1. Introduction

Global warming, ecosystem imbalance, and declining biodiversity pose potential threats to human survival and development [

1]. Against this backdrop, accelerating the transition to a green economy has become a shared choice for the international community [

1,

2,

3]. As an eco-economic industry aligned with China’s strategic development direction and societal needs, the agroforestry economy resonates with global sustainable development trends [

3,

4]. In March 2025, the agroforestry economy was first incorporated into China’s Government Work Report. This signifies an elevation in its developmental positioning—from pilot explorations at the local level to a strategic national-level initiative. According to statistics from the National Forestry and Grassland Administration, by 2024, China’s agroforestry economy had achieved large-scale management and utilization of 40 million hectares of forest land, involving 950,000 operational entities, with an annual output value exceeding 1 trillion yuan [

5]. The sector employs over 34 million people, becoming a distinctive industry boosting income for mountainous forest farmers. However, as economically rational actors, farmers prioritize profit maximization in their operations, often diminishing attention to ecological conservation [

2]. This has triggered a series of negative ecological impacts, including excessive land reclamation, accelerated soil erosion, and damaged surface vegetation. An agroforestry economy can both maintain the stability and health of forest ecosystems and generate economic value by leveraging forest resources. Guided by relevant forest conservation policies, its development has created a positive substitution effect for traditional timber harvesting and processing industries [

6]. Simultaneously, agroforestry management models improve micro-ecological environments, mitigate soil erosion, enhance water retention and soil conservation capabilities, and promote forest resource growth alongside ecological restoration [

7,

8]. Empirical research by Zomer et al. confirms that when agroforestry practices reach an 80% coverage rate, global tree coverage could increase by nearly 8%, significantly enhancing the carbon sequestration capacity of forest ecosystems [

9]. Consequently, conducting an in-depth analysis of the multifaceted drivers and core influencing factors for the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and the ecological environment holds significant practical value for achieving sustainable industrial development.

Agroforestry economy possesses both ecological and economic benefits, driving its growing global prominence. Scholars have conducted in-depth research on this field through diverse perspectives, methodologies, and scales. Regarding the conceptual evolution of the agroforestry economy: Following its establishment in 1978, the International Center for Research in Agroforestry (ICRAF) elevated agroforestry economy from a practical production approach to a systematic theoretical research domain [

8]. ICRAF defined it as: Within a single land management unit, the deliberate integration of perennial woody plants with other cultivated plants and livestock through spatial arrangement or temporal sequencing, forming a composite ecosystem where agriculture and forestry interact ecologically and economically in various combination patterns [

10]. The 1982 launch of the international journal Agroforestry Systems marked the maturation of global agroforestry research [

2]. In 2011, the U.S. Department of Agriculture explicitly stated that agroforestry systems hold significant importance for the nation’s agricultural and forestry economic development and ecological conservation [

8]. In contrast, Chinese scholars began researching the agroforestry economy relatively late. In 1994, Li Wenhua and Lai Shideng published Agroforestry in China, defining it as a systematic management model integrating agriculture and forestry [

10]. Some domestic scholars translate “agroforestry economy” as “under-forest economy,” arguing this term better highlights the multifunctional value of forest resources [

10,

11,

12]. It places greater emphasis on optimizing forest resource allocation, encompassing development models such as agroforestry cultivation, agroforestry animal husbandry, agroforestry gathering, and forest landscape utilization [

5]. Although different countries define agroforestry economy differently at various developmental stages, its core characteristics remain consistent. This study posits that the agroforestry economy is an ecologically friendly economic system grounded in ecology, economics, and systems engineering. It relies on forests, woodlands, and their ecosystems, characterized primarily by integrated management practices. This artificial ecosystem exhibits multiple attributes: polyphyllic symbiosis, multi-product output, synergistic multi-benefits, and sustainable development [

5,

8].

Regarding the environmental impacts of the agroforestry economy. As the agroforestry economy continues to advance and expand in scale, the effects of its development and management activities on ecosystems have gradually become a research hotspot in academia. International scholars have focused their research on the environmental effects of different agroforestry economy development models. Surrounding key ecological dimensions such as soil erosion [

13,

14], soil nutrient cycling [

15,

16,

17], biodiversity maintenance [

18,

19,

20], and atmospheric regulation with carbon sequestration functions [

21,

22,

23,

24]. However, existing studies predominantly employ experimental research methods. Such approaches require strict control over confounding variables beyond independent and dependent variables to ensure the accuracy of research conclusions. The development of an agroforestry economy is fundamentally a market-driven activity encompassing management, production, and consumption. Decision-making behaviors of various stakeholders significantly influence their environmental impacts [

10]. Consequently, some scholars have shifted their focus to exploring the driving pathways and influencing factors for the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment [

25]. For instance, Wu Weiguang et al. constructed an analytical framework based on the Leontief production function and optimal production decision theory, revealing the economic effects, environmental effects, and their synergistic mechanisms of the agroforestry economy [

4]. Hao Lili et al. utilized a coordinated development degree model to measure the coupling level and variation patterns of Heilongjiang’s agroforestry economy with its ecological environment at the micro-scale [

6]. Although relevant research has made some progress, existing findings mostly focus on typical regions such as Jilin [

26], Hunan [

27], and Yunnan [

28]. But research has primarily focused on descriptive analysis, exploring the current characteristics, existing problems, and response strategies for the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment within regions, yet lacking analysis and validation based on empirical data. A few studies have measured and evaluated the level of coordinated development, but there remain significant gaps in exploring the driving pathways of coordinated development and elucidating the theoretical mechanisms.

Regarding advances and applications in research methodologies, current academic studies predominantly rely on micro-level survey data from specific regions. Utilizing quantitative tools such as structural equation modeling [

29], factor analysis [

13,

27], and multiple linear regression [

30,

31], these studies explore the differential driving effects of factors like operational scale, market demand, and policy regulations on the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment. Concurrently, some studies employ case analysis methods, examining drivers and underlying mechanisms from perspectives such as forest farmers’ management philosophies, educational attainment, and behavioral characteristics [

32,

33,

34,

35]. However, it is crucial to note that the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment constitutes a multidimensional, multi-stakeholder complex system process [

36,

37]. A single-factor analytical perspective struggles to comprehensively deconstruct the intrinsic driving mechanisms of this complex system and fails to effectively elucidate the intricate nonlinear interactions among various elements [

8]. Furthermore, traditional regression analysis methods primarily examine the marginal “net effect” of independent variables on dependent variables, exhibiting significant limitations in exploring multiple concurrent causal relationships. Against this backdrop, systematically investigating the diverse driving pathways for the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment under the combined effects of different factors represents a critical gap in the field that urgently requires filling. This research imperative aligns highly with configurational theory grounded in abductive logic. Adopting a holistic analytical perspective, this theory emphasizes that outcomes arise from the synergistic and interdependent interactions of multiple factors, with different combinations of elements potentially yielding equivalent results [

38,

39,

40]. It thus offers a novel research approach to overcome existing research challenges.

In summary, existing research on the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment has accumulated practical reference value, but may still exhibit the following shortcomings: First, the theoretical analysis framework remains immature. Previous studies have largely focused on summarizing experiences from specific cases, failing to establish a theoretical analytical framework that integrates the synergistic effects of multiple factors. This hinders a comprehensive explanation of the interwoven nonlinear mechanisms among various elements. Second, research methodologies exhibit significant limitations. The synergistic development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment possesses pronounced systemic and dynamic characteristics. Existing studies predominantly focus on single-factor-driven linear analysis perspectives, lacking depth in deciphering the concurrent causal relationships among multiple factors. Simultaneously, constrained by specific hypothetical conditions, the issue of endogeneity in research remains difficult to resolve thoroughly. Third, the scope of research requires further expansion. Existing findings show limited exploration of the combined effects of multiple factors and their impact on synergistic development. Few studies have systematically deconstructed the driving mechanisms of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment synergistic development from a multi-case perspective, incorporating configurational analysis concepts.

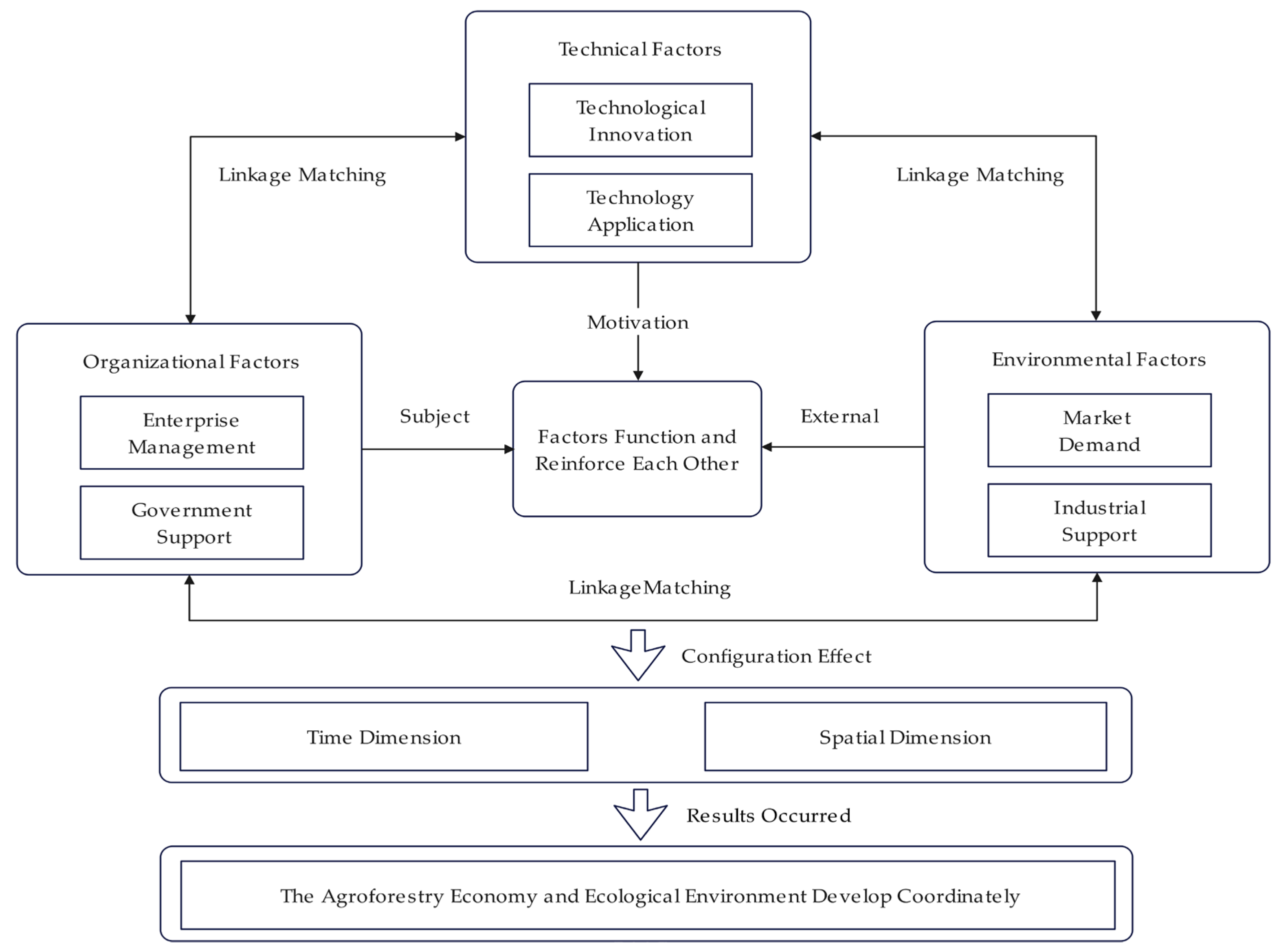

Given this, this study aims to address these research gaps. It provides theoretical foundations and methodological references for analyzing the diverse driving pathways and supporting factors of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment synergistic development. First, this study systematically identifies key factors influencing synergistic development using the TOE theoretical framework. Then, extending the research scope to the provincial level, it employs panel data from China’s 31 provinces covering 2012–2023. By integrating a coordinated development degree model with a hybrid research methodology combining dynamic QCA and NCA, it reveals diverse driving pathways for the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment under multi-factor combination scenarios. Finally, targeted policy recommendations are proposed based on the findings. These aim to provide decision-making references for formulating differentiated coordinated development strategies across regions and promoting the sustainable development of the agroforestry economy.

The potential contributions of this study are as follows: First, at the theoretical level. This research integrates TOE theory with China’s national context, incorporating multiple factors such as technology, organization, and environmental dimensions into the theoretical analytical framework. It not only expands the application scenarios of TOE theory but also focuses on analyzing the nonlinear interactions among various factors in coordinated development, filling the theoretical gap in existing research that has insufficiently addressed the synergistic effects of multiple factors. Second, at the practical level. This study employs a mixed-methods approach, including dynamic QCA and NCA, to conduct integrated qualitative and quantitative analysis based on abductive logic. This methodology not only effectively addresses the endogeneity challenges of traditional regression analysis but also uncovers the diverse driving pathways and complex causal relationships underpinning the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment, thereby compensating for the limitations of current research methods.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

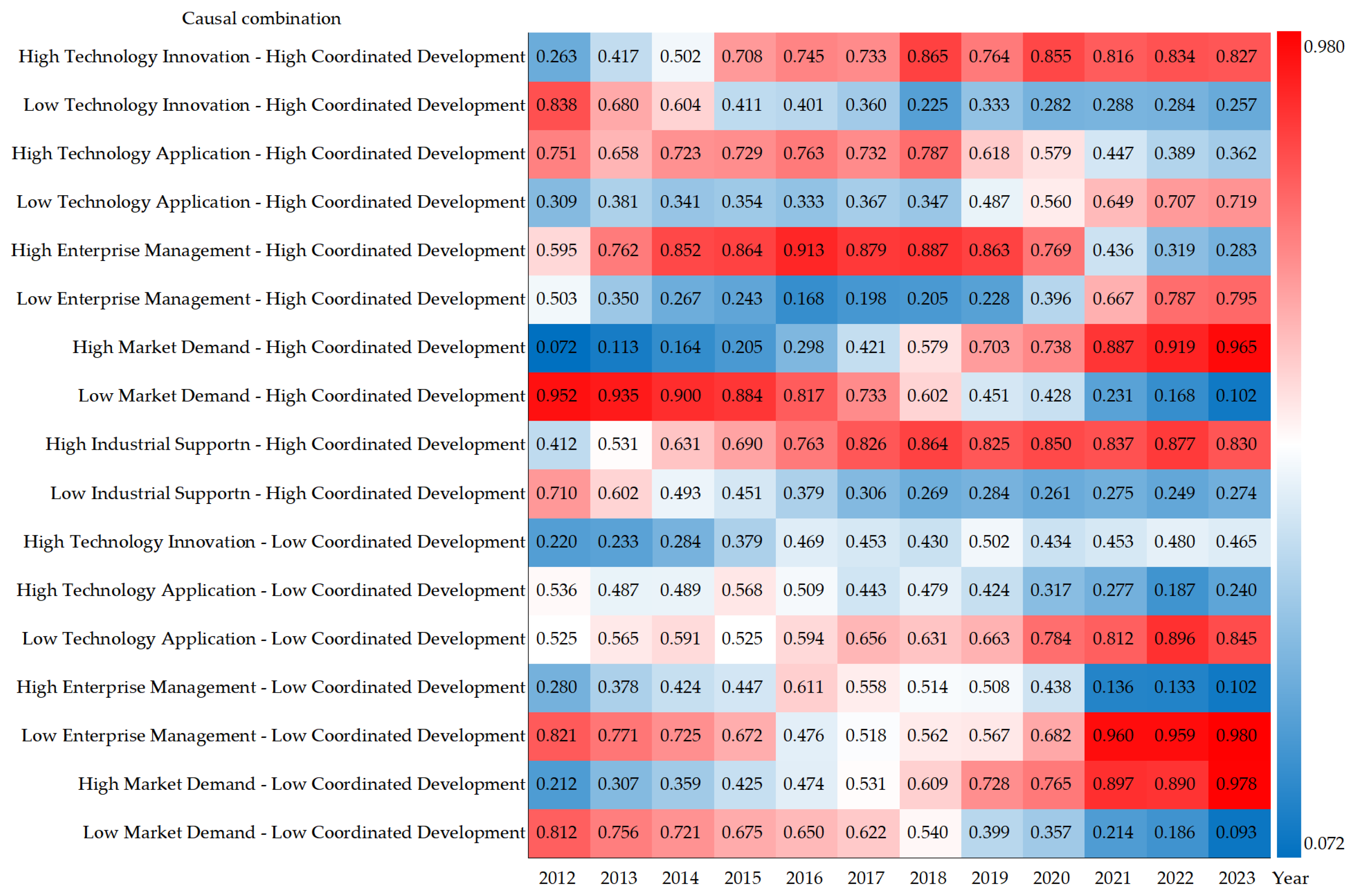

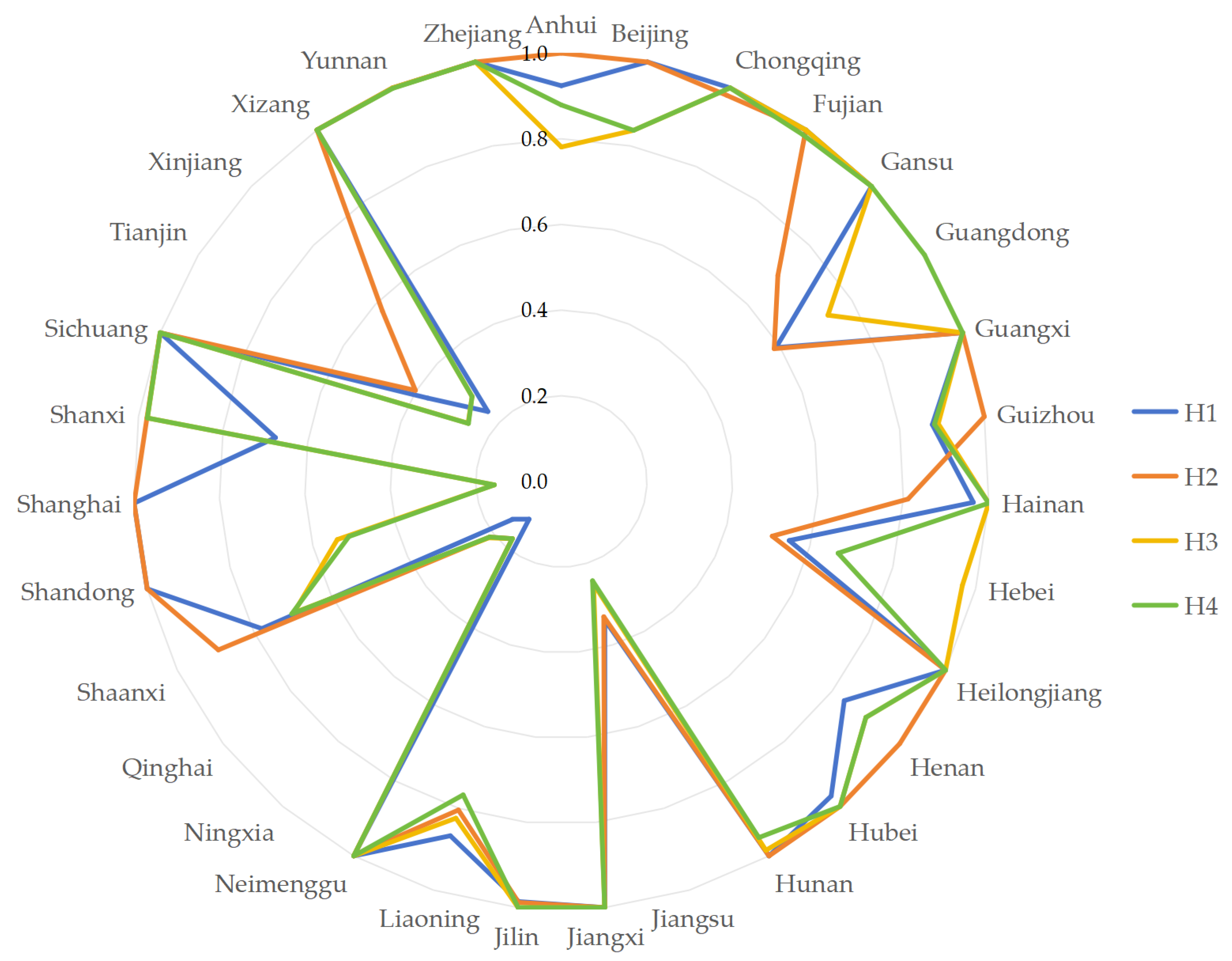

This study, grounded in the TOE theoretical framework and utilizing panel data from China’s 31 provinces spanning 2012–2023, employs a comprehensive approach integrating the coupled coordination model, dynamic qualitative comparative analysis, and necessary condition analysis. It systematically explores the multi-faceted driving mechanisms and implementation pathways for the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment. Key findings are as follows:

First, the analysis of necessary conditions reveals that the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment cannot be sustained by a single factor but rather results from the synergistic interaction of multiple elements, including technology, organization, and environment. Specifically, individual influencing factors such as technological innovation, technology application, enterprise management, government support, market demand, and industrial support are insufficient to constitute the necessary conditions for achieving the outcome. However, the necessity of technological innovation, market demand, and industrial support progressively increases over time, exhibiting a certain time effect. Future efforts focused on enhancing the core competitiveness and supply efficiency of these three factors will have broader universal applicability in elevating the level of coordinated development between the agroforestry economy and the ecological environment.

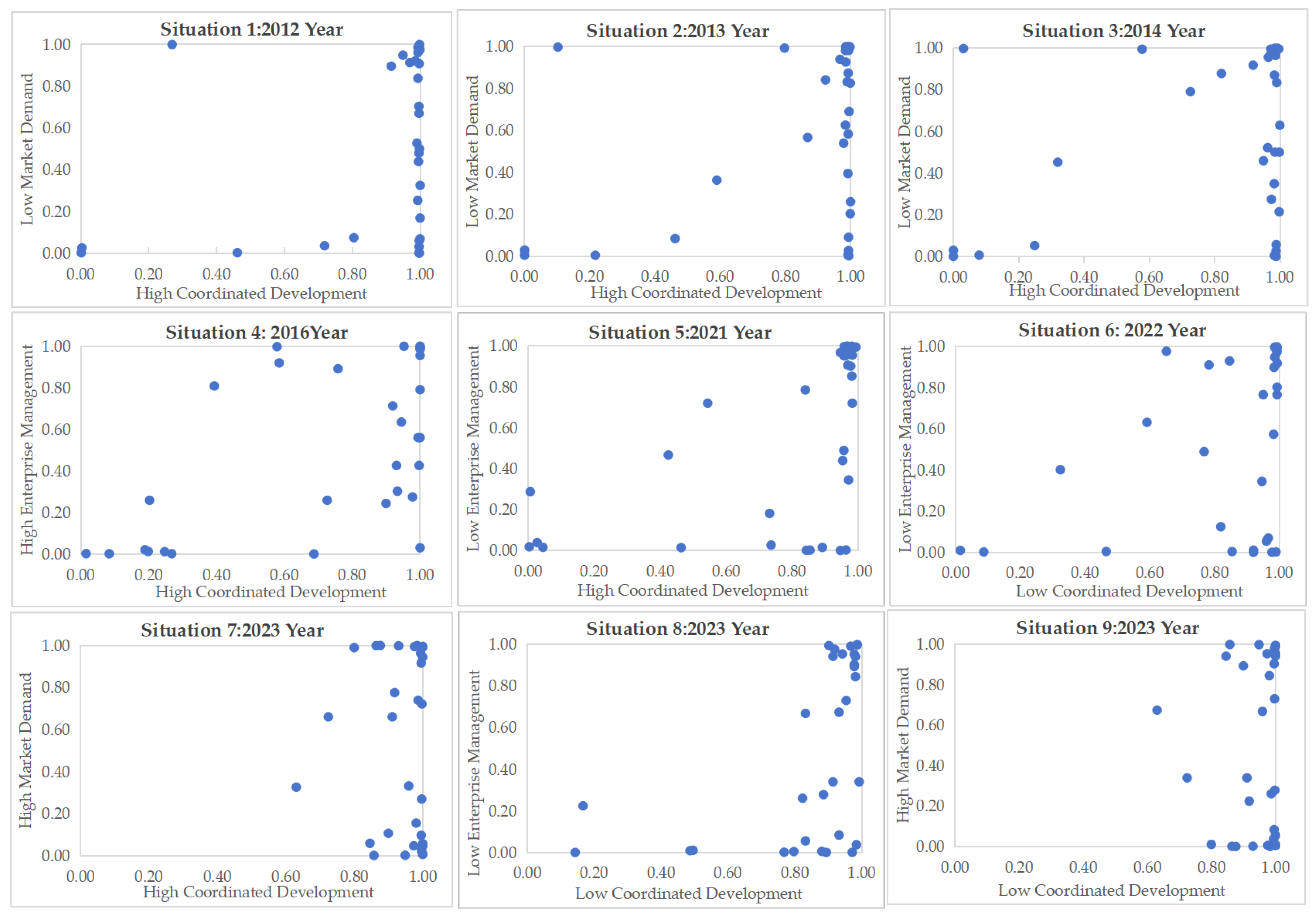

Second, through configurational analysis of conditions, it was found that the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment follows multiple driving pathways, exhibiting a typical “different causes, same effect” phenomenon. Specifically, the study identified four core driving pathways: enterprise operation and industrial support-driven, technology innovation-led, market-pulled factor integration, and government-guided multi-stakeholder collaboration. This finding indicates that no universally optimal model exists for harmonizing agroforestry economy and ecological environment development, as different factors may exhibit substitutability and interactive effects. Therefore, the key to promoting coordinated development lies in flexibly configuring core and peripheral conditions to form an optimal combination of adaptive conditions.

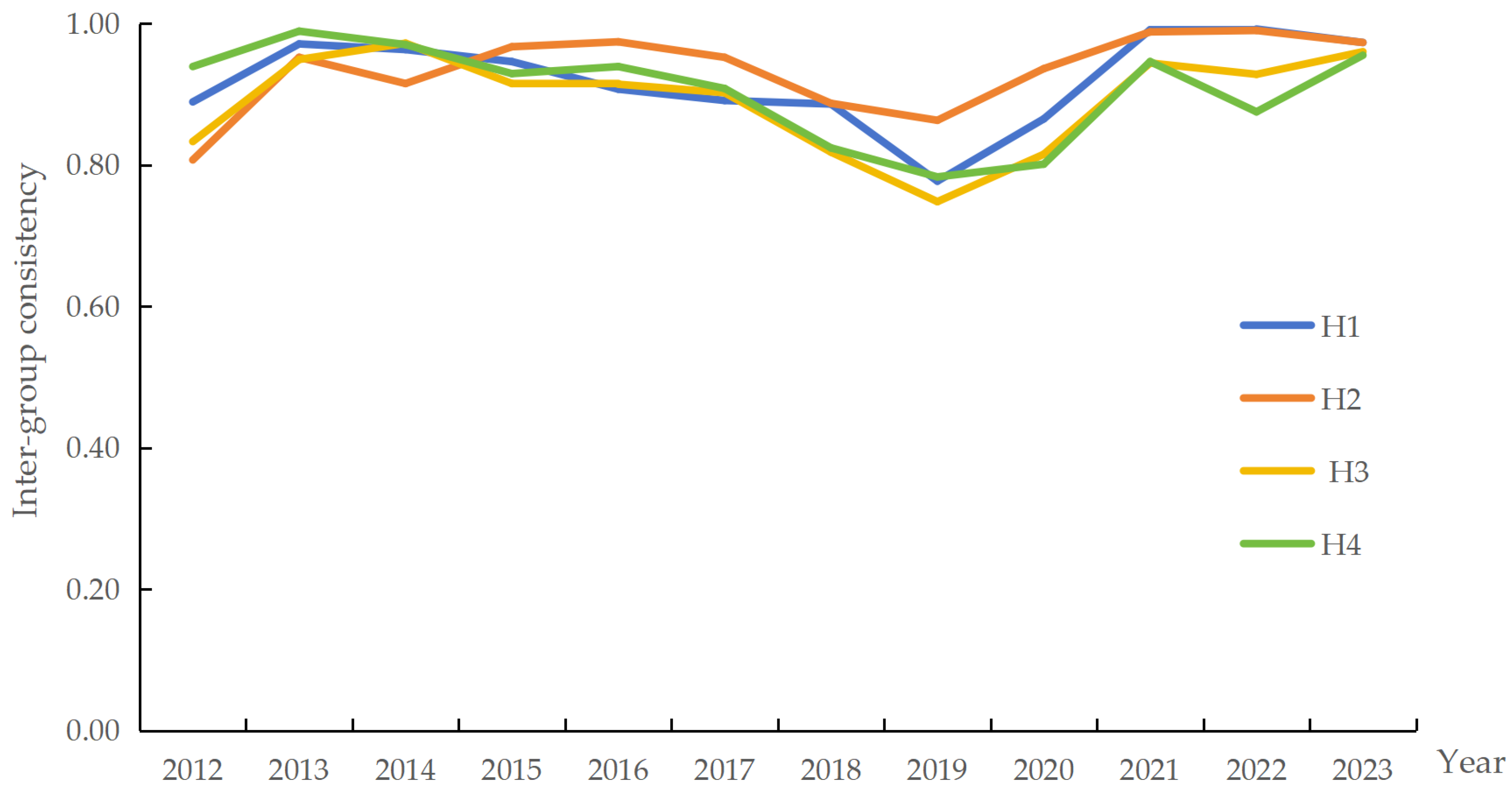

Third, inter-group and intra-group consistency analyses revealed that none of the configuration pathways exhibited significant temporal effects, yet all demonstrated pronounced spatial heterogeneity. This indicates that the explanatory power of the four core pathways maintains strong stability and applicability over time, while their suitability varies significantly across different regions. Specifically, the enterprise-driven and industry-supported model suits Northeast and Central China; the technology-innovation-led model suits South China and Northeast China; the market-driven factor integration model suits East China, Central China, and Southwest China; the government-led multi-stakeholder collaboration model suits Southwest and Central China. These findings provide robust theoretical foundations and practical guidance for regions to develop tailored strategies—based on local conditions—for coordinating agroforestry economy growth with ecological conservation.

6.2. Implications

Based on the findings of this study, the following insights are proposed to promote the coordinated development of the agroforestry economy and ecological environment:

First, for regions where the enterprise-driven and industry-supported model is viable, the focus should be on nurturing local enterprises and strengthening industrial support capabilities. On one hand, select local enterprises with scale and potential for targeted support, leveraging policy tools such as fiscal interest subsidies and tax breaks to help leading enterprises expand production capacity. Promote joint operations between local enterprises and small-scale operators like family forest farms and specialized cooperatives to enhance the overall operational efficiency of the regional agroforestry economy. On the other hand, deepen the integration of the three industrial sectors within the agroforestry economy, promoting deep synergy with related industries such as eco-tourism, forest wellness, and nature education. Improve the supporting industrial infrastructure by introducing ancillary enterprises for sorting, preservation, packaging, and warehousing. Create integrated industrial parks to enhance the sector’s risk resilience and overall competitiveness.

Second, for regions where the technology-innovation-led model is applicable, it is recommended to increase investment in scientific research and development within the agroforestry economy. On one hand, establish a diversified R&D funding mechanism by setting up specialized research funds to prioritize key technological developments in ecological cultivation, green pest control, deep processing, and waste recycling. Guide enterprises to become the primary R&D investors, offering policy incentives such as additional tax deductions for R&D expenses and subsidies for purchasing research equipment to companies engaged in relevant technological development. On the other hand, support business entities in collaborating with universities and research institutes to establish joint R&D centers and laboratories, focusing on targeted breakthroughs for regionally distinctive agroforestry products. By establishing technology transfer platforms and enhancing technical training for forest farmers, we will facilitate the application of technological achievements in the agroforestry economy to large-scale industrial use.

Third, for regions where the market-driven factor integration model is applicable, we recommend continuously expanding market demand for agroforestry economy products. On the one hand, we will strengthen the promotion of green consumption concepts. Through community outreach, public lectures, and media campaigns, we will highlight the ecological value, nutritional benefits, and health advantages of the agroforestry economy products, guiding consumers toward green consumption practices. Implement green consumption incentive policies, such as distributing product vouchers and offering logistics subsidies, to stimulate consumer enthusiasm. Simultaneously, develop differentiated products targeting diverse needs—including health and wellness, premium dining, and cultural tourism experiences—to expand market reach across multiple dimensions. Improve production, sales, and distribution systems by leveraging offline product trading centers, online community group buying, and livestream sales to broaden market channels and enhance product circulation efficiency. Establish a comprehensive traceability system for product quality to address consumer trust concerns.

Fourth, for regions where the government-led multi-stakeholder collaboration model is feasible, strengthen governmental leadership and coordination capabilities; develop specialized plans for agroforestry economy development, defining clear objectives, priority sectors, and implementation pathways to avoid haphazard development and homogenized competition; and construct a comprehensive policy support system, prioritizing improvements in infrastructure such as storage and preservation facilities, processing equipment, and transportation logistics to enhance the foundational conditions for high-quality industrial development. On the other hand, strengthen quality assurance and ecological environmental protection oversight; establish a robust product quality and safety supervision system, formulate unified product standards and testing protocols, and reinforce quality control across the entire production, processing, and distribution chain; and enhance ecological environmental protection supervision by developing ecological access standards and green production norms to promote the synergistic development of the agroforestry economy and the ecological environment.