Effective Long-Term Strategies for Reducing Cyperus esculentus Tuber Banks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Concept

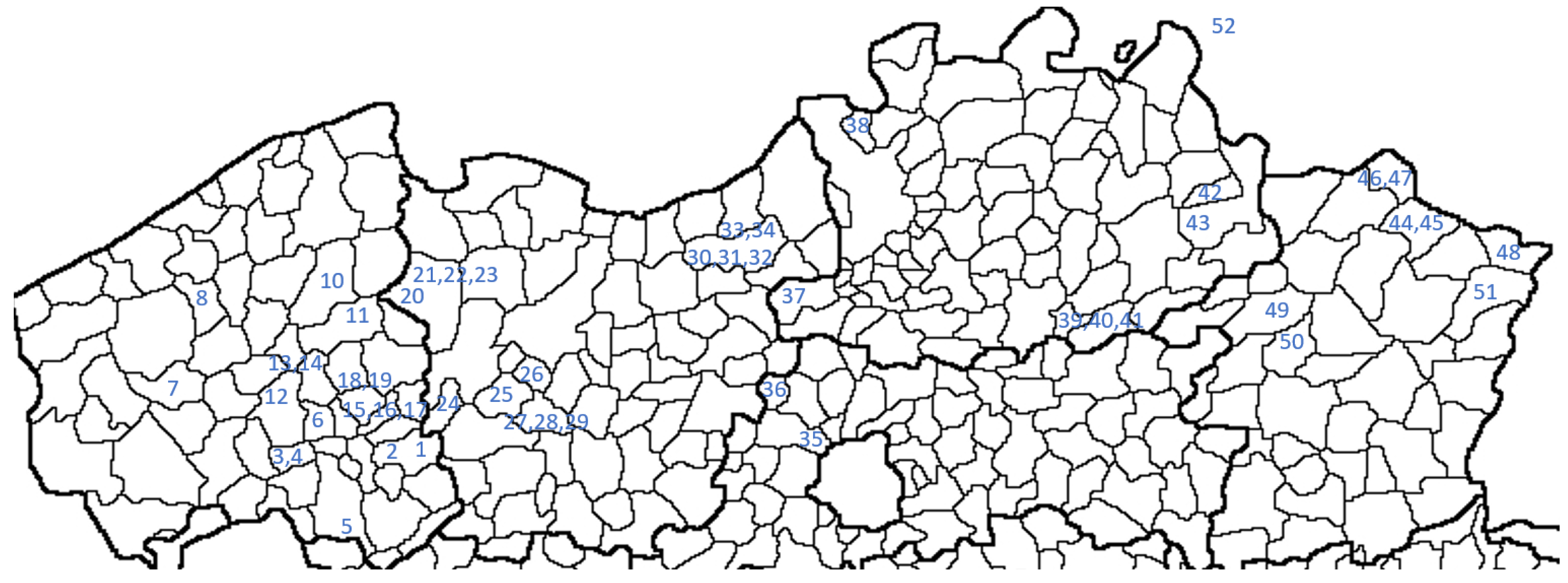

2.2. Choice of Experimental Fields

2.3. Soil Sampling

2.4. Tuber Extraction and Viability Assessment

2.4.1. Tuber Extraction

2.4.2. Viability Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Comparison of Tuber Banks Among Years

2.5.2. Boxplots of Annual Tuber Bank Evolutions

2.6. Farmer Interviews

- Cultivated crop: seed or plant density, sowing or planting date, harvest date;

- Organic fertilization: type, dose, timing;

- Soil cultivation: type (inversion/non-inversion), timing;

- Weed management: type (chemical, mechanical, thermal, others), timing, dose (if chemical), driving speed (if mechanical or thermal), crop stage;

- Cover crops: species, seed density, sowing date.

2.7. Climatic Conditions

3. Results

3.1. Tuber Bank Dynamics over Time: A Three-Year Analysis

3.1.1. General Overview

3.1.2. Fields with Complete Tuber Bank Eradication

- In 2022, a single post-emergence (POST) application was made at the 5–6 leaf stage, consisting of 80 g mesotrione, 750 g pethoxamid, 25 g tritosulfuron, 125 g dicamba, and 20 g nicosulfuron.

- In 2023, two POST applications were carried out. The first, at the 3–4 leaf stage, included 99 g mesotrione, 26 g tembotrione, 480 g pyridate, 200 g nicosulfuron, and 900 g dimethenamid-P. The second, at the 6–7 leaf stage, consisted of 36 g mesotrione and 240 g pyridate.

- In 2024, two POST applications were again applied. The first, at the 3–4 leaf stage, consisted of 900 g dimethenamid-P, 26 g tembotrione, 54 g mesotrione, 180 g pyridate, and 20 g nicosulfuron. The second, at the 6–7 leaf stage, included 216 g dimethenamid-P, 99 g mesotrione, and 510 g pyridate.

3.1.3. Characterization of the Top 10 Fields

3.1.4. Fields with Remarkable Results

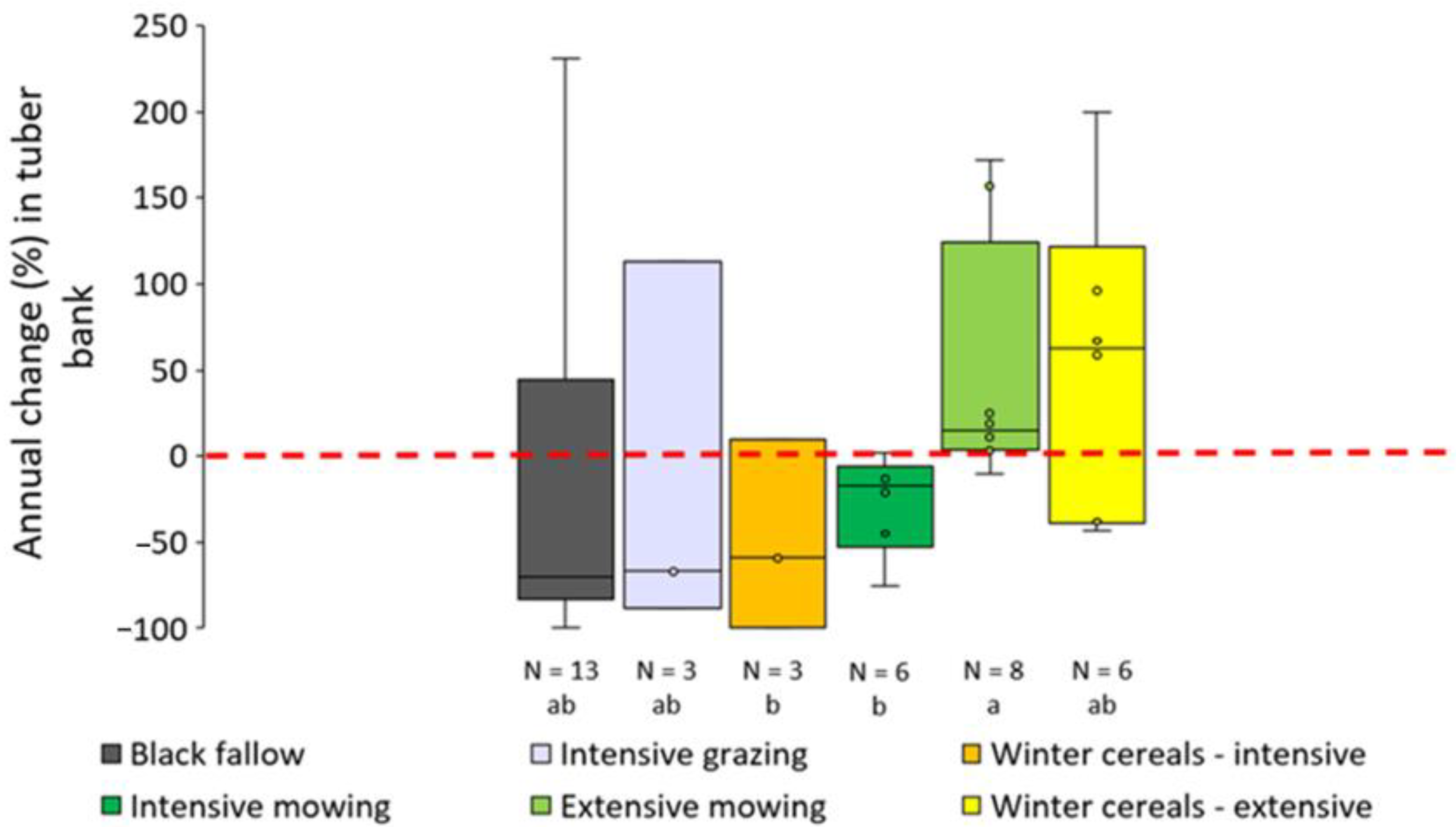

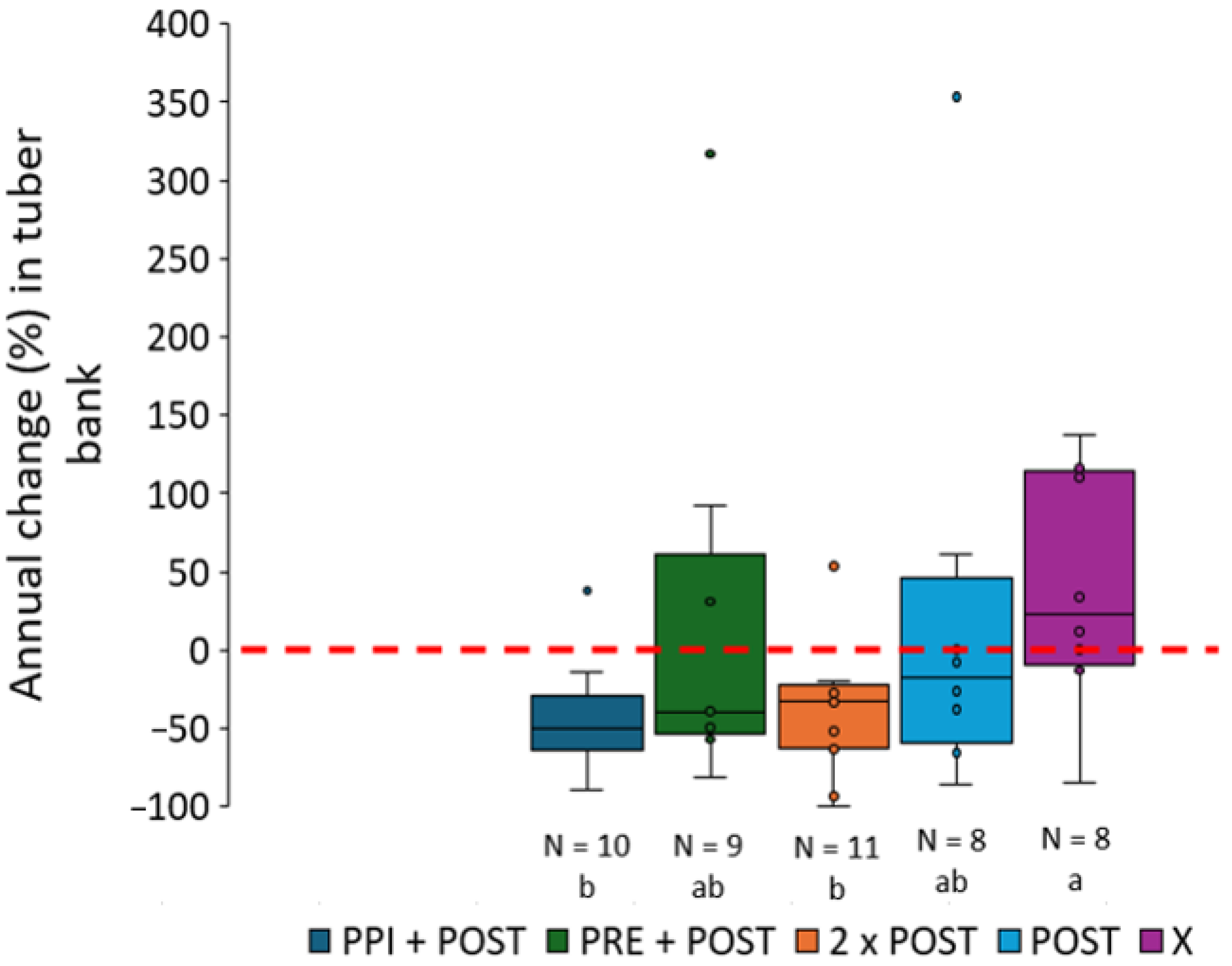

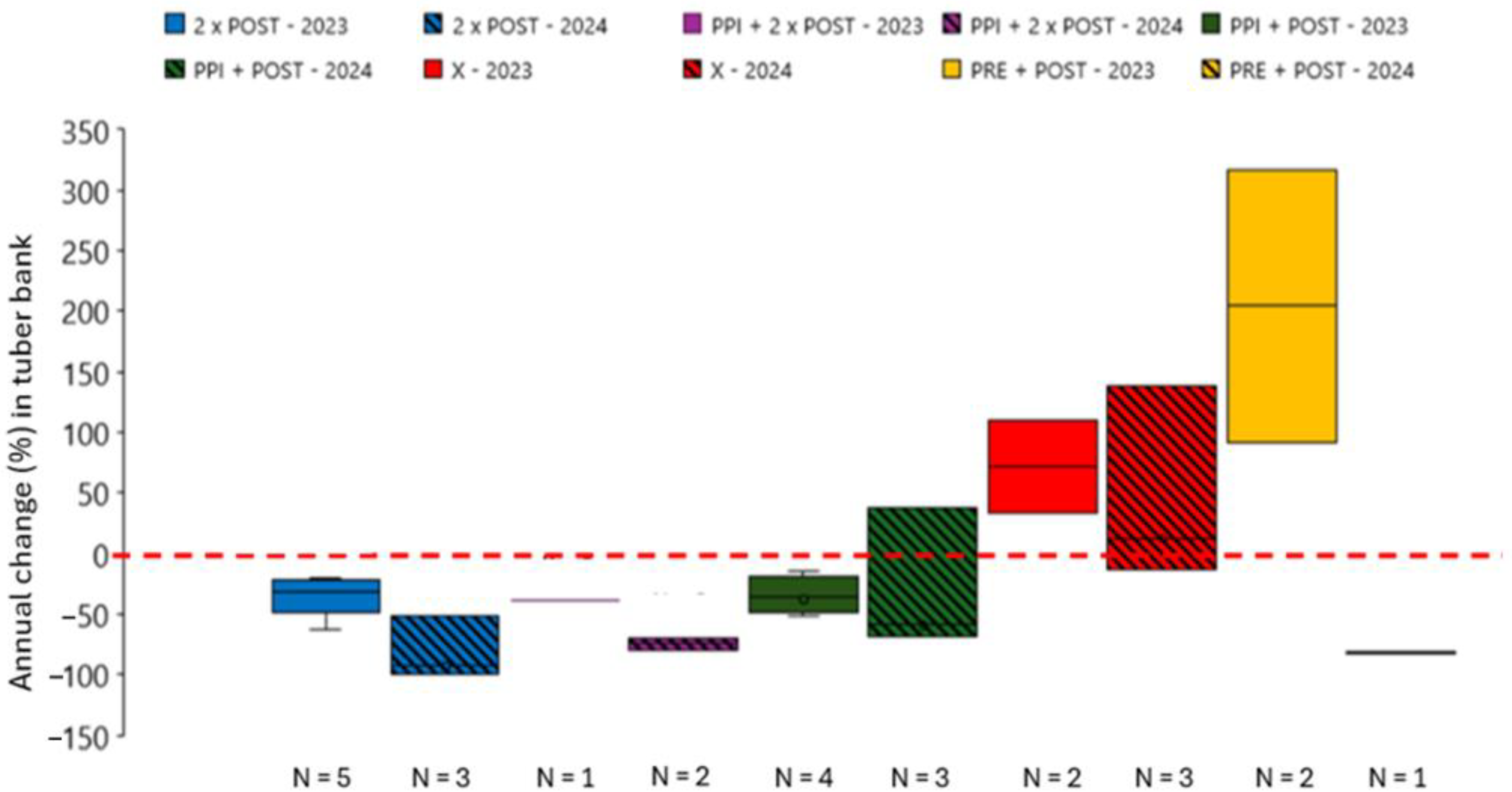

3.2. Boxplots of Annual Tuber Bank Reductions

3.2.1. Non-Maize Fields

3.2.2. Maize Fields: Comparison of Chemical Strategies

3.2.3. Maize Fields: Comparison of Years

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Number | Name | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Change (%) 2024 vs. 2021 | Rank | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTB | SE | Sig | MTB | SE | Sig | MTB | SE | Sig | MTB | SE | Sig | ||||

| 1 | Waregem | 1790 | 450.7 | a | 607 | 105.7 | a | 398 | 123.7 | a | 30 | 9.9 | b | −98.3 * | 4 |

| 2 | Desselgem | 587 | 151.0 | a | 90 | 44.1 | b | 70 | 25.0 | b | 288 | 44.1 | ab | −50.8 | 18 |

| 3 | Lendelede 1 | 557 | 116.0 | a | 617 | 61.9 | a | 169 | 73.3 | b | 766 | 49.7 | a | +37.5 | 37 |

| 4 | Lendelede 2 | 40 | 28.1 | a | 40 | 23.0 | a | 99 | 34.5 | a | 318 | 131.0 | a | +700.0 | 51 |

| 5 | Aalbeke | 279 | 39.8 | a | 219 | 50.1 | a | 149 | 41.0 | a | 109 | 37.7 | a | −60.7 | 17 |

| 6 | Izegem | 1651 | 481.5 | a | 1601 | 280.1 | a | 2139 | 317.2 | a | 885 | 211.4 | a | −46.4 | 19 |

| 7 | Houthulst | 269 | 19.0 | ab | 159 | 32.5 | ab | 527 | 196.5 | a | 50 | 29.8 | b | −81.5 | 11 |

| 8 | Koekelare | 1552 | 593.1 | a | 736 | 41.4 | a | 796 | 134.9 | a | 388 | 212.6 | a | −75.0 | 13 |

| 9 | Aartrijke | 637 | 90.4 | a | 209 | 71.5 | b | 129 | 59.4 | b | 209 | 41.0 | b | −67.2 * | 15 |

| 10 | Hertsberge | 239 | 70.8 | a | 129 | 19.0 | a | 249 | 61.6 | a | 80 | 53.9 | a | −66.7 | 16 |

| 11 | Wingene | 1263 | 127.3 | a | 666 | 95.2 | b | 318 | 23.0 | c | 60 | 25.7 | c | −95.3 * | 6 |

| 12 | Roeselare-Beveren | 3034 | 557.1 | a | 1900 | 260.6 | ab | 1403 | 397.4 | b | 1910 | 77.9 | ab | −37.0 | 23 |

| 13 | Ardooie 1 | 597 | 158.3 | b | 209 | 29.8 | b | 1174 | 151.1 | a | 477 | 23.0 | b | −20.0 | 27 |

| 14 | Ardooie 2 | 1750 | 167.2 | a | 1512 | 344.2 | a | 2397 | 273.4 | a | 1522 | 234.5 | a | −13.0 | 30 |

| 15 | Oostrozebeke 1 | 557 | 142.5 | ab | 239 | 56.3 | ab | 90 | 29.8 | b | 766 | 263.1 | a | +37.5 | 38 |

| 16 | Oostrozebeke 2 | 279 | 16.2 | a | 279 | 105.3 | a | 239 | 43.0 | a | 189 | 61.6 | a | −32.1 | 24 |

| 17 | Ginste | 418 | 108.4 | a | 60 | 25.7 | b | 40 | 16.2 | b | 0 | 0.0 | b | −100.0 * | 1 |

| 18 | Meulebeke 1 | 557 | 58.6 | a | 30 | 19.0 | b | 497 | 11.5 | a | 438 | 151.5 | a | −21.4 | 26 |

| 19 | Meulebeke 2 | 1035 | 86.0 | b | 706 | 165.2 | b | 776 | 156.2 | b | 1850 | 193.9 | a | +78.8 * | 40 |

| 20 | Maria-Aalter | 4009 | 349.3 | a | 597 | 117.1 | b | 657 | 147.5 | b | 40 | 28.1 | b | −99.0 * | 3 |

| 21 | Knesselare 1 | 1790 | 411.9 | a | 1293 | 328.7 | ab | 1174 | 224.2 | ab | 288 | 65.7 | b | −83.9 * | 10 |

| 22 | Knesselare 2 | 1403 | 352.7 | a | 1442 | 183.3 | a | 1253 | 413.7 | a | 1273 | 273.3 | a | −9.2 | 31 |

| 23 | Knesselare 3 | 368 | 41.0 | b | 796 | 382.8 | ab | 1724 | 351.0 | a | 199 | 132.0 | b | −45.9 | 20 |

| 24 | Zulte | 378 | 115.4 | b | 1383 | 242.2 | b | 4775 | 400.5 | a | 5968 | 739.4 | a | +1478.9 * | 52 |

| 25 | Nazareth | 1074 | 281.8 | ab | 408 | 75.1 | b | 1621 | 75.1 | a | 1413 | 376.2 | ab | +31.5 | 35 |

| 26 | Deurle | 1542 | 303.6 | ab | 1044 | 198.5 | b | 2188 | 331.7 | ab | 2447 | 260.2 | a | +58.7 | 39 |

| 27 | Gavere 1 | 428 | 222.4 | a | 0 | 0.0 | a | 607 | 238.4 | a | 129 | 80.2 | a | −69.8 | 14 |

| 28 | Gavere 2 | 20 | 11.5 | a | 80 | 48.7 | a | 109 | 54.8 | a | 99 | 41.4 | a | +400.0 | 49 |

| 29 | Gavere 3 | 60 | 25.7 | a | 99 | 11.5 | a | 129 | 41.0 | a | 179 | 92.6 | a | +200.0 | 47 |

| 30 | Sinaai | 1363 | 19.0 | ab | 935 | 173.8 | b | 1960 | 422.5 | a | 826 | 160.3 | ab | −39.4 | 21 |

| 31 | Belsele | 358 | 134.9 | a | 149 | 41.0 | a | 448 | 179.0 | a | 80 | 43.0 | a | −77.8 | 12 |

| 32 | Sint-Niklaas | 428 | 203.1 | b | 507 | 136.3 | b | 1303 | 219.4 | ab | 2716 | 753.1 | a | +534.9 * | 50 |

| 33 | Nieuwkerken-Waas 1 | 239 | 79.6 | a | 80 | 16.2 | ab | 169 | 34.0 | ab | 20 | 11.5 | b | −91.7 * | 7 |

| 34 | Nieuwkerken-waas 2 | 109 | 59.4 | b | 169 | 57.1 | b | 438 | 62.9 | a | 239 | 67.0 | ab | +118.2 | 42 |

| 35 | Asse | 249 | 71.5 | b | 119 | 58.6 | b | 497 | 95.4 | ab | 448 | 54.8 | a | +80.0 * | 41 |

| 36 | Opwijk | 487 | 188.3 | a | 448 | 95.2 | a | 875 | 136.9 | a | 497 | 118.8 | a | +2.0 | 33 |

| 37 | Bornem | 627 | 99.3 | a | 90 | 25.0 | bc | 288 | 78.5 | b | 0 | 0.0 | c | −100.0 * | 2 |

| 38 | Stabroek | 438 | 128.9 | a | 487 | 116.4 | a | 279 | 62.9 | a | 448 | 169.9 | a | +2.3 | 34 |

| 39 | Herselt 1 | 637 | 104.0 | ab | 388 | 108.2 | b | 1144 | 173.7 | a | 846 | 163.5 | ab | +32.8 | 36 |

| 40 | Herselt 2 | 408 | 183.3 | b | 269 | 136.3 | b | 746 | 159.5 | ab | 1064 | 137.2 | a | +161.0 * | 45 |

| 41 | Herselt 3 | 657 | 61.9 | c | 1164 | 133.3 | bc | 2208 | 318.5 | a | 1920 | 184.8 | ab | +192.4 * | 46 |

| 42 | Retie | 686 | 123.0 | b | 955 | 200.9 | b | 1025 | 281.5 | b | 2785 | 662.0 | a | +305.8 * | 48 |

| 43 | Mol | 547 | 207.6 | a | 398 | 106.5 | a | 318 | 81.2 | a | 448 | 9.9 | a | −18.2 | 28 |

| 44 | Bocholt 1 | 189 | 99.3 | a | 99 | 41.4 | a | 259 | 94.0 | a | 159 | 58.6 | a | −15.8 | 29 |

| 45 | Bocholt 2 | 855 | 211.5 | b | 438 | 188.7 | b | 1711 | 218.5 | a | 537 | 122.1 | ab | −37.2 | 22 |

| 46 | Hamont-Achel 1 | 348 | 57.1 | a | 159 | 28.1 | b | 99 | 52.6 | b | 30 | 19.0 | b | −91.4 * | 8 |

| 47 | Hamont-Achel 2 | 537 | 83.6 | a | 229 | 25.0 | a | 428 | 107.0 | a | 398 | 98.8 | a | −25.9 | 25 |

| 48 | Kinrooi | 2954 | 258.1 | a | 577 | 197.9 | b | 199 | 70.8 | b | 60 | 34.5 | b | −98.0 * | 5 |

| 49 | Beringen | 1492 | 361.2 | b | 766 | 89.5 | b | 2795 | 301.9 | a | 3432 | 197.2 | a | +130.0 * | 44 |

| 50 | Heusden-Zolder | 408 | 105.7 | b | 537 | 95.4 | ab | 249 | 81.8 | b | 895 | 134.4 | a | +119.5 * | 43 |

| 51 | Maaseik | 179 | 50.1 | a | 20 | 11.5 | b | 408 | 163.5 | a | 169 | 52.3 | ab | −5.6 | 32 |

| 52 | Middelbeers | 1253 | 61.9 | a | 408 | 329.5 | b | 90 | 52.3 | b | 159 | 81.2 | b | −87.3 * | 9 |

References

- Weed Science Society of America. WSSA Survey Ranks Most Common and Most Troublesome Weeds in Broadleaf Crops, Fruits and Vegetables. Available online: https://wssa.net/2017/05/wssa-survey-ranks-most-common-and-most-troublesome-weeds-in-broadleaf-crops-fruits-and-vegetables/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Stoller, E.W.; Wax, L.M.; Slife, F.W. Yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) competition and control in corn (Zea mays). Weed Sci. 1979, 27, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.; Wirth, J. Souchet comestible (Cyperus esculentus L.): Situation actuelle en Suisse. Rech. Agron. Suisse 2016, 4, 460–467. [Google Scholar]

- Stoller, E.W. Yellow Nut Sedge: A Menace in the Corn Belt (No. 1642); US Department of Agriculture; Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- De Cauwer, B.; De Ryck, S.; Claerhout, S.; Biesemans, N.; Reheul, D. Differences in growth and herbicide sensitivity among Cyperus esculentus clones found in Belgian maize fields. Weed Res. 2017, 57, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeyere, A. Praktijkgids Gewasbescherming. Module IPM Akkerbouw. Departement Landbouw en Visserij. Available online: https://www.vlaanderen.be/publicaties/praktijkgids-gewasbescherming-module-ipm-akkerbouw (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- De Ryck, S.; Steylaerts, E.; Fort, B.; Reheul, D.; De Cauwer, B. In situ seedling establishment and performance of Cyperus esculentus seedlings. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ryck, S.; Reheul, D.; De Cauwer, B. Impacts of herbicide sequences and vertical tuber distribution on the chemical control of yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus L.). Weed Res. 2021, 61, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, L.A.P.; Groeneveld, R.M.W.; Habekotte, B.; Van Oene, H. Reduction of growth and reproduction of Cyperus esculentus by specific crops. Weed Res. 1991, 31, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, P.E.; Thullen, R.J. Influence of yellow nutsedge competition on furrow-irrigated cotton. Weed Sci. 1975, 23, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ryck, S.; Reheul, D.; De Cauwer, B. Impact of regular mowing, mowing height, and grass competition on tuber number and tuber size of yellow nutsedge clonal populations (Cyperus esculentus L.). Weed Res. 2023, 63, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerlin, J.R.; Coble, H.D.; Yelverton, F.H. Effect of mowing on perennial sedges. Weed Sci. 2000, 48, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phatak, S.C.; Sumner, D.R.; Wells, H.D.; Bell, D.K.; Glaze, N.C. Biological control of yellow nutsedge with the indigenous rust fungus Puccinia canaliculata. Science 1983, 219, 1446–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascard, J.; Hatcher, P.E.; Melander, B.; Upadhyaya, M.K. Thermal Weed Control. In Non-Chemical Weed Management. Principles, Concepts and Technology; Upadhyaya, M.K., Blackshaw, R.E., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 155–175. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W.C.; Davis, R.F.; Mullinix, B.G., Jr. An integrated system of summer solarization and fallow tillage for Cyperus esculentus and nematode management in the southeastern coastal plain. Crop Prot. 2007, 26, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.; Wirth, J. Implementation of control strategies against yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus L.) into practice. Jul.-Kühn-Arch. 2018, 458, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- De Ryck, S. Towards an Integrated Approach for Effective Cyperus esculentus Control. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R.P. Handbook on Tetrazolium Testing; International Seed Testing Association: Zürich, Switzerland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Grichar, W.J.; Lemon, R.G.; Brewer, K.D.; Minton, B.W. S-metolachlor compared with metolachlor on yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus L.) and peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Weed Technol. 2001, 15, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudney, D.W. Soil Moisture and Herbicides. University of California, Riverside. Available online: https://my.ucanr.edu/repository/fileaccess.cfm?article=161669&p=JVCQWS (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Grichar, W.J.; Lemon, R.G.; Sestak, D.C.; Brewer, K.D. Comparison of metolachlor and dimethenamid for yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus L.) control and peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) injury. Peanut Sci. 2000, 27, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Commission Implementing Regulation EU 2024/20 of 12 December 2023 Concerning the Non-Renewal of the Approval of the Active Substance S-Metolachlor, in Accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Amending Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011; Official Journal of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202400020 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Fytoweb. Toelatingen van Gewasbeschermingsmiddelen Raadplegen. Available online: https://fytoweb.be/nl/gewasbeschermingsmiddelen/toelatingen-van-gewasbeschermingsmiddelen-raadplegen (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Johnson, B.C.; Bryan, G.Y. Influence of temperature and relative humidity on the foliar activity of mesotrione. Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.; Yu, K.; Li, H.; Jia, S.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, T. The effect of elevating temperature on the growth and development of reproductive organs and yield of summer maize. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1783–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemens, M.M.; van der Weide, R.Y.; Runia, W.T. Biology and Control of Cyperus rotundus and Cyperus esculentus, Review of a Literature Survey; Plant Research International B.V.: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tissier, M.L.; Handrich, Y.; Robin, J.P.; Weitten, M.; Pevet, P.; Kourkgy, C.; Habold, C. How maize monoculture and increasing winter rainfall have brought the hibernating European hamster to the verge of extinction. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, M.; Wirth, J. Tackling yellow nutsedge with fallow periods and cover crops. In Proceedings of the EWRS Workshop Physical and Cultural Weed Control, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 27–29 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Matthiesen, R.L. Plant Development and Tuber Composition of Six Biotypes of Yellow Nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus L.); University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Urbana, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Sousek, M.; Reicher, Z.; Gaussoin, R. Strategies for increased yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) control in turfgrass with halosulfuron, sulfentrazone, and physical removal. Weed Technol. 2021, 35, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeester, Y. Grondverspreiding door machines. In Jaarboek 1987–1992: Verslagen van in 1987–1992 Afgesloten Onderzoekprojecten op Regionale Onderzoek Centra en het PAGV; No. 38-64; Proefstation voor de Akkerbouw en de Groenteteelt in de Vollegrond: Lelystad, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament (n.d.). Fact Sheets of the European Union: Direct Payments. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/109/direct-payments (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Agentschap Landbouw en Zeevisserij. Conditionaliteit 2023–2027. Available online: https://lv.vlaanderen.be/bedrijfsvoering/conditionaliteit-en-randvoorwaarden/conditionaliteit-2023-2027 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Vlaamse Landmaatschappij. Nieuwe Mestmaatregelen 2025. Available online: https://www.vlm.be/nl/SiteCollectionDocuments/Mestbank/Algemeen/Nieuwe_maatregelen_Glabbeek.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

| Number (Figure 2) | Name | Province | Soil Texture (Sand %, Silt %, Clay %) | Organic Matter (%) | Crop Rotation (2022/2023/2024) | Organic? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Waregem | WFL | sandy loam (63.8, 26.9, 9.3) | 1.5 | m+gt/gt+m+gt/gt+m | No |

| 2 | Desselgem | WFL | sandy loam (67.5, 24.2, 8.3) | 2.4 | m/ww+ph/cb | No |

| 3 | Lendelede 1 | WFL | sandy loam (59.5, 30.3, 10.2) | 1.5 | bf/bf/m | No |

| 4 | Lendelede 2 | WFL | sandy loam (60.8, 30.9, 8.4) | 0.9 | gt+m+gt/gt+m+gt/gt+m+gt | No |

| 5 | Aalbeke | WFL | loam (13.9, 73.0, 13.1) | 0.8 | wb+lr/m/m | No |

| 6 | Izegem | WFL | sandy loam (60.3, 30.9, 8.8) | 1.2 | p/m/o | No |

| 7 | Houthulst | WFL | sandy loam (61.1, 30.3, 8.6) | 1.3 | bf/bf/bf | No |

| 8 | Koekelare | WFL | loamy sand (92.1, 4.9, 3.0) | 3.0 | m/m/m+ww | No |

| 9 | Aartrijke | WFL | loamy sand (76.1, 17.7, 6.2) | 3.9 | sp+cb/m/sp+cb | No |

| 10 | Hertsberge | WFL | sand (73.3, 23.5, 3.1) | 1.7 | m/m+gt/gt+m | No |

| 11 | Wingene | WFL | sandy loam (77.5, 17.8, 4.8) | 1.9 | m/m/m | No |

| 12 | Roeselare-Beveren | WFL | sandy loam (61.6, 29.0, 9.3) | 2.9 | m/p/m | No |

| 13 | Ardooie 1 | WFL | sandy loam (71.3, 21.0, 7.7) | 2.2 | m/cb+ww/ww+lr | No |

| 14 | Ardooie 2 | WFL | sandy loam (67.4, 24.8, 7.8) | 2.9 | p/ww/wb+m | No |

| 15 | Oostrozebeke 1 | WFL | loamy sand (72.4, 20.4, 7.2) | 3.2 | gt+m+gt/gt+m/p | No |

| 16 | Oostrozebeke 2 | WFL | loamy sand (79.6, 15.2, 5.2) | 3.7 | gt+m+gt/gt+m+gt/gt | No |

| 17 | Ginste | WFL | loamy sand (83.5, 11.5, 5.0) | 3.2 | gt+m+gt/gt+m+gt/gt+m+gt | No |

| 18 | Meulebeke 1 | WFL | sandy loam (69.5, 24.8, 5.7) | 3.7 | bs/p/bs | No |

| 19 | Meulebeke 2 | WFL | loamy sand (71.1, 22.3, 6.6) | 2.8 | m+ww/ww+gt/gt+m | No |

| 20 | Maria-Aalter | EFL | sand (88.5, 8.8, 2.8) | 2.1 | sp+m/sp+m/sp+m | No |

| 21 | Knesselare 1 | EFL | loamy sand (72.3, 20.6, 7.11) | 3.0 | mc+gt/gt/gt | No |

| 22 | Knesselare 2 | EFL | loamy sand (72.4, 20.0, 7.6) | 2.6 | gt/gt/gt | No |

| 23 | Knesselare 3 | EFL | loamy sand (91.1, 6.7, 2.2) | 1.7 | m+mc/mc+gt/gt | No |

| 24 | Zulte | EFL | sandy loam (79.0, 15.8, 5.2) | 3.5 | m+mc/mc+gt/gt | Yes |

| 25 | Nazareth | EFL | sand (93.3, 4.3, 2.4) | 3.2 | m+ry/ry+m/m+gt | No |

| 26 | Deurle | EFL | loamy sand (84.7, 11.0, 4.3) | 3.9 | m+ry/ry+m/m+gt | No |

| 27 | Gavere 1 | EFL | sandy loam (65.4, 29.2, 5.4) | 2.1 | wb+lr/m/m | No |

| 28 | Gavere 2 | EFL | sandy loam (80.1, 15.9, 4.0) | 1.6 | ww+wb/wb/m | No |

| 29 | Gavere 3 | EFL | sandy loam (64.4, 30.2, 5.4) | 2.3 | ww/m+wb/wb+ry | No |

| 30 | Sinaai | EFL | sand (92.7, 5.3, 2.1) | 2.6 | m/m+tr/m+tr | No |

| 31 | Belsele | EFL | loamy sand (84.0, 10.2, 5.8) | 2.4 | m/wb+mc+ww/ww+fm | Yes |

| 32 | Sint-Niklaas | EFL | loamy sand (77.1, 18.2, 4.7) | 4.1 | gt/gt/gt+m | No |

| 33 | Nieuwkerken-Waas 1 | EFL | loamy sand (76.1, 17.7, 6.2) | 2.7 | gp/gp/gp | No |

| 34 | Nieuwkerken-waas 2 | EFL | sand (74.8, 20.0, 5.2) | 2.7 | m+mc/mc+gt/gt | No |

| 35 | Asse | FLBR | loam (15.5, 72.7, 11.8) | 3.4 | m/m/gt | No |

| 36 | Opwijk | FLBR | sandy loam (41.9, 49.2, 8.8) | 2.5 | m/ww+wb/wb+lr | No |

| 37 | Bornem | ANT | loamy sand (75.1, 21.8, 3.1) | 2.2 | ca+bf+ph/ca+bf+ph/ca+bf+ph | Yes |

| 38 | Stabroek | ANT | sand (84.9, 9.8, 5.3) | 5.8 | gt/gt/gt+m | No |

| 39 | Herselt 1 | ANT | loamy sand (84.2, 8.2, 7.6) | 3.7 | m/m/m | No |

| 40 | Herselt 2 | ANT | loamy sand (85.9, 12.5, 1.5) | 3.5 | m/m/fm | No |

| 41 | Herselt 3 | ANT | sand (85.4, 10.3, 4.2) | 3.5 | m/gt/fm | No |

| 42 | Retie | ANT | sand (95.5, 3.4, 1.1) | 4.2 | gt/gt/gt | No |

| 43 | Mol | ANT | sand (96.8, 2.3, 1.0) | 2.2 | m/m/gt | No |

| 44 | Bocholt 1 | LIM | loamy sand (79.7, 15.3, 5.0) | 3.2 | m/m/wb+lr | No |

| 45 | Bocholt 2 | LIM | loamy sand (87.1, 8.4, 4.6) | 3.1 | m+gt/gt+m+ry/ry+m+gt | No |

| 46 | Hamont-Achel 1 | LIM | loamy sand (90.1, 6.0, 3.9) | 2.5 | m+gt/gt+m+gt/gt+m | No |

| 47 | Hamont-Achel 2 | LIM | sand (90.0, 6.4, 4.0) | 3.0 | m+gc/gc/gc | No |

| 48 | Kinrooi | LIM | loamy sand (81.3, 14.4, 4.3) | 3.0 | bf+gt/gt+bf+gt/gt+bf+gt | No |

| 49 | Beringen | LIM | sand (91.5, 3.6, 4.9) | 4.2 | m/m/sw+lr | No |

| 50 | Heusden-Zolder | LIM | sand (83.7, 8.7, 7.6) | 4.7 | m/m/fm | No |

| 51 | Maaseik | LIM | loamy sand (67.4, 21.1, 5.5) | 3.6 | m/sb/m | No |

| 52 | Middelbeers | NBR | sand (/, /, /) | / | bf/bf/bf | No |

| Maize/Non-Maize | Strategy | Description | Applications (Year and Fields) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maize | Chemical—POST | Post-emergence treatment based on mesotrione + pyridate (+pethoxamid) | 2022: 1, 12, 17, 16, 36, 11, 25, 51, 39, 40, 47, 49, 50 2023: 1, 9, 11, 16, 10, 35 2024: 10, 51, 28, 3, 38, 11 |

| Maize | Chemical—2 × POST | Two post-emergence treatments based on mesotrione + pyridate (+pethoxamid) | 2022: 43, 35, 34 2023: 43, 15, 17, 2, 5 2024: 1, 8, 17 |

| Maize | Chemical—PPI | Preplant incorporation of S-metolachlor or dimethenamid-P | 2022: 26, 11, 25, 51 2023: 26, 25, 46, 1, 9, 11 2024: 27, 46, 10, 51, 28 |

| Maize | Chemical—PRE | Pre-emergence treatment based on dimethenamid-P or S-metolachlor | 2022: 10, 44, 39, 40, 47, 45, 49, 50 2023: 10, 35 2024: 11 |

| Maize | Chemical—X | Treatment not specifically targeting C. esculentus | 2022: 2, 4, 23 2023: 30, 6 2024: 19, 25, 26 |

| Non-maize | Black fallow | Black fallow throughout the entire growing season, with (combined) application of thermal, mechanical, or chemical methods | 2022: 37, 3, 48, 52, 7 2023: 37, 3, 7, 52 2024: 37, 48, 52, 7 |

| Non-maize | Intensive grazing | Intensive grazing by horses, possibly combined with mowing | 2022: 33 2023: 33 2024: 33 |

| Non-maize | Intensive mowing | At least 4 mowings in a well-established and fertilized grassland | 2022: 22 2023: 22, 23 2024: 16, 23, 34 |

| Non-maize | Extensive mowing | Less than 3 mowings in grassland | 2022: 38, 32, 22 2023: 32, 42 2024: 24, 42, 35 |

| Non-maize | Winter cereals—intensive | At least three measures applied between cereal harvest and 1 September, such as mechanical tools (spring tooth harrow, ploughing, etc.), glyphosate application, or establishment of a competitive cover crop. | 2022: 27 2023: 19 2024: 13 |

| Non-maize | Winter cereals—extensive | Less than 3 measures applied between cereal harvest and 1 September | 2022: 28 2023: 14, 31, 36 2024: 29, 36 |

| Parameter | Year | Winter (December–February) | Spring (March–May) | Summer (June–August) | Autumn (September–November) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmean (°C) | 2022 | 5.5 | 11.3 | 19.6 | 12.8 |

| 2023 | 5.0 | 10.2 | 18.9 | 13.4 | |

| 2024 | 6.3 | 11.6 | 18.3 | 11.8 | |

| Avg. 1991–2020 | 4.1 | 10.5 | 17.9 | 11.2 | |

| Precipitation (mm) | 2022 | 259.0 | 108.8 | 110.6 | 210.1 |

| 2023 | 214.9 | 241.6 | 279.5 | 283.7 | |

| 2024 | 310.7 | 285.2 | 323.8 | 275.9 | |

| Avg. 1991–2020 | 228.6 | 165.6 | 234.2 | 209.3 |

| Field Number | Name | 3-Year Tuber Bank Change (%) | Crop Rotation (2022/2023/2024) | Strategy Applied Against C. esculentus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | Ginste | −100.0 | gt+m+gt/gt+m+gt/gt+m+gt | Annual chemical treatments in maize |

| 37 | Bornem | −100.0 | ca+bf+ph/ca+bf+ph/ca+bf+ph | Annual mechanical black fallow |

| 20 | Maria-Aalter | −99.0 | sp+m/sp+m/sp+m | Annual chemical treatments in maize combined with cultural control in 2023 and 2024 |

| 1 | Waregem | −98.3 | m+gt/gt+m+gt/gt+m | Annual chemical treatments in maize, combined with delayed maize sowing in 2023 |

| 5 | Kinrooi | −98.0 | bf+gt/gt+bf+gt/gt+bf+gt | Annual mechanical black fallow |

| 11 | Wingene | −95.3 | m/m/m | Annual chemical treatments in maize) combined with cultural control in 2024 |

| 33 | Nieuwkerken-Waas 1 | −91.7 | gp/gp/gp | Annual intensive grazing by horses |

| 46 | Hamont-Achel 1 | −91.4 | m+gt/gt+m+gt/gt+m | Annual chemical treatments in maize combined with mechanical control in 2022 |

| 52 | Middelbeers | −87.3 | bf/bf/bf | Annual thermal black fallow |

| 21 | Knesselare 1 | −83.9 | mc+gt/gt/gt | Intensive mowing (at least 4 mowings on a well-established grassland) in 2023 and 2024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feys, J.; Wallays, F.; Callens, D.; Latré, J.; Van de Ven, G.; Clercx, S.; Palmans, S.; Vermeir, P.; Reheul, D.; De Cauwer, B. Effective Long-Term Strategies for Reducing Cyperus esculentus Tuber Banks. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2040. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15192040

Feys J, Wallays F, Callens D, Latré J, Van de Ven G, Clercx S, Palmans S, Vermeir P, Reheul D, De Cauwer B. Effective Long-Term Strategies for Reducing Cyperus esculentus Tuber Banks. Agriculture. 2025; 15(19):2040. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15192040

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeys, Jeroen, Fien Wallays, Danny Callens, Joos Latré, Gert Van de Ven, Shana Clercx, Sander Palmans, Pieter Vermeir, Dirk Reheul, and Benny De Cauwer. 2025. "Effective Long-Term Strategies for Reducing Cyperus esculentus Tuber Banks" Agriculture 15, no. 19: 2040. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15192040

APA StyleFeys, J., Wallays, F., Callens, D., Latré, J., Van de Ven, G., Clercx, S., Palmans, S., Vermeir, P., Reheul, D., & De Cauwer, B. (2025). Effective Long-Term Strategies for Reducing Cyperus esculentus Tuber Banks. Agriculture, 15(19), 2040. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15192040