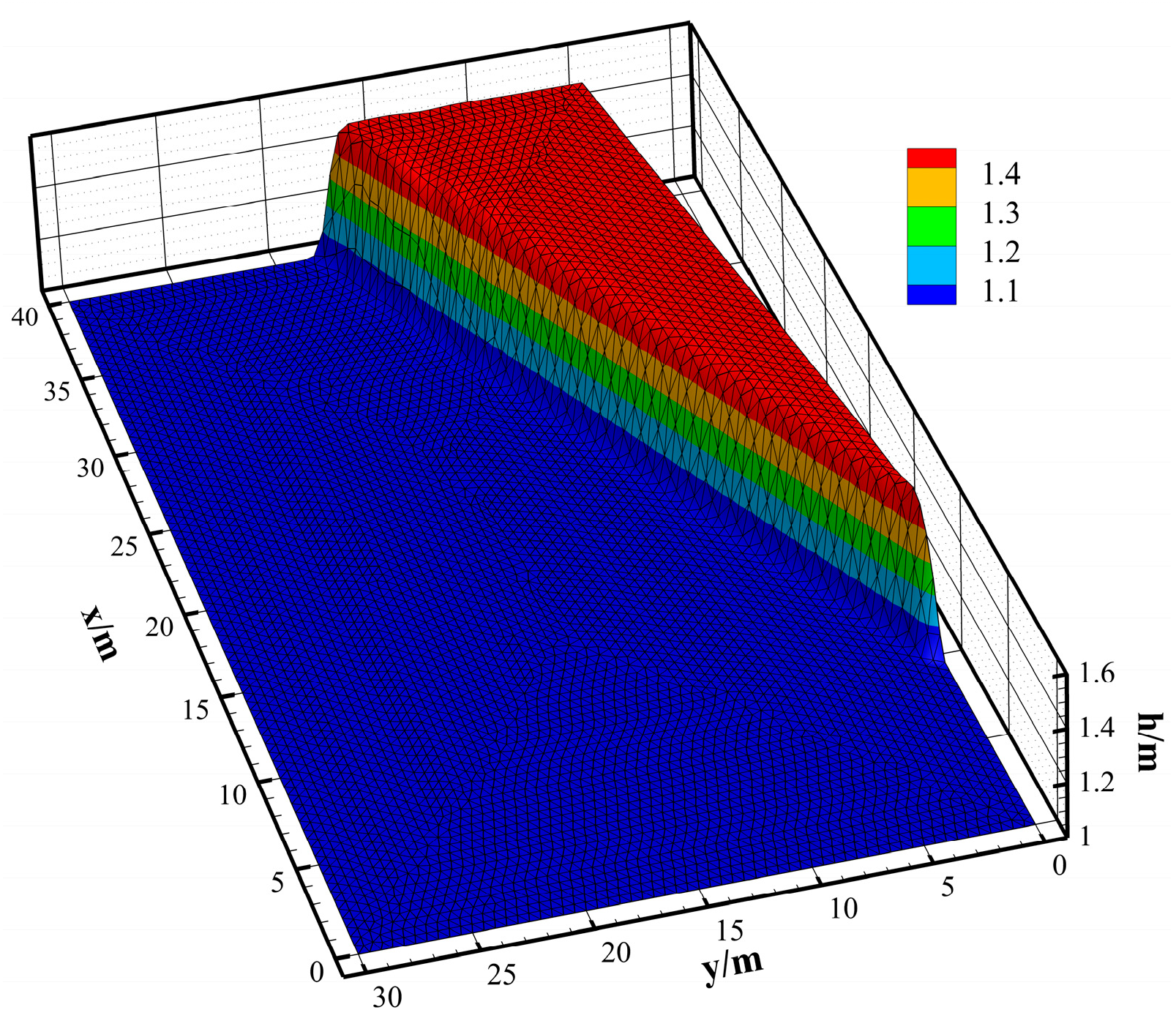

3.2. Oblique Water Leap for Supercritical Flow

3.3. Stoker Dam-Break Test Case

3.4. Two-Dimensional Symmetric Dam-Break Case

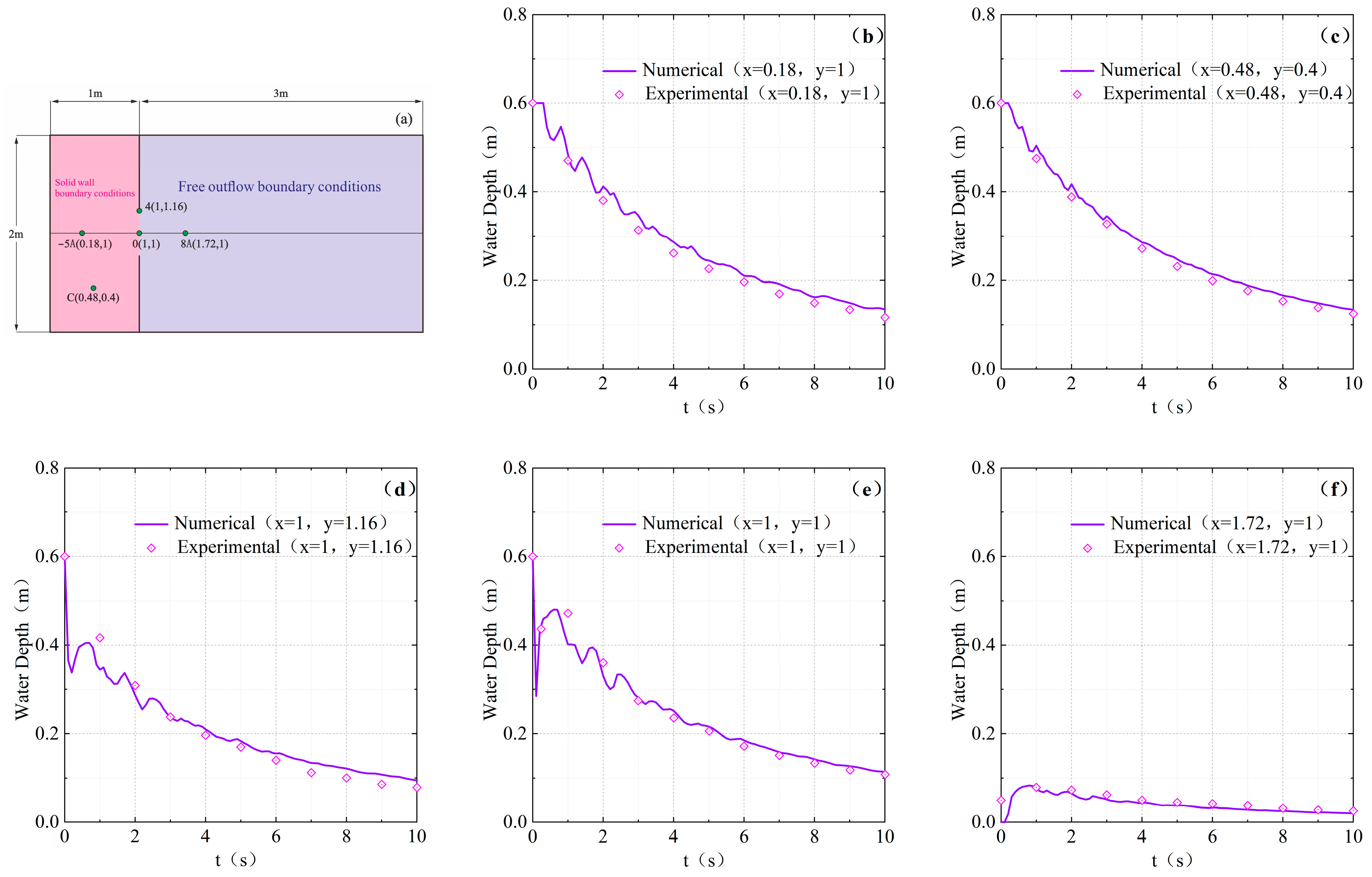

3.5. Dam-Break Flow in an L-Shaped Channel

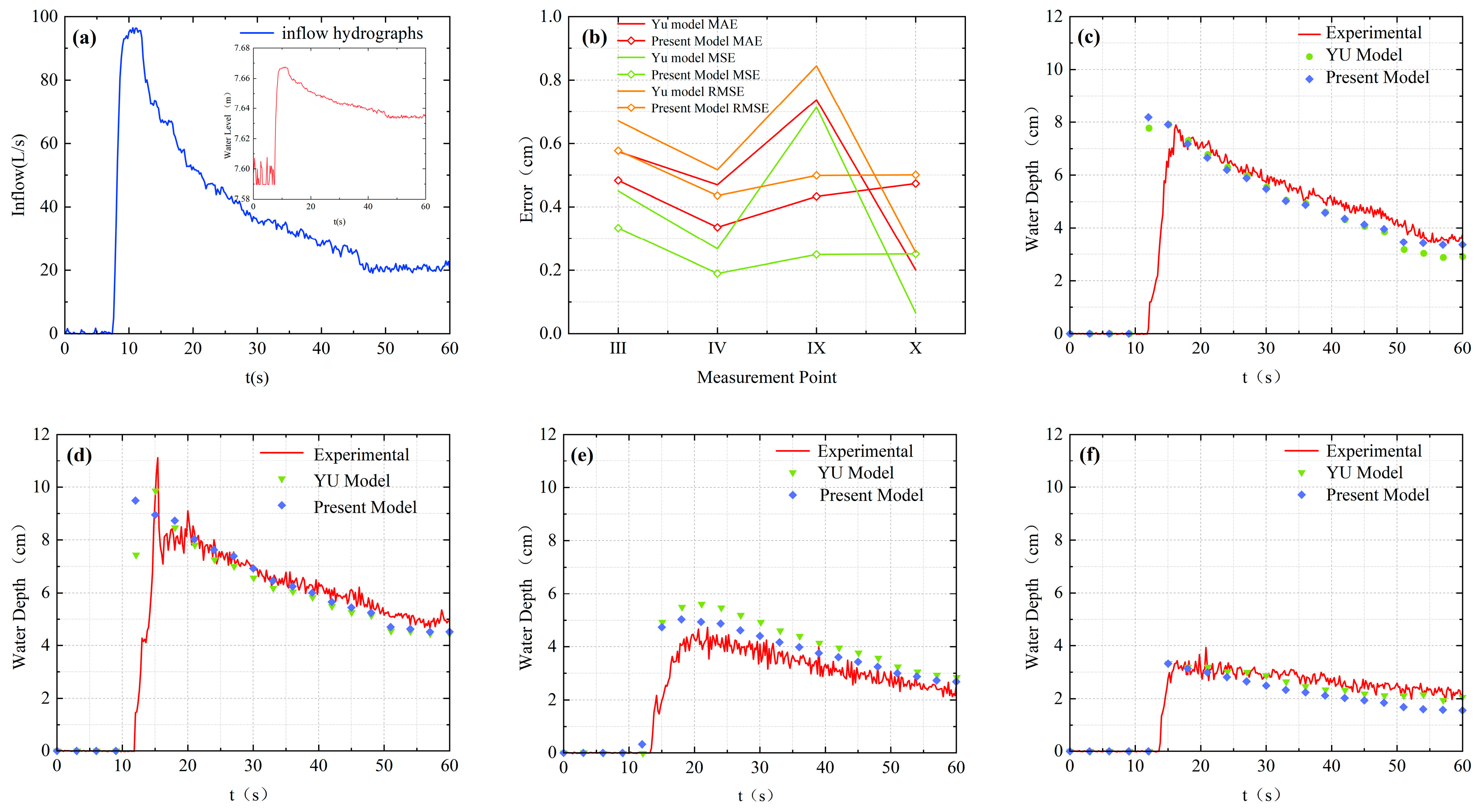

3.6. Toce Urban Inundation Case

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, J.; Liang, Q. Novel Variable Reconstruction and Friction Term Discretisation Schemes for Hydrodynamic Modelling of Overland Flow and Surface Water Flooding. Adv. Water Resour. 2022, 163, 104187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, W.; Huang, G.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, F. A Hybrid Shallow Water Approach with Unstructured Triangular Grids for Urban Flood Modeling. Environ. Model. Softw. 2023, 166, 105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksyuk, A.I.; Malakhov, M.A.; Belikov, V.V. The Exact Riemann Solver for the Shallow Water Equations with a Discontinuous Bottom. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 450, 110801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; He, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Guo, L. A Refined Method for the Simulation of Catchment Rainfall–Runoff Based on Satellite–Precipitation Downscaling. J. Hydrol. 2025, 653, 132795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diskin, B.; Thomas, J.L.; Nielsen, E.J.; Nishikawa, H.; White, J.A. Comparison of Node-Centered and Cell-Centered Unstructured Finite-Volume Discretizations: Viscous Fluxes. AIAA J. 2010, 48, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H. From Hyperbolic Diffusion Scheme to Gradient Method: Implicit Green–Gauss Gradients for Unstructured Grids. J. Comput. Phys. 2018, 372, 126–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, M.; Brahmachary, S.; Thirumalaisamy, R.; Dalal, A.; Natarajan, G. A New Green–Gauss Reconstruction on Unstructured Meshes. Part I: Gradient Reconstruction. J. Comput. Phys. 2020, 422, 108325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Dong, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H. An Improved Global-Direction Stencil Based on the Face-Area-Weighted Centroid for the Gradient Reconstruction of Unstructured Finite Volume Methods. Chin. Phys. B 2020, 29, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Chen, B. A Vertex-Based Reconstruction for Cell-Centered Finite-Volume Discretization on Unstructured Grids. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 451, 110827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Hinkelmann, R. An Efficient Unstructured MUSCL Scheme for Solving the 2D Shallow Water Equations. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 66, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hou, J.; Gao, X.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Sun, X. Urban Inundation Response Law Analysis to Characteristics of Designed Rainstorms Based on Coupled Hydrodynamic and Rainfall-Tracking Model. J. Hydrol. 2024, 632, 130870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhou, J.; Guo, J.; Zou, Q.; Liu, Y. A Robust Well-Balanced Finite Volume Model for Shallow Water Flows with Wetting and Drying over Irregular Terrain. Adv. Water Resour. 2011, 34, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Huang, G.; Wu, C. Efficient Finite-Volume Model for Shallow-Water Flows Using an Implicit Dual Time-Stepping Method. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2015, 141, 4015004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoudi, T.; Mohamed, M.S.; Seaid, M. Novel Adaptive Finite Volume Method on Unstructured Meshes for Time-Domain Wave Scattering and Diffraction. Comput. Math. Appl. 2023, 141, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Su, H.; Xu, C. A Constrained Boundary Gradient Reconstruction Method for Unstructured Finite Volume Discretization of the Euler Equations. Comput. Fluids 2023, 252, 105774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, S.; Berger, M. Two-Dimensional Slope Limiters for Finite Volume Schemes on Non-Coordinate-Aligned Meshes. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2013, 35, A2163–A2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Pan, J.; Li, W. Compact High Order Finite Volume Method on Unstructured Grids III: Variational Reconstruction. J. Comput. Phys. 2017, 337, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Chen, B. Modified Multi-Dimensional Limiting Process with Enhanced Shock Stability on Unstructured Grids. Comput. Fluids 2018, 161, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ou, G.; Chen, L.; Ji, W.; Tao, W. An Implicit Scheme for Least-Square Gradient in Coupled Algorithm. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2025, 97, 795–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zou, Y.; Zou, S.; Chang, X.; Zhang, L.; Deng, X. Learning to Solve PDEs with Finite Volume-Informed Neural Networks in a Data-Free Approach. J. Comput. Phys. 2025, 530, 113919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Chen, B. An Iterative Near-Boundary Reconstruction Strategy for Unstructured Finite Volume Method. J. Comput. Phys. 2020, 418, 109621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; White, J.A. An Efficient Cell-Centered Finite-Volume Method with Face-Averaged Nodal-Gradients for Triangular Grids. J. Comput. Phys. 2020, 411, 109423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xia, Y.; Xu, Y. Structure-Preserving Finite Volume Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian WENO Schemes for the Shallow Water Equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2023, 473, 111758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Osher, S.; Chan, T. Weighted Essentially Non-oscillatory Schemes. J. Comput. Phys. 1994, 115, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D. Inflow Boundary Optimized Method in Two-dimensional Hydrophobic Model. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2022, 54, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Z.; Liu, H.; Tu, G.; Huang, W. Water-Balanced Inlet and Outlet Boundary Conditions of the Lattice Boltzmann Method for Shallow Water Equations. Comput. Fluids 2023, 256, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, A.; Banihashemi, M.A. Simple Efficient Algorithm (SEA) for Shallow Flows with Shock Wave on Dry and Irregular Beds. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2008, 56, 2021–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaeini-Hessaroeyeh, M.; Namin, M.M.; Fadaei-Kermani, E. 2-D Dam-Break Flow Modeling Based on Weighted Average Flux Method. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2021, 46, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.G.; Causon, D.M.; Mingham, C.G.; Ingram, D.M. The Surface Gradient Method for the Treatment of Source Terms in the Shallow-Water Equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2001, 168, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, G. Well-Balanced and Positivity-Preserving Wet-Dry Front Reconstruction Scheme for Ripa Models. Appl. Numer. Math. 2025, 213, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraccarollo, L.; Toro, E.F. Experimental and Numerical Assessment of the Shallow Water Model for Two-Dimensional Dam-Break Type Problems. J. Hydraul. Res. 1995, 33, 843–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, E.; Bell, M.J.; Coward, A.; Holt, J. Implementation and Assessment of a Flux Limiter Based Wetting and Drying Scheme in NEMO. Ocean Model. 2020, 155, 101708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottardi, G.; Venutelli, M. Central Scheme for Two-Dimensional Dam-Break Flow Simulation. Adv. Water Resour. 2004, 27, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ion, S.; Marinescu, D.; Cruceanu, S.-G. Numerical Scheme for Solving a Porous Saint-Venant Type Model for Water Flow on Vegetated Hillslopes. Appl. Numer. Math. 2022, 172, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, G.; Zuccalà, D.; Alcrudo, F.; Mulet, J.; Soares-Frazão, S. Flash Flood Flow Experiment in a Simplified Urban District. J. Hydraul. Res. 2007, 45, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Sanders, B.F.; Schubert, J.E.; Famiglietti, J.S. Mesh Type Tradeoffs in 2D Hydrodynamic Modeling of Flooding with a Godunov-Based Flow Solver. Adv. Water Resour. 2014, 68, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costabile, P.; Costanzo, C.; De Lorenzo, G.; Macchione, F. Is Local Flood Hazard Assessment in Urban Areas Significantly Influenced by the Physical Complexity of the Hydrodynamic Inundation Model? J. Hydrol. 2020, 580, 124231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.W.; Rashid, M.; Haider, S.; Khalid, M.; Elfeki, A. Simulation of Urban Flooding Using 3D Computational Fluid Dynamics with Turbulence Model. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, D.; Yang, J.; Fang, M.; Xie, J. A Boundary-Implicit Constraint Reconstruction Method for Solving the Shallow Water Equations. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112036

Wei D, Yang J, Fang M, Xie J. A Boundary-Implicit Constraint Reconstruction Method for Solving the Shallow Water Equations. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(11):2036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112036

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Dingbing, Jie Yang, Ming Fang, and Jianguang Xie. 2025. "A Boundary-Implicit Constraint Reconstruction Method for Solving the Shallow Water Equations" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 11: 2036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112036

APA StyleWei, D., Yang, J., Fang, M., & Xie, J. (2025). A Boundary-Implicit Constraint Reconstruction Method for Solving the Shallow Water Equations. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(11), 2036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112036