1. Introduction

Coastal debris can occur in all parts of the ocean and, as it moves across national boundaries, has become a global environmental issue with transboundary impacts [

1]. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic and industrial waste, as well as packaging materials and single-use containers, has increased. Meanwhile, recycling rates have stagnated or declined, further accelerating coastal debris generation [

2,

3]. Such debris is readily transported into the marine environment, becoming floating debris or settling as benthic debris, which ultimately causes environmental pollution, ecosystem degradation, and loss of tourism resources. To mitigate these impacts, developing systematic management strategies at the national level is essential. However, developing such strategies requires continuous monitoring of coastal debris generation, together with reliable estimation of total loads, in order to produce reliable statistical data.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA, USA) conducts the Marine Debris Monitoring and Assessment Project (MDMAP), where volunteers and field surveyors periodically select beach transects, collect debris, and record classification information to compile statistical data [

4]. In Europe, the OSPAR beach litter monitoring guidelines require government officials or trained civilian surveyors to classify and record all debris found within a designated 100 m beach section at least four times a year to compile statistical data on coastal debris [

5]. In the Republic of Korea, a non-governmental organization commissioned by the government conducts regular coastal debris surveys every two months, dividing beaches longer than 100 m into 10 m segments and recording the quantity of debris along with photographs to compile statistical data [

6].

However, manpower-based survey methods, even when conducted by trained investigators, are prone to subjective judgment and inconsistent classification, underscoring the need for remote sensing approaches that provide objective and reproducible results. Moreover, such surveys are time-consuming, limiting the efficiency of monitoring. To address the limitations and challenges of conventional monitoring approaches, recent studies have actively explored the use of remote sensing and artificial intelligence for coastal debris monitoring. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) can acquire high-resolution images or videos over large areas within a short period of time. Deep learning-based object detection models, supported by continuous development and performance improvements of open-source frameworks, can maintain high accuracy even when trained with custom datasets. In particular, the integration of UAVs with deep learning-based object detection enables near real-time monitoring. This approach has been applied across various domains, including invasive species detection for environmental management, road crack detection, and rice seedling identification [

7,

8,

9].

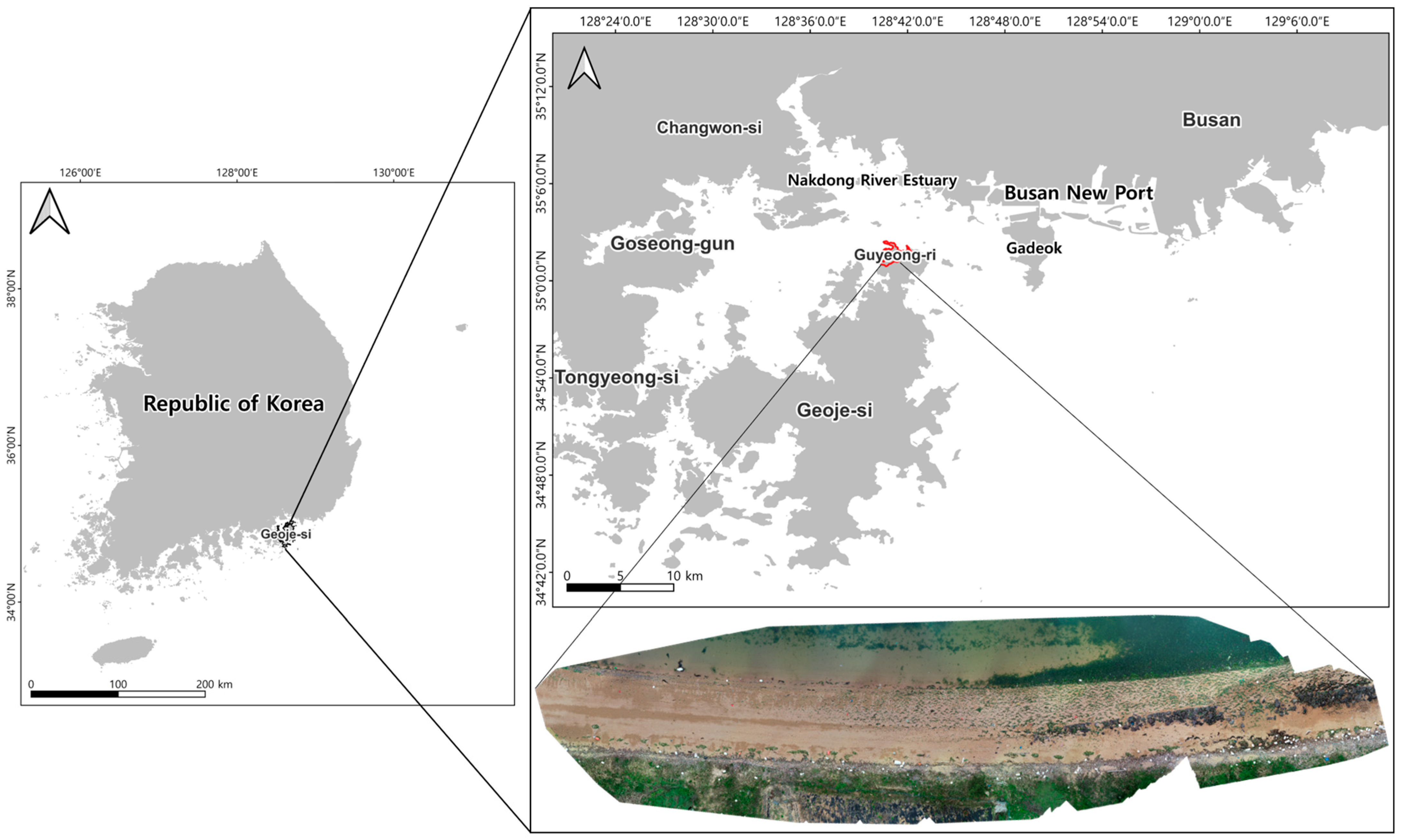

Consistent with prior research utilizing UAVs and object detection models, Kosuke Takaya et al. identified coastal debris in the Seto Inland Sea by applying the RetinaNet model to high-resolution images captured via UAV [

10]. Pfeiffer et al. collected UAV-based coastal debris images along the coasts of Malta, Gozo, and Sicily, detected debris within the images using the YOLOv5 model, and produced coastal debris distribution maps based on location information to facilitate debris monitoring [

11].

Applying deep learning-based object detection models to UAV-acquired images and videos of extensive coastal areas can yield objective and reliable coastal debris statistics within a short time. However, most existing studies have primarily focused on three aspects—(1) quantitative performance evaluation, (2) field applicability assessment, and (3) detection result analysis—without sufficiently addressing how detection performance changes under varying environmental and debris conditions. Moreover, when applied to coastal environments with different characteristics from those of the original study sites, detection performance may degrade, resulting in varying outcomes. Detection performance may also vary depending on the network architecture and training methodology. In particular, the shape and characteristics of objects can further influence detection results. These issues may lead to false positives, a major factor contributing to performance degradation. Ma et al. identified coastal debris using the YOLOv12 model and further evaluated model performance by analyzing bounding box confidence and label accuracy, as well as by estimating the causes of failure or uncertain detection cases [

12]. However, they did not conduct statistical analyses of falsely detected objects or compare their characteristics with those of actual objects.

The objective of this study is to detect coastal debris in UAV-acquired monitoring images using deep learning-based object detection models and to evaluate their accuracy using a novel assessment approach, rather than relying solely on conventional performance metrics. In particular, the analysis focuses on false positives and misclassified objects to calculate detection accuracy for each model, while performance evaluation is conducted based on the causes of false detections.

These results provide field-based performance metrics and model-specific false positive characteristics, enabling a comprehensive quantitative and qualitative evaluation of model performance. Furthermore, by clarifying the impact of architectural differences on detection performance and false positives, this study establishes criteria for selecting models appropriate to coastal environmental conditions and is expected to contribute to the development of efficient coastal debris monitoring systems.

4. Discussion

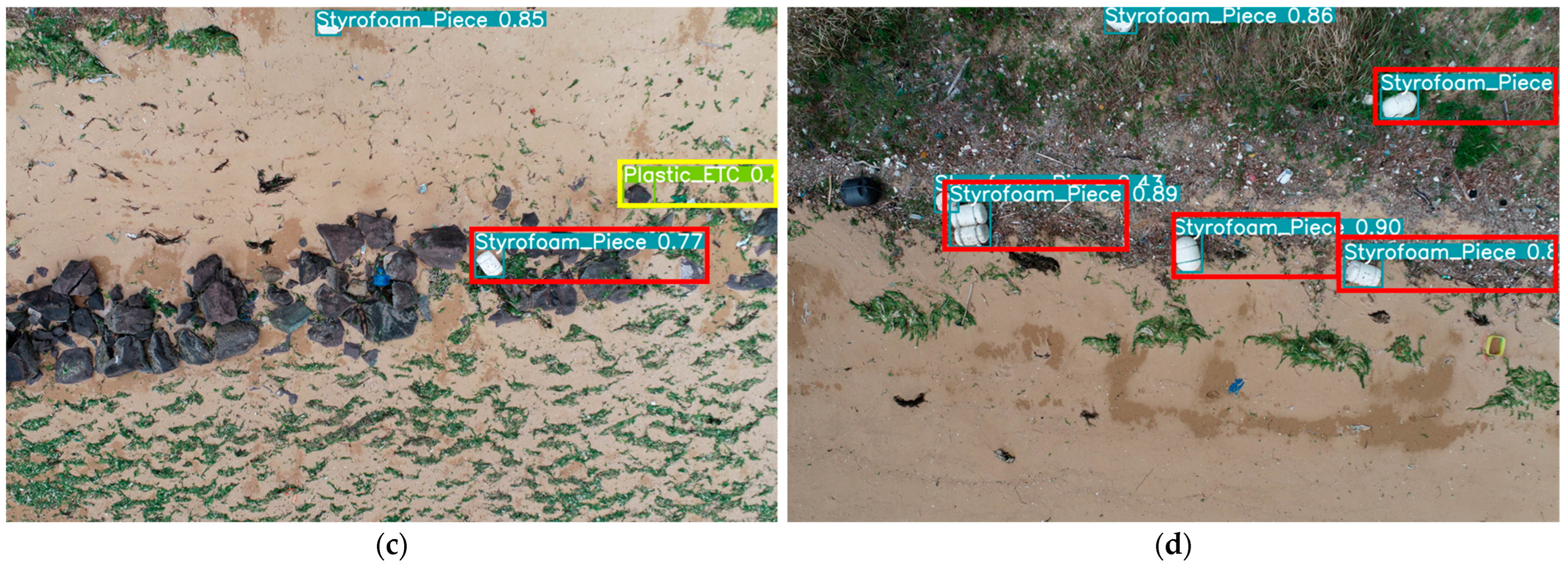

In this study, two deep learning models, RT-DETR and YOLOv10, trained on a publicly available coastal debris dataset, were applied to UAV images collected from an actual beach to analyze false positive cases and their underlying causes under field-based conditions.

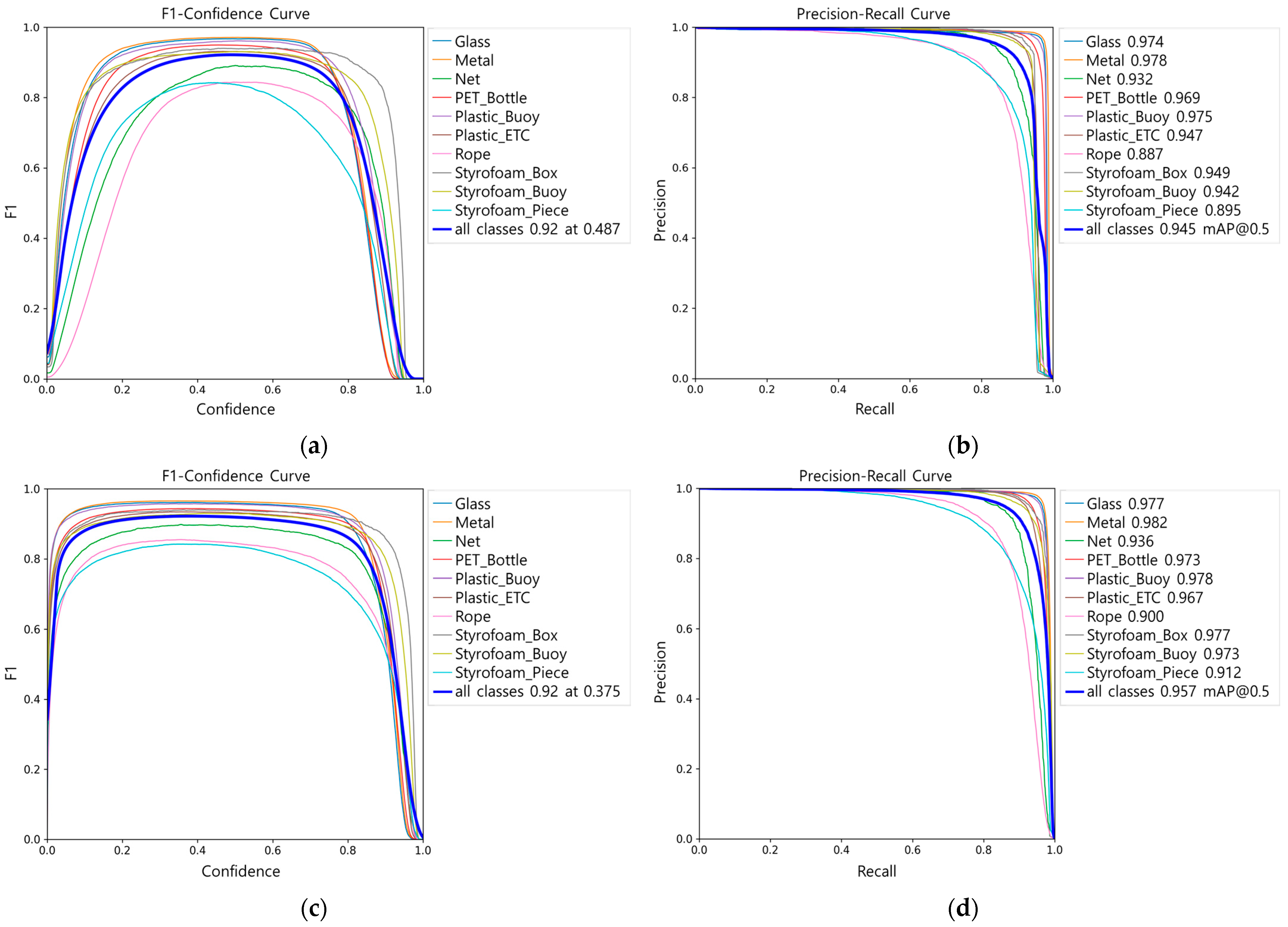

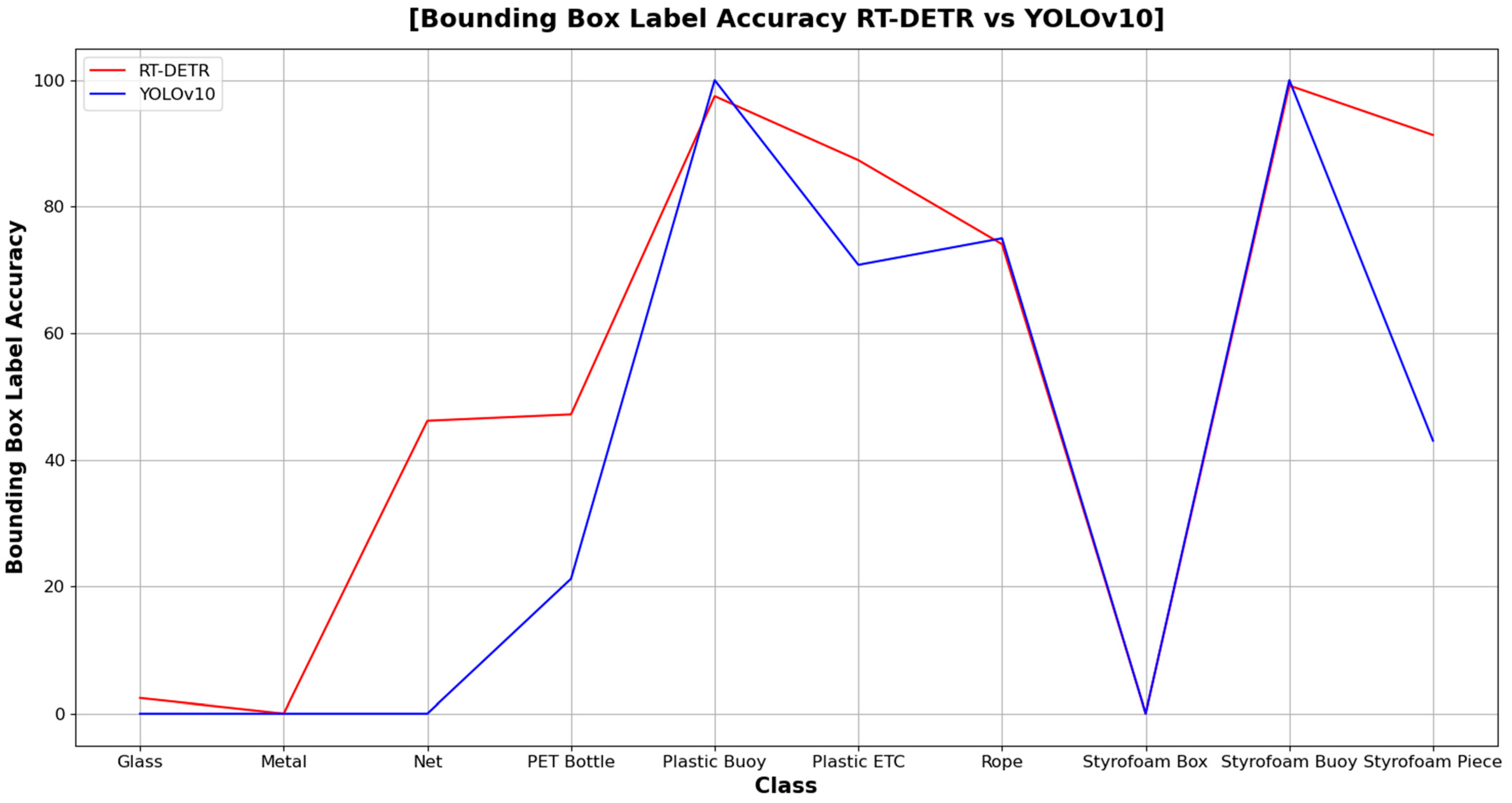

Both models achieved high performance in terms of mAP (0.945 and 0.957, respectively). However, when applied to field data, the bounding box label accuracy (

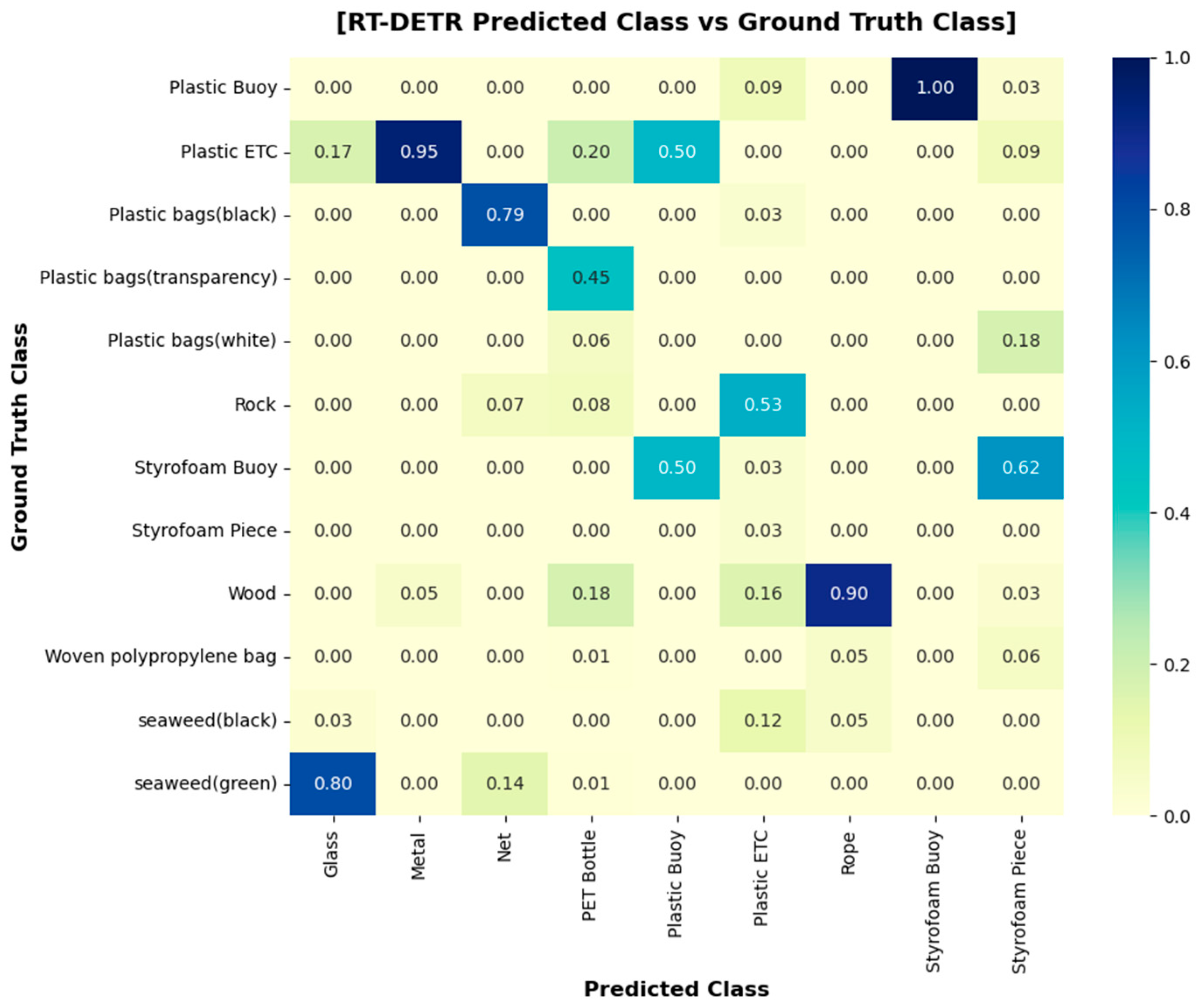

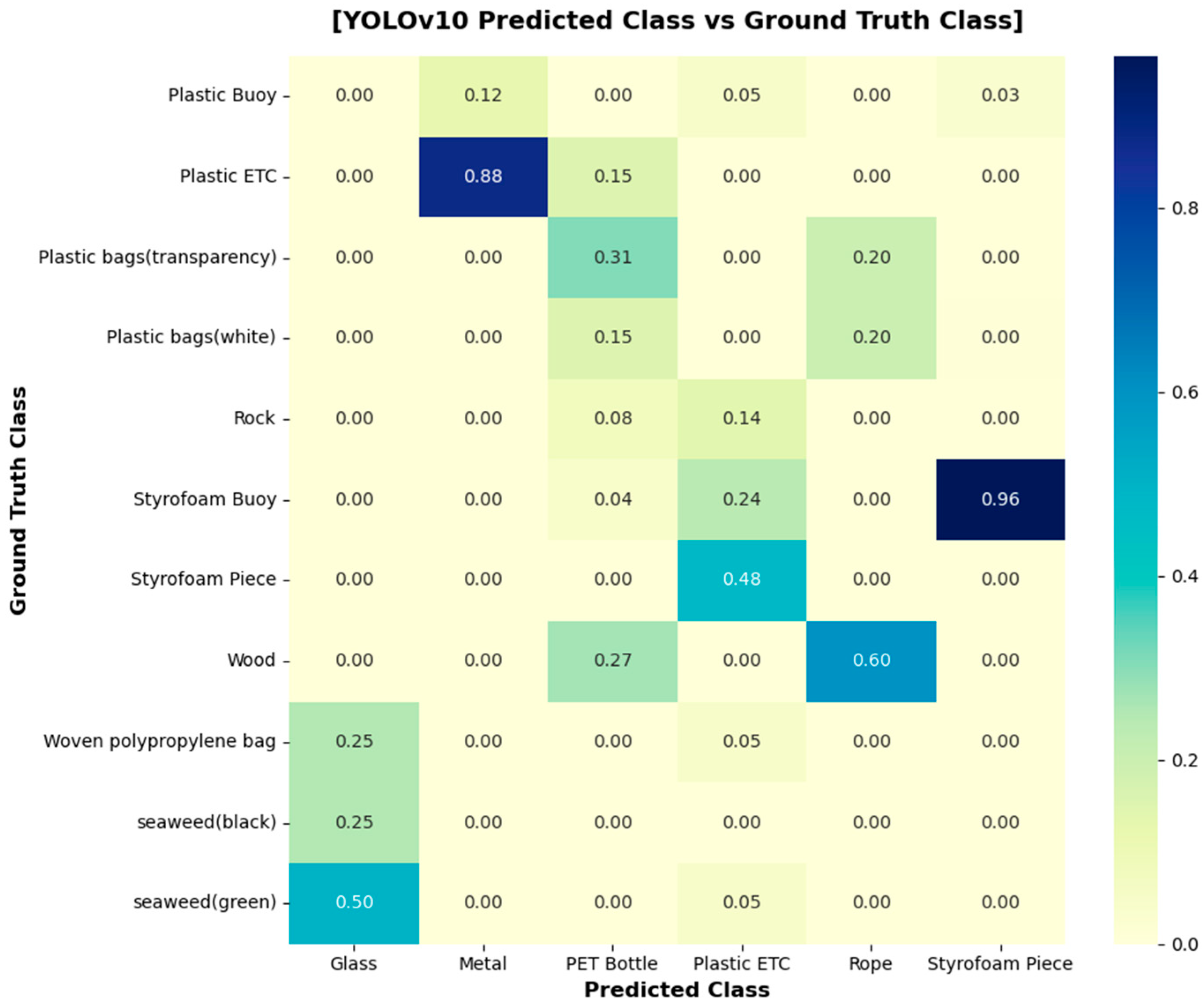

Figure 6) showed similar trends between the two models, except for Styrofoam Piece and Net. In particular, both models exhibited near-zero accuracy for the Metal and Glass classes, making practical identification virtually impossible, whereas buoy-type objects with high structural integrity, such as Styrofoam Buoy and Plastic Buoy, were consistently detected with high accuracy. Nevertheless, overall bounding box label accuracy differed significantly between the two models, with RT-DETR achieving 80.18% and YOLOv10 53.74%. Furthermore, class-specific false positive ratios and the ground truth distributions of misclassified objects revealed clear differences in the false positive tendencies of the two models.

The class-specific false positive analysis showed that 69.38% of false positives in RT-DETR originated from untrained classes, whereas 87.63% of YOLOv10 false positives occurred within trained classes. This indicates that both models were vulnerable to objects with similar material, shape, and color. RT-DETR exhibited a tendency toward overgeneralization by labeling untrained objects as similar classes, while YOLOv10 showed higher intra-class confusion in unstable fragment-type objects. These differences were attributed to their background processing mechanisms.

The Transformer-based RT-DETR detects objects by matching object queries with image features, and unmatched queries are automatically classified as “no object (background)”, allowing the model to learn background representations. This process involves global context integration, enabling the model to comprehensively consider color, shape, and background information across the entire image. By contrast, the CNN-based YOLOv10 employs a dense grid-based one-stage head architecture that directly predicts bounding boxes and class probabilities at each feature map location. During training, only locations spatially close to the ground truth are selected as positive samples, while the rest are excluded, meaning that YOLOv10 does not directly learn background representations. Consequently, RT-DETR assigned labels not only to objects on trained backgrounds (e.g., sand) but also to untrained objects such as wood, seaweed, and rocks, leading to higher false positive ratios in untrained classes. In contrast, YOLOv10 exhibited higher false positive ratios within trained classes, while detections of untrained objects were limited.

In the heat map comparing ground truth and false positives, the most frequent misclassification in RT-DETR was “Unknown Plastic” → “Plastic Bottle” (22.4%), while in YOLOv10 it was “Styrofoam Piece” → “Styrofoam Buoy” (18.7%). The high false positive rate for Styrofoam Piece in YOLOv10 can be explained by the fact that most of its training data consisted of low-altitude images with clearer feature distinctions, whereas in this study the field images were captured at 10 m altitude, making material and feature identification more difficult. Moreover, because the UAV survey was conducted at 14:00 under strong sunlight, specular reflections on Styrofoam surfaces further limited material differentiation and contributed to misclassification. PET Bottles, which showed high false positive rates in both models, were well represented in the training dataset but were mainly trained on intact forms. Thus, damaged PET bottles or other objects with similar shapes and materials were not accurately detected. Metal and Glass had relatively low representation in the training dataset and were primarily trained on intact cans and unbroken green or black bottles, resulting in very low detection accuracy for both models (RT-DETR: 0%, 2.44%; YOLOv10: 0%).

Based on these results, the mismatch between training and field data was found to significantly affect model performance due to (1) dataset bias and (2) differences in object characteristics between training images and field conditions. In the training dataset, class imbalance was evident, with Metal accounting for 16.57% and Glass for 6.9%, and the labeling criteria were narrow, focusing mainly on cans for Metal and on green and black bottles for Glass. In contrast, unmanaged coastal environments are characterized by frequent object damage and occlusion in UAV images, as well as contamination and discoloration that alter visible object properties. Consequently, even with high mAP during training, field applicability becomes substantially limited if class diversity, object shape, distribution, and degradation spectra are not adequately represented. Moreover, this study confirmed the importance of optimizing UAV survey conditions, such as conducting flights after 15:00 when sunlight intensity is reduced, or adjusting camera aperture and brightness settings to minimize the effects of specular reflection. Therefore, mAP alone is insufficient for model comparison, and it is more appropriate to evaluate models in conjunction with class balance, field-specific characteristics, and acquisition conditions.

For UAV-based coastal debris monitoring, this study confirmed that it is not necessary to use UAVs equipped with high-end sensors; UAVs with cameras capable of capturing images at GSD 0.25–0.3 cm/px, such as those used in this study (GSD 0.27 cm/px), are sufficient for field surveys. For the study site, approximately 100 m of coastline was surveyed in 19 min and 41 s. To ensure efficient detection following image acquisition, GPU-based hardware is essential for training on large-scale datasets and for running inference. Even when the lightweight mode was enabled, RT-DETR required approximately 76.8 ms per image, about 4.6 times slower than YOLOv10 (16.7 ms). This result highlights that high-performance GPU hardware enables more efficient detection outcomes. From UAV acquisition to final detection results, the entire process required approximately one day. Although there was no substantial difference in the overall time depending on the model, appropriate model selection and application remain crucial depending on beach characteristics.

In summary, RT-DETR, with its strengths in detecting small fragments, damaged objects, and untrained classes, is more suitable for detailed monitoring and estimation of debris distribution and quantities in unmanaged beaches where high accuracy is required, although it demands higher computational resources and may increase deployment costs. By contrast, YOLOv10, which demonstrated high accuracy for structurally intact objects, is more suitable for rapid large-scale monitoring of managed beaches, owing to its higher computational efficiency and real-time processing capability on lower-spec hardware. Therefore, UAV-based coastal debris monitoring requires consideration not only of model performance but also of UAV operational costs, data processing infrastructure, and real-time field requirements. These findings provide practical guidance for designing coastal debris monitoring systems that balance detection accuracy, cost-efficiency, hardware requirements, and real-time applicability.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the RT-DETR and YOLOv10 models were trained on the same dataset and evaluated on an unmanaged beach. The goal was to quantitatively and qualitatively assess, at the class level, the differences between the standard performance metric (mAP) and the field-based metric (bounding box label accuracy). Although both models achieved similar mAP@0.5 values (0.945 for RT-DETR and 0.957 for YOLOv10), their field accuracies differed significantly, with RT-DETR achieving 80.18% and YOLOv10 53.74%. Both models exhibited near-zero accuracy for the Metal and Glass classes, indicating a failure in detection, whereas they consistently detected buoy-type objects with high structural integrity, such as Styrofoam Buoy and Plastic Buoy. The causes were identified as class imbalance, label bias, and variations in object appearance and visibility due to degradation, occlusion, and optical changes in field conditions. False positive patterns also differed: RT-DETR showed a tendency to overgeneralize untrained objects, while YOLOv10 frequently misclassified fragments and buoys within trained classes.

From these findings, the following practical implications can be drawn. First, model selection should be based not only on mAP but also on field conditions, the priority of the classes to be analyzed, and coastal characteristics. RT-DETR is advantageous for estimating debris loads and conducting large-scale screening in unmanaged beaches where damage and occlusion are frequent, whereas YOLOv10 is more suitable for precise monitoring and detection of specific classes in managed beaches with well-preserved object shapes. Second, to improve detection success rates across all classes, it is essential to ensure quantitative balance in the training dataset and to expand the label spectrum (e.g., color, shape). If this is not feasible, corrective measures such as data augmentation should be applied. Third, model performance should be evaluated by presenting class-specific accuracies together with false positive cause analyses to minimize the risk of overgeneralization in real-world applications.

This study has limitations in that it was conducted at a single beach, with restricted label distribution for certain classes, and lacked three-dimensional information such as object height and volume, which may cause the same type of debris to be perceived differently depending on the shooting angle or shadows. Future research should quantitatively expand the generalizability of the results by improving the quality of training data labels, statistically validating detection performance under various field conditions, and incorporating diverse coastal environmental characteristics. In addition, securing sufficiently balanced training data across classes, improving UAV imaging techniques through the use of multispectral sensors, and employing models that account for 3D object information will help to overcome the limitations of field conditions. By applying field data from diverse coastal areas to construct correction matrices between training and field datasets, it will be possible to estimate the total amount of coastal debris in Korea and establish a standardized coastal debris monitoring system based on statistically validated results.