The Difficult Decision of Using Biopesticides: A Comparative Case-Study Analysis Concerning the Adoption of Biopesticides in the Mediterranean Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- What are the main limitations and opportunities perceived by the farmers that affect the use of biopesticide in the region?

- -

- What are the specific and more general trends that characterize the adoption of biopesticides within and without the EU?

- -

- What are the possible areas of intervention to facilitate the implementation of these products?

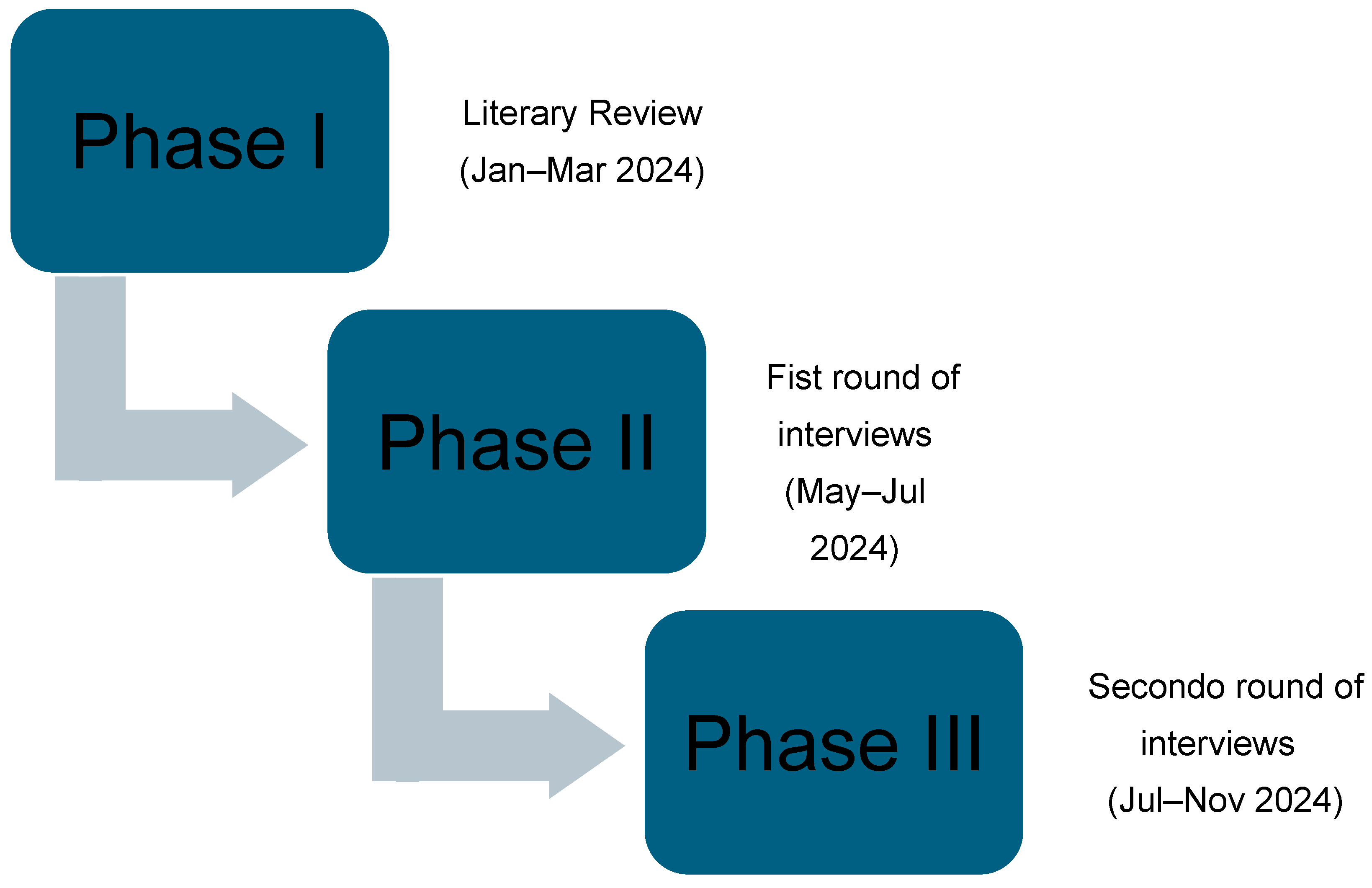

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. The Trends in the Literature

3.2. Dynamics in the Ebro Delta

3.2.1. Characteristics of Producers and Agricultural Enterprises

3.2.2. Cultivated Crops, Pests, and Products Used

3.2.3. Criteria for Choosing Products and Plant Care Methods

3.2.4. Biopesticides and Knowledge

3.2.5. Reasons Limiting the Adoption of Biopesticides

3.2.6. Reasons Favoring the Adoption of Biopesticides

3.3. Dynamics in the Tunisian Northeastern Regions

3.3.1. Characteristics of Producers and Agricultural Enterprises

3.3.2. Cultivated Crops, Pests, and Products Used

3.3.3. Criteria for Choosing Products and Plant Care Methods

3.3.4. Biopesticides and Knowledge

3.3.5. Reasons Limiting the Adoption of Biopesticides

3.3.6. Reasons Favoring the Adoption of Biopesticides

3.4. Dynamics in the Turkish Province of Adana

3.4.1. Characteristics of Producers and Agricultural Enterprises

3.4.2. Cultivated Crops, Pests, and Products Used

3.4.3. Criteria for Choosing Products and Plant Care Methods

3.4.4. Biopesticides and Knowledge

3.4.5. Reasons Limiting the Adoption of Biopesticides

3.4.6. Reasons Favoring the Adoption of Biopesticides

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview

4.2. Pull Factors

4.3. Push Factors

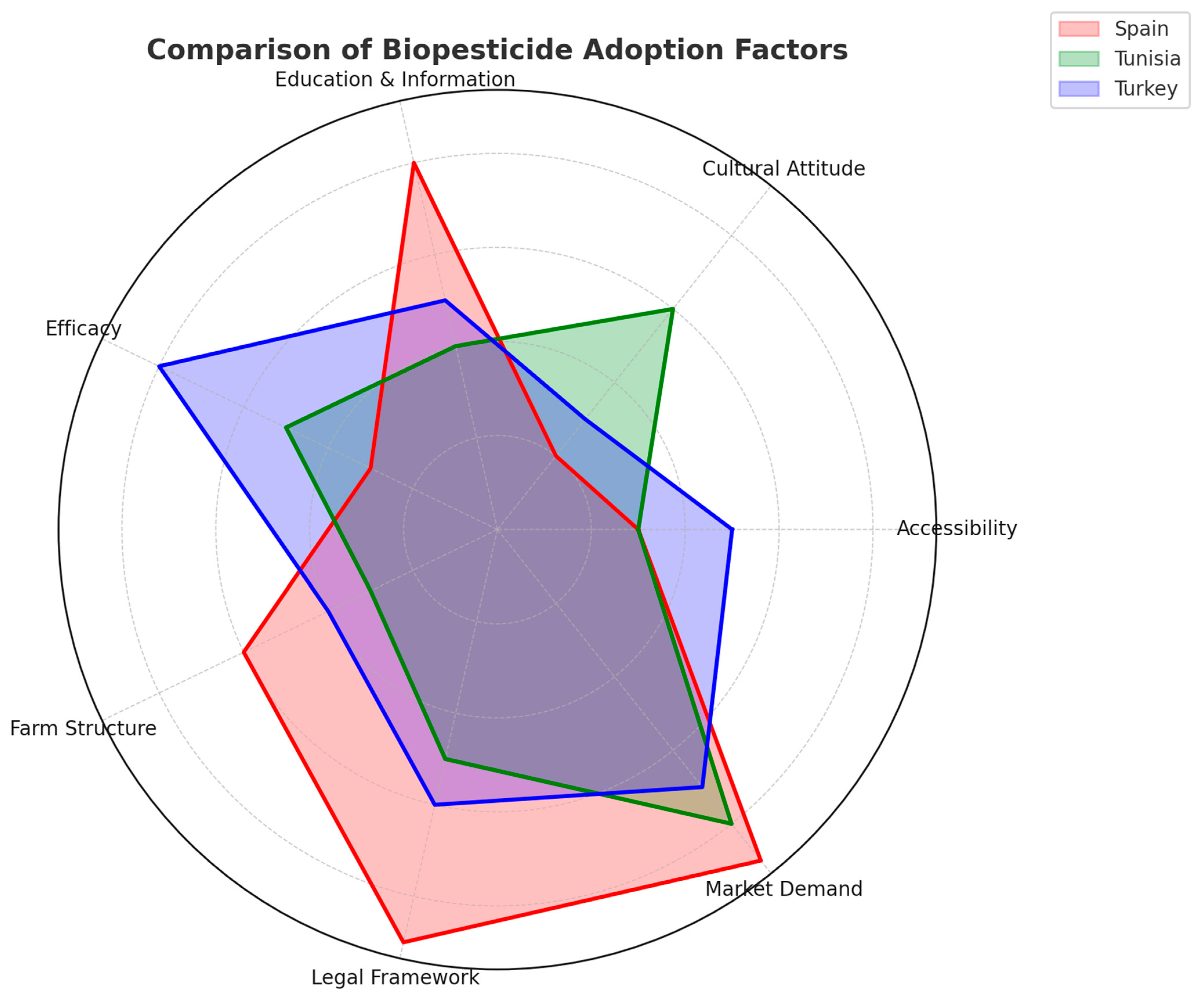

4.4. The Model

- Accessibility, which describes the availability of biopesticides in the market, with the extremes being “Limited” and “Wide”.

- Cultural Attitude, which reflects farmers’ openness to change, ranging from “Conservative Attitude” to “Innovative Attitude”.

- Education and Information, which represent the availability of training and knowledge on biopesticide use, with the extremes being “Scarce Information” and “Wide Information”.

- Efficacy, which refers to the perceived effectiveness of biopesticides for local crops, ranging from “Low Effectiveness” to “High Effectiveness”.

- Farm Structure, which describes the economic and entrepreneurial stability of farms, with the extremes being “Fragile Structure” and “Strong Structure”.

- Legal Framework, which assesses the strength of legislative measures enforcing biopesticide use, ranging from “Lax Framework” to “Strong Framework”.

- Market Demand, which represents consumer interest in organic or sustainable products, with the extremes being “Low Demand” and “High Demand”.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questions |

| 1. Pesticide Selection and Usage |

| - Do you use pesticides in your agricultural work? If so, which ones? |

| - How did you choose the pesticides you use? |

| 2. Training and Experience |

| - How did you learn to use these pesticides? |

| - Have you received any specific training? By whom? |

| 3. Biopesticides |

| - What is a biopesticide? |

| - Have you ever used biopesticides? |

| If YES: |

| - Have you received any specific training on how to use it? By whom? |

| - What are the main factors that limit a more common use of biopesticides? |

| If NOT: |

| - Why don’t you use them? |

| - Would you be interested in using them? Why? |

| 4. Future Outlook |

| - What’s the future of agriculture? |

| - How do you foresee the future of your work? |

Appendix B

| Question |

| Name |

| Surname |

| Can you introduce your farm? |

| 1.1. What type of crops do you have? |

| 1.2. Have you always cultivated these trees, or have you changed? Do you plan to change? Why? |

| 1.3. How many hectares do you have for each crop? |

| 1.4. What type of business is it (family-run/personal/cultivated on behalf of others, etc.)? |

| 1.5. What type of irrigation do you use (well/canal/river/dry farming, etc.)? |

| 1.6. How is the quality of your land? |

| 1.7. How is the quality of the water available to you? |

| What are the main difficulties you encounter in your work? |

| 2.1. Do you recall moments of particular difficulty in the past? Did your grandparents or parents tell you about them? |

| 2.2. At present, what causes you the most problems? |

| What are the main pests affecting your crops? |

| 3.1. Have the pests always been present, or are they recent? |

| 3.2. What remedies did your predecessors adopt against pests? |

| 3.3. What remedies do you use today for different pests? |

| 3.4. What products do you use? How do you apply them? |

| 3.5. How do you decide which products to use and how to apply them? |

| 3.6. What methods do you use besides product application? |

| 3.7. Do you think there are enough tools for pest prevention? |

| 3.8. If yes, why?/If no, why? |

| 3.9. Do you think the products you use have an impact on the environment around you? If yes, what impact? |

| 3.10. Do you think the products you use have an impact on your health? What precautions do you take? |

| Do you feel the consequences of climate change in this region? |

| 4.1. If yes, what are they? |

| 4.2. If yes, how do you organize to deal with them? |

| What type of agriculture do you practice (conventional, organic, integrated, etc.)? |

| 5.1. Why did you choose this type of agriculture? |

| 5.2. Are you satisfied with your choice? Would you like to change? Are you making any changes? |

| 5.3. If yes, why?/If no, why? |

| 5.4. Why didn’t you choose another type of agriculture? |

| 5.5. Do you have any type of certification for quality/origin/method of cultivation? Does your cooperative have any? |

| How did you learn your job? From family? Through studies? From personal experience? |

| 6.1. If you studied: Do you think the education you received helped you in the practical work? |

| 6.2. Did you receive specific training for pest control? What kind of pest management was taught in training centers? What was taught in the family? |

| 6.3. Are there differences in farming methods between different generations of your family or in the area? |

| 6.4. Is there an exchange of skills and advice among neighbors and producers in the area? |

| What happens with damaged products? |

| 7.1. Are they harvested or left in the field? |

| 7.2. Does the quality/price change? |

| 7.3. What do you think about it? |

| How do you market your products? |

| 8.1. Are you part of a cooperative? |

| 8.2. If yes, why? What agreements do the members have for harvesting? And for selling the product? |

| 8.3. If yes, do you know to whom the cooperative sells the product? Is it for local, national, or international trade? |

| 8.4. If no, why not? |

| 8.5. If no, how do you sell your products? To a wholesale company? To small shops? Online? By word of mouth? |

| 8.6. How much product do you sell annually? |

| 8.7. Are you satisfied with the income in economic terms? |

| 8.8. If yes, why?/If no, why? |

| 8.9. What difficulties do you encounter in the market? |

| Do you receive any support or subsidies for your work? |

| 9.1. What do you think about current agricultural regulations? |

| Does your land/your trees hold emotional or symbolic value for you? |

| 10.1. If yes, what is it? |

| How do you see the future of your business? |

| 11.1. Are there any young people who will continue after you? |

| How do you see the future of agriculture in this area? |

| 12.1. Why? |

| 12.2. What do you think could improve the conditions of agriculture? |

References

- Kilby, P. Green Revolution: Narratives of Politics, Technology and Gender; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-367-67021-4. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Transforming Food and Agriculture to Achieve the SDGs; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/d7e5b4ae-80b6-4173-9adf-6f9f845be8a1/content (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Kamil, M.; Naji, M.A. Use of Bio-Pesticide—New Dimension and Challenges for Sustainable Date Palm Production. In Proceedings of the IV International Date Palm Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 15–17 March 2010; Acta Horticulturae: Korbeek-Lo, Belgium, 2010; pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrone, P.G. Status of the Biopesticide Market and Prospects for New Bioherbicides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyel, S.A.; Ruidas, S.; Roy, P.; Mondal, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Hazra, D. Biopesticides as Eco-Friendly Substitutes to Synthetic Pesticides: An Insight of Present Status and Future Prospects with Improved Bio-Effectiveness, Self-Lives, and Climate Resilience. Int. J. Educ. Stud. Policy 2022, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Niche Research. The Global Expansion of Organic Farming Presents Significant Growth Opportunities for the Biorational Pesticides Market in 2023. Available online: https://www.einpresswire.com/article/672793396/organic-farming-sector-is-expanding-globally-creating-a-significant-opportunity-growth-of-biorational-pesticides-market (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Damalas, C.; Koutroubas, S. Current Status and Recent Developments in Biopesticide Use. Agriculture 2018, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusar Poli, E.; Fontefrancesco, M.F. Pesticide: A Contemporary Cultural Object. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Pathways for Agrifood Systems Transformation and Regional Cooperation in the Mediterranean; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138994-2. [Google Scholar]

- Damalas, C.A.; Koutroubas, S.D. Pesticides in Crop Production: Physiological and Biochemical Action; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-119-43223-4. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaiculescu, A.; Varrone, C. Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Alternatives to Reduce the Use of Pesticides. In Pesticides in the Natural Environment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 329–364. ISBN 978-0-323-90489-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre, M.-N.; Adou, A.I.; Brudey, A.; Sylvestre, M.; Pruneau, L.; Gaspard, S.; Cebrian-Torrejon, G. (Alternative Approaches to Pesticide Use): Plant-Derived Pesticides. In Biodiversity, Functional Ecosystems and Sustainable Food Production; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 141–182. ISBN 978-3-031-07433-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dönmez, D.; Isak, M.A.; İzgü, T.; Şimşek, Ö. Green Horizons: Navigating the Future of Agriculture through Sustainable Practices. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudsk, P.; Mathiassen, S.K. Pesticide Regulation in the European Union and the Glyphosate Controversy. Weed Sci. 2020, 68, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, L.; Oehl, M.; Lombardi, T.; De Michele, V.R.; Schmitt, N.; Verweire, D.; Balmer, D. Innovations towards Sustainable Olive Crop Management: A New Dawn by Precision Agriculture Including Endo-Therapy. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1180632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheuk, F.; Basiouni, S.; Shehata, A.A.; Dick, K.; Hajri, H.; Lasram, S.; Yilmaz, M.; Emekci, M.; Tsiamis, G.; Spona-Friedl, M.; et al. Status and Prospects of Botanical Biopesticides in Europe and Mediterranean Countries. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.; Grzywacz, D.; Curcic, I.; Scoates, F.; Harper, K.; Rice, A.; Paul, N.; Dillon, A. A Novel Formulation Technology for Baculoviruses Protects Biopesticide from Degradation by Ultraviolet Radiation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, O.; Weekers, F.; Thonart, P.; Tesch, E.; Kuenemann, P.; Jacques, P. Limiting Factors of Mycopesticide Development. Biol. Control 2020, 144, 104220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenibo, E.O.; Christian, R.; Matambo, T.S. Biopesticide Commercialization in African Countries. In Development and Commercialization of Biopesticides; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 297–328. ISBN 978-0-323-95290-3. [Google Scholar]

- Khursheed, A.; Rather, M.A.; Jain, V.; Wani, A.R.; Rasool, S.; Nazir, R.; Malik, N.A.; Majid, S.A. Plant Based Natural Products as Potential Ecofriendly and Safer Biopesticides: A Comprehensive Overview of Their Advantages over Conventional Pesticides, Limitations and Regulatory Aspects. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 173, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, K.; Dobbins, C.; Edgar, L.; Borges, B.; Jones, S.; Hernandez, J.; Birnbaum, A. A Cross Case Synthesis of the Social and Economic Development of Three Guatemalan Coffee Cooperatives. Adv. Agric. Dev. 2020, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runeson, P.; Höst, M. Guidelines for Conducting and Reporting Case Study Research in Software Engineering. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2009, 14, 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacewicz, J. What Can You Do With a Single Case? How to Think About Ethnographic Case Selection Like a Historical Sociologist. Sociol. Methods Res. 2022, 51, 931–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayeck, R.Y. Is Microethnography an Ethnographic Case Study? And/or a Mini-Ethnographic Case Study? An Analysis of the Literature. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231172074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Nasr, R.; Baudelaire, E.; Dicko, A.; El Ferchichi Ouarda, H. Phytochemicals, Antioxidant Attributes and Larvicidal Activity of Mercurialis annua L. (Euphorbiaceae) Leaf Extracts against Tribolium Confusum (Du Val) Larvae (Coleoptera; Tenebrionidae). Biology 2021, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantero, E.; Matallanas, B.; Callejas, C. Current Status of the Main Olive Pests: Useful Integrated Pest Management Strategies and Genetic Tools. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, S.; Idris, A.B.; Ayvaz, A.; Temizgül, R.; Çetin, A.; Hassan, M.A. Genome Mining of Bacillus thuringiensis Strain SY49.1 Reveals Novel Candidate Pesticidal and Bioactive Compounds. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusar Poli, E.; Fontefrancesco, M.F. Trends in the Implementation of Biopesticides in the Euro-Mediterranean Region: A Narrative Literary Review. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2024, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcorran, M.A.; Austin, E.J.; Behrends, C.N.; Briggs, E.S.; Frost, M.C.; Juarez, A.M.; Frank, N.D.; Healy, E.; Prohaska, S.M.; LaKosky, P.A.; et al. Syringe Service Program Perspectives on Barriers, Readiness, and Programmatic Needs to Support Rollout of the COVID-19 Vaccine. J. Addict. Med. 2022, 17, E36–E41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, M.R.; Githens-Mazer, G.; Lovegrove, C.; Oram, R.; Shepherd, M. Renal Nurses’ Lived Experiences of Discussions about Sexuality. J. Kidney Care 2019, 4, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbo, I.E.; Johnson, R.C.; Sopoh, G.E.; Nichter, M. The Gendered Impact of Buruli Ulcer on the Household Production of Health and Social Support Networks: Why Decentralization Favors Women. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakidou, A.; Fouskas, T.; Koulierakis, G.; Liarigkovinou, A. Unravelling the Effects of Burnout on Mental Health Nurses: A Qualitative Approach. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Paradig. 2024, 44, 1040–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, C.R. Sample Size for Qualitative Research. Qual. Manag. Represent. 2016, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Nie, F.; Jia, X. Production Choices and Food Security: A Review of Studies Based on a Micro-Diversity Perspective. Foods 2024, 13, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.; Lear, L.; Wilson, E.O. Silent Spring; Fortieth Anniversary Edition; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-618-25305-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nading, A.M. Living in a Toxic World. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2020, 49, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, I. Climate Change, Social Policy, and Global Governance. J. Int. Comp. Soc. Policy 2013, 29, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Díaz, F.J. El mercado de los bioproductos. Tecnologías aplicadas para la producción sostenible de alimentos. Obs. Tecnológico Plataforma Tierra 2021, Junio, 1–22. Available online: https://www.plataformatierra.es/innovacion/observatorio-tecnologico-bioproductos-2021-06/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Prados, J.L.A.; Guijarro Díaz-Otero, B. Sustancias activas y productos ftosanitarios de bajo riesgo. Marco legislativo, requisitos de datos y evaluación, importancia y oportunidades. Phytoma España 2020, 323, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, R.; Biondi, A. Releasing Natural Enemies and Applying Microbial and Botanical Pesticides for Managing Tuta Absoluta in the MENA Region. Phytoparasitica 2021, 49, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Dougoud, J.; Bateman, M.; Wood, T. Étude sur la Protection des Cultures dans les Pays où le Programme «Centres d’innovations Vertes Pour le Secteur Agro-Alimentaire» est actif. Rapport National Pour le Centre «Innovation Pour l’agriculture et l’agro-Alimentaire (IAAA)» en Tunisie. 2018. Available online: https://www.cabi.org/wp-content/uploads/Country-report-Tunisia.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- World Bank. Tunisia—Agricultural Support Services Project (English). 2009. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/841801474852517684/tunisia-agricultural-support-services-project (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Ksentini, I.; Jardak, T.; Zeghal, N. Bacillus thuringiensis, deltamethrin and spinosad side-efects on three Trichogramma species. Bull Insectology 2010, 63, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dhouibi, M.H.; Jemmazi, A. Stratégies de lutte biologique en entrepôt contre le ravageur de la datte, Ectomyelois ceratoniae. Fruits 1996, 51, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- İksad, Y.; Chapter, I. Agricultural Studies on Different Subjects; Iksad: Ankara, Turkey, 2021; pp. 3–24. Available online: https://iksadyayinevi.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/AGRICULTURAL-STUDIES-ON-DIFFERENT-SUBJECTS.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Yıllar itibarıyla Bitki Koruma Ürünlerinin (Gruplara Ayrılmış Olarak) Kullanım Miktarları, 2006–2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.tarimorman.gov.tr/GKGM/Belgeler/DB_Bitki_Koruma_Urunleri/Istatistik/Yillar_Itibariyla_BKU_Kullanim_Miktar_2006-2022.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Bitki Sağlığındaki dost Mikroorganizmalar Çalıştayı; Tarım ve Orman Bakanlığı: Ankara, Turkey, 2020. Available online: https://www.tarimorman.gov.tr/TAGEM/Belgeler/%C3%87ALI%C5%9ETAY%20K%C4%B0TAP%2021%20ARALIK%202020.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Cotta, B. Unpacking the Eco-Social Perspective in European Policy, Politics, and Polity Dimensions. Eur. Political Sci. 2024, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, L.; Van Der Werf, W.; Tittonell, P.; Wyckhuys, K.A.G.; Bianchi, F.J.J.A. Neonicotinoids in Global Agriculture: Evidence for a New Pesticide Treadmill? Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, S.O.; Schmidpeter, R.; Zu, L. The Future of the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Business Perspectives for Global Development in 2030, CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-21153-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.R. Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity, 1st ed.; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-393-08891-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, J.-F. Degrowth and Critical Agrarian Studies. J. Peasant. Stud. 2020, 47, 235–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.; Edwards, F. Food for Degrowth Perspectives and Practices; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-0-367-65067-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkowski, B. Degrowth, Organic Agriculture and GMOs: A Reply to Gomiero (2017, JCLEPRO). J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 904–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, T. Agriculture and Degrowth: State of the Art and Assessment of Organic and Biotech-Based Agriculture from a Degrowth Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1823–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, T. The Politics of Permaculture; FireWorks; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-0-7453-4280-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lindellee, J.; Alkan Olsson, J.; Koch, M. Operationalizing Sustainable Welfare and Co-Developing Eco-Social Policies by Prioritizing Human Needs. Glob. Soc. Policy 2021, 21, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M. The State in the Transformation to a Sustainable Postgrowth Economy. Environ. Politics 2020, 29, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvin, J.-M.; Laruffa, F. Towards a Capability-Oriented Eco-Social Policy: Elements of a Normative Framework. Soc. Policy Soc. 2022, 21, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coote, A. Towards a Sustainable Welfare State: The Role of Universal Basic Services. Soc. Policy Soc. 2022, 21, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Key Characteristics | Challenges | Opportunities | Main References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | - Biopesticide market still niche but growing - Collaboration between public and private sectors - Stricter regulations on synthetic pesticides | - Slow, widespread adoption of biopesticides - Pressure from the conventional market regarding production costs | - Ongoing increase in the supply of authorized active substances (38 in 2020) - Potential to expand public–private collaboration for research and development | [4,39,40] |

| Tunisia | - Widespread use of traditional pest management methods - Increasing reliance on chemical pesticides - Regulations aimed at limiting excessive pesticide use | - Traditional methods are insufficient to address the wide range of infestations - Increased use of chemical pesticides despite existing restrictive regulations | - Strengthening sustainable alternatives by leveraging existing regulations - Enhancing traditional knowledge along with modern methods | [41,42,43,44,45] |

| Turkey | - Dominance of small and medium-sized farms - Fragmented regulatory system - Recent reduction in chemical pesticide production | - Limited access to modern agronomic knowledge - Difficulty adapting to regulations due to fragmentation | - Growing adoption of biopesticides (facilitated by the reduction in chemical pesticide production) - Potential training programs and technical support for SMEs | [46,47,48] |

| Section | Ebro Delta (Spain) | Nabeul (Tunisia) | Adana (Turkey) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of Producers and Agricultural Enterprises | Farm sizes: Average 11.8 ha, range 1–40 ha. (mix of inherited and rented land) Demographics: Producers mostly male, aged 28–85 years (average 54). Training: High prevalence of agronomic training; most have agricultural engineering qualifications. Additional activities: Many supplement farming with consulting or agricultural services. Farm structure: Family-run farms are common. | Farm sizes: Average 15 ha, range < 2 to 180 ha. Demographics: Producers mostly male, aged 30–78 years (average 55). Training: A mix of formal agronomic training and practical experience. Additional Activities: Farmers often engage in other activities, such as mechanics, citrus wholesaling, or consultancy. Farm structure: Family-run farms with generational continuity (up to the third generation). | Farm sizes: Range 5–242 ha. Demographics: Predominantly male, aged 29–72 years (average 46). Training: Half of the farmers hold only primary education, experience for trial and error Additional activities: Farm structure: Family-run farms with generational continuity |

| Cultivated Crops, Pests, and Products Used | Main crops: Citrus and olives. Main pests: California red scale, aphids, whiteflies, mealybugs, two-spotted mites, Mediterranean fruit fly, Texas citrus mite, olive fruit fly, olive moth, peacock leaf spot, olive psyllid, red mites, scale insects. Pesticide usage: overall conventional pesticides, often with integrated management approaches (exceptions: no products at all, self-made products, organic products). Common substances: Acetamiprid, pyriproxyfen, pyridaben, hexythiazox, spirotetramat, glyphosate, copper oxychloride, copper sulfate. Biological inputs: Mineral and paraffinic oils used by some producers (approved for biological agriculture). | Main crops: Citrus, olives, fodder, greenhouse vegetables, organic roses. Main pests: Aphids, mites, leaf miners, Mediterranean fruit flies, whiteflies, scales, mealybugs, carob moths, Prays citri, Tristeza virus, California red scale, Botryosphaeria dothidea. Pesticide usage: overall conventional pesticides Common substances: abamectin, acetamiprid, deltamethrin, general fungicides, herbicides. Biological inputs: oil, copper, sulfur. | Main crops: Citrus (oranges, lemons, mandarins). Main pests: Mediterranean fruit fly, moths, mites, citrus rust mite. Pesticide usage: Heavy reliance on chemical pesticides. Common substances: Algomeg, “Zenk Medicine”, “Rust Medicine”, “Mealybug Medicine”, V-93, PAs, lice medicine. Biological inputs: oil |

| Criteria for Choosing Products and Plant Care Methods | Guidance and support: Guided by agronomists, cooperative membership provides technical stability and support. Selection criteria: Efficacy, price, past experience, market niche, plant care Training: Phytosanitary Applicator Certificate mandatory; younger farmers receive special training for subsidies, school and university, family experience, and occasional collaborations with research centers (e.g., testing mass traps and sustainable remedies). Information sources: Internet, courses, cooperatives, agronomists. | Guidance and support: Limited access to specialized technical support; some consult independent agronomy technicians or neighbors. Selection criteria: Efficacy, price, reduced toxicity for pollinators Training: Limited formal training; reliance on informal learning and self-training. Information sources: Phytosanitary guides, CTAB (for organic farming), and the internet. | Guidance and support: Decisions guided by agronomists, pesticide dealers, and familiar experience Selection criteria: Price, resistance avoiding Training: learning through trial and error and peer recommendations. Information sources: Peer recommendations supplement agronomist and dealer advice. |

| Biopesticides and Knowledge | Awareness: The great majority is familiar with biopesticides. Biopesticides are associated with biologically derived active substances, but the depth of understanding varies. Usage: The majority use biopesticides or organic products along with conventional products. Frequent biopesticides: Spinosad, Bacillus thuringiensis-based products. In addition: Copper sulfate, copper oxychloride, sulfur, and mineral/paraffinic oils. | Awareness: Most producers define biopesticides as natural-origin, non-toxic products suited for organic farming. One-third are unfamiliar with the term. Usage: Some farmers use biopesticides or organic products along with conventional products. Frequent biopesticides: Spinosad (for Ceratitis capitata control) and Bactospeine (Bacillus thuringiensis for carob moth or Prays citri). In addition: copper, sulfur, and mineral oils (allowed in organic farming). | Awareness: The majority lack awareness of biopesticides; the term was often first heard during interviews. Usage: Few have tried and abandoned biopesticides. Frequent biopesticides: None. In addition: oil. |

| Reasons Limiting the Adoption of Biopesticides | High cost of biopesticides. Limited availability in the market. Lack of information and awareness about biopesticides. Skepticism about their effectiveness. Perception that biopesticides are less effective than conventional pesticides. The need for repeated treatments increases labor and cost. Reliance on chemicals. | High cost of biopesticides. Limited availability in the market. Lack of knowledge and training on biopesticides. Perception that biopesticides are unnecessary for conventional farming. Satisfaction with conventional pesticides. Minimal technical support for adopting alternative methods. Economic constraints reinforce reliance on conventional practices. | Lack of knowledge about biopesticides. Economic constraints. Reliance on conventional methods. Generational practices that favor continuity over change. Risk aversion discourages major innovations. Limited promotion of biopesticides. Market availability of alternatives is insufficient. |

| Reasons for Adopting Biopesticides | Legal restrictions on chemicals. Market limitations on chemicals. Increased demand for sustainable and environmentally friendly products. Health benefits for humans and plants. Territorial promotion projects. Experimentation with alternative practices. Adoption of integrated or organic farming methods. | Lower residue levels for exports. Alignment with organic market demands. | Addressing pesticide resistance Meet organic market demands. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fusar Poli, E.; Campos, J.M.; Martínez Ferrer, M.T.; Rahmouni, R.; Rouis, S.; Yurtkuran, Z.; Fontefrancesco, M.F. The Difficult Decision of Using Biopesticides: A Comparative Case-Study Analysis Concerning the Adoption of Biopesticides in the Mediterranean Region. Agriculture 2025, 15, 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060640

Fusar Poli E, Campos JM, Martínez Ferrer MT, Rahmouni R, Rouis S, Yurtkuran Z, Fontefrancesco MF. The Difficult Decision of Using Biopesticides: A Comparative Case-Study Analysis Concerning the Adoption of Biopesticides in the Mediterranean Region. Agriculture. 2025; 15(6):640. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060640

Chicago/Turabian StyleFusar Poli, Elena, José Miguel Campos, María Teresa Martínez Ferrer, Ridha Rahmouni, Souad Rouis, Zeynep Yurtkuran, and Michele Filippo Fontefrancesco. 2025. "The Difficult Decision of Using Biopesticides: A Comparative Case-Study Analysis Concerning the Adoption of Biopesticides in the Mediterranean Region" Agriculture 15, no. 6: 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060640

APA StyleFusar Poli, E., Campos, J. M., Martínez Ferrer, M. T., Rahmouni, R., Rouis, S., Yurtkuran, Z., & Fontefrancesco, M. F. (2025). The Difficult Decision of Using Biopesticides: A Comparative Case-Study Analysis Concerning the Adoption of Biopesticides in the Mediterranean Region. Agriculture, 15(6), 640. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060640