How Can Digital Villages Improve Basic Public Services Delivery in Rural Areas? Evidence from 1840 Counties in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Development and Importance of Digital Villages

1.2. The Importance of Basic Public Services Delivery in Rural Areas

1.3. The Forward-Looking Role of Digital Villages in Basic Public Services Delivery

1.4. Limitations of Existing Studies and Issues Raised

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Concept of Digital Villages

2.2. The Concept of Basic Public Services

2.3. Digital Technology and Rural Sustainable Development

2.4. Digital Technology and Rural Public Services

2.5. Summary of Literature

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

3.1. Digital Villages Are Positively Associated with the Accessibility of Rural Basic Public Services

3.2. Digital Villages Are Positively Associated with the Equity of Rural Basic Public Services

3.3. Digital Villages Are Positively Associated with the Agility of Rural Basic Public Services

3.4. Digital Villages Are Positively Associated with the Holistic Nature of Rural Basic Public Services

3.5. Digital Villages Are Positively Associated with Participation in Rural Basic Public Services

3.6. The Regional Heterogeneity of the Relationship between Digital Villages and Rural Basic Public Services

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Sources and Sample Selection

4.2. Variables Measurement

4.3. Data Analysis Methods

5. Empirical Analysis and Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Entropy Method

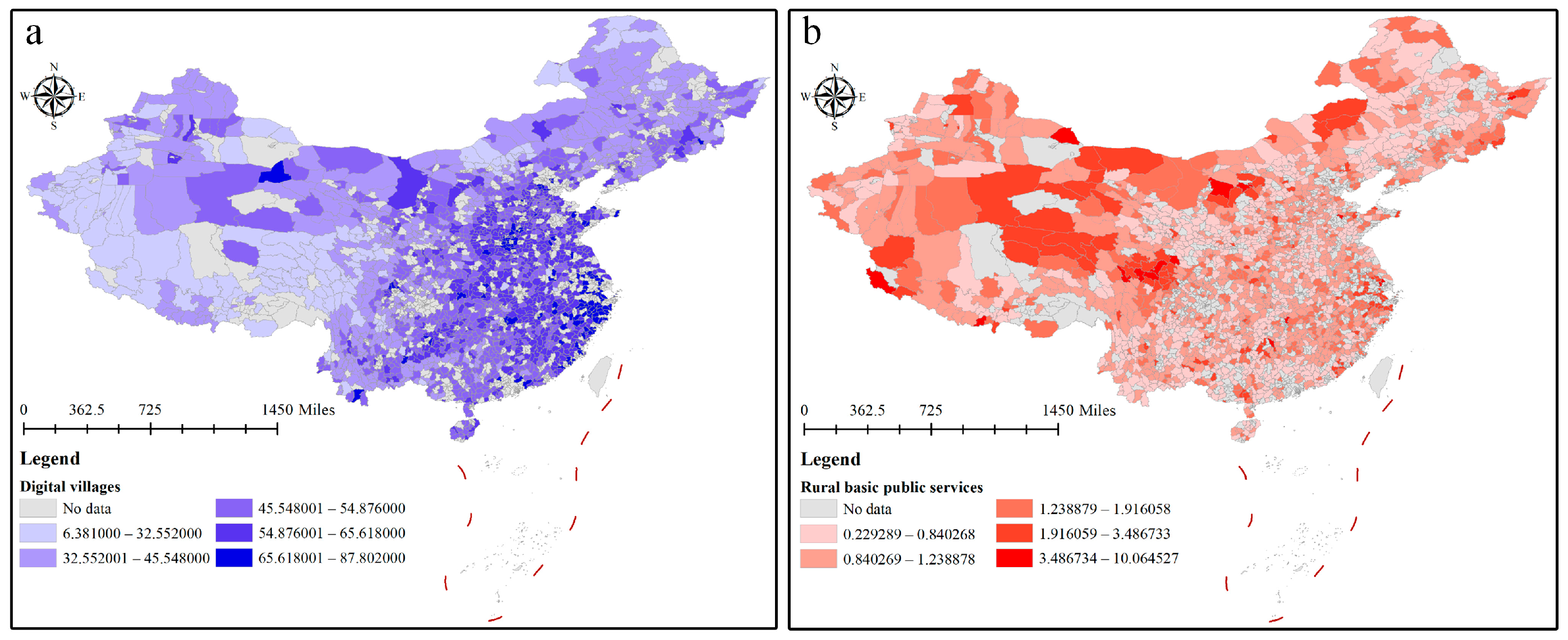

5.3. Spatial Distribution

5.4. Correlation Analysis

5.5. Regression Analysis

5.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Discussions

6.2. Conclusions

6.3. Practical Implications

- (1)

- Promote the construction of digital infrastructure in rural areas. Digital infrastructure is an important material basis for the digitisation of basic public services. On one hand, to raise the standard of rural communication services, network infrastructure construction—such as mobile Internet and broadband communication—should proceed more quickly. On the other hand, the new generation of information services infrastructure should be improved through applications, intelligent and convenient service terminals, and information service platforms to connect the ‘last kilometre’ of rural basic public services, thereby laying the foundation for enhancing the accessibility of basic public services.

- (2)

- Use data integration to promote the holistic delivery of rural basic public services. Digital villages should be used to promote the sharing and integration of basic public service data between regions and between urban and rural areas, thereby strengthening cross-level, cross-regional and cross-departmental cooperation, building an integrated basic public service digital platform to meet the diverse needs of rural residents, and realizing the holistic delivery of rural digital public services.

- (3)

- Utilize digital villages to establish a platform for collecting, expressing and feedback of basic public service needs, provide opportunities for the broad participation of rural residents, and enhance interaction between the government and rural residents. At the same time, conduct full-process supervision of the quality and quantity of rural basic public services delivery, promptly perceive and respond to the needs and demands of rural residents, especially vulnerable groups, provide more accurate personalized services, and promote accurate matching of supply and demand.

- (4)

- Narrow the gap in digital village construction and ensure a balanced rural digital public service delivery across regions. Establishing a nationwide unified policy, standard and investment and operational mechanism for the construction of digital villages at the institutional level enhances the scalability of the technology and functions of rural digital public services platforms. At the organisational level, establish a management mechanism that connects the central and local governments to ensure consistency in their digital villages planning. To guarantee resource security, the central government should increase its direct investment in the construction of digital villages in underdeveloped regions through transfer payments and special construction and guide developed regions in using their resource advantages to support their underdeveloped counterparts in constructing digital villages.

- (5)

- Accelerate the development of rural digital talent and the spread of digital application technologies. Through publicity, promotion, and digital skills training on digital basic public services, authorities can expose rural residents to the use of digital services, improve their digital literacy, encourage their digital services adoption, provide special venues, personnel and equipment for digitally disadvantaged groups and ensure that the majority of the rural residents have low-cost and convenient access to digital public services.

6.4. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UN | United Nations |

| ICT | Information Communication Technologies |

| EU | European Union |

| DVI | Digital Villages Index |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| RBPS | Rural Basic Public Services |

References

- Wang, Q.; Luo, S.; Zhang, J.; Furuya, K. Increased Attention to Smart Development in Rural Areas: A Scientometric Analysis of Smart Village Research. Land 2022, 11, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.K.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Kumar Das, P. Village 4.0: Digitalization of village with smart internet of things technologies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 165, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemink, K.; Strijker, D.; Bosworth, G. Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unesco. Realizing the Future We Want for All: Report to the Secretary-General; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.undp.org/publications/realizing-future-we-want-all (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- China Economic Net. Pingping Wang: The Total Population Has Declined Slightly, and the Level of Urbanization Has Continued to Increase. 2023. Available online: http://www.ce.cn/xwzx/gnsz/gdxw/202301/18/t20230118_38353400.shtml (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China; The State Council; Council. Strategic Plan for Rural Revitalization (2018–2022). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2018/content_5331958.htm (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Cambra Fierro, J.J.; Pérez, L. (Re)thinking smart in rural contexts: A multi-country study. Growth Chang. 2022, 53, 868–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, A.; Stanny, M. Smart Villages: Where Can They Happen? Land 2020, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Metri, B.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P. Challenges common service centers (CSCs) face in delivering e-government services in rural India. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Phang, C.W.; Wei, J. Using microblog to enhance public service climate in the rural areas. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liang, Z.; Li, B. Realizing a Rural Sustainable Development through a Digital Village Construction: Experiences from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, K.; Chen, H.; Zhao, S. The Evolution Model of and Factors Influencing Digital Villages: Evidence from Guangxi, China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China; The State Council; Council. Opinions on Implementing the Rural Vitalization Strategy. 2018. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2018/content_5266232.htm (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- The CPC Central Committee; The General Office of the State Council. Digital Village Development Strategy Outline. 2023. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-05/16/content_5392269.htm (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Cyberspace Administration of China. Action Plan for Digital Village Development (2022–2025). 2023. Available online: http://www.cac.gov.cn/2022-01/25/c_1644713315749608.htm (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- The European Commission. EU Action for Smart Villages. 2023. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/eu-action-smart-villages_en (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Holmes, J.; Jones, B.; Heap, B. Smart villages. Science 2015, 350, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maja, P.W.; Meyer, J.; von Solms, S. Smart Rural Village’s Healthcare and Energy Indicators—Twin Enablers to Smart Rural Life. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Alvite, A.; Fernandez-Crehuet, J.M. Smart Rural: Current status of the intelligent, technological, social and sustainable rural development in the European Union. Innovation 2021, 34, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council. The 14th Five-Year Plan for Public Services. 2023. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-01/10/content_5667482.htm (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Osborne, S.P.; Radnor, Z.; Nasi, G. A New Theory for Public Service Management? Toward a (Public) Service-Dominant Approach. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2013, 43, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; He, Q. The effect of basic public service on urban-rural income inequality: A sys-GMM approach. Ekon. Istraživanja 2019, 32, 3211–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Yu, X.; Wang, Y. The impact of basic public services on residents’ consumption in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, E.J. Digital development in rural areas: Potentials and pitfalls. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieger, J.E. The broadband digital divide and the economic benefits of mobile broadband for rural areas. Telecommun. Policy 2013, 37, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, G.; Mei, C.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L. Application of Digital Governance Technology under the Rural Revitalization Strategy. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 046010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benami, E.; Carter, M.R. Can digital technologies reshape rural microfinance? Implications for savings, credit, & insurance. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 1196–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Ma, F.; Deng, W.; Pi, Y. Digital inclusive finance and rural household subsistence consumption in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X. Digital revolution and rural family income: Evidence from China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 94, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, X. Analysis on the Path of Digital Villages Affecting Rural Residents’ Consumption Upgrade: Based on the Investigation and Research of 164 Administrative Villages in the Pilot Area of Digital Villages in Zhejiang Province. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 928030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adesipo, A.; Fadeyi, O.; Kuca, K.; Krejcar, O.; Maresova, P.; Selamat, A.; Adenola, M. Smart and Climate-Smart Agricultural Trends as Core Aspects of Smart Village Functions. Sensors 2020, 20, 5977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Li, Q.; Lan, J. The Mediating Role of Social Capital in Digital Information Technology Poverty Reduction an Empirical Study in Urban and Rural China. Land 2021, 10, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, Y.; Si, H. Digital Economy Development and the Urban–Rural Income Gap: Intensifying or Reducing. Land 2022, 11, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Li, W.; Teo, B.S.X.; Othman, J. Can China’s Digital Inclusive Finance Alleviate Rural Poverty? An Empirical Analysis from the Perspective of Regional Economic Development and an Income Gap. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Singh Chandel, R.B.; Xia, X. Analysis on Regional Differences and Spatial Convergence of Digital Village Development Level: Theory and Evidence from China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, H. Comprehensive evaluation of digital village development in the context of rural revitalization: A case study from Jiangxi Province of China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, W.; Wen, J.; He, J. Spatial-Temporal Variations and Driving Factors of the Coupling and Coordination Level of the Digital Economy and Sustainable Rural Development: A Case Study of China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wen, X. Regional unevenness in the construction of digital villages: A case study of China. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Miao, J.; Lu, Y. Digital Villages Construction Accelerates High-Quality Economic Development in Rural China through Promoting Digital Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Cheng, D. Has Digital Village Construction Improved Rural Family Resilience in China? Evidence Based on China Household Finance Survey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Li, M.; Cao, X. Empowering Rural Development: Evidence from China on the Impact of Digital Village Construction on Farmland Scale Operation. Land 2024, 13, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, C.; Huang, C. The Impact of Digital Village Construction on County-Level Economic Growth and Its Driving Mechanisms: Evidence from China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Chen, X.; Shi, L.; Liu, P.; Tan, Z. Digital Village Construction: A Multi-Level Governance Approach to Enhance Agroecological Efficiency. Agriculture 2024, 14, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, A.; Hou, Y.; Tan, J. How does digital village construction influences carbon emission? The case of China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertot, J.; Estevez, E.; Janowski, T. Universal and contextualized public services: Digital public service innovation framework. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Yu, J.X. Leading Digital Technologies for Coproduction: The Case of “VisitOnce” Administrative Service Reform in Zhejiang Province, China. J. Chin. Political Sci. 2019, 24, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, I.; Madsen, C.Ø.; Hofmann, S.; Melin, U. Close encounters of the digital kind: A research agenda for the digitalization of public services. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Cheng, Y.D.; Yu, J. From recovery resilience to transformative resilience: How digital platforms reshape public service provision during and post COVID-19. Public Manag. Rev. 2022, 25, 710–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy, P.; Margetts, H.; Bastow, S.; Tinkler, J. New Public Management Is Dead—Long Live Digital-Era Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2006, 16, 467–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Mao, Z.; Yan, R.; Liu, S.; Duan, Z. Vision and reality of e-government for governance improvement: Evidence from global cross-country panel data. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 194, 122667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; van der Voort, H. Agile and adaptive governance in crisis response: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunleavy, P.; Margetts, H. The second wave of digital era governance. In Proceeding of the 2010 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington, DC, USA, 2–5 September 2010; American Political Science Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. How Do Smart Villages Become a Way to Achieve Sustainable Development in Rural Areas? Smart Village Planning and Practices in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Liu, S. Does urbanization promote the urban-rural equalization of basic public services Evidence from prefectural cities in China. Appl. Econ. 2023, 6, 3445–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, Y.; Kong, X. Spatio-Temporal Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Basic Public Service Levels in the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Land 2022, 11, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Hou, Y.; Randall, M.T.; Skov-Petersen, H.; Li, X. The spatio-temporal trade-off between ecosystem and basic public services and the urbanization driving force in the rapidly urbanizing region. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 111, 105554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, N.; Shen, K.; Zheng, X.; Li, C.; Lin, X.; Pei, T.; Wu, D.; Meng, X. Spatial effects of township health centers’ health resource allocation efficiency in China. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1420867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, X.; Law, R.; Sun, S. Developing Sustainable Urbanization Index: Case of China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, K.; Wu, D. Challenges and Opportunities for Coping with the Smart Divide in Rural America. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2020, 110, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Yearbook of Health in the People’s Republic of China. 2022. Available online: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/mohwsbwstjxxzx/tjtjnj/202305/6ef68aac6bd14c1eb9375e01a0faa1fb.shtml (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Wang, Y.; Deng, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Yue, T.; Liu, G. Energy endowment, environmental regulation, and energy efficiency: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 177, 121528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Impact of financial development on innovation efficiency of high-tech industrial development zones in Chinese cities. Technol. Soc. 2024, 76, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Ma, R. Green technology innovations, urban innovation environment and CO2 emission reduction in China: Fresh evidence from a partially linear functional-coefficient panel model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 176, 121434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, S.; Kaur, P.; Jhunjhunwala, A.; Narayanan, D.; Loyola, C.; Bedi, J.; Singh, Y. Examining linkages between Smart Villages and Smart Cities: Learning from rural youth accessing the internet in India. Telecommun. Policy 2018, 42, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tigelaar, D.E.H.; Admiraal, W. Rural teachers’ sharing of digital educational resources: From motivation to behavior. Comput. Educ. 2021, 161, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Hoelzer, S.; Tang, W.; Liang, Y.; Du, Y.; Xue, H.; Zhou, Q.; Yip, W.; Ma, X.; et al. Evaluation of a village-based digital health kiosks program: A protocol for a cluster randomized clinical trial. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 2012836901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hua, Y.; Sun, H.L.; Chen, Y. Bridging the rural digital divide: Avoiding the user churn of rural public digital cultural services. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 75, 730–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Huang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, X.; Lang, W. Problems and Strategies of Allocating Public Service Resources in Rural Areas in the Context of County Urbanization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selected as a National Typical Case—Yanqing New Era of Civilization Practice “Order Dispatch Order” So That Public Services Into the Mountains, Into the Village, Door-to-Door. Beijing Daily, 12 January 2023. Available online: https://news.bjd.com.cn/2023/01/12/10299207.shtml (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Sharma, S.; Kar, A.K.; Gupta, M.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Janssen, M. Digital citizen empowerment: A systematic literature review of theories and development models. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2022, 28, 660–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jesus, F.; Oliveira, T.; Bacao, F. The Global Digital Divide: Evidence and Drivers. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2018, 26, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. Overcoming digital poverty traps in rural Asia. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2022, 27, 1403–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Li, C.; Löschel, A.; Managi, S.; Lundgren, T. Digital technology and energy sustainability: Recent advances, challenges, and opportunities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 190, 106803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Digital Economy Report 2024. 2024. Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/digital-economy-report-2024 (accessed on 14 September 2024).

| Level 1 Indicators | Level 2 Indicators | Specific Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Rural Digital Infrastructure Index (0.27) | Information infrastructure index (0.30) | Mobile device accesses per 10,000 people |

| Digital Financial Infrastructure Index (0.30) | Breadth of digital financial infrastructure coverage | |

| Depth of use of digital financial infrastructure | ||

| Digital Business Landmark Index (0.20) | Percentage of online self-registered commercial landmark POIs out of the total number of commercial landmark POIs crawled per unit area | |

| Basic data resource system index (0.20) | Dynamic Monitoring and Response System (DMRS) applications | |

| Rural Economy Digitization Index (0.40) | Digital production index (0.40) | Construction of the National Modern Agriculture Demonstration Project |

| National New Industrialization Demonstration Base Construction | ||

| Percentage of Taobao villages among all administrative villages | ||

| Digital Supply Chain Index (0.30) | Logistics network points per 10,000 people | |

| Logistics timeframe for receiving parcels | ||

| Digital Marketing Index (0.20) | E-commerce sales of agricultural products per CNY 100 million yuan of primary industry value added | |

| With or without live sales | ||

| Whether it is a comprehensive demonstration county of e-commerce in rural areas | ||

| Number of online businesses per 10,000 people | ||

| Digital Finance Index (0.10) | Digitalization of financial inclusion | |

| Rural Governance Digitalization Index (0.14) | Governance instruments index (1.00) | Number of government business use users per 10,000 Alipay real-name users |

| Percentage of townships with WeChat public service platforms among all townships | ||

| Rural Life Digitalization Index (0.19) | Digital Consumption Index (0.28) | Online consumption per CNY 100 million yuan of total retail sales of social consumer goods |

| E-commerce sales per CNY 100 million yuan of GDP | ||

| Digital Literacy, Tourism, Education and Health Index (0.52) | Per capita top 100 entertainment video app usage | |

| Top 100 entertainment video categories per installed APP device Average length of APP usage | ||

| Per capita top 100 education and training app usage | ||

| Top 100 education and training categories per installed APP device Average usage time of APP | ||

| Number of recorded attractions on online travel platforms per 10,000 people | ||

| Cumulative total number of reviews of recorded attractions on online travel platforms per 10,000 people | ||

| Number of physicians from the county enrolled in network health platforms per 10,000 people | ||

| Digital Life Services Index (0.20) | Number of Alipay users using online lifestyle services per 10,000 Alipay users | |

| Number of online consumer orders per capita | ||

| Per capita spending on online life |

| Level 1 Indicators | Level 2 Indicators | Specific Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Composite index of rural basic public services | public investment | general public budget revenue per 10,000 people |

| basic public education | the number of general secondary school students per 10,000 people | |

| the number of elementary school students per 10,000 people | ||

| basic medical and health care | the number of beds in healthcare facilities per 10,000 people | |

| basic social services | the number of various social welfare adoption units per 10,000 people | |

| the number of various social welfare adoption beds per 10,000 people |

| Variables | Number of Cases | Realm | Minimum Value | Maximum Values | Average Value | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVI | 1840 | 81.42 | 6.38 | 87.80 | 50.23 | 12.15 |

| General public budget revenue per 10,000 people (CNY 100 million yuan) | 1840 | 10.91 | 0.02 | 10.93 | 0.32 | 0.50 |

| Number of general secondary school students per 10,000 people (persons) | 1840 | 1761.25 | 65.57 | 1826.82 | 450.21 | 138.19 |

| Number of elementary school students per 10,000 people (persons) | 1840 | 1780.90 | 86.48 | 1867.38 | 690.27 | 238.52 |

| Number of beds in healthcare facilities per 10,000 people (beds) | 1840 | 236.82 | 10.57 | 247.39 | 44.69 | 17.97 |

| Number of various social welfare adoption units per 10,000 people (units) | 1840 | 4.86 | 0.01 | 4.86 | 0.39 | 0.45 |

| Number of various social welfare adoption beds per 10,000 people (beds) | 1840 | 231.02 | 0.28 | 231.30 | 33.34 | 25.08 |

| Number of registered population (10,000 people) | 1840 | 246.66 | 0.78 | 247.44 | 48.68 | 37.12 |

| GDP per capita (CNY 100 million yuan) | 1840 | 45.65 | 0.54 | 46.19 | 4.19 | 3.74 |

| Value added of the secondary industry as a proportion of GDP | 1840 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.85 | 0.39 | 0.14 |

| Program | The Information Entropy Value (e) | Information Utility Value (d) | Weighting Factor (w) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBPS | General public budget revenue per 10,000 people (CNY 100 million yuan) | 0.9194 | 0.0806 | 40.01% |

| Number of general secondary school students per 10,000 people (persons) | 0.9916 | 0.0084 | 4.17% | |

| Number of elementary school students per 10,000 people (persons) | 0.9897 | 0.0103 | 5.13% | |

| Number of beds in healthcare facilities per 10,000 people (beds) | 0.9846 | 0.0154 | 7.63% | |

| Number of various social welfare adoption units per 10,000 people (units) | 0.9474 | 0.0526 | 26.09% | |

| Number of various social welfare adoption beds per 10,000 people (beds) | 0.9658 | 0.0342 | 16.96% |

| DVI | RBPS | The Number of Registered Population | GDP per Capita | Value Added of the Secondary Industry as a Proportion of GDP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVI | 1 | ||||

| the composite index rural basic public services | 0.105 *** | 1 | |||

| the number of registered population | 0.376 *** | −0.150 *** | 1 | ||

| GDP per capita | 0.325 *** | 0.496 *** | −0.043 | 1 | |

| Value added of the secondary industry as a proportion of GDP | 0.306 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.115 ** | 0.434 *** | 1 |

| β | Standardized Inaccuracies | t | p | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVI | 0.095 | 0.001 | 3.531 | <0.001 | 1.736 |

| Ln Number of the registered population | −0.285 | 0.016 | −11.389 | <0.001 | 1.512 |

| Ln GDP per capita | 0.363 | 0.025 | 13.917 | <0.001 | 1.642 |

| Ln Value added of the secondary industry as a proportion of GDP | 0.015 | 0.032 | 0.619 | 0.536 | 1.375 |

| East (1) | Central (2) | West (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DVI | 0.199 ** (4.687) | 0.068 (1.546) | 0.043 (1.106) |

| Ln Number of the registered population | −0.146 ** (−4.128) | −0.25 ** (−6.011) | −0.311 ** (−7.835) |

| Ln GDP per capita | 0.581 ** (13.358) | 0.28 ** (6.316) | 0.247 ** (5.744) |

| Ln Value added of the secondary industry as a proportion of GDP | −0.054 (−1.349) | 0.059 (1.273) | 0.034 (0.896) |

| sample size | 461 | 583 | 796 |

| R2 | 0.478 | 0.181 | 0.202 |

| Adjustment of R2 | 0.473 | 0.176 | 0.198 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mao, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zou, Q.; Jin, W. How Can Digital Villages Improve Basic Public Services Delivery in Rural Areas? Evidence from 1840 Counties in China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14101802

Mao Z, Zhu X, Zou Q, Jin W. How Can Digital Villages Improve Basic Public Services Delivery in Rural Areas? Evidence from 1840 Counties in China. Agriculture. 2024; 14(10):1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14101802

Chicago/Turabian StyleMao, Zijun, Xiyue Zhu, Qi Zou, and Wen Jin. 2024. "How Can Digital Villages Improve Basic Public Services Delivery in Rural Areas? Evidence from 1840 Counties in China" Agriculture 14, no. 10: 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14101802

APA StyleMao, Z., Zhu, X., Zou, Q., & Jin, W. (2024). How Can Digital Villages Improve Basic Public Services Delivery in Rural Areas? Evidence from 1840 Counties in China. Agriculture, 14(10), 1802. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14101802