Why “Say One Thing and Do Another” a Study on the Contradiction between Farmers’ Intention and Behavior of Garbage Classification

Abstract

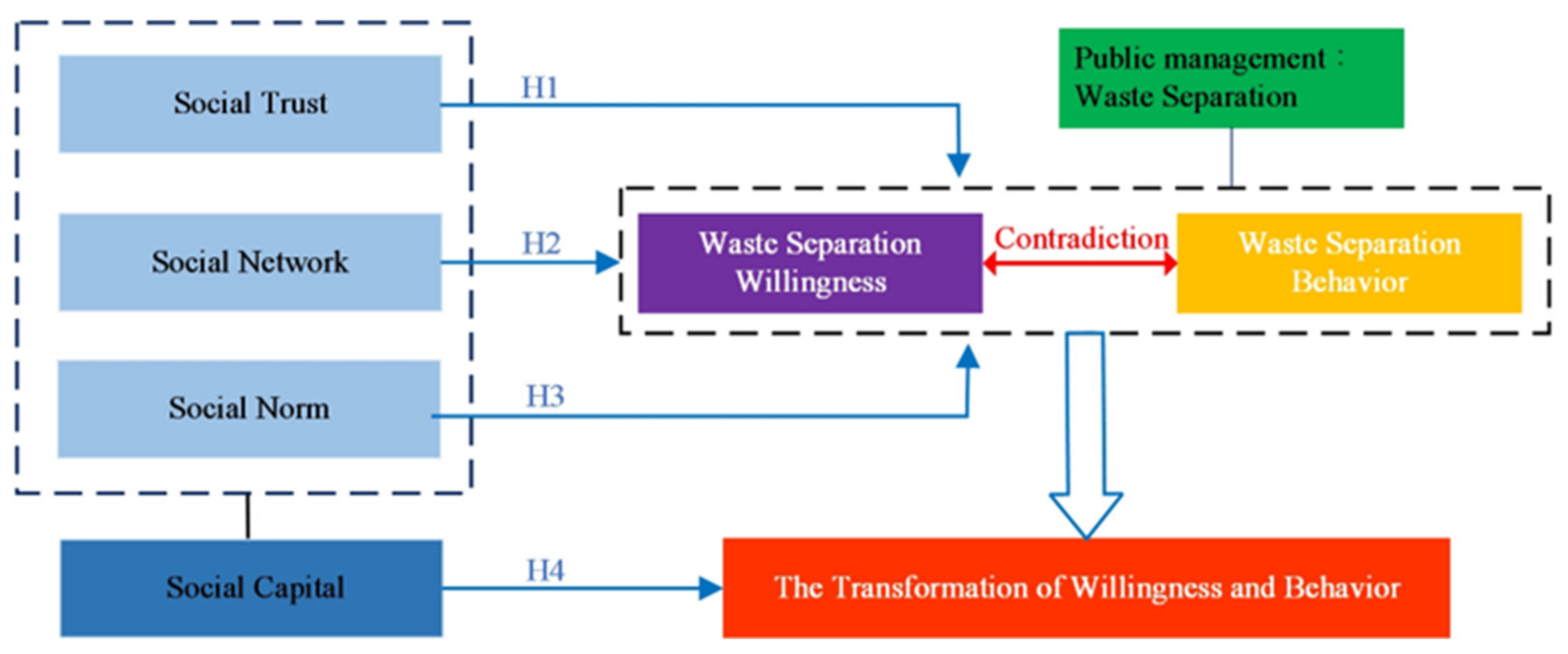

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Variable Description

3.3. Econometric Mode

3.3.1. Principal Component Analysis

3.3.2. Probit and Multinomial Logistic Regression Models

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Waste Separation Willingness and Behavior

4.2. Factor Analysis of Social Capital Affecting Rural Waste Separation

4.3. The Influence of Social Capital on Farmers’ Willingness and Behavior of Waste Separation

4.4. Robustness Tests on the Willingness and Behavior of Influencing Farmers to Separate Waste

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoornweg, D.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Kennedy, C. Peak waste: When is it likely to occur? J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Knickmeyer, D. Social factors influencing household waste separation: A literature review on good practices to improve the recycling performance of urban areas. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ma, G.; Wei, J.; Wei, W.; He, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Han, X. Evolutionary process of household waste separation behavior based on social networks. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Ye, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dan, Z.; Zou, Z.; Liu, D.; Shi, G. Characteristics and management modes of domestic waste in rural areas of developing countries: A case study of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 8485–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Xi, B.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Tang, Z.; Li, W.; Ma, C.; Wu, W. Solid waste management in China: Policy and driving factors in 2004–2019. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173, 105727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S. Information publicity and resident’s waste separation behavior: An empirical study based on the norm activation model. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.Z.; Yao, S.B.; Miao, S.S. The paradox between willingness and behavior: Factors influencing the households’ willingness to pay and real payment behavior on rural domestic garbage centralized treatment. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2016, 2, 1–6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Wen, Z.-G.; Chen, Y.-X. College students’ municipal solid waste source separation behavior and its influential factors: A case study in Beijing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.J.; Zhao, M.J. Willingness and behavior of household rural household garbage classification and treatment. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 5, 44–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Farani, A.Y.; Mohammadi, Y.; Ghahremani, F. Modeling farmers’ responsible environmental attitude and behaviour: A case from Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R 2019, 26, 28146–28161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.W.; Gu, H.Y. Famers’ Perception of Environment, Behavior Decision and the Check of Consistency between them: A Empirical Analysis Based on the Survey of Famers in Jiangsu Province. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2012, 10, 1204–1208. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, S. Rural public people: The social foundation of rural governance. Truth Seek. 2015, 6, 90–96. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Geng, Y.; Fujita, T. An overview of municipal solid waste management in China. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; He, L.; Liu, X.; Cheng, M. Bayesian-based conflict conversion path discovery for waste management policy implementation in China. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2018, 29, 347–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Niu, D.; Li, H.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, Y. Public perceptions and economic values of source-separated collection of rural solid waste: A pilot study in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 107, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Song, T.Q.; Chen, H.J.; Ouyang, Z.F. The Analysis of Garbage Pollution in Rural China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2010, 115 (Suppl. S1), 405–408. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Ling, M.; Lu, Y.; Shen, M. External influences on forming residents’ waste separation behaviour: Evidence from households in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zeng, D.; Li, Q.; Cheng, C.; Shi, G.; Mou, Z. Public willingness to pay and participate in domestic waste management in rural areas of China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Su, Z.G.; Zhang, S.P.; Zhang, S.R.; Yue, M.; Yue, Q.Y.; Wang, R.Q. A sorting collection method of rural household waste based on four categories. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 195 (Suppl. S2), 168–173. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, X.; Qu, M. Investigating rural domestic waste sorting intentions based on an integrative framework of planned behavior theory and normative activation models: Evidence from Guanzhong basin, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.F.; Bluemling, B. Research on the influencing factors and effects of household waste disposal behavior: Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 4, 37–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Koondhar, M.A.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Kong, R. Perceived value influencing the household waste sorting behaviors in rural China. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.M. Research on the performance of rural household garbage management from the perspective of farmer’ participation. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 5, 37–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.N.; Wang, C.J.; Shen, Z.; Lv, X.H. Empirical Analysis on Differences between the Willingness and Behaviors of Farmers’ Participation in Garbage Classification: A Case Study of Zhejiang Province. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2018, 12, 1726–1730, +1755. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ao, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chang, Y. Identifying the driving factors of rural residents’ household waste classification behavior: Evidence from Sichuan, China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180, 106159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Andronie, M.; Uţă, C.; Hurloiu, I. Trust Management in Organic Agriculture: Sustainable Consumption Behavior, Environmentally Conscious Purchase Intention, and Healthy Food Choices. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbous, A.; Tarhini, A. Does sharing economy promote sustainable economic development and energy efficiency? Evidence from OECD countries. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Blasio, N.; Fallon, P. The Plastic Waste Challenge in a Post-COVID-19 World: A Circular Approach to Sustainability. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2022, 10, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, L. Transitioning to a Low-Carbon Economy: Green Financial Behavior, Climate Change Mitigation, and Environmental Energy Sustainability. Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 2021, 13, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.M. Analysis on Public Participation in Rural Ecological Environment Governance. Rural. Econ. 2015, 12, 94–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, R.; Peris, J. The Role of Farmers’ Umbrella Organizations in Building Transformative Capacity around Grassroots Innovations in Rural Agri-Food Systems in Guatemala. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyes, D.; Ferri, P.; Henderson, F.; Whittam, G. The stairway to Heaven? The effective use of social capital in new venture creation for a rural business. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 39, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leap, B.; Thompson, D. Social solidarity, collective identity, resilient communities: Two case studies from the rural US and Uruguay. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, T.Q.; Huang, Y.H. The Construction of Rural Social Capital Measurement Index System and Its Application: Based on the Survey of Rural Social Capital in Western Region. World Surv. Res. 2015, 1, 38–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A. The Two Meanings of Social Capital. In Sociological Forum; Kluwer Academic Publishers-Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 15, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, H.; Yasunobu, K. What is Social Capital? A Comprehensive Review of the Concept. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2009, 37, 480–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, F. Trust, networks and norms: The creation of social capital in agricultural economies in Ghana. World Dev. 2000, 28, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.H. Social Capital: Theoretical discussion and empirical studies. Sociol. Stud. 2003, 4, 23–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, M.; Knickel, K.; Díaz-Puente, J.M.; Afonso, A. The role of social capital in agricultural and rural development: Lessons learnt from case studies in seven countries. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 59, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Zhao, G. Social Network Analysis of Actors in Rural Development: A Case Study of Yanhe Village, Hubei Province, China. Growth Chang. 2017, 48, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.A.; James, H.; Pittock, J. Social learning through rural communities of practice: Empirical evidence from farming households in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2018, 16, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Ward, H. Social capital and the environment. World Dev. 2001, 29, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.S. Farmers’ Small-scale Irrigation Facilities Participative Behavior under Multidimensional Social Capital Perspective. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2014, 12, 46–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, E.; Lee, K.; Shields, K.F.; Cronk, R.; Behnke, N.; Klug, T.; Bartram, J. The role of social capital and sense of ownership in rural community-managed water systems: Qualitative evidence from Ghana, Kenya, and Zambia. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 56, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C. Waste sorting in context: Untangling the impacts of social capital and environmental norms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Gong, Y.; Feng, C. Social trust, pattern of difference, and subjective well-being. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 2158244019865765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cook, K.S.; Rice, E.R.; Gerbasi, A. The Emergence of Trust Networks under Uncertainty: The Case of Transitional Economies—Insights from Social Psychological Research. In Creating Social Trust in Post-Socialist Transition; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.P.; Dajian, Z.; Le, N.P. Factors influencing waste separation intention of residential households in a developing country: Evidence from Hanoi, Vietnam. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B.; Wang, S.G. Social Capital, Rural Public Goods Supply and Rural Governance: Based on a Survey of Farming Households in 17 Villages in 10 Provinces. Econ. Sci. 2013, 3, 61–71. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, J.B.; Wu, X.L. Interpersonal Trust, Institutional Trust and Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in Environmental Governance: The Case of Agricultural Waste Resourceization. Manag. World 2015, 5, 75–88. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.Q.; Liu, P.Y.; Wu, N.W. Can Public Private Partnership (PPP) in Rural Environmental Governance Become a New Governance Model in China? An Analysis Based on a Reality Testing on Six Cases. China Rural Econ. 2018, 12, 67–82. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.Y.; Zhang, B. Social Network, Private Finance and Family Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Analysis Based on Urban-Rural Differences in China. J. Financ. Res. 2014, 10, 148–163. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, H.; Payne, D. Characteristics of Chinese rural networks: Evidence from villages in central China. Chin. J. Sociol. 2017, 3, 74–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y. Social Capital and Cross-Village Environmental Impact: Based on Village Investigation Data in Gansu Province. J. Nat. Resour. 2013, 8, 1318–1327. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S. Exploring the role of social networks in affective organizational commitment: Network centrality, strength of ties, and structural holes. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2011, 41, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Dong, F.; Goodman, J. How to leverage the role of social capital in pro-environmental behavior: A case study of residents’ express waste recycling behavior in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Trost, M.R. Social Influence: Social Norms, Conformity, and Compliance. In the Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed.; Gilbert, D.T., Fiske, S.T., Lindzey, G., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Iuchi, K. Policy-Supported Social Capital in Post disaster Recovery: Some Positive Evidence. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 428–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Z. The impacts of social interaction-based factors on household waste-related behaviors. Waste Manag. 2020, 118, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y. Review of Social Capital Measurement. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 7, 127–133. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huhe, N.; Chen, J.; Tang, M. Social trust and grassroots governance in rural China. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 53, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, H.T.; Sui, D.C.; Wu, H.X.; Zhao, M.J. The Influence of Social Capital on Farmers’ Participation in Watershed Ecological Management Behavior: Evidence from Heihe Basin. China Rural Econ. 2018, 1, 34–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.Q.; Liu, P.Y.; Bao, C.K.; Su, S.P. A Study on the Rural Environmental Governance through the Lens of Social Capital: A Case of Livestock Farming Pollution in the Undeveloped Region. J. Public Manag. 2016, 13, 101–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Astane, A.D.; Hajilo, M. Factors affecting the rural domestic waste generation. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2017, 3, 417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Cheng, Z.; Reisner, A.; Liu, Y. Compliance with household solid waste management in rural villages in developing countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.M.; Liu, Z.B.; Huang, S.W.; Zheng, Y.F. Cognition and Behavioral Responses of Farmers to Centralized Disposal of Rural Domestic Refuse: With Governance Situation Set as Regulatory Variable. J. Ecol. Rural Environ. 2017, 2, 127–134. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Watanabe, T. Win-win outcomes in waste separation behavior in the rural area: A case study in Vietnam. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Li, H.; Xia, F.; Niu, D.; Zhao, Y. Source-separated collection of rural solid waste in China. Source Sep. Recycl. 2017, 63, 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, M.L.; Zhang, J.N.; Wu, W.G.; He, Z.P.; Zhu, Y. Analysis of rural residents’ awareness of waste separation and its influencing factors. Rural Econ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 7, 234–238. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Aibar-Guzmán, B.; García-Sánchez, I.; Aibar-Guzmán, C.; Hussain, N. Sustainable product innovation in agri-food industry: Do ownership structure and capital structure matter? J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzamora-Ruiz, J.; Fuentes-Fuentes, M.D.; Martinez-Fiestas, M. Together or separately? Direct and synergistic effects of Effectuation and Causation on innovation in technology-based SMEs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 1917–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andati, P.; Majiwa, E.; Ngigi, M.; Mbeche, R.; Ateka, J. Determinants of Adoption of Climate Smart Agricultural Technologies among Potato Farmers in Kenya: Does entrepreneurial orientation play a role? Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2022, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.H.; & Zhu, Y.C. The Influence of Relational Networks on Farmers ‘Participation in Village Collective Action: Based on Farmers’ Participation in the Investment of Small Irrigation System. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2017, 1, 108–118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, M.; Singh, S.K.; Gupta, A.; Aggarwal, K.; Gupta, B.B.; Colace, F. Analysis & prognosis of sustainable development goals using big data-based approach during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2022, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Observed Variables | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Farmers’ willingness and behavior to separate waste | Waste separation willingness | Are you willing to separate household waste? (0 = No; 1 = Yes) |

| Waste separation behavior | Do you separate your household waste? (0 = No; 1 = Yes) | |

| The transformation of willingness and behavior | Willingness and behavior transformation of waste separation (0 = willingness not transformed into behavior; 1 = willingness unconverted into behavior; 2 = willingness converted into behavior) | |

| Social trust | Relatives trust | Level of trust in relatives (1 = very distrustful; 2 = relatively distrustful; 3 = average; 4 = relatively trusting; 5 = very trusting) |

| Neighborhoods trust | Level of trust in neighborhoods (1 = very distrustful; 2 = relatively distrustful; 3 = average; 4 = relatively trusting; 5 = very trusting) | |

| Village cadres trust | Level of trust in village cadres (1 = very distrustful; 2 = relatively distrustful; 3 = average; 4 = relatively trusting; 5 = very trusting) | |

| Social network | Number of cell phone contacts | The number of cell phone contacts (Person) |

| Number of people who can borrow 50,000 Yuan in trouble | The number of people who can borrow 50,000 Yuan when you in case of difficulties (Person) | |

| Social norm | Rural waste separation publicity | Does the government publicize the separation of rural household waste? (0 = No; 1 = Yes) |

| Rural waste separation rewards and punishments | Does the government reward and penalize rural household waste separation? (1 = Yes; 0 = No) | |

| Individual characteristics | Gender | Gender of interviewee (0 = Female; 1 = Male) |

| Age | Age of interviewee (Year) | |

| Education | Years of education of interviewee (Year) | |

| Household characteristics | Population | Total family population living at home for 6 months or more of year-round (Person) |

| Income | The annual income of the family (CNY) | |

| Environmental awareness | Awareness level of rural waste separation | Do you know how to sort rural waste? (1 = have not heard of it; 2 = just heard of it, not really; 3 = know a little; 4 = know better; 5 = know very well) |

| Awareness level of perception of environmental improvement by rural waste separation | Do you agree that the separation of waste has a positive effect on the improvement of the rural environment? (1 = completely disagree; 2 = not quite agree; 3 = fairly agree; 4 = more agree; 5 = completely agree) |

| Variables | Waste Separation Willingness | Waste Separation Behavior | The Transformation of Willingness and Behavior | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High social trust | 1036 | 673 | 666 | 1479 |

| High social network | 1465 | 669 | 666 | 1669 |

| High social norm | 1647 | 830 | 826 | 1865 |

| Samples | 2360 | 1268 | 1261 | 2628 |

| Proportion | 90.25% | 48.49% | 48.22% | 100% |

| Items | Components | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Trust | Social Norm | Social Network | |

| Q1 | 0.879 | 0.028 | 0.019 |

| Q2 | 0.841 | 0.014 | −0.004 |

| Q3 | 0.790 | 0.105 | 0.047 |

| Q4 | 0.012 | 0.793 | 0.001 |

| Q5 | 0.092 | 0.762 | 0.067 |

| Q6 | 0.016 | −0.002 | 0.756 |

| Q7 | 0.024 | 0.065 | 0.728 |

| Eigenvalue | 2.168 | 1.234 | 1.047 |

| Explained variance (%) | 30.196 | 17.530 | 15.825 |

| Cumulative variance (%) | 30.196 | 47.726 | 63.551 |

| Variables | Waste Separation Willingness | Waste Separation Behavior | The Transformation of Willingness and Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness Unconverted Behavior | Willingness Converted Behavior | |||

| Social trust | 0.016 ** | 0.015 | −0.004 | 0.019 |

| (0.006) | (0.012) | (0.010) | (0.012) | |

| Social network | 0.039 *** | 0.105 *** | −0.063 *** | 0.106 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.009) | |

| Social norm | 0.075 *** | 0.013 * | 0.051 ** | 0.041 *** |

| (0.023) | (0.007) | (0.024) | (0.011) | |

| Gender | −0.006 | −0.038 | 0.026 | −0.035 |

| (0.014) | (0.033) | (0.028) | (0.033) | |

| Age | 0.000 | −0.002 * | 0.002 | −0.002 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Education | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | |

| Population | −0.002 | −0.009 | 0.005 | −0.008 |

| (0.004) | (0.008) | (0.006) | (0.008) | |

| Income | 0.005 | 0.016** | −0.013 * | 0.016 ** |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.006) | |

| Awareness level of rural waste separation | 0.031 *** | 0.104 *** | −0.078 *** | 0.106 *** |

| (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.012) | (0.009) | |

| Awareness level of perception of environmental improvement by rural waste separation | 0.044 *** | 0.012 | 0.036 *** | 0.006 |

| (0.006) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.014) | |

| Regional dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.2966 | 0.2282 | 0.2354 | 0.2354 |

| N | 2503 | 2503 | 2503 | 2503 |

| Variables | Waste Separation Willingness | Waste Separation Behavior | The Transformation of Willingness and Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willingness Unconverted Behavior | Willingness Converted Behavior | |||

| Social trust | 0.018 *** | 0.016 | −0.007 | 0.018 |

| (0.006) | (0.012) | (0.010) | (0.012) | |

| Social network | 0.041 *** | 0.107 *** | −0.051 *** | 0.107 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.009) | (0.015) | (0.009) | |

| Social norm | 0.080 *** | 0.013 ** | 0.008 * | 0.013 *** |

| (0.028) | (0.006) | (0.016) | (0.006) | |

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.2966 | 0.2282 | 0.2354 | 0.2354 |

| N | 2503 | 2503 | 2503 | 2503 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, S.; Qing, C.; Guo, S.; Deng, X.; Song, J.; Xu, D. Why “Say One Thing and Do Another” a Study on the Contradiction between Farmers’ Intention and Behavior of Garbage Classification. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12081159

Zhou S, Qing C, Guo S, Deng X, Song J, Xu D. Why “Say One Thing and Do Another” a Study on the Contradiction between Farmers’ Intention and Behavior of Garbage Classification. Agriculture. 2022; 12(8):1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12081159

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Shiyao, Chen Qing, Shili Guo, Xin Deng, Jiahao Song, and Dingde Xu. 2022. "Why “Say One Thing and Do Another” a Study on the Contradiction between Farmers’ Intention and Behavior of Garbage Classification" Agriculture 12, no. 8: 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12081159

APA StyleZhou, S., Qing, C., Guo, S., Deng, X., Song, J., & Xu, D. (2022). Why “Say One Thing and Do Another” a Study on the Contradiction between Farmers’ Intention and Behavior of Garbage Classification. Agriculture, 12(8), 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12081159