Abstract

This study examined the sustainability of global table grape exports from 2020 to 2024, focusing on two key dimensions: market diversification and international competitiveness. Using data from Trade Map and applying the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) and the Revealed Comparative Advantage Normalized Index (RCAN), the research analyzed the export performance of major grape-exporting countries, including Peru, Chile, the Netherlands, Italy, the United States, South Africa, and China. The results showed significant differences in both market structure and competitive positioning. Countries like Peru and South Africa demonstrated rapid export growth and high competitiveness in certain markets, but faced elevated levels of market concentration, exposing them to external shocks. In contrast, Italy and the Netherlands maintained more diversified portfolios but showed modest competitiveness. The study concluded that no country achieved an ideal balance between diversification and competitiveness. As a result, it is recommended that governments pursue integrated trade strategies that promote geographic expansion alongside measures to enhance export competitiveness. Investments in logistics, quality certifications, and market intelligence are essential to reduce vulnerability and ensure long-term export sustainability.

1. Introduction

The wine and table grape industry holds strategic importance in international agricultural trade. In recent decades, globalization has driven the growth of the fruit and vegetable trade, including grapes, which have become a high-value key product [1]. However, this market faces challenges such as volatility, trade barriers, and logistics, which jeopardize income stability for exporting countries. Since fresh grapes are cultivated in numerous countries across several continents, their international trade represents a significant source of foreign exchange and rural employment. Studying the sustainability of these exports is crucial because excessive dependence on a few markets or products can make a country vulnerable. Therefore, market diversification is considered essential for achieving stability and reducing risks in international trade [2]. At the same time, maintaining international competitiveness—measured through revealed comparative advantage—is fundamental for a country to sustain or increase its share in an increasingly competitive global market [3,4,5]. In summary, this research is significant because it addresses how to balance specialization and diversification to ensure that a country’s grape exports remain sustainable in the long term, generating continuous economic benefits and offering better resistance to market fluctuations.

At the global level, a few countries dominate world grape exports, implying a concentration of supply. Recent studies show that around a dozen nations account for more than 85% of global grape exports. For instance, Chile has contributed in recent years approximately 16% of the world’s export volume, historically being the leading exporter from the Southern Hemisphere [6]. This concentration means that any disruption in one exporter can significantly impact global supply.

Simultaneously, demand is also concentrated in certain key markets. The United States is the largest global importer of fresh grapes, obtaining 97% of its imports from only three countries: Chile, Peru, and Mexico [7]. Similarly, the European Union concentrates the majority of its grape imports from the Southern Hemisphere. This interdependence creates vulnerabilities: exporters rely on a few major buyers, and importers depend on a few dominant suppliers.

The problematic global reality also includes rapid changes in market share due to the emergence of new competitors. In recent decades, the economic geography of the grape trade has changed significantly [8]. Traditionally, exporting countries (such as Chile, the United States, Italy, or South Africa) have experienced slower or stable growth, while emerging countries have rapidly gained market share [8]. A notable case is Peru, whose aggressive entry into the global market significantly altered market shares: in the key U.S. market, Peru went from virtually no grape exports at the beginning of the century to capturing nearly 40% of that market by 2022 [7]. This growth of new players has eroded the ground of traditional producers and intensified global competition. For example, in the U.S. market, Mexico’s share fell from 27.5% to just 6.1% between 2002 and 2022, while Peru emerged as a dominant competitor. Similar situations are observed in Europe, where South Africa faces competitive threats from Peru and Chile in its traditional markets [6].

The global landscape presents two intertwined issues: on one hand, a market and supplier concentration that calls into question the resilience of grape trade; on the other, intense competitive rivalry with marked gains and losses in market share, compelling countries to adapt swiftly or risk compromising the sustainability of their exports.

In Chile, which has long been a global leader in fresh grape exports—leveraging counter-seasonality to supply Northern Hemisphere markets—exports reach multiple destinations (United States, Europe, Asia), yet the country faces a growing relative loss of market share due to the rise in South American competitors [9]. In the U.S. market, although Chile has maintained high and relatively stable volumes (around 300,000 t annually), its share declined from ~69% to ~52% between 2002 and 2022 with the emergence of Peru as a new player [10]. This indicates that despite diversification of destinations, Chile has lost competitive ground and has been compelled to innovate (new varieties, improved logistics) to sustain its advantage.

Peru exemplifies a paradigmatic case of a successful new exporter, yet one that must address the challenge of not becoming overly dependent on a single market. Over the last decade, Peru has registered explosive growth in grape exports—compound annual growth rates exceeding 12% in both value and volume between 2013 and 2022 [1]—recently becoming the world’s largest exporter in value. This growth has been accompanied by an expansion in destination markets: on average, Peruvian firms export to 59 different countries.

Mexico is a significant table grape producer characterized by extreme market concentration: virtually all its exports are destined for the United States due to geographic proximity and trade agreements [11]. This lack of diversification represents a serious vulnerability. In terms of competitiveness, Mexico has seen its position erode in recent years. It revealed that comparative advantage index (Balassa’s RCA) fell from 2.4 in 2002 (indicating significant advantage) to just 0.3 in 2022, reflecting a loss of comparative advantage in grapes relative to other countries. Causes include logistical challenges, certification requirements, and above all, intense competition from Chile and Peru in the U.S. market [7]. The Mexican case exemplifies how an undiversified export structure and growing competitive disadvantages can lead to a drastic contraction in market share (its U.S. exports fell to almost one-tenth of their former volume). Mexico’s immediate challenge is to reverse its competitive decline through productivity improvements, expansion of exportable supply, and pursuit of new niches, or risk being completely displaced by its rivals [12].

South Africa is one of the largest exporters from the Southern Hemisphere and a traditional supplier to the EU and UK. South Africa sends nearly 75% of its grapes to the European market [13], representing limited regional diversification (dependence on Western Europe). While this orientation functioned for years due to seasonal and tariff advantages, it now constitutes a risk: Chile and Peru are also targeting Europe, threatening to displace part of South Africa’s supply. Although South Africa maintains a favorable comparative advantage in grapes (supported by rand depreciation lowering prices), its future depends on achieving greater access to markets outside the EU and diversifying its destinations [14], not only for this product but across its entire export basket in order to avoid over-concentration in a region where competitors are gaining ground [15].

Italy, Spain, and other traditional European producers: these countries are major grape producers (particularly for wine, but also table grapes in regions such as Apulia in Italy or Murcia in Spain [16]) and rank among the highest-value exporters globally. However, their revealed comparative advantage is lower than that of specialized countries, as their export economies are highly diversified in other sectors. For example, Italy and Spain primarily export grapes within the European market, facing competition from neighboring producers and higher labor costs than emerging countries [17]. Although they remain competitive in quality niches (premium varieties, organic grapes, etc.), they do not experience the same rapid growth seen in new extra-European actors. Their challenge is to remain competitive in higher value-added and quality segments, as, in terms of volume and cost, they cannot easily compete with more cost-effective emerging producers [18].

China, India, Turkey, and other Asian emerging players: China is the world’s leading grape producer (primarily for domestic consumption), and in recent years has begun exporting moderately, surprisingly ranking among the top five exporters by value [19]. However, much of that trade involves re-exports (e.g., via Hong Kong) or regional sales. Turkey and India, meanwhile, have consolidated themselves as important table grape exporters, mainly supplying Europe and Asia, respectively. India has taken advantage of counter-seasonal windows to place grapes in the EU (for example, in early spring when Northern Hemisphere supply is scarce), benefiting from favorable climatic conditions and improvements in the cold chain [20]. Turkey, neighboring the EU, has increased shipments to Eastern and Central Europe and also to Middle Eastern markets, leveraging geographic proximity. However, both face challenges in quality and standardization to compete with more technologically advanced producers. Their market diversification is moderate: Turkey concentrates much of its exports in the EU and Russia, and India in the EU and Middle East [8].

Given this problematic reality, the research question arises: How have market diversification and competitiveness developed among leading grape-exporting countries as a strategy to guarantee the sustainability of their exports?

This research is justified for several strong academic and practical reasons. First, there is a gap in the literature regarding recent global analyses combining diversification and competitiveness perspectives in the context of grape exports. Although international grape trade has gained significant economic relevance, empirical studies on this topic have traditionally been limited. Even scarcer are those that explicitly address export sustainability using quantitative indicators such as the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) for concentration and Balassa’s index for revealed comparative advantage. Therefore, this research fills a gap by offering a comprehensive analysis of the last five years worldwide—a period marked by significant market dynamics changes (e.g., Peru’s rise to global export leadership, partially displacing Chile).

Second, the research has high practical and policy relevance. The findings will provide valuable information for policymakers, agricultural associations, and exporting businesses. Identifying a country’s degree of market diversification and competitiveness in grape exports allows for informed strategic guidance. For instance, if excessive concentration in one destination is confirmed, trade promotion policies towards alternative markets could be recommended. Indeed, the Peru study identified this situation and explicitly recommended maintaining and deepening geographic diversification through policies aimed at seeking new markets and continuously monitoring concentration [1].

Likewise, if Balassa’s index reveals that a country’s comparative advantage is eroding (as occurred with Mexico), that justifies strategic interventions: investments in productivity improvements, varietal innovation, quality certifications, etc., to strengthen agricultural competitiveness and regain lost ground [7].

Furthermore, international competitiveness in agri-food products is a critical development factor, and its analysis through revealed comparative advantage provides a clear diagnosis of each country’s strengths and weaknesses. This links to efficient specialization strategies: some authors argue that specializing in high-competitiveness sectors can be economically sustainable if supported by innovation and value addition [21].

Finally, this research is justified because it offers a global and up-to-date perspective (last five years) on an internationally significant agricultural sector. The results will have a global character, comparing multiple countries, which facilitates the identification of common patterns and exceptional cases.

1.1. Literature Review

Recent literature provides important contributions that serve as background and context for the present research. A first group of studies has focused on analyzing the historical evolution of global grape trade and its competitiveness. Notably, the work of Seccia examined the global dynamics of the table grape trade between 1961 and 2011. This study revealed that international grape trade expanded enormously during those decades, driven by new exporting countries that substantially altered traditional market shares [8]. Seccia and colleagues observed that while some historical exporters (Western Europe, the U.S.) lost relative share, emerging exporters such as China, India, Turkey, and Peru showed upward trends, rapidly transforming the economic geography of the market. This study provided a valuable longitudinal perspective and methodological foundations, although its data extend only to 2011, before the recent rise in South American countries.

More recently, studies focusing on specific countries or regions have emerged, which are highly relevant to the state of the art in our research area. For instance, Montes et al. analyzed in detail the market diversification and competitiveness of Peru’s fresh grape exports (2013–2022). This quantitative study confirmed that Peru rapidly increased both the value and volume of its exports, but at the same time reported high market concentration (elevated HHI) with the United States as its main destination. They also calculated Balassa’s index for Peruvian grapes, finding that Peru maintains a solid revealed comparative advantage in this product, consistent with its growing global share. The study concludes with policy recommendations (geographic diversification, concentration monitoring, internal competition promotion), demonstrating the practical application of such analyses [1].

Another significant contribution comes from Cano-Espinosa and Méndez-León (2025) [7], who evaluated the trilateral competition between Mexico, Chile, and Peru within the U.S. market from 2002 to 2022. Their findings clearly illustrate Mexico’s loss of competitiveness and Peru’s simultaneous rise: Mexico’s share fell drastically from 27.5% to 6.1%, and its RCA dropped below unity, while Peru’s share increased from 0.7% to 39.4%, supported by greater structural competitiveness. Chile, although maintaining stable volumes, ceded part of its share to Peru’s advance [7].

In the African and European context, the study by van der Merwe et al. (2024) [6] on the competitiveness of South African grape exports to Europe and the threats posed by Peru and Chile stands out. This work employed multiple competitiveness indicators (including Relative Trade Advantage—RTA, Normalized Revealed Comparative Advantage—NRCA, etc.) to assess whether South Africa might be displaced in its primary market (the EU) by shifts in the export orientation of Peru and Chile. The authors concluded that Peru, operating with minimal policy distortions, has strong potential to increase its global competitiveness, and that South Africa, while still competitive, needs to diversify beyond the EU to avoid adverse impacts [6]. This study adds to the state of the art by introducing the notion that trade policy and agreements (tariffs, domestic supports, etc.) also play a role: while South Africa might benefit from a favorable exchange rate, it requires better access to non-European markets to maintain its position.

In addition to these grape-focused studies, the literature is enriched by research on other agricultural products employing similar methodologies (market concentration and comparative advantage analysis). For example, Ballesteros et al. (2024) [22] examined the diversification of Peruvian asparagus exports, using the HHI to measure market concentration. They found high dependence on the U.S. market (despite a slight reduction in recent years), once again highlighting the need to diversify destinations to support export sustainability [21]. Similarly, studies on the mango value chain—such as that of Maya-Ambía et al. in Mexico—have recommended exploring new markets (e.g., Japan) and adding value to reduce excessive dependence on the North American market [23]. Pérez et al. investigated the Spanish case, confirming a direct correlation between higher export diversification and better export performance in the fruit and vegetable sector [24]. These findings across different products reinforce the consensus that diversification is beneficial for the health of agricultural foreign trade.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework of this research is grounded in concepts from international trade theory and industrial organization economics as applied to the agricultural sector, while also incorporating notions of economic sustainability.

1.2.1. Theory of Comparative Advantage and International Competitiveness

The conceptual foundation originates from David Ricardo’s classical theory [25] of comparative advantage, which posits that countries tend to specialize in the production and export of goods for which they have relatively lower costs, importing those in which they are less efficient [26]. In practice, this “hidden” advantage manifests through export performance, giving rise to the concept of revealed comparative advantage (RCA) developed by Balassa (1965) [27].

An important distinction must be made between static competitiveness and dynamic or sustainable competitiveness. A country may exhibit high static competitiveness (very high RCA) simply due to natural endowments (e.g., climate), but sustaining it over time requires adaptability and innovation. Recent trade models (e.g., theories of dynamic comparative advantage, economic complexity) suggest that diversifying and upgrading to higher value-added chains is key for long-term development [25,28,29]. In this regard, there is an ongoing theoretical debate on whether a developing country should deeply specialize in its commodities where it holds an advantage (maximizing its RCA) or diversify its export base to evolve toward a more complex and less vulnerable structure. Theoretical and empirical studies have shown that export diversification can drive sustained economic growth by reducing volatility and exposing the country to broader learning opportunities [30]. However, other studies argue that smart specialization can sustain competitiveness if focused on high-productivity sectors while mitigating risks through other means [31,32].

1.2.2. Market Diversification and Export Sustainability

An exporting country faces a risk in its foreign trade if its income relies heavily on one or a few markets [33]. Theoretical foundations suggest that greater diversification reduces total variability, offering protection against abrupt downturns in a specific market [34]. In commercial practice, diversifying export markets may require additional efforts (adapting to diverse preferences, complying with different standards), but it serves as a “hedge” against demand fluctuations or restrictive measures in any given destination [35]. For example, exporting to more countries provides a safeguard against future risks: if demand declines in one, others can help sustain the business [36]. This principle is central to the concept of export sustainability—not referring here to environmental sustainability (although that is also relevant), but to the ability to maintain a stable or growing export flow over time without succumbing to external shocks. Theoretically, it is related to the idea of balanced development advanced by Raúl Prebisch and other structuralists, who warned against excessive dependence on a few products or markets [37].

In addition to Ricardo, the framework incorporates notions from firm theory and international competition. The resource-based view (RBV) at the micro level indicates that a firm’s (or by extension, a sector’s) sustainable competitiveness stems from possessing valuable and rare resources and capabilities that are difficult to imitate (Barney, 1991) [38,39]. At the macro level, Porter’s theory of national competitive advantage suggests that a sector’s competitiveness depends on the competitive diamond: specialized factors of production, sophisticated domestic demand, supporting industries, and firm strategy and rivalry [40].

Economic sustainability also requires consideration of long-term dynamics: how a sector can grow steadily without depletion. In agriculture, this has not only the ecological dimension (use of water, soil, etc.) but also the economic dimension of avoiding collapse amid price or supply cycles [41]. The export sector is sustainable if it maintains its competitiveness (comparative advantage) while also spreading risk (diversification). In practice, countries tend to diversify markets once production is consolidated; that is, they first gain capacity and competitiveness (RCA increases) and then seek new destinations (HHI decreases). However, there are cases where the urgency for foreign exchange leads a country to sell almost entirely to the first available market (RCA rises, but so does HHI).

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a quantitative and descriptive approach, aimed at analyzing competitiveness and market diversification in global grape exports as strategic factors for their sustainability. For this purpose, the analysis focuses on tariff subheading 080610 of the Harmonized System, corresponding to “fresh grapes” to ensure an accurate representation of the international trade of the product in question. Data were collected from the Trade Map statistical database, a specialized source in international trade, covering the period from 2020 to 2024. The unit of measurement used was FOB value in U.S. dollars, ensuring comparability across countries.

The analysis included the main exporting countries: Peru, the Netherlands, Italy, Chile, China, the United States, and South Africa, which together accounted for approximately 70% of global exports during the analyzed period. To assess market diversification, the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) was used. Competitiveness, in turn, was estimated using the Normalized Revealed Comparative Advantage index (NRCA).

The HHI [42], originally developed in industrial economics as a measure of market concentration, has proven highly useful when adapted to export analysis. In the agri-export context, the HHI is typically used to quantify how concentrated a country’s external sales are across various destinations or products. It is calculated as the sum of the squares of the percentage shares of each element [43] (for example, each destination market in the product’s total exports). HHI values are inversely interpreted in terms of diversification: low values indicate a highly diversified (evenly distributed) structure, while high values imply that the majority of exports are concentrated in a few destinations or products. By convention, an HHI below 1000 reflects a diversified market, between 1000 and 1800 indicates moderate concentration, and above 1800 denotes high concentration [21]. Numerous previous studies have applied the HHI [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. These precedents confirm that the HHI is an appropriate indicator for assessing trade sustainability: a high value suggests vulnerability (a shock in the main market could collapse exports), whereas a low value suggests resilience (export revenues are “diversified” and thus partly protected from the volatility of a single market).

Meanwhile, the revealed comparative advantage (RCA), often referred to as Balassa’s index, is a concept derived from international trade theory. In 1965, Bela Balassa proposed this index to measure the extent to which a country’s actual export structure reflects its comparative advantages, even without directly knowing relative production costs [27,54].

The RCA index identifies whether a country has export specialization in a specific product. It is calculated by comparing the share of a product in a country’s total exports with the same product’s share in total world exports. Simply put, if a country exports proportionally more of a product than the global average, it is considered to possess a revealed comparative advantage. The RCA value is interpreted as follows: if the index is greater than 1, the country has a comparative advantage in that product; if less than 1, it does not. However, because the index can take very large values, a normalized version is often used to facilitate comparisons between products and countries. This study employed the normalized RCA (NRCA), which is calculated by subtracting 1 from the RCA and dividing the result by the sum of RCA + 1. Thus, the normalized index ranges from 1 to +1. A positive value indicates comparative advantage; a value near zero reflects neutrality; and a negative value indicates comparative disadvantage. This transformation allows for a more balanced and comparable interpretation in international competitiveness studies [55,56]. Regarding specific precedents, the literature offers numerous applications of RCA [27,57,58,59,60].

In combining HHI and RCA in agricultural analysis, it is important to emphasize that both indices complement each other in assessing export sustainability. Evidence shows that having a high comparative advantage in a product is not sufficient to guarantee sustainable success; it is equally crucial that exports are diversified across destinations or markets. For example, a country may show a high RCA but also a high HHI, indicating risk due to market concentration [1]. In contrast, a country may have a moderate RCA but a low HHI, suggesting that, although it is not globally dominant in that product, its sales are well distributed and less vulnerable to individual market shocks [61,62,63,64].

3. Results

3.1. Perú

Table 1 shows that Peru’s grape exports have experienced significant growth between 2020 and 2023, increasing from USD 991.1 million to USD 1765.3 million, although a slight contraction is observed in 2024 to USD 1705.2 million. The main destination is the United States, which on average accounts for 51% of the total exported value during the period. The Netherlands and Mexico stand out as increasingly important markets, with average annual growth rates of 17.6% and 40.7%, respectively. The dispersion of other destinations reflects a relatively diversified market, although with a high dependency on the U.S. market.

Table 1.

Destination of Peru grape exports in millions of dollars.

Table 2 indicates that the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) reveals a highly concentrated structure in Peru’s grape export destinations, remaining above 2000 throughout the period and reaching 2780.6 in 2024. This value indicates limited diversification, with most shipments concentrated in a few countries, which increases risk in the face of potential demand shifts in main markets.

Table 2.

Diversification of Peru grape exports.

Table 3 shows that Peru maintains a positive revealed comparative advantage (RCA) in all major destinations except Canada. Sustained increases are observed in Mexico, where the index rises from 0.55 to 0.75, and in the Netherlands, reaching 0.64 in 2024. The persistent negative value in Canada reflects a competitive disadvantage, while volatility in the UK suggests some instability in Peru’s market position.

Table 3.

Revealed comparative advantage of Peru towards its main export destinations.

3.2. Netherlands

Table 4 shows that the Netherlands increased its grape exports from USD 794.6 million in 2020 to USD 1119.9 million in 2024, with an average annual growth of 10.9%. Germany is the main destination, consistently accounting for about 38% of total exports, followed by Poland and Belgium with moderate increases. The “Others” category maintains a significant share, indicating relative market diversification.

Table 4.

Destination of Netherlands grape exports in millions of dollars.

Table 5 indicates that the Netherlands’ HHI ranges from 1742.8 to 2067.5, placing the country in a position of moderate concentration. While some balance exists, the structure does not qualify as fully diversified, implying vulnerability to changes in key destinations.

Table 5.

Diversification of Netherlands’ grape exports.

Table 6 shows a strong comparative advantage relative to Poland (values above 0.9 every year), and positive, stable values in Germany and the Czech Republic. In contrast, the Netherlands lacks comparative advantage in Belgium, where the index remains negative or near zero, indicating difficulties in competing in that market.

Table 6.

Revealed comparative advantage of Netherlands towards its main export destinations.

3.3. Italy

Table 7 reveals that Italy increased its grape exports from USD 839.3 million in 2020 to USD 996.6 million in 2024, with an average annual growth rate of 4.4%. Germany, France, and Poland are the main markets, jointly accounting for over 55% of the exported value. The participation of “Others” is also relevant, suggesting some dispersion but with a clear predominance of European markets.

Table 7.

Destination of Italy grape exports in millions of dollars.

Table 8 shows that the HHI remains below 1800 each year, ranging from 1507.4 to 1713.7, indicating moderate concentration and nearing the threshold of diversification. Italy exhibits one of the most balanced profiles among major exporters.

Table 8.

Diversification of Italy grape exports.

Table 9 shows that Italy maintains a positive comparative advantage in Germany, Poland, and France, particularly improving in Poland, where the index increases from 0.43 to 0.63. However, in the UK and Spain, the values are low or negative, reflecting limited competitiveness in these destinations.

Table 9.

Revealed comparative advantage of Italy towards its main export destinations.

3.4. Chile

Table 10 shows that Chilean grape exports have fluctuated significantly: after a peak in 2022 (USD 1732.7 million, likely atypical), the value stabilizes around USD 930 million in 2020, 2021, and 2024. The U.S. remains the dominant destination, representing on average 46% of exports, followed by China, although its share dropped sharply from USD 188.2 million in 2020 to USD 57.9 million in 2024.

Table 10.

Destination of Chile grape exports in millions of dollars.

Table 11 shows persistently high HHI values (from 2241.2 to 3302.1), indicating high concentration, especially intensified in 2024, which suggests increasing dependence on a few markets and a lack of diversification.

Table 11.

Diversification of Chile grape exports.

Table 12 reveals a strong and sustained comparative advantage in the U.S. and UK markets, but marked disadvantage in China and the Netherlands, where the index is negative across nearly all years, reflecting a loss of competitiveness.

Table 12.

Revealed comparative advantage of Chile towards its main export destinations.

3.5. China

Table 13 indicates that China’s grape exports have fluctuated, starting at USD 1212.7 million in 2020 and recovering to USD 927.8 million in 2024 after a low point in 2022. Vietnam and Thailand are the predominant markets, together accounting for over 50% of total exports in most years, revealing strong regional concentration.

Table 13.

Destination of China grape exports in millions of dollars.

Table 14 shows a moderate concentration trend, with HHI values between 1626.0 and 2294.2. The 2023 and 2024 values suggest slight improvements in diversification, though major markets still dominate.

Table 14.

Diversification of China’s grape exports.

Table 15 highlights a consistently positive comparative advantage in Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines. However, China’s position in Kyrgyzstan is volatile, shifting from negative to positive, possibly reflecting situational market changes.

Table 15.

Revealed comparative advantage of China towards its main export destinations.

3.6. United States of America

Table 16 shows that U.S. grape exports have remained relatively stable, increasing slightly from USD 822.3 million in 2020 to USD 843.7 million in 2024. Canada is the main market, accounting for about 44% of total exports, followed by Mexico, which shows an 11.7% average annual growth. Other destinations have minor but stable shares.

Table 16.

Destination of United States of America’s grape exports in millions of dollars.

Table 17 shows that HHI values range from 1719.4 to 2869.9, with an upward trend indicating growing concentration, particularly in 2023 and 2024, when the index exceeds the high concentration threshold. This reflects increasing dependence on a few markets, especially Canada.

Table 17.

Diversification of United States of America’s grape exports.

Table 18 shows sustained comparative advantage in Canada, Taipei, and Australia. In contrast, values in Mexico and Vietnam are closer to neutrality, indicating moderate competitiveness. The U.S. position in Taipei appears to be strengthening.

Table 18.

Revealed comparative advantage of United States of America towards its main export destinations.

3.7. South Africa

Table 19 shows significant growth in South Africa’s grape exports, from USD 520.2 million in 2020 to USD 838.8 million in 2024, with an average annual growth rate of 12.7%. The Netherlands and the UK dominate, together accounting for 67% of exports in 2024. Other destinations hold minor shares, reflecting a poorly diversified structure.

Table 19.

Destination of South Africa’s grape exports in millions of dollars.

In Table 20, the HHI remains elevated, ranging from 2379.1 to 3302.1, reflecting a high level of concentration that intensified in 2024. This underscores that South Africa’s export structure is heavily reliant on a few markets.

Table 20.

Diversification of South Africa’s grape exports.

Table 21 indicates a high and consistent revealed comparative advantage in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Canada, with indices above 0.6 across all years. Conversely, a competitive disadvantage is evident in the United States and Germany, where values are negative or near zero.

Table 21.

Revealed comparative advantage of South Africa towards its main export destinations.

In Table 22, Peru has achieved the highest relative growth in grape exports, positioning itself as a new leader in the global market. However, its HHI reveals that diversification remains a challenge, as nearly half of its shipments are directed to the United States, and its concentration index is the highest after Chile. While Peru shows a strong comparative advantage in Mexico and the Netherlands, it maintains a disadvantage in Canada, indicating markets still to be captured.

Table 22.

Comparative Table of Grape Exports (2020–2024).

The Netherlands functions as a European logistics hub, with exports mainly directed to Germany. Concentration remains at a moderate level, implying a certain balance in the destination portfolio, although dependence on Germany is evident. Its very high comparative advantage in Poland stands out, while competitiveness in Belgium remains marginal.

Italy maintains a diversified portfolio within Europe, with Germany and France as its main markets. Its HHI remains below the high-concentration threshold, indicating a relatively balanced portfolio. Italy shows comparative advantage in emerging markets such as Poland, but limited competitiveness in Spain and the United Kingdom, which constrains its expansion beyond the traditional European bloc.

Chile faces the highest level of concentration, with more than half of its exports directed to the United States and a sharp decline in China. The highest HHI among the group indicates that diversification is critical and still pending. While Chile retains strong competitive advantage in the United Kingdom, it is losing ground in China and the Netherlands, revealing vulnerability to demand shifts in these markets.

China presents the highest volatility. Following a 23% drop during the period, it has improved its diversification but remains overly dependent on neighboring markets such as Vietnam and Thailand. Its comparative advantage is high in these countries, though unstable in smaller markets such as Kyrgyzstan, reflecting an opportunistic and weakly consolidated profile.

The United States shows stagnation in its exports, with a slight trend toward increasing concentration, primarily in Canada and Mexico. Its portfolio is less diversified than expected, with strong competitiveness in Asian markets such as Taipei but neutrality in Mexico, suggesting limited penetration in non-traditional markets.

South Africa has experienced solid growth, but its export structure remains heavily concentrated in the European Union and the United Kingdom. Its comparative advantage is highest in Canada, but persistent disadvantages in the United States and Germany limit its global projection. The increasing HHI highlights the need to diversify in order to sustain long-term growth.

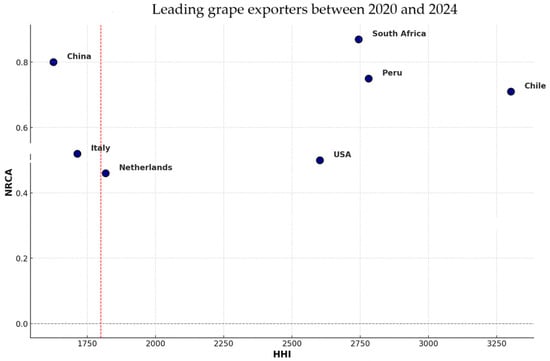

In Figure 1, the distribution of leading table grape exporters between 2020 and 2024 is presented using the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) on the horizontal axis and the Normalized Revealed Comparative Advantage (NRCA) on the vertical axis. The red dashed line indicates the threshold of market concentration (HHI = 1800), which separates moderately concentrated markets (to the left) from highly concentrated ones (to the right). The scatter plot shows that Chile (HHI = 3302.1; NRCA = 0.71), Peru (HHI = 2780.6; NRCA = 0.75), and South Africa (HHI = 2744.4; NRCA = 0.87) combine strong competitiveness with excessive concentration, suggesting structural vulnerability despite their solid positions in global trade. Conversely, Italy (HHI = 1713.7; NRCA = 0.52) and the Netherlands (HHI = 1817.1; NRCA = 0.46) exhibit more diversified export structures but only moderate comparative advantages. China (HHI = 1626.0; NRCA = 0.80) is notable for maintaining low concentration alongside high competitiveness in its regional markets, while the United States (HHI = 2602.4; NRCA = 0.50) reveals persistent dependence on Canada despite moderate advantages. Overall, the evidence underscores a structural trade-off: no country simultaneously achieves both broad diversification and strong comparative advantage, which highlights a key sustainability challenge for table grape exports.

Figure 1.

Scatter Plot of HHI vs. NRCA (2020–2024).

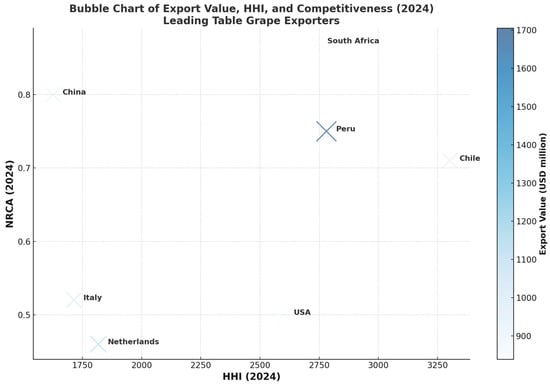

Figure 2 shows clear contrasts among leading table grape exporters. Countries such as Peru, South Africa, and Chile combine strong competitiveness with high market concentration, highlighting their dependence on a few destinations despite large export volumes. By contrast, Italy and the Netherlands achieve more balanced and diversified export portfolios, though their competitive advantage is only moderate. China stands out for simultaneously maintaining relatively high competitiveness and lower concentration, largely within its regional sphere. Meanwhile, the United States reflects structural dependence on a single market despite moderate competitiveness. Overall, the chart confirms the structural trade-off in global grape exports: strong competitive positions often coexist with limited diversification, while greater diversification tends to come at the cost of reduced comparative advantage.

Figure 2.

Bubble Chart of Export Value, Market Concentration (HHI), and Competitiveness (NRCA) in Leading Table Grape Exporters, 2024.

4. Discussion

The comparative analysis of grape exports between 2020 and 2024 reveals heterogeneous performance among leading countries, with distinct profiles in terms of growth, diversification, and competitiveness. In line with previous studies [1,7,8,21,24,40], the results confirm that sustainable export performance depends not only on export volume but also on diversification of markets and the maintenance of revealed comparative advantage (RCA).

Peru represents the archetype of an emergent global competitor. Its export value increased by 72% in the five-year period, positioning it as the top exporter in 2024. However, its Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) of 2780.6 reflects a highly concentrated export structure, primarily oriented to the U.S. market, which absorbs 49% of its shipments. Although Peru exhibits a solid RCA in Mexico (0.75) and the Netherlands (0.64), it remains uncompetitive in Canada (−0.18), which underscores the vulnerability of its current model, as warned by [1,7]. This confirms the theoretical perspective that high RCA must be accompanied by market dispersion to ensure resilience [21].

Chile, once the dominant exporter from the Southern Hemisphere, displays the highest market concentration (HHI = 3302.1) and limited export growth (+0.5%), indicating structural stagnation. Despite maintaining strong competitiveness in the UK (0.83), Chile’s negative RCA in China (−0.71) and the Netherlands (−0.05) reflects declining positioning in key markets, consistent with the competitive erosion discussed in [6,7]. These findings reinforce the importance of dynamic RCA as a component of long-term sustainability [25].

South Africa illustrates a case of rapid export expansion (+61%) yet persistent dependence on two markets—the Netherlands and the UK—which together accounted for 67% of its 2024 exports. With an HHI of 2744.4, the country’s structure is vulnerable despite a strong RCA in Canada (0.95). These results echo prior warnings in [6], where limited access to markets beyond Europe was identified as a constraint for future competitiveness. The theory of competitive advantage highlights the need for strategic repositioning beyond favorable exchange rates or historical ties [40].

In contrast, the Netherlands and Italy offer more diversified export portfolios. The Netherlands, with an HHI of 1817.1, functions as a re-export hub and maintains high competitiveness in Poland (0.92), but its marginal RCA in Belgium (0.03) reveals weaknesses even in proximate markets. Italy, with an HHI of 1713.7, has managed to keep a moderately diversified structure, showing growth in markets like Poland (RCA rising from 0.43 to 0.63), though still facing challenges in Spain (0.01) and the UK (0.25). These trends validate previous findings that diversification within Europe can mitigate concentration risks, but may not fully compensate for low cost competitiveness relative to emerging players [8,24].

China’s performance is marked by volatility. After a 23% drop in exports over the period, its structure remains centered on Southeast Asia, particularly Vietnam and Thailand, where it holds strong RCA values (0.72 and 0.80, respectively). However, erratic behavior in marginal markets like Kyrgyzstan reveals a fragile and opportunity-driven strategy. This aligns with the observations of [8] on the instability of new exporters without robust institutional and logistical foundations. While China has made progress in market access, its export sustainability is still questionable.

Finally, the United States NRCA shows near stagnation in export value (+2.6%) and a rising concentration risk (HHI = 2602.4), mainly due to dependency on Canada (45%). Although it maintains competitive positions in Taipei (0.78) and Australia (0.67), its RCA in Mexico (0.14) remains neutral, suggesting limited ability to expand in strategic neighbors. This outcome corroborates concerns expressed in [1,7], where the loss of market share to more aggressive exporters like Peru was associated with insufficient innovation and market development strategies.

In conclusion, the analysis confirms the dual requirement for sustainable agricultural exports: dynamic international competitiveness (reflected in RCA) and robust diversification (measured by HHI). The trade-offs between specialization and diversification are evident across the cases studied. Countries like Peru and South Africa, while rapidly expanding, remain exposed to market shocks due to high concentration. Others, like the Netherlands and Italy, achieve greater resilience but face growth constraints. These patterns validate theoretical arguments that favor a balanced export strategy, combining comparative advantage with proactive diversification [6,21,34,38].

5. Conclusions

The results reveal clear contrasts between the seven main grape-exporting countries. Peru has achieved the fastest growth and now leads in export value, yet it remains highly dependent on the U.S. market, mirroring Chile’s extreme concentration, which is coupled with a sharp loss of competitiveness in China. South Africa also shows strong growth and very high NRCA in Canada and the Netherlands but faces risks from its dependence on a limited number of European destinations. The United States, while maintaining competitiveness in Canada, Taipei, and Australia, shows stagnation and overreliance on its northern neighbor, with underexploited potential in Mexico. China exhibits very high NRCA in Southeast Asian markets such as Vietnam and Thailand, but remains regionally concentrated, limiting long-term resilience. In contrast, the Netherlands and Italy display more balanced market portfolios within Europe, although their competitiveness is moderate and concentrated in specific partners.

Taken together, the evidence confirms that no country simultaneously achieves both top-level competitiveness and low market concentration. Those with strong NRCA values—such as Peru, South Africa, and China—tend to depend heavily on a few destinations, leaving them vulnerable to demand fluctuations and competitive shifts. Conversely, countries with more diversified portfolios—such as the Netherlands and Italy—tend to have moderate comparative advantages, which can constrain global expansion. The findings underscore that sustainable export performance in the grape sector requires an integrated approach, combining the consolidation of competitive advantages with proactive market diversification to reduce structural vulnerability across all major exporters.

The results reveal that none of the main grape-exporting countries combines both high competitiveness and broad diversification, which makes it essential to design differentiated strategies anchored in quantitative evidence. Peru shows strong competitiveness in Mexico (NRCA = 0.75) but remains highly concentrated in the U.S. market (HHI = 2780.6); this suggests the urgency of opening secondary markets such as Canada, where its NRCA is negative (−0.18). Chile represents the most critical case, with the highest concentration (HHI = 3302.1) despite solid positioning in the UK (NRCA = 0.71), pointing to the need for diversification toward Asia and within Europe. South Africa also combines very high competitiveness in Canada (NRCA = 0.87) with strong dependence on the Netherlands and the UK (HHI = 2744.4), which underscores the importance of exploring new outlets in the Middle East and Asia. The United States, with moderate competitiveness in Taipei (NRCA = 0.50) but heavy reliance on Canada (HHI = 2602.4), should reinforce strategies in Latin America and Asia to reduce vulnerability. In contrast, China presents the most balanced profile, with low concentration (HHI = 1626.0) and high competitiveness in Thailand (NRCA = 0.80), but its challenge lies in projecting this strength into Europe. Finally, Italy and the Netherlands, with lower HHI values (1713.7 and 1817.1, respectively) and only moderate competitiveness (NRCA = 0.52 and 0.46), should focus on enhancing varietal innovation, branding, and certifications to consolidate their role in high-value niches.

Based on the findings obtained, several avenues for future research are identified: (i) the combined application of concentration metrics such as HHI with alternative indices—for example, the Theil Index or the Entropy Diversification Index—to capture additional nuances in market distribution; (ii) the incorporation of competitiveness indicators complementary to NRCA, such as the Relative Trade Advantage (RTA), the Specialization Index, and elasticity-based metrics, to allow for result comparison; (iii) the development of econometric models integrating quantitative indicators with qualitative variables—such as innovation, sustainability, and certifications—to achieve a multidimensional view of competitiveness; and (iv) the application of these approaches in multi-regional comparative studies to identify commonalities and differences across various agricultural products.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.D.G.J., J.C.M.N., N.V.D.L.C.R. and G.V.V.B.; methodology, J.C.M.N.; formal analysis, J.C.M.N.; investigation, H.D.G.J., S.L.L.L., H.Y.M.Y., C.E.M.O., N.V.D.L.C.R., S.J.A.M., C.D.C.O., A.R.R.A. and G.V.V.B.; validation, S.L.L.L., S.J.A.M. and A.R.R.A.; writing—review & editing, H.D.G.J., H.Y.M.Y., C.E.M.O., C.D.C.O., A.R.R.A. and G.V.V.B.; project administration, H.D.G.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Montes Ninaquispe, J.C.; Vasquez Huatay, K.C.; Ludeña Jugo, D.A.; Pantaleón Santa María, A.L.; Farías Rodríguez, J.C.; Suárez Santa Cruz, F.; Escalona Aguilar, E.O.; Arbulú-Ballesteros, M.A. Market Diversification and Competitiveness of Fresh Grape Exports in Peru. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubenets, I. Diversification of international trade: Problems of theory. Financ. Strateg. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2021, 52, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.; Tomas, M. A focus on international competitiveness. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostoska, O.; Hristoski, I. Trade dynamics, revealed comparative advantage, and international competitiveness: Evidence from Macedonia. Econ. Ann. 2018, 63, 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilinkienė, V. Evaluation of International Competitiveness Using the Revealed Comparative Advantage Indices: The Case of the Baltic States. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, J.-M.; Vink, N.; Cloete, K. The competitiveness of South African table grape exports in the European markets: Threats from Peru and Chile. Agrekon 2024, 63, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Espinosa, D.; Méndez-León, J.R. The Competitive Dynamics of Mexican Fresh Grapes in the U.S. Market. World 2025, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seccia, A.; Santeramom, F.; Nardone, G. Trade Competitiveness in Table Grapes: A Global View. 2015. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/70931/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Delgado, A. Chile Crece un 5% en Exportación de uva, Pero Perú lo Supera con un 32% Más. Infobae. Available online: https://www.infobae.com/peru/2025/06/19/chile-crece-un-5-en-exportacion-de-uva-pero-peru-lo-supera-con-un-32-mas (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Marítima, A. Chile Recuperó Liderazgo Tras Exportar 64 Millones de Cajas de uva en la Temporada 2023–2024. Available online: https://www.agendalogistica.cl/comercio-exterior-exportaciones-frutas-de-chile/chile-recupero-liderazgo-tras-exportar-64-millones-de-cajas-de-uva-en-la-temporada-2023-2024/1797573 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Dupas, A.; Maggs, R.; Hort, J. Exploring Consumer and Producer Views of Verjuice: A Grape-Based Product Made from Viticultural Waste. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2023, 2023, 5548698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, A.; Rindermann, R.; Chávez, B. Vegetables in Mexico: From U.S. Competitiveness and Opportunities for Development. J. Glob. Compet. Governability 2014, 6, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, M.; Chiripuci, B.; Deaconu, E.-M.; Ignat, R. Revealing Subtle Competitiveness Nuances in the EU Wine Value Chain by Expanding the Applicability of Elasticities. Amfiteatru Econ. 2025, 27, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofuit Grapes on Target in South Africa. Available online: https://desktop.eurofruitmagazine.com/p/eurofruit/fruit-logistica-edition-part-i/a/grapes-on-target-in-south-africa/9063/1848333/60912657 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Pawson, N. SA Breaks Record for Table Grape Exports, UK Tops Destination List. Available online: https://www.thesouthafrican.com/news/sa-breaks-record-for-table-grape-exports-uk-tops-destination-list (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Matthee, M.; Idsardi, E.; Krugell, W. Can South Africa sustain and diversify its exports? South. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2016, 19, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco-Lajara, B.; Zaragoza-Sáez, P.; Martínez-Falcó, J.; Sánchez-García, E. The Internationalization of the Spanish Wine Industry: An analysis of trade flows and their degree of concentration. In The Transformation of Global Trade in a New World; IGI Global: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojnec, S.; Ferto, I. Export competitiveness of the European Union in fruit and vegetable products in the global markets. Agric. Econ. 2016, 62, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmonova, D. The Role of Marketing Strategies in Improving the Export Potential of Grape Growing Enterprises. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev. 2024, 7, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, D. Grapes Exports by Country. Available online: https://www.worldstopexports.com/grapes-exports-by-country/#:~:text=1.%20Peru%3A%20US%241.7%20billion%20%2818.8,8 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Karaman, S.; Özkan, B.; Yigit, F. Export Competitiveness of Turkish Agri-Food Products in the European Union and The Shanghai Cooperation Markets. Tarım Bilim. Derg. 2022, 29, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, M.A.; Ninaquispe, J.C.M.; Jugo, D.A.L.; Castillo, J.C.A.; Aldana, M.L.; María, A.L.P.S.; Godos, K.M.A.; Chacon, S.V.R. Diversification of fresh asparagus exports from Perú. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2024, 14, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, J.C.; Arbulú, M.A.; Ludeña, D.A.; Escalona, E.O.; de los Ángeles Guzmán, M.; Cruz, L.E.; Farfán, G.C.; García, H.D. Agricultural products export strategy: Expanding reach through diversification. Corp. Bus. Strategy Rev. 2024, 5, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya, C.; Sakamoto, K.; Retes, L. Diversificación de los mercados frutícolas externos de México ante los desafíos de la globalización: El caso de las exportaciones de mango a Japón. Méx. Cuenca Pac. 2011, 42, 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A. David Ricardo’s Principle of Comparative Cost Advantage inspires International Trade. SSRN 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.; Laca, A.; Laca, A.; Díaz, M. Environmental behaviour of blueberry production at small-scale in Northern Spain and improvement opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balassa, B. Trade Liberalisation and ‘Revealed’ Comparative Advantage. Manch. Sch. 1965, 33, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banguero, H. Competitividad Sostenible: Qué es y cómo Lograrla; Sello Editorial Unicatolica: Cali, Colombia, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunevičiūtė, L.; Danilevičienė, I.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Assessment of the factors influencing competitiveness fostering the country’s sustainability. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraž. 2020, 33, 1909–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnovskaya, V. Sustainability as the Source of Competitive Advantage. How Sustainable is it? In Creating a Sustainable Competitive Position: Ethical Challenges for International Firms; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninaquispe, J.C.M.; Arbulú-Ballesteros, M.A.; Valle, M.G.; Morales, A.E.P.; Salinas, L.E.C.; Farfán-Chilicaus, G.C.; Juárez, H.D.G.; Sanchez, J.E.B. Diversification of Export Markets: A Literature Review. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2024, 14, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L.; Oliva, S.; Innocenti, N. Unfolding Smart Specialisation for Regional Economic Resilience: The role of Industrial Structure. Investig. Reg. J. Reg. Res. 2022, 54, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopczynska, E.; Ferreira, J. Smart Specialization as a New Strategic Framework: Innovative and Competitive Capacity in European Context. J. Knowl. Econ. 2020, 11, 530–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Z.; Geng, Y. Country Risk and Wooden Furniture Export Trade: Evidence from China. Prod. J. 2022, 72, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, F.; Koren, M.; Lisicky, M.; Tenreyro, S. Diversification Through Trade; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, H. Can Export Market Diversification Mitigate Agricultural Export Volatility? A Trade Network Perspective. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2023, 59, 2234–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratukhina, E.; Nagovitsyna, E.; Tusin, D. Company Risk Management in Export Activities; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, J. Raúl Prebisch e a concepção e evolução do sistema centro-periferia. Rev. Econ. Polít. 2017, 37, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komakech, R.; Ombati, T.; Kikwatha, R.; Wainaina, M. Resource-based view theory and its applications in supply chain management: A systematic literature review. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2025, 15, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barghouthi, O. Analysis of Competitive Advantage of the Basic Industries in Palestine Based on the Porter’s Diamond Model. Int. J. Mark. Res. Innov. 2017, 1, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center, I.T. Trade Map—Trade Statistics for International Business Development. Available online: https://www.trademap.org/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Almeida, L.; Tavares, F. Impact COVID-19 Pandemic in Supply Chain. In Reference Module in Social Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, T.; Vink, N.; Cloete, K. Covid-19 and the South African wine industry. Agrekon 2022, 61, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herfindahl, O. Concentration in the Steel Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Political Science, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Justice—The United States. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index. 2024. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/atr/herfindahl-hirschman-index (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Salas-Tenesaca, E.E. Concentration and profitability: An analysis of the private financial system in Ecuador during the period 2015–2023. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2025, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarin, S.A. Convergence of tourism market diversification: Evidence from a new indicator based on Herfindahl–Hirschman index. Qual. Quant. 2025, 59, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.H.D. Environmental, social and governance performance and firm value: Does ownership concentration matter? Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 488–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciarelli, P.; Hache, E.; Mignon, V. Evaluating criticality of strategic metals: Are the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index and usual concentration thresholds still relevant? Energy Econ. 2025, 143, 108208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jofre-Bonet, M.; McGuire, A.; Dayer, V.; Roth, J.A.; Sullivan, S.D. The Price Effects of Biosimilars in the United States. Value Health 2025, 28, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wei, S.; Zhou, H.; Hu, F.; Chen, Y.; Hu, H. The Global Industrial Robot Trade Network: Evolution and China’s Rising International Competitiveness. Systems 2025, 13, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Juárez, H.D.; Montes Ninaquispe, J.C.; Marquez Yauri, H.Y.; Rodríguez Abraham, A.R.; Corrales Otazú, C.D.; Apaza Miranda, S.J.; Suysuy Chambergo, E.J.; León Luyo, S.L.; Flores Castillo, M.M. Market Diversification and International Competitiveness of South American Coffee: A Comparative Analysis for Export Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirajing, M.A.K.; Moutie, V.G.; Nkoa, B.E.O.; Ketchoua, G.S. An analysis of the moderating role of Internet penetration in the banking competition-banks’ profitability nexus: Case of the CEMAC banking sector. Digit. Financ. 2025, 7, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, T. Impact of a new case-based payment scheme on volume distribution across public hospitals in Zhejiang, China: Does ‘Same disease, same price’ matter. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki, M.B.; Samarghandi, H.; Bruneau, J. The Effect of CUSFTA and NAFTA on Canada’s Export Composition. J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2025, 25, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, J.; Alvarez, M. Indicadores de Comercio Exterior y Política Comercial: Mediciones de Posición y Dinamismo Comercial. 2008. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/fe74661f-0205-4b32-be44-b7dfeb10d3c1/content (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Mann, S.; Beciu, S.; Arghiroiu, G.A. Colouring the Balassa index: A hermeneutic approach towards Romanian meat imports. Cienc. Rural 2023, 53, e20210811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droždz, J.; Burinskas, A.; Cohen, V. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Revealed Comparative Advantage of Industries in the Baltic States. Economies 2023, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Ç.; Bozoğlu, M.; Urago, G.G. Türkiye’s Competitive Power in the World Hazelnut Market. Appl. Fruit. Sci. 2024, 66, 921–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unuvar, F.I.; Uzun, B.; Dellal, İ. Assessment of Turkiye’s Competitiveness in International Quince Trade. Appl. Fruit. Sci. 2024, 66, 2179–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Sarkar, A. Bimstec’s incipient competitive advantage and trade specialisation in raw sugar. Econ. Ann. 2025, 70, 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Acharjee, P.; Bairagi, M. India’s Comparative Advantage and Trade Specialization in the Wheat Sector vis-à-vis the BIMSTEC Countries. Diyala Agric. Sci. J. 2024, 16, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, J.; Cavallo, E. Does Openness to Trade Make Countries More Vulnerable to Sudden Stops, or Less? Using Gravity to Establish Causality. SSRN 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).