Abstract

Promoting rural development is essential for the general economic transformation of people, hence requiring great attention from different government systems. This study assessed the risk, vulnerability, and resilience of agriculture, as well as its impact on sustainable rural economy development, using Greece as the case study. The study employed a quantitative research approach based on a cross-sectional survey design. A survey questionnaire was used to gather data from 304 Greek farmers. The results show that, although farmers are no longer at risk of being short of food and clothing in Greece, they still face different challenges associated with climate change or low productivity, and this can greatly affect yields if not given great attention. The study showed that increasing farmers’ resilience and the efficacy of risk response are both essential tactics to use in order to effectively combat threats to the residential environment. However, the results show that vulnerability in agriculture has a significant negative influence on rural development. This research demonstrates how the development of a new, beautiful nation must involve improvements to and a guarantee of the safety of farmers’ rural living environments, in order to reduce the impacts of risk and vulnerability, as well as strengthen the nation’s resilience. The results show that, in rural governance, the general preservation of living conditions is not only one of farmers’ top priorities, but is also a crucial factor in enhancing their ability to deal with risks, and is the only route to real rural development. Governments should design their social protection programs to enhance agricultural production, safeguard the lives of the most vulnerable populations, strengthen their resilience, and achieve the broadest possible rural transformation.

1. Introduction

Ciampi et al. [1] defines sustainable development as development that seeks to use resources and the environment in such a way that does not jeopardize their use in the future. According to Gil et al. [2], sustainable development involves economic activities that satisfy the demands of the current generation without jeopardizing the capacity of future generations to satiate their needs. The three pillars of economic development, social advancement and environmental preservation form the basis of sustainability [3]. The international community has established a number of initiatives and programs aimed at replacing the current global economic situation in order to achieve sustainable development.

Reardon et al. [4] noted that industrial restructuring, different population-based factors and limited skills greatly affect the population and economic sustainability in most rural areas across Europe. Since the 20th century, the concept of sustainable development has continued to attract the great attention of governments, nonprofit groups, the business world, and academic scholars [5]. The Greek government has implemented a number of steps to stabilize the economic situation and prevent rural farmers from returning to poverty, in order to guarantee property development [6]. In other words, Greece has made resolving the issue of poverty a priority of economic and social growth, and included it under the objectives of creating a generally prosperous society by 2020 [7]. This not only demonstrates the state’s focus on eradicating financial poverty in rural areas, but it also represents a significant advance in this new and unique socialist period, and a development in the strategy and policy established in order to eradicate financial poverty [8,9], which is currently an urgent concern. Most nations have met the targets for poverty reduction outlined in the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development via a number of successful initiatives.

Leal Filho et al. [10] claimed that the idea of rural transformation relates to eradicating poverty and continuing to work towards a better life for those who do so. In the context of Greece’s second century of conflict, the efforts made so far to reduce rural poverty have achieved a crucial victory. The economy and farmers’ living conditions have improved thanks to the development of agricultural technology, and the assistance of the market and the government [11]. Farmers are demanding more from their living environment, and urbanization is speeding up, with home safety now taking precedence. Security difficulties are common for rural residences in Greece, owing to several factors and unforeseen events; these problems have been greatly restricting the growth of rural regions [6]. The ability of housing to support people in these regions is poor, and landslides, floods, and other catastrophes have elevated safety risks [12]. In isolated rural locations with little traffic, it is difficult to carry construction materials such as bricks and tiles to construction sites, and transportation costs have continued to increase, adding to the financial strain and compromising the safety of homes. Finally, in order to develop attractive new rural areas, it is imperative that policymakers move quickly to address the issue of rural housing security [13,14]. On the one hand, the relocation program has been delayed because local administrations have not carefully assessed the farmers’ genuine needs and present living arrangements. Some governments lack the time required to provide farmers with thorough information regarding social protection, and forcible evictions are often carried out [2]. Farmers’ opinions have not changed, and as a consequence, conflicts have developed between the two sides [15,16]. Consequently, after gaining ground against poverty, one of the difficulties that rural governments must confront is how to guarantee the security of the rural living environment and sustain the steady expansion of rural governance [2,17].

Sgroi [18] noted that rural economic development greatly depends on governments taking various measures to create avenues through which rural people can achieve economic freedom. There is, however, limited research on the general vulnerability of farmers in rural areas, the problems they face, and how they are coping with climate change, in relation to rural development. It is therefore important to evaluate the current risks associated with living in rural areas, the vulnerability of farmers, and how to reduce this vulnerability in order to increase resilience.

As such, this study primarily focuses on assessing the risks, vulnerability, and resilience associated with sustainable agriculture as it relates to rural economic development. The specific objectives of the study include the following:

- To determine the effects of agricultural risks on the sustainable development of the rural economy;

- To assess vulnerabilities encountered in agriculture, and their influence on sustainable rural economic development;

- To identify the most resilient agricultural practices and their effects on sustainable rural economic development.

The research hypotheses of this study are as follows:

H1:

Risks in agriculture have a positive effect on sustainable rural economic development.

H2:

There is a significant relationship between vulnerability in agriculture and sustainable rural economic development.

H3:

Resilient agricultural practices positively affect sustainable rural economic development.

This study contributes significantly to the field of rural–urban development, and illuminates the extent to which the different risks encountered in agriculture, the various types of agricultural vulnerability, and the most resilient agricultural practices determine the level of sustainable development in rural areas.

This study represents a novel approach to the field of agriculture and the sustainable development of the rural economy, especially in regard to the effects of risks and resilient agricultural practices, and the negative impacts of agriculture vulnerabilities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Rural Living Conditions

Many societies across the world, including several villages in Iran, face many of the same dangers, such as floods and landslides [19]. Not only is rural housing a valuable asset, but it also contributes significantly to rural finance, which enhances the long-term level of rural economic development [20,21,22]. The processes of rural government are being affected by an increasing number of rural households desiring more expansive development. Implementing rural construction that adheres to the idea of shared development entails completely changing the appearance of the village, improving farmers’ living conditions, and increasing the amount of greenery [23,24]. Rural development is claimed to be sustainable in contexts in which regional resources can be used through agritourism operations [25]. Several of the programs designed to increase rural economic and agricultural output, such as targeted poverty alleviation and the construction of new villages, have aimed to improve the appearance of villages and raise farmers’ living standards, thus allowing them to feel happier and more satisfied [26,27].

Most previous studies have looked at the issues of, and potential solutions to, rural housing development from the perspective of social capital or social resource endowment [7]. By using social capital, which is an endogenous resource, rural communities may promote creativity, find solutions to problems with governance, and achieve political development [28]. There is an unstated law of “mutual causation” between social capital and community governance. However, little research has been conducted on the traits of or variations between rural households’ situations. Hoolachan et al. [29] claimed that some struggling rural inhabitants are unable to improve their living conditions alone due to poor housing, their limited work prospects, and the uncertainty of their sources of income. Greece comprises a large rural area with scattered residential regions, featuring poorly constructed rural houses and out-of-date technology, all of which lead to a high waste of energy and a negative impact on the environment. Thus, it is imperative to find a speedy solution to the problems impacting rural home building [30].

According to experts, rural households in Greece are faced with different challenges related to their inability to withstand disasters, poor or insufficient infrastructure, poor-quality architecture, and a lack of follow-up maintenance leading to poor hygiene conditions [7]. As rural economies have grown and rural urbanization has advanced, several rural towns have begun to implement centralized housing to differing degrees in an effort to optimize resource allocation, sensible land use, and the conservation of arable land [31,32]. The modern European project of urbanization will be severely hampered by a number of social issues, despite the fact that it can improve rural living conditions and expand urban–rural integration to some extent [33,34]. These issues include difficulties with demolition and relocation, as well as with securing pensions, healthcare, and education.

Most governments have responded to housing challenges with different measures, such as relocation [35]. Relocation is an effective policy relating to rural housing security and the renovation of dilapidated houses, is undertaken on a voluntary basis with the unified guidance of the government, and has helped those who live in poor ecological and economic conditions [36]. This has been achieved through planned development resettlements, the reclamation of wastelands or hills suitable for agriculture, the reclamation of forests, the encouragement of urban construction and industrial development, and so on [37]. Although unpredictable factors continue to threaten the safety of farmers in other highly deprived places, certain aspects of rural living conditions have been altered as a consequence of the advocacy and implementation of new agricultural and housing policies [2,36].

2.2. Vulnerability

The characteristics and conditions of a community, a system, or an asset that make it susceptible to catastrophes are classified as vulnerability within the contemporary literature on disaster risk [38,39]. Vulnerability indicates the possibility that future welfare might decline owing to shocks [40]. Clemente-Suárez et al. [41] noted that promoting economic growth requires tackling vulnerabilities that might suddenly push people into severe poverty, in addition to eliminating poverty. Gkatsikos et al. [6] noted that poverty and vulnerability are common in contemporary society, and that vulnerability must be taken into account when addressing problems pertaining to this issue. To put it another way, poverty vulnerability is the likelihood of a family or person experiencing or continuing to experience poverty as a consequence of uncertainty. The most susceptible nations are those that are relatively poor; for instance, Ethiopia’s agricultural sector suffers greatly from recurrent climatic shocks, leading to significant welfare losses for smallholder farmers, despite tremendous efforts being made to the contrary [42,43]. According to Shi and Yang [44], rural human settlements in Greece are at risk due to environmental pollution, inadequate rural education, poor healthcare, and limited social security, among other factors, which all increase the possibility of rural families falling back into poverty.

The founder of economics, Adam Smith, said in The Wealth of Nations that a person’s level of wealth relies on the variety and caliber of their needs, as well as the comforts and entertainments they can access. Living space is one of the most fundamental requirements of rural families. When living space requirements increase, the original living conditions and their quality cease to meet people’s demands. The preference of many rural families to relocate to and construct new homes upon their farms has a considerable determinative effect on the spatial organization of rural areas [45,46]. Additionally, large amounts of wood are needed to build new homes, and as farmers often get their wood from nearby sources, their local forests and ecosystem are negatively impacted. Due to their subsistence lifestyles and strong ties to the land, the majority of rural groups (such as indigenous and other disadvantaged people) experience significant social and cultural limitations. Moreover, there are nonlinear correlations between usage and consequences, and even modest amounts of consumption might result in disruptions to the ecosystem [47]. Poor rural people living on alpine sandy terrain are often affected by the loss or deterioration of ecosystem services brought on by environmental factors such as soil erosion, desertification, and increasingly sandy land [48]. The decline and loss of ecological services makes it difficult to repair buildings, which exacerbates the precariousness of people’s situation. Our capacity to maintain the livelihood and food security of a significant portion of humanity may become compromised if the detrimental impacts of our agricultural practices on the land and environment are not stopped. In other words, as a consequence of complex social, political, and economic processes, as well as natural catastrophes (including historic ones), our vulnerability to risks will increase [49]. Severe poverty can also lead to the breakdown or disintegration of a community’s social and economic institutions in relation to the development of several types of risks [17].

Moreover, resilience and vulnerability have an impact on the long-term livelihoods of farmers and herders in underdeveloped regions [50,51,52]. Sustainable living is defined as the capacity to appease one’s needs without reducing the natural resource base, or the capacity of this base to recover, maintain, and increase capital [53]. Resilience and sustainable development are both intrinsically linked to vulnerability and resilience. By increasing resilience and allowing it to guide practice, vulnerability will be reduced [36,54].

2.3. Resist Adversity

Researchers continually reach the conclusion that contact between humans and the natural environment leads to adaptation. Adaptation involves modifications to both physiology and psychology. Psychologists have become interested in the adaptive changes that people exhibit when faced with difficulties and disappointments. As knowledge of the connection between stress and health has increased, the concept of “resilience” has emerged and become a significant area of study [7,55].

By the 1970s, neurological research had advanced into the areas of “resilience”, dangers, and vulnerabilities, but the focus has remained on the individual’s capacity for psycho-social and genetic environmental adaptation [36,56]. Resilience is often thought of as a personal trait, defined as “the capacity to develop, mature, and gain competence in the face of challenging situations or hurdles”. Elasticity and resilience are related in certain ways. Since the 1980s, resilience has been employed in a wider range of academic fields, such as sociology and anthropology [57]. Research has begun to concentrate on “resilience” in general, especially with regard to the development of resilience during risk-elevating crises. Social risks brought on by uncertainty are a common source of organizational difficulties, and frustration can emerge when the social economy expands quickly [18,58].

Research on “resilience” has shifted its focus from risk tolerance to understanding protective mechanisms and processes, or how these protective factors function. The ability of farmers to withstand adversity and adapt positively to changes is the core of resilience [2,59,60]. Humans are highly adaptable animals that can handle a variety of challenges or emergencies alone. Family is often seen as a protective factor, or environmental element, that promotes the development of personal resilience. Family resilience is based on a process of mending, adjusting, and rebuilding relationships to maintain healthy functioning while dealing with internal and external crises and stresses, in order to support continuous and healthy development. Henry et al. [61] stated that a family becomes resilient when its members adjust and evolve under stress, actively react to crises in idiosyncratic ways, integrate different risk and protective factors, develop a shared understanding, and chart a course for growth. For instance, community resilience is a reflexive strategy that considers how people interact with resources and the environment to deal with risk, and the ways in which resilience is achieved and improved via these interactions [62,63].

Gil et al. [2] highlighted that when farmers’ living conditions are under threat, their first response will be to pursue self-protection. Then, they will decide how best to adapt to the current situation, thus developing a process of dynamic resilience. Farmers who have a narrower capacity to quickly adapt their thinking in response to changes in the external environment, along with an increased sensitivity, will show limited risk tolerance. It will thus be easier for them to fall back into poverty, undermining the efficacy of programs in place to combat this. According to Meuwissen et al. [47], the design of institutional systems with reference to research on pertinent processes and operational modes for work organization and execution should focus closely on home security in rural regions, and particularly in disadvantaged areas. The challenge, however, is to prevent farmers who have improved their financial circumstances from “returning to poverty owing to home security” [64]. If farmers are able to avoid threats and keep themselves and their family safe, they will have a stronger capacity to change their thinking and effectively adjust to external situations. Hence, it is essential to build on prior successes in reducing poverty, and set out higher requirements pertaining to rural modernization, in order to accomplish rural revitalization [65,66].

2.4. Relationships between Resilience, Vulnerability and Sustainability

The concepts of resilience, vulnerability, and sustainability are intricately intertwined in the related literature, and sometimes difficult to discern. Researchers see these phenomena as either complementary, diametrically opposed, or interrelated [2,6]. For instance, Marchese et al. [67] cites persistence as a component of sustainability, which itself includes resilience (the capacity of systems to perpetuate over long periods). Resilience is a necessary but not sufficient condition for sustainability, according to Yin and Ran [68]. According to Romero-Lankao et al. [69], the concepts of sustainability and resilience are distinct but complement one another. Demiroz and Haase [70] do not address the connections between resilience and sustainability, and in investigating regional resilience and resilience-building methods related to economic geography, consider resilience as a standalone concept.

According to Mishra et al. [71], resilience (also known as response capability), together with vulnerability and threat, determines the risk of suffering adverse effects. According to Swami and Parthasarathy [72], vulnerability incorporates exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive ability. While it is not specifically referred to as resilience, this adaptive capability could be interpreted as an example of it, and therefore resilience could be considered an element of vulnerability. Kuhl et al. [73] distinguish between general and impact-specific adaptation capabilities. Gu et al. [74], on the other hand, consider instances of low vulnerability as robust cases, and thus treat resilience as the antithesis of vulnerability.

2.5. Innovation and Climate-Smart Agriculture in Agricultural Resilience and Sustainability

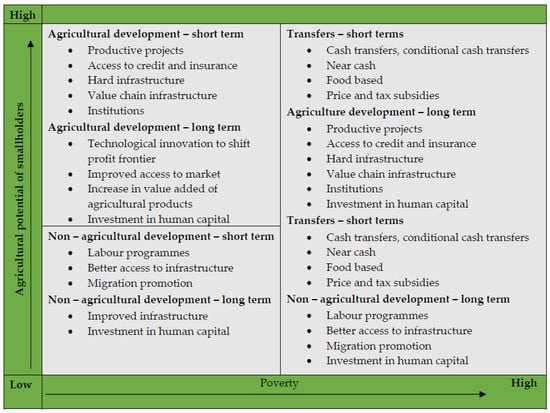

In order to produce more food with fewer resources and enhance the efficiency of external inputs, new strategies for the intensification of sustainable agricultural will be required if food production is to increase significantly in the future [75]. Since agroecology makes better and safer use of pesticides, it may be used to effectively enhance the health of soils, consumers, and farmers. Although many instances of agroecological intensification have recently been reported, significant problems (including scale) still need to be addressed. Agri-food systems are a locus of increased risk due to certain regions’ chronic water scarcity, as well as the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events (heat waves, droughts, and floods) brought on by climate change [76]. Weather-related shocks may have catastrophic and long-lasting effects on the increasingly vulnerable global food system, affecting waste management, production, processing, transport, retail, and disposal. Because of rural agricultural communities’ reliance on the environment and natural resources, their relative poverty, and their sometimes limited access to support networks and safety nets, they are amongst the most susceptible to these effects. The development of climate-smart agriculture (CSA) methods is necessary for these communities so that they can to adapt to such changes [77]. Additionally, local governments will need to take into account off-farm livelihood diversification in order to provide adequate and climate-resilient employment in rural areas (Figure 1). Enhancing the resilience of SSFF requires investments in risk monitoring and early warning systems, as well as environmental preservation, the restoration of ecological biodiversity and damaged systems, as well as the promotion of more effective and sustainable production methods [2].

Onyango et al. [78] noted that using big data technology, geographic information systems, and cutting-edge remote sensing technology may contribute significantly to optimizing input usage and sustainable intensification in smallholder agricultural systems. Blockchain and other distributed ledger technologies may be used to improve the efficiency of agricultural supply chains in a variety of ways, such as by enhancing food safety via improved traceability [1]. Blockchain technology is also a tool for monitoring value distribution throughout the value chain, and thus helps to enhance the standard of living of individuals in lower social strata and aids with the monitoring of important concerns such as child labor. Agriculture development may become more inclusive as a result of technological innovation [6]. New digital tools, which can revolutionize extension services, increase access to markets and inputs, and simplify financial transactions, are being rapidly created and employed by young people. These technologies may also assist rural women in reducing their workload, overcoming obstacles to mobility, and crucially, reclaiming time. Young farmers, livestock keepers, and fishermen may become more resilient in the face of climate change as a result of using simple phone apps that offer access to information on weather pollution and other biophysical factors impacting agricultural output [6,79].

Figure 1.

Prioritizing interventions based on agricultural potential and the level of rural poverty. Source: Kanu et al. [80].

Given the lack of a “one size fits all” policy guideline for very diverse regions, a broad framework for territorial planning and development policy prioritization is outlined in Figure 1. The framework, which is based on national typology, uses two dimensions—the potential for agricultural growth and the relative rate of poverty. For instance, regardless of differences in agricultural potential, short-term priorities are fairly similar across nations and areas with high percentages of rural poverty [81]. In this case, social security programs, such as those related to cash and near cash transfers, food assistance and subsidies, are of the highest priority. On the other hand, long-term investments that create jobs are also essential. The creation of jobs should be at the forefront of efforts to invest in both soft and physical infrastructure in nations and areas with strong agricultural potential, in order to increase agricultural productivity and boost value throughout the agro-food value chain [82,83]. Making loans easier to access is also crucial for boosting investments and productivity [84].

2.6. Summary and Research Gap

According to a review of the relevant literature on rural living environments, vulnerability and resilience, the focus is mainly on how to provide clothing and food for the rural population, how to improve income, and the proposal of appropriate measures, with less focus on the development of risks in the rural living environment. This pertains to whether the focus of the work is on governance for poverty reduction or sustainable development in rural regions. Rural governance is an essential part of the social structure, because it is tasked with resolving such issues as the rural population’s lack of resources, limiting their ability to care for themselves and their houses, and people’s urgent need for protection in the period immediately after the alleviation of severe poverty. Farmers’ genuine needs are often disregarded, leaving them exposed to unforeseen risks or conflicts. As a result, this study, which is based on previous research, applies the rural resilience perspective to the development of new, attractive rural regions, with an emphasis on the emergence of vulnerability and insecurity in rural living environments. In order to maintain the security of rural living environments and consolidate previous victories in the fight against poverty, it examines possible ways to increase rural resilience via the “residential risk–vulnerability–resilience” analytical approach. In order to reduce farmers’ vulnerability and increase their ability to defend themselves from threats, rural society must innovate appropriately. This study is important as it addresses the effects of the risks, vulnerability, and resilience of sustainable agriculture on rural economic development.

3. Materials and Methods

We first had to establish a research design in order to approach our research and lay the groundwork for data collection, measurement and analysis. Many factors can be considered simultaneously thanks to the cross-sectional survey methodology used here. This study has employed quantitative techniques for data collection and hypothesis testing.

The study has primarily targeted different professionals within the Greek agricultural sector. This population was targeted since professionals in the agricultural sector have great knowledge of the risks, vulnerability, and resilience related to sustainable agriculture and the sustainable development of the rural economy.

The determination of the sample size was based on the model of Krejcie and Morgan [85]. We included 304 respondents from different farms in Greece.

Stratified and simple random sampling techniques were utilized. Stratified sampling is essentially a probability sampling technique in which the researcher divides the study target population into discrete subgroups, or “strata”, and then randomly selects a proportion of each stratum for the final sample. Here, the final sample was taken from the strata using a simple random sampling procedure after the target sample had been determined using stratified sampling.

A survey questionnaire was employed in this study to collect data. A questionnaire is more efficient because a huge number of responses can be collected quickly, and it allows the respondents to respond freely to sensitive topics without worrying about the researcher’s judgment. It was assumed that, given their employment in the agricultural sector, they would have a wealth of knowledge relevant to addressing the various goals of the study, and so a questionnaire was used to gather insights into the risks, vulnerability, and resilience of sustainable agriculture in the context of rural economic development.

The variables were operationally defined. For instance, questions concerning the risk, vulnerability, and resilience of agriculture in relation to improving the rural economy were constructed in the form of surveys. To facilitate the creation of an index, these were then transformed into quantifiable and observable components. A Likert scale of 1 to 5 was used, wherein 5 means strongly agree; 4 means agree; 3 means not sure; 2 means disagree; and 1 means strongly disagree.

The data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 20. The collected data were carefully sorted and imported into SPSS for analysis. The results of the analysis have been translated into frequencies and percentages, and are presented in the tables and figures below. To examine associations with a 95% level of confidence, Pearson’s correlation coefficient test was used. In order to determine the general predictive capacity of the various independent factors in relation to the study’s dependent variable, regression analysis was carried out, and a multiple regression model was used to estimate the various predictive values.

Here, the following pertains:

Y = sustainable rural economic development;

β0 = constant (coefficient of intercept);

X1 = risks in agriculture;

X2 = vulnerability;

X3 = resilient agricultural practices;

ε = the model’s error term;

β1 … β3 = the regression coefficient for the independent variables, which enables us to predict business sustainability in times of uncertainty.

The hypotheses of this study were tested and consequently interpreted at the 5% level of significance (0.05); the null hypotheses ewere accepted or rejected based on their p-value.

The purpose of the study was clearly explained to the respondents, and verbal consent was acquired from them. No respondent was forced to give information against their will. Care was also taken to ensure that there was no physical or emotional harm caused to the respondents. To ensure this, the anonymity of the respondents was protected to avoid victimization.

4. Results

This section presents the data analysis, and the interpretation and presentation of the findings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis.

The findings in Table 1 reveal that 61.5% of the respondents were male, and 38.5% of the respondents were female. Most of the participating farmers (36.3%) were in the age bracket of 41–50 years, and only 12.2% were below 30 years old. This indicates that the respondents were more mature in age, suggesting their capacity to provide useful information related to the research subject. Furthermore, the majority (40.8%) had 5–20 years of experience in farming, and only 20.4% had below 5 years’ experience. This means that most of the participating farmers were experienced in farming.

This study established the effects of the different risk types in agriculture on the sustainable development of rural areas, and the results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effects of risks in agriculture on sustainable rural economic development.

Table 2 shows that, regarding the issue of whether businesses’ approaches to coping with climate change represent a major threat to agriculture, the majority of the respondents (57.4%) strongly agreed, and only 1.3% strongly disagreed. With respect to whether soil erosion and biodiversity loss normally affect the final yields of farms, the larger percentage (50.2%) agreed, and 0.9% disagreed. Further, 58.7% agreed that rural agriculture is subjected to the threat of failing to meet customer expectations. The majority of the participants (54.5%) agreed that meeting the rising demands for more food of higher quality represents a great challenge in rural areas, and finally, 44.3% agreed with the risk involved in investing in rural agriculture, given the possibility of low farm productivity and low returns on investments.

The study also assessed the vulnerability encountered in agriculture in relation to sustainable rural economic development, and the results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results on the vulnerability encountered in agriculture.

Table 3 shows that most participants (52.5%) agreed that general exposure to elevated temperatures makes agriculture highly vulnerable. The majority of the participants (75.9%) agreed that vulnerability in agriculture is associated with the sensitivity of crop yields to elevated temperatures. Furthermore, 55.7% felt that some farmers lack the ability to adapt to the various effects of climate change. The majority of the participants (64.5%) agreed that the lack of improved seeds makes most rural farmers vulnerable. Additionally, most respondents (44.3%) agreed that some rural agriculturalists have limited access to water for irrigation. Finally, 64.5% agreed that agriculture is vulnerable due to a lack of knowledge about weather patterns and financial options for purchasing new equipment.

The results about resilient agricultural practices are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Resilient agricultural practices.

In Table 4, the results regarding whether mixed cropping practices in agriculture allow for the efficient use and cycling of soil nutrients show that the majority of the respondents (41.7%) agreed, while 20.9% disagreed. Further, the majority of the participants (42.6%) agreed that vertical integration in agriculture helps to lower the risks associated with the quantity and quality of farming inputs or outputs. Regarding whether contracting in agriculture reduces risk by guaranteeing stable prices or market outlets in advance, the majority (51.3%) agreed, and only 8.6% disagreed. Furthermore, the larger percentage (56.5%) agreed that soil and water conservation, as well as proper community farming, enhance resilience in agriculture. Additionally, more than half of the respondents (60.2%) agreed that resilience in farming encompasses maintaining local agro-biodiversity. Finally, most participants (51.2%) agreed that resilient agriculture necessitates being able to recuperate from different shocks and low productivity.

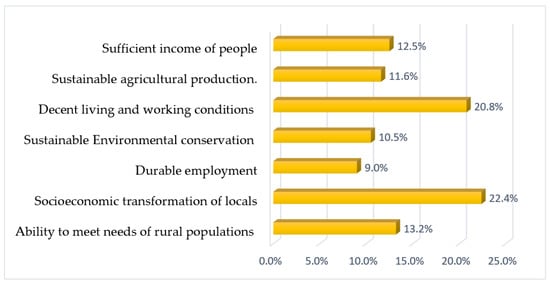

The results regarding sustainable rural economic development are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Aspects of sustainable rural economic development.

The results in Figure 2 show that the socioeconomic advancement of locals (22.4%) is a major aspect of sustainable rural economic development, which is followed by decent living and working conditions (especially for those involved in farming) (20.8%), followed by the ability to meet the needs of rural populations (13.2%), the offering of a sufficient income (12.5%), and sustainable environmental conservation (10.5%). It is important to note that sustainable environmental conditions greatly contribute to supporting both regional economies as well as urban–rural connections.

A correlation analysis revealed the relationships between the study variables, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Cross-tabulation results.

There was a positive correlation between risks in agriculture and sustainable rural economic development (r = 0.715), which is significant at the 0.05 level. There was a positive correlation between vulnerability in agriculture and sustainable rural economic development (r = 0.551), significant at 0.05. Resilient agricultural practices showed a positive correlation with sustainable rural economy development (r = 0.715) at the 0.05 level of significance (p = 0.00 < 0.05).

This regression analysis reveals the degree to which sustainable rural economic development is predicted by risks in agriculture, vulnerability and resilient agricultural practices, and the results are presented in Table 6. We found a positive multiple correlation coefficient (R), which indicates that three of the independent variables in this study are positively correlated with sustainable rural economic development. Additionally, the r-square value confirms that the independent variables in this study contribute to 58.9% of the change seen in sustainable rural economic development.

Table 6.

Model summary.

One-way ANOVA was used to determine whether the three independent variables were the most effective predictors of the dependent variable, and whether the linear regression model effectively fit the data (Table 7). Here, F (3, 135) = 149.136, p < 0.05, indicating that the model and data fit well.

Table 7.

ANOVA analysis.

The unstandardized coefficients obtained after the regression analysis illuminate the relationships between risks in agriculture, vulnerability, resilient agricultural practices and sustainable rural economic development (Table 8).

Table 8.

Regression coefficients.

The beta coefficient of risks in agriculture is 0.196, meaning that a unit change in risks in agriculture may result in a 19.6% change in sustainable rural economic development. Similarly, the beta coefficient of vulnerability in agriculture is 0.184, meaning that any changes in agricultural vulnerabilities will lead to an approximately 18.4% greater negativity in vulnerability in agriculture. The results also show that any change in the use of resilient practices in agriculture will lead to a 21.6% change in sustainable rural economic development. The coefficients clearly show that resilience in agricultural practices is the best predictor of sustainable rural economic development, compared to risks and vulnerability.

Risks in agriculture are not significantly related to sustainable rural economic development (p = 0.104 > 0.05). Hypothesis 1 can therefore be rejected, meaning that risks in agriculture do not have a positive effect on sustainable rural economic development. This means that high levels of risk may represent an obstacle to rural economic development.

Vulnerability in agriculture had a significant negative influence on rural development (p = 0.001 < 0.05). This means that there is a significantly negative relationship between vulnerability in agriculture and sustainable rural economic development. This is an indication that vulnerabilities in agriculture, such as a lack of improved seeds among rural farmers, negatively affect the sustainable development of the rural economy.

Hypothesis 3 was also accepted, as resilient agricultural practices positively affect sustainable rural economic development (p = 0.023 < 0.05). This is an indication that resilience in agriculture has a positive and significant influence on the sustainability of the rural economy.

5. Discussion

This study has focused on risks in agriculture, as well as vulnerability and resilient agricultural practices, and their general impacts on sustainable rural economic development. It shows that the unpredictability of the weather, yields, prices, governmental laws, global markets, and other factors that impact farming may lead to significant changes in agricultural earnings.

The findings show that vulnerabilities in agriculture negatively affect the sustainability of the rural economy, and thus act as an obstacle to rural economic development. With regard to vulnerability, it was revealed that most vulnerabilities in agriculture are associated with the general exposure to elevated temperatures. Furthermore, the sensitivity of crop yields to elevated temperatures is also a key factor. It is also important to note that some farmers lack the ability to adapt to the various effects of climate change, and this affects agricultural yields, which in the long term, affects the level of rural economic transformation. Additionally, vulnerability and resilience have long-term effects on the livelihoods of farmers and herders in impoverished regions [50,51,52]. The ability to meet needs without depleting the natural resource base, as well as its ability to recover, maintain, and increase capital in the face of stress, together define sustainable living [53]. Vulnerability and resilience are intrinsically related to each other, as well as to sustainable development [36,54].

It was revealed in our study that risks related to agriculture do not have a positive effect on sustainable rural economic development. This is an indication that high levels of risk can act as an obstacle to rural economic development. This substantiates risk management’s importance in agriculture, as it helps to mitigate different risks, thereby elevating the sustainability of agriculture and improving long-term economic growth. Risk management entails making decisions that decrease the possible financial repercussions of uncertainties. One source of production risk relates to the unpredictability of plants’ and animals’ natural cycles. This study shows that sustainable development in rural areas relates to the proper management and conservation of the ecosystem’s natural resource base, as well as the enactment of institutional and technological change, to guarantee the satisfaction of human needs. Such sustainable development in the agricultural sector must conserve land, water, and plant- and animal-derived resources, and be ecologically non-damaging, technologically suitable, commercially successful and socially acceptable. As such, it strengthens the economic, social, and environmental sectors in a way that ensures the resilience of food systems and food security, and nourishment for everyone, while maintaining healthy ecosystems for current and future generations [86]. In order to build resilience, the people, institutions, infrastructure, and services related to food systems must be prepared for shocks, manage risks, prevent (reduce) exposure, adapt to a changing risk scenario, and be able to transform when the current food system is no longer viable from an economic, social, or environmental standpoint [6].

In relation to the adaptations required to support family livelihoods, climate resilience has been found to offer workable alternatives within productive systems and increase the potential for improvement. Understanding integrated local and regional dynamics and enacting good policies that can account for biases are the main obstacles encountered when addressing the problems brought about by climate and environmental change. Because of the current intensification of the discussion around climate resilience, some researchers have attempted to connect family farming to the protection of food sovereignty [87]. The OECD notes that the variety of professions, and the close ties that family farmers have to their local ecosystems, may support efforts towards conserving these resources and addressing climate change [88]. Such studies, however, do not seek to elucidate the many facets of climate resilience related to family farming from the standpoint of sustainable rural development. In order to shed light on the micro dynamics at play in this issue, we performed a scoping review of the international literature, utilizing a rigid search and selection approach. In general, we see that local cultural characteristics and biodiversity play major roles in promoting resistance to climate change [89].

This study’s findings show that different practices related to resilience in agriculture have a significant influence on sustainable rural economic development. Resilience-oriented agricultural practices are often described as interconnected solutions based on community experiences, the technology used and management techniques. This is due to the fact that farmers in various settings will show a range of experience, which will affect how they perceive climate risk, and how they adjust to it [2,36]. Unquestionably, the quickest way to boost farmers’ resilience is to make access to agricultural inputs easier, increase the proliferation of technology and equipment, and promote alternate methods of raising and farming animals [90]. Accordingly, farmers often look for technological solutions and management techniques that suit their needs, required outcomes, and resources. Robust and coordinated rural practices are necessary to the long-term sustainable enhancement of agricultural systems in the context of various climatic scenarios. Basic agronomic measures must be taken to preserve balance in ecosystems and prepare for climate change [91].

There are four key areas representing the basic considerations that should be made in order to make agricultural systems more climate-resilient. In order to reduce inequality and poverty from the point of view of sustainable rural development, we must strengthen the social, political, and economic frameworks intrinsic to sustainability [92]. A crucial aspect of climate justice is the amplification of subjects’ voices when setting out policy plans, and the removal of access barriers that restrict family farming. These approaches can be combined with capacity building to more effectively face challenges. The absence of effective policy incentives, market access, and access to credit services, as well as the lack of availability of financial resources, information, and expertise, represent major threats to the resilience of rural communities [55]. This finding is in line with the research that has shown the importance of the quality of local frameworks, and government engagement in risk management and climate change adaptation. Accordingly, further initiations and more focused policies are required in order to address these concerns.

Fatemi et al. [93] observed that, since creating climate resilience policy involves the interests of several sectors and the pursuit of territorial development, the divergence of goals being sought has undermined concerted efforts. Another obstacle relates to the development of comprehensive initiatives that ignore the advancement of climate change and exclude governments, departments, and local organizations. In order to create the space for engagement, production, and communication in relation to climate resilience, the interested parties’ objectives must be addressed.

This research found a correlation between the enhancement of adaptive skills and the availability of high-quality education. Our results demonstrate that education is a crucial factor in decision making in the context of climate change, and contributes substantially to sustainable rural development. As a result, educational initiatives founded on rural extension and technical support services, with the intention to broaden the knowledge, experience, and skills required to meet sustainability concerns, must be undertaken in tandem with policies and activities that promote climate resilience [94].

Assuring the efficiency and resilience of food systems in regions susceptible to multiple systemic risks, stresses, and hazards, such as climatic extremes, calls for immediate, coordinated global action. This is crucial to lessening agriculture’s vulnerability to systemic factors, structural fragility, and compound hazards in these delicate regions [95]. This necessitates a systemized strategy that unifies concerns over health and maximizes the consideration of different areas’ interests, such as offering remedies for food insecurity, malnutrition, violence, epidemics, and the loss of biodiversity. It is important to take into account the structural factors that contribute to increasing hunger and poverty, such as inequality, the unequal access to and distribution of land, gender inequities, and breaches of human rights [96]. This also demands the promotion and facilitation of widespread public engagement in, and co-governance of, food systems. The participation in, co-creation of, and open access to information are the founding principles of tricentric governance, enabling states, social markets, and collective activities to flourish, and thus helping build food systems. In order for resilient food systems to be able to provide food security, nutrition, and high-quality livelihoods for everyone on the planet, and to prevent the degeneration of society, people must be placed at the center; the system must be run from the bottom up, and based on communities. We find that farmers’ capacities to improve their social networks, expertise, and adaptability are similarly constrained by their non-participation in local class-based institutions and organizations. In this context, increasing farmers’ involvement in social groups and organizations built out of networks of local actors is essential to undertaking transformative actions, because it increases their access to financial support, and encourages community mobilization in response to challenges such as extreme climate events [84].

6. Conclusions

The study shows that risks in agriculture, different agricultural vulnerabilities, and resilient practices in agriculture have a great influence on sustainable rural economic development. The results show that rural development, which is intrinsically related to the issue of shared prosperity, depends on the safety of rural farmers’ living environments. Families in agricultural communities are materially vulnerable because of their precarious financial situations and the high costs of repairing their deteriorating homes, which have often been neglected for a long time. The danger of relapsing into poverty has also grown as a result of inadequate insurance coverage, the poor implementation of crucial social measures, and their incompatibility with local realities. The most vulnerable members of society, the resource base, and the ecosphere’s capacity for absorption are all coming under increasing pressure in both developed and developing countries. It is crucial to look into ways to help rural people thrive sustainably by improving their capacity to recover from setbacks. This aforementioned susceptibility becomes more critical in relation to the frequency of natural catastrophes and market risks. Thus, it is crucial to improve farmers’ resilience so they can more effectively deal with risks; this will help ensure the sustainable and steady expansion of Greece’s rural regions. The capacity of rural families to resist risks will be enhanced when their vulnerability is minimized; in contrast, the scope for evading risks among rural households will narrow, making it challenging to ensure safety in their living environment. They may thus revert to poverty, therefore limiting the growth of rural regions and impeding the establishment of shared wealth. There are still certain disparities between rural communities in Greece and those in other developed countries, despite the acceleration of urbanization and economic growth. It is important to pay attention to the development of rural economies, to ensure good communication between the government and communities, and to enable people to vocalize their needs. This study makes a significant contribution to the field of rural urban development, and expands our understanding of how the level of sustainable development in rural areas is influenced by the various risks associated with agriculture, agricultural vulnerabilities, and resilient agricultural practices.

6.1. Recommendations

The following recommendations are based on the aforementioned observations and results.

There are various vulnerabilities that arise in agriculture. For example, farmers often lack quality seeds, and struggle to adjust to the rapidly changing modern world. As such, in order to enhance the quality of life of farmers in these isolated areas, the government and the market must actively develop public infrastructure and service facilities. Additionally, the government should provide farmers with free high-quality seeds, or at least subsidized seeds, that will produce high yields under all climatic conditions.

It is crucial to satisfy the emotional needs of farmers, and to help them cultivate a positively cooperative attitude. In fact, a large number of socioeconomically disadvantaged households do not get enough assistance, since most of the activity of rural governments is focused on material input, with a concentration on project creation and minimal social support.

Nations should include climate-smart agricultural techniques within their curricula, and create the technical, legislative, and investment frameworks required to encourage farming communities to embrace them.

Governments should design their social protection programs in such a way that they support increased agricultural production and employment, safeguard the most vulnerable populations, strengthen resilience, and enable the broadest possible rural transformations.

6.2. Limitations and Areas for Future Research

However, a few limitations must be considered. It is not possible to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the actual situation pertaining to all the rural areas in other parts of Greece due to the constraints of field research and the number of respondents we had. As a consequence, we are limited in our portrayal of the disparities in the living conditions among rural populations throughout Greece, as well as those in family income. These issues will require further investigation in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and C.-I.P.; methodology, S.K.; software, S.K., C.-I.P. and E.L.; validation, S.K. and C.-I.P. and F.C.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, S.K.; data curation, S.K., C.-I.P. and E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K. and C.-I.P.; writing—review and editing, F.C.; supervision, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ciampi, L.; Plumpton, H.J.; Osbahr, H.; Cornforth, R.J.; Petty, C. Building Resilience through Improving Groundwater Management for Sustainable Agricultural Intensification in African Sahel. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2022, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.D.B.; Cohn, A.S.; Duncan, J.; Newton, P.; Vermeulen, S. The Resilience of Integrated Agricultural Systems to Climate Change. WIREs Clim. Change 2017, 8, e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From Its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Stamoulis, K.; Pingali, P. Rural Nonfarm Employment in Developing Countries in an Era of Globalization. Agric. Econ. 2007, 37, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Squaring the Circle? Some Thoughts on the Idea of Sustainable Development. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkatsikos, A.; Natos, D.; Staboulis, C.; Mattas, K.; Tsagris, M.; Polymeros, A. An Impact Assessment of the Young Farmers Scheme Policy on Regional Growth in Greece. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdrolias, L.; Semos, A.; Mattas, K.; Tsakiridou, E.; Michailides, A.; Partalidou, M.; Tsiotas, D. Assessing the Agricultural Sector’s Resilience to the 2008 Economic Crisis: The Case of Greece. Agriculture 2022, 12, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhuo, Y. The Necessary Way for the Development of China’s Rural Areas in the New Era-Rural Revitalization Strategy. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 6, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. Innovating to Zero the Building Sector in Europe: Minimising the Energy Consumption, Eradication of the Energy Poverty and Mitigating the Local Climate Change. Sol. Energy 2016, 128, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Tripathi, S.K.; Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.D.; Giné-Garriga, R.; Orlovic Lovren, V.; Willats, J. Using the Sustainable Development Goals towards a Better Understanding of Sustainability Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, C.-I.; Loizou, E.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Michailidis, A.; Karelakis, C.; Fallas, Y.; Paltaki, A. What Makes Farmers Aware in Adopting Circular Bioeconomy Practices? Evidence from a Greek Rural Region. Land 2023, 12, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, E.; Ray-Bennett, N.S. Disaster Risk Governance for District-Level Landslide Risk Management in Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 59, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsharzade, N.; Papzan, A.; Ashjaee, M.; Delangizan, S.; Van Passel, S.; Azadi, H. Renewable Energy Development in Rural Areas of Iran. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiyaremye, A.; Kruss, G.; Booyens, I. Innovation for Inclusive Rural Transformation: The Role of the State. Innov. Dev. 2020, 10, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Heerink, N.; Feng, S.; Shi, X. Farmland Tenure in China: Comparing Legal, Actual and Perceived Security. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzoska, M.; Fröhlich, C. Climate Change, Migration and Violent Conflict: Vulnerabilities, Pathways and Adaptation Strategies. Migr. Dev. 2016, 5, 190–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Li, Y. Targeted Poverty Alleviation and Land Policy Innovation: Some Practice and Policy Implications from China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, F. The Circular Economy for Resilience of the Agricultural Landscape and Promotion of the Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 8, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvin, M.; Beiki, P.; Hejazi, S.J.; Sharifi, A.; Atashafrooz, N. Assessment of Infrastructure Resilience in Multi-Hazard Regions: A Case Study of Khuzestan Province. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 88, 103601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkartzios, M.; Scott, M. Placing Housing in Rural Development: Exogenous, Endogenous and Neo-Endogenous Approaches. Sociol. Rural. 2014, 54, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenle, A.A. Assessment of Solar Energy Technologies in Africa-Opportunities and Challenges in Meeting the 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, B.; Liaghat, A.; Akbari, M.R.; Keshavarz, M. Irrigation Water Management in Iran: Implications for Water Use Efficiency Improvement. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 208, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, H.; Cui, W. Community-Based Rural Residential Land Consolidation and Allocation Can Help to Revitalize Hollowed Villages in Traditional Agricultural Areas of China: Evidence from Dancheng County, Henan Province. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahza, A.; Asmit, B. Regional Economic Empowerment through Oil Palm Economic Institutional Development. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2019, 30, 1256–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, N.; Liargovas, P.; Stavroyiannis, S.; Makris, I.; Apostolopoulos, S.; Petropoulos, D.; Anastasopoulou, E. Sustaining Rural Areas, Rural Tourism Enterprises and EU Development Policies: A Multi-Layer Conceptualisation of the Obstacles in Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Yuan, X.; Yao, X. Synthesize Dual Goals: A Study on China’s Ecological Poverty Alleviation System. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1042–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, J.; Shuai, J.; Nelson, H.; Walzem, A.; Cheng, J. Linking Social-Psychological Factors with Policy Expectation: Using Local Voices to Understand Solar PV Poverty Alleviation in Wuhan, China. Energy Policy 2021, 151, 112160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.; Seferiadis, A.A.; Maas, J.; Bunders, J.F.G.; Zweekhorst, M.B.M. Knowledge, Social Capital, and Grassroots Development: Insights from Rural Bangladesh. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 55, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoolachan, J.; McKee, K.; Moore, T.; Soaita, A.M. ‘Generation Rent’ and the Ability to ‘Settle down’: Economic and Geographical Variation in Young People’s Housing Transitions. J. Youth Stud. 2017, 20, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Taweekun, J.; Techato, K.; Waewsak, J.; Gyawali, S. GIS Based Site Suitability Assessment for Wind and Solar Farms in Songkhla, Thailand. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzad, H.; Barati, A.A.; Ehteshammajd, S.; Goli, I.; Siamian, N.; Moghaddam, S.M.; Pour, M.; Tan, R.; Janečková, K.; Sklenička, P.; et al. Agricultural Land Tenure System in Iran: An Overview. Land Use Policy 2022, 123, 106375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Luan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Su, M. Relationship between Urban Construction Land Expansion and Population/Economic Growth in Liaoning Province, China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Chen, W.Y.; Sanesi, G.; Lafortezza, R. The European Union Roadmap for Implementing Nature-Based Solutions: A Review. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 121, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.N.; Khan, M.; Han, K. Towards Sustainable Smart Cities: A Review of Trends, Architectures, Components, and Open Challenges in Smart Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, S.M. Urban Vulnerability, Disaster Risk Reduction and Resettlement in Mzuzu City, Malawi. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 22, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shen, R. Rural Settlement Development in Western China: Risk, Vulnerability, and Resilience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneibel, A.; Stellmes, M.; Röder, A.; Frantz, D.; Kowalski, B.; Haß, E.; Hill, J. Assessment of Spatio-Temporal Changes of Smallholder Cultivation Patterns in the Angolan Miombo Belt Using Segmentation of Landsat Time Series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 195, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, B.E.O.; Goldenfum, J.A.; Michel, G.P.; de Cavalcanti, J.R.A. Terminology of Natural Hazards and Disasters: A Review and the Case of Brazil. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 52, 101970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathne, A.Y.; Lee, G. Developing a Multi-Facet Social Vulnerability Measure for Flood Disasters at the Micro-Level Assessment. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulú, I.; Razumova, M.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Sastre, F. Measuring Risks and Vulnerability of Tourism to the COVID-19 Crisis in the Context of Extreme Uncertainty: The Case of the Balearic Islands. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Navarro-Jiménez, E.; Moreno-Luna, L.; Saavedra-Serrano, M.C.; Jimenez, M.; Simón, J.A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social, Health, and Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofu, D.A.; Woldeamanuel, T.; Haile, F. Smallholder Farmers’ Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change Induced Shocks: The Case of Northern Ethiopia Highlands. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 8, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amare, A.; Simane, B.; Nyangaga, J.; Defisa, A.; Hamza, D.; Gurmessa, B. Index-Based Livestock Insurance to Manage Climate Risks in Borena Zone of Southern Oromia, Ethiopia. Clim. Risk Manag. 2019, 25, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yang, X. Sustainable Development Levels and Influence Factors in Rural China Based on Rural Revitalization Strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Hao, P.; Huang, X. Land Conversion and Urban Settlement Intentions of the Rural Population in China: A Case Study of Suburban Nanjing. Habitat Int. 2016, 51, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geall, S.; Shen, W. Gongbuzeren Solar Energy for Poverty Alleviation in China: State Ambitions, Bureaucratic Interests, and Local Realities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 41, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, M.P.M.; Feindt, P.H.; Spiegel, A.; Paas, W.; Soriano, B.; Mathijs, E.; Balmann, A.; Urquhart, J.; Kopainsky, B.; Garrido, A.; et al. SURE-Farm Approach to Assess the Resilience of European Farming Systems. In Resilient and Sustainable Farming Systems in Europe; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. The Nexus between Regional Eco-Environmental Degradation and Rural Impoverishment in China. Habitat Int. 2020, 96, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, K.; Kilar, V.; Koren, D. Resilience Assessment of Complex Urban Systems to Natural Disasters: A New Literature Review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masunungure, C.; Shackleton, S. Exploring Long-Term Livelihood and Landscape Change in Two Semi-Arid Sites in Southern Africa: Drivers and Consequences for Social–Ecological Vulnerability. Land 2018, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Feng, X. Livelihood Resilience of Vulnerable Groups in the Face of Climate Change: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Dev. 2022, 44, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M.; Maleksaeidi, H.; Karami, E. Livelihood Vulnerability to Drought: A Case of Rural Iran. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 21, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.P. Pathways of Adaptation to External Stressors in Coastal Natural-Resource-Dependent Communities: Implications for Climate Change. World Dev. 2018, 108, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Andersson, E.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Olsson, P.; Gaffney, O.; Takeuchi, K.; Folke, C. Sustainability and Resilience for Transformation in the Urban Century. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murken, L.; Gornott, C. The Importance of Different Land Tenure Systems for Farmers’ Response to Climate Change: A Systematic Review. Clim. Risk Manag. 2022, 35, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez García, J.L.; Pérez Ruiz, S. Development of Capabilities from the Innovation of the Perspective of Poverty and Disability. J. Innov. Knowl. 2017, 2, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, J. Analysis of the Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Urban Resilience in Four Southern Regions of Xinjiang. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylund, P.L.; McCaffrey, M. A Theory of Entrepreneurship and Institutional Uncertainty. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Kalfas, D.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. The Impact of Collaborative Communication on the Physical Distribution Service Quality of Soft Drinks: A Case Study of Beverage Manufacturing Companies in Greece. Beverages 2022, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkunas, M.; Žičkienė, A.; Baležentis, T.; Volkov, A.; Štreimikienė, D.; Ribašauskienė, E. Challenges for Improving Agricultural Resilience in the Context of Sustainability and Rural Development. Probl. Ekorozw. 2022, 17, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.S.; Sheffield Morris, A.; Harrist, A.W. Family Resilience: Moving into the Third Wave. Fam. Relat. 2015, 64, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroogh, S.; Esmalian, A.; Donaldson, J.; Mostafavi, A. Empathic Design in Engineering Education and Practice: An Approach for Achieving Inclusive and Effective Community Resilience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, F.E. Community Resilience through Entrepreneurship: The Role of Gender. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2017, 11, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Kontsas, S.; Konteos, G.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. Investigation of the Redesigning Process of the Development Identity of a Local Government Regional Unit (City): A Case Study of Kozani Regional Unit in Greece. In Advances in Quantitative Economic Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, N.; Martin, A.; Sikor, T. Green Revolution in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications of Imposed Innovation for the Wellbeing of Rural Smallholders. World Dev. 2016, 78, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Ali, A.; Galaski, K. Mobilizing Knowledge: Determining Key Elements for Success and Pitfalls in Developing Community-Based Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1547–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, D.; Reynolds, E.; Bates, M.E.; Morgan, H.; Clark, S.S.; Linkov, I. Resilience and Sustainability: Similarities and Differences in Environmental Management Applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613–614, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Ran, W. Supply Chain Diversification, Digital Transformation, and Supply Chain Resilience: Configuration Analysis Based on FsQCA. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Lankao, P.; Gnatz, D.; Wilhelmi, O.; Hayden, M. Urban Sustainability and Resilience: From Theory to Practice. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiroz, F.; Haase, T.W. The Concept of Resilience: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Emergency and Disaster Management Literature. Local Gov. Stud. 2019, 45, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Anderson, K.; Miller, B.; Boyer, K.; Warren, A. Microgrid Resilience: A Holistic Approach for Assessing Threats, Identifying Vulnerabilities, and Designing Corresponding Mitigation Strategies. Appl. Energy 2020, 264, 114726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, D.; Parthasarathy, D. Dynamics of Exposure, Sensitivity, Adaptive Capacity and Agricultural Vulnerability at District Scale for Maharashtra, India. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, L.; Van Maanen, K.; Scyphers, S. An Analysis of UNFCCC-Financed Coastal Adaptation Projects: Assessing Patterns of Project Design and Contributions to Adaptive Capacity. World Dev. 2020, 127, 104748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Chen, A. Performance of Transportation Network under Perturbations: Reliability, Vulnerability, and Resilience. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 133, 101809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q. Prospects for Agricultural Sustainable Intensification: A Review of Research. Land 2019, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaupp, F. Extreme Events in a Globalized Food System. One Earth 2020, 2, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Loizou, E.; Melfou, K.; Papaevangelou, O. Assessing Relationship Between Entrepreneurship Education and Business Growth. In Business Development and Economic Governance in Southeastern Europe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Onyango, C.M.; Nyaga, J.M.; Wetterlind, J.; Söderström, M.; Piikki, K. Precision Agriculture for Resource Use Efficiency in Smallholder Farming Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Savvidou, S.; Papaevangelou, O.; Pakaki, F. Role of Management in Optimising the Quality of Education in Educational Organisations. In Advances in Quantitative Economic Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Kanu, B.S.; Salami, A.O.; Numasawa, K. Inclusive Growth: An Imperative for African Agriculture. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2014, 14, A33. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.; Gasparatos, A. Multi-Dimensional Energy Poverty Patterns around Industrial Crop Projects in Ghana: Enhancing the Energy Poverty Alleviation Potential of Rural Development Strategies. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, S.; Santander, M.; Useche, P.; Contreras, C.; Rodríguez, J. Aligning Strategic Objectives with Research and Development Activities in a Soft Commodity Sector: A Technological Plan for Colombian Cocoa Producers. Agriculture 2020, 10, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenle, A.A.; Manning, L.; Azadi, H. Agribusiness Innovation: A Pathway to Sustainable Economic Growth in Africa. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 59, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfas, D.; Kalogiannidis, S.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Toska, E. Urbanization and Land Use Planning for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Case Study of Greece. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Toska, E.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Kalfas, D. Using School Systems as a Hub for Risk and Disaster Management: A Case Study of Greece. Risks 2022, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegler, E.; O’Neill, B.C.; Hallegatte, S.; Kram, T.; Lempert, R.J.; Moss, R.H.; Wilbanks, T. The Need for and Use of Socio-Economic Scenarios for Climate Change Analysis: A New Approach Based on Shared Socio-Economic Pathways. Glob. Environ. Change 2012, 22, 807–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Zhen, L.; Yu, X.; Bakker, M.; Carsjens, G.-J.; Xue, Z. Assessing the Influences of Ecological Restoration on Perceptions of Cultural Ecosystem Services by Residents of Agricultural Landscapes of Western China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernard, M.; Comunian, R.; Gross, J. Cultural and Creative Ecosystems: A Review of Theories and Methods, towards a New Research Agenda. Cult. Trends 2022, 31, 332–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyasimi, M.; Kimeli, P.; Sayula, G.; Radeny, M.; Kinyangi, J.; Mungai, C. Adoption and Dissemination Pathways for Climate-Smart Agriculture Technologies and Practices for Climate-Resilient Livelihoods in Lushoto, Northeast Tanzania. Climate 2017, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Melfou, K.; Kontogeorgos, A.; Kalogiannidis, S. Exploring Key Aspects of an Integrated Sustainable Urban Development Strategy in Greece: The Case of Thessaloniki City. Smart Cities 2022, 6, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, L.J.; Boonstra, W.J.; Peterson, G.D.; Schlüter, M. Traps and Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Review. World Dev. 2018, 101, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, M.N.; Okyere, S.A.; Diko, S.K.; Kita, M. Multi-Level Climate Governance in Bangladesh via Climate Change Mainstreaming: Lessons for Local Climate Action in Dhaka City. Urban Sci. 2020, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan-Diab, F.; Molinari, C. Interdisciplinarity: Practical Approach to Advancing Education for Sustainability and for the Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, W.; Ait-Aissa, S.; Burgess, R.M.; Busch, W.; Creusot, N.; Di Paolo, C.; Escher, B.I.; Mark Hewitt, L.; Hilscherova, K.; Hollender, J.; et al. Effect-Directed Analysis Supporting Monitoring of Aquatic Environments—An in-Depth Overview. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 544, 1073–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.; Mukherjee, A. No Empowerment without Rights, No Rights without Politics: Gender-Equality, MDGs and the Post-2015 Development Agenda. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2014, 15, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).