Abstract

This study utilized quantitative methodology in a national online survey to investigate the US public’s beliefs and attitudes regarding human–animal conflicts during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a view to understanding their willingness to consider animals’ interests during a disease outbreak. Our results suggest that the norms regarding prioritizing animal welfare are closely linked to respondents’ sense of relationship with animals and that the development of plans and processes for animal disease management, an essential component of public health preparedness systems, should be informed by the value commitments and ethical motivations of a diverse range of the US public.

1. Introduction

The effectiveness of animal disaster management (ADM), as part of public health preparedness, has been thrust into the spotlight in the wake of recent emergencies involving zoonoses like COVID-19 and Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI). The weight given to non-human animal (animals, hereafter) issues like their welfare is not always clear, however, since human concerns tend to take precedence. What different publics want or need to know regarding what happens to animals (for example, in animal agriculture) during an emergency is an understudied area of public health preparedness. Still unknown is how the public considers and weighs interspecies conflicts during a zoonotic outbreak, the subject of this study. For example, when do they think it is justified to reduce animals’ welfare (e.g., limiting the performance of natural behaviors)? If a vaccine exists for livestock or poultry (or companion animals for that matter) against an emerging disease, would the public support mass animal vaccination instead of killing animals? Will the public support depopulating livestock or poultry as an acceptable disease control tool to prevent infections in humans and other animals? Will the public support mandated closure of livestock operations to ensure proper slaughter and processing capacity if it will minimize negative animal welfare outcomes? The US population is diverse, and thus, responses to these questions will likely vary by socio-demographic groups.

In order to strengthen ADM and pandemic preparedness systems in the wake of a disease outbreak, it is important that incident command teams have accurate guidance on how the public considers human–animal moral dilemmas and which strategies involving animal welfare the US’ diverse publics will likely support. Getting it wrong will cost lives and lead to unnecessary suffering. However, many recent studies documenting the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have focused primarily on human-centric concerns, and there is but modest attention to public attitudes and beliefs involving the welfare of animals, especially concerning how they view interspecies conflicts of duties or interests that involve animal welfare and the US food system [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

When making public health recommendations, the abovementioned studies tend to focus on advancing human interests. Recommendations for improvement tend to perpetuate siloed thinking, failing to attend to both links between human and veterinary–animal health and welfare and to public health and agriculture as connected wholes [18,19]. ADM and public health preparedness systems have both an essentiality and an integrative capacity in how the public interacts with food systems. It is left to be seen how exactly the newly revitalized National One Health Framework to Address Zoonotic Diseases and Advance Public Health Preparedness (NOF-Zoonoses) in the United States will incorporate public attitudes regarding ethical dilemmas involving animals.

The COVID-19 pandemic upended human lives, and it continues to impact our welfare on a global level [20]. However, forced movement restrictions to protect public health and slow virus spread led to collateral impacts on the welfare of animals too. Thus, co-human–animal vulnerability to transboundary diseases should be a matter of urgency. The timing for considering animal welfare issues as part of ADM could not be more critical. The US is in the throes of experiencing an uptick of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (H5N1 Bird Flu) cases among people, especially (for now it seems) those working in the agricultural sector [21,22].

The gap regarding understanding public attitudes towards animal issues during a zoonosis or pandemic can be plugged by revealing and analyzing the normative considerations motivating and the decision-making apparatus guiding public health cum agricultural policies in the US [23]. In particular, understanding the ethical beliefs and attitudes of citizen-consumers regarding animals in a novel public health crisis, including influences on their behavior and consumption habits, can be particularly instructive in producing effective public policies to protect cross-species vulnerable populations in future public health emergencies. To attain a higher level of optimal health and to sustain healthy communities, good animal welfare outcomes should also be supported as part of an overall culture of care in ADM.

During the pandemic, some animal owners of companion animals relinquished or abandoned them [24,25,26], induced by the fear of contracting the virus from their dogs or cats. While an adoption surge did not happen uniformly in the US in 2020 [27], the pandemic disrupted certain types of veterinary care that companion animals would have otherwise received. Companion animal owners may have avoided non-essential veterinary care, lapsed on their cats and dogs’ routine treatments, delayed euthanasia, or postponed preventative care or treatment for chronic conditions [28]. The reasons for these postponements or alternations are multifactorial. They include disruptions within the veterinary profession itself [29,30,31,32], adherence to social distancing measures, and owners’ diminished financial capacity to afford veterinary care for their animals [33].

The pandemic also tested the resilience of the US food system, revealing the close social, economic, and political complexities and linkages between human and animal welfare [34] and exposing the fragility of the global food supply chains [35].

The extent of the challenges endured by the livestock sector from COVID-19 is coming into focus. Farmers and ranchers, agricultural workers, and food processors (producers, hereafter) were among the frontline workers who did their best to keep the US population food secure during the pandemic. In addition to struggling to mitigate financial shocks, they had to manage their operations while protecting their own lives and that of their animals. The pandemic saw producers and veterinary team members struggling with psychological and moral distress [36,37,38,39].

Conventional animal agriculture is governed by demand, efficiency, and speed of agricultural processes. The margin to meet both biological needs of farm animals and agricultural production and marketing imperatives is narrow. The time-to-market (i.e., taking finished animals to market at an optimal date) and ‘hold-and-hope’ economic decisions dictate when farmers complete their activities, including harvesting their animals [40,41]. The early stages of the pandemic challenged the capacity of farmers and the production sector to provide animal care. Uncertainty, fast-changing and fluid situations regarding virus spread, and disruptions to supply and processing chains meant an unknown and precarious harvest timetable for producers [42]. Decline in demand for fresh meat and animal products, coupled with stock accumulation and temporary closures of abattoirs and meatpacking facilities due to COVID-19 infections among workers, led producers and the agricultural production sector to employ countermeasures to respond to these exigent circumstances [43,44].

Some of the countermeasures that producers took to minimize logjams included slowing animal growth, since slaughterhouses were operating at reduced capacity or had closed their doors due to pandemic-induced labor issues. Where possible, producers altered typical ‘programmed feeding’ systems, thus limiting their animals’ access to feed and water to slow down market readiness and mitigate a backlog of slaughter animals [45,46]. Animal stock and perishable food products that producers could not sell had to be destroyed. In the dairy sector, farmers dumped thousands of gallons of milk due to a precipitous drop in demand from restaurants, hotels, schools, and other food service sector customers. Cows still had to be milked, however, multiple times a day, despite the slump in demand. More than 20 slaughterhouses shuttered their doors. Without sufficient slaughterhouse space to process fast-growing pigs and chickens, producers were forced to terminate their animals. Over two million animals were depopulated in the initial months of the pandemic [47].

The countermeasures to overcome these developments and logistical obstacles and to maintain the flow of animals are underscored by value judgments and ethical considerations in tandem with assessments of risk involving economic losses. These countermeasures are replete with implicit and explicit ethical judgments on how to avert a greater disaster from happening, e.g., kill some to save others. Decisions to slow animal growth resulted in substantial burdens to animals in the form of negative animal welfare [48]. Further, some farmers resorted to welfare slaughter, killing healthy animals due to overcrowding or other sub-optimal animal husbandry conditions on farms due to human factors and not from a disease outbreak per se [49]. During COVID-19, welfare slaughter due to logistical challenges, inoperable processing plants, lack of demand, or avoidance of unprofitable prices of animal sales raised different ethical concerns of depopulating animals to ‘stamp out’ disease spread within the flock or herd. These decisions are subject to reflection and analysis on ethical grounds and invite further study to understand the connections between concerns about animal welfare, food security, and public health raised by the pandemic [50,51].

The objective of this study was to understand what lessons are worth carrying forward from COVID-19, which might help us be better prepared and more resilient in the face of a future viral outbreak. We collected responses from US citizen-consumers regarding their beliefs about animal issues and demographics that can inform socio-ethical attitudes regarding human–animal interactions and conflicts during the COVID-19 disease pandemic. To strengthen emergency prevention, preparedness, and planning, especially with a view towards animal agriculture, we were motivated to (1) capture public sentiment towards animals and their welfare in disaster management [52,53] and (2) ascertain how questions and answers about interspecific issues should be effectively and accurately communicated to the public by disaster management professionals to minimize death, injury, disability, and suffering [54,55]. Highlighting the inherently or conditionally normative issues [56] and understanding how beliefs, values, and norms of the US public influence trade-off decision-making during a crisis can advance reliable policies and practices, timely information sharing, and the development of targeted and consistent messaging to enhance future public health preparedness and animal disease management strategies.

This study echoes calls that have been steadily growing in volume and frequency to include animals and their welfare in national disaster management plans [57]. Our results are relevant to ongoing processes to strengthen the National Biodefense Strategy [58] and American Pandemic Preparedness Plan (APPP) [59] and advance the federally coordinated One Health framework to protect animal and public health via the proposed Advancing Emergency Preparedness Through One Health Act 2021, underscored by the seven goals of the NOF-Zoonoses framework [60].

2. Methods and Data Analysis

This survey was part of a multi-method two-phase study, the Wellanimal project (NIFA Project # ALKW-2020-07183) [61], which combined qualitative and quantitative methods. The central goal of the Wellanimal project is strengthening the US food system so that it is better able to protect animals who are at risk for morbidity and mortality during a disease outbreak. Part of this effort involves helping animal health disaster managers, farmers, supply chain actors, and the public prepare for future novel pandemics and zoonoses by transcending the anthropocentric gaze. This includes the development of public health policies and practices that aim at effective communication strategies to bolster public consideration towards animal issues during an outbreak.

For this second phase, survey tools were developed based on the findings of the qualitative research conducted in the first phase of this study (spring–fall 2022) [62]. Approval was obtained from the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) (#1693407-3) to conduct this national study. The sample size was calculated for a 95% confidence interval and a 2.5% of margin of error, which resulted in a minimum of 1537 respondents. The sample was divided by demographic characteristics, including gender, region, income, age, and education level. The survey was administered in December 2023 through Qualtrics, and we were able to run 331 more questionnaires, leading to a final sample size of 1868. Respondents received incentives according to the terms provided by Qualtrics. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and respondents could leave the survey at any time or skip questions that they found uncomfortable.

Before data collection, input was gathered from phase-1 panelists, i.e., disciplinary experts from veterinary medicine, public health, and bioethics, to ensure that the questions and statement structure were clear and relevant to this research. Panel members were asked to provide feedback on (a) each statement’s correspondence with the research goals and objective, (b) appropriateness of phrasing of the questions and options, (c) sequencing of the statements and options, and (d) survey length and readability.

The sample description can be reviewed in Table 1. There, we present all frequencies of all variables that were deployed in this study. The characteristic ‘female’ corresponds to almost 70% of all responses. For age, the 65+ group represents around 28% of all responses. Respondents who identified as being from the ‘south’ represented 39.5% of all respondents. Under education, the three categories, high school, having some college degree, and holding a bachelor’s degree, were more than 20% of all respondents. Almost 85% of all respondents earned less than USD 100,000. A total of 62.7% of the respondents answered that they are animal owners. Almost 80% of the respondents indicated that they consumed products of animal origin ‘usually or always.’ 66.8% of the respondents were white or Caucasian, and Democrats represented 38.7% of all respondents, with those self-identifying as Republicans coming in at 32.4%.

Table 1.

Proportion of variable description.

We developed 8 statements with a five-point scale, ranging from totally disagree to totally agree, to gather information about the beliefs and attitudes regarding both human–animal interactions and conflicts during the COVID-19 disease pandemic. The statements were as follows:

- Statement 1 (S1): Protecting human life should come before protecting animal life.

- Statement 2 (S2): Using animals to develop vaccines against a new virus like COVID-19 is acceptable.

- Statement 3 (S3): If a vaccine exists for pets/companion animals against an emerging disease, then these animals should receive it instead of being killed.

- Statement 4 (S4): Culling (killing) livestock or poultry is an acceptable disease control tool.

- Statement 5 (S5): If a vaccine exists for livestock or poultry animals against an emerging disease, then these animals should be vaccinated instead of being killed.

- Statement 6 (S6): In general, animals should be permitted to perform their natural behaviors (e.g., going outside, socializing with people and other animals).

- Statement 7 (S7): Animals should be permitted to perform their natural behaviors (e.g., going outside, socializing with people and other animals) during lockdown.

- Statement 8 (S8): During a pandemic like COVID-19, reducing animals’ welfare is justified if it will achieve an important human goal.

Two different analyses were performed, namely, descriptive and multi-logistic regression. For the descriptive analysis, we used only two categories of responses: a. Disagree (to encompass Strongly Disagree and Disagree) and b. Agree (to encompass Agree and Strongly Agree). The Neither Agree nor Disagree option was omitted in order to compare the difference of agreement.

According to Prickett et al. [63] and Taylor et al. [64], a multi-logistic regression model is an approach to analyze these data with scales, and for this reason, the model was deployed to verify possible differences in the proportions of the scale of agreement for each characteristic. In this situation, the variable ‘strongly disagree’ was set as a reference. We used logit transformation to estimate the parameters [65,66,67]. Agresti [68] defines this model as a cumulative link model. The entire analysis was performed using the software R 4.3.2 [69] Mass package.

3. Results

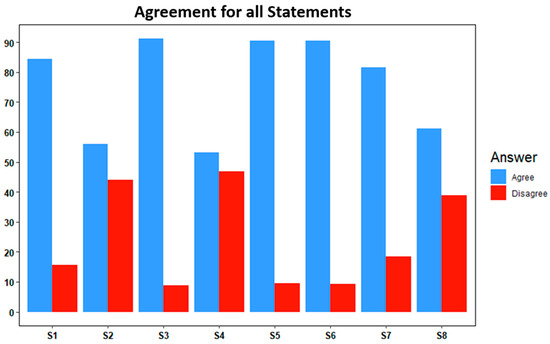

For the descriptive analysis, a graphic was used to help visualize the percentage of agreement for each statement. Here, we did not split the categories. Figure 1 represents the proportion of agreement for all statements. Here, for all statements, the agreement was more than 50%, and S2, S4, and S8 resulted in the highest disagreement rate, coming in at more than 40%. On the other hand, S1, S3, S5, S6, and S7 resulted in more than 80% agreement.

Figure 1.

General agreement percentage for each statement.

The proportion of agreement for all characteristics and all possible respondent answers is presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Percentage of agreement for statements 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Table 3.

Percentage of agreement for statements 5, 6, 7, and 8.

For gender, S2, S4, and S7 had the highest differences, i.e., 21%, 18%, and 14%, respectively. The highest age difference for all statements was 14%. For region, the highest difference observed was 8% for S2. Education showed a difference larger than 20% for S2 and S4. S3 and S6 had 100% agreement for some groups. For income, S2 and S8 resulted in more than a 20% agreement difference, and for USD 200,000 or more, there was 100% agreement with S3. In terms of animal ownership, the biggest difference was 12% and 15% for S2 and S8, respectively. For animal consumption frequencies, there was more than a 20% difference in agreement for S6. For race, the highest difference was 12% for S8, and for political affiliation, a 17% difference was recorded for S2.

After completing the descriptive analysis, a multi-logistic regression model was performed that utilized all five scales of agreement. For this model, we calculated the odds ratio (OR) and the 95% confidence intervals (95% C.I.) for each characteristic. Only significant results were used in our analysis, which employed a p-value of 0.05. For each characteristic, one group was used as a reference. This group was omitted in the presentation of the results for elegance. The reference group was ‘Female’ for gender, ‘18 to 24’ for age, ‘Midwest’ for region, ‘Middle School’ for education, ‘Less than USD $24,999’ for income, ‘No’ for animal ownership, ‘Not At All’ for animal consumption frequencies, ‘Black or African American’ for race, and ‘Republican’ for political affiliation, respectively. An OR that is bigger than 1 means that the group had more chances to have more agreement with the statement, and when it is smaller than 1, this means that the group had more chances to have more disagreement with the statement.

Table 4 represents the results for S1 and S2. For S1, age, region, income, animal ownership, animal consumption frequencies, and political affiliation were considered significant. For age, the OR increases as the respondents’ age increases. We interpreted this to mean that older respondents have more likelihood to agree more with the statement. Respondents who were 65 years and older were 79% more likely to have more agreement than people between 18 and 24. For region, respondents identified as Midwesterners were more likely to have more agreement than those living in the West, which was around 56%. Respondents who identified USD 200,000.00 or more as their income were 3.2 times more likely to have more agreement than respondents whose income was less than USD 24,000.00. People without animals were almost 50% more likely to have more agreement than animal owners. As animal consumption frequencies increase, the likelihood of agreement also increases. Respondents who always consume animal products were almost 2.5 times more likely to have more agreement than respondents who do not consume animal products at all. For political affiliation, Republicans and Democrats did not differ in their responses. However, they were 29% and 44% more likely, respectively, to have more agreement than respondents who identified as independent.

Table 4.

Odds ratio, confidence interval, and p-values for selected characteristics for S1 and S2.

For S2, age, education, animal ownership, and political affiliation were considered significant. Respondents between 45 and 64 years old presented an OR smaller than one. Respondents between 25 and 44 years old were 45% more likely to have more agreement than the group between 45 and 64 years old. Also, respondents 65 years or older were 33% more likely to have more agreement than respondents between 45 and 64 years old. Increasing the level of education increases the OR. A post-graduate is almost two times more likely to have more agreement than a middle schooler. People without animals were almost 40% more likely to have more agreement than animal owners. Republicans were not considered different from Democrats and independents in their responses. However, they were almost 40% and 70% more likely, respectively, to have more agreement than respondents who identified as independent.

Table 5 represents the results for S3 and S4. For S3, age, education, animal ownership, and political affiliation were considered significant. As the age of the respondents increases, the OR also increases. Respondents aged 65 or older were almost twice as likely to have more agreement than people between 18 and 24. Some respondents with a post-graduate degree were almost 1.5 times more likely to have agreement than respondents who had a middle school education. Animal owners were 56% more likely to have more agreement. With increases in the frequency of animal product consumption, the OR also increases. Respondents who always consume animal products were twice as likely to have more agreement than those who do not consume these products at all. For political affiliation, Democrats were 63% more likely to have more agreement than Republicans.

Table 5.

Odds ratio, confidence interval, and p-values for selected characteristics for S3 and S4.

For S4, gender, age, animal ownership, and political affiliation were considered significant. Male respondents were 89% more likely to have more agreement. As the age of respondents increases, the likelihood that these respondents would agree more decreases. Respondents between 18 and 24 were around 70% more likely to have more agreement than respondents between 55 and 64 and 65 or older. People without animals were 25% more likely to have more agreement than animal owners. Republicans were not considered different from Democrats and independents in their responses. However, Democrats were around 42% more likely to have more agreement than independents.

Table 6 represents the results for S5 and S6. For statement 5, age, animal consumption frequencies, race, and political affiliation were considered significant. When the respondents’ age increases, the OR also increases. Respondents 65 or older were 71% more likely to have more agreement than respondents between 18 and 24. As the frequencies of animal consumption increase, the OR increases. Respondents who always consume were around 1.7 times more likely to have more agreement than those who do not consume animal products at all. White Americans and others show more likelihood to have more agreement than Black or African Americans, with 87% and 62% more likelihood, respectively. Democrats were 91% more likely to have more agreement than Republicans.

Table 6.

Odds ratio, confidence interval, and p-values for selected characteristics for S5 and S6.

For statement 6, education, animal ownership, and animal consumption frequencies were considered significant. The higher the respondents’ level of education, the more likely they would have more agreement. Some respondents with post-graduate schooling were 2.6 times more likely to have more agreement than those with only a middle school background. Animal owners were 49% more likely to have more agreement. With increases in the frequency of animal product consumption, the OR also increases; respondents who usually or always consume animal products were almost 1.5 and 2.8 times more likely to have more agreement, respectively.

Table 7 represents the results for S7 and S8. For statement 7, income, animal ownership, and animal consumption frequencies were considered significant. As the income of the respondents increases, the OR also increases. Respondents who earned USD 200,000 or more were almost two times more likely to have more agreement than respondents earning less than USD 24,000. Animal owners were 36% more likely to have more agreement. Respondents who always consume animal products were almost 75% more likely to have more agreement than respondents who consume animal products sometimes.

Table 7.

Odds ratio, confidence interval, and p-values for selected characteristics for S7 and S8.

For statement 8, gender, age, income, animal ownership, and political affiliation were considered significant. Male respondents were 68% more likely to have more agreement. As the age of respondents increases, the likelihood that these respondents would agree more decreases. Respondents between 18 and 24 were 56%, 63%, and 85% more likely to have more agreement than respondents between 45 and 54, 55 and 64, and 65 or more, respectively. As income increases, the likelihood to have more agreement increases; respondents whose income was USD 200,000 or more were 2.5 times more likely to have more agreement than respondents whose income was less than USD 24,000. People without animals were 42% more likely to have more agreement than animal owners. Republicans were not considered different from Democrats and independents in their response. However, Republicans and Democrats were almost 40% and 46% more likely, respectively, to have more agreement than respondents who identified as independent.

4. Limitations

In this study, participants were asked to recall their experiences during the pandemic, which is subject to the vagaries of memory. Some respondents may have believed or behaved differently during the pandemic than what their responses in this survey indicate. Responder bias is not an uncommon feature of population-based studies. Here, the willingness to participate in the survey may be positively correlated with a strong desire to ensure better animal welfare outcomes in future disease outbreaks. This study also affords an updated description of public attitudes towards animals during a crisis based on typical demographic information.

From the statistical point of view, we initially planned to utilize logistic regression to compare only the ‘disagree’ and ‘agree’ responses. However, this model could not be used for all statements because for some groups, we encountered a 100% agreement, leading to a lack of consistency in the results.

5. Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate the willingness of the US public to consider the interests of animals alongside human ones during a disease outbreak. We wanted to understand how a representative sample of the US public viewed interspecies conflicts of duties during a public health emergency in order to strengthen disaster preparedness systems in concert with animal systems, specifically animal agriculture.

Our study extends other public perceptions scholarship [70] and seeks to improve public service resilience [71] by looking at how the US public considers and weighs human–animal conflicts. By understanding socio-demographic similarities and differences and the public’s ethical priorities and motivations, public health officials and agricultural sector agents can support farmers and others across the value chain to enhance food system resilience during an animal disease crisis.

Generally speaking, we found that there is more agreement than disagreement with all of the statements, independent of the level of the characteristics. However, we also identified a difference in the behavior of the statements, namely, the set of significant variables for each statement is not the same. For this reason, each statement is unique. However, when we took into account the frequencies of the occurrences of each of the characteristics, we were able to ascertain their global importance.

To identify which characteristics could be considered more important for the respondents, we created three groups according to their frequencies of occurrence. Their levels of importance are captured in Table 8. There, region and race appear only once and thus are of low importance. Gender, education, and income appear between two and three times and are of moderate importance. Animal consumption frequencies, age, animal ownership, and political affiliation appear five or more times and are of high importance. They will be the focus of this discussion.

Table 8.

Importance levels of each characteristic.

Animal consumption frequencies occurred five out of eight times. For all statements, the likelihood of more agreement corresponded with increasing frequency of consumption of animal products. When communicating with people who always consume animal products versus a vegan/vegetarian, public health/animal disease management messaging should be specific to their ethical commitments. This reflects the common wisdom.

Age occurred six out of eight times. For all statements, the oldest respondents differed from the youngest respondents. In four of the six times, the likelihood for more agreement corresponded with increasing age. However, on two occasions, the likelihood of more agreement decreased as the age of the respondents increased. That is, younger people and older people think differently in regard to these statements but not always in the same direction. In four situations, older people had more agreement, and in two situations, younger people had more agreement.

Political affiliation occurred six out of eight times. Republicans and Democrats were more similar in their attitudes towards animal welfare considerations in a novel pandemic. Out of the six times, only once did Democrats and Republicans differ in their responses. However, in the other five times that a difference was found, independents always responded differently than both Republicans and Democrats. The upshot is that against conventional wisdom, messaging involving animal welfare in a pandemic may be similar for Democrats and Republicans. However, the communication strategy will likely have to be different for independents.

Animal ownership occurred seven out of eight times. In three of the seven times, respondents who owned animals were likely to indicate more agreement than those who did not. Respondents demonstrated more concern for animal welfare because they showed more agreement with S3 (if a vaccine exists for pets/companion animals against an emerging disease, then these animals should receive it instead of being killed), S6 (in general, animals should be permitted to perform their natural behaviors), and S7 (animals should be permitted to perform their natural behaviors during lockdown) and showed more disagreement with S1 (protecting human life should come before protecting animal life), S2 (using animals to develop vaccines against a new virus like COVID- 19 is acceptable), S4 (culling (killing) livestock or poultry is an acceptable disease control tool), and S8 (during a pandemic like COVID-19, reducing animals’ welfare is justified if it will achieve an important human goal).

Once someone is in a relationship with an animal, the person tends to be more caring or empathetic towards the animal. This also reflects the commonsense view of human–animal relationships.

The COVID-19 pandemic underscores the need for stronger ethical analysis of ADM to better prepare the public and animal owners and caretakers ahead of an emergency so that conflicts (moral and otherwise) between human and animal interests are minimized and miscommunication around expectations during a crisis is reduced. Here, bioethicists specializing in public health, animal, veterinary, agricultural, and environmental ethics can serve as a vital conduit for helping the public and public health officials, including animal disease management team members, navigate the ethical challenges, including conflicts of duties that they may encounter [36,72], and difficult discussions around the management of animal systems, including animal agriculture [73]. Bioethicists can help to reveal a comprehensive spectrum of morally relevant variables that determine the feasibility of solutions to moral dilemmas impacting human–animal relationships, including strains and motivations on responsibilities and implicit species-centric biases.

Our research investigating perceptions and attitudes toward human–animal conflicts during a disease outbreak can help to advance public health preparedness more generally and ADM more specifically by strengthening the ethical analysis process associated with them. By incorporating public sentiment (beliefs, values, and norms) as part of the ethical analysis for ADM, public health officials and those advocating for animal systems like animal agriculture have a basis for considering how specific features of different groups of the US public influence their ethical willingness to weigh or prioritize animal welfare concerns alongside human ones.

Ethical analysis involves problem framing and careful assessment of claims and inferences presented in an argument. It can illustrate both how to take value dimensions into account and systematize normative decision-making in a crisis. Also, ethical analysis can clarify which normative ideals are operative or realized through public health decisions regarding the following:

- Whether the aim of an animal disaster management policy or practice is well justified.

- Whether the goal is being responsibly pursued.

- Whether the outcomes to animals and people are acceptable.

Our research suggests that much-needed investigation of the ethical dimensions and epistemological challenges experienced by citizen-consumers is necessary in order to more effectively incorporate concern for animal welfare or care in pandemic planning. In terms of policy and education implications, the US public is generally concerned about animal welfare. Gender, race/ethnicity, geographic area, and political affiliation do not seem to divide their attitudes towards animal welfare during a novel disease pandemic.

Responsibility towards animals during an emergency situation may depend on how the competing responsibilities and co-mingled vulnerabilities are perceived. Understanding public commitments can ensure that a crisis response is acceptable to a diversity of communities while laying bare potential conflicts of interest and biases and how to avoid them. Seeking public engagement and involving them to co-design preparedness plans with local support services can lead to more human and animal lives being saved [73,74] while also understanding how they perceive both the thresholds of urgency and seriousness in relation to their capacity and willingness to act [75]. Tailor-made messaging is central to ethically motivating some segments of the US public who may not already be incentivized to consider or prioritize the interests of animals during an emergency.

Trust between public health officials and the public is a fundamental ingredient to ensuring public adherence to emergency directives in a zoonotic outbreak [70,76]. However, this trust, especially in government science, officials, and institutions, was tested severely during the pandemic and continues to be in short supply [77,78]. Regaining and sustaining public trust in public health institutions and our leaders is important to combat the next pandemic [79,80]. For public health officials and those in the agricultural sector (including veterinary teams), maintaining trust is particularly important in the wake of ethically challenging decisions they must make, including vaccinating, euthanizing, or depopulating animals.

Public health and disease management officials and agricultural spokespersons will not only need to be proficient in the myriad factors influencing an ADM strategy or justification for a depopulation decision, choice of method in a particular situation, and impacts to animal welfare and public health. They must also learn about the different media and information-seeking patterns [81,82] of the different US publics and adjust their ‘strategic messaging’ in order to meet them where they are. Exploring barriers to communication and sources of misinformation regarding animal–human health and welfare during a public health crisis is necessary to strengthen preparedness systems. As our results also suggest, the manner of communication should be sensitive to age differences and the circumstances of human–animal relationships, particularly as described above. For public health preparedness officials seeking to facilitate multisectoral and transdisciplinary collaboration and advance future-oriented commitments and countermeasures, our results indicate areas where efforts to minimize communication distances between different parties could occur. Specifically, it will be important that pandemic preparedness policies (e.g., APPP and NOF-Zoonoses) and education materials highlight the following:

- How and when animals will be killed to control zoonotic diseases.

- How vaccines are made.

- The decision-making process, including trade-offs made, when vaccines are prophylactically deployed versus other methods to contain an outbreak, such as stamping it out through depopulation.

- Concrete steps taken to minimize negative impacts on animals.

6. Conclusions

This research underscores the need for targeted engagement and communication strategies both to enable public health officials and the agricultural sector to reduce negative outcomes of future disease outbreaks on animals and to engage the various US publics in protective measures that benefit mixed human–animal communities during pandemics to come.

There continues to be a need to strengthen public health preparedness systems to better protect animals and people in future zoonotic outbreaks, especially as they intersect with the food production sector. While providing a closer view of the US public’s concerns regarding human–animal conflicts during an emergency, our study highlights an important opportunity to prepare ADM and public health preparedness team members to navigate the ethical terrain presented by a novel zoonotic disease. While animal welfare is regarded as a significant element of public health emergency management, some of our respondents were willing to weigh and prioritize responsibilities to animal interests alongside human interests, even when it might mean sacrificing certain human interests (e.g., being in favor of vaccination to minimize killing large numbers of animals). While the majority of the US public are not expected to put animal welfare as their primary concern during a disease outbreak, protecting the welfare of animals in the event of a zoonotic outbreak can be seen as both a significant ethical concern in its own right and accruing benefits for larger human and animal populations.

This study, while a snapshot in time coming towards the end of the declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic, shows that public health communication strategies during an animal disease outbreak that overlap with food system disruption and general attitudes towards animal welfare should be sensitive to varying degrees of importance that different publics attach to social, ethical, economic, and political aspects of human–animal relationships. It also highlights the need to incorporate effective communication strategies into ADM and preparedness planning to understand how the public, including animal owners, relates to various aspects of an emergency, such as uncertainty, how risk or threats are perceived and assessed, and a lack of moral imagination, misplaced sense of responsibility, or opportunity to participate in constructive deliberation with others, respectively.

By being transparent and acting with public sensibilities in mind, public health officials will be in a better place to address contested decisions. By consulting and developing working relationships with diverse groups of the US public to ensure that representatives of these groups are included in ADM planning processes, public health officials and agricultural spokespersons are exercising proportionality [73], engaging directly with communities impacted by emergency policies and not simply treating them as passive recipients of information or directives. Collaborating with the different publics will be vital in demonstrating the significance of protecting animal health in enhancing community health. Public support will be central in strengthening community health and surveillance programs to protect animals, contain further intra- and interspecies disease spread, and minimize public harm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A. and P.H.R.C.; methodology, R.A. and P.H.R.C.; formal analysis, R.A. and P.H.R.C.; investigation, R.A. and P.H.R.C.; writing—original draft, R.A. and P.H.R.C.; writing—review and editing, R.A. and P.H.R.C.; project administration, R.A.; funding acquisition, R.A. Both authors are essential contributors to the conceptualization, formal analysis, writing, revision, review, and editing of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NIFA grant number ALKW-2020-07183.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Alaska Anchorage (#1693407-3, approved on 5 December 2023).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Whitehead, D.; Brad Kim, Y.H. The Impact of COVID 19 on the Meat Supply Chain in the USA: A Review. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2022, 42, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilmany, D.; Canales, S.; Low, S.A.; Boys, K. Local food supply chain dynamics and resilience during COVID-19. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhoff, P.; Meyer, S.; Binfield, J.; Gerlt, S. Early Estimates of the Impacts of COVID-19 on U.S. Agricultural Commodity Markets, Farm Income and Government Outlays. FAPRI-MU Report #02-20. 2020. Available online: https://www.agri-pulse.com/ext/resources/pdfs/FAPRI-Report-02-20.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Meier, M.; Pinto, E. COVID-19 Supply Chain Disruptions. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2024, 162, 104674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, C.N.; Dang, H. COVID-19 in America: Global supply chain reconsidered. World Econ. 2023, 46, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, N.M.; González-Bulnes, A.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Animal Welfare and Livestock Supply Chain Sustainability Under the COVID-19 Outbreak: An Overview. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 582528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, S.; Aday, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Qual. Saf. 2020, 4, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Addressing the Long-Term Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Families; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSalvo, K.; Hughes, B.; Bassett, M.; Benjamin, G.; Fraser, M.; Galea, S.; Gracia, J.N. Public Health COVID-19 Impact Assessment: Lessons Learned and Compelling Needs. NAM Perspect. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, L.; Aldasoro, E.; O’Brien, Á.; Nolan, M.; McGovern, C.; Carroll, Á. Ethical values and principles to guide the fair allocation of resources in response to a pandemic: A rapid systematic review. BMC Med. Ethics 2022, 23, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clay, L. COVID-19 and Social Determinants of Health Data Collection Instrument Repository; Research Instrument Repository: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 Pandemic Triggers 25% Increase in Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Worldwide. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Emanuel, E.J.; Persad, G. The shared ethical framework to allocate scarce medical resources: A lesson from COVID-19. Lancet 2023, 401, 1892–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academy of Medicine. Emerging Stronger from COVID-19: Priorities for Health System Transformation; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlinger, N.; Wynia, M.; Powell, T.; Hester, D.M.; Milliken, A.; Fabi, R.; Jenks, N.P. Ethical Framework for Health Care Institutions Responding to Novel Coranavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): Guidelines for Institutional Ethics Services Responding to COVID-19; The Hastings Centre: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M.C. (Ed.) The Ethics of Pandemics; Broadview Press: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (NIPHE). Signaling and Risk Assessment of Emerging Zoonoses. 2019. Available online: https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2019-04/011192_Folder%20signalling%20zoonoses_A5_V1_TG_0.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP); Adisasmito, W.B.; Almuhairi, S.; Behravesh, C.B.; Bilivogui, P.; Bukachi, S.A.; Casas, N.; Becerra, N.C.; Charron, D.F.; Chaudhary, A.; et al. One Health: A new definition for a sustainable and healthy future. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.B. One Bioethics for COVID 19? Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 619–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). Rapid Expert. Consultations on the COVID-19 Pandemic: 14 March 2020–8 April. 2020; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, H. Why a Teenager’s Bird-Flu Infection Is Ringing Alarm Bells for Scientists. Nature 20 November 2024. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-03805-4 (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). H5 Bird Flu: Current Situation. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/situation-summary/index.html (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Anthony, R.; Miller, D.S.; Hoenig, D.E.; Millar, K.M.; Goodwin, J.; Dean, W.R.; Grimm, H.; Meijboom, F.L.M.; Murphy, J.; Persico Murphy, E.; et al. Incorporate ethics into US public health plans. Science 2024, 383, 1066–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, G.A.; Torjussen, A.; Reeve, C. Companion animal adoption and relinquishment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Peri-pandemic pets at greatest risk of relinquishment. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 30, 1017954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavad, A. Pets Abandoned in Huge Numbers Amid COVID Second Wave. 2021. Available online: https://www.deccanherald.com/metrolife/metrolife-lifestyle/pets-abandoned-in-huge-numbers-amid-covid-second-wave-1001155.html (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Bowen, J.; García, E.; Darder, P.; Argüelles, J.; Fatjó, J. The effects of the Spanish COVID-19 lockdown on people, their pets, and the human-animal bond. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 40, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salois, M.; Golab, G. The COVID-19 Pet Adoption Boom: Did It Really Happen? Dvm360 52 August. 2021. Available online: https://www.dvm360.com/view/the-covid-19-pet-adoption-boom-did-it-really-happen- (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Brooks, S.K.; Greenberg, N. The Well-Being of Companion Animal Caregivers and Their Companion Animals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review. Animals 2023, 13, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, T. The Pentobarbital Shortage You Might Not Have Known About. 2021. Available online: https://www.aaha.org/publications/newstat/articles/2021-05/the-pentobarbital-shortage-you-might-not-have-known-about (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). COVID-19 Impacts on Food Production Medicine. 2020. Available online: https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/animal-health-and-welfare/covid-19/covid-19-impacts-food-production-medicine (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Enforcement Policy Regarding Federal VCPR Requirements to Facilitate Veterinary Telemedicine During the COVID-19 Outbreak Guidance for Industry. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/136319/download (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FACT SHEET: Veterinary Feed Directive Final Rule and Next Steps. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/development-approval-process/fact-sheet-veterinary-feed-directive-final-rule-and-next-steps (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Kogan, L.R.; Erdman, P.; Bussolari, C.; Currin-McCulloch, J.; Packman, W. The Initial Months of COVID-19: Dog Owners’ Veterinary-Related Concerns. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 629121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/faq.html#COVID-19-and-Animals (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Grandin, T. Temple Grandin: Big Meat Supply Chains Are Fragile. 2020. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/templegrandin/2020/05/03/temple-grandin-big-meat-supply-chains-are-fragile/#34c4e442650c4/5 (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Quain, A.; Mullan, S.; McGreevy, P.D.; Ward, M.P. Frequency, Stressfulness and Type of Ethically Challenging Situations Encountered by Veterinary Team Members During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 647108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baysinger, A.; Senn, M.; Gebhardt, J.; Redemacher, C.; Pairis-Garcia, M. A case study of ventilation shutdown with the addition of high temperature and humidity for depopulation of pigs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2021, 259, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, D. The Closure of Meatpacking Plants Will Lead to the Crowding of Animals. The Implications Are Horrible. 2020. Available online: https://www.vox.com/2020/5/4/21243636/meat-packing-plant-supply-chain-animals-killed (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Cima, G. Slaughter Delays Lead to Depopulation: Farms Short of Room as Processors Halt or Slow Meat Production Because of COVID-19. JAVMA News. 2020. Available online: https://www.avma.org/javma-news/2020-06-15/slaughter-delays-lead-depopulation (accessed on 30 May 2020).

- Grandin, T. Methods to Prevent Future Severe Animal Welfare Problems Caused by COVID-19 in the Pork Industry. Animals 2021, 11, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, R.; Danley, S. MAP: COVID-19 Meat Plant Closures. 2020. Available online: https://www.meatpoultry.com/articles/22993-covid-19-meat-plant-map (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Marchant-Forde, J.N.; Boyle, L.A. COVID-19. 2020. Effects on Livestock Production: A One Welfare Issue. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 585787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnepf, R.; Monke, J. COVID-19, U.S. Agriculture, and USDA’s Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP). 2020. Available online: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46347 (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- American Association of Swine Veterinarians (AASV). Farming Crisis Operations Planning Tool. 2020. Available online: https://www.aasv.org/Resources/publichealth/covid19/farm_crisis_operations_planning_tool.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Peel, D. Beef supply chains and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Anim. Front. 2021, 11, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). Evaluating Emergency Euthanasia or Depopulation of Livestock and Poultry. 2020. Available online: https://www.avma.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/Humane-Endings-flowchart-2020.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Kevany, S. Millions of Farm Animals Culled as US Food Supply Chain Chokes Up. The Guardian. 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/apr/29/millions-of-farm-animals-culled-as-us-food-supply-chain-chokes-up-coronavirus (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Tokach, M.D.; Goodband, B.D.; DeRouchey, J.M.; Woodworth, J.C.; Gebhardt, J.T. Slowing pig growth during COVID-19, models for use in future market fluctuations. Anim. Front. 2021, 11, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, T. Welfare slaughter of livestock in emergency situations. Can. Vet. J. 2006, 47, 737. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, J.T.; Rouse, R.C.; Craig, T.J. Animal Welfare in a Pandemic: What Does COVID-19 Tell Us For the Future? CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magouras, I.; Brookes, V.J.; Jori, F.; Martin, A.; Pfeiffer, D.U.; Dürr, S. Emerging Zoonotic Diseases: Should We Rethink the Animal–Human Interface? Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 582743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dobbenburgh, R.; De Briyne, N. Impact of COVID-19 on animal welfare. Vet. Rec. 2020, 187, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Briyne, N.; Dalla Villa, P.; Watson, C.; Prasarnphanich, O.; Huertas, G.; Dacre, I. Integrating animal welfare into disaster management using an ‘all-hazards’ approach. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2020, 39, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons-Duffin, S. CDC Is Criticized for Failing to Communicate, Promises to Do Better. 2022. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2022/01/07/1071449137/cdc-is-criticized-for-failing-to-communicate-promises-to-do-better (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Davis, T.; LaCour, M.; Goldwater, M.; Hughes, B.; Ireland, M.E.; Worthy, D.A.; Gaylord, N.; Van Allen, J. Communicating about diseases that originate in animals: Lessons from the psychology of inductive reasoning. Behav. Sci. Policy 2020, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, C.; Haworth, L.; Lee, B. Is a Scientific Assessment of Risk Possible? Value Assumptions in the Canadian Alachlor Controversy. Dialogue 1991, 30, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Villa, P.; Ellis, D.; Golab, G.; Gruszynski, K.; Hammond-Seaman, A.; Moody, S.; Noga, Z.; Pawloski, E.; Ramos, M.; Simmons, H.; et al. Overcoming the Impact of COVID-19 on Animal Welfare: COVID-19 Thematic Platform on Animal Welfare. 2020. Available online: https://bulletin.woah.org/?p=15661 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- National Biodefense Strategy and Implementation Plan. White House. 2022. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/National-Biodefense-Strategy-and-Implementation-Plan-Final.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- American Pandemic Preparedness Plan (APPP). White House. 2021. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/American-Pandemic-Preparedness-Transforming-Our-Capabilities-Final-For-Web.pdf?page=29 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National One Health Framework to Address Zoonotic Diseases and Advance Public Health Preparedness in the United States. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/media/pdfs/2025/01/354391-A-NOHF-ZOONOSES-508_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- USDA-NIFA Wellanimal Project. Available online: https://portal.nifa.usda.gov/web/crisprojectpages/1025509-wellanimal--animal-agriculture-and-the-new-coronavirus-sars-cov-2covid-19-values-aware-research-and-better-science-ethics-communication-to-promote-farm-animal-welfare-and-prepare-for-the-next-no.html (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Anthony, R. Emerging Stronger from COVID: A Thematic Analysis of US Veterinarians’ and Food Bioethicists’ Perspectives on Pandemic Preparedness, Animal Welfare and Ethics. In Proceedings of the Veterinary Ethics Conference 2023, Messerli Research Institute, University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, Austria, 27–29 September 2023; pp. 91–93. [Google Scholar]

- Prickett, R.W.; Norwood, F.B.; Lusk, J.L. Consumer preferences for farm animal welfare: Results from a telephone survey of US households. Anim. Welf. 2010, 19, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.; Tonsor, G.T.; Lusk, J.L.; Schroeder, T.C. Benchmarking US consumption and perceptions of beef and plant-based proteins. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2022, 45, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables Using Stata, 2nd ed.; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, D.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- McFadden, S.M.; Malik, A.A.; Aguolu, O.G.; Willebrand, K.S.; Omer, S.B. Perceptions of the adult US population regarding the novel coronavirus outbreak. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudau, A.; Masou, R.; Murdock, A.; Hunter, P. Public service resilience post-Covid: Introduction to the special issue. Public Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herten, J.; Bovenkerk, B. The Precautionary Principle in Zoonotic Disease Control. Public Health Ethics 2021, 14, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, B.; Arras, J.D. Ethical aspects of public health emergency preparedness and response. In Emergency Ethics: Public Health Preparedness and Response; Jennings, B., Arras, J.D., Barrett, D.H., Ellis, B.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- De Paula Vieira, A.; Anthony, R. Reimagining Human Responsibilities Towards Animals for Disaster Management in the Anthropocene. In Animals in Our Midst: The Challenges of Co-Existing with Animals in the Anthropocene; Bovenkerk, B., Keulartz, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 223–254. [Google Scholar]

- Nordgren, A. Pandemics and the precautionary principle: An analysis taking the Swedish Corona Commission’s report as a point of departure. Med. Health Care Philos. 2023, 26, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, B.; Tyson, A. Americans’ Trust in Scientists, Positive Views of Science Continue to Decline. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2023/11/14/americans-trust-in-scientists-positive-views-of-science-continue-to-decline/ (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Deane, C. Americans’ Deepening Mistrust of Institutions. 2024. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/trend/archive/fall-2024/americans-deepening-mistrust-of-institutions (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Tyson, A.; Kennedy, B. Public Trust in Scientists and Views on Their Role in Policy Making. 2024. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2024/11/14/public-trust-in-scientists-and-views-on-their-role-in-policymaking/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Achenbach, J.; McGinley, L. Another Casualty of the Coronavirus Pandemic: Trust in Government Science, Washington Post. 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/covid-trust-in-science/2020/10/11/b6048c14-03e1-11eb-a2db-417cddf4816a_story.html (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Webb Hooper, M. From Distrust to Confidence: Can Science and Health Care Gain What’s Missing? 2024. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/trend/archive/fall-2024/from-distrust-to-confidence-can-science-and-health-care-gain-whats-missing (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Frieden, T.R.; McClelland, A. Preparing for Pandemics and Other Health Threats: Societal Approaches to Protect and Improve Health. JAMA 2022, 328, 1585–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Jia, J.; Li, J.; Liu, S. Analysis of public information demand during the COVID-19 pandemic based on four-stage crisis model. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 964142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).