Reexamining the Determinants of Organic Food Purchases in Online Contexts: The Dual-Factor Model Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

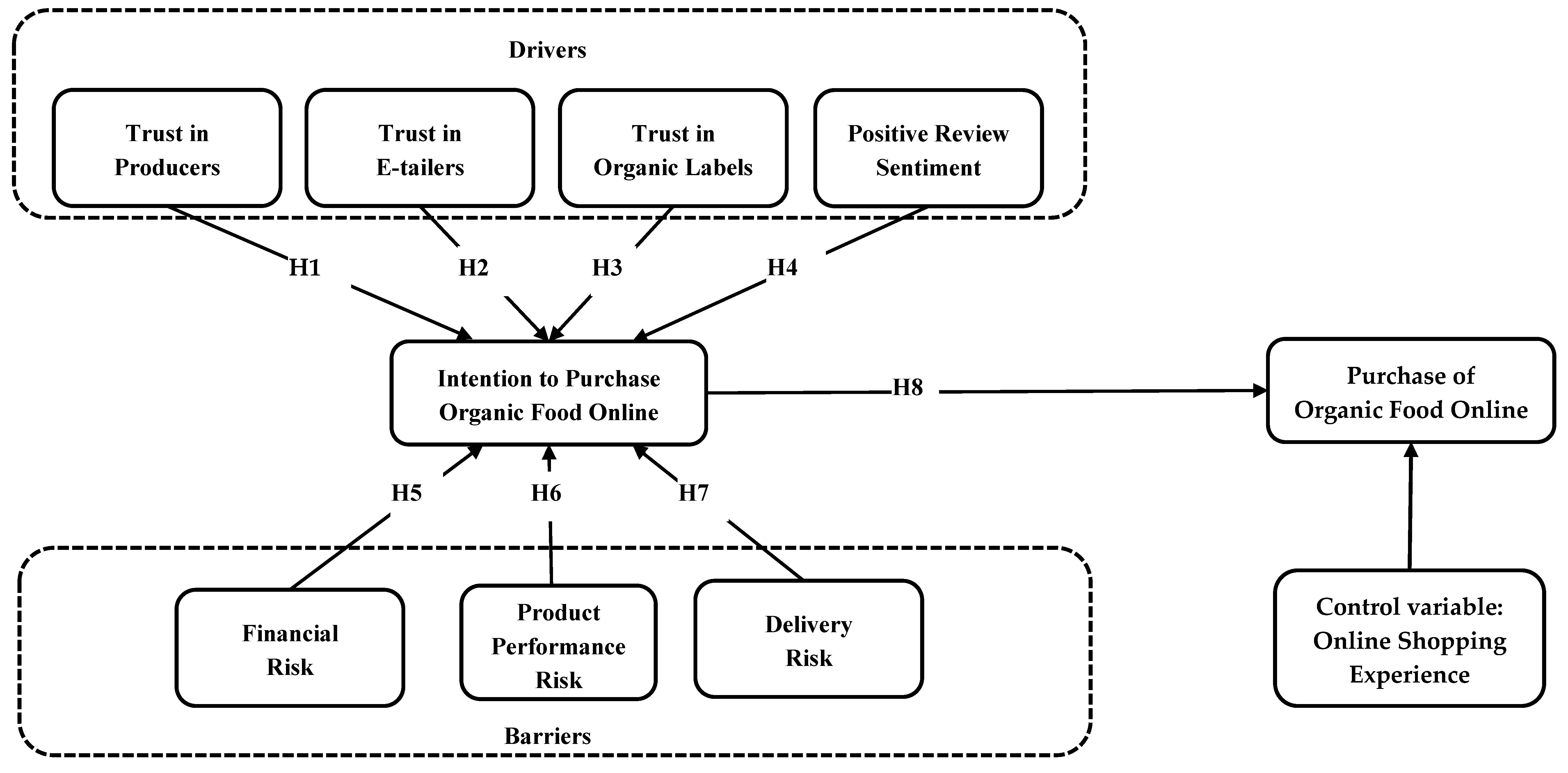

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Organic Food Shopping in Offline and Online Contexts

2.2. Trust Theory

2.3. Risk Theory

3. Method

3.1. Measured Items

3.2. Survey

3.3. Sample Characteristics and Shopping Characteristics of Organic Food

3.4. Analytic Strategies

4. Results

4.1. Nonresponsive Bias Test

4.2. PLS-SEM: Measurement Model

4.3. PLS-SEM: Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista. Organic Share of Total Food Sales in the United States from 2008 to 2022. Statista 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/244393/share-of-organic-sales-in-the-united-states/ (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Hughner, R.S.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A.; Shultz, C.J.; Stanton, J. Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katt, F.; Meixner, O. A systematic review of drivers influencing consumer willingness to pay for organic food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 100, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M.; Gupta, B. Determinants of organic food consumption: A systematic literature review on motives and barriers. Appetite 2019, 143, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, M.; O’Cass, A.; Otahal, P. A meta-analytic study of the factors driving the purchase of organic food. Appetite 2018, 125, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Guo, J.; Turel, O.; Liu, S. Purchasing organic food with social commerce: An integrated food-technology consumption values perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Li, T.; Guo, J. Factors influencing consumers’ continuous purchase intention on fresh food e-commerce platforms: An organic foods-centric empirical investigation. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 50, 101103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina-Ramírez, R.; Chamorro-Mera, A.; Moreno-Luna, L. Organic and online attributes for buying and selling agricultural products in the e-marketplace in Spain. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 40, 100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, T.; Dion, P. Validating the search, experience, and credence product classification framework. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehurst, G.; Afonso, C.; Martins Gonçalves, H. Re-examining green purchase behaviour and the green consumer profile: New evidences. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 972–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Shaw, D. Who says there is an intention–behaviour gap? Assessing the empirical evidence of an intention–behaviour gap in ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 136, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Tarafder, T.; Pearson, D.; Henryks, J. Intention-behavior gap and perceived behavioral control-behavior gap in theory of planned behavior: Moderating roles of communication, satisfaction, and trust in organic food consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Phan, T.T.H.; Nguyen, N.T. Evaluating the purchase behavior of organic food by young consumers in an emerging market economy. J. Strateg. Mark. 2018, 27, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, H.; Menapace, L. Using online comments to explore consumer beliefs regarding organic food in German-speaking countries and the United States. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 83, 103912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P. Organic food online shopping in Poland. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenfetelli, R.T. Inhibitors and enablers as dual factor concepts in technology usage. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2004, 5, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Jabeen, F.; Talwar, S.; Sakashita, M.; Dhir, A. Facilitators and inhibitors of organic food buying behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 88, 104077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brach, S.; Walsh, G.; Shaw, D. Sustainable consumption and third-party certification labels: Consumers’ perceptions and reactions. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, N. Consumers’ perceived risk: Sources versus consequences. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2003, 2, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A. Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2003, 7, 101–134. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Zamora, M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J.; Parras-Rosa, M.P. Towards sustainable consumption: Keys to communication for improving trust in organic foods. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladwein, R.; Sánchez Romero, A.M. The role of trust in the relationship between consumers, producers, and retailers of organic food: A sector-based approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Product labelling in the market for organic food: Consumer preferences and willingness-to-pay for different organic certification logos. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 25, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.M.; Shakur, S.; Pham Do, K.H. Rural-urban differences in willingness to pay for organic vegetables: Evidence from Vietnam. Appetite 2019, 141, 104273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.B. Understanding the consumer’s online merchant selection process: The roles of product involvement, perceived risk, and trust expectation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S.M. The major dimensions of perceived risk. In Risk Taking and Information Handling in Consumer Behavior; Cox, D.F., Ed.; Harvard University: Boston, MA, USA, 1967; pp. 82–108. [Google Scholar]

- Nepomuceno, M.V.; Laroche, M.; Richard, M.-O. How to reduce perceived risk when buying online: The interactions between intangibility, product knowledge, brand familiarity, privacy, and security concerns. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.K.; Niraj, R.; Venugopal, P. Context-general and context-specific determinants of online satisfaction and loyalty for commerce and content sites. J. Interact. Mark. 2010, 24, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, J.-S.; Droge, C. Service quality, trust, specific asset investment, and expertise: Direct and indirect effects in a satisfaction-loyalty framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.H. Does ‘born digital’ mean ‘being global’ in characterizing Millennial consumers in a less developed country context? An empirical study in Myanmar. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 195, 122801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J. SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Caso, D.; Del Giudice, T.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Nardone, G.; Cicia, G. Explaining consumer purchase behavior for organic milk: Including trust and green self-identity within the theory of planned behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 76, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Hao, N.; Zhou, Q.; Wetzstein, M.E.; Wang, Y. Is fresh food shopping sticky to retail channels and online platforms? Evidence and implications in the digital era. Agribusiness 2019, 35, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.U.; Qiu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Shahzad, M. The impact of social media celebrities’ posts and contextual interactions on impulse buying in social commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 115, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pee, L.G.; Jiang, J.; Klein, G. Signaling effect of website usability on repurchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabner-Kräuter, S.; Kaluscha, E.A. Empirical research in online trust: A review and critical assessment. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2003, 58, 783–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, N.; Mishra, A. Mapping the electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) research: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 135, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Yu, H.; Ploeger, A. Exploring influential factors including COVID-19 on green food purchase intentions and the intention–behaviour gap: A qualitative study among consumers in a Chinese context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: The case of organic food. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 140, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S. Factors influencing organic food purchase in India—Expert survey insights. Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 902–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Yadav, N. Past, present, and future of electronic word of mouth (eWOM). J. Interact. Mark. 2021, 53, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Jabeen, F.; Tandon, A.; Sakashita, M.; Dhir, A. What drives willingness to purchase and stated buying behavior toward organic food? A stimulus–organism–behavior–consequence (SOBC) perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 125882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israeli, A.A.; Lee, S.A.; Bolden, E.C. The impact of escalating service failures and internet addiction behavior on young and older customers’ negative eWOM. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollough, M.A. The recovery paradox: The effect of recovery performance and service failure severity on post-recovery customer satisfaction. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2009, 13, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, S.G.; Raimi, K.T.; Wilson, R.; Árvai, J. Will Millennials save the world? The effect of age and generational differences on environmental concern. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 242, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Paul, J.; Bharti, K. Dispositional traits and organic food consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 121961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (Year) | Research Coverage | Drivers | Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hughner et al. [2] | 33 studies during 1991–2004 | (1) is healthier; (2) tastes better; (3) environmental concern; (4) concern over food safety; (5) concern over animal welfare; (6) supports local economy and helps to sustain traditional cooking; (7) is wholesome; (8) reminiscent of the past; (9) fashionable. | (1) rejection of high prices; (2) lack of availability; (3) skepticism of certification boards and organic labels; (4) insufficient marketing; (5) satisfaction with current food source; (6) cosmetic defects. |

| Rana and Paul [14] | 146 studies during 1985–2015 | (1) health consciousness and expectations of well being; (2) quality and safety; (3) environmental friendliness and ethical consumerism; (4) willingness to pay; (5) price and certification; (6) fashion trends and unique lifestyle; (7) social consciousness. | n.a. |

| Massey et al. [5] | 150 studies during 1991–2016 |

| n.a. |

| Kushwah et al. [4] | 89 studies during 2005–2018 |

|

|

| Katt and Meixner [3] | 138 studies during 1995–2015 |

| n.a. |

| First Quarter Respondents (n = 70) | Last Quarter Respondents (n = 70) | Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Gender | 48.6% vs. 51.4% | 48.6% vs. 51.4% | χ2 = 0.00 |

| Age | 44.29 | 43.86 | t = 0.24 |

| Education | 1.4% vs. 5.7% vs. 61.4% vs. 31.4% | 0.0% vs. 7.1% vs. 68.6% vs. 24.3% | χ2 = 2.03 |

| Marriage | 62.9% vs. 37.1% | 68.6% vs. 31.4% | χ2 = 0.51 |

| Region | 51.4% vs. 24.3% vs. 22.9% vs. 1.4% | 52.9% vs. 22.9% vs. 24.3% vs. 0.0% | χ2 = 1.07 |

| Family size | 3.21 | 3.40 | t = −0.83 |

| Monthly family income | 4052.87 | 3846.35 | t = 0.79 |

| Main constructs | |||

| Trust in producers | 3.61 | 3.75 | t = −1.30 |

| Trust in e-tailers | 3.41 | 3.58 | t = −1.48 |

| Trust in organic labels | 3.67 | 3.72 | t = −0.58 |

| Positive review sentiment | 3.50 | 3.59 | t = −0.95 |

| Financial risk | 3.45 | 3.41 | t = 0.34 |

| Product performance risk | 3.71 | 3.83 | t = −1.02 |

| Delivery risk | 3.31 | 3.47 | t = −1.42 |

| Intention to purchase organic food online | 3.76 | 3.80 | t = −0.39 |

| Purchase of organic food online | 110.15 | 104.70 | t = 0.33 |

| Reliability | Convergent Validity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR Values | Indicator Reliability | AVE Values | |

| Trust in producers [38] | 3.62 | 0.61 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.79 | |

| TPRO1 Producers take good care of the safety of organic food. | 0.91 | |||||

| TPRO2 Producers give special attention to the safety of organic food. | 0.90 | |||||

| TPRO3 Producers have the competence to control the safety of organic food. | 0.87 | |||||

| TPRO4 Producers have sufficient knowledge to guarantee the safety of organic food. | 0.87 | |||||

| TPRO5 Producers are honest about the safety of organic food. | 0.91 | |||||

| TPRO6 Producers are sufficiently open regarding the safety of organic food. | 0.88 | |||||

| Trust in e-tailers [38] | 3.45 | 0.64 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.80 | |

| TTAI1 E-tailers take good care of the safety of organic food. | 0.92 | |||||

| TTAI2 E-tailers give special attention to the safety of organic food. | 0.89 | |||||

| TTAI3 E-tailers have the competence to control the safety of organic food. | 0.92 | |||||

| TTAI4 E-tailers have sufficient knowledge to guarantee the safety of organic food. | 0.87 | |||||

| TTAI5 E-tailers are honest about the safety of organic food. | 0.88 | |||||

| TTAI6 E-tailers are sufficiently open regarding the safety of organic food. | 0.88 | |||||

| Trust in organic labels [39] | 3.64 | 0.58 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.81 | |

| TLAB1 I believe the organic food label information is true and reliable. | 0.88 | |||||

| TLAB2 I believe that the organic food label information can reflect the production and distribution process of the product. | 0.93 | |||||

| TLAB3 I think the organic food label information is consistent with the production and distribution process of the product. | 0.90 | |||||

| Positive review sentiment [40] | 3.49 | 0.55 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.78 | |

| PREW1 Online comments on the organic food are excellent. | 0.85 | |||||

| PREW2 Online comments on the organic food are good. | 0.92 | |||||

| PREW3 Online comments on the organic food are positive. | 0.88 | |||||

| PREW4 Online comments on the organic food are pleasant. | 0.87 | |||||

| Financial risk [27] | 3.34 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.80 | |

| RFIN1 I am concerned that the online payment methods may not be safe. | 0.90 | |||||

| RFIN2 I am concerned that the online price of the organic food may be too high.** | -- | |||||

| RFIN3 I am concerned that I may suffer from monetary loss due to the e-tailer’s fraudulent acts. | 0.89 | |||||

| Product performance risk [27] | 3.74 | 0.69 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.79 | |

| RPER1 I am concerned that the organic food delivered may not perform to my expectations. | 1.00 | |||||

| RPER2 I am concerned that the organic food delivered may not match the descriptions, including the pictures, given on the website. | 0.76 | |||||

| Delivery risk [27] | 3.01 | 0.89 | -- | -- | -- | |

| RDEL1 I am concerned that the organic food may be delivered without good fresh-keeping facilities. ** | ||||||

| RDEL2 I am concerned that the organic food may be delivered to a wrong address. | 1.00 | |||||

| RDEL3 I am concerned that the organic food may not be delivered in time. ** | ||||||

| Intention to purchase organic food online [38] | 3.71 | 0.64 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.91 | |

| INT1 I intend to purchase organic food online. | 0.95 | |||||

| INT2 I plan to purchase organic food online. | 0.95 | |||||

| INT3 I want to purchase organic food online. | 0.97 | |||||

| Purchase of organic food online [34] | 114.71 | 114.19 | -- | -- | -- | |

| PUR1 Monthly organic food expenditure online (monthly shopping frequency X average expenditure per purchase) | 1.00 | |||||

| Online shopping experience [41] | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.76 | |||

| EXP1 I have shopped online extensively. | 0.91 | |||||

| EXP2 I have used the Internet to shop for a long time. | 0.85 | |||||

| EXP3 I shop online frequently. | 0.86 | |||||

| Construct | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Trust in producers | ||||||||

| (2) Trust in e-tailers | 0.80 | |||||||

| (3) Trust in organic labels | 0.83 | 0.80 | ||||||

| (4) Positive review sentiment | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.66 | |||||

| (5) Financial risk | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.08 | ||||

| (6) Product performance risk | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.67 | |||

| (7) Delivery risk | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.44 | ||

| (8) Intention to purchase organic food online | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.12 | |

| (9) Purchase of organic food online | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.26 |

| Construct | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Trust in producers | 0.89 | ||||||||

| (2) Trust in e-tailers | 0.76 | 0.89 | |||||||

| (3) Trust in organic labels | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.89 | ||||||

| (4) Positive review sentiment | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.88 | |||||

| (5) Financial risk | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.10 | −0.03 | 0.90 | ||||

| (6) Product performance risk | −0.10 | −0.14 | −0.09 | −0.01 | 0.54 | 0.89 | |||

| (7) Delivery risk | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 1.00 | ||

| (8) Intention to purchase organic food online | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.50 | −0.08 | −0.02 | −0.12 | 0.95 | |

| (9) Purchase of organic food online | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.20 | −0.10 | −0.15 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 1.00 |

| Hypothesized Path | Coefficient | t-Value |

|---|---|---|

| C.V. Online shopping experience → Purchase of organic food online | 0.15 * | 2.29 |

| H1. Trust in producers → Intention to purchase organic food online | 0.14 | 1.17 |

| H2. Trust in e-tailers → Intention to purchase organic food online | −0.08 | 0.85 |

| H3. Trust in organic labels → Intention to purchase organic food online | 0.24 * | 2.30 |

| H4. Positive review sentiment → Intention to purchase organic food online | 0.32 *** | 4.55 |

| H5. Financial risk → Intention to purchase organic food online | −0.04 | 0.50 |

| H6. Product performance risk → Intention to purchase organic food online | 0.07 | 0.98 |

| H7. Delivery risk → Intention to purchase organic food online | −0.11 | 0.61 |

| H8. Intention to purchase organic food online → Purchase of organic food online | 0.18 * | 2.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeh, C.-H.; Yang, M.-H. Reexamining the Determinants of Organic Food Purchases in Online Contexts: The Dual-Factor Model Perspective. Agriculture 2025, 15, 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080883

Yeh C-H, Yang M-H. Reexamining the Determinants of Organic Food Purchases in Online Contexts: The Dual-Factor Model Perspective. Agriculture. 2025; 15(8):883. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080883

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeh, Ching-Hsuan, and Min-Hsien Yang. 2025. "Reexamining the Determinants of Organic Food Purchases in Online Contexts: The Dual-Factor Model Perspective" Agriculture 15, no. 8: 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080883

APA StyleYeh, C.-H., & Yang, M.-H. (2025). Reexamining the Determinants of Organic Food Purchases in Online Contexts: The Dual-Factor Model Perspective. Agriculture, 15(8), 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15080883