Tourism Development in the Framework of Endogenous Rural Development Programmes—Comparison of the Case Studies of the Regions of La Vera and Tajo-Salor (Extremadura, Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Objetives and Approach of the Research

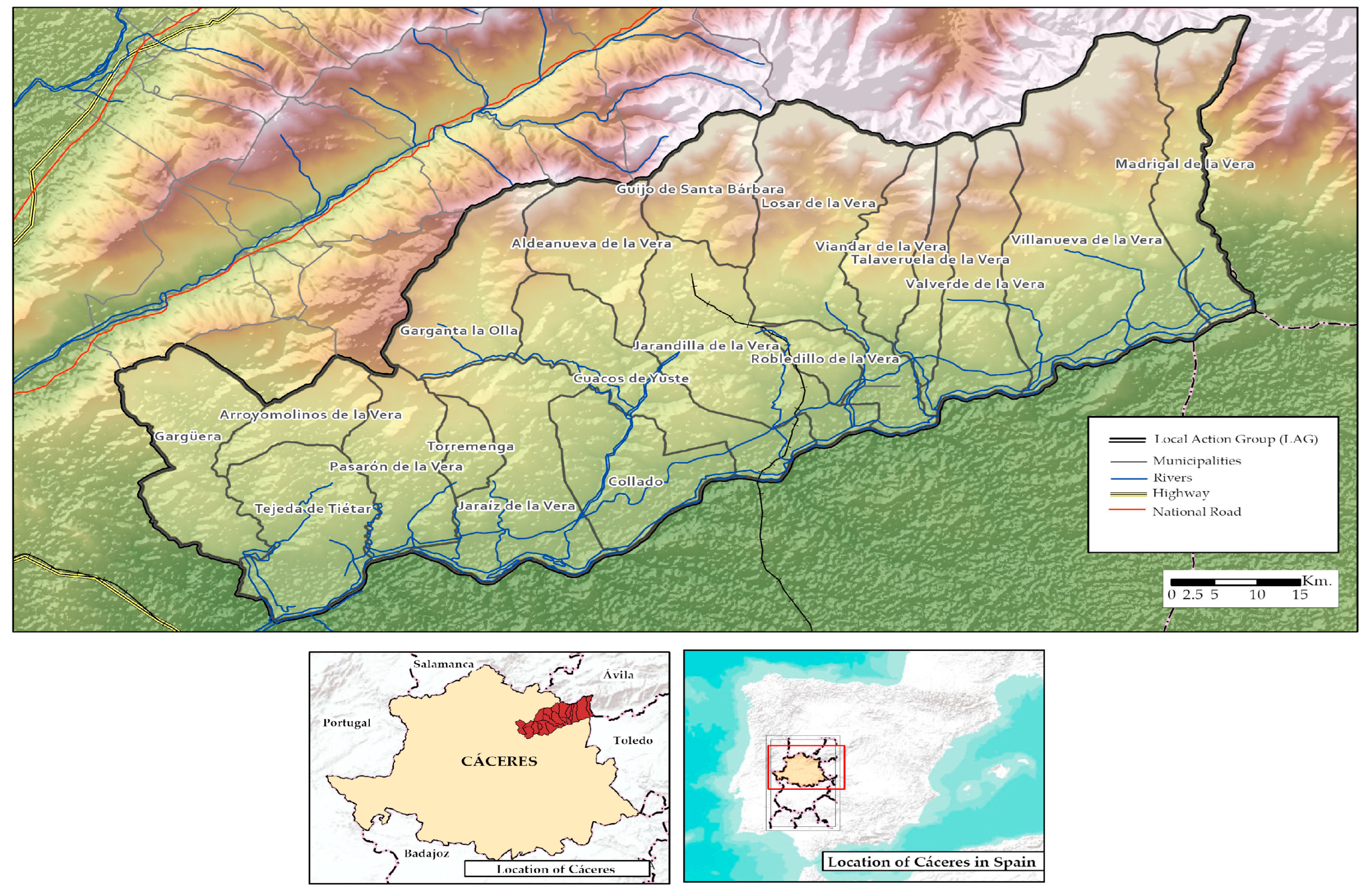

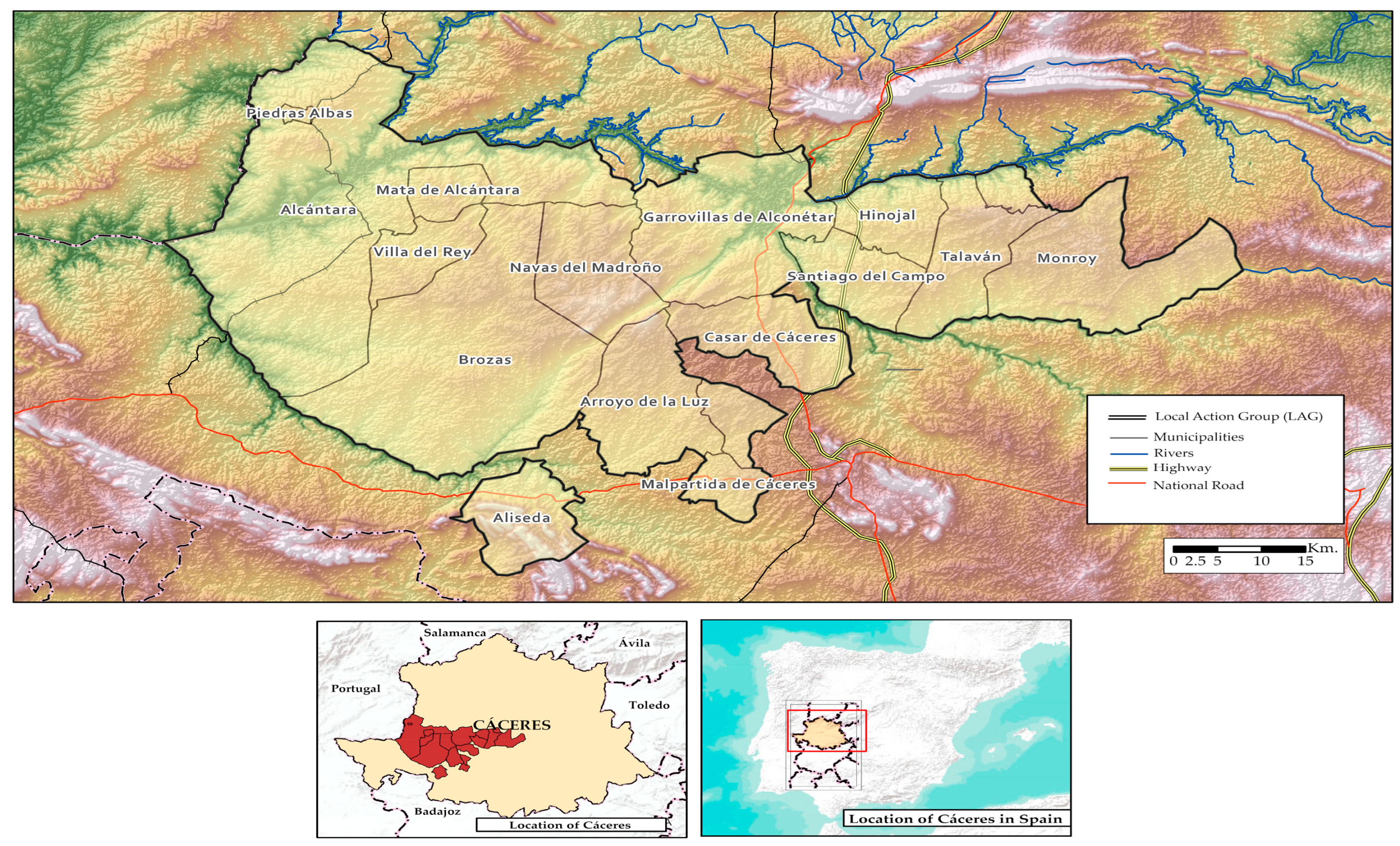

2. The Counties of La Vera and Tajo-Salor as the Subject of A Case Study

3. Time Frame and Methodology of Research

3.1. Time and Scope of the Investigation

3.2. Methodology and Phases of Research

- (1)

- A preliminary phase of contact with the technical staff of the associations that managed the programmes under analysis, as well as a study of the development strategies employed, especially those relating to the promotion of tourism. The investments made were analysed and quantified, their distribution by lines of action, the relevance of public investments within the measure for the promotion of rural tourism, the objectives of these actions and their synergies with private investments. Additionally, in this phase, with the aim of tackling a second stage of the fieldwork, the contact details of the tourism promoters who received subsidies from the programme’s funds were located.

- (2)

- Analysis of tourism projects implemented and interviews with their promoters. In his studies on qualitative research, Yin [115] defends the usefulness of interviews as a research tool and source of information. He argues that the interview allows interaction with the interviewee, contextualising his or her opinions, and thus optimising the understanding of the information and assessments offered by the interviewee. Given the large number of private projects carried out during the three six-year periods under analysis, it was necessary to select a sample of them on the basis of the following criteria: (1) that most of the investment was private; (2) that the subsidy received had a minimum amount of €12,000; and (3) that this subsidy had a certain relevance in the overall investment made, representing at least one fifth of the project. As a result of the application of these criteria, a total of 42 projects were selected for the region of La Vera (Table 2) and 23 for Tajo-Salor (Table 3). Table 2 and Table 3 show the total number of private tourism projects implemented with those selected in the sample, as well as the relative importance of the latter in the total investment in the promotion of rural tourism.

- (1)

- Triangulation of results. Given the qualitative nature of the research and the long period of time that elapsed between the implementation of the projects and the interviews, in order to avoid any biases that might have been incurred by the interviewees, a final stage of the fieldwork consisted of contrasting the conclusions initially obtained in the two previous phases with the assessment offered by the main technical managers of the programmes. They are privileged witnesses to the evolution of their counties and the development strategy applied to them.

4. Results

4.1. Implementation of Development Strategies in the Regions of La Vera and Tajo-Salor:

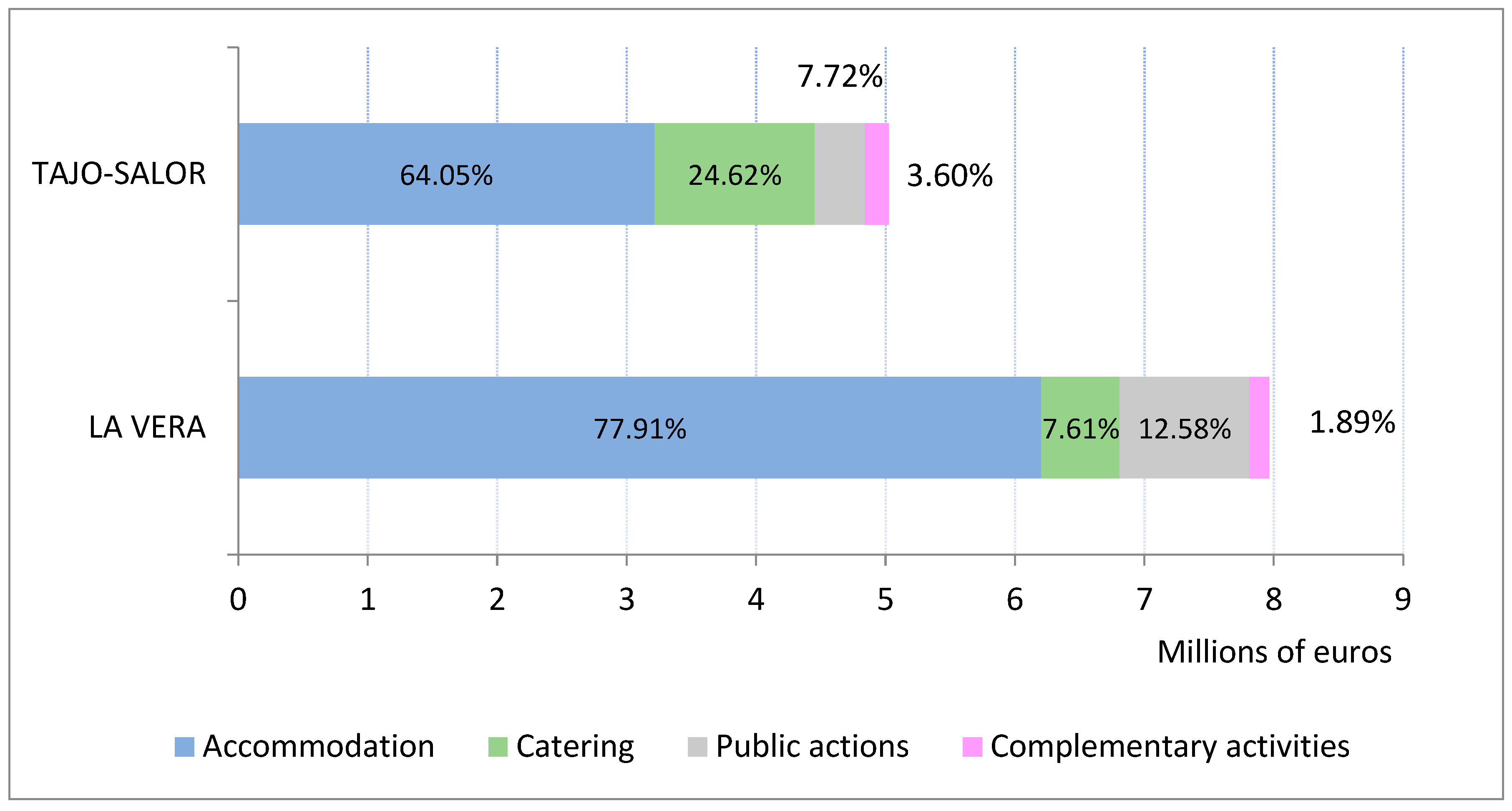

4.1.1. Relevance of Investment in The Promotion of Rural Tourism

4.1.2. Distribution, by Type of Activity, of Investment Earmarked for The Promotion of Rural Tourism

4.2. Failed Tourism Projects

4.3. Profile of Tourism Promoters

4.4. Interviews with Promoters

4.4.1. How Does the Existence of Subsidies Condition the Implementation of Private Investments in The Tourism Sector?

4.4.2. Promoters’ Assessment of the Viability of Their Investments

4.4.3. Situation of The Rural Tourism Sector in The Regions of Tajo-Salor and La Vera: Main Handicaps

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Guidelines for European Agriculture; COM (81) 608 Final; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Perspectives for the Common Agricultural Policy; The Green Paper of the Commission; Green Europe News Flash 33, COM (85) 333; Communication of the Commission to the Council and the Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The Future of Rural Society; COM (88) 501; Bulletin of the European Communities, Supplement 4/88; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Notice to Member States Laying Down Guidelines for Integral Global Grants for Which the Member States Are Invited to Submit Proposals in the Framework of a Comunity Initiative for Rural Development (91/C 73/14); DOCE, no.73/33; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación Europea de Información sobre el Desarrollo Local (AEIDL). La Financiación Local en Los Territorios Rurales; Cuaderno nº 9; Observatorio Europeo Leader: Bruselas, Bélgica, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. Programa Nacional Proder I; MAPA: Madrid, Spain, 1996.

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación. Real Decreto 2/2002, de 11 de Enero, Por el que se Regula la Aplicación de la Iniciativa Comunitaria “Leader Plus” y Los Programas Operativos Integrados y en Los Programas de Desarrollo Rural (PRODER); BOE, no 11, de 12 de enero de 2002; MAPA: Madrid, Spain, 2002.

- Asociación Europea de Información sobre el Desarrollo Local (AEIDL). La Competitividad Territorial. Construir una Estrategia de Desarrollo Territorial con Base en la Experiencia de Leader; Cuaderno nº 6; Observatorio Europeo Leader: Bruselas, Bélgica, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Musto, S. Endogenous Development. A Myth or a Path? Problems of Economic Self-Reliance in the European Periphery; EADE Books Series, nº 5; German Development Institute: Berlin, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Etxezarreta, M. Desarrollo Rural Integrado; MAPA: Madrid, Spain, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zapatero, J.; Sánchez, M.J. Instrumentos específicos para el desarrollo rural integrado: La Iniciativa Comunitaria Leader y el Programa Operativo Proder. Polígonos 1999, 8, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, J. Los modelos de desarrollo regional y el desarrollo de Extremadura. Alcántara 1991, 22, 147–180. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, M. La diversificación en el medio rural como factor de desarrollo. Pap. Geogr. 2002, 36, 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Barke, M.; Newton, M. The EU Leader Initiative and endogenous rural development: The application of the programme in two rural areas of Andalusia; Southern Spain. J. Rural Stud. 1997, 13, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparcia, J.; Noguera, J. Reflexiones en torno al territorio y al desarrollo rural. In El Desarrollo Rural en la Agenda 2000; Ramos, E., Ed.; MAPA: Madrid, Spain, 1999; pp. 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cebrián, A. Génesis, método y territorio del desarrollo rural con enfoque local. Pap. Geogr. 2003, 38, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, F. El desarrollo local, una aplicación geográfica. Exploración teórica e indagación sobre su práctica. Eria 1996, 39–40, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I.; Díaz, J.M. La Iniciativa Comunitaria Leader como modelo de desarrollo rural: Aplicación a la región capital de España. Agrociencia. 2005, 39, 697–708. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood: Westport, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. The prosperous community Social capital and public life. Am. Prospect. 1993, 4, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Putman, R. Tuning in, tuning out. The strange disappearance of social capital in America. Political Sci. Politics 1995, 28, 664–683. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcock, M. Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory Soc. 1998, 27, 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, F.; Moyano, E. Capital social y desarrollo en zonas rurales. Un análisis de los programas Leader II y Proder en Andalucía. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2002, 60, 67–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buciega, A. Capital Social en el Marco de Los Grupos para el Desarrollo Rural Leader: Análisis de Casos en la Provincia de Valencia; Universitat de València, Instituto Interuniversitario de Desarrollo Local: Valencia, España, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Esparcia, J.; Escribano, J.; Serrano, J. Una aproximación al enfoque del capital social y a su contribución al estudio de los procesos de desarrollo local. Investig. Reg. 2016, 34, 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Saz-Gil, M.I.; Gómez-Quintero, J.D. Una aproximación a la cuantificación del capital social: Una variable relevante en el desarrollo de la provincia de Teruel, España. EURE 2015, 41, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortall, S. Social or Economic Goals, Civic Inclusion or Exclusion? An Analysis of Rural Development Theory and Practice. Sociol. Rural. 2004, 44, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiberteau, A. Fortalezas y debilidades del modelo de desarrollo rural por los actores locales. In Nuevos Horizontes en el Desarrollo Rural; Coord Márquez, D., Ed.; Universidad Internacional de Andalucía. AKAL: Madrid, España, 2002; pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, F.; Woods, M.; Cejudo, E. The Leader Iniciative has been a victim of its own success. The decline of the bottom-up approach in rural development programmes. The cases of Wales and Andalusia. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osti, G. LEADER and Partnerships: The Case of Italy. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparcia, J.; Noguera, J.; Pitarch, M.D. LEADER en España: Desarrollo rural, poder, legitimación aprendizaje y nuevas estructuras. Doc. Anal. Geogr. 2000, 37, 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, F.; Cejudo, E.; Maroto, J.C. Reflexiones en torno a la participación en el desarrollo rural. ¿Reparto social o reforzamiento del poder? LEADER y PRODER en el sur de España. EURE 2014, 40, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukic, A.; Obad, O. New Actors in Rural Development-The LEADER Approach and Projectification in Rural Croatia. Sociol. Space 2016, 1, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cejudo, E.; Navarro, F.A.; Camacho, J.A. Perfil de los beneficiarios de los programas de desarrollo rural en Andalucía. Leader + y Proder II (2000–2006). Cuad. Geogr. 2017, 56, 155–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bryden, J.; Munro, G. New approaches to economic development in peripheral rural regions. Scott. Geogr. J. 2000, 116, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.A. Los Intangibles en el Desarrollo Rural; Universidad de Extremadura: Cáceres, España, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, F.J.; Nieto, A.; Castro-Serrano, J. Intangibles of Rural Development. The Case Study of La Vera (Extremadura, Spain). Land 2020, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, J. Tourism and development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Patmore, J. Recreation and Resources, Leisure Patterns and Leisure Places; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.; Hall, C.M.; Jenkins, J. (Eds.) Tourism and Recreation in Rural Areas; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, B. What is rural tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Roberts, L. Rural Tourism: 10 Years on. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, R.; Long, P.; Allen, L. Rural resident tourism perceptions and attitudes. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, G.; Citro, E.; Salvia, R. Economic and Social Sustainable Synergies to Promote Innovations in Rural Tourism and Local Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, I.; Oroian, C.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.; Porutiu, A.; Chiciudean, G.; Todea, A.; Lile, R. Local Residents Attitude toward Sustainable Rural Tourism Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, I.; Harun, R.; Arion, F.; Oroian, C.; Dumitras, D.; Mihai, M.; Ilea, M.; Chiciudean, D.; Gigla, I.; Chiciudean, G. Residents Perception of Destination Quality: Key Factors for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, E.; Navarro, F.A. La inversión en los programas de desarrollo rural. Su reparto territorial en la provincia de Granada. In Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense; Universidad Complutense: Madrid, Spain, 2009; Volume 29, pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, C.; De la Fuente, M.T. Las estrategias de desarrollo rural: Valoración del Proder en Cantabria. In Actas del X Coloquio de Geografía Rural; Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, Grupo de Geografía Rural: Ciudad Real, Spain, 2000; pp. 623–634. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz, E.; Frutos, L.M.; Climent, E. La iniciativa comunitaria Leader II y el desarrollo rural: El caso de Aragón. Geographicalia 2000, 38, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Alario, M.; Baraja, E. Políticas públicas de desarrollo rural en Castilla y León: ¿Sostenibilidad consciente o falta de opciones? Leader II. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2006, 41, 267–293. [Google Scholar]

- Alberdi, J.C. El medio rural en la agenda empresarial: La difícil tarea de hacer partícipe a la empresa del desarrollo rural. Investig. Geográficas 2008, 45, 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, A.; Cárdenas, G. Towards Rural Sustainable Development? Contributions of the EAFRD 2007–2013 in Low Demographic Density Terriories: The Case of Extremadura. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1173. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, A.; Cárdenas, G. The Rural Development Policy in Extremadura (SW Spain): Spatial Location Analysis of Leader Projects. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2018, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, A.; Cárdenas, G.; Costa, L.M. Principal Component Analysis of the LEADER Approach (2007–2013) in South Western Europe (Extremadura and Alentejo). Sustainability 2019, 11, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.; Fernandez, J.L. Iniciativas de desenvolvimiento local no espaço rural portugués. In Território, Inovaçao e Trajectorias de Desenvolvimiento; Caetano, L., Ed.; Centro de Estudios Geográficos da Fluc: Coimbra, Portugal, 2001; pp. 241–272. [Google Scholar]

- Candela, A.R.; García, M.M.; Such, M.P. La potenciación del turismo rural a través del programa Leader: La Montaña de Alicante. Investig. Geogr. 1995, 14, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.; Moltó, E.; Rico, A. Actividades turístico-residenciales en las montañas valencianas. Eria 2008, 75, 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- García, M.; De la Calle, M. Turismo en el medio rural: Conformación y evaluación de un sector productivo en plena transformación. El caso del Valle del Tiétar (Ávila). Cuad. Tur. 2006, 17, 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pillet, F. Del turismo rural a la plurifuncionalidad en los territorios Leader y Proder de Castilla-La Mancha. In Turismo Rural y Desarrollo Local; Cebrián, F., Ed.; Universidad de Castilla La Mancha: Cuenca, España, 2008; pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- García, R. Turismo y desarrollo rural en la comarca del Noroeste de la región de Murcia: Los programas europeos Leader. Cuad. Tur. 2011, 27, 419–435. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez, D.; Foronda, C.; Galindo, L.; García, A. Eficacia y eficiencia de Leader II en Andalucía. Aproximación a un índice-resultado en materia de turismo rural. Geographicalia 2005, 47, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, A.; Cárdenas, G. 25 años de políticas europeas en Extremadura: Turismo rural y método Leader. Cuad. Tur. 2017, 39, 389–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Álvarez-Coque, J.M. La reforma de la PAC y el futuro de las ayudas agrarias. Rev. Valencia. Econ. Hacienda 2004, 11, 163–183. [Google Scholar]

- Compés, R. De la deconstrucción a la refundación: Elementos para un cambio de modelo de la reforma de la PAC 2013. In Chequeo Médico de la PAC; García Álvarez-Coque, J.M., Gómez Limón, J.A., Eds.; MARM and EUMEDIA: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 129–154. [Google Scholar]

- Massot, A. La PAC, entre la Agenda 2000 y la Ronda del Milenio: ¿A la búsqueda de una política en defensa de la multifuncionalidad agraria? Rev. Estud. Agro—Soc. Pequeros 2000, 188, 9–66. [Google Scholar]

- Colino, J.; Martínez Paz, J.M. El desarrollo rural: Segundo pilar de la PAC. In Política Agraria Común: Balance y Perspectivas; García Delgado, J.L., García Grande, M.J., Eds.; Colección Estudios Económicos La Caixa: Barcelona, Spain, 2005; pp. 70–99. [Google Scholar]

- García Grande, M.J. El último decenio: Aplicación y consecuencias de las reformas de la PAC. In Política Agraria Común: Balance y Perspectivas; García Delgado, J.L., García Grande, M.J., Eds.; Colección de Estudios La Caixa: Barcelona, Spain, 2005; pp. 44–69. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, J.S.; Ramos, E. El nuevo desarrollo rural y el futuro de la política rural en la Unión Europea. In Chequeo Médico de la PAC; García Álvarez-Coque, J.M., Gómez Limón, J.A., Eds.; MARM and EUMEDIA: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 177–212. [Google Scholar]

- Etxezarreta, M.; Cruz, J.; García, M.; Viladomiu, L. La Agricultura Familiar ante las Nuevas Políticas Agrarias Comunitarias; MAPA: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M.T.; Ramos, E.; Gallardo, R.; Ramos, F. De las nuevas tendencias en la evaluación a su aplicación en las iniciativas europeas de desarrollo rural. In El Desarrollo Rural en la Agenda 2000; Ramos, E., Ed.; MAPA: Madrid, España, 1999; pp. 323–344. [Google Scholar]

- Viladomiu, L.; Rosell, J. Evaluando políticas, programas y actuaciones de desarrollo rural. Rev. Econ. Agrar. 1998, 182, 297–308. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, M.; Mondéjar, J.A. Análisis de la inversión de los Fondos Europeos para el Desarrollo rural en Castilla-La Mancha. Rev. Econ. Castilla Mancha 2006, 9, 189–238. [Google Scholar]

- González, J. Desarrollo Rural de Base Territorial: Extremadura; MAPA and Consejería Desarrollo Rural: Badajoz, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- González, J. El método Leader: Un instrumento territorial para un desarrollo rural sostenible en Extremadura. In Desarrollo Rural de Base Territorial: Extremadura; González, J., Ed.; MAPA and Consejería Desarrollo Rural: Badajoz, Spain, 2006; pp. 13–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Preciado, J.F.; Parejo-Moruno, F.M.; Cruz-Hidalgo, E.; Castellano-Álvarez, F.J. Rural Districts and Business Agglomerations in Low-Density Business Environments. The Case of Extremadura (Spain). Land 2021, 10, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondéjar, J.A.; Mondéjar, J.; Vargas, M. Análisis del turismo cultural en Castilla-La Mancha (España). El impacto de los programas europeos de desarrollo rural LEADER y PRODER. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2008, 17, 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, M.; López, E. La contribución del turismo a la diversificación de actividades en un espacio rural periférico. Análisis del impacto de la iniciativa LEADER en Galicia. Rev. Estud. Agrosoc. Pesq. 2005, 206, 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Toledano, N.; Gessa, A. El turismo rural en la provincia de Huelva. Un análisis de las nuevas iniciativas creadas al amparo de los programas Leader II y Proder. Rev. Desarro. Rural. Coop. Agrar. 2002, 6, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, F.J. The Restoration of Religious Heritage as a Rural Development Strategy. In Handbook of Research on Socio-Economic Impacts of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage; Álvarez-García, J., Del Río-Rama, Mª.C., Gómez-Ullate, M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, F.J.; Del Río Rama, M.; Álvarez-García, J.; Durán-Sánchez, A. Limitations of Rural Tourism as an Economic Diversification and Regional Development Instrument. The Case Study of the Region of La Vera. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Álvarez, F.J.; Del Rio, M.D.L.C.; Durán-Sánchez, A.; Álvarez-García, J. Strategies for Rural Tourism and the Recovery of Cultural Heritage: Case Study of La Vera, Spain. In Capacity Building through Heritage Tourism. An International Perspective; Srivastava, S., Ed.; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Iakovidou, O.; Koutsouris, A.; Partalidou, M. The development of rural tourism in Greece, through the initiative Leader II: The case of northern and central Chalkidiki. Mediterr. J. Econ. Agric. Environ. 2002, 4, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolopoulos, N.; Liargovas, P.; Stavroyiannis, S.; Makris, I.; Apostolopoulos, S.; Petropoulos, D.; Anastasopoulou, E. Sustaining Rural Areas, Rural Tourism Enterprises and EU Development Policies: A Multi-Layer Conceptualisation of the Obstacles in Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, H. Searching for complementarities between agriculture and tourism: The demarcated Wine-producing regions of northern Portugal. Tour. Econ. 2006, 12, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, S.; Incerti, F.; Ravagli, M. Wine and tourism: New perspectives for vineyard areas in Emilia-Romagna. Cah. D’economie Sociol. Rural. 2002, 62, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakner, Z.; Besan, A.; Merlet, I.; Oláh, J.; Máté, D.; Grabara, J.; Popp, J. Building Coalitions for Diversified and Sustainable Tourism: Two case studies from Hungary. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghiri, M.; Okech, R. The Role of the Agritourism Management in Developing the Economy of Rural Regions. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2011, 1, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccio, V.; Mastronardi, L.; Marino, D.; Giannelli, A.; Scardera, A. Do Rural Policies Impact on Tourism Development in Italy? A Case Study of Agritourism. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolac, R.; Adamov, T.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Lile, R.; Rujescu, C.; Marin, D. Agritourism: A Sustainable Development Factor for Improving the “Healt” of Rural Settlements. Case Study Apuseni Mountains. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brankov, J.; Jojić, T.; Milanović, A.; Petrović, M.; Tretiakova, T. Resident’s Perceptions of Tourism Impact on Community in National Parks in Serbia. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kim, H.; Son, J. Measuring the Economic Impact of Rural Tourism Membership on Local Economy: A Korean Case Study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, E. The role of rural tourism on the development of rural areas: The case of Cyprus. Rom. J. Reg. Sci. 2014, 81, 38–53. [Google Scholar]

- Garau, C. Perspectives on Cultural and Sustainable Rural Tourism in a Smart Region: The Case Study of Marmilla in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability 2015, 7, 6412–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Roget, F.; Moutela, J.A.; Rodríguez, X.A. Length of Stay and Sustainability: Evidence from the Schist Villages Network (SVN) in Portugal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación para el Desarrollo Integral de la Comarca de la Vera (ADICOVER). Candidatura Presentada para Optar a la Concesión de Proder I; Tomo, I., Ed.; ADICOVER: Cuacos de Yuste, Spain, 1996; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Diputación de Cáceres. Estudio de Mejora del Posicionamiento Turístico Tajo-Salor-Almonte; Diputación de Cáceres: Cáceres, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, F.; Cejudo, E.; Cañete, J.A. Balance de la Iniciativa Comunitaria de desarrollo rural tras 25 años. Continuidad de las empresas creadas con apoyo de Leader I y II. El caso de las Alpujarras. In Treinta años de Política Agraria Común en España. Agricultura y Multifuncionalidad en el Contexto de la Nueva Ruralidad; Ruiz, A., Serrano, M., Plaza, J., Eds.; Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles: Ciudad Real, Spain, 2016; pp. 385–398. [Google Scholar]

- Cañete, J.A.; Cejudo, E.; Navarro, F. Proyectos fallidos de desarrollo rural en Andalucía. Boletín Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2018, 78, 270–301. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, F.; Cejudo, E.; Maroto, J.C. Aportaciones a la evaluación de los programas de desarrollo rural. Boletín Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2012, 58, 349–379. [Google Scholar]

- Centro de Estudios Socioeconómicos de Extremadura. Diagnóstico Ambiental y Estratégico de la Mancomunidad de La Vera; Consejería de Desarrollo Rural; Junta de Extremadura: Mérida, España, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación para el Desarrollo Integral del Tajo-Salor-Almonte (TAGUS). Estrategia de Desarrollo Local Participativo Comarca Tajo-Salor-Almonte (2014–2020); TAGUS: Casar de Cáceres, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Red Extremeña de Desarrollo Rural. El Territorio Rural Extremeño: Comarca del Tajo-Salor-Almonte; Red Extremeña de Desarrollo Rural: Cáceres, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Asociación para el Desarrollo Integral del Tajo-Salor-Almonte (TAGUS); Diputación de Cáceres. Estudio Territorial de Tajo-Salor-Almonte; TAGUS: Casar de Cáceres, Spain, 2018; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dirección General de Desarrollo Rural. Junta de Extremadura. In Documento de evaluación inicial Plan de Zona 04: Tajo-Salor y Sierra de San Pedro; Dirección General de Desarrollo Rural: Teléfono, Spain, 2012; pp. 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication Setting out Guidelines for Global Grants to Integrated Operational Programs, for Which States Are Requested to Submit Applications for Assistance within a Community Initiative for Rural Development (94/C 180/12); Official Journal of the European Communities; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- European Council. Regulation 1698/2005 of 20 September 2005 on Support for Rural Development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD); Official Journal of the European Communities, L/277; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation 1974/2006 of 15 December 2006 Laying down Detailed Rules for the Application of Council Regulation 1698/2005 on Support for Rural Development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD); Official Journal of the European Communities, L/368; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication to the Member States, Laying Down Guidelines for the Community Initiative for Rural Development (Leader +) (2000/C 139/05); C 139/05, Official Journal of the European Communities; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Durán, M. El estudio de caso en investigación cualitativa. Rev. Adm. 2012, 3, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, V.; Comet, C. Los estudios de casos como enfoque metodológico. ACADEMO Rev. Investig. Cienc. Soc. Humanid. 2016, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coller, X. Estudio de Casos. Cuadernos Metodológicos, 30th ed.; Centro Investigaciones Sociológicas: Madrid, España, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Solís, A.; Robina-Ramírez, R. Tourism Planning in Underdeveloped Regions. What Has Been Going Wrong? The Case of Extremadura (Spain). Land 2022, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M. Tourism Planning and Tourismphobia: An Analysis of the Strategic Tourism Plan of Barcelona 2010–2015. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2018, 4, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmo Moriche, Á.; Nieto Masot, A.; Mora Aliseda, J. Economic Sustainability of Touristic Offer Funded by Public Initiatives in Spanish Rural Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayat, K.; Sharif, N.M.; Karnchanan, P. Individual and collective impacts and residents’ perceptions of tourism. Tourism. Geogr. 2013, 15, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.D.; Snepenger, D.J.; Akis, S. Residents perceptions of tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Cheer, J. Overtourism and Tourismphobia: A Journey Through Four Decades of Tourism Development, Planning and Local Concerns. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 353–357. [Google Scholar]

| Programming Periods | Programmes Implemented | |

|---|---|---|

| La Vera | Tajo-Salor | |

| 1996–1999 | Proder I | Proder I |

| 2000–2006 | Proder II | Leader + |

| 2007–2013 | Leader Approach | Leader Approach |

| Development Program | Private Projects | Project Samples | Investment Private Project Samples | % Sample of Private Projects to the Total Investment of The Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proder I | 16 | 13 | 1,734,496.52 | 80.39 |

| Proder II | 18 | 11 | 1,445,888.78 | 69.76 |

| Leader Approach | 33 | 18 | 2,966,147.97 | 79.44 |

| Total | 67 | 42 | 6,146,533.27 | 77.18 |

| Development Program | Private Projects | Project Samples | Investment Private Project Samples | % Sample of Private Projects to the Total Investment of the Measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proder I | 7 | 5 | 731,509.26 | 89.03 |

| Leader + | 15 | 12 | 2,018,857.20 | 84.35 |

| Leader Approach | 16 | 6 | 1,294,216.23 | 71.60 |

| Total | 38 | 23 | 4,044,582.69 | 80.53 |

| Proder I | % | Proder II | % | Leader Approach | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural tourism | 2,157,490.16 | 40 | 2,072,606.99 | 38 | 3,733,694.87 | 42 |

| SMEs, crafts and services | 943,459.43 | 17 | 722,488.60 | 14 | 1,350,660.99 | 15 |

| Agricultural valorisation and marketing | 483,272.34 | 9 | 886,140.89 | 16 | 571,066.91 | 7 |

| Productive measures | 3,584,221.93 | 66 | 3,681,236.48 | 68 | 5,655,422.77 | 64 |

| Recovery of rural heritage | 1,227,340.71 | 23 | 1,097,471.54 | 20 | 1,898,051.36 | 21 |

| Operating costs and assistance | 608,532.98 | 11 | 666,967.20 | 12 | 1,297,185.49 | 15 |

| Unproductive measures | 1,835,873.69 | 34 | 1,764,438.74 | 32 | 3,195,236.85 | 36 |

| Total investment | 5,420,095.62 | 5,445,675.22 | 8,850,659.62 |

| Proder I | % | Leader + | % | Leader Approach | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural tourism | 821,601.20 | 14 | 2,393,457.27 | 19 | 1,807,502.00 | 19 |

| SMEs, crafts and services | 2,275,493.48 | 39 | 4,279,825.42 | 34 | 4,379,545.28 | 46 |

| Agricultural valorisation and marketing | 1,316,348.47 | 22 | 3,482,283.66 | 27 | 156,524.32 | 2 |

| Productive measures | 4,413,443.15 | 75 | 10,155,566.35 | 80 | 6,343,571.60 | 67 |

| Recovery of rural heritage | 936,749.45 | 16 | 865,719.48 | 7 | 1,443,123.98 | 15 |

| Operating costs and assistance | 544,212.56 | 9 | 1,710,748.42 | 13 | 1,731,478.83 | 18 |

| Unproductive measures | 1,480,962.01 | 25 | 2,576,467.90 | 20 | 3,174,602.81 | 33 |

| Total investment | 5,894,405.16 | 12,732,034.25 | 9,518,174.41 |

| Total Investment | Tourism Investment | |

|---|---|---|

| La Vera region | 19,716,430.46 | 7,963,792.02 |

| Tajo-Salor region | 28,144,613.82 | 5,022,560.48 |

| LA VERA | Proder I | Proder II | Leader Approach | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operational projects | 10 | 8 | 12 | 30 |

| Investment in operational projects | 1,368,481.94 | 1,108,030.26 | 2,332,379.97 | 4,808,892.17 |

| % of total investment in the sample | 79% | 77% | 79% | 78% |

| Failed projects | 3 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

| Investment failed projects | 366,014.58 | 337,858.52 | 633,768.00 | 1,337,641.10 |

| % of total investment in the sample | 21% | 23% | 21% | 22% |

| Projects carried over | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| Investment in projects carried over | 240,691.13 | 562,125.53 | 159,620.60 | 962,437.26 |

| % of total investment in the sample | 14% | 39% | 5% | 15% |

| TAJO SALOR | Proder I | Leader + | Leader Approach | Total |

| Operational projects | 4 | 8 | 6 | 18 |

| Investment in operational projects | 649,420.6 | 1,565,978.58 | 1,294,216.23 | 3,509,615,41 |

| % of total investment in the sample | 89% | 78% | 100% | 87% |

| Failed projects | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| Investment failed projects | 82,088.66 | 452,878.62 | 0 | 534,967.28 |

| % of total investment in the sample | 11% | 22% | 0% | 13% |

| Projects carried over | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Investment in projects carried over | 0 | 0 | 52,270.24 | 52,270.24 |

| % of total investment in the sample | 0% | 0% | 4% | 1% |

| TAJO-SALOR | Sex | Age | Origin | Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | Woman | <40 | Between 40 and 60 | >60 | Native | Returned | Neo-Rural | Basic | University | |

| Accommodation creation | 2 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 7 | 3 | ||

| Accommodation modernisation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Catering | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Other activities | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Total | 4 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 15 | 1 | 12 | 4 | ||

| LA VERA | ||||||||||

| Accommodation creation | 12 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 5 | |

| Accommodation modernisation | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| Catering | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| Other activities | ||||||||||

| Total | 19 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 17 | 3 | 3 | 18 | 5 | |

| TAJO-SALOR | Operational Projects | Interviews Conducted | Feasibility Assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unprofitable | Profitable | |||

| Rural accommodation (New creation) | 9 | 9 | 6 | 3 |

| Rural accommodation (Modernisation) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Creation of accommodation + catering | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Catering | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Complementary activities | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 17 | 17 | 7 | 10 |

| LA VERA | ||||

| Rural accommodation (New creation) | 11 | 10 | 9 | 1 |

| Rural accommodation (Modernisation) | 8 | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| Catering | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Complementary activities | ||||

| Total | 23 | 21 | 12 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castellano-Álvarez, F.J.; Robina Ramírez, R.; Nieto Masot, A. Tourism Development in the Framework of Endogenous Rural Development Programmes—Comparison of the Case Studies of the Regions of La Vera and Tajo-Salor (Extremadura, Spain). Agriculture 2023, 13, 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13030726

Castellano-Álvarez FJ, Robina Ramírez R, Nieto Masot A. Tourism Development in the Framework of Endogenous Rural Development Programmes—Comparison of the Case Studies of the Regions of La Vera and Tajo-Salor (Extremadura, Spain). Agriculture. 2023; 13(3):726. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13030726

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastellano-Álvarez, Francisco Javier, Rafael Robina Ramírez, and Ana Nieto Masot. 2023. "Tourism Development in the Framework of Endogenous Rural Development Programmes—Comparison of the Case Studies of the Regions of La Vera and Tajo-Salor (Extremadura, Spain)" Agriculture 13, no. 3: 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13030726

APA StyleCastellano-Álvarez, F. J., Robina Ramírez, R., & Nieto Masot, A. (2023). Tourism Development in the Framework of Endogenous Rural Development Programmes—Comparison of the Case Studies of the Regions of La Vera and Tajo-Salor (Extremadura, Spain). Agriculture, 13(3), 726. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13030726