1. Introduction

Plastic film mulching cultivation technology increases temperature and moisture, saves water and boosts drought resistance, reduces soil salinity, and improves crop yield, all of which are of great significance to agricultural development [

1,

2]. However, agricultural plastic film is extremely difficult to degrade under natural conditions [

3,

4], resulting in the transformation of a farmland “white revolution” into “white pollution”. Therefore, it is urgent to control the current situation of residual film pollution [

5,

6,

7,

8]. In China, the problem of residual film pollution in cotton fields is mainly treated by residual film recycling machines. The specific models are divided into spring-tooth row, roller, air-suction, follow-up, clamping, etc. [

9].

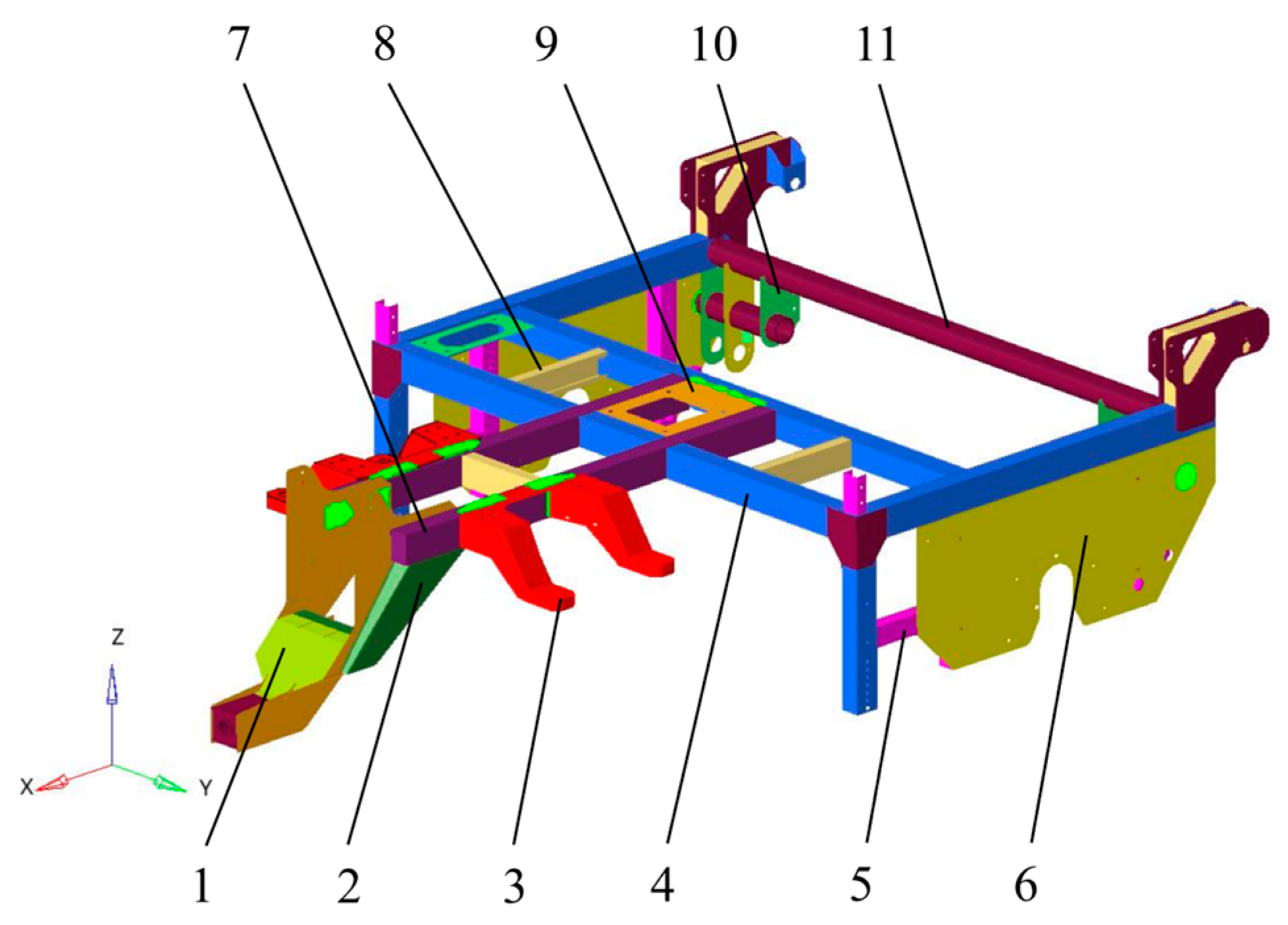

As the main bearing part of the straw-crushing residual film recycling machine, the frame easily bears the extreme load generated by the system and the alternating load generated by other components when it works at high speed without stopping in a complex field terrain [

10]. At the same time, there will be related vibration characteristics problems when subjected to vibration, mainly including resonance frequency, natural frequency, damping and amplitude, etc. [

11,

12]. Research on the vibration characteristics of residual film recycling machines is challenging yet important. To a certain extent, solving the resonance problem can reduce the energy loss of the machine, improve the operation efficiency, and achieve cost reduction and income increase. However, studying the vibration characteristics of the frame system of the straw-crushing and residual film recycling machine with the main purpose of reducing weight and noise is important because it provides a theoretical basis for the in-depth study of the vibration characteristics of the subsequent agricultural machinery.

Some scholars have carried out systematic vibration tests and modal analyses on various types of agricultural machinery and equipment to avoid the resonance problem and reduce the violent vibration phenomenon of the whole machine under complex working conditions and improve driving comfort. Arkadiusz et al. [

13] explored the application of accelerometer sensors in the manufacture of low-cost systems for monitoring the vibration of agricultural machinery (such as rotary grass spreaders). Sensors provide useful data on equipment health for agricultural machinery to improve the durability of such machinery. Liu Jiajie et al. [

14] optimized the frame design to avoid reducing the stripping machine’s bearing capacity at the working time. Gao et al. [

15] explored the vibration characteristics of the chassis frame of the combined harvester by combining NX Nastran with the modal test. Adam et al. [

16] collected the vibration signals of the tractor base and the driver’s thigh under the driving condition and the field operation condition. It was found that the vibration energy of the driver in the vertical direction was larger during the field operation, and the seat resonance frequency was 2–3 Hz. Jahanbakhshi et al. [

17] conducted a working condition vibration test on the machine to improve the driver’s driving comfort of the combined harvester during operation. Chowdhury et al. [

18] explored the vibration characteristics of a radish harvester during field operation to analyze the causes of severe vibration.

At present, there are few studies on the resonance problem and related vibration characteristics of the straw-crushing residual film recycling machine. Therefore, this paper takes the vibration problem of the 1-MSD straw-crushing residual film recovery machine in the field as the background and aims to avoid resonance of the machine based on the relationship between the external excitation of the straw-crushing residual film recovery machine, and its frame mode, sensitivity and grey correlation analyses were combined to analyze the vibration characteristics and optimize the design of the frame of the 1-MSD straw-crushing and residual film recycling machine, providing a theoretical reference for the vibration reduction optimization of the subsequent frame of this kind of machine. To this end, this paper mainly carries out the following work: (1) Establishing the rack model and solving its modal parameters by the finite element method; (2) Extracting the modal parameters of the rack by modal test and comparing it with the results of the finite element method; (3) Analyzing the relationship between the external excitation and the natural frequency of the rack, obtaining the optimized components through sensitivity analysis, establishing the optimization mathematical model and solving; (4) Establishing the optimization scheme based on grey correlation degree and finding the optimal result.

2. Machine Composition and Working Principle

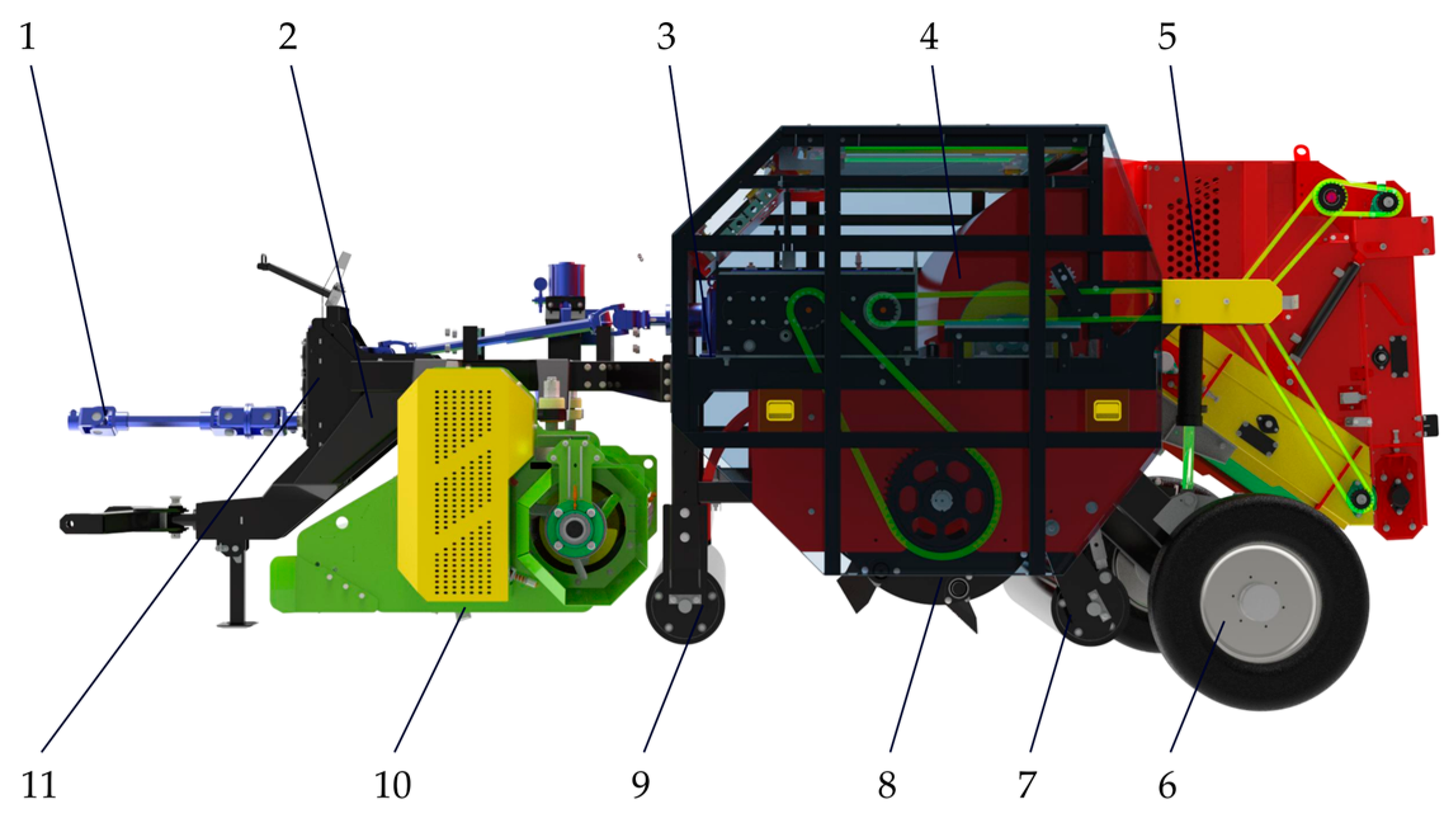

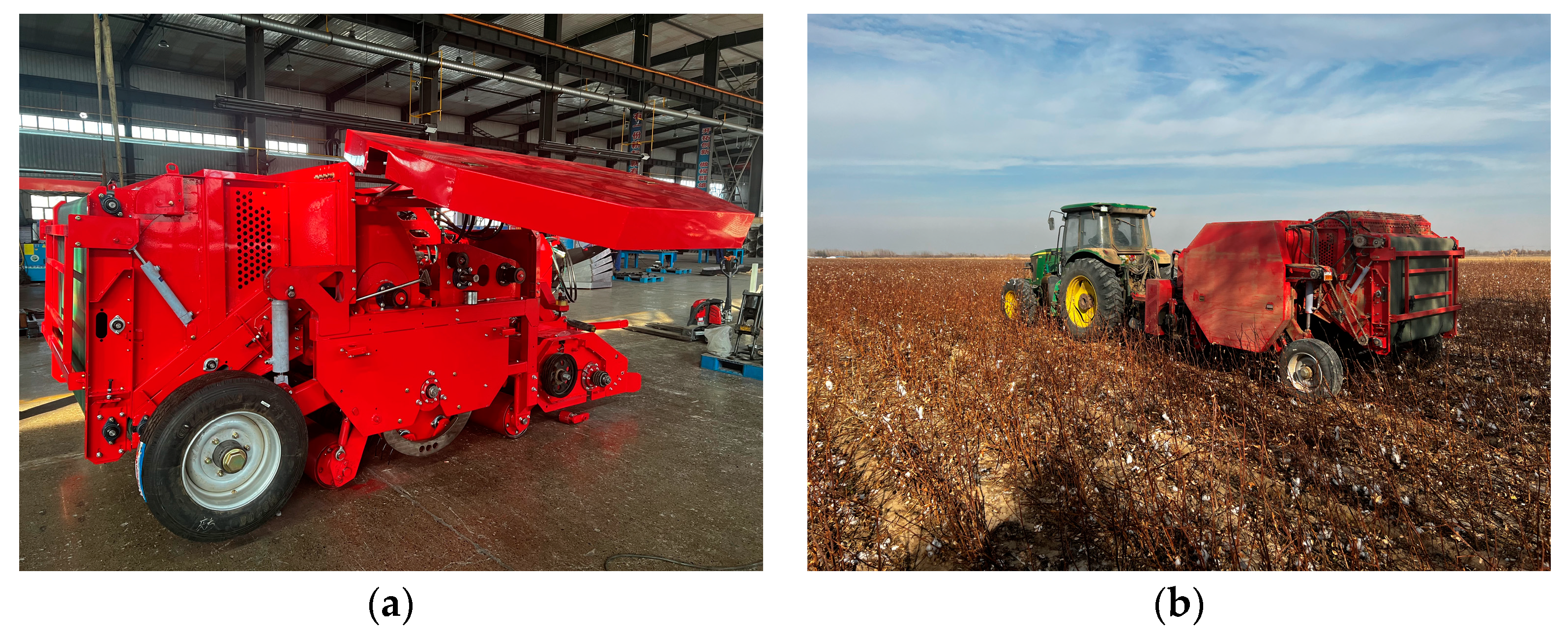

The 1-MSD straw-crushing and residual film recycling machine is shown in

Figure 1. The machine is composed of a frame, a straw-crushing and returning device, a film-lifting mechanism, a film-removing mechanism, and a packaging mechanism.

When the machine works, the tractor pulls the straw-crushing residual film recycling machine along the cotton-planting line. The straw-crushing and returning device cuts the straw and evenly scatters the broken straw into the field. Then, the residual film is picked up by the film-raising mechanism and sent to the film-removal mechanism. Then, the film removal mechanism in the air delivery feeds it to the packaging mechanism. The packaging mechanism continuously accumulates and rubs the residual film, and the diameter of the residual film is transformed from small to large until the film bag is formed. Finally, the hydraulic system opens the packaging warehouse door, and the film bag is discharged into the field, completing the full recovery of straw-crushing residual film.

When working in the field, the frame is the main bearing part of the straw-crushing residual film recycling machine, and its bearing capacity is the key factor affecting the quality of straw-returning and residual film recycling. At the same time, the material, size and structure of the frame are important factors affecting its modal [

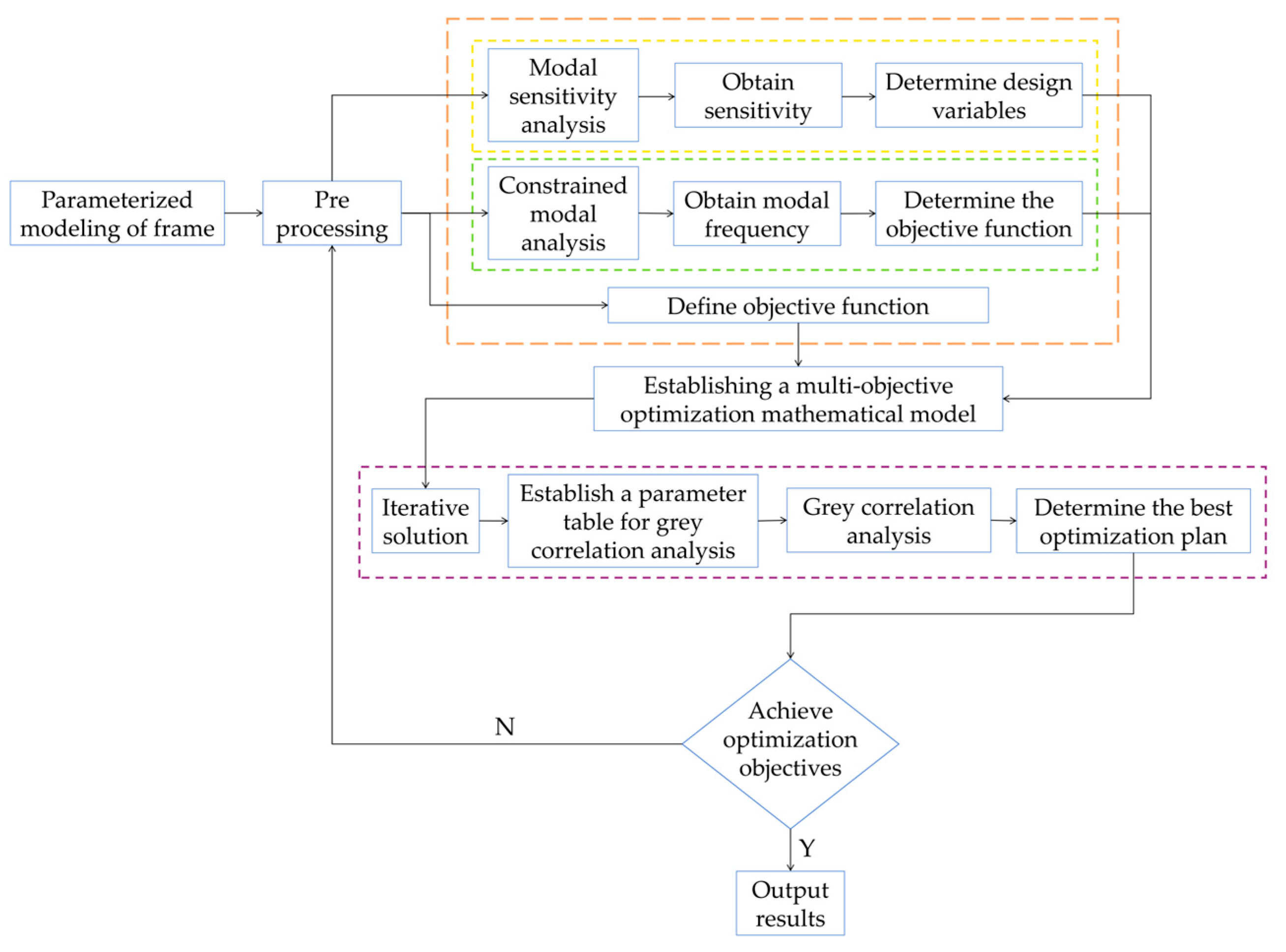

19]. The optimization process of this paper is shown in

Figure 2.

4. Modal Test Based on PolyMax Method

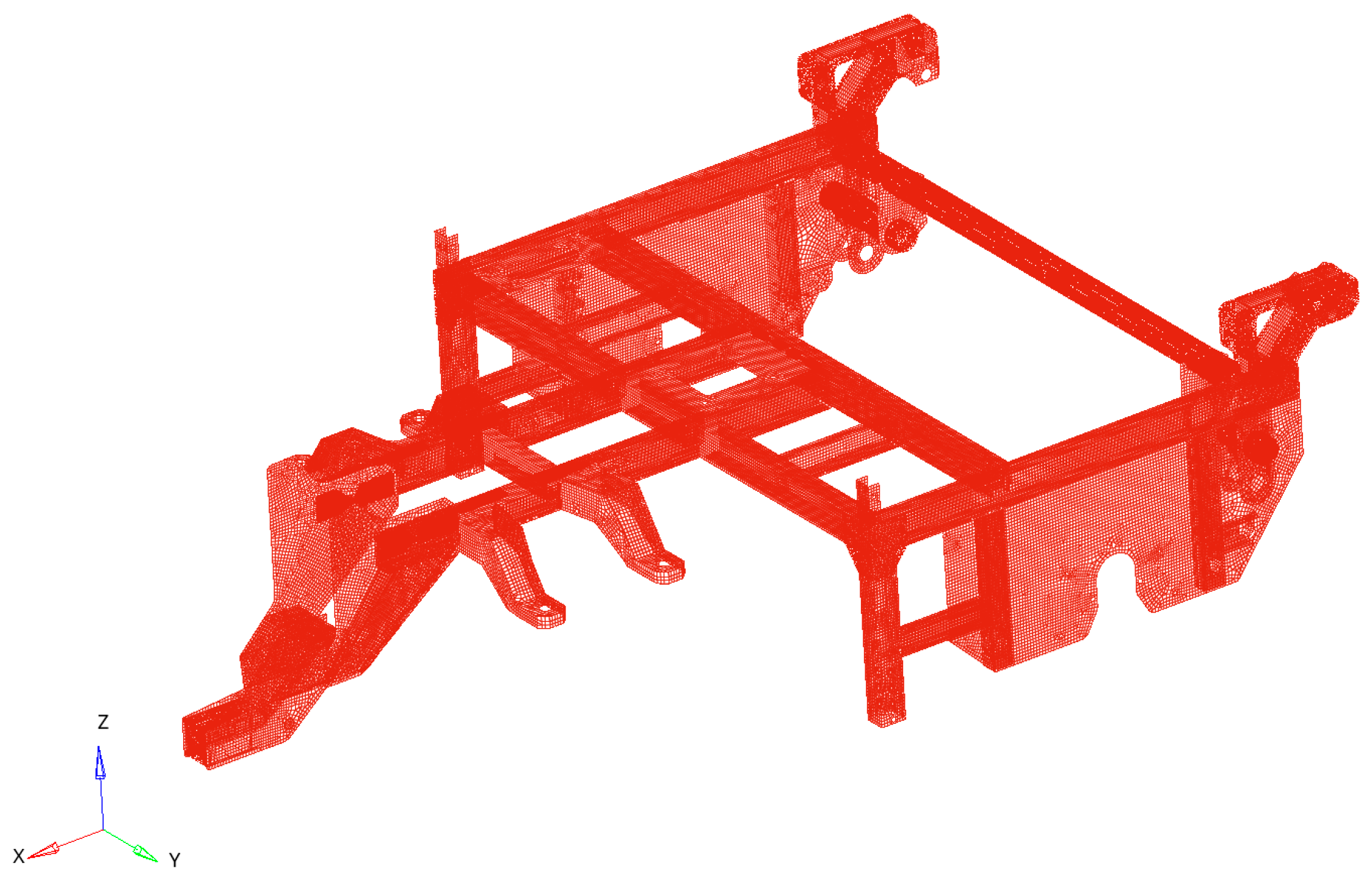

Verification of the accuracy of the finite element modal analysis method requires a comparison of the modal results of the modal test of the frame to provide theoretical support for the subsequent optimization design of the frame.

4.1. Basic Principle and Mathematical Model of PolyMax Modal Parameter Identification

The modal test is used to obtain accurate modal parameters of the test object through the structural modal parameter identification method. The structural modal parameter identification method can be divided into the frequency, time, and time–frequency domain methods [

22,

23]. The frequency domain method is used to identify the modal parameters through the frequency response function (FRF) or the structural transfer function. The modal parameter identification is conducted using the time domain method through the actual measurement signal. The time–frequency domain method is used mostly for modal parameter identification of nonlinear and unstable signals. The PolyMax modal parameter identification method can be classified under the frequency domain method. It is a modal parameter identification method that combines the advantages of the least squares complex frequency domain method (LSCF) and the least squares complex exponential method (LSCE) [

24]. The discrete time–frequency domain model can avoid the numerical ill-posed problem well, and the obtained modal frequency, modal participation factor, and damping ratio (strong and weak damping applications are ideal) have high accuracy. The results of the steady-state diagram have the advantages of clear and easy extraction.

The dynamic differential equation of the frame is established according to the theory of vibration and described as follows:

In the formulation, M, C, and K are the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices of the system, respectively. x, ẋ, ẍ, are the displacement, velocity, and acceleration of the system nodes, respectively; and p is the node equivalent load column matrix.

The characteristic equation of Equation (1) is as follows:

In the formula, i and ω denote the phase and the characteristic frequency, respectively.

For the modal analysis of the frame, the eigenvalues and corresponding eigenvectors are obtained by solving Equation (2), which corresponds to the natural frequencies and modes of the modal results, respectively. The final analysis object of this paper is the frequency domain signal. The Laplace transform of the system differential Equation (1) is carried out to realize the transformation from the time to the frequency domain, which is described as follows:

The inverse matrix of the system matrix

B is solved, and the system displacement frequency response function matrix

H is obtained and described as follows:

where

B* and

|B| denote the adjoint matrix and determinant of the system matrix

B, respectively.

The frequency response function of the

ith response vector and the

jth reference vector is denoted by

H(

jω), which is described as follows:

In the formula, m represents the number of dynamic response modes in the analyzed bandwidth of the structure; Bk and are mutually conjugate matrices, which represent the kth-order modal vector; and λk denotes the eigenvalue of order k.

4.2. Modal Test Scheme

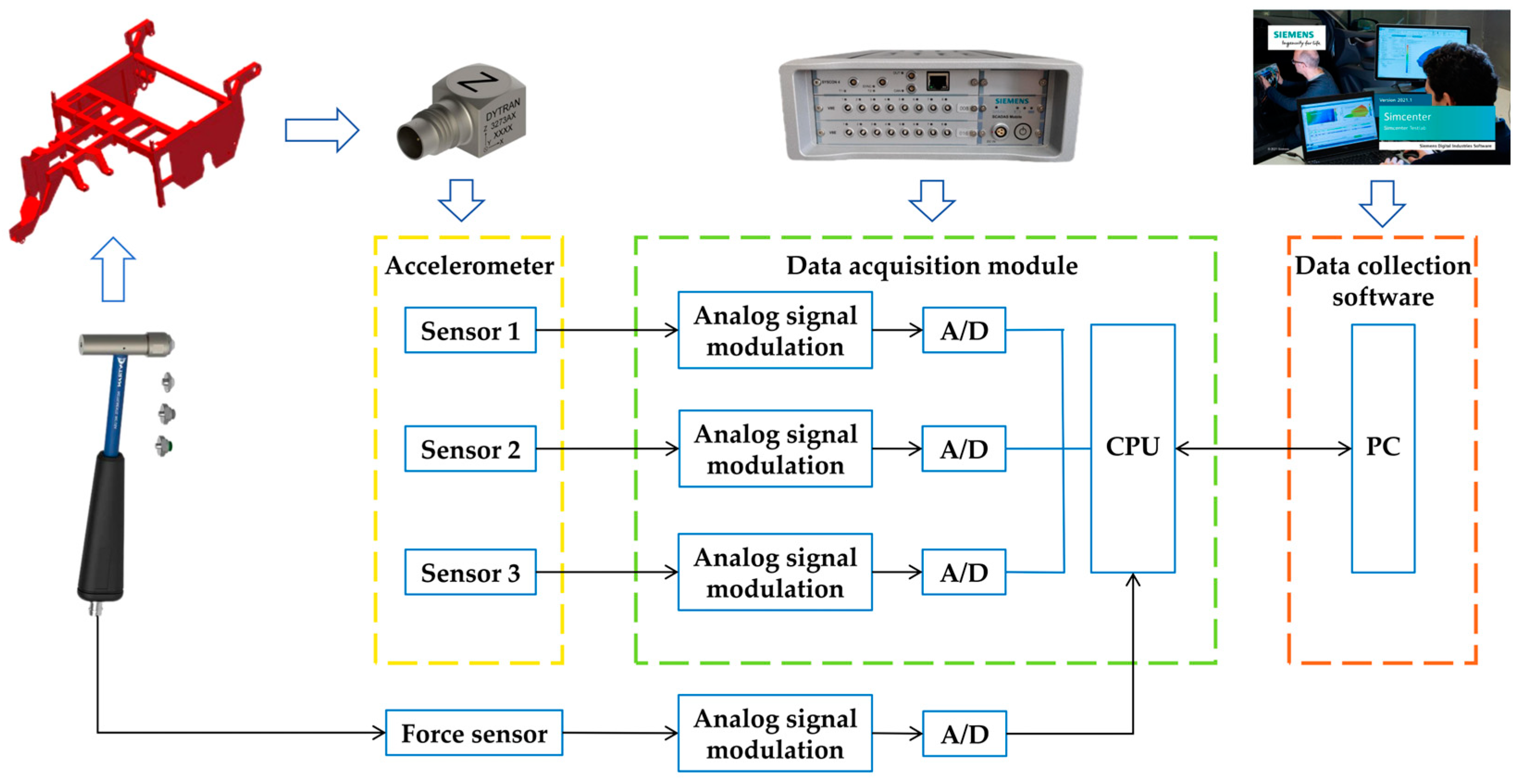

The modal test data acquisition system (

Figure 6) in this paper comprises an impact hammer, a three-axis acceleration sensor, a SCADAS data acquisition analyzer, and LMS Test-lab 2021 signal processing and analysis software. The impact hammer is applied to the frame pulse excitation, and the analog signal is fed back to the data acquisition analyzer through the three-axis acceleration sensor. The data acquisition software processes the signal and obtains the frequency response function. The details of the test equipment are shown in

Table 2.

The hammer has three materials: rubber, nylon, and aluminum. After the hammer striking test, the aluminum hammer had the best response effect, and was thus selected for the test.

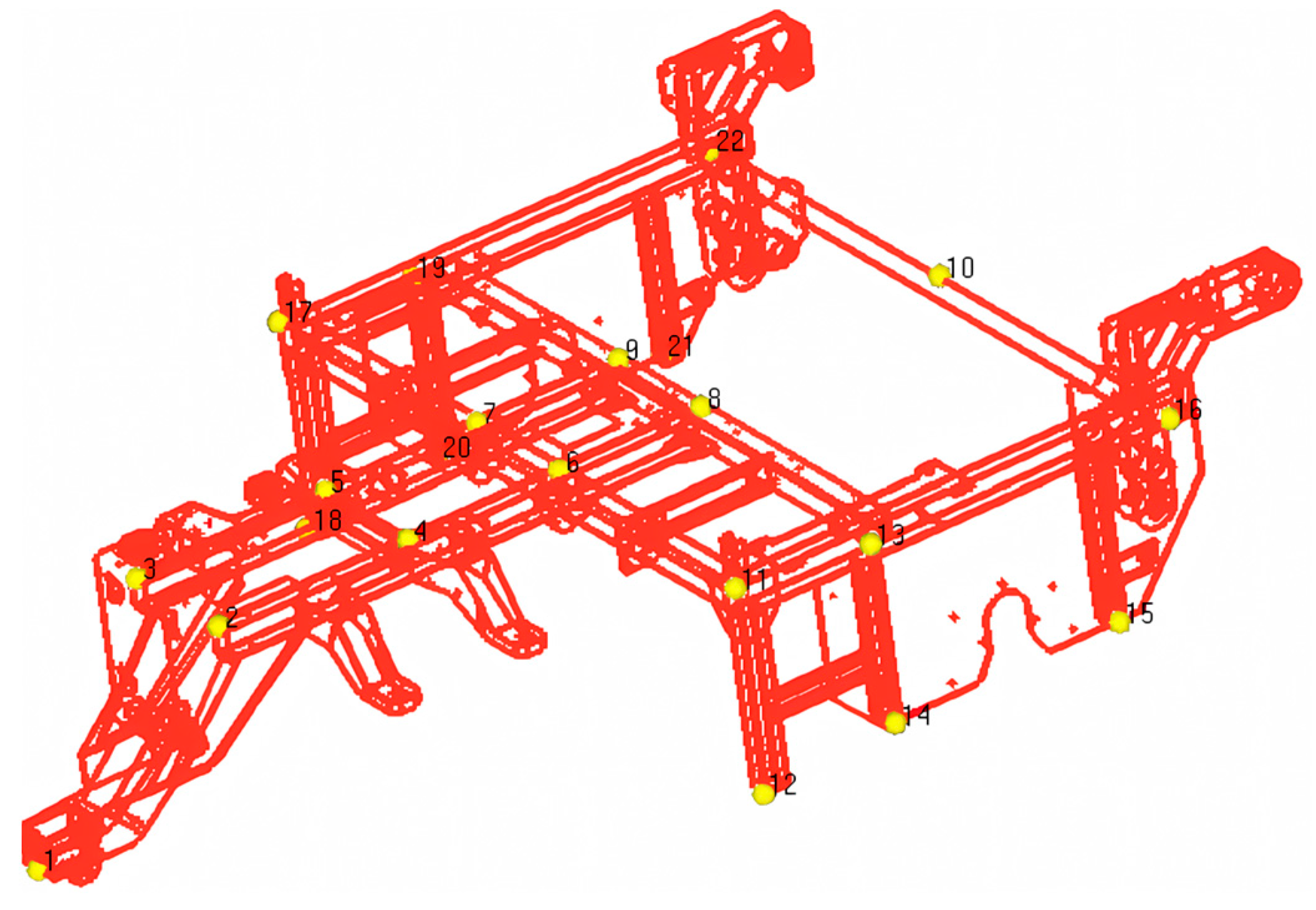

The overall structure of the frame is symmetrical, and the frame is divided into two equal parts along the center line. A total of 22 measuring points are arranged (as shown in

Figure 7) to ensure that the measuring points can reflect the shape of the frame structure and ensure that the modal vibration mode of the frame can be fully described. Because the reference point (fixed excitation to place the sensor point) should be able to avoid the node and be easily excited, measuring points 1, 11, and 22 are selected as the reference points. Each reference point is set with a three-axis acceleration sensor, and the remaining points are response points.

4.3. Test Steps

- (1)

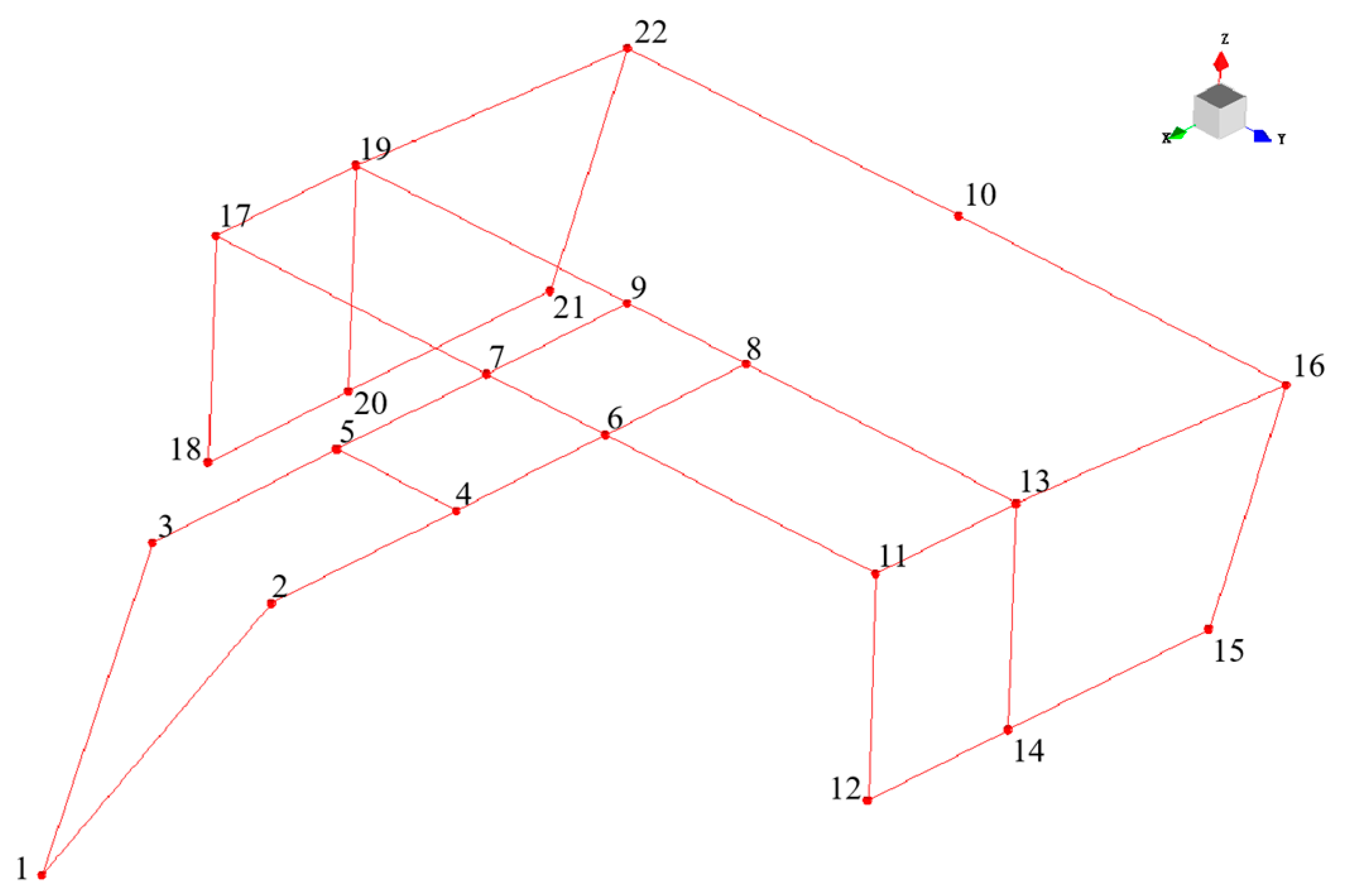

Build a geometric model:

The geometric model of the frame is established in LMS Test-Lab 2021 software based on the layout scheme of the measuring points (

Figure 8).

- (2)

Site layout:

The modal test site is arranged, and the frame’s suspension mode and equipment debugging are determined. The modal test was carried out separately in the open hoisting operation area to avoid being affected by other workshop operations (welding, assembly hoisting, etc.) during the test and to ensure that the results have a high signal-to-noise ratio. The gantry crane device is used to lift the frame so that it is in a balanced suspension state (about 20 cm vertical distance from the ground). The horizontal position of the frame is artificially adjusted until the center line of the frame is parallel to the standard operation line of the site. Finally, the data acquisition system is debugged. The specific site layout is shown in

Figure 9.

- (3)

Test process:

The multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) method [

25] was used to test the modal of the frame, and the spectral average method was used to sequentially move the hammer to the X, Y, Z direction of each measuring point five times. The effective excitation ensures that the final FRF function is consistent and that the modal order is complete.

4.4. Analysis of Modal Test Results

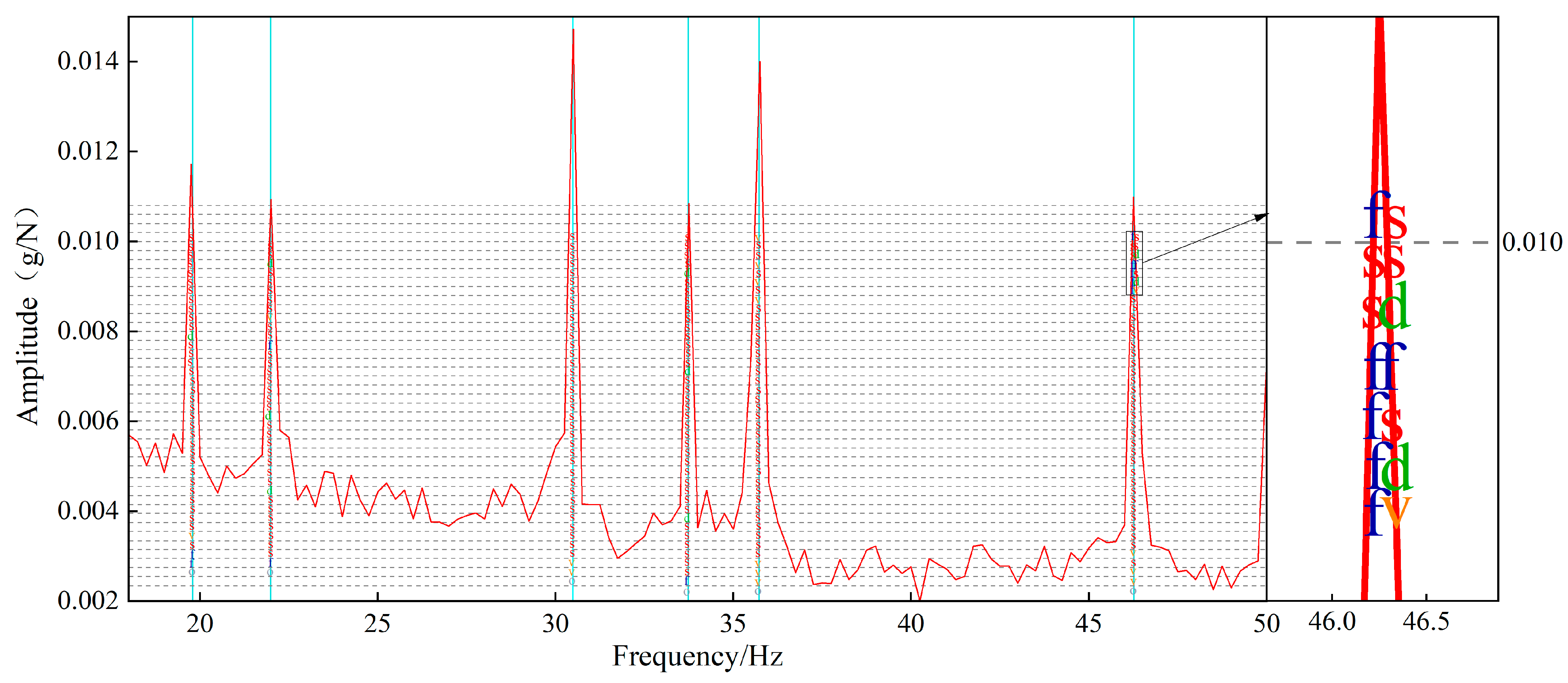

The PolyMax algorithm is used, and 0~200 Hz is selected as the analysis bandwidth to obtain the steady-state diagram (

Figure 10).

In the stabilization interface, the first six peaks are the objects (corresponding to the first six order test modes of the frame). The best pole is selected in the continuous s points near it (the meaning of the pole symbol is shown in

Table 3); the more continuous s points, the higher the degree of modal stability extracted near them, and the more realistic the modal parameters obtained. Finally, the first six order modal test parameters of the frame are obtained, as shown in

Table 4.

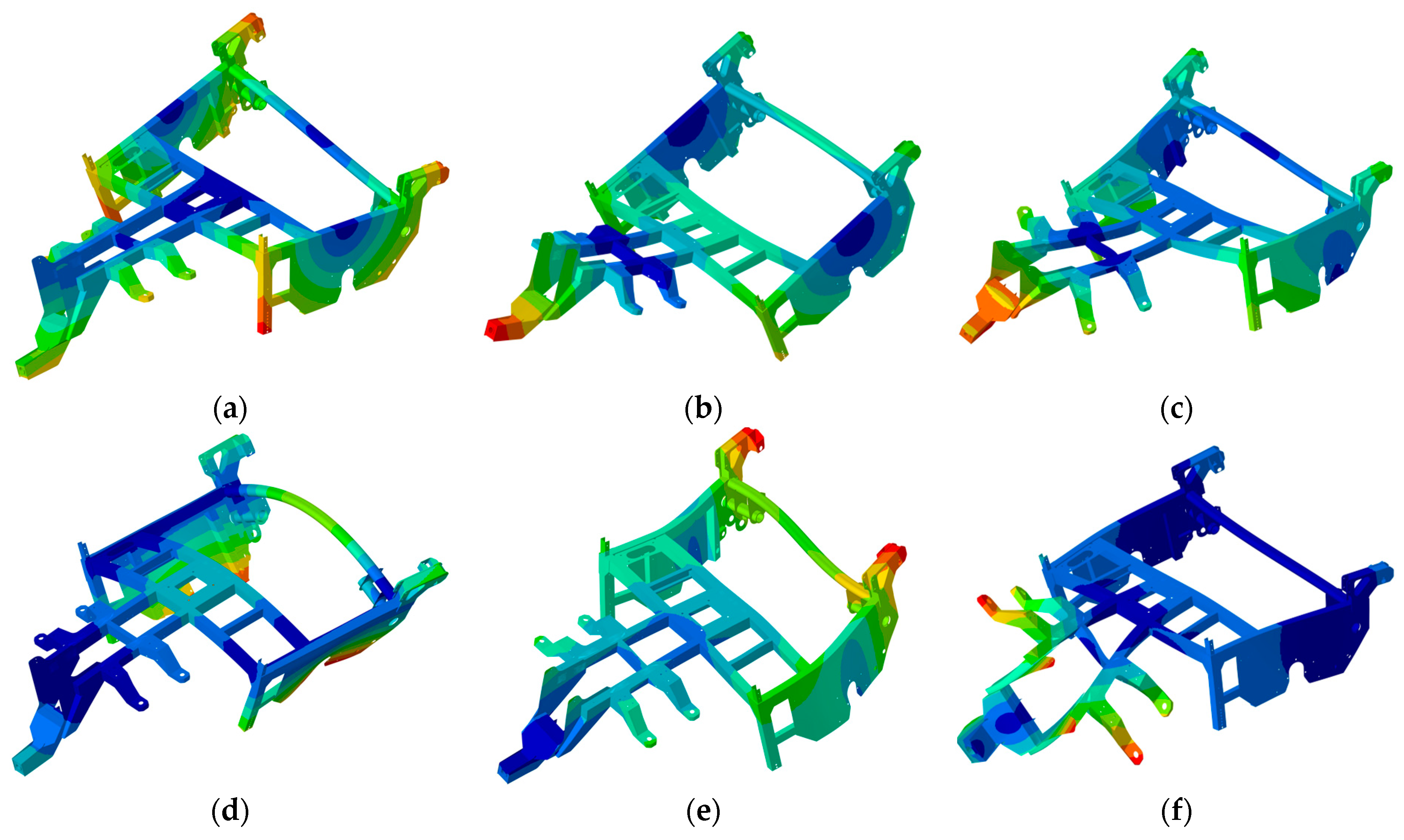

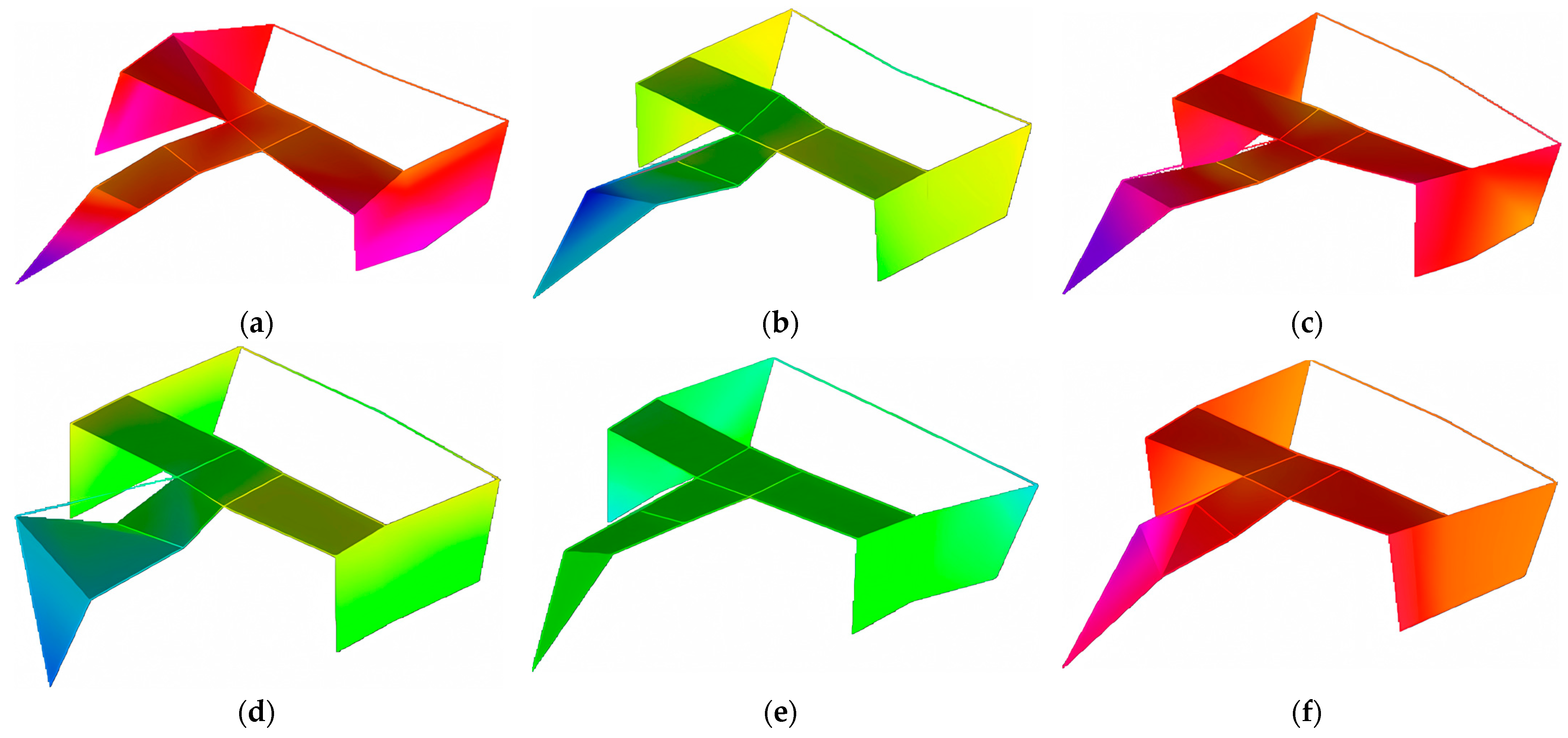

The table shows that the modal frequency of the frame is concentrated in the low-frequency band of 19.77–46.31 Hz, and the first six order modal shapes (as shown in

Figure 11) are consistent with the finite element modal analysis results.

Using modal confidence and frequency response confidence analysis, this paper verifies the rationality of modal tests to ensure that the results of modal test parameters are desirable.

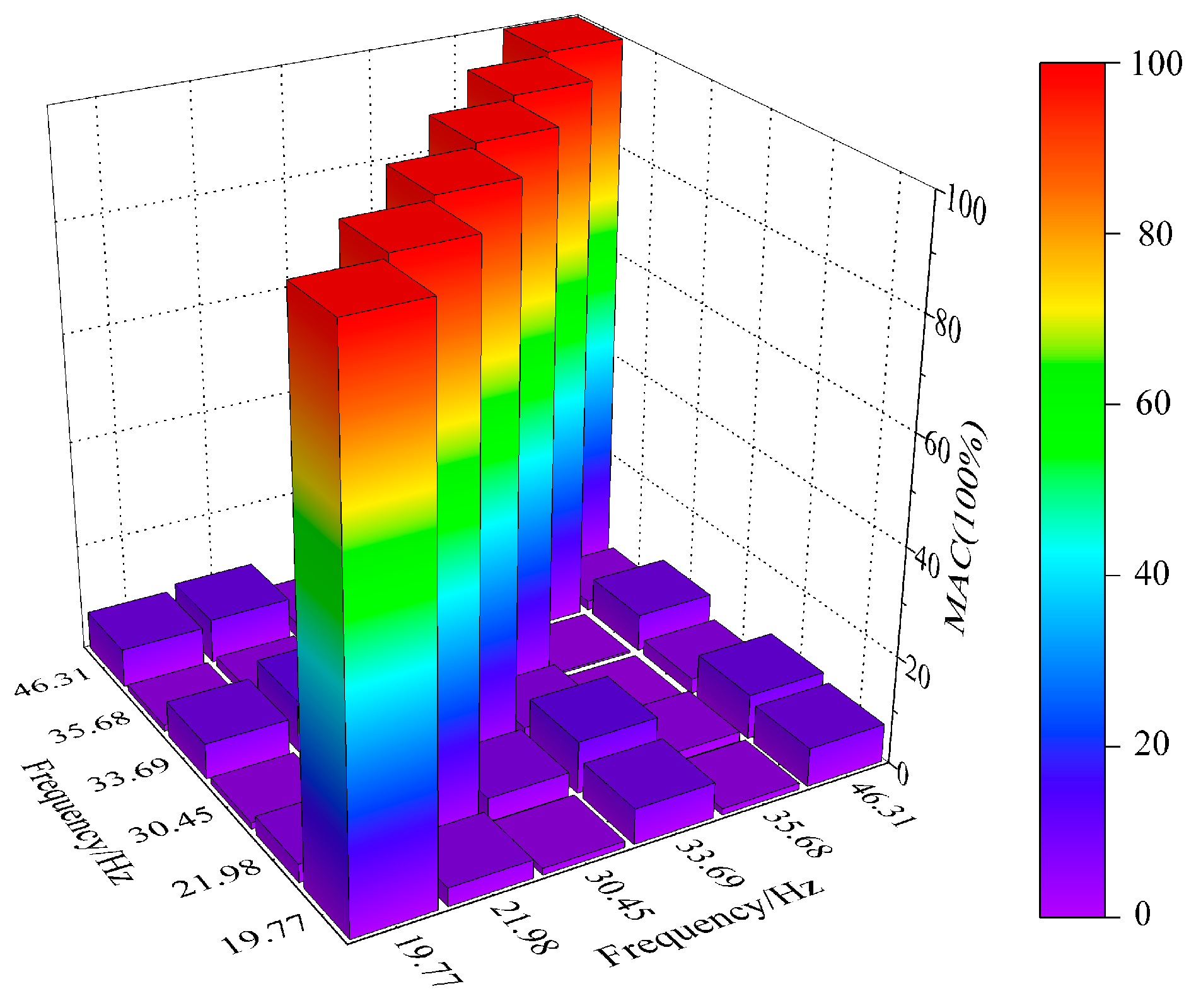

4.5. Modal Confidence Analysis

The MAC confidence criterion [

26] is used to verify the correlation of the modal results of each order, and the results are shown in

Figure 12. The MAC confidence criterion compares two modal shape vectors with any scale. The MAC value should be close to 100% under the same order mode, and the MAC value should be 0 under different order modes. The MAC confidence criterion matrix is expressed as follows:

In the formula, Φi and Φj are the ith row and jth column modal vectors in the MAC matrix, respectively. The elements in the MAC matrix reflect the dot product between the vectors of the current modal shape; that is, when the intersection angle of the modal shape vector is 90°, the corresponding MAC value is 0; that is, the correlation between the two is small. Meanwhile, when the modal shape vector intersection angle is 0°, the corresponding MAC value is 1; that is, the correlation between the two is large.

Figure 12 shows that the height of each element of the diagonal corresponds to the MAC value of the same order, which is 100%. The height of the other elements corresponds to the MAC values of different orders, which are close to 0, indicating the absence of a false mode, and the modal confidence is ideal.

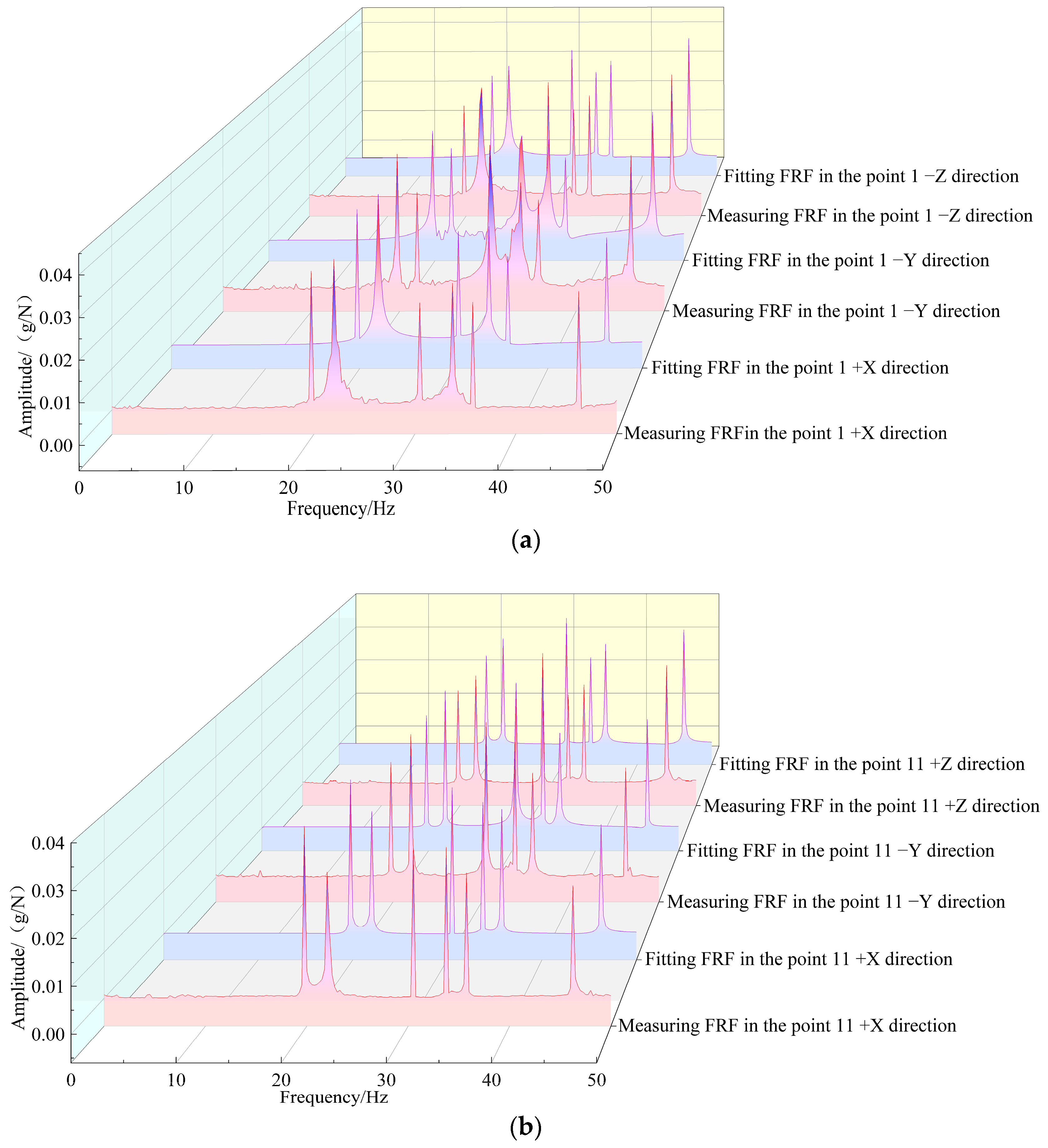

4.6. Confidence Analysis of Frequency Response

To further verify the rationality of the extracted modal test parameters, this paper evaluates the frequency response confidence by investigating the correlation and error between the measured FRF and the fitted FRF as a reference. Specifically, the FRF of the interaction between the input and the output measurement points is obtained by solving the Maxwell–Betti reciprocity theorem [

27] to ensure that the FRF fitted in multiple ways corresponds to at least one input degree of freedom with a scale modal shape (including modal shape coefficient).

Using the frequency response function fitting criterion:

In the formula, Hij is the frequency response function matrix of i rows and j columns; ψr is the rth mode shape; Lr is the modal vector; λr is the modal pole; and UR and LR are upper and lower residuals, respectively.

The complex conjugate product of measured FRF and fitted FRF is normalized:

In the formula, Si and Mi represent the complex values of the fitted FRF and the measured FRF at the spectral line i, respectively, and * represents the conjugate.

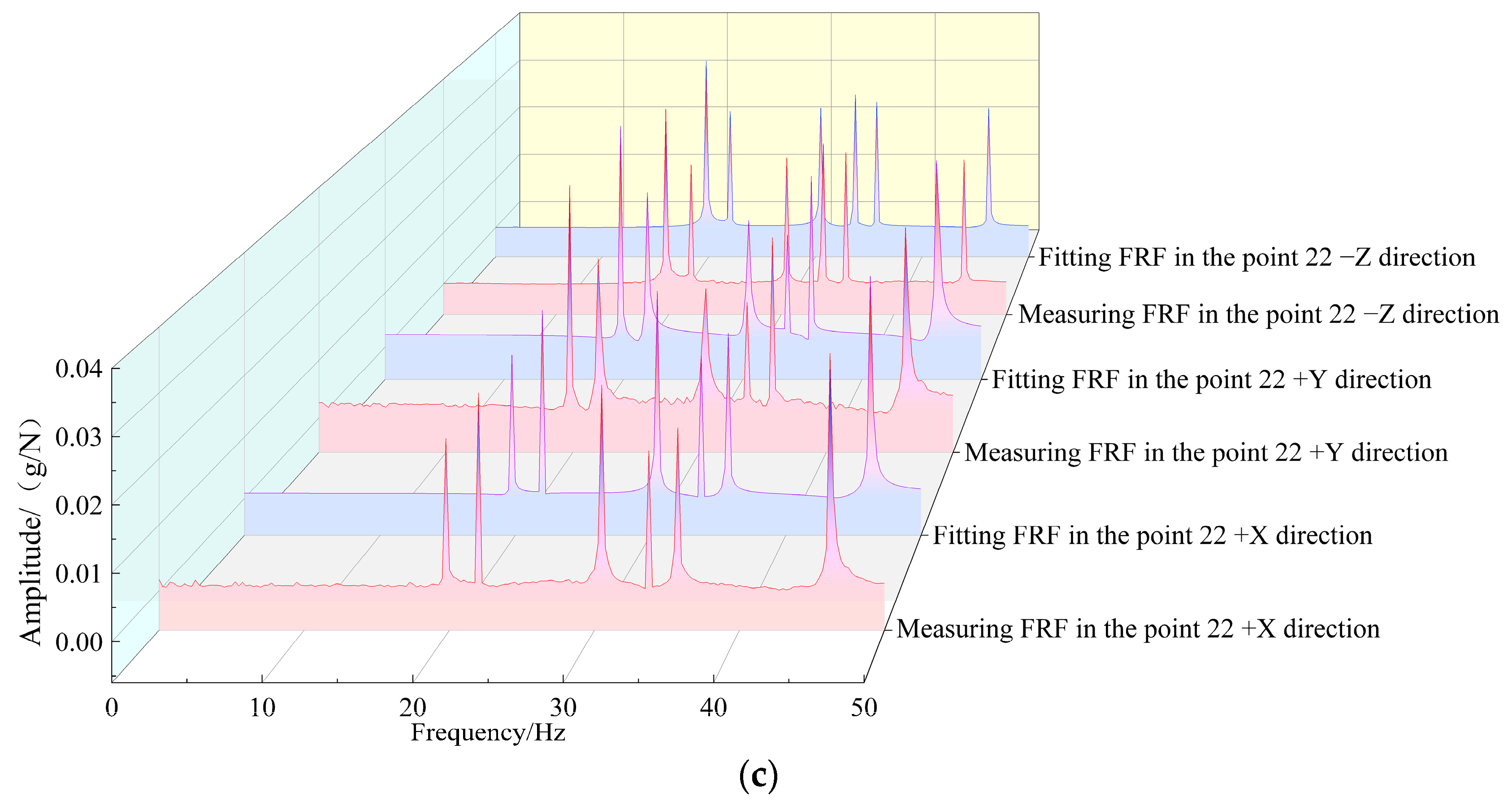

Due to the limited space, only the FRF curves of measuring point 2 (−X, −Y, and −Z directions) and the reference point (points 1, 11, and 22) are compared and verified. The comparison frequency band of the FRF curve is 0~60 Hz. The comparison results of the FRF curve are obtained in modal synthesis (

Figure 13).

Figure 13 shows that the trend between the three-way measurement FRF curve of the reference point (points 1, 11, and 22) and the fitted FRF curve is relatively close. The difference of the corresponding amplitude (g/N) at the same frequency (Hz) is small, reflecting that the FRF curve between the measuring point 2 and the reference point has a high correlation and a small error; that is, the frequency response confidence is high.

In summary, from the perspective of modal confidence and frequency response confidence results, the extraction of frame modal test parameters is proven to be effective, and the reliability of test results is high.

4.7. Results Comparison and External Incentive Analysis

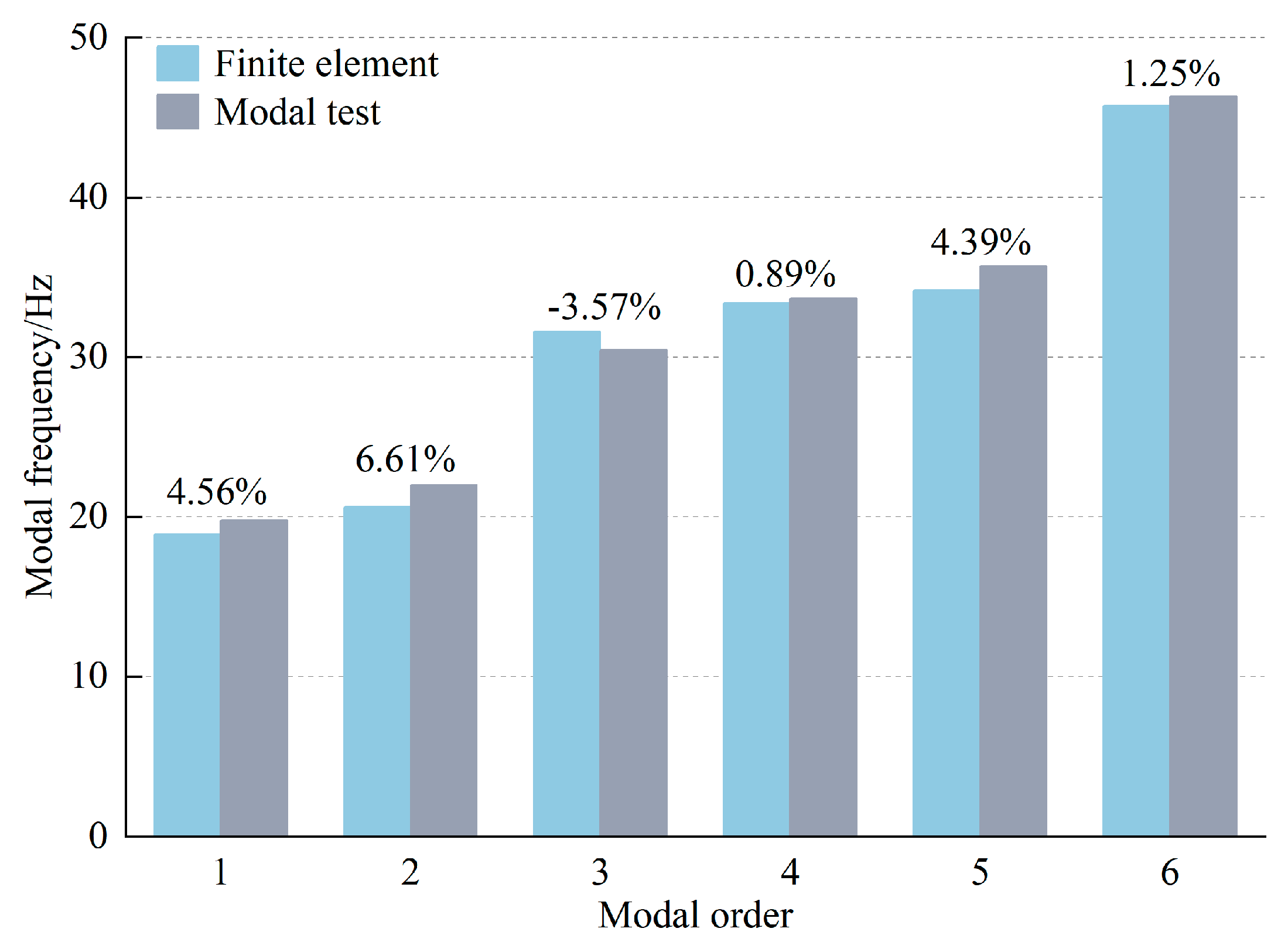

The results of the finite element analysis and modal test are compared and analyzed, and the results of the comparison are shown in

Figure 14. The figure shows that the frame’s finite element modal analysis results are in good agreement with the modal test results. The maximum relative error of each order’s natural frequency is 6.61%, and the reliability of the finite element modal analysis results is high.

The external excitation source (as shown in

Table 5) of the straw-crushing residual film recycling machine comes from the vibrations caused by the tractor traction, the work, and the undulation of the field terrain. The power input of the whole machine is provided by a John Deere 1404-A 6-cylinder 4-stroke tractor (rated power is 103 kW), and the external excitation provided by it is:

In the formula, fT is the engine frequency, Hz; nt is the working speed, r/min; z is the number of engine cylinders; and τ is the number of engine strokes.

The straw-crushing residual film recycling machine operates at a speed of 8~10 m/s in the field, and the external incentives it provides are:

In the formula, fr is the path spectrum frequency, Hz; v is the forward speed of the machine, m/s; and nr is the spatial frequency, Hz.

When the straw-crushing residual film recycling machine operates, the external excitation of the frame by each rotating part is:

In the formula, fw is the rotation frequency, Hz, and nw is the working rotation speed.

The modal analysis results show the excitation frequency generated by the stripping roller is close to the first-order natural frequency of the frame. The frame is optimized to avoid the resonance phenomenon of the machine during operation, shorten its service life, and ensure that it meets stiffness and strength requirements. Finally, the machine avoids the external excitation frequency and ensures that the volume of the frame is not too large. Considering that the relative installation positions of the working parts of the 1-MSD straw-crushing and residual film recycling machine have been determined, the cost of changing the overall structure of the frame is too large, and thus, the method of changing the thickness of each part of the frame is used to optimize.

5. Sensitivity and Grey Correlation Analysis

In this paper, the optimization results of the frame are obtained through a joint analysis of sensitivity and grey correlation degree. Specifically, the sensitivity analysis method is used to obtain the sensitivity of each frame component to the first-order natural frequency. At the same time, a multi-objective optimization mathematical model is established, and the Optistruct solver is used to solve it. Finally, a grey correlation evaluation table is constructed, and the optimal results are solved.

5.1. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis is used to explore the degree of influence of changes in structural parameters on mechanical properties [

28,

29]. In this paper, the sensitivity can be described as the change rate of the natural frequency of the frame caused by the different thicknesses of each part of the frame. The change rate is positive or negative, and the two are positively or negatively correlated. Because the frame is a steel structure, its structural damping is small. It is simplified to a non-damping multi-degree-of-freedom system [

30]. The specific dynamic equation is as follows:

where [

m] is the mass matrix of the n-order system; [

K] is the stiffness matrix of the n-order system; {

Ẍ} is an array, indicating acceleration; and {

X} is the array, which represents the displacement.

Its characteristic equation is:

where

ωi is the natural frequency of the system and {

Xi} is the modal shape vector.

The sensitivity of the natural frequency

ωi of the system to thickness

d is calculated by the direct derivative method; that is, the partial derivative of

d in the equation is obtained by multiplying {

Xi}

T on both sides of the equation.

In the formula, d is the thickness of the frame parts, mm.

Derivation of the formula, that is, the derivative sensitivity of the modal frequency, is the following:

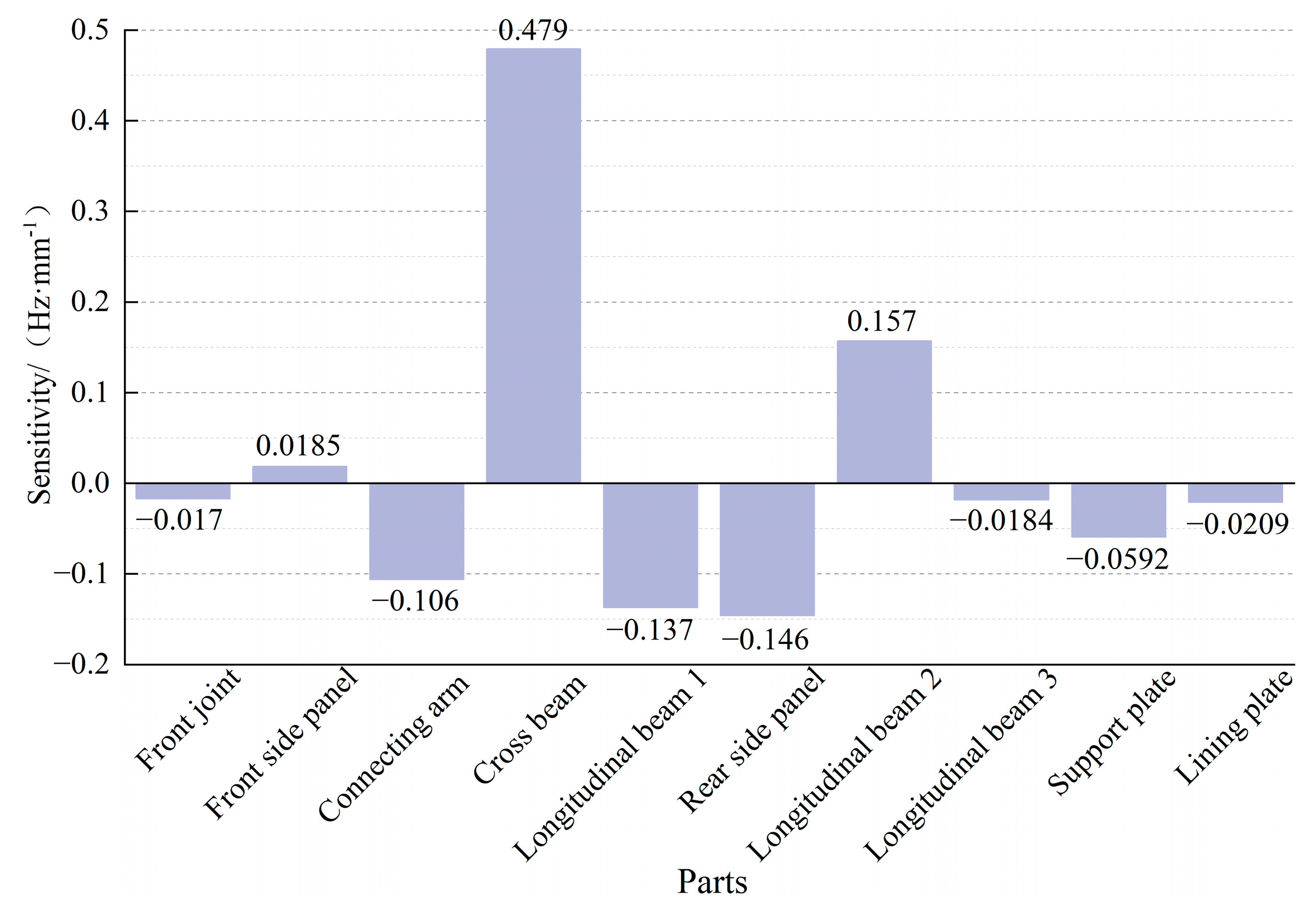

The sensitivity analysis of the 10 components of the frame is conducted according to the requirements of the operation stability of the straw-crushing residual film recycling machine and the results of the modal analysis. The thickness of the frame components is taken as the design variable, and the volume of the frame structure is taken as the optimization target. The lower limit of the first-order modal frequency optimization result is added to calculate the sensitivity of the first-order modal frequency of the frame relative to the thickness of each component. The results are shown in

Figure 15.

The sensitivity analysis result shows that the sensitivity of cross beam and longitudinal beam 2 to the first-order modal frequency of the frame is positive; that is, increasing the thickness of the component will increase the first-order modal frequency. The sensitivity of the remaining components to the first-order modal frequency of the frame is negative; that is, reducing the thickness of the component will increase the first-order modal frequency. The thicknesses of the higher-sensitivity parts of the frame are selected as the design variable; in this paper, the parts with the sensitivity result order of magnitude above × 10−2 are retained for exploration. Finally, the main optimization parts are the connecting arm, cross beam, longitudinal beam 1, rear side panel, and longitudinal beam 2.

5.2. Optimization Modeling and Solving

The first-order natural frequency of the hoist frame should also be as small as possible to meet the requirements of lightweight design of modern agricultural machinery [

31]. Therefore, the first-order natural frequency and volume of the frame are taken as the optimization objectives. According to the sensitivity analysis results, the thickness of each frame component is taken as the design variable, and the initial value and limit range of the thickness of each component and the first-order natural frequency are set in

Table 6.

Seven design variables are defined in

X = (

x1,

x2,

x3,

x4,

x5). The optimization objective function is the volume of the frame, and the optimization response is the first-order natural frequency of the frame. The mathematical model of the optimal design of the frame structure is obtained:

where

x1 is the connecting arm, mm;

x2 is the cross beam, mm;

x3 is the longitudinal beam 1, mm;

x4 is the back plate, mm;

x5 is the longitudinal beam 2, mm;

Fv(

X) is the function of the design variable to the volume of the frame; and

Ff(

X) is the function of design variables to the first-order natural frequency of the frame.

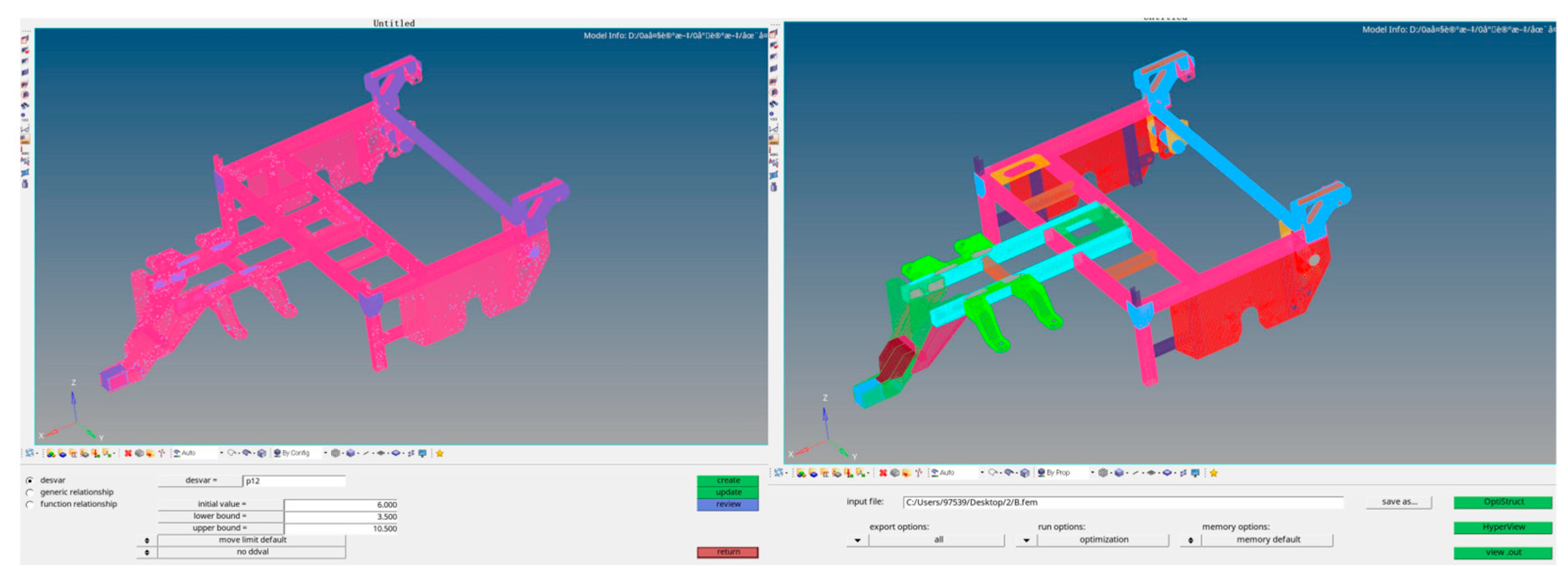

Six groups of non-inferior solutions in the range of (22 ± 0.2) Hz are obtained by iterative calculation using the Optistruct solver (the specific operation process is shown in

Figure 16), as shown in matrix R.

In the formula, K0 is the initial value column, and K1~K6 are six groups of non-inferior solutions.

5.3. Grey Correlation Analysis Method

For the modal evaluation of the frame, the evaluation method should be used to obtain the best design scheme. The purpose is to avoid the incompatibility of the single-index evaluation results in the multi-index decision-making process.

As an important part of grey system theory, grey relational analysis is a method to solve system problems based on fuzzy information [

32,

33,

34]. In this paper, by comparing the grey correlation degree of the optimized multi-group rack design scheme, the primary and secondary relationships between the optimization of the theoretical optimal schemes can be determined. Then, the optimal optimization scheme can be obtained. The steps of grey correlation analysis are as follows:

- (1)

Determine the design variables, reference sequence, and comparison sequence.

where

X0(

k) is the reference sequence;

Xi(

k) is the comparison sequence; and

p and

q represent the dimension of the sequence.

- (2)

Reduce the amount of steel treatment.

Because of the different dimensions of the thickness, frequency, and volume of the components in the system, to ensure the accuracy of the calculation results, the analysis data should be removed and tempered before the calculation. The standardization method is adopted in this paper.

In the formula, any data in each row are divided by the first data in the row.

- (3)

Calculate the grey correlation coefficient.

The normalized reference number {

X0(

t)} (where

t is time) and the comparison number {

Xi(

t)} are recorded. When

t =

k, the grey correlation coefficient

ξi(

k) of the system sequence is as follows:

In the formula, Δi is the absolute difference between the two series at k time; Δmin and Δmax are the minimum difference between the two stages and the maximum difference between the two stages, respectively; and ρ is the resolution coefficient, usually taken as 0.5.

- (4)

Calculate grey correlation degree.

In the formula, γi is the grey correlation degree between the evaluation object Xi(k) and X0(k).

5.4. Optimization Target Grey Correlation Analysis

The six sets of non-inferior solutions obtained by the Optistruct solver constitute

M1~

M6 (comparison sequence). This paper aims to improve the first-order modal frequency of the frame according to the sensitivity analysis results (

Figure 15). The minimum value of the connecting arm (

x1), the maximum value of the cross beam (

x2), the minimum value of the longitudinal beam 1 (

x3), the maximum value of the longitudinal beam 2 (

x4), and the minimum value of the rear side plate (

x5) corresponding to

M1~

M6 are selected as the design variables of the reference sequence (

M0). The optimal target frequency is set at 22 Hz, and the volume in the scheme

M4 is selected as the optimal target volume. The above data constitute the reference sequence

M0 and finally form the grey correlation analysis parameter evaluation table, as shown in

Table 7.

Through the analysis and processing of the table data through Formulas (6)~(8), the grey correlation degree between

M1~

M6 (comparison sequence), and reference sequence (

M0) is obtained, as shown in

Figure 17. The figure shows that the order of the optimal design schemes of the frame is

M4,

M3,

M2,

M5,

M1,

M6, and

M4 is the optimal design scheme.

The

M4 parameters of the scheme are taken as the optimization results, and the comparison of the frame parameters before and after optimization is shown in

Table 8. The table shows that under the condition of meeting the goal of improving the modal frequency of the frame and meeting the lightweight design of the frame, the thickness of the connecting arm (

x1) is 5.022 mm, the thickness of the cross beam (

x2) is 7.532 mm, the thickness of the longitudinal beam 1 (

x3) is 4.951 mm, and the thickness of the longitudinal beam 2 (

x4) is 10.750 mm. The thickness of the rear side plate (

x5) is 9.421 mm. The first-order modal frequency of the frame is increased by 15.88% to 21.89 Hz, which is much higher than the excitation frequency of 16.67 Hz, which can avoid resonance. The volume decreased by 3.46% to 9.743 × 10

7 mm

3.

According to the optimization results, the frame is remodeled, and the finite element modal analysis is carried out.

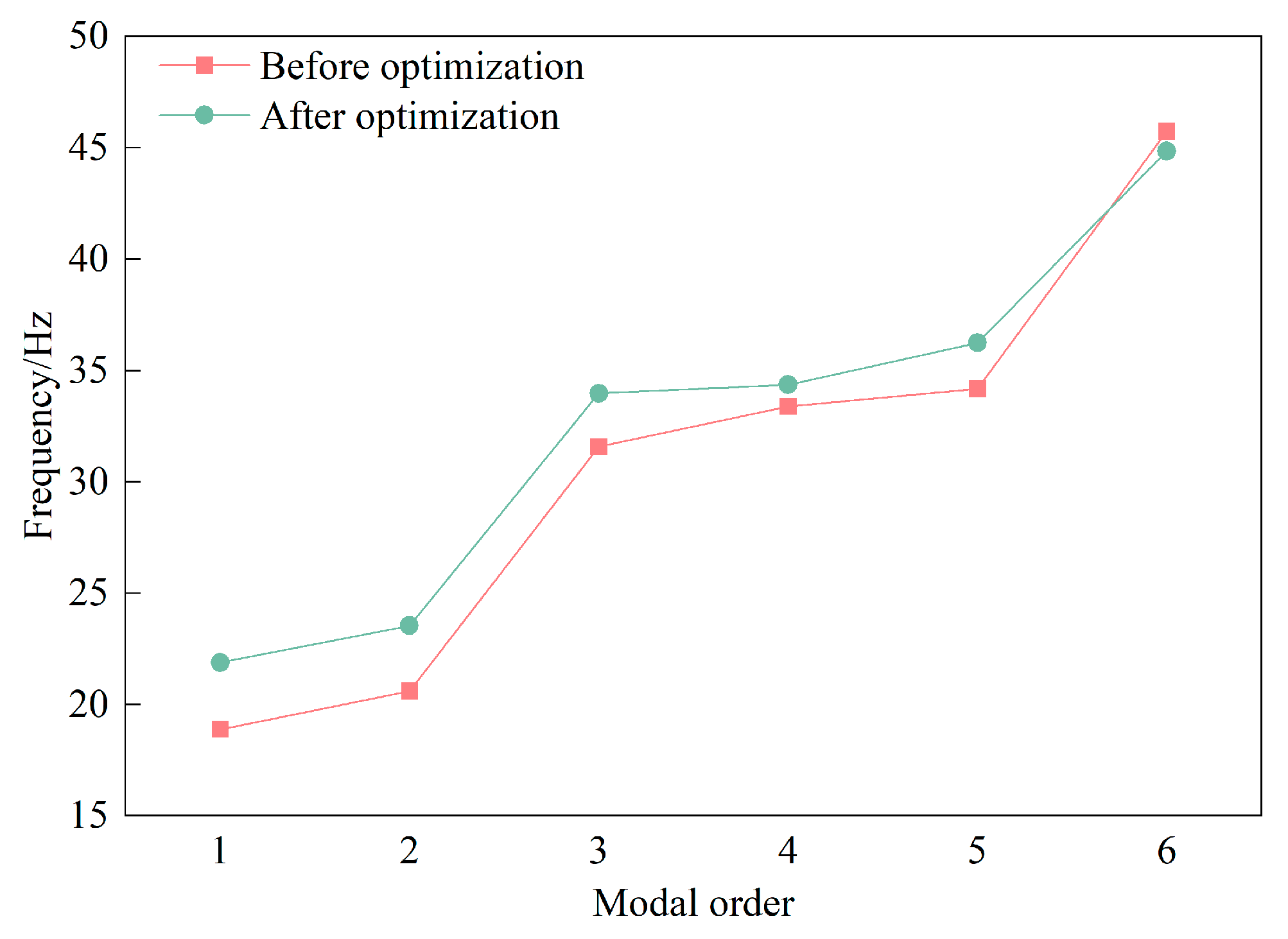

Figure 18 compares the first six order modal frequencies of the finite element before and after the frame optimization. The first six natural frequencies of the frame are adjusted to 21.89 Hz, 23.55 Hz, 33.98 Hz, 34.36 Hz, 36.24 Hz, and 44.85 Hz, respectively, all of which avoid the external excitation frequency.

Considering the process characteristics of the actual processing, according to the results of the optimized size data of the scheme

M4, the two digits after the decimal point (rounding method) are retained for the frame processing. The optimized frame has a good assembly effect on the 1-MSD straw-crushing residual film recycling machine and the field operation process is stable (as shown in

Figure 19).