Microclimate Effects on Quality and Polyphenolic Composition of Once-Neglected Autochthonous Grape Varieties in Mountain Vineyards of Asturias (Northern Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

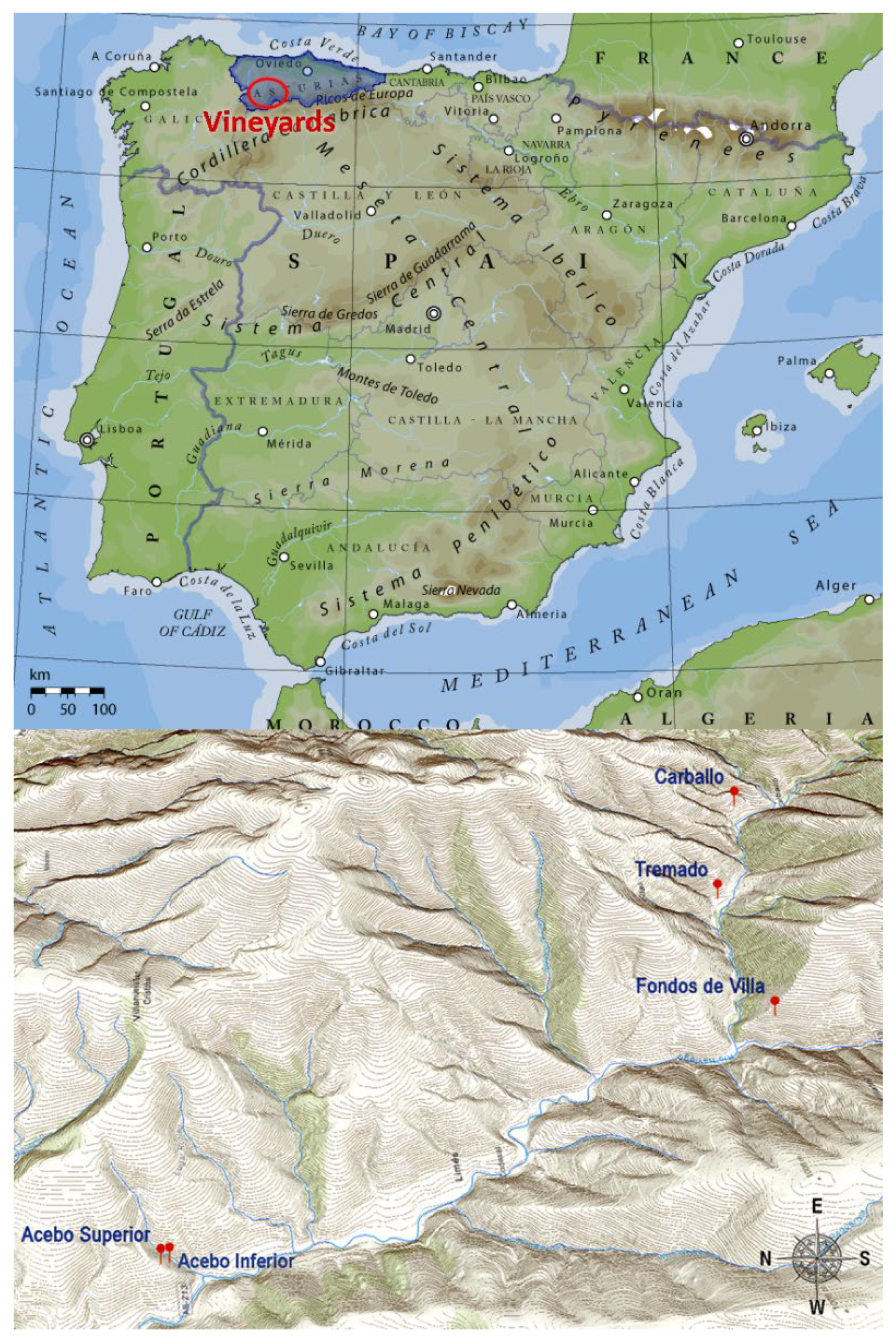

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Meteorological Stations (Condiciones Microclimáticas)

2.3. Plant Material

2.4. Agronomic and Chemical Parameters

2.5. Hplc-Ms and Ms/Ms Polyphenol Analyses

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martínez, M.C.; López Álvarez, J. Asturias entre las regiones pioneras en la modernización de la vitivinicultura española en el siglo XIX. La labor de Anselmo González del Valle, 1878–1901. Sem. Vitivinícola 2015, 3444, 537–542. [Google Scholar]

- Mania, E.; Petrella, F.; Giovannozzi, M.; Piazzi, M.; Wilson, A.; Guidoni, S. Managing. Vineyard Topography and Seasonal Variability to Improve Grape Quality and Vineyard Sustainability. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, C. Topoclimate and wine quality: Results of research on the Gewürztraminer grape variety in South Tyrol, northern Italy. OENO One 2021, 55, 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, G.; Ghanem, C.; Mercenaro, L.; Nassif, N.; Hassoun, G.; Del Caro, A. Effects of altitude on the chemical composition of grapes and wine: A review. OENO One 2022, 56, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canturk, S.; Kunter, B.; Keskin, N.; Kaya, O. Deciphering Terroirs’ Code: Vineyard Site Selection for Phenolic Performance in ‘Kalecik Karası’ Grape Cultivar (V. vinifera L.). Appl. Fruit Sci. 2024, 66, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, C.G.; Febbroni, S. Terroir Traceability in Grapes, Musts and Gewürztraminer Wines from the South Tyrol Wine Region. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Seguin, G. The concept of terroir in viticulture. J. Wine Res. 2006, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolo Lopez, S. Estudio de la Composición Polifenólica de Vinos Tintos Gallegos con D.O: Ribeiro, Valdeorras y Ribeira Sacra; Departamento de Química Analítica, Nutrición y Bromatología, Facultad de Ciencias, Campus de Lugo, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela: Galicia, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gashu, K.; Persi, N.S.; Drori, E.; Harcavi, E.; Agam, N.; Bustan, A.; Fait, A. Temperature shift between vineyards modulates berry phenology and primary metabolism in a varietal collection of wine grapevine. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 588739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, B.; Destrac, A.; Gowdy, M.; Dai, Z.; Van Leeuwen, C. Adapting wine grape ripening to global change requires a multi-trait approach. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 624867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monfort, M.; Gracia, P.; Guasch, E.; López-Vicente, M.; Irigoyen, J.J.; Gogorcena, Y. Aptitud enológica de variedades de vid cultivadas en zonas de montaña. In Reuniones del Grupo de Trabajo de Experimentación en Viticultura y Enología Proceedings of the 34ª Reunión, Centro de Transferencia Agroalimentaria, Gobierno de Aragón, Zaragoza, Spain, 10–11 April 2019; pp. 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzatesta, D.S.; Berli, F.J.; Arancibia, C.; Buscema, F.; Piccoli, P.N. Impact of contrasting soils in a high-altitude vineyard of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Malbec: Root morphology and distribution, vegetative and reproductive expressions, and berry skin phenolics. OENO One 2022, 56, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalakis, I.; Stavrakaki, M.; Vardaka, K.; Nikolaou, S.; Koukoufiki, S.; Giannakou, T.; Bouza, D.; Biniari, K. How Altitude Affects the Phenolic Potential of the Grapes of cv. ‘Fokiano’ (Vitis vinifera L.) on Ikaria Island. Environments 2025, 12, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Iglesias, M.J.; Novio, S.; García, M.C.; Pérez-Muñuzuri, E.; Martínez, M.C.; Santiago, J.L.; Boso, S.; Gago, P.; Freire-Garabal, M. Co-adjuvant therapy efficacy of catechin and procyanidin B2 with docetaxel on hormone-related cancers in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boso, S.; Gago, P.; Santiago, J.L.; Gago, P.; Sotelo, E.; Alvarez-Acero, I.; Martínez, M.C. Flavanol content and nutritional quality of wastes from the making of white and rose wines from mountain vineyards. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2022, 73, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Rakshit, G.; Singh, R.P.; Garse, S.; Khan, J.; Chakraborty, S. Dietary polyphenols: Review on chemistry/sources, bioavailability/metabolism, antioxidant effects, and their role in disease management. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.K.; Parashar, A.K.; Shrivastava, V. A review on exploring the health benefits and antioxidant properties of bioactive polyphenols. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubin, B.C.R.; Inbar, N.; Pinkus, A.; Stanevsky, M.; Cohen, J.; Rahimi, O.; Anker, Y.; Shoseyov, O.; Drori, E. Ecogeographic conditions dramatically affect trans-resveratrol and other major phenolics’ levels in wine at a semi-arid area. Plants 2022, 11, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, T.; Wu, C.; Gongjian, F.; Dandan, Z.; Xiaojing, L. Unlocking the potential of plant polyphenols: Advances in extraction, antibacterial mechanisms, and future applications. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 34, 1235–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhang, N.; Xu, W. Flavonoids as key players in cold tolerance: Molecular insights and applications in horticultural crops. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.C.; Pérez, J.E. The forgotten vineyard of the Asturias Princedom (North of Spain) an ampelographic description of its cultivars (Vitis viinifera L). Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2000, 51, 370–378. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M.C.; Boso, S.; Gago, P.; Alonso-Villaverde, V.; Santiago, J.L. Viticultura de montaña en Asturias. Primeros clones certificados de dos de sus variedades autóctonas. Sem. Vitivinícola 2007, 3197, 3846–3847. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS OnlineDoc, version 9.4; SAS Institute, Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Neethling, E.; Barbeau, G.; Bonnefoy, C.; Quénol, H. Spatial variability of temperature and grapevine phenology at terroir scale in the Loire Valley. OENO One 2020, 54, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, M.C.; Martínez de Toda, F. Variability in the potential effects of climate change on phenology and on grape composition of Tempranillo in three zones of the Rioja DOCa (Spain). Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 115, 126014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, B.I. Phenology and Terroir Heard Through the Grapevine. In Phenology: An Integrative Environmental Science; Schwartz, M.D., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, J.L.; Boso, S.; Vilanova, M.; Martínez, M.C. Characterization of cv. Albarín Blanco (Vitis vinifera L.). Synonyms, Homonyms and errors of identification. J. Int. Sci. Vigne Vin. 2005, 39, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Boso, S.; Cuevas, J.; Gago, P.; Santiago Blanco, J.L.; Martínez, M.C. La viticultura de montaña asturiana y las amenazas del entorno: Proliferación de las poblaciones de jabalíes. Enol. Mod. 2025, 79, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, M.; Torres-Martinez, N. Does UV radiation affect winegrape composition. Acta Hortic. 2004, 640, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berli, F.J.; Alonso, R.; Beltrano, J.; Bottini, R. High-altitude solar UV-B and abscisic acid sprays increase grape berry antioxidant capacity. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2015, 66, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Castillo-Alonso, M.Á.; Monforte, L.; Tomás-Las-Heras, R.; Martínez-Abaigar, J.; Núñez-Olivera, E. To what extent are the effects of UV radiation on grapes conserved in the resulting wines. Plants 2021, 10, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alikadic, A.; Pertot, I.; Eccel, E.; Dolci, C.; Zarbo, C.; Caffarra, A.; De Filippi, R.; Furlanello, C. El impacto del cambio climático en la fenología de la vid y la influencia de la altitud: Un estudio regional. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 271, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellarin, S.D.; Pfeiffer, A.; Sivilotti, P.; Degan, M.; Peterlunger, E.; Di Gaspero, G. Transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in ripening fruit of grapevine under seasonal water deficit. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 1381–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Song, C.; Falginella, L.; Castellarin, S.D. Day temperature has a stronger effect than night temperature on anthocyanin and flavonol accumulation in ‘Merlot’ (Vitis vinifera L.) grapes during ripening. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Vuelta, A. Análisis de la Influencia de la Altitud del Viñedo Sobre los Parámetros de Maduración de la uva en la “D.O. Bierzo.” Trabajo de Fin de Grado. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de La Rioja, Logroño, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brighenti, A.F.; Silva, A.L.; Brighenti, E.; Porro, D.; Stefanini, M. Viticultural performance of native Italian varieties in high-altitude conditions in Southern Brazil. Pesqui. Agropecuár. Bras. 2014, 49, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boso, S.; Gago, P.; Santiago, J.L.; Gago, P.; Sotelo, E.; Alvarez-Acero, I.; Martínez, M.C. New monovarietal grape seed oils derived from white grape bagasse generated on an industrial scale at a winemaking plant. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 92, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plots | Altitude (m) | Orientation | Topography | Albarín Blanco Clone | Verdejo Negro Clone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acebo Superior | 495 | South-Southeast | Flat | 20 | 20 |

| Acebo Inferior | 475 | South-Southeast | Steep slope | 20 | |

| Carballo | 529 | Southwest | Steep slope | 20 | 20 |

| Fondos de Villa | 548 | West | Flat | 20 | |

| Tremado | 473 | Southwest | Gentle slope | 20 | 20 |

| Soil Parameter/Plot | Acebo Superior (Albarín Blanco, Verdejo Negro) | Acebo Inferior (Verdejo Negro) | Carballo (Albarín Blanco) | Carballo (Verdejo Negro) | Fondos de Villa (Albarín Blanco) | Tremado (Albarín Blanco, Verdejo Negro) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil chemicals | ||||||

| pH H2O (1:2.5) | 4.6 | 4.4 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 5.5 |

| pH KCl (1:2.5) | 3.5 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 4.4 |

| Organic matter (%) | 2.8 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 6.8 | 3.5 |

| Exchange acidity (cmol(+) kg−1) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Available phosphorus (ppm) | 28 | 96 | 44 | 68 | 72 | 87 |

| Assimilable potassium (ppm) | 94 | 122 | 186 | 376 | 632 | 288 |

| Exchangeable magnesium | 20 | 10 | 46 | 280 | 140 | 86 |

| Ca/Mg | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 17 | 9 |

| K/Mg | 1.5 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| Ca:Mg:K | 43:23:34 | 34:14:52 | 73:12:15 | 70:21:09 | 87:05:07 | 81:09:10 |

| Granulometric analysis | ||||||

| CG * (%) 2–0.2 mm | 21.28 | 22.75 | 34.94 | 32.75 | 35.58 | 28.01 |

| FS (%) 0.2–0.05 mm | 16.79 | 14.93 | 15.35 | 14.98 | 11.76 | 14.47 |

| CSi (%) 0.05–0.02 mm | 8.29 | 7.64 | 6.32 | 7.69 | 5.59 | 7.66 |

| FSi (%) 0.02–0.002 mm | 34.43 | 30.86 | 22.31 | 21.08 | 29.28 | 28.85 |

| Clay (%) < 0.002 mm | 19.21 | 23.82 | 21.08 | 20.99 | 17.79 | 21.01 |

| Sand (%) 2–0.05 mm | 38.07 | 37.68 | 50.28 | 47.72 | 47.34 | 42.27 |

| Silt (%) 0.05–0.002 mm | 42.72 | 38.50 | 28.63 | 31.29 | 34.87 | 36.51 |

| Texture | Loam | Loam | Loam | Loam | Loam | Loam |

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plots | Kg of Grape/ Vine n = 20 | Total Number of Clusters/Vine n = 20 | Cluster Weight (g) n = 10 | Berry Weight (g) n = 30 | Kg of Grape/ Vine n = 20 | Total Number of Clusters/Vine n = 20 | Cluster Weight (g) n = 10 | Berry Weight (g) n = 30 | Kg of Grape/Vine n = 20 | Total Number of Clusters/Vine n = 20 | Cluster Weight (g) n = 10 | Berry Weight (g) n = 30 | |

| VERDEJO NEGRO | Acebo Inferior | 0.87 c * | 14.15 b | 118.87 b | 1.65 c | 0.17 c | 8.75 c | 56.29 b | 1.87 c | 0.48 b | 11.15 c | 120.08 b | 2 b |

| Acebo Superior | 2.27 b | 16.83 b | 196.03 a | 2.05 b | 0.42 c | 19.77 a | 93.33 b | 2.23 b | 1.3 b | 19.31 b | 150.47 ab | 2.35 a | |

| Carballo | 4.02 a | 27.32 a | 228.18 a | 2.47 a | 1.19 b | 14.42 b | 148.17 a | 2.38 b | 2.94 a | 24.94 a | 180.45 a | 2.15 ab | |

| Tremado | 0.67 c | 5.45 c | 176.09 a | 2.25 ab | 1.69 a | 13.8 b | 179.74 a | 2.64 a | 0.8 b | 9.52 c | 145.12 ab | 2.22 ab | |

| LSD (0.05) | 0.86 | 5.74 | 52.51 | 0.26 | 0.40 | 4.42 | 39.78 | 0.24 | 0.84 | 4.83 | 38.89 | 0.22 | |

| ALBARÍN BLANCO | Acebo Superior | 1.95 a | 17.2 a | 110.09 b | 2.16 a | 0.22 c | 10.9 b | 62.74 b | 1.8 c | 0.92 a | 16.05 a | 159.99 a | 2.08 b |

| Carballo | 0.8 b | 8.25 b | 154.16 ab | 1.94 a | 0.54 b | 7.89 a | 65.74 b | 2 b | 0.51 b | 9.65 c | 121.1 b | 2.5 a | |

| Fondos de Villa | . | . | . | . | 0.35 c | 7.6 b | 185.31 a | 1.92 bc | 0.21 c | 7.05 b | 90.6 c | 2.38 a | |

| Tremado | 1.11 b | 6.7 b | 174.84 a | 2.19 a | 1.17 a | 10.7 ab | 201.69 a | 2.45 a | 0.42 b | 7.1 c | 134.32 ab | 2.34 a | |

| LSD (0.05) * | 0.54 | 3.93 | 60.14 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 3.50 | 51.16 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 3.49 | 29.33 | 0.21 | |

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vineyard | Potential Alcohol (°Baume) n = 10 | Total Acidity (g/L Tartaric Acid) n = 10 | pH n = 10 | Juice Yield (%) n = 10 | Potential Alcohol (°Baume) n = 10 | Total Acidity (g/L Tartaric Acid) n = 10 | pH n = 10 | Juice Yield (%) n = 10 | Potential Alcohol (°Baume) n = 10 | Total Acidity (g/L Tartaric Acid) n = 10 | pH n = 10 | Juice Yield (%) n = 10 | |

| VERDEJO NEGRO | Acebo Inferior | 12.28 a * | 5.12 c | 3.18 c | 28.63 bc | 15.42 a | 8.77 a | 3.41 a | 27.08 ab | 14.14 a | 5.19 b | 3.23 b | 41.32 b |

| Acebo Superior | 10.56 c | 6.36 b | 3.07 d | 33.24 a | 13.79 ab | 7.33 b | 3.39 ab | 31.68 a | 12.05 c | 4.79 c | 3.13 c | 46.12 a | |

| Carballo | 10.54 c | 6.77 a | 3.23 b | 24.63 c | 13.41 abc | 6.61 c | 3.34 c | 23.16 b | 12.73 b | 6.30 a | 3.21 bc | 35.07 cd | |

| Tremado | 11.48 b | 6.43 ab | 3.3 a | 32.76 ab | 11.27 c | 6.49 c | 3.64 bc | 31.68 a | 14.24 a | 4.35 d | 3.41 a | 32.65 d | |

| LSD (0.05) | 0.70 | 0.36 | 0.03 | 4.37 | 2.43 | 0.36 | 0.03 | 5.56 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.03 | 2.96 | |

| ALBARÍN BLANCO | Acebo Superior | 11.38 b | 6.25 c | 3.11 b | 34.64 b | 14.06 d | 7.11 ab | 3.24 a | 36.22 d | 12.28 b | 8.28 c | 3.00 d | 54.17 a |

| Carballo | 12.18 a | 7.45 b | 3.25 a | 32.48 b | 11.63 c | 9.56 a | 3.36 b | 29.51 b | 13.35 a | 9.02 b | 3.15 b | 41.25 c | |

| Fondos de Villa | . | . | . | . | 9.54 a | 13.07 b | 3.18 a | 35.39 a | 12.96 b | 10.69 a | 3.08 c | 43.51 b | |

| Tremado | 10.28 c | 9.74 a | 3.03 c | 38.64 a | 11.99 c | 8.62 ab | 3.22 c | 24.52 | 12.98 b | 8.25 c | 3.23 a | 41.17 c | |

| LSD (0.05) | 0.73 | 0.98 | 0.07 | 2.19 | 0.57 | 0.14 | 3.53 | 0.57 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 2.83 | |

| Plots | Total Anthocyanins (ng/mL) n = 5 | Total Flavonols (ng/mL) n = 5 | Total Phenolics (ng/mL) n = 5 | Total Hydrocarbons (ng/mL) n = 5 | Total Polyphenols (ng/mL) n = 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VERDEJO NEGRO | 2017 | Acebo Inferior | 4762.49 a * | 1440.67 a | 4020.01 ab | 0 | 10,223.18 a |

| Acebo Superior | 256.02 b | 289.2 bc | 4854.77 ab | 0 | 5400.00 b | ||

| Carballo | 120.00 b | 129.52 c | 3192.53 b | 0 | 3442.05 b | ||

| Tremado | 110.00 b | 456.97 b | 5101.82 a | 0 | 5668.8 b | ||

| LSD (0.05) * | 1662.60 | 232.21 | 2645.50 | 0.00 | 3689.90 | ||

| 2018 | Acebo Inferior | 2229.02 ab | 1075.57 a | 3744.36 a | 0.00 b | 7705.32 ab | |

| Acebo Superior | 1692.54 b | 1017.02 a | 3266.56 a | 0.00 b | 6405.00 ab | ||

| Carballo | 25,903.19 a | 531.02 b | 2807.9 ab | 211.63 a | 29,613.16 a | ||

| Tremado | 675.88 b | 253.84 b | 1545.1 b | 0.00 b | 2474.83 b | ||

| LSD (0.05) | 24,174.00 | 458.32 | 1718.30 | 208.55 | 23,217.00 | ||

| 2019 | Acebo Inferior | 308.79 a | 585.44 a | 5589.79 a | 0.00 a | 6484.03 a | |

| Acebo Superior | ND | 225.93 b | 5916.88 a | 0.00 a | 6142.81 a | ||

| Carballo | 4782.61 a | 244.42 b | 6640.06 a | 14.57 a | 11,681.66 a | ||

| Tremado | 141.51 a | 304.55 b | 6269.57 a | 0.00 a | 6715.63 a | ||

| LSD (0.05) | 126,302.00 | 122.90 | 1711.00 | 114.94 | 33,510.00 | ||

| ALBARÍN BLANCO | 2017 | Acebo Superior | 0 | 470.87 a | 5638.14 a | 0 | 6109.01 a |

| Carballo | 0 | 461.53 a | 8708.7 a | 0 | 9170.23 a | ||

| Fondos de Villa | 0 | . | . | . | . | ||

| Tremado | 0 | 195.44 b | 6550.42 a | 0 | 6745.87 a | ||

| LSD (0.05) | 0 | 221.57 | 4254.50 | 0.00 | 4226.10 | ||

| 2018 | Acebo Superior | 0 | 612.66 a | 24,706.33 a | 152.37 a | 25,471.36 a | |

| Carballo | 0 | 112.71 b | 5479.40 b | 31.24 b | 5623.34 b | ||

| Fondos de Villa | 0 | 128.05 b | 7745.62 b | 0.00 b | 7873.67 b | ||

| Tremado | 0 | 248.31 b | 14,382.63 ab | 0.00 b | 14,630.94 ab | ||

| LSD (0.05) | 0 | 224.78 | 10,865.00 | 121.06 | 10,938.00 | ||

| 2019 | Acebo Superior | 0 | 327.92 ab | 3079.92 a | 157.39 a | 3565.23 a | |

| Carballo | 0 | 397.81 a | 3884.60 a | 155.95 a | 4438.36 a | ||

| Fondos de Villa | 0 | 39.08 b | 1618.97 a | 22.73 a | 1680.78 a | ||

| Tremado | 0 | 37.40 b | 1898.02 a | 53.76 a | 1989.19 a | ||

| LSD (0.05) | 0 | 299.38 | 3001.80 | 199.72 | 3165.00 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Boso, S.; Cuevas, J.-I.; Santiago, J.-L.; Gago, P.; Martínez, M.-C. Microclimate Effects on Quality and Polyphenolic Composition of Once-Neglected Autochthonous Grape Varieties in Mountain Vineyards of Asturias (Northern Spain). Agriculture 2026, 16, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020285

Boso S, Cuevas J-I, Santiago J-L, Gago P, Martínez M-C. Microclimate Effects on Quality and Polyphenolic Composition of Once-Neglected Autochthonous Grape Varieties in Mountain Vineyards of Asturias (Northern Spain). Agriculture. 2026; 16(2):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020285

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoso, Susana, José-Ignacio Cuevas, José-Luis Santiago, Pilar Gago, and María-Carmen Martínez. 2026. "Microclimate Effects on Quality and Polyphenolic Composition of Once-Neglected Autochthonous Grape Varieties in Mountain Vineyards of Asturias (Northern Spain)" Agriculture 16, no. 2: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020285

APA StyleBoso, S., Cuevas, J.-I., Santiago, J.-L., Gago, P., & Martínez, M.-C. (2026). Microclimate Effects on Quality and Polyphenolic Composition of Once-Neglected Autochthonous Grape Varieties in Mountain Vineyards of Asturias (Northern Spain). Agriculture, 16(2), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020285