1. Introduction

The ultimate aim of economic and social development is to increase residents’ happiness, and achieving happiness is a major goal for most social residents. With the rapid development of information technology and the accelerated popularization of Internet applications, unprecedented and profound changes have taken place in human production and lifestyle. The popularity and use of the Internet have greatly facilitated people’s activities, such as shopping, learning, entertainment, social interaction, and information acquisition [

1]. According to the Digital 2024 Global Overview Report released by Meltwater and We Are Social [

2], by early 2024, there were 5.35 billion Internet users and 5.61 billion mobile phone users globally, accounting for 66.6% and 69.4% of the world’s population, and 5.04 billion active social media users across the world, 62.3% of the global population, with people spending an average of 2 h and 23 min a day on social media platforms. The 2023 Global Happiness Report announced by Lululemon [

3] found that 65% of respondents think that improving happiness is one of their life’s priorities, and it is believed that digital tools play a key role in determining an individual’s happiness [

4].

Ameliorating the well-being of rural residents is one of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [

5]. In terms of subjective well-being, the theory of happiness economics points out that humans’ happiness and sustainable social development should be the driving force and purpose of economic development, while Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory explains the formation mechanism of happiness from the perspective of psychological needs. Together, they constitute an “objective-subjective” two-dimensional analytical framework. As a developing country, China is faced with the problems of unbalanced regional development and rural underdevelopment [

6]. Improving the welfare of rural residents is an important goal in China’s economic and social development. Subjective well-being (SWB) is defined as the subjective cognition and degree of satisfaction that an individual has towards their quality of life. As a “new quality productive force”, digital technology has become a powerful driver in boosting the rural economy and residents’ well-being. Rural residents can increase social communication, create consumption value, engage in recreation, and gain information by mastering digital technologies, which bring development opportunities and digital well-being to residents in rural areas, which then promotes the development of a sustainable digital society [

7]. In recent years, China has vigorously endeavored to bridge the digital divide by providing equal access to digital technology for disadvantaged groups and facilitating their integration into digital society, thereby reducing their sense of relative deprivation and promoting social equity. This effort holds significant theoretical value and practical implications for enhancing global well-being.

The application and promotion of digital technology have permeated every aspect of society, serving as a pivotal catalyst and inherent driving force for economic and social advancement [

8,

9]. The existing literature on the digital economy mainly focuses on four aspects. The first is the positive impact of digital infrastructure on regional development. Broadband infrastructure not only contributes to urban innovation [

10] but also has a positive impact on economic development, employment, medical care, education, and other aspects of rural areas [

11,

12]. The second aspect pertains to the positive impact of digital technology on the transformation and advancement of enterprises, organizations, and governments. The development of digital technology boosts the digital transformation and upgrading of enterprises [

13], which also enhances the research and development capabilities for innovation within enterprises, promotes corporate performance [

14], and creates new business models [

8]. The utilization of contemporary information technology enables government departments to achieve digital services such as process optimization, information sharing, and enhanced convenience. As a result, this facilitates the optimization of government operational modes [

15,

16]. The third aspect relates to the role of digital technology in facilitating economic and social development. The advancements in areas such as big data, artificial intelligence, blockchain, and other cutting-edge technologies are instrumental in driving the transformation of both traditional and emerging industries [

17], reducing industrial transaction costs [

16,

18], optimizing the allocation of market resources [

19], and improving the availability of products or services [

20]. The fourth aspect is the impact of digital technology on residents’ lives. The literature suggests that digital technology offers individuals access to educational and communication channels; enhances workers’ skills and capabilities through online recruitment, network-based education, and other platforms; and fosters employment opportunities and entrepreneurial endeavors among residents [

21]. In addition, the development of digital technology reinforces people’s social connections [

22], unleashes the vitality of demand, and optimizes the consumption structure [

19].

The concept of subjective well-being reflects individuals’ personal perception and contentment regarding the overall quality of their lives. SWB serves as a crucial welfare indicator [

23], progressively evolving into a manifestation of welfare. To address the relative scarcity of subjective well-being [

24], the enhancement of residents’ happiness has emerged as a pressing concern across all sectors of society. Numerous studies contend that income and consumption constitute the primary determinants influencing happiness [

25,

26]. Furthermore, researchers have argued for factors that influence the subjective well-being of residents in Europe, Spain, and other regions, including health, broadband access, and education [

12,

27,

28]. The subjective well-being of residents can be influenced by various external factors, such as employment and entrepreneurship, the ecological environment, and government support policies [

6,

29,

30].

With the increasing role of the Internet in daily life, it is vital to understand its impact on individual well-being [

31]. The impact of digital technology on individual well-being has gradually garnered attention [

32], particularly the impact of digital literacy, which reflects individuals’ attitudes, abilities, and thinking regarding the effective use of digital tools and equipment, as well as the utilization of digital resources. The presence of a robust information and communication technology infrastructure plays a pivotal role in augmenting residents’ income levels [

33]. The popularization of digital technologies facilitates the upgrading of consumption, wherein conspicuous consumption and increased social connections cater to people’s material and spiritual needs, thereby enhancing residents’ well-being [

34]. The advancement of network technology enables individuals to access information, knowledge, and other resources more conveniently, contributing to greater subjective well-being [

35]. The implementation of public policies aimed at promoting the utilization of digital technologies has a discernible impact on mitigating the digital divide among residents.

The existing literature mostly studies the relationship between external factors, such as digital technology infrastructure construction and digital technology popularization, and single aspects, such as residents’ income, consumption, and social demand. These studies focus on the impact of objective factors other than technology users on the objective well-being of residents. The relationship between the intrinsic digital literacy of residents themselves and their own subjective well-being is ignored. Improving the well-being of rural residents in China is of great significance in promoting agricultural modernization, narrowing the urban–rural gap, maintaining social stability, and achieving common prosperity, and is a key measure to achieve the country’s long-term development goals. The utilization of digital technology enhances the well-being of rural residents by facilitating their access to digital benefits and fostering balanced regional development. Thus, the relationship between the digital literacy of rural residents and their well-being is the key point of this study.

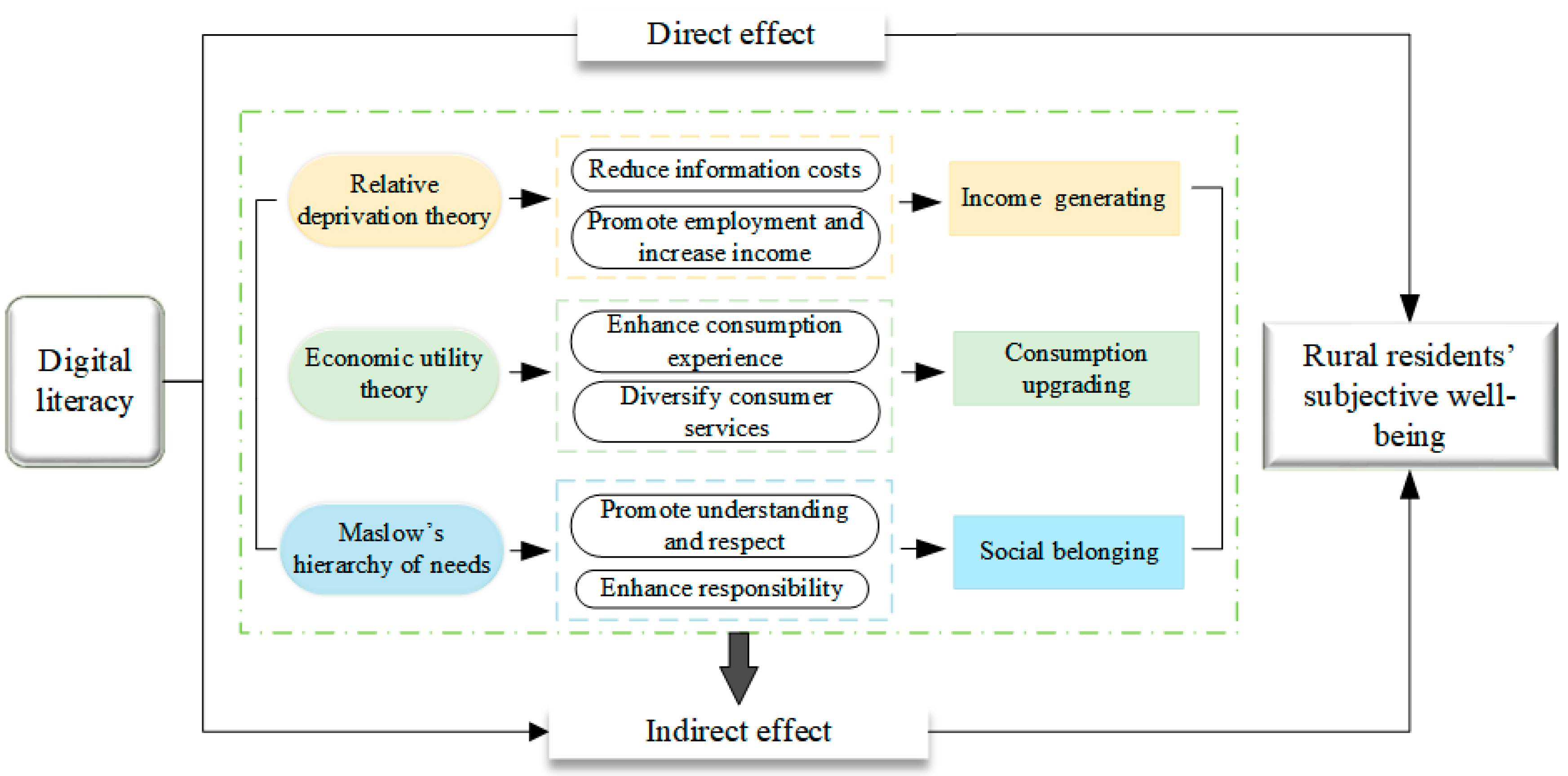

Using the questionnaire data of the China Family Group Study (CFPS) conducted by the China Social Science Survey Center of Peking University in 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020, this study uses the principal component analysis method to measure the digital literacy of Chinese rural residents from six dimensions, Internet access, digital learning, work, social interaction, entertainment, and business activities, to investigate the relationship between it and subjective well-being. The results indicate that rural residents’ digital literacy positively impacts their subjective well-being. Specifically, for every 1% increase in the digital literacy level of rural residents, there is a notable 0.048% increase in their subjective well-being, which remains significant even after conducting robustness tests. Furthermore, additional tests reveal that the impact of digital literacy on rural residents’ well-being varies across natural and social characteristics. In particular, it has a more pronounced effect on individuals residing in central and western regions, young and middle-aged groups, males, those with lower education levels, and those with strong social relational networks. Moreover, by incorporating per capita income, cultural consumption as a proportion of total consumption, and rural residents’ self-evaluation of personal relationships into the regression equation analysis, we examine how digital literacy influences subjective well-being among rural residents. The results demonstrate that digital literacy can enhance rural residents’ subjective well-being through its effects on income generation, consumption upgrading, and social belonging.

Our contributions are as follows: First, we take the subjective well-being of rural residents as the research object, which enriches the connotation of rural residents’ well-being. Well-being encompasses both objective welfare and subjective experiences, yet existing studies predominantly examine residents’ well-being from the perspective of objective indicators such as income and consumption. Given their relatively vulnerable status, there is a lack of research exploring rural residents’ subjective perceptions and satisfaction levels regarding their quality of life. Second, we construct the measurement index of digital literacy from the information technology level to provide a new perspective for studying the factors affecting residents’ subjective well-being. The existing literature has paid limited attention to the factors influencing residents’ subjective well-being. By examining the relationship between digital literacy in accessibility to digital technology and rural residents’ subjective well-being, we aim to enhance the comprehension of the influencing factors of rural residents’ well-being and expand the research framework on antecedents of subjective well-being. Third, this paper provides novel empirical evidence to further understand the relationship between digital technology and residents’ well-being. On the grounds of relative deprivation theory, traditional economic theory, and Maslow’s demand theory, it analyzes the important transmission mechanism of digital literacy influencing residents’ subjective well-being from income generating, consumption upgrading, and social belonging effects. Fourth, by studying the disparities of digital literacy among different groups, our study is beneficial for providing a reference for decision-making for formulating precise policies to improve the subjective well-being of rural residents. We find that the enhancement effect of digital literacy on residents’ subjective well-being is more prominent in “vulnerable groups”, which provides solutions for improving social welfare and bridging the “digital gap”.

Figure 1 shows this study’s background and theoretical framework.

The structure of this paper is as follows.

Section 2 introduces the theoretical and research hypothesis.

Section 3 describes the research design.

Section 4 presents the results of the empirical analysis.

Section 5 provides the research conclusions and policy implications.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

The term “digital literacy” originally referred to the comprehensive ability to acquire, comprehend, and utilize information on the Internet [

36]. Subsequently, scholars defined digital literacy as the integration of essential skills necessary for individuals to thrive in the evolving digital landscape, encompassing their capacity to effectively access and employ relevant information on online platforms [

37]. This concept comprises two dimensions, the strategic aptitude to obtain valuable information and the cognitive ability to assimilate acquired knowledge [

38], to achieve valuable outcomes such as education, employment, and social participation. Amartya Sen’s competency approach emphasizes that well-being depends not only on material possessions but also on capabilities that an individual can achieve. New technologies and tools in the field of information and communication have enhanced people’s subjective welfare levels [

35,

39]. The utilization of digital technology yields a network effect, expanding the scope of social connections and bolstering residents’ confidence in the future [

40]. Additionally, it empowers individuals to enhance their efficiency in information retrieval and ability to acquire knowledge [

41], thereby bolstering their capacity to exert control over their lives and fostering subjective well-being [

32,

42]. Currently, the integration of digital technology into individuals’ lives has led to higher levels of subjective well-being among residents who possess Internet-connected phones, computers, and other related devices [

43,

44]. Hence, we propose Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1: Elevating the digital literacy of rural residents will enhance their subjective well-being, that is, the digital literacy of rural residents has a “dividend” effect on the subjective well-being of residents.

Level of income plays a crucial role in determining residents’ life satisfaction [

45,

46]. By reducing the relative income gap, rural families can experience a decrease in the sense of relative deprivation, leading to an elevation in their overall quality of life [

47]. Digital literacy helps to advance people’s consumption experience, facilitating the transformation of consumption structure [

48]. Simultaneously, with the emergence of online social network platforms, the Internet offers opportunities to maintain existing relationships while establishing new social connections [

49], thereby complementing the current social relationships.

Rural residents’ digital literacy influences their SWB by increasing income. According to the theory of relative deprivation, individuals may experience feelings of deprivation due to a lack of resources, which can result in a perceived disadvantage compared to others. This sense of deprivation poses challenges for individuals in maintaining their happiness within the social hierarchy to which they belong [

50]. In contrast to urban areas, rural areas exhibit inherent vulnerabilities such as limited access to resources, an imperfect market structure, and a lower level of economic development. Disparities in human capital and income contribute to a sense of relative deprivation among rural communities, leading to a decline in subjective well-being. Digital technology has the potential to overcome barriers in disseminating market information [

35], facilitate the circulation of commodities between urban and rural areas, enhance the market impact of agricultural products, and expand the reach of rural markets [

51]. This is particularly beneficial for digitally literate rural residents who can leverage digital technology to increase their incomes. Moreover, digital platforms enable rural residents to access valuable resources, such as network knowledge, employment opportunities, and entrepreneurship prospects [

52], enabling them to transition from agricultural occupations to non-agricultural ones [

53]. In essence, digital literacy acts as a form of human capital that provides latecomer advantages for disadvantaged groups by narrowing the relative income gap and enhancing life satisfaction [

54].

Rural residents’ digital literacy also influences SWB by upgrading consumption. Traditional economic theory posits that utility is derived from consumption, with the level and structure of consumption reflecting individual resource status and the implementation of economic and social rights [

55]. Changes in consumption patterns significantly impact rural residents’ satisfaction levels [

56]. Digital technology provides convenient online shopping platforms, diverse product choices, personalized services, and efficient logistics distribution systems. This facilitates the emergence of new consumption patterns and promotes the upgrading of residents’ consumption habits [

35]. Simultaneously, big data analysis accurately identifies user needs, prompting businesses to continuously enhance product quality and service levels. This further caters to residents’ growing demand for personalized consumption while driving continuous optimization in the consumer market [

48]. Digital literacy, through consumption upgrading, has a dual impact on residents’ subjective well-being: it enables an upgrade in residents’ consumption structure [

57] while enhancing consumers’ subjective well-being through enriched materialistic, spiritual, and cultural experiences [

34].

Furthermore, rural residents’ digital literacy influences their SWB by enhancing their sense of social belonging. Frequent social activity is commonly believed to be associated with higher levels of happiness [

1]. The increasing popularity of communication technology and the Internet has facilitated the emergence of social platforms that have effectively eliminated temporal and spatial boundaries, enabling the elderly, disabled, and other marginalized groups to integrate into society, reducing social isolation and thereby enhancing human communication and social interaction [

58], redounding understanding and respect, and promoting social harmony. Digital technology provides a platform for residents to participate in social and political issues, enhancing individuals’ sense of belonging and social responsibility. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory suggests that after fulfilling physiological and security needs, people experience an intensified desire for interpersonal communication. Engaging in communication on social networks facilitates obtaining greater recognition and support from others [

59], reducing feelings of loneliness among residents and improving life satisfaction levels [

60]. Based on the aforementioned analysis, we propose Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2: Rural residents’ digital literacy level influences subjective well-being through increasing income, upgrading consumption, and social belonging.

The integration of digital technology into various rural areas encompasses production, livelihood, ecology, and governance. While the application of digital technology has provided diverse opportunities for rural residents to benefit, there is an unequal distribution of these benefits in economic activities [

61]. From a behaviorist perspective, individual differences in psychology or cognitive structure result in varying quality and mentality systems that influence the extent to which individuals integrate into the digital age. The digital divide theory places rural vulnerable groups in the context of digital literacy barriers, emphasizing differences in access to digital technologies, skills, and opportunities, which lead to differences in participation in and benefit from the digital economy, thus affecting the inequality of individuals’ digital dividends and happiness. Consequently, significant variations exist in SWB among different groups. At a societal level, regional factors, individual preferences, and cultural disparities also impact residents’ subjective well-being [

39,

62]. The difference in digital literacy among different characteristics of rural residents results in heterogeneity in improving subjective well-being. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3: The impact of digital literacy on the subjective well-being of rural residents varies across natural and social attributes. In other words, there exist differences in digital literacy on the subjective well-being of rural residents.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Research Conclusions

According to the availability and timeliness of data, we select the CFPS data from 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020 to investigate the impact of digital literacy on subjective well-being among rural residents in China. The findings suggest that enhancing digital literacy among rural residents can significantly improve subjective well-being as well as their sense of gain and security. The main conclusions resulting from this study are summarized as follows.

First, by controlling for a series of variables, we construct a fixed-effect regression model and reveal that an increase of 1% in rural residents’ digital literacy leads to a significant positive effect on their subjective well-being, with an increment of 0.048% at a statistically significant level. This finding highlights the remarkable “dividend effect” of rural residents’ digital literacy on their subjective well-being. The conclusion validates the findings of the existing literature. For instance, digital technology enhances individuals’ efficiency in gathering information resources, thereby facilitating optimal decision-making and improving their well-being [

74]. The “network gain effect” further amplifies the positive impact of Internet usage on residents’ well-being levels [

32], while some scholars have pointed out that excessive use of digital networks reduces humans’ interest in participating in social activities, increases their loneliness, and exacerbates the digital divide [

75].

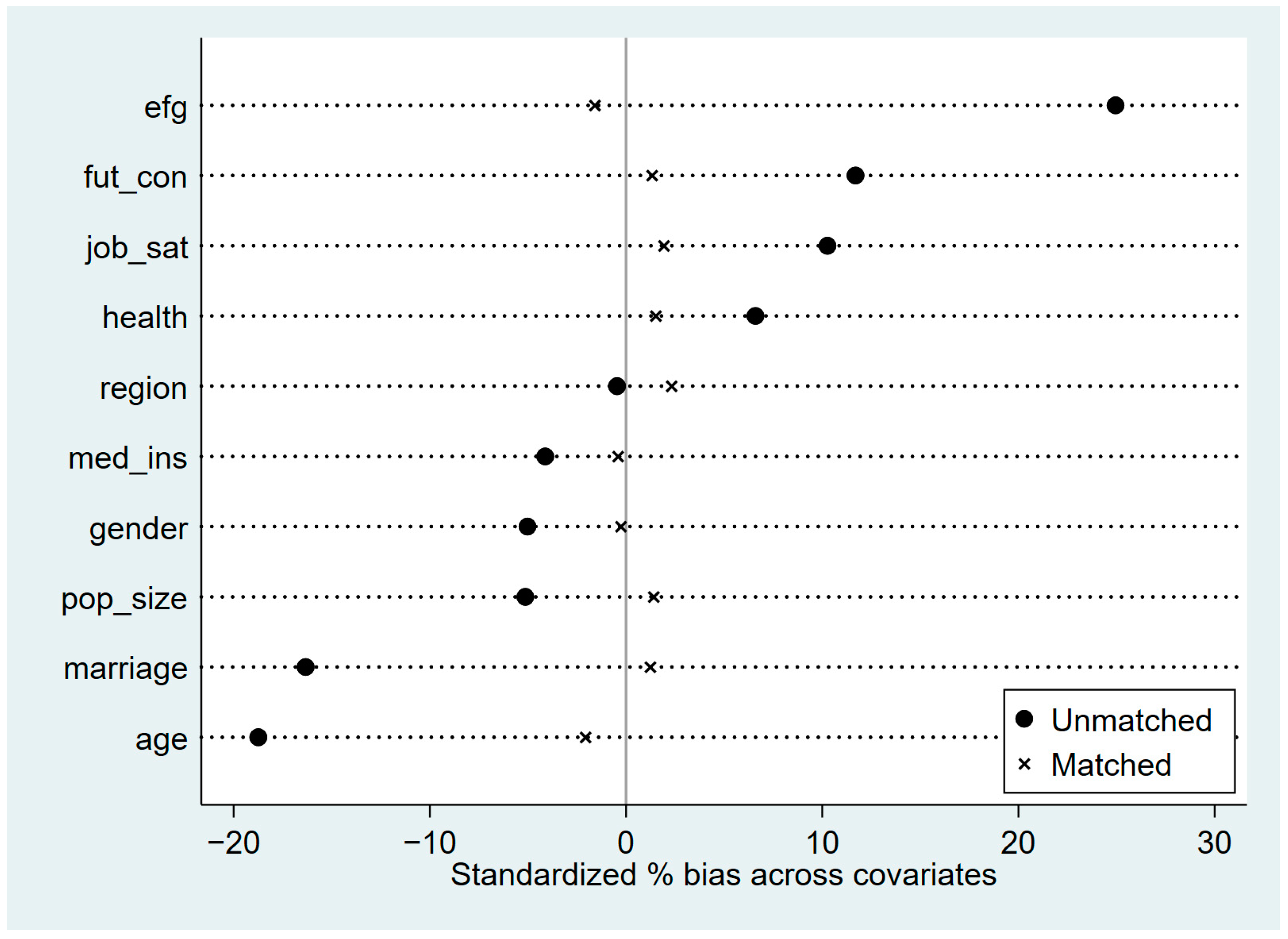

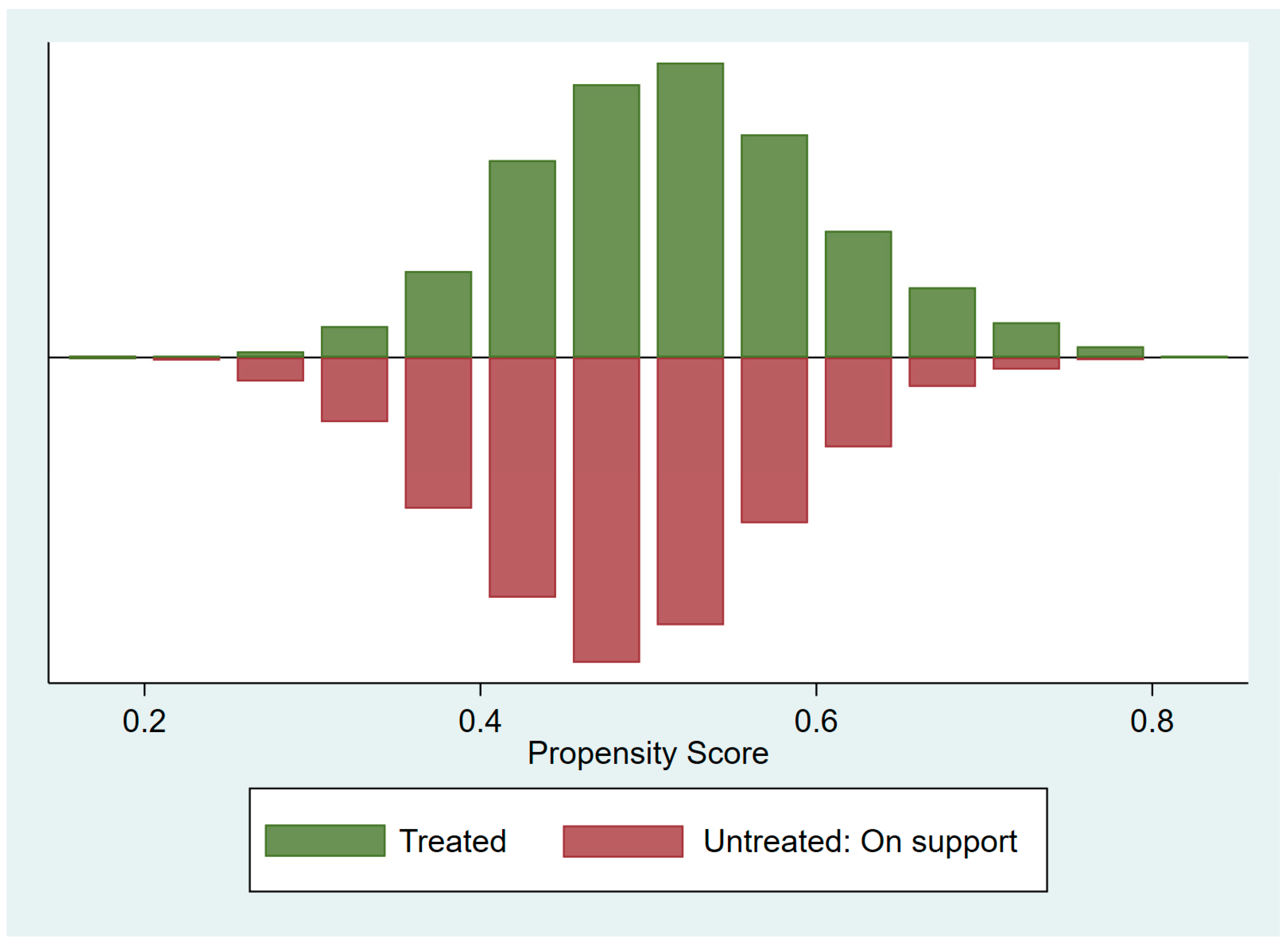

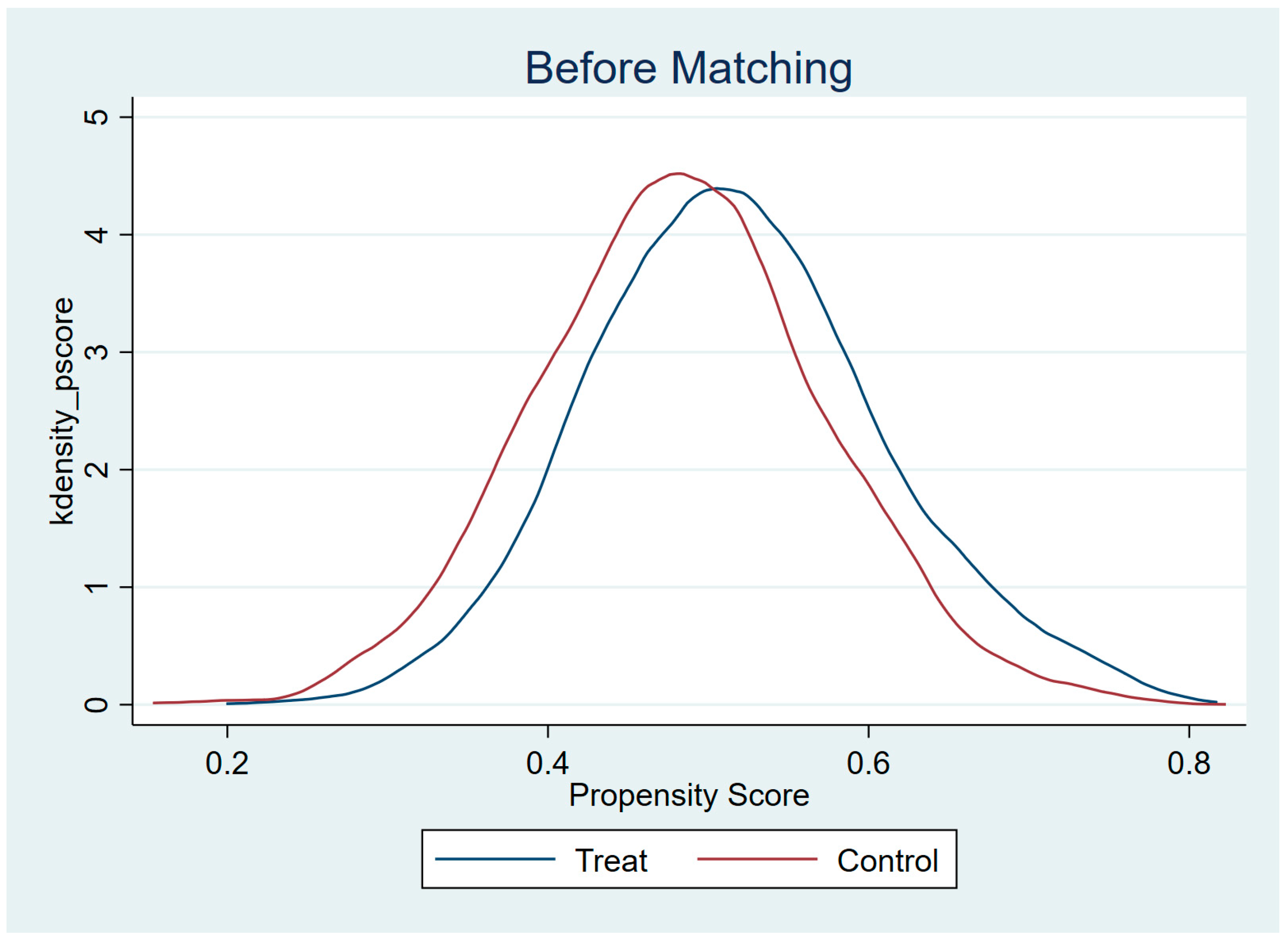

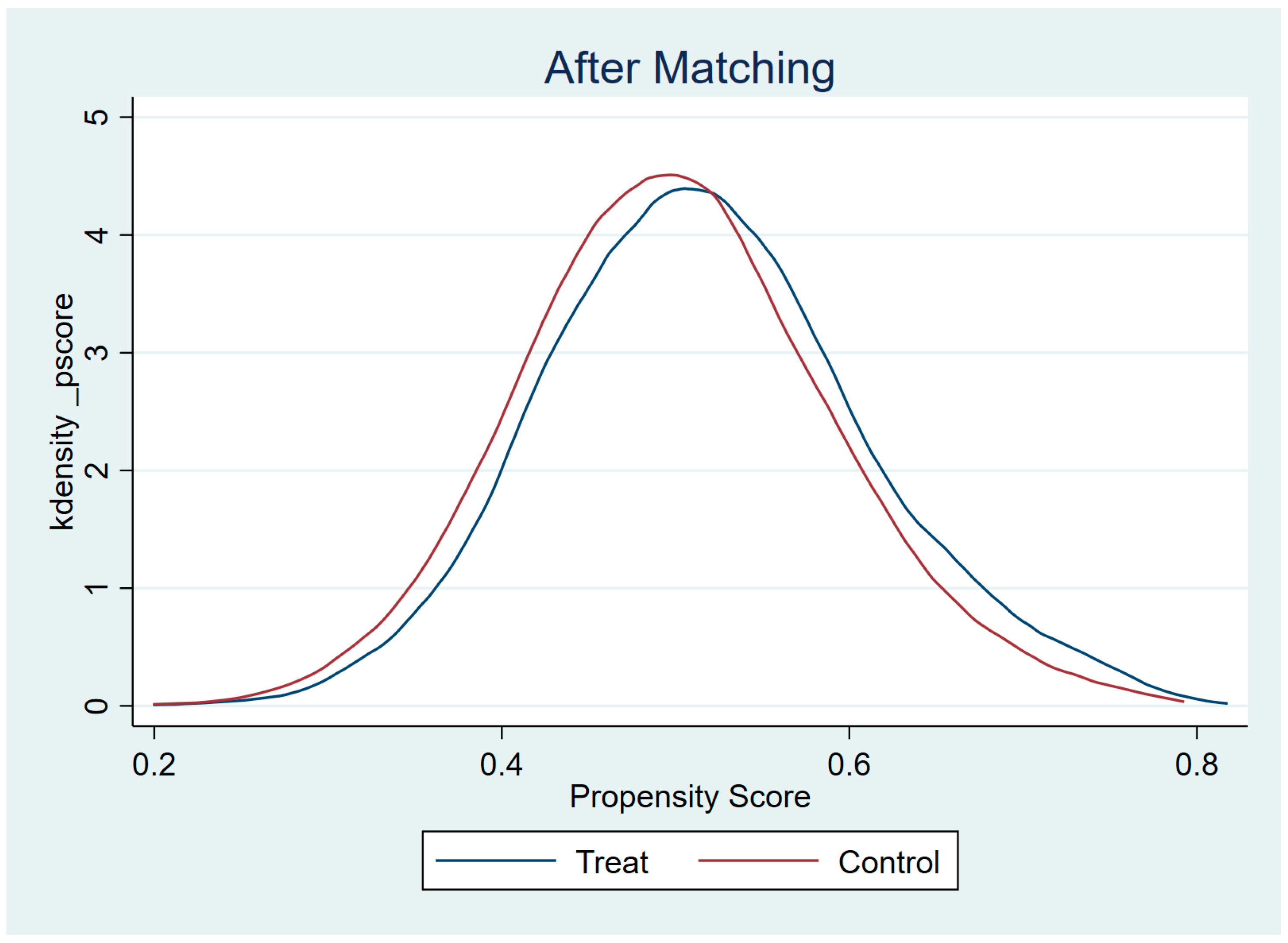

Second, in order to accurately assess the influence of digital literacy on the subjective well-being of rural residents, a series of rigorous robustness tests were conducted. These tests included the examination of endogeneity, replacement of regression models, adjustment of the explanatory variable calculation method, and randomly taking 60% of the samples. As a result, it was confirmed that digital literacy has a significant positive impact on subjective well-being.

Third, given the theory of individual differences, the impact of digital literacy on subjective well-being among rural residents varies across different groups based on people’s natural and social attributes. Specifically, this impact is more pronounced in the central and western regions, male individuals, younger age groups, those with lower education, and those with stronger social networks. These findings highlight significant differences in digital literacy on the subjective well-being of rural residents.

Fourth, we incorporate per capita income, the proportion of cultural consumption in total consumption, and a relationship evaluation as intermediary variables to examine the mechanism through which digital literacy influences rural residents’ subjective well-being. The findings reveal that digital literacy significantly enhances subjective well-being among rural residents by increasing income, upgrading consumption structures, and elevating social belonging. This research elucidates the pathways through which digital literacy impacts subjective well-being.

5.2. Policy Implications

Combined with the above conclusions, we draw the following policy implications. The foremost priority is to expedite the advancement of digital infrastructure. The government is expected to take a leading role in the development of digital infrastructure; enhance financial and policy support; jointly launch a digital subsidy policy to subsidize disadvantaged groups, especially for the western rural network base station, communication cable, and other facility investments; explore investment models for market players; and guide social capital participation in the construction. Furthermore, it is imperative for the government to facilitate the establishment of comprehensive radio and television networks in underserved regions, guide digital enterprises in developed eastern regions to establish cooperative relations with rural areas in western regions, optimize policies supporting talent development, and enhance the popularizing rate and quality of digital technology, thereby ensuring that digital dividends and well-being are truly accessible to all individuals.

Secondly, it is recommended to provide digital skill education and training for rural residents. In response to the specific needs of vulnerable groups, enterprises and social organizations are encouraged to actively participate in digital skill training programs targeting rural residents. Professional teachers should be organized to conduct digital education initiatives in rural areas according to the cognitive characteristics and learning ability of rural residents of different ages and genders and establish a multi-level complementary system for digital training. This will help foster a digital Internet mindset among rural residents and enhance the digital skills and literacy of vulnerable groups. For example, advanced skill training for rural inhabitants, such as digital marketing and e-commerce operations, encourages groups of young people to pair up with their elders in digital skills and conduct “one-to-one” tutoring. China’s “Information access to villages and households” project, Kenya’s “M-PESA” mobile payment project, India’s “Digital India” program, and other digital literacy cases provide effective reference.

Lastly, proper guidance should be provided to residents on utilizing digital technology effectively, which can contribute to income growth, consumption upgrading, and strengthening social connections. This should fully harness the potential of digital technology to actively contribute to information collection and dissemination, the accumulation of social capital, the optimization of consumption structure, flexible employment opportunities, and other aspects. As a result, this should enrich the content available on Internet platforms and systematically advance development models such as “Internet + entrepreneurship”, “Internet + e-commerce”, and “Internet + tourism”, among others, thereby deepening industrial integration. Broadening channels that increase rural residents’ income and employment prospects, enhancing their consumption experiences, and strengthening weak ties within communities can further unleash the “multiplier effect” of the Internet for vulnerable groups in rural areas and improve overall digital well-being.

It should be admitted that there are certain limitations in our study, and future studies could continue to make in-depth analyses from the following aspects. First, in the database, our use of respondents may overestimate or underestimate their digital skills due to some factors, and therefore, future research could consider incorporating objective assessments of digital literacy to supplement self-reported data and reduce potential bias. Next, as a result of the timeliness of the database, future research can focus on the potential impact of digital shifts in the post-pandemic period, which may have amplified the importance of digital literacy. We need to dialectically view digital literacy’s impact. Under the dual influence of objective factors, like the digital divide, literacy barriers, and regional policy constraints, as well as subjective factors, such as digital addiction, misinformation, and privacy issues, individuals may excessively use digital tools, resulting in Internet addiction, exacerbating inequalities for those with limited digital access and skills.