1. Introduction

Rice (

Oryza sativa L.) remains the cornerstone of global food security, providing staple nourishment for over half of the world’s population. However, the stability and sustainability of rice production are increasingly threatened by global climate change, characterized by erratic precipitation patterns and increasing water scarcity [

1]. Furthermore, the reduction in arable land and the intensification of land marginalization are diminishing its food production potential, thereby threatening long-term food security [

2]. In this context, the development and utilization of drought-tolerant upland rice landraces adapted to rain-fed systems are a critical strategic priority for mitigating the effects of climate change, securing food supply, and fostering sustainable agriculture [

3]. This is particularly valuable as upland rice effectively utilizes marginal mountainous and hilly terrains, thereby mitigating the competition for limited freshwater resources typically consumed by irrigated lowland rice.

Upland rice is a vital component of food security not only in China but also across various agro-ecosystems in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America [

4,

5,

6]. Shanlan upland rice, a distinct and locally domesticated variety, is unique to the mountainous regions of Hainan Province, China [

7]. It serves as an important model for studying genetic adaptation to tropical island environments. These landraces, characterized by heat and drought resistances, resulting in genotypes possessing superior resilience and adaptation to the local agro-ecological conditions have been traditionally selected and cultivated by the indigenous Li ethnic communities over generations. Beyond its ecological adaptability, Shanlan upland rice holds significant cultural value and economic potential, particularly in the production of specialty foods and traditional wines [

8,

9], supporting regional economic diversity.

Shanlan upland rice exhibits many traits characteristic of wild rice, such as the presence of awns, lemmas, and strong shattering in many landraces, suggesting that Shanlan upland rice may have a more ancient genetic relationship with wild rice. Based on sequencing five genetic regions from 14 Shanlan upland rice samples in Hainan, compared to Asian cultivated rice and wild rice samples, it was found that Shanlan upland rice has lower genetic diversity than Asian cultivated rice, with about 85% of it being japonica-type, and is more closely related to wild rice from Guangdong and Hunan provinces, suggesting its potential origin from these regions [

10]. Additionally, a genetic diversity analysis of 214 upland rice varieties from Southeast Asia and five provinces in southern China using SSR markers further supports this, hypothesizing that the Hainan Shanlan upland rice likely originated from Guangdong province and is genetically distinct from upland rice in Hunan Province [

8]. The Shanlan upland rice resource pool, confined within the limited geography of Hainan Island and subject to traditional, isolated farming practices, faces heightened risks of genetic homogeneity and the irreversible loss of unique genetic information. Furthermore, based on reports from multiple studies, the genetic base of Shanlan upland rice landraces is relatively narrow [

10,

11]. Despite this, Shanlan upland rice exhibits a broad genetic diversity in starch physicochemical parameters [

12], which can be utilized to improve the cooking and eating quality in rice breeding. The apparent paradox of low genome-wide diversity coupled with high variation in starch-related traits suggests strong selection pressure on key functional genes. This finding underscores the value of targeted conservation and utilization.

Despite its ecological adaptability, Shanlan upland rice suffers from a lack of a comprehensive and reliable molecular fingerprinting system, which is critical for the effective management, genetic improvement, and conservation of this valuable germplasm. While phenotypic evaluations have been conducted to assess trait diversity, molecular markers provide a more stable and precise tool for resource management and genetic identification. The integration of phenotypic and molecular data is crucial at this stage to better understand the genetic variation within Shanlan upland rice and establish a standardized fingerprinting system.

Systematic genetic diversity analysis constitutes the essential foundational step for effective germplasm identification, genetic improvement, resource conservation, and novel landrace selection [

13,

14]. Traditional methods of germplasm identification, relying solely on morphology such as plant stature, flower color, or grain shape, are inherently limited. Because morphological traits cannot accurately reveal the underlying genetic variation present within the germplasm collection [

15]. Molecular markers, unlike morphological markers, overcome environmental influences and can detect subtle genetic variations that phenotypic evaluation may miss. They offer advantages such as stability, the ability to be detected in all tissues, and independence from factors like cell growth, development, and environmental conditions. These markers provide more reliable and precise genetic identification, making them essential for resource characterization and genetic analysis [

16]. Molecular marker technology, which focuses on differences in DNA sequences, provides objective and environment-independent genetic information crucial for germplasm characterization, kinship analysis, and molecular breeding [

17,

18]. Various marker types have been historically applied in rice genetics, including simple sequence repeat (SSR), Insertion/Deletion (InDel), and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers, which are utilized for germplasm identification [

8,

19,

20].

This study addresses the need for genetic improvement and resource conservation in Shanlan upland rice landraces. Despite its ecological adaptability, Shanlan upland rice landraces faces threats due to limited genetic diversity, which could hinder future breeding efforts. Therefore, characterizing this specific germplasm contributes valuable data to the global gene pool, offering potential genetic resources for improving climate resilience in rice breeding programs worldwide. The research aimed to develop a comprehensive molecular and phenotypic framework for 114 Shanlan upland rice landraces, evaluating phenotypic variation, assessing genetic diversity using 38 InDel markers, and exploring genetic relationships through phylogenetic clustering. Key achievements include establishing a DNA fingerprinting system with a minimal set of 19 highly discriminatory InDel markers, which facilitates efficient landrace authentication, redundancy control, and germplasm management. By narrowing the genetic pool through core germplasm selection, the study provides a streamlined resource for breeding efforts aimed at improving drought tolerance, yield potential, and culinary quality. The findings offer valuable insights for future breeding programs and provide a reproducible workflow for similar research, advancing the use of molecular markers in crop improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Field Management

The experimental materials used in this study comprised 114 Shanlan upland rice landraces, predominantly collected from the mountainous areas of Hainan province, China. These materials represent various local upland rice landraces, including black/red-shelled red rice landraces, Shanlan upland rice landraces with red and yellow husks. The experiment was conducted at the base of Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences (Danzhou, China). The seeds were sown on 31 January 2024. After 25 days, the seedlings were transplanted, with 48 plants of each landrace planted per plot. The experiment was conducted with three field replicates. The soil type used in the trial was previously used for rice cultivation. The planting density was set at a row spacing of 20 cm and a plant spacing of 20 cm. The fertilization schedule and nutrient distribution were as follows: The fertilization regime for the field trial included a total of 150 kg/ha of nitrogen (N), 60 kg/ha of phosphorus (P

2O

5), and 90 kg/ha of potassium (K

2O), applied throughout the entire growing season. The fertilization schedule and nutrient distribution were as follows: 50% of N and K

2O were applied as base fertilizer, along with 100% of P

2O

5 at the start of the growing season. 25% of nitrogen was applied during the early tillering stage, with no P

2O

5 or K

2O applied at this stage. During the mid-late panicle formation stage, 25% of N was applied, along with 50% of K

2O. Irrigation was applied only during the first 30 days after transplanting, with irrigation occurring once every 6 days. After this period, the crop relied solely on natural rainfall without further irrigation. This cultivation method is referred to as “water-managed dry cultivation”, which ensures uniform planting conditions while simulating the growing conditions of Shanlan upland rice. Meteorological conditions at the Danzhou experimental site were monitored throughout the growing season from February to June 2024. A summary of the key meteorological data, including monthly average temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall, is provided in

Table S1. Detailed historical weather trends for this region can be found in our previous study [

21]. The average temperature during this period was 26.4 °C, exhibiting a steady increasing trend from 21.8 °C in February to 29.5 °C in June. The relative humidity remained high, averaging 77.6%, with a range of 69.1% to 82.7%. Precipitation distribution was variable, with an average monthly rainfall of 136.9 mm. Conventional field management practices for rice cultivation were followed to ensure consistency in conditions, minimizing the impact of environmental factors on phenotypic measurements.

2.2. Phenotypic Data Collection and Evaluation

Throughout the growth period of the plants, phenotypic data were collected on days to heading and plant height. For the plant height survey, five plants were randomly selected per landrace for measurement. Upon seed maturity, three plants with consistent growth were selected for harvesting and drying. Subsequently, data such as tiller number, effective tillers, and panicle length were measured. After threshing, seeds were analyzed using a digital seed tester (YTS-5D, Wuhan, China) to determine yield-related traits, including yield per plant, thousand-grain weight, total spikelets, seed setting rate, number of spikelets per panicle, grain shape (grain length and width). The phenotypic data from the three field replicates were averaged to obtain the final phenotypic data for each trait.

2.3. Genomic DNA Extraction and Molecular Marker Selection

Genomic DNA from the 114 Shanlan upland rice landraces was extracted using the CTAB method [

22]. Thirty-eight InDel molecular markers (

Table S2) were selected for the study, based on markers previously published [

23]. To ensure comprehensive genome-wide coverage, the markers were selected based on their physical positions to achieve uniform distribution across the 12 rice chromosomes. Approximately three markers were chosen for each chromosome, spaced at distinct physical intervals, to maximize the representation of genetic diversity across the entire genome.

2.4. PCR Amplification System and Procedure

The final volume of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system was set to 15 μL. The components included: 20 ng of template DNA, 0.5 μL of each forward and reverse primer, 7.5 μL of 2× Rapid Tap Master Mix (P222, Vazyme, Nanjing, China), and the remaining volume made up with deionized water. The PCR program was set as follows: 94 °C for 3 min (initial denaturation), followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s (denaturation), 58 °C for 30 s (annealing), and 72 °C for 30 s (extension). A final extension was performed at 72 °C for 2 min, followed by a 1-min hold at 25 °C and storage at 4 °C.

2.5. Electrophoretic Detection and Polymorphism Analysis

The amplified PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis. Electrophoresis was conducted on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with 3% fluorescent DNA dye (GoldView, Zomanbio, Beijing, China) under constant conditions of 400 V and 250 mA for 20 to 23 min. The gel was observed and photographed using a UV gel imaging system to record different genotypes of amplified fragments across landraces, thereby determining the polymorphism of the InDel markers. The different genotypes are represented by different Arabic numerals. If the banding pattern remained ambiguous after verification, it was treated as missing data (NA) and excluded from the analysis to prevent genotyping errors. Consistent amplification failure was initially scored as a chromosomal deletion (‘0’). However, to account for potential technical issues, we attempted three different enzymes and multiple PCR amplification conditions. If amplification failed under all conditions, the result was interpreted as a chromosomal deletion, which represents a special genotype.

2.6. Polymorphism Information Content Calculation

The polymorphism information content (PIC) was calculated for each polymorphic marker to assess its informativeness using the following formula:

where p

ij is the frequency of the j-th genotype of the i-th marker in the sample set, and

n is the total number of genotypes [

24,

25]. A higher PIC value indicates greater polymorphism, broader applicability of the marker, and higher genetic diversity, whereas a value of 0 indicates a monomorphic marker.

2.7. Simple Matching Coefficient and Genetic Distance Calculation

The simple matching coefficient (SMC) is a measure of genetic similarity between two Shanlan upland rice landraces based on the genotype’s comparison of molecular markers. The formula is as follows:

where

represents the state of the i-th marker for a pair of Shanlan upland rice landraces (Where

if the marker state matches for the pair, and

if it does not match). n is the number of markers;

N is the total number of markers being considered. The genetic distance matrix was then calculated by applying the standard transformation:

[

26].

2.8. Phylogenetic Tree Construction

Subsequently, cluster analysis was performed using the Unweighted Pair-Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) to provide a graphical representation of the genetic relationships among the Shanlan upland rice landraces. The resulting UPGMA dendrogram was visualized using the ggtree package (version 4.0.1) [

27].

2.9. DNA Fingerprinting System

To establish a precise and streamlined DNA fingerprinting system, we employed a stepwise selection strategy (greedy optimization algorithm) to identify the minimum marker set required to distinguish all landraces. Instead of using all markers, the selection process was iterative: it began by selecting the single most informative marker. Subsequently, markers were added one by one based on their ability to differentiate the remaining similar landraces. This approach maximized the resolution power at each step, resulting in the selection of 19 core markers from the initial 38. These 19 markers successfully differentiated all 114 landraces and were subsequently utilized to develop the DNA fingerprinting system, facilitating efficient variety identification, kinship analysis, and intellectual property protection.

Based on both the DNA fingerprinting and phenotypic data, QR codes were generated, encompassing information for 114 Shanlan upland rice landraces. The QR codes were created using the online platform

https://cli.im/. Through these QR codes, users can access not only the specific DNA fingerprint data but also relevant agronomic trait information, enhancing the traceability and utility of the rice landrace data.

2.10. Core Germplasm Selection of Shanlan Upland Rice Landraces

To construct a core collection representing the genetic diversity of Shanlan upland rice landraces, we employed a graph-based clustering approach using the SMC matrix derived from genome-wide binary markers. The lower triangular SMC matrix was first symmetrized to generate a complete pairwise similarity matrix. It is generally accepted that an SMC value above 0.75–0.80 indicates similar varieties [

19,

28]. In this study, we set the threshold for SMC at 0.85, considering landraces with an SMC greater than 0.85 as similar. An undirected similarity network was then constructed by connecting pairs of accessions with SMC ≥ 0.85. Connected components (i.e., maximal subgraphs in which all nodes are reachable from one another) were identified using the igraph package (version 2.2.1) in R [

29]. Within each connected component, a single representative accession was selected as the core entry. Specifically, the accession with the highest average genetic similarity to other accessions within its cluster was chosen, ensuring that the selected variety most accurately represents the genetic diversity within that cluster. Accessions forming singleton components (i.e., with no similarity ≥ 0.85 to any other accession) were retained as genetically unique or “distinctive” germplasm.

2.11. Visualization

All visualizations, except for certain figures (

Figure 1 and

Figure S2) and tables created in Excel, were generated using R [

30]. The R packages used include adegenet (version 2.1.11), APE (version 5.8.1), Dplyr (version 1.1.4), ggplot2 (version 4.0.1), ggtree (version 4.0.1), igraph (version 2.2.1), pheatmap (version 1.0.13) and Poppr (version 2.9.8 [

27,

29,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Diversity and Variability in Agronomic Traits

The evaluation of the 114 Shanlan upland rice landraces demonstrated significant phenotypic heterogeneity, confirming the rich genetic resource contained within this landrace collection.

Fourteen representative Shanlan upland rice landraces were observed for plant architecture, panicle type, and grain shape. The observations revealed that the traditional Shanlan upland rice plants were generally tall, although some lines exhibited shorter stature. Significant differences were observed among the different lines in terms of plant architecture and the number of tillers (

Figure 1A–C). Representative panicles were selected, showing that landraces such as SL79 and SL111 had relatively longer panicles. The glume color varied, including yellow, black, and brown-red glumes, further highlighting the diversity of Shanlan upland rice landraces (

Figure 1D). The grain shape observation exhibited considerable variation. Landraces SL52, SL66, SL111, and SL112 had relatively wider grains, while SL41 and SL92 had the shortest grain lengths. Additionally, seeds from SL52, SL111, and SL112 exhibited lemma, and these morphological differences serve as important reference indicators for variety identification (

Figure 1E,F). Additionally, awns were observed in several landraces, and some Shanlan upland rice landraces exhibited stronger shattering traits, suggesting that Shanlan upland rice may have a more ancient genetic relationship with wild rice.

3.2. Variability of Yield Related-Traits in Shanlan Upland Rice Landraces

In 2024, phenotypic traits of 114 Shanlan rice landraces were measured, revealing significant variability across the resource population (

Table 1,

Figure S1, Table S3). Traits such as yield per plant, effective tillers, plant height, and seed setting rate showed considerable variation.

The days to heading of Shanlan upland rice landraces varied from 70.5 to 96.5 days, with an average of 77.7 days. Although this variation indicates a diverse range of early- and late-maturing varieties, the overall trend is skewed toward earlier flowering landraces.

Plant height in the Shanlan upland rice landraces ranged from 88.3 cm to 160.8 cm, with an average of 123.4 cm. The significant variation in plant height suggests that these landraces exhibit diverse growth forms, which may influence traits such as lodging resistance and overall biomass production.

Yield per plant ranged from 5.1 g (SL75) to 25.6 g (SL15), with an average of 12.7 g. This trait is closely related to three key yield components: the number of tillers, number of spikelets per panicle, and thousand-grain weight. The interrelationships between number of tillers, spikelets per panicle, and thousand-grain weight significantly impact yield per plant. For example, SL15, with high values for all three yield components, achieved the highest yield per plant (25.6 g). These results highlight the importance of selecting for optimal combinations of these yield components to enhance rice productivity in breeding programs.

The grain shape in Shanlan upland rice landraces also exhibited significant variation. Grain length ranged from 7.2 mm (SL9) to 9.5 mm (SL82), with a mean of 8.3 mm, and grain width varied from 2.0 mm to 3.6 mm. The length-to-width ratio ranged from 2.3 to 4.3, with an average of 3.0.

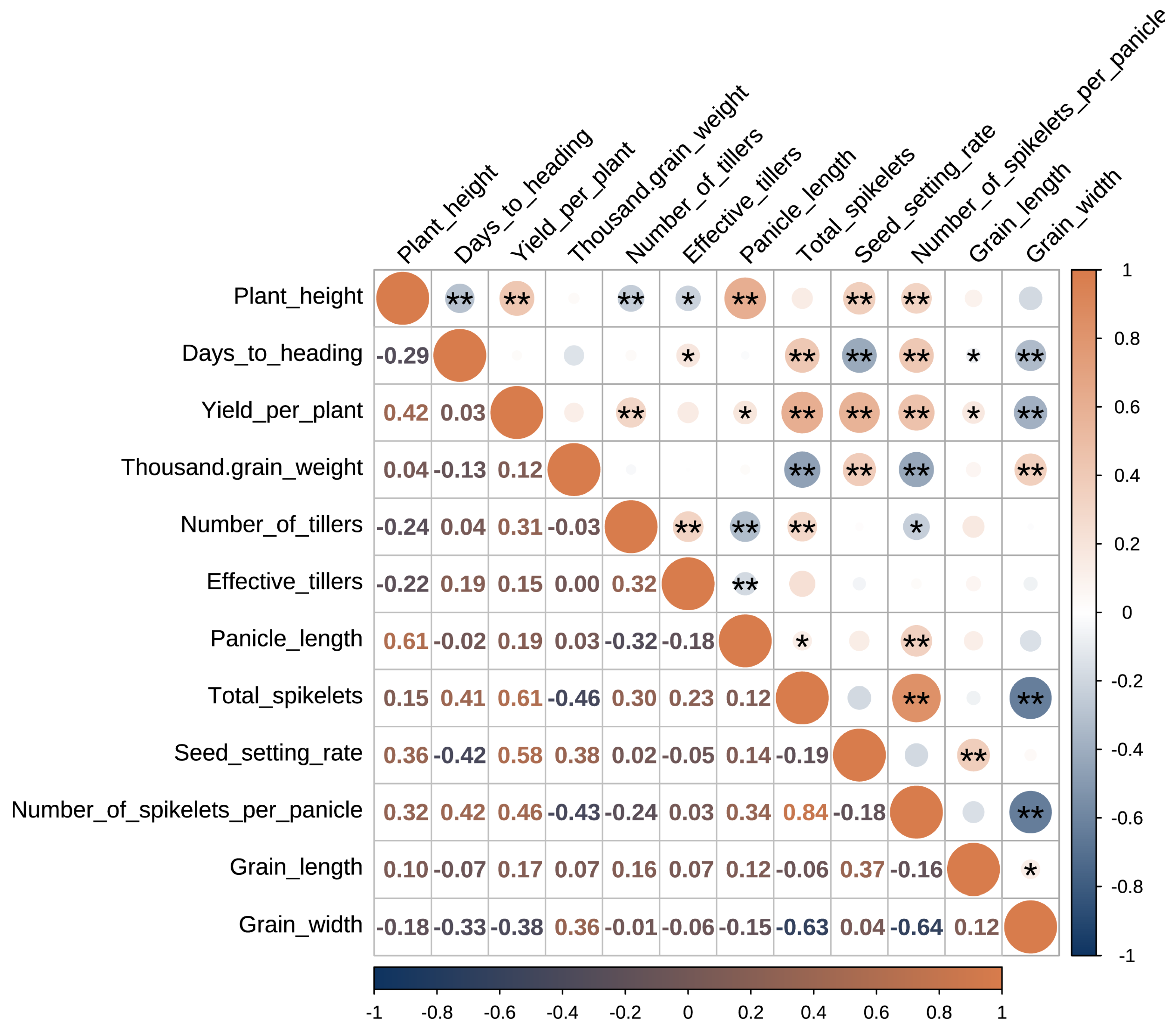

3.3. Correlation Analysis Among Yield Related-Traits

Correlation analysis was performed to elucidate the intricate relationships between different yield components (

Figure 2). The analysis revealed that yield per plant is most strongly associated with the parameters defining reproductive sink capacity. Specifically, Yield per plant showed a robust positive correlation with total spikelets (

r = 0.61) and number of spikelets per panicle (

r = 0.45). These findings demonstrate that in Shanlan upland rice, the primary mechanism for yield maximization is increasing the number of potential grains (the sink), rather than relying heavily on vegetative characteristics like tillering (number of tillers correlated positively with yield at r = 0.31).

The study also documented classic physiological trade-offs inherent in plant architecture. A moderate negative correlation was found between thousand-grain weight (grain size) and number of spikelets per panicle (r = −0.43). This source–sink constraint implies that selection pressures aimed at increasing grain size often result in a corresponding reduction in the number of grains the plant can effectively fill, constraining overall volumetric yield.

Furthermore, we identified a complex adaptive conflict involving days to heading. Days to heading correlated positively with total spikelets (r = 0.42), suggesting that a longer growth duration allows more time for photosynthetic accumulation and reproductive development, leading to a larger potential sink size. However, this longer developmental cycle simultaneously resulted in a negative correlation with seed setting rate (r = −0.42). This negative relationship strongly suggests that later-maturing landraces are more likely to encounter environmental stresses, specifically high temperatures common in the late season of tropical Hainan, during the sensitive flowering and fertilization period, resulting in pollen sterility and reduced fertility.

3.4. Polymorphism Analysis and Informativeness of Indel Markers

The PIC values (

Table S4) for 38 InDel markers were calculated to assess the informativeness of each marker. The PIC values ranged from 0.12 to 0.64, with an average of 0.43. More than half of the markers had PIC values below 0.5 (

Figure S2), indicating that the overall genetic diversity of the Shanlan upland rice landraces is at a moderately low level.

Among the markers, 16 showed higher informativeness, with PIC values greater than 0.5. The most effective markers for genotype identification included LInD2-136 (PIC = 0.64), LInD10-100 (PIC = 0.60), and LInD4-75 (PIC = 0.59) (

Table S4). These highly polymorphic markers are especially valuable as they have the greatest ability to differentiate closely related landraces.

3.5. Genetic Similarity and Assessment of Germplasm Redundancy

To accurately map the genetic relatedness and redundancy within the Shanlan upland rice landraces, we calculated the pairwise SMC values for all 114 landraces (

Table S5,

Figure 3). The SMC values ranged widely from 0.18 to 1.00, with an average of 0.54 ± 0.12. In total, there are 6441 pairwise comparisons among 114 landraces. Approximately 72.3% of the comparisons fell between 0.40 and 0.70, confirming that the population shares a common genetic background while exhibiting moderate differentiation. Among these, 506 pairs have an SMC value greater than 0.85, indicating that 506 pairs are highly similar to each other. This accounts for 7.9% of the total comparisons.

The analysis also identified several key examples of genetic redundancy, where certain landrace pairs showed complete genetic identity (SMC = 1.00). This typically indicates the presence of duplicate germplasm due to either sampling repetition or the collection of genetically identical varieties from different locations. Specifically, pairs and groups such as SL27/SL28, SL50/SL51, SL73/SL74, and SL25/SL27/SL28/SL30/SL33 displayed genetic identity or near-identity, suggesting significant redundancy within the population (

Table S5). This also highlights the usefulness of calculating SMC as a rapid method for identifying whether germplasm is genetically identical.

On the other hand, the study successfully identified landraces representing extreme genetic divergence, such as the pair SL92 and SL59 (SMC = 0.18), and SL109 and SL59 (SMC = 0.21) (

Table S5). These landraces represent valuable sources of unique alleles that are critical for broadening the genetic base. They offer significant potential for future breeding programs, particularly in creating heterotic groups or introducing novel adaptive traits.

3.6. Population Structure and Phylogenetic Relationships

Using genetic distances calculated from 38 InDel markers, a UPGMA analysis was performed to explore the potential genetic structure of Shanlan upland rice landraces. (

Figure 4). The analysis clearly revealed that the 114 landraces could be grouped into three distinct primary genetic clusters or subpopulations. Notably, varieties SL25, SL27, SL28, SL30, and SL33 clustered together within the same branch, which is consistent with the results obtained from SMC analysis, as the genetic distance is inversely related to the SMC (Genetic distance = 1 − SMC). This clustering reflects the underlying genetic relationships and similarities among the varieties, further corroborating the findings of the SMC-based similarity analysis.

Within each identified cluster, the landraces displayed high genetic similarity, confirming close kinship and a shared history of localized selection. However, the genetic distances between these three major clusters were significantly larger, establishing a robust and clear population structure.

Using K-means clustering analysis, the majority of the varieties were grouped into three distinct subgroups (

Figure S3). This result aligns well with the findings from the evolutionary tree analysis, further supporting the consistency and reliability of the genetic structure observed in the Shanlan upland rice landraces. The clustering analysis corroborates the pattern observed in the UPGMA tree, where the same three primary genetic clusters were identified.

3.7. Construction and Validation of the Minimum DNA Fingerprinting Marker Set

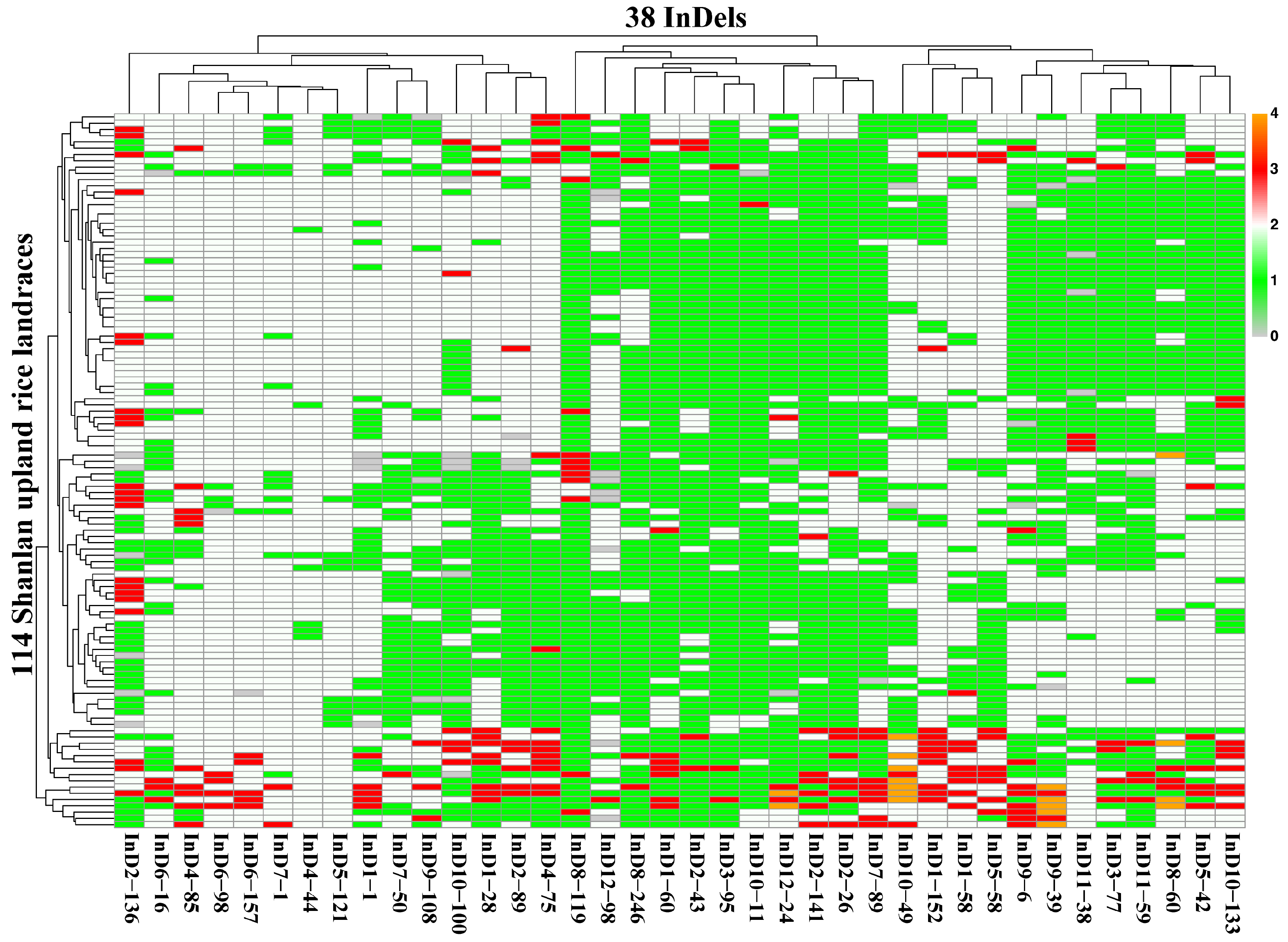

Based on the genotypic data from 38 markers, we constructed a heatmap to visualize the relationship between the varieties and the markers (

Figure 5). The heatmap clearly highlights the genotypic variations across different landraces at various loci, providing an insightful overview of the genetic diversity within the Shanlan upland rice landraces.

In the identification of germplasm resources, it is essential to establish an optimized minimal InDel marker set that can uniquely identify each landrace. A stepwise greedy optimization algorithm was implemented in R to identify the core marker set. This iterative process sequentially selected markers that, when combined with the existing set, maximized the number of unique genotype combinations across the population. Consequently, a total of 19 core markers were selected from the original 38, achieving 100% discrimination efficiency. These markers include: LInD1-1, LInD1-28, LInD1-58, LInD1-60, LInD1-152, LInD2-26, LInD2-43, LInD2-89, LInD2-136, LInD2-141, LInD6-16, LInD8-60, LInD8-246, LInD9-6, LInD9-39, LInD10-49, LInD10-100, LInD11-38, and LInD12-98 (

Table S6).

This reduced marker set provides sufficient resolution to generate unique digital fingerprints for all 114 Shanlan upland rice landraces. This core marker set offers a robust and scientifically verifiable molecular identification system. The reduction in marker quantity from 38 to 19 significantly enhances the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of future germplasm screening, facilitating the rapid identification and validation of germplasm in the resource bank.

The utility of this minimal marker set is summarized in the digital fingerprint code (

Table S7). To facilitate data accessibility and reuse, an online database containing the DNA fingerprint profiles and phenotypic data of the 114 Shanlan upland rice landraces has been established. The dataset is publicly available at:

https://github.com/huweihzau/Rice-DNA-Fingerprint-Analysis (accessed on 14 December 2025) (output directory). Through this online resource, users can directly access the DNA fingerprint profile of each landrace together with its associated phenotypic traits, including plant height, yield per plant, thousand-grain weight, days to heading, tiller number, effective tillers, panicle length, number of spikelets, number of filled grains, empty grains, seed setting rate, spikelets per panicle, grain length, grain width, aspect ratio, grain area, and grain perimeter. This integrated digital fingerprinting system provides a convenient and practical tool for breeders and researchers to efficiently query, compare, and utilize germplasm information in future breeding programs.

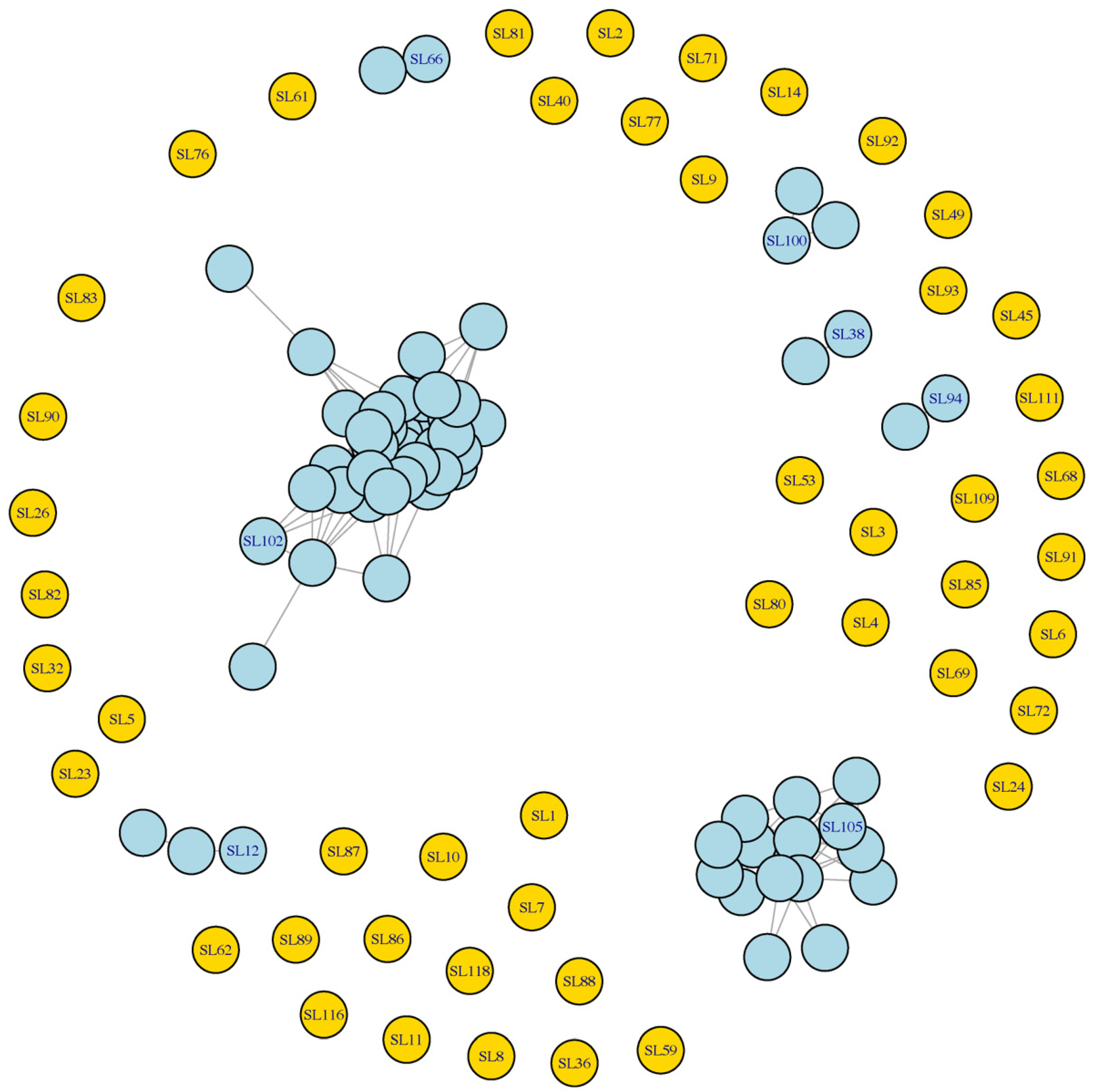

3.8. A Network-Based Core Germplasm of Shanlan Upland Rice Landraces

Using the network-based strategy, the core germplasm, including 54 Shanlan upland rice landraces, was identified from the original 114 landraces (

Figure 6,

Table S8), effectively reducing redundancy while preserving genetic representation. Among these, 7 landraces were classified as genetically distinctive, as they formed singleton connected components—indicating no close similarity (SMC ≥ 0.85) to any other landrace in the dataset. The remaining 47 core landraces each represent a distinct similarity cluster, collectively capturing the major genetic groups within the Shanlan upland rice germplasm. This core set provides a streamlined yet comprehensive resource for future phenotypic evaluation, genomic analysis, and breeding utilization.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the genetic diversity and agronomic traits of 114 Shanlan upland rice landraces, focusing on their potential for breeding and conservation. Our findings highlighted significant phenotypic variation in traits such as plant height, tiller number, panicle length, and grain shape, which are crucial for future breeding strategies aimed at improving rice productivity and resilience.

4.1. Genetic Diversity and Its Implications for Breeding

The observed PIC value of 0.43 indicates a moderate level of genetic diversity, suggesting a narrow genetic base for the Shanlan upland rice landraces. This level is notably lower than that typically reported for broad global collections of

Oryza sativa (often PIC > 0.6) [

28,

37,

38,

39], but is consistent with previous findings regarding landraces in this region [

10,

11,

40]. This consistency reinforces that, despite differences in marker types used across studies (InDel vs. SSRs), the assessment of a constrained underlying genetic background remains robust. The reduced diversity is primarily attributed to a ‘founder effect’ resulting from the unique geographic isolation of Hainan Island and limited gene flow. Furthermore, the long-standing tradition of localized selection within Li ethnic communities, which focused on adaptation to local barren mountainous and dryland environments, has created a genetic bottleneck. While this specific genetic background has enabled historical adaptation to local biotic and abiotic stresses, it limits the population’s potential for rapid adaptation to new environmental pressures and future climate extremes. Consequently, relying solely on existing variation is insufficient. There is an urgent need for genetic introgression, introducing favorable alleles from modern elite varieties or wild relatives to enhance yield potential and lodging resistance while preserving the core adaptive traits of Shanlan rice.

The juxtaposition of low genome-wide diversity with high variation in starch-related traits presents an intriguing paradox. Despite the narrow genetic base, the broad variation in starch physicochemical properties observed in this study is significant for breeding programs focusing on rice quality, particularly cooking and eating traits [

12]. We hypothesize that this phenomenon is driven by anthropogenic diversifying selection. While geographic isolation restricted overall gene flow (reducing genome-wide diversity), local farmers actively selected and maintained diverse genotypes specifically for culinary purposes—ranging from glutinous types for traditional wine making to non-glutinous types for staple food. This may be the reason why the local farmers tend to prefer varieties with shorter or medium-long grains, which likely aligns with local dietary consumption habits. This strong artificial selection acted as a centrifugal force, preserving diversity at specific functional loci (e.g., starch synthesis genes) even as the genetic background became homogenized. Consequently, targeted conservation of these specific traits could enhance the culinary quality of Shanlan upland rice while preserving the genetic adaptability necessary for its ecological niche [

41].

While geographic isolation has resulted in a narrower genetic base, it highlights the importance of Shanlan rice as a reservoir of rare and ancient alleles. Landraces maintained by indigenous communities in isolated regions are increasingly recognized globally as critical buffers against genetic erosion [

42]. The primitive traits observed in Shanlan rice (e.g., awns and shattering) suggest a close evolutionary relationship with wild rice, providing a unique opportunity for researchers worldwide to explore the domestication history of

Oryza sativa and to mine ‘lost’ genes for stress resistance that modern cultivars lack [

43].

Previous studies have generally classified Shanlan upland rice as a distinct ecotype within the

japonica subspecies [

10]. Since we do not have a cultivated rice control, our population structure analysis (UPGMA) does not contradict this broader genetic background. However, this study reveals a more refined structure within the Shanlan upland rice germplasm, identifying three distinct and independent genetic subgroups (K = 3). The existence of these three subgroups strongly suggests that, within Hainan Island, the Shanlan upland rice germplasm has undergone independent local adaptation and differentiation processes in different regions and ecological zones. This internal genetic differentiation is a direct reflection of long-term localized selection pressures, environmental gradient differences, and limited gene exchange between different ethnic groups. To further elucidate the evolutionary relationships highlighted by our InDel analysis, future work will focus on whole-genome sequencing. High-density SNP data will enable a deeper investigation into the specific domestication events and genetic introgression patterns between Shanlan upland rice and its wild relatives.

Molecular markers, particularly InDel markers, have proven to be valuable tools for identifying and tracking genetic diversity in rice germplasm [

20]. The 38 InDel markers employed were selected from a verified whole-genome set [

23] to ensure uniform physical spacing across all 12 chromosomes (

Table S2). While the markers are physically comprehensive, we acknowledge that a reduced marker set may not capture all micro-variations compared to high-density SNP arrays. In China, the current standard for new rice variety identification requires the use of 48 SSR markers [

44], whereas the previous version used 24 markers. Based on this, we believe that for the purposes of delineating population structure and establishing a diagnostic fingerprinting system, these markers are appropriate. The development of a minimal set of 19 core markers in this study enables more efficient identification, tracking, and management of Shanlan upland rice landraces. Compared to traditional SSR markers, InDel markers may be more suitable for use by breeding units due to their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency in molecular fingerprinting applications. This marker set, combined with phenotypic data linked via QR codes, offers a practical solution for improving the traceability and commercial value of these landraces, making it an invaluable resource for both breeders and conservationists [

19].

4.2. Challenges in Improving Agronomic Traits

The moderate genetic diversity, particularly within the three identified genetic clusters, indicates that breeding for higher yield potential and broader adaptability may require the introduction of new genetic material. The strategy of introgression beneficial genes from conventional rice varieties into the Shanlan upland rice gene pool could enhance traits such as disease resistance, improved panicle architecture, and semi-dwarfism, which are critical for increasing yield and improving lodging resistance [

3]. However, most Shanlan upland rice landraces are still traditional farmer varieties that have been propagated mainly through seed exchange and local circulation. Currently, the local government is actively promoting the breeding and utilization of Shanlan upland rice, aiming to develop regionally characteristic varieties and derivative products, such as Shanlan rice wine, to enhance the economic and cultural value of this unique genetic resource.

The agronomic profile of Shanlan rice, characterized by tall stature (avg. 123.4 cm) and moderate tillering, is consistent with reports indicating an average upland rice height of around 125.3 cm [

45]. This phenotypic convergence reflects a shared adaptive strategy for rain-fed, low-input environments, where taller plants effectively compete against weeds and typically possess deeper root systems for drought avoidance [

46,

47]. However, this exemplifies a classic ‘survival-over-yield’ trade-off, where adaptive height comes at the cost of lodging resistance and reduced harvest index [

48]. Consequently, breeding efforts must focus on optimizing plant height to modernize these landraces. The

sd1 gene, widely utilized to induce semi-dwarfism [

49], offers a critical pathway to enhance lodging resistance and yield potential [

50]. Therefore, future breeding programs should prioritize the introgression of such dwarfing alleles to balance plant stature with the maintenance of the ecological resilience and drought tolerance inherent in Shanlan upland rice.

4.3. Adapting to Environmental Stressors

The negative correlation between days to heading and seed setting rate observed in this study (

r = −0.42) suggests that late-maturing varieties face greater reproductive challenges. While high-temperature stress during the late reproductive phase causing pollen sterility is a plausible factor [

51,

52], other environmental constraints likely contribute to this phenomenon. For instance, potential soil nutrient depletion during the extended vegetative growth phase could also compromise seed development. Consequently, breeding for early-maturing varieties is a priority to mitigate these cumulative stress effects. This preference likely reflects local farmers’ selection for early-maturing varieties, which may offer advantages such as reduced susceptibility to lodging and bird predation. Early-maturing varieties would allow the crop to ‘escape’ this high-risk period, completing their reproductive cycle before the onset of peak biotic and abiotic stresses. However, it is crucial to balance the shortening of the growth period with maintaining a high sink capacity to ensure maximum yield [

53,

54].

Another strategy is the identification and utilization of genotypes that can maintain high seed setting rates despite late-heading, possibly through the introgression of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) that confer heat tolerance [

55,

56]. Such genotypes would allow for sustained productivity under high-temperature stress, a critical consideration for tropical upland rice production.

4.4. Practical Applications of DNA Fingerprinting and Core Germplasm

The DNA fingerprinting system developed in this study, using 19 InDel markers, provides significant advantages over traditional molecular marker systems, such as SSRs. With fewer markers, this system greatly reduces the experimental workload while maintaining sufficient discriminatory power for genetic identification. This streamlined approach is not only cost-effective but also highly practical, as it can be easily implemented in most research institutions for self-assessment prior to official variety registration or evaluation. In China, the current standard for new rice variety identification requires the use of 48 SSR markers [

44]. In contrast, our system employs far fewer markers, which greatly reduces the experimental workload while maintaining sufficient discriminatory power. The use of agarose gel-based InDel markers adds to the practicality of this system, making it accessible for a wide range of applications in both breeding and conservation efforts.

The establishment of a core collection comprising 54 landraces based on genetic similarity and redundancy further enhances the efficiency of future breeding programs. By reducing redundancy and retaining maximum genetic diversity, the core collection minimizes the resources needed for breeding while preserving essential genetic material for long-term use [

57,

58]. The inclusion of genetically distinct accessions in the core collection opens new opportunities for genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and fine mapping of critical traits such as drought tolerance and yield potential. This will facilitate targeted selection in breeding programs aimed at enhancing stress tolerance and production traits in Shanlan upland rice.

Besides, the QR code database developed in this study enhances the transparency and traceability of both genetic and phenotypic data, contributing to improved data accessibility and management. This database will be a valuable resource for breeders and conservationists, allowing them to track and manage genetic resources efficiently and ensuring the long-term sustainability of Shanlan upland rice germplasm [

59].

Furthermore, the workflow established in this study holds broader methodological implications for germplasm conservation in developing countries. While high-throughput sequencing is powerful, it remains cost-prohibitive for many local breeding programs globally. Our strategy—combining a minimized, reproducible set of agarose-resolvable InDel markers with a low-cost QR code database—provides a scalable and transferable blueprint. This approach can be readily adopted by researchers in other resource-limited regions to efficiently characterize, manage, and digitize their own underutilized indigenous crop resources.

4.5. Limitations

It is important to acknowledge the limitations associated with the phenotypic evaluation in this study, which was conducted in a single year (2024) and at a single location (Danzhou). We recognize that quantitative traits, such as yield and stress tolerance, are complex and heavily influenced by environmental factors and Genotype-by-Environment (G×E) interactions. Consequently, the phenotypic results presented here should be interpreted as a foundational characterization of the diversity within the population rather than a definitive assessment of trait stability across different ecological zones.

However, the primary contribution of this work lies in the molecular characterization and the establishment of a DNA fingerprinting system. Unlike phenotypic traits, the InDel markers used in this study are stable, heritable, and unaffected by environmental variability, providing a robust framework for genetic identification and population structure analysis. Furthermore, the construction of the 54-accession core collection significantly reduces the volume of germplasm requiring intensive evaluation. This streamlined collection provides a manageable and representative set of materials, serving as a critical prerequisite for our future research, which will focus on multi-year, multi-location trials to rigorously validate the environmental adaptability and stability of these Shanlan upland rice landraces.