Community-Centered Farm-Based Hospitality in Agriculture: Fostering Rural Tourism, Well-Being, and Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Clarifications: Agritourism, Farm-Based Tourism, Eco-Friendly Tourism, and Rural Tourism

2.2. Literature Overview

3. Materials and Methods

South Tyrol as a Model Destination for Sustainable, Community-Centered Farm-Based Hospitality

4. Results

- -

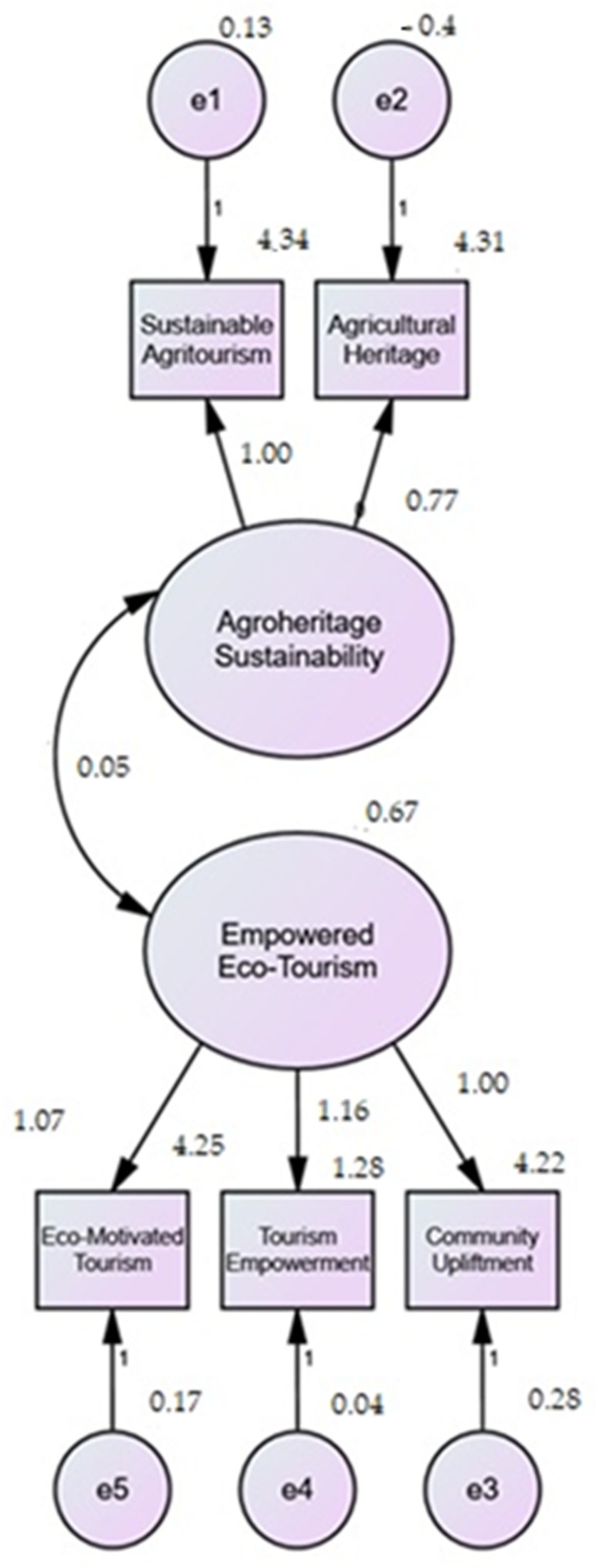

- Sustainable Agritourism—This item reflects residents’ recognition of the environmental benefits of agritourism, particularly its role in preventing land abandonment, supporting landscape maintenance, and encouraging eco-friendly farming practices. In South Tyrol—characterized by terraced vineyards, alpine pastures, and smallholder farms—residents may view agritourism as an opportunity to maintain productive use of rural land while diversifying income. Their belief in tourism’s capacity to support sustainable land use reflects a localized understanding of landscape stewardship and territorial resilience.

- -

- Agricultural Heritage—This item illustrates the cultural dimension of sustainability, highlighting residents’ perception that tourism strengthens intergenerational knowledge transfer, traditional farming methods, and cultural rituals tied to agriculture. In regions like Alto Adige, where traditions such as haymaking, grape harvesting, and artisanal food production are integral to local identity, agritourism is seen as a mechanism for cultural survival in a rapidly modernizing economy. The community’s support for agritourism reflects a commitment to valorizing agricultural heritage and integrating it into the visitor experience. Together, these items indicate that residents view agritourism as more than a source of economic activity. It is understood as a holistic approach to rural development—one that sustains the landscape, safeguards traditional knowledge, and affirms local identity. This factor aligns with the paper’s emphasis on community-centered hospitality, reinforcing the idea that local actors play a proactive role in shaping sustainable rural futures.

- -

- Eco-Motivated Tourism—This item reflects residents’ alignment with pro-environmental values, possibly indicating that those who are involved in tourism activities—whether as hosts or stakeholders—favor tourism forms that minimize environmental degradation. In a sensitive alpine ecosystem like South Tyrol’s, where environmental preservation is critical, residents’ environmental motivation suggests a readiness to support and engage with low-impact tourism models that reinforce sustainable development goals.

- -

- Tourism Empowerment—This item captures the sense of agency and involvement residents derive from their participation in the tourism sector. Empowerment here refers to increased confidence, decision-making capacity, and perceived value in shaping the local tourism offer. In South Tyrol, where farm operators often serve as hosts, guides, and producers, participation in agritourism enables them to diversify roles and gain recognition within and beyond their communities.

- -

- Community Upliftment—This item underscores residents’ view that tourism acts as a catalyst for community-wide improvements. The presence of visitors can encourage investment in public infrastructure, hygiene, hospitality services, and aesthetic upkeep. This motivation is particularly relevant in small rural municipalities where tourism revenue can incentivize improvements that also benefit year-round residents, thus strengthening community well-being and quality of life. This factor, therefore, represents a community-based vision of eco-tourism, one where residents feel both environmentally responsible and socially empowered. The findings suggest that the community does not passively experience tourism’s effects; rather, they perceive themselves as active contributors and beneficiaries of a sustainable tourism model that aligns with their values.

4.1. Agroheritage Sustainability as a Foundation for Rural Tourism

4.2. Empowered Eco-Tourism as an Outcome of Agro-Based Hospitality

5. Discussion

Confirmations of Sub-Hypotheses

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications for Policy, Practice, and Future Research

6.2. Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Šerić, M.; Patrizi, M.; Ceccotti, F.; Vernuccio, M. Resident perspectives unveiled: The role of a sustainable destination image in shaping pro-sustainable responses. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turčinović, M.; Vujko, A.; Stanišić, N. Community-led Sustainable Tourism in Rural Areas: Enhancing Wine Tourism Destination Competitiveness and Local Empowerment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladan, N. Community-Based Approach in Developing Farm Tourism. Open Access Libr. J. 2020, 7, e7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón, J.; Cañada, E. Repeasantization and synergy between community-based tourism and family farming. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 116, 103627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H. Community Based Tourism. In Reference Module in Social Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliterni, S.; Zulauf, K.; Wagner, R. A taste of rural: Exploring the uncaptured value of tourism in Basilicata. Tour. Manag. 2025, 107, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Su, W.; Kang, S. Role-shaping of rural tourism entrepreneurs and an interpretative framework: A knowledge transfer perspective. Tour. Manag. 2025, 110, 105188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Agarwala, T.; Kumar, S. Rural India: Empowering Through Community Tourism. In Reference Module in Social Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsić, M.; Vujko, A.; Nedeljković, D. The synergy between gastronomy and active tourism as indicator of sustainable rural wellness and spa destination development. Econ. Agric. 2025, 72, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Grudzień, P. The Essence of Agritourism and Its Profitability during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. Agriculture 2021, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, P.; Song, H. Multiple Effects of Agricultural Heritage Identity on Residents’ Value Co-Creation—A Host–Guest Interaction Perspective on Tea Culture Tourism in China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarota, A.; Marino, V.; Resciniti, R. Residents’ perceptions of “sustainable hospitality” in rural destinations: Insights from Irpinia, Southern Italy. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2025, 35, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, G.; Shams, S.M.R.; Metallo, G.; Cuomo, T.M. Opportunities and challenges in the contribution of wine routes to wine tourism in Italy—A stakeholders’ perspective of development. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainville, S.; Aubron, C.; Philippon, O. Workload and remuneration on farms in the south of France: The uncertain future of agroecology. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 116, 103588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, L.H.D.; Zielinski, S. Community-based tourism, social capital, and governance of post-conflict rural tourism destinations: The case of Minca, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Colombia. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.C.L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Does rural sports tourism promote the sustainable development of the destination? -- Based on quasi-experimental evidence of sports and leisure towns in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.L.; Fan, D.X.F.; Wang, R.; Ou, Y.H.; Ma, X.L. Does rural tourism revitalize the countryside? An exploration of the spatial reconstruction through the lens of cultural connotations of rurality. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 29, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panić, A.; Vujko, A.; Knežević, M. Social indicators as an important implications of susatinable rural tourism development. Oditor 2025, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Gutiérrez, D.; Dias, A.C.; Quinteiro, P.; Herrero, Á.; Gallego, M.; Villanueva-Rey, P.; Laso, J.; Albertí, J.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P.; et al. ‘Small-scale’ tourism versus traditional tourism: Which will be the new key to achieve the desired sustainable tourism? Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Hao, J.; Han, Y. Emerging paradigm in redressing the imbalanced “state-village” power relationship: How have rural gentrifiers bypassed institutional exclusion to influence rural planning processes? J. Rural. Stud. 2025, 114, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, B. Rural tourism in China: ‘Root-seeking’ and construction of national identity. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 60, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujko, A.; Arsić, M.; Bojović, R. From Local Product to Destination Identity: Leveraging Cave-Aged Cheese for Sustainable Rural Tourism Development. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuksanović, N.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanović, M.M.; Malinović-Milićević, S.; Radosavac, A.; Obradović, V.; Ergović Ravančić, M. The Role of Culinary Tourism in Local Marketplace Business—New Outlook in the Selected Developing Area. Agriculture 2024, 14, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Gong, W.; Qian, J. Unpacking the multifaceted rurality of Hong Kong’s countryside: A social representation approach. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 114, 103589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Ye, X.; Gianoli, A.; Hou, W. Exploring the dual impact: Dissecting the impact of tourism agglomeration on low-carbon agriculture. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 361, 121204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujko, A.; Bojović, R.; Nedeljković, D.; Jović, M.D.; Todorović, M.J. Can organic farming contribute on sustainable women entrepreneurship in rural tourism? An nacional park evidence. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2024, 57, 1950–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akther, T.; Selim, I.M.M.; Hossain, S.M.; Kibria, G.M. Synergistic role of agriculture production, fertilizer use, tourism, and renewable energy on CO2 emissions in South Asia: A static and dynamic analysis. Energy Nexus 2024, 14, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.K.; Rahman, M.S.U.; Nafi, S.M. Promoting handicraft family business through digital marketing towards sustainable performance. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2024, 55, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K. The Green Revolution, grain imports, and income divergence in the developing world. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2024, 166, 104772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhemimah, A.; Baquero, A.; Al-Romeedy, B.S.; Khairy, H.A. Green organizational learning and sustainable work behavior in tourism and hotel enterprises: Leveraging green intrinsic motivation and green training. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2024, 55, 1134–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, L.; Hui, M. Fostering green economic growth through sustainable management of natural resources. Resour. Policy 2024, 91, 104867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macueia, F.B.E.D.; dos Santos Hackbart, C.H.; de Brito Leal, A.; Crizel, L.R.; Gomes, G.C.; Rombaldi, V.C. Grape (Vitis labrusca L.) juices, cv. Bordô, from vineyards in organic production systems and conventional production: Similarities and differences. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 336, 113252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaracci, S.; Paolotti, L.; Rocchi, L.; Boggia, A.; Castellini, C. Life cycle assessment of organic and conventional egg production: A case study in northern Italy. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2024, 15, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šambronská, K.; Šenková, A.; Kolesárová, S.; Kormaníková, E. Motivational factors and financial support for entering sustainable ecological destinations as impulses for sustainable tourism and environmental protection: A case study on the example of national parks. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2024, 53, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.A.; Pikkemaat, B.; Dickinger, A. Unlocking sustainable tourism: Exploring the drivers and barriers of social innovation in community model destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2025, 36, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedioli, F. Exploring Italian agritourism: A model of sustainable rural development. J. Agribus. Rural. Dev. 2025, 75, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-B.; Doh, K.-R.; Kim, K.-H. Successful managerial behaviour for farm-based tourism: A functional approach. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, J.; Xu, D.; Chen, D.; Tao, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, X. Study on driving factors of island ecosystem health and multi-scenario ecology simulation using ecological conservation and eco-friendly tourism for achieving sustainability. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosalina, P.D.; Dupre, K.; Wang, Y. Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Meng, F.; Chai, S.; Zou, Y. Struggling in silence? The formation mechanism of implicit conflict in rural tourism communities. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsson, T.; Einarsdóttir, J. Volunteer tourism in rural France: Examining power dynamics, labour practices, and community interactions. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 117, 103674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Dang, L. Impacts of goal attainment on rural tourism entrepreneurs’ subjective well-being: The perspective of intergenerational differences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, 62, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillini, G.; Streifeneder, T.; Stotten, R.; Schermer, M.; Fischer, C. How tourists change farms: The impact of agritourism on organic farming adoption and local community interaction in the Tyrol-Trentino mountain region. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 114, 103531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndhlovu, E.; Dube, K. Agritourism and sustainability: A global bibliometric analysis of the state of research and dominant issues. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 46, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.; Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Kim, B.; Seo, J.Y.; Chon, J. Coastal landscape preference of residents and tourists according to the physical attributes and viewpoints of offshore wind farms as seen through virtual reality. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2023, 66, 103157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damnet, A.; Sangnak, D.; Poo-Udom, A. Thailand’s innovative agritourism in the post COVID-19 new normal: A new paradigm to achieve sustainable development goals. Res. Glob. 2024, 8, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, S.; Knollenberg, W.; Vilá, O. Agritourism resilience during the COVID-19 crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2023, 99, 103538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzo, N. The relationship between agritourism and social capital in Italian regions. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 94, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domi, S.; Belletti, G. The role of origin products and networking on agritourism performance: The case of Tuscany. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 90, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, C. What makes customer participation a double-edged sword: The impact and factors of self-serving bias in agritourism. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montefrio, M.J.F.; Sin, H.L. Between food and spectacle: The complex reconfigurations of rural production in agritourism. Geoforum 2021, 126, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzo, N. A quantitative analysis on Romanian rural areas, agritourism and the impacts of European Union’s financial subsidies. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanigan, S.; Blackstock, K.; Hunter, C. Generating public and private benefits through understanding what drives different types of agritourism. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 41, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairabadi, O.; Sajadzadeh, H.; Mohamadianmansoor, S. Assessment and evaluation of tourism activities with emphasis on agritourism: The case of simin region in Hamedan City. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatan, S.; Fleischer, A.; Tchetchik, A. Economic valuation of cultural ecosystem services: The case of landscape aesthetics in the agritourism market. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 184, 107005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochuli, A.; Hochuli, J.; Schmid, D. Competitiveness of diversification strategies in agricultural dairy farms: Empirical findings for rural regions in Switzerland. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annes, A.; Bessiere, J. Staging agriculture during on-farm markets: How does French farmers’ rationality influence their representation of rurality? J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 63, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Luo, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Tan, Z. Findings on agricultural cleaner production in the three Gorges Reservoir Area. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujko, A.; Karabašević, D.; Cvijanović, D.; Vukotić, S.; Brzaković, P.; Mirčetić, V. Women’s empowerment in rural tourism as a key of sustainable communities transformation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Pagliacci, F.; Gatto, P. Determinants of agricultural diversification: What really matters? A review. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 110, 103365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunchistha, P.-U.D.B.A. Resilience and reinvention: Knowledge management strategies for community-based tourism in post-pandemic Thailand. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, C.; Zhi, J.; Zhao, W.; Liu, W.; Xue, C.; Bao, S. Cultural service assessment of cultivated land ecosystem in the Yangtze River Delta region from a supply–demand-flow perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 173, 113378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohorodnyk, V.; Finger, R. Envisioning the future of agri-tourism in Ukraine: From minor role to viable farm households and sustainable regional economies. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 108, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervelli, E.; di Perta, E.S.; Pindozzi, S. Diachronic analyses on land use changes and vernacular architecture distribution, to support agricultural landscape development. J. Cult. Herit. 2025, 71, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrabous, M.; Allali, K.; Fadlaoui, A.; Arib, F. Sustaining agricultural livelihoods: The influence of agrotourism on enhancing wellbeing and income in the Todgha Oasis, Morocco. J. Arid Environ. 2025, 227, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, S. Economic Development and Environmental Conservation: Evidence from Ecotourism. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2025, 73, 1297–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurakhmanova, A.; Ahrorov, F. The economic and social impacts of ecotourism on local employment and income: A case study of rural Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2025, 17, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Pan, J.; Tan, L. Sustainable evaluation of ecotourism in the Yangtze River delta urban agglomeration: A system coordination perspective. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2025, 6, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, C.G.; Knollenberg, W.; Barbieri, C. The craft beverage tourism research agenda: Recommendations to move forward. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2024, 5, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, Q.; Andersen, S.; Bartel, G.; Barnes, I.; Brown, H.; Gambrill, K.; Gerardi, J.; Jones, A.; Harris, M.; Hyland, E.; et al. Understanding and measuring multifunctionality in agriculture at local, regional, and global scales. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik-Leń, J.; Sobolewska-Mikulska, K.; Sajnóg, N.; Leń, P. The idea of rational management of problematic agricultural areas in the course of land consolidation. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, R.; Dash, M. From strengths to strategies: Mapping the sustainable path for ecotourism in Chilika wetland through SWOT-QSPM analysis. J. Nat. Conserv. 2025, 84, 126817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J. Towards a sustainable future: Analysing meta-competencies in community-based ecotourism on Liuqiu Island. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, 62, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chan, E.; Song, H. Social capital and entrepreneurial mobility in early-stage tourism development: A case from rural China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Du, Y.; Li, C.; Gong, Y.; Du, Y. From confrontation to co-production: How China’s ENGOs facilitate residents’ waste management systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Tan, Y.; Zheng, T.; Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, J. A decision framework for rural domestic sewage treatment models and process: Evidence from Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China. J. Environ. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Tuhin, K.A.; Sarker, M.H.S.; Wakil, M.A. Exploring nature-resident connectedness and resident attitudes towards tourism: Evidence from a coastal destination of Bangladesh. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2025, 50, 100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Feng, Y.; Xiao, L.; Yang, Y. Study on residents’ tourism satisfaction in mountainous outdoor tourism destinations from a complexity perspective. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2025, 50, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Joo, D.; Gaither, C.J.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Sánchez, J.J.; Brooks, R.; Lee, D.K. Residents’ behavioral support for tourism in a burgeoning rural destination. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 48, 100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susila, I.; Dean, D.; Harismah, K.; Priyono, K.D.; Setyawan, A.A.; Maulana, H. Does interconnectivity matter? An integration model of agro-tourism development. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2024, 29, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, M.; Helming, K. Agricultural diversification across spatial levels—A contribution to resilience and sustainability? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 385, 109547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ismail, M.A.; Aminuddin, A. How has rural tourism influenced the sustainable development of traditional villages? A systematic literature review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, K. The power of saying “thank you”: Examining the effect of tourist gratitude expression on resident participation in value co-creation. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 61, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, M.; Wall, G. Behind the masks: Tourism and community in Sardinia. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabras, I.; Mount, M.P. How third places foster and shape community cohesion, economic development and social capital: The case of pubs in rural Ireland. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 55, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.S. How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: A simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 12, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Valdivia, C. Recreation and agroforestry: Examining new dimensions of multifunctionality in family farms. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.; Gillette, M.B.; Jernsand, E.M. Angling for change? A study of a Swedish public-private partnership for sustainable rural fisheries tourism. J. Rural. Stud. 2025, 119, 103729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfenstein, J.J. Biosecurity practices for specialized agritourism, organic, and artisan production dairy operations. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2025, 41, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khuadthong, B.; Imjai, N.; Yordudom, T.; Armandsiri, M.; Aujirapongpan, S. Shaping sustainable tourism behavior among elderly tourists: Roles of low carbon literacy and social-environmental awareness. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Yang, H.; Gan, D.; He, H.; Wang, S. Transforming tourist behavior: An integrated emotional and normative framework for promoting environmental intentions at eco-destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2025, 36, 100993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R. Ecotourism and the empowerment of local communities. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, K.T.; Nguyen, D.D.; Nguyen, D.V.; Nguyen, D.N.; Pham, H.T.L. Survey data on perceived sustainability and revisit intention of tourists to community-based tourism. Data Brief 2025, 61, 111773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, B. What is rural tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinus, K.; Boruff, B.; Nunez Picado, A. Authenticity, interaction, learning and location as curators of experiential agritourism. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 108, 103294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, K.; Iaquinto, B.L.; Azeredo, R. From tourists to essential workers: The multifaceted presence of backpackers in rural Queensland, Australia. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 112, 103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isetti, G.; Ferraretto, V.; Stawinoga, A.E.; Gruber, M.; DellaValle, N. Is caring about the environment enough for sustainable mobility? An exploratory case study from South Tyrol (Italy). Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 6, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windegger, F.; Scuttari, A.; Walder, M.; Erschbamer, G.; de Ra-chewiltz, M.; Corradini, P.; Weisel, Z.K.; Habicher, D.; Ghirardel-lo, L.; Wallnöfer, V.; et al. The Sustainable Tourism Observatory of South Tyrol (STOST)-Annual Progress Report–2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372861378_The_Sustainable_Tourism_Observatory_of_South_Tyrol_STOST_-_Annual_Progress_Report_-_2022#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Sidali, K.L.; Spitaler, A.; Schamel, G. Agritourism: A Hedonic Approach of Quality Tourism Indicators in South Tyrol. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palash, M.S.; Haque, A.B.M.M.; Rahman, M.W.; Nahiduzzaman, M.; Hossain, A. Economic well-being induced Women’s empowerment: Evidence from coastal fishing communities of Bangladesh. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knežević, M.; Pindžo, R.; Ćulić, M.; Kovačić, S.; Dunjić, M.; Vujko, A. Sustainable (re)development of tourism destinations as a pledge for the future—A case study from the Western Balkans. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2024, 56, 1564–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 2.669 | 53.370 | 53.370 | 1.918 | 38.356 | 38.356 | 2.483 | 49.666 | 49.666 |

| 2 | 1.922 | 38.430 | 91.800 | 2.452 | 49.050 | 87.406 | 1.887 | 37.740 | 87.406 |

| 3 | 0.249 | 4.985 | 96.786 | ||||||

| 4 | 0.103 | 2.061 | 98.847 | ||||||

| 5 | 0.058 | 1.153 | 100.000 | ||||||

| Factor(s) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Agroheritage Sustainability | Empowered Eco-Tourism | |

| Eco-motivated tourism | 0.117 | 0.900 |

| Sustainable agritourism | 0.950 | −0.069 |

| Tourism empowerment | 0.136 | 0.969 |

| Agricultural heritage | 0.987 | −0.068 |

| Community upliftment | 0.094 | 0.833 |

| Estimate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable Agritourism | <--- | F1 | 0.924 |

| Agricultural Heritage | <--- | F1 | 1.020 |

| Eco-Motivated Tourism | <--- | F2 | 0.838 |

| Tourism Empowerment | <--- | F2 | 0.978 |

| Community Upliftment | <--- | F2 | 0.907 |

| SH | Statement | Key Findings | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Agritourism drives sustainable land use, contributing to landscape conservation and eco-friendly agricultural practices. | Residents affirmed that agritourism prevents land abandonment, supports landscape maintenance, and promotes environmentally friendly farming. This is particularly valued in South Tyrol’s terraced vineyards and alpine pastures. | Confirmed |

| H2 | Agritourism preserves and enhances agricultural heritage, including traditional knowledge and cultural practices. | Residents emphasized tourism’s role in intergenerational knowledge transfer, safeguarding traditional farming methods and maintaining cultural rituals like haymaking, grape harvesting, and artisanal food production. | Confirmed |

| H3 | Residents are motivated to engage in tourism activities emphasizing environmental protection and ecological sustainability. | Respondents showed strong eco-motivation, favoring tourism models that minimize ecological degradation, which is crucial for South Tyrol’s sensitive alpine ecosystems. | Confirmed |

| H4 | Participation in agritourism enhances residents’ sense of empowerment in tourism development. | Residents reported increased confidence, decision-making capacity, and recognition through active engagement in agritourism, strengthening their agency in rural development. | Confirmed |

| H5 | Agritourism acts as a catalyst for community improvement, enhancing public services, infrastructure, and quality of life. | Tourism was perceived as a driver of community upliftment, motivating better cleanliness, hospitality services, and investments benefiting residents and visitors alike. | Confirmed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knežević, M.; Vujko, A.; Borovčanin, D. Community-Centered Farm-Based Hospitality in Agriculture: Fostering Rural Tourism, Well-Being, and Sustainability. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15151613

Knežević M, Vujko A, Borovčanin D. Community-Centered Farm-Based Hospitality in Agriculture: Fostering Rural Tourism, Well-Being, and Sustainability. Agriculture. 2025; 15(15):1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15151613

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnežević, Miroslav, Aleksandra Vujko, and Dušan Borovčanin. 2025. "Community-Centered Farm-Based Hospitality in Agriculture: Fostering Rural Tourism, Well-Being, and Sustainability" Agriculture 15, no. 15: 1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15151613

APA StyleKnežević, M., Vujko, A., & Borovčanin, D. (2025). Community-Centered Farm-Based Hospitality in Agriculture: Fostering Rural Tourism, Well-Being, and Sustainability. Agriculture, 15(15), 1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15151613