How Do Support Pressure and Urban Housing Purchase Affect the Homecoming Decisions of Rural Migrant Workers? Evidence from Rural China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Literature Review

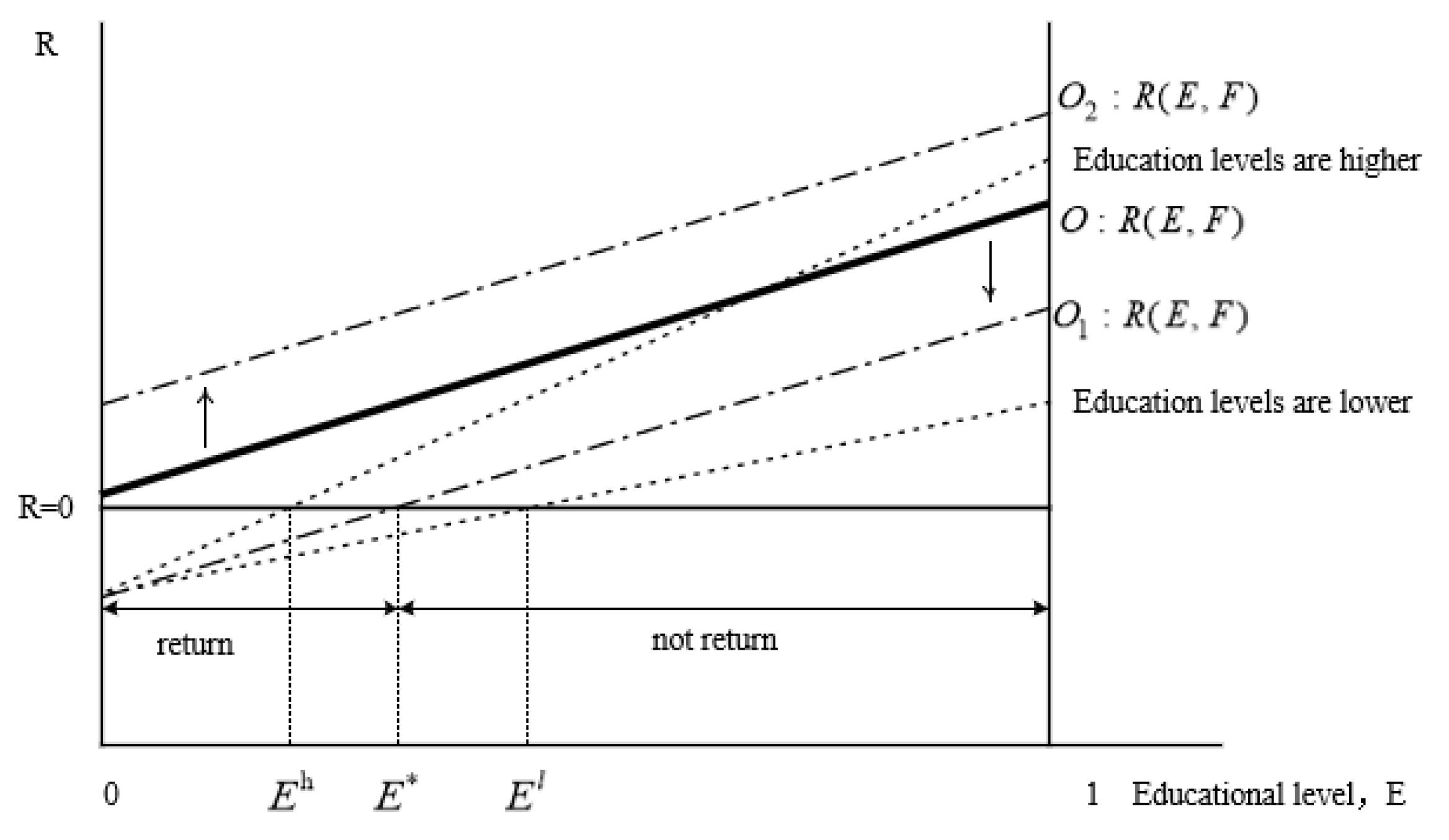

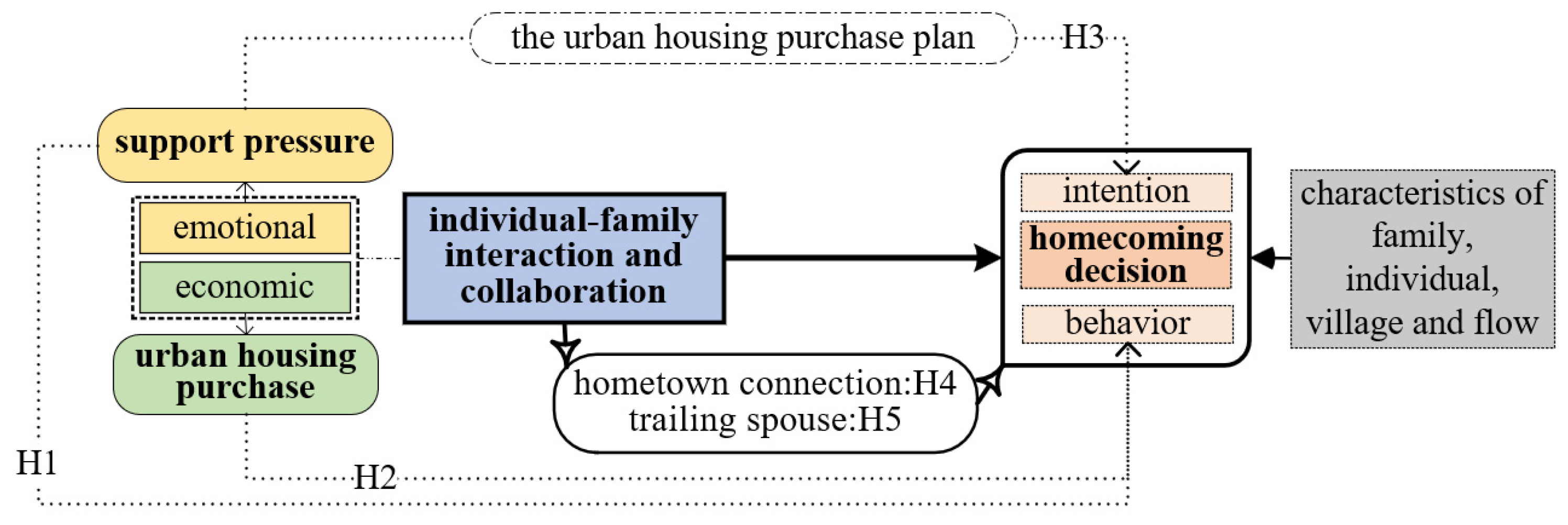

2.2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Variables and Descriptive Statistics

3.3. Methods

3.3.1. Baseline Model

3.3.2. Mediating Model

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression Results

4.2. Mediating Effect Analysis

4.3. Moderating Effect Analysis

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5. Robustness Test

5. Discussion

- (1)

- Labor migration is affected by many factors, and it is difficult to capture them all. This study only analyzes the impact of two major events in an individual’s life course, supporting the elderly and buying a house in a city, on their decision to return to their hometown. However, due to the design of the questionnaire, the number and specific situation of school-age children in peasant families have not been obtained. Therefore, the influence of this variable has not been verified at the family level, and supplementary research will be considered in the future.

- (2)

- Our study examined the influencing factors at the individual and household levels, but the factors at the village level were less selected. In particular, it ignores the role of ecological and cultural values of villages in attracting migrant workers back to their hometowns.

- (3)

- Housing price is an important factor affecting migrant migration. We conduct an analysis of the effects of housing prices based on the literature. Since the area we investigate is rural and the housing price changes, the existing research only asks farmers whether they buy houses in cities, and does not pay attention to the details such as the specific time when they buy houses in cities and the source of funds for the purchase. In the future, we hope to further refine the questionnaire design to enrich the research in this field.

- (4)

- We consider the promotion effect of urban public service variables on migrant workers’ entering the city in the decision-making equation, but limited by the availability of data in the empirical part, we do not test the impact of relevant variables on migrant workers’ migration.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Bureau of Statistics. Bulletin of the Seventh National Census (No. 7): Urban and Rural Population and Floating Population. 2021. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901087.html (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Knight, J.; Deng, Q.H.; Li, S. The puzzle of migrant labour shortage and rural labour surplus in China. China Econ. Rev. 2011, 22, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, A.; Pang, G.; Zeng, G. Entrepreneurial effect of rural return migrants: Evidence from China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1078199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, H. Migration, return, and development: An institutional perspective. Int. Migr. 2002, 40, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Huang, M.J.; Cai, X.M.; Yuan, Z.J.; Zhang, G.P. The gaps between policy design and peasant migrants’ intention of citizenization: The study of China’s Guangdong Province. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 100, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michele, B.; Luisa, C.M.; Martina, L.; Simone, B. Migrants in the economy of european rural and mountain areas. A cross-national investigation of their economic integration. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 99, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Cheng, X. Environmental regulation and rural migrant workers’ job quality: Evidence from China migrants dynamic surveys. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 78, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Tang, S. Floating or settling down: The effect of rural landholdings on the settlement intention of rural migrants in urban China. Environ. Plan. A 2015, 47, 1979–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Lin, Y.; Shen, T. Do you feel accepted? Perceived acceptance and its spatially varying determinants of migrant workers among Chinese cities. Cities 2022, 125, 103626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreger, C.; Wang, T.S.; Zhang, Y.Q. Understanding Chinese Consumption: The Impact of Hukou. Dev. Chang. 2015, 46, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, C.H. Putting family centre stage: Ties to nonresident family, internal migration, and immobility. Demogr. Res. 2018, 39, 1151–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. Labor Market Outcomes and Reforms in China. J. Econ. Perspect. 2012, 26, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.W.; Ye, W.X.; Wang, C.; Huang, X.H. Effects of Organizational Factors on Identification of Young Returnees from Urban Areas with Rural Societies—A Perspective of Adaptability. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 167, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.C. Settlement Intention and Split Households: Findings from a Survey of Migrants in Beijing’s Urban Villages. China Rev. 2011, 11, 11–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Li, Z.; Ma, Z. Changing Patterns of the Floating Population in China during 2000–2010. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2014, 40, 695–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.H. Causes and consequences of return migration: Recent evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2002, 30, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M.P. A Model for Labor Migration and Urban Unemployment in Less Developed Countries. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Dustmann, C.; Fadlon, I.; Weiss, Y. Return migration, human capital accumulation and the brain drain. J. Dev. Econ. 2011, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, A.; Massey, D.S. Return migration by German guestworkers: Neoclassical versus new economic theories. Int. Migr. 2002, 40, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb. Int. Rev. Econ. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. New Polit. Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, J. Mobilizing innovation for sustainability transitions: A comment on transformative innovation policy. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1568–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; Jayne, M. The creative countryside: Policy and practice in the UK rural cultural economy. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. Creative cities and economic development. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoey, B.A. From Pi to pie: Moral narratives of noneconomic migration and starting over in the postindustrial midwest. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2005, 34, 586–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floysand, A.; Jakobsen, S.E. Commodification of rural places: A narrative of social fields, rural development, and football. J. Rural. Stud. 2007, 23, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, H.T. Peasant Life in China: A Field Study of Country Life in the Yangtze Valley; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. The “half working and half farming” structure of rural China. Agric. Econ. Probl. 2015, 36, 19–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Li, Y.F.; Yue, Z.S. Parental migration, children and family reunification in China. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medaric, Z.; Gornik, B.; Sedmak, M. What about the family? The role and meaning of family in the integration of migrant children: Evidence from Slovenian schools. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 1003759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papero, D.V. Family Systems Theory and Therapy. In Handbook of Family and Marital Therapy; Wolman, B.B., Stricker, G., Framo, J., Newirth, J.W., Rosenbaum, M., Young, H.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, K.F.; Chiu, S.W.K. Leaving the parental home: Chinese culture in an urban context. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, J.; Mu, R. Elderly parent health and the migration decisions of adult children: Evidence from rural China. Demography 2007, 44, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okah, P.S.; Okwor, R.O.; Aghedo, G.U.; Iyiani, C.C.; Onalu, C.E.; Abonyi, S.E.; Chukwu, N.E. Perceived Factors Influencing Younger Adults’ Rural-Urban Migration and its Implications on Left Behind Older Parents in Nsukka LGA: Practice Considerations for Gerontological Social Workers. J. Popul. Ageing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustmann, C. Children and return migration. J. Popul. Econ. 2003, 16, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caarls, K.; de Valk, H.A.G. Relationship Trajectories, Living Arrangements, and International Migration Among Ghanaians. Popul. Space Place 2017, 23, e2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kley, S. Explaining the Stages of Migration within a Life-course Framework. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 27, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, A.; Mulder, C.H.; Bailey, A. ’For the sake of the family and future’: The linked lives of highly skilled Indian migrants. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2017, 43, 2788–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Council. Constitution of the People’s Republic of China; The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Housing cost burden, homeownership, and self-rated health among migrant workers in Chinese cities: The confounding effect of residence duration. Cities 2023, 133, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Bell, M.; Zhu, Y. Migration in China: A cohort approach to understanding past and future trends. Popul. Space Place 2019, 25, e2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, H. Migration and Development: A Theoretical Perspective. Int. Migr. Rev. 2010, 44, 227–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Nazroo, J.; Zhang, N. Do migration outcomes relate to gender? Lessons from a study of internal migration, marriage and later-life health in China. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.S.; Ma, L.B.; Wang, L.C.; Chen, X.F.; Shi, Z.H. Differences of Social Space of Rural Migrant Labor Force: The Influence of Local Quality. Land 2023, 12, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Z. Birds of passage: Return migration, self-selection and immigration quotas. Explor. Econ. Hist. 2017, 64, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, G.; Morten, M. The Aggregate Productivity Effects of Internal Migration: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Polit. Econ. 2019, 127, 2229–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, K.; Rosenzweig, M. Networks and Misallocation: Insurance, Migration, and the Rural-Urban Wage Gap. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 46–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, T.J. Gender role beliefs and family migration. Popul. Space Place 2008, 14, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.E. The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. Int. Migr. 1999, 37, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, T.J. Migration in a family way. Popul. Space Place 2008, 14, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, O.; Bloom, D.E. The new economics of labor migration. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.S. Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Popul. Index. 1990, 56, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhou, J.; Druta, O.; Li, X. Settlement in Nanjing among Chinese rural migrant families: The role of changing and persistent family norms. Urban. Stud. 2022, 60, 1083–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Wu, J. Return of migrant workers, educational investment in children and intergenerational mobility in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 997–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Demurger, S.; Xu, H. Left-behind children and return migration in China. IZA J. Migr. 2015, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heering, L.; van der Erf, R.; van Wissen, L. The role of family networks and migration culture in the continuation of Moroccan emigration: A gender perspective. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2004, 30, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.J.; Mulder, C.H.; Cooke, T.J. Linked lives and constrained spatial mobility: The case of moves related to separation among families with children. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2017, 42, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofman, E. Family-related migration: A critial review of European studies. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2004, 30, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtson, V.L. Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. J. Marriage Fam. 2001, 63, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, M. A Life-Course Analysis of Geographical Distance to Siblings, Parents, and Grandparents in Sweden. Popul. Space Place 2017, 23, e2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulibaleka, P.O.; Katunze, M. Rural-Urban Youth Migration: The Role of Social Networks and Social Media in Youth Migrants’ Transition into Urban Areas as Self-employed Workers in Uganda. In Urban Forum; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.W.; Fan, C.C. Success or Failure: Selectivity and Reasons of Return Migration in Sichuan and Anhui, China. Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 939–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, J.L. Factory Girls After the Factory: Female Return Migrations in Rural China. Gend. Soc. 2016, 30, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillemer, K.; Suitor, J.J. Making choices: A within-family study of caregiver selection. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.F. Changing Patterns and Determinants of Interprovincial Migration in China 1985–2000. Popul Space Place 2012, 18, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.; Pedersen, P.J. To stay or not to stay? Out-migration of immigrants from Denmark. Int. Migr. 2007, 45, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Ling, Y.; Shen, T. Return or not return: Examining the determinants of return intentions among migrant workers in Chinese cities. Asian Popul. Stud. 2020, 17, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiebout, C.M. A pure theory of local expenditures. J. Polit. Econ. 1956, 64, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, W.E. The Effects of Property Taxes and Local Public Spending on Property Values: An Empirical Study of Tax Capitalization and the Tiebout Hypothesis. J. Polit. Econ. 1969, 77, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasington, D.M.; Hite, D. Demand for environmental quality: A spatial hedonic analysis. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2005, 35, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, F.; Langset, B.; Rattso, J.; Stambol, L. Using survey data to study capitalization of local public services. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2009, 39, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, M.; Eklof, M.; Fredriksson, P.; Jofre-Monseny, J. Estimating Preferences for Local Public Services Using Migration Data. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Lu, M. The “Three migrations of Mencius and Mother” between cities: An empirical study on the impact of public services on labor flow. J. Manag. World 2015, 10, 78–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedomysl, T. Residential preferences for interregional migration in Sweden: Demographic, socioeconomic, and geographical determinants. Environ. Plan. A 2008, 40, 1109–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.P.; Rerat, P.; Sage, J. Youth migration and spaces of education. Child. Geogr. 2014, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.J.; Hu, J. Overeducation and Social Integration Among Highly Educated Migrant Workers in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branden, M. Couples’ Education and Regional Mobility—The Importance of Occupation, Income and Gender. Popul. Space Place 2013, 19, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas, G.J. The labor demand curve is downward sloping: Reexamining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Q. J. Econ. 2003, 118, 1335–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boski, P. A Psychology of Economic Migration. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2013, 44, 1067–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Chen, Y.F.; He, H.R.; Gao, G.L. Hukou identity and fairness in the ultimatum game. Theor. Decis. 2019, 87, 389–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, C.H.; Malmberg, G. Local ties and family migration. Environ. Plann A 2014, 46, 2195–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, P.; Cooke, T.J.; Halfacree, K.; Smith, D. A cross-national comparison of the impact of family migration on women’s employment status. Demography 2001, 38, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnish, T. Spousal Mobility and Earnings. Demography 2008, 45, 829–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.R.; Xue, P.; Zhang, N.N. Impact of Grain Subsidy Reform on the Land Use of Smallholder Farms: Evidence from Huang-Huai-Hai Plain in China. Land 2021, 10, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Han, X.R.; Wang, Y.C.; Wang, X.D. Can Agricultural Machinery Harvesting Services Reduce Cropland Abandonment? Evidence from Rural China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zou, J.; Ren, Q. The Retrospect and Prospect of Domestic Research on the Influencing Factors of Rural Migrant Workers Returning Home to Start Business. J. Beijing Union Univ. 2018, 16, 86–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Feng, H.; Ai, X.Q. The Research on Endowment of Land Resources and the Willingness of Migrant Workers to Return Home under the Background of Rural Revitalization. Popul. Econ. 2020, 6, 35–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lundholm, E. Are movers still the same? Characteristics of interregional migrants in Sweden 1970–2001. Tijdschr Econ Soc Ge 2007, 98, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Wiel, R.; Gillespie, B.J.; Tolboll, L. Migration for co-residence among long-distance couples: The role of local family ties and gender. Popul. Space Place 2023, 29, e2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Tesfazion, P.; Zhao, Z. Where are the migrants from? Inter- vs. intra-provincial rural-urban migration in China. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 47, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanner, P. Can Migrants’ Emigration Intentions Predict Their Actual Behaviors? Evidence from a Swiss Survey. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2021, 22, 1151–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Tan, H.; Li, L. Does Migration Experience Promote Entrepreneurship in Rural China? China Econ. Q. 2017, 16, 793–814. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Su, R. Endowment and Integration: A Study of the Factors Influencing the Settlement Intention of the Floating Population. South China Popul. 2020, 35, 41–56+67. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, W.Z. The Settlement Intention of China’s Floating Population in the Cities: Recent Changes and Multifaceted Individual-Level Determinants. Popul. Space Place 2010, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Sun, Q.; Lv, H. The New Rural Pension Scheme, Labor Supply, and the Eldercare Patterns in Rural China. J. Shandong Univ. 2023, 257, 61–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S. The Social and Economic Origins of Immigration. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1990, 510, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.X.; Lin, L.Z.; Sun, K.L. Research on the Influencing Factors of Migrant Workers’ Entrepreneurial Willingness. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2016, 15, 65–77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yi, F.; Wang, X. Urban-Rural Migration in the Digital Era. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2023, 22, 32–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mincer, J.A. Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution. J. Polit. Econ. 1958, 66, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Wen, S. Determinants and Effects of Return Migration in China. Popul. Res. 2017, 41, 71–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.C.; Blomquist, G.C. Mobility and destination in migration decisions: The roles of earnings, quality of life, and housing prices. J. Hous. Econ. 1992, 2, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, G.L.; Mueller, R.E. North American migration: Returns to skill, border effects, and mobility costs. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2004, 86, 988–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinés, D.d.H.; Sadka, E.; Zilcha, I. Topics in Public Economics: Theoretical and Applied Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe, B.; Taylor, M.P. Differences in Opportunities? Wage, Employment and House-Price Effects on Migration. Oxf. B Econ. Stat. 2012, 74, 831–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantinga, A.J.; Detang-Dessendre, C.; Hunt, G.L.; Piguet, V. Housing prices and inter-urban migration. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2013, 43, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganong, P.; Shoag, D. Why has regional income convergence in the US declined? J. Urban Econ. 2017, 102, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, R. The Determinants and Welfare Implications of US Workers’ Diverging Location Choices by Skill: 1980–2000. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 479–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, P.D.; Joseph, G. College-to-work migration of technology graduates and holders of doctorates within the United States. J. Reg. Sci. 2006, 46, 627–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition | Mean | S.D. | Max | Min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Return | 1 = Return; 0 = No return | 0.423 | 0.494 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| Independent variables | Support | 1 = Have support pressure; 0 = No support pressure | 0.476 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| House | 1 = Urban housing; 0 = Non-urban housing | 0.441 | 0.497 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |

| Family characteristics | Income | The logarithm of annual household income (CNY) in 2021 | 11.062 | 1.106 | 13.816 | 0.000 |

| Socialize | The logarithm of mobile phone contacts | 5.109 | 1.168 | 8.700 | 0.000 | |

| Population | Total household size | 4.180 | 1.436 | 11.000 | 1.000 | |

| Abroad | Number of other family members in the city | 1.470 | 0.516 | 2.000 | 0.000 | |

| Land | 1 = Land; 0 = Landless | 0.796 | 0.403 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |

| Individual characteristics | Gender | 1 = Male; 0 = Female | 0.653 | 0.476 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| Age | Individual age | 37.579 | 13.773 | 65.000 | 19.000 | |

| Healthy | 1 = Very bad; 2 = Bad; 3 = General; 4 = Good; 5 = Very good | 4.250 | 0.860 | 5.000 | 1.000 | |

| Education | 1 = Illiterate; 2 = Primary school; 3 = Junior high school; 4 = High school; 5 = College and above | 3.251 | 1.468 | 5.000 | 1.000 | |

| Insurance | 1 = Multiple types of insurance; 0 = No insurance or only basic | 0.400 | 0.490 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |

| Wages | 1 = 0–3000; 2 = 3001–5000; 3 = 5001–8000; 4 = 8001–10,000; 5 = More than 10,000 (CNY) | 1.856 | 1.135 | 5.000 | 1.000 | |

| Awareness | 1 = No know; 2 = Less know; 3 = Generally know; 4 = More know; 5 = Totally know | 1.809 | 1.108 | 5.000 | 1.000 | |

| Marriage | 1 = Married; 0 = Unmarried | 0.559 | 0.497 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |

| Village characteristics | Economic | 1 = The village collective economic income is 100,000 yuan and above in 2021; 0 = The village collective economic income is less than 100,000 yuan in 2021 | 0.581 | 0.494 | 1.000 | 0.000 |

| Flow characteristics | Distance | 1 = Transnational; 2 = Trans-provincial; 3 = Cross-city; 4 = Cross-county; 5 = Within the county | 3.514 | 1.152 | 5.000 | 1.000 |

| Years | Accumulated years of working in cities | 7.700 | 7.398 | 40.000 | 0.080 | |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support | 1.910 *** | 2.621 *** | 2.640 *** | 2.233 *** | ||

| (0.177) | (0.294) | (0.295) | (0.365) | |||

| House | −0.584 *** | −0.478 * | −0.561 ** | −1.051 ** | ||

| (0.170) | (0.257) | (0.283) | (0.432) | |||

| Support × House | 0.928 * | |||||

| (0.562) | ||||||

| Income | 0.014 | 0.080 | 0.283 | 0.344 | 0.309 | 0.296 |

| (0.088) | (0.098) | (0.290) | (0.262) | (0.294) | (0.294) | |

| Socialize | 0.247 *** | 0.183 ** | 0.563 *** | 0.440 *** | 0.592 *** | 0.611 *** |

| (0.076) | (0.075) | (0.127) | (0.111) | (0.132) | (0.134) | |

| Population | 0.083 | 0.091 | −0.065 | −0.054 | −0.055 | −0.062 |

| (0.057) | (0.058) | (0.126) | (0.108) | (0.128) | (0.125) | |

| Abroad | −0.343 ** | −0.494 *** | −0.980 *** | −1.096 *** | −1.030 *** | −1.015 *** |

| (0.166) | (0.153) | (0.284) | (0.253) | (0.289) | (0.292) | |

| Land | −0.421 ** | −0.318 | 0.705 ** | 0.678 ** | 0.697 * | 0.659 * |

| (0.208) | (0.196) | (0.353) | (0.301) | (0.359) | (0.360) | |

| Gender | −0.274 | 0.132 | −0.262 | −0.220 | ||

| (0.329) | (0.285) | (0.330) | (0.334) | |||

| Age | 0.125 *** | 0.123 *** | 0.126 *** | 0.125 *** | ||

| (0.018) | (0.016) | (0.019) | (0.019) | |||

| Healthy | −0.157 | 0.018 | −0.173 | −0.188 | ||

| (0.164) | (0.147) | (0.163) | (0.161) | |||

| Education | −0.634 *** | −0.540 *** | −0.625 *** | −0.618 *** | ||

| (0.111) | (0.101) | (0.111) | (0.110) | |||

| Insurance | −1.779 *** | −1.416 *** | −1.767 *** | −1.788 *** | ||

| (0.325) | (0.282) | (0.325) | (0.328) | |||

| Wages | −0.492 *** | −0.590 *** | −0.446 *** | −0.440 *** | ||

| (0.160) | (0.149) | (0.157) | (0.156) | |||

| Awareness | 0.767 *** | 0.684 *** | 0.746 *** | 0.736 *** | ||

| (0.159) | (0.140) | (0.163) | (0.165) | |||

| Marriage | 0.740 ** | 0.513 | 0.742 ** | 0.734 ** | ||

| (0.368) | (0.320) | (0.374) | (0.372) | |||

| Economic | 1.628 *** | 1.548 *** | 1.554 *** | 1.592 *** | ||

| (0.293) | (0.260) | (0.290) | (0.300) | |||

| Distance | 0.314 ** | 0.268 ** | 0.282 ** | 0.274 ** | ||

| (0.131) | (0.112) | (0.131) | (0.130) | |||

| Years | −0.036 * | −0.040 ** | −0.032 * | −0.031 | ||

| (0.020) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.020) | |||

| Constant | −2.213 ** | −1.289 | −10.581 *** | −9.537 *** | −10.665 *** | −10.331 *** |

| (1.035) | (1.138) | (3.468) | (3.185) | (3.515) | (3.510) | |

| Observations | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1601 | 0.0344 | 0.6216 | 0.5312 | 0.6254 | 0.6282 |

| Variables | Support Pressure | Urban Housing Purchase | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homecoming Behavior | Hometown Connection | Homecoming Behavior | Homecoming Behavior | Trailing Spouse | Homecoming Behavior | |

| Model 5 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 5 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

| Support | 2.640 *** | 1.020 *** | 2.577 *** | |||

| (0.295) | (0.293) | (0.293) | ||||

| House | −0.561 ** | 0.586 *** | −0.276 | |||

| (0.283) | (0.206) | (0.311) | ||||

| Hometown connection | 1.316 ** | |||||

| (0.615) | ||||||

| Trailing spouse | −2.371 *** | |||||

| (0.385) | ||||||

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −10.665 *** | −14.247 *** | −9.771 *** | −10.665 *** | 1.769 | −8.148 ** |

| (3.515) | (3.107) | (3.663) | (3.515) | (1.319) | (3.456) | |

| Observations | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.6254 | 0.7980 | 0.6319 | 0.6254 | 0.2935 | 0.6741 |

| Variables | Homecoming Behavior | Homecoming Intention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 11 | Model 12 | Model 13 | Model 14 | |

| Support | 2.396 *** | 3.119 *** | 1.147 *** | 1.716 *** |

| (0.363) | (0.556) | (0.324) | (0.381) | |

| Plan | 1.234 * | −0.126 | ||

| (0.661) | (0.586) | |||

| Support × Plan | −1.931 * | −2.864 *** | ||

| (1.019) | (0.766) | |||

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −7.221 | −7.887 | 0.062 | 0.704 |

| (4.904) | (6.092) | (2.007) | (2.079) | |

| Observations | 391 | 391 | 391 | 391 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.6514 | 0.6622 | 0.4218 | 0.4550 |

| Variables | Education Level | Household Income | Outflow Distance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High School and Below | Above High School | Low Income | High Income | Movement Outside the City | Movement within the City | |

| Support | 3.213 *** | 2.446 ** | 3.138 *** | 2.579 *** | 2.683 *** | 2.824 *** |

| (0.408) | (1.170) | (0.473) | (0.444) | (0.453) | (0.402) | |

| House | −0.963 *** | 0.028 | 0.0004 | −1.017 ** | −0.663 | −0.674 * |

| (0.370) | (0.618) | (0.426) | (0.435) | (0.485) | (0.375) | |

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | −16.662 *** | −3.285 | −4.889 ** | −9.568 *** | −12.370 *** | −7.396 |

| (2.598) | (4.069) | (2.448) | (2.513) | (3.355) | (5.249) | |

| Observations | 479 | 221 | 304 | 396 | 361 | 339 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.6285 | 0.4855 | 0.6509 | 0.6678 | 0.6449 | 0.5899 |

| Variables | Homecoming Behavior | |

|---|---|---|

| OLS | Probit | |

| Support | 0.264 *** | 1.468 *** |

| (0.027) | (0.156) | |

| House | −0.072 *** | −0.276 * |

| (0.025) | (0.154) | |

| Control variables | YES | YES |

| Constant | −0.510 ** | −5.036 *** |

| (0.215) | (1.496) | |

| Observations | 700 | 700 |

| R2 or pseudo R2 | 0.6143 | 0.6209 |

| Variables | Treatment Group | Control Group | Standard Bias (%) | t Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | 11.053 | 10.988 | 5.900 | 0.760 | 0.445 |

| Socialize | 5.032 | 5.019 | 1.100 | 0.150 | 0.883 |

| Population | 4.162 | 4.146 | 1.100 | 0.140 | 0.891 |

| Abroad | 1.432 | 1.388 | 8.400 | 1.090 | 0.278 |

| Land | 0.804 | 0.829 | −6.200 | −0.810 | 0.416 |

| Gender | 0.711 | 0.717 | −1.300 | −0.170 | 0.862 |

| Age | 39.646 | 38.559 | 8.000 | 0.960 | 0.336 |

| Healthy | 4.245 | 4.155 | 10.500 | 1.320 | 0.186 |

| Education | 3.112 | 3.239 | −8.700 | −1.070 | 0.283 |

| Insurance | 0.391 | 0.366 | 5.100 | 0.650 | 0.517 |

| Wages | 1.689 | 1.649 | 3.600 | 0.530 | 0.595 |

| Awareness | 1.894 | 1.848 | 4.200 | 0.530 | 0.599 |

| Marriage | 0.593 | 0.599 | −1.300 | −0.160 | 0.873 |

| Policy | 0.596 | 0.627 | −6.300 | −0.810 | 0.420 |

| Distance | 3.612 | 3.599 | 1.100 | 0.140 | 0.892 |

| Years | 7.490 | 6.564 | 12.500 | 1.700 | 0.090 |

| Matching Method | Variables | Treatment Group | Control Group | ATT | t Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-to-one matching | Support | 0.630 | 0.373 | 0.258 *** | 4.870 |

| House | 0.377 | 0.483 | −0.106 * | −1.780 | |

| Radius matching | Support | 0.640 | 0.404 | 0.236 *** | 6.170 |

| House | 0.370 | 0.451 | −0.081 * | −1.740 | |

| Kernel matching | Support | 0.630 | 0.389 | 0.242 *** | 6.390 |

| House | 0.377 | 0.460 | −0.082 * | −1.810 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niu, L.; Yuan, L.; Ding, Z.; Zhao, Y. How Do Support Pressure and Urban Housing Purchase Affect the Homecoming Decisions of Rural Migrant Workers? Evidence from Rural China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13081473

Niu L, Yuan L, Ding Z, Zhao Y. How Do Support Pressure and Urban Housing Purchase Affect the Homecoming Decisions of Rural Migrant Workers? Evidence from Rural China. Agriculture. 2023; 13(8):1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13081473

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Lei, Lulu Yuan, Zhongmin Ding, and Yifu Zhao. 2023. "How Do Support Pressure and Urban Housing Purchase Affect the Homecoming Decisions of Rural Migrant Workers? Evidence from Rural China" Agriculture 13, no. 8: 1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13081473

APA StyleNiu, L., Yuan, L., Ding, Z., & Zhao, Y. (2023). How Do Support Pressure and Urban Housing Purchase Affect the Homecoming Decisions of Rural Migrant Workers? Evidence from Rural China. Agriculture, 13(8), 1473. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13081473