1. Introduction

Sheep are a major livestock species worldwide. Body measurements—including body length, body height, and chest circumference—are key indicators of growth, health, and production performance. These traits influence reproductive efficiency, meat quality, and economic returns in sheep production [

1]. Accurate and efficient body measurement is fundamental for optimizing management, stabilizing livestock supply, and supporting breeding, disease monitoring, and precision livestock farming. It is a core enabling technology for modernizing and digitizing the livestock industry [

2,

3].

Traditional sheep body measurement relies on manual procedures, requiring trained personnel to physically contact animals using tools such as tape measures. This approach is time-consuming, labor-intensive, subjective, and can induce stress in animals. Accuracy is strongly influenced by operator experience and animal posture, limiting scalability in large production systems. With advances in computer vision and deep learning, non-contact measurement has become a major research focus because it is stress-free, efficient, and highly repeatable [

4,

5,

6]. Recent machine-vision studies in large livestock have focused on improving measurement speed, accuracy, and device portability, providing a foundation for sheep-oriented systems [

7,

8,

9,

10]. For non-contact sheep measurement, Zhang et al. proposed an image-analysis-based estimation algorithm using RGB images, establishing an early technical basis for this field [

11]. Zhang et al. further developed and validated an image-based method, improving automation and repeatability by optimizing feature extraction and parameter computation; over 90% of measurements had errors below 3% [

12]. Beyond sheep, Li et al. proposed a beef-cattle pipeline integrating YOLOv5s-based detection, Lite-HRNet-based keypoint extraction, and a Global–Local Path network for monocular depth estimation. Their approach achieved mean relative errors of 6.75–8.97% for traits such as withers height and body length at 1–5 m under multiple lighting conditions, providing a useful reference for sheep measurement system design [

13,

14]. For pigs, Shuai et al. proposed a multi-view RGB-D reconstruction and measurement method, achieving mean relative errors of 2.97% (body length), 3.35% (body height), 4.13% (width), and 4.67% (chest circumference), highlighting the effectiveness of point-cloud-based measurement pipelines [

15].

Despite substantial progress, current body-measurement methods still have important limitations. Two-dimensional methods rely on a single view, cannot directly recover 3D morphology, and are sensitive to background clutter, illumination changes, and pose variation, which limits accuracy and completeness [

16,

17]. To improve accuracy and robustness, Hu et al. enhanced PointNet++ with multi-view RGB-D data for automated pig measurement and achieved strong performance in point-cloud segmentation and keypoint localization [

18].Hao et al. developed LSSA_CAU, an interactive 3D point-cloud analysis tool that improves reliability under occlusion and pose variation via human–computer interaction [

19]. However, conventional 3D pipelines often incur high computational cost, require specialized equipment, and adapt poorly to occlusion and large pose variation, limiting deployment in real farm environments [

20].

Recently, foundation models such as the Segment Anything Model (SAM) and Grounding DINO have shown strong generalization in segmentation and detection. Hybrid CNN–Transformer architectures and self-supervised pretraining have also become mainstream in generic detection and instance segmentation. However, deploying these large-scale models in precision livestock farming remains challenging: (i) their compute and memory demands often exceed the capabilities of low-cost edge devices; (ii) domain shifts due to wool texture, illumination, and background clutter can substantially degrade out-of-the-box performance without adaptation; and (iii) few studies tailor these models to slender, morphologically constrained targets such as livestock body regions used for measurement. In contrast, we develop a task-specific, lightweight architecture that is deployable on farm hardware and includes targeted enhancements for elongated regions and 3D measurement. To address these challenges, we propose a non-contact sheep body-measurement method that integrates an enhanced YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM instance-segmentation model with 3D point-cloud processing. The method improves feature extraction and box regression and combines these enhancements with depth completion and point-cloud preprocessing to enable accurate estimation of body length, body height, and chest circumference. Without physical contact, the pipeline balances accuracy and real-time performance and is suitable for complex farm environments, providing a practical solution for precision management in large-scale sheep farms. We formulated the following hypotheses:

H1. Incorporating the SegLinearSimAM module improves segmentation and detection of elongated regions (body length and body height) relative to the baseline YOLOv12n-Seg.

H2. The ENMPDIoU loss improves bounding-box localization for slender targets by explicitly modeling aspect ratio and directional consistency.

H3. Integrating YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM with 3D point-cloud geometric fitting enables non-contact measurement of sheep body dimensions with mean relative errors below 5% under farm conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

The experiment was conducted at the Animal Science Experimental Station of Shanxi Agricultural University (Taigu District, Jinzhong City, China) and involved 43 Hu sheep aged 12–18 months. Data were collected from March to September 2025. To simultaneously meet the requirements of deep learning model training and three-dimensional body measurement, two types of equipment were used: a Canon EOS 70D camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and an Intel RealSense D435i depth camera (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

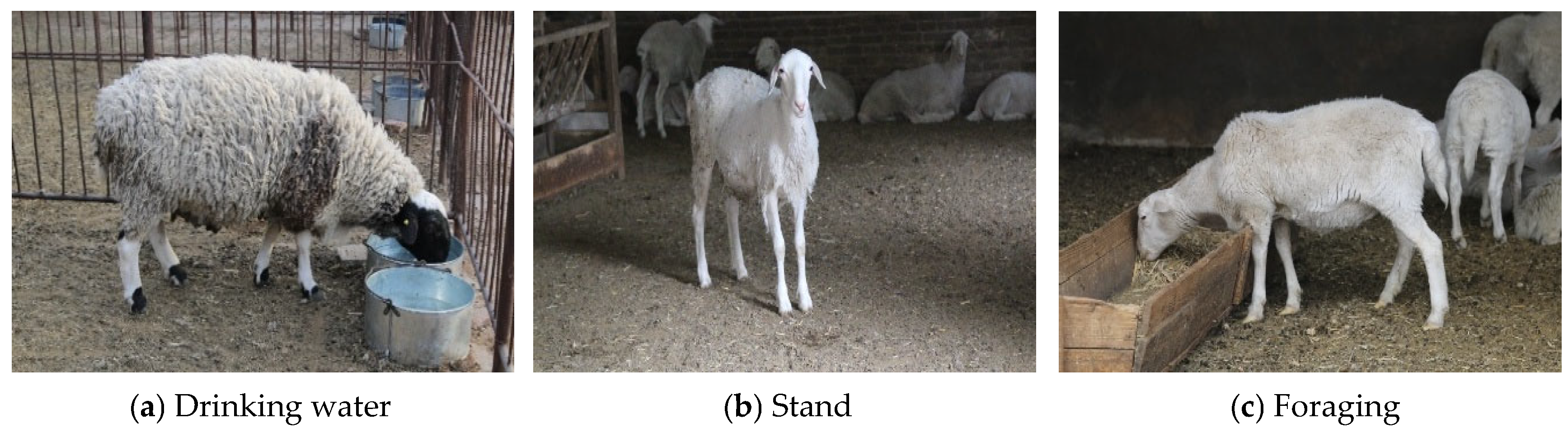

In the first acquisition phase, the Canon EOS 70D was used to capture high-resolution RGB images for training and evaluating the YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM detection–segmentation model. A total of 1714 images were collected, covering a variety of postures and viewing angles, including drinking (

Figure 1a), standing (

Figure 1b), and feeding (

Figure 1c). These images formed the RGB dataset for the segmentation task. The dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test subsets in a 7:2:1 ratio at the animal level, such that all images belonging to the same sheep were assigned to only one subset. During model development, the training set was used to optimize the network parameters, the validation set was used exclusively for hyperparameter tuning and model selection, and the held-out test set was reserved for the final performance assessment. This animal-level splitting protocol prevents the same individual from appearing in multiple subsets and thus effectively mitigates the risk of data leakage and overly optimistic performance estimates. In a separate acquisition phase, RGB-D data were collected for 3D point-cloud reconstruction and body-dimension measurement. These RGB-D samples were used exclusively for downstream measurement evaluation and were not involved in model training, validation, hyperparameter tuning, or threshold selection.

In the second phase, an Intel RealSense D435i depth camera was used to capture RGB-D data and generate point clouds. A total of 129 sets of frontal and lateral samples were collected from 43 sheep, with the camera positioned approximately 1.5 m from each animal. The camera was configured with a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels. Each sample set comprised an RGB image, a depth image, and a 3D point cloud of the sheep. The D435i was selected for its ability to simultaneously output RGB and depth streams while generating dense point clouds in real time. This configuration facilitates precise mapping of pixel-level segmentation masks onto 3D space, enabling automated measurement of geometric parameters such as body length, body height, and chest circumference, and improving measurement repeatability.

It is important to note that the RGB-D samples collected with the RealSense D435i were not used for training or tuning the YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM model. The detection–segmentation network was trained solely on the Canon RGB dataset, and the trained model was then directly applied to the RGB-D measurement dataset in a cross-device setting to generate segmentation masks and guide the 3D body measurement pipeline. Under this protocol, no RGB-D data from the measurement dataset leak into the model-training process, and no identical images are shared between the training and evaluation stages.

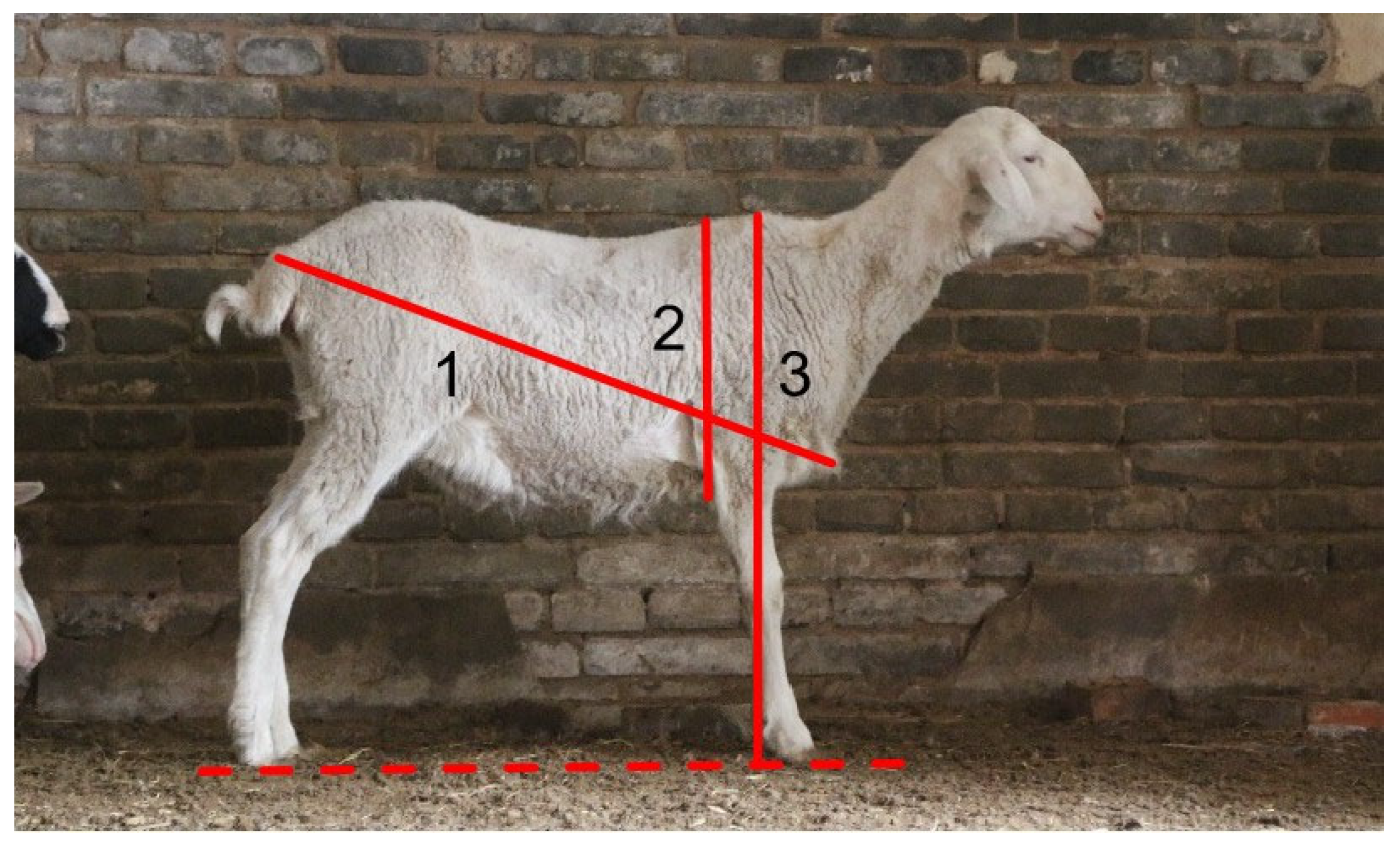

To evaluate the performance of the sheep body measurement system, each sheep was positioned in a standard standing posture on level ground under the guidance of farm staff. One person stabilized the sheep to ensure standard alignment, while another used a tape measure to take three repeated measurements of body length, body height, and chest circumference, and the average values were taken as the reference body measurements. The measured body parameters are shown in

Figure 2, and the measurement standards are detailed in

Table 1.

In-camera depth calibration and RGB–depth alignment were performed on the RGB-D data, and point clouds were then reconstructed from the depth maps for subsequent processing.

2.2. Image Data Preprocessing

After data collection, all raw images underwent quality control and unified preprocessing. Images that were out of focus, severely motion-blurred, overexposed, or underexposed were removed to ensure that only visually reliable samples were retained for annotation and training. To maintain consistency across experiments, the remaining images were resized to 640 × 640 pixels and normalized before being fed into the network, matching the model’s input specification.

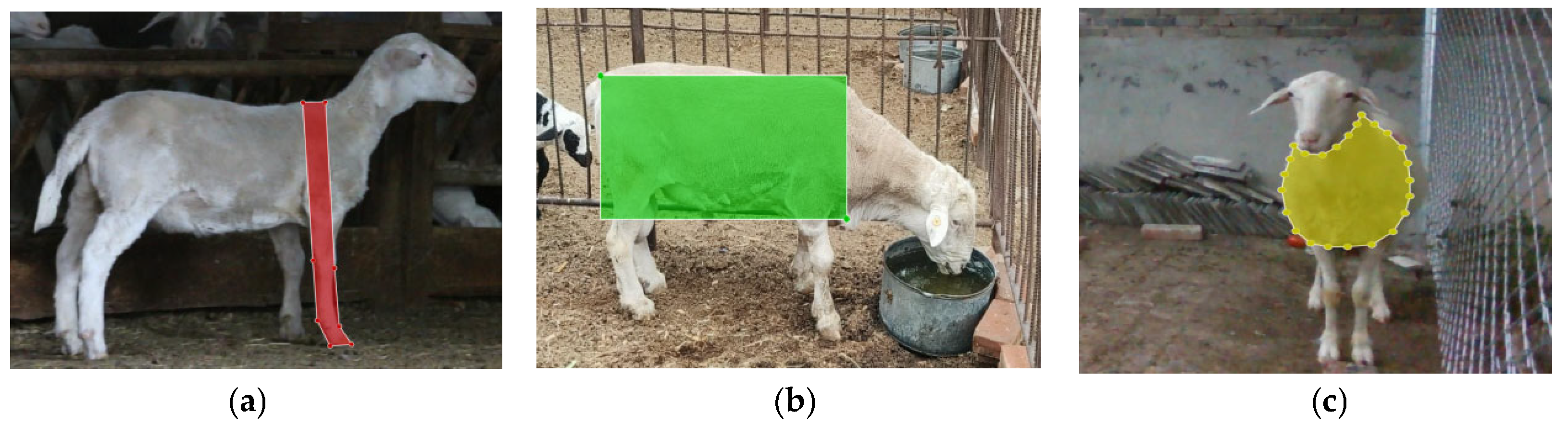

Given the differences in resolution, field of view, and colour reproduction between the Canon EOS 70D and the Intel RealSense D435i, online data augmentation was employed during training to simulate diverse imaging conditions. Geometric and photometric transformations were applied on the fly, which effectively increased the variability of the training samples without changing the underlying dataset size. This strategy enhances the model’s adaptability to cross-device variations and environmental changes (e.g., illumination and background clutter), thereby mitigating potential domain shift between the Canon RGB training images and the RealSense RGB-D measurement data. Manual annotation of the sheep images used to train the detection–segmentation model was performed using the LabelMe [

21]. Three body measurement regions were delineated: body length (

Figure 3a), body height (

Figure 3b), and chest circumference (

Figure 3c). These were assigned the class labels “body_length”, “body_height”, and “chest_circumference”, respectively, ensuring consistent terminology throughout the dataset and the network outputs. In total, the annotated instances comprised 1006 images for the “body_length” class, 1015 images for the “body_height” class, and 735 images for the “chest_circumference” class. The annotation results were saved as JSON files and subsequently converted into YOLO-compatible TXT files, which were then used to support model training, validation, and testing under the animal-level data partitioning strategy described in

Section 2.1.

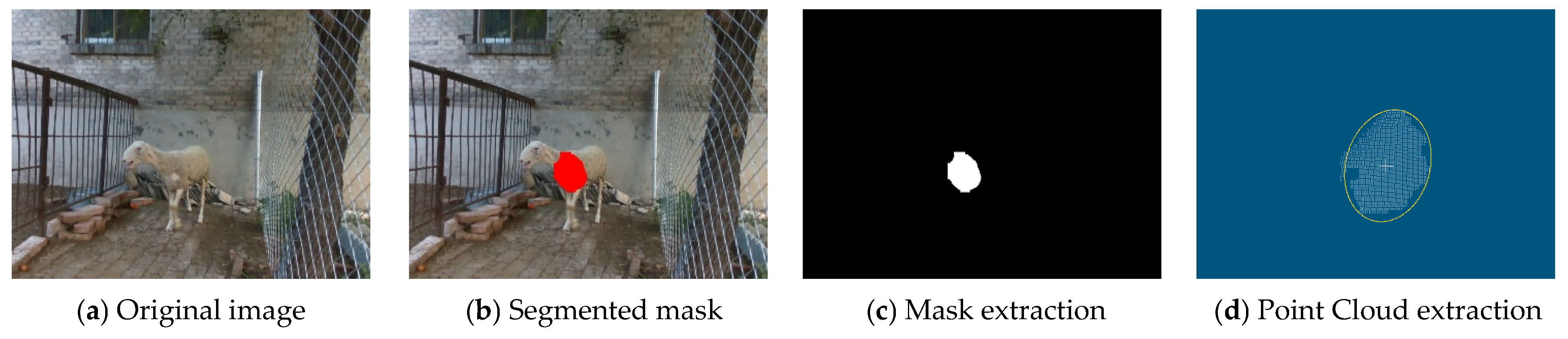

2.3. Overview of the Proposed 2D–3D Measurement Pipeline

This section provides an end-to-end overview of the proposed non-contact sheep body-dimension measurement method, which integrates an improved instance-segmentation model with RGB-D point-cloud reconstruction and geometric fitting. The pipeline takes a single RGB image and its aligned depth map as input and outputs three key body dimensions: body length, body height, and chest circumference.

First, the improved YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM model performs instance segmentation to obtain region masks corresponding to the target body dimensions. To improve boundary stability in complex farm environments, the predicted masks are refined using lightweight morphological operations (e.g., hole filling and boundary smoothing). Second, depth completion and validity filtering are applied to mitigate missing or noisy depth values caused by occlusion, illumination changes, and wool texture. The refined masks are used to select valid depth pixels, which are then back-projected into three-dimensional space using the calibrated camera intrinsics, thereby generating a masked point cloud that represents the sheep body surface.

Finally, each body dimension is estimated using trait-specific geometric fitting on the filtered point cloud. Body height is computed relative to an estimated ground reference plane to provide a stable vertical baseline and reduce sensitivity to variation in scanning height. Body length is obtained by estimating a dominant body axis under geometric constraints and computing the endpoint distance along this principal direction. Chest circumference is estimated by extracting a stable thorax cross-section, performing robust ellipse fitting, and computing circumference using an ellipse perimeter approximation. Throughout the pipeline, point-cloud preprocessing operations—including depth-range filtering, downsampling, and outlier removal—are used to improve geometric consistency and reduce fitting instability. If the number of valid points is below a minimum threshold, the measurement is discarded to avoid unstable fitting. The overall workflow is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. End-to-end workflow of the proposed non-contact sheep body-dimension measurement pipeline. |

| Input | RGB image I; aligned depth map D; camera intrinsics K = (fx, fy, cx, cy); trained YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM model M; target body dimension d ∈ {body length, body height, chest circumference}; hyperparameters Θ; optional external mask m. |

| Output | Predicted measurement ŷ_d (cm) and diagnostic information Q (e.g., number of valid points, fitting status). |

| 1 | Acquire data: obtain I and aligned D from an RGB-D sensor. |

| 2 | If m is not provided, perform instance segmentation to obtain the dimension-specific region mask. |

| 3 | m ← InstanceSegmentation(M, I; conf_th). |

| 4 | m ← MaskRefinement(m; morphology, hole filling) to suppress boundary noise. |

| 5 | ← DepthCompletion(D; Θ) (optional) to mitigate missing/noisy depth. |

| 6 | P ← BackProjection(, m, K) to back-project masked depth pixels into a 3D point cloud. |

| 7 | P ← PointCloudFiltering(P; Θ), including depth-range filtering, downsampling, and outlier removal. |

| 8 | If |P| < N_min, return failure with Q (insufficient valid points). |

| 9 | If d = body height, estimate a ground reference plane and compute the vertical distance. |

| 10 | plane ← EstimateGroundPlane(P; Θ). |

| 11 | ŷ_body_height ← ComputeVerticalDistance(P, plane; Θ). |

| 12 | Else if d = body length, estimate the dominant body axis and compute the endpoint distance. |

| 13 | axis ← EstimateBodyAxis(P; Θ) (plane-/direction-constrained fitting). |

| 14 | ŷ_body_length ← ComputeEndpointDistance(P, axis; Θ). |

| 15 | Else if d = chest circumference, extract a stable thorax cross-section and fit a robust ellipse. |

| 16 | S ← ExtractChestCrossSection(P; Θ). |

| 17 | ellipse ← RobustEllipseFitting(S; Θ). |

| 18 | ŷ_chest_circumference ← EllipsePerimeterApproximation(ellipse; Θ). |

| 19 | Unit conversion: convert the measurement to centimeters if computed in meters/millimeters. |

| 20 | Return ŷ_d and Q. |

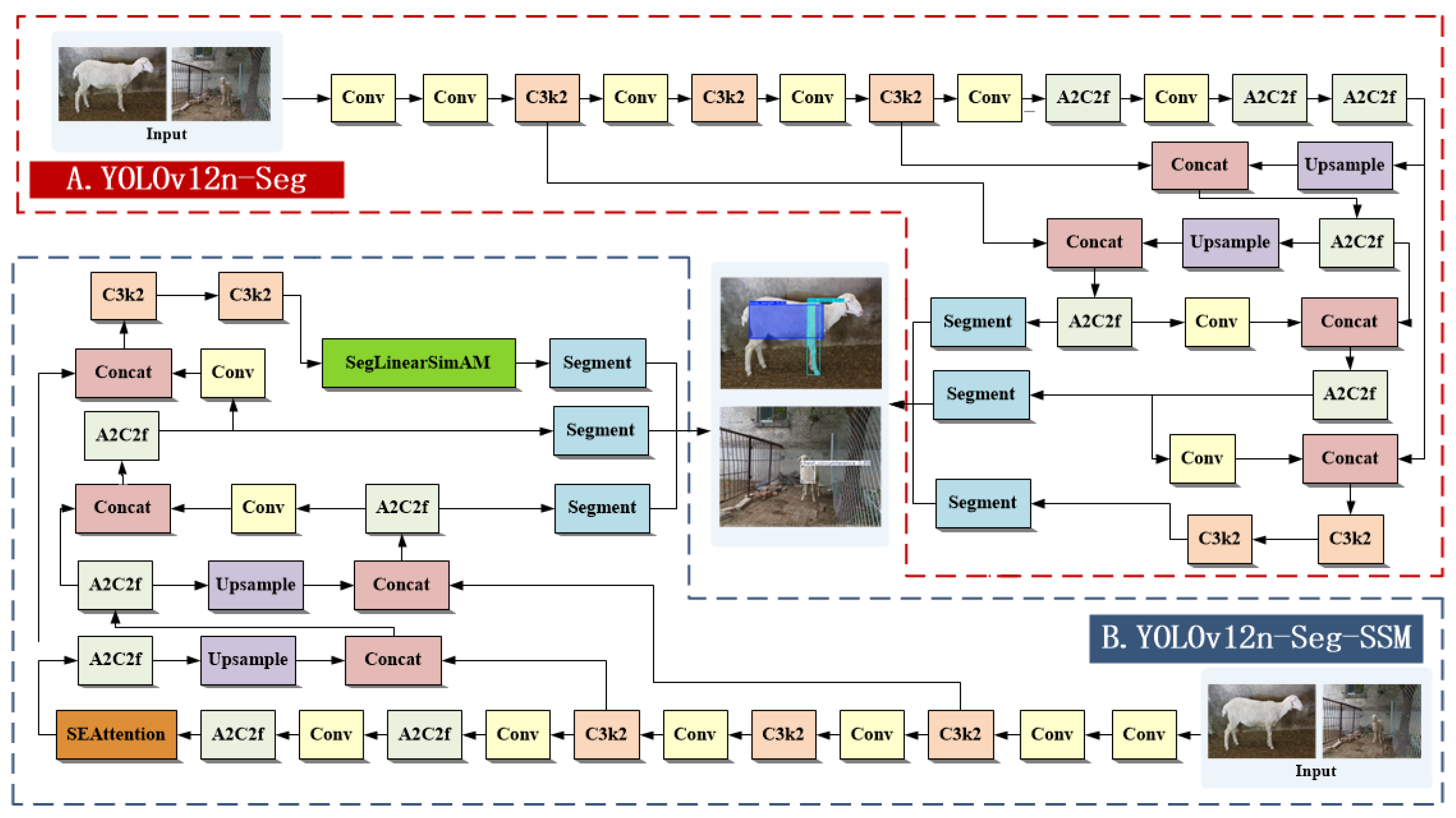

2.4. YOLOv12n-Seg Network Structure Design Optimization

2.4.1. YOLOv12-Seg Model

To achieve automated measurement of sheep body dimensions, this study employs YOLOv12n-Seg as the foundational framework. YOLOv12n-Seg is an instance segmentation variant of YOLOv12 [

22], featuring end-to-end detection and segmentation capabilities. It employs a lightweight backbone architecture (A2C2f and C3k2) and a three-scale feature pyramid to detect objects of varying sizes, achieving high inference efficiency and strong segmentation performance. However, this model still has limitations in feature extraction and bounding box regression for slender targets such as sheep body height and body length, which manifest as incomplete contour segmentation and boundary shifts.

To address these constraints, this paper proposes an improved model, YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM, which enhances the representation capability for slender body measurement regions along three dimensions: feature modeling, channel expression, and loss optimization. (1) The SimAM module is upgraded to SegLinearSimAM, which retains the global attention mechanism while introducing horizontal and vertical response calculations. This enables the model to adaptively enhance directional features of elongated structures such as body length and body height. (2) The MPDIoU loss is optimized to ENMPDIoU by incorporating aspect ratio awareness and directional consistency constraints. This improves the stability of bounding box regression and reduces localization errors for elongated objects. (3) The SEAttention module is integrated to strengthen key feature responses through channel weight redistribution, thereby suppressing background interference and improving segmentation boundary quality. Through these enhancements, YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM effectively improves segmentation accuracy and measurement reliability for sheep body regions while maintaining a lightweight architecture and real-time inference capability.

Figure 4 illustrates the network structures of the original YOLOv12n-Seg and the proposed YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM.

2.4.2. SEAttention Module

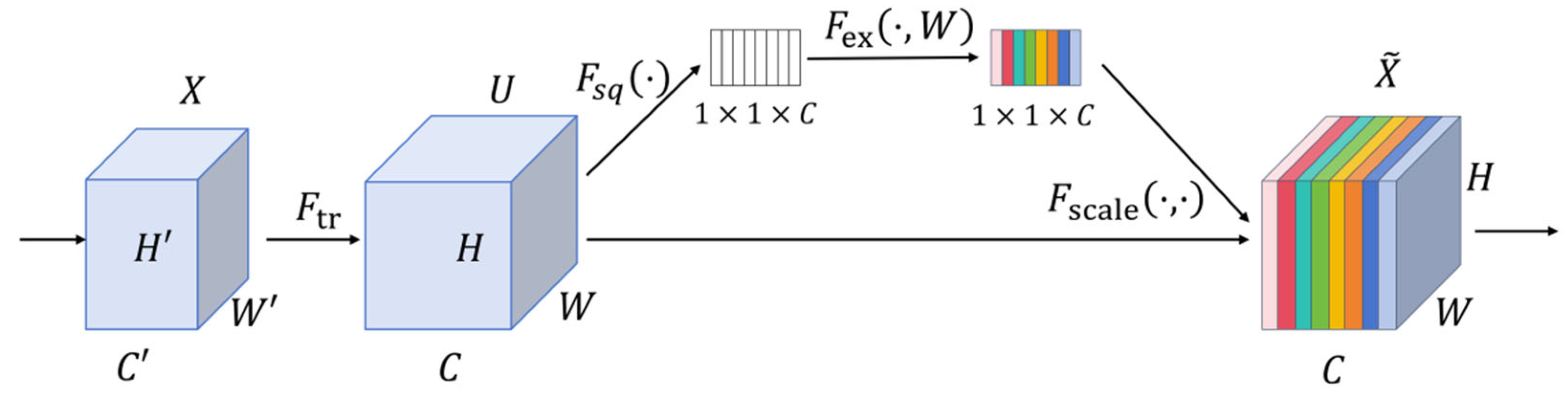

In the task of sheep body dimension segmentation, the SEAttention mechanism [

23,

24] is introduced to optimize interactions between feature channels and better capture features related to sheep body dimensions, and its architecture is shown in

Figure 5. This module integrates global channel statistics with an adaptive weight learning mechanism to enhance the model’s ability to extract key channel features related to sheep body dimensions. Through a two-stage architecture combining squeezing and activation, together with a channel weight calibration mechanism, it focuses on effective feature channels in sheep body part segmentation, such as body boundary channels and contour texture channels. When channel features are mixed (e.g., overlapping hair texture channels and body height boundary channels), it accurately selects key feature channels from multi-channel information while suppressing interference from redundant channels, such as background grassland channels and sheep coat color channels, that degrade segmentation accuracy. Furthermore, it achieves full-level channel optimization from shallow semantic channels to deep feature channels.

In the figure, H(H′), W(W′), and C(C′) represent the height, width, and number of channels of the feature map, respectively; Ftr denotes the traditional convolution operation; Fsq is the compression operation achieved through global average pooling; Fex is the activation operation used to generate weights for each channel; Fscale is the scaling operation that applies the weights to the original feature map. During the squeezing phase, global average pooling compresses the spatial dimensions of the feature map to 1 × 1, yielding a global descriptor of the input features, as shown in Equation (1).

Here, denotes the global descriptor of the -th channel, where as represents the -th channel of the input feature. This process simplifies the feature representation while preserving inter-channel correlations, thereby laying the foundation for subsequent recalibration targeting sheep body measurement features.

During the incentive phase, fully connected layers and nonlinear activation functions adaptively learn the importance of each feature channel. Channel weights generated are then applied to the original feature maps, enabling weighted adjustments to each channel’s features, as shown in Equation (2).

Here, represents the generated channel weights, denotes the sigmoid activation function, denotes the ReLU activation function, and and denote the weights of the fully connected layers. This stage enhances the interaction with features related to sheep body measurements, thereby improving the model’s ability to perceive local details of sheep body dimensions.

2.4.3. ENMPDIoU

In object bounding box regression, traditional IoU-based losses constrain only the overlap area, the distance between box centers, or the aspect ratio of the box. This approach is inadequate for slender objects, such as sheep body length and body height. When predicted boxes substantially overlap with ground-truth boxes but differ in geometric shape or orientation, these losses fail to effectively penalize the discrepancy, leading to increased measurement errors.

To mitigate these issues, the MPDIoU (Minimum Point Distance IoU) [

25] loss introduces a minimum boundary point distance constraint, enhancing the regression capability for bounding box position, as shown in Equation (3).

Among these, IoU denotes the intersection-over-union ratio between the predicted bounding box and the ground truth box; d1 and d2 represent the Euclidean distances from the top-left to the bottom-right corners of the ground truth box and the predicted box, respectively; W and H denote the width and height of the bounding box.

Although MPDIoU [

26] reduces misalignment issues, it still fails to address the aspect ratio differences in elongated objects and does not account for variations in bounding box orientation. To address this, this paper proposes the ENMPDIoU loss function. By introducing aspect ratio difference constraints and orientation consistency constraints, the training process focuses on the geometric shape and directional consistency of the target.

Slender targets are identified by calculating the aspect ratio of the ground truth box (aspet_ratiogt) and the predicted box (aspet_ratiop), generating a linear factor to quantify the slenderness of the target. A width-to-height ratio threshold T = 2.5 is set. Targets are classified as slender when either aspet_ratio_(gt) ≥ T or aspet_ratio_(gt) ≥ T. To smoothly adjust the penalty strength, the width-to-height ratio is mapped to the 0–1 interval to generate the linear factor linear_factor, as shown in Equation (4).

The clamp function is used to restrict the result range and prevent interference from extreme values. The denominator “3” serves as an empirical coefficient to ensure that when the aspect ratio is 4 (a common ratio for sheep body length), the linear factor is approximately 1, thereby achieving targeted penalty adjustment for slender targets.

Determining the primary direction of ground truth and predicted bounding boxes, dynamically adjusting weights based on directional consistency. The primary direction of ground truth is defined as dir = 1 (horizontal) if w > h, otherwise dir = 0 (vertical). The directional consistency weight direction_consistency is calculated as per Equation (5).

When the two frames share the same orientation, the weight is set to 1, and the penalty strength remains unchanged. When the orientations differ, the weight is reduced to 0.6, increasing the penalty intensity to align with the slender object’s heightened sensitivity to directional shifts. The improved ENMPDIoU loss function is expressed as in Equation (6).

The ENMPDIoU loss function introduces aspect ratio awareness and directional consistency constraints beyond the original MPDIoU, enabling the model to more accurately account for geometric features when regressing slender targets (such as body height and body length). This enhances localization accuracy and improves robustness in complex backgrounds and under varying poses. This loss design operationalizes H2 by explicitly incorporating aspect ratio awareness and directional consistency into the bounding-box regression objective for slender body measurement targets.

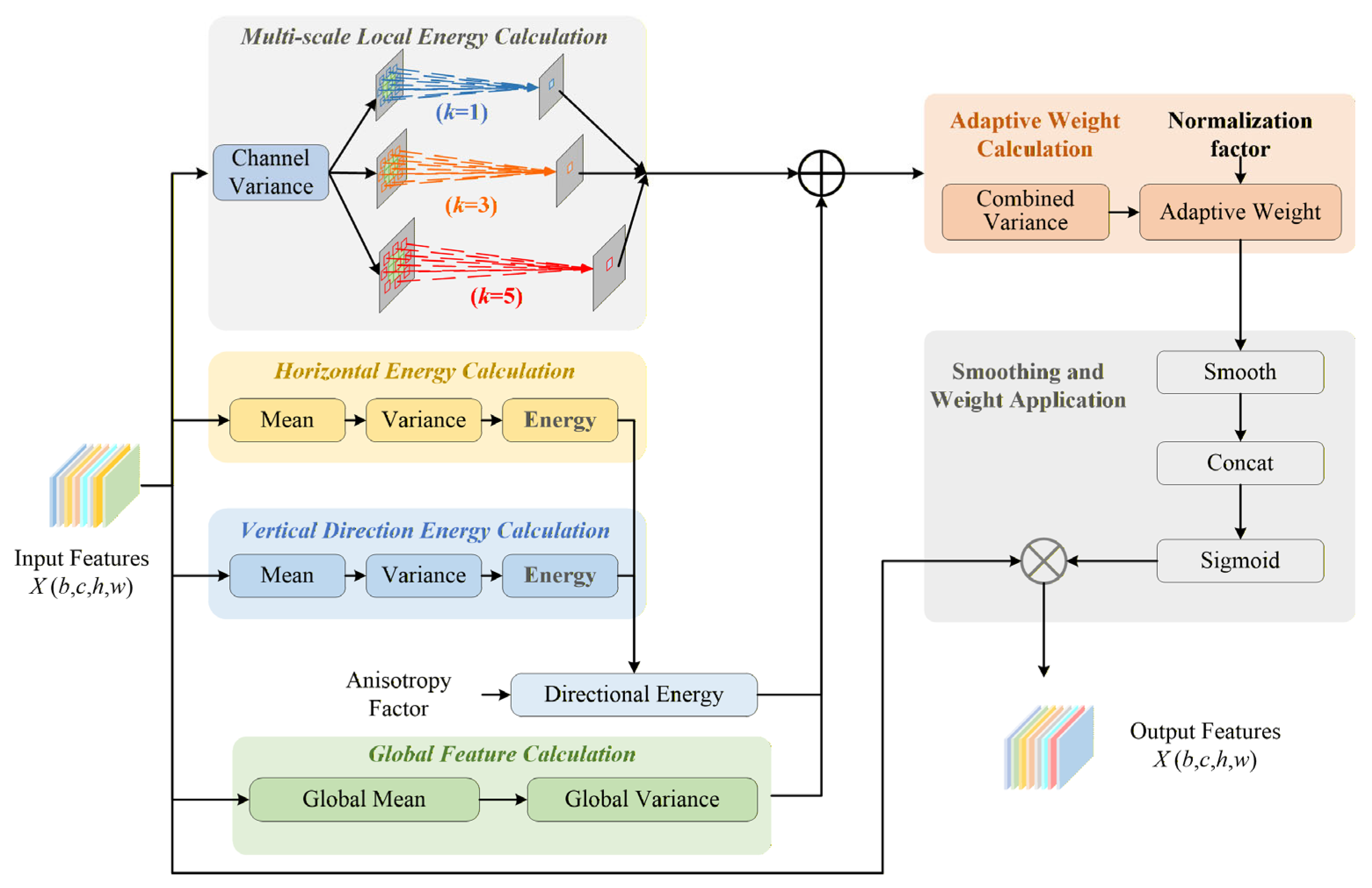

2.4.4. SegLinearSimAM Module

The original SimAM attention mechanism [

27] generates attention weights by calculating the global mean and variance of the feature maps. Although it enables global feature selection, it lacks sufficient sensitivity to directional target regions such as sheep body length and body height. As a result, feature responses in elongated regions are often weak, leading to discontinuous segmentation edges or missed detections. To address this problem, we propose a direction-aware enhanced SimAM attention module. By incorporating directional feature extraction and adaptive fusion mechanisms, the proposed module strengthens feature responses for elongated targets while preserving the original model’s global feature extraction capability. The architecture of the proposed module is shown in

Figure 6.

This module first performs global feature computation on the input feature map

, where

is the batch size,

is the number of channels,

is the height, and

is the width. It follows the original SimAM [

28] global feature extraction logic by computing the global mean of the feature map via global average pooling over both the height and width dimensions to obtain the overall feature distribution. On this basis, it computes the global variance and defines a normalization factor

. These quantities provide the foundational statistics for subsequent adaptive weight calculations, ensuring that the module maintains its ability to capture global features.

To capture directional features of elongated objects, the module introduces two parallel directional energy branches: horizontal and vertical. The horizontal energy branch is responsible for detecting vertically elongated objects, whereas the vertical energy branch is responsible for detecting horizontally elongated objects. To address the dimensional differences between the two directional energies, a transpose operation is applied to align the dimensions of the vertical and horizontal energies, thereby ensuring correctness in the subsequent feature fusion.

In the feature fusion stage, an adjustable anisotropy factor is introduced. Combined with weight coefficients, it integrates the horizontal and vertical directional energies to obtain a unified directional energy. This directional energy is then combined with the global variance to generate a composite variance term, thereby achieving adaptive fusion of global and directional features. The adaptive weight calculation phase adopts the normalization process from the original SimAM [

29]. Based on the composite variance, it generates dynamic adaptive weights by incorporating a normalization factor and avoiding small values that could cause the denominator to approach zero. These adaptive weights are passed through a sigmoid activation to produce an attention mask that distinguishes the importance of target and background regions, assigning higher weights to elongated target areas and lower weights to background regions.

Finally, in the attention application stage, element-wise multiplication is performed between the sigmoid-activated attention mask and the original input feature map to produce an enhanced feature map. This operation amplifies the features of elongated strip-like objects while effectively suppressing background interference, thereby providing more precise feature support for subsequent object detection or segmentation tasks. This module is therefore designed to directly test H1 by strengthening the segmentation and detection of elongated body regions, in particular body length and body height, compared with the baseline YOLOv12n-Seg model.

2.5. Body Size Measurement of Sheep

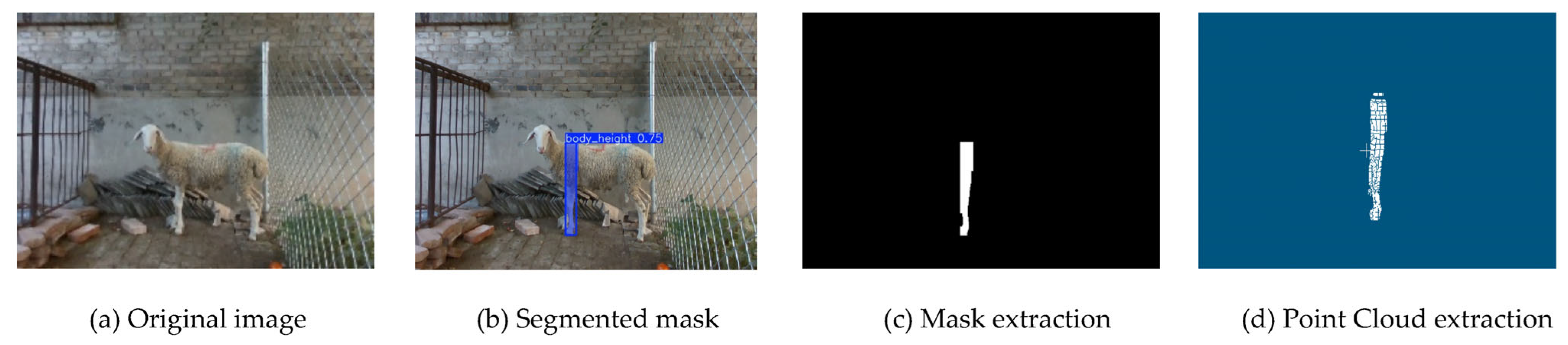

2.5.1. Body Height Measurement

Estimation of body height is based on the spatial relationship between the ground plane and the sheep body in the point cloud data. The segmentation results are used to extract the complete point cloud region corresponding to the sheep body. To accurately identify the ground plane, a deterministic RANSAC (RANdom SAmple Consensus) algorithm [

30,

31] is employed for plane fitting of the point cloud, thereby mitigating result fluctuations caused by random sampling. Stable identification of ground points is achieved through fixed threshold constraints and intra-model point verification.

After ground point removal, the remaining sheep body point cloud undergoes separation and denoising using an adaptive DBSCAN clustering algorithm [

32,

33], ensuring the integrity of the main contour while eliminating isolated noise points.

Figure 7 illustrates the point cloud extraction process for body height estimation. To mitigate interference from occasional anomalies, a quantile-based statistical strategy is further applied. The 5th percentile (

) of the vertical coordinate is adopted as the baseline height for the lower edge of the sheep body. Finally, the body height

is obtained by calculating the height difference between the highest point of the sheep body and the ground reference plane, as shown in Equation (7).

Here, denotes the set of coordinates representing the sheep body point cloud in the vertical direction, and denotes the 5th-percentile point. This method effectively reduces the impact of randomness and noise on the results by leveraging robust statistical measures.

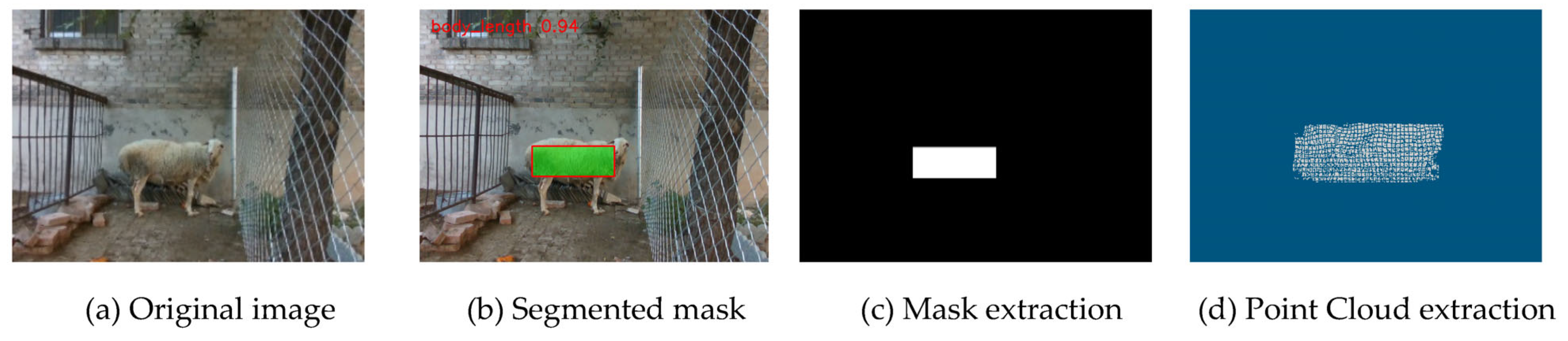

2.5.2. Body Length Measurement

Body length calculation is based on the YOLO-segmented point cloud regions, as shown in

Figure 8. The main body region of the sheep is extracted from the YOLO segmentation results. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [

34,

35] is then applied to perform planar constraints and directional correction on the point cloud, thereby eliminating projection errors caused by variations in shooting angles. PCA determines the direction of the first principal component of the point cloud distribution [

36], which represents the primary extension direction of the sheep body. The extreme distances

,

and

along the three coordinate axes of this planar point cloud are calculated separately, as shown in Equations (8)–(10).

The maximum value among the three is taken as the preliminary estimate for body length to avoid dimensional bias caused by slight postural inclination. If the length of the projection along the PCA principal direction is significantly greater than the current maximum distance (exceeding a 20% threshold), the Euclidean distance along the PCA direction is used instead to ensure that the estimated direction aligns with the main axis of the sheep’s body. The final formula for body length

is given by Equation (11).

The three-dimensional coordinates of the two extreme points are and , respectively. This method combines geometric extremes with statistical directional information, thereby enhancing the robustness and geometric accuracy of body length estimation.

2.5.3. Chest Circumference Measurement

Estimation of sheep chest circumference is based on geometric modeling of the chest cross-sectional point cloud. The chest region is extracted from the segmented 3D point cloud of the sheep body. Outliers and extreme noise are removed using interquartile range (IQR) clipping and statistical filtering [

37] to ensure the density and integrity of the chest cross-sectional point cloud. The processed point cloud is then projected onto a 2D plane to simplify geometric fitting calculations, as shown in

Figure 9.

Two algorithms are available for the ellipse fitting stage: (1) the Minimum Volume Enclosing Ellipse (MVEE) algorithm, which employs the Khachiyan iterative method to obtain the optimal enclosing ellipse that covers the majority of points [

38]; and (2) the OpenCV rotated ellipse fitting method, which estimates ellipse parameters based on the least-squares principle [

39]. When MVEE convergence is unsatisfactory or the samples are sparse, the system automatically switches to the OpenCV method to ensure fitting stability.

The fitting yields the major and minor semi-axes

and

of the ellipse. The ellipse perimeter

is approximated using the Ramanujan-II formula, as shown in Equation (12).

To correct for systematic bias and environmental factors, a linear calibration model is introduced. The post-calibration method for calculating the actual chest circumference is given by Equation (13).

The values of and are determined through multi-sample least-squares fitting or single-sample proportional calibration. This method eliminates systematic shifts caused by depth measurement, pose variations, and model errors, thereby enhancing the accuracy and consistency of the chest circumference estimation results.

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

In this study, multiple metrics were employed to evaluate model performance, including precision (P), recall (R), mAP@0.5 at an IoU threshold of 0.5, the number of parameters, model size, and GFLOPs. As shown in Equation (14), accuracy measures the precision of the segmentation results, representing the proportion of correctly predicted target pixels among all pixels predicted as target regions. As shown in Equation (15), recall indicates segmentation completeness, denoting the proportion of correctly identified target pixels among all actual target pixels. As shown in Equation (16), average precision (AP) is defined as the average of precision values across different recall levels. As shown in Equation (17), mAP@0.5 denotes the mean average precision across all classes when the intersection-over-union (IoU) threshold is set to 0.5. GFLOPs quantifies the computational complexity during inference, guiding hardware resource allocation in balancing speed and accuracy.

TP (true positives) represents the number of positive samples correctly classified by the model; FP (false positives) denotes the number of negative samples incorrectly identified as positive; TN (true negatives) indicates the number of correctly predicted negative samples; and is the number of classes, which is 3 in this study.

3. Experimental Results and Analyses

3.1. Experimental Platform and Parameter Setting

This research was conducted using the PyTorch (version 2.2.1) deep learning framework. The hardware configuration is detailed in

Table 2, comprising a 13th Gen Intel

® Core™ i7-13700KF processor (3.40 GHz), 64 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 GPU with 16 GB of video memory. The system operates on Windows 11 with GPU acceleration enabled via CUDA 12.1.

The training hyperparameter configuration is shown in

Table 3.

3.2. Ablation Study

By comparing the contributions of each module, we conducted ablation experiments to validate the performance improvements of the proposed YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM model. All experiments were conducted without transfer learning to ensure methodological rigor. As shown in

Table 4, when only the SegLinearSimAM module was added, the bounding-box detection mAP@0.5 increased from the baseline of 93.70% to 94.70%, with recall reaching 99.00%. These improvements in detection mAP@0.5 and recall, particularly for the body_length and body_height categories, provide empirical support for H1. In other words, incorporating SegLinearSimAM effectively enhances the model’s ability to detect and segment elongated body regions compared with the baseline YOLOv12n-Seg. This result confirms the advantage of the SegLinearSimAM module in enhancing the model’s perception of the sheep’s body-size orientation and in optimizing bounding-box localization. When only the SEAttention module was added, the segmentation mAP@0.5 increased to 94.00%, and recall reached 99.90%. This indicates that the SEAttention module not only improves segmentation accuracy but also enhances the model’s perception of the sheep’s body-size orientation, thereby playing an important role in bounding-box localization. When the ENMPDIoU module was added alone, the mAP@0.5 dropped to 90.30% for segmentation and 91.80% for detection, respectively. The reason for this performance decline is that the ENMPDIoU module primarily optimizes the bounding-box regression loss for elongated targets, and its effectiveness is highly dependent on high-quality features produced by feature-enhancement modules. Without effective feature enhancement in the baseline model, using ENMPDIoU alone not only fails to realize its optimization benefits but may even have a negative impact on model performance. However, when ENMPDIoU is combined with the SegLinearSimAM and SEAttention modules (Model 5), the bounding-box detection mAP@0.5 increases to 95.00% and the recall reaches 99.00%, which is the best among all configurations. This indicates that, once high-quality feature representations are provided, the proposed ENMPDIoU loss improves the localization of slender body regions, thereby supporting H2.

When all three modules—SegLinearSimAM, SEAttention, and ENMPDIoU—were added to the base model, its performance improved. The mAP@0.5 for image segmentation reached 94.20%, and the mAP@0.5 for bounding-box detection reached 95.00%, representing increases of 0.5% and 1.3%, respectively, compared with the base model. This performance improvement was achieved despite an increase of only 0.11 MB in the number of parameters. This result indicates that the performance gain stems from the synergistic coupling of the three modules rather than from simple additive effects. This finding underscores the importance of jointly optimizing feature extraction and loss functions in complex visual tasks, laying a solid foundation for further exploration of deeper interactions between modules and for transferring this framework to other agricultural automation detection tasks. From the perspective of hypothesis testing, the ablation results confirm H1 by showing that the introduction of SegLinearSimAM leads to measurable gains in detection and segmentation performance for elongated body regions.

3.3. Comparison Experiment

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of key performance metrics for six lightweight YOLO-based segmentation models—YOLOv5n-Seg, YOLOv6n-Seg, YOLOv8n-Seg, YOLOv10n-Seg, YOLOv11n-Seg, and YOLOv12n-Seg—alongside the proposed improved model YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM. The evaluation metrics include precision, recall, mAP@0.5, FLOPs, and the number of parameters.

In the body measurement segmentation task, the YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM model demonstrated outstanding detection capabilities, achieving a segmentation-region recall of 98.00%. This performance is comparable to that of YOLOv5n-Seg and surpasses that of the other benchmark models. These results indicate that YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM effectively reduces missed detections, achieving comprehensive coverage of the sheep body measurement regions.

Regarding segmentation accuracy, the mAP@0.5 of YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM reaches 94.20%, matching that of YOLOv5n-Seg and surpassing YOLOv8n-Seg’s 93.70%. This performance advantage demonstrates the model’s ability to maintain stable segmentation accuracy across different confidence thresholds.

For bounding-box detection, YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM achieves a recall of 99.00%, outperforming all comparison models by approximately 1 percentage point and demonstrating superior precision in target localization. Additionally, the model achieves a bounding-box detection mAP@0.5 of 95.00%, surpassing YOLOv5n-Seg and YOLOv8n-Seg by 0.5 percentage points, which further validates its superior overall detection performance. These gains in bounding-box mAP@0.5 and recall over the baseline YOLOv12n-Seg and other lightweight YOLO variants provide additional evidence in favour of H2, highlighting the effectiveness of the ENMPDIoU loss in refining localization for slender sheep body targets.

Regarding computational efficiency, YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM maintains strong accuracy with a compact footprint (10.71 MB) and low complexity (9.9 GFLOPs), enabling stable real-time inference on edge or server hardware for livestock farm deployment.

3.4. Performance Analysis of YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM Training

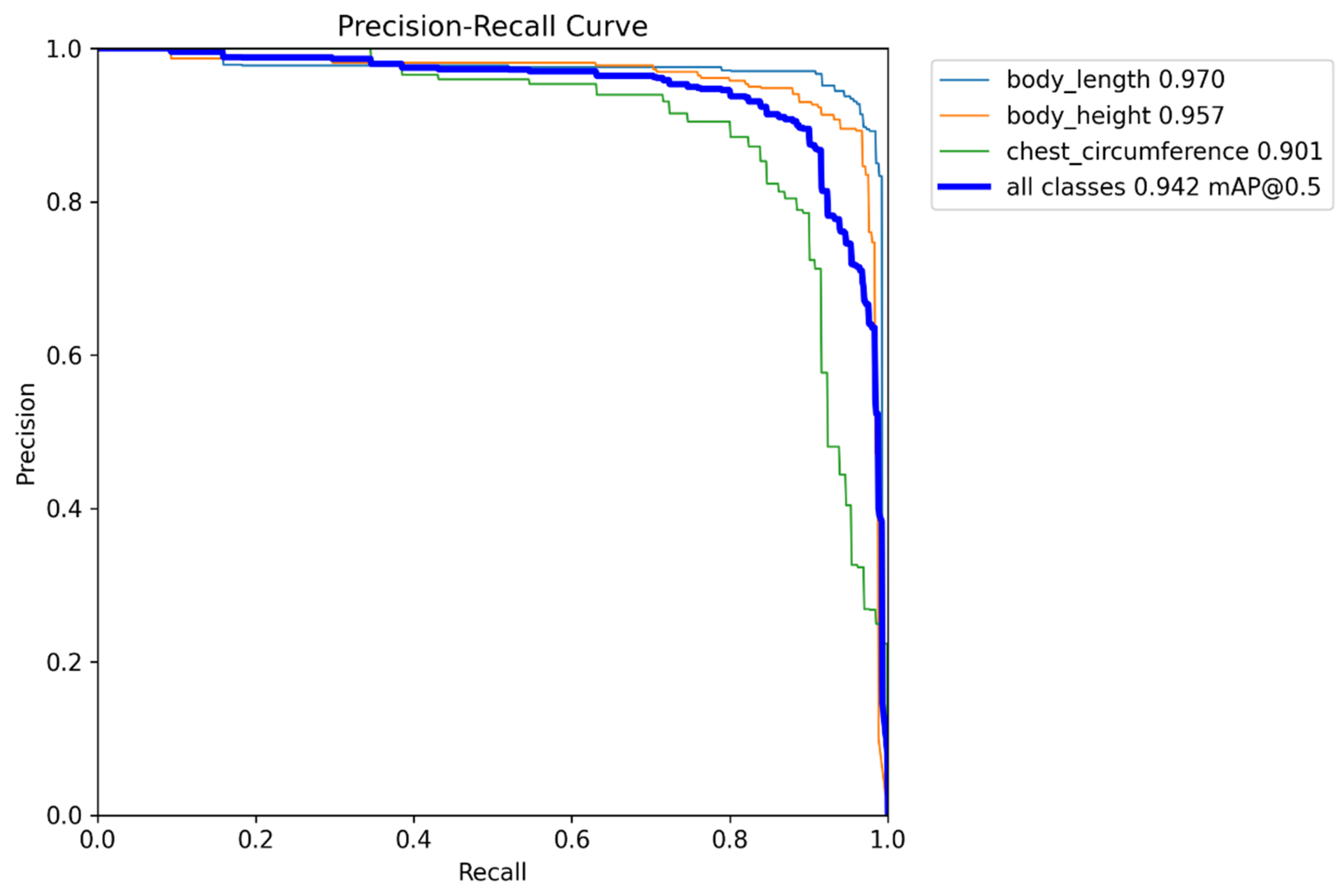

This study applied the improved YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM model to the instance detection task of sheep body measurements. To comprehensively evaluate its performance, precision–recall (PR) curves were constructed for three target categories—body length, body height, and chest circumference—along with a confusion matrix for all four target categories.

As shown in

Figure 10, the model demonstrates outstanding performance in sheep body dimension detection, achieving an overall mAP@0.5 of 0.942, indicating strong detection accuracy and stability. Body length and body height exhibit the highest mean accuracy values, at 0.970 and 0.957, respectively, followed by chest circumference at 0.901. The detection performance for the chest circumference category is relatively weaker. The PR curves indicate that body length and body height maintain high precision across most recall intervals, reflecting the model’s robustness in capturing elongated body measurement targets. Conversely, the precision for chest circumference declines more rapidly, likely because its approximately circular contour is more susceptible to shooting angles and has relatively low visual distinction from the background (e.g., fences, sheep fur). These strong and stable PR curves for body length and body height further corroborate H1, indicating that the proposed feature-enhancement modules, including SegLinearSimAM, significantly improve detection and segmentation performance for elongated sheep body regions.

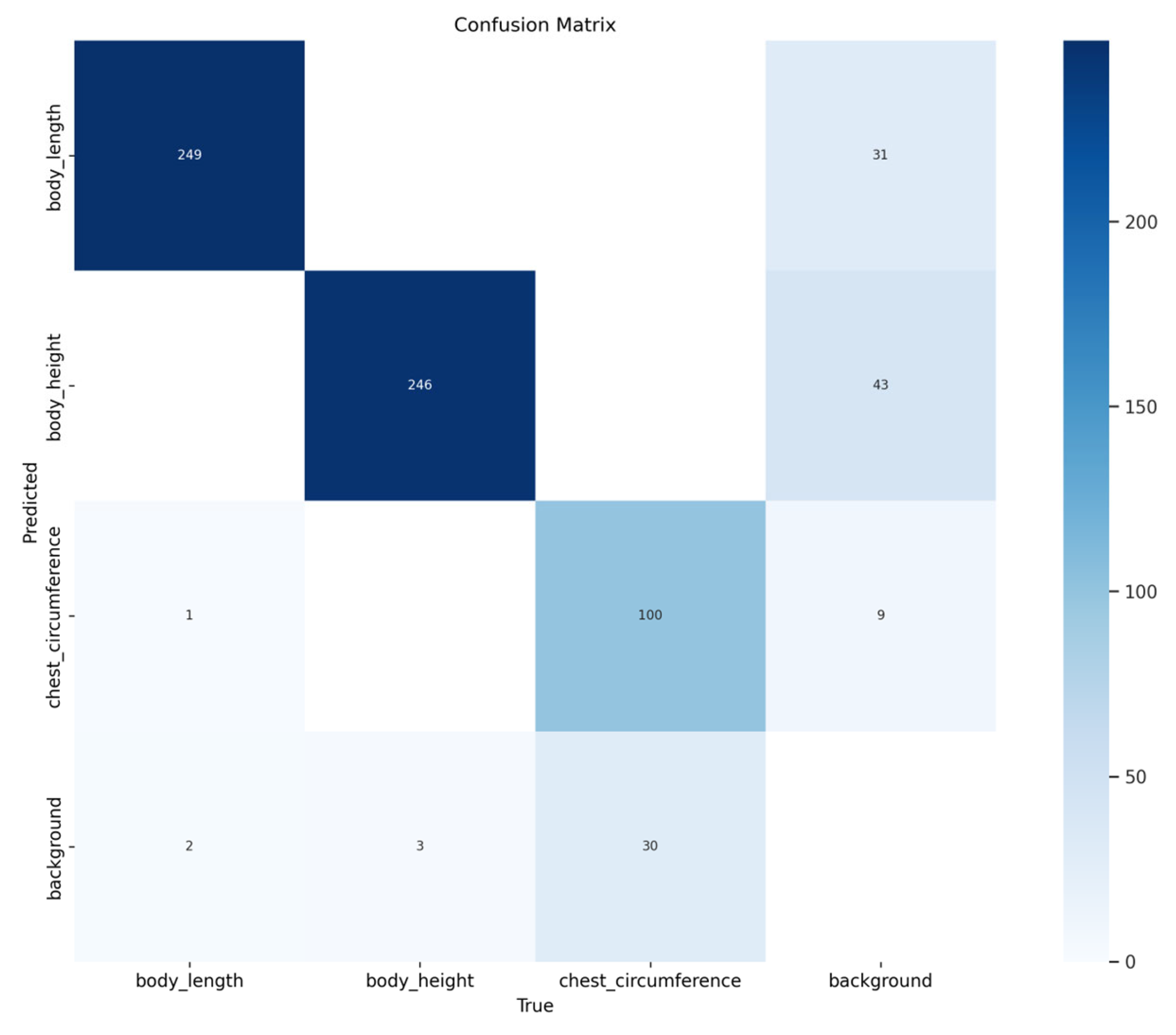

The confusion matrix in

Figure 11 demonstrates the model’s classification performance in sheep body measurement detection: the body_length category correctly identified 249 samples with only 3 misclassifications, and the body_height category correctly identified 246 samples with 43 misclassifications, indicating good differentiation of vertical body measurements. The chest_circumference category correctly identified 10 samples with 9 misclassifications. Additionally, 10 samples in the background class were misclassified as chest_circumference (likely due to visual confusion between the circular chest contour and visually similar background areas), yet the overall classification accuracy remained high. Overall, the model demonstrated outstanding classification accuracy for body_length and body_height, while maintaining good performance for chest_circumference. Category confusion occurred only in a small number of samples. This both reflects the model’s strong robustness in distinguishing between different body measurement targets and backgrounds and validates the effectiveness of the customized improvement strategy targeting sheep body measurements across different orientations and morphological features.

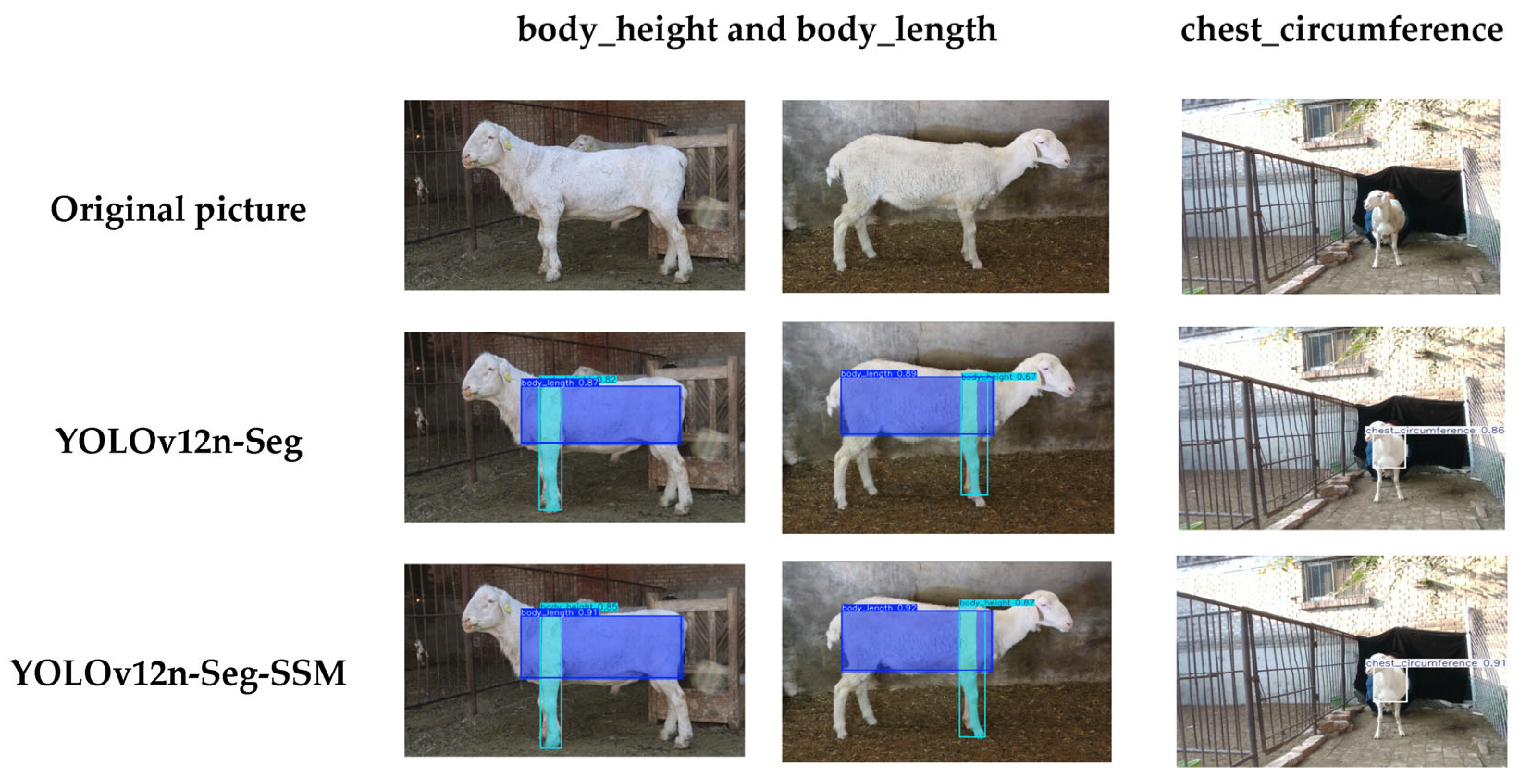

As shown in

Figure 12, we conducted a visual evaluation to assess its detection capabilities, providing an intuitive comparison between the proposed model and the original YOLOv12n-Seg outputs. The improved YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM model produces bounding boxes that provide more complete coverage and tighter fitting around the sheep’s body length, body height, and chest circumference regions. For instance, the body-length bounding box fully encloses the sheep’s torso length area, the body-height bounding box precisely corresponds to the vertical range from the highest point of the shoulder blades to the ground, and the chest-circumference bounding box closely follows the circular contour of the chest. Even under complex backgrounds (brick walls, iron fences) and non-standard sheep postures, the improved model maintains stable detection results with minimal disruption to confidence scores. This demonstrates enhanced scene adaptability, laying a more reliable 2D detection foundation for subsequent 3D body measurement calculations.

3.5. Sheep Body Measurements Results

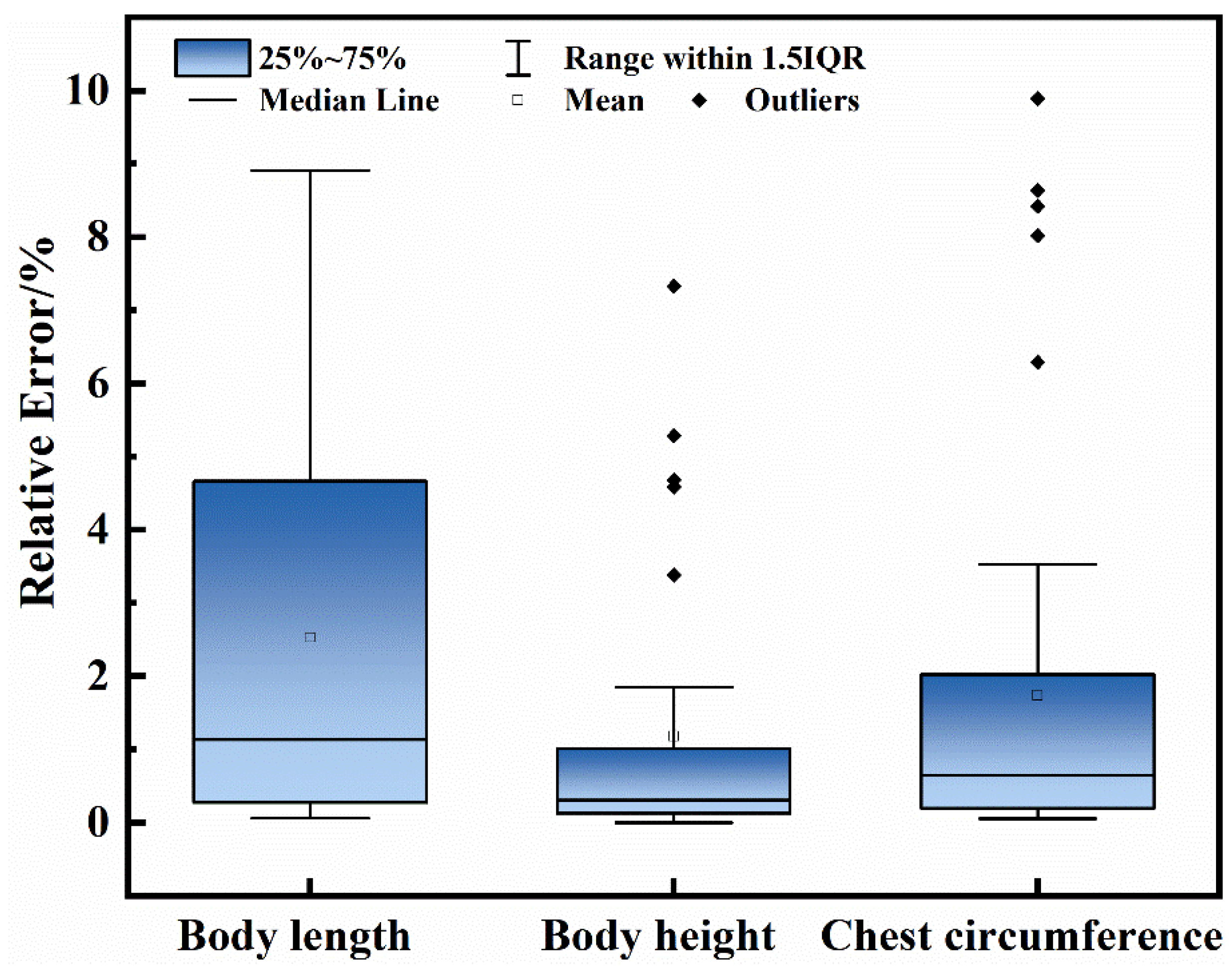

Measurements from 43 images of Hu sheep revealed noticeable differences in accuracy and stability across body-dimension traits. Body height achieved the lowest mean relative error (RE) at 1.13% (95% CI: 0.65–1.70%), indicating consistently high accuracy at the animal level; however, its maximum RE reached 7.30%, suggesting that substantial deviations may occur when point clouds are incomplete or severely occluded. Body length showed a higher mean RE of 3.56% (95% CI: 2.14–5.04%), while chest circumference achieved a mean RE of 2.50% (95% CI: 1.10–4.10%). The maximum RE exceeded 8.00% for both body length and chest circumference, indicating greater variability and sensitivity to environmental disturbances. These error patterns are likely attributable to imperfect point-cloud fitting, posture-related geometric changes, and segmentation inaccuracies, particularly along curved body regions. The measurement results are summarized in

Figure 13, and the corresponding animal-level bootstrap confidence intervals are reported in

Table 6. Overall, all three key body dimensions exhibited mean RE values below 5%, and their 95% confidence intervals further support the robustness of the proposed pipeline, providing empirical evidence for H3 and demonstrating that the integrated YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM and 3D point-cloud framework meets the targeted non-contact measurement accuracy under realistic farm conditions.

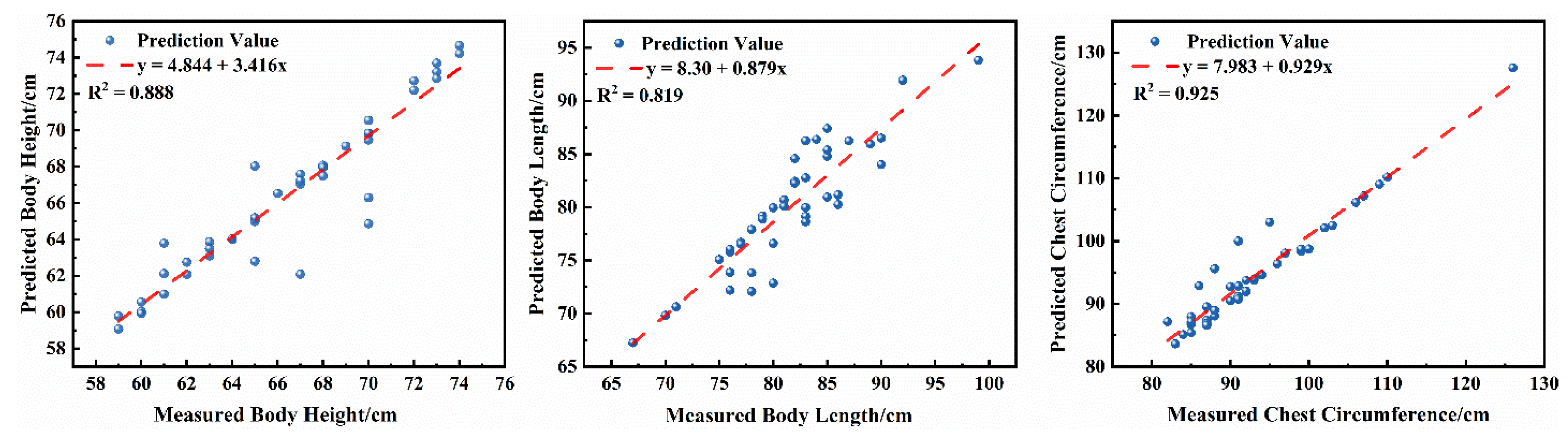

To further quantify the improvements in the model’s measurement accuracy for sheep body dimensions, regression analyses were conducted on predicted values versus actual values for body height, body length, and chest circumference. The results are shown in

Figure 14. The high coefficients of determination for all three traits, together with the low mean relative errors, further substantiate H3.

The results of the regression analyses indicate that the predicted body measurements for sheep exhibit linear correlations with the actual measurements. The regression coefficients for body height, body length, and chest circumference were , and , respectively, all indicating high levels of correlation. Outliers in body height and body length predictions primarily stemmed from variations in viewing angles, occlusions, and changes in posture, whereas outliers in chest circumference measurements were mainly influenced by leg and neck interference. Overall, the improved model reliably and accurately reflects actual variations in key sheep body measurements, demonstrating excellent precision and reliability in non-contact measurements of body height, body length, and chest circumference. This provides robust data support for subsequent individual growth monitoring and trait evaluation.

measures the model’s ability to explain data variation and reflects the degree of fit between the predicted and actual values. The calculation method is shown in Equation (18).

Here, represents the mean of the actual values, and denotes the predicted value. The range of is , with values closer to 1 indicating a better model fit and effectively reflecting the linear correlation between the predicted and actual values.

3.6. Segmentation-to-Measurement Error Propagation

In order to quantify how segmentation uncertainty propagates to downstream 3D reconstruction and geometric fitting, we conducted an error-budget analysis by perturbing the predicted instance masks and re-running the identical RGB-D processing pipeline. Representative perturbations were selected to reflect three common uncertainty patterns: (i) confidence-threshold variation (conf_th = 0.60) to examine how stricter mask filtering affects pipeline availability, (ii) random boundary dropout (dropout = 0.20) to emulate localized boundary defects, and (iii) systematic boundary shifts using morphological operations (kernel size = 7) to stress-test dilation/erosion effects. For each animal, a baseline measurement was first obtained with the unperturbed masks, and all downstream steps were kept unchanged across perturbations, including depth completion (when enabled), back-projection, point-cloud filtering, and trait-specific geometric fitting. We report the failure rate (the fraction of animals for which the pipeline did not output a valid measurement due to insufficient valid points or unstable fitting) and the absolute difference between the perturbed and baseline measurements (cm), summarized by the mean and the 95th percentile at the animal level. The results are summarized in

Table 7.

As shown in

Table 7, increasing the confidence threshold primarily influenced availability rather than the numerical stability of successful measurements. In particular, setting conf_th to 0.60 led to the highest failure rate for chest circumference (approximately 28%), whereas failure rates for body height and body length remained noticeably lower (around 7% and 5%, respectively). This pattern suggests that strict mask filtering can reduce mask coverage and the number of valid depth pixels required for stable fitting, especially when a dense thorax cross-section is needed. Random boundary dropout resulted in only modest deviations across traits: mean absolute differences remained small (on the order of ≤1.5 cm) and the upper-tail deviations (95th percentile) remained within a few centimeters, indicating that the downstream geometric fitting is relatively tolerant to localized boundary defects. In contrast, systematic boundary shifts dominated the error budget. Morphological dilation/erosion produced substantially larger deviations than the other perturbations, including heavy-tailed behavior for body length (with occasional large deviations under dilation), elevated sensitivity of body height under erosion (mean differences on the order of ~10 cm), and consistent centimeter-level sensitivity for chest circumference (mean differences close to 9 cm under the strongest perturbation). Overall, these findings indicate that systematic mask boundary bias is the dominant driver of segmentation-to-measurement error amplification, whereas localized boundary defects have limited impact; therefore, improving boundary fidelity and maintaining sufficient cross-sectional point density are likely to be the most effective directions for further robustness improvement.

4. Discussion

This study presents an end-to-end, non-contact pipeline for sheep body-dimension measurement by fusing a lightweight instance segmentation model (YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM) with RGB-D point-cloud reconstruction and trait-specific geometric fitting. Non-contact phenotyping has been increasingly explored for precision sheep and livestock farming to improve efficiency and reduce handling stress [

1,

6]. The experimental results on 43 Hu sheep indicate that the proposed system can achieve practical measurement accuracy under farm conditions, with mean relative errors below 5% for body height, body length, and chest circumference. In addition to point estimates, we report animal-level bootstrap 95% confidence intervals, which characterize reliability more clearly than averaged errors alone and help assess field readiness.

A major practical finding is that measurement performance depends not only on segmentation accuracy but also on point-cloud integrity and the stability of downstream geometric fitting. Our segmentation-to-measurement sensitivity analysis (“error budget”) quantifies how segmentation uncertainty propagates into measurement deviations and pipeline availability, revealing that stricter confidence-threshold filtering can reduce numerical errors but also increase failure rates by removing valid pixels and points needed for stable geometric extraction. This trade-off is particularly important for field deployment, where low errors on successful cases alone may overestimate practical usefulness if availability is not reported.

The three traits exhibit different sensitivity to real-world disturbances. Body height tends to be more stable because it is anchored to a ground reference and depends mainly on a vertical extent, whereas body length and chest circumference are more sensitive to body curvature, local occlusions, and the completeness of the reconstructed point cloud [

16,

40,

41].In particular, chest circumference is consistently the most error-prone trait because it depends on extracting a complete and anatomically correct thorax cross-section from RGB-D point clouds. In practice, partial occlusion (forelimbs or neck overlap), missing depth on woolly surfaces, and slight posture rotation can distort the contour and bias ellipse fitting, leading to outliers. To mitigate this, three concrete design changes are promising: (i) enforcing an anatomically constrained slicing window along the principal body axis (e.g., around the scapula region) to avoid neck/leg interference; (ii) aggregating multiple adjacent slices using robust statistics (median or trimmed mean) rather than relying on a single slice; and (iii) adopting a robust perimeter estimator that down-weights incomplete arcs and outliers instead of fitting a single ellipse to all points. These improvements target both numerical error reduction and failure-rate reduction, which is critical for reliable deployment.

Although the proposed pipeline includes data augmentation, depth completion, and point-cloud filtering to improve robustness, several farm-relevant uncertainty sources deserve explicit discussion. Wool thickness and fleece texture can reduce depth integrity by increasing invalid depth pixels and creating sparse or noisy point regions, while fleece colour and illumination changes can affect RGB appearance and segmentation stability [

3,

4,

8]. Strong sunlight, shadows, and low-light indoor environments may also alter RGB-D sensor noise characteristics, and these effects can degrade geometric fitting even when segmentation appears visually acceptable. Therefore, performance may vary across coat conditions and lighting regimes, and a stratified evaluation (short vs. long wool; indoor vs. outdoor; different times of day) is necessary to quantify how errors and failure rates shift under these operating conditions.

Flock environments also involve self-occlusion by limbs and occlusion from neighbouring animals. While instance segmentation and point-cloud preprocessing can tolerate mild occlusion, severe occlusion may truncate masks, fragment the point cloud, and prevent stable extraction of thorax cross-sections—disproportionately affecting chest circumference [

4,

6]. We therefore clarify that the current evaluation mainly targets single-animal visibility under guided standing posture, and systematic validation under controlled occlusion levels (e.g., 10/30/50% visible area) remains an important next step. Such experiments should jointly report measurement error and availability (failure rate), since availability is a key determinant of farm usability.

Operational reliability further depends on behavioural variability and repeatability across time and operators. Stress-related posture changes, head movement, and stepping can modify body geometry and increase depth discontinuities, causing scan-to-scan variability even for the same individual [

1,

3,

7]. Although our manual reference measurements were repeated to reduce random error, the automated system’s repeatability has not yet been quantified under minimally constrained conditions. Future deployment-oriented evaluations should include repeated scans of the same individuals across days and multiple operators, reporting reliability metrics such as coefficient of variation and intraclass correlation, together with latency and failure rate.

Regarding novelty and positioning relative to emerging state-of-the-art approaches, large pretrained or foundation segmentation models offer impressive open-world generalization, but practical farm deployment may be limited by latency, memory footprint, and the need for stable, task-specific anatomical boundaries under domain shifts. Our approach emphasizes a lightweight, task-specific segmentation model optimized for elongated anatomical regions, coupled with explicit 3D geometric constraints that convert masks into measurable traits; similar 3D measurement pipelines have been explored in livestock but often face deployment and robustness challenges [

40,

41,

42]. The hypotheses (H1–H3) are intended to be testable: H1–H2 are supported by improved segmentation/detection and localization stability relative to the baseline model, while H3 is supported by sub-5% mean relative errors in three traits and by confidence intervals that quantify reliability.

Future work will focus on several concrete, testable directions: (1) external validation across breeds, coat conditions, and farms with subgroup analysis by wool length and illumination regime; (2) controlled robustness experiments under varying occlusion severity with joint reporting of errors and failure rates; (3) repeatability studies across time and operators using reliability metrics (CV/ICC) and availability/latency measures; (4) targeted improvement of chest circumference through anatomically constrained multi-slice robust fitting and short temporal aggregation of RGB-D frames; and (5) exploring constrained incorporation of foundation-model priors (e.g., teacher–student distillation or prompt-assisted refinement) while preserving real-time on-device inference.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a non-contact automated measurement solution for sheep body dimensions based on YOLOv12n-Seg-SSM and 3D point clouds, achieving an integrated processing workflow from target detection and body-region segmentation to geometric quantification. Through the synergistic optimization of the SegLinearSimAM feature-enhancement module, the SEAttention channel-optimization module, and the ENMPDIoU loss, the segmentation mAP@0.5 reaches 94.20%, the detection mAP@0.5 reaches 95.00%, and the recall improves to 99.00%. In validation on 43 Hu sheep, the values for chest circumference, body height, and body length were 0.925, 0.888, and 0.819, respectively, with measurement errors controlled within 5%. The model parameters are only 10.71 MB, and the computational overhead is 9.9 GFLOPs, enabling real-time operation on edge devices. This method establishes a feature-enhancement and loss-optimization mechanism tailored for slender body measurements, improving segmentation and localization accuracy in complex environments. It integrates lightweight semantic segmentation with 3D point-cloud geometric computation, achieving a balance between precision and efficiency. Utilizing low-cost RGB-D devices simplifies the measurement process and lowers the technical implementation threshold. The research findings demonstrate that this method enables precise, efficient, and non-contact measurement of sheep body dimensions. It provides reliable data support for growth monitoring, feeding management, and genetic breeding in livestock farms, holding significant implications for advancing the intelligent and precision-oriented development of the animal husbandry industry. Overall, the experimental results validate the three hypotheses formulated in the Introduction: (H1) and (H2) regarding improved detection and segmentation of elongated body regions through targeted feature-enhancement and loss design, and (H3) regarding non-contact 3D measurement of sheep body dimensions with mean relative errors below 5% under farm conditions.