Abstract

Strategic communication is essential to corporations in all industries, including agriculture. In this paper, the idea of corporate web positioning is developed using the example of agricultural corporations (agroholdings) in Russia. This idea reflects companies’ self-understanding communicated online to its customers, partners, competitors, broad public, and state. In our study, webpages of 50 Russian agroholdings were examined to judge their web positioning. The principal approach was qualitative identification of the common themes, which was followed by the analysis of the frequency of these themes. The content analysis of the webpages allowed identification of five general themes of corporate web positioning, namely customer satisfaction, national leadership, the company itself, business focus, and innovative technologies, and three supplementary themes such as natural/ecological products, healthy products, and own products (full-cycle production). It was established that customer satisfaction and national leadership are the most common general themes (two-thirds of all considered corporations). Our other finding was that the supplementary themes were registered for a third of the analyzed corporations. All themes matched the urgent aspects of the modern agriculture. Further interpretations show that the Russian peculiarities of the corporate web positioning in agriculture can be explained within the national socio-economical context. It is recommended that top managers of agroholdings should realize the already existing diversity of web positioning and try to explore new themes for effective strategic communication.

1. Introduction

Expansion and intensification of global agriculture are important trends [1,2,3,4,5] because this industry is essential for providing food security [6,7,8]. Corporations play a large role in agriculture development due to their ability to internationally network, attract voluminous investments, and support sustainability [9,10,11,12,13]. In countries with large territories, the importance of agriculture-focused corporations is undisputable due to of geographical distances. For instance, the Russian agriculture is an impressive industry, with arable and pasture lands constituting 13% of the country’s total territory [14] and a 4% contribution to the country’s GDP [15]. Its current state, challenges, and perspectives were reviewed by Averkieva et al. [16], Kulikov and Minakov [17], Uzun et al. [18], and Wegren [19]. Particularly, Tleubayev et al. [20], Yakovlev [21], and Wengle [22] stressed the outstanding importance of corporations (agroholdings) in the Russian agriculture. According to Semenov [23], the cumulative annual revenue of the fifty biggest agroholdings exceeds 33 billion USD. Indeed, these corporations are active business players developing and implementing long-term strategies.

Corporate strategies are strongly related to communication [24,25,26,27,28]. Companies need to explain strategic thoughts to their customers, partners, competitors, and administrative authorities for maintaining appropriate competitiveness, high performance, and effective marketing. Additionally, every communication strategy is closely tied to its successful implementation. Notably, Podnar and Balmer [29] concluded that corporate marketing includes sustaining corporate identity. In fact, such strategic communication tools as mission statements [30,31] reveal such an identity. Strategy communication seems to be essential to all corporations, but the latter are often industry-specific [32,33], and thus, their peculiarities should influence this communication. A restricted number of the related works focused on agriculture. For instance, Gregory [34] analyzed the French experience of corporate communication improvement in this industry, whereas Civero et al. [35] examined how deficiencies in the existing communication strategies undermine consumer perception of corporate social responsibility. Both works indicated serious problems with strategy communication in agriculture. Nonetheless, this issue remains poorly explored and not illustrated adequately with examples from different national frames and socio-economical contexts. Generally, the previous research implies that if any agricultural corporation wishes to succeed, it should pay significant attention to corporate strategic communication and utilize its various channels. From the latter, official corporate webpages seem to be among the most important.

An objective of the present, essentially tentative and empirical paper is to shed light on corporate positioning of major agricultural corporations on their webpages, which seems to be an important tool for strategic communication. The proposed idea was tested using an example from Russia, chiefly because corporations play such an important role in Russian agriculture; they tend to dominate in many segments of the market. Our attention was paid to the largest enterprises (the above-mentioned agroholdings), which can be called true corporations. Importantly, this study does not deal with organization and design of webpages. It focuses on the types of information which are available on these webpages.

2. Review and Proposal

2.1. Literature Review: Broad Context

The present paper introduces a novel ideanthat should be put into the proper context, which is not restricted to agriculture. For this purpose, the available knowledge is reviewed below in the following order: strategic management and marketing in agriculture, strategic communication in general, and strategic communication tools and channels with emphasis on webpages. This knowledge is provided for general reference and to stress the relation of the new proposal to the already existing vast research field.

Agriculture faces various risks, both natural and anthropogenic. As a result, strategic management in this field should address such risks. Hoag [36] showed the effectiveness of organized frameworks for risk management for reaching these strategic goals. Alborov et al. [37] paid attention to the other aspect, namely strategic management accounting, which is designed as a system facilitating effective managerial decisions. Tingey-Holyoak and Pisaniello [38] addressed the institutional environment of strategic management in the Australian agriculture and offered a typology of responses to resources pressure. Among the most recent developments is the concept “Agriculture 5.0” [39], which relates strategic management in agriculture to sustainable development and approaches of energy-smart farming. It was found that attention to “green” energy sources creates new opportunities for strategic decision-making in this industry.

Strategic marketing plays an important role in the development of modern agriculture. McLeay et al. [40] indicated strategic groups as important drivers of marketing in agribusiness. Ritson [41] distinguished general marketing from agricultural marketing and noted their convergence, emphasizing that traditional approaches of marketing in this industry match the present-day demand. Heiman and Hildebrandt [42] connected marketing to risk management specific to agriculture. New, “high-tech” developments facilitating the growth of smart agriculture open new perspectives for marketing: as explained by Huang and Chen [43], big data analysis can contribute to more effective promotion of agribusiness and its products.

Strategic communication is a vast research field, and decades of investigations have shown that the related activities have dual nature. This communication permits the use of available, pre-developed strategies for achieving the company’s goals, and, particularly, it may be helpful in crisis situations [44]. Moreover, it permits implementing and testing strategies as well as justifying, updating, and even resetting them [45,46]. According to Stainer and Stainer [47], communication is related to corporate productivity and performance. A particular aspect emphasized in the literature is disclosure of corporate social and environment responsibility, which can be judged as a kind of strategic communication [48,49,50]. It is known that such a disclosure improves the related responsibility performance [51]. In some countries, corporations tend to communicate their strategies to solve additional, high-order tasks linked to national interests [52] or patriotism [53,54,55].

Strategy can be communicated very differently. Although an entire document thoroughly explaining a given corporate strategy (or a particular, but major aspect such as its sustainability strategy) can be available freely, such a document is often too specific, too technical, and too long. Moreover, not all strategic intentions should be disclosed to competitors or the broad public due to commercial interests. The same concerns are applicable to the other “lengthy” communications such as annual reports. As a result, tools of brief strategic communication such as mission, vision, core (shared) values, etc. gain importance. They reflect the most principal, essential strategic thinking of top managers and the corporate identity. Many researchers showed that the use of these tools and, particularly, mission statements has positive effects on performance [56,57,58,59]. Mas-Machuca and Marimon [60] demonstrated that the availability of a “good” mission and its effective communication as a factor of increase in performance are moderated by some other factors and conditions. Additionally, the experiments of Alshameri and Green [61] showed that missions and visions of individual companies reflect the identity of industries. Additionally, there are many other available tools, such as CEO statements [62]. Annual reports are also important communication tools [63], but these documents are often too lengthy and too technical (see above).

Channels of strategic communication differ. These range from published advertisements [64] and interviews with journalists [65] to various media, including social networks and Internet blogs [66,67,68,69,70]. Corporate webpages have remained among the main channels of strategic communication, being official, almost mandatory attributes of corporations which reflect their identity and summarize (archive) all principal (including strategic) documentation, which is specified by top managers for disclosure. A huge amount of literature has been devoted to corporate webpages, their properties, and their importance to performance [71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81]. Generally, these studies prove the necessity of corporate webpages, their utility as sources of basic information about companies, and their importance for strategic communication.

The previous research briefly outlined above provides three general ideas. First, strategic communication is vitally important to corporations. Second, the tools facilitating brief communication of strategy elements are effective. Third, corporate webpages constitute the most important channel of strategic communication. Taken together, these ideas suggest that placing mission and vision statements, values, and other brief outlines of strategic thoughts to webpages is important to corporations. This understanding was proven in the studies by Bartkus et al. [82], Harrison [83], Lee et al. [84], Ruban and Yashalova [81], Tenca [85], Wenstop and Myrmel [86], and Yadav and Sehgal [87], who also demonstrated the usefulness of online statements for the purposes of research in corporate communication and strategic management.

2.2. Proposal of a New Idea

In agriculture, the importance of corporate communication is dictated by several specific reasons (in addition to the general needs of marketing and self-identity development). First, agriculture faces various risks; therefore, the performance and image of agricultural corporations depends on the clarity of their risk-related strategies [88,89]. Second, agriculture development is strongly tied to environmental issues [90,91,92]; therefore, environmental disclosure is essential to this industry. Third, agricultural production determines food security [93,94,95]; therefore, this industry has outstanding social “sensibility”, which makes appropriate positioning very important to companies.

Not all corporations choose to outline missions, visions, and other similar elements on their webpages, whereas all corporations (with very few exceptions) have well-established webpages offering brief “welcome presentations” of their business. One can easily find short statements (chiefly textual, but sometimes graphical or mixed) which reveal corporate self-understanding (Figure 1). These elements show how companies wish to look in the eyes of their customers, partners, competitors, broad public, and state. This is a tool of strategic communication for two reasons. First, it represents the systemic corporate intention to have a definite image for achieving some strategic goals (strategy of communication). Second, the desired image is linked (at least partly) to strategic thoughts of this corporation’s top managers (strategy of organization).

Figure 1.

Corporate web positioning statements on idealized webpages.

Indeed, some of these “welcome presentations” may serve principally for advertising purposes, but it is difficult to believe that their authors invent them completely independently from managerial indications and preferences, or without links to the corporate identity (this argument is especially reasonable in the case of large corporations, where development of webpages is always a serious task). Moreover, one should consider that when a company’s identity is revealed this way, it works as strategic communication, irrespective of its correspondence to the true strategic thought or its absence (note that the absence of intentions may also be strategy [28]). In regard to these considerations, the “welcome presentation” can be regarded among important tools of brief strategic communication, and it is possible to term it as corporate web positioning (Figure 1).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Collecting Materials

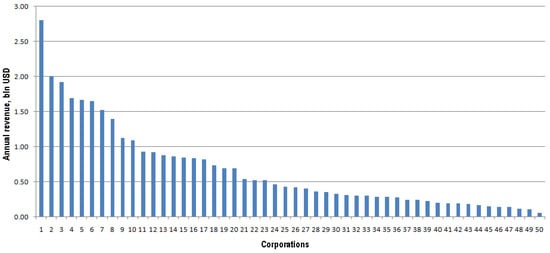

The present study addresses the fifty biggest agroholdings of Russia according to their annual revenue [23]. The latter exceeds 0.5 billion USD in about one half of the cases and 1.0 billion USD in one fifth of the cases (Figure 2). The activities of these agroholdings are diverse and include both “pure” agricultural activities and food production (such an integration of diverse activities is among the main reasons for their creation). Nonetheless, about one half of them demonstrate a certain specialization (poultry, livestock, vegetable oil production, dairy production, horticulture, etc.). Indeed, there are many small and medium enterprises which are not included in the employed ranking [23], but the considered agroholdings represent true, private agricultural corporations. Only corporations from this ranking are considered in the present study in order to maintain the homogeneity of the sample, which is essential to an analysis such as this one.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the considered Russian agricultural corporations depending on their annual revenue (based on information from [23]).

Official corporate webpages of all considered agroholdings were examined. Forty-seven of them were individual webpages, two corporations used only social networks, and the webpage of one organization was not found. Corporate web-positioning statements were found on all forty-nine analyzed corporate webpages. These statements constitute the material of the present study. The agroholdings’ names are not disclosed in this paper to avoid challenging their interests, and all analyzed statements are not given for the same reason (and because their translation in English would change their meanings). Nonetheless, some representative examples are provided together with the results.

3.2. Analytical Procedures

As in many other studies dealing with corporate communication tools [31,81,87,96,97,98,99], this study involves two approaches. The famous article about mission statements [31] is used as a kind of template, as it demonstrates how a new strategic communication tool can be introduced to the academic community. The automatic approaches of the content analysis [100,101,102,103,104] are not used in this study, as the analyzed statements were originally given in the Russian language and because they are too compressed and slogan-like to expect significant word overlap.

The first approach is qualitative interpretation of the collected 49 statements. The content of these statements is interpreted to establish their general meanings, and these meanings are compared subsequently to delineate common themes. These themes are proposed intuitively, and these are essentially groups of the similar-sounding statements. Nonetheless, the themes comprehend all meanings of the corporate web-positioning statements in the analyzed sample. Therefore, these can be called general themes. In addition, some supplementary themes can be distinguished. They seem to be notable but specific, and occurring in only part of the statements. It should be stressed that both the general and supplementary themes are not pre-established (for instance, on the basis of the literature review), rather these are established intuitively only to classify the available statements. This approach is rather simple and chiefly demonstrative, but is determined by interpretations of the statements and their categorization, i.e., delineation of the themes. Principally, the same method was carried out by Pearce and David [31] when they developed the idea of mission statements and their standard content components.

The second approach is quantitative analysis of the distribution (frequency) of the identified themes. Each statement is attributed to a particular theme, and the number and the breadth of the themes is justified to the meanings of the statements. The general and supplementary themes are considered separately. This permits us to understand the focus (or foci) of the corporate web positioning in the Russian agriculture. The number/percentage of each theme can be measured. It is important to undertake this analysis for the entire sample and for particular groups of corporations established depending on their size. Each group includes 10 corporations, starting from the largest and ending with the smallest, in the employed ranking [23].

4. Results

4.1. General Themes

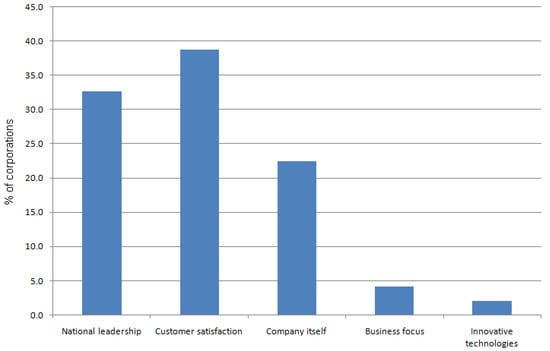

The biggest Russian agroholdings employ corporate web positioning in their online communication. The content of the related statements differed, although some coherence was evident. Five major themes could be distinguished, namely national leadership, customer satisfaction, the company itself, business focus, national leadership, and innovative technologies. The frequency of these themes also differed, but the majority (about two-thirds) of corporations tended to emphasize customer satisfaction and national leadership (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

General themes of the corporate web positioning of the considered Russian agricultural corporations.

Customer satisfaction was the most common theme [38.8% of statements]. The related corporate webpages often started with catalogues/advertisements of their products. For instance, one agroholding described its meat products and indicated that they are specially made for “meat amateurs”. The other agricultural corporation stated that “we care of people providing with tasty, quality and safe products”. In all these cases, the agricultural corporations positioned themselves as open to customers, i.e., connections to the latter are the main strategic priority to be perceived from their corporate webpages.

The second-most common theme was national leadership (32.7% of statements). The related corporate webpages displayed statements stressing that a given agroholding was the first (or among the biggest) companies of its kind and/or dominated the Russian market. For instance, one corporation stated that “it is one of the leaders of agricultural business of Russia”, and the other went so far as to proclaim itself as a “proven leader on the milk conservation market and ice-cream in Russia”; there was also a company describing itself with certain modesty as “the second leading Russian producer of beet sugar”. Such a web-positioning allows agroholdings to appear successful and dominant (a sign of “absolute success”), as rule-makers, and as nationally important organizations, and their leadership is their main strategic priority to be perceived from their corporate webpages.

The third-most important (although less common) theme was the company itself (22.4% of statements). The related corporate webpages displayed statements simply explaining what a given corporation is, how it is organized, and what it does. For instance, one agroholding stated that it has ten directions of activity, includes twenty five enterprises, boasts 330,000 ha of land resources, and employs 1200 persons; the other organization stated that it is “a Russian group of companies possessing assets in food industry, agriculture, package industry, and retail”. Such a web-positioning allows the related agroholdings to appear as well-developed, complex business units, often with serious material and human resources. Organizational “maturity” seems to be their main strategic priority to be perceived from their corporate webpages.

The fourth theme, namely business focus, was found in only two cases. The related webpages displayed statements outlining some basic principles of these agricultural corporations. One of them explained its business essence allegorically, as follows: “Big idea turns business into amazing adventure”, and the other stated that it helps to achieve success. Such a web-positioning helps agroholdings appear as businesses with philosophical foundations and very broad thoughts, which can be judged as their main strategic priorities to be perceived from their corporate webpages.

The fifth theme stands separately from the others, and it was found in a single case. The webpage of one agroholding started with indicating the modernity of equipment and implementation of innovations in its production process. This web-positioning specifies technological innovations as the main strategic priority to be perceived from the corporate webpage.

The distribution of the five identified general themes among groups of agroholdings with different annual revenues demonstrates certain differences (Table 1). First, the theme of customer satisfaction dominates only the largest and smallest of the considered corporations. Second, national leadership is most important to the relatively mid-sized agroholdings. Third, it appears that the choice of whether to position the company as market-concerned (national leadership) or customer-concerned (customer satisfaction), i.e., to send appeal to industry or customers, remains principal for all groups, and it is done with less certainty by the relatively mid-sized organizations. Fourth, attention to the company itself increases together with the decrease in the company size. Fifth, only the largest corporations allow themselves to demonstrate business focus in their web-positioning. Generally, it appears that the size of agroholdings matters as a factor of web positioning, although it is too early to try to explain it.

Table 1.

General themes in the groups of agroholdings with different size.

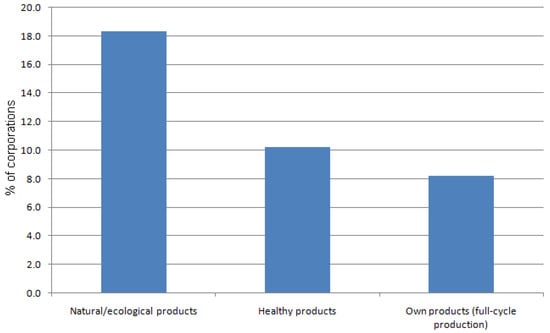

4.2. Supplementary Themes

In addition to the five general themes mentioned above, the qualitative content analysis of the web-positioning statements of the biggest Russian agricultural corporations reveals three supplementary themes that appear rather regularly. They reflect supplementary strategic priorities. These themes are related to natural products (ecological safety), healthy products (usefulness), and own products (full-cycle, “from field to shop” production). Taken together, these themes are reflected by the statements of more than 30% of the analyzed corporate webpages (in three cases, two themes coincide). The most important from them is the theme of natural products (18.4% of statements), and two others are less frequently addressed (Figure 4). For instance, the corporate webpage of one agroholding informs that its products are natural and grown “under the sun of Kuban” (this statement appeals to the common belief that the Russian South and, particularly, the Krasnodar Region, often labeled as Kuban, are the most favorable for agriculture and high-quality food production). In another case, one can read that “together with us [a given company] it is more tasty and useful [for health]”. These themes in the corporate web positioning allow the agroholdings to reflect their sustainability-related strategies linked to environment and health. However, the utilitarian, customer-focused aspects of such strategies are also evident in all cases.

Figure 4.

Supplementary themes of the corporate web positioning of the considered Russian agricultural corporations.

The distribution of the three identified supplementary themes among groups of agroholdings with different annual revenues shows three notable patterns (Table 2). First, it is evident that the ten largest corporations do not pay much attention to these themes. Second, there are some indications that the natural/ecological products are more important for web positioning of the relatively mid-size and small agroholdings, whereas the full-cycle production is less important to the smallest corporations. Third, there are corporations paying attention to at least one (commonly two) supplementary theme among all groups, which is a sign of the general interest to the related issues and the understanding of their importance to corporate web positioning. Nonetheless, it appears that the distribution of the supplementary themes is more haphazard than that of the principal themes.

Table 2.

Supplementary themes in the groups of agroholdings with different size.

5. Discussion

The outcomes of the present study raise three general questions, as follows. First, is corporate web positioning a distinctive tool of strategy communication? Second, do the distinguished themes matter to modern agricultural corporations? Third, how it is possible to explain the frequency of the themes in regard to the Russian agriculture? The related discussions are provided below.

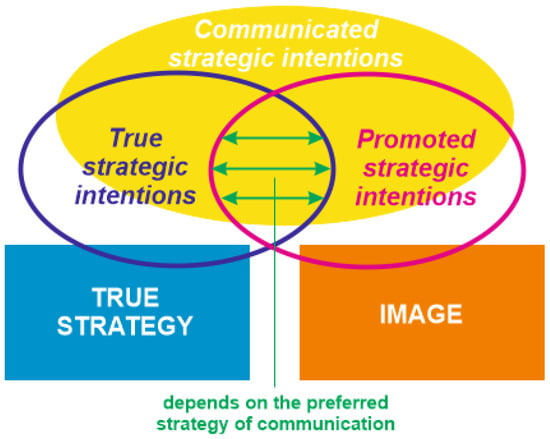

The corporate web-positioning statements reveal several most-principal intentions of top managers. These include focus on customers, market leadership, organizational “maturity”, following philosophical principles, technological advancement, and sustainability (see above). Indeed, these intentions are strategic because they indicate how a given agroholding understands itself and which approach it chooses to survive and to succeed. As the related statements are placed on the corporate webpages, corporations do not necessarily disclose their true strategic intentions, but reflect the image-related intentions to be perceived by customers, partners, competitors, the broad public, and the state. Such strategic intentions can be labeled provisionally as promoted intentions, and their overlap with true strategic intentions depends on the preferred strategy of communication (more shared or more hidden/false, Steensen [28]). Nonetheless, when corporate webpages are created professionally and responsibly, strategic thoughts of their top managers should be reflected there either directly or indirectly (it seems to be almost impossible to learn this post factum), and thus, the noted overlap is expected in the majority of the cases (Figure 5). Corporate web positioning differs from stating missions, visions, and values. The latter are more formal tools, which seem to be better attached to the true strategic thoughts of top managers. The content of web-positioning statements differs from that of other statements. Missions may be quite diverse in their content [31], whereas web positioning emphasizes a single priority related to the most important strategic approach. Vision is commonly focused on the future, whereas web positioning reflects the present state of the corporation. Values are the preferred ideals, whereas web positioning deals with the current state and the identity of organization. These comparisons imply that web positioning differs from the other tools of brief strategic communication.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the intentions communicated via web positioning.

The five themes of the corporate web positioning of the biggest Russian agroholdings (Figure 3) seem to be urgent. The customer satisfaction theme matches the customer-dominant logic recommended to the modern business [105]. Similar recommendations are meaningful in agriculture [106,107,108]. The national leadership theme can be brought in correspondence to the “naturally” monopolistic intentions of corporations [109], although it is also linked to corporations’ ability to undergo major transitions [110]. The related issues have been discussed only occasionally relatively to agriculture [111,112] because the market of this industry is often dominated by small and medium players. Nonetheless, in such a country as Russia, with its large territory and the related need in business consolidation, market leadership seems to be very expected. The theme of the company itself matters due to the outstanding importance of finding a corporation’s identity [113,114,115]. The theme of business focus seems to be important because understanding the very foundations (also philosophical) of a given company’s activities sheds light on its identity and performance [116,117,118,119,120], and this is also true for agribusiness [121,122,123,124,125]. The innovation theme is of outstanding urgency to the contemporary agriculture, which needs to provide food security, achieve sustainable practices, and adapt to environmental changes [126,127,128]. Finally, the three supplementary themes of the corporate web positioning found by the present investigation (Figure 4) correspond exactly to the imperatives of the current development of agriculture and, particularly, its “greening” and sustainability [129,130,131,132,133,134,135]. One should note the expected demand for environmental safety by the future agribusiness leaders [136].

The corporate web positioning of the biggest Russian agroholdings revealed by the present investigation has three main peculiarities, namely significant emphasis on national leadership (Figure 3), relatively small attention to innovative technologies (Figure 3), and focus on product “greening” (Figure 4). The first peculiarity can be explained by the necessity to present the corporation in the light of its success and outstanding competitiveness. However, emphasizing the national scale of a company’s activities can create additional meanings in the case of Russia. It should be noted that the factor of patriotism is significant to many aspects of Russian businesses and, particularly, corporate culture and communication [55]. The national-scale initiatives are important to agriculture development [22,137,138]. It is possible that the emphasis on the national leadership in the web positioning reflects some “deep” strategic thoughts specific to Russian managers. The second peculiarity is unusual at first glance due to the evident urgency of innovations in the Russian agriculture [139,140,141]. The low frequency of the related statements can reflect challenges of innovation implementation [141,142]; thus, “conservative” managerial thoughts can generate their own benefits. The third peculiarity can be explained by the strengthened pro-environmental attitudes and spread of pro-environmental behavior in Russia, which occurs both at the individual and corporate levels [143,144,145,146,147]. In such conditions, consumers’ demand for “green” products and the readiness of the business community to rework their production stimulate agricultural corporations to develop environment-focused strategies and to communicate them online. This finding also demonstrates that some doubts about pro-environmental focus in the contemporary Russian society [148,149] are nothing more than serious misinterpretations.

6. Conclusions

The undertaken examination of the corporate web positioning of the fifty Russian agroholdings with the biggest annual revenue allowed us to come to three general conclusions. First, web positioning is a tool of online communication of strategies which is used by corporations to state their self-understanding and to achieve a desirable image. Second, from five general themes of the web-positioning statements of the Russian agricultural corporations, the most important are customer satisfaction and national leadership; the supplementary themes pay attention to product “greening”. Third, the established themes match the needs of the contemporary agriculture, and some peculiarities of the statements by the Russian agroholdings can be explained within the national socio-economical frame.

The theoretical implication of the present investigation is linked to revealing the importance of corporate web positioning as a particular tool of brief strategic communication, which differs from such well-known tools as mission and value statements. Practically, the outcomes of this study indicate the general importance of strategic communication development in agriculture. More specifically, the latter must be justified to both the true strategic needs and the given national context (webpages of some Russian agroholdings offer many examples and templates for achieving this task). Two other practical implications can also be specified. First, corporate managers responsible for strategic communication should pay more attention to the content of official corporate webpages and the frontline statements (“welcome presentations”) there. Particularly, they need to realize the true diversity of their themes and to choose them more rationally than intuitionally. Second, the number of the general themes established in this study is limited. Therefore, corporate managers in agriculture can try to offer new themes, finding which themes may become significant competitive advantages to agroholdings. Generally, corporate policy in agriculture should aim at the effective use of web positioning and try to add it to the set of the other, well-known tools of strategic communication.

The main limitation of this study is a strong dependence on qualitative interpretations. Although these are reasonable and unavoidable for such a tentative and rather pioneering study, further methodological developments may allow identification and interpretations of the web-positioning statements on the basis of some quantitative procedures. Two other limitations include the sample size (there are numerous lesser agricultural firms, consideration of which would require collecting highly heterogeneous information, which is not suitable for a pioneering study such as this) and attention to only Russia (although the dominance of agroholdings is typical to this country, analogues to them may be found in some other places of the world). Indeed, these limitations indicate the possible directions of the following research. A broader perspective for further investigations is linked to examination of the corporate web positioning for different industries and national/cultural contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.R. and N.N.Y.; methodology, D.A.R.; investigation, D.A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.R. and N.N.Y.; writing—review and editing, D.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fuglie, K. R & D Capital, R & D spillovers, and productivity growth in world agriculture. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2018, 40, 421–444. [Google Scholar]

- Hazell, P.; Wood, S. Drivers of change in global agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, B.; Dietz, S.; Swanson, T. The Expansion of Modern Agriculture and Global Biodiversity Decline: An Integrated Assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 144, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Sutherland, W.J.; Ashby, J.; Auburn, J.; Baulcombe, D.; Bell, M.; Bentley, J.; Bickersteth, S.; Brown, K.; Burke, J.; et al. The top 100 questions of importance to the future of global agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2010, 8, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Donckt, M.; Chan, P.; Silvestrini, A. A new global database on agriculture investment and capital stock. Food Policy 2021, 100, 101961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Long, S.P.; Smith, P.; Banwart, S.A.; Beerling, D.J. Technologies to deliver food and climate security through agriculture. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meemken, E.-M.; Qaim, M. Organic Agriculture, Food Security, and the Environment. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2018, 10, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, C.F.; Kopainsky, B.; Stephens, E.C.; Parsons, D.; Jones, A.D.; Garrett, J.; Phillips, E.L. Conceptual frameworks linking agriculture and food security. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor, K.S. Global Value Chains and Agribusiness in Africa: Upgrading or Capturing Smallholder Production? Agrar. South 2019, 8, 30–63. [Google Scholar]

- Grabs, J.; Carodenuto, S.L. Traders as sustainability governance actors in global food supply chains: A research agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1314–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, E.H. Transnational Corporations and Third World Agriculture. Dev. Chang. 1975, 6, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondelli, M.P.; Klein, P.G. Private equity and asset characteristics: The case of agricultural production. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2014, 35, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerville, M.; Magnan, A. ‘Pinstripes on the prairies’: Examining the financialization of farming systems in the Canadian prairie provinces. J. Peasant. Stud. 2015, 42, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosstat. Regions of Russia. Socio-Economical Indicators. Available online: https://rosstat.gov.ru/folder/210/document/13204 (accessed on 24 July 2021).

- RBC. Agro-Industrial Complex of Russia: Results of 2020. Available online: https://marketing.rbc.ru/articles/12394/ (accessed on 24 July 2021).

- Averkieva, K.V.; Dan’shin, A.I.; Zemlyanskii, D.Y.; Lamanov, S.V. Strategic challenges of the development of agriculture in Russia. Reg. Res. Russ. 2017, 7, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikov, I.M.; Minakov, I.A. Modernization of the Material and Technical Resources in Agriculture of Russia. Univers. J. Agric. Res. 2022, 10, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, V.; Shagaida, N.; Lerman, Z. Russian agriculture: Growth and institutional challenges. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegren, S.K. Prospects for Sustainable Agriculture in Russia. Eur. Countrys. 2021, 13, 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Tleubayev, A.; Bobojonov, I.; Gagalyuk, T.; Meca, E.G.; Glauben, T. Corporate governance and firm performance within the Russian agri-food sector: Does ownership structure matter? Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 649–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, A.Y. State agricultural companies in Russia: Characteristic and legal status. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 548, 022101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wengle, S.A. Agroholdings, Technology, And the Political Economy of Russian Agriculture. Lab. Russ. Rev. Soc. Res. 2021, 13, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, S. The 50 Biggest Companies of the Agro-Industrial Complex of Russia. Available online: https://vestnikapk.ru/articles/otraslevye-reytingi/50-krupneyshikh-kompaniy-apk-rossii/ (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Chen, Z.F.; Tao, W. Hybrid Strategy—Interference or Integration? How Corporate Communication Impacts Consumers’ Memory and Company Evaluation. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2020, 14, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, S.L.; Weber, M.; Segovia, J. Using communication theory to analyze corporate reporting strategies. J. Bus. Commun. 2011, 48, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, M.B. Introduction to the special issue: Corporate communication—Transformation of strategy. J. Bus. Strategy 2019, 40, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Rader, S. What they can do versus how much they care: Assessing corporate communication strategies on Fortune 500 web sites. J. Commun. Manag. 2010, 14, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensen, E.F. Five types of organizational strategy. Scand. J. Manag. 2014, 30, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podnar, K.; Balmer, J.M.T. Quo Vadis Corporate Marketing? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, I.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J.; Guerrero, A.; Mas-Machuca, M. The real mission of the mission statement: A systematic review of the literature. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 456–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; David, F. Corporate Mission Statements: The Bottom Line. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1987, 1, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjuggren, P.-O.; Wiberg, D. Industry specific effects in investment performance and valuation of firms. Empirica 2008, 35, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannestea, B.S. How much do industry, corporation, and business matter, really? A meta-analysis. Strategy Sci. 2017, 2, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A. Issues management: The case of Rhône-Poulenc Agriculture. Corp. Commun. 1999, 444, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civero, G.; Rusciano, V.; Scarpato, D. Orientation of agri-food companies to CSR and consumer perception: A survey on two Italian companies. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 2018, 9, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoag, D.L.K. A strategic risk management program for agriculture. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2011, 3, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alborov, R.A.; Kontsevaya, S.M.; Klychova, G.S.; Kuznetsovd, V.P. The development of management and strategic management accounting in agriculture. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2017, 12, 4979–4984. [Google Scholar]

- Tingey-Holyoak, J.L.; Pisaniello, J.D. Strategic Responses to Resource Management Pressures in Agriculture: Institutional, Gender and Location Effects. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazou, K.; Garefalakis, A.; Zafeiriou, E.; Passas, I. Agriculture 5.0: A New Strategic Management Mode for a Cut Cost and an Energy Efficient Agriculture Sector. Energies 2022, 15, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeay, F.; Martin, S.; Zwart, T. Farm business marketing behavior and strategic groups in agriculture. Agribusiness 1996, 12, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritson, C. Marketing, agriculture and economics: Presidential address. J. Agric. Econ. 1997, 48, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman, A.; Hildebrandt, L. Marketing as a Risk Management Mechanism with Applications in Agriculture, Resources, and Food Management. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2018, 10, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, Y. Agricultural business and product marketing effected by using big data analysis in smart agriculture. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 2021, 71, 980–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardis, F.; Haigh, M.M. Prescribing versus describing: Testing image restoration strategies in a crisis situation. Corp. Commun. 2009, 14, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerfass, A.; Viertmann, C. Creating business value through corporate communication: A theory-based framework and its practical application. J. Commun. Manag. 2017, 21, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerfass, A.; Vercic, D.; Nothhaft, H.; Werder, K.P. Strategic Communication: Defining the Field and its Contribution to Research and Practice. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2018, 12, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainer, A.; Stainer, L. Productivity and performance dimensions of corporate communications strategy. Corp. Commun. 1997, 2, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerup Nielsen, A.; Thomsen, C. Reviewing corporate social responsibility communication: A legitimacy perspective. Corp. Commun. 2018, 23, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Ven, B. An ethical framework for the marketing of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.; Elkington, J. The end of the corporate environmental report? Or the advent of cybernetic sustainability reporting and communication. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2001, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbohn, K.; Walker, J.; Loo, H.Y.M. Corporate Social Responsibility: The Link Between Sustainability Disclosure and Sustainability Performance. Abacus 2014, 50, 422–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Z.; Pan, X. An analysis of national image communication strategies of Chinese corporations in the context of one-belt-one-road. Place Branding Public Dipl. 2020, 16, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Xiu, L.; Wu, S.; Zhang, S. In search of sustainable legitimacy of private firms in China. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2017, 11, 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, A.; Sanz-Marcos, P.; Gordillo-Rodríguez, M.-T. Branding, culture, and political ideology: Spanish patriotism as the identity myth of an iconic brand. J. Consum. Cult. 2022, 22, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashalova, N.N.; Ruban, D.A.; Latushko, N.A. Cultivating patriotism—A pioneering note on a Russian dimension of corporate ethics management. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrill, P.; Omran, M.; Pointon, J. Company mission statements and financial performance. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2005, 2, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Sánchez, J.D.; Rivera, L. Mission statements and financial performance in Latin-American firms. Bus. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- David, F.R.; David, F.R. It’s time to redraft your mission statement. J. Bus. Strategy 2003, 24, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanov Marjanova, T.; Sofijanova, E. Corporate mission statement and business performance: Through the prism of Macedonian companies. Balk. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2014, 3, 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Mas-Machuca, M.; Marimon, F. From sense-making to perceived organizational performance: Looking for the best way. J. Manag. Dev. 2019, 38, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshameri, F.; Green, N. Analyzing the strength between mission and vision statements and industry via machine learning. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2013, 36, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajandran, K.; Taib, F. Disclosing compliant and responsible corporations: CSR performance in Malaysian CEO statements. GEMA Online J. Lang. Stud. 2014, 14, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasher, A.; Ali, A.M.; Abdullah, F.S.; Yuit, C.M. Review of studies on corporate annual reports during 1990–2012. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. Engl. Lit. 2013, 2, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farache, F.; Perks, K.J. CSR advertisements: A legitimacy tool? Corp. Commun. 2010, 15, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, J.D.; Deephouse, D.L. Avoiding bad press: Interpersonal influence in relations between CEOs and journalists and the consequences for press reporting about firms and their leadership. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1061–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aula, P. Social media, reputation risk and ambient publicity management. Strategy Leadersh. 2010, 38, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colton, D.A.; Poploski, S.P. A Content Analysis of Corporate Blogs to Identify Communications Strategies, Objectives and Dimensions of Credibility. J. Promot. Manag. 2019, 25, 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, R.; Rauschnabel, P.A.; Hinsch, C. Elements of strategic social media marketing: A holistic framework. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, R.; Dong, C.; Zhang, Y. How controversial businesses communicate CSR on Facebook: Insights from the Canadian cannabis industry. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Moggi, S.; Caputo, F.; Rosato, P. Social media as stakeholder engagement tool: CSR communication failure in the oil and gas sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageeva, E.; Melewar, T.C.; Foroudi, P.; Dennis, C. Evaluating the factors of corporate website favorability: A case of UK and Russia. Qual. Mark. Res. 2019, 22, 687–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esrock, S.L.; Leichty, G.B. Social responsibility and corporate Web pages: Self-presentation or agenda-setting? Public Relat. Rev. 1998, 24, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esrock, S.L.; Leichty, G.B. Corporate World Wide Web pages: Serving the news media and other publics. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 1999, 76, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esrock, S.L.; Leichty, G.B. Organization of Corporate Web Pages: Publics and Functions. Public Relat. Rev. 2000, 26, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larose, J.A. Company information on the world wide web: Using corporate home pages to supplement traditional business resources. Ref. Libr. 1997, 27, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopis, J.; Gonzalez, R.; Gasco, J. The evolution of web pages for a strategic description of large firms. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2020, 33, 2038–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Llopis Taverner, J.; González Ramírez, M.R.; Gascó Gascó, J.L. Analysis of corporate web pages as strategic describer. Investig. Eur. Dir. Y Econ. Empresa 2009, 15, 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Salam, A.F.; Rao, H.R.; Pegels, C.C. Content of Corporate Web Pages as Advertising Media. Commun. ACM 1998, 41, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J. What are the functions of corporate home pages? J. World Bus. 1999, 34, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, R.D.; Lemanski, J.L. Revisiting strategic communication’s past to understand the present: Examining the direction and nature of communication on Fortune 500 and Philanthropy 400 web sites. Corp. Commun. 2011, 16, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, D.A.; Yashalova, N.N. Society and environment in value statements by hydrocarbon producers. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkus, B.; Glassman, M.; McAfee, B. Do large European, US and Japanese firms use their web sites to communicate their mission? Eur. Manag. J. 2002, 20, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, V. Legitimizing private legal systems through CSR communication: A Walmart case study. Corp. Commun. 2019, 24, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-Y.; Fairhurst, A.; Wesley, S. Corporate social responsibility: A review of the top 100 US retailers. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2009, 12, 140–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenca, E. Remediating corporate communication through the web: The case of about us sections in companies’ global websites. ESP Today 2018, 6, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenstop, F.; Myrmel, A. Structuring organizational value statements. Manag. Res. News 2006, 29, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Sehgal, V. India’s Super 50 companies and their mission statement: A multifold perspective. J. Strategy Manag. 2019, 12, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, V.R.; Freier, A.; Veiga, C.P. A review of concepts, strategies and techniques management of market risks in agriculture and cooperatives. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016, 10, 739–750. [Google Scholar]

- Van Asseldonk, M.; Tzouramani, I.; Ge, L.; Vrolijk, H. Adoption of risk management strategies in European agriculture. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2016, 118, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachev, H. Management strategies for conservation of natural resources in agriculture. J. Adv. Res. Law Econ. 2013, 4, 4–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, A.L.; Dhyani, R.; Ranjan, M.; Madhav, S.; Sillanpää, M. Climate-resilient strategies for sustainable management of water resources and agriculture. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 41576–41595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, R.; Rivers, R.Y. Environmental management strategies in agriculture. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 28, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebbers, R.; Adamchuk, V.I. Precision agriculture and food security. Science 2010, 327, 828–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, F.P.; Breeze, R.G. Agriculture and food security. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 894, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, K.; Kolodziejczak, M. The role of agriculture in ensuring food security in developing countries: Considerations in the context of the problem of sustainable food production. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billington, P.J. Analysis of mission and vision statements. Proc.-Annu. Meet. Decis. Sci. Inst. 1996, 1, 398. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, E.; Garrido, S.; Carvalho, H. Online sustainability information disclosure of mold companies. Corp. Commun. 2021, 26, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, Y. Comparative analysis of mission statements of Chinese and American fortune 500 companies: A study from the perspective of linguistics. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, G.-H. A Content Analysis of International Airline Alliances Mission Statements. Bus. Syst. Res. 2020, 11, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaefer, F.; Roper, J.; Sinha, P. A software-assisted qualitative content analysis of news articles: Example and reflections. Forum Qual. Soz. 2015, 16, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Mion, G.; Loza Adaui, C.R.; Bonfanti, A. Characterizing the mission statements of benefit corporations: Empirical evidence from Italy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2160–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedbalski, J.; Slezak, I. The Main Features of Nvivo Software and the Procedures of the Grounded Theory Methodology: How to Implement Studies Based on GT Using CAQDAS. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2019, 861, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, A.; Vintrò, C.; Rius, J.; Vilaplana, J. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility in mining industries. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schebesta, H. Content analysis software in legal research: A proof of concept using ATLAS.ti. Tilburg Law Rev. 2018, 23, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, K.; Strandvik, T. Reflections on customers’ primary role in markets. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.T. Box-scheme as alternative food network—the economic integration between consumers and producers. Agric. Food Econ. 2020, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovic, B. Application of customer relationship management (CRM) in agriculture. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 6, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeli, A.H.; Utami, H.N.; Rahmanissa, R. Does customer satisfaction on product quality illustrates loyalty of agricultural product? Int. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. Res. 2016, 14, 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Teachout, Z. The problem of monopolies & corporate public corruption. Daedalus 2018, 147, 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, M.A.; Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Understanding the Role of the Corporation in Sustainability Transitions. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Hyun, J.-K. Development of performance indices for agro-food distribution corporations based on the AHP method. J. Distrib. Sci. 2017, 15, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, B.; Williams, O.; Nagarajan, V.; Sacks, G. Market strategies used by processed food manufacturers to increase and consolidate their power: A systematic review and document analysis. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M.T.; Greyser, S.A. Managing the multiple identities of the corporation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 44, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopaneva, I.M. Discursive Strategies of Organizational Identity Formation in Benefit Corporations: Coping with a Meanings Void and Assimilating External Feedback. West. J. Commun. 2021, 85, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.; Malik, A. Identities in transition: The case of emerging market multinational corporations and its response to glocalisation. Soc. Identities 2018, 24, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T. The stakeholder corporation: A business philosophy for the information age. Long Range Plan. 1998, 31, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, W.G.; Lockhart, J.C. Understanding the erosion of US competitiveness: Managed education and labor in Japanese “corporate castle towns”. J. Manag. Hist. 2017, 23, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasag, E.C. Corporate social responsibility: Business philosophy in global times. Philosophia 2016, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rendtorff, J.D. Risk management, banality of evil and moral blindness in organizations and corporations. Ethical Econ. 2014, 43, 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Examination on philosophy-based management of contemporary Japanese corporations: Philosophy, value orientation and performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amara, D.; Chen, H. Driving factors for eco-innovation orientation: Meeting sustainable growth in Tunisian agribusiness. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2022, 18, 713–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.C.; Kiran, R.; Goyal, D. Critical success factors of agri-business incubators and their impact on business. Custos Agronegocio 2019, 15, 352–378. [Google Scholar]

- Martos-Pedrero, A.; Cortés-García, F.J.; Jiménez-Castillo, D. The relationship between social responsibility and business performance: An analysis of the agri-food sector of southeast Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghaian, S.; Mohammadi, H.; Mohammadi, M. Factors Affecting Success of Entrepreneurship in Agribusinesses: Evidence from the City of Mashhad, Iran. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.C.; Arora, U. Agri-business: Present status and future prospects. Ann. Agri Bio Res. 2006, 11, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, M.; Wrzaszcz, W. On the way to eco-innovations in agriculture: Concepts, implementation and effects at national and local level. The case of Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.B.; Blok, V.; Poldner, K. Business models for maximising the diffusion of technological innovations for climate-smart agriculture. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes de Oca Munguia, O.; Pannell, D.J.; Llewellyn, R. Understanding the adoption of innovations in agriculture: A review of selected conceptual models. Agronomy 2021, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Agele, H.A.; Nackley, L.; Higgins, C.W. A pathway for sustainable agriculture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.; Van Dusen, D.; Lundy, J.; Gliessman, S. Integrating social, environmental, and economic issues in sustainable agriculture. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 1991, 6, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLonge, M.S.; Miles, A.; Carlisle, L. Investing in the transition to sustainable agriculture. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 55, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrigan, L.; Lawrence, R.S.; Walker, P. How sustainable agriculture can address the environmental and human health harms of industrial agriculture. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Canales, A.; García, M.F.-V. Sustainable applications in agriculture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, A.; Marta-Costa, A.; Fragoso, R. Principles of sustainable agriculture: Defining standardized reference points. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, R.M.; Graham, R.D. A new paradigm for world agriculture: Meeting human needs. Productive, sustainable, nutritious. Field Crops Res. 1999, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperini, F.A. Public Policy and the Next Generation of Farmers, Ranchers, Producers, and Agribusiness Leaders. J. Agromedicine 2017, 22, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demichev, V.V.; Maslakova, V.V. Influence of investments and subsidies on the efficiency of agriculture in Russia during the implementation of state programs. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 699, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodova, M.; Krinichnaya, E. Diversity of the agricultural sector of the Russian economy: Regularities of formation and development. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 210, 13009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agibalov, A.V.; Zaporozhtseva, L.A.; Tkacheva, Y.V. Agriculture of the Voronezh Region: Challenges and Prospects of the Digital Economy. Stud. Syst. Decis. Control. 2020, 282, 235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplitskaya, A.; Heijman, W.; Van Ophem, J.; Kusakina, O. Innovation policy and sustainable regional development in agriculture: A case study of the Stavropol Territory, Russia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharitonov, E.; Krikun, K.; Nesmyslenov, A. The role of innovations in the development of agriculture in Russia. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 262, 01016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laptev, S.V.; Filina, F.V.; Degteva, L.V. The Organization of Agricultural Markets as a Factor of Innovative Development in the Agricultural Economy. Stud. Syst. Decis. Control 2020, 282, 347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J.; Gold, N. Employee proenvironmental behavior in Russia: The roles of top management commitment, managerial leadership, and employee motives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molchanova, T.K.; Yashalova, N.N.; Ruban, D.A. Environmental concerns of Russian businesses: Top company missions and climate change agenda. Climate 2020, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzewski, P. Changes in environmental attitudes in selected countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Probl. Ekorozw. 2016, 11, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Soyez, K. How national cultural values affect pro-environmental consumer behavior. Int. Mark. Rev. 2012, 29, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, D. Environmental attitudes and contextual stimuli in emerging environmental culture: An empirical study from Russia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 2075–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashe, T.; Poberezhskaya, M. Russian climate scepticism: An understudied case. Clim. Chang. 2022, 172, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Martus, E. Contested environmentalism: The politics of waste in China and Russia. Environ. Politics 2021, 30, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).