The Effect of Potato Seed Treatment on the Chemical Composition of Tubers and the Processing Quality of Chips Assessed Immediately After Harvest and After Long-Term Storage of Tubers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Material

2.2. Dry Matter Content in Potato Tubers

- DM—dry matter content (%)

- SWB—sample weight before drying (g)

- SWA—sample weight after drying (g)

2.3. Starch Content in Potato Tubers

- SC—starch content (g kg−1 f.m.)

- a—weight of analyzed material (g)

- L—length of polarimeter tube (dm)

- α—measured rotation in degrees

2.4. Total and Reducing Sugars Content in Potato Tubers

2.5. Carotenoid and Chlorophyll Content in Potato Tubers

2.6. Sensory Evaluation of Chips

2.7. Statistics

3. Results and Discussion

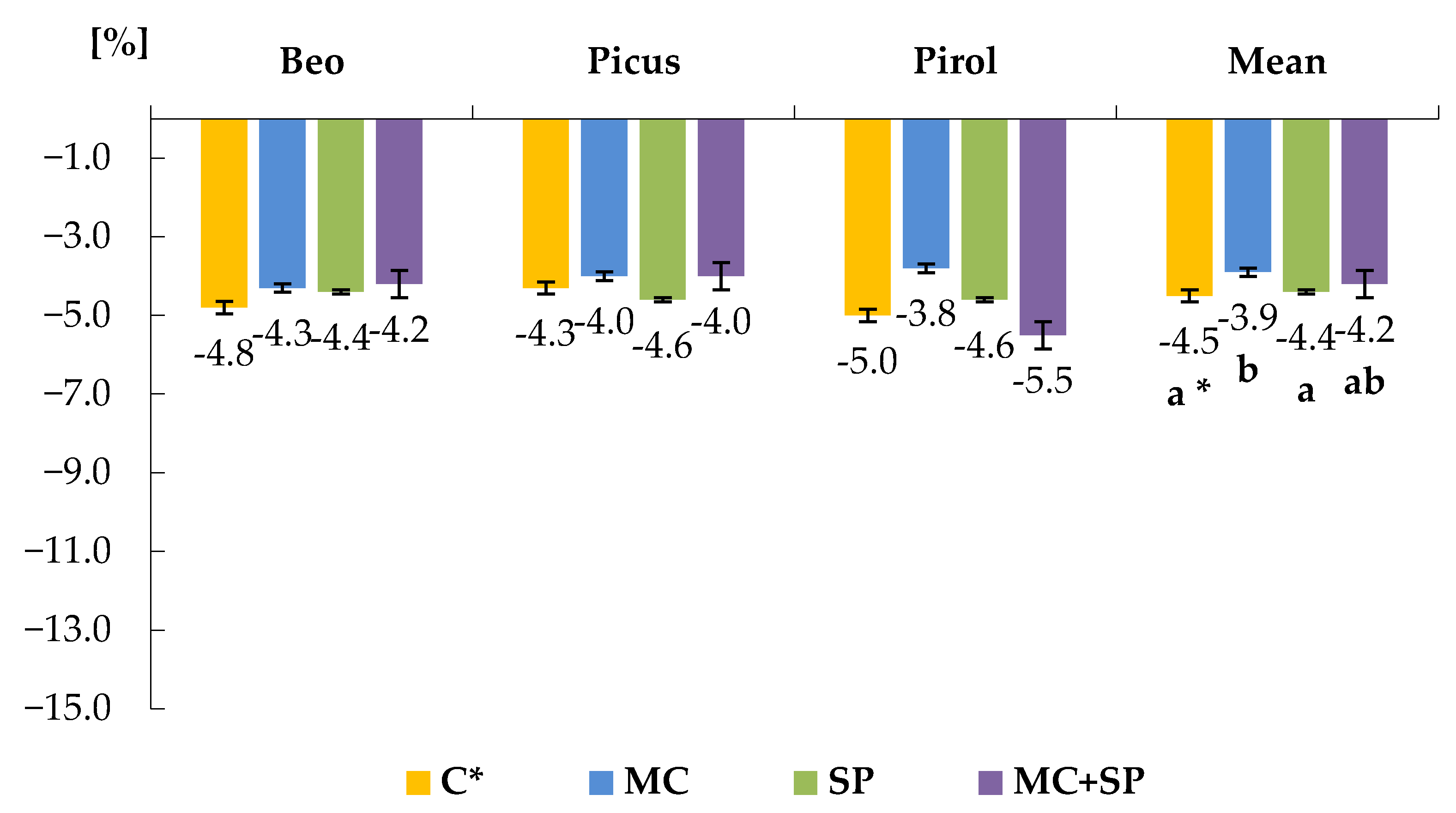

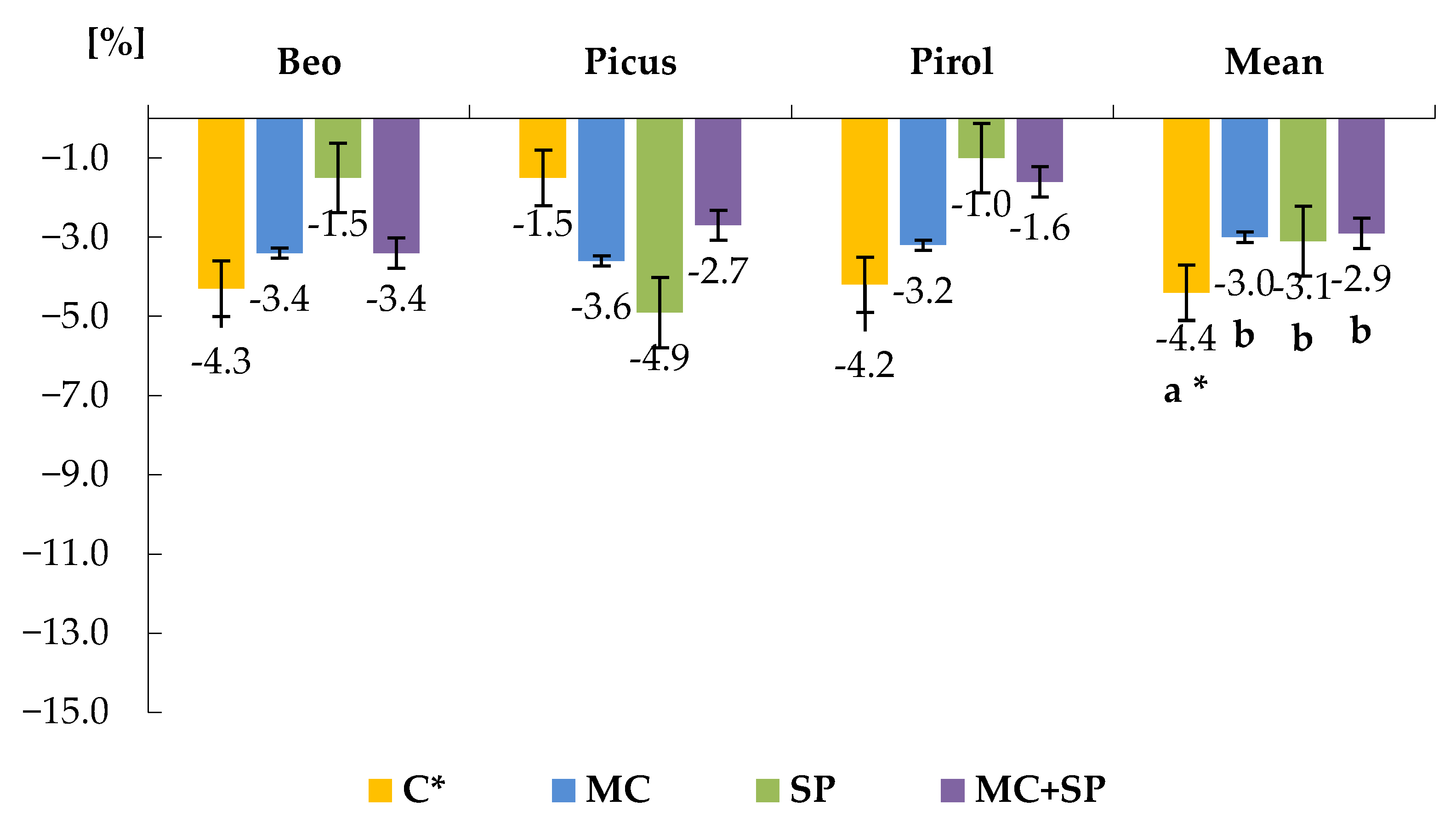

3.1. Dry Matter and Starch

3.2. Total and Reducing Sugars

3.3. Carotenoids

3.4. Chlorophylls

3.5. Chips Quality

3.5.1. Total Sensory Quality and Color

3.5.2. Consistency and Taste

3.5.3. Aroma

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dramićanin, A.M.; Andrić, F.L.; Poštić, D.Ž.; Momirović, N.M.; Milojković-Opsenica, D.M. Sugar profiles as a promising tool in tracing differences between potato cultivation systems, botanical origin and climate conditions. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 72, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, A.; Goffart, J.P.; Petsakos, A.; Kromann, P.; Gatto, M.; Okello, J.; Hareau, G. Global food security, contributions from sustainable potato agri-food systems. In The Potato Crop: Its Agricultural, Nutritional and Social Contribution to Humankind; Campos, H., Ortiz, O., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzecka, K.; Ginter, A.; Gugała, M.; Durakiewicz, W. Nutritional Value of Coloured Flesh Potato Tubers in Terms of Their Micronutrient Content. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, S.L.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Alexopoulos, A.; Heleno, S.A.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C. Potato peels as sources of functional compounds for the food industry: A review. Trends Food Sci. 2020, 103, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermeier, R.; Hill, K.; Dingis, A.; Töpfl, S.; Jäger, H. Influence of pulsed electric field (PEF) and ultrasound treatment on the frying behavior and quality of potato chips. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 67, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonel, M.; do Carmo, E.L.; Fernandes, A.M.; Soratto, R.P.; Ebúrneo, J.A.M.; Garcia, E.L.; dos Santos, T.P.R. Chemical composition of potato tubers: The effect of cultivars and growth conditions. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2372–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Mitra, B.; Saha, A.; Mandal, S.; Paul, P.K.; El-Sharnouby, M.; Hassan, M.M.; Maitra, S.; Hossain, A. Evaluation of Quality Parameters of Seven Processing Type Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Cultivars in the Eastern Sub-Himalayan Plains. Foods 2021, 10, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzecka, K.; Gugała, M.; Mystkowska, I.; Sikorska, A. Changes in dry weight and starch content in potato under the effect of herbicides and biostimulants. Plant Soil Environ. 2021, 67, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Naznin, S.; Naznin, A.; Uddin, M.N.; Amin, M.N.; Rahman, M.M.; Tipu, M.M.H.; Alsuhaibani, A.M.; Gaber, A.; Ahmed, S. Dry matter, starch content, reducing sugar, color and crispiness are key parameters of potatoes required for chip processing. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystkowska, I. The effect of the use of biostimulators on dry matter and starch content of tuber potatoes. Fragm. Agron. 2019, 36, 45–53. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawczyński, C. The effect of biostimulators on the yield and quality of potato tubers grown in drought and high temperature conditions. Bull. Plant Breed. Acclim. Inst. 2020, 289, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonia, F.; Ronga, D.; Tava, A.; Francia, E. Plant biostimulants in sustainable potato production: An overview. Potato Res. 2022, 65, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Joel, J.M.; Puthur, J.T. Biostimulants: The futuristic sustainable approach for alleviating crop productivity and abiotic stress tolerance. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgórska, K. Quality requirements for potato cultivars intended for food processing. Ziemn. Pol. 2004, 14, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Singh, B.P.; Kumar, P. An overview of the factors affecting sugar content of potatoes. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2004, 145, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, A.; Javed, M.S.; Hameed, A.; Hussain, M.; Ismail, A. Changes in sugar contents and invertase activity during low temperature storage of various chipping potato cultivars. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 40, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourado, C.; Pinto, C.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Delgadillo, I.; Saraiva, J.A. Innovative non-thermal technologies affecting potato tuber and fried potato quality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztofik, B.; Sułkowski, K. Changes of the chemical composition of potato tubers during storage and their impact on the selected properties of crisps. Agric Eng. 2013, 17, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, T.; Królczyk, J.B. Method for the Reduction of Natural Losses of Potato Tubers During their Long-Term Storage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobereżny, J.; Wszelaczyńska, E.; Gościnna, K.; Spychaj-Fabisiak, E. Effect of potato storage and reconditioning parameters on physico–chemical characteristics of isolated starch. Starch-Stärke 2021, 73, 2000019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Boo, H.; Chung, M.S. Effects of extraction conditions on acrylamide/furan content, antioxidant activity, and sensory properties of cold brew coffee. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brążkiewicz, K.; Pobereżny, J.; Wszelaczyńska, E.; Bogucka, B. Potato starch quality in relation to the treatments and long-term storage of tubers. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Cereal Chemistry (AACC). Approved Method 44-15 A (Moisture-Air Oven Methods); AACC: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft Getreideforschung, e.V. Standard Methoden Für Getreide Mehl Und Brot, 7th ed.; Verlag Moritz Schäfer: Detmold, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Talburt, W.; Smith, O. Potato Processing (No 6648 T3 1987); Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 371–474. [Google Scholar]

- Sensory analysis—Methodology—General Guidance for Conducting Hedonic Tests with Consumers in a Controlled Area. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://www.iso.org/ics/67.240/x/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Baryłko-Pikielna, N. Outline of Sensory Analysis of Food; WNT: Warszawa, Poland, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Zarzecka, K.; Gugała, M.J.; Ginter, A.; Durakiewicz, W. Formation of starch and dry matter content in tubers potato with colored flesh. Fragm. Agron. 2024, 41, 32–45. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cătuna Petrar, T.M.; Brașovean, I.; Racz, C.-P.; Mîrza, C.M.; Burduhos, P.D.; Mălinaș, C.; Moldovan, B.M.; Odagiu, A.C.M. The Impact of Agricultural Inputs and Environmental Factors on Potato Yields and Traits. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzińska, M.; Boguszewska-Mańkowska, D.; Zarzyńska, K. Drought stress during the growing season: Changes in reducing sugars, starch content and respiration rate during storage of two potato cultivars differing in drought sensitivity. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2022, 208, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezekiel, R.; Rani, M. Oil content of potato chips: Relationship with dry matter and starch contents, and rancidity during storage at room temperature. Potato J. 2006, 33, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gościnna, K.; Retmańska, K.; Wszelaczyńska, E.; Pobereżny, J. Influence of Edible Potato Production Technologies with the Use of Soil Conditioner on the Nutritional Value of Tubers. Agronomy 2024, 14, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Naumann, M.; Pawelzik, E. Cracking and fracture properties of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers and their relation to dry matter, starch, and mineral distribution. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 3149–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, W. Specific gravity, dry matter content, and starch content of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) varieties cultivated in Eastern Ethiopia. East Afr. J. Sci. 2016, 10, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, K.; Li, X.Q.; Tai, H.; Creelman, A.; Bizimungu, B. Improving potato stress tolerance and tuber yield under a climate change scenario—A current overview. Front. Plant. Sci. 2019, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymuza, K.; Radzka, E.; Lenartowicz, T. Influence of precipitation and thermal conditions on starch content in potato tubers from medium-early cultivars group. J. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 16, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowska, A.J. Yield of dry matter and starch of edible potato tubers in conditions of application of growth biostimulators and herbicide. Acta Agrophys. 2018, 25, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karak, S.; Thapa, U.; Hansda, N.N. Impact of biostimulant on growth, yield and quality of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Biol. Forum–Int. J. 2023, 15, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Medina Avendaño, J.D.; Pinzón-Sandoval, E.H.; Torres-Hernández, D.F. Improvement of growth and productivity in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) crop by using biostimulants. Agron. Colomb. 2024, 42, e114683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobereżny, J.; Wszelaczyńska, E. Effect of bioelements (N, K, Mg) and long-term storage of potato tubers on quantitative and qualitative losses Part II. Content of dry matter and starch. J. Elem. 2011, 16, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Kumar, V.A.; Brar, A. Biochemical behaviour of potato tubers during storage. Chem. Sci. Rev. Lett. 2017, 6, 1818–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, S.; Ahmed, N.; Phogat, N. Potato Starch as Affected by Varieties, Storage Treatments and Conditions of Tubers. In Starch-Evolution and Recent Advances; Ochubiojo Emeje, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Li, X.Q.; Tang, R.; Zhang, G.; Li, X.; Cui, B.; Mikitzel, L.; Haroon, M. Starch granule sizes and degradation in sweet potatoes during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 150, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkar, M.; Ahmed, J.U.; Hoque, M.A.; Mohi-Ud-Din, M. Influence of harvesting date on chemical maturity for processing quality of potatoes. Ann. Bangladesh Agric. 2019, 23, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorramifar, A.; Rasekh, M. Changes in sugar and carbohydrate content of different potato cultivars during storage. J. Environ. Sci. Stud. 2022, 7, 4643–4650. [Google Scholar]

- Gikundi, E.N.; Sila, D.N.; Orina, I.N.; Buzera, A.K. Physico-chemical properties of selected Irish potato varieties grown in Kenya. Afr. J. Food Sci. 2021, 15, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzecka, K.; Gugała, M. The effect of herbicides and biostimulants on sugars content in potato tubers. Plant Soil Environ. 2018, 64, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głosek-Sobieraj, M.; Wierzbowska, J.; Cwalina-Ambroziak, B.; Waśkiewicz, A. Protein and sugar content of tubers in potato plants treated with biostimulants. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2022, 62, 370–384. [Google Scholar]

- Cortiello, M.; Milc, J.; Sanfelici, A.; Martini, S.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Caccialupi, G.; Ben Hassine, M.; Giovanardi, D.; Francia, E.; Caradonia, F. Genotype and Plant Biostimulant Treatments Influence Tuber Size and Quality of Potato Grown in the Pedoclimatic Conditions in Northern Apennines in Italy. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2024, 18, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wszelaczyńska, E.; Pobereżny, J.; Gościnna, K.; Szczepanek, M.; Tomaszewska-Sowa, M.; Lemańczyk, G.; Lisiecki, K.; Trawczyński, C.; Boguszewska-Mańkowska, D.; Pietraszko, M. Determination of the effect of abiotic stress on the oxidative potential of edible potato tubers. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamar, M.C.; Tosetti, R.; Landahl, S.; Bermejo, A.; Terry, L.A. Assuring potato tuber quality during storage: A future perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhen-Xiang, L. Effects of storage temperature and duration on carbohydrate metabolism and physicochemical properties of potato tubers. J. Food Nutr. 2021, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pobereżny, J.; Wszelaczyńska, E.; Mozolewski, W. Quality of French fries depending on the potato storage technology. Inż. Ap. Chem. 2016, 55, 156–157. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Tatarowska, B.; Milczarek, D.; Wszelaczyńska, E. Carotenoids Variability of Potato Tubers in Relation to Genotype, Growing Location and Year. Am. J. Potato Res. 2019, 96, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, J.; Hamouz, K.; Orsák, M.; Kotíková, Z. Carotenoids in potatoes—A short overview. Plant Soil Environ. 2016, 62, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulli, M.; Mandolino, G.; Sturaro, M.; Onofri, C.; Diretto, G.; Parisi, B.; Giuliano, G. Molecular and biochemical characterization of a potato collection with contrasting tuber carotenoid content. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogelman, E.; Oren-Shamir, M.; Hirschberg, J.; Mandolino, G.; Parisi, B.; Ovadia, R.; Tanami, Z.; Faigenboim, A.; Ginzberg, I. Nutritional value of potato (Solanum tuberosum) in hot climates: Anthocyanins, carotenoids, and steroidal glycoalkaloids. Planta 2019, 249, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changan, S.S.; Taylor, M.A.; Raigond, P.; Dutt, S.; Kumar, D.; Lal, M.K.; Kumar, M.; Tomar, M.; Singh, B. Potato Carotenoids. In Potato Nutrition and Food Security; Raigond, P., Singh, B., Dutt, S., Chakrabarti, S.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitkevičienė, N.; Jarienė, E.; Kulaitienė, J.; Levickienė, D. The Physico-Chemical and Sensory Characteristics of Coloured-Flesh Potato Chips: Influence of Cultivar, Slice Thickness and Frying Temperature. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturaro, M. Carotenoids in Potato Tubers: A Bright Yellow Future Ahead. Plants 2025, 14, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perla, V.; Holm, D.G.; Jayanty, S.S. Effects of cooking methods on polyphenols, pigments and antioxidant activity in potato tubers. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 45, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.R.; Culley, D.; Yang, C.P.; Durst, R.; Wrolstad, R. Variation of anthocyanin and carotenoid contents and associated antioxidant values in potato breeding lines. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2005, 130, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.R.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstad, R.; De Jong, W. Variability of phytonutrient content of potato in relation to growing location and cooking method. Potato Res. 2008, 51, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcarcel, J.; Reilly, K.; Gaffney, M.; O’Brien, N. Total Carotenoids and l-Ascorbic Acid Content in 60 Varieties of Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Grown in Ireland. Potato Res. 2015, 58, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystkowska, I.; Zarzecka, K.; Gugała, M.; Ginter, A. Changes in the content of carotenoids in edible potato cultivated with the application of biostimulants and herbicide. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2023, 63, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouz, K.; Pazderů, K.; Lachman, J.; Čepl, J.; Kotíková, Z. Effect of cultivar, flesh colour, locality and year on carotenoid content in potato tubers. Plant Soil Environ. 2016, 62, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar-Cepeda, F.A.; Parra-Galindo, M.A.; Urquijo, J.; Restrepo-Sánchez, L.P.; Mosquera-Vásquez, T.; Narváez-Cuenca, C.E. Influence of genotype, agro-climatic conditions, cooking method, and their interactions on individual carotenoids and hydroxycinnamic acids contents in tubers of diploid potatoes. Food Chem. 2019, 288, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitkevičienė, N.; Kulaitienė, J.; Jarienė, E.; Levickienė, D.; Danillčenko, H.; Średnicka-Tober, D.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Hallmann, E. Characterization of Bioactive Compounds in Colored Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Cultivars Grown with Conventional, Organic, and Biodynamic Methods. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.W.; Dale, M.F.; Morris, W.L.; Ramsay, G. Effects of season and postharvest storage on the carotenoid content of Solanum phureja potato tubers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, C.M.; Schafleitner, R.; Guignard, C.; Oufir, M.; Aliaga, C.A.; Nomberto, G.; Hoffmann, L.; Hausman, J.F.; Evers, D.; Larondelle, Y. Modification of the health-promoting value of potato tubers field grown under drought stress: Emphasis on dietary antioxidant and glycoalkaloid contents in five native andean cultivars (Solanum tuberosum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.; Morris, W.L.; Mortimer, C.L.; Misawa, N.; Ducreux, L.J.; Morris, J.A.; Hedley, P.E.; Fraser, P.D.; Taylor, M.A. Optimising ketocarotenoid production in potato tubers: Effect of genetic background, transgene combinations and environment. Plant Sci. 2015, 234, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, W.L.; Ducreux, L.; Griffiths, D.W.; Stewart, D.; Davies, H.V.; Taylor, M.A. Carotenogenesis during tuber development and storage in potato. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgórska, K.; Czerko, Z.; Grudzińska, M. The Effect of Light Exposure on Greening and Accumulation of Chlorophyll & Glycoalkaloids in Potato Tubers. Food Sci.–Technol.–Qual. 2006, 13, 222–228. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Tanios, S.; Eyles, A.; Tegg, R.; Wilson, C. Potato Tuber Greening: A Review of Predisposing Factors, Management and Future Challenges. Am. J. Potato Res. 2018, 95, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluszczyńska, D. Toxic substances in potato plant. Technol. Prog. Food Process. 2009, 2, 98–102. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Hara, P. Effect of the application of biostimulators under controlled conditions on selected biochemical characteristics of potato plants. Ziemn. Pol. 2020, 4, 3–8. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Yang, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Cao, S.; Shi, L. The changes in chlorophyll, solanine, and phytohormones during light-induced greening in postharvest potatoes. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 219, 113291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairfana, I.; Nikmatullah, A.; Sarjan, M. Tuber and Organoleptic Characteristics of Four Potato Varieties Grown Off-season in Sajang Village, Sembalun. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 913, 012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikundi, E.N.; Buzera, A.; Orina, I.; Sila, D. Impact of the Temperature Reconditioning of Cold-Stored Potatoes on the Color of Potato Chips and French Fries. Foods 2024, 13, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniołowska, M.; Kita, A. Effect of frying temperature and the degree of degradation of the frying medium on the quality of potato chips. Bull. Plant Breed. Acclim. Inst. 2014, 272, 63–72. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Mamo, T. Nutritional and sensory property of chips made from Potato (ST). Adv. Res. 2008, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzińska, M.; Zgórska, K. Effect of S-carvone applied as natural inhibitor of potato sprouts on colour brightness of potato chips. Food Sci. Technol. Qual. 2013, 4, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathuria, D.; Gautam, S.; Thakur, A. Maillard reaction in different food products: Effect on product quality, human health and mitigation strategies. Food Control 2023, 153, 109911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Achaerandio, I.; Pujolà, M. Influence of the frying process and potato cultivar on acrylamide formation in French fries. Food Control 2016, 62, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzińska, M.; Czerko, Z.; Jankowska, J. Changes of dry matter and starch content in potato tubers during storage and their influence on weight losses of raw material in chips frying process. Inż. Ap. Chem. 2015, 54, 243–246. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Mozolewski, W.; Wieczorek, J.; Pomianowski, J.F. Sensory analysis of salted potato chips. Inż. Ap. Chem. 2011, 50, 53–54. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Pyryt, B.; Rybicka, J. Quality Assessment Of Selected Potato Crisps Available For Retail Sale. Sci. J. Gdyn. Marit. Univ. 2017, 99, 141–148. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

| Growing Season | pH | Corg (g kg−1) | Available Macroelements (mg kg−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | K | Mg | |||

| 2023 | 5.9 | 10.0 | 115.54 | 16.85 | 39 |

| Month | Decade | Monthly Average | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | ||

| Mean Daily Air Temperature (°C) | ||||

| May | 8.8 | 12.1 | 14.2 | 11.8 |

| June | 15.7 | 16.2 | 18.4 | 16.8 |

| July | 17.8 | 18.7 | 17.2 | 17.9 |

| August | 17.3 | 19.9 | 18.3 | 18.5 |

| September | 16.7 | 16.2 | 16.1 | 16.3 |

| Average | 16.3 | |||

| Month | Decade | Monthly Sum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | ||

| Total Monthly Precipitation (mm) | ||||

| May | 0.0 | 16.3 | 0.0 | 16.3 |

| June | 0.0 | 20.1 | 28.8 | 48.9 |

| July | 1.4 | 9.7 | 22.9 | 34.0 |

| August | 64.3 | 1.6 | 65.8 | 131.7 |

| September | 0.0 | 9.0 | 14.2 | 23.2 |

| Total precipitation during the growing season | 254.1 | |||

| Variety | Dry Matter [%] | Starch [% f.m.] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 4 | AH * | AS ** | Average | AH | AS | Average | |

| BEO | CL | 23.7 ± 0.3 | 23.4 ± 0.3 | 23.6 ± 0.4 | 18.1 ± 0.4 | 17.8 ± 0.4 | 18.0 ± 0.4 |

| MC | 24.0 ± 0.5 | 23.8 ± 0.4 | 23.9 ± 0.5 | 18.7 ± 0.5 | 18.3 ± 0.4 | 18.5 ± 0.5 | |

| SP | 23.8 ± 0.3 | 23.6 ± 0.5 | 23.7 ± 0.5 | 18.3 ± 0.4 | 18.1 ± 0.5 | 18.2 ± 0.4 | |

| MC + SP | 24.3 ± 0.4 | 24.0 ± 0.4 | 24.2 ± 0.4 | 19.2 ± 0.4 | 18.7 ± 0.6 | 18.9 ± 0.5 | |

| Average 5 | 24.0 ± 0.5 | 23.7 ± 0.5 | 23.9 ± 0.5 | 18.6 ± 0.6 | 18.3 ± 0.5 | 18.4 ± 0.6 | |

| PICUS | CL | 23.6 ± 0.2 | 23.3 ± 0.5 | 23.4 ± 0.5 | 17.8 ± 0.2 | 17.3 ± 0.2 | 17.6 ± 0.3 |

| MC | 24.1 ± 0.3 | 23.6 ± 0.4 | 23.9 ± 0.4 | 18.4 ± 0.3 | 17.9 ± 0.2 | 18.1 ± 0.4 | |

| SP | 23.9 ± 0.3 | 23.4 ± 0.4 | 23.6 ± 0.4 | 18.1 ± 0.2 | 17.6 ± 0.2 | 17.8 ± 0.3 | |

| MC + SP | 24.2 ± 0.3 | 23.8 ± 0.4 | 24.0 ± 0.5 | 18.9 ± 0.3 | 18.4 ± 0.2 | 18.7 ± 0.3 | |

| Average | 23.9 ± 0.5 | 23.6 ± 0.4 | 23.8 ± 0.5 | 18.3 ± 0.5 | 17.8 ± 0.5 | 18.1 ± 0.5 | |

| PIROL | CL | 23.3 ± 0.4 | 22.9 ± 0.3 | 23.1 ± 0.4 | 16.9 ± 0.1 | 16.5 ± 0.2 | 16.7 ± 0.3 |

| MC | 23.7 ± 0.5 | 23.3 ± 0.4 | 23.5 ± 0.5 | 17.8 ± 0.4 | 17.5 ± 0.4 | 17.7 ± 0.4 | |

| SP | 23.5 ± 0.3 | 23.1 ± 0.3 | 23.3 ± 0.4 | 17.1 ± 0.2 | 16.8 ± 0.2 | 17.0 ± 0.2 | |

| MC + SP | 23.8 ± 0.4 | 23.4 ± 0.4 | 23.6 ± 0.5 | 18.1 ± 0.2 | 17.7 ± 0.3 | 17.9 ± 0.3 | |

| Average | 23.6 ± 0.3 | 23.2 ± 0.5 | 23.4 ± 0.5 | 17.5 ± 0.6 | 17.1 ± 0.5 | 17.3 ± 0.6 | |

| AVERAGES FOR TREATMENTS | CL | 23.5 ± 0.4 | 23.2 ± 0.4 | 23.4 ± 0.4 | 17.6 ± 0.6 | 17.2 ± 0.6 | 17.4 ± 0.7 |

| MC | 24.0 ± 0.4 | 23.6 ± 0.5 | 23.8 ± 0.6 | 18.3 ± 0.5 | 17.9 ± 0.4 | 18.1 ± 0.5 | |

| SP | 23.7 ± 0.6 | 23.4 ± 0.5 | 23.6 ± 0.5 | 17.8 ± 0.7 | 17.5 ± 0.6 | 17.7 ± 0.6 | |

| MC + SP | 24.1 ± 0.5 | 23.7 ± 0.6 | 23.9 ± 0.5 | 18.7 ± 0.5 | 18.3 ± 0.5 | 18.5 ± 0.6 | |

| AVERAGE FOR THE EXPERIMENT | 23.8 ± 0.5 | 23.5 ± 0.5 | 23.7 ± 0.5 | 18.0 ± 0.7 | 17.7 ± 0.8 | 17.9 ± 0.7 | |

| LSD 1 α = 0.05 | A 2 = 0.197 B = 0.221 C = 0.085 B/A = N.S. 3 A/B = N.S. C/A = N.S. A/C = N.S. C/B = N.S. B/C = N.S. | A = 0.095 B = 0.230 C = 0.080 B/A = N.S. A/B = N.S. C/A = N.S. A/C = N.S. C/B = 0.139 B/C = 0.259 | |||||

| Parameters | Dry Matter | Starch | Total Sugars | Reducing Sugars | Ctot | Chla | Chlb | Chltot | Color of Chips | Taste of Chips | Consistency of Chips |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch | ** 0.794 | ||||||||||

| Total sugars | ** −0.697 | ** −0.681 | |||||||||

| Reducing sugars | ** −0.649 | ** −0.637 | ** 0.894 | ||||||||

| Ctot | n.s. 1 | ** −0.485 | ** 0.544 | ** 0.539 | |||||||

| Chla | n.s. | ** −0.551 | * 0.370 | ** 0.555 | n.s. | ||||||

| Chlb | n.s. | ** −0.604 | * 0.378 | ** 0.553 | n.s. | ** 0.837 | |||||

| Chltot | n.s. | ** −0.589 | * 0.386 | ** 0.575 | n.s. | ** 0.983 | ** 0.923 | ||||

| Color of chips | ** 0.535 | ** 0.745 | ** −0.745 | ** −0.808 | ** −0.650 | ** −0.481 | ** −0.451 | ** −0.488 | |||

| Taste of chips | ** 0.591 | ** 0.743 | ** −0.720 | ** −0.752 | * −0.424 | ** −0.533 | ** −0.501 | ** −0.541 | ** 0.712 | ||

| Aroma of chips | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Consistency of chips | ** 0.621 | ** 0.719 | ** −0.787 | ** −0.748 | ** −0.708 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ** 0.736 | ** 0.885 | n.s. |

| Total quality of chips | ** 0.653 | ** 0.827 | ** −0.841 | ** −0.865 | ** −0.657 | ** −0.499 | ** −0.472 | ** −0.501 | ** 0.918 | ** 0.613 | ** 0.864 |

| Parameters | Dry Matter | Starch | Total Sugars | Reducing Sugars | Ctot | Chla | Chlb | Chltot | Color of Chips | Taste of Chips | Consistency of Chips |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch | ** 0.822 | ||||||||||

| Total sugars | ** −0.573 | ** −0.700 | |||||||||

| Reducing sugars | ** −0.605 | ** −0.647 | ** 0.888 | ||||||||

| Ctot | * −0.428 | ** −0.512 | ** 0.746 | ** 0.529 | |||||||

| Chla | n.s. 1 | ** −0.453 | * 0.336 | ** 0.528 | n.s. | ||||||

| Chlb | n.s. | ** −0.476 | * 0.336 | ** 0.494 | n.s. | ** 0.849 | |||||

| Chltot | n.s. | ** −0.475 | ** 0.347 | ** 0.535 | n.s. | ** 0.987 | ** 0.924 | ||||

| Color of chips | ** 0.498 | ** 0.614 | ** −0.658 | ** −0.627 | ** −0.559 | * −0.371 | ** −0.452 | * −0.408 | |||

| Taste of chips | ** 0.571 | ** 0.709 | ** −0.676 | ** −0.710 | * −0.382 | ** −0.468 | ** −0.481 | ** −0.487 | ** 0.505 | ||

| Aroma of chips | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |

| Consistency of chips | ** 0.579 | ** 0.695 | ** −0.737 | ** −0.679 | * −0.521 | * −0.341 | n.s. | * −0.345 | ** 0.466 | ** 0.513 | n.s. |

| Total quality of chips | ** 0.675 | ** 0.828 | ** −0.843 | ** −0.827 | * −0.584 | −0.489 | ** −0.517 | ** −0.514 | ** 0.783 | ** 0.861 | ** 0.794 |

| Variety | Total Sugars [g kg−1 f.m.] | Reducing Sugars [mg kg−1 f.m.] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 4 | AH * | AS ** | Average | AH | AS | Average | |

| BEO | CL | 5.89 ± 0.3 | 6.25 ± 0.2 | 6.07 ± 0.2 | 492 ± 81. | 544 ± 33 | 518 ± 67 |

| MC | 5.49 ± 0.3 | 5.83 ± 0.1 | 5.66 ± 0.2 | 421 ± 53 | 444 ± 83 | 433 ± 64 | |

| SP | 5.63 ± 0.3 | 5.97 ± 0.1 | 5.80 ± 0.3 | 454 ± 76 | 508 ± 33 | 481 ± 63 | |

| MC + SP | 5.36 ± 0.3 | 5.72 ± 0.1 | 5.54 ± 0.2 | 381 ± 62 | 428 ± 46 | 405 ± 55 | |

| Average 5 | 5.59 ± 0.2 | 5.94 ± 0.2 | 5.77 ± 0.3 | 437 ± 6 | 481 ± 80 | 459 ± 73 | |

| PICUS | CL | 6.40 ± 0.3 | 6.77 ± 0.1 | 6.59 ± 0.3 | 602 ± 55 | 646 ± 48 | 624 ± 51 |

| MC | 5.99 ± 0.4 | 6.43 ± 0.2 | 6.21 ± 0.2 | 429 ± 64 | 492 ± 45 | 461 ± 54 | |

| SP | 6.25 ± 0.3 | 6.61 ± 0.1 | 6.43 ± 0.3 | 496 ± 56 | 543 ± 42 | 520 ± 50 | |

| MC + SP | 5.72 ± 0.3 | 6.16 ± 0.0 | 5.94 ± 0.3 | 367 ± 52 | 420 ± 41 | 394 ± 47 | |

| Average | 6.09 ± 0.3 | 6.49 ± 0.3 | 6.29 ± 0.4 | 473 ± 97 | 525 ± 97 | 499 ± 99 | |

| PIROL | CL | 6.60 ± 0.4 | 7.03 ± 0.1 | 6.82 ± 0.3 | 720 ± 76 | 777 ± 52 | 749 ± 67 |

| MC | 6.36 ± 0.3 | 6.78 ± 0.1 | 6.57 ± 0.1 | 618 ± 48 | 657 ± 34 | 638 ± 42 | |

| SP | 6.50 ± 0.4 | 6.88 ± 0.3 | 6.69 ± 0.3 | 678 ± 50 | 729 ± 39 | 704 ± 47 | |

| MC + SP | 6.21 ± 0.3 | 6.59 ± 0.1 | 6.40 ± 0.2 | 533 ± 82 | 581 ± 51 | 557 ± 74 | |

| Average | 6.42 ± 0.2 | 6.82 ± 0.2 | 6.62 ± 0.3 | 641 ± 89 | 686 ± 93 | 664 ± 92 | |

| AVERAGES FOR TREATMENTS | CL | 6.30 ± 0.4 | 6.68 ± 0.4 | 6.29 ± 0.4 | 605 ± 111 | 656 ± 116 | 631 ± 113 |

| MC | 5.95 ± 0.4 | 6.34 ± 0.4 | 6.31 ± 0.5 | 489 ± 101 | 531 ± 113 | 510 ± 106 | |

| SP | 6.13 ± 0.5 | 6.48 ± 0.4 | 6.49 ± 0.6 | 543 ± 111 | 594 ± 113 | 569 ± 112 | |

| MC + SP | 5.77 ± 0.4 | 6.16 ± 0.4 | 6.15 ± 0.4 | 427 ± 93 | 476 ± 96 | 452 ± 95 | |

| AVERAGE FOR THE EXPERIMENT | 6.03 ± 0.5 | 6.42 ± 0.4 | 6.23 ± 0.5 | 516 ± 129 | 564 ± 125 | 540 ± 124 | |

| LSD 1 α = 0.05 | A 2 = 0.046 B = 0.057 C = 0.039 B/A = N.S. 3 A/B = N.S. C/A = N.S. A/C = N.S. C/B = 0.067 B/C = 0.081 | A = 43.46 B = 21.14 C = 15.45 B/A = N.S. A/B = N.S. C/A = N.S. A/C = N.S. C/B = 26.76 B/C = 31.35 | |||||

| Variety | Ctot [mg kg −1 f.m.] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 4 | AH * | AS ** | Average | |

| BEO | CL | 7.29 ± 0.06 | 7.05 ± 0.09 | 7.17 ± 0.15 |

| MC | 7.70 ± 0.12 | 7.55 ± 0.19 | 7.63 ± 0.19 | |

| SP | 7.45 ± 0.09 | 7.21 ± 0.11 | 7.33 ± 0.17 | |

| MC + SP | 7.90 ± 0.08 | 7.73 ± 0.07 | 7.82 ± 0.12 | |

| Average 5 | 7.58 ± 0.26 | 7.39 ± 0.31 | 7.49 ± 0.30 | |

| PICUS | CL | 9.28 ± 0.61 | 9.05 ± 0.65 | 9.17 ± 0.69 |

| MC | 9.53 ± 0.55 | 9.37 ± 0.54 | 9.45 ± 0.58 | |

| SP | 9.48 ± 0.57 | 9.30 ± 0.54 | 9.39 ± 0.59 | |

| MC + SP | 9.75 ± 0.61 | 9.56 ± 0.59 | 9.66 ± 0.66 | |

| Average | 9.51 ± 0.62 | 9.32 ± 0.62 | 9.42 ± 0.61 | |

| PIROL | CL | 10.09 ± 0.22 | 9.71 ± 0.15 | 9.90 ± 0.29 |

| MC | 10.60 ± 0.20 | 10.33 ± 0.26 | 10.47 ± 0.29 | |

| SP | 10.17 ± 0.16 | 9.92 ± 0.13 | 10.05 ± 0.20 | |

| MC + SP | 10.87 ± 0.18 | 10.72 ± 0.12 | 10.80 ± 0.19 | |

| Average | 10.43 ± 0.39 | 10.19 ± 0.44 | 10.31 ± 0.43 | |

| AVERAGES FOR TREATMENTS | CL | 8.88 ± 1.30 | 8.60 ± 1.26 | 8.74 ± 1.25 |

| MC | 9.28 ± 1.32 | 9.09 ± 1.28 | 9.19 ± 1.27 | |

| SP | 9.03 ± 1.27 | 8.81 ± 1.27 | 8.92 ± 1.24 | |

| MC + SP | 9.50 ± 1.36 | 9.33 ± 1.38 | 9.42 ± 1.32 | |

| AVERAGE FOR THE EXPERIMENT | 9.17 ± 1.27 | 8.96 ± 1.23 | 9.07 ± 1.27 | |

| LSD 1 α = 0.05 | A 2 = 0.054 B = 0.522 C = 0.074 B/A = N.S. 3 A/B = N.S. C/A = N.S. A/C = N.S. C/B = 0.128 B/C = 0.534 | |||

| Variety | Chla [mg kg−1 f.m.] | Chlb [mg kg−1 f.m.] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 4 | AH * | AS ** | Average | AH | AS | Average | |

| BEO | CL | 1.93 ± 0.05 | 1.85 ± 0.06 | 1.89 ± 0.07 | 0.969 ± 0.034 | 0.913 ± 0.000 | 0.941 ± 0.031 |

| MC | 1.87 ± 0.03 | 1.8 ± 0.02 | 1.84 ± 0.05 | 0.938 ± 0.039 | 0.886 ± 0.000 | 0.912 ± 0.031 | |

| SP | 1.80 ± 0.07 | 1.72 ± 0.04 | 1.76 ± 0.08 | 0.909 ± 0.033 | 0.865 ± 0.001 | 0.887 ± 0.026 | |

| MC + SP | 1.75 ± 0.05 | 1.69 ± 0.03 | 1.72 ± 0.05 | 0.889 ± 0.031 | 0.841 ± 0.002 | 0.865 ± 0.027 | |

| Average 5 | 1.84 ± 0.08 | 1.77 ± 0.08 | 1.81 ± 0.09 | 0.926 ± 0.033 | 0.876 ± 0.029 | 0.901 ± 0.040 | |

| PICUS | CL | 1.85 ± 0.04 | 1.78 ± 0.03 | 1.82 ± 0.06 | 0.918 ± 0.075 | 0.871 ± 0.004 | 0.895 ± 0.060 |

| MC | 1.8 ± 0.05 | 1.73 ± 0.03 | 1.77 ± 0.06 | 0.922 ± 0.031 | 0.877 ± 0.014 | 0.900 ± 0.027 | |

| SP | 1.73 ± 0.05 | 1.66 ± 0.02 | 1.70 ± 0.06 | 0.896 ± 0.030 | 0.851 ± 0.004 | 0.874 ± 0.026 | |

| MC + SP | 1.67 ± 0.05 | 1.6 ± 0.03 | 1.64 ± 0.05 | 0.862 ± 0.024 | 0.827 ± 0.008 | 0.845 ± 0.021 | |

| Average | 1.76 ± 0.08 | 1.69 ± 0.08 | 1.73 ± 0.09 | 0.900 ± 0.038 | 0.857 ± 0.033 | 0.879 ± 0.041 | |

| PIROL | CL | 1.97 ± 0.04 | 1.89 ± 0.02 | 1.93 ± 0.05 | 1.029 ± 0.046 | 0.960 ± 0.017 | 0.995 ± 0.041 |

| MC | 1.94 ± 0.04 | 1.88 ± 0.04 | 1.91 ± 0.05 | 0.947 ± 0.028 | 0.909 ± 0.09 | 0.928 ± 0.023 | |

| SP | 1.88 ± 0.03 | 1.81 ± 0.01 | 1.85 ± 0.05 | 0.937 ± 0.041 | 0.886 ± 0.014 | 0.912 ± 0.032 | |

| MC + SP | 1.84 ± 0.04 | 1.75 ± 0.04 | 1.80 ± 0.05 | 0.902 ± 0.038 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.871 ± 0.034 | |

| Average | 1.91 ± 0.06 | 1.83 ± 0.07 | 1.87 ± 0.08 | 0.954 ± 0.049 | 0.899 ± 0.047 | 0.927 ± 0.055 | |

| AVERAGES FOR TREATMENTS | CL | 1.92 ± 0.06 | 1.84 ± 0.06 | 1.88 ± 0.07 | 0.972 ± 0.058 | 0.915 ± 0.049 | 0.944 ± 0.060 |

| MC | 1.87 ± 0.07 | 1.8 ± 0.07 | 1.84 ± 0.08 | 0.936 ± 0.0123 | 0.891 ± 0.020 | 0.914 ± 0.028 | |

| SP | 1.81 ± 0.08 | 1.73 ± 0.08 | 1.77 ± 0.09 | 0.914 ± 0.020 | 0.867 ± 0.020 | 0.891 ± 0.031 | |

| MC + SP | 1.75 ± 0.08 | 1.68 ± 0.07 | 1.72 ± 0.08 | 0.884 ± 0.020 | 0.836 ± 0.010 | 0.860 ± 0.029 | |

| AVERAGE FOR THE EXPERIMENT | 1.84 ± 0.11 | 1.76 ± 0.09 | 1.80 ± 0.10 | 0.927 ± 0.054 | 0.877 ± 0.039 | 0.902 ± 0.050 | |

| 1 LSD α = 0.05 | A 2 = 0.008 B = 0.014 C = 0.016 B/A = N.S. 3 A/B = N.S. C/A = N.S. A/C = N.S. C/B = 0.028 B/C = 0.028 | A = 0.007 B = 0.012 C = 0.015 B/A = N.S. A/B = N.S. C/A = N.S. A/C = N.S. C/B = 0.025 B/C = 0.025 | |||||

| Variety | Chltot [mg kg−1 f.m.] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 4 | AH * | AS ** | Average | |

| BEO | CL | 2.90 ± 0.12 | 2.76 ± 0.05 | 2.83 ± 0.09 |

| MC | 2.81 ± 0.11 | 2.69 ± 0.02 | 2.75 ± 0.08 | |

| SP | 2.71 ± 0.14 | 2.59 ± 0.04 | 2.65 ± 0.11 | |

| MC + SP | 2.64 ± 0.10 | 2.53 ± 0.03 | 2.59 ± 0.08 | |

| Average 5 | 2.76 ± 0.12 | 2.64 ± 0.11 | 2.70 ± 0.13 | |

| PICUS | CL | 2.77 ± 0.15 | 2.65 ± 0.03 | 2.71 ± 0.11 |

| MC | 2.72 ± 0.11 | 2.61 ± 0.04 | 2.67 ± 0.08 | |

| SP | 2.63 ± 0.11 | 2.51 ± 0.03 | 2.57 ± 0.08 | |

| MC + SP | 2.53 ± 0.07 | 2.43 ± 0.01 | 2.48 ± 0.06 | |

| Average | 2.66 ± 0.11 | 2.55 ± 0.13 | 2.61 ± 0.11 | |

| PIROL | CL | 3.00 ± 0.12 | 2.85 ± 0.03 | 2.93 ± 0.09 |

| MC | 2.89 ± 0.09 | 2.78 ± 0.05 | 2.84 ± 0.07 | |

| SP | 2.82 ± 0.12 | 2.69 ± 0.02 | 2.76 ± 0.08 | |

| MC + SP | 2.74 ± 0.11 | 2.59 ± 0.04 | 2.67 ± 0.09 | |

| Average | 2.86 ± 0.11 | 2.72 ± 0.13 | 2.80 ± 0.11 | |

| AVERAGES FOR TREATMENTS | CL | 2.89 ± 0.12 | 2.76 ± 0.11 | 2.83 ± 0.13 |

| MC | 2.80 ± 0.08 | 2.69 ± 0.09 | 2.75 ± 0.10 | |

| SP | 2.72 ± 0.10 | 2.60 ± 0.10 | 2.66 ± 0.12 | |

| MC + SP | 2.63 ± 0.10 | 2.52 ± 0.08 | 2.58 ± 0.11 | |

| AVERAGE FOR THE EXPERIMENT | 2.76 ± 0.16 | 2.64 ± 0.13 | 2.70 ± 0.15 | |

| LSD 1 α = 0.05 | A 2 = 0.012 B = 0.013 C = 0.022 B/A = N.S. 3 A/B = N.S. C/A= 0.031 A/C = 0.029 C/B = N.S. B/C = N.S. | |||

| Variety | Total Sensory Quality [5-Point Scale] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 4 | AH * | AS ** | Average | |

| BEO | CL | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.0 | 4.6 ± 0.2 |

| MC | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | |

| SP | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | |

| MC + SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 4.8 ± 0.0 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | |

| Average 5 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | |

| PICUS | CL | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.1 |

| MC | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | |

| SP | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | |

| MC + SP | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | |

| Average | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | |

| PIROL | CL | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.2 |

| MC | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | |

| SP | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | |

| MC + SP | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.0 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | |

| Average | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | |

| AVERAGES FOR TREATMENTS | CL | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.3 |

| MC | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | |

| SP | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | |

| MC + SP | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | |

| AVERAGE FOR THE EXPERIMENT | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | |

| LSD 1 α = 0.05 | A 2 = 0.080 B = 0.055 C = 0.066 B/A = N.S. 3 A/B = N.S. C/A =N.S. A/C =N.S. C/B = 0.114 B/C = 0.113 | |||

| Variety | COLOR [5-Point Scale] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 4 | AH * | AS ** | Average | |

| BEO | CL | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.2 |

| MC | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | |

| SP | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | |

| MC + SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | |

| Average 5 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | |

| PICUS | CL | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.2 |

| MC | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | |

| SP | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | |

| MC + SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 4.7 ± 0.0 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | |

| Average | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | |

| PIROL | CL | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| MC | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | |

| SP | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.0 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | |

| MC + SP | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.0 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | |

| Average | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | |

| AVERAGES FOR TREATMENTS | CL | 4.5 ± 3.1 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.6 |

| MC | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | |

| SP | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | |

| MC + SP | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | |

| AVERAGE FOR THE EXPERIMENT | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | |

| LSD 1 α = 0.05 | A 2 = N.S. B = 0.108 C = 0.154 B/A = N.S. 3 A/B = N.S. C/A = N.S. A/C = N.S. C/B = 0.267 B/C = 0.255 | |||

| Variety | Consistency [5-Point Scale] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 4 | AH * | AS ** | Average | |

| BEO | CL | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.0 | 4.5 ± 0.3 |

| MC | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | |

| SP | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | |

| MC + SP | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | |

| Average 5 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | |

| PICUS | CL | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.2 |

| MC | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | |

| SP | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | |

| MC + SP | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | |

| Average | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | |

| PIROL | CL | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.2 |

| MC | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.0 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | |

| SP | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | |

| MC + SP | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | |

| Average | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | |

| AVERAGES FOR TREATMENTS | CL | 4.3 ± 1.3 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.4 |

| MC | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | |

| SP | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | |

| MC + SP | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | |

| AVERAGE FOR THE EXPERIMENT | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | |

| LSD 1 α = 0.05 | A 2 = 0.210 B = 0.203 C = 0.120 B/A = N.S. 3 A/B = N.S. C/A = 0.169 A/C = 0.249 C/B = 0.207 B/C = 0.271 | |||

| Variety | Taste [5-Point Scale] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 4 | AH * | AS ** | Average | |

| BEO | CL | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.0 | 3.9 ± 0.2 |

| MC | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 0.0 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | |

| SP | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | |

| MC + SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 4.7 ± 0.0 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | |

| Average 5 | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | |

| PICUS | CL | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.2 |

| MC | 4.7 ± 0.0 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | |

| SP | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | |

| MC + SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 4.8 ± 0.0 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | |

| Average | 4.7 ± 0.2 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | |

| PIROL | CL | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.0 | 3.5 ± 0.3 |

| MC | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | |

| SP | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | |

| MC + SP | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | |

| Average | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | |

| AVERAGES FOR TREATMENTS | CL | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 3.8 ± 2.5 | 3.9 ± 0.5 |

| MC | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | |

| SP | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | |

| MC + SP | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | |

| AVERAGE FOR THE EXPERIMENT | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | |

| LSD 1 α = 0.05 | A 2 = 0.156 B = 0.090 C = 0.146 B/A = N.S. 3 A/B = N.S. C/A = N.S. A/C = N.S. C/B = 0.252 B/C = 0.236 | |||

| Variety | Aroma [5-Point Scale] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment 4 | AH * | AS ** | Average | |

| BEO | CL | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| MC | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| MC + SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| Average 5 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| PICUS | CL | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| MC | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| MC + SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| Average | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| PIROL | CL | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| MC | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| MC + SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| Average | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| AVERAGES FOR TREATMENTS | CL | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| MC | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| MC + SP | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| AVERAGE FOR THE EXPERIMENT | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | |

| LSD 1 α = 0.05 | A 2 = N.S. 3 B = N.S. C = N.S. B/A = N.S. A/B = N.S. C/A = N.S. A/C = N.S. C/B = N.S. B/C = N.S. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Brążkiewicz, K.; Wszelaczyńska, E.; Bogucka, B.; Pobereżny, J. The Effect of Potato Seed Treatment on the Chemical Composition of Tubers and the Processing Quality of Chips Assessed Immediately After Harvest and After Long-Term Storage of Tubers. Agriculture 2026, 16, 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020199

Brążkiewicz K, Wszelaczyńska E, Bogucka B, Pobereżny J. The Effect of Potato Seed Treatment on the Chemical Composition of Tubers and the Processing Quality of Chips Assessed Immediately After Harvest and After Long-Term Storage of Tubers. Agriculture. 2026; 16(2):199. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020199

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrążkiewicz, Katarzyna, Elżbieta Wszelaczyńska, Bożena Bogucka, and Jarosław Pobereżny. 2026. "The Effect of Potato Seed Treatment on the Chemical Composition of Tubers and the Processing Quality of Chips Assessed Immediately After Harvest and After Long-Term Storage of Tubers" Agriculture 16, no. 2: 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020199

APA StyleBrążkiewicz, K., Wszelaczyńska, E., Bogucka, B., & Pobereżny, J. (2026). The Effect of Potato Seed Treatment on the Chemical Composition of Tubers and the Processing Quality of Chips Assessed Immediately After Harvest and After Long-Term Storage of Tubers. Agriculture, 16(2), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020199