The Relationship between Geographical Indication Products and Farmers’ Incomes Based on Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Question Raised

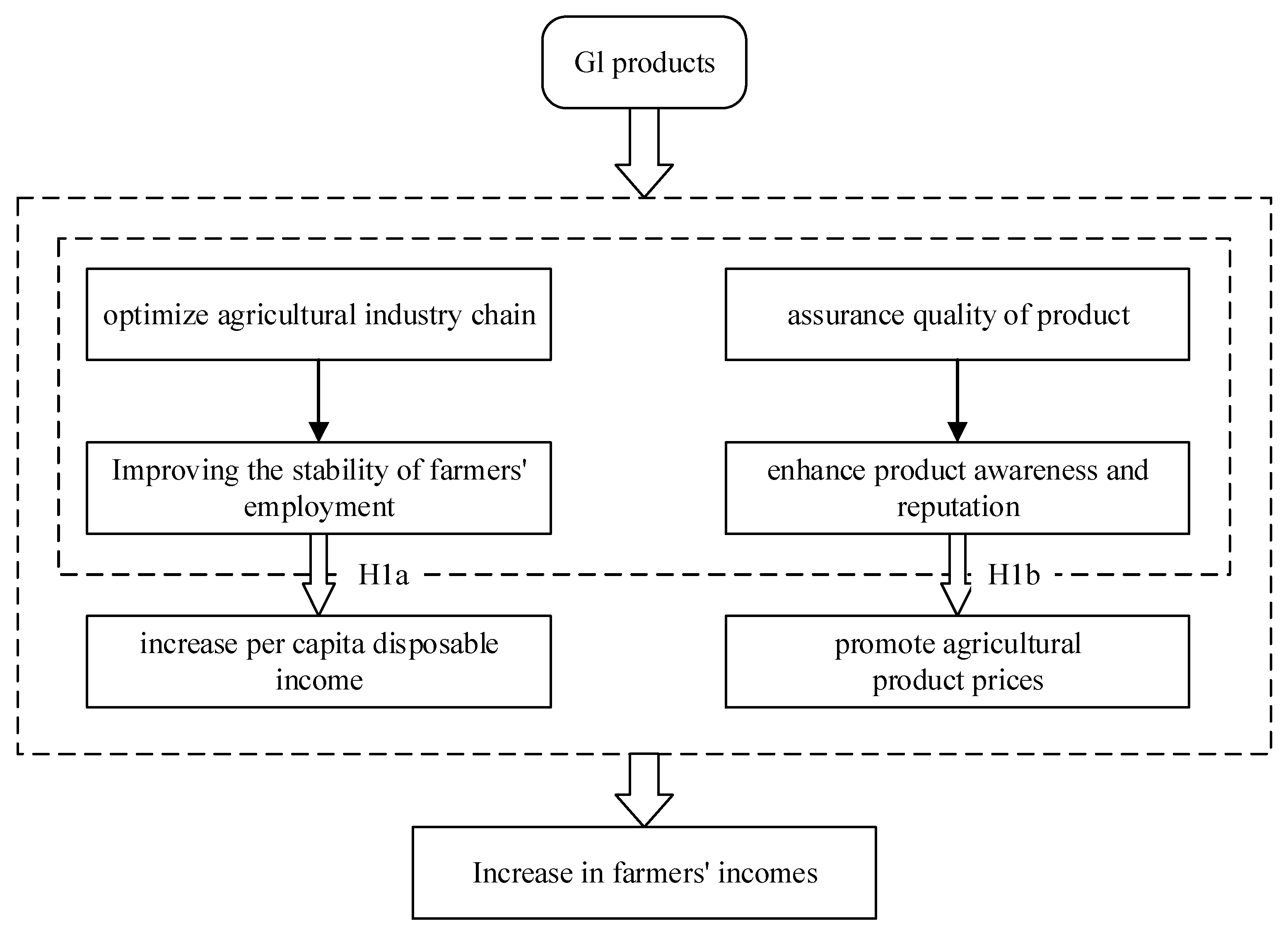

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Impact of GI Products on Farmers’ Income and Its Subdimensions

2.2. Moderating Factors Influencing the Relationship between GI Products and Farmer Incomes

2.2.1. Sources of Sample-Level Differences

2.2.2. Sources of Differences in Literature-Level Relationships

2.2.3. Sources of Differences in Methodological Approaches

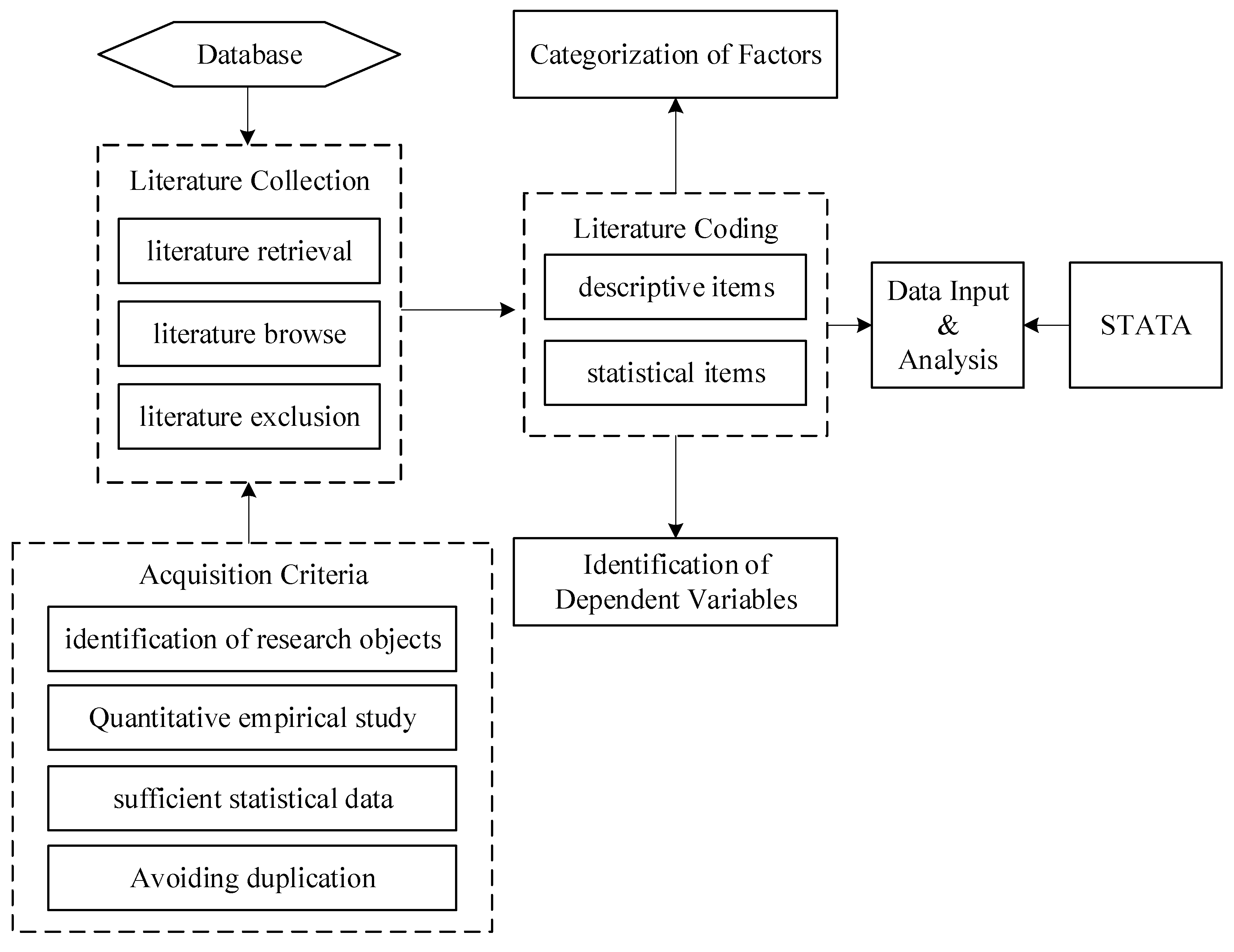

3. Methodology

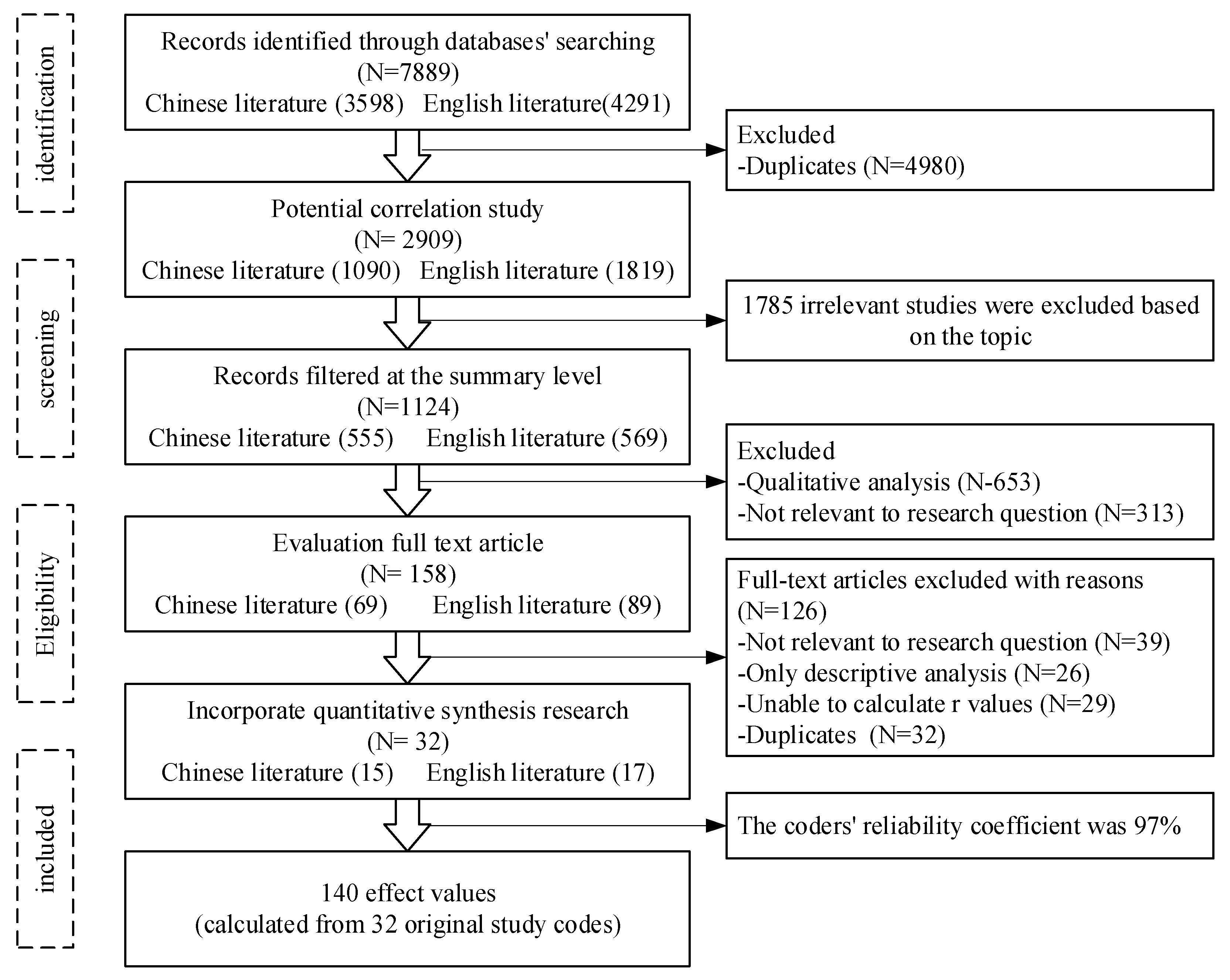

3.1. Literature Retrieval and Screening

3.2. Literature Encoding

4. Meta-Analysis Results

4.1. Publication Bias Test

4.2. Relationship between GI Products and Farmer Incomes

4.3. Moderation Analysis

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Research Implications

5.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ay, J.S.; Diallo, A.; Pham, H.V. Wine prices capitalization in vineyard prices of Côte-d’Or. Rev. Econ. 2023, 74, 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Glogovetan, A.I.; Dabija, D.C.; Fiore, M.; Pocol, C.B. Consumer Perception and Understanding of European Union Quality Schemes: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.A.; Melts, I.; Mohan, G.; Rani, C.R.; Pawar, V.; Singh, V.; Choubey, M.; Vashishtha, T.; Suresh, A.; Bhattarai, M. Economic Impact of Organic Agriculture: Evidence from a Pan-India Survey. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal-Arowolo, A. Geographical indications and cultural artworks in Nigeria: A cue from other jurisdictions. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2019, 22, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L. Adapting the designated area of geographical indications to climate change. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 105, 1088–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubrock, P.J.; Oficialdegui, F.J.; Zeng, Y.W.; Patoka, J.; Yeo, D.C.J.; Kouba, A. The redclaw crayfish: A prominent aquaculture species with invasive potential in tropical and subtropical biodiversity hotspots. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 1488–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.A. Electronic national agricultural markets: The way forward. Curr. Sci. 2018, 115, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deconinck, K.; Swinnen, J. The Size of Terroir: A Theoretical Note on Economics and Politics of Geographical Indications. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 72, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curzi, D.; Huysmans, M. The Impact of Protecting EU Geographical Indications in Trade Agreements JEL codes. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 104, 364–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besah-Adanu, C.; Bosselmann, A.S.; Hansted, L.; Kwapong, P.K. Food origin labels in Ghana: Finding inspiration in the European geographical indications system on honey. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2019, 22, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, C.; Fournier, S. Can Geographical Indications Modernize Indonesian and Vietnamese Agriculture? Analyzing the Role of National and Local Governments and Producers’ Strategies. World Dev. 2017, 98, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata-Sena, M.; Castro-Carvalho, B.M.; Nunes, S.; Amaral, B.; Silva, P. The terroir of Port wine: Two hundred and sixty years of history. Food Chem. 2018, 257, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellegers, P. Food security vulnerability due to trade dependencies on Russia and Ukraine. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oke, E.K. Rethinking Nigerian geographical indications law. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2022, 25, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselli, L.; Giannoccaro, G.; Carlucci, D. EU Quality Labels in the Italian Olive Oil Market: How Much Overlap is There Between Geographical Indication and Organic Production? J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 784–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.C. Product Attribute Saliency and Region of Origin: Some Empirical Evidence from Portugal Product. In Proceedings of the 99th Seminar of the EAAE, Copenhagen, Denmark, 24–27 August 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X. Geographical indication, agricultural development and the alleviation of rural relative poverty. Sustain. Dev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.Y.; Feng, Y.; Wei, H. Does Geographical Indication Certification Increase the Technical Complexity of Export Agricultural Products? Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 892632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.W.; Dong, Y.G. Comparative study on the geographical indication protection between China and the European Union-From the perspective of the China-EU Geographical Indications Agreement. Agric. Econ.-Zemed. Ekon. 2023, 69, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, M. Geographical Indications at the Crossroads of Trade, Development and Culture: Focus on Asia-Pacific. Queen Mary J. Intellect. Prop. 2019, 9, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeck, C.; Meloni, G.; Swinnen, J. The Value of Terroir: A Historical Analysis of the Bordeaux and Champagne Geographical Indications. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2019, 41, 598–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P.; Michler, J.D.; Josephson, A. Foreign geographical indications, consumer preferences, and the domestic market for cheese. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2019, 41, 370–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.J.; Fang, K.X.; Ding, Z.A.; Wu, J.X.; Lin, J.Z.; Xu, D.M.; Zhong, J.S.; Xia, F.; Feng, J.H.; Shen, G.P. Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis Revealed the Difference of Component and Geographical Indication Markers of Panax notoginseng in Different Production Areas. Foods 2023, 12, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ay, J.S. The Informational Content of Geographical Indications. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 103, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.L.; Le, V.A. Diffusion of Geographical Indication Law in Vietnam: “Journey To The West”. IIC-Int. Rev. Intellect. Prop. Compet. Law 2023, 54, 176–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Abbas, S. The relationship between symbolic agricultural products and agricultural economic development based on numerical analysis. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 4971437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosse, S.; Olders, P.; Boonstra, W.J. Why are geographical indications unevenly distributed over Europe? Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Zhao, P.; Qi, Y.; Lu, Y. The spatial heterogeneity characteristics and the influencing factors of the Agro-product Geographical Indication Brands. Res. Agric. Mod. 2021, 42, 1126–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Lubinga, M.H.; Ngqangweni, S.; Walt, S.V.D.; Potelwa, Y.; Ntshangase, T. Geographical indications in the wine industry: Does it matter for South Africa? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, K.; Balling, R.; Chilla, T.; Lindermayer, H. European Integration Processes in the EU GI System-A Long-Term Review of EU Regulation for GIs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorgho, Z.; Larue, B. Do geographical indications really increase trade? a conceptual framework and empirics. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2017, 16, 20170010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakoufaris, H.; Gocci, A. Geographical Indications and Sustainable Development: An Assessment of Four Categories of Products from the Fruit and Vegetable Sector of the Eu. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 39, 7112–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittersum. The Role of Region of Origin in Consumer Decision-Making and Choice; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y. Geographical Indication, Agricultural Products Export and Urban-Rural Income Gap. Agriculture 2023, 13, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraizoz, B.; Bardají, I.; Rapún, M. Do ‘protected geographical indications’ (pgi)-certified farms perform better? The case of beef farms in spain. Outlook Agric. 2011, 40, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-J. Spatial distribution characteristics of geographical indications and brand spillover effects: An empirical study based on the geographical indication data of 3 departments in China. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 37, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sgroi, F. Territorial development models: A new strategic vision to analyze the relationship between the environment, public goods and geographical indications. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwakaje, S.J. Protection of geographical indications and cross-border trade: A survey of legal and regulatory frameworks in East Africa. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2022, 25, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntakiyisumba, E.; Lee, S.; Won, G. Identification of risk profiles for Salmonella prevalence in pig supply chains in South Korea using meta-analysis and a quantitative microbial risk assessment model. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 112999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdin, A.; Dokhelar, T.; Bord, S.; Van Halder, I.; Stemmelen, A.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Jactel, H. Forests harbor more ticks than other habitats: A meta-analysis. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 541, 121081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneller, E. EU-Australia FTA: Challenges and potential points of convergence for negotiations in geographical indications. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2020, 23, 546–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coggins, S.; Malone, B.P.; Stockmann, U.; Possell, M.; McBratney, A.B. Towards meaningful geographical indications: Validating terroirs on a 200 km2 scale in Australia’s lower Hunter Valley. Geoderma Reg. 2019, 16, e00209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, T.D. Wheat from chaff: Meta-analysis as quantitative literature review. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, T. Distorted Gravity: The Intensive and Extensive Margins of International Trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008, 98, 1707–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huysmans, M.; Noord, D.V. The Market for Lemons from Sorrento and Gouda from Holland: Do Geographical Indications Certify Origin and Quality? USE Working Paper Series; U.S.E. Research Institute: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Qie, H.; Chen, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z. Evaluating the Impact of Agricultural Product Geographical Indication Program on Rural Income: A Case Study of the Yangtze River Delta Region in China. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bom, P.R.D.; Rachinger, H. A kinked meta-regression model for publication bias correction. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 10, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringquiste. Meta-Analysis for Public Management Policy; John Wiley: NewYork, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, R.J.; Thompson, S.G. Detecting and describing heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, P.R.; Grote, U. Does Geographical Indication (GI) increase producer welfare? A case study of Basmati rice in Northern India. In Proceedings of the ISEE Conference on Advancing Sustainability at the Time of Crisis, Oldenburg–Bremen, Germany, 22–25 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gignac, G.E.; Szodorai, E.T. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, J.; Ge, L.; Hu, W.; Ban, Q. Do Geographical Indication Products Promote the Growth of the Agricultural Economy? An Empirical Study Based on Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinha, D.; Faustino, H.; Nunes, C.; Sales, H.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J. Bioactive Compounds of Portuguese Fruits with PDO and PGI. Foods 2023, 12, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leufkens, D. Eu’s regulation of geographical indications and their effects on trade flows. Ger. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 66, 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.S.K.; Wang, L.T.; Blatz, M.B. Efficacy of adhesive strategies for restorative dentistry: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials over 12 months of follow-up. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2023, 67, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Kong, F.Z.; Peng, H.; Dong, S.F.; Gao, W.Y.; Zhang, G.T. Combing machine learning and elemental profiling for geographical authentication of Chinese Geographical Indication (GI) rice. Npj Sci. Food 2021, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida-Garcia, F.; Lago-Olveira, S.; Rebolledo-Leiva, R.; Gonzalez-Garcia, S.; Teresa Moreira, M.; Ruiz-Nogueiras, B.; Pereira-Lorenzo, S. Growing Triticum aestivum Landraces in Rotation with Lupinus albus and Fallow Reduces Soil Depletion and Minimises the Use of Chemical Fertilisers. Agriculture 2022, 12, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Authors | Year | Method | Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wang Yan | 2022 | DID | Chilli | Net benefits to growers | China |

| 2 | Rao Huacheng | 2022 | Tobit regression | GI Protection | Poverty incidence | China |

| 3 | Liu Peng | 2022 | Multiple linear regression | GI Protection | Rural–urban income gap | China |

| 4 | Chen Chao | 2021 | OLS | Fruit | Income from fruit farmer operations | China |

| 5 | Wan Huaqiang | 2021 | OLS | GI Protection | Farmers’ per capita income | China |

| 6 | Dong Yaning | 2021 | OLS | GI Protection | Level of growth in agricultural income | China |

| 7 | Chen Xi | 2020 | OLS | GI Protection | Rural–urban income gap | China |

| 8 | Ji Xinyu | 2020 | OLS | GI Protection | Per capita disposable income | China |

| 9 | Yu Yanli | 2021 | Endogenous transformation model | GI Protection | Income | China |

| 10 | Yang Liuyang | 2019 | Linear regression | GI Protection | Costs | China |

| 11 | Lu Zhaoyang | 2018 | OLS | GI Protection | Solvency of enterprises | China |

| 12 | Tai Xiujun | 2017 | OLS | GI Protection | Farmers’ per capita income | China |

| 13 | Miao Chenglin | 2017 | OLS | GI Registrations | Gross agricultural output per capita | China |

| 14 | Zhao Jinli | 2014 | Joint regression model | GI Registrations | Farmers’ per capita income | China |

| 15 | Zhao Su | 2015 | OLS | GI Registrations | Farmers’ per capita income | China |

| 16 | Liu Huajun | 2015 | OLS | GI Registrations | Farmers’ per capita income | China |

| 17 | Zhan Huibing | 2012 | OLS | GI Protection | Income | China |

| 18 | Sihui Zhang | 2023 | SDM | GI Registrations | Urban–rural income gap | China |

| 19 | Concetta Cardillo | 2023 | OLS | GI Protection | Income | Italy |

| 20 | Celso Lopes | 2022 | OLS | GI Registrations | Income | Portugal |

| 21 | Luigi Roselli | 2016 | OLS | GI Protection | Price premium | USA |

| 22 | Luigi Roselli | 2016 | Price model | Cheese | Price premium | France |

| 23 | Wen, Hui | 2022 | Multiple regression | GI Protection | Farmers’ income | China |

| 24 | Daniel HassanTSE | 2011 | demand models | GI Protection | Income elasticity | USA |

| 25 | Pradyot R. Jena | 2010 | Random parameter logit (RPL) model | Basmati rice | Producer welfare | India |

| 26 | Seccia, A | 2017 | Non-regression methods | GI Protection | Agricultural product price | France |

| 27 | Santos, J | 2005 | Non-regression methods | GI Protection | Agricultural product price | Brazil |

| 28 | Zhang Mier | 2022 | Regression methods | GI Protection | Agricultural product price | China |

| 29 | Li Zhaopan | 2021 | Non-regression methods | GI Protection | Agricultural product price | China |

| 30 | Yang Liuyang | 2019 | Regression methods | GI Protection | Agricultural product price | China |

| 31 | Peng Fung-lan | 2022 | Non-regression methods | GI Protection | Agricultural product price | China |

| 32 | Pembebe | 2019 | Regression methods | GI Protection | Agricultural product price | China |

| Category | Sample Size | Fail-Safe Number |

|---|---|---|

| K | N | |

| Overall | 99 | 1218 |

| Per capita disposable income | 42 | 3010 |

| Increase in agricultural commodity prices | 35 | 2581 |

| Variable | Heterogeneity Test | Effects Model | Correlation Strength | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Df | p Value | I2 | Q | z | Variance | Point Estimation | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||

| Overall | 87 | 0.000 | 99.83 | 50,181.920 | 2.780 | 1.317 | 0.348 | 0.104 | 0.540 | High |

| Per capita disposable income | 41 | 0.000 | 99.91 | 44,541.550 | 2.270 | 1.349 | 0.389 | 0.056 | 0.644 | High |

| Increase in agricultural commodity prices | 34 | 0.009 | 99.00 | 2094.120 | 11.640 | 0.004 | 0.255 | 0.214 | 0.296 | Moderate |

| Variable | Category | k | 95%CI | Heterogeneity Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation Value | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Q | Df | p Value | |||

| Country | China | 64 | 0.412 | 0.304 | 0.509 | 1419.130 | 63 | 0.000 |

| Other countries | 24 | 0.208 | −0.122 | 0.497 | 19,441.670 | 23 | 0.000 | |

| Sampling region | Nationwide | 39 | 0.246 | 0.016 | 0.477 | 20,053.990 | 38 | 0.000 |

| Region | 49 | 0.455 | 0.336 | 0.560 | 1290.830 | 48 | 0.000 | |

| Sample type | Specific GI products | 28 | 0.400 | 0.259 | 0.525 | 1531.410 | 27 | 0.000 |

| Total volume of GI products | 60 | 0.309 | 0.068 | 0.516 | 23,163.510 | 59 | 0.000 | |

| Journal type | Journal | 13 | 0.562 | 0.278 | 0.756 | 396.590 | 12 | 0.000 |

| Dissertation | 75 | 0.310 | 0.062 | 0.521 | 43,464.300 | 74 | 0.000 | |

| Journal quality | High | 11 | 0.630 | 0.469 | 0.750 | 736.080 | 10 | 0.000 |

| Low | 64 | 0.238 | 0.023 | 0.432 | 20,809.670 | 63 | 0.000 | |

| Publication year | Before 2015 | 13 | 0.635 | 0.394 | 0.794 | 758.110 | 12 | 0.000 |

| 2015 and after 2015 | 75 | 0.275 | 0.028 | 0.491 | 40,273.560 | 74 | 0.000 | |

| Research method | Multiple linear regression | 54 | 0.329 | 0.027 | 0.576 | 41,788.620 | 53 | 0.000 |

| Others | 34 | 0.360 | 0.211 | 0.492 | 807.390 | 33 | 0.000 | |

| Data type | Section | 49 | 0.332 | 0.185 | 0.465 | 1133.020 | 48 | 0.000 |

| Panel | 39 | 0.359 | 0.026 | 0.620 | 38,458.480 | 38 | 0.000 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, C.; Ban, Q.; Ge, L.; Qi, L.; Fan, C. The Relationship between Geographical Indication Products and Farmers’ Incomes Based on Meta-Analysis. Agriculture 2024, 14, 798. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14060798

Li C, Ban Q, Ge L, Qi L, Fan C. The Relationship between Geographical Indication Products and Farmers’ Incomes Based on Meta-Analysis. Agriculture. 2024; 14(6):798. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14060798

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Chunyan, Qi Ban, Lanqing Ge, Liwen Qi, and Chenchen Fan. 2024. "The Relationship between Geographical Indication Products and Farmers’ Incomes Based on Meta-Analysis" Agriculture 14, no. 6: 798. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14060798

APA StyleLi, C., Ban, Q., Ge, L., Qi, L., & Fan, C. (2024). The Relationship between Geographical Indication Products and Farmers’ Incomes Based on Meta-Analysis. Agriculture, 14(6), 798. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14060798