1. Introduction

In recent years, in response to climate change, pandemics, natural disasters [

1,

2], and compounded economic-social challenges, rural resilience has emerged as a critical research frontier with sustained scholarly attention. Conceptualized as complex socio-ecological systems [

3,

4], rural resilience refers to the capacity of rural communities to adaptively respond to external shocks while maintaining essential functions and advancing livelihood sustainability through structural transformation [

5]. This concept has gained significant traction in global policy discourse, as it is seen as a prerequisite for sustainable development, particularly within the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which explicitly calls for “building the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations” (Target 1.5) and promoting “resilient agricultural practices” (Target 2.4) (United Nations, 2015).

Research on rural resilience has focused on sudden, fast-onset shocks such as earthquakes, floods and pandemics and their impacts on rural communities [

6,

7,

8]; however, there is relatively limited attention given to enhancing rural resilience against slow-onset disturbances, especially amid such protracted anthropogenic challenges as brain drains, community loss, economic recession, ecological degradation and cultural corrosion [

9,

10]. Since the 21st century, the government debt and regional development imbalance under the capitalist economic crisis have once again brought rural issues onto the global social and economic development agenda. As a result, academics have increasingly emphasized the need to rebuild rural communities’ capacity to withstand these slow-onset disturbance [

4,

11,

12]. Interestingly, the previous literature highlights a key distinction: in the global North, resilience discourse emphasizes social responsibility, whereas in the global South, it focuses more on government responsibility. The state’s withdrawal and cuts to the welfare sector have led to criticism of resilience discourses for shifting responsibility onto vulnerable rural communities, encouraging them to manage essential services on their own [

13,

14,

15]. The point is, in structurally unequal rural areas affected by globalization, industrialization, and urbanization, the question remains: how can these communities generate the necessary capacity to resist such challenges? While some communities may be starting from a higher point of resilience, the gap between them and others will likely continue to widen. In this sense, rural resilience should be viewed as “a goal to be explored and achieved rather than a presumption from which analysis begins” [

16,

17]. Rural resilience building is a dynamic, multifaceted process, and as Wilson (2012) suggests, strengthening one aspect of resilience at a given point in time can lead to the weakening of others [

5], potentially making long-term sustainability difficult. This underscores the importance of adopting an integrated strategy for building rural resilience and suggests that the assessment and research of rural resilience should consider a prolonged time horizon.

China, as one of the fastest growing emerging countries, provides an ideal research context for rural resilience building. In the face of complex dynamics, China also emphasizes rural community capacity building and the creation of economic growth, but it has taken a different approach. Specifically, it has implemented a coherent rural resilience-building strategy through the reaching-in state, which refers to a governance model where the state actively and systematically penetrates rural society through administrative systems, policy interventions, and resource allocation to steer development processes. This concept highlights the state’s dominant role in orchestrating socio-economic transformations in rural areas from top down, distinct from community-led or market-driven approaches commonly observed in Western contexts. This strategy leads to comprehensive changes in rural economic, social, cultural, political, and natural-ecological aspects [

18,

19]. It is important to note that studying rural resilience building within the Chinese context is crucial. On the one hand, China’s industrialization and urbanization have made remarkable achievements; however, a series of urban-oriented institutional arrangements overlaid with market mechanisms have led to a continuous exodus of factors from China’s rural areas, resulting in the abandonment of arable land, stagnation of agricultural production and the community economy. Moreover, the emphasis on modern agricultural technology and foreign capital investment during the “New Socialist Countryside Construction” (NSCC) has not only failed to address the underlying issues but has also imposed additional pressure on local ecosystems. Worse still, it has intensified the erosion of traditional culture and contributed to the fragmentation of community structures. In this sense, the decline of rural areas in China follows a similar trajectory to global rural decline. On the other hand, China has adopted a differentiated approach compared to the Global North, namely, specifically by triggering the creation of rural community support spaces through the reaching-in state. This approach offers valuable practical insights for the Global South in advancing rural resilience building and strengthening state responsibility, with implications that could extend globally. After all, it does not make sense to advocate for self-reliance and self-help if we focus on those rural localities that are already structurally disadvantaged and lack support, as many studies have already demonstrated.

Although existing research has explored rural resilience in China, such as Wilson’s case study of Hu Village, which found that integrating rural areas into a more market-oriented economic system not only enhanced the social, economic, and cultural capital of rural communities but also led to a weakening of natural and political capital, it also pointed out that the process of enhancing community capital across different dimensions is a zero-sum game [

20]. While there is some empirical research challenging Wilson et al. (2018), Zhou & Gu (2025) recently underline and depict a possibility of local initiatives or support systems for rebuilding rural resilience, and reveals that industrial transformation could act as a catalyst for the enhancement of rural resilience in economic aspect, triggering a cascading effect of the social, cultural, political and environmental aspects [

20,

21]. It provides us with enriched knowledge about practical paths and rural resilience enhancement; however, some other issues that need to be further clarified. On one hand, we are curious about the reasons behind the differences in the conclusions of the aforementioned studies. Why, in the context of rural China, do efforts to rebuild economic capital in some villages lead to the erosion of natural-ecological or social-cultural resilience, while in others, they can stimulate a spiral upward chain effect in community capital? On the other hand, the process mechanisms of rebuilding rural resilience have not been fully explored. The main reason for this is that the studies mentioned are snapshots of specific moments in time rather than a continuous timeline, which may result in the loss of pivotal insights hidden in the process [

21].

The issues outlined above indicate that the present paper considers rural resilience building within a broader socio-political context, linking it with rural transformation theory. It also focuses on the process of rural resilience enhancement and the interactive mechanisms of community capital across different dimensions. Based on this, the study will draw on the practical experience of building rural resilience in a village in Western China using the neo-endogenous approach. The neo-endogenous development paradigm, which originated from European rural development practices such as the EU LEADER program, emphasizes the synergy between local initiatives and extra-local resources, positing that development is most sustainable when it leverages local assets while strategically engaging with external networks and knowledge [

22,

23]. However, a recurring theme in the literature is the implicit prerequisite of a certain level of pre-existing social capital and community agency—often described as a ‘close-knit society’. This study seeks to extend this conversation by exploring how neo-endogenous development can be initiated in contexts where such conditions are initially weak or fragmented. The longitudinal case analysis will be used to decode the practical process and underlying mechanisms at play.

Through this empirical investigation, this study aims to develop the concept of an “enabling government”—a governance paradigm where the state facilitates rural resilience building not through direct intervention, but by creating a support ecosystem that enhances communities’ resource absorption capacity and fosters the conditions for self-sustaining development. This conceptual lens emerges from our longitudinal findings and serves as an analytical framework to examine how state-community interactions evolve throughout the resilience building process.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section discusses the existing body of research concerning the process of rural resilience enhancement and a clarification of a shift in exogenous model to neo-exogenous & neo-endogenous approaches. In the third section, the methodology and data sources employed in our study are introduced, along with an overview of Jianta Village’s resilience dynamics.

Section 4 outlines the process of Jianta Village’s resilience enhancement, while

Section 5 discusses neo-endogenous elements and the mechanisms of building rural resilience within China’s practice. The final section presents concluding insights and deliberations, encapsulating the broader implications of our findings and their limitations.

2. Understanding Building Rural Resilience in China: Process and Issues

Existing research on rural resilience building primarily focuses on the community capital perspective, revealing the pivotal importance of external investment in enhancing economic resilience. However, the reason why these external investments have led to differentiated practical outcomes has not been explained. In fact, some insights may be gained from rural transformation theory and its application in the Chinese context. After years of exploration, the policy practices for rural transformation in China have transitioned from exogenous model to neo-exogenous & neo-endogenous approaches [

24], evolving from a focus on singular economic growth to a comprehensive transformation that encompasses all aspects of rural resilience.

In the early years of socialist China, agricultural surplus was extracted through a mechanism of exploitation, facilitated by the People’s Commune system, the unified procurement and marketing system, and the household registration system. These measures integrated rural society, controlled agricultural production, and regulated population movement. The excessive penetration of party-state power led to a singular rural economy and limited income channels for farmers. The reform and opening-up of 1978 shifted the state’s focus to urban areas, simultaneously withdrawing from exercising power in rural regions. As a result, rural areas implemented self-governance, with the Village Committee (VC) as the governing body, extracting a portion of agricultural taxes and fees to provide public services for the village. As a consequence of an urban-centric developmental decision-making system, alongside the withdrawal of the state, local governments struggle with the provision of public services due to reduced revenues in rural China, leading to a “hollowing-out” rural structure, with a steady outflow of human capital, the abandonment of cultivated land, the erosion of traditional culture and the breakdown of social relations. Although it seems that China shares notable similarities with the global North, in contrast to its de-agrarianizing and de-communalizing tendencies, agriculture and rural development have always held a central position in China’s policy framework.

After entering the 21st century, the party-state shifted from “grabbing hands” to “helping hands” and deployed a series of policies specifically to support rural restructuring and socioeconomic development, such as abolishing agricultural taxes, implementing the NSCC campaign, aiming to invest in basic infrastructures and social security and seek to attract new money from the private sector. However, due to being deeply embedded into the global capitalist system, many households tended to adopt laborsaving strategies such as mechanization and especially the substitution of traditional environmentally friendly farm practices with artificial fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides, which then led to weak resilience in the natural/environmental domain. To make matters worse, the abolition of the agricultural tax had left the VC without the financial base to provide public services. Thus, the party-state’s cumulative investment of more than 6 trillion yuan was not converted efficiently, and even led to pernicious economic effects in some areas, such as endemic corruption and elite capture, which is caused by a top-down, exogenous development practice. More fundamentally, this is because the VC as the main body of rural governance has already existed in name only, leading to the lack of structural strength within the village to undertake state input resources, which is often criticized as a top-down, exogenous development practice. Under such circumstances, the input of national resources is not only difficult to leverage rural development, but may breed class differentiation and widen the income gap of farmers due to the lack of autonomy.

In response to these challenges, the Targeted Poverty Alleviation (TPA) was proposed by the Xi administration, which intends to provide tailored resources to villages with resource constraints. It is worth mentioning that, in order to address the resource misallocation caused by the structural disadvantages of rural areas, this period saw the promotion of work through the method of embedding village-stationed officials, emphasizing the activation of endogenous forces, which effectively improved the efficiency of resource conversion. With the alleviation of poverty, the National Rural Revitalization Strategy (NRRS) was further announced in 2017, aiming to put rural and urban development on an equal footing. At this time, benefiting from the lessons and experience of the period of NSCC and TPA, the activation of internal motivation in the process of resource input has once again become the action guide for local governments, which emphasizes activating rural endogenous organizations through empowerment. In addition to the emphasis on industry, talent, ecology, and wealth in previous strategies, organizational revitalization was officially included in the overall goals for the first time. Generally speaking, a community-based approach often follows two pathways based on differences in local political and economic environments. The first is the new exogenous development, where vertical CPC party networks are built through the construction of village party committees [

24]. Essentially, this approach integrates villages into a top-down management system through state-sponsored social mechanisms, and its effectiveness depends on the strong financial support and mobilization capacity of local governments. The second is to empower rural organizations that can represent internal interests through neo-endogenous approach to stimulate the growth of horizontal networks and strengthen local and extra-local resources. It is noted that unlike the strong dependence on the third sector of the Global North, China is currently characterized by a “strong state, weak society” dynamic. This implies that a well-developed third sector does not naturally exist, and instead, the intervention of the state (a vertical force) to catalyze the emergence and growth of social organizations (horizontal networks)—a critical aspect that has been largely overlooked in the existing literature.

In light of this, theorizing neo-endogenous practices in China may contribute to existing literature in two key ways. On one hand, by conceptualizing the process through which China generates horizontal networks through vertical force, it deepens the academic understanding of the neo-endogenous approach and accelerates the dialogue between China’s practice and rural transformation theory. On the other hand, by analyzing how China, with a “strong state, weak society”, generates horizontal networks and activates local and extra-local resources, then in turn, how they contribute to rural resilience, it helps clarify the role of the government and its significance in a weak institutional environment for building rural resilience.

3. Research Design

3.1. Case Study Approach

The research on rural economy and development differs from general studies, as the integration of theory and practice determines the applicability of case study analysis in this field. Rural resilience building and neo-endogenous model have been central topics in global sustainable development for an extended period. However, as Smith (2020) poignantly observes [

25], ‘The field’s intellectual energy has dissipated into a thousand rivulets of micro-inquiry, none converging toward an explanatory sea’, even though it is an urgent issue that needs to be addressed. Case study analysis has an obvious advantage in developing theories in this regard. On one hand, the case study approach is well-suited for analyzing complex social phenomena, often used to describe, analyze, and deconstruct intricate events in order to uncover underlying patterns. Rural vulnerability is often seen as the result of excessive externalization, while the neo-endogenous model emphasizes outward-oriented pathways. However, the operational mechanisms through which the neo-endogenous development approach can be effectively applied to enhance rural resilience remain insufficiently explored, particularly regarding the decision-making logic and adaptive strategies adopted by localities in this dynamic process. On the other hand, case study analysis is conducive to generating novel knowledge by focusing on key aspects of specific cases, which helps uncover deep insights from particular phenomena. The theory of the neo-endogenous model originates from neoliberal practices in the European Union, emphasizing community-led horizontal network building. However, the question arises: How can neo-endogenous practice emerge in rural communities in the Global South that are generally facing structural decline? The aforementioned issues transcend the scope of causal identification methodologies, necessitating a case study method to elucidate the process and mechanisms of rural resilience enhancement through neo-endogenous approach.

3.2. Case Selection and Brief Review

Based on the principle of theoretical sampling [

26], this study emphasizes the typical characteristics of the case and its alignment with the research agenda. It focuses on how to build rural resilience amid the global trend of rural decline, specifically examining the stages of transformation and the process mechanisms of shifting from backward villages to resilient ones. In line with the core issues and context, this study selects Jianta Village from China as the case study.

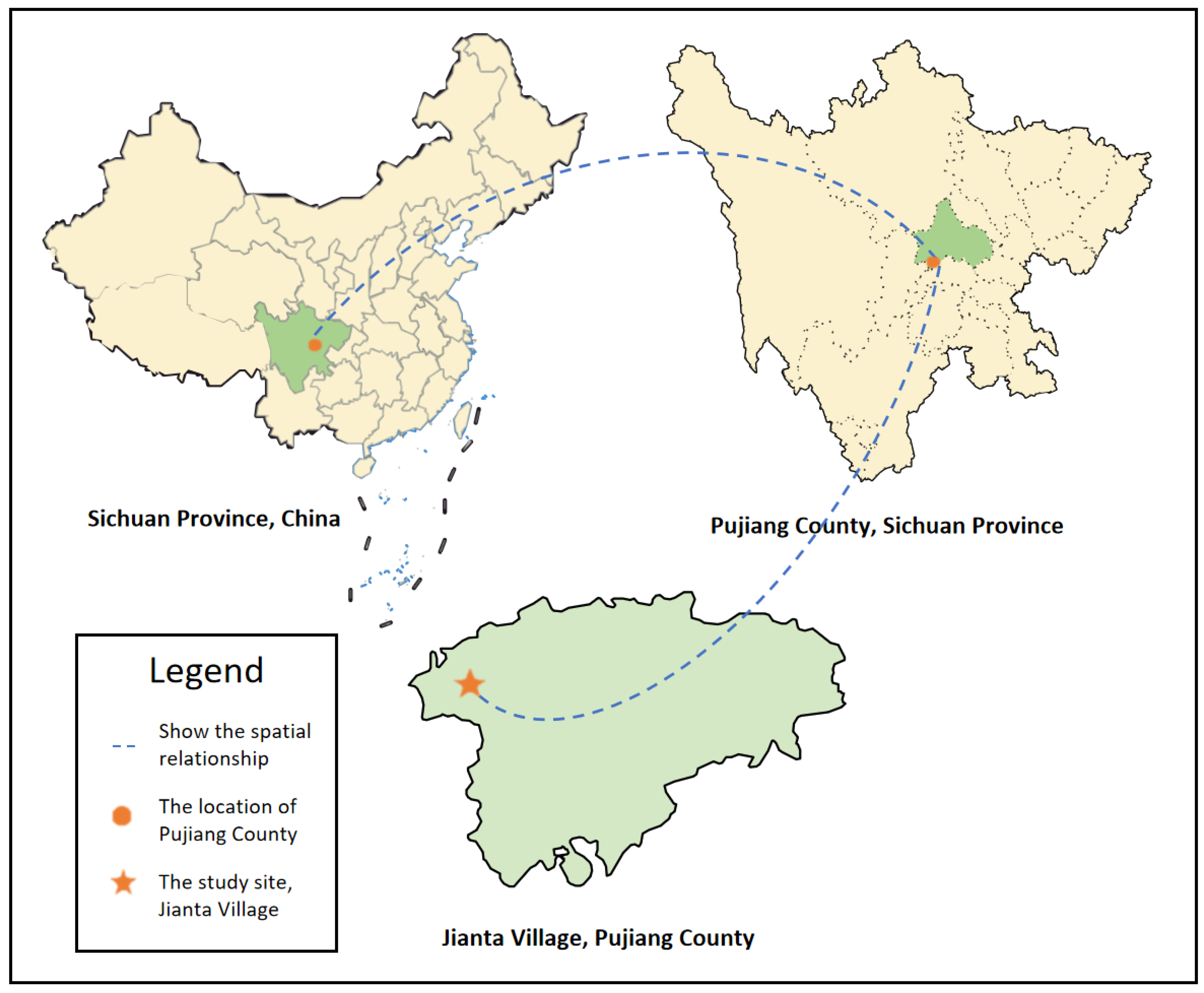

As shown in

Figure 1, Jianta Village (30°12′2.8″ N, 103°31′10.6″ E) is located in southern Sichuan Province, under the jurisdiction of Pujiang County in Chengdu. Situated in the transition zone between Chengdu Plain and Longmen Mountains, the terrain is mainly hilly (67.35%), flat dam (20.25%), and mountainous (12.4%), with a relatively higher topographic diversity. As an ancient village, Jianta has benefited from favorable natural conditions and a pleasant climate. Its diverse terrain has been conducive to various agricultural activities. The village has a rich historical and cultural heritage, having served as a military garrison during the Tang Dynasty, a site visited by Marco Polo during the Yuan Dynasty, and an official postal station along the Southern Silk Road during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. It is also home to numerous folkloric traditions and intangible cultural heritage, preserving the collective memories of its residents.

However, in modern times, the state’s urban-oriented development strategy has led to agriculture and rural areas being viewed as backward, high-risk, and low-return sectors. This perception was largely shaped by mainstream media discourse. Rural inhabitants, influenced by these views, have often been reluctant to engage in agricultural production or remain in rural areas unless driven by necessity, such as limited livelihood options or the need to care for elderly relatives or children. As a result, the local agricultural development model focused primarily on subsistence farming. Driven by short-term profit motives, some agribusinesses exacerbated environmental degradation, prioritizing immediate crop yields over long-term soil conservation. These businesses have often applied chemical fertilizers and pesticides indiscriminately, while using synthetic growth regulators and artificial additives to enhance the marketability of produce through visual standardization. A dual-purpose land use pattern has emerged, where rural households have strategically allocated land between subsistence cultivation and commercial production. This practice reflects an urban-rural epistemic divide, especially in the divergent perceptions of food safety risks. Jianta’s case exemplifies a multidimensional rural decline, characterized by brain drain, cultural erosion, industrial stagnation, and ecological deterioration, which has reinforced the village’s socio-ecological degeneration. In short, Jianta Village has faced prolonged challenges, including continuous brain drain, cultural loss, industrial decay, and environmental degradation. By 2015, it was recognized as a poverty-stricken village, with a per capita income of 8000 yuan. In contrast, by 2023, the per capita disposable income had risen to 30,000 yuan, and the village’s collective economic income surged from 1780 yuan in 2016 to 300,000 yuan in 2024. In response, the local government sought to reverse this decline by investing in infrastructure and promoting income-generating industries.

Furthermore, a key component of China’s poverty alleviation policy involved dispatching urban government officials to rural areas, where they served as village-stationed officials for at least two years. Mr. Wu, a young official from the Chengdu Municipal People’s Political Consultative Conference with an interest in rural culture, served as the village-stationed official in Jianta. Pujiang County subsequently implemented a comprehensive community-building initiative aimed at strengthening collaborative governance across urban–rural boundaries. This was achieved through outsourcing specialized services to qualified third-party entities and implementing capacity-building initiatives focused on grassroots organizational development. These efforts have successfully catalyzed a remarkable reversal in human capital: the number of local volunteers grew from zero in 2016 to 276 by 2022, community self-organizations increased from one to five, and the cohort of “new villagers” and entrepreneurs expanded from virtually none to 31 and 53 individuals, respectively, by 2024. During his two-year service, accredited social organizations leveraged their professional expertise to foster community learning, emphasizing the revitalization of civic consciousness and the establishment of sustainable mechanisms for collective agency. As a result, Jianta Village has avoided the fate of continued decline, maintaining a high level of stability and resilience even after the withdrawal of the village cadre post-poverty alleviation—an outcome that distinguishes it from other villages that remain highly dependent on external resources.

The selection of Jianta Village as the observation case is based on the following considerations: First, Jianta Village has successfully transitioned from a low-level equilibrium to a high-level equilibrium in terms of rural resilience. This achievement is primarily attributed to the restructuring of rural dynamics and the urban-rural relationship. Despite enduring challenges, such as prolonged droughts, the COVID-19 pandemic, and shocks to agricultural product market prices in recent years, the village has managed to navigate these crises smoothly, demonstrating remarkable rural resilience. The village’s revitalization is further evidenced by its cultural and touristic dynamism: annual tourist visits soared from zero in 2016 to 40,000 by 2023, and public cultural activities increased dramatically from one to 139 per year. Second, Jianta Village has not been subjected to extraordinary external interventions, such as government demonstration projects or large-scale corporate investments. Additionally, it does not possess unique internal resource endowments. While its rich, dormant cultural capital has been noted, this is a common trait shared by many villages in China with a long agricultural history. What distinguishes Jianta is its ability to avoid the persistent decline seen in many similar villages. Analyzing Jianta’s development offers valuable insights into rural resilience building for other villages facing similar challenges. Third, the development trajectory of Jianta Village has been shaped by the involvement of multiple actors, including the government, social organizations, and urban residents. This diversity of forces provides valuable material for analyzing the relationships between these actors and their interaction mechanisms with rural communities. Furthermore, these external forces are not tied to Jianta’s unique resource bundle, but are embedded within the broader context of national politics and local economic and social structures. This highlights that selecting Jianta Village as a case for studying rural resilience-building practices allows for a deeper analysis of micro-level practices while also connecting with macro-level institutional structures.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3.3.1. Data Collection

This is a longitudinal study, which allows for continuous tracking to capture the dynamic evolution of social events over time, such as policy iterations, changes in group behavior patterns, and the chain reactions of key events. It also utilizes iterative data triangulation to thoroughly assess the stability of the case sample [

27,

28]. From September 2017 to January 2025, our team conducted field investigations in Jianta Village everyone to one and a half years. Each visit lasted between one to three days, and in January 2025, we conducted a two-week follow-up study. In total, our research team visited Jianta Village 15 times. Over eight years of continuous tracking, we were able to observe the deep-seated patterns of development changes in Jianta Village, and verify the cumulative effects brought by the participation of multiple stakeholders in its development. During the research process, we conducted interviews, participant observation, and wrote meeting minutes, field notes, and reflective diaries. We also collected and analyzed the available literature, including government reports and policy documents. We conducted systematic research on five key topics, including green production transformation, alternative food systems, rural endogenous development, social organization participation in rural transformation, and resilience support system.

The data collection methods used for this study include semi-structured interviews, secondary data collection, and participatory observation. The interviewees consisted of staff from the agricultural bureau, rural officials, local villagers, community workers, business owners, and employees hired by these businesses, with ages ranging from 25 to 70 years old. The data sources cover the specific situations of various government bodies, businesses, social organizations, and farmers. In addition to recording direct observations, we also deeply engaged in key activities related to the development of Jianta Village through participatory observation, such as attending the most relevant and attractive annual pig sacrifice festival in Jianta Village, participating in the Tangwu regular meetings related to village affairs consultation governance, and similar social governance salons like village official training.

Table 1 outlines the specific data collection methods, subjects, quantities, durations, and other information. Pseudonyms were used during interviews to ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

3.3.2. Data Analysis Strategy

The interview records, meeting minutes, field notes and reflective diaries were all written in Chinese. The research team translated and coded the cleaned and organized interview records into English, while other data were used for cross-validation and to help identify the rural resilience enhancement process. After cleaning and coding the data, a combination of temporal segmentation and narrative strategies was employed for further analysis. On the one hand, the temporal segmentation strategy divides the data into continuous and adjacent phases, clearly illustrating how actions in different time intervals influence changes in the context and, in turn, drive the evolution of behavior in subsequent phases. This approach emphasizes the interconnections and underlying mechanisms between different stages, providing a clear framework for analyzing dynamic changes across periods. On the other hand, the narrative strategy constructs a coherent storyline that contextualizes the complex research process and transformational phenomena, making them more vivid and easier to understand. The combination of these two strategies not only helps readers gain a tangible sense of the unique context in China, but also uncovers the driving mechanisms behind the evolution of each phase from a dynamic perspective, generating valuable insights in the process.

3.3.3. Research Quality: Trustworthiness and Rigor

The trustworthiness and rigor of this case study were ensured through the deliberate application of method-specific validation practices. To strengthen credibility, we implemented data triangulation by drawing upon semi-structured interviews, field observations, internal documents, and a systematic collection of archival materials—including comprehensive content from the village’s official WeChat public account and relevant media coverage. This range of sources allowed for cross-verification of key events and narratives. Additionally, investigator triangulation was achieved through collaborative coding within the research team, a process that also enhanced confirmability by reducing individual interpretive bias. Further verification was sought via member checking with key participants. Dependability is demonstrated through a transparent audit trail that documents the entire analytical process, while transferability is supported by the thick description afforded by the narrative and temporal analysis, contextualized and enriched by the publicly available media and social media records.

3.3.4. Three Stages and Main Events

From the perspective of the neo-endogenous model, rural development needs to break free from the “blood transfusion” path dependency inherent in the traditional exogenous model. Instead, it should seek a dynamic balance between fostering endogenous driving forces and integrating external resources [

29]. This theory emphasizes building on local resources and centering community agency, activating local knowledge systems and social capital through the catalytic influence of external factors [

29,

30,

31]. Its core lies in reconstructing the interactive relationship between “locality” and “modernity” [

32]. Since 2016, Jianta Village has gradually undergone a progressive process of “external support—community capital activation—self-reinforcement of rural resilience” during the transition from poverty alleviation to rural revitalization. Based on the evolutionary logic of the new endogenous development mechanism, this study divides Jianta Village’s development into three main stages: the Low-Equilibrium Initial Stage (2016–2017), the Trigger Stage (2017–2020), and the Self-Reinforcement Stage (2020-present). Each stage features key events that drive a transformation in the development paradigm (

Table 2). The stage division not only confirms the dynamic evolutionary pattern of “external intervention—internal activation—internal-external interaction” proposed in the new endogenous development theory, but also offers a practical and feasible new development path for other rural areas.

4. The Process of Building Rural Resilience Through Neo-Endogenous Approach

As described in

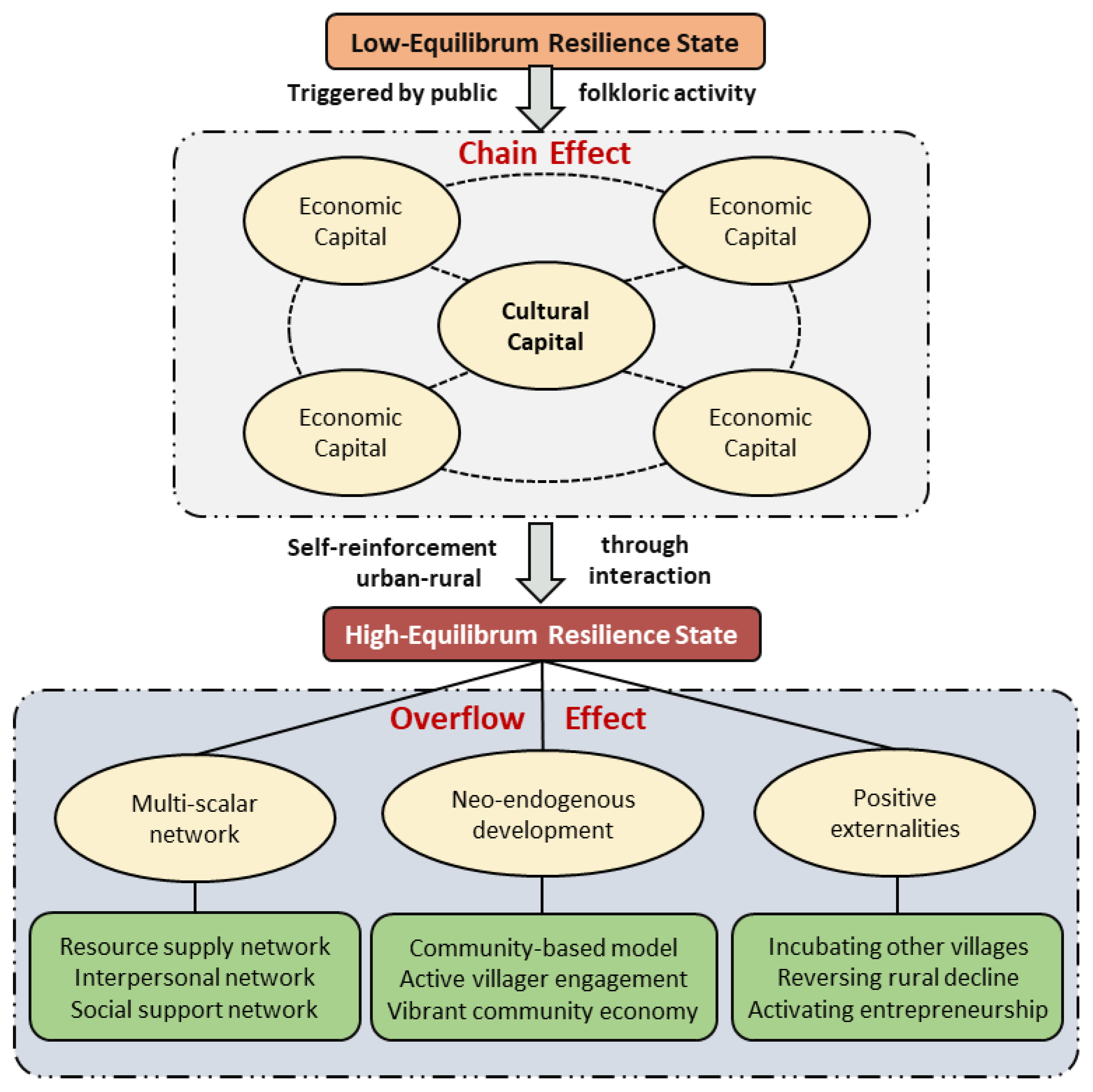

Section 3, we have divided the development of Jianta Village into three stages based on the key events it experienced, in conjunction with the new endogenous development theory. This subsection attempts to reveal the corresponding process mechanisms by depicting the specific transition of Jianta Village from a low-equilibrium resilience state to a high-equilibrium resilience state (as shown in

Figure 2), a process that has been overlooked in previous studies.

4.1. Initial Low-Equilibrium State of Rural Resilience

According to the field survey, the decline of Jianta Village before 2016 could be attributed to a vicious cycle of escalating resource loss and distorted perceptions of the village’s future. Driven by industrialization and urbanization, more than two-thirds of Jianta’s population left in search of employment, leading to intergenerational separation. Despite the village’s abundant natural and cultural resources, residents felt ashamed to stay in the village or engage in farming. The prevailing belief was that escaping rural life and settling in the city was the ultimate goal, even if it took generations to achieve. Villager Zhao remarked, “We failed to escape farming, and now we’re pinning our hopes on our two kids to study hard and change their fate” (F1, 2016). As a result, a significant migration of community elites to urban areas occurred, leading to a deterioration in the demographic structure of Jianta and contributing to cognitive limitations and industrial transformation challenges due to the brain drain.

After Jianta was designated as a municipal-level poverty-stricken village in 2016, the main focus shifted to revitalizing the community economy through agricultural modernization, with the dual objectives of increasing rural household incomes and promoting sustainable development. This initiative was led by Mr. Wu, the village-stationed official, who oversaw its implementation. Unlike model villages that received substantial government financial support for comprehensive planning and industrial restructuring, Mr. Wu’s efforts were limited. He attempted to stimulate the villagers’ endogenous motivation, encouraging a shift toward sustainable agriculture, and connected them with experts in soil improvement and fertilization techniques. However, the results were minimal. Farmer Cao explained, “Initially, he (referring to Mr. Wu) tried to persuade us to reduce pesticide and fertilizer use, switch to organic fertilizers, and replace herbicides with manual weeding. But we criticized this as absurd. We believed that without pesticides, we’d inevitably face pests and diseases, and organic fertilizers and manual weeding would increase costs (at least that was what we believed at the time). Who would cover those costs? We thought he was out of touch with reality, failing to recognize that there could be alternative possibilities for agriculture and rural development” (B3, 2016).

Breaking the low equilibrium in rural areas through industrial transformation proved to be exceptionally challenging. On one hand, the remaining population in the village faced strong cognitive constraints, as their entrenched ways of thinking made it difficult to recognize the potential value of agricultural transformation. On the other hand, rural areas remained somewhat isolated, with a clear divide between villagers and outsiders. Even when external knowledge and modern production techniques were introduced by village-stationed officials, villagers often rejected these efforts due to suspicion and distrust. Furthermore, agricultural modernization went beyond economic considerations; it was closely tied to the social capital within the community. However, the high level of social atomization in Jianta fractured the village’s social capital, hindering the creation of the cohesion necessary to enhance rural resilience. This was one of the deeper reasons why many initiatives focused solely on economic investment faced significant challenges in villages.

4.2. Chain Effect Through the Public Folkloric Activities

The starting point for rebuilding rural resilience in Jianta Village shifted with Mr. Wu’s realization that it might not lie in activating the community economy but in reviving cultural capital. Cultural capital, regarded as the soul of the community, holds the potential to awaken collective awareness and cultural identity among villagers. With this in mind, Mr. Wu traversed every corner of the village, consulting ancient texts and elderly villagers to piece together the historical relics and cultural heritage of Jianta Village. At first, the villagers were puzzled by his efforts. “He would ride his bike every day, carrying a notebook, wandering around the village and taking notes. We heard he was writing a village chronicle. At the time, we thought it was just a waste of time, working on an image project,” recalled villager Li (F3, 2017). After two years of painstaking research, Mr. Wu’s publication of the Chronicle of Jianta Village had a profound impact on the villagers. “Over the past two years, he spent time chatting with the elderly in the village and telling us about historical sites. I feel like he understands our village better than any of us,” said village committee member Li (S3, 2019). “Over time, I could still sense that he genuinely wanted to do something for the village. It was the first time I realized that Jianta Village had such a rich and profound history,” said villager Li (F3, 2019). The publication of the Chronicle of Jianta Village helped villagers understand their history and strengthened the trust capital between Mr. Wu and the community. However, rural resilience was not substantively enhanced, and Mr. Wu’s goal of using culture to bind the villagers together was not fully realized. Over time, the scattered historical memories began to fade once again.

The turning point came in 2017 with the Community Building Initiative, a local government response to the “Effective Governance” principle of the Rural Revitalization Strategy. This initiative aimed to recalibrate rural governance architectures by fostering participatory decision-making mechanisms, thereby institutionalizing grassroots autonomy and embedding sustainable development imperatives into local governance frameworks. Advocated by Mr. Wu, Jianta Village was designated as one of the ten pilot programs for community building. The local administration outsourced community development services through competitive bidding, contracting the professional NGO Anyishe Community Support Center (ACSC) to implement a two-year initiative. The strategy combined leadership cultivation with institutional mechanisms designed to foster autonomous community-based organizations through a participatory governance framework. Upon learning of previous attempts from Mr. Wu, the ACSC decided to focus on creating social ties among villagers through public cultural activities. After consulting key community members, it was decided to hold the Annual Pig Festival, transforming the traditional pig sacrifice ceremony into a public folkloric event at the village level. The community activists, with guidance, designed a multi-stage agenda to encourage broad participation. “At the beginning, I wanted to host a smoked meat-making competition or a cooking contest, but the community backbones pointed out that competitions imply rivalry. For rural communities, this would not only fail to inspire enthusiasm but might dampen their motivation. The activities were organized with input from community leaders, and as it turned out, the villagers themselves are the true authorities on local knowledge,” explained Mr. Wu (S1, 2018).

The revival of folkloric activities proved to be effective. Under the leadership of community leaders, villagers with skills in traditional opera, bamboo weaving, lacquerware, and even children, eagerly participated in performances. “It’s been decades since anyone sang the ‘Yaomei Lantern’ song. I thought, with all the rapid urbanization, people must have lost interest in it. But I never realized it was such a shared memory for everyone. A village... it needs its own voice,” said traditional folkloric artist Ms. Zeng (F4, 2018). The Yearly Pig Festival also featured a pig feast and a farmer’s market to involve more villagers in cooking and selling activities. With the efforts of the villagers, ACSC, and the local government, the event attracted nearly 200 households and over 800 urban citizens. The products at the farmer’s market were nearly sold out. Notably, the Annual Pig Festival has been sustained for eight consecutive years and has now been designated as a Provincial-Level Intangible Cultural Heritage. Its publicity has evolved significantly: initially promoted through the village’s WeChat public account and grassroots word-of-mouth, the event has grown into a large-scale folklore activity that now draws active attention from local governments and broader public engagement. Through the collaborative organization of the festival and the urban–rural interaction it fostered, the villagers’ confidence, self-reliance, and mutual trust were activated. They recognized the immense potential hidden within themselves and their village, creating an internal drive for the development of sustainable agriculture. In response, Mr. Wu and the community leaders decided to establish the Eco-Smallholder Alliance, initially involving over 50 participants. Mr. Wu also leveraged his political and social capital to connect Jianta Village with pre-production agricultural supplies, technical experts, and post-production consumer resources. Agricultural products, cultural goods, and leisure services from Jianta Village are almost entirely consumed through frequent urban-rural interactions and the expanding sustainable food community they have cultivated. Even amidst challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic, droughts, and increasing market competition, Jianta Village has found alternative paths due to the mutual assistance characteristic of its production and operational model, showing resilience in the face of repeated external shocks. “In 2022, we went through the worst drought since 1961, and our farm was in real trouble. What surprised us, though, was that our consumer community stepped up. Not only did they crowdsource funds to help us deal with the drought, but they also organized volunteer teams to come out and lend a hand at the farm,” recalled former village head Gao (R2, 2024).

The interpersonal interactions and social connections created through public folkloric activities triggered a chain effect that enhanced community capital, leading to a self-driven transition of farmers toward sustainable agriculture. This shift strengthened the social fabric within the village, fostering a more resilient and self-reliant community capable of navigating future challenges. The deeper reason lies in the fact that folkloric activities, by reconstructing cultural identity, expanded the space for villagers’ interactions and regenerated interpersonal connections. This created a self-reinforcing mechanism between cultural and social capital. The social-cultural space generated by these interactions accelerated the flow of resources, facilitated the spillover and renewal of local knowledge, and, in the process, broke cognitive constraints. This dynamic compelled villager to actively engage in agricultural transformation and public affairs, leading to the reconstruction of economic, ecological, and political capital. This validates the earlier assertion that agricultural transformation involved both the economic and social dimensions of the community. It also revealed that cultural capital served as an accelerator and catalyst for both dimensions, driving the synergy between economic and social change in the community (as shown in

Figure 3).

4.3. Self-Reinforcement Through Urban-Rural Interactions

To prevent potential systemic collapse upon the withdrawal of extra-local support, the ACSC focused on strengthening the village’s resource absorption capacity—its ability to effectively acquire and utilize external resources—by nurturing community activists and incubating community-based self-organizations. In 2018, the Jianta Village Development Association (JVDA) was established, comprising a board of directors, a board of supervisors, and a members’ representative assembly. Garnering unanimous recognition from villagers, the JVDA exhibited substantial momentum in enhancing community resilience.

Leveraging the significant benefits derived from public folkloric activities and CSA initiatives, the ACSC recommended that the JVDA prioritize fostering urban-rural interactions while developing community-branded activities aligned with agricultural cycles and biological rhythms. These activities included agricultural experience programs, farming culture study tours, and parent–child interactive projects—all rooted in the principles of sharing, collaboration, and inclusivity. In contrast to the conventional top-down planning and external concept implementation seen in many rural development efforts, Jianta Village’s community-branded activities demonstrated two key characteristics: active participation from villagers and a deep appreciation for indigenous knowledge systems. These initiatives underwent continual refinement through successive cycles of urban-rural engagement, representing a model of collaborative creation between urban and rural stakeholders. The approach to rural-urban integration successfully established an innovative experimental framework for reimagining rural-urban dynamics, engaging both local community members and urban participants who showed genuine commitment to contributing to the village’s sustainable development. This unique synergy resulted in exceptionally resilient and dynamic rural–urban interactions.

“Traditional urban recreational facilities have become increasingly unappealing. We now prefer exposing our children to authentic rural experiences and cultural heritage,” said government employee Ms. Wang.

(G4, 2023)

“Jianta Village is truly special—it has preserved the authentic essence of rural life. The villagers radiate warmth and hospitality, always eager to listen to our perspectives and incorporate our suggestions. For someone like me who has lived in the city for years, this place has become a spiritual sanctuary, a haven where I can reconnect with what truly matters,” shared Ms. Lu, a writer who left the city and settled in Jianta Village.

(F2, 2024)

Initially, a series of community-branded activities in Jianta Village aimed to identify and cultivate consumers for ecological agricultural products and cultural-tourism offerings. At that time, the rural-urban relationship was still primarily rooted in production and consumption dynamics, with rural areas remaining in a dependent position. Although public folkloric activities triggered a chain effect that quickly enhanced community capital, the rural community in a dependent state could not be considered to possess high resilience, a point often overlooked in many studies. Empirical observations indicated that the chain effect of community capital enhancement was a transient phenomenon, largely dependent on the presence of external interventions. Jianta Village successfully avoided this fate. Upon completion of the project, although the village cadres and the ACSC withdrew, Jianta Village did not regress to a low-level equilibrium resilience state after external intervention ceased, nor did it develop the completely independent ability to cope with the market as some literature had predicted. This ability, often exaggerated, was seen as one capable of severing all external support. Instead, Jianta Village facilitated the bidirectional flow of rural and urban elements and the deep integration of urban and rural industries through frequent rural-urban interactions. This process enabled the village to break free from its dependent position and, through the mutual reinforcement of social and cultural capital, generated a robust resource attraction capacity, ultimately displaying high-level equilibrium rural resilience and spillover effects.

This achievement calls for a structural analysis of its underlying mechanisms: First, Jianta Village is embedded in a multi-scalar network that exhibits dynamism, interactivity, and scalability. This includes the CSA community, school study tour programs, government-provided guarantees and services, as well as the village’s internal networks across industry, culture, and interpersonal relationships. On one hand, its external support network differs from the resource bundles tied to external forces in the triggering phase, as it is actively acquired through the frequent urban-rural interactions of the JVDA. This results in a more stable external support system compared to one bound by government intervention, and it is more community-oriented than commercial capital. On the other hand, its internal interaction network spans various dimensions, including agricultural production mutual aid, community industrial chain cooperation, socio-cultural interactions, and natural-ecological contracts. This multi-dimensional approach transcends the vulnerabilities associated with single-dimensional networks, thus providing a strong capacity for scalability.

Second, Jianta Village has activated new endogenous development through a community-based model, which emphasizes active participation from villagers and demonstrates a vibrant community economy. The neo-endogenous practice in Jianta Village differs from the neoliberal approach that shifts responsibility onto the community. Instead, it has generated a community support space through a reaching-in state. In this sense, neo-endogenous development relies on the empowerment of external forces. However, as has been noted, the goal of empowerment is not merely to equip the community with specific capacities but to co-construct a comprehensive community support ecosystem alongside these external forces.

Third, Jianta Village exhibits numerous positive externalities. It has attracted hundreds of village leaders for visits and has incubated over 40 resilient villages. These efforts have effectively reversed rural decline, leading to a continuous return of rural elites and the influx of new villagers, which has revitalized the village’s population system. As a result, the village is experiencing comprehensive prosperity in social, economic, and cultural aspects. Additionally, the village has stimulated vibrant entrepreneurial activities, with villagers developing a stronger sense of independence and confidence to improve not only their own situations but also the collective well-being of the entire village.

5. Identifying Neo-Endogenous Elements and Mechanisms of Building Rural Resilience

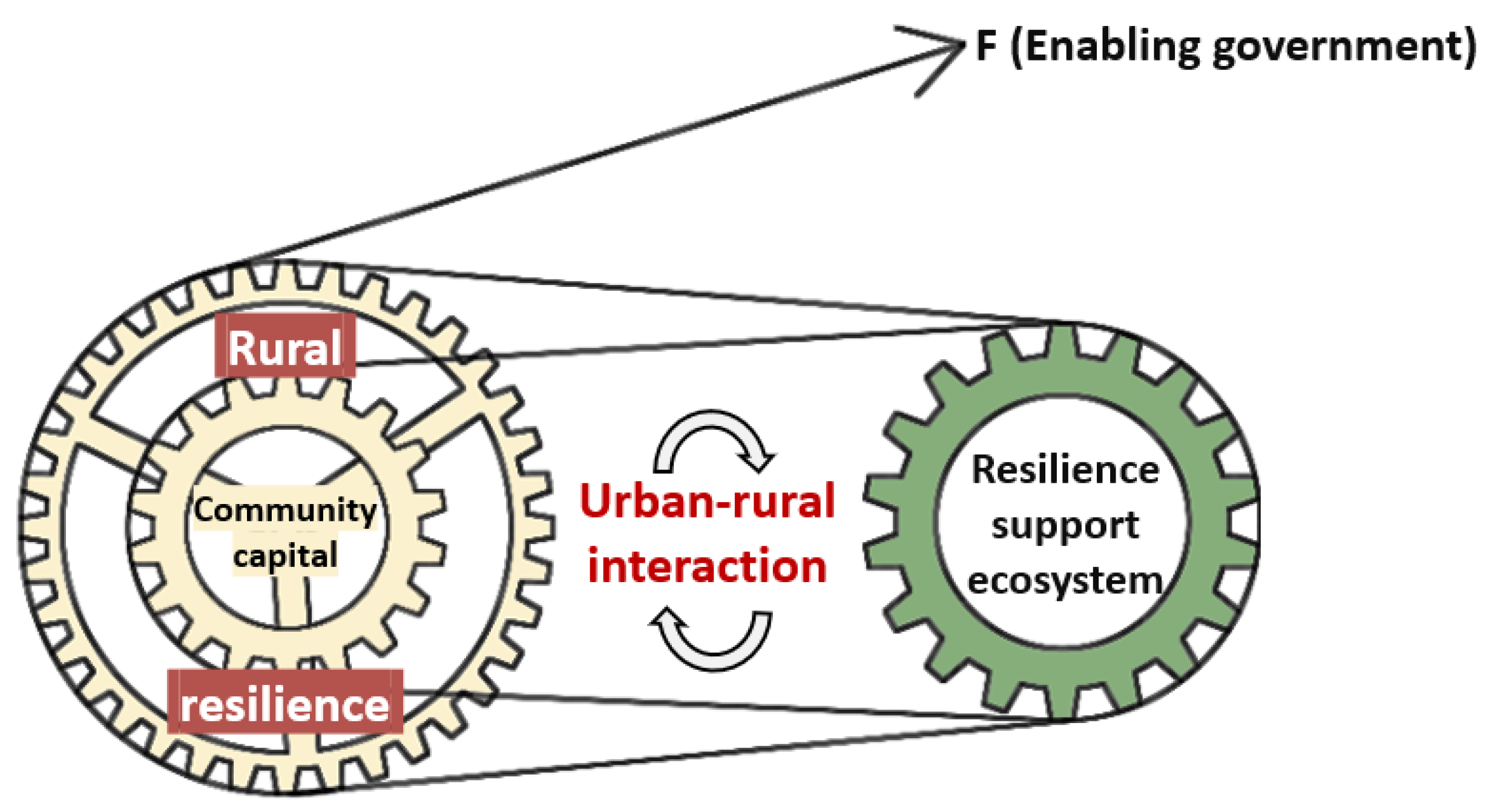

Furthermore, we employ a sports biomechanics perspective to analyze the relationship between external forces and rural resilience. A foundational axiom of this approach posits that, in the absence of external forces, the internal components of a system tend to maintain equilibrium. Under such conditions, endogenous forces alone are insufficient to induce transformative changes in the system’s dynamics. This phenomenon corresponds to a state of low- equilibrium, which mirrors the developmental trajectory of Jianta Village prior to 2016. To delve deeper, we seek to clarify that the intervention of external forces does not invariably result in a state of high-equilibrium rural resilience. Rather, it may hinge on the establishment of a resilience support ecosystem—a deeper insight illuminated by the case analysis. Building on this understanding, we propose a novel model (

Figure 4) to elucidate the core elements and crucial mechanisms for building rural resilience.

5.1. Neo-Endogenous Core Elements and Their Interrelationships

Figure 4 illustrates the new framework for rural resilience building under the theory of Endogenous Development. Firstly, community capital constitutes the endogenous element of rural resilience. Effective and sustainable rural resilience enhancement can only be achieved by tapping into local resource endowments, respecting local knowledge, and activating community capital linked to economic, social, cultural, ecological, and political dimensions. This approach helps avoid the zero-sum game of rural resilience across different dimensions, which could arise from neglecting local characteristics and the resulting loss of comparative advantages. In this sense, the process of rural resilience building is synonymous with the enhancement of community capital, and the degree of coupling between the two determines the equilibrium level of rural resilience.

Secondly, the enhancement of community capital relies on external support. Under initial conditions, rural resilience is in a low-equilibrium state, where community capital are mostly dormant, depleted, or eroded. There is a strong self-locking and internal constraint, making it difficult for the community to activate its capital on its own. Therefore, external support is needed to activate community capital and drive its reproduction, which in turn pushes the rural resilience equilibrium point upward. In this sense, the internal community capital that building rural resilience requires external support to break the self-locking and internal constraints of the rural community.

Finally, the key to activating endogenous community capital through external support lies in constructing a resilience support ecosystem, rather than directly intervening in the rural resilience building process. External support, particularly government intervention, may lead to failure or unsustainability in the rural resilience enhancement process if local characteristics are overlooked, a limitation already exposed in past exogenous development models. However, the neo-endogenous model only points out the joint action of local and extra-local resources to activate endogenous community endowment, without addressing the deeper relational mechanisms between the two. This study demonstrates that the interaction between extra-local and local resources may require the enhancement of a resilience-supporting system, thus providing a further supplement to the theory of New Endogenous Development.

5.2. Crucial Mechanisms of Building Rural Resilience

Furthermore, we aim to further elaborate on the critical role of an empowering government in rural resilience building and the mechanisms through which it operates. In the framework of neo-endogenous model, the role of the government is obscured, stemming from the discourse and political propositions of neoliberalism, which implicitly assume government failure and advocate for government retreat. While this may be applicable in certain fields within developed Western countries, it is difficult to believe that rural communities, particularly those in underdeveloped countries with weak institutional environments, inherently possess a strong resource attraction capacity and can secure top-down support through bottom-up efforts. What we seek to clarify is that the strong resource absorption capacity of rural communities needs to be nurtured, and the government plays an indispensable role in this process.

Firstly, the most essential characteristic that enables rural resilience to be maintained is the ability to absorb resources effectively, which has been fully explained in

Section 4. Only with this capacity can rural resilience avoid a complete collapse after the withdrawal of institutional interventions. Therefore, providing external support is merely the starting point for rural resilience building. The ultimate goal is to use this external support to help the community develop a strong resource absorption capacity, which becomes the core mechanism of rural resilience enhancement, rather than simply bundling external resources into an exogenous resource set. While external support may show a chain effect of community capital enhancement in the short term, it is unconvincing to consider this as a high-equilibrium of rural resilience. After all, such rigid resource sets are vulnerable to systemic collapse, when external support withdraws due to changes in the institutional environment.

Second, a strong resource absorption capacity relies on the enabling government’s role. However, the point is not to directly intervene in building rural resilience and community capital enhancement but to create a resilience support ecosystem (including introducing specialized social organizations through institutional design), fostering an external environment for community capital reproduction. In this process, it generates the multi-scalar networks and neo-endogenous development approach necessary for high-equilibrium of rural resilience, thereby forming a self-reinforcing mechanism between rural resilience building and the support ecosystem. As shown in

Figure 4, once the enabling government successfully creates a resilience support ecosystem, even if it withdraws, the self-reinforcing mechanism continues to operate due to the internal resource absorption capacity.

Third, the resilience support ecosystem is a social support space that is relatively independent yet closely interacts with the rural resilience system. This support space is triggered by the government and initially characterized by top-down, vertical integration, binding a comprehensive resource set covering policies, markets, society, and other dimensions for building rural resilience through institutional design. It is dynamic, not static, and through frequent urban–rural interactions and bidirectional interactions with the rural system, it fundamentally changes the village’s subordinate position. In this process, it constructs a mechanism for the transformation from vertical to horizontal networks, generating a resilience-supporting ecosystem, a higher-order form relative to the institutional support space.

6. Discussion

This study provides a detailed account of building rural resilience practices in a village in Western China, revealing the process and mechanisms behind its transformation. It also attempts to engage in a dialogue with the neo-endogenous development theory, which originated from the EU LEADER program. This paradigm emphasizes the synergy between local initiatives and extra-local resources, positing that development is most sustainable when it leverages local assets while strategically engaging with external networks and knowledge [

22,

23]. A recurring theme in this literature, however, is the implicit prerequisite of a certain level of pre-existing social capital and community agency—often described as a ‘close-knit society’. This article summarizes the longitudinal process model of rural resilience building in the case village (

Figure 2) and further proposes a mechanism for the neo-endogenous elements and rural resilience enhancement. Essentially, it presents an analytical framework for building rural resilience through the neo-endogenous development approach (

Figure 4), contributing to the existing literature on both rural resilience and neo-endogenous development theory.

On the one hand, this study expands upon the existing research on rural resilience that focuses on community capital. The application of the community capital framework to analyze rural resilience has gained increasing attention in academic circles [

21,

33,

34]. Some scholars argue that strengthening different aspects of community capital is a zero-sum game [

20], while others suggest there is an “upward spiral” through human capital enhancement [

19] and “chain effect” through economic investment [

21]. This paper reveals that the two outcomes mentioned above may occur at different stages within the same village. The fundamental cause lies in the underlying differences in development approaches, a topic that has not been thoroughly explored in existing research. Instead, previous studies have focused on analyzing the dynamics of community capital itself. This study reveals that the neo-endogenous development approach can generate a chain effect of community capital enhancement. Furthermore, it proposes a potential pathway for community capital interaction, whereby the mutual reinforcement mechanism between cultural capital and social capital, facilitated by public folkloric activities, creates a socio-cultural support space within the community. This, in turn, drives the transformation of village industries and the provision of public services, thereby promoting the reproduction of economic, ecological, and political capital. The interactions between different types of capital have also been overlooked in existing research, and we anticipate that future studies will explore other interaction models. Finally, this paper constructs a novel framework for analyzing rural resilience building. It breaks away from the traditional focus on communities as the analytical unit and community capital as the research focal point, introducing a systemic perspective that incorporates resilience ecosystems, their components, and the role of government. This approach helps accelerate the theoretical development of resilience-building practices, which, at present, exhibit fragmented characteristics.

On the other hand, this study goes beyond the existing analysis of the networking paradigm of neo-endogenous model, which typically focuses on how social organizations activate communities. These studies primarily emphasize the critical role of social capital elements such as trust, reciprocity, and participation, with the implicit assumption that a “close-knit society” exists [

35,

36]. Previous studies seem to have overlooked the foundational conditions for the realization of neo-endogenous development, as in the absence of a “close-knit society”, weak social ties hinder villagers from spontaneously forming cooperation, leading public affairs to fall into the ‘free-rider’ dilemma [

37,

38]. This study presents a governance-driven resilience framework through an enabling government to generate the resilient support ecosystem, highlighting that in a weak institutional context, the government may intervene to bundle a set of resources aimed at providing external support to the community. This could involve introducing social organizations through (1) third-sector partnership curation via service procurement mechanisms, and (2) addressing community human capital constraints through embedding village-stationed officials. This approach is consistent with McAreavey’s (2022) research [

33], which discusses how, with deliberative state action, multiple local institutions work together to enable the rural community to “bounce forward.” Furthermore, the study highlights that institutional support mechanisms demonstrate mutually reinforcing effects through their interactions with community capital. This co-evolutionary process effectively enhances rural communities’ resource absorption capacity, driving external support systems to evolve into a higher-level, community-oriented resilience support ecosystem. It is also important to clarify that the model emerging from this case is characterized by three distinctive features: (1) its phased nature, evolving from external initiation to community-led self-reinforcement; (2) its reliance on hybrid governance, blending state-led institutional arrangements with community-based action; and (3) its dynamic interface between external resources and local capital, which continuously co-adapts rather than remaining static. It is crucial to emphasize that rural resilience building through the neo-endogenous approach manifests as a progressive three-phase model: “external support—community capital activation—self-reinforcement of rural resilience.” Within this framework, the resilience-oriented support ecosystem essentially constitutes a dynamic interface between external support and community capital. Rather than being static, this interface undergoes continuous reshaping through their mutual interactions. The findings accelerate the dialogue between China’s practice and neo-endogenous development theory, expanding the academic understanding of the interaction between local and extra-local resources in neo-endogenous model.

Nevertheless, a case study cannot provide an overview of building rural resilience or community capital enhancement. This study presents only one development path. While we have endeavored to uncover the theoretical logic and mechanisms underlying the phenomena in order to reveal their essence and inspire further extensions, the single-case study method inherently lacks generalizability. As a result, we face significant limitations in exploring possibilities beyond the case itself. For instance, we cannot address how the various aspects of community capital interact in the process of enhancing rural resilience through economic investment, as demonstrated in other studies. Additionally, we cannot ascertain whether a chain effect, driven by the mutual reinforcement between economic and social capital, exists to enhance community capital, even though such a mechanism is theoretically plausible.

While the proposed framework offers a viable path for rural resilience building, its applicability depends on several foundational conditions. First, the presence of external supportive resources—whether through governmental policies, third-sector partnerships, or market linkages—is essential to initiate the process in communities with limited endogenous capacities. Second, the existence of localized organizational carriers—such as community cooperatives, grassroots NGOs, or village committees—acts as a critical intermediary to channel external resources and mobilize local participation. Third, a minimal level of actionable social or cultural capital is required, even if initially weak, to serve as the entry point for activating broader community engagement. These conditions collectively define the scope of transferability for our model, particularly in contexts characterized by institutional thinness or early-stage rural decline. The framework may hold particular relevance for regions where the state maintains a proactive role in facilitating—rather than fully directing—rural development, and where community agency can be gradually cultivated through structured yet adaptive interventions.

7. Conclusions

This study decodes China’s rural resilience building practice and clarifies its historical context and processes, thereby assisting scholars in better grasping key issues in rural resilience building within the Chinese context, which differs from practices in Western countries. By utilizing the practices of a village in western China as a case study and employing a longitudinal case analysis, this research focuses on process theorization rather than factor theorization found in existing studies. It reveals the processes and mechanisms of constructing rural resilience through neo-endogenous approach and provides an analytical framework for rural resilience building. The study finds that: (1) The case village has undergone a transition from a low-equilibrium to a high-equilibrium state of rural resilience, achieving a chain effect of community capital enhancement and an overflow effect of rural resilience building. This process demonstrates multiple interactions between external forces, such as government, social organizations, and urban residents, and the rural community, exhibiting a strong dependence on community capital. Moreover, the economic, social, cultural, ecological, and political dimensions of community capital are not independent of each other. The establishment of interactive and reinforcement mechanisms among these dimensions is key to achieving a high-equilibrium state of rural resilience. (2) The rural resilience enhancement in the case village aligns with the new endogenous development approach, where community capital constitutes its endogenous resources, while external support is a resource pool encompassing policies, markets, and society. The involvement of external support in building rural resilience focuses on building a multi-scale resilience support ecosystem. Specifically, this process can be divided into two phases: first, an enabling government uses institutional interventions to bundle a comprehensive resource set to break through the community’s inherent constraints and self-locking, thereby enhancing community capital; second, as the community capital continuously interacts with external resources, particularly through urban–rural interaction, the community generates strong resource absorption capacity, fostering a dynamic and extensible resilience support system, which ultimately contributes to the high-equilibrium state of rural resilience. (3) The framework for analyzing rural resilience enhancement, innovatively proposed by integrating the neo-endogenous approach, surpasses the traditional focus on communities as the analytical unit and community capital as the research focus. It effectively introduces elements such as government, resilience support ecosystems (involving policy, society, market, etc.), and urban-rural interaction. This not only accelerates the theoretical development of rural resilience research but also provides comprehensive strategies for resilience building practices.